Fact file:

Matriculated: 1904

Born: 15 October 1883

Died: 18 May 1918

Regiment: Grenadier Guards

Grave/Memorial: Warlincourt Halte British Cemetery: XII.B.7

Family background

b. 15 October 1883 at Columbia, Missouri, USA, as the fourth son (sixth child) of Colonel Alexander Frederick (“Fred”) Fleet (1843–1911) and Mrs Belle Seddon Fleet (née Matheson) (1851–1940) (m. 1883).

Parents and antecedents

Although proud of their American identity, the Fleets claimed descent from Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503–44), the Tudor poet, and, further back still, Bishop William Waynflete (c.1398–1486), the founder of Magdalen College in 1458. By the late eighteenth century, the Fleet family were a prominent Virginian family and Captain William (“Billy”) Fleet (1757–1833), Fleet’s great-grandfather, was a member of the Virginia Constitutional Council of 1788, a leading citizen, and a member of the Baptist Church. In c.1795 he married a young widow, Mrs Sarah Browne Tomlin (1776–1818), and they had 11 children, of whom the youngest, Dr Benjamin Fleet (1818–65), was Fleet’s grandfather. After studying Medicine, Dr Fleet returned to Virginia, where, before the Civil War (1861–65), he served as medical doctor to a large part of King and Queen County. He bought a fine house – Pickle Hill – just east of the Mattaponi River, changed its name to Green Mount, and used his resultant prosperity to develop the family’s wealth. For example, he expanded his land holdings at Green Mount to an estate of 3,000 acres that was worked by 50 slaves, making him one of the upper 10% of Virginian planters, and set up a toll bridge and two ferry services across the Mattaponi River where he built granaries to store his and his neighbours’ produce until it could be transported to the cities of the east coast. In 1842 Dr Fleet married Maria Louisa Wacker (1822–1900), whose father, Jacob David Wacker (1781–1829), had been a German-speaking page at the Court of the Emperor Leopold II in Vienna (1747–92; Emperor 1790–92) but who had emigrated to America in 1801 and used a bequest to train as a medical doctor. He had established a practice near the Fleet estates and married Maria Pollard (1796–1831) in 1817. They brought up Maria, their only surviving child, to be tough and self-reliant, and her resilience was tested by the death of both her parents before she was eight years old and her adoption by her uncle Colonel Alexander Fleet (1798–1877), Captain William Fleet’s oldest son and an equally respected member of Virginian society, whose wife was a sister of Maria Pollard. Maria Louisa Wacker went on to be educated in Richmond and in 1842 married Dr Benjamin Fleet, her adoptive father’s youngest brother.

Their union produced four sons and three daughters: Alexander Frederick (“Fred”), William Alexander’s father; Benjamin Robert (“Benny”; 1846–64); Maria Louise (“Lou”; 1847–1917); David Wacker (1851–1937); Florence (“Flossie”; 1852–1903); Betsy Pollard (“Bessie”; 1854–1904) and James William (“Willie”; 1856–1927).

David Wacker attended Virginia Military Academy and tried his hand at teaching, but he soon realized that it was not for him and moved to Montesanto County, in Washington Territory, which was enjoying a boom. Here he started out as a civil engineer working for the Northern Pacific Railroad, but branched out into real estate and later became a local Democratic politician, serving for many years as Montesanto County’s official auditor. He also became Washington’s City Engineer and the owner of a large amount of land. His son Reuben Hollis Fleet (1887–1975), one of the two children of his marriage in 1884 to Lillian Florence Adell Wade (1859–1938) (and Fleet’s cousin), enjoyed a very successful career at Culver College (q.v.). He then acquired teaching qualifications and taught for a few months before following his father and becoming a prosperous estate agent. Before World War One he served for a time in the National Guards but in 1917 he volunteered for the Army, was commissioned as Major, and assigned to the Signals and Aviation part of the US Army. In 1918 he set up the US Air Mail Service and after resigning from the services in 1922, he became an aircraft designer and manufacturer and in 1923 purchased the Dayton-Wright Company which he turned into the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, whose two most important aircraft were the Catalina (PBY-5) multi-role flying-boat (1935) and the Liberator (B-24) heavy bomber (1941), the USA’s most produced military aircraft. In the run-up to World War Two, he became a private consultant on aviation to Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945; US President 1933–45). In 1943 Fleet’s company merged with Vultee Aircraft to become Convair – which then went on to produce a range of famous military aircraft and the Atlas ICBM, which became the basis for Project Mercury (1959–63). In 1961 Reuben founded the San Diego Museum and in 1963 the American Institute of Aeronautical Sciences.

James William attended Richmond College, returned home to help run Green Mount, and served as a county judge and county attorney.

The girls of the family taught at Green Mount and other schools, or became governesses to private families.

Alexander Frederick, the oldest of the family and Fleet’s father, was given an extensive private education – at Fleetwood Academy, Rumford Academy, and Aberdeen Academy – before attending the University of Virginia. When the Civil War began, Fred was 19 years old and nearing the end of his first year at the University of Virginia, and although the Fleets owned slaves, they were not overly attached to that institution and, as Southern Whigs, favoured the preservation of the Union. Nevertheless, Fred supported his State in the Confederacy by enlisting in I Company (Jackson Grays) of the 26th Virginia Infantry. This was an unfortunate choice for an aspiring warrior since the Regiment was part of the Brigade commanded by Brigadier General Henry Wise (1806–71), a former Governor of Virginia who had signed the death warrant of the abolitionist John Brown (1800–59). Whilst acknowledged as brave, Wise was regarded as quarrelsome and incompetent by the senior Confederate commanders, Robert E. Lee (1807–70) in particular, and they solved the problem by ensuring that Wise’s Brigade was kept far from the field of battle. So, between 1861 and 1864, the 26th Virginia, derided by the rest of the Army as part of “Wise’s Ragged Brigade of Gardeners”, was perpetually in reserve or stationed in such far-flung corners of the Confederacy as Florida. During his time in the Army, Fleet became a Lieutenant and then a Captain and continually complained in his letters home about the mediocrity of his immediate superiors while being hard-headed enough to admit that the lack of action did improve his prospects of longevity. Eventually, in May 1864, the 26th Brigade was ordered into the trenches at Petersburg, Virginia, a vitally important railway junction 23 miles south of Richmond, the capital of Virginia and of the Confederacy, presumably because Lee was running short of troops. After three years of inactivity Captain Fleet was wounded twice within a few minutes in the fierce fighting that raged around the town. By the end of the Civil War, Fred had become Wise’s Adjutant with the rank of Colonel and was, after missing so many of the great events of the war, present at Appomattox Court House to witness Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant (1822–85) after the final battle of the Civil War had taken place there on 9 April 1865. But during Fred’s absence from the family home at Green Mount, the general decline of the South was replicated there in a series of economic and personal misfortunes: many of the slaves ran away, the house was looted by Union Army troops, and Fred’s younger brother Benjamin Robert was shot in the back on 2 March 1864 by raiding Union cavalry under the command of Colonel Ulrich Dahlgren (1842–64) and bled to death. All of which took its toll on Dr Fleet, who succumbed to an acute streptococcal infection in 1865 at the age of 47.

So when Fred returned from the war, the family’s main source of strength lay in his mother, Maria Louisa Wacker Fleet. During the Civil War Maria had to work hard to compensate for the decline in her husband as drink and depression vitiated his spirit, and as she had to be her family’s protector, she was wont to await any intruders with “three guns, a pistol and two clubs at hand”. And after the war was over, Maria Fleet needed all the energy she could muster since, while still grieving over the loss of her husband and son, she had to defend Green Mount against threats from all sides. Instead of Union marauders, she now had to deal with discharged Confederate soldiers, the machinations of avaricious neighbours who were hoping to benefit from the plight of a lone woman with a large family and only a few slaves to work her estate, and the scarcity of money and credit. Yet none of these problems deterred Maria from looking out for her children’s futures. She was determined that all of them, including the girls, should receive a college education and the next 20 years of her life were dominated by the need to raise money. She sold one of the ferries so that Fred could return to the University of Virginia, and in order to preserve Green Mount she deferred debts, paid for purchases by instalments, and fought court cases. In 1873 she even turned the house into a school for young ladies that was run by her second daughter, Florence. This experience was not an entirely happy one, for while Maria loved the pupils, she found that many of their parents were not anxious to pay the fees on time. Nevertheless, throughout all these trials she remained indefatigable and optimistic, and her philosophy was best summed up by her advice to the pupils: “Girls, if you do not learn but only one thing at Green Mount, I want you always to remember to put the best foot forward and look on the bright side – and if there is no bright side, then polish up the dark one.” So despite his antipathy to female students, Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902) would surely have admitted that Maria Wacker Fleet possessed many of the qualities that he was seeking in his Rhodes Scholars.

After Fred graduated from the University of Virginia in 1867, he realized that the resources of the estate could no longer support all the family. So in 1868 he went west to teach Classics at the University of Missouri, where he eventually became Professor of Greek and Latin. But despite his success as a university teacher, there is a sense of disillusion about him, a feeling that, in being forced to leave Virginia, he had been deprived of the entitlements due to a Southern gentleman, and in letters home he wrote of his disenchantment with life in the Mid-West and his desire to return to Virginia one day. In short, Fred was an archetypical Southern Romantic of the kind described by Wilbur Cash in The Mind of the South who could trace their ancestry to the English nobility and were devoted to the notion of chivalry. So although he originally named his third son Henry Wise Fleet in honour of his former Commanding Officer, he changed the child’s name to Henry Wyatt Fleet after about a year when General Wise’s son, John, became a Republican, a gesture that indicated both Fred’s sense of being an aristocrat and his desire to punish unchivalrous behaviour on the part of someone who was now consorting with the destroyers of his beloved Virginia. In 1871 Fred married Belle Seddon Matheson, another well-connected Virginian who was the niece of James A. Seddon (1815–80), the Confederate Secretary of War between 1861 and 1865. Fred Fleet’s background is important because it explains the cultural heritage which he passed on to his eight children and which William Alexander would bring with him to Magdalen over 20 years later.

Belle Seddon Matheson (1851–1940)

(From the Culver Academy Roll Call yearbook 1910)

Despite its size and the need to send money to his mother at Green Mount, Fred and his family led a comfortable enough life. A few months before William Alexander’s birth, he purchased a three-acre lot in Columbia, near the University, and had a house built there. He also made enough money from investments to be able to donate $1,000 to a new church and plan a trip to Europe. But when his underlying restlessness was exacerbated by his failure to be elected President of the University, he left higher education in 1890 and used his life savings and a loan to set up and become Superintendent of a Military Academy in Mexico, Missouri, a project that gave him the opportunity of passing on the traditions of the Old South despite the spoliations of the Civil War. The moral price of this was that, as head of a military institution, he was required to wear the only legally acceptable uniform – the dark blue of the United States Army. Well aware of the irony of the situation, he wrote to his mother: “Would you recognise your son in the same uniform Sheridan wore when he came to visit you in ’64?” The enterprise prospered until the night of 24 September 1896, when the main building burned down. But what looked like a catastrophe was retrieved when a telegram arrived from Henry Harrison Culver (1840–97) of Culver, Indiana, which proclaimed: “You have the boys and no building. I have the building and no boys. Let’s get together.” This situation had arisen because Culver had fallen out with the teaching staff of the Academy which he had founded in 1894 and they had resigned en masse, taking most of the pupils with them. So Fred transferred his staff and 85 boys to Indiana where, combining with the remaining 20 Culver boys, the group formed the new Culver Military Academy. As part of the financial agreement, the young male Fleets, including William Alexander, were to be educated there free of charge.

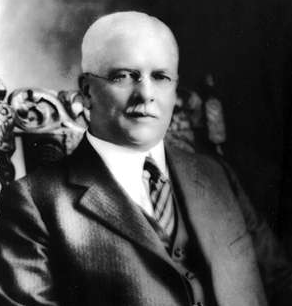

Alexander Frederick Fleet (1843–1911)

(From the Culver Academy Roll Call yearbook 1907)

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Mary Seddon (“Minnie”; 1873–1952); later Gignilliat after her marriage in 1898 to Leigh Robinson Gignilliat (later Brigadier-General) (1875–1952); two sons;

(2) Alexander Frederick Jr (1875–76);

(3) Belle Seddon (1876–1969); later Matheson after her marriage in 1898 to Kenneth Gordon Matheson (1864–1931); two sons, two daughters;

(4) John Seddon (1878–1964); married (1905) L(a)udie Lewis Bibb (b. 1876, d. after July 1930);

(5) Henry Wise (changed to Wyatt in 1881) (1880–1950); married (1913) Emma B. Nicholls (?) (1881–1958);

(6) Charles Preston (1888–1930);

(7) Reginald Scott (1895–1979); married (1921) Julia Bolton Walker (b. c.1898 in Georgia, d. 1986); one daughter (Julia Bolton Fleet; 1922–2005).

Leigh Robinson Gignilliat graduated with distinction successively from the Emerson Institute at Washington, DC, and then from the Virginia Military Academy where he was Private Secretary to the Superintendent, Captain of one of the Companies, President of the Literary Society, Editor of the College publication and Valedictorian of his class. He also received an MA degree from Trinity College. His first service in active life was with the Corps of United States Engineers who were engaged in road work and bridge building in Yellowstone National Park. He then returned for a few months to the family home in Georgia before accepting the position of Commandant of Cadets at the Culver Military Academy, Indiana, from 1897 to 1910, when he succeeded his father-in-law as Superintendent, a post that he held until his retirement in 1939. Their combined efforts placed the Culver Military Academy second only to the United States Military Academy at West Point. During World War One he served as a Brigadier-General on the Staff of John J. Pershing (1860–1948), the GOC (General Officer Commanding) the US Expeditionary Force in France.

Leigh Robinson Gignilliat (1875–1952)

(From the Culver Academy Roll Call yearbook 1905)

Kenneth Gordon Matheson graduated from the South Carolina Military College, now Citadel College, Charleston, South Carolina, in 1885, and received an MA from Leland Stanford Jr University in 1897. He began his educational career as Commandant of Cadets at the Georgia Military College and then taught at the University of Tennessee. From 1896 to 1905 he was Professor of English at the Georgia School of Technology, of which he was a very successful President from 1905 to 1922. From 1922 until his death in 1931 he was President of the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry, Philadelphia (now Drexel University, a private research foundation), during which time he was credited with adding about $3 million to the plant, endowment and equipment fund, tripling the enrolments, enlarging the Faculty, and improving educational standards. During World War One, he was divisional chief of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in the Langres area. One of his most important contributions as an educator was the extension of the co-operative scheme of education so that, by the end of the 1920s, about 200 manufacturing establishments, public utilities and mercantile firms in the Philadelphia area were co-operating with the Drexel Institute in five-year courses in Engineering and Business Administration. At the time of his death, Matheson was President of the Association of College Presidents of Pennsylvania, a member of the Board of the Presbyterian Hospital, a Trustee of Princeton Theological Seminar, a Director of the Thomas W. Evans Museum and Dental Institute of the University of Pennsylvania, and a member of the Educational Committee of the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.

Kenneth Gordon Matheson (1864–1931)

John Seddon was awarded a BA and an MA at the University of Virginia before returning to Culver College as an Instructor. He later became its Headmaster.

John Seddon Fleet (1878–1964)

(From the Culver Academy Roll Call yearbook 1943)

Henry Wise/Wyatt served in the US Army in the Philippines before World War One and in France during the war itself. He rose to the rank of Colonel and became the head of the Reserve Officer Training Corps at Amherst College, Massachusetts.

Charles Preston suffered serious brain damage during a school football match and had to be cared for clinically for the rest of his life.

Reginald Scott obtained a degree in Mechanical Engineering at the Georgia School of Technology in 1916 before serving as an artillery officer in World War One. After the war he became a financier and investment banker in Georgia, but he finally made his fortune through the Rocket Chemical Company, in which he was one of the seven co-developers of WD40, the widely-used and multi-purpose rust prevention agent and lubricant. The product was originally designed to protect the Atlas ICBM, but in 1958 it was sold for the first time on the open market in San Diego and in 1970 the single-product company changed its name to WD-40 Co. The company went public in 1973 and on the very first day the stock price grew by 61%. The product turned out to have thousands of uses and by 1993, four out of five US households were using it and millions of cans were being sold every week.

Reginald Scott’s only daughter, Julia Bolton Fleet, who, like both her parents, believed deeply in the value of rigorous education, took over the running of the Reginald S. and Julia W. Fleet Foundation after her mother’s death in 1986, and because of the family connection, decided to include Magdalen on the long list of educational causes and institutions that were supported by the Foundation. Between 1987 and her death in 2005, a period during which she made frequent visits to Magdalen, Julia Bolton, who was known at Magdalen as Miss Fleet, bequeathed a total of $4,850,650 (£2.769 million) to the College in order to establish two Tutorial (Fleet) Fellowships in Politics and Modern History and the part funding of a Fellowship in Economics. This generosity made her the greatest cash donor to Magdalen since the College’s foundation, and to show the College’s gratitude she was made a Waynflete Fellow in 1988. Interestingly, as late as the 1970s, Reginald Scott continued to advocate that Fleet Fellowships, like the original Rhodes Scholarships, should be awarded “not entirely on scholastic achievement but on general qualities of character and leadership as well”.

Wife

In 1917 Fleet married Cecil Lyall (b. c.1880 in Islamabad, d. 1975), later Lady Matheson after she became the third wife (m. 1931) of Sir Roderick Mackenzie Chisholm Matheson, Baron of Lochalsh (1861–1944). Cecil was the fourth daughter of Sir Charles Lyall (1845–1920), KCSI, CIE, FBA, a retired Indian Civil Servant and Britain’s foremost expert on Arab languages and literature. The couple lived at 96, Palace Gardens Terrace, Kensington, London W8. Her second husband was a first cousin of her father.

Cecil Fleet (neé Lyall)

(Photo courtesy of Michael O’Brien)

Education and professional life

Although little is known about William Alexander Fleet’s time at Culver Academy, Indiana, where he studied from c.1896 to 1900, was known as “Billy” and was awarded the Academy’s Scholarship Medal, it is clear that his easy-going, generous nature, handsome features, powerful athletic frame and ability to charm people of all ages by his ebullient love of life were the keys to his popularity. In 1919 the post of the American Legion at the Academy was called the William Alexander Fleet Post in his memory.

Photo of William Alexander Fleet taken from a group photograph of 1907

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

From 1900 to 1904 he studied at the University of Virginia, where he was awarded a BA and an MA. He was also the University’s champion in both singles and doubles lawn tennis, an officer of his fraternity, and a member of the drama society – and here once again his attractive social graces, the mark of a Southern gentleman, carried all before him. Taken together, his upbringing and attributes ensured that he would be selected as the first American Rhodes Scholar from Virginia and he duly arrived in Oxford in autumn 1904, furnished with a Scholarship that paid handsomely at £300 p.a. and ran for three years, as one of the first ever cohort of Rhodes Scholars. Fleet had probably chosen to read Classics at Magdalen because this was the College with which his family claimed ancestral connections. But Fleet’s decision would also bring him under the aegis of Thomas Herbert Warren (1853–1930; knighted 1914), Magdalen’s President from 1885 to 1928, at a time when he was nearing the zenith of his career. Warren was a friend of Lord Alfred Milner (1854–1925), one of Rhodes’s executors and a Trustee of the Rhodes Scholarships, and he had taught Geoffrey Dawson (né Robinson; 1874–1944), who had become Milner’s Assistant Private Secretary in 1901 when Milner was High Commissioner of South Africa. But Warren was not just an early supporter of Rhodes’s scheme, he promoted it with great conviction while he was Vice-Chancellor of the University (1906–10) because he shared Rhodes’s belief in Oxford’s divinely sanctioned role within the imperial scheme. What he said of Tennyson, possibly his favourite poet, applied equally to himself: “[He] grew with the growth of the Empire” and viewed “the expansion of England” and the concomitant “liberation of the modern world” as aspects of “a slow aeonian movement of evolution” whereby the world “was for ever bettering itself and moving toward one far-off divine event”.

Fleet matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 18 October 1904, having, as a Rhodes Scholar, been exempted from Responsions. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1906 (Classical Literature and Holy Scripture respectively) and was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations (Honours) on 14 April 1906. But he did not go on to take Greats since this would have required a fourth year at Oxford, and anyway, neither his College, nor the University, nor the Rhodes Trustees expected this of him. So he was able to take a BA and an MA on 7 July 1917 only because the War Decree of 12 June 1917 had exempted him from the need to take further examinations. During his first term at Magdalen, Fleet showed his willingness to adapt to the most important local customs, especially the obsession with competitive sport, and rowed in the winning Freshmen’s IV. As such he was a member of the Magdalen College Boat Club at the same time as E.H.L. Southwell, R.P. Stanhope, A.G. Kirby and L.R.A. Gatehouse. And in 1906 he proved the strength of his willingness for the second time, when he gained a Half-Blue in lawn tennis. Consequently, it is not hard to understand why Fleet and Warren got on so well. In Warren’s eyes Fleet must have exhibited the manliness and sporting prowess that he valued so highly as defining features of the all-round “Magdalen man”. Conversely, Oxford’s sense of tradition and commitment to a gentlemanly code of behaviour must have made considerable sense to someone who had been reared on a “post-memory” of the chivalric code of the Old South which the Civil War had largely swept away. This is precisely what Sir Francis Wylie (1865–1952), the first Warden of Rhodes House (1903–31), remembered about Fleet when he recorded his impression of him nearly 40 years later: “He had a frank and boyish, I feel inclined to say a guileless face. But there was nothing soft about him […], he was not a great scholar […], it was impossible not to like him. Nor could you take him for anything but what he was, a fine Southern gentleman.” And President Warren wrote of him posthumously:

Oxford is known to be a critical place, and Magdalen had the reputation of demanding a rather rigid conformity to standards of its own. But Fleet disarmed all criticism by a frank enthusiasm, an almost childlike simplicity, an attractive courtesy, and a considerate unselfishness and modesty which, quite without his knowing it, captured the College. For three years he was as much respected and as generally popular as any undergraduate of his time. It is not impossible that the affection of men like him for Oxford and the affection of Oxford for them may have done something to promote the growth of common feeling between the two countries that has ended in the alliance on which the future of the world depends.

Fleet playing tennis at St Moritz in 1906 when he won the tournament

(Photo courtesy of Michael O’Brien)

After leaving Oxford in 1907, Fleet arrived back in the United States at a time when many American universities were being reformed. The curriculum was being modernized, and at progressive universities like Princeton the tutorial system, based on the Oxbridge model, was being introduced. So Fleet accepted a post as a preceptor (tutor) at Princeton where, typically, he won the approval of its austere President, who was an energetic administrator but who, it was thought, would never make a mark outside academia. This was Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), later to be the 28th President of the United States (1913–21), who had become Princeton’s President in 1902. But Fleet stayed at Princeton for only three years, leaving it shortly after Wilson resigned in 1910 to become Governor of New Jersey. He gave his father’s declining health as his reason for doing so and returning to Culver College, but his real reason seems to have been his disappointment that a serious political clash at Princeton between the representatives of old-fashioned honour and the representatives of modern industrial wealth should have caused the defeat of the former – and brought about Wilson’s departure. But Fleet was not completely happy at Culver College either: he missed the lively, cosmopolitan atmosphere of Oxford, and considered returning there and reading for “Greats” on the grounds that the course required original thought rather than second-hand ideas from books. But his good intentions came to nothing, and the experience was an indication of how difficult it was for Rhodes Scholars from rural backwaters to return to the lethargy of small town life.

William Alexander Fleet

(Photo courtesy of Michael O’Brien)

War service

When war broke out, Fleet was in England for the final of the Davis Cup, and his voyage home provided him with an introduction to hostilities as the liner Philadelphia manoeuvred to avoid U-boats and was stopped for inspection by a French torpedo boat. Although Fleet expected the United States to enter the war on the side of the Allies, he became disappointed and frustrated when his friend, Woodrow Wilson, showed great reluctance to become involved. So, like many other Americans who favoured intervention, Fleet fell back on urging the government to prepare for the possibility of conflict and in Spring 1916 he travelled to Washington as a member of a delegation that was advocating the establishment of officer training schemes for graduates who were teaching in military academies. By this time, Fleet was so desperate to get into the war that he sought naturalization as a British subject in order to secure a commission. His application was supported by Colonel Sir Henry Streatfield (1857–1938), the Commanding Officer of the Grenadier Guards, but when Fleet learnt that five years’ residence were necessary to justify his request, he decided to swear that his grandfather, Dr Benjamin Fleet, had been born in England and that Captain Blomfield of the Artists’ Rifles, the collective name of that part of the huge London Regiment composed of 1/28th (County of London) Battalion, the 2/28th (County of London) Battalion and the 3/28th (County of London) Battalion, would accept such a statement from him without enquiring further. As this decision would have involved considerable technical difficulties over nationality and neutrality in the United States, Fleet let it be known that he was going to England to join the Red Cross, as was perfectly possible under American law. But he gave his real reasons for wishing to join up in a letter that he wrote to Warren in Summer 1916: “They gave me such a good time at Oxford and were such good fellows and now they are fighting and dying and I must fight with them.”

William Alexander Fleet

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

After successfully negotiating the above difficulties, Fleet applied for admission to the Artists’ Rifles on 2 October 1916, a year before G.W.S. Alington. This unit was a well-known conduit for well-educated middle-class boys who wanted to obtain a commission in the British Army, and Fleet confided to Warren that his way had been well prepared by “letters written in my behalf by Mr Wylie and Colonel Stenning of the Oxford Cadet Battalion” and that the Commanding Officer of the Grenadier Guards had offered him a commission if he was recommended. Obviously confident of his own prowess when it came to warfare, Fleet continued: “I have just finished a five year term of service in the military school at home […] and am free to stay here until the end of the War.” Finally, he revealed the lengths to which he had gone to get involved in the action: “You may perhaps wonder about the matter of my nationality. I must admit, confidentially, that I said that my father’s father was born in England. This was not true but I had no qualms of conscience about it, since it was the only way I could get a commission.” Not that concealment required much effort: on his attestation papers he gave his profession as “Schoolmaster”, his place of birth as Columbia, Missouri, and claimed further down the page that he was British by birth and had a British father, and although he owned to have studied at “Oxford University”, he omitted to make any mention of his Rhodes Scholarship. Moreover, F.J. Wylie (1865–1952), who contributed and signed the compulsory reference for Fleet on the following page of the attestation form and who was the first Warden of Rhodes House (1903–31), styled himself as “Oxford Secretary to the Rhodes Trustees”! Similarly, although three medical certificates would give Fleet’s height as 5 foot 8¾ inches, he claimed on the form to be 5 foot 9½ inches, presumably because he was aware of the Guards’ tradition of tall guardsmen. But no-one seems to have taken much notice of these small infelicities and he was admitted as an officer cadet on 3 October 1916.

Fleet, third from right in the middle row, probably soon after he joined the Artists’ Rifles (Courtesy of Michael O’Brien)

But by the time that Fleet joined the Artists’ Rifles, the 1/28th Battalion had merged with the original 2/28th Battalion, and the 3/28th Battalion had been re-designated as the 2/28th Battalion. The two surviving Battalions were not Line Battalions, but Senior Officer Training Battalions, two of the few that had been selected to offer such fast-track courses, with the 1/28th based at St-Omer, France, and the 2/28th (No. 15 Officer Cadet Battalion) based at Hare Hall Camp, Romford, Essex, since March 1916. So in October 1916 Fleet began a short (four-week) officer training course as a member of ‘C’ Company of the 2/28th Battalion, and in mid-November 1916 he came to see C.C.J. Webb at Magdalen in the uniform of that Regiment. On 18/19 November 1916, Webb noted in his Diary that Fleet had “got into the British Army by affirming (falsely) that his grandfather was British-born. This he regards as a mere technicality, wh[ich] in no way offends his conscience.” Training must have gone well for Fleet for after ten days he thought it likely that he would be sent to the 1/28th Battalion in France as one of 150 reinforcements. But a few days later he reported that he had been held back from the “French Draft” because of his desire to join the Grenadier Guards, for which his athleticism, ability to speak French, expertise as a horseman, military background and membership of the “Oxford network” made him a highly suitable candidate. So once he had completed his basic training on 15 January 1917, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards (London Gazette, no. 29,910, 19 January 1917, p. 813) on the following day and posted to the Regiment’s camp at Tadworth, Surrey, where he became a member of No. 3 Company. As he was 33 and had received what was commonly known as a “grand-dad commission”, Fleet was much older than the average subaltern. Nevertheless, the next eight months would be among the happiest of his life, for he was an officer in a regiment that he “most firmly and confidently” held to be the best in the British Army, not least because it “gives its officers a good deal of training”, and he expressed the hope that he would go out to France in June 1917. This was somewhat optimistic since by 28 June 1917 he was only half-way through an eight-week course of field training with the Grenadier Guards.

Nevertheless, Tadworth’s proximity to London allowed Fleet to retain his wide circle of friends, a situation that improved even more when he was transferred to Chelsea Barracks, in a fashionable part of London. Here, his particular attention was drawn to Cecil Lyall, the fourth daughter of Sir Charles Lyall, KCSI, CIE, FBA, Britain’s leading authority on the Arab world at the India Office. The Lyalls were a truly “Imperial” family: Cecil had been born in Pakistan, in what is now the city of Islamabad but was known then as Lyalltown in honour of her father, and her elder brother, Charles Elliot Lyall (1877–1942; OBE 1919), a Balliol man like his father, would go on to be the Governor of a Sudanese province. Her younger brother, John (b. 1886, d. 1955 in South Africa), had been a contemporary of Fleet’s at Oxford (Exeter College; 1904–07, 4th class degree in Modern History); he served in the Indian Army Reserve of Officers during World War One, and Fleet got to know Cecil when John was competing in a tennis tournament in St Moritz, Switzerland, in Summer 1906. Fleet and Cecil married on 1 August 1917 at Holy Trinity Church, Brompton, London, and moved into a terraced house close to her parents, but the few days that followed were to be the only ones that resembled a normal married life.

On 11 August 1917 Fleet embarked for France, where, according to the Battalion War Diary, he and two other ranks (ORs) reported for duty on 21 August with the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, part of the 3rd Guards Brigade in the Guards Division. The Battalion was recuperating from its part in the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (cf. D. Mackinnon and J.F. Worsley) and training at Putney Camp, somewhere near the Franco-Belgian frontier between Proven in Belgium and Herzeele in northern France. On 1 September, the Battalion went into line for four days and was subjected to high explosive and gas shells, to which, according to the Battalion War Diary, Fleet fell victim on 5 September. As a result, he spent three weeks in a military hospital and a further three weeks convalescing at the American Women’s Hospital for Officers in Lancaster Gate, near his London home.

During his absence, the Battalion continued to train at various camps until the evening of 11 October, when it went into the front line and took up position in preparation for an attack that was scheduled to begin at 05.25 hours on the following day, the opening day of the phase of Third Ypres that is known as the First Battle of Passchendaele, when Haig tried yet again to capture Passchendaele Ridge so that the Allies could push through to the north-east. The attack was unsuccessful and by the time the Battalion was relieved on 13 October, it had lost three officers and c.236 ORs killed, wounded and missing during the previous three days. The Battalion then reorganized and trained in Belgium until 12 November, when it began a long march southwards to the battlefields of the Somme, finally arriving at Achiet-le-Petit, about eight miles north-east of Albert, on 19 November. On 21 November it was transported by bus to Rocquigny, c.16 miles east-north-east of Albert; from there it route-marched further eastwards to the village of Flesquières, five miles south-west of Cambrai, where it took up positions in the trenches just north-east of the village. From 25 November to 3 December 1917, the 1st Battalion took part in the Battle of Cambrai, losing N.G. Chamberlain at Gonnelieu on 1 December. But on 5 December 1917, the Battalion was moved by train from Étricourt-Manacourt to Saulty, 11 miles south-west of Arras, well to the rear of a quiet sector of the front. It then marched a further two miles north-north-west to the village of Sombrin, where it rested. On 11 December it marched to the east of Arras, where it alternated five-day stints in the front line with training in Arras until 22 March 1918, i.e. the day after the beginning of a series of major German attacks that are known collectively as either the Ludendorff Offensive or as Operation Michael. Fleet came back to the Battalion in the second half of December 1917, together with five other officers and 700 ORs.

On 22 March 1918 the Battalion was taken by bus to the area of Mercatel, five miles south of the centre of Arras, and then positioned at Boiry-Becquerelle, a couple of miles east-south-east, where, on 24 March, Fleet’s No. 3 Company was attacked in force by carefully trained assault troops who came from Hénin-sur-Cojeul and the high ground to the north-west of that village and who were beaten off by heavy enfilading fire. On 25 March, the Battalion spent a fairly quiet day at Boiry-Becquerelle, but at 23.30 hours the front-line trenches were evacuated and in a carefully conducted, disciplined withdrawal, Fleet’s Battalion was pulled back just west of the Arras–Bapaume road to the village of Boisleux-St-Marc, where, at 07.20 hours on 26 March, a report was received that the enemy could be seen advancing in large numbers. The Germans attacked at 22.00 hours, and the fighting continued until about 14.00 hours on the following day. On 28 March Fleet’s Battalion withdrew a short distance south-westwards to the neighbouring village of Boisleux-au-Mont where it spent a quiet 48 hours until, during the night of 29/30 March, it took up defensive positions along the north–south railway embankment. Here, from dawn until 10.30 hours, it was exposed to a heavy softening-up barrage by artillery, trench mortars and machine-guns, and then a frontal assault by mass columns of German infantry who advanced along the sunken road until they were driven back yet again by enfilading fire and a counter-attack from Fleet’s Company after vicious hand-to-hand fighting. The Battalion held its positions on the railway embankment until 2 April, rested for a day at Blairville, about three miles over to the west, and returned to the trenches at Boisleux-au-Mont on 4 April. On 5 April, it was subjected yet again to a heavy bombardment; on 8 April it suffered a gas attack; and on 9 April it was relieved and withdrew yet again to Blairville. From 10 to 14 April it was back on the railway embankment, and on the final day of this stint, in a sector that was becoming increasingly quiet, Fleet took a patrol out into no-man’s-land to investigate a German machine-gun post. Although they found that the strong-point was unoccupied, they returned with a German rifle which, together with other weapons and equipment discovered by other patrols, suggested that the unit facing them had been demoralized by their failure to break through and withdrawn. The Battalion was then withdrawn to billets in the small town of Barly, c.13 miles to the west, where it trained until 23 April, when it marched five miles south-westwards to the village of Bienvillers-au-Bois, and by 26 April it was in the trenches at Quesnoy Farm, just to the east of that village and opposite the village of Courcelles-le-Comte, in the open country between Monchy-au-Bois and Bucquoy where there had been fierce fighting during the previous five weeks.

By 29 April patrols were finding that the Germans had become very passive, were sending out no patrols themselves, and were starting to pull back to the east. So over the next 17 days, during the Battalion’s stay in the trenches or billets at or near Quesnoy Farm, German activity dwindled until it was “practically nil”, and on 17 May 1918 Fleet’s Battalion was moved back into reserve several miles to the west-north-west. On that evening Fleet attended a Battalion concert party, after which he returned to the tent that he shared with three other officers. But during the early hours of the morning there was an air raid on the British encampment, during which six bombs were dropped, one of which landed on the tent, killing Fleet, aged 34, and killing or mortally wounding the other occupants: Lieutenant George Edward Archibald Augustus Fitz-George Hamilton (1898–1918), aged 19, Second Lieutenant Sydney Jasper Hargreaves (1898–1918), aged 19, and Lieutenant Guy Dalrymple Neale (b. c.1879 in India, d. 1918), aged 39. The Battalion War Diary makes no mention of the incident. Fleet and Hamilton are buried in Warlincourt Halte British Cemetery, Saulty; Graves XII.B.7 and XII.B.6 respectively. Fleet left £2,243 11s. 2d.

Warlincourt Halte British Cemetery, Saulty; Grave XII.B.7

Fleet’s Commanding Officer, Colonel the Viscount Gort, VC (1886–1946), later the GOC of the British Expeditionary Force (1939–40), later wrote of him: “Anything I ever asked him to do was accomplished by him with total disregard to his own safety and he always set a magnificent example to us all.” Back in Oxford, C.C.J. Webb wrote in his diary on 25 May 1918:

Grieved by news of W.A. Fleet’s death in action. He had come over before the USA came into the war, to fight for us. The last I had heard from him was an acknowledgement of our wedding present at Xmas time. He asked me once when an undergraduate in his simple American way, when I had been talking of the obvious difficulties (as I thought then) of squaring virtue with pleasure – “But surely, Mr Webb, if one is good, one will be happy?” I think he found his happiness easily in what was good – in friendship and honour – and he has died in a good cause.

Fleet’s death probably distressed Warren even more, for, as he stated in a letter to Fleet’s widow: “we all liked him from the first and soon came to love him deeply”, and then, in a comment which revealed how closely Fleet had become one of his ideal Oxford men, he added: “he made himself indeed one of my heroes”. And an obituary that Warren published in The Oxford Magazine on 21 June 1918 said:

He kept in constant touch with the College when he returned to America, and after the outbreak of war his letters were frequent. But he was not content merely to write. In the summer of 1916 he arrived unexpectedly in England to do, as he said, what he could to help. His persistency surmounted all technical difficulties […] No young Englishman has done more for England than he did, for none can do more than to die for her, and none has done it more enthusiastically and spontaneously. Such a life and such a death sets a seal to the alliance between his country and ours.

Fleet’s name is included on the Memorial Plaque that is to be found on the 4th Floor of the five-star luxury hotel called Pershing Hall (49, rue Pierre Charron, 8th Arr., Paris) and commemorates the 151 members of Princeton University who were killed in action during World War One

Like so many other women of her generation, Cecil Fleet was obliged to carry on, and within a few years she was caring for her mother, who was badly affected by the death of Sir Charles Lyall in 1920. In 1930 she became the third wife of Sir Roderick Mackenzie Chisholm Matheson, 4th Baronet of Lochalsh (1861–1944), who as noted above was her father’s first cousin and a businessman based in London. After his death she lived in Gloucestershire until her death in 1975 at the age of 96.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

To a considerable extent, the above biography is based on the two items by Michael O’Brien listed below. Mr O’Brien very kindly gave the editors permission to use his work and adapt it to their needs, and we would like to express our gratitude to him for his generosity.

**Michael O’Brien, ‘William Alexander Fleet’, in Death did not Divide them: The American Rhodes Scholars who died in World War One (Brighton: Reveille Press, 2013), pp. 53–80; also (in shortened form) in Magdalen College Record (2011), pp. 106–15.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Personal Notes: Second Lieutenant W.A. Fleet’ [brief obituary], The Times, no. 41,802 (29 May 1918), p. 9.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘An American Rhodes Scholar’, The Times, no. 41, 805 (1 June 1918), p. 2.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 24 (21 June 1918), p. 346.

Ponsonby (1920), ii, pp. 236, 237, 353–60; iii, pp. 18–22, 240.

[Anon.], ‘Dr. K.G. Matheson, Educator, is Dead’ [obituary], The New York Times, no. 25,523 (30 November 1931), p. 17

Beverley Fleet, Virginia Colonial Abstracts, 3 vols (Baltimore [Maryland]): Genealogical Publications Co. Inc.: 1988), pp. 478–9.

John Gregory Selby, Virginians at War: The Civil War Experiences of Seven Young

Confederates (American Crisis Series, vol. 8) (Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, 2002).

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/463-478 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to W.A. Fleet [1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/53.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161; MS. Eng. misc. e. 1163.

WO95/1223/1.

WO339/85413.