Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 28 February 1897

Died: 17 September 1918

Regiment: Northumberland Fusiliers

Grave/Memorial: Post Office Rifles Cemetery 3.F.10

Family background

b. 28 February 1897 at 84 St Mary’s Road, Cowley St John, Oxford, as the sixth of seven sons of Joseph William Quarterman (1859–1922) and Emma Christina Quarterman (née Acott) (c.1857–1921) (m.1885); baptized 25 March 1897 in St Clement’s Church, Oxford. At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at 11 Speedwell Street, St Ebbe’s, Oxford; and at the time of the 1911 Census the family was living at 25 Commercial Road, Oxford.

Parents and antecedents

Quarterman’s father was the son of Charles Quarterman (1822–1913), a journeyman bootmaker. Both of Quarterman’s parents worked as scouts for Oxford colleges: his father for Keble and then for Magdalen, his mother for either Merton or Corpus Christi. Quarterman’s father was, when a young man, a very good all-round athlete, performing very creditably on sports days organized by the Oxford Colleges Servants’ Society and the Oxford Churchman’s Union.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Charles (1886–1928); married (1914) Emily Hannah Clarke (1881–1949); two children;

(2) Frank (1888–1943); married (1914) Annie Woodward (1890–1975); one son, three daughters;

(3) Clive Henry (later Revd) (1890–1942); married (1916 in Fort Chipewyan, North-West Territories, Canada) Alice Jane Wylie (1895–1989); two children;

(4) Alfred (1892–1944); married (1915) Maude Maria Surman (1890–1972); one son;

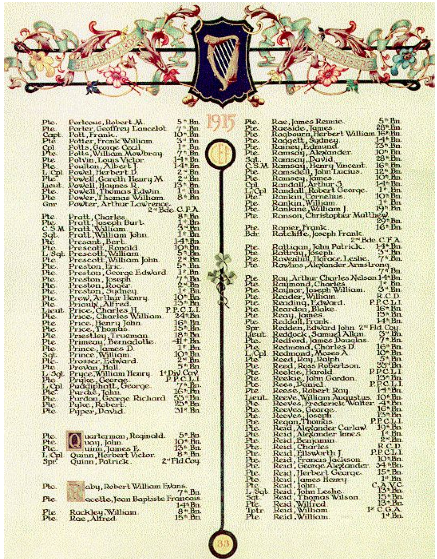

(5) Reginald Charles (b. 1893, d. 8 May 1915 at Hazebrouck of wounds received in action near Ypres); served as a Private with the 5th (Western Cavalry) Battalion, 2nd Canadian Brigade, The Saskatchewan Regiment, Canadian Expeditionary Force;

(6) Christopher (1900–1951); married (1924) Elizabeth Sarah Bulbeck (1884–1971); one son.

Charles, who was a candidate teacher at 14, became a schoolmaster and ended his professional life as the headmaster of a primary school in Wargrave, Berkshire. He joined the 4th Battalion of the Ox. & Bucks Light Infantry on 8 June 1915, when he was living at 38 Portland Street, Oxford, and quickly rose through the ranks, becoming an Acting Sergeant on 14 December 1915. He was discharged from the Army as medically unfit on 19 August 1916 because of a cartilage injury that he had incurred in 1907: despite an operation on 1 June 1916, the injury failed to heal and Charles experienced increasing difficulties in walking.

Frank, who had left school to become a shop boy by the age of 13, was trained as a carpenter and wheelwright; after the war he became a motor body builder in the Cowley car works. He joined the Royal Engineers in London on 15 April 1915 when he was living in Highbury and went to France on October 1915. His military record has survived and during his time as a sapper he was found guilty of minor offences on four occasions: on 3 December 1915 he did not comply with a messing order (two days confined to camp); on 15 August 1917 he failed to comply with an order (docked three days’ pay); on 8 February 1918 he was fined another three days’ pay “for being unknown on parade”; and on 22 August 1918 he was confined to camp for 14 days for not complying with an order. He had one period of leave in England – from 23 September to 2 October 1918.

Clive became a Methodist minister in Canada and was buried in Twelfth Line Cemetery, Rawdon Township, Hastings City, Ontario.

In 1927 Alfred was a motor car body finisher living in Osney, Oxford, when his only son, Ronald Carlile Quarterman (1918–27), died suddenly in Brighton. An inquest found that the boy had a congenitally weak heart that failed as a result of stress caused by a prolonged bout of vomiting.

Christopher founded the Evangelical Bookstore in St Clement’s, Oxford.

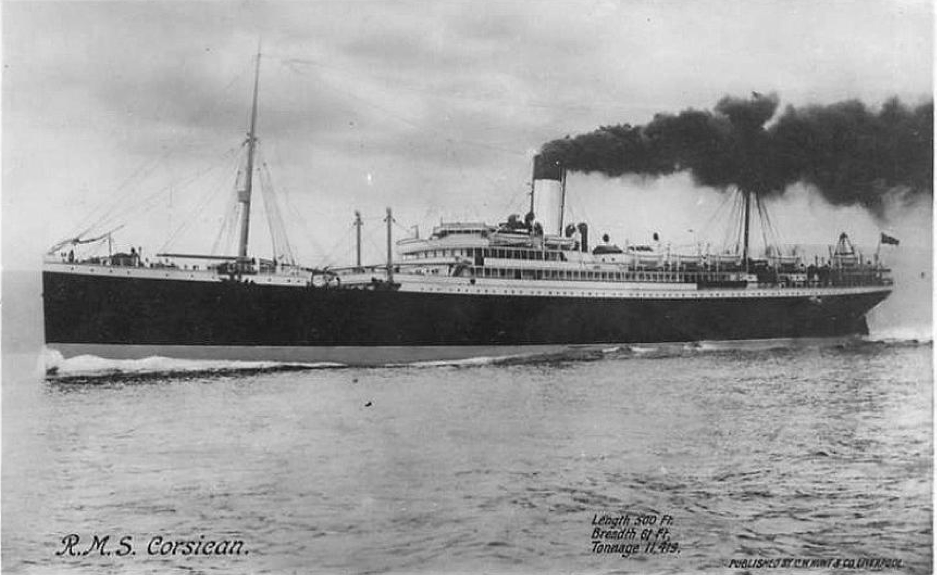

Reginald emigrated from Liverpool on the RMS Corsican (1907; wrecked on Freel Rock, 20 miles west of Cape Race, Newfoundland, on 21 May 1923, but with no loss of life) on 20 April 1911 and arrived at Quebec on 30 April. He attested on 17 September 1914, describing himself as a “Farmer”, and was assigned to ‘B’ Company of the 5th (Western Cavalry) Battalion, the Saskatchewan Regiment, which, after training for several months in England, disembarked at St-Nazaire, France, on 14 February 1915.

RMS Corsican (1907-23)

The 5th Battalion was in the 2nd (Canadian) Infantry Brigade and part of the 1st (Canadian) Division that was commanded by the British Lieutenant-General Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson (1859–1927). Together with the 27th and 28th (British) Divisions, the 1st (Canadian) Division formed Sir Herbert Plumer’s V Corps. The 5th Battalion had its introduction to trench warfare in the Ypres Salient in early March 1915, and was in the front line near Gravenstafel, on the easternmost cusp of the Ypres Salient, with effect from 19 April, with the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, part of the 28th Division, on its right. On 22 April 1915, the opening day of the Second Battle of Ypres, the 2nd (Canadian) Brigade escaped the worst effects of the chlorine gas shells which the Germans used for the first time on that day, and suffered only 11 casualties killed, wounded or missing. Gas was, however, used with devastating effect against the mainly French and French Colonial troops who were defending the northern rim of the Ypres Salient, forcing them to flee in great disorder from such key places as Pilckem Ridge and Passchendaele and pushing back the Allies’ defensive line. For the next four days, during the so-called Battle of Gravenstafel Ridge, the 5th Battalion, which was positioned roughly opposite Sint Jaan, was involved in very fierce fighting and lost 300 of its members killed, wounded or missing, mainly to heavy artillery bombardments which included gas, for which the troops were poorly prepared. On 26 April the 5th Battalion was withdrawn to support trenches near Sint Jaan, and on the evening of 27 April, by when the Germans had pushed back the eastern rim of the Salient by 3–4 miles, the 5th Battalion was pulled back to rest in bivouacs on the bank of the north–south Ypres Canal, just to the east of the battered town of Ypres. It stayed here until 5 May, taking a steady number of casualties every day from persistent German shelling, and on 6 May 1915 its remnants marched 17 miles southwards to Outersteen, a hamlet to the south of Bailleul, where everyone was “exhausted on arrival”. A non-commissioned officer was accidentally wounded on 6 May, but Reginald was a Private, and no-one at all from the 5th Battalion was wounded or killed on 7 or 8 May, the day given as the date of his death. So Reginald must have been badly wounded during the fighting that had taken place during the preceding 17 days – one source gives the date as 2 May – and then been taken to one of the many hospitals and casualty clearing stations in Hazebrouck, where he is buried in St-Éloi Cemetery (Communal Cemetery), Grave II.D.33, together with Private W.H. Dodd of the 1st Battalion, the York and Lancaster Regiment, whose date of death is also given as 8 May 1915. On this particular day, the 1st Battalion suffered an enormous loss of life – including all its officers bar one – when it made two abortive attempts to re-take trenches at Zonnebeek (south-east of Frezenberg), and even when the Battalion was down to 53 other ranks (ORs), the Brigadier asked it to make a third attempt at 00.30 hours on 9 May. The joint grave probably indicates shortage of space in what is obviously a crowded civilian cemetery that was also having to cope with military casualties. The Second Battle of Ypres continued until 25 May 1915.

St-Éloi Cemy (Communal Cemy), Hazebrouck, Grave III.D.33.

The Canadian First World War Book of Remembrance, p. 33.

The Book was created by James Purves (1877-1940) of London, Ontario, and it was completed after his death, by which time only one page was fully illuminated and illustrated, by Alan Beddoe (1893-1975), Purves’s assistant for many years. It now rests upon an altar in a Memorial Chamber in Canada’s Peace Tower on Parliament Hill, Ottawa.

Employment and war service

Quarterman began work at Magdalen in October 1911 as a Bicycle Assistant, when he was 14. He continued in that job until, “being desirous of doing his duty and inspired by the earlier example of his four elder brothers”, he attested under the Derby Scheme in autumn 1915 and was called up on 1 August 1916. At first he was assigned to the Royal Garrison Artillery, very probably to the 132nd (Oxford) Battery, which had been formed in Oxford on 26 May 1915 and of which R. Roberts, another of Magdalen’s employees, was already a member. But the Battery had left for the Salonika Front by October 1916, and according to a letter from Quarterman’s father to President Warren, William was soon transferred to the 1/5th Battalion (Territorial Force), the Northumberland Fusiliers. This Battalion was part of 149th Brigade, in the 50th (Northumbrian) Division (TF), had disembarked in France on 14 May 1915 and had lost a large number of its members during the Battle of the Somme (1 July–18 November 1916): on 16 November 1916 the War Diary records that it was down to one officer and 220 men. Quarterman’s father also told Warren that William had joined the 1/5th Battalion in France in early 1917 and that, when the Germans pulled back from their old front line in March 1917 and took over the improved defences of the Hindenburg Line in March 1917, his son had taken part in the subsequent advance to the French cathedral town of St-Quentin. This was a pivotal point within the Hindenburg Line which the Germans cleared of French civilians between 1 and 18 March 1917.

Unfortunately, the Battalion War Diary puts three question marks over Joseph William’s account. First, although it does record that a draft of two officers and 40 ORs had reported for duty with the Battalion on 9 December 1916, it does not record the arrival of other such drafts during the rest of 1917, even though the 1/5th Battalion must have been nearly brought up to strength once more during this period. Second, it shows very clearly that between 19 November 1916 and 26 June 1917, the day when the 1/5th Battalion was involved in a Brigade-level attack on the Germans, it experienced a very low rate of casualties because it spent a relatively short time in the trenches, mainly near Arras after the end of the Second Battle of Arras. And third, the history of the 1/5th Battalion’s whereabouts and activities between 19 November 1916 and 18 October 1917 is that of a new Battalion of young and inexperienced recruits being toughened up and gradually prepared for the serious fighting involved in trench warfare that awaited it in the Ypres Salient in late October 1917. Thus, the Battalion War Diary for 1917 starts by recording how, between 26 January and 11 April, the 1/5th Battalion trained by route-marching northwards in a huge clockwise circle and, where possible, spending brief periods in the trenches along the way. It began its march on 1 January 1917 at Flers, about seven miles north-east of Albert; by 8 February 1917 it had dropped down to Méricourt-sur-Somme, some seven miles south of Albert; by 31 March 1917 it had route-marched westwards to Bertangles (just north of Amiens); by 10 April 1917 it had reached Wanquentin (around seven miles west of Arras); and it finally arrived at the trenches just east of Arras on 11 April 1917 where it did a stint until 30 April 1917, when it pulled back c.17 miles south-westwards, down the N25 to the neighbouring villages of Mondicourt and Souastre. Then, between 18 May and 24 June 1917, the Battalion seems to have shuttled forwards and backwards along a line between Mondicourt and Chérisy, some 22 miles to the north-east, but went no further eastwards than the trenches at Chérisy (24 June 1917). So while it is possible that William Victor joined the 1/5th Battalion as early as December 1916, he could have joined it at any point during the first six months of 1917 – or even later.

William Victor Quarterman (1916). He is wearing the cap-badge and lanyard of a Gunner in the RA.

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

As noted above, the Battalion saw its first piece of real action when it took part in a Brigade attack on the German trenches at 02.00 hours on 26 June 1917, i.e. over four weeks after the end of the costly and indecisive Second Battle of Arras (9 April–16 May 1917). It then rested nearby for a while before spending the period from 2 to 18 July in the trenches at Héninel, about seven miles south-west of Arras. It then stayed in the same general area, which was by now fairly quiet, manning the trenches at various places and resting in billets until 6 October 1917, when it marched around nine miles south-westwards from Chérisy to Courcelles-le-Comte in order to rest there for 12 days. On 18 October it marched further southwards to Miraumont via Achiet-le-Grand and Achiet-le-Petit, entrained, and arrived at Cassel, about seven miles east of the Belgian border in northern France, at 22.00 hours on the same day. On the following day the Battalion marched eastwards via Proven to Boesinghe, north of Ypres. And from there it marched another seven miles north-eastwards until it took over the line near the tiny village of Schaap-Balie, around three miles north of Poelcapelle and a mile south of the Houthulst Forest, where the fighting had already cost many lives earlier in October (see D. Mackinnon, T.S. Arnold, J.A. Ackworth, P.W. Beresford, H.H. Dawes and D.H. Webb). Three days later, at 05.40 hours on the first day of the final phase of the Third Battle of Ypres that became known as the Second Battle of Passchendaele (26 October–10 November 1917), the Battalion participated in the Fifth Army’s four-Division assault across mud-filled lowland swamps whose purpose, as always during Third Ypres, was to secure the ridge that dominated the slope down to Ypres and led out to the north-east onto the Gheluvelt Plateau. The mud was so deadly that wounded men who fell off the duckboard paths just disappeared, and the German artillery and machine-guns were so heavy and accurate that the Battalion’s first two waves took very heavy casualties. As a result, it succeeded in taking only its first objective, and when it was forced to withdraw, 12 of its officers and 439 ORs were killed, wounded or missing. We do not know whether William took part in this carnage, but at some point during his time with the 1/5th Battalion he was, according to his father, badly affected by shell shock and was sent back to Southampton, where he was subsequently treated for nephritis.

Quarterman returned to France once more early in 1918, this time with the 16th (Service) Battalion of his old Regiment, and served yet again in the Ypres Salient, where he contracted trench foot and was again sent back to Eastbourne. According to its War Diary, the 16th Battalion (96th Brigade, 32nd Division) was billeted near the neighbouring villages of Sanghem and Alembon – c.12 miles east of Boulogne and c.14 miles south of Calais – where it trained from 1 to 18 January 1918. On 19 January 1918 the Battalion marched c.13 miles north-westwards through Landrethun-lès-Ardres to the town of Audricq, where it entrained for Elverdinghe, in the Ypres Salient. After several days at Dirty Bucket Camp, in the woods between Ypres and Poperinghe and named after a local cabaret called De Vuile Seule, the Battalion marched to nearby Émile Camp, and then spent time at various other camps until 30 January 1918, when it did two two-day stints in the line near the Staden Railway and Turenne Crossing until 3 February 1918. On 7 February 1918 the Battalion was disbanded and its four Companies were transferred to the 1/4th, 1/5th, 1/6th and 1/7th Battalions of the same Regiment (149th Brigade, 50th (Northumbrian) Division). But the Battalion War Diary records no arrivals of reinforcements or small groups of ORs between October 1917 and the date of its disbandment.

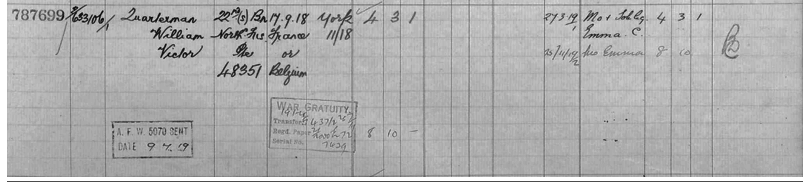

On returning to his depot at East Bolden, seven miles east-south-east of Newcastle-on-Tyne, Quarterman seems to have been attached for a short while to the 20th (Service) Battalion and then transferred to the 22nd(Service) Battalion (Tyneside Scottish) of his old Regiment and sent back to France for the third time in late July 1918. But by this time he had trained as a Lewis Gunner, and he probably disembarked at Boulogne with his new Battalion as part of the 48th Brigade in the 16th Division on 1 August 1918. The Battalion then travelled southward to Desvres, c.12 miles east-south-east of Boulogne, and trained there for three weeks until 22 August, when it was sent eastwards to Noeux-les-Mines, about three miles south of Béthune. After another eight days of training, it went into the front line north of Cambrin, just three miles east of Béthune in the left sub-sector of the Divisional front, from where the Germans were starting to conduct a fighting withdrawal north-westwards. On 6 September the Battalion launched an attack, gained all its objectives, and then rested in billets until 13 September, when it returned to the front line. On 14 September 1918 it advanced to the bank of the Canal d’Aire at ruined Cuinchy, just north of Cambrin, but then withdrew again. On 15 September Quarterman’s Battalion was holding a line of defensive positions leading eastwards from the railway station at Cuinchy, situated just to the left (west) of the bridge across the canal in the top centre of the picture below, and on 17 September 1918, while it was waiting to be relieved by the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Gloucester Regiment, ‘B’ Company successfully attacked the German positions on the elevated railway embankment along the southern side of the Canal d’Aire, taking five prisoners in the process. But at some time between 15.00 and 16.30 hours, having subjected the British to a very heavy bombardment involving many gas shells, the Germans counter-attacked those elements of the Northumberland Fusiliers that were in new positions immediately south of the Canal and pushed back ‘B’ Company’s forward positions, causing them to lose three ORs killed in action and 37 ORs wounded or missing, one of whom must have been Quarterman, aged 21, since his body would not be recovered for another three weeks. But at 23.00 hours and again at 01.00 hours on the following morning, ‘A’ Company of the 22nd Battalion successfully counter-attacked the Germans, taking three machine-guns in the first instance and regaining the lost forward positions in the second, so that it became possible for the 18th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment to effect the takeover by 02.00 hours.

Aerial view of Cuinchy showing the Canal d’Aire, the railway running parallel to the Canal just to its south on an embankment, and the open ground to the right of the bridge. The front line would have run north-south near the right-hand end of this photo. Cuinchy church, dedicated to St Pierre, was, like the rest of the village, completely destroyed in World War One and reconstructed in the 1920s. It is the red brick building just below the railway and to the left of the main road running north-south.

The Canal d’Aire at Cuinchy, taken from a bridge and looking westwards towards the bridge in the distance that is in the centre of the aerial view. On 17 September 1918, the front line was approximately half-way between the two bridges and the picture shows the high railway embankment on the south side of the Canal that was held by the Germans.

By the beginning of October, the Germans were pulling back in earnest, and on 5 October 1918 the 22nd Battalion moved back into Brigade Reserve about two miles south-eastwards to the area of Auchy-les-Mines. They spent the next four weeks cleaning up old trenches and salvaging arms and ammunition, for the whole area had seen fighting since 1914 (see A. Graham Menzies) and it was during this period, on 7 October, that the Battalion’s Chaplain found Quarterman’s body and wrote to his father that he had given it “a Christian burial” where it had fallen. This was the Reverend Walter Greenhalgh (1884–1948), Curate of St Peter’s, Belper, Derbyshire (1919–26), then Vicar of Allestree, Derbyshire (1926–48), a cure of souls of 602 and an annual income of £371 p.a. The body was later transferred to the Post Office Rifles Cemetery, Festubert, Grave III.F.10. This is situated four miles north of the bridge in the photograph along the Rue de Lille (now the Rue Jean Jaurès). Quarterman is not listed on the Nominal Roll of the 22nd Battalion that is at the back of Stewart and Sheen’s history (pp. 222–31). C.C.J. Webb knew William well and noted in his Diary on 18 October 1918: “Wrote to condole with Quarterman on the loss of his son, the second he has lost in the war.” On 20 July 1919 or 1920, William’s father wrote a letter to C.C.J. Webb in which he said: “We feel it an honour to have his name inscribed upon the Roll of Honour in the College Chapel, where he did a little humble service, and the place he really loved.”

Post Office Rifles Cemy, Festubert, Grave III.F.10.

Quarterman’s list of personal effects at the time of his death.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Ternan (1919).

Stewart and Sheen (1999), p. 170.

Steel and Hart (2000), pp. 285–8.

George H. Cassar, Hell in Flanders Fields: Canadians at the Second Battle of Ypres (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2010).

Nicholson (1962).

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1163.

WO95/1975.

WO95/1977/1.

WO95/2398.

WO95/2463.

WO95/2828.

WO95/4795.

On-line sources:

Andrew B. Godefroy, ‘Portrait of a Battalion Commander’, on-line description of the CO of the

Canadian 5th Battalion that includes an analysis of the part played by the Battalion in the Second Battle of Ypres: http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vo5/no2/history-histoire-eng.asp (accessed 17 October 2019).

Canadian Great War Project: The War Diary of the 5th Battalion, the CEF: http://www.canadiangreatwarproject.com/warDiaryLac/wdLacP08.asp (accessed 26 October 2019).

‘Cuinchy, Cambrin & Vermelles’, World War One Battlefields series (includes a very useful trench map of Cuinchy from 1916): http://www.ww1battlefields.co.uk/others/cuinchy-cambrin-and-vermelles/ (accessed 17 October 2019).