Fact file:

Matriculated: 1904

Born: 25 January 1886

Died: 29 June 1916

Regiment: Worcestershire Regiment attached to Royal Munster Fusiliers

Grave/Memorial: Helles Memorial: Panels 104–113

Family background

b. 25 January 1886 in King William’s Town, Cape Province, South Africa, as the only surviving son of John James Irvine (b. c.1842 in Ireland, d. 1887 in London) and his third wife, Elizabeth Wells Irvine (née Symonds) (b. c.1862, d. 1945 in Hendon, Middlesex). The family lived at the Waterford Estate, Kubusi Station, Cape Province, South Africa. At the time of the 1901 Census Harold and his widowed mother were living at Wapdune House, Guildford, Surrey (two servants).

Parents and antecedents

John James Irvine was a merchant and the owner of Waterford Estate, Kubusi Station, Cape Province. An obituary described him as the owner of “one of the most prosperous firms of Cape Colony”, who “spent large sums in farming, both agricultural and pastoral”. He was a major benefactor of the Lovedale Missionary Institute (founded 1841) and a prominent member of Cape Colony’s legislative assembly (House of Assembly) in Cape Town, and in April 1882 he was appointed to the Assembly’s Select Committee, chaired by Cecil Rhodes, that had been set up to investigate the extent of illicit diamond buying in the Colony – one of the Committee’s three members who had no stake in the diamond trade.

Irvine’s maternal grandfather, James Lambert Symonds (1821–1910), was a prosperous Marylebone butcher who at the time of the 1861 Census had three house servants and three butchers working in the business.

Siblings and their families

Half-brother of:

(1) John Dods Pringle (b. 1871 in Bedford, Cape Province, South Africa, d. 1892 in Bedford, England), John James Irvine’s only son with his first wife, Ellen Irvine (née Pringle) (1850–c.1871, who probably died of complications following childbirth) (m. c.1870);

(2) Amy Douglas (b. 1877, d. 1952 in Kensington, London), John James Irvine’s only daughter with his second wife, Amy Irvine (née Douglas) (d. 1878, probably of complications following childbirth) (m. c.1876); Amy’s later name was Medlicott after her marriage in 1905 to the Reverend (later Canon) Robert Sumner Medlicott (1869–1941); two sons, four daughters;

(3) Percival Douglas (b. 1878 in King William’s Town, Cape Province; probably died in infancy), John James Irvine’s only son with his second wife.

John Dods Pringle attended Charterhouse School from c.1884 to 1889, but did not pass Responsions until October 1890, having, unusually, matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen College, Oxford, a year earlier – on 14 October 1889. He then read for a degree in Law, but was an average student. As far as is known he was in good health at the end of Michaelmas Term 1891 but died at The Cedars, Castle Road, Bedford, England on 20 February 1892. A memorial service was held for him in Magdalen College Chapel.

Robert Sumner Medlicott (detail from a group photo of the Magdalen VIII, 1892)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Robert Sumner Medlicott was a scion of a Norman family whose origins can be traced back to Shropshire in the twelfth century. He studied Classics at Magdalen from 1888 to 1890, when he was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations, then changed to History in which he was awarded a “Gentleman’s 4th” in 1892, and was popular enough to be elected President of the JCR in his final year, when he also rowed in the College VIII that went Head of the River in the Trinity Term. He was an almost exact contemporary of John Dods Pringle Irvine and this is probably how he met John Dods’s half-sister Amy Douglas Irvine, whom he married in 1905. He took his BA in 1892, after which he studied Theology at Wells Theological College for a year; he was ordained deacon in 1893 and priest in 1894, and he took his MA in 1895. From 1893 to 1896 he was the Curate of St Werburgh’s, Derby, and from 1896 to 1903 he was a Curate in Leeds. From 1903 to 1915 he was the Vicar of Portsmouth and from 1910 to 1915 a Rural Dean in that diocese, all of which suggests that he, like the younger A.A. Steward, was a protégé of the controversial but liberal Anglo-Catholic priest Cosmo Gordon Lang (1864–1945; Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity 1893–96; Suffragan Bishop of Stepney 1901–08; Archbishop of York 1908–28; and Archbishop of Canterbury 1928–42). From 1915 to 1928 Medlicott was Rector of Burghclere with Newtown, near Newbury, Berkshire, a very well endowed living in the gift of the Earl of Carnarvon with a gross stipend of £1,321 p.a. and 989 parishioners. During World War One he served as a Chaplain (4th Class) to the Forces: he went to France in 1918 and served with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). In 1928 he was made Rural Dean of Whitchurch and an Honorary Canon of Winchester; and in 1929 he became Proctor in Convocation of the Diocese of Winchester.

The first two children of Robert Summer and Ellen Douglas were twins (Ellen Douglas and Robert Irvine) who died in infancy (1908); their third child was Joan Douglas (1910–95); their fourth was Mary Medlicott (1912–c.1915); their fifth was Anne Irvine (1914–61); and their sixth was John Irvine (later Lieutenant-Colonel) (1914–70).

Education

Irvine attended a preparatory school at Gorse Cliff, Boscombe, Bournemouth, Hampshire (closed 1943) from c.1893 to 1898 and then became a day-boy at St Andrew’s College, Grahamstown, South Africa, from 1898 to 1901. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 18 October 1904, having passed Responsions in September 1904. He took his First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1905 but then left without a degree to join the Army.

Harold Irvine in the uniform of the 1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards (c.1905/06)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Military and war service

After leaving Oxford, Irvine was put on the Unattached List of Officers, but on 20 December 1905 he obtained a probationary commission in the 1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards (London Gazette, no. 27,865, 19 December 1905, p. 9,085). About 18 months later he resigned his Commission (LG, no. 28,047, 2 August 1907, p. 5,297) and returned to South Africa, but seems, as a Reserve Officer, to have come back to England on the outbreak of World War One. On 9 September 1914 he obtained a Commission in the 1st Regiment of Reserve Cavalry that had been formed in early August 1914 and on 6 November 1914 he was transferred to No. 6 Platoon in the 13th (Reserve) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment (LG, no. 29,096, 9 March 1915, p. 2,484). At some point during the next three months he was transferred to the 4th (Regular) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, which had been stationed at Meiktila, Burma (now Myanmar), when war broke out, landed at Avonmouth on 1 February 1915, and was then sent to Banbury, Oxfordshire, where it became part of 88th Brigade in the 29th Division.

On 21 March 1915 the Battalion sailed for the Mediterranean, where it was supposed to land on ‘V’ Beach on the south-eastern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula at c.09.30 hours on 25 April. One platoon of ‘W’ Company landed as planned, but when it was realized that the enemy fire defilading ‘V’ Beach was preventing the troops who had landed there from moving any further inland, the rest of the Battalion were directed to land at the northern end of ‘W’ Beach, i.e. just round the corner to the west and just below the cliffs of Cape Burnu (Tekke Burnu). So the rest of the Battalion landed here at c.10.00 hours without suffering any casualties. ‘W’ Beach would come to be known as Lancashire Landing because, at 05.30 hours on the same day, the 1st Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers had landed there and taken it despite losing 55 per cent of its officers and men killed, wounded or missing (including A.M.F.W. Porter).

Once the majority of Irvine’s Battalion had got ashore on ‘W’ Beach, they were immediately sent to support the remnants of the Fusilier Battalion who were fighting their way off the beach towards Hill 138, about 500 yards inland, where the Turks had constructed a well-wired and well-defended redoubt. So with ‘Z’ and ‘Y’ Companies in the first line and ‘X’ Company and the remainder of ‘W’ Company in support, the 4th Battalion pressed forward, and although they were held up for two hours by the wire and the defensive fire from rifles and machine-guns, by 14.30 hours they had reached the south-east slope of the Hill. Led by Captain Archibald Douglas Hussey Ray (1878–1915; killed in action 30 April 1915) and using nothing more than hand-held wire-cutters, volunteers cut paths through the wire entanglements and by 15.00 hours the crucial Hill had been overrun. This permitted the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Essex Regiment to establish its headquarters there; ‘Z’ Company of the 4th Battalion to push through towards the Turkish trenches on the Hill’s north-eastern slope; and the remainder of the Worcestershire Regiment to turn south-eastwards and take the fortified hill known as Guezji Baba, about 400 yards further on. Guezji Baba was a crucial vantage point, since its Turkish defenders had a good view across embattled ‘V’ Beach, and had also been able to defilade the 4th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment during the assault on Hill 138. So at c.17.00 hours the shocked and exhausted men of the 4th Battalion were ordered to take the pressure off the troops who were pinned down on ‘V’ Beach by occupying the top of the cliff that overlooked it. Although they were unable to do this, some men managed to get down the cliffs and onto ‘V’ Beach by 08.00 hours on the following morning.

During the night of 25/26 April, the Turks made repeated counter-attacks on Hill 138, none of which were successful, and at last, at 14.30 hours on 26 April, the Battalion was ordered to link up with the French and the survivors of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers and take Hill 141, further over to the east, in order to break the stalemate on ‘V’ Beach. Although the attack was successful this time, the events of 25/26 April had caused a lot of casualties, especially among the officers, and made a certain amount of reorganization necessary. We do not know, however, whether Irvine had taken part in the actions outlined above or been bogged down on ‘V’ Beach with the platoon from ‘W’ Company, or belonged to the few men from his Battalion who had made their way down onto ‘V’ Beach (see below). But it seems probable that, as part of the necessary reorganization, he was reassigned to the 1st Battalion of the Munster Fusiliers, the unit with which he was serving at the time of his death. So in order to understand the probable circumstances of his transfer, we need to understand the tragic story of the 1st Battalion of that Regiment up to and including 29 April 1915.

The ill-fated Battalion had landed back in Britain from India on 10 January, where it found itself, still in its tropical kit, shivering on a quay after disembarkation. Then, on 16 March 1915, with a strength of 28 officers and 1,002 other ranks (ORs), it embarked at Avonmouth for the Dardanelles on the RMS Alaunia (1913; sunk by a newly laid German mine on 19 October 1916 off the Royal Sovereign Lightship, near Hastings, East Sussex, with the loss of two lives; cf. J.H. Harford; E.G.R. Romanes). The transport called in at Malta (24 March), and finally arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 28 March. The men then acclimatized and trained at Mex Camp, five miles outside the city, from 29 March to 8 April, when they embarked on the HT Caledonia (1904; torpedoed with the loss of one life on 4 December 1916 by UB65, when it was c.125 miles east of Malta en route from Salonika to Malta) for the Greek island of Lemnos, half-way between the Peloponnese and Gallipoli.

29th Division Camp at Mex, near Alexandria

HT Caledonia (1904–16)

When the Battalion arrived at Lemnos on 9 April 1915, its strength was down to 27 officers and 932 ORs, probably because of sickness, and it stayed there until 23 April, practising getting into boats in full marching order by means of a pilot’s rope ladder, transferring from ships to boats, and landing from boats. The HT Caledonia left the island at 17.30 hours on 23 April, to cheers from the crews of other ships and the sound of their bands playing, and by 08.00 hours on 24 April it and the rest of the Allied invasion force had assembled near the island of Tenedos, a few miles from the shore of Asiatic Turkey (known as ‘Rabbit Island’, and now the Turkish island of Bozcada). An anonymous Company Commander of the 1st Battalion, the Royal Munster Fusiliers – now identified as Captain (later Colonel, DSO) Guy Westland Geddes (1880–1955) of ‘X’ Comany – later wrote, however, that what struck him most forcibly “was the demeanour of our men, from whom, not a sound, and this from the light hearted devil[-]may[-]care men from the South of Ireland. Even they were filled with a sense of something impending which was quite beyond their ken.” At 04.30 hours on 25 April, the troops transhipped via a former channel steamer and embarked on the SS River Clyde (1905; broken up 1966), a large collier which, at the suggestion of its temporary Captain, Commander (later Commodore) Edward Unwin RN (later VC) (1864–1950), had been turned into a “Trojan Horse”, i.e. an early version of a landing assault ship. It had two wide ports specially cut on either side of the hull, beneath which a wide gallery ran down to the bow, and from which it was possible for a fully laden soldier to access two gangways to the beach across a bridge that was formed by a steam-powered hopper-barge pulling three lighters. The collier, carrying about a quarter of the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, and a half of the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment, in its after part, plus the entire 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers in its forward main deck hold and forward lower hold, crossed in perfect weather to the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula in order to land at ‘V’ Beach, just east of ‘W’ Beach but separated from it by a cliff (see Porter), and just above the village of Sedd-el-Bahr on the right.

Artist’s impression of the beached River Clyde (1905; broken up 1966) on ‘V’ Beach, Gallipoli, on 25 April 1915.

Captain Geddes later wrote that although

we all knew our job and what was expected of us […] “we felt we should have liked to have viewed in reality the scene of our landing beforehand. The maps issued were indifferent, and painted but a poor picture of the topographical features [–] as we found out later.

‘V’ beach is now a peaceful stretch of fine sand that extends for several hundred yards, and it has been described as “a natural amphitheatre” which sloped gently upwards to a height of one hundred feet and was overlooked on both sides by two destroyed forts, which, however, still provided excellent cover for machine-gun nests, of which the Turks had four to six covering the beach. ‘V’ Beach was also protected by two 15-foot thick barbed wire entanglements which the Navy’s heavy guns had not succeeded in destroying, as they consisted of solid metal stakes riveted to plates that were sunk in the ground. Consequently, the beach formed an ideal killing-ground for men who were trapped in vulnerable wooden landing-craft, like the remaining three-quarters – c.700 men – of the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who had transferred before dawn from transports to small boats called cutters (see Porter), and were now being rowed to the beach. The cutters came up on the port side of the River Clyde, hit the beach at about 06.22 hours, at almost exactly the same time as the River Clyde, packed with c.2,000 troops, was deliberately grounded near a stony pier under the cliffs on the right of ‘V’ Beach under Sedd-el-Bahr. But the lateral current there was much faster than anticipated, the collier was just too far from the shore for its two gangways to reach the shallows, let alone the shore itself, and the steam pinnace (or steamer hopper), which can be seen to the right of the River Clyde in the painting above, had swung in the strong current when it was released and was now grounded broadside on the beach, also too far away to act as a bridge. Consequently, the heavily laden troops on the River Clyde, with the 1st Battalion of the Munster Regiment in the lead, had to struggle with difficulty through deep water, and because the Turks held their fire until the very last moment, these men, like the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the cutters, were exposed to a murderous hail of Turkish small-arms fire and much heavier fire from two 37mm Turkish pom-pom cannons, probably taken off a ship, that were capable of doing a great deal of damage very easily. So outside the collier, about 50 per cent of the first wave of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers were casualties within minutes, “literally slaughtered like rats in a trap” wrote Captain Geddes, whilst aboard the collier, Captain Unwin RN clambered waist-deep into the strong current where, at great personal risk, he and some of his sailors began to improvise a bridge of lighters that would enable their passengers to get ashore more easily.

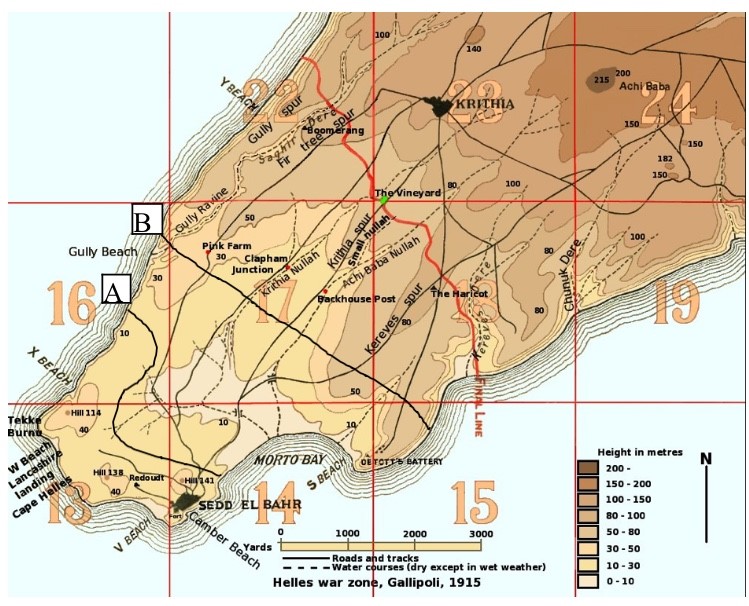

Cape Helles Landings 25 April 1915: A – front line 26 April B – front line 27 April (From Wikipedia ‘Landing at Cape Helles’)

‘Z’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ Companies of the 1st Battalion, the Munster Fusiliers, then tried to do just that, with the men “cheering wildly”. The first Company (‘Z’) was shot to pieces by defilading fire from three directions and only a few of its men reached the far side of the beach, where there was shelter under an escarpment about 4 foot high. While the second Company (‘X’) was following suit, the extemporized bridge of lighters gave way in the current so that many men who escaped the hail of bullets were drowned by their heavy equipment (a full pack, 250 rounds of ammunition, and three days’ rations). And when half of the third (‘Y’) Company tried to rush ashore at about 11.00 hours, it suffered the heaviest losses, this time from severe shrapnel as well as small arms fire and the two 37mm pom-poms. Captain Geddes later remarked: “I think no finer episode could be found of the men’s bravery and discipline than this – of leaving the safety of the River Clyde to go to what was practically certain death.” So by 11.00 hours, getting on for a thousand men had left the River Clyde and nearly half of them had been killed or wounded before reaching the far side of the beach, which Roger Ford in Eden to Armageddon described as having been turned into a “charnel house”. As a result, about another thousand men, including ‘W’ Company of the Munsters, were still stranded aboard the collier where, fortunately, they were protected by the ship’s metal hull and the four machine-guns that had been mounted on its foredeck and surrounded with sandbags. Landings on ‘V’ beach were then halted for the day, but not before a second wave of men, this time from the 1st Battalion, the Essex Regiment, the other half of the 2nd Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment, and members of the one platoon from ‘W’ Company of the 4th Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment (see above), had tried to effect a landing – with similar results. And when, in the late afternoon/early evening, more men from the 4th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment and survivors from the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment on ‘W’ Beach (see Porter) tried to negotiate the intervening cliffs and thence down to ‘V’ Beach, they, too, were forced to give up because of dense wire, snipers, superior fire power, and their own exhaustion.

So at 20.30 hours on the night of 25/26 April, when it was quite dark, the survivors disembarked from the River Clyde without losing a single man. They joined the cold, wet, shocked, and hungry survivors of the previous day, and at 07.00 hours on 26 April 1915, the remnants of the 1st Battalion, the Royal Munster Fusiliers, and the 1st Battalion, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, were ordered to capture the old fort on the cliffs near Sedd-el-Bahr – which they did, remarkably, by 08.00 hours. They then, as ordered, linked up with units from ‘W’ Beach (see above) who had, by this time, captured Hill 138, got through the dense wire on the cliff-tops, and were preparing to assault Hill 141. During the morning of 26 April, the advance was slow and inconclusive, but at 14.00 hours the Royal Navy began bombarding the remaining Turkish positions in Sedd-el-Bahr and on Hill 141, on the eastern side of the village; a spirited bayonet charge on the Hill followed at c.14.30 hours; and by 16.00 hours both village and Hill had been captured and the Turks were starting to withdraw en masse two to three miles inland towards the villages of Krithia and Achi Baba. The Munster Fusiliers may have won its first VC – Corporal (later Staff-Sergeant) William Cosgreve (1888–1936), a giant of a man who had distinguished himself on 25 April by tearing up barbed-wire posts during the landings with his bare hands – but it had lost about 70 per cent of its men killed, wounded or missing, including many experienced veterans and officers. So given the absence of reserves to fill up “the yawning gaps” in the ranks of the 29th Division and of any machinery for making good such wastage, it was probably at about this juncture that Irvine, a relatively experienced officer in a Battalion that had taken relatively few casualties, was transferred out of the 4th Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, and into the depleted 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers even though, it must be stressed, neither War Diary ever mentions his name.

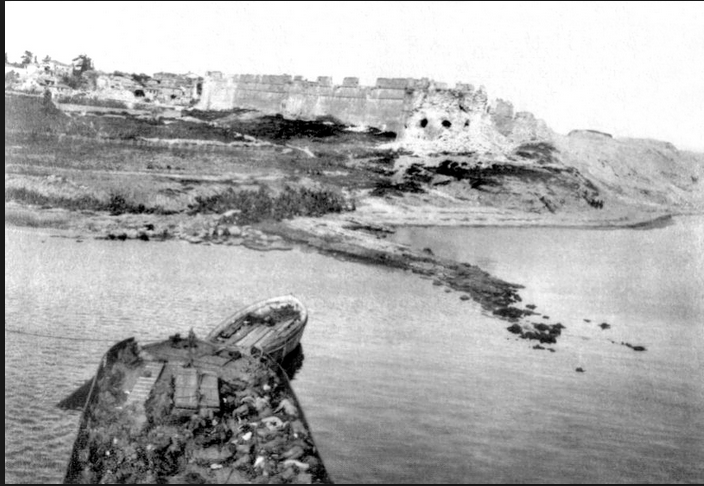

The foredeck of the River Clyde on the morning of 26 April, still covered with casualties of the 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers. On the cliffs one can see the old fort of Sedd-el-Bahr.

‘V’ Beach at Gallipoli seen from the cliffs in the centre of the beach. The connecting beach between ‘V’ and ‘W’ Beaches can be seen in the centre right of the photo. Sedd-el-Bahr and its fort must be behind and to the left of the photographer.

‘V’ Beach about two weeks after the landing of 25 April, seen from the bow of the River Clyde.

By the evening of 27 April 1915, the Allies had secured a new front line that extended about two miles inland and for three miles from the west coast of the Peninsula near the mouth of Gully Ravine (‘Y’ Beach), to Eski Hissarlik (‘S’ Beach) on the east coast of the Peninsula, thus sealing off the landing beaches from the main part of the Peninsula. The 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers took up position in the front-line trenches on 28 April, held them all through that day, and then, at 11.00 hours on 29 April, advanced 1,000 yards together with the 1st Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. But at 21.00 hours the Turks counter-attacked and drove the British right flank backwards. On 1 May the Turks launched an even stronger counter-attack whose Schwerpunkt was the junction between the British and French contingents, but were again repulsed, and on 2 May the entire British line was ordered to advance, but lost heavily and was forced to retire. More attacks and counter-attacks followed over the next few days, but from 6 to 8 May the Allies made a massive attempt to take the hill on which Achi Baba (Alçi Tepe) stood and the high ground which stretched across the Gallipoli Peninsula on both sides of that strategic hill-top village. Irvine’s new Battalion was in Reserve for the first three days of the fighting, but on 9 May, four officers and 400 of its men were ordered to attack, and having reached their goal, they were shelled heavily by the Turks and forced to withdraw. On 11 May, the entire 29th Division was taken out of the front line and replaced by the 42nd Division, and from then until 4 June 1915, the 1st Battalion of the Royal Munsters took no part in any of the intermittent fighting on a minor scale that took place during this period, but rested, trained and did fatigues on various beaches around Cape Helles. On 16 May, a draft of one officer and 53 ORs arrived from the Regiment’s home battalions, and on 2 June 1915 another four officers and 127 ORs arrived as reinforcements. From 4 to 11 June, i.e. just before the British force on Cape Helles was strengthened on 15 June by the arrival on ‘W’ Beach of the 52nd (Lowland) Division (see E.T. Young), the 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers was in Reserve in the trenches near Pink Farm. On 11 June it returned to Gully Beach and from 12 to 23 June it spent ten quiet days in and out of trenches at the head of Gully Ravine (Zighin Dere) that overlooked Gully Beach.

But during the night of 27/28 June, the Munsters moved into the firing line at Bruce’s Ravine, a gully just north of Gurkha Bluff, in order to take part in an assault devised by Lieutenant-General Aylmer Gould Hunter-Weston (1864–1940), the General Officer Commanding VIII Corps who had acquired a reputation for incompetence and indifference towards the fate of his men because of his poor performance during the first months of the Gallipoli campaign. By the time that the Third Battle of Krithia ended on 6 June 1915, the Allies had made a certain amount of progress up the centre of the Gallipoli Peninsula, but much less progress up the flanks, i.e. along the east and west coasts. On the east coast they were hindered particularly by the Kerevez Dere, a deep ravine that was well protected by solid lines of barbed wire and machine-guns. This began on the coast just north of De Tott’s Battery, and curved upwards and inland to Achi Baba. So at 04.30 hours on 21 June 1915, after pounding the ravine for several days with their excellent artillery pieces and trench mortars, of which they had many more than their immediate British comrades, the French 1st and 2nd Divisions made the first of three costly assaults on the Dere, and by 18.00 hours 600 yards of Turkish trenches on the extreme right of the heights that flank Kerevez Dere were in Allied hands despite prompt and resolute Turkish counter-attacks. The French Corps Expéditionnaire lost c.2,500 officers and men killed, wounded or missing, while it is estimated that the Turkish losses were c.7,000 men killed, wounded or missing. Encouraged by this success, Hunter-Weston planned a similar assault on the west coast of the Peninsula. The aim was to drive the Turks 1,000 yards northwards along Gully Spur (branching out to the left of Gully Ravine), Fir Tree Spur (branching out to the right of Gully Ravine and so nearer the centre of the Peninsula), and Gully Ravine itself (between the two Spurs and above ‘Y’ Beach).

So at 11.30 hours on 28 June 1915, the 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers attacked towards Bruce’s Ravine and at first enjoyed some success. But at 14.00 hours the Turks counter-attacked with their usual verve and determination, and according to several eye-witnesses, Irvine was very badly wounded by shrapnel, either in the neck or the abdomen, at or near Gurkha Bluff, when he was getting out of the British trench in order to lead the Company to which he was attached in a charge against another trench, half of which was being held by a Company of the Royal Fusiliers and half by the Turks. After being hit, Irvine was brought into the cover of a trench that was held by the British throughout the night of 28/29 June and where he was heard to say “I think this has done for me.” But as it was so far forward, he could not be carried out, especially as the Turks continued to counter-attack very heavily throughout the night, and men coming along the trench were ordered not to step on him. He died, aged 29, at about 05.00 hours on 29 June 1915 in No. 89 Field Hospital, and has no known grave. Had he remained with the 4th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment he would probably not have fared any better, since by 12 May, it had only 11 officers left; on 4 June it lost ten officers killed, wounded or missing; and it suffered a steady trickle of officer casualties between major engagements.

According to a brother officer, Irvine did his work well and

was very popular with the men. He did some excellent work with the Munsters, not only in the attack but all through in the trenches, especially in preparing sketches and plans of our very complicated trenches. His plans were used by the Brigade. He was liked by everyone.

Irvine is commemorated on the War Memorial at St Andrew’s College, Grahamstown, South Africa, on his father’s grave in South Africa, and on Panels 104 to 113, Helles Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. He had inherited a lot of property in South Africa, but as the War Office refused to issue formal death certificates for men who were missing in action, it took the South African Supreme Court until 3 March 1917 to recognise the validity of Irvine’s will (dated 30 April 1915), in which he left most of his estate to Miss Dorothy Hayward Rogers of Johannesburg. The war gratuity owing to his estate had still not been paid by 7 March 1922.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Huw and Jill Rodge, Helles Landing: Gallipoli (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 2003), pp. 130–66.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Harold Irvine’ [obituary], The Times, no. 40,964 (20 September 1915), p. 11.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, extra number (5 November 1915), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘Harold Irvine’ [obituary], Saint Andrew’s College Magazine (Grahamstown), 37, no. 4 (December 1915), p. 184.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 343.

Rodge (2003), pp. 93–9, 102.

Callwell (2005), pp. 78–85, 147–65.

Ford (2010), pp. 224–9.

Sir Ian Hamilton’s Despatches from the Dardanelles, etc. (Uckfield, East Sussex: The Naval & Military Press, 2010), pp. 12–19.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: UR 2/1/54.

WO95/4310 (Contains a typescript of Captain G.W. Geddes’s report ‘The Landing from the “River Clyde” at V. Beach April 25th 1915’. The report is unsigned and Geddes simply describes himself as “A Company Commander in the 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers”.

WO95/4312.

WO339/6381.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘List of Turkish place names’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Turkish_place_names (accessed 29 July 2018).