Fact file:

Matriculated: 1910

Born: 14 May 1892

Died: 28 June 1915

Regiment: Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

Grave/Memorial: Helles Memorial: Addenda Panel

Family background

b. 14 May 1892 at 11, Great Western Terrace, Kelvinside, Glasgow, as the third (second surviving) son (of four children) of Daniel Henderson Lusk Young, JP, DL, CBE (1862–1921), and Elspeth Alice Young (née Templeton) (1861–1945) (m. 1888). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 3, Victoria Great Road, Partick (three servants); at the time of the 1901 Census it was living at 16, Woodlands Terrace, Glasgow (three servants); it was still living there in 1910 but later moved to Overtoun, Dumbarton.

Parents and antecedents

Young’s father was the eldest of 11 children, six of whom died in infancy. His paternal grandfather was Robert Young (1823–93), a general merchant from the town of Kirkintilloch, Dumbartonshire, to the north of Glasgow, who started his mercantile career as a ship broker, only to lose most of his capital when the City of Glasgow Bank failed in 1877–78 because of bad lending, speculative investments in America and Australasia, false reports about gold holdings, and fraudulent accounting. The bank’s Manager and Directors were tried in the High Court in Edinburgh in January 1879 and sentenced to terms of imprisonment of between eight and 18 months, but by this time, 80 per cent of its shareholders, mainly small investors, were ruined.

Although Young’s mother came from a Dumbartonshire farming community, north-east of Glasgow, her father, John Stewart Templeton (1832–1918) was a carpet manufacturer from Blantyre, whose firm, James Templeton and Co., had been set up in 1838 in Bridgeton, just east of Glasgow’s city centre, by James Templeton (1802–1906), his father and Elspeth Alice’s grandfather. Young’s father joined the firm and rose to become its senior partner, and by the time the firm reached its peak it employed 3,000 people and was the leading British manufacturer of carpets in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It closed in 1979. Most of the members of the large Young and Templeton families worked in heavy industry or one of the learned professions. In December 1910 Young’s father stood as the Conservative candidate for Falkirk Burghs, but lost by c.2,000 votes to the Liberal candidate John Archibald Murray Macdonald (1854–1939). In 1915 a newspaper article named him as the Conservative and Unionist candidate for Dumbartonshire and in November 1917 he was appointed Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Dumbartonshire.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Arthur Stewart Leslie (later Sir, 1st Baronet, JP, MP; b. 1889, d. 1950 in France); married (1913) Dorothy Spencer (1889–1966); two sons, two daughters;

(2) Arthur D.L. (b. 1890, d. in infancy);

(3) Nancy Templeton (b. 1896); later Whitcombe after her marriage in 1917 to Lieutenant Eric Aubrey Hawkes Whitcombe, Royal Field Artillery (b. 1886 in New Zealand, d. 1967); two sons, two daughters.

Arthur Stewart Leslie attended Glasgow Academy from 1900 to 1902 and Fettes College from 1902 to 1908 “without achieving eminence”. But his subsequent career was one of considerable distinction, for he acquired a triple reputation – as a businessman, politician and yachtsman. He became Chairman of the family firm, James Templeton & Co. Ltd (see above), and was, for a time, a Director of the Clydesdale Bank. He took a close interest in the social and benevolent work of the Trades House in Glasgow; he was a Director of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, and Provost of Cove and Kilcreggan. During World War One he, like his brother, served in the 1/8th Battalion of the Cameronians and attained the rank of Major. In 1934 he became Treasurer of the Western Division Council of the Scottish Unionist Association. He first entered Parliament in 1935 as the Unionist Member for the Partick Division, and his worth as an organizer and arbitrator who knew how to work behind the parliamentary scene was quickly recognized. In 1937 he became Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to the Under-Secretary of State for Scotland and in 1939 PPS to the Secretary of State for Scotland; in 1941 he was appointed Scottish Unionist whip and an assistant government whip. From 1942 to 1944 he was a Lord Commissioner of the Treasury and from 1944 to 1945 Vice-Chamberlain of His Majesty’s Household, in which capacity he was required to write a daily account of Parliament for the King’s perusal. A baronetcy was conferred upon him in the resignation honours list of August 1945, and when the constituencies were reorganized in the same year he held the New Scotstoun Division by a majority of 239 until February 1950. As a yachtsman, his greatest victory came in 1931, when his eight-metre Saskia retained the Seawanhaka Cup for Britain against a strong American challenge. He was a Flag Officer of several Yacht Clubs, senior Vice-President of the Yacht Racing Association, and a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron. His elder son, Alistair Spencer Templeton Young (1918–63), followed him as a Director of the family firm. His wife, Dorothy, was the daughter of the distinguished Anglo-Australian biologist and anthropologist Professor Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer, KCMG (1860–1929).

Eric Aubrey Hawkes Whitcombe became the London manager of the family publishing firm of Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch, at one time New Zealand’s largest and most iconic booksellers, printers and publishing company. He and Nancy lived at Wallingford, in Berkshire.

John Douglas Hawkes Whitcombe (1917–2008) was Eric Aubrey and Nancy Templeton Whitcombe’s older son (of four children), and so a nephew of Eric Templeton Young. He married (1943) Heather M. Sherston (1922–2012), and they had one daughter and four sons. After spending five years at Winchester College, where he excelled at games, he went to the Royal Military Academy (Sandhurst) before being commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry, which was stationed at Fort George, near Inverness. In October 1939 the Battalion went to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force, with John the Commanding Officer of the Carrier Platoon (consisting of nine fast but lightly armoured Bren Gun Carriers). In May 1940 the Platoon, minus its Carriers, got out through Calais (mentioned in dispatches). From 1944 to 1954, John worked as a soldier in Italy, Greece and Malaya, and from 1954 to 1956 he was back at Fort George as the Commanding Officer of the Highland Brigade Training. From 1956 to 1959 he was in Cyprus with the 1st Battalion, dealing with the EOKA terrorists (mentioned in dispatches). From 1959 to 1969 he did various administrative jobs before retiring to Yorkshire.

Another nephew was Hugh Templeton Hawkes Whitcombe (1919–46), Eric Aubrey and Nancy Templeton Whitcombe’s younger son. After an above average academic career at Winchester College from 1932 to 1937, where he showed an aptitude for German, played Second XI cricket, and reached Sixth Book in three years, he matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner in October 1937, read Modern History for six terms, and took his BA in 1942. He was given a Territorial Commission in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps on 30 June 1939, transferred to the 145th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (Berkshire Yeomanry), on the outbreak of war in September 1939, and had his Commission confirmed with this unit on 2 October 1939. The Battery did a long stint in Northern Ireland with 183rd Infantry Brigade, during which Whitcombe was promoted Temporary Captain on 7 September 1942, and finally returned to Britain in late January 1943, where it trained for the invasion of Europe for the next 17 months. He fought in north-eastern Europe until mid-November 1944 and then, on 28 January 1945, left England with the Berkshire Yeomanry to take part in the recapture of Malaya from the Japanese. In late November 1945 the Battery went to north-east Java (now Indonesia) to suppress Indonesian nationalists who were seeking independence from Holland, and Whitcombe was killed in an ambush at Domas, near Surabaya, on 11 January 1946, aged 26. He is buried in Jakarta War Cemetery, Grave 5.L.3.

Elizabeth Aubrey Whitcombe (1923-2015) later Dixon, after her 1948 marriage to John Dixon. Elizabeth was in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) during WW2.

Mary T Whitcombe (1927-2017) (later Burgess after her marriage [1950] to (i) John S. Burgess). Mary was a graduate of Oxford University, St Hugh’s College, and later worked for the BBC (Foreign Correspondence).

Education

Young attended Glasgow Academy from 1900 to 1902, Cargilfield Preparatory School, Edinburgh, Scotland’s most famous preparatory school (founded 1873; cf. W.N. Monteith, R.P. Dunn-Pattison), from 1902 to 1906, and the equally prestigious Fettes College, Edinburgh (founded 1870), where he was a pupil from 1906 to 1910 and where he became a School Prefect, a member of the First XV (1909–10), and a Sergeant in the Officers’ Training Corps (founded 1908). The College was “determinedly English in influence, melding an emphasis on rugby, learning and duty with Oxbridge-educated teachers and a purposeful sense of its own mission, ascetic but kindly”.

He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 18 October 1910, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1910. He took the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1911 and then read for an Honours Degree in Modern History. On 31 July 1913 he was awarded a 4th in Modern History and he took his BA on 2 August 1913. While a boy, he played rugby (union) for Cargilfield School, Glasgow Academy and the Glasgow Academicals; while at Oxford he occasionally played for the University, but never against Cambridge; however, he was an international rugby player and capped from 1909 to 1914. In March 1914, he played for Scotland in their last match against England before the outbreak of war. England won by 16 points to 15 in a match which “belongs to the games that will be talked of in the future”. Young was one of the six members of his team to be killed in action. He also played for the London Scottish Football Club and so was one of their 45 team members to die in World War One, a fact that is commemorated in ‘London Scottish (1914)’, by Mick Imlah (1956–2009), another Magdalen alumnus (1976–83; 1st in English 1979). Young lived at Crutherland, East Kilbride, Lanarkshire.

Eight of the eleven officers in this photograph would be killed in action during the attack of 28 June 1915; Young is on the right of the front row. (Archibald Douglas Templeton (1889–1915), seated on the left, was a cousin of Templeton’s mother, and was killed in the same action as Young.)

(Photo courtesy of Mr Simon Wood, The Glasgow Academy)

War service

Young, who was 5 foot 8½ inches tall, was probably in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps throughout his three years at Magdalen and he applied successfully for a Territorial Army commission on 22 November 1910. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 8th Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) (London Gazette, no. 28,483, 7 April 1911, p. 2,808), and promoted Captain with effect from 4 August 1914 (LG, no. 28,860, 4 August 1914, p. 6,077). He trained with the 1/8th Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) at Falkirk, and the Battalion left Falkirk for Devonport on 17 May 1915, arriving there on 18 May as part of 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, in 52nd (Lowland) Division. The Battalion, of whose 30 officers 11 had been at the same school as Young (Glasgow Academy), departed for Gallipoli at midnight on HT Ballarat, and called in at Gibraltar and Malta on 23 and 27 May respectively.

SS Ballarat.

(1911; torpedoed and sunk by UB 32 on 25 April 1917 six miles west of Wolf Rock, a single hazardous rock eight miles south of Land’s End, but with no loss of life).

The Battalion arrived at the port of Mudros, on the Greek island of Lemnos, half-way between the Peloponnese and the Gallipoli Peninsula, on 29 May, and stayed there until 13 June, when it sailed for Cape Helles. On 14 June 1915 it landed at ‘W’ Beach (see A.M.F.W. Porter) and spent the night at a rest camp on ‘X’ Beach, just to the north. On 15 June the Battalion was heavily shelled by long-distance guns from the Turkish mainland and its officers went up to reconnoitre the firing line.

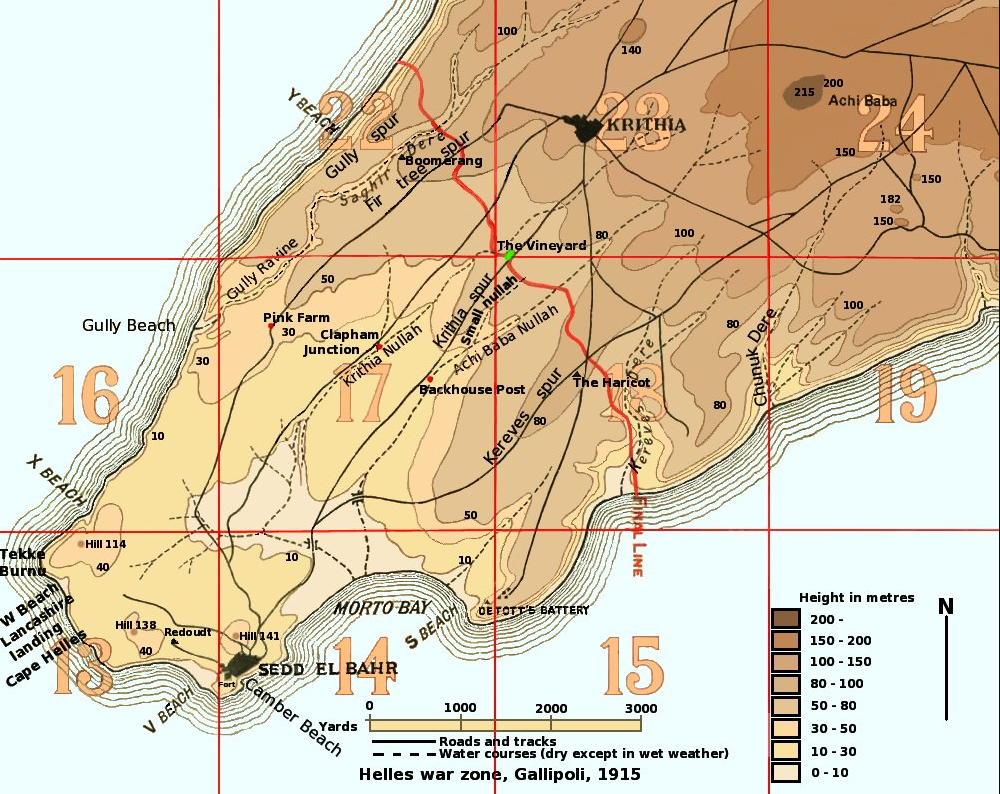

On 19 June the Battalion went into the firing line and just two days later its Commanding Officer, Henry Hannan, TD (1874–1915), was killed by a sniper while observing the French two-division attack on the Kerevez Dere (see below). The situation was quiet until 28 June, when the Battalion moved into the firing line in the small hours of the morning in order to take part in an assault devised by Lieutenant-General Aylmer Gould Hunter-Weston (1864–1940). Since 24 May 1915 he had been the General Officer Commanding VIII Corps and he acquired a reputation for incompetence and indifference towards the fate of his men because of his poor performance during the first months of the Gallipoli campaign. By the time the Third Battle of Krithia ended on 6 June 1915, the Allies had made a certain amount of progress up the centre of the Gallipoli Peninsula, but much less progress up the flanks, i.e. along the east and west coasts (see I.B. Balfour). On the east coast they were hindered particularly by the Kerevez Dere, a deep ravine that curved upwards and inland to the key mountain village of Achi Baba (Alçi Tepe).

Panoramic view of Kerevez Dere with the Asian shore of the Dardanelles faintly visible in the background (1915).

So at 04.30 hours on 21 June 1915, after pounding the ravine for several days with their excellent artillery pieces and trench mortars, of which they had many more than their immediate British comrades, the French 1st and 2nd Divisions made the first of three costly assaults on the Dere, and by 18.00 hours 600 yards of Turkish trenches on the extreme right on the heights that flank Kerevez Dere were in Allied hands, despite prompt and heavy Turkish counter-attacks. The French Corps Expéditionnaire lost c.2,500 officers and men killed, wounded or missing, while it is estimated that the Turkish losses were c.7,000 men killed, wounded or missing. Encouraged by the minor French success, Hunter-Weston planned a similar assault on the west coast of the Peninsula. The aim was to drive the Turks a thousand yards northwards along Gully Spur (a 50-foot high ridge running south-west to north-east to the left of Gully Ravine (Ziğin Dere), parallel to and just next to the coast), Fir Tree Spur (a 50-foot high ridge running south-west to north-east to the right of Gully Ravine up to the outskirts of Krithia, parallel to and about 300 yards from the coast), and Gully Ravine itself (an enormous ravine c.300 yards inland with banks 15 yards high that ran parallel to the west coast for around three miles “among a confusing network of deep tributaries” and led in one direction down onto Gully Beach and in the other up towards Krithia). Hunter-Weston also decided that 156th Brigade, which was on loan to the 29th Division from the 52nd Division and, being a newly formed Territorial Brigade, had not yet seen any action, should attack along Fir Tree Spur, on the right of Gully Ravine.

During the night of 27 June 1915, the Brigade moved in silence up to the front line and was in position by 06.30 hours on 28 June 1915, albeit tired, hungry and thirsty as a result of their slow progress in the heat on the previous day and without adequate information about the Turkish positions (see also Balfour). From 09.00 hours to 10.20 hours, heavy naval guns pounded the first three lines of Turkish trenches with high explosive and shrapnel; the Royal Field Artillery then fired on the Turkish wire for 20 minutes; and the heavy naval guns then fired for the second time until 11.00 hours, when the men of the 156th Brigade went over the top across land that was nearly flat, particularly in front of the 8th Battalion of the Cameronians. The Turks responded with a counter-bombardment on the British front line that was supported by small arms fire, which lasted until 11.00 hours and caused a significant number of casualties to 156th Brigade. Then, when the Turkish firing stopped, no. 1 and no. 3 Companies of Young’s Battalion, with no. 4 Company in support, obediently went over the top, totally unsupported by artillery. But the Turkish trenches were largely undamaged as the preceding barrage had consisted of shrapnel, not high-explosive shells, and much of it had fallen in front of the trenches to the left of Young’s Battalion.

Within five minutes, the losses to Young’s 1/8th Battalion were catastrophic: machine-gun fire from the front and one of the flanks, where a nest of six machine-guns had been cleverly situated, mowed down the first three Companies almost as soon as they left their trenches, and when no. 2 Company followed no. 4 Company over the parapet of the support trench, it suffered heavy casualties even before it had reached the shelter of the British front line trench. Within five minutes, Young’s Battalion had lost 25 out of 26 officers killed, wounded or missing, including the Commanding Officer and Adjutant, and 448 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, of whom over 300 had been killed in action. A few men reached the Turkish trench and were promptly enfiladed by machine-guns on the right front; and by 11.15 hours, as men began to dribble back, the attack by the 1/8th Battalion of the Cameronians was seen to have been a ghastly failure, with no objectives gained. The General Officer Commanding (GOC) 156th Brigade, Brigadier William Scott-Moncrieff (1858–1915), was ordered to compensate for the failure of the 1/8th Battalion by sending in his reserve Battalion, the 1/7th Battalion of the Cameronians, on the orders of his divisional commander Major-General Sir Henry de Beauvoir De Lisle (1864–1955). Two Companies, led by Scott-Moncrieff, attacked at 12.30 hours with exactly the same result: the attack failed and Scott-Moncrieff was killed. Incessant counter-attacks by the Turks caused the fighting to go on until 5 August and cost the British more than 5,000 casualties for the gain of a few hundred yards of Gully Ravine, but the Turks later admitted to having lost 16,000 men killed, wounded or missing. Their request for a short truce to enable them to bury their dead was refused, much to their great anger.

The Action at Gully Spur cost the British 1,750 casualties killed, wounded or missing, a “small” number according to Sir Ian Hamilton’s dispatch of 26 August 1915, but the British gained a small amount of extra space. But of the 1,750 casualties, c.1,400, of whom 800 were deaths in action, were from Young’s 156th Brigade, which had to be reorganized as two composite battalions – one made up of the 4th and 7th Battalions of the Royal Scots, the other of the decimated 7th and 8th Battalions of the Cameronians. A full list of the casualties suffered by Young’s Battalion was originally appended to the Battalion War Diary, but this has now been lost. Lieutenant-General Hunter-Weston would later make himself very unpopular by justifying the casualties in the 156th Brigade as “blooding the pups”, but Major-General Granville Egerton (1859–1951) the GOC 52nd Division who had loaned 156th Brigade to the 29th Division, protested strongly at the way it had been treated and was temporarily dismissed as a result.

Young was killed in action during the attack, aged 23, and has no known grave; his death was not accepted as certain until 10 February 1917. He is commemorated on the Memorials of the three schools that he attended, on the Cameronian Memorial outside the Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow, on the Memorial in St Columba’s Church, Albert Street, Oxford (originally the Presbyterian Chaplaincy that was founded in 1908: the Church was dedicated in 1915), and on the Memorial of the London Scottish Football Club. A confusion led to his name originally appearing on the entry for the 1/6th (Territorial Force) Battalion of the Cameronians that is contained on Panels 5 and 16 of the Memorial in Le Touret Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France, but the error was rectified on 11 December 2009 and his name has now been added to the Addenda Panel of the Helles Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. He left £355 14s. 11d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Sir Arthur Young, M.P.’ [obituary], The Times, no. 51,771 (16 August 1950), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Arthur Stewart Leslie Young’ [obituary], The Fettesian, vol. 73, no. 1 (December 1950), p. 52.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 172, 325.

Chambers (2003), pp. 31, 73–83, 93–8, 107–08.

‘Hugh Templeton Hawkes Whitcombe’, in Hutchins and Sheppard (2004), pp. 369–72.

Callwell (2005), pp. 158–60.

Mick Imlah, ‘London Scottish (1914)’, The Lost Leader (London: Faber, 2008), p. 76.

J.R.W., ‘Obituaries: Major J.D.H. Whitcombe, HLI RHF’, Journal of the Royal Highland Fusiliers (2009), p. 9.

Ford (2010), pp. 242–4.

Sir Ian Hamilton’s Despatches from the Dardanelles, etc. (Uckfield, East Sussex: The Naval & Military Press, 2010), pp. 76–8.

Andrew Davidson, Fred’s War: A Doctor in the Trenches (London: Short Books, 2013), pp. 22–3.

Gariepy (2014), pp. 208–9, 219–23.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/73.

WO95/4321.

WO374/77607.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘James Templeton & Co.’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Templeton_%26_Co (accessed 22 March 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Gully Ravine’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Gully_Ravine (accessed 22 March 2019).