Fact file:

Matriculated: New College, 1898

Born: 22 December 1874

Died: 8 March 1916

Regiment: Devonshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Basrah Memorial: Panel 11

Family background

b. 22 December 1874 in Edinburgh as the second son (four children) of Alexander Dunn-Pattison (b. 1835 in Oban, d. 1884) and Minnie Katherine Dunn-Pattison (née Phillipson) (1852–1929) (m. 1872). At some point, the family lived in Kilbowie, a residential district of Dalmuir, which is an area of Clydebank on the north bank of the River Clyde between Glasgow and Dumbarton. But by the time of the 1881 Census some three years later, the family was living at Kilbowie House, a lakeside property on the Kerrera Sound, one-and-a-half miles south-east of Oban, Argyllshire. After her husband’s death, Minnie Katherine stayed for a while in Oban, but by 1907 she had moved to “Fordwych”, 41, West Cliff Road, Bournemouth, Hampshire (three servants); she left £2,432 4s. 8d.

Kilbowie House, near Oban

Parents and antecedents

Dunn-Pattison’s father was the son of Frederick Hope Pattison (1789–1877), a Glasgow merchant, and Janet Pattison (1789–1877) (née Park) (m. before 1835); Dunn-Pattison’s mother was the daughter of Richard Phillipson (1805–92), a retired surgeon of the Bengal Army, and Mary Ann Frances Phillipson (1825–1900) (née Appleton) (m. before 1852).

Alexander Dunn-Pattison was an advocate at the Scottish Bar and left c.£100,000, invested in such a way that his wife and four children enjoyed annuities of £1,900 p.a. (worth £90,000 p.a. in 2005).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Frederick Hope (1874–1942); married (c.1902) Ethel Jean Duncan (1878–1944); two daughters;

(2) Janet Park (1876–1939); later Archibald after her marriage in 1916 to Cuthbert Norman Archibald (1882–1947);

(3) Marion Frances Kerrera (the name of an island off the coast of Oban) (1883–1943); later Patten after her marriage in 1907 to Brevet Major Archibald Patten (1865–1941), a retired officer of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders.

Wife and children

Dunn-Pattison married Mary (Richie) Winifred Wilkes (1876–1951) in 1904, and they had two daughters. She was the grand-daughter of William Wilks (c.1811–1869) and Christiana Wilks (c.1805–1864) (née Hartshorn) (m. 1835). William Wilks was a manufacturer of glazed stoneware such as sanitary tubes and traps, but also a stonemason and potter who produced “ornamental chimney-tops, fire-bricks, quarries, trusses, ornamental fountains, flower vases, full-sized statues, lions, dogs, eagles &c. &c.” and who, when his firm near Leeds was at its most prosperous in the 1850s and 1860s, employed between 50 and 65 men. Her parents were the Reverend Alpheus Wilkes (1837–1914) and his first wife Mary (Deryn) Wilkes (1838–84) (née Davies) (m. 1866), who has been described as “imaginative, impetuous and full of enthusiasm” but who died of sudden paralysis and heart failure. For two years his children were looked after by an old family nurse and a governess until, “after much prayer”, he married his second wife, Edith English (1847–1945), in 1886. According to some sources, Mary Winifred studied at Girton College, Cambridge, but this is not so, nor did she study at any other of the women’s colleges there.

The Reverend Alpheus Wilkes was an austere evangelical who had been baptized a Wesleyan and later, when he was 16, “passed through a very deep spiritual experience” which eventually led him to the evangelical wing of the Church of England. He brought up his family in an atmosphere of strict simplicity and discipline in which few pleasures and little variety were permitted. In contrast, his first wife, Mary – known as “y Deryn” (the bird) because of her beauty and talent for singing while accompanying herself on the Welsh harp – was the daughter of Henry Davies (1804–90), a well-known journalist, librarian and bookseller in Cheltenham Spa who was also a passionate devotee of Welsh art and culture and the editor of the Conservative journal Looker-On (1833–90). Alpheus graduated from the University of London in 1865, having read a range of subjects including Zoology, English Language and Literature, Philosophy, Hebrew and Theology and was ordained deacon in 1868 and priest in 1869. From 1868 to 1870 he was Curate of Stowmarket and from 1870 to 1873 Curate-in-charge of Titchwell, near King’s Lynn, Norfolk. From 1873 to 1882 he was Headmaster of the grammar school at Little Walsingham (founded 1639; new buildings opened in 1872; now defunct), and simultaneously (1873–90) the Vicar of Waterton and West Barsham, two miles to the south-west, and the Chaplain of the Walsingham Union. From 1887 to 1890 he was an Inspector of Schools for the Diocese of Norfolk and based in Norwich, and from 1890 to 1894 he was the Rector of Whitton-cum-Thurlston, near Ipswich, Suffolk.

On leaving Whitton, Wilkes retired to Torquay, where he and his family lived at 10, Wellswood Park, Torwood. But he seems to have done so under a cloud, and this may have something to do with a readiness to mix theology and politics. In 1869, during his first term as Prime Minister (1868–74), William Ewart Gladstone (1809–98) succeeded in persuading Parliament to disestablish the (Anglican) Church of Ireland via the Irish Church Act which came into force on 1 January 1871, thus disempowering what was, in effect, a minority denomination. Then, in February 1893, during his fourth term (1892–4), Gladstone introduced his Second Home Rule Bill – which was passed by the House of Commons on 21 April 1893 but thrown out by the House of Lords on 8 September of that year. While this Bill was passing through Parliament, three Anglican ministers who had livings in or near Ipswich and opposed Home Rule organized a prayer service in Ipswich’s St Mary Key [Mary-at-the-Quay] Church, a medieval church that had served the once thriving community around the docks. At this service, which took place on 9 March 1893, they “implored Divine assistance for the loyal minority in Ireland” – i.e. the pro-Union and largely upper-class minority in Ireland who still worshipped with the Church of Ireland and who would become even more disempowered and isolated from mainland Britain if Ireland were to become an independent country with a “Romish majority”. Two of the three – the Reverend George Lovely (b. 1826 in Ireland, d. 1895; Vicar of St Mary Key since 1876) and the Reverend William Joseph Frazer Whelan (b. 1852 in Ireland, d. 1934; Vicar of St Lawrence’s Church, Ipswich), who had held several livings in Ireland – were of Irish extraction and had studied Theology at Trinity College, Dublin.

Alpheus Wilkes was the third, and when it was his turn, he occupied the pulpit of a packed church for half an hour in order to pray and deliver a commentary upon a selected passage of Scripture in what one newspaper described as “a most remarkable address”. He began by reading out Acts, Chapter 12, which relates how St Peter was thrown into prison by King Herod but delivered by angels. He then derived a contemporary political allegory from the biblical text: “Herod was merely a man-pleaser who wanted to stand well in the judgment of his fellow-men and get applause. Having killed ‘James, the brother of John, with the sword’, and seeing that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded to take St. Peter also, but prayer was made without ceasing, and there followed the direct intervention of the Almighty.” He concluded with the thought: “You know how to translate this into modern language […] and suit it to the subject of this crisis”, thereby leaving “the congregation to draw the obvious inference that Mr. Gladstone is another Herod seeking applause and votes, that he has killed the Irish Church [via the 1869 Bill], and that he hopes to kill the loyal minority [via the 1893 Bill].” One can perhaps deduce the effect of such strident political theologizing on Wilkes’s congregation and the diocesan hierarchy from the fact that when he left Whitton in the following year at the relatively young age of 56 and moved to Torquay, this “hairy” man was replaced by an altogether “smoother” man who seems, in retrospect, to have been his antithesis. The Reverend Harold Anson (1867–1954) was a man of delicate health and from a family with strong aristocratic links; his outlook was described as “broad and liberal”; he had read History at Christ Church, Oxford, and subsequently trained for the priesthood at Cuddesdon College – an institution in the Anglo-Catholic tradition which had come into being in the wake of the Oxford Movement (1856) and at that time accepted only Oxbridge graduates; and he was altogether much more of an establishment man than his predecessor, becoming Master of the Temple from 1935 to his death in 1954.

In February 1922, six years after her husband’s death in Mesopotamia, Mary Winifred moved from the Devon village of Braunton, where the couple had lived, to 4, Cottenham Court, Wimbledon, London SW, which was still her address in 1938 despite her work in Switzerland. On 9 February 1922, when she was about to leave Braunton, a brief appreciation of her life in the village over the previous six years appeared in the North Devon Journal. The reporter observed that she had

thrown herself heart and soul into Christian undenominational work. Amongst her many activities she founded the Institute in East Street. Here Bible Classes and services are held regularly, and in addition, the young people of all ages are specially cared for, there being classes for glove making, raffia work, sewing, etc., and many games are provided. The Institute is thus doing a great work in the town, a work that should not be allowed to drop.

On 22 March 1922 Sanders and Son auctioned off a large quantity of her “very superior household furniture and outdoor effects” at “Kilbowie”. In 1923 she and her two daughters went to live at Château D’Oex, nine miles west-south-west of Montreux, in Switzerland; in 1925 they moved to Vennes, north of Lausanne, which was becoming a centre for the training of missionaries, and by spring 1926 Mary Winifred was living at the Chalet Point du Jour there, where she was engaged in founding and leading Evangelical Christian groups in Switzerland. She also travelled to Japan on at least one occasion to gather material about her second brother, Alpheus Nelson Paget Wilkes, whose lengthy biography she published in 1937.

Mary Winifred Dunn-Pattison and her brother Alpheus Nelson Paget Wilkes (c.1932)

(Photo from Ablaze for God, facing p. 299)

Mary Winifred had two brothers and one sister:

(1) Lewis Chitty Vaughan (1869–1947); married (1899) Cicely Ellen Philadelphia Comyn (1875–1967); two sons, three daughters;

(2) Alpheus Nelson Paget (1871–1934); married (1897) Gertrude Barthorp (1857–1938); one son;

(3) Margaret Ethel (1874–1944).

Lewis Chitty Vaughan Wilkes was educated at the Perse School, Cambridge (c.1882–87) and Hertford College, Oxford, where he held an Open Scholarship in Classics from 1888 to 1892 (BA 1892), after which he became a schoolmaster for several years. But in 1899 he and his new wife founded St Cyprian’s School, Eastbourne, a leading and influential preparatory school until it was forced to close in 1941. Although the school’s ethos owed much to “muscular Christianity”, Lewis Wilkes, possibly in reaction to his father’s strict evangelicalism, was an agnostic. He left £71,420 3s. 11d.

Alpheus Nelson Paget Wilkes was educated at Bedford School (1887–c.1891) and Lincoln College, Oxford (1892–96), where he was awarded a 2nd in Classics. But on 10 March 1892 he underwent a conversion after attending a meeting in Ipswich conducted by the Baptist evangelist Frederick Brotherton Meyer (1847–1929), and during his time at Oxford he became a fervently evangelical Christian with contacts in the Pentecostal League and the Salvation Army – which made him unpopular in his College and caused his room to be trashed on several occasions. He also spent much of his vacations working in boys’ camps and for the Children’s Special Service Mission (founded in Islington in 1867 by Joseph Spiers (1842–1909) and Thomas ‘Pious’ Hughes (dates unknown)), and towards the end of his course decided that he had been called to Japan as a missionary. So in September 1897, just two months after his marriage, he and his wife sailed for Japan as Evangelical Christian missionaries, with Matsue, where he learnt Japanese in a year, and Osaka as his major bases. They remained there until February 1902, when they returned to England. In July 1903, at the Keswick Convention (founded 1875 as an annual conference for evangelical Christians), Alpheus Paget became one of the founders of the Japan Evangelistic Band, and for 20 years after his return to Japan in October 1903 he alternated between Britain and Japan. A powerful evangelical preacher, his favourite themes were the Blood of Christ and faith in its redemptive power, and he was particularly known for his “dynamic” preaching, a word that appears in the titles of four of his books. For two years he made Tokyo his base and then, in November 1905, Kobe, Japan’s sixth largest city. From 1908 to April 1910 he spent 18 months in England, returning to Japan via Berlin, Moscow and the Trans-Siberian Railway, and not long after his return he paid his first visit to Korea, where Evangelical Protestantism was having a spectacular success.

During World War One he continued to divide his time between Britain and Japan and narrowly escaped being on the RMS Andania during the voyage when she was torpedoed by UB-46 off the Irish coast on 27 January 1918; in April of the same year his son Arthur Hamilton Paget Wilkes (b. 1898 in Japan, d. 1955) was gassed in Flanders, but survived and was taken prisoner in Germany in October 1918 – after the war he, too, had a distinguished career as a missionary. From early 1921 to August 1923 Alpheus and his wife were back in England, but while she visited Arthur in South Africa, he arrived back in Japan just after the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1 September 1923, which devastated Tokyo and Kobe and killed between 100,000 and 145,000 people. The winter months of 1924/25 were the last of his time in Japan as Field Director of the Band. In July 1925 he arrived at Shanghai when anti-foreign and anti-Christian feeling was growing, and helped to found an all-Chinese missionary association there which became known as the “Bethel World-Wide Evangelistic Band”.

Alpheus and his wife arrived back in England in February 1926 and in spring of that year he visited his younger sister Mary Winifred in her new home in Switzerland. He repeated the visit in the autumn, when the first Convention was held at “Emmaus”, the new Bible School there; and he was there again in autumn 1927 after an extended and taxing tour of South Africa. But his health was beginning to fail and in spring 1928 a constant sense of fatigue compelled him and his wife to take medical advice and break off a return journey to Japan. So he returned to England, but in April 1928 he visited Vennes for the fourth time and combined a long period of rest there with evangelism, work for the Scripture Union, especially amongst children, and the composition of some of his best-known hymns, one of which is called ‘Vennes’. In April 1929 he and his wife left Switzerland and in February 1930 they returned to Japan for the last time, via Shanghai. After their return to England in spring 1931, they revisited Switzerland, doing so again in 1932. On these occasions they attended Conventions at Mont Pélérin, near Vevey. In October 1933, Alpheus’ declining health rendered rest imperative and he and his wife came back to Vennes for seven weeks, until December 1933, when they returned to England. In early spring and summer 1934, though far from well, Alpheus continued to accept invitations from friends to speak at gatherings in their homes and was even able, in April and June 1934, to attend the Bangor Convention in Ireland and the Japan Evangelistic Band’s Convention at Swanwick, Hampshire. He died in a small nursing home in Chandlersford, near Eastleigh, Hampshire, on 5 October 1934 and is buried in Gap Road Cemetery, Wimbledon.

Margaret Ethel became a nurse. In 1901 she was nursing at the Sunderland Infirmary, but she moved back to Torquay to become the Matron of a hospital there and, presumably, to be near her father. Shortly after the Census of April 1911 she became the Matron of the Hospital for Incurables in Newcastle-on-Tyne and by July 1911 she was a member of the Matrons’ Council.

Richard and Mary Winifred Dunn-Pattison’s children were:

(1) Janet Mary (1911–70); later Henderson after her marriage in 1938 to Peter Reynolds Henderson (Royal Horse Artillery, later Brigadier, DSO; 1908–70); one son, one daughter;

(2) Katherine Winifred (1913–2005; later MB, BS, MRCS, LRCP); later Ainger after her marriage in 1938 to Major (retired) Edward Ainger (1894–1989); one daughter.

Peter Reynolds Henderson was the eldest son of Edward Lowry Henderson (1873–1947), Dean of Salisbury from 1936 to 1943; his younger brother Edward Barry Henderson (1910–36) was Bishop of Bath and Wells from 1960 to 1975.

Katherine Winifred studied Medicine at the University of London and became a GP.

Education, professional life, and pre-war military service

Dunn-Pattison attended Cargilfield School, Edinburgh, Scotland’s most famous preparatory school (founded 1873; cf. W.N. Monteith, E.T. Young) from January 1883 to 1889, and was awarded an Open Scholarship to the equally prestigious Fettes College, Edinburgh (founded 1870), where he was a pupil from 1889 to 1893. The College was “determinedly English in influence, melding an emphasis on rugby, learning and duty with Oxbridge-educated teachers and a purposeful sense of its own mission, ascetic but kindly”. Although it had no clergy on its staff and no Officers’ Training Corps until 1908, many of its boys went into the Army and on 28 June 1893, Dunn-Pattison came out top in the Infantry Section of the entrance examination for the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) with a mark of 8,575 (143 marks higher than his runner-up and 2,267 marks higher than Winston Churchill, who passed the examination for the Cavalry Section in fourth place on his fourth attempt on exactly the same day, having applied for the Cavalry because the examination was less demanding). Dunn-Pattison trained at Sandhurst until January 1895 and may have passed out there in first place, since his name appears in the first place of the non-alphabetical list of those cadets who passed out with Honours which appeared in The Times. He was also awarded a prize for general proficiency and military topography.

Dunn-Pattison was promoted Lieutenant on 20 February 1895 and assigned to the 1st Battalion, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (the 91st Foot), but after three years and two months in this unit, he was transferred as a Captain (25 May 1898) to the 1st Volunteer Battalion of the Oxfordshire Light Infantry (Oxford University Rifle Volunteer Corps). But he resigned his Commission “owing to a breakdown in health” and on 15 October 1898 he matriculated as a Commoner at New College, Oxford, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1898. He then took an Additional Subject in Michaelmas Term 1898 and part of the First Public Examination (Holy Scriptures) in Trinity Term 1899, when he also took the Preliminary Examination as part of the Second Public Examination. He then changed to an Honours Degree in Modern History and was awarded a 1st in Modern History in Trinity Term 1901. He took his BA on 10 October 1901 (MA in 1906) and in July 1902 he was appointed Lecturer in Modern History at Magdalen (officially confirmed on 9 December 1902), a post that he held until July 1904, when he gave up the set of rooms in Magdalen where he had been living since October 1903 (Cloisters No. 4, 1 pair right). He then moved to Torquay for the sake of his health, where he met his future wife, Mary Winifred Wilkes, who was living with her father and an aunt, Christiana Wilkes (1839–1923), a former mission worker who had become a Deaconess.

On 29 June 1904 Dunn-Pattison and Mary married at Holy Trinity Church, Torquay, a large, late nineteenth-century church with strong evangelical and nonconformist roots, and in 1905, with his annuity of £1,900 and a lump sum of £3,854 that had come to him when he was 25, Dunn-Pattison and his wife were able to move “for health reasons” and settle down very comfortably in the picturesque North Devon village of Braunton, five miles west-north-west of Barnstaple and two miles from the sea. Here they had bought a large house in Wrafton Road from the son of Francis Thompson (c.1812–1904), a recently deceased military surgeon who had also served in the Bengal Army, and they immediately changed its name from “The Firs” to “Kilbowie”, after the area in Dalmuir where Dunn-Pattison’s parents had lived: it is now called “The Brittons”. By early 1906, Dunn-Pattison was starting to become a “leading citizen” of Braunton, and his name first appeared in print on 5 January 1906 in a brief report on an indeterminate political meeting in Braunton. Over the next eight years, it would appear dozens, possibly even hundreds, of times in a variety of Devon newspapers in connection with a considerable range of clubs, associations, local events like flower shows and sheep-shearing or ploughing competitions, charities and worthy causes.

“Kilbowie” (now “The Brittons”, formerly “The Firs”), Braunton (date unknown)

(Photo courtesy of Braunton Museum, North Devon)

Here are some of them: by August 1906 he had become a member of the upmarket Saunton Golf Club (founded 1897 and situated about two miles west of Braunton), and he was its Honorary Secretary from 1907 to 1911; and in November of that year he had become an honorary member of the Loyal St Brannock’s Lodge of the Manchester Unity Oddfellows, a Friendly Society that was devoted to care and social work in the locality before the advent of the welfare state and whose Hall was in Braunton’s Caen Street, and Vice-Chairman of the Braunton Unionist Party. On 3 January 1907 he was sworn in at Braunton as a County Magistrate, and by 27 June 1907 his name had been mentioned in this capacity 12 times by local newspapers. Most of his work concerned such minor infringements of the law as petty theft, brawling, or riding a bicycle without lights. But on 23 November 1908 he was faced with something more serious when he took part in an enquiry at Barnstaple concerning the wrecking of the Gloucester-based schooner Phyllis Grey (launched 1878), which, while en route from Swansea to St-Malo carrying 183 tons of coal, had been found bottom up on nearby Saunton Sands on the morning of 9 November and all its crew of five drowned or missing. The court found that during the night of 8/9 November, the ship had probably been caught in a fierce west-south-westerly gale on a rough sea and been dismasted before being driven helplessly onto the shore – though some doubt was expressed as to why she had a huge rent in her side.

In March 1907 Dunn-Pattison was elected to a seat on Braunton’s Parish Council and held it until his death; when, in May 1907, he was elected a Governor of Challoner’s Charity School, Braunton (endowed in 1667/68 for boys from poor families by the Reverend William Challoner and housed in its own new building in 1866), the anonymous reporter noted that he had become “very popular”; and in December 1907 he was appointed Chairman of the Parish Council’s Lighting Committee. In July 1908 it was reported that Dunn-Pattison, described by an obituarist as a “devoted churchman”, had given a dinner for the Bible Class of Braunton’s St Brannock’s Church, where he was a sidesman: the dinner became an annual event and a piece that appeared on 30 June 1910 reported that the Class “had greatly flourished under his teaching”, an indication, like the place of his wedding, that his churchmanship tended towards the evangelical. When he was re-elected to a seat on the Parish Council at the triennial elections in March 1910, a report on the hustings that appeared in the North Devon Journal recorded that he had attended 15 out of the Council’s 20 meetings during the previous three years – a slightly below average record of attendance – and that he was the only candidate to oppose Sunday postal deliveries – another indication of his churchmanship even though he approved the idea that the local Post Office should open for an hour on Sunday mornings so that people could collect their mail themselves. He was subsequently – probably around April 1913 – co-opted as the Chairman of the Braunton Parish Council and just before 22 April 1914 he was re-elected as its Chairman. So when war broke out, he did not resign immediately since he, like many others, expected the war to be brief. But the North Devon Journal reported that in March 1915 he had written to the Council from India, proffering his resignation: “As I shall be on the Continent during the next, I hope, few months, I am afraid I shall not be of any use to the Council. Will you please thank them for me for the way in which they put up with my deficiencies as Chairman and for the loyal support they always rendered to me, hoping [that] the War will soon be over.” But his temporary replacement said that

if he understood anything of the feeling of the Council and also of the Parish at large, they could not think of accepting their Chairman’s resignation. The Council honoured those of their members who thought it their duty to respond to the call of King and Country. […] As a Council, he thought they should be gratified there was that spirit on the part of the leading inhabitants in Braunton. He was sure he would be expressing their views and feeling in moving the re-election as Chairman of Mr. Dunn-Pattison, who took such an interest in the welfare of the parish.

The motion was quickly seconded and unanimously carried. On 16 June 1915 Dunn-Pattison replied as follows:

Many thanks for your letter informing me that the Braunton Parish Council had done me the honour of re-electing me Chairman of the Council for the ensuing year. Would you please be so kind as to inform them, individually and collectively, the great pleasure I feel in the honour they have conferred upon me. At present I am afraid there is no sign of a speedy ending of the War. But if the War is over this year I shall be only too glad to do anything I can for Braunton and the Parishioners, who have always shown me the greatest kindness.

According to an obituarist, in his capacity as Chairman he enjoyed “the confidence and esteem not only of the Councillors but of all the rate payers”.

Old Cottages in Braunton’s Saunton Road

(Photo courtesy of Braunton Museum, North Devon)

Old Cottages in Braunton’s Saunton Road

(Photo courtesy of Braunton Museum, North Devon)

Politically a Conservative Unionist, Dunn-Pattison had become the Chairman of the Braunton Conservative Association by autumn 1910, and on 30 October 1910 he presided over a meeting that was held in Braunton Council Schools for the purpose of forming a branch of the Land Union. This organization had been founded in May 1910, while Britain was going through a period of political and constitutional upheaval, and although “professedly non-political”, it sought to oppose the land clauses of Mr Lloyd George’s budget on the grounds that they were inimical to the interests of landowners and others because of their proposal to increase the tax – “increment tax” – on the value that had been added to a piece of land when it was sold. And in the above capacity, on 5 December 1910, i.e. during the run-up to the General Election of 15 December, Dunn-Pattison took part in another meeting in Braunton Council Schools where a lively audience was addressed by Ernest Joseph Soares (later Sir) (1864–1926), the Liberal MP for Barnstaple 1900–11, on major current political issues. During the meeting, which was marked by much laughter and applause from the supporters of both political parties, Dunn-Pattison and Soares crossed swords in a friendly but hard-hitting way over such matters as Home Rule for Ireland, the true nature of Land Tax – about which Soares accused the newly formed Land Union of spreading “mendacities” – and the current strength internationally of the Royal Navy.

On 16 November 1910 Dunn-Pattison became the Vice-President of Braunton’s newly founded Association Football Club, which had been given permission to train on a field belonging to the local Vicar and whose membership was confined to the two Bible Classes belonging to the Parish Church of St Brannock’s. In January 1911 he judged a local ploughing competition for the first time. He was a founding member of the Braunton Bowling Club and sold it the land for its new, four-rink bowling green that opened on 26 June 1911: by 31 January 1914 he had become its Vice-President. In July 1911 he was made President of the Boy Scouts Association for North Devon. On 1 August 1912 he won a prize at the First Annual Show of Braunton’s Garden Society and in late July 1914 he won prizes at the Third Annual Show for his scarlet runners, celery, sweet peas, carnations, dahlias and foliage plants, besides being the member deputed to present a silver salver to his friend Dr Walter Joseph Harper (1869–1952), a local GP who was retiring after practising for many years in the village and who was also very active in its public life. On 7 June 1913 his name appeared in print as a member of the committee that was arranging a sheep-shearing competition.

Braunton Bowling Club (pre-1914); although Dunn-Pattison is almost certainly in this photo and is possibly the second man from the left (seated) in the middle row, we have been unable to identify him with any certainty

(Photo courtesy of Braunton Museum, North Devon)

A practised lecturer, whose style as a historian one reviewer would describe in 1912 as “similar to that of a popular lecturer”, the press often reported on a “well-received” talk that he had given in the locality: on 20 March 1911 he lectured at the Barnstaple Conservative Club on the need for a strong Royal Navy and the probable effects on Britain of major war and on 26 October 1911 he gave a lecture accompanied by “about 40 fine lantern slides” on Australia, a country which, as far as is known, he had never visited. On 3 February 1911 he lectured to the Territorials at Barnstaple’s Drill Hall on ‘The Action of the 1st Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders at Modder River, South Africa, during the late South African Campaign’, a topic with which he would have become familiar while researching his history of the Regiment that was published by Methuen in 1910. And in February 1912 he gave a speech during an evening of music and entertainment at Braunton’s Conservative Club on the Liberal Government’s Insurance Act of 1911 – one of the foundations of modern social welfare in Britain that had received the Royal Assent on 16 December 1911. The report does not describe Dunn-Pattison’s attitude to the Act, but it was probably critical, not to say straightforwardly negative, since the new legislation was opposed by large sections of the Conservative Party who, as is still the case today, believed that taxpayers should not finance other people’s social benefits. By September 1906 he was supporting the North Devon Infirmary (Litchdon Street, Barnstaple, North Devon; founded 1824) with modest sums of money that appeared on lists of donors in the local press and by October 1909 he had become one of the Infirmary’s Governors; from about 1912 to the outbreak of the war he acted as the Infirmary’s Honorary Secretary (Treasurer and Auditor) and came into Barnstaple daily in connection with this work. In this capacity he chaired the meeting on 30 July 1914 when it was decided to hold a carnival in Barnstaple in aid of the Infirmary.

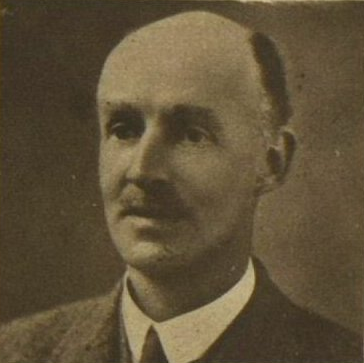

Richard Phillipson Dunn-Pattison, MA

(Photo originally published in The Illustrated London News, no. 4,015, 1 April 1916, p. 19)

From 12 to 31 March 1908 Dunn-Pattison was a Lieutenant in the 1/4th Volunteer Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, the successor of the 6th Devonshire Volunteer Corps (founded at Barnstaple in 1859), and when the “Haldane Reforms” came into force on 1 April 1908 as a result of the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act (Royal Assent August 1907), he was transferred to the Regiment’s 1/6th (Barnstaple) Battalion (Territorial Force). This unit recruited mainly from the Barnstaple area of North Devon and on 30 July 1908 consisted of eight Companies with a total strength of 388 officers and other ranks (21 officers, 13 staff-sergeants, 31 sergeants, 5 lance-sergeants, 18 corporals, 20 lance-corporals, 14 buglers and 266 privates). By mid-March 1909 he was actively recruiting for the new Territorial Force on the grounds that a strong part-time army of well-trained volunteers was preferable to conscription, and he was an active member of the 1/6th Battalion until July 1910 (promoted Captain with effect from 1 June 1910, after which the local press nearly always referred to him by this title). On 28 March 1910 he had participated in a mock battle on Halsinger Down, just north-north-east of Braunton, when the Battalion’s ‘A’ (Barnstaple) Company attacked a position held by the Battalion’s ‘B’ (Braunton) Company. But on 20 July 1910, a month or so after he had suffered a bout of ill-health and when his wife was three months pregnant with their first child, he applied to have his name removed from the active list, and on 17 October 1910 he became a member of the Reserve.

Even so, he did not cease helping to prepare the local community for war and by July 1913 he had become the Commandant of the Braunton Detachment of the British Red Cross Society (founded 1863) when it, together with the Barnstaple Detachment, paraded on Braunton Recreation Grounds. Just under a year later, Dunn-Pattison’s Detachment had become an even more serious organization, for when the two local Detachments paraded on 2 May 1914 for inspection, they did so in Barnstaple’s Albert Hall (opened under this name in 1897; destroyed by fire in 1941; now the Queen’s Theatre), which had been transformed into a military hospital for the occasion, with young volunteers playing the part of the wounded. According to the report, they were observed, tested and questioned critically by a senior Royal Army Medical Corps officer – Colonel Nicholas Tyacke (1866–1940) of the Devonport Garrison – who found their performance satisfactory. On 4 August 1914, realizing that he would soon have to relinquish the Chair of Braunton Parish Council because of his military duties, Dunn-Pattison called a special meeting of the Council for 7 August and wrote a comprehensive letter to the Vice-Chairman. In it, he set out a detailed, not to say excessively complex, scheme for helping those families who, especially in the opening weeks of the war, would be most badly affected by such wartime exigencies as food shortages, rising food prices, hoarding and the departure of the wage-earner for the front. As part of this he proposed the creation of an emergency relief fund to which he himself immediately donated ten pounds in the hope of persuading others to do likewise. The Council warmly endorsed his proposals – which were, on the whole, unnecessary. But his sense of enduring social responsibility is unmistakeable.

Dunn-Pattison as historian

Even before Dunn-Pattison moved to the West Country, he had been active as a serious historian, and he continued as such after leaving Oxford despite his multiform commitments in North Devon. Thus, over a period of eight years, he managed to publish a long essay (48 pages) in a prestigious collective work and four substantial books. He must have written the essay, on revolutionary France at war 1790–95, while he was a lecturer at Magdalen, for it appeared in 1904 as Chapter Fourteen of Volume VIII (The French Revolution) of The Cambridge Modern History (1902–12) and is an authoritative study of the five years when the revolutionary French “were once again establishing their claim to be a nation of soldiers, and were rapidly shaping their military system to meet the new requirements of the age” – in contrast to the Allies, including Britain, who “were content to abide by their old methods”. Dunn-Pattison’s first book, a collection of 26 essays on the meteoric rise through the ranks of Napoleon’s 26 Marshals of France (373 pages), followed on naturally from the long essay which, when discussing the process of reform that the French Revolutionary Army had undergone, had identified the change in character of its officer corps and the increased ease of promotion for ordinary soldiers as a key aspect of that process. The book appeared on 25 March 1909, and while one reviewer began by pointing out that it went over well-known ground in as much as the essays supported the old idea that Napoleon’s top military men were brigands working for an even bigger brigand, he ended by describing it as “decidedly good” – a conclusion that was supported by the appearance of a second edition in the same year.

His second book, an impressively thorough history of the 91st Highlanders (413 pages) – i.e. the Battalion in which he had served as a subaltern for three years after graduating from Sandhurst – was completed in October 1910 and published later on in the year. Commissioned at the request of the Regiment’s Historical Committee, it earned, quite rightly, even more enthusiastic praise: “It is quite impossible to do justice to this book, a handsome quarto […], crowded with interesting details, on the collection of which the author has spent much labour, helped by not a little private favour and regimental camaraderie.” In saying this, the reviewer, who also commended Dunn-Pattison for using, wherever possible, “original documents, some of them curious and interesting in a high degree”, was referring to Dunn-Pattison’s use of a large amount of detailed material that had not been available to earlier historians of the Regiment and to the 64 individuals who had assisted him in his researches – which must have involved a great deal of travel and no little expense. In his Introduction, he described the guiding principles behind his book as follows: “I have to the best of my ability searched the records of the past, and throughout I have endeavoured to present a fair narrative of the life of the regiment, neither magnifying the good nor slurring over the bad.” Quite apart from confirming that Dunn-Pattison was an assiduous and fair-minded historian, his “impartial narrative” explains very clearly why he was such a useful chairman of committees and valued member of the Bench.

In October 1910, a reviewer for the Literary Supplement of The Spectator noticed precisely those qualities in Dunn-Pattison’s third book (320 pages) – a 17-chapter biography of Edward, the Black Prince (1330–76), that appeared in the USA in 1909 and Britain in 1910. He commended Dunn-Pattison’s “clear and lucid” descriptions of campaigns and his “just and sane” criticisms, and described the work as “a careful and judicious survey of the printed authorities for the period, and of an adequate knowledge of what has been written in recent years, both in French and in English”. Dunn-Pattison would have been happy with such a summation, for according to his characteristically self-effacing Introduction, his study, which his reviewer saw was “not based on any new MS. material”, had “no claims to learning” but sought to “present to the general reader a sketch of the Prince’s character”. Accordingly, the reviewer concluded, Dunn-Pattison’s “traditional estimate of the eldest son of Edward III has not been affected by modern inquiry, and it sums up, not quite completely, but not unfairly, the impression he left on the men of his time”.

Dunn-Pattison completed his final book, Leading Figures in European History (471 pages), in May 1912. It appeared later in the same year and was based on similar intentions as his study of the Black Prince, for it was intended to be “a popular and not a learned book” that was addressed to the “general reader, and to the student heavily engaged with other subjects”. Its 17 chapters consist of a general, introductory account of the collapse of the Roman Empire and the ensuing chaos in Europe up to the advent of Charlemagne, “the refounder of the Roman Empire”, and 16 “sketches of the leading figures of the past”, none English or British, which illustrate “the growth of ideas and principles which have contributed to form present-day Europe”.

A superficial reading of Dunn-Pattison’s oeuvre as a historian might consider it as the typical product of a man whose interests were variegated and as such homologous with his many-sided social, political and religious life in North Devon. But on closer examination, his work involves several fundamental and consistent concerns: the constitution of the ideal state, the inherent dangers of Empire, the make-up of the good ruler, the nature of the good soldier and good generalship – and these during an eight-year period which saw social and political unrest at home, the intensification of the arms race between Britain and Germany, a reforming Liberal Government (1905–15), the reform of the British Army thanks to the efforts of R.B. Haldane (1856–1928; Secretary of State for War from 1905 to 1912), and the beginnings of unrest within the Empire at large that would ultimately bring about its demise.

Military and war service

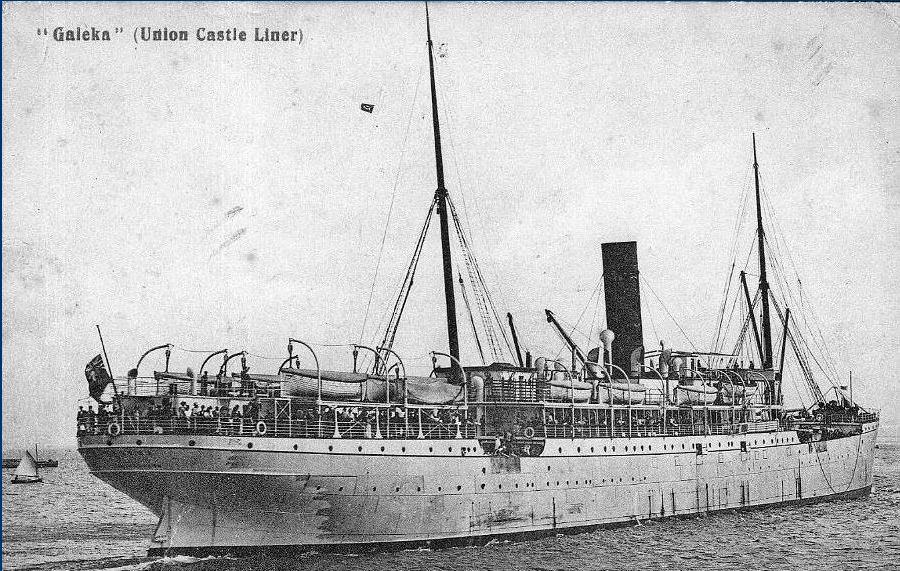

When war broke out on 4 August 1914, the 1/6th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment was under canvas at Exmouth, receiving its annual dose of serious military training. After marching to Exeter, the Battalion was taken to Perham Down, Wiltshire, on the edge of Salisbury Plain, for more intensive training, where they were inspected by Field Marshal Lord Kitchener (1850–1916) and King George V. Despite his uncertain health, Dunn-Pattison was called up as a Reservist on 7 August 1914 and on 9 October 1914, together with the 1/4th Battalion (Territorial Force) and the 1/5th (Prince of Wales’s) Battalion (TF) of the Devonshire Regiment, the 1/6th Battalion sailed from Southampton for India in a convoy of 11 ships on the SS (later HMHS) Galeka (1899–1916). (The Galeka was a passenger liner that was used first as a troop transport, then as a Hospital Ship until, on the morning of 28 October 1916, she struck a German mine five miles north-west of Le Havre and began to sink; French tugs were summoned and although they managed to tow her to the Cap de la Hague, where there is now a memorial to her and the 19 Royal Army Medical Corps personnel who died, she was declared a total loss despite being beached.)

On 19 October 1914 Dunn-Pattison was formally appointed as the 1/6th Battalion’s Adjutant. The three Devonshire Battalions were the first TF Battalions to be sent abroad on active service and their task was to replace more experienced Regular troops who were serving abroad on garrison duty and were now urgently needed on the Western Front. Just before reaching India, the convoy split into three so that the 1/4th Battalion could take over duties at Ferozepore, the 1/5th at Multan, and the 1/6th at Lahore. Dunn-Pattison’s Battalion disembarked at Karachi, now the capital of Pakistan, on 11 November 1914, entrained, and travelled 800 miles inland for two days and two nights to the Napier Barracks, Lahore, one of the two biggest cities of the Punjab, where it had its HQ for the next year. Mary Winifred Dunn-Pattison soon joined her husband, and was still living there at the time of his death. She arrived back home in Braunton on 5 May 1916 and continued to live there until spring 1922 (see above).

But on 5 November 1914, i.e. just six days before the Battalion arrived at Karachi, Britain and France declared war on the Ottoman Empire; on 6 November the British began an offensive against the Turks in southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq); and on 22 November the British captured Basrah, the country’s major port. For a year, the British campaign there went well, with victories over the Turks at Quma, Nasiriyeh and Es Sinn (see below). It also achieved its two major strategic aims: an increased reputation in the Arab world and the assured defence of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s pipe-line across the desert that ended in its refineries at Abadan, which were situated in Persia just across the border with Iraq on a waterway called Shatt-el-Arab.

The 1/6th Battalion arrived at Lahore during the cool season, and although none of the regimental histories has much to say on the matter, nearly became embroiled in a political act that was known as the Ghadar Mutiny and could have cost it many of its members. The idea, with German support, had begun in the USA, and in October 1914 several thousand supporters of a Pan-Indian rebellion against British rule were infiltrated back into India in order to foment armed revolt and mutiny within the Indian Army, starting in the Punjab. The preparations came to a head in February/March 1915, but were known to the police and intelligence services so that the plan to murder British garrisons, such as the 1/6th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment in Lahore, never materialized. But in Lahore in April 1915, 291 of the conspirators were tried under the terms of the Defence of India Act (1915), and of these, 42 were condemned to death, 114 were sentenced to life imprisonment, 93 were imprisoned for various shorter terms, and 42 were acquitted. The Viceroy of India from 1910 to 1916, the 1st Baron Hardinge of Penshurst (1868–1944) and P.R. Hardinge’s Uncle Charles, was so shocked by the extreme nature of the sentences when he visited Lahore, that he commuted most of the death sentences.

Between 15 and 17 March 1915, the 1/6th Battalion took and passed the so-called “Kitchener Test” which meant it, as a Territorial Battalion, could do a 15-mile march, attack an entrenched position with ball cartridge, lay out a bivouac, advance and then retreat for two miles, fortify a position, relieve another unit in trenches by night and then take over the trenches from them, fight using bayonets and perform physical drill correctly. On 10 May 1915 the Battalion reorganized itself according to the Double Company system. In July/August 1915, Company Quartermaster Sergeant-Major Thomas Ernest “Edward” Snow (1885–1925), an estate agent’s clerk and well-known West Country footballer, wrote a long and up-beat letter from Lahore to Mr John Yeo Tucker (1848–1920), Braunton’s newsagent and Town Crier.

John Yeo Tucker (1848–1920)

(Photo courtesy of Braunton Museum, North Devon)

The Cross Tree was a 300-year-old elm that stood in the centre of Braunton until 1935, when it was felled to make way for motor traffic. Parish Council meetings were sometimes held there.

(Photo courtesy of Braunton Museum, North Devon)

Snow’s letter was accompanied by a selection of photos from India and published in the North Devon Journal on 26 August 1915. It reads:

I feel it my duty to write, on behalf of the many Brauntonians now serving their King and Country in India, to thank you for your very kind remarks about us in your speeches under the Cross Tree, Braunton. It will no doubt please you to hear that although 7,500 miles from home[,] we receive the North Devon Journal every week. Like yourself, I am proud of the way Braunton has responded to the call; and speaking of the 1/6th Devon Regiment here in India, I might say we have some of the finest fellows that ever donned the King’s uniform. Not long ago our Company won the Battalion prize for the best shooting Company in the Regiment; whilst Sergt. [George Robert] Dray’s [1879–1950, Market Gardener] famous section took the prize for the best shooting section in the Regiment. Also, at the sports we won three first prizes, besides seconds and thirds. You can tell the dear ones whom we have left behind that we are being well looked after by Capt. Dunn-Pattison who is our Adjutant, and a better officer or keener business man it is impossible to obtain. ’Tis a common sight to see him, when his work is done for the day, driving out men, who are in hospital, in his carriage for a country spin. Is there any wonder he is so popular amongst his men? I admit it is very hot out here (sometimes 115 in the shade), and the food here is hardly as palatable as Butcher [Alfred William] Drake’s [1870–1939] beef, but such beef is unobtainable in this country. Of course, some of us have had fever (a kind of English influenza), but the majority of us are as healthy as the proverbial trout. The very lowest paid private gets 9s. a week pocket money, after all stoppages are deducted. If married, his wife gets an extra weekly Government allowance sent her, and taking into consideration the fact that we get all our clothes, board and lodging free, I don’t think we have much to grumble about. Why, the sea trip out was worth pounds, and have we not seen all nations and heard all languages, to say nothing about our three months’ stay in the cool climate of the Himalayan Mountains during the worst of the summer? Then we were at Amritzar [sic] for three months about Christmas-time, and at present we are at Lahore Fort, where the ancient buildings, &c., cost several millions of pounds and the ground covers 50 acres. We are attached to the 73rd Co[y], Royal Garrison Artillery, and a finer stamp of a “Regular” never stepped into a shoe. We are anxiously waiting to go to the Front, where I feel certain we shall give a good account of ourselves. Of course, you have heard that Sergt. [Thomas] Newcombe [1881–1916; killed in action on 29 August 1916 and buried in Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery] has gone to the Persian Gulf. I can tell you he was one of the most popular men in the Regiment, and I know of no Sergeant more capable. I miss him greatly, but hope he will live to narrate his experiences when the War is over. Tom is a soldier and a man. I have, of course, been closely connected with him a lot during the War, and to know him is to respect him. Well, I am afraid I must be off, as duty calls, but before I say goodbye I should like to give my love to the Braunton boys at home. Tell them, from me, to don the King’s uniform immediately, as one volunteer is worth ten pressed men. Tell them also that it will then, and only then, be their proud boast one day that they helped to save England. “A friend in need is a friend indeed”.

After a year of garrison duty in Lahore, the men of the 1/6th Battalion were starting to get restless because of the tedium that was caused by the heat and lack of action, but on 17 December 1915 orders reached the Battalion that they were to mobilize for Mesopotamia. Of the 711 other ranks (ORs) on the Battalion’s strength, 127 were declared unfit for the transfer, 39.4% because of bad teeth. So on Christmas Day 1915 the Battalion was sent to a rest camp prior to the long journey to the coast, and on 29/30 December, after compensatory drafts had been received from the 1/4th and the 1/5th Battalions of the Devonshire Regiment, 32 officers and 642 ORs of the Battalion – plus Brigadier-General Gerard Christian (c.1868–1930), the GOC (General Officer Commanding) the 36th (Indian) Infantry Brigade and his staff – embarked on the SS Elephanta (1911–39) in order to sail to Mesopotamia, where the military situation had worsened dramatically. A member of the 1/6th Battalion, almost certainly an officer, wrote a brief report on the Battalion’s move from India to Mesopotamia and the subsequent events that was published in the North Devon Journal on 15 August 1916 and began as follows:

Whilst preparing this article, two lines of Tennyson, which seemed to me to be very appropriate, flashed across my memory. They are – “Not once, nor twice in our rough island story / Has the path of duty been the path to glory” [‘Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington’, VIII: 201–2 (1852 and 1853)]. Little did any of us think, when reciting this poem in our school days, that we should ever follow that path in the years to come. But the call came for us – the Motherland needed us – and we obeyed that summons, and on the distant sun-scorched plains of Mesopotamia we are doing our bit for our King and Country. We have left many of our comrades beneath the soil, and many hearts in North Devon will be sorrowing to-day for loved ones they will never see on earth again.

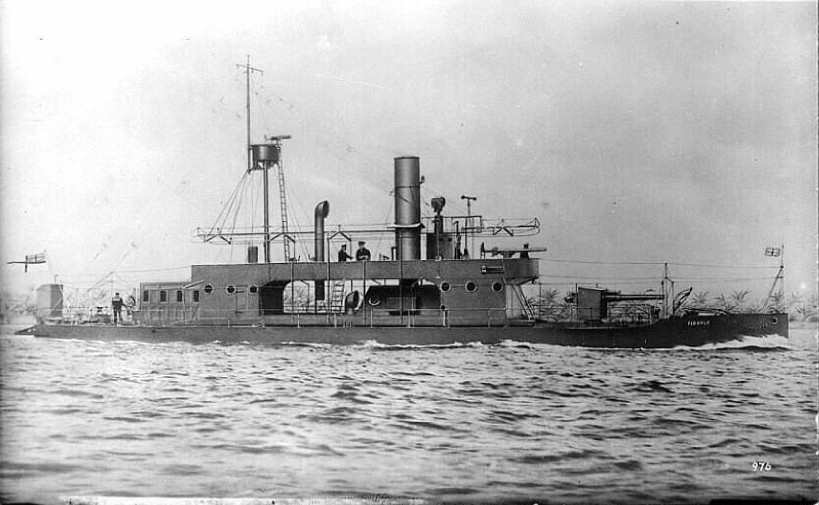

The background to the 1/6th Battalion’s involvement in the Mesopotamian campaign was roughly speaking as follows. On 24 October 1915, Major-General Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend (1861–1924) was given command of an Anglo-Indian Army of c.13,500 men, mainly Indian, and leave to advance on Baghdad from Basrah (Basra), c.280 miles away to the north-west, along the banks of the relatively shallow but winding Tigris River, which flowed southwards through the desert and into the Persian Gulf a few miles below Basrah. By 19 November 1915, after a two-week march in very bad weather, supported by shallow-draft vessels that included a new gun-boat, HMS Firefly (1915–24; sunk by insurgents on the River Euphrates, Iraq, on 15 April 1924), the Anglo-Indian Army, designated Indian Expeditionary Force ‘D’, had reached Zor, c.40 miles south-east of Baghdad.

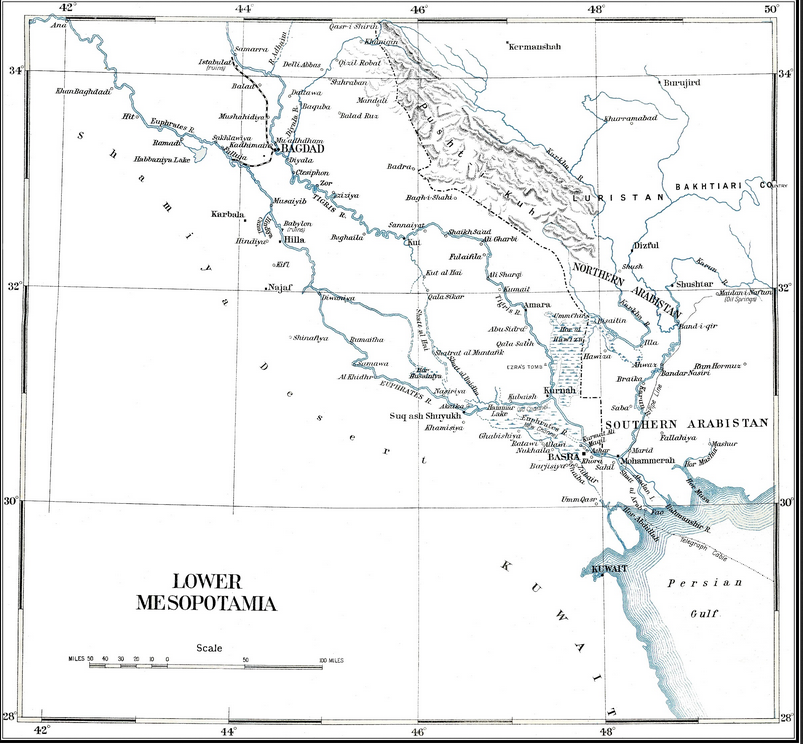

Southern Mesopotamia

HMS Firefly (1915–24)

But after the inconclusive and very costly Battle of Ctesiphon (“Pistupon” in the argot of the British soldier; now Al Madain), on the west bank of the Tigris, 16 miles south-east of Baghdad and c.380 miles from Basrah, on 22 November 1915, the depleted Anglo-Indian Force was compelled to withdraw slowly along the River Tigris to Kut-el-Amara, a small town c.40 miles downstream of Baghdad on a loop in the Tigris and roughly 230 miles north-west of Basrah overland. The Force arrived at Kut by the evening of 2 December, where it was reinforced by a small garrison of mainly British troops, who increased its total number to c.10,400 men. Of these, c.40 were members of the 1/6th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment, who had been sent to Mesopotamia much earlier in 1915, in two drafts commanded by Lieutenant Horace George Waldram (1890–1969) in order to bolster the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Dorsetshire Regiment, part of the 16th (Indian) Brigade in the Poona Division, and now part of a scratch Battalion that was known officially as the Composite English Battalion and colloquially as “the Norsets” (= Norfolk + Dorset).

But Kut was very soon surrounded by pursuing Turkish forces under Colonel (later General) Nureddin Ibrahim Pasha (1873–1932; also known as Nurettin Bey and Nur-ud Din Pasha), who, with unexpected brilliance, had blocked Townshend’s way to Baghdad at Ctesiphon in the temporary absence of his superior, Field-Marshal Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz (1843–1916), the last German General to command Turkish troops during World War One. The resultant siege of Kut began in earnest on 7 December 1915 and lasted, despite the garrison’s lack of provisions, until 29 April 1916, when, after 147 days, the survivors finally surrendered. Townshend’s first major attempt to break out of Kut took place, unsuccessfully, on 9 December, and on 17 and 23 December the Turks attempted, equally unsuccessfully, to take the town by storm. But on 2 December 1915, Anglo-Indian reinforcements had begun to arrive from Egypt and India at the as yet unmodernized port of Basrah, which had been in the Allies’ hands since 22 November 1914, and throughout the rest of the month, Anglo-Indian units, now part of the newly formed Tigris Corps, advanced up-river in appalling weather in order to form an Army that would be able to raise the siege at Kut. Their GOC was Lieutenant-General Sir Fenton John Aylmer, VC (13th Baronet) (1862–1935), who had landed in Mesopotamia during the first week of December, and by 12 December, when he arrived at Amara, c.65 miles north of Basrah, a large body of troops, mainly Indian, had already got past that town and was advancing northwards up the River Tigris to Ali-al-Gharbi, about 40 miles away. By the evening of 5 January 1916, just over half of Tigris Corps, c.14,000 men, were within five miles of the town of Sheikh Sa’ad, on a wide bend of the Tigris c.30 miles due east of Kut. During the afternoon of 9 January 1916, elements of the Corps under Major-General Sir George Younghusband (1859–1944), who had distinguished himself as a Staff Officer during the relief of Chital (March–April 1895), when General Townshend was the Commanding Officer of the beleaguered British troops there, captured Sheikh Sa’ad itself after a fierce battle (cf. A.F.C. Maclachlan).

View of Kut-el-Amara

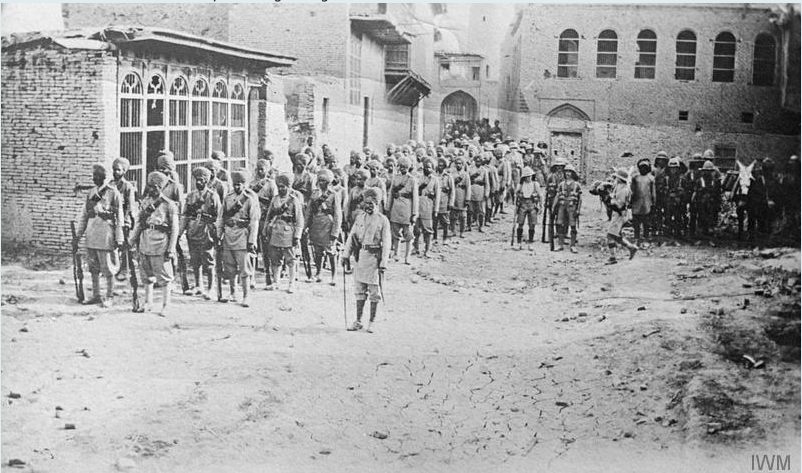

Indian (Sikh) infantry halted in the street of Kut (February 1917)

Meanwhile, after spending five days at sea, which, according to the North Devon Journal, “passed very pleasantly” as the “fellows [found] plenty to do to occupy their time” and “were in the best of spirits, and eager to get into the firing line”, Dunn-Pattison’s 1/6th Battalion arrived at Basrah on 3 January 1916 as part of the gradual build-up of Imperial forces in Mesopotamia and became part of the 36th (Indian) Infantry Brigade, consisting of two British and six Indian Battalions. After being forced to stay on board ship for a couple more days, “which delay to us seemed endless”, the 1/6th Battalion finally disembarked on 6 January, and having received a signal while at sea that all reinforcements were required immediately at the front, the Battalion began its operations in Mesopotamia by marching “about four miles” to McKenna Camp at Makina Messus, where it stayed for four days in reed huts that were situated in a palm grove and largely under water because of the winter floods. Thanks to the floods, the river transport, too, was “woefully inadequate” and the Battalion was compelled to become part of the 12,000-strong contingent that would spend the rest of January marching northwards along the River Tigris “in real earnest” in order to join Aylmer’s new Tigris Corps.

The Battalion took 22 days to march the 227 miles “of mud, filth, cold, starvation and isolation” and reach the front line, in a journey that was particularly gruelling because of “innumerable hardships” that were “difficult for those at home to imagine” such as bitterly cold nights and sharp frosts in a country that was known, conventionally, for its deserts. And quite apart from a numerically superior enemy, Aylmer’s Anglo-Indian troops had to cope with “practically every disease under the sun, and also the heat and dust in the summer, and the mud and water in the winter”. Moreover, there were no metalled roads along the River Tigris “with its endless difficult bends”, but merely rough tracks, and the persistent and heavy winter rain had caused the river to swell and flood, thereby creating a sea of heavy mud in some places which, according to one survivor, was as bad as if not worse than its Flanders counterpart, being able to rip the soles off men’s boots, force them to march in water that came up to their waists, and spend the night sleeping on patches of mud in their drenched clothes without cover of any sort and no protective clothing apart from the thin, Indian-issue drill uniforms, the Indian Government having decided that Mesopotamia was a “hot” country, even in winter. Moreover, there was little or no fuel for fires because the mahalas, wind-powered Arab river boats weighing 20 to 30 tons whose job was to carry stores, could not keep up with the advance on account of the floods. Consequently the men had to cope with these physical hardships on a diet of half-rations consisting of a tin of bully beef and two biscuits a day “with no variation of any sort except, possibly, a very occasional tin of Australian jam”.

The floods often extended miles in every direction, forming a demoralizing “waste land of water as far as the eyes could see without trees to break the monotony and utter desolation”. But the men managed to cope with both the physical and the psychological hardships of the long march, thanks to a spirit of good-humoured comradeship which one of their officers later described as “cheerful and unselfish, turning everything into a laugh, quacking and joking like ducks the deeper the water became and helping their weaker pals by, for example, carrying their rifles and giving them a hand when needed”. According to another eye-witness, Sergeant George Dray – see above – played a key part in maintaining a high level of morale by using his “magnificent voice” to sing “the Devon songs [the men] loved, and in which they could all join”. The dreadful march northwards took the column through many tiny, and by no means friendly, settlements along the Tigris which are mentioned in the Battalion War Diary but very difficult to locate on maps: Camp Gourmat Ali (“Rain very heavy & Camp a swamp”; 10 January), Camp Nahm Umr (11 January), Kurneh (Al-Qurneh), the confluence of the Tigris and the Euphrates (14 January), Sachicha (“Waterlogged – heavy rain”; 16 January), Abu Rameh (19 January), Qalat Sabih (20 January), Abu Sidrah (21 January), Al-Amarah (Amara) (23 January), Fudaiyah, near the border with Kuwait (28 January), Umm-As-Samsam (31 January), Filaif (1 February), Ali-al-Gharbi (2 February), Miathar (3 February) and Musandar (4 February).

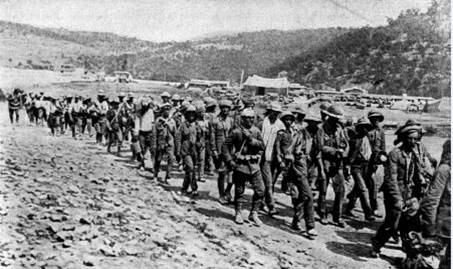

6th Devons on the “Road” to Kut, from G.B. Oerton, “Dujailah” Days (Barnstaple: H. Pincome & Son, 1948)

(Courtesy Michael Oerton Esq.)

So it was a nearly exhausted, albeit “cheerful and undaunted” 1/6th Battalion that finally reached Wadi Camp at Orah (El Saura), where the River Wadi flows into the Tigris from the north-east, on 5 February 1916, despite having seen what fate might await them when it crossed the grim battlefield of Sheikh Sa’ud, nine miles to the south-east, where a fierce battle had taken place from 6 to 8 January. According to the same officer/eye-witness, this was “the first of the ghastly and expensive frontal attacks for which these operations became famous or infamous”, when the 7th Indian (Meerut) Division had dislodged the Turks on 7 January at an overall cost of more than 4,000 casualties,

which, as is well known, could not be dealt with. Hundreds were left to die in the mud or be butchered, stripped and mutilated by those human jackals the Arabs. A battlefield in France was not a pretty sight, but a battlefield in Mesopotamia was a veritable nightmare. Swollen, naked and mutilated bodies, friend and foe, mule and camel, lying in dreadful heaps, a pitiful and mute protest to Heaven of the futility and horror of it all. […] The cruel[l]est part of the Mesopotamian campaign […[ was that it asked men to face modern machinery of destruction, without granting them the resources of alleviation of suffering which modern science provided. There were boatloads of wounded going down the Tigris, huddled on the bare decks without even covering from sleet and rain. No lint and gauze dressings, nor splints. Not enough doctors. Sufferings increased by cold, hunger, thirst, dirt, exposure and neglect. Those wounded arrived at Amara and Basra unfed, untended, with bed or rather deck sores – some dying, first field dressings eight days old, unchanged; maggots in their wounds, gangrene and other abominations too revolting to mention. Other wounded were not so fortunate as these; they were lost in the mud. All this happening within a few days voyage from India, where everything necessary abounded. Assuredly the then Government of India, who were responsible, have much to answer for.

Nevertheless, the narrator continued, although “some of those Devon lads looked a little white and sick” (after gazing for the first time on such a spectacle), he did not think that any of them “allowed their thoughts to worry them unduly. The main effect was to strengthen, still more, their resolution that those friends of theirs in Kut [i.e. two drafts under Lieutenant Waldram (see above)] must be rescued at all costs.”

The Camp at Orah (El Saura), with mahalas on the left of the photo, from G.B. Oerton, “Dujailah” Days (Barnstaple: H. Pincome & Son, 1948)

(Courtesy Michael Oerton Esq.)

Nevertheless, in common with the rest of the second wave of reinforcements, the 1/6th Battalion had missed General Younghusband’s unsuccessful attempts to break through the Turkish front line at the Hannah Gap, on the left (northern) bank of the River Tigris, between 6 and 13 January, and the First Battle of Hannah on 21 January 1916. On both occasions the Turks were more numerous and determined than expected, very well dug in along two lines of deep trenches, protected by barbed-wire entanglements, and well-supported by artillery and machine-guns. And as a result, the first attempt to relieve Kut cost Tigris Corps c.1,600 casualties (of whom 218 were fatal) and the subsequent battle cost it c.2,700 casualties killed, wounded and missing, with the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Black Watch (part of the 21st (Indian) Infantry Brigade), the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs) (part of the 19th (Indian) Infantry Brigade), and the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment (part of the 28th (Indian) Infantry Brigade), all part of the 7th Indian Division, being virtually annihilated.

The heavy rain continued throughout most of February 1916 and the resultant mud seriously impeded any kind of advance by the Allied infantry or cavalry. Flick, for example, records that 10 February was “memorable for a torrential downpour of rain, accompanied by vivid flashes of lightning and deafening claps of thunder”, so that the surrounding plain was inundated and many of the Battalion’s “live rations” were drowned. So after the setbacks of January, military actions ceased for a while. On Sunday 6 February Dunn-Pattison’s Battalion found itself manning the ramparts in Wadi Camp at Orah, where it stayed until 22 February. Life was marginally better here:

An Arab bazaar was established at Wadi which occasionally had small stocks of tinned fruit, milk, biscuits, cigarettes, and tobacco[,] but generally the troops kept a keen look-out for up-river steamers and purchased at exorbitant prices such delicacies as the crew had managed to take on board at Basra[h]. […] Cigarettes would fetch almost any price and matches were for a time quite an unknown quantity.

In the absence of military action, the 1/6th Battalion was kept busy making roads through the camp, building bunds (embankments along the river bank), manning outposts, reconnoitring the surrounding area, including the left flank of the Turkish trenches, and skirmishing with hostile Arabs of the locality. During this period, too, on 19 February 1916, the Battalion marched six miles through no-man’s-land in order to draw the enemy’s fire – but the Turks did not respond and saved their ammunition. The Battalion then marched eastwards across the desert to the Sennah Canal on the right (southern) bank of the Tigris, where, for a week, it took over the trenches that were situated about four miles south-east of the River, and after spending 29 February 1916 observing the main road between Sheikh Sa’ud and Kut, while the weather hotted up, the 1/6th Battalion returned to the Sennah Canal for another week in the trenches before taking part in the Battle of Dujailah (Dwailah) – i.e. the second major attempt to relieve Kut.

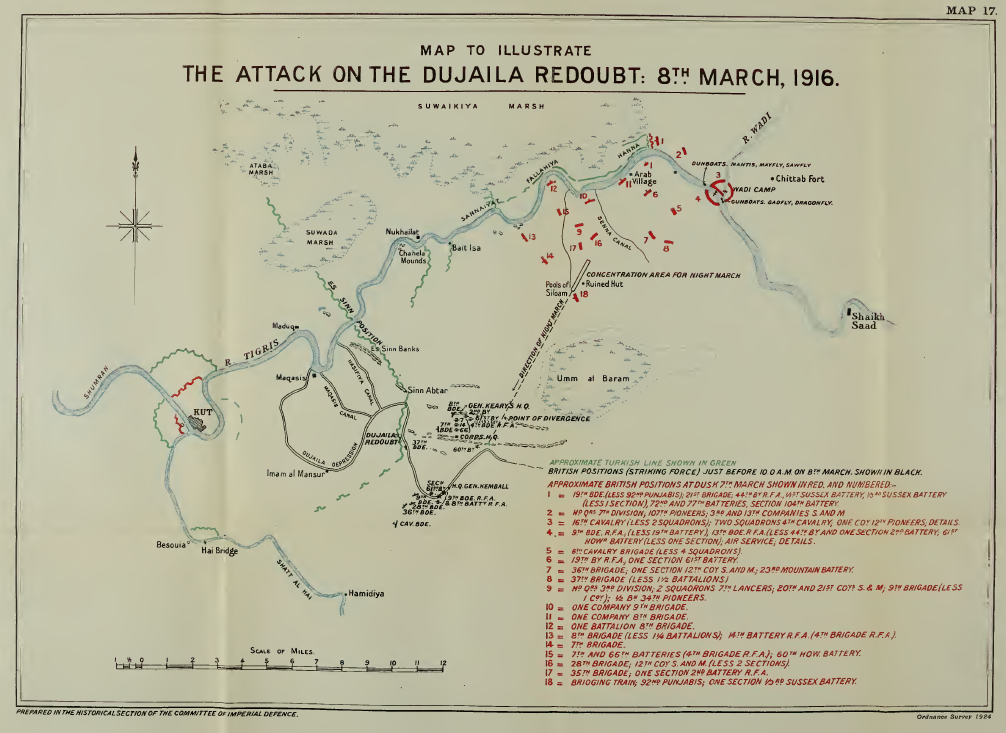

Although the February reinforcements meant that General Aylmer’s army now numbered some 23,000 men, by about 20 February 1916 he and his Staff had decided that the Hannah line on the left (northern) bank of the Tigris was too impregnable, that the “formidable” complex of interconnected enemy defences running from Hannah to Nukhailat via Fallahiya and Sannaiyat provided the Turks with ways of observing, enfilading and bombarding both a river crossing upstream at Hannah and a straightforward advance westwards along the right (southern) bank of the Tigris, and that the Suwacha Marsh on the extreme left flank of the Turkish positions north of the Tigris was impassable. Consequently, it was resolved that in early March, at night and under conditions of the greatest secrecy, an Anglo-Indian Force of c.20,000 men would cross to the southern side of the Tigris, pivot round the enemy’s rear, and cut their lines of communication, thereby forcing them to evacuate the northern bank of the Tigris for fear of being encircled from the south-west. Mainly because of the weather, the operation was postponed twice, but by dusk – c.18.30 hours – on 6 March 1916, most of an Allied Force (“Aylmer’s Force”) had crossed from the left to the right bank of the Tigris in considerable secrecy and the rest followed after sunset on 7 March and assembled near the Pools of Siloam, i.e. in the desert three miles south of the Tigris and about eight miles due north of the Umm Barram Marshes. At 22.22 hours, the Force was to start crossing the open desert in a south-westerly direction for 13 miles, keeping between the marshes and the river, until, by dawn on 8 March, it reached a “point of divergence” that was three miles east of the Dujailah Redoubt and near the serpentine wadi or nullah called the Dujailah Depression (see map).

Map 17 from Frederick James Moberly, The Campaign in Mesopotamia, 1914–1918, 4 vols (London: HMSO, 1923–27), ii, unpaginated

From there, the Force was to break though the nearby Turkish defences and open up the way to Kut. But the Schwerpunkt of the Turkish defences was formed by groups of mounds some 20 foot high that were crowned by the Sinn Aftar and Dujailah Redoubts. These were well-fortified anchor points that were situated at the southernmost end of a seven-mile-long line of trenches known as the El Sinn Position (see map), and Oerton described them as a “sheer glacis 25 foot above the plain”. Most of this formidable line was on the right (southern) bank of the Tigris and formed the only entrenched Turkish position below Baghdad. But as it straddled the River about eight miles downstream from Kut, it also formed an outer defensive rampart to the east-south-east of the besieged town, and as the two large Redoubts were about the same distance south-east of Kut, they formed the apex of an almost equilateral triangle where, it was hoped, the attacking troops would be able to surprise the Turkish defenders and link up with a force that emanated from Kut itself – though because of the events of the following day, this hope was never realized.

Confusingly, Aylmer’s Force was divided into three unequal groups comprising four Columns and a mix of units, most of which were unfamiliar with and had not trained with one another. The first group, known as “Kemball’s Force”, consisted of Columns ‘A’ and ‘B’ under the overall command of Major-General Sir George Vere Kemball (1859–1941), but with Brigadier Christian commanding Column ‘A’; the second group was formed by Column ‘C’, commanded by Major-General Sir Henry D’Urban Keary (1857–1937), the GOC 3rd (Lahore) Division; and the third group was formed by Column ‘D’ and consisted of the 6th (Indian) Cavalry Brigade, four regiments totalling 1,150 men, that was commanded from February to May 1916 by Brigadier Robert Campbell Stephen (b. 1867 in New South Wales, d. 1947). The night, which followed a day of tropical heat, was bitterly cold and the cross-desert route caused an endless number of unavoidable halts, “than which nothing is more tiring for troops, especially when carrying a heavy load as was the case on this occasion”, as it was impossible to know how long the halt would last and equally impossible therefore to know what opportunity for rest or sleep it afforded.

The Force began to reach the “point of divergence” between about 06.30 and 07.00 hours and split up as ordered. Column ‘C’, consisting of the 7th and 8th (Indian) Infantry Brigades from the 3rd Indian (Lahore) Division (6,500 men), was to turn westwards and advance towards the Dujailah Redoubt itself. Column ‘A’, consisting of the newly arrived 36th and 37th (Indian) Infantry Brigades and the 9th (Indian) Infantry Brigade from the 3rd (Lahore) Division, was to separate from Column ‘B’, hook round to the south of the Redoubts in the general direction of the village of Imam al Mansur (see map), and then turn due north towards a newly constructed line of Turkish trenches that ran south-west from the Redoubt. Column ‘B’, consisting of the 28th (Indian) Infantry Brigade, also from the 3rd (Lahore) Division, was to give up its position as Corps Reserve behind Column ‘A’ and form up separately by 06.15 hours, i.e. just after dawn, in order to attack the Turks from the east, aiming at a point between the Dujailah and the Sinn Aftar Redoubts, with Column ‘A’ protecting its left flank. And Column ‘D’ was to serve as a mobile flanking guard in the open desert on the left flank (i.e. in the south) of the main assault.

Aylmer’s plan was detailed and complex, and whilst stressing secrecy and surprise, it left little to the initiative of individual commanders. Nevertheless, despite some delays and confusion during the initial night-time march and considerable practical difficulties – General Kemball, for instance, had not had sufficient time to study the plan – the Force reached the “point of divergence” near the Dujailah Depression on time. General Aylmer promptly established his Corps HQ there but much to his surprise, no sign of a Turkish presence, let alone of Turkish activity, could be discerned in the Dujailah Redoubt, a situation that would be confirmed to Aylmer at 09.50 hours by Major (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO) Gerard Leachman (1880–1920; murdered in Iraq), an Intelligence Officer on the Political Staff who could pass as an Arab and did his reconnaissance work dressed in Arab clothes. So when Brigadier Christian asked his superior General Kemball for permission to attack the Redoubt immediately, i.e. at 07.15 hours, Kemball, fearing that the Turks were bluffing as they had done on several occasions in the past, refused the request on the grounds that because adequate preparations had not yet been completed, the Brigade artillery could not give the Column any covering fire. So even though elements of Brigadier Christian’s 36th Brigade, including the 1/6th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, had been successfully deployed since first light in clearing Turkish trenches towards the Shrine of Imam Al Mansur, and even though the Corps artillery had been allowed to open fire on the Turkish camp to the south of the Redoubt at 07.00 hours, followed by Kemball’s own divisional artillery at 07.15 hours, the main infantry assault by the 9th and 28th Brigades was postponed until 09.30 hours. But by this time the Turks had become aware of the presence of the Anglo-Indian Force; the Turkish Commander was bringing up reinforcements from his Reserves; and the crucial element of surprise had been irretrievably lost. Three years later, the correspondent for the Western Morning News would comment: “Had it been possible to launch the infantry attack immediately with greater strength, the road to Kut would have been open.”

Although the War Diary of Dunn-Pattison’s 1/6th Battalion says very little about its part in the Battle of Dujailah, Volume Two of Brigadier Frederick James Moberly’s (b. 1867 in Madras, d. 1952) detailed and professional history of the Mesopotamia Campaign (published in 1924 as part of the Official History of the War), ties in well with a series of four articles on the 1/6th Battalion’s experience in India and the Middle East that had been written by a member of the Battalion and appeared anonymously in the Western Morning News (Plymouth) in August 1919 – and at least one of which, dealing with the attack at Dujailah, also appeared in the Western Daily Journal on 7 August 1919. At dawn on 8 March 1916, the 1/6th Battalion, which formed part of Christian’s 36th Brigade and had been reinforced two days earlier on 6 March by a party of eight officers and ORs, all straight from England, was taking cover in open or “skirmishing” order next to a battery of field guns in a “nullah” (a gully, ravine or river-bed) on the extreme left of the Allied front line and probably part of the Dujailah Depression – with the Redoubt over to their right. Then at 09.35 hours, i.e. after a delay of three-and-a-half hours, the 36th Brigade had, as part of Column ‘A’, begun to advance towards the trenches near the shrine of Imam Ali Mansur, with the 82nd and 26th Punjabis in the first line on a frontage of 600 yards, the 1/6th Devonshires and a Company of the 62nd Punjabis in the second line one thousand yards behind, and the Brigade’s machine-guns moving forwards on the left flank. The idea was that the 36th Brigade should capture the Turkish trenches at the southern end of the Redoubt and encircle the Redoubt from the south in a clockwise manoeuvre. Although the Turks, large numbers of whom had been seen running into the trenches, opened up almost immediately with heavy rifle fire, by 11.30 hours the 36th Brigade had taken the trenches – which the Turks had evacuated before the men of Column ‘A’ could reach them.

But then, at around noon, Kemball asked Christian if he could assist Keary’s 28th Brigade, which had been driven back by the Turks during the morning and taken heavy casualties, by advancing northwards on their left and supporting their eastwards attack on the Dujailah Redoubt. Christian agreed, but as this move required a change of direction so that the 36th Brigade faced the Redoubt, he had to withdraw his line south-eastwards for about a mile so that its constituent units could reform. Dunn-Pattison’s 1/6th Battalion began the move to its new position at c.13.00 hours and the attack itself , with the 36th Brigade now supporting the 9th and 28th Brigades, began at 14.00 hours after a ten-minute artillery bombardment which was ineffectual because it was directed against the Redoubt itself rather than the trenches, where the Turkish defence was hardening. But the distance from the start line to the objective was not – as had been wrongly reported to Aylmer and his Staff – 500 but 1,500 yards. So the attackers, most of whom had already been through a hard night carrying a 60-pound load, comprising two days’ rations, kit and ammunition, across the desert, and had added to the mileage by the morning’s fighting, were now required to charge across over a mile of open desert towards a new objective in blistering heat with very little water and inadequate artillery cover. Furthermore, this time Dunn-Pattison’s 1/6th Battalion found itself in the first line of the attack, with the 53rd Sikhs and the 56th (Indian) Rifles on their left and the 3rd (Indian) Infantry Brigade behind them in the second and third lines. The Western Daily Journal described the assault as follows: