Fact file:

Matriculated: 1894

Born: 22 July 1875

Died: 22 March 1918

Regiment: King’s Royal Rifle Corps, attached to Rifle Brigade

Grave/Memorial: Savy British Cemetery: I.G.13

Family background

b. 23 July 1875 at the Vicarage, Newton Valance, Hampshire, as the fifth son (eighth child) of the Reverend Archibald Neil Campbell Maclachlan (1820–91) and Mary Elizabeth Maclachlan (née Sidebottom) (1832–1925) ( 1855). At the time of the 1881 Census the family lived in the Vicarage, Newton Valance (six servants); the father died two weeks before the 1891 Census, but the family still lived in the Vicarage (seven servants); by 1901 Mary Elizabeth had moved to 8, Rockstone Place, Southampton (three servants); and by the 1911 census she had returned to Newton Valance and lived in The Cottage (two servants).

Parents and antecedents

Although Maclachlan’s father was of Irish extraction, he was a member of Clan Maclachlan of Strathlachlan and one of the two sons of Lieutenant-General Archibald Maclachlan (1780–1854), who served in Spain during the Peninsular War. From 1838 to 1841 Maclachlan’s father studied at Exeter College, Oxford (BA 1841, MA 1844), and in 1860 he became the Vicar and Patron of Newton Valance, Alton, Hampshire, a cure of 362 souls that was worth £512 p.a. Maclachlan’s father was a popular figure in the parish and diocese, and the parish church, which dates back to the thirteenth century, was full to capacity at his funeral. His otherwise calm and well-ordered life was disturbed on 23 February 1882 by an “exhausted and half-starved young man” who fell down “in a fit” at the gate of his vicarage. On 2 March 1882, that same young man, one Roderick Maclean, tried to assassinate Queen Victoria by firing a pistol into her carriage as she was leaving Windsor railway station – the eighth and last of such attempts. He was arrested and as Maclachlan’s father was a witness to the incident, he gave evidence at Maclean’s trial for high treason on 20 April: the jury found Maclean “not guilty but insane” after five minutes’ deliberation and he was confined to Broadmoor until his death in 1921. Queen Victoria was not pleased by the result of the trial and had the law changed so that in similar cases in the future, the verdict would be recorded as “guilty but insane”. The incident was immortalized by William Topaz McGonagall (1825–1902) in a poem entitled ‘Attempted Assassination of the Queen’.

The Campbell name came into the family through Maclachlan’s maternal grandmother, Jane Campbell (1782–1868), the daughter of Neil Campbell of Duntroon (1734–98), who came from a distinguished military family. Her eldest brother, James (1773–99), was killed at the Battle of Helder in 1799 serving with the 79th Regiment of Foot, which in 1804 became the Cameron Highlanders. Her brother Neil (later Sir Neil) Campbell (1776–1827), who fought in the Napoleonic Wars, was chosen by Lord Castlereagh to accompany Napoleon to Elba with the instructions “that he was not to act as his gaoler, but rather to put the former emperor in possession of the island of which he was to be the sovereign prince”. He was in Italy when Napoleon escaped. He became a not wholly successful governor of Sierra Leone, but was “apparently insecure and haunted by Bonaparte’s escape”. A third bother, Patrick Campbell (1779–1857), joined the Spanish Army in 1809 and fought in the Peninsular Campaign, becoming aide-de-camp to the Duke of Albuquerque and eventually being appointed Major General. In 1823 he left the army and became a diplomat serving as Chargé d’Affaires in Bogota and Consul General in Egypt and Syria (1833–1840).

Maclachlan’s mother was the daughter of Charles John Sidebottom (1790–1878), a Worcestershire barrister and JP for the counties of Hereford and Worcester.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Mary Abigail Campbell (c.1860–1941);

(2) Eveleen Campbell (1862–1953);

(3) Archibald Campbell (later Reverend) (1864–1944);

(4) Neil Campbell (1866–1908);

(5) Lachlan Campbell (b. 1868, d. 1895 in Rawalpindi);

(6) Elsie Jean Campbell (1869–1903);

(7) Ronald Campbell (later Acting Brigadier, DSO) (c.1873–1917; killed in action near Locre in the Ypres Salient on 11 August 1917, aged 45, while commanding the 112th Infantry Brigade); married (1908) Elinor Mary Trench (b. 1872 in Sydney, d. 1949), and they lived at Rookley House, King’s Somborne, Hampshire;

(8) Ivor Patrick (1877–1918).

In 1900, the seven oldest children were left £1,000 or more by their mother’s wealthy brother, Colonel Leonard Sidebottom Venner (c.1830–1900), formerly of the 72nd Foot, which had become the 1st Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders, in 1881.

None of the three daughters ever married and all lived in the Vicarage at Newton Valance until their deaths, as did Ivor Patrick, who also never married. Eveleen, who outlived her other siblings, seems to have been particularly religious, for of the £53,621 that she left in her will, £6,000 went to the local church, and several other substantial legacies went to missionary organizations and the Field-Marshal Lord Montgomery Home for Boys.

Archibald attended Eton College and was a Commoner at Magdalen College, Oxford, from 1884 to 1888, where he read for a Pass Degree (BA 1890). While at Magdalen he rowed for the 1st VIII and was part of the crew that went Head of the River in 1886 and 1888 – which would explain why, in 1891, he took his MA alongside Guy Nickalls (see G.S. Maclagan). He was ordained deacon in 1892 and spent a year as the Curate of Slinfold, near Horsham, Sussex. He was ordained priest in 1893 and then spent two years as a curate at Lower Beeding, near Horsham, Sussex, before succeeding his father in 1895 as Vicar and Patron of Newton Valance, Alton, Hampshire – a living which he held until his death in 1944.

In 1888, Neil was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders, and in 1895 he was promoted Captain. In April 1898, during the final phase of the war to take back the Sudan from the fiercely Islamic Mahdi who had seized control there in 1882, he was slightly wounded in the shin, but on 2 September 1898 he took part in the Battle of Omduran, the final battle of the war, during which he came to the notice of Major General Sir Herbert (later 1st Earl) Kitchener (1850–1916) for his good service. In February 1908, now a Major, Neil took part in the two-week-long punitive expedition against the Pathans (Pashtun) in the Bazar Valley, on the Afghan side of the North-West Frontier; on 24 May 1908, a week before the end of the punitive expedition in the same area against other Pathan tribes – the Utmanzai, Dawezai and Baezai Mohmands – that was commanded by General Sir James Willcocks (1857–1926), he died when his revolver was accidentally discharged in its holster.

In 1888, Lachlan was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC), of which he became Adjutant in 1893. As he died in Rawalpindi on 10 March 1895, he almost certainly did not take part in the campaign to relieve Chitral, on the Afghan–Russian border, which ended on 20 April after the 400 Anglo-Indian defenders had been besieged there by several thousand Afghans under Umra Khan since 3 March. And as his family did not include him on the tablet that commemorates his three “soldier brothers” who died on active service (see below), it is probable that he died of natural causes or in an accident that was unconnected with his military duties. He is commemorated by a tablet in Christ Church, Rawalpindi.

Ronald (“Ronnie”) was educated at Eton and the Royal Military College (Sandhurst), and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade in 1895. He saw active service in the Second Boer War, was severely wounded, went through the siege of Ladysmith (30 October 1899 to 28 February 1900), and was mentioned in dispatches twice. He also saw service in Tibet during the unpopular invasion of that country by a British force under Brigadier-General (later Sir) James Macdonald (1862–1927) that lasted from 11 December 1903 to September 1904 because of fears, probably unfounded, that the Russians were trying to end the country’s neutrality and absorb it into their sphere of influence. From 1908 to 1912 he was the Adjutant of the newly formed Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps and was appointed to command it as Acting Lieutenant-Colonel in June 1914. (He was awarded an Honorary MA in 1912.) On 21 August 1914 he helped raise the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade at Winchester, in which B. Pawle was already a subaltern, and on 28 August 1914 he wrote a longish letter to President Warren which throws light on the current shortage of officers and the concern that it was causing both men:

Re freshmen, I think all those, who have had any Training, & are fit to serve, should at once apply for commissions in the New Army, especially boys from the good schools. If the boys you mention have been admitted to a College, then they should at once apply to the Adjutant O.T.C. & he would find a day for them to come before the nomination board. In only a few cases have under-graduates been advised to come up next term & combine their work with training in the O.T.C. The question of officers is so serious that we want all we can get at once. When appointed, these young gentlemen would be ordered to join a Training Camp for one month, before going to their Regiments.

Nearly 15 months later, Ronald was clearly still exercised by the same problem, for in a letter to Warren dated 20 November 1915 he wrote: “Needless to say, I should be delighted to take any nominee of yours, & especially a Magdalen man.” On 30 September 1914, Ronald wrote another letter to Warren, in which he explicitly mentioned Pawle “– who I think was at Magdalen – a very charming fellow, & quite the type you turn out almost automatically” as one of his “best officers”. Ronald was still the Battalion’s Commanding Officer (CO) when it disembarked in France on 20 May 1915 as part of the 41st (Greenjacket) Brigade in the 14th (Light) Division, and as such he was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel in June 1915. He survived the débâcle at Hooge when, just after 03.00 hours on 30 July 1915 (see B. Pawle), the Germans poured a hail of artillery and mortar fire and torrent of liquid fire on the unprepared 8th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, but, according to Alexandra Churchill’s account, he was very badly shocked by the carnage. Six of the 8th Battalion’s 24 officers were killed in action, ten were wounded, three were listed as missing believed killed, and only five survived unharmed, and besides that some hundreds of ORs (other ranks) were gone as well. According to another source, Ronald was wounded for the first time at Bellewaerde on 25/26 September 1915 – though there is little evidence for this in the Battalion War Diary. And according to a third source, he was severely wounded again on the canal bank east of Ypres in December 1915 – which is possible since, although the Battalion’s War Diary is missing for the last part of December 1915, a new CO arrived to serve with the Battalion on 13 January 1916. In May 1916 Ronald was awarded the DSO. On 7 January 1917 he was promoted Acting Brigadier-General commanding 112th Brigade, in the 37th Division. But on 11 August 1917 he was killed in action by a sniper while touring the trenches near Loker (formerly Locre) in the Oosttaverne sector of the Ypres Salient. He was twice mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, no. 29,623, 13 June 1916, p. 5,951; LG, no. 30,421, 7 December 1917, p. 12,971). He is buried in Locre Hospice Cemetery, Grave II.C.9 (ten miles south-west of Ypres).

Ronald’s wife, Elinor Mary Trench (née Cox) was one of the six daughters of James Charles Cox (1834–1912), a distinguished Sydney physician, medical educator and Natural Historian, and was originally married to Sydney Trench (1877–1905).

Education

Maclachlan attended Cheam Preparatory School, near Epsom, Surrey, from c.1882 to 1889 (cf. J.R. Platt, G.T.L. Ellwood, A.G. Kirby, L.S. Platt, R.N.M. Bailey, E.W. Benison, C.P. Rowley). Founded in c.1645 by the Reverend George Aldrich (1574–1658), it moved to nearby Tabor House in 1719, where it stayed until 1934 when it moved to its present site at Headley, Hampshire. It was sometimes known as Manor House Preparatory School because that, according to the Censuses, was the proper name of its buildings, and sometimes, from 1856, as Mr R.S. Tabor’s Preparatory School, when the Reverend Robert Stammers Tabor (1819–1900) became its Headmaster (until 1890) and set about turning it into a proper preparatory school and, arguably, the top preparatory school in the country. Maclachlan then attended Eton College from 1889 to 1894. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 16 October 1894, having taken Responsions in September 1894. He sat the Preliminary Examination in Trinity Term 1895 and October 1895 and then read for a Pass Degree (Groups B1 [English], C1 [Geometry], and B2 [French Language]). He was awarded a BA in Trinity Term 1897 and took his BA on 17 December 1897.

Alexander Fraser Campbell Maclachlan, BA, CMG, DSO and Bar

(Photo © The Greenjackets Museum, Winchester; Courtesy of Major Ken Gray)

“Alec Maclachlan, like all his distinguished brothers, was an officer of the best type, and a most gallant and charming companion. […] We can ill afford to lose men like him.”

Military and war service

On 18 October 1899 Maclachlan was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Regular) Battalion of the KRRC. During the Second Boer War (11 October 1899–31 May 1902), the Battalion took part in the actions at Colenso (15 December 1899), Spion Kop (23/24 January 1900), and Vaal Kranz (5–7 February 1900), when the British troops, commanded by General Sir Redvers Buller, VC (1839–1905), were defeated by Boer irregulars commanded by General Louis Botha (1862–1919). Maclachlan subsequently fought in the operations in the Tugela Heights (14–27 February 1900), when Buller forced the Boers to raise the siege of Ladysmith, and was severely wounded during the action on Pieter’s Hill. But he was present at the Relief of Ladysmith on 28 February 1900, an action in which his brother Ronald was also involved. He then became the CO of the Rest Camp at Machadodorp and was promoted Lieutenant on 14 November 1900. He was mentioned in dispatches on 8 February and 10 September 1901. On 29 July 1902 he was awarded the Queen’s Medal with four clasps and the King’s Medal with two clasps. On 31 October 1902 he was awarded the DSO for gallantry at Pieter’s Hill “In recognition of services during the operations in South Africa” (London Gazette, no. 27,490, 31 October 1902, p. 6,904). He stayed in South Africa with the 3rd Battalion until 1903, and then accompanied it on garrison duties to Ireland (1903–04), Bermuda (1904–05) and Crete and Malta (1908–10). He was promoted Captain on 25 August 1906 and served as the Battalion’s Adjutant from 10 December 1907 to November 1910. The Battalion was stationed in India from 1910 to 1914, and during the royal visit from 2 December 1911 to 10 January 1912 Maclachlan served as an extra aide-de-camp on the King’s staff during its central event, the huge Durbar (= court or princely gathering) of 12 December 1911, which took place to celebrate the coronation of George V on 22 June 1911. For this Maclachlan was awarded the Durbar Medal.

As Maclachlan was on leave in England when World War One broke out, he was posted to the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the KRRC, part of 6th Brigade in the 2nd Division. On 12 August 1914 he left Aldershot with the Battalion as a Captain and the CO of ‘B’ Company, and arrived at Rouen on the following day. On 15 August the Battalion travelled by train to Vaux-Andigny, well to the north-east of Paris, and from there it proceeded to billets in Hannapes, on the River Oise, where it trained for five days. On 21 August it marched north-eastwards for 15 miles in the direction of Mons and reached Landrecies; on 22 August it continued the march for another 14 miles to Hargnies; and by the evening of 23 August, after a march of 17 miles, it had arrived four miles north-east of Givry, just over the Belgian border to the south-east of Mons. Here, Maclachlan’s ‘B’ Company was ordered to dig in and on the afternoon of 23 August they experienced a lot of shelling.

The Battalion began its retreat from Mons on 24 August, when it stopped just north of the town of Bavay, 15 miles to the south-west of Mons. The retreat continued on 25 August, when the Battalion covered 18 miles to Maroilles, just to the north-east of Landrecies, making contact with the Germans as it did so. On the following day the Battalion functioned as part of the rearguard during the 6th Brigade’s withdrawal southwards to Vénérolles via Marbaix and Le Grand Fayt, and it continued to protect the Brigade’s right flank on 27 August as it withdrew along the River Oise to Hannapes and Mont d’Origny, due east of St-Quentin, and again on 28 August during a long march southwards to the small town of Amigny-Rouy, where it rested for a day. The retreat continued, with Maclachlan’s Battalion still part of the rearguard, on 30 August, via the hillier country around Barisis and Couchy-le-Château-Auffrique, until the Battalion finally crossed the River Aisne at Soissons, not long before the bridge was blown up at 22.15 hours. During the retreat southwards on 1 September, the Battalion experienced a certain amount of harassing by the Germans and took casualties for the first time. But there was still farther to go, and the Battalion continued to withdraw south-westwards in very hot weather for another four days, via Betz and Tribardon (2 September), Meaux (where it crossed the River Marne), Trilport and Montceaux (3 September) and Voisins (4 September), until, on 5 September, it reached Lumigny and Chaunes, about 40 miles due east of the centre of Paris, after a march of 22 miles.

The First Battle of the Marne, when six French armies and the British Expeditionary Force counter-attacked to drive the Germans back north-eastwards, began on 6 September, and Maclachlan’s Battalion took part in the resultant advance. On that day it marched north-eastwards towards Coulommiers, and then, on 7 September, it started from St-Siméon, just to the east of Coulommiers, marched north through Rebais and crossed the River Morin at La Trétoire. On 9 September it crossed the River Marne, occupied the hills on the northern side, and on 10 September it advanced northwards through Domptin and Coupru to the tiny village of Hautes-Vesnes, where it engaged an enemy column that was coming down the road (now the D11) from Chézy-en-Orxois to the hamlet of Vinly. Although the Battalion lost 79 of its members killed, wounded and missing, the Germans surrendered after one-and-a-half hours and 450 of them were taken prisoner. After that, the Battalion seems to have moved about 20 miles to the north-west, i.e. to the Valley of the River Aisne, where the Battle of the Aisne began on 13 September as the Allies tried to push the Germans still further back to the north-east. By 14 September Maclachlan’s Battalion was at Moussy-Verneuil, where it became involved in skirmishes in a wood 700 yards north of Tilleul. On 15 September it advanced and entrenched and from 16 to 19 September it was in the trenches and beating off a large German counter-attack that would cost it over a hundred casualties. But during the fight near Tilleul on 14 September, Maclachlan, another officer and the Company Sergeant Major were all hit and Maclachlan was sent to the rear for treatment.

A severe illness followed Maclachlan’s wounding: he was taken to hospital in Versailles and it took him nearly a year to recover. But on 1 September 1915 he was promoted Major, and he probably rejoined the 3rd Battalion of the KRRC, part of the 80th Brigade in the 27th Division, at about the same time. He made his first appearance in the Battalion’s War Diary on 26 October 1915, when he was given command of the Battalion in the absence of Lieutenant-Colonel W.J. Long (who returned on 3 November). At that time the 3rd Battalion was resting in billets to the east of Amiens until the end of October, after which it trained for two weeks at Revelles, just to the south-west of Amiens. It then made its way by train to Marseilles (16–18 November), where, on 19 November 1915, it embarked for the Macedonian Front in northern Greece via Alexandria, Egypt, in the 9,000-ton troop ship the SS Huntsgreen, which the British had captured from the Germans at Port Said in 1914 (see also T.H. Helme).

Excursus on the war in northern Greece

While waiting for a train on a draughty station in northern France on a cold winter’s day in 1915, many a British soldier must have welcomed the prospect of going somewhere further south and reputedly warmer. But many must also have asked themselves why on earth they were being sent to northern Greece. And because the Macedonian campaign has received so little public discussion, it is useful, at this juncture, to intersperse the narrative with a brief explanation of the tangled historical events that led up to the decision to send Maclachlan’s Battalion and the 27th Division to the Salonika front.

From the very beginning of the war, the western Allies, who were pro-Serbian and had effectively controlled the shape of the Balkans since supervising the Treaty of London (30 May 1913), were concerned to prevent Bulgaria from renewing its hostilities with Serbia in the hope of making territorial gains. But by September 1915 it seemed to them that the only way of doing this was to put on a show of force by landing an Anglo-French Expeditionary Force at a conveniently located deep-water port in the northern Mediterranean. Unfortunately, the only town that fitted such a purpose was Salonika (Thessaloniki), the capital of Greek Macedonia in the north-east of Greece, a country that retained its official neutrality until 30 June 1917. So in September 1915 an Anglo-French Expeditionary Force – which the French called the Armées alliées en Orient – was hastily put together, with the left-leaning French General Maurice Sarrail (1856–1929) as Commander in Chief. He was in charge of the Allied forces in Macedonia from January 1916 to December 1917, when he was relieved of his command by the new French Premier Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929). The Expeditionary Force initially consisted of two depleted units that had been withdrawn from the failing campaign against the Turks on the Gallipoli Peninsula: the 10th (Irish) Division, commanded by General Sir Bryan Mahon (1862–1930) and the French 156th Division. Although it landed at Salonika on 5 October 1915, by this juncture the gesture was of little use since an Austro-German force invaded Serbia on the following day; and eight days later, on 14 October 1915, this latter force was reinforced by Bulgaria’s declaration of war against Serbia.

British Regimental Band playing on the seafront at Salonika (February 1916)

(© Imperial War Museum Q31729)

But Greece’s neutrality, far from testifying to a sense of national unity, disguised a deep political rift, for King Constantine I (1868–1923; King of Greece 1913–17 and 1920–22) was pro-German, having been educated in Germany. He was also married to the Kaiser’s sister, Sophia of Prussia (1870–1932), and was very popular with a large proportion of his subjects because of his success in ending the Second Balkan War with Bulgaria (16 June–18 July 1913) and doubling the size of Greece. But his Prime Minister, the liberal-democratic Eleftherios Venizelos (1864–1932; Prime Minister of Greece 1910–20 and 1928–33), was in favour of entering the war on the side of the Allies and had given his permission via a secret agreement for General Sarrail’s Expeditionary Force to land in Salonika in October 1915 – for which he was dismissed by King Constantine on 5 October.

Nevertheless, by 21 October 1915 French troops were clashing with the Bulgarians in the valley of the River Vardar (River Axion) north-west of Lake Doiran, c.40 miles north-north-west of Salonika, but because the Greek Government was still controlled officially by supporters of King Constantine, General Mahon was unable to move elements of the British 10th Division north-north-westwards from Salonika until 22 October 1915, when he was finally allowed to advance as far as the Greek–Serbian frontier and support the French. But by the end of November 1915 the French were succumbing to pressure from the Bulgarian Second Army that was invading Greece from the east, and so were preparing to withdraw southwards. And by 29 November 1915, extreme weather conditions, sickness left over from the Dardanelles campaign (especially dysentery), poor food, insufficient supplies, thin tropical kit, frostbite and the bleak inhospitableness of the landscape were forcing the British to think about doing likewise. But on 7 December 1915 the Bulgarian Second Army hastened that decision by attacking the British positions along the Kosturino Ridge, about eight miles above the border between Greece and Macedonia, but then in the Kingdom of Serbia, forcing the British to retreat to the Dedili Pass where they were required to hold the road until the French had passed along it towards the railway station at Doiran. The Battle of Kosturino ended on 12 December, with the Allies declaring that they had lost it. By 20 December 1915 all the survivors of the French Expeditionary Force and the British 10th Division had reached Salonika, where they would have learnt that thousands of French reinforcements and four new British Divisions had arrived in Salonika from Marseilles or were on their way from Marseilles to Salonika: the 22nd (arrived October–November 1915), the 26th (arrived November 1915), the 28th (arrived November 1915–January 1916), and the 27th (arrived November 1915), which included Maclachlan’s 3rd Battalion of the KRRC.

Infantry manning part of the 10th (Irish) Division’s line on the Kosturino Ridge, (December 1915)

(© Imperial War Museum Q62996)

During the abortive campaign of October–December 1915 further north, the Greeks had given General Sarrail permission to build a defensive line around Salonika, albeit in bitter winter conditions. This extended from the mouth of the River Vardar (River Axios) c.12 miles along the curving coast west of Salonika, to the fishing village of Skala Stavros on the north-west corner of the Gulf of Rendina, some 30 miles east of Salonika. The line enabled the city to be transformed into one huge military base with all the logistic provisions that were needed to supply a massive and growing army. So much wire was used in its construction that by the time it was finished, in late March 1916, it was known to the troops as “The Birdcage”.

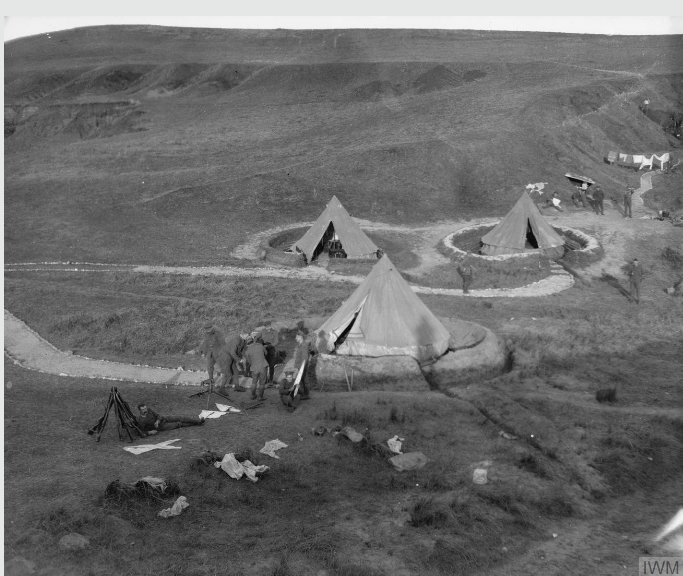

British camp in a valley behind the “Birdcage Line” defences outside Salonika (1916)

(© Imperial War Museum Q31602)

Despite a certain amount of opposition from the British, the French Army, who were more actively pro-Serbian, took advantage of the new defensive line by beginning a fresh advance northwards from Salonika on 26 March 1916. On 24 April, thanks to political pressure from the French government, General Mahon heard that his Expeditionary Force could advance as far as but not cross the border separating Greece and Serbia. Then, in the early summer of 1916, British military perspectives were enlarged and encouraged somewhat by the arrival of a reconstituted Serbian Army numbering c.140,000 men, by the disembarkation of two Russian infantry brigades on 1 May, by the arrival in July of the 35th Italian Infantry Division, and by Rumania’s formal declaration of war against Austria-Hungary on 17 August 1916, with an Army of c.400,000 men at her disposal. Moreover, on 16 August 1916 Venizelos’s public announcement of his total dissatisfaction with King Constantine’s policy of pro-German neutrality not only worsened the political rift within the Greek population, but triggered a coup d’état on 30 August by Venizelist officers in Salonika. This enabled Venizelos to leave Athens with 20,000 Greek troops and move to Salonika – where he arrived on 9 October 1916 and set up a rival (Provisional Revolutionary) Government.

So by about late July 1916, British troops, who had been allotted their own sector in Macedonia back in mid–late May 1916 at the request of their new Commander in Chief, Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir George Milne (1866–1948; later the 1st Baron Milne), were establishing a new front line in the valley of the River Struma (Strymó). This rises in the neighbourhood of Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria, flows southwards for c.260 miles, and meets the Aegean Sea about 50 miles north-east of Salonika and c.30 miles south-west of the Greek city of Kávala. But on about 11 and 17 August two Bulgarian armies – the First Army on the right flank and the Second Army on the left flank – invaded northern Greece in a grand pincer movement against the Armées alliées en Orient. So once again, British troops were involved in the aggressive defence of such key objectives as “Horseshoe Hill” (20 August) – nominally in order to keep the War Office happy, as a gesture of assistance to the five French Divisions. But after the First Bulgarian Army was halted on 22 August and both the Bulgarian Armies had been ordered to dig in on 27 August, the fighting died down along the front, giving General Sarrail the time that he needed to change his strategy on the grounds that although the valley of the River Vardar (River Axion) was the most obvious route northwards, it was too heavily defended. Consequently, he made the recapture of the ancient town of Monastir (now Bitola), which had been taken by the Bulgarians on 21 November 1915, his most central and immediate objective on the grounds that this Serbian town in the south-west corner of Macedonia had been an important east–west and north–south crossroads for many centuries. Sarrail’s campaign began on 12 September 1916 and proved very costly, causing both sides a final joint total of c.50,000 battle casualties. At first it achieved very little, mainly because the Bulgarian positions were well-prepared and well-defended, so that Monastir did not fall until 19 November 1916. This proved to be the limit of the French advance northwards. By this time winter had set in, making further fighting impossible in such a harsh and inhospitable terrain, and on 11 December Marshal Joseph Joffre (1852–1931) ordered Sarrail to call off the offensive. The British role in this campaign was largely auxiliary: they were to render assistance to the French by pinning down as many enemy units as possible in the Struma Valley and around Doiran and so prevent them becoming involved in the Schwerpunkt of the fighting further west – which brings us back to Maclachlan’s Battalion en route to Egypt in November 1915.

The 3rd Battalion of the KRRC reached Alexandria on 25 November 1915, left for Salonika on 1 December, and disembarked there on 4 December to reinforce the Franco-British Expeditionary Force, which had begun to arrive there two months previously – albeit too late to help Serbia in any real sense against the Central Powers. After a few days near Salonika, the Brigade set off northwards and reached Lembet Camp, a few miles north of Salonika, on 12 December and Balza on 15 December, with ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies of the 3rd Battalion, the KRRC, now commanded by Maclachlan, providing the Brigade rearguard. It stayed in roughly this area until 9 January, when it took over the camp that was occupied by the 1st Battalion of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders near Harmankoy, on the east–west road to Monastir (Bitola).

Although there were heavy falls of snow between 15 and 18 January 1916, it must have been about then that the Brigade was ordered eastwards across the neck of the Chalkidiki Peninsula and into the defensive position known as “The Birdcage Line”, since the War Diary of Maclachlan’s Battalion mentions Gomonic (21 January), which is between Lakes Longaza (Koroneía) and Beshik (Volpí), and Pazarkia (22 January), which is on the shore of Lake Beshik. By 23 January, the Battalion had arrived near a monastery with the very common name of Aghia Maria and which is probably identical with the place referred to in the War Diary as Aja Maria, and here it took over trenches and dug-outs that were extremely hard to keep in good repair because of the biting wind, which made work difficult, and the heavy rain, which caused flooding and the collapse of parapets, just as on the Western Front. So in common with the other British battalions that had landed at Salonika over the previous months, Maclachlan’s Battalion spent the next few months throwing up defensive positions to the east of Salonika in order to protect it against what was feared to be an imminent Bulgarian attack from the north-east, with four days a week being spent on maintaining and improving the defences, and three on training. This situation continued unchanged until 8 May, when the Battalion, now just 483 strong, acted as the advance guard during divisional manoeuvres and marched to a point half a mile south of Maslar, a village that is a few miles inland from the western shore of the Strymonian Gulf (also known as the Gulf of Rendina and the Gulf of Orphanou). The Battalion continued to train for three days a week within the “Birdcage” throughout May, June and most of July, while other elements of the Allied forces began to move westwards out of the “Birdcage Line” and towards Lake Doiran, and the Bulgarians, advancing from the north-east, began to threaten the Struma Valley.

Throughout this time, Maclachlan’s Battalion, like the rest of the 27th Division, appears to have seen very little action, having been left in the “Birdcage” as a defensive reserve. But on 25 July 1916 it advanced eastwards to Aspravalta on the Strymonian Gulf, stayed there for four days, and then advanced 20–30 miles north-eastwards towards a position on the River Struma (Strymon), which flows southwards from near Sofia, Bulgaria, into the northern end of the Strymonian Gulf. The Battalion then created a bridgehead near Chaiagazi, where it stayed for three weeks working on defences under the direction of the Royal Engineers. But on 20 August 1916, news arrived that the Bulgarians were advancing from the north-east towards the strategic railway towns of Demirhisar and Seres (Serrai), and the Battalion was ordered to destroy various railway bridges across the River Angista, a tributary of the Struma that flows into it south-westwards from Drama.

So at 03.15 hours on 22 August the Battalion advanced to Zdravik (Dravisokos), between the towns of Angista and Seres, in order “to cooperate with a small mobile column under Major A.F.C. Maclachlan D.S.O. who had orders to go out at 3 a.m. to destroy certain bridges over the Angista River”. Maclachlan’s party occupied Zdravik at 07.00 hours and was joined by the rest of the Battalion at 07.50 hours, and at 09.30 hours the mobile column moved forward to set fire to two bridges (one at Kucuk and the one just west of it). But at about the same time a Bulgarian column was seen marching towards the River Angista through Rahovo village, and the mobile column at the two bridges suffered two casualties when it was fired on by machine-guns and infantry. But by 13.30 hours the bridges were destroyed and in order to avoid the Bulgarians the mobile column set off westwards with the intention of destroying the bridge at Pasa Kaprusi. When, at 15.45 hours, skirmishing lines of Bulgarians were seen advancing onto the ridge above Zdravik, the Allied artillery fired on them and the column withdrew to its defensive lines at the Chaiaghizi bridgehead lower down the River Struma.

Here nothing happened until 4 September, when Bulgarian artillery was close enough to shell the Allied trenches. But at 18.15 hours on 10 September, two Companies of Maclachlan’s Battalion went through the wire and advanced on what was known as Fig Tree Plateau; the Bulgarian artillery fired back and a Royal Navy Ship, probably the Monitor HMS Sir Thomas Picton, retaliated from the Strymonian Gulf. At 19.15 hours the two Companies advanced on the hill above the ruins at Amphipolis, which stand on a raised plateau overlooking the River Strymon at the point, a mere three miles from the sea, where the river emerges from Lake Cercinitis, and headed towards the enemy positions on Mount Dranli. But at 21.15 hours they withdrew to the Chaiaghizi bridgehead without making contact with the enemy.

Between 12 September and 4 October 1916, a period when, starting on 30 September, the British were opening a front against the Bulgarians further up the River Struma near Seres, Lieutenant-Colonel Long took temporary command of 80th Brigade and Maclachlan replaced him as the temporary CO of the 3rd Battalion. On 5 October the Battalion took part in an exercise around Neohori Bridge and a feature known as Tafel Kop, but throughout the month of October reconnoitring patrols made no contact with the Bulgarians, who, it was thought, seemed to have relinquished their positions to the Turks. Then, at 16.00 hours on 31 October 1916, three Companies of Maclachlan’s Battalion, supported by three Companies of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI) and four Vickers machine-guns, raided the enemy trenches in the vicinity of the Amphipolis ruins. Two of these got within 200–300 yards of the enemy trenches on the “Hog’s Back”, incurring slight casualties as they did so. But no significant gains were made during what was to be Maclachlan’s last action with the 3rd Battalion before he was appointed CO of the 13th (Service) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment on 10 November 1916, which was then quartered near Lake Doiran, a hundred miles due west.

The 13th Battalion had arrived in Macedonia as part of 66th Brigade in the 22nd Division a week or so earlier than Maclachlan’s KRRC Battalion, and when he arrived to take command of it on 17 November 1916 it was in the front-line trenches at Reselli, which is near the Selimli Ravine and about 12 miles south-west of the southern tip of Lake Doiran, a large natural feature about 40 miles due north of Salonika and just over the border from Greece in what is now Macedonia. The weather was becoming increasingly harsh and wet; the shelling by the Bulgarians was at times continuous; and both dysentery and malaria were recurrent problems for the Allied troops. The 13th Battalion suffered a steady trickle of casualties but alternated periods in the front-line trenches with recurrent periods of rest and training in Ardzan and Mihalova to the south until 18 March 1917. It then marched eastwards to Gugunci (Cugunci) and thence ten or so miles northwards to the front at the ruined village of Doldzeli.

When it arrived here on 20 March 1917, it occupied defensive positions on the high points to the west of the town that were known as “Kidney Hill”, “Whale Back”, “Pillar Hill” and “Horseshoe Hill” until it was relieved on 31 March and retired to Gugunci for two weeks of training. When the 13th Battalion returned to the Doldzeli sector of the front on 16 April 1917, it had been allotted its assigned place in the preparations for the Allied Spring Offensive across the whole of the Macedonian Front. General Sarrail now envisaged a three-Division assault in the British Sector that would punch a three-mile-wide hole in the Bulgarian front line, enable the capture of the strategic lakeside town of Doiran that guarded the entry to the Kosturino Pass, and then swing round eastwards towards Seres in the Struma Valley, a good 50 miles away over very poor roads. The plan was ambitious, required far more men and supply than were available, and was doomed to failure from the outset. Maclachlan’s Battalion took up position opposite the southern end of “Pip Ridge”, a narrow ridge only 50 yards wide which consisted of six peaks, each furnished with a defensive redoubt and which rose to a height of 2,000 feet. But the Bulgarians were well dug in, in an area of broken territory that was ideal for defence and covered with barbed wire entanglements, and although the assault was preceded by a barrage of 100,000 shells that was intended to destroy the wire, the Bulgarian forces, which included the crack 9th (Pleven) Division, repulsed their attackers with ease, causing total casualties of 3,163 men killed, wounded and missing out of an attacking force of over 43,000. Although Maclachlan’s Battalion acquitted itself relatively well, it made no real gains, and by the time it was relieved during the night of 27/28 April 1917, it had lost six officers and 222 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing.

The Second Battle of Lake Doiran began with an artillery barrage on 6 May 1917 and ended in another failure which, after an unsuccessful series of attacks during the night of 8/9 May, had cost the British 1,891 casualties killed, wounded and missing. But Maclachlan’s 13th Battalion does not seem to have taken part in the Second Battle, for after resting on 29 April, it withdrew southwards to the town of Gugunci on 30 April 1917, and Maclachlan, who had been wounded on 1 May, did not rejoin the Battalion until 28 May. During the intervening period the Battalion had moved back to “Shelter Ridge Ravine”, near the Dolzeli battlefield, where it was distributed over “Horseshoe Hill”, “Kidney Hill”, the “Roach Back”, the Ravine and the northern edge of “Jackson’s Ravine”. Here, it helped to consolidate the new forward line before relieving the 8th Battalion of the KSLI on 20 May 1917 in front of the village of Krastali. On 3 June 1917 Maclachlan’s Battalion withdrew southwards in Corps Reserve to Bicot Dere, and four days later it marched to the village of Rates, ten miles south of Lake Doiran, where it trained until 24 June before spending a week at Saida Camp in Brigade Reserve.

Then, on 2 July, it took up position in the ‘F’ Sector trenches, in front of Krastali, which extended from the “Whale Back” on the right to “Bowls Barrow” on the left and beyond that to the strongpoint known as “The Tomato” which was “to be held to the end”. Because of the difficulty of digging in the rocky ground, these trenches were often shallow and, as a result, excessively exposed to shellfire. On 11 July the Battalion moved back to train at Saida Camp, and on 21 July it returned to the front, this time to ‘E’ Sector of the front near “Horseshoe Hill”, where the situation was relatively quiet. On 30 July the Battalion moved back to camp at Point 323, where it trained and did anti-malarial work on the marshy ground until 2 September. But on 11 August 1917, Maclachlan, whose health had already been affected by the Macedonian climate, was sent on leave to England and did not return until 24 October 1917. He lasted about a month, but his health did not improve and on 26 November he was struck off the Battalion strength with effect from 11 November 1917 and sent back to England.

While recuperating in England, Maclachlan was appointed Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel and awarded a Bar to his DSO on 1 January 1918 (London Gazette, no. 30,450, 28 December 1917, p. 17); on 28 January 1918 he was awarded the Serbian Order of Karageorge (4th Class; with swords). In early 1918 he was offered the choice of going to France or returning to the Salonika front, and when he chose the former option, he was given command of the 12th (Service) Battalion, The Rifle Brigade, part of 60th Brigade in the 20th Division, which he joined when it was in billets and training at Moyencourt, 20 miles south-west of St-Quentin. By 21 March 1918, the first day of Operation Michael, the Battalion had moved north-eastwards to battle stations at Fluquières, five miles south-west of St-Quentin, where it was subject to a heavy artillery barrage that killed or wounded three officers and 30 ORs. At about 15.50 hours on 22 March 1918 the Germans attacked in force, causing the Battalion’s left and right flanks to pull back and the encirclement of two Companies. While Machlachlan, accompanied only by an orderly, was inspecting these Companies’ positions just as they were about to retire, he was killed in action by a machine-gun bullet, aged 56. The Battalion then withdrew to Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes, making a stand at Mill Wood en route, and fought a strong rearguard action at Ham, two miles further on, before crossing the Canal de la Somme and digging in on the opposite canal bank to the right of nearby Voyennes. At first it was impossible to bring in Maclachlan’s body because of the enemy’s rapid advance, but he is now buried in Savy British Cemetery, Grave I.G.13.

Maclachlan was mentioned in dispatches four times during World War One: in France in 1915 and 1916, and Salonika in 1917 (London Gazette, no. 29,422, 31 December 1915, pp. 14 and 50; LG, no. 30,404, 27 November 1917, pp. 12 and 484). He is commemorated on the Eton War Memorial and, together with Neil and Ronald, who also died on active service, on a memorial tablet and two windows that their surviving brother and three sisters installed in 1919 in St Mary the Blessed Virgin Church, Newton Valance “in Honour of the Warrior Saints George & Martin”. Maclachlan left £3,711 16s.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Neil Campbell, Napoleon at Fontainebleau and Elba; Being a Journal of Occurrences in 1814–1815. […] With a Memoir of the Life and Services of that Officer [Campbell] by his nephew Archibald Neil Campbell Maclachlan (London 1869). Also available on-line at: http://dbooks.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/books/PDFs/600017590.pdf.

[Anon.], ‘Trial of Maclean for High Treason’, The Morning Post (London), no. 34,265 (20 April 1882), p. 6.

Our Military Correspondent, ‘The Mohmand Campaign’, The Times, no. 38,661 (1 June 1908), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Brigadier-General R.C. Maclachlan’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,558 (16 August 1917), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Fraser Campbell Maclachlan, DSO’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,751 (30 March 1918), p. 7.

[Anon.],‘Lieut.-Colonel Alexander Fraser Campbell Machlachlan, DSO’ [obituary], KRRC Chronicle (1918), pp. 332–3.

Edward Peel, Cheam School from 1645 (Gloucester: The Thornhill Press, 1974), passim.

H.M. Stephens revised by Stewart M. Fraser, ‘Sir Neil Campbell 1776–1827’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2004).

Wakefield and Moody (2011), pp. 36, 64–98.

Churchill (2014), pp. 131–6.

Archival sources:

The Greenjackets Museum, Winchester; photo courtesy of Major Ken Gray.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/834-839 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to A. and R. Maclachlan [1914–1915]).

OUA: UR 2/1/24.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1162.

WO95/1358.

WO95/1895.

WO95/2121.

WO95/2261.

WO95/4855.

WO95/4889.

On-line sources:

British Battles.com, ‘The Siege and Relief of Chitral’: https://www.britishbattles.com/north-west-frontier-of-india/siege-and-relief-of-chitral/ (accessed 9 June 2018).

‘Battle of Kosturino’, Wikipedia article on-line: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Kosturino (accessed 27 May 2018).

‘Battle of Monastir (1917)’, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Monastir_(1917) (accessed 9 June 2018).

‘Eleftherios Venizelos’, Wikipedia article on-line: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleftherios_Venizelos (accessed 27 May 2018).

‘Monastir Offensive’, Wikipedia article on-line: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monastir_Offensive (accessed 27 May 2018).