Fact file:

Matriculated: 1896

Born: 26 April 1877

Died: 29 October 1916

Regiment: Royal Garrison Artillery

Grave/Memorial: All Saints’ Churchyard, Botley, Hampshire

Family background

b. 26 April 1877 as the elder son (two boys and a girl) of Captain (RN) (later Admiral) Charles John Rowley (1832–1919) and Alice Mary Arabella Rowley (née Cary Elwes) (1846–1931) (m. 1867). At the time of the 1891 Census the family lived at “Holmesland”, Botley, just north-east of Southampton, Hampshire, with a governess and seven servants living in; in 1901 and 1911 the family was living at the same address with seven and six servants respectively.

Parents and antecedents

The Rowley family originated in Staffordshire and began its rise to prominence as a naval family in 1704, when William Rowley (later Admiral Sir; c.1690–1768), the great-great-great-grandfather of Charles Pelham Rowley, volunteered for service in the Royal Navy during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14). He was then assigned to the 70-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Orford (1698–1745; wrecked on 13 February 1745 in the Windward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola but with no loss of life). During the war William Rowley saw action in the Mediterranean, and shortly after passing his Lieutenant’s exams on 15 September 1708, he was transferred to the 80-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Somerset (1698–1740; broken up). In early 1716 he performed various diplomatic tasks for George I (1660–1727; reigned 1714–27), and was then promoted Captain (RN) and given command of the 20-gun sixth rate ship of the line HMS Bideford (1711–36; foundered) that was based at Gibraltar. In September 1719, William Rowley’s command was transferred to the 20-gun sixth rate ship of the line HMS Lively (1713–38; broken up and rebuilt) which he held until 1728, when he was “beached” (i.e. taken off active service and put on half-pay) for 13 years. In 1741 he was recalled to the Navy and given command of the 90-gun second rate ship of the line HMS Barfleur (1697–1783; broken up) to fight in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48). On 7 December 1743 he was promoted Rear-Admiral and just over two months later, on 22–23 February 1744, he distinguished himself as Commander of the Van[guard] in the Battle of Toulon. Although the British were fighting a smaller Franco-Spanish fleet, they lost the Battle, as a result of which 12 senior officers were court-martialled and seven cashiered. In contrast, William Rowley’s aggressive seamanship established his reputation and he was promoted Vice-Admiral on 23 June 1744, became Commander-in-Chief (C-i-C) of British naval forces in the Mediterranean, and was promoted Full Admiral on 15 July 1747. But after making a bad judgement when acting as Chairman of a court-martial board, he retired from the Navy in 1746 and went into politics, becoming the Whig MP for Taunton, Devon (1750–54), and for Portsmouth, Hampshire (1754–61). Nevertheless, he also served on the Board of the Admiralty during this period (1751–57) and was finally promoted Admiral of the Fleet on 17 December 1762.

In about 1728, Sir William Rowley married Arabella Dawson (1694–1784) and they had one daughter and five sons. Their second son, Joshua Rowley (b. 1734 in Dublin, d. 1790), also entered the Royal Navy as a volunteer and worked his way up to become the family’s most distinguished Flag Officer; while the fourth, another William Rowley (dates unknown) became a Major-General.

Joshua Rowley (1734–90), the great-great-grandfather of Charles Pelham Rowley, first served on HMS Stirling Castle (1742–62; stripped and scuttled in Havana harbour, Cuba), a 70-gun third rate ship of the line that was his father’s flag ship. He was promoted Lieutenant (RN) on 2 July 1747 and in 1752 became an officer on the 44-gun fifth rate frigate HMS Penzance (1747; no further details available). On 4 December 1753 he was promoted Post Captain and given command of the 24-gun sixth rate ship of the line HMS Rye (1745; sold 1763). By March 1755 he was commanding the HMS Ambuscade (1745–62; sold to privateers), a 40-gun fifth rate frigate that had been captured from the French in 1746, i.e. during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48), and attached to the 14-ship squadron under Admiral Edward Hawke (1705–81; later Admiral of the Fleet and the 1st Baron Hawke of Towton, Yorkshire) that was active in the Bay of Biscay and succeeded, in a short period of time, in capturing 300 enemy merchantmen.

Sir Joshua Rowley (1734–90) painted by the fashionable English portraitist George Romney (1734–1802)

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

By 1756, when the Seven Years’ War broke out between Britain and France in North America as well as in Europe (ended 1763), Joshua had become captain of the 50-gun fourth rate ship of the line HMS Hampshire (1744–66; broken up), and by October 1757 he was responsible for commissioning the 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line HMS Montague (no details available). On completion, the Montague joined the Mediterranean fleet of 14 ships of the line that was commanded by Admiral of the Blue (the third highest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-tier hierarchy of admirals) Henry Osborn (1694–1771) and operated out of Gibraltar. Since November 1757 Osborn’s fleet had been blockading Cartagena, an important port on the south-east coast of neutral Spain. During this period, bad weather in the Atlantic forced a fleet of 15 French ships, commanded by Admiral Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran (1696–1764), the C-in-C of the French Mediterranean fleet, to break off its voyage from Brest to North America in order to reinforce the French forces there, and take refuge in the Spanish port, where they were blockaded. Early in 1758, the French sent a squadron of five more ships, commanded by Admiral Duquesne de Menneville (1700–78), westwards from their naval base in Toulon to assist the blockaded vessels. Two managed to enter the port, but when, on 28 February 1758, the other three tried to escape and head for America, they were intercepted or captured, with the Montague and its sister ship, the 74-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Monarch (1747–60; broken up) managing to drive the 60-gun Oriflamme ashore (1743–70; wrecked off the coast of Chile under mysterious circumstances). The blockade and subsequent battle had two long-term effects: they significantly weakened the French forces in Canada and thereby contributed to the successful British siege of the key French stronghold of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, from 8 June to 26 July 1758, and they hastened the capture of Quebec on 13 September 1759, an event which brought the Anglo-French war in Canada to a close.

In 1758, while the Seven Years’ War was still on, Joshua Rowley and the Montague joined the huge Channel Fleet that was commanded by Admiral George Anson (1697–1762; 1st Baron Anson of Soberton from 1747), who oversaw the Royal Navy throughout the war and was responsible, inter alia, for devising the system of rating ships according to their size and the number of their guns. The fleet was divided into two squadrons: one, commanded by Anson himself, consisted of 22 ships of the line and nine frigates, and the other, commanded by Commodore Richard Howe (1726–99; 1st Earl Howe from 1788), consisted of five ships of the line, ten frigates, and nine smaller ships that were designed to facilitate or support the landing of troops. In September 1758 the fleet, accompanied by a force of c.10,000 soldiers, attacked the Brittany coast, and although it captured Cherbourg and destroyed the port, docks and town, it failed to take St-Malo, some 70 miles away by sea. So it was decided to send the soldiers on foot westwards along the coast and re-embark them near the coastal village of St-Cast-Le-Guido. But when they were near this point, the British force was unexpectedly attacked by three French brigades under the command of the Marquis d’Aubigné and supported by artillery, and lost 3,000 men killed and captured. Commodore Howe was taken prisoner on the beach near St-Cast while supervising the evacuation of the British troops, and Joshua Rowley, who had been wounded, was left on the beach together with three other captains (RN), and also taken prisoner. The defeat at St-Cast marked the end of the British attempt to take Brittany. By October 1759 Joshua had been exchanged for French prisoners and returned to the Montague as part of a squadron that was once again commanded by Admiral Hawke. Hawke was centrally concerned with preventing the French from invading Britain, and on 20 November 1759 Hawke’s fleet of 25 ships of the line and five frigates decisively defeated the French fleet of 21 ships of the line and six frigates, commanded by Maréchal de Conflans (1690–1777). The Battle of Quiberon Bay, which was fought just south of the port of Brest and off the mouth of the River Vilaine, has been called the “Trafalgar” of the Seven Years’ War. It destroyed French hopes of invading Britain and marked the beginning of British naval ascendancy, which would last until 1914 at least.

In 1760 Joshua Rowley was in the Caribbean, where he took part in the expedition against Dominica of 7 June, and in November of the same year he was transferred to the 74-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Superb (1760–83; wrecked in Tellicherry Roads off the Bombay Coast) and spent his time protecting convoys that belonged to the East India Company. He performed this task with so much success that the Company and the London West India merchants made him a valuable presentation in silver. In c.1762, not long before the end of the Seven Years’ War, Joshua was “beached” until, in October 1776, he was made captain of HMS Monarch (1765–1813; broken up), a 74-gun third rate ship of the line, not to be confused, however, with the ship of the same name with which the Montague had worked at the Battle of Toulon 30 years previously. In early 1778 Joshua conducted transports to Gibraltar. On 27 July 1778 he took part in the first naval battle between the British and the French during the American War of Independence (1775–83), the inconclusive Battle of Ushant. Although this led to the court-martial of Admiral Augustus Keppel (1725–86), the C-i-C of the British Fleet, he was acquitted, later ennobled as the 1st Viscount Keppel of Elveden, Suffolk (1782), and became the First Lord of the Admiralty (1782–83).

At the end of 1778, Joshua was made captain of HMS Suffolk (1765–1803; sold), a 74-gun third rate ship of the line, with the temporary rank of Commodore, and put in charge of a squadron of seven ships which he took out to the Caribbean. On 19 March 1779 he was made a Rear-Admiral of the Blue (the lowest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-tier hierarchy of admirals), and on 6 July 1779 he led the Vanguard against the French during the Battle of Grenada and Guadeloupe. On 21/22 December of the same year he set three of his frigates against three French frigates, captured them with ease, and brought them back to Britain for incorporation in the Royal Navy; he then captured an entire French convoy from Marseilles off Martinique. By 17 April 1780, the date of the Battle of Martinique, he had been transferred to the 74-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Conqueror (1773–94; broken up), and was commanding the rear division of the British Fleet that was commanded by Admiral Sir Brydges Rodney (1718–98; 1st Baron Rodney of Rodney Stoke, Somerset from1782). Rodney then sent Joshua with ten ships of the line to Jamaica as reinforcements for Admiral of the Fleet Sir Peter Parker (1721–1811; 1st Baronet from 1782), who had been the C-in-C of Jamaica from 1777 to 1779. Joshua Rowley occupied the same post from 1781 to 1783 – i.e. during the period when Prince William Henry, the future King William IV (1765–1837; reigned 1830–37), who had joined the Royal Navy as a Midshipman on 15 June 1779, made a brief visit to the Caribbean. After Joshua’s return to Britain, he was not appointed to another command, but on 19 June 1786 he was made the 1st Baronet of Tendring, the Suffolk village where he lived in the family home, and on 24 September 1787 he was promoted Vice-Admiral of the White (the fifth highest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-tier hierarchy of admirals). Although a competent and well-respected naval officer who took part in many battles, his reputation has been eclipsed by those of men like Keppel, Rodney, and Hawke.

In 1759, Joshua Rowley married Sarah Burton (1739–1812), the daughter of Bartholomew Burton (c.1695–1770), the Deputy Governor of the Bank of England (1758–60) and subsequently the Bank’s Governor (1760–62). They had four sons and three daughters, the second of whom, Philadelphia Rowley (c.1763–1855), married Post Captain Sir Charles Cotton (1758–1812; the 5th Baronet of Landwade, Cambridgeshire) in 1798. He was made an Admiral in 1808 and later became the C-i-C of the Channel Fleet; two of her younger brothers also had distinguished careers in the Royal Navy, Bartholomew Samuel and Charles.

Bartholomew Samuel Rowley (1764–1811), the second son of Joshua and Sarah Rowley, achieved the rank of Post Captain on 31 January 1781 – i.e. before his seventeenth birthday – and was given command of the 28-gun sixth rate frigate HMS Resource (1778–1816; broken up), which, on 20 April 1781, captured the 20-gun French frigate Licorne. In October 1782 his command was transferred to the 32-gun fifth rate frigate HMS Diamond (1770–84; sold) which participated in the American War of Independence until it ended in September 1783. Bartholomew was then “beached” for nearly a decade until, by the outbreak of the French Revolutionary War (20 April 1792–25 March 1802 and 18 May 1803–15), he was back at sea as the captain of the 32-gun fifth rate frigate HMS Penelope (1783–97; broken up) and serving in the Jamaican Squadron. On 16 April 1793 he captured the French frigate Le Goéland and in late 1793 he took advantage of the revolutionary slave uprising on Santo Domingo (now Haiti) (1791–1804) to occupy several French ports there. On 25 November 1793 the Penelope took part in the capture of the 36-gun French frigate L’Inconstante and on 4 June 1794 in the capture of Port-au-Prince, the island’s capital. In August 1794 Bartholomew Rowley was made captain of the 74-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Cumberland (1774–1804; broken up), and it was he who captained her when she participated with some distinction as leader of the van[guard] during the Battle of the Hyères Islands, off the French Mediterranean coast, on 13 July 1795. During the final phase of the battle, Rowley forced the Alcide (1782–95), a French 74-gun ship of the line, to surrender, but she caught fire before she changed hands and blew up, killing 300 members of her complement. From July 1797 to October 1798 he commanded the 74-gun third rate ship of the line HMS Ramilles (1785–1850; broken up). He was promoted Rear-Admiral in 1799 and Vice-Admiral in 1805, made C-in-C of the Jamaica Station from 1808 to 1811, and finally promoted Admiral of the Blue (the third highest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-tier hierarchy of admirals) on 31 July 1810.

Charles Rowley (1770–1845; 1st Baronet of Hill House, Berkshire, from 1836), the great-grandfather of Charles Pelham Rowley, joined the Royal Navy in 1785 and served with Prince William Henry on the North American Station and in the Caribbean – a connection that would stand him in good stead during the last 20 years of his life. During the French Revolutionary War, he commanded four smaller vessels between 1794 and 1796 before being given command of three successive ships of the line between 1800 and 1815 (when he was promoted Vice-Admiral and became C-i-C of the Nore until 1818). In 1809, while captain of the newly commissioned HMS Eagle (1804–1926; accidentally destroyed by fire), a 74-gun third rate ship of the line, he took part in the abortive Walcheren Expedition (July–December 1809), when the British invaded Holland with a force of c.40,000 soldiers and 15,000 horses plus field artillery and two siege trains and then tried, unsuccessfully, to seal off the mouth of the River Scheldt, blockade the port of Antwerp, and destroy the French Fleet. But in the process the invading force lost 4,000 men to malarial fever and only 100 men in action.

Sir Charles Rowley (1770–1845) (1st Baronet) painted by the Scottish portraitist George Sanders (1774–1846)

© National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth

In 1810, Charles Rowley cooperated in the defence of Cadiz, a major port on the coast of south-west Spain. But in the summer of 1813, as the captain of HMS Bacchante (1811–58; broken up), a 38-gun fifth rate frigate, he “signalized himself in a remarkable manner” during the capture of Fiume (now Rijeka), a major port in the north-eastern Adriatic in territory that is now mainly Croatian but was, from 1809 to 1813, occupied by the French and styled as their Illyrian Provinces. The Bacchante formed the crew of one of a fleet of five British ships, commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Francis Fremantle (1765–1819), a protégé of Lord Nelson, that attacked the port of Fiume on 3 July 1813 and destroyed the 15 shore-based heavy guns which protected the port to seaward. Charles Rowley’s crew then took the adjoining fort, and having silenced it, dashed into the town of Fiume at the head of a party of marines where, at almost no cost in casualties, they captured most of its French garrison together with many stores and supplies. They then helped to reduce the castle of Farasina and destroy the batteries at Rovigno (now Rovinj), both on the Illyrian coast and now in Croatia, and finally assisted in the capture of the nearby port of Trieste, thus enabling it to be returned to the Austrian Empire. From 1820 to 1823 Charles Rowley commanded the Jamaica Station with the rank of Rear-Admiral and in 1825 he was promoted Vice-Admiral. He then served in a senior position in the Royal Household until Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne in 1837, and held the post of Third Naval Lord from 1834 to 1835. In 1841 he was made Full Admiral of the White (the second highest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-stage hierarchy of admirals) and in 1842 he was made C-in-C of Portsmouth, a post that he held until his death. In 1797 Charles Rowley had married Elizabeth King (d. 1838), the daughter of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Richard King (1730–1806; 1st Baronet of Bellevue, Kent, from 1892), a very beautiful woman who, like many another beautiful woman, was “associated with King William IV”.

Two of Charles and Elizabeth’s five sons served in the Royal Navy: Richard Freeman (their fourth son), and Robert Hibbert Bartholomew (their fifth and youngest son).

Richard Freeman Rowley (1806–54; Charles Pelham Rowley’s grandfather) entered the Royal Navy in February 1819, served as Midshipman aboard the HMS Medina (no details available) and the HMS Euryalus, a 42-gun frigate (1803–60; broken up), and was promoted Lieutenant (RN) in 1825. On 8 May 1827 he was promoted Commander, a rank that had been established in April 1815, and then served for nearly two years as the Flag-Lieutenant of Admiral Sir George Martin (1764–1847; Admiral of the Fleet from 9 November 1846), who had been C-i-C of Portsmouth from 27 March 1824 to 30 April 1827. Admiral Martin was the grandson of Admiral Sir William Rowley (see above) and flew his flag from HMS Victory (1765 to the present day), the 104-gun first rate ship of the line that had been Nelson’s flag-ship at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. On 26 February 1830 Richard Freeman Rowley was promoted Captain (RN) and given the command of HMS Badger (1808–64; broken up), a 10-gun brigantine sloop on which he served on the Plymouth, North Sea and Cape of Good Hope stations and in the Mediterranean from 1835 to 1838. On 31 December 1842 Richard Freeman Rowley was made Flag-Captain to his father, Admiral Charles Rowley, aboard the HMS St Vincent (1815–1906; sold for breaking up), a 120-gun first rate ship of the line that had been on harbour service in Portsmouth Dockyard since 1841. He was finally “beached” in September 1845.

Robert Hibbert Bartholomew Rowley (b. 1817, d. 1860 in Montevideo, Uruguay; Charles Pelham Rowley’s great-uncle) entered the Royal Navy in c. 1830, was commissioned Lieutenant (RN) on 1 June 1837 and served until spring 1841 on HMS President, a 52-gun frigate (1832-1903; broken up) that was used primarily in the Pacific. On 24 August 1841 he was transferred to the HMS Formidable (1825-1906), an 84-gun second rate ship of the line, and served on her until 7 December 1842. Before being paid off as a Commander (see above) at the end of 1847, he captained the HMS Satellite (1843-47), an 18-gun brigantine sloop that served mainly in the East Indies and along the south-west coast of South America. In 1845 he married Doña Juanita de Solsona, a resident of Montevideo, and died there in 1860 leaving a widow and four chidren.

Charles John Rowley, Charles Pelham Rowley’s father, was born in Brandon, Norfolk, as one of the seven children of Captain (RN) Richard Freeman Rowley (1806–54) and Mrs Elizabeth Julia Rowley (née Angerstein) (1804–70) (m.1828). Elizabeth Julia was the youngest daughter of John Angerstein Esq. of Weeting Hall, Norfolk (1773–1858): Whig MP for Camelford, Cornwall 1796–1802; Liberal MP for Greenwich 1835–37; High Sheriff of Norwich 1831. Her mother was Mrs Amelia Angerstein (née Lock) (1777–1848) (m. 1799). Charles John Rowley joined the Royal Navy in 1844 as a Midshipman when he was about 13 years old, and was promoted Lieutenant (RN) on 21 December 1852 in order to serve as an Additional Lieutenant in Portland, Dorset. For several months in summer 1854 Charles John Rowley served as an officer aboard HMS Hornet (1745–70; sold), a 14-gun sloop, from where, on 18 September 1854, he was transferred to the HMS Curlew, a Swallow-class screw sloop (1854–65; broken up). During the Crimean War (October 1853–February 1856) he served aboard the Curlew in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, where he took part in the operations before Sebastopol (17 October 1854 – 11 September 1855). One of these involved taking control of the Sea of Azof after the arrival of Allied forces there in late May 1855 had compelled the defenders of the Kerch Strait to blow up the fortress of Yeni-Kale in the city of Kerch on the Crimean Peninsula. In recognition of his war service, the Turkish Sultan appointed him to the Imperial Order of the Medjidie (5th Class) in 1858. From 7 March to 10 September 1856 Charles John was a Temporary Lieutenant-Commander on the gunboat HMS Magnet (1856–74; broken up), after which he was “beached” until 30 January 1859 when, a Lieutenant (RN) once more, he began a year’s service in the Mediterranean on HMS St Jean d’Acre (1853–75; broken up), the Royal Navy’s first 101-gun second rate two-decker ship of the line. When, during the 1860s, Britain was not involved in any war, Charles John served on several ships in different parts of the world, but probably spent most of his time at sea on the American Station, in the West and East Indies, and in the Mediterranean. He was promoted Commander (see above under Richard Freeman Rowley) on 9 July 1861 and Captain (RN) on 5 July 1866, and he spent most of the equally uneventful 1870s in the Mediterranean and the West Indies. He was Port Admiral of Portsmouth from 1882 to 1884, a period that coincided with the years when he was also the Naval Aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria. He flew his flag from the HMS Duke of Wellington (1853–1904; broken up), a 131-gun first rate ship of the line that was probably the most powerful warship in the world when she was launched. But after the Crimean War she saw no active service and from 1869 to 1891 she served as the – largely ceremonial – flagship of the Portsmouth Command. Charles John Rowley was promoted Rear-Admiral in 1884, became second-in-command of the Channel Squadron from 1887 to 1888, was promoted Vice-Admiral in 1890 and made up to full Admiral in 1895. He retired on half-pay in London in 1897, where he died in 1919 having “devoted his life to acts of piety and practical benevolence. [… He] was accustomed to visit the poor in his district [… and] whilst in the discharge of these self-imposed duties he was attacked with cholera […].”

At least three other descendants of Admiral of the Fleet Sir William and Lady Arabella Rowley achieved flag rank in the Royal Navy: Josias Rowley, Samuel Campbell Rowley and Joshua Ricketts Rowley.

Sir Josias Rowley (1765–1842; 1st and last Baronet Rowley of the Navy from 1813) was the second son and second child of Clotworthy Rowley (1731–1805; 1st Baron Langford of Summerhill in the County of Meath, Ireland from 1800), a practising barrister. He was also a grandson of Sir William Rowley, the elder brother of Sir Samuel Campbell Rowley (see below), a cousin of Sir Charles Rowley (see above) and a distant cousin of Charles Pelham Rowley. In 1739 Clotworthy Rowley married Letitia Campbell (b. c.1739 in Ireland, d. 1776), and for three months, starting in January 1801, he was the MP of Downpatrick, Meath, c.21 miles south of Belfast and a constituency that existed only from January 1801 to 1885. In March 1801 he was succeeded there as MP by Samuel Campbell Rowley, his son, who held the seat until 17 July 1802.

Josias Rowley joined the Royal Navy in 1778 and served as a Midshipman in the West Indies on HMS Sutton (no information available). He was promoted Lieutenant (RN) in late 1783, Lieutenant Commander in March 1793, and Post Captain on 6 April 1795. After the British seized the Cape Colony from the Dutch between June and August 1795 in order to acquire a key naval base for their war against the French, Josias Rowley was made captain of the 40-gun HMS Braave (1796; no more information available) there, and in 1797 he was transferred to the command of the HMS Impérieuse (c.1788–1858; broken up), a former 38-gun French frigate. In April 1805 he was given command of HMS Raisonnable (1768–1815; broken up), a 64-gun third rate frigate that was named after a French frigate captured in 1758. On 22/23 July 1805 he commanded her at the Battle of Cape Finisterre, which took place off the north-western corner of Spain between a sizeable Franco-Spanish fleet under Admiral de Villeneuve (1763–1806) and a smaller British fleet under Vice-Admiral Robert Calder (1745–1818). Although neither side won the engagement, the survival of a British fleet prevented a French fleet from supporting Napoleon’s intended sea-borne invasion of Britain, for which, since 1803, he had amassed 150,000–200,000 well-trained soldiers – his Armée d’Angleterre – at Boulogne. In December 1804 Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor of France; and on 27 August 1805, in order to counter the threat posed by the new alliance between Austria and Russia, his Armée d’Angleterre, now renamed the Grande Armée, set out from Boulogne on a c.900-mile march east-south-eastwards across Europe. This culminated in the seizure of Vienna on 13 November 1805 and the catastrophic defeat of the Austro-Russian Army at Austerlitz on 2 December 1805. Vice-Admiral Calder was, however, court-martialled and cashiered for his failure to engage the enemy on 23/24 July, when, it was claimed, he might have completely destroyed Napoleon’s fleet.

Josias Rowley was still captain of the Raisonnable when, in April 1806, she sailed westwards across the South Atlantic to take part in the first British occupation of Buenos Aires (27 June–14 August 1806) and the abortive British attempt to take control of Argentina and Uruguay. This began with the Battle of Montevideo (February 1807) and came to an end on 4/5 July 1807 when the invaders’ second attempt to take Buenos Aires failed, costing them very heavy casualties. By the time Josias Rowley got back to southern Africa in 1808, the Cape Colony was firmly in British hands following their victory over the French at the on 8 January 1806, and Rowley was soon made C-i-C of the British squadron that was stationed at the Cape of Good Hope. This important appointment involved him in the complex naval campaign against the French that had been going on at least since the start of the Napoleonic War in May 1803, and lasted until December 1810, when a squadron of British warships under Admiral Sir Albemarle Bertie (1755–1824; 1st Baronet from 1812) arrived in the south-western waters of the Indian Ocean. Throughout the campaign, the neighbouring French colonies of the Île Bonaparte (now Réunion), c.445 miles south-east of Madagascar, and the Île de France (now Mauritius), c.560 miles east-south-east of Madagascar, played a central role. This was because both islands contained highly convenient but heavily defended ports that were available as bases to French captains who wished to capture their share of British merchant ships en route between the Far East and Europe via the Cape. In the course of this campaign, the British suffered their worst naval defeat during the French wars at Grand Port (the major French base on the Île de France) between 20 and 27 August 1810; however, Josias Rowley helped to compensate for this humiliation by playing a major part in the capture of the two islands during the second half of 1810, earning himself the soubriquet of “Sweeper of the Seas”.

After returning to Britain in 1811, Josias Rowley was made captain of HMS America (1810–67), a 74-gun third rate ship of the line, and was sent to the Mediterranean, where he instigated or participated in several actions, including the raid on Livorno (Leghorn) in December 1813. He was promoted Rear-Admiral in 1814 and made C-in-C of the Cork Station in 1818. From July 1821 to June 1826 he served as the Tory MP for Kinsale, County Cork, on the southern coast of Ireland, and was promoted Vice-Admiral in 1825 and made C-in-C of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1833. He never married and left no children. His major naval exploit is commemorated in The Mauritius Command (1977), the fourth of the 20 books by Patrick O’Brian (1914–2000) that are known collectively as the “Aubrey-Maturin” series of novels (1969–2004).

Sir Samuel Campbell Rowley (1774-1846) was the fourth son (fifth child) of Clotworthy Rowley (see above), the younger brother of Sir Josias Rowley (see above) and a grandson of Admiral Sir William Rowley (see above). Samuel Campbell Rowley joined the Royal Navy on 10 March 1789 as a Midshipman on the HMS Blonde (1781–1805; sold), a 32-gun fifth rate ship of the line, and then spent some four years on her serving on the West Indies Station. He was promoted Lieutenant (RN) on 30 January 1794 and transferred to HMS Vengeance (1774–1816; broken up), a 74-gun third rate ship of the line. On 10 April 1795 he was an officer on board the HMS Astraee (1781–1808; wrecked off the coast of Aregada in the British Virgin Islands on 23 March 1808), a 36-gun fifth rate frigate which is best remembered for her part in the action of 25 September 1806. In the course of this, as one of a four-ship squadron commanded by Commodore (later Vice-admiral Sir) Samuel Hood (1762–1814; 1st Baronet from 1809), she helped to capture a four-ship French squadron, including the frigate La Gloire (1803–12), which became part of the Royal Navy as HMS La Gloire.

On 6 April 1799 Samuel Campbell was promoted Lieutenant-Commander and given command of the first HMS Terror (1794–1847; refitted 1813; lost with all hands during the ill-fated attempt of the explorer Sir John Franklin (1786–1847) to force and chart the North-West Passage; wreck discovered in 2014). The first HMS Terror was a 4-gun gun-boat that was converted into a bomb vessel (or bomb ketch), i.e. a small wooden ship with an extra-strong frame and shallow draft, whose main armament consisted not of cannons but of forward-pointing mortars that were the predecessors of modern howitzers, since they could fire projectiles upwards at a high angle so that they fell on well-fortified targets in a steep sine curve. Samuel Campbell commanded the Terror at the First Battle of Copenhagen (2 April 1801), when a British fleet under Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758–1805; 1st Viscount Nelson of the Nile from 22 May 1801) and Admiral Sir Hyde Parker (1739–1807) fought a sea battle against ships – mainly Danish – of the Fleet of the League of Armed Neutrality (1780–83 and 1800–01). The League comprised Russia, Prussia, Denmark and Sweden and was established to defend the member countries against Britain’s practice of stopping neutral vessels in order to search for French contraband – which the British considered a breach of their neutrality. Although the two sides were unevenly matched at Copenhagen and the British failed to find where most of the League’s ships were concealed, British superior seamanship allowed them to do the greater amount of damage and claim the victory. On 29 April 1802 Samuel Campbell Rowley was promoted Post Captain (RN); from 1804 to 1810 he worked for the West Indies Company; and in 1809–10 he took part in the siege and capture of the two strategically important French colonies in the south-western Indian Ocean – the Île Bonaparte and the Île de France (see above under Josias Rowley).

Samuel Campbell then became captain of HMS Laurel, a 36-gun fifth-rate brigantine (1807–12; captured from the French as La Fidèle in 1809) which was wrecked on 31 December 1812 when it struck the sunken Govivas Rock in the Teigneuse Passage of the French port of Quiberon, while it was following a sister-ship, the 38-ton fifth rate frigate HMS Rota, through the narrow channel. Although the crew was saved, Samuel Campbell Rowley was one of the 96 men who were taken into captivity until the end of 1813; he was later court-martialled for endangering his ship but acquitted of all blame. On 24 March 1815 he was transferred to the HMS Impregnable, a 98-gun second rate ship of the line (1810–1906; sold) which was at that time flying the flag of his brother Josias (see above). On 28 September 1818 he began a three-year posting to HMS Spencer, a 76-gun third rate ship of the line that was based at Cork, Ireland, and used by his brother Josias Rowley as his flagship. From 1830 to 1832 he commanded HMS Wellesley, a 74-gun third rate ship of the line (1815–1940; badly damaged in a German air raid and broken up); he achieved flag rank on 10 January 1837 when he was made a Rear-Admiral of the Red (the third highest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-tier hierarchy of admirals); and he retired on half-pay in 1838. Although he married twice, he had no children.

Sir Joshua Ricketts Rowley (1785–1857; 3rd Baronet of Tendring, Suffolk, from1832) was the 2nd son of Sir William Rowley (1761–1832) the 2nd Baronet of Tendring, Suffolk, from 1790), the grandson of Sir Joshua Rowley (1734–90; 1st Baronet of Tendring, Suffolk, from 1786), and the great-grandson of William and Arabella. He began his career in the Royal Navy as a volunteer on HMS Boadicea (1797–1858; broken up), a 38-gun fifth rate ship of the line, on 1 February 1802, when she was commanded in the English Channel by his uncle, Captain (RN) Charles Rowley (see above). Joshua Ricketts then saw service in the West Indies, and on 26 June 1803 he took part in the attack on St Lucia, one of the Windward Islands, and its citadel Morne Fortunée, aboard the HMS Centaur (1797–1819; broken up), a 74-gun third rate ship of the line. In 1804 he was transferred to HMS Immortality (1795–1806; broken up), a former French frigate that had been captured on 20 October 1798, and he was subsequently wounded in an action off the north-western coast of Ireland. After this, he spent nearly four years as a Midshipman on HMS Ruby (1776–1821; broken up) and HMS Eagle (1774–1812; broken up) both of which were 64-gun third rate ships of the line and, again, commanded by his uncle Charles Rowley.

Joshua Ricketts was commissioned Lieutenant (RN) on 9 April 1808, served on the Jamaica Station for about two years – for part of that time as Flag Lieutenant to another uncle, Vice-Admiral Bartholomew Samuel Rowley, who was working there for the West India Company (see above). On 4 July 1810 he was made Acting Lieutenant-Commander and given command of the 16-gun brigantine sloop HMS Sparrow (1805–16; sold) before being confirmed in that rank in August 1810. On 30 September 1812 he was promoted Post Captain (RN) and given command of two smaller ships – HMS Sappho (1806–30; broken up), an 18-gun brigantine sloop, and HMS Shark (1779–1819; foundered in Port Royal Harbour, Jamaica), a 16-gun sloop – and the larger cruiser HMS Pelarus (1796–1820; sold for scrap). He then spent two years on the Mediterranean Station as captain of the HMS Sybille (1774–1833; sold), a former French frigate that was captured in 1794 and became a 44-gun fifth rate ship of the line in the Royal Navy. And from 1820 to 1823 he served once again on the Jamaica Station with his uncle Rear-Admiral Charles Rowley (promoted Vice-Admiral in 1825). On 24 June 1836 Joshua Ricketts took command of HMS Cornwallis, a 74-gun third rate ship of the line (1813–1957; broken up after being used as a jetty since 1865) that was serving on the Lisbon Station, and he retired to England in 1837. He attained Flag Rank on 3 April 1848 when he was promoted Rear-Admiral of the Blue (the lowest rank in the Royal Navy’s nine-tier hierarchy of admirals), and in 1855 he was promoted Vice-Admiral of the Blue (the sixth highest rank in the hierarchy). In 1824 he married Charlotte Moseley (1800–62) (no known children), became prominent in the County of Suffolk and died at 61, Wimpole Street, London, on 18 March 1857.

Given such a comprehensive and illustrious naval background, one can only wonder why Rowley’s love of water did not extend beyond the River Isis and whether, perhaps, he joined the heavy artillery for the sake of a quieter life.

Rowley’s mother was the daughter of the historian George Cary Elwes (1806–59) and Arabella Elizabeth Sophia Heneage (1808–53) (m. 1834).

George Cary Elwes graduated from Trinity College, Oxford, in 1827 and was made a Founders-kin-Fellow of All Souls in 1828.

Siblings

Brother of:

(1) Windsor Angerstein Rowley (1878–1946); unmarried;

(2) May Rowley (1880–1965); unmarried.

In the 1901 Census Windsor Angerstein was described as being “dumb and feeble-minded as a result of a fall when two and half years old” and from 1886 to 1893 he lived at the Normansfield Hospital, Teddington, Middlesex. The hospital was founded in 1868 for patients with “intellectual disabilities” by John Langdon Down (1828–96), who first described Down Syndrome, and closed in 1997.

May died at the family home at “Holmesland” in 1965. In 1934 a burglar broke into “Holmesland” and stole a gold hunter watch that had been given to one of her ancestors by Lord Nelson: she appealed for its return.

Education and professional life

Rowley attended Cheam Preparatory School, near Epsom, Surrey, from 1886 to 1891 (cf. J.R. Platt, G.T.L. Ellwood, A.G. Kirby, L.S. Platt, A.F.C. Maclachlan, R.N.M. Bailey, E.W. Benison). Founded in c.1645 by the Reverend George Aldrich (1574–1658), the school moved to nearby Tabor House in 1719, where it stayed until 1934 when it moved to its present site at Headley, Hampshire. It was sometimes known as Manor House Preparatory School because that, according to the Censuses, was its building’s proper name, and sometimes, from 1856, as Mr R.S. Tabor’s Preparatory School, when the Reverend Robert Stammers Tabor (1819–1900) became its Headmaster (until 1890) and set about turning it not only into a proper preparatory school, but, arguably, the top preparatory school in the country. Rowley then attended Winchester College from 1891 to 1896, where he became a Commoner Prefect and a member of Sixth Book, the senior academic class. He also rowed for ‘C’ House, won the Duncan Prize for Mathematics (1894) and the Prize for Natural Science (1893 and 1894). He matriculated as an Exhibitioner in Mathematics at Magdalen on 20 October 1896, having passed Responsions earlier in Michaelmas (autumn) Term 1896. He passed one part of the Preliminary Examination (Holy Scripture) in Trinity Term 1897 and was awarded a 2nd in Mathematics Moderations in Trinity Term 1898. In Trinity Term 1900 he was awarded a 3rd in Mathematics Finals (Honours), and he took his BA on 28 February 1901.

Winchester is not a “rowing school” because of the absence of a handy river, but when he was an undergraduate Rowley rowed for Magdalen and for the University. He was in the winning University IV in 1898, elected Magdalen’s Captain of Boats 1899–1900, and stroked the University VIII against Cambridge on 31 March 1900 (when two other Magdalen men were in the crew, one of whom was G.S. Maclagan at cox). But in 1900, Oxford lost even more decisively than they had done in 1899 – this time by 20 lengths in good weather conditions. The Times rowing correspondent put this down to the fact that by 1900, the Oxford crew had “lost their great stroke oarsman of the [previous] four years” – i.e. Harcourt Gilbey Gold (see Maclagan), who had stroked the Oxford VIII from 1896 to 1899 – whereas the Cambridge oarsmen had succeeded in maintaining their “machine-like regularity”, their “rhythm”, and their “even swing” that had brought them victory in 1899 for the first time in ten years. Despite this defeat, Rowley was a member of the College VIII for four years, and in summer 1900 he rowed in the College VIII, with Maclagan as cox and Harcourt Gilbey Gold at stroke, that wrested the Headship of the River from New College after a six-day battle. On 24 February 1900, five months before Maclagan, Rowley featured in The Isis as its 165th “Isis Idol” because of his rowing prowess and personal eccentricity, and his laudatio reads:

Unlike most Isis Idols no early visions or mysterious portents seem to have appeared to him to tell him of his future greatness. Contemporary authorities at Winchester agree in saying that he was remarkable for nothing but the fact that he had the smallest body and the largest head in the school. At Oxford[,] Togger’s brilliant career began by rowing in the Magdalen first Torpid in 1896; in the Eight next summer; in 1897 he got his trials, and in 1899 [he] stroked the winning Trial Eight; in November he parted his hair in the middle. His ideas on training are strictly his own. As soon as he has been ordered to commence training[,] the table in his room becomes studded with little white parcels with red seals, clearly hailing from the chemist. What they are composed of, and when they are disposed of, no one knows. It is all part and parcel of a mysterious diet on which he seems to thrive.

The writer then stressed that Rowley was very popular throughout the University and was known as “the dapper and spruce dandy, the ladies’ pet, the darling of society”. After which he continued his laudatio as follows:

Socially[,] our hero is chiefly noted for an expansive smile, extensive knowledge, and the intensity with which he tries to persuade or instruct those whom he has singled out for a lesson. His knowledge of the most trivial incidents of everyday life is unbounded, and his accurate information with regard to the price of every commodity from biscuits to Aquascutums is unrivalled. He will tell you himself that what he does not know with regard to mathematics, astrology, photography, and millinery is not worth knowing. It is hard to give an idea of Togger’s social powers to those who are unacquainted with them. His conversation always takes the form of a lecture or a treatise, delivered very hurriedly with no stops, but punctuated by frequent interjections of “D’ye-see-what-I-mean?”

Rowley was also, apparently, musically very gifted but proverbially absent-minded: “when asked for the toast, after a perfect Maxim-fire of ‘Wha?’s, he passes the cheese. He has never been known to shut a door.” Owing to his “skill in and keenness for photography”, he was known to a few as “Gillmann”, and:

his passion for this sport is carried out to such a pitch that he was once discovered in college at seven o’clock one summer’s morning, arguing with a workman as to the probability of his being allowed to have an archway removed in order that he might get a better view of some building he wanted to photograph. Togger was once the proud possessor of a tyke; but this harrowing tale we will pursue no further. Let it suffice to say that “Topsy’s” early demise was received with shouts of joy by her master, who rushed to the piano and played selections from the Circus Girl, as he said he had forgotten the “Dead March” from Saul.

Rowley’s eulogist concluded, not without a certain irony:

He has the sunniest of smiles and the temper of an angel. But ask him if mathematics is a narrow education, or if he intends to take exercise by sitting down and going backwards from Iffley to Oxford, or if the immensity of his chest is solely due to a kink in his back, or if he still owes Talboys a shilling for sulphur used in – well, never mind!

Rowley was a keen big game hunter, sending home large collections of fine heads and skins, and was considered a record-holding duck shot.

Charles Pelham Rowley, BA

(Source: MCA: PR/2/18 (President Warren’s Notebooks) p. 354; also in De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour 1914–18, p. 266)

Military and war service

In May 1900, on finishing his course at Oxford, Rowley was nominated for a University Commission in the Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) by the Vice-Chancellor, Dr Thomas Fowler (1832–1904) (President of Corpus Christi College 1881–1904; Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1899–1901). So Rowley served in the Second Boer War from 1900 to 1902 and then in India from 1902 to 1914, where he became known as a skilful photographer and hunter. He was promoted Lieutenant in 1902 and Captain in May 1913.

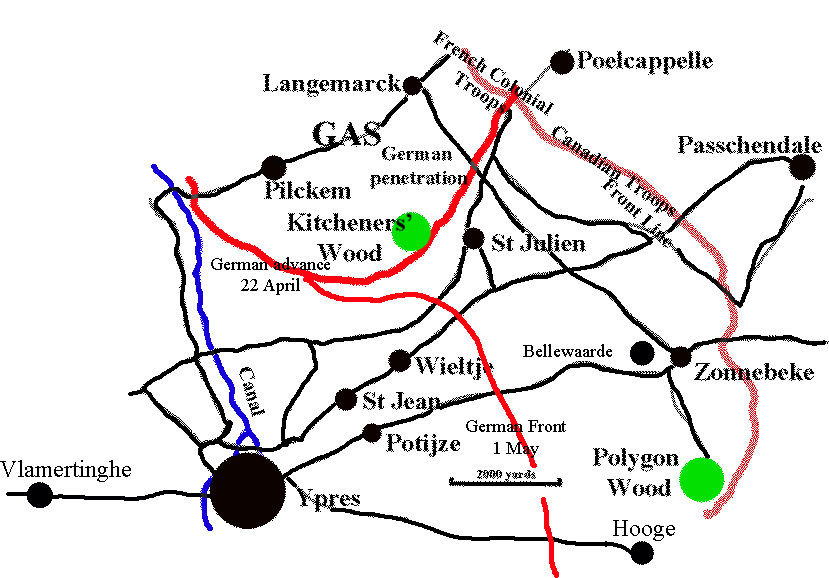

After the outbreak of World War One he trained heavy batteries at Tynemouth until March 1915 – when he was sent to France to be the Adjutant to the 13th Heavy Brigade, RGA, which, having been formed by transferring existing batteries from their previous units, consisted of the 1/1st North Midland Heavy Battery (withdrawn from the 46th Division), the 1/2nd London Heavy Battery, the 108th Heavy Battery, and the 122nd Heavy Battery. The Brigade was formally constituted in France on 18 April 1915, the day when Rowley joined its Staff at the Brigade headquarters alongside its Commanding Officer, Colonel Hopton Elliot Marsh, DSO (1866–1940), RGA, and Regimental Sergeant-Major Henry Bannerman (1870–1952; commissioned Captain 8 September 1915). When Rowley arrived, the 13th Heavy Brigade was supporting the 1st Canadian Division, which was positioned north-east of Ypres near St Julien. The Brigade HQ was responsible for co-ordinating the fire of the Brigade’s four heavy batteries, and on 19 April 1915, i.e. Rowley’s first day in the field, the Canadians asked them to “Register and destroy Passchendale church tower”, presumably because they had seen that the Germans were using it as an observation post.

At 05.00 hours on 22 April 1915 the Germans began the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915) by releasing chlorine gas over a four-mile front to the left of the Canadian troops – an area that was largely manned by French colonial troops from North Africa, the 45th and 87th Divisions (see V. Fleming), causing c.6,000 casualties. As a result of the gas attack, the Germans broke through and captured the 1/2nd North London Battery of 4.7-inch guns. A letter from Major Harold Blumfield Brown (1882–1950), Officer Commanding 2nd London Heavy Battery Royal Garrison Artillery (Territorial Forces), to Colonel Marsh, explains what happened, and a copy in the Brigade’s War Diary has been certified by “Captain Rowley, Adjutant”. The unit had been stationed in Kitcheners’ Wood (Bois-de-Cuisinères), but when they came under heavy artillery fire to which they could not respond because of the guns’ positioning, the men were ordered to take cover. At 05.30 hours they noticed Zouaves (French North African Light Infantry) running back and assumed them to be reserves; but at 05.45 they came under rifle fire from German infantry. Major Brown decided to retire, but not before removing the “strikers” from the guns and arming his men with the nine available rifles. But they soon came under heavy rifle fire and although the officers and men with rifles covered the retreat of the remainder until they could be covered by a Canadian unit, three officers and 15 other ranks (ORs) were killed, wounded or missing. During the morning the position of 13th Heavy Brigade’s HQ became untenable and it was ordered to retire to the Wieltje–St Jean Road and fire on Kitcheners’ Wood. This took them two hours, during which the situation changed.

So having no orders, Captain Rowley reported to Artillery HQ in Potijze and was ordered to Vlamertinghe, a few miles west of Ypres, where the batteries of 13th Heavy Brigade and its HQ stayed until Rowley left on 10 January 1916. At first, the Brigade concentrated on shelling the area that had been occupied until recently by the Germans – i.e. Pilckem, Kitcheners’ Wood, St Julien, Langemarck etc. But they later extended the shelling to locations where German troop movements and concentrations had been spotted by infantry or aviators – e.g. Bellewaarde, Zonnebeke and Hooge – and less well-known targets such as Dead Man’s Bottom and Mouse Trap Farm. The 13th Brigade also became involved in an artillery duel with German heavy guns that regularly fired at Vlamertinghe, and so was particularly concerned about German reconnaissance aircraft locating their batteries, which were regularly moved.

Rowley was absent from the unit from 18 to 24 October 1915, and ten days after being promoted Major at the end of December 1915 (London Gazette, no. 29,420, 28 December 1915, p. 13,006), he returned home to assist in the training of heavy artillery until October 1916. He was replaced as Adjutant in the 13th Heavy Brigade by Kenrick Morris Hamilton-Jones, MC (1894–1973).

On 29 October 1916, while at home on leave with his family at Botley, Hampshire, Rowley was accidentally killed, aged 39, by the bough of a large elm tree which had been partly broken off by the force of a gale but was still supported by other branches. While he was trying to clear these, the partially severed bough suddenly fell, fracturing his skull. He was buried in All Saints’ Churchyard, Botley, Hampshire; where he is also commemorated on the War Memorial. His Commanding Officer at Winchester wrote of him: “He was a real good & enthusiastic officer, a great help to me in the unwieldy show I had to manage – he took on all I asked of him & out of what was rather chaotic, he made an organized and exceedingly useful unit.” He left £8,853 12s. 7d.

The memorial window to Rowley and his father in All Saints’, Botley, Hampshire

(courtesy Martin Baxter)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors of The Slow Dusk would like to put on record that they did not become aware of Nigel McCrery’s excellent book Hear the Boat Sing (The History Press: Stroud, 2017) until January 2019, when The Slow Dusk was nearing completion. It provides detailed accounts of the lives of 42 Oxford and Cambridge Rowing Blues who were killed in action during World War I or, like Rowley, died because of the war, and as eight of these were Magdalenses or closely connected with Magdalen through a relative, the Editors and Mr McCrery have been following similar research paths without knowing of each others’ work and have made use of the same resources. But whereas Mr McCrery has focused more on the finer points of rowing, the Editors have focused more on family and social history, with the result that the two projects not only overlap, but complement each other well.

**Much, if not most of the detailed information on Rowley’s naval ancestors, the ships in which they served and the actions in which they fought that is contained in this brief biography comes from Wikipedia articles on-line, and we would like to express our sincere thanks for the availability of this resource.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Death of Captain [Richard Freeman] Rowley’, Kentish Mercury (Woolwich, Deptford and Greenwich area), no. 1,234 (26 August 1854), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Isis Idols: No. CLXV: Mr. Charles Pelham Rowley, O.U.B.C.’, The Isis, no. 189 (24 February 1900), pp. 19–1.

De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour 1914–18, 5 vols (1914–18), ii (1915), p. 266.

[Anon.], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, Major Charles Pelham Rowley (Magdalen College) [obituary] Oxford Magazine, Extra No. (10 November 1916), p. 40.

[Anon.], ‘Admiral C[harles] J[ohn] Rowley’ [obituary], The Times, no. 42,257 (14 November 1919), p. 16.

Rendall et al., i (1921), p. 108 (photo of drawing).

Edward Peel, Cheam School from 1645 (Gloucester: The Thornhill Press, 1974), passim.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 29, 40–2, 107, 114, 135.

J.K. Laughton, ‘Rowley, Sir Charles, first baronet (1770–1845)’, rev. Andrew Lambert, ODNB, vol. 48 (2004), pp. 18–19

–– ‘Rowley, Sir Joshua, first baronet (1734–1790)’, rev. Nicholas Tracy, ibid., pp. 22–23.

Robert McGregor, ‘Rowley, Sir William (c.1690–1768)’, ibid., pp. 27–8.

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 74, 111.

McCrery (2017), pp. 120–7.

Archival sources:

MCA: 04/A1/1 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1888–1907]), pp. 398–402, 438–46, 457, 461–4, 484.

MCA: 04/A1/2 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1907–26]), unpag.

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR/2/18 (President Warren’s Notebooks), p. 354.

OUA: UR 2/1/31.

ADM196/13/268.

WO95/387/1.

WO95/387/2.

On-line sources:

Wikisource, ‘A Naval Biographical Dictionary’: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Naval_Biographical_Dictionary (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Blaauwberg’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Blaauwberg (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Cape Finisterre (1805)’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cape_Finisterre_(1805) (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Cartagena’ (1758): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cartagena_(1758) (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Copenhagen (1801)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Copenhagen_(1801) (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Grand Port’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Grand_Port (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘British Invasions of the River Plate’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_invasions_of_the_River_Plate (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘First League of Armed Neutrality’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_League_of_Armed_Neutrality (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Franklin’s lost expedition’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin%27s_lost_expedition (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Invasion of the Cape Colony’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invasion_of_the_Cape_Colony (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Raid on Saint-Paul’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raid_on_Saint-Paul (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Rowley baronets’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rowley_baronets (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Bartholomew Rowley’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartholomew_Rowley (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Sir Charles Rowley, 1st Baronet’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Charles_Rowley,_1st_Baronet (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Joshua Rowley’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joshua_Rowley (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Josias Rowley’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josias_Rowley (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Samuel Campbell Rowley’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Campbell_Rowley (accessed 31 July 2022).

Wikipedia, ‘William Rowley (Royal Navy officer)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Rowley_(Royal_Navy_officer)#Family (accessed 30 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Sir Richard King, 1st Baronet’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Richard_King,_1st_Baronet (accessed 30 June 2018).

William Richard O’Byrne, ‘Rowley, Samuel Campbell’, A Naval Biographical Dictionary, Wikisource: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Naval_Biographical_Dictionary/Rowley,_Samuel_Campbell (accessed 3 July 2018).

J.K. Laughton, ‘Rowley, Sir Charles, 1st Baronet (1770–1845)’, rev. Andrew Lambert, ODNB, vol. 48 (2004), pp. 18–19; also available on-line: http://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2167/view/article/24222.

J.K. Laughton, ‘Rowley, Sir Joshua, 1st Baronet (1734–1790)’, rev. Nicholas Tracy, ibid., pp. 22–3; also available on-line: http://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2167/view/article/24224.

Robert McGregor, ‘Rowley, Sir William (c.1690–1768)’, ibid., pp. 27–8; also available on-line: http://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2167/view/article/24228.