Fact file:

Matriculated: 1904

Born: 1 October 1885

Died: 13 April 1917

Regiment: Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: Brown’s Copse Cemetery: V.F.4.

Family background

b. 1 October 1885 in Llanfairfechan, Caernarvonshire, as the only son of Sydney Platt (1861–1937) and Agnes Bertha Platt (née Marshall) (1863–1952) (m. 1884). During World War One, the family rented a flat at Wargrave Manor, Wargrave Hill, Wargrave, Berkshire, a large eighteenth-century country house in a large park; after the war they also spent much time at the Villa Beatrix, Pau, Basses Pyrénées, France.

Sydney Platt (1861-1937).

Parents and antecedents

Platt’s father was a scion of the Oldham firm that became the world’s most successful textile machinery manufacturer during the second half of the nineteenth century (1860–1908) (see John Rookhurst Platt). The history of the Platt family firm began in the late eighteenth century in Dobcross, Saddleworth, to the east of Oldham, where Henry Platt [I], Platt’s great-great-great-grandfather, worked as a blacksmith making carding equipment.

The company’s steady rise to prominence over a period of 70 years began in 1821/22, when Platt’s great-grandfather, Henry Platt [II] (1793–1842), and Elijah Hibbert, JP (1800–46), merged their firms in order to establish the firm of Hibbert & Platt in the “Old Works”, in Huddersfield Road, Oldham. In 1844, Henry [II]’s son, John Platt (later MP, JP, DL) (1817–72), the grandfather of both Lionel Sydney and his cousin John Rookhurst, moved the company’s headquarters to the “New Works”, a massive complex of buildings and internal railways on a site in the Wentworth area of Oldham that overlooked Manchester. John became the firm’s senior partner in 1846, and under his administration it systematically improved the techniques of cotton spinning and cloth weaving, and “perfected in succession the carding machine, the roving frame, and the self-acting mule, of which seven successive models were produced between 1843 and 1920”. According to Douglas Farnie, “Platt’s mules were the true basis of the industrial supremacy of Oldham, being unrivalled in length, in speed of operation and in productivity”. John’s managerial success during a period that is known as the “Cotton Famine” was also due to his substitution of Indian cotton for its more expensive American counterpart, thus stimulating Oldham’s textile engineering industry. In 1854 the firm changed its name to Platt Bros. & Co. and in 1868 it became a limited company. By the time of John’s unexpected death of apoplexy in Paris, when he was coming to the end of a six-week-long continental tour with his wife, it was employing c.7,000 people. This number increased to 15,000 by the 1890s and was twice that of Platt Bros’s nearest rivals, Dobson & Barlow of Bolton and the more conservative engineering firm known as the Soho Works that had been founded in the 1790s and was run by Asa Lees (1816–62) at Greenacres Moor, a suburb of Oldham to the west of the River Medlock and opposite the village of Lees. And if one adds in Platt’s employees’ dependents, then they constituted about 42 per cent of Oldham’s population, causing the dialect author and former weaver Ben Brierley (1825–96) to christen the town “Plattington” in his Tales and Sketches of Lancashire Life (1885).

Platt’s gained awards for its products from all over the world, and its owners, especially John Platt, whom an obituarist described as having few equals in his capacity as “an enterprising man of business”, were heavily involved in local politics and local affairs. John Platt was, for example, one of the largest subscribers to the campaign which enabled Oldham to turn from a township into a Borough in 1849, and in 1854–55 he became the fourth Mayor of Oldham (the town’s first Liberal Mayor), an office that he also held in 1855–56, 1856–57, and 1861–62. An obituarist described him as the “head of Oldham’s Liberals”, and as a subscriber to the doctrines of the Manchester School he was an ardent supporter of free trade and therefore the Anti-Corn Law League, parliamentary reform and religious liberty. Indeed, he described himself as a disciple of the radical and Liberal statesman and industrialist Richard Cobden (1814–65), and accompanied him to Paris in 1859 to assist in the negotiations with the French Government that issued in the French Commercial Treaty (the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty) of January 1860. In 1865 John Platt was elected as the junior Liberal MP for Oldham; he was re-elected by six votes in 1868, during a contest that was particularly fierce because of Disraeli’s appeal to the country over the Irish question, and he remained in office until his death in 1872. An obituarist described him as “one of the most earnest and consistent Liberals” in Parliament.

John Platt was well-known for his public generosity in the Oldham area. He paid for the building and furnishing of the extensive Science and Art Schools in Oldham’s Union Street, and even before education became obligatory, he made it compulsory for the boys who worked in his mills, being of the opinion that “the education of the young” was a vitally important matter and that, “as an employer of labour, any sacrifice or outlay which might be entailed upon him in this respect would be found to his future advantage and benefit”. He became a member of the bench in 1851 and ultimately became a Borough and County magistrate.

In 1857 John Platt became the owner of the 150-acre estate surrounding the half-built and semi-derelict mansion of Bryn-y-Neuadd, near Llanfairfechan, in Caernarfonshire (now Conwy), on the North Wales coast between Penmaenmawr and Bangor. He became High Sheriff of Carnarvonshire for 1863 and also its Deputy Lord Lieutenant.

Bryn-y-Neuadd, near Llanfairfechan, Caernarfonshire, Conwy.

In 1864 John Platt paid for the building of a new stone church in the Tractarian style at Llanfairfechan by C & J Shaw of Saddleworth, near Oldham; it has a very imposing spire and was consecrated in the same year as Christ Church, Llanfairfechan. Since 1999 it has been known as St Mary’s and Christ Church, Llanfairfechan. It contains a plaque commemorating Lionel Sydney Platt.

St Anne’s and Christ Church, Llanfairfechan, Conwy.

By 1878, Platts had reached unrivalled prominence: it was supplying machinery for turning fibre into yarn, fabric and textiles all over the world and had made Oldham the centre of cotton spinning in Lancashire. In 1882, Platt Bros. & Co. took out “the first Oldham patents for ring frames”, a yarn- and cotton-spinning machine that worked continuously, not intermittently like the self-acting mule, a cross between Arkwright’s water frame and James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny that had been invented in c.1779 by Samuel Crompton (1753–1827). The new machine “could be tended by cheap semi-skilled labour rather than by the highly-paid labour of the mule spinners”, and so enabled Oldham to become “the leading centre in Lancashire of the new technology”. During the period 1873 to 1902 Platt Bros’s profits averaged 11.4% p.a. and its dividends 18% p.a., reaching a peak of 37% in 1876–77; during the period 1903–74 its dividends averaged 9.5% p.a. and reached peaks in 1891–92 and 1926. Platts recorded its peak production of power looms in 1879 and its peak export of spinning machines in 1896, and although the firm started to decline during the “Edwardian boom”, it made record profits in 1922 and never passed a year without issuing a dividend to its share-holders “until the decade 1927–36”.

However, of John Platt’s six sons and six daughters, only his second son, Samuel, the father of John Rookhurst Platt, took any great interest in the family firm. The others, including his sixth and youngest son, Sydney, Lionel Sydney’s father, seem to have led lives of wealth and leisure. Sydney may have spent some time in the Regular Army as a young man; in 1879 he was gazetted 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Carnarvon Militia (London Gazette, no. 24,790, 9 December 1879, p. 7,267); and Lieutenant the following year (LG, no. 24,893, 19 October 1880, p. 5,326). In 1881 he was a lieutenant in the Royal Carnarvon Militia and an Army Pupil boarding in Upton cum Chalvey, Buckinghamshire. On his coming of age in 1882 he came into possession of the Bryn-y-Neuadd estate. His oldest brother and head of the family, Colonel Henry Platt (1842–1914), lived on the adjoining estate of Gorddinog. After he married in 1884, Sydney and his family lived on his estate in North Wales. In 1888 he was appointed Sheriff of Caernarvonshire. Although, within three years, the original house had been extensively extended and improved, Sydney’s wife never really settled there, and after 13 years the family moved to Berkshire. Bryn-y-Neuadd Hall was sold in 1898 to St Andrews Hospital, Northampton, to provide care for “lunatics and idiots”. Then, after World War One, Sydney’s family moved again, this time to the Villa Beatrix, in the French winter resort of Pau (Basses Pyrénées), where there was a congenial clutch of English institutions that included a cercle anglais, a fox hunt, a racecourse and a golf club. Like his wife after him, Sydney died here, leaving £567,294, the equivalent of over £17 million in 2005.

Sydney Platt playing golf at Pau

Platt’s mother was the daughter of Thomas Horatio Marshall (1834-1917), who in 1881 lived with his family at Towyn Lodge in Trearddur Bay, Anglesey, and was a Colonel in the 3rd Cheshire Rifle Volunteers. He was knighted in the Birthday Honours of 1906 among other officers of the Auxiliary Forces. The Marshall family at one time owned Hartford Manor, in Hartford near Northwich , Cheshire and were the leading salt dealers in the county.

Lionel Sydney Platt

Siblings and their families

Platt’s sister was Eira Gwendolen (1887–1979), later du Breil after her marriage in 1924, at Pau in France, to Charles Georges Joseph Antoine du Breil (1894–1951), Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur and a regular officer in the French Hussars.

Wife and children

In 1914 Platt married Gillian Mary (née Spencer-Warwick) (1893–1981). She was the daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Spencer Warwick (1865–1933), a professional soldier in the Devonshire Regiment. The couple lived at St Bruno, Sunningdale, Berkshire, but after her husband’s death, Gillian Mary moved to 19, Cliveden Place, London SW1. She changed her name to Bryant after her marriage (in 1919) to Captain Charles Edgar Bryant, DSO (1885–1950), an officer in the 7th Hussars, later a Major in the 12th Lancers, the Royal Flying Corps and the RAF. They had one son and one daughter).

Gillian Mary Platt (née Spencer-Warwick) (1893-1981).

Gillian’s older brother, John Charles Spencer-Warwick (1890–1915), was killed in action at Gallipoli on 4 June 1915 while serving as a Lieutenant in the Anson Battalion of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division.

Platt and his wife had one daughter, Cicely Noel (1915–2002), later Spender after her marriage in 1938 (in Valetta, Malta) to the Reverend Alan Spender, Chaplain RN (1911–53); two sons, one daughter; then Holden after her marriage in 1955 to Richard Shuttleworth Holden (1909–83).

Cicely Noel Platt (later Spender) (1915-2001) (c. 1920).

Education

Platt attended Cheam Preparatory School, near Epsom, Surrey, from c.1892 to 1899 (cf. J.R. Platt, G.T.L. Ellwood, A.G. Kirby, A.F.C. Maclachlan, R.N.M. Bailey, E.W. Benison, C.P. Rowley). Founded in c.1645 by the Reverend George Aldrich (1574–1658), it moved to nearby Tabor House in 1719, where it stayed until 1934 when it moved to its present site at Headley, Hampshire. It was sometimes known as Manor House Preparatory School because that, according to the Censuses, was the proper name of its buildings, and sometimes, from 1856, as Mr R.S. Tabor’s Preparatory School, when the Reverend Robert Stammers Tabor (1819–1900) became its Headmaster (until 1890) and set about turning it into a proper preparatory school and, arguably, the top preparatory school in the country. Platt then attended Eton College from 1899 to 1904 and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 28 April 1904, having been exempted from Responsions. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1905 but then left without a degree.

Military and war service

After leaving Oxford, Platt was accepted for the Army as a University Candidate and commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 17th (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) Lancers on 29 November 1905 (London Gazette, no. 27,858, 28 November 1905, p. 8,538). He was promoted Lieutenant on 20 July 1907 and served with the Regiment in India, where he made a name for himself as a gentleman rider. On 23 June 1913 he was made Adjutant of the 1/1st Denbighshire Hussars (LG, no. 28,733, 1 July 1913, p. 4,644), a Yeomanry regiment that consisted of 26 officers and 448 other ranks, and was promoted Captain on 15 April 1914.

The Regiment left Beccles as part of the 4th Dismounted Brigade on 2 March 1916, embarked at Devonport on 2 March 1916, and arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 15 March. On 14 April 1916, after a month’s acclimatization, the Regiment left camp at Merimde Beni Salame in the western Nile Delta, and arrived at El Alamein on 19 April to form part of the Moghara Field Force, whose primary task was to fortify the defences at Moghara Oasis and El Alamein. Although Platt’s name never occurs in the Regiment’s War Diary, he stayed with the Regiment in Egypt until 28 July 1916, when he resigned his position as Adjutant. He arrived in Marseilles on 11 August and joined the Royal Flying Corps in Britain on 9 September 1916.

Once back in England, Platt learnt to fly in a Maurice Farman biplane at the Military School, Brooklands, in September/October 1916, and was awarded his wings on 23 November 1916. From December 1916 onwards he served with 57 (Fighter Reconnaissance) Squadron, which had been formed at Copmanthorpe, near York, on 8 June 1916. It was mobilized between 6 November and 27 December 1916, after its strength had been increased from 12 to 18 F[arman] E[xperimental] 2(d)s, an improved version of the twin-seat (pusher) FE2(c) whose pilot sat in the rear cockpit just in front of the engine, and whose observer sat in the front cockpit (see H.M.W. Wells). The FE2(d) was powered by the excellent new 250 horsepower Rolls-Royce (Eagle) aero-engine, whose additional power gave the aircraft better performance at medium to high altitudes and enabled it to carry a greater payload, such as four, not just two, Lewis Guns. Although, by the end of 1916, the FE2(d) was obsolescent, the “perfectly conceived”, agile, two-seater Bristol Fighter F2A – the “Biff” or “Brisfit” – which had first flown in March 1916, did not see squadron service in France until March 1917, when it equipped 48 Squadron, at first with disastrous results. Indeed, even by July 1918, the modified and more powerful Bristol Fighter, the F2B, which had first flown in late October 1916 and could reach 123 mph, equipped only 17 RAF squadrons.

We know very little about Platt’s service with 57 Squadron, but he attended a course at the School of Aerial Gunnery at Cormont, seven miles east-north-east of Le Touquet-Paris-Plage, from 10 to 27 February 1917, was on leave, probably in England, from 28 February to 14 March 1917, and became an Acting Flight Commander with the rank of Captain on 16 March 1917 (London Gazette, no. 29,994, 21 March 1917, p. 2,828). On 5 April 1917 Platt claimed to have downed a German aircraft while he and his Observer, Second Lieutenant Thomas Margerison (1894–1917), who had transferred into the Royal Flying Corps from the home-based 1/1st Huntingdonshire Cyclist Battalion, were on an offensive patrol at 12,000 feet over Arras and Cambrai. Their combat report reads as follows:

When on Offensive Patrol with 5 F.E.2(d)s, 3 Hostile Aircraft approached from rear. The whole formation turned and the rear machines attacked. F.E.2(d) A/5150 [Platt’s machine] dived at a H.A. [a single-seater biplane, probably an Albatros Scout] which was engaged just below, and which presented only a crossing shot. The Observer was able to fire a burst of about 10 rounds at a range of about 50 yards when the H.A. dived to earth apparently under control. The H.A. was seen to land successfully in a ploughed field.

Platt’s final flight, with Margerison as his Observer, took place on the worst day in a very bad month – which came to be known as “Bloody April” because the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service lost three times as many aircraft as the Germans during the same period. On Friday, 13 April 1917, Platt was leading a flight of six FE2(d)s from 57 Squadron on a reconnaissance mission south-west of Douai which took them over the area Vimy-Beaumont-Palluel. The patrol took off from the aerodrome at Fienvillers, about 25 miles east of Abbeville, at 07.00 hours, and must have headed north-east, but two of the six machines experienced engine trouble and had to return to base; a third had to make a forced landing at Arras; a fourth lost formation and encountered eight enemy aircraft which, for whatever reason, refused combat; and the other two machines, including Platt’s (A5150), failed to return. A photograph of Platt’s mangled machine is reproduced in Davis, Dye and Henshawe’s remarkable monograph on the FE2 (2009), but the War Office was unable to issue a death certificate until 4 September 1917, when confirmation of Platt’s and Margerison’s deaths was finally received from Germany. A subsequent letter from the Air Ministry to Platt’s family of 9 August 1922 concluded that “no general engagement of the patrol […] would appear to have taken place”, and the whole sorry incident says much about the poor state and vulnerability of the now obsolete FE2(d). A few weeks later, 57 Squadron was re-equipped with the two-seat (tractor) DH4 day-bomber which could achieve a speed of 136 mph and climb to 20,000 feet in less than 20 minutes. It later emerged that Platt, aged 31, and Margerison, aged about 23, met their deaths just north-east of Vitry-en-Artois and about three miles south-west of Douai, and were probably shot down by Leutnant Heinrich Gontermann (1896–1917) of Jasta (Jagdstaffel) 5 flying a much superior Albatros DIII or DV.

A German photo of the wreckage of Platt’s machine

(http://www.stanwardine.com/genepic/platt_lionel_sydney_rfc.pdf).

Jasta 5, which, from October 1915 to February 1917, numbered Hermann Goering (1893–1946) among its pilots, was nicknamed the “Green Tails” and had, by the end of World War One, become the third most successful fighter squadron in the German Air Force, with 251 accredited victories. Gontermann, who like Platt began his military career as a cavalry officer, was a deadly shot with an eye for his opponents’ blind spots, and one of the Squadron’s 14 aces, with 39 victories to his credit. In April 1917, Jasta 5 was stationed in the grounds of Château Boistrancourt, and by googling that location, you will find a group photo of its pilots that was taken in that very month: Gontermann is second from the left in the front row and wearing the Iron Cross First Class that he had been awarded on 5 March 1917 for shooting down several enemy aircraft, including two FE2(d)s from 57 Squadron. In “Bloody April” 1917 alone, he was credited with 11 victories. On 17 May 1917 he was awarded the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest decoration for valour, and he met his death, aged 21, on 31 October 1917 when the Fokker Triplane that he was testing broke up in mid-air.

Brown’s Copse Cemey, Roeux;Grave V.F.4.

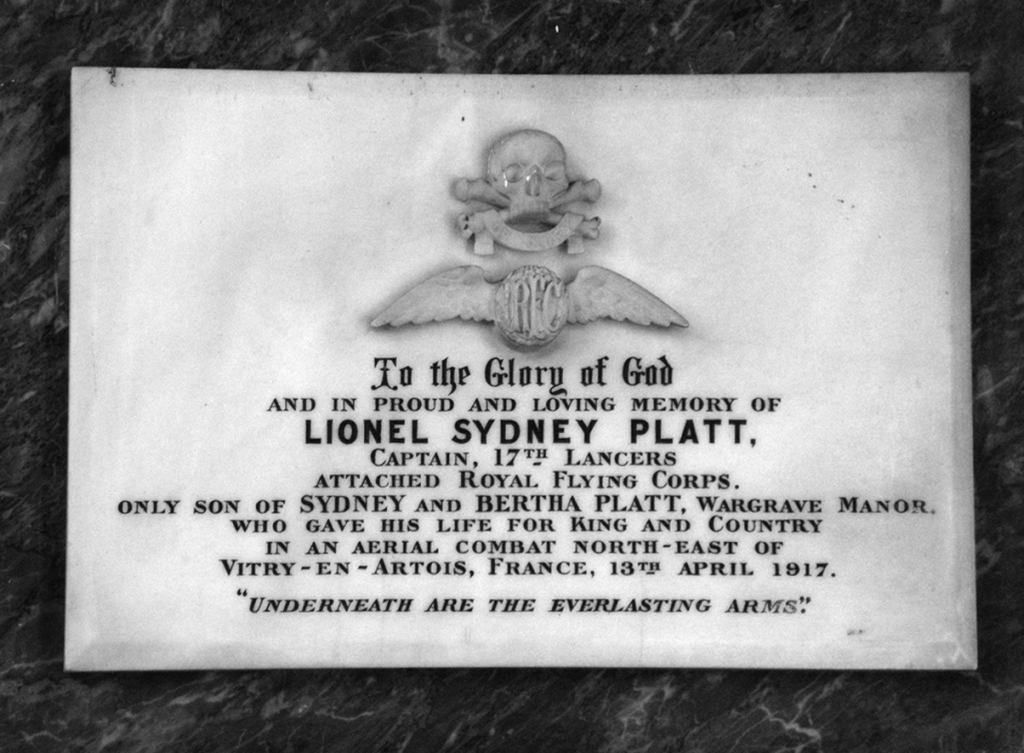

The deaths of Platt and Margerison were not formally accepted by the British until September 1917, and when their bodies were finally retrieved, the two men were at first buried behind the German lines in the Communal Cemetery at Vitry-en-Artois. But in around June 1920 their bodies were exhumed and transferred to Brown’s Copse Cemetery, Roeux, east of Arras, Platt in grave V.F.4 and Margerison in Grave V.F.1; Platt’s headstone bears the inscription “Underneath are the Everlasting Arms” (Deuteronomy 33:27), as does his commemorative plaque (1918) by William Silver Frith (1850–1924) in St Mary’s and Christ Church, Llanfairfechan, Conwy. Platt left £1,108 12s. 2d. to his widow.

The Plaque by William Silver Frith that commemorates L. S. Platt in St Anne’s and Christ Church, Llanfairfechan, Conwy (Courtesy Peter Jones).

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**Duncan Gurr and Julian Hunt, The Cotton Mills of Oldham, 3rd edition (Oldham: Oldham Arts and Heritage Publications, 1998), pp. 7–8, 24–6 and 29–30; it contains three very informative essays by

**Douglas A. Farnie (1926–2008): ‘The Metropolis of Cotton Spinning, Machine Making and Mill Building’, pp. 4–14; ‘The Machine Makers’, pp. 25–6; and ‘The Spread of Ring Spinning in the Oldham Area’, pp. 29–30.

**Douglas A. Farnie, ‘Platt family (per.c.1815–1930)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 44 (2004), pp. 535–43 (esp. pp. 536–9).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Death of Mr. John Platt, M.P.’ [brief obituary notice], Birmingham Daily Post, no. 4,319 (20 May 1872), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Mr. John Platt, M.P.’, The Blackburn Standard, no. 1,952 (22 May 1872), [p. 3].

[Anon.], ‘Death of Mr. John Platt, M.P.’, Manchester Times, no. 755 (25 May 1872), p. 10.

[Anon.],’Coming of Age Rejoicings at Llanfairfechan’, Liverpool Mercury, no. 10,632 (6 February 1882), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Lionel Sydney Platt’, The Times, no. 41,524 (7 July 1917), p. 9.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice [obituary]’, The Oxford Magazine, 36, no. 1 (19 October 1917), p. 9.

Walter W. Kempe, Platts of Oldham: A Series of Very Brief Notes Outlining the History and Growth of Platt Bothers and Company Ltd. Oldham (1964) (Pamphlet in the Oldham Local Studies Library).

–– Platts of Oldham: Abbreviated Extracts from a Series of Notes Outlining the History and Growth of Platt International Ltd. Oldham Works, Oldham (n.d.) (Pamphlet in the Oldham Local Studies Library).

Morris (1968), pp. 49–52, 112–19.

Edward Peel, Cheam School from 1645 (Gloucester: The Thornhill Press, 1974), passim.

Douglas A. Farnie, The English Cotton Industry and the World Market, 1815–1896 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 159–60.

–– ‘Platt Bros. & Co. Ltd of Oldham, Machine-Makers to Lancashire and to the World: An Index of Production of Cotton Spinning Spindles, 1880–1919’, Business History, 23, no. 1 (March 1981), pp. 84–6.

–– ‘The Marketing Strategies of Platt Bros. and Co. Ltd. of Oldham, 1906, 1940’, Textile History, 24, no. 2 (1993), pp. 147–61.

Walter O. Prestwich, A Story of Platt Brothers of Oldham (The World Renowned Company of Textile Machine Makers) 1821–1981 (1986) (Bound Typescript in the Oldham Local Studies Library).

R.H. Eastham, Platts: Textile Machinery Makers (Oldham: Publishers, 1994).

Norman Franks, Russell Guest and Frank Bailey, Bloody April … Black September (London: Grub Street, 1995).

G.K. Merrill, Jagdstaffel 5 (Berkhamsted: Albatros Productions, 2004– ).

Peter Hart, Bloody April: Slaughter in the Skies over Arras, 1917 (London: Cassell, 2006).

Jon Guttman, Pusher Aces of World War 1 (Osprey Aircraft of the Aces, no. 88) (Oxford and New York: Osprey Publishing, 2009), pp. 72–7.

Mick Davis, Peter Dye and Trevor Henshawe, The Royal Aircraft Factory FE2b/d and Variants in RFC, RAF, RNAS and AFC Service (London: Royal Air Force Museum in collaboration with Cross & Cockade International, 2009), p. 156 (photo of Platt’s mangled FE2).

Blaine Taylor, Hermann Goering in the First World War: The Personal Photograph Albums of Hermann Goering (Oxford and Charleston SC: Fonthill Media, 2014).

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/52.

RAFM: Casualty Card (Platt, Lionel Sydney)

AIR1/128/15/40/172.

AIR1/693/21/20/57.

AIR1/1224/204/5/2634.

WO95/4427.

WO339/6363.

WO95/4427.

WO339/6363.

On-line sources:

William Bridge, ‘Captain Lionel Sydney Platt – 17th Lancers & Royal Flying Corps’:

http://www.stanwardine.com/genepic/platt_lionel_sydney_rfc.pdf (accessed 5 December 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Heinrich Gontermann’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_Gontermann (accessed 5 December 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Platt Brothers’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platt_Brothers (accessed 5 December 2019).