Fact file:

Matriculated: 1907

Born: 3 October 1888

Died : 25 September 1916

Regiment: Royal Berkshire Regiment and Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: Canadian Cemetery No. 2 [62]: 10.C.17–18

Family background

b. 3 October 1888 as the elder son of Henry Watkins Wells (1855–1932) and his second wife (Alexandra) Mary Wells (née Hayllar) (1862-–1950) (m. 1885). Sotwell Hill House, Wallingford Rd, Sotwell, Berkshire.

Parents and antecedents

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Wallingford was well known for the quality of its malt and at one point 17 maltings were operating within the town. Wells’s father, who also described his profession as “banker”, was a scion of a prominent Wallingford family that had made its money by brewing, provided the borough with several prominent citizens and public figures, and owned one of the town’s two biggest breweries. But where Hilliard’s brewery was founded in 1830 and ceased to function in 1878, Wells’s brewery was founded in 1720 and thrived until 1928, when it was bought out by Ushers and its brewing operations were transferred to Trowbridge, Wiltshire. In the following year, the old brewery building in Goldsmiths’ Lane was sold to the Freemasons and became Wallingford’s magnificent Masonic Lodge.

Wells’s mother was the third daughter of the prolific painter James Percy Hayllar (1829–1920) and his wife Ellen Phoebe Hayllar (née Cavell) (1827–99) (m. 1855).

James Percy Hayllar, who prospered as an artist, exhibited at the Royal Academy, and left £22,857 4s 7d (gross), is best remembered nowadays as a landscape and genre painter who also produced portraits of children. When one of his paintings recently appeared on The Antiques Roadshow, it was valued at £15,000.

James Percy Hayllar sired four sons and five daughters, of whom four were gifted artistically: Jessica Ellen (1858–1940), who was noted for her still-lifes and domestic scenes, Edith Parvin (1860–1940), who was noted for her still-lifes, domestic scenes, and sporting scenes but who gave up painting after her marriage in 1896, (Alexandra) Mary (1862–1950), Wells’s mother, who was noted for the meticulousness of her still-lifes and pictures of children but who all but stopped painting after she married, and (Beatrice) Kate (1864–1959) who gave up painting to become a nurse in c.1900. In 1875 the Hayllars settled at Castle Priory, a large house fronting the Thames at Wallingford, where the family remained until 1899. This explains how Henry Watkins Wells got to know (Alexandra) Mary and how the Rector of Wallingford (later of Sutton Courtenay), the Reverend Edward Bruce Mackay (1861–1921), met Edith Parvin (m. 1896). Sport and physical exercise were an important part of life at Castle Priory, and besides teaching his daughters how to paint and draw, Hayllar also taught them how to swim and row, as a result of which the four eldest were all accomplished oarswomen. With their father as cox, they used to row their boat 27 miles in a morning to the Henley Regatta.

Wells’s mother was a cousin of the English nurse Edith Cavell (1865–1915), whom the Germans shot as a spy in Brussels in 1915 for helping Allied officers escape from captivity, an event that caused great outrage world-wide and bolstered the idea in Allied countries that they were engaged in a moral crusade against an inherently barbarous nation. During the trial and the period leading up to her execution, Cavell’s doctor was the German Expressionist poet Gottfried Benn (1886–1956) (cf. Ernst Stadler).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Dora Watkins (1886–1966);

(2) Muriel Watkins (1891–1978); later McMullan after her marriage (1913) to George McMullan (later JP, FRCS) (c.1883–1963), three sons (two of whom died in infancy), two daughters;

(3) Beatrice Watkins (1896–1984); later Lilley after her marriage (1919) to Lieutenant RN (later Captain RN) Austin Gerald Lilley (1890–1937), seven sons, two daughters; then Collard after her marriage (1939) to Robert William Collard (1883–1970);

(4) Joyce Mary (1899–1994); later Gardiner after her marriage (1921) to Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Bernard Calwoodley Gardiner, CB (1880–1932), three daughters;

(5) Guy Watkins (1903–81); married (1940) Violet Evelyn Chown (née Towers; c.1888–1973).

George McMullan was a medical graduate of Edinburgh University and began practising medicine in Wallingford in 1908. During the war, he worked as a military Medical Officer and surgeon and subsequently became a FRCS (Edinburgh). He was well-known for his shrewdness as a diagnostician, his phenomenal memory, and his capacity for hard work, and he played an important part in setting up a hospital at Wallingford. On his retirement in the 1950s, he was given the freedom of the borough in recognition of his services.

From September 1918 Austin Gerald Lilley commanded HMS Tower, an ‘R’ class destroyer, and by 1932 he was Commander and the Captain of HMS Watchman, a ‘W’ class destroyer that had been launched in 1917.

Robert William Collard seems to have been a technical officer in the Regular Army.

Bernard Calwoodley Gardiner was the son of a clergyman and educated at Marlborough. He was commissioned into the Royal Marines Light Infantry in 1897, promoted Lieutenant in 1898, Captain in 1905, and emerged from World War One as a Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel. A communications specialist when wireless telegraphy was in its infancy, he helped set up a wireless station in Bermuda in 1907 and in 1910 he became the Senior Instructor at the Royal Naval Wireless School at HMS Vernon, the shore base at Portsmouth, whence he was transferred to the Royal Engineers on attachment as an Instructor at the Military School of Engineering at Chatham, Kent. He returned to the Navy in 1914 as a telegraph officer on the staff of Admiral Lord Jellicoe (1859–1935), the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet during the Battle of Jutland and until his replacement in November/December 1916 by the younger and more aggressive Admiral Lord Beatty (1871–1936). Gardiner became a member of Beatty’s staff as Wireless Officer to the Grand Fleet. He remained in other senior positions involving wireless telegraphy throughout the 1920s and became a full Colonel in 1927 and Colonel 2nd Commandant of the Royal Marines in 1929. He died at his home in Wallingford after a long illness.

We do not know what Guy Watkins Wells did during the 1920s, but on 3 December 1934 he was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment at the London Sessions for conspiring, together with his future wife Violet Evelyn Chown, to defraud creditors. Violet Evelyn, who sometimes added Georgette to her name, had been an undischarged bankrupt since c.1928; and by the time of her trial, she had 16 County Court judgments against her for unpaid debts, involving a total of nearly £400, and since being declared bankrupt, she had amassed debts amounting to £2,000. She met Guy Watkins Wells in 1931 when she opened the White Monkey Club in Maidenhead, Berkshire, of which Guy was the tenant. Her first husband, Joseph Alfred Chown (1877–1942) (m. 1915), had described himself in the 1901 Census as a Phonograph Manufacturer and in the 1911 Census as a Continental Banker. When he applied for a Commission in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), he gave his profession as a Mining Engineer. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the RFC on 7 July 1916, promoted Lieutenant 7 January 1918, and served as an Assistant Equipment Officer specializing in engines. He sailed to New York first-class in 1919, speculated in oil and property amounting to $2,600,000 in Louisiana and Texas in 1920, and was an undischarged bankrupt from 1922 to 1930. When Chown divorced Violet in 1936, he cited Guy Watkins as the co-respondent; Chown later became a turf accountant in Twyford, Berkshire, but was declared bankrupt.

Education and professional life

From 1898 to 1902, Wells attended Windlesham House Preparatory School, Brighton, Sussex, which was England’s first real preparatory school and became one of the top five English preparatory schools in the nineteenth century (cf. C.A. Pigot-Moodie, G.B. Lockhart, J.R. Philpott). Founded on the Isle of Wight in 1837, the school moved to Brighton in 1838 and to new buildings in 1846. Wells then attended Harrow School from 1902 to 1907 and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1907, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1907. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1908; he was awarded a 3rd in Modern History in Trinity Term 1910; and he took his BA on 1 December 1910. During his time at Magdalen he played cricket in the College’s First XI; six members of the team (M.K. MacKenzie, G.B. Gilroy, I.B. Balfour, Wells himself and the two brothers C.F. Cattley and G.W. Cattley) would be killed in action. After leaving Oxford, he became a Director in the family brewery at Wallingford.

War service

Wells, who was 5 foot 8 inches tall, attested on 16 October 1914, joined the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”), served in ‘F’ Company, and rose to the rank of Lance-Corporal. He left the unit on 8 March 1915 and on the following day was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 1/4th Battalion, the Princess Charlotte of Wales’s (Royal Berkshire) Regiment. The Battalion arrived in Boulogne on 31 March 1915 as part of 145th Brigade, 48th (South Midland) Division (Territorial Forces), and after a period of training it made its way to the trenches at Hébuterne (23 July) via Houchin (12 July), Lières (17 July), Doullens (19 July), Marieux (20 July), and Bayencourt (21 July). At Hébuterne, opposite Thiepval and Gommecourt, it relieved the 1/4th Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and alternated between the same trenches and billets at Authie and Sailly-les-Bois and, occasionally, Couin until 16 May 1916.

Wells, who arrived in France on 12 July 1915, joined up with the Battalion and was assigned to ‘C’ Company on 22 November 1915. At the time, this part of the front was fairly quiet and the Battalion suffered relatively few casualties during its nine months in the area. But throughout the winter, the Battalion’s worst enemy was water. By 29 November it was knee-deep in the trenches; on 30 November the Battalion War Diary remarked: “All fire and communication trenches were in a bad state, and only a few pumps could be obtained from the RE’s.” So bad was the situation, that a lot of precautions were ordered for the prevention of trench foot. On 1 December the War Diary reads: “All working parties were employed in trying to cope with the mud and water in the trenches, which were in a deplorable state owing to the incessant rain. All the trenches were knee-deep in liquid mud, and in many places waist-deep: several men had to be dug out.” The complaint continued on the following day: “The trenches show no improvement in spite of the continual pumping day and night: the dug-outs began to fall in too. The trenches become drains for the land as the water was rising even when the pumps were going.” When the Battalion was in billets at Authie from 6 to 14 December, Wells’s ‘C’ Company were instructed in bombing, wire-breaking and the wearing of smoke helmets, and from 21 to 28 December, Wells was sent away on a bombing course. Nevertheless, he came back to the Battalion for Christmas Day, which was spent away from the trenches and seems to have been greatly enjoyed. The War Diary reads:

A unique and successful day. Arrangements were made at the various estaminets in the village [of Authie] for the use of their rooms for Company dinners [from 12.30 to 18.00 hours]. Three pigs were bought and distributed amongst the Companies, as pork was the favourite meat. The Commanding Officer gave a pudding to each N.C.O. and man; others were received from the ‘Daily hens’ Fund, and a parcel, containing a shirt, muffler, socks and chocolate: the latter had been provided out of a fund raised in Bedfordshire by Mrs Sernocold [the Commanding Officer’s wife] and Mrs F.R. Hedges. The sum of £750 was received in addition to gifts in kind. The thanks of the Battalion are due to these ladies, and all the contributors of the different gifts. […] The Commanding Officer and Adjutant visited each Dinner, wishing the men a Happy Xmas and New Year, and a speedy return to their homes at the conclusion of the war. […] The Officers dined together at the Château, where a most successful and jolly Evening was spent. Major Clarke proposed the health of the Commanding Officer, who briefly responded. The thanks of the Mess are due to Madame Dewailly, who so kindly lent the room, glass, cutlery etc. for the table.

Four days later the Battalion was back in the trenches at Hébuterne, taking casualties during sporadic actions. But the worst enemy was still active, and on 16 February 1916 the War Diary tells us: “All available men were employed in pumping in trying to deal with the volume of water”; then, on 17 February: “Trenches were full of water and in many places the walls were falling in. All day was spent in dealing with the damage.” So when the Battalion was relieved on 24 February for four days’ respite at Courcelles, the author of the Diary noted rather tersely that “all ranks were very glad of the change”. But once back in the trenches on 28 February: “The frost began to break and the trenches commenced to fall in, etc. All available men were employed day and night in coping with the water and falls.” Things had not improved by 2 March when the Diary records that “All working parties were employed on pumping and clearing the trenches.” On 20 March 1916, Wells went on leave for an unspecified period, but in late April, presumably after his return, working parties were still employed on “pumping and clearing, day and night”, and the enemy artillery and machine-guns had become noticeably more active.

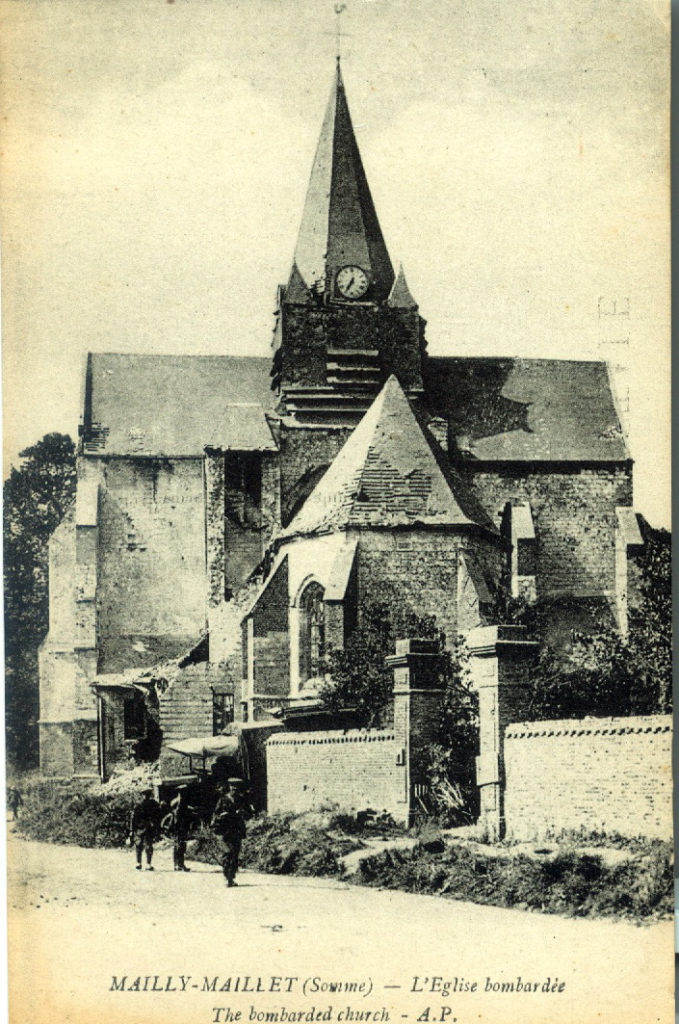

The 1/4th Battalion saw its first real action during the night of 15/16 May: all was quiet until 00.30 hours, when the Germans began a bombardment “of extraordinary violence and accuracy” that was directed at 56th Division’s trenches over to the left of Wells’s Battalion’s, followed by a raid on the Hébuterne trenches that cost it 98 of its number killed, wounded and missing. Wells, who was in the front line, displayed great coolness, visited all his posts during the bombardment, and handled the situation in a very capable manner, for which he was personally congratulated in a letter from the GOC (General Officer Commanding) the 48th Division. On 16 May, the Battalion marched to Couin and then Beauval (18 May), but the men were so fatigued by the recent action, which came at the end of a week in the trenches, that 85 men fell out on the march. The Battalion then stayed out of the trenches for six weeks, training in the St Riquier Training Area, resting in various villages, and finally route marching its way back to Mailly-Maillet, where it prepared for an attack on 1 July that never materialized, causing, according to the War Diary, a considerable sense of disappointment.

On 6 July the Battalion found itself at Sailly, just north of the Albert–Bapaume Road, and from there, two days later, it moved back to Hébuterne, where it still had to contend with water and mud for a week until it moved back to Sailly (13 July) and Senlis (15 July). On 16 July, the Battalion’s Commanding Officer and his Adjutant went to reconnoitre the village of La Boisselle, just to the south of the Albert–Bapaume Road, which had been captured by the 19th Division on 3 July. According to the shocked report in the War Diary of the 1/4th Battalion, the village

was a perfect scene [?] of desolation; the wall of the village was left, the trenches were blown in, all the wire was shot away, and the debris of the battle [was] lying about – dead, equipment, rifles, bombs, kit etc. – the scene was terrible. Our guns had done their work well and the village was completely destroyed. The fortifications of the Germans were wonderful and some idea of the difficulties our attacking troops had to face could be understood.

On 18 July, Wells’s Battalion left Senlis and marched via Couzincourt (18 July) and Albert (19 July) to La Boisselle, where they took up positions on 20 July in the old front line of the German trenches between La Boisselle and Ovillers. Three days later, in the small hours of 23 July, the Germans began to shell the village, counter-attacked at 04.00 hours, and were driven back by 07.00 hours at a cost to the Battalion of 128 of its members killed, wounded and missing; on the following day the shelling recommenced, leaving a further 51 officers and ORs (Other Ranks) killed, wounded and missing, nine of whom were suffering from shell shock. On 25 July, having lost a total of 242 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing during its five days on the Somme front, the Battalion was withdrawn to Albert, and thence to Arqueues (26 July) and Beauval (28 July), where a draft or 96 reinforcements was waiting.

During the march, which was made in temperatures of 75–81 degrees Fahrenheit, 125 exhausted men fell out. The War Diary expressed some considerable doubt about the quality of some of the new arrivals: “Some of the men should not have been sent out: they had not handled a rifle before, only broomsticks; they had not been taught to turn and had no knowledge of a bomb [hand grenade]; many of the elementary points on sanitation were unknown.” Although the diarist then qualified his remarks by saying that they “refer to only a few” of the new men, it is extremely rare to find such opinions being expressed in a War Diary of the time, and these may well be an index of the shortage of trained recruits in England just after the butchery of the first days on the Somme and when conscription had been compulsory in England for less than six months. After resting for two weeks, the Battalion returned to the vicinity of Ovillers on 13 August, where it saw more action on 13, 18 and 27 August and lost a further 355 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing.

Given that it took about two months to train a pilot, Wells probably left the 1/4th Battalion during the second half of May, for on 5 August he was attached to 60 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC), as a Lieutenant. The Squadron had been founded at Gosport, Hampshire, on 30 April 1916, and arrived in France in May 1916 equipped with the single-seat and single-wing Morane-Saulnier N, which was known as the “Bullet” – more because of its shape than because of its speed or ability to climb – and of which only 94 were ever built. The Squadron suffered heavy losses during the Battle of the Somme, and on 24 August 1916 Wells was transferred to 11 Squadron, a unit that had been formed from a nucleus flight of 7 Squadron in January/February 1915. After training at Netheravon, Wiltshire, on the Vickers F[ighter] B[omber] 5, it had become the world’s first fighter squadron when it reached France on 25 July 1915 and was stationed at Vert Galand aerodrome, near Villers-Bretonneux and six miles from Doullens on the road to Amiens. The FB5 was a two-seater (pusher) bi-plane which had first flown on 17 July 1914, and it had a similar configuration to that of the FE2(b) (see A.S. Butler). But as it was powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine, its top speed was between 70 and 75 mph, and by the end of 1915, it, too, was clearly outclassed by the Fokker Eindecker.

Despite this, the Squadron can list a wide range of war-time achievements during its first 15 months in France. During the Battle of Loos in late September 1915, one of its flights was detached to fly long-range reconnaissance missions from Auchel, mainly over Ham, St Quentin and Peronne, c.30 miles behind the front. In mid-November, shortly after Second Lieutenant Gilbert Stuart Martin Insall (1894–1972) had won the VC for his exploits during a mission over Achiet-le-Grand, the Squadron was moved to Bertangles, near Arras, and in January 1916 it was moved yet again, this time to Savy, where it undertook mainly reconnaissance flights over the Douai area. In the same month, one of its members, Captain C. de Crespigny, invented a mounting that would enable the Gunbus to carry two Lewis Guns rather than just one, and another of its members, Lieutenant Norman, invented the highly accurate Norman gun sight. From 7 May 1916 to 23 August 1916, Albert Ball VC (1896–1917), Britain’s top-scoring fighter ace of World War One, was a member of the Squadron.

On 1 March 1916, as part of Trenchard’s organizational reforms (see A.S. Butler), the Squadron was assigned to the British 4th Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson (1864–1925), where it was at first used mainly for air-to-ground cooperation with anti-aircraft units. But at the end of June 1916, just before the start of the Battle of the Somme, the Squadron took part in the RFC’s anti-balloon offensive, equipped with Le Prieur incendiary rockets. On 1 June 1916 it received its first FE2(b)s and by the middle of the month it consisted of one flight of scouts, two flights of FE2(b)s, and one flight of modified Vickers FB5s. But by 24 August 1916, 11 Squadron finally consisted of 18 FE2(b)s, and when Wells arrived, its principal duties were offensive patrolling, photography, and escorting bombers, mainly in the Beaumont Hamel/Gommecourt area. On 1 September the Squadron was moved yet again, this time to Izel-le-Hameau, south-east of Savy.

We do not know what moved Wells to join the RFC, but it may be that like many another RFC volunteer he preferred the high risk of flying to the mud, squalor and ceaseless attrition that he had experienced in the trenches. Whatever the truth may be, the brief period that elapsed between him leaving the Bedfordshire Regiment and becoming operational in the RFC suggests that he became an Observer, not a Pilot. But after only four weeks or so, on 15 September 1916, Wells and Second Lieutenant Frank Edwin Hollingsworth (1891–1916), were reported missing after an offensive patrol over the German lines that involved a dog-fight with 20 enemy machines. Although, after nine months, he was presumed killed in action on the above date, aged 27, the indistinguishable remains of the two men must have been subsequently discovered in the wreck of their machine, for they were originally buried in an isolated grave in Haplincourt Communal Cemetery. In February 1930 they were transferred to a joint grave in the much larger Canadian Cemetery No. 2, Neuville-St Vaast; Graves 10.C.17–18; Wells’s headstone is inscribed “Faithful unto Death” (part of Revelation 2:10). He left £8,306 2s. 7d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Harrow Memorials, iv (1919), unpaginated.

Errington (1922), p. 356.

[Anon.], ‘Colonel B.C. Gardiner’ [obituary], Portsmouth Evening News, no. 17,003 (7 January 1932), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Fraud Conspiracy Alleged: Woman Sent to Prison’, Gloucester Citizen, no. 135 (4 December 1934), p. 8.

O.C.W., ‘George McMullan, M.D., F.R.C.S.Ed.’, British Medical Journal, 21 September 1963, p. 752.

The Biscuit Boys Interval I – 1st/4th (Sept 1915 to June 1916) Page 223. 13

Wood, ‘The artistic family Hayllar’, Connoisseur, 186 (April 1974), 266–73; (May 1974), 2–10.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 47–8, 116, 138–9.

Charlotte Yeldham, ‘Hayllar Family (per. c.1850–c.1900)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 26 (2004), pp. 49–51.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/64.

AIR1/688/21/20/11.

AIR76/538.

J77/3547/4.

RAFM: Casualty Card (Wells, Henry Maurice Watkins).

WO95/2762.

WO339/32721.

WO339/66047.

WO374/73060.