Fact file:

Matriculated: 1912

Born: 12 July 1893

Died: 15 January 1918

Regiment: Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery: XXI.A.3

Family background

b. 12 July 1893 as the only child of Reverend Canon John Nigel Philpott (1859–1932) and Mary Florence Philpott (née Heygate) (1861–1929) (m. 1890). At the time of the 1891 Census Philpott’s parents were living at The Vicarage, Stoke Albany, near Kettering, Northamptonshire (two servants); at the time of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses the family was living at Southchurch Rectory, Southend-on-Sea, Essex (three servants); and at the time of the 1921 Census the family was living at Coleorton Rectory, near Ashby-de-la-Zouch (number of servants unknown).

Holy Trinity Church, Southchurch, Essex

Parents and antecedents

On the whole, most members of Philpott’s family were members of the educated middle class and quite a few of them married well. His father, John Nigel Philpott, was the third son of the Reverend Richard Stamper Philpott (1827–94) and Mary Charlotte Philpott (née Tattersall) (1827–1901) (m. 1851). John Nigel was educated at St Michael’s College, Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire (c.21 miles north-west of Worcester) from c.1872 to 1877, and in 1877 he matriculated at Magdalen College, Oxford, as a Bible Clerk. The term is no longer in use but it seems to have designated an undergraduate whose university education was subsidized by his College in return for his help with chapel services. John Nigel seems to have been an above-average student of Classics until 1881 (BA 1882; MA 1887), after which he trained for the priesthood at Ely Theological College and was ordained deacon in 1882 and priest in 1883. From 1882 to 1890 he was Curate of St George’s Church, Leicester; from 1890 to 1893 he was Rector of Stoke-Albany with Wilbarston, Northamptonshire; from 1893 to 1918 he was Rector of Southchurch, Southend-on-Sea, Essex, where, according to one of his obituarists, “he brought about great improvements […] and watched its population grow from 900 to 5,000”; and from 1918 to 1921 he was Rector of Waldershare with Coldred, Kent, a village about two miles north of Dover. From 1914 to 1918 he was an Honorary Canon of Chelmsford Cathedral and from 1917 to 1918 the Rural Dean of Canewdon and Southend-on-Sea, Essex. In 1921 he resigned his posts in Kent and Essex to become the Rector of Coleorton, Leicestershire, a parish of 520 souls with a gross income of £321 p.a. that was about two miles east of Ashby-de-la-Zouch and in the gift of the Beaumont family, to whom he was related via his mother-in-law Constance Mary (see below). John Nigel was almost certainly presented with the living by the 11th Baronet, Sir George Howland William Beaumont (1881–1933), who, together with his wife, Lady Beaumont (Renee Muriel Northey; c.1903–1987), attended his funeral on 24 February 1932. He left £19,382 12s. 3d.

Mary Florence Philpott, Philpott’s mother, was the daughter of William Unwin Heygate, JP, DL, MP (1825–1902) and Constance Mary Heygate (née Beaumont) (1834–1929) (m. 1852); William Unwin was the second son of Sir William Heygate, 1st Baronet Southend (1782–1844), and Isabella Longdon Heygate (née Mackmurdo) (1796–1859) (m. 1821), the fourth daughter of Edward Longdon Mackmurdo (1756–1817).

William Unwin was educated at Eton College (c.1838–c.1843) and Merton College, Oxford (c.1843–1847), where he read Classics (BA c.1847; MA 1850); after graduation he became a barrister. After standing unsuccessfully as a Conservative candidate for Bridport, Dorset, in 1857, he was elected MP for Leicester (1860–65), for Stamford, Lincolnshire (1868), and finally for South Leicestershire (1870–80). He lived at Roecliffe Hall, Leicestershire, about five miles north-north-west of Leicester, and was prominent in Leicestershire politics all his life, becoming an Alderman on Leicestershire County Council. Besides being a landowner, he was Chairman of Pares’s Leicestershire Banking Company and a Director of the Midland Railway and the Canada Company. As one might expect, he was an active member of the Leicestershire Yeomanry and rose to the rank of Captain.

The Heygates (the family of Philpott’s maternal grandfather) were members of the landed gentry whose estates were mainly in Essex and Suffolk and whose family can be traced back to the sixteenth century. But Sir William Heygate made his fortune from the manufacture of hosiery and later became a successful banker and financier. He prospered to such an extent that he was made Sheriff of the City of London (1811–12) and an Alderman of the City of London (1812–43); he also became its Lord Mayor (1822–23) and, finally, its Chamberlain (1843–44), an office which dates back to 1237 and which nowadays involves quite a number of ceremonial duties but is also still concerned with the financial management of the City of London. From 1818 to 1826 Sir William was the Conservative MP for Sudbury, and the labyrinthine story of his political life is retold in great detail and with great lucidity in Margaret Escott’s brief biography (see Bibliography). After leaving Parliament Sir William led the public campaign to build Southend Pier (1829–33), the longest pleasure pier in the world, so that larger ships carrying passengers or cargoes might enjoy better docking facilities in the shallow waters of the Thames Estuary.

The Beaumont family (the family of Philpott’s maternal grandmother), can be traced back to the 1st Baron Beaumont, Henri de Beaumont (b. before 1280, d. 1340), but the baronetcy, one of four to bear the name Beaumont, goes back to 1658 when Thomas Beaumont (d. 1676) was created 1st Baronet of Stoughton Grange (Leicestershire) as a gesture of thanks for his support of Cromwell during the English Civil War and his contribution to the creation of the New Model Army. Constance Mary Beaumont was the only daughter of Sir George Howland Willoughby Beaumont, 8th Baronet of Stoughton Grange (1799–1845), and Mary Anne Beaumont (later Dame and Lady; née Howley) (b. c.1807, d. 1835 in Hyères, France) (m. 1825), one of the three daughters of the Most Reverend William Howley (1766–1848) (m. 1805), the Archbishop of Canterbury (1828–48, and Philpott’s great-great-grandfather). It was he who presided over the coronation of William IV and Queen Adelaide in 1831 and who, together with the Lord Chamberlain, General Francis Nathaniel Conyngham, the 2nd Marquess Conyngham (1797–1876), went to Kensington Palace on the morning of 20 June 1837 to inform Princess Victoria of her accession to the throne.

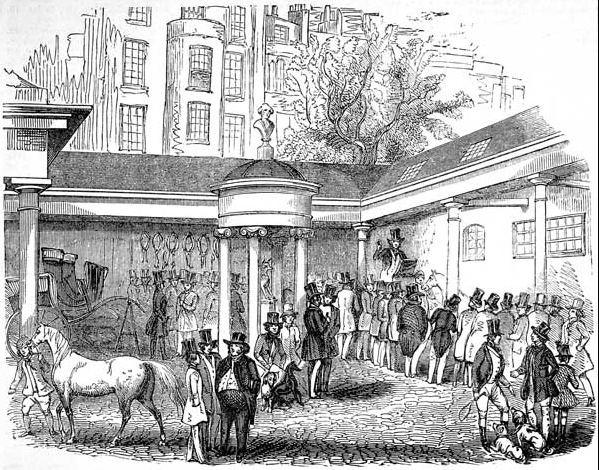

Philpott’s paternal grandfather, the Reverend Richard Stamper Philpott, attended Rugby School (c.1840–c.1847) and then studied at St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, from c.1847 to 1850 (BA 1851; MA 1880). His wife, Mary Charlotte Tattersall, was either a great-granddaughter or granddaughter of Richard Tattersall (1724–95), the founder in 1766 of what became the world’s leading firm of bloodstock auctioneers, whose premises were originally at Hyde Park Corner until they moved to Knightsbridge in 1865. She was also the sister of the artist and architect George Tattersall (1817–49), whose best-known paintings are of horses and hunting scenes and who, as an architect, specialized in kennels, stables and other sporting buildings. Richard Stamper was ordained deacon in 1850 and priest in 1852, and from 1850 to 1858 he was the Curate of Christ Church, Epsom, Surrey, after which he became very active in Somerset. From 1858 to 1862 he was the Vicar of Farrington Gurney with Ston Easton, Somerset; in 1873 he became the Rural Dean of the Midsomer Norton Division of Frome Deanery; from 1879 until his death he was the Prebendary of Compton Bishop in Wells Cathedral; and from 1858 to 1886 he was the Vicar of Chewton Mendip, Somerset, four miles north of Wells, a living with a population of 753 and a stipend of £420 p.a. One obituarist described him as “one of the best known clergymen in the West of England”, and when his widow was buried next to him in the churchyard at Chewton Mendip, her obituarist observed that “much could be written of her many acts of kindness rendered in the village”.

Tattersall’s at Hyde Park Corner in 1842

Richard Stamper and Mary Charlotte Philpott had seven children: four boys and three girls. John Nigel Philpott’s six siblings were:

(1) Richard Courtney (b. 1852, d. 1892 in Brazil);

(2) Mary Grace (1853–1930); later Gibson after her marriage in 1875 to Reverend (later Right Reverend) Edgar Charles Gibson (1848–1924); five sons; she left £14,248 5s. 5d.;

(3) Julia Cazalet (1855–1924); later Hodgkinson after her marriage in 1877 to William Sampson Hodgkinson (later JP; 1847–1925); two sons; she left £3,118 4s. 3d.;

(4) Charles Barrington (b. 1858, d. 1927 in Queensland); married (1886) Constance Lucy Wood (b. 1864, d. 1957), one daughter; she later became Schuchard after her marriage in 1928 to Carl Otto Schuchard (1886–1974);

(5) Rosamund (1861–1950), she left £8,942 17s 1d.;

(6) Henry Goschen (later Captain (RN), OBE; 1866–1935); married (1908) Ethel Anastasia D’Arcy (1883–1980).

Richard Courtney gave his profession as “Merchant’s Clerk” in the 1871 Census and then, probably, emigrated to Brazil.

Edgar Charles Gibson came from a distinguished clerical family which numbered several bishops and one archbishop and he was known as a “fluent speaker”, “forcible preacher”, “effective chairman”, and “an administrator and organizer of remarkable grasp and distinction”. He met Mary Grace when he was Vice-Principal of Wells Theological College, of which he was Principal from 1880 to 1895. From 1905 to 1924 he was the 31st Bishop of Gloucester. He left £7,711 4s. 4d.

In 1856 William Sampson Hodgkinson’s father (also William Sampson Hodgkinson; 1818–76) purchased the ancient, water-powered paper mill at Wookey Hole, Somerset (established 1610), renovated it, and turned it into a very prosperous business. In 1887 William Sampson Hodgkinson junior had Glencot House, an imposing neo-Gothic mansion designed by Sir Ernest George (1839–1922) and Harold Ainsworth Peto (1854–1933) (two of Britain’s foremost architects during the late Victorian period) built nearby as his family’s residence on the banks of the River Axe. By 1910 the mill employed 200 people, Hodgkinson’s Somerset estates were valued at £57,700, and on his death (1927) he left £220,013. After World War Two the mill’s profitability dropped and together with the nearby caves it was acquired in 1973 by the Madame Tussaud Group and turned into a working tourist attraction. It ceased paper production in 2008 and the machinery was sold. According to an obituarist, William Sampson was known as a magistrate for his “extreme kindness of heart” which could, on occasion, be “almost too great”, leading him to deal “too lightly with the cases that came before him”.

Glencot House, near Wookey Hole, Somerset

(copyright Judy Buckingham and licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence)

Julia Cazalet and William Sampson’s two sons were: Gerard William, OBE, MC and Bar (1883–1960); and Ivan Tattersall (1891–1931).

Gerard William Sampson (Philpott’s first cousin), went into the family business but also, like his father, made a name for himself as a first-class cricketer, and served in both world wars. He was the father of Colin (“Hoppy”) Hodgkinson (b. 1920, d. 1996 in the Dordogne, France), the “other” Douglas Bader (1910–82). Having begun training for the Fleet Air Arm in 1938, he was badly burned and lost both legs after being involved in a mid-air collision in 1939. Nevertheless, he returned to flying and shot down two enemy aircraft before making a forced landing in France in November 1943 and spending ten months in Stalag Luft III. He was repatriated but remained a member of the RAF and the Royal Australian Air Force until the early 1960s, and after returning to civilian life he worked in public relations.

Ivan Tattersall Sampson (Philpott’s first cousin), matriculated at Magdalen College, Oxford, in October 1910 intending to read for a Pass Degree in Classics, but left without taking a degree after failing the First Public Examination in Holy Scripture and Greek and Latin in Michaelmas Term, 1911. He served in the Army during World War One, but after the war he emigrated to France, where he devoted himself to the study of French Literature. He was the father of Terence William (1913–99), who also studied at Magdalen (1931–35) and after being awarded a 2nd in PPE became increasingly interested in Art History. During World War Two Terence William worked in military intelligence at Bletchley Park and then began his work in museums. From 1948 to 1974 he worked in increasingly important posts in the Victoria and Albert Museum; from 1974 to 1978 he was Director of the Wallace Collection; from 1978 to 1981 he edited the Burlington Magazine; and from 1981 to 1989 he was a member of the Museums and Galleries Commission. He left his large collection of papers to Magdalen College, Oxford.

Charles Barrington matriculated at Oxford as a non-collegiate student on 25 January 1879, took his BA in 1884, and emigrated to Queensland, Australia, where he met his wife.

Rosamund never married and became a musician (ARCM 1889) and composer, one of whose works was a setting of “Miss Hutchinson’s fine recruiting poem ‘Roll Up’”. She also became a well-known and highly skilled bookbinder who worked from her own firm, the Marigold Bindery, in Tenison Avenue, Cambridge. Before the war, she was also the Honorary Secretary of the local Arts and Crafts Society and provided a major contribution to the Society’s very successful exhibition of May 1914. In 1908 she stood, unsuccessfully, as a candidate for the Petersfield Ward of the Cambridge Town Council, one of the two central wards. From September 1914 she was engaged in war work and became the Honorary Secretary of the Ladies Recruiting and Comforts for Troops Committee, for which, according to a newspaper report, she did the “lion’s share” of its work until September 1916. From Easter to October 1916 she worked in the Land Army, “being one of the first to show the value that educated women could be to the nation in agriculture”. She also assisted as a voluntary worker in the preparation of the National Register, and in October 1916 she accepted a post in the local Recruiting Office, from which she was subsequently transferred to the National Service Department. In June 1917 she accepted the equivalent of a commission in the newly formed Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps and served in France for the duration.

Henry Goschen Philpott became a Royal Naval Officer and on 31 October 1895 was promoted from Midshipman to Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve. He was promoted Lieutenant (RN) on 1 October 1898 and at the time of his marriage he was serving aboard the second-class pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Renown (1897; scrapped in 1914), which had, from 1905 to 1909, been converted into an unarmed royal yacht. On 5 January 1909 he was placed on the Retired List with permission to assume the rank of Commander. On 12 September 1919 he was awarded the OBE “for valuable services as Shipping Intelligence Officer, Devonport” (London Gazette, no. 31,553, 12 September 1919, p. 11,578). He left £2,302 3s. 10s.

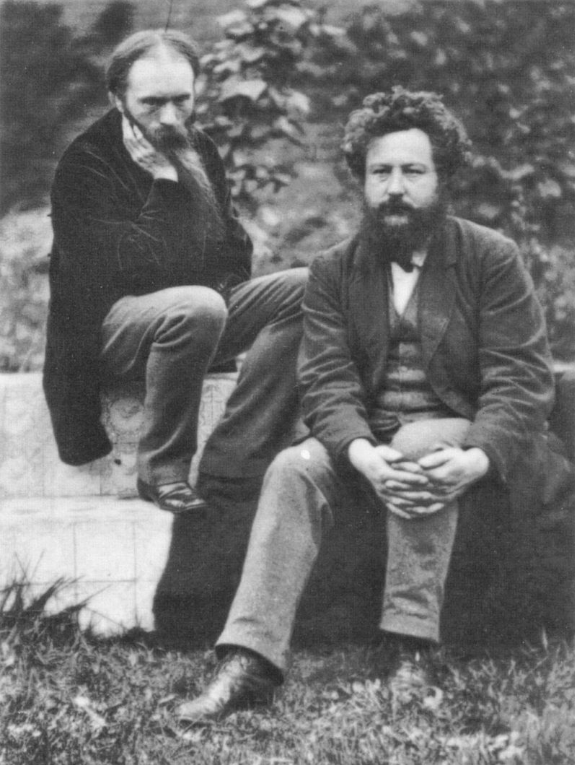

Ethel Anastasia D’Arcy was the youngest child of William Knox D’Arcy (1849–1917) and his first wife Maria Colletta Elena D’Arcy (née Birkbeck) (1848–97) (m. 1872). William Knox made his initial fortune in Queensland, Australia, where he opened a goldmine in 1882 on Ironstone Mount (later Mount Morgan), 24 miles south of Rockhampton. By 1889 the mine was making huge profits and William and his family returned to in 1889, where he acquired expensive property in Grosvenor Square, London, and Stanmore Hall, a Gothic mansion near Edgware, Middlesex, which had been built by the 2nd Duke of Chandos in 1744. William had the house enlarged and its gardens landscaped between 1888 and 1891, and he had its interior decorated with tapestries by William Morris (1834–96) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98), both of whom were associated with the Pre-Raphaelite and the Arts and Crafts movements.

William Morris (1834–96) (right) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) (1877)

But Ethel Anastasia’s father became even richer – not to say one of the richest men in the world – by being one of the principal founders of the oil and petrochemical industry in Persia (now Iran). In 1901, for the sum of £20,000 (c.£1.1 million nowadays), he obtained a 60-year concession from the Shah which allowed him to mine and exploit petroleum and related products throughout the Persian Empire except for five provinces in northern Persia, and he began prospecting in 1903 at a cost to himself of £500,000. At first he had little luck and by 1907 he was nearly bankrupt, but in May 1908 he struck oil at last at a depth of 1,180 feet, and in 1909 he was made Director of the newly-founded Anglo-Persian Oil Company. Partly as a result of his extravagant life-style and predilection for the rich and titled, his fortune diminished somewhat during the final decade of his life: even so, when he died left £984,011 18s. 1d. (£42 million in 2005) and his second wife, Ernestine (“Nina”) Eliza E. Nutting (a widow, née Boucicault) (b. 1866 in Rockhampton, Australia, d. 1949) (m. 1899), left £455,268 4s. 2d. (£10 million in 2005).

Henry Goschen and Ethel Anastasia had a daughter, Rosamond Anastasia (1920–1956) who, in 1942, married Justin Newton Crane (1918–90).

Philpott’s paternal great-grandparents – i.e. Richard Stamper’s parents – were Richard Price Philpott (1803–83) and Emma Stapley Philpott (née) Clowes (1803–78) (m. 1824). Richard Price, like his brother Henry Gray (b. 1830, d. 1880 in Florida) was a surgeon by profession but also a skilled experimenter with electricity and in 1856 he was made the official electrician to the Atlantic Telegraph Company.

Education

From 1902 to 1907, Philpott attended Windlesham House Preparatory School, Brighton, Sussex, England’s first real preparatory school, which became one of the top five English preparatory schools in the nineteenth century (cf. C.A. Pigot-Moodie, H.M.W. Wells, G.B. Lockhart). Founded on the Isle of Wight in 1837, the school moved to Brighton in 1838 and to new buildings in 1846. From here, in December 1906, Philpott obtained a Foundation Scholarship to Marlborough College, where he was a pupil from 1907 to 1912, and while there he joined the Junior Officers’ Training Corps, rising to the rank of Corporal. In his final year there he became a Prefect. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1912, having been exempted from Responsions as he had an Oxford and Cambridge Certificate. He took one part of the First Public Examination, Greek and Latin Literature (Homer, Cicero, Tacitus), in Trinity Term 1913, but sat no more examinations after that and left without taking a degree at the end of Trinity Term 1914 to join the Army. In a letter that President Warren wrote to Philpott’s father in January 1923, he paid his son the following tribute: “I never forget your dear boy – one of the straightest, most dutiful and most loyal we have ever had in his father’s College.”

John Reginald Philpott, MC (1893–1918); photo taken of him sitting at the controls of a Maurice Farman Longhorn trainer, not long after gaining his Royal Aero Club certificate on 5 August 1915

Above: portrait photo probably taken soon after he was awarded the MC (note the ribbon below his wings) on 20 October 1916

Below: probably 1915/1916

Probably soon after he was awarded the MC (note the ribbon below his wings)

War service

Philpott applied for a Temporary Commission on 12 August 1914 and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 7th (Service) Battalion, the Suffolk Regiment, on 28 August 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28.885, 28 August 1914, p. 6,891), a week after it had been formed at Bury St Edmunds on 20 August 1914. He must have applied for a transfer to the newly formed Royal Flying Corps (RFC) fairly soon afterwards, although, officially speaking, he remained part of the 7th Battalion until 3 December 1915, when his official transfer to the RFC went through. At some point in the period before 19 March 1915, when F.R. Charlesworth wrote a letter to his friend Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967) (a pacifist) in which he expressed the hope that Philpott “has not been indulging in any of his nocturnal expeditions with this new wound it might make things serious as you say”, Philpott was either injured in an accident or taken seriously ill, for he had had to undergo extensive treatment in the Great Northern Central Hospital, Holloway Road, London, N7. Despite this incapacity, Philpott’s injury card records that he was promoted Flying Officer (the RFC/RAF equivalent of Lieutenant) on 17 April 1915.

On 31 May 1915, i.e. when Philpott had not yet fully recovered from his medical condition, the 7th Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment had left England from Folkestone and landed in Boulogne on the following day as part of 35th Brigade, in the 12th Division. It then travelled by train to Lumbres, about five miles south-west of St-Omer, and marched a mile north-westwards to Acquin, where it trained for about a week before route-marching roughly 20 miles northwards to the small town of Nieppe, five miles west of Armentières and just below the frontier with Belgium. And by early August, when Philpott had recovered but was still in England, the 7th Battalion was either in billets near or actually in the trenches at Ploegsteert, a couple of miles away across the frontier in Belgium. So despite his continuing attachment to the 7th Battalion, Philpott never served with it on the Continent and was, incidentally, never mentioned in its War Diary. And just to complicate matters further, although Philpott learned to fly during an uncertain period some time after leaving hospital, his Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate, no. 1,536, dated 5 August 1915, has him affiliated to the 10th (Reserve) Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment. This was based in Bury St Edmund’s, Suffolk, and then Colchester, Essex, from April 1915 until spring 1916. But this apparent puzzle simply indicates that when the 7th Battalion went overseas on active service, Philpott, who had not yet returned to any form of active service, had to be assigned to another unit for administrative reasons and so was nominally transferred to another Battalion of his parent Regiment that was on Home Service.

A Hall Biplane: it consisted of the wing structure and undercarriage from a Caudron G.II that had been affixed to a new fuselage and tail unit. By the end of 1915, 35 pilots, including Philpott, had qualified in it

On 8 August 1915 Philpott gained his basic flying qualification on a Hall Biplane at John Lawrence Hall’s (1891–1920) Flying School that had been opened at Hendon aerodrome, Middlesex, on 17 September 1912, the day that Hall gained his basic flying qualification on a Blériot Monoplane. The government bought the School in 1916/17, enabling Hall to become an instructor in the Royal Naval Air Service and live in some style after the war. But during the war Hall became addicted to morphine and he died of an overdose on Christmas Day 1920 in the Imperial Hotel, Russell Square, London.

John Lawrence Hall (1891–1920)

Soon after completing his basic training, Philpott reported for duty with the 3rd Reserve/Training Squadron at Shoreham-on-Sea, Sussex, and on 14 August, while relaxing there as Duty Officer, he wrote a letter to his Oxford friend, Victor Murray, in which he described in some detail the point of his being there:

This is a school for officers when they first get transferred from their regiments to the R.F.C. […] We consist of about 30 officers, 18 machines, and air-mechanics and motor transport to match […]. We have about 12 machines for instruction purposes and half a dozen for repelling hostile attacks, etc., to be used by the instructors, who are all instructors back from the R.F.C. at the front.

He was also greatly enjoying his time on the course, describing it as “altogether, a delightful summer holiday!” and continuing:

We have lectures on engines, rigging, dropping bombs and things, and one takes down notes and has collections [Oxford parlance for informal termly examinations which are sat in College] on Gnôme [80 hp rotary] engines [produced under licence in Britain and Germany and used on a wide variety of early aircraft] just as one did on the Pseudo-Isidorian decretals!

A.S. Butler was on the same course about three months after Philpott and it seems to have lasted two weeks. Although it is not completely clear what happened to Philpott after he had completed the Shoreham course, it seems almost certain that he underwent a more advanced course of flying training on the (now disused) airfield at Stoke Albany, near Kettering, Northamptonshire, the village where his father had been Rector in the early 1890s before Philpott was born. Either way, he learnt to fly Martinsydes, Blériots and Avros. Then, in November 1915, he obtained his “wings” from the RFC, and on 4 December 1915, after he had completed a long course at the RFC’s Central Flying School at Upavon, Wiltshire, he graduated as a qualified Flight Commander and was formally gazetted as a Flying Officer in the RFC on the same day. On 16 December 1915 he was allocated as an officer to 12 Squadron, RFC, founded at Netheravon, Wiltshire, in February 1915. Although very few records concerning 12 Squadron’s early history have survived (in which there is no mention of Philpott until January 1916), two independent sources date its move to France as 4 September 1915 and its arrival at St-Omer in the Pas de Calais as part of 12 Wing, 3 Brigade RFC, as 6 September 1915. But neither source mentions Philpott by name or includes him on its list of officers, and this fits in well with his injury card and obituary in The Times, according to which he embarked for France on 15 December 1915 and reported for duty with 12 Squadron at St-Omer soon afterwards.

Philpott standing by a B.E.2 (c) or (d) (1915/16)

According to 12 Squadron’s official history, “its early duties consisted mainly of patrols around St-Omer and reconnaissance missions, but during the Battle of Loos [25 September–13 October 1915], when vigorous bombing commenced, the Squadron played its part”. It was a long-range reconnaissance and bomber squadron flying a variety of aircraft that included the slow but stable twin-seat “pusher” F(ighter) E(xperimental) 2(b) and 2(d) and the twin-seat “tractor” B(omber) E(xperimental) 2(c) and 2(d), the latter variant being a dual-control version of the 2(c). These aircraft were so stable that pilots could centre their controls and let the aircraft fly itself but they lacked manoeuvrability and so were easy targets for the new generation of German scout aircraft whose machine-guns were synchronized to fire through the propellor. On 28 February 1916 the Squadron moved its base to Vert Galand (astride the N25 about five miles south of the crossroads town of Doullens); in March 1916 it moved to Avesnes-le-Comte (11 miles west of Arras); on 9 May 1917 it moved to Wagonlieu (just west of Arras); and on 7 July 1917 it moved to Ablainzevelle (eight miles south of Arras), where it began to re-equip with the significantly faster but less stable R(econnaisance) E(xperimental) 8, which had a top speed of 101 mph and a faster climb rate than its predecessors.

We do not know exactly what Philpott did during his first six months with 12 Squadron, but bad weather would have kept its aircraft on the ground to a significant extent. So it is not surprising that its Daily Routine Orders book for January and February 1916 record that he acted as the Squadron’s Orderly Officer on 1 and 11 February 1916 and as the “Officer i/c School” on 13 February 1916. But on 24 June 1916, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Air Vice-Marshal) Philip Game (1876–1961), one of Major-General Trenchard’s most senior staff officers, with a very distinguished (and controversial) future ahead of him, sent Philpott’s Commanding Officer an official letter in which he asked for Philpott to be informed “that the GOC [i.e. Trenchard, who commanded the RFC in France from Summer 1915 to early 1918 and laid great stress on inter-service co-operation and the tactical use of aircraft] considers his first attempt at trench photography […] extremely creditable. The panorama will be submitted to G.H.Q.” We also know that from 6 to 14 July 1916 Philpott was away from the Squadron on leave, that on 21 July 1916 his BE2(d) was damaged by rifle fire during a bombing raid on the railway station and aerodrome at Aubigny-au-Bac, halfway between Cambrai and Douai, and that it was damaged for the second time at about the same time by anti-aircraft fire when it was over St-Léger, about seven miles south of Arras.

On 7 October 1916 he was made Acting Flight Commander and promoted Acting Captain (London Gazette, no. 29,792, 20 October 1916, p. 10,081), and two weeks later, on 20 October 1916, he was awarded the MC “for his conspicuous gallantry and skill” on 21 July 1916” (LG, no. 29,793, 20 October 1916, p. 10,189; see below) and the “great gallantry” which Philpott, who was generally regarded as “a particularly good pilot”, had displayed on previous occasions. He repeated the performance on 15 September 1916, when the Squadron was required to bomb Bapaume station, and here is how Philpott’s comrade Raymond Money describes what occurred:

There was argument as to who should carry 20-pound bombs and who should have those of 112 pounds. We carried either nine of the former, or two of the latter. We preferred the big ones, because they made such a glorious splash. Three machines had big ones and Philpott and myself were two of them. I had not been very successful with the bomb sight, so went low to drop mine. Philpott always went low. Even then I missed the line with the first bomb, but got a siding and some wagons. I dropped the second [one] fair and squarely, and was just pulling up and round when I saw a machine dive on the station and drop a big bomb from about fifty feet. ‘Philpott’ thought I, and envied him the magnificent demolition of the station buildings. Our targets had been carefully allotted, to save waste.

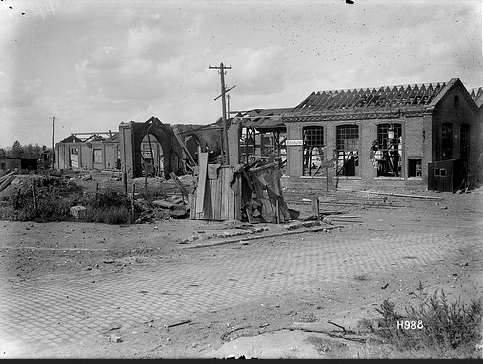

Bapaume Station (1918)

12 Squadron allowed Philpott a further period of leave from 19 to 29 November 1916 that was extended to 11 December 1916 for reasons that are unknown and might have been medical in origin. Then on 9 January 1917 he was either wounded or injured or succumbed to medical problems, and by 13 January 1917 he was hospitalized in England once more and had been struck off the strength of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), an indication that he was not expected to return to duty quickly. After his discharge from hospital, he was given five months’ medical leave or home service in England, during which he gave F.R. Charlesworth, another of his Oxford friends, his first experience of powered flight. Because of this leave, Philpott could have missed much of the Battle of Arras (9 April–16 May 1917), when the Squadron did “splendid work all through the Battle […] in the face of great opposition” i.e. during “Bloody April”, when, despite the RFC’s numerical superiority, the tactical, technical and training differences between the two Air Forces meant that the RFC suffered losses that were nearly four times higher than those of the German Luftstreitkräfte. But there is a discrepancy between the circumstances described above and what is recorded in 12 Squadron’s weekly returns for night flying between September 1916 and June 1917. For here it is clearly stated that Philpott began to practise night landings on 25 February 1917 and mastered the art so rapidly that he was able to act as Instructor on 26 February, 28 February, 27 March, 28 March, 30 March, and 4 April, and during the Battle of Arras itself on 30 April, 2 May, 6 May and 9 May. So, one wonders whether Philpott – who, as the following passage by Raymond Money tells us, was not given to unnecessary resting – returned unofficially from his leave in England in order to help train its pilots in a necessary skill during a particularly difficult period, and whether this bit of well-meaning insubordination caused the military authorities to decide that it was time for his quirky resourcefulness and undoubted ability as a pilot to be used elsewhere.

Before Philpott left No. 12 Squadron, Raymond Money left a graphic and amusing pen portrait of his friend’s idiosyncratic style:

There were many cheerful idiots in the Squadron, but the chief of them was Philpott. He was one of the bravest men I have ever met. He would not go home for a rest and he could not be kept on our own side of the lines. He was bad enough when in company with an observer, but when we started the sole bombing game, he was in his element. With no-one’s skin to think about except his own, he went down low every time to drop his bombs and trail his coat hopefully. If a Hun came and attacked him, he said: “Thank you very much, old sport, it’s no fun without you”, and engaged him in battle. When we flew the B.E.’s solo[,] we mounted a Lewis gun between the mainplanes – the idea being that you flew the machine sideways at the enemy. It sounds ridiculous, but it was the best we could do. If you picture a Leyland lorry, armed with one Lewis gun, fixed and to be fired sideways by the driver, taking on a Rolls-Royce armoured car with the usual gunner and circular-mounted Vickers gun, you will have a good idea of the odds between a solo B.E. and the average German two-seater. That is the sort of thing that Philpott enjoyed! On one occasion he returned more than usually shot about, and said that he had had a good scrap until his gun jammed; then, as he bolted for the lines, and Fritz continued to pour bullets into his machine, he had become angry, and turned round and shouted “Pop-pop yourself, you ——– fool!” We quite believed it. Tyson [Eric James Tyson; 1892–1918] was almost as bad. He was not the cheerful idiot off duty that Philpott was, nor did he seek unequal combat so blithely, but when it came (and there was plenty of it!) he sailed in with relish. These two between them shot down and destroyed an enemy aircraft on September 13th, and the fact was confirmed independently. Tyson was wounded, and went, very reluctantly, to hospital. It was the culmination of much brilliant, courageous, and valuable work; and in spite of serious obstacles, both pilots were eventually given Military Crosses. Tyson came out again later, as a Squadron Commander [of No. 5 Squadron, with the rank of Temporary Captain], I believe, and was killed [12 March 1918, aged 24]; Philpott went out east as a Flight-Commander and died as a prisoner of war in Turkish hands [see below].

Tyson was awarded both the MC (London Gazette, no. 29,793, 20 October 1916, p. 10,193) and the DSO (LG, no. 30,466, 8 January 1918, p. 568), and his citation for the former – which almost certainly refers to the events of 13 September 1916 – reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and skill during bombing raids. Descending to about 300 feet under heavy fire of all descriptions, he succeeded in wrecking a train. Whilst doing this he was attacked by other hostile machines, which he beat off with the assistance of Lt. Philpott, in another machine. Although wounded and with [his] engine severely damaged[,] he attacked with Lt. Philpott a group of men who were endeavouring to start a hostile machine, and scattered them in all directions. His machine was riddled with bullets.

The citation for Philpott’s MC complements Tyson’s and reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and skill in descending to about 300 feet, under heavy fire of all descriptions, in order to bomb a train. Finding that Capt. Tyson had wrecked the train, he dropped his bombs on a station and then assisted him to beat off hostile machines. He then, with Capt. Tyson, attacked a machine which was endeavouring to leave the ground.

Philpott in the rear cockpit of an FE2(b) (1916), which came into squadron service with the RFC in August/early September 1916

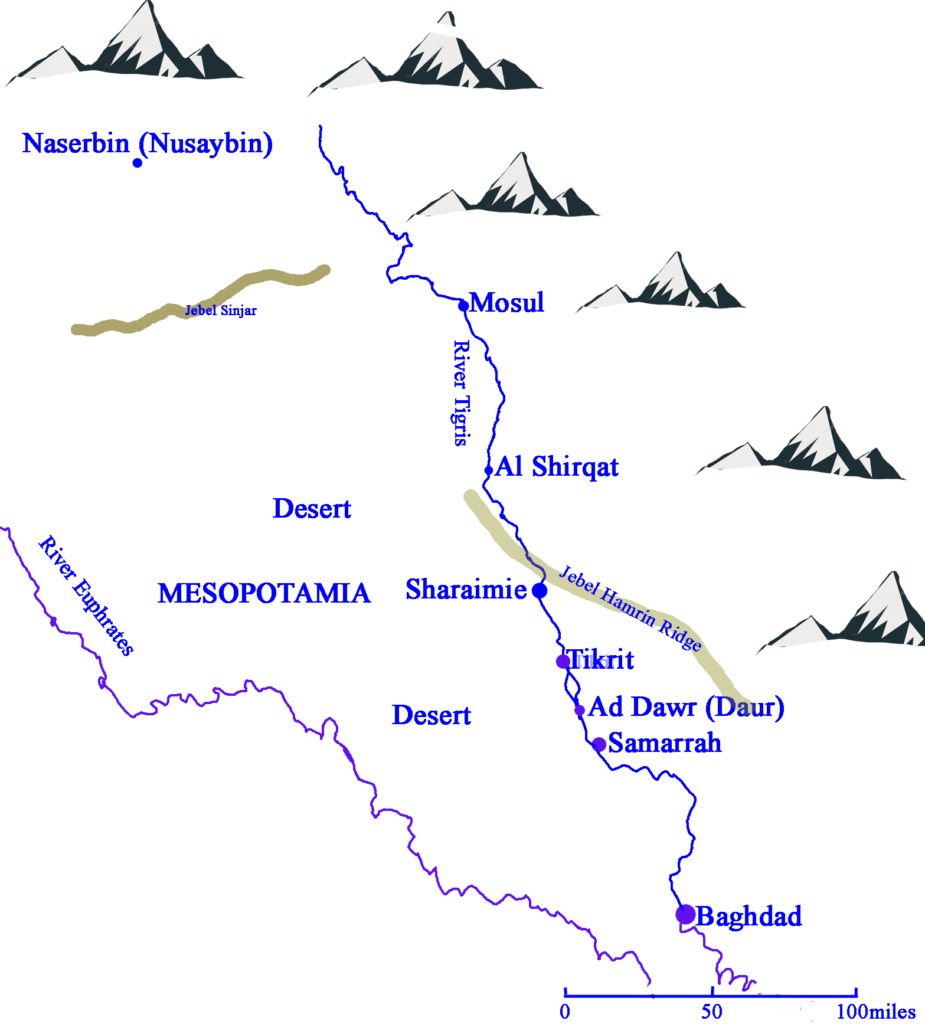

Meanwhile, in another theatre of war, the disastrous and humiliating siege of Kut-al-Amara, situated on a huge bend in the River Tigris, had lasted from 7 December 1915 to 29 April 1916 and culminated in the surrender of the city’s entire Anglo-Indian garrison, some 14,000 men. The siege had also cost the lives of c.23,000 Allied troops killed, wounded and missing in the course of several futile rescue attempts (see R.P. Dunn-Pattison). But in late July 1916, Sir Percy Lake (1855–1940), the GOC (General Officer Commanding) Allied forces in Mesopotamia (the modern-day Iraq), was replaced by the younger Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude (1864–1917), who had made himself a name as an effective divisional commander on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Maude set about re-establishing, re-constituting and reinforcing the Allied forces that were now under his command, and once this had been done and the weather had cooled down, he successfully renewed Allied attempts to advance up the River Tigris and recaptured Kut-al-Amara on 25 February 1917, Baghdad on 11 March 1917 and the ancient city of Samarra, 78 miles north of Baghdad, on 24 April 1917.

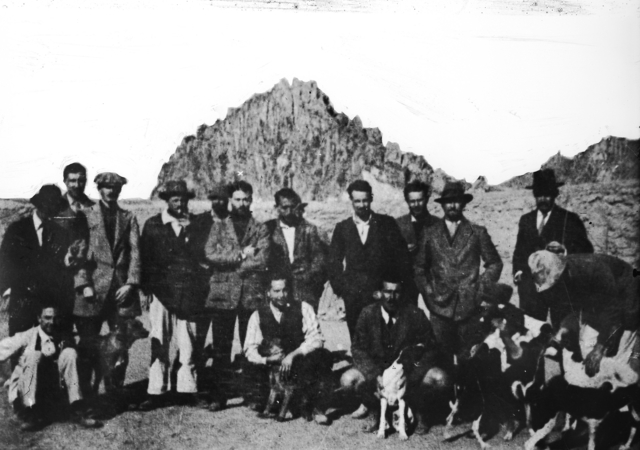

No. 63 Squadron with an R.E.8, probably taken in mid-June 1917, just before its departure for Mesopotamia. Philpott may be in the very back row, holding onto the aircraft’s bracing wires

As part of the strategic plan for Mesopotamia, it was decided to reinforce 30 Squadron, RFC, the only squadron to have operated in Mesopotamia since the beginning of the war there in 1914, with 63 Squadron, RFC. This unit had been formed at Stirling on 31 August 1916 and moved to Cramlington, nine miles north of Newcastle-on-Tyne, at the end of October 1916, where it served as a training unit for about seven months using various kinds of obsolescent aircraft, until it was finally issued with the 2-seater, water-cooled D.H.4. It was intended that the Squadron should move to France and operate with the British Expeditionary Force as a day-bomber squadron. But on 13 June 1917, about ten days before it was due to relocate and its size was due to be increased from 12 to 18 machines, the Squadron was re-assigned to the Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force and re-equipped with the R.E.8., which, being fitted with an air-cooled engine, was far more suitable for operating in hot climates than was the D.H.4 with its water-cooled engine.

Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8

Philpott had joined 63 Squadron in Cramlington as the Commanding Officer of ‘A’ Flight by 21 February 1917, for that was the day on which, as far as one can tell from the Squadron’s sketchy log-books, he appeared there for the first time. On that occasion he made three brief flights – either solo or as an instructor – and from then on, he flew from Cramlingon fairly frequently in that capacity until the middle/end of May 1917. It must have been about this time that the Canadian Harold Warnica Price (1896–1975), a dentist in Toronto before the war, got to know Philpott. Price had arrived at Liverpool on the SS Olympic on 21 November 1916, trained at the School of Military Aeronautics, Reading, in Berkshire, and become a pilot in 63 Squadron on or about 23 May 1917, when he made up from Pilot Officer to Flying Officer. When, on 2 June 1917, he mentioned Philpott in his diary for the first time, he made it clear how glad he was to be a member of Philpott’s Flight.

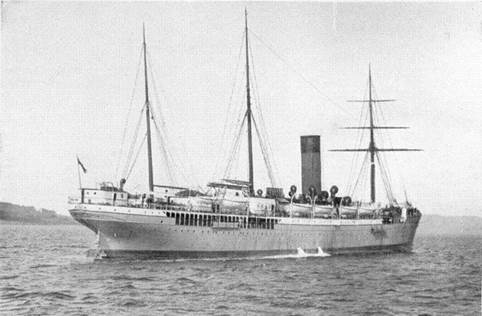

RMS Dunvegan Castle (1896–1926)

Three weeks later, on 23 June, the Squadron sailed from Devonport for Mesopotamia aboard the RMS Dunvegan Castle (1896; scrapped 1926), and after short stops at Cape Town and Durban, it disembarked at Basrah, at the mouth of the River Tigris, on 13 August 1917. There it was awaited by a difficult and uncertain military situation where fighting was going on on two or three fronts and over large distances, and in which it would be difficult for an incoming RFC unit to find its proper role. The Squadron History described it as follows:

To the East on the Di[y]ala Front the 3rd Indian Army Corps held the fringe of the Persian Hills, with two flights of No. 30 Squadron at Baqubah [c.30 miles north-east of Baghdad]; whilst on the Euphrates our advance extended to Ramadi [in central Iraq, some 70 miles north-east of Baghdad]; with the remaining Flight of No. 30 Squadron at Feluja [Fallujah, c.43 miles west of Baghdad on the Euphrates]. The better Machines were those of the enemy; faster in speed and climb to the [B.E.]2C’s, [B.E.]2E’s, Martinsydes and Bristol Scouts with which the Flying Corps in this Country had hitherto been equipped. In this situation anything in the nature of offensive work against the enemy Machines was out of the question; and although no opportunity of engaging him was ever allowed to pass, it is safe to say that as a whole, his reconnaissance work was not seriously interfered with.

Once on shore, the men of No. 63 Squadron would need to undergo a period of acclimatization lasting several weeks. But that process was far more difficult for new arrivals in Mesopotamia than it was for new arrivals in Egypt. Looking back on the weeks when he was at Basrah awaiting the arrival there of No. 63 Squadron, Lieutenant-Colonel John Edward Tennant, MC, DSO (1890–1941), the Officer Commanding air operations in Mesopotamia since 1916, and therefore the Commanding Officer of 31st Wing, of which No. 63 Squadron would form a part, left a vivid account of the hell that was Basrah, on the Persian Gulf, where new troops arrived:

Everyone at the Base [at Basrah] seemed more dead than alive, and it was impossible to get anything done. There was little use going to bed at nights; we would search the harbour in a motor-boat for a region of cooler air without success; everything was damp, for the wind blew off the Gulf. After a few fitful moments of sleep between midnight and 4 a.m. one would wake up feeling like a wet rag, and perhaps take a motor-bicycle out into the desert, away from the river, in quest of a cool breath. There was none. By eight the thermometer was back over the 100, and at breakfast the same wag would daily play ‘The End of a Perfect Day’ on the gramophone. We were issued with large Japanese parasols to keep our helmets cool. A British officer presented a comic sight in shirt-sleeves, shorts, blue goggles, a large helmet, a spine pad, and over all a huge parasol! It was with looks of longing that one watched the great white hospital ships gliding down the harbour with their cargoes of wrecked humanity bidding farewell to this benighted country for ever. […] After a week at the base I was glad to get away up-country again for the drier atmosphere of the desert. But a fortnight later I once more left Baghdad, this time by air to meet No. 63 Squadron on its arrival from England. […] It was a hard test for a youngster to arrive straight from England into such a climate. Till they arrived in port[,] the health of the Squadron had been excellent, but the Basrah climate immediately drove 50 percent into hospital; two died of heat-stroke within the first few days […] they arrived with a morale superb, ready to finish the war. But climate had been out of their reckoning, and by the time I arrived[,] the remaining half had mostly succumbed. Of thirty officers only six remained, and of two hundred odd men[,] only seventy. This remnant was lying on its back at Aircraft Park, and even those who could stand up were badly shaken. I had feared such a débâcle. Basrah was doing its “damndest” to destroy humanity […] There was practically no evaporation in the air, and it is by evaporation that humans retain their normal temperature. […] with dismay I read the medical reports of some being invalided out of the country and others seriously ill; malaria, dysentery, sand-fly fever and heat-stroke had taken a heavy toll.

Sand-fly fever was also known as pappataci fever, and caused tiredness, stomach upsets, high temperatures up to 106 degrees, a fast heart-rate and severe aches in the head and joints. But heat-stroke was even worse and Tennant cautioned: “There is no time to waste in heat-stroke; a man fit and well will be suddenly seized; and if he is not better [he] is dead within two or three hours” (cf. P.J.T. Blakeway). The History of No. 63 Squadron confirms Tennant’s account, and while it records that an insect bite was not usually lethal and that the medical situation gradually improved with time, it records: “at one time practically the whole of the Squadron were in Hospital, three men died and over 30 of all ranks, including the Technical Sergeant-Major, were invalided to India”.

It was intended that No. 63 Squadron should be the Corps Squadron of the 1st Indian Army Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Stanhope Cobbe, VC (1870–1931). But it was soon discovered that offensive work out of the aerodrome at Tanouma, on the bank of the Tigris opposite Basrah, was out of the question for three reasons. First, the delay because of the widespread sickness; second, many of the Squadron’s R.E.8’s had been warped by the long sea voyage with the result that their wings and fuselages needed to be completely stripped for repair and 70% of their propellers had developed split laminations, having been packed on damp cork and enclosed in air-tight, tin-lined cases; and third, the Turks were already equipped with superior, German-made machines. So although the medical situation improved on 12 September 1917, when the temperature dropped to a mere 113 degrees Fahrenheit, allowing No. 63 Squadron “to take on a new lease of life” and its aircraft to be assembled gradually on the Aircraft Park at Basrah and equipped with a new, albeit unfamiliar type of carburettor that was more attuned to desert conditions, it was not until 20 September that the first two repaired R.E.8’s – with Philpott as one of the pilots – were ready to ferry Major-General Sir Arthur Reginald Hoskins (1871–1931), the GOC 3rd (Indian) Division, 400 miles flight north-north-westwards to military aerodromes near the front. This now lay between Samarrah and Saur, c.27 miles to the north of Baghdad on the River Tigris. Indeed, it took until 30 October 1917 for all the Squadron’s 12 aircraft to depart for Baghdad, two of which were lost in a sandstorm en route. And when the first aircraft arrived at the Squadron’s new base at Samarrah, it was soon realized that this had been badly designed, since it was located at first in the south-east corner of the Camp with all its hangars facing in the same direction, causing them to receive the full force of the prevailing north-west wind.

Moreover, by the time that No. 63 Squadron had arrived in northern Iraq, the Turks were starting to withdraw north-westwards towards Turkey from a front line in the spring of 1917 that was roughly 100 miles north-west of Baghdad and in the general area of the cities of Tikrit and Daur. This meant that a no-man’s-land of c.80 miles was gradually developing between Samarrah and Tikrit, so that the Squadron’s reconnaissance missions, which lasted an average of three-and-a-half hours, had to be flown over practically waterless desert, with the river banks of the Tigris inhabited by hostile Arabs whose willingness to help Allied pilots after forced landings was a “very doubtful quantity”. As Philpott was one of the first pilots to arrive at Baghdad, he was detailed to go on the Squadron’s first reconnaissance mission from there, with Corporal O.N. Grant as his Observer and his close friend Lieutenant Malcolm Glassford Begg, MC and Bar (b. 1896 in Argentina, d. 1969) – with whom he had shared a cabin on the voyage to Mesopotamia – as his wingman, and Lieutenant Edward Noel Baillon (b. 1895, d. 1971 in Dunham, Quebec) as Begg’s Observer. Begg, who had been educated at Marlborough College, Wiltshire, and studied Medicine at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, had originally served in the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Rifle Brigade, and landed in France on 14 October 1915. But he transferred to the RFC, and while serving as a pilot in 63 Squadron won the MC twice, on 22 September 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,760, 22 September 1916, p. 9,271) and 14 November 1916 (LG, no. 29,824, 14 December 1916, p. 11,083). Baillon had attested on 22 March 1915 and served as a Private in the 11th Canadian Rifles before transferring to the RFC in order to train as an Observer.

The two R.E.8’s took off from Samarrah at 07.30 hours 25 September 1917, crossed the lines at Daur at 7,000 feet, and flew northwards as far as the Jebel Hamrin ridge, the rough dividing line between Arabic-speaking and Kurdish-speaking Iraq, before turning round in order to fly the 60 or so miles back to the Allied lines. When passing over Tikrit aerodrome, Begg threw down a bag containing an Iron Cross marked by long coloured streamers that belonged to a German officer who had been taken prisoner and had since died. But when the flight noticed a single-seat Halberstadt D.II of the Ottoman Air Force at about their own height, they climbed to get the advantage of height, and then, with Begg in front on the right and Philpott just behind him on the left, dived towards it firing their machine-guns at intervals.

A Halberstadt D.II

But during the dive, Begg noticed that his machine was doing between 115 and 120 mph, a dangerously fast speed, and after firing around 25 rounds of tracer which seemed to hit the Halberstadt’s fuselage, he heard a crash and felt his aircraft shudder. At first he thought that an anti-aircraft shell had burst right above him, but on looking up he was “horrified” to see that his top wing had snapped off the struts on both sides of his aircraft’s fuselage right up to the main struts so that the two halves of the wing were tending to fold backwards. At first, Begg thought that it was “all over” with them, but at a height of 5,000 feet managed, nevertheless, to raise his aircraft’s nose and then tried to fly it straight and level by using just the joy-stick and throttling forward as far as possible. Although this worked for a while, enabling Begg to turn in the direction of Samarrah with Philpott still behind him, he saw as he did so the Halberstadt land in the desert just outside Tikrit aerodrome. But Begg also soon discovered that despite his best efforts, his R.E.8 was losing height so rapidly that he would not be able to reach the Allied lines. So with fabric and broken bits of wood streaming backwards for ten feet from both halves of the damaged upper wing, he managed to land and avoid the nearby Turkish camp by pushing his joy-stick hard over to the left and side-slipping, left lower wing first, onto the aerodrome itself, where it slewed round and finished up with its engine buried in the earth a few yards from a terrified Bedouin shepherd. Incredibly, Begg and Baillon survived the landing virtually unharmed, but they had been shaken up “pretty badly” by what was, in fact, a barely controlled fall through the air, and they were very downhearted at the thought of becoming prisoners-of-war on their very first operational sortie in Mespotamia.

Flying Officer Malcolm Glassford Begg, MC and Bar (1896–1969)

They were soon taken prisoner by a party of Turkish soldiers led by an officer on horseback, who, like all educated Turkish officers, spoke good French, prevented one of his men from stealing Begg’s watch, and provided horses on which the two British airmen could ride back under escort to the Turkish camp. Meanwhile, Philpott had tried to land and pick them up, but when he was at 2,000 feet, his engine, which had had starting problems at take-off that morning, refused to open up. The problem worsened, and watched by Begg and Baillon, Philpott was forced to land in a depression in the desert about two miles away, and although he tried to taxi he was prevented from doing so when large numbers of Turkish soldiers started to snipe at them. So he and Grant got out of the aircraft, tried to set it on fire, and surrendered to men of the Turkish 3rd Regiment, who took possession of the R.E.8 and managed to extinguish the blaze. On the following day the Turks got the machine flying again, giving rise to the story, which the four British flyers would hear in mid-October while in captivity in Mosul, that they had landed their two aircraft unnecessarily out of sheer “funk”. At the Turkish camp, the two crews were examined by a doctor and allowed, much to their relief, to meet up after their ordeal. Philpott was even permitted to write a letter to his Colonel – which all four men then signed – in which he briefly explained what had happened, asked him to wire the news to their respective parents, and stressed the kindness of the Turkish Staff. The letter, which still exists in the RAF Museum at Hendon, was probably dropped behind the British lines by a Turkish pilot as a gesture of courtesy for Begg’s earlier return of the German prisoner’s Iron Cross.

As soon as he was taken prisoner, Begg, assisted by Philpott, started to keep a diary and commented:

The Turkish general treated us with the greatest of courtesy. We were offered tea and cigarettes and then drove in a typical German open exhaust car to Corps HQ where we were splendidly entertained by aide de camp Capt Kemmal [recte Quemal]. Wonderful lunch coffee and tea. Although we were quite near the aerodrome[,] none of them came to see us but we learnt that our Halberstadt pilot (i) was on his first Halb[erstadt] solo [and] (ii) had his engine done in. In the evening we were questioned in turn by a man who talked English fairly well. We were lucky in having some money given us (though it cost Begg his black flying cap [ – which was worth considerably more]). We spent the night in a large tent with two [armed] sentries inside it [and two more outside it]. Plenty of blankets. A disappointing day as we both failed through pure bad luck; the Halb[erstadt] not firing a shot. All the same a most marvellous escape.

Corporal Grant, apparently, stood up particularly well to the questioning and “filled up” the intelligence officer “with a lot of rot”. On the following day the four men were taken under guard in small springless mule carts to the Turkish Divisional HQ at Sharaimie where they were interviewed by “a charming General”, examined once more by doctors, fed well, and treated more like guests than prisoners.

After staying at Sharaimie for another day, on 29 September 1917 they set off along the Tigris on donkeys at the head of a convoy of sick Turkish officers and men, with Grant showing signs of some kind of fever. On 30 September the column, commanded by an Arab Captain who was openly anti-Turkish, left the Jebel Hamrin ridge on its right, paused during the heat of the day, and spent a bright moon-lit night at the entrance to the pass leading to Al-Shirqat, about 50 miles north of Tikrit. They set off on 1 October just before dawn and “crossed a range of hills, full of ‘wadis’ and ‘nullahs’ and finally reached the Shirkat mountains from the top of which we saw the river again and the camp and the old ruins of Shirkat”. In the evening they continued northwards by lorry and at 15.15 hours on 3 October they arrived at Mosul, 143 miles north of Tikrit, where they had to spend time in a cell with Arab and Turk criminals before Grant was taken to hospital and the three officers to a rest billet. On 4 October they encountered men from the Cheshire Regiment (probably the 8th (Service) Battalion) and the South Wales Borderers (probably the 4th (Service) Battalion) who had been captured during the fighting on the River Tigris of April 1916 (see Dunn-Pattison). Begg’s diary reads: “They were in a dreadful state in rags, absolute skeletons and their wounds most crudely dealt with. It was pitiful to see them. We tried to get the Turks to let them come up country with us. I heard afterwards that one or two died on their trek through the desert.” On 5 October the four flyers met three more infantrymen who had been captured in April 1916: “They had had their tunics, puttees and boots taken away from them. No complaints of Turkish treatment but surgery extremely primitive. No anaesthetics.”

On the same day Philpott wrote a card to his parents in which he said “I am extraordinarily well treated & quite happy […]. Whatever you do, don’t worry. Because I’m having a priceless time and have never felt so well! I mean it. The Turks are charming and speak French!” And when, on that day, the four flyers learnt that the German pilot who had “brought them down” had been awarded the Iron Cross First Class for his feat, they “wrote and congratulated him” – with a certain amount of irony, one imagines, given that he had not fired a shot! They later learnt that he was in hospital in Mosul having subsequently crashed Philpott’s machine while on a test flight, and tried, unsuccessfully, to get permission to visit him. But despite his wish to make a positive impression on his parents and, presumably, keep his own spirits up by doing so, during the night of 5/6 October Philpott began to shows incipient signs that all might not be well with him, and Begg’s diary reads: “All slept rather restlessly and Phil woke the others up again by talking, whimpering and scrabbling.” He did the same on the following two nights.

Mosul coffee house (1917–18)

Sketch map of journey from Tikrit to Naserbin; names of places as given in the diary

As was normal in the Middle Eastern theatre of war, the three officers were, on the whole, treated well by their Turkish captors during their stay in Mosul. They lived in a house, possibly on parole, with Corporal Grant acting unofficially as their batman, and they survived reasonably well on a diet of bread (mainly stale), fruit (mainly water-melons), raisins, tea and the occasional egg, supplemented by extras that they purchased with money sent across by their friends and families back home. But on 10 October, Begg noted in his diary:

We are beginning to feel rather rotten and weak through always being kept lying in our room all day – also it is very stuffy at night on account of the distressing proximity of the local sanitary arrangements. We are also finding that we are getting enough to eat – not because we get sufficient food but probably because we take no exercise.

On 11 October the officers were told that Corporal Grant had “left today on foot to Naserbin [Nusaybin, 167 miles to the west] with native and Russian prisoners”. They did not see him again until they met up in England after the war, but they somehow heard that he had made

a very fine attempt to escape across the desert with six other men, and after very nearly perishing from hunger and thirst was recaptured by the Turks. Later he was put in charge of a petrol engine and by an ingenious method of wangling extra petrol and selling it at a fabulous price to an Armenian, he managed to do himself really well and came out of the country with £100 Turkish notes in his pocket.

On 12 October the three officers managed to buy a pack of cards with which to pass the time – “a great resource” and a “godsend” – since the evenings were beginning to draw out and their supply of pastimes was, at best, limited – mainly singing and debating difficult religious and political problems without sufficient information at their disposal and trying to get a glimpse of the girls in the “harem” on the other side of the street. On 14 October 1917 Philpott wrote a second card to his parents: “Very fit and happy & really excellent fun”, but four days later, after several days of boredom and inactivity, the diary’s author tersely remarked: “Very cold and Phil ill”. But then, almost unexpectedly, at 04.00 hours on the following day they were loaded into lorries and began driving westwards, and by 15.00 hours they had reached Ouenatte, “a square mud building with a few scattered tents”, where they met “some French Colonial troops who were taken prisoner in France in 1914 and [had] marched a part of the way to this country. They had experienced a dreadful time. Were very pleased when we gave them a few raisins as they never got anything except flour or bread with a very occasional bit of meat.” The diary then added: “Phil rather worse today”. By Saturday 20 October it had become very clear that Philpott’s condition was worsening significantly, for the diary reads: “Phil had a very bad night. Suspect dysentery”, and by midday, when the convoy reached Demi Carpi (Iron Gate), where the three officers had a chance to wash and bathe in “a topping stream”, the author added that Philpott was “very bad today”. So the other two consulted the doctor “who said it was dysentery but wanted him to get on to Naserbin”. Philpott went to bed early, but the other two men were entertained very well by the French-speaking Turkish officers:

Started with hors d’oeuvres and arak, much talk, more arak, more talk. Very good crowd, about 9 o’clock as we had been sitting about two hours we thought this must be our dinner so after various whispers and nudgings between Begg and Baillon, Begg suggested going. We were dissuaded and a few minutes afterwards we went in to another tent for dinner. We discussed young officers, languages and how Turkey made war […]. Went back to our tent quite unescorted and feeling very happy. (The effect of arak after not having tasted any alcohol for a considerable time.)

But during the night of 20/21 October, Begg was very sick – probably because of the unaccustomed quantity and quality of the food on the previous evening – and on 21 October Philpott was in such a bad state that the Turks decided to take him to Nusaybin, “a very old desert town with green grass and trees, a most refreshing sight, […] and a very good hospital”. The journey there should have taken three hours but the road was so bad that it took double that time. Begg and Baillon had asked to be allowed to stay with Philpott, but their request was refused and they left him with a man from the Cheshire Regiment who saw to his kit and got him to the German Hospital. “We saw a lot of Kut prisoners here also some from the Dardanelles. All working on the railways. The Indian troops were very well dressed and looked well (which is more than can be said for the British troops).”

Selimiye Mosque, Konya (1558)

(Photo from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selimiye_Mosque,_Konya)

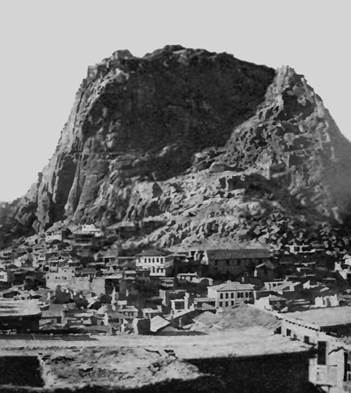

Philpott’s two friends never saw him again and spent the next ten days being transported several hundred miles to the parole camp for officers at Gedos (Kédos), on the Black Sea (northern) coast of Turkey, via Tel el Halif, Aleppo (northern Syria), Bozanti (Turkey), Konya (Turkey) and Afion Kara Hissar (Turkey). During their long journey the two officers were treated well: they were fed well; they were allowed to take a Turkish bath in Bozanti – where the attendants removed an “enormous” amount of dirt and the two Englishmen were more than a little taken aback by the amorous frolics of two elderly Turks; and in Konya they were able to visit the magnificent Selimiye Mosque (1558) and to converse freely with three French civilian prisoners, one of whom told them that he had seen thousands of Armenians massacred in northern Syria. The diary finishes with Begg’s entry of 2 November 1917. In contrast, from Nusaybin, Philpott was eventually taken to the prisoner of war camp at Afion Kara Hissar, in western Turkey, 125 miles north of Antalya, where he died of dysentery in the camp hospital on 15 January 1918, aged 24, and where he was temporarily buried in the Armenian Cemetery, just east of the town. In c.1927 his remains, like those of most other Allied combatants who were buried in remote sites in Iraq and Turkey, were transferred to Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery; Grave XXI.A.3 (currently administered by the British Embassy, who will not allow anyone in to take photographs).

The Kara Hissar, with the Armenian church just to the right of the large white building at the foot of the crag in the centre of the picture

Philpott’s original grave in the Armenian Cemetery, Afion Kara Hissar, Turkey

Afion Kara Hissar was the largest collection point for Australian and British prisoners, and the author John Still (1880–1941), who had been captured on Gallipoli on 9 August 1915 and spent three years and 84 days in the camp there, painted shocking pictures of its conditions in his memoirs (1920). Philpott’s last winter there was particularly harsh, and although officers were treated significantly better than other ranks for a price, he would have experienced the extremely harsh regime under one particularly sadistic camp Commandant called Maslûm Bey (dates unknown). And Still’s description of the camp’s primitive medical facilities also suggests that Philpott’s early death was hastened by conditions in the hospital:

[The appearance of the unhappy men from Kut-el-Amara when they reached Afion in the months following April 1916] is vividly remembered by the prisoners who were already there. Some of them naked, many half out of their minds with exhaustion, most of them rotten with dysentery, this band of survivors was received with deep sympathy by the rest, who did all they might to restore them, small as their own resources were. In very many cases it was too late. The sick men were placed in the camp hospital; but this was a hospital in not much more than the name, for though there was a Turkish doctor in attendance, with some rough Turkish orderlies, medicines were non-existent, and a man too ill to look after himself had a very poor chance. Deaths were frequent; the dead were buried by their comrades in the Christian cemetery of the town. All this time, close at hand, there was a party of British officers imprisoned at Afion, two of whom were officers of the medical service. Yet all communication between officers and men was flatly forbidden, under heavy penalty, throughout the bad time of 1916 and even later. English doctors had thus to wait inactive, knowing that the men were dying almost daily, a few yards off, for mere want of proper care.

Colonel Tennant later referred to “Poor Philpott” as “a most magnificent, cheerful, devil-may-care fellow, with a wonderful record from France”, and the History of No. 63 Squadron records that: the sad news “was received with very real regret by all who had known him”, adding that the loss of Capt[ain] Philpott “was a severe blow”, not least because Captain Philpott

was a pilot of exceptional ability, whose example had been of inestimable advantage to the Squadron. His ability as a pilot may be gauged from the following fact. There was a time in England when R.E.8’s were regarded with a certain amount of suspicion by new or inexperienced pilots [because of their alleged tendency to spin and stall]. Capt[ain] Philpott was elected by the Authorities to fly R.E.8’s and very quickly dispelled this suspicion by showing what the machine was capable of in the Air [sic]. That he was entirely successful goes without saying; his manipulation of the R.E.8. is still [in 1919] a topic of conversation in the Squadron, and to him must be given the chief credit for the confidence with which the machines were regarded by the pilots in these early days of Service Flying.

On 6 February 1918, Begg wrote a letter to Philpott’s father from Kédos in which he said: “Phil., as we called him, was the most popular man in the squadron. He was absolutely fearless in flying and nobody could wish for a better companion on any work over the lines. When I was in France[,] I heard of his work out there and I know he fully deserved the V.C. he was recommended for when he got his M.C.” But the slowness of the post from the Turkish prisoner of war camps probably meant that Begg’s letter had not reached Philpott’s family by 16 February 1918, when they finally heard of their son’s death, or even by the time that his death was confirmed by a letter from the Red Cross dated 26 February 1918.

After Philpott’s death ‘A’ Flight of No. 63 Squadron was renamed ‘Scout Flight’ and equipped with two Bristol Scouts, two SPADs & three Martinsydes, which gave the Squadron a much-needed superiority in the air over their Turkish opponents. Both Begg and Baillon survived their captivity. Begg was demobilized on 16 December 1918 and went back to the Argentine to work with his father in the meat trade, but returned to Britain in 1928 and became a stockbroker. During World War Two he served for three years in Balloon Command and in 1942 became the Air Attaché in Dublin. He left the RAF with the rank of Wing Commander and resumed his former work in the City. Baillon, who was demobilized on the same day as Begg, had emigrated to Canada in 1912 where he became a bank clerk; he returned to Canada, where he became an apple farmer. Philpott is commemorated in the Memorial Hall, Marlborough College; on a memorial plaque in Chelmsford Cathedral which lists the names of the sons of clergy of the Chelmsford Diocese who were killed in action in World War One; on the War Memorial in Holy Trinity Church, Southchurch; and on a huge Memorial Window in the Nave of the same church that was consecrated on 10 November 1920. He left £3,594 1s 4d.

Australian and British prisoners at Afion Kara Hissar

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

**‘The Diary of one Day: Capt. Malcolm G. Begg, MC RFC’, Cross and Cockade (The Journal of the British Society of World War I Aero Historians), 11, no. 2 (1980), pp. 66–7.

**‘The Diary of Three Officers in the Hands of the Turks’, ibid., pp. 68–75.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Death of Prebendary Philpott’ [obituary], The Globe, no. 30, 970 (8 September 1894), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Funeral of Mrs Philpott’, Shepton Mallet Journal, no. 2,304 (24 May 1901), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Mr William Unwin Heygate’ [obituary], The Times, no. 36,706 (4 March 1902), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘A Notable Australian Wedding’, The Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Queensland), no. 13,017 (19 July 1906), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Commission for Cambridge Lady’, Cambridge Daily News, no. 9,011 (23 June 1917), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Captain John Reginald Philpott’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,720 (22 February 1918), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘John Reginald Philpott’ [obituary], The Marlburian, 53, no. 784 (4 April 1918), p. 46.

[Anon.], ‘Sad Story of a Sheffield Airman’s Death: Mysterious Affair’, The Sheffield Independent, no. 20,679 (31 December 1920), p. 5.

John Still, A Prisoner in Turkey (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1920), pp. xiv–xv, xxi, 197–202.

John Edward Tennant, In the Clouds above Baghdad: Being the Records of an Air Commander (London: Oakley House, 1920), p. 4, 75–9, 181–2, 188–9, 190–5.

[Anon.], ‘Airman’s Sad Death from Morphine: Forged Prescriptions?’, The Sheffield Independent, no. 20,698 (22 January 1921), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The Magdalen Cross’ [photo], The Times, no. 42,640 (9 February 1921), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Bishop Gibson’, The Times, no. 43,596 (10 March 1924), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘The Rev. J.N. Philpott’ [obituary], The Times, no. 46,066 (25 February 1932), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘The Rev. John Nigel Philpott’ [obituary], The Chelmsford Chronicle, no. 8,737 (26 February 1932), p. 7.

Raymond Money, Flying and Soldiering: Autobiographical Reminiscences (London: Nicholson & Watson, 1936), pp. 11, 81–5.

J.M. Bruce, ‘Hall School Biplane’, in: British Aeroplanes: 1914–1918, 2nd impression (London: Putnam & Co., 1967), p. 265.

Morris (1967), p. 23.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 47–8, 116, 138–9.

Brereton Greenhous (ed.), A Rattle of Pebbles: The First World War Diaries of Two Canadian Airmen (Ottawa: The Canadian Government Publishing Centre, 1987), pp. 213–357 (The Diary of Harold Warnica Price (1896–1975), who served with 63 Squadron in Mesopotamia as a member of Philpott’s ‘A’ Flight). Available on line at www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/his/docs/Pebbles.pdf.

Wray Vamplew, ‘Tattersall Family’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 53 (2004), pp. 527–8.

Dancey (2005), pp. 1–6.

Hal Giblin and Norman Franks, The Military Cross to Flying Personnel of Great Britain and the Empire 1914–1919 (London: Savannah Publications, 2008), pp. 485–6.

Archival sources:

MCA: CP/9/6 (Mark book for Classics students [10/11 February 1877])

MCA: PR 32/C/3/955 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to J.R. Philpott [February 1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/80.

RAFM: Casualty Cards (Begg, Malcolm Glassford and Philpott, John Reginald).

RAFM: AC97/127 (The Papers of Wing Commander Malcolm Glassford Begg and Captain John Reginald Philpott [1914–c.1965]).

RAFM: AC1997/127 (Malcolm Glassford Begg, The Diary of One Day: 25th Sept. 1917 [Typescript of four pages].

The Murray Papers, Liddle Collection, Leeds University: CO 066 (File 5). Contains: one letter from Philpott to Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967) of 14 August 1915.

ADM 196/137/113.

AIR 1/166/15/151/1.

AIR 1/408/15/238/1.

AIR 1/688/21/20/12.

AIR 1/1874/204/220/4.

AIR 1/1875/204/220/11.

AIR 1/1875/204/220/12.

AIR1/2250/209/48/1.

WO95/1852.

WO95/4315.

WO339/12037.

WO339/78455 (Harold Warnica Price).

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Beaumont Baronets’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaumont_baronets (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Bloody April’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloody_April (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Edward Burne-Jones’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Burne-Jones (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Fall of Baghdad (1917)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fall_of_Baghdad_(1917) (accessed 18 August 2018).

North-East Aviation Research (Mick Davis). ‘Cramlington Aerodrome’: https://www.nelsam.org.uk/NEAR/Airfields/Histories/Cramlington.htm (accessed 18 August 2018).

Margaret Escott, ‘Heygate, William (1782–1844) …’, taken from the printed version of The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1820–1832, ed. D.R. Fisher (Cambridge: CUP, 2009): http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/heygate-william-1782-1844 (accessed 18 August 2018).

Michael Skeet, ‘RFC Pilot Training’ (3 December 1998) (13-page essay on-line in The Aerodrome Forum which, however, mainly concentrates on the years 1917–18): http://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/showthread.php?t=23225 (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Ottoman Aviation Squadrons’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_Aviation_Squadrons (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Philip Game’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Game (accessed 18 August 2018).

Fibiwiki, ‘Prisoners of the Turks (First World War)’: https://wiki.fibis.org/w/Prisoners_of_the_Turks_(First_World_War) (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Siege of Kut’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Kut (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘William Knox D’Arcy’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Knox_D%27Arcy (accessed 18 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘William Unwin Heygate’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Unwin_Heygate (accessed 18 August 2018).

Brereton Greenhous, ‘A Rattle of Pebbles: The First World War Diaries of Two Canadian Airmen’: www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/his/docs/Pebbles.pdf (accessed 18 August 2018).