Fact file:

Matriculated : 1912

Born: 7 January 1894

Died: 18 September 1918

Regiment: Montgomeryshire and Welsh Horse Yeomanry.

Grave/Memorial: Doingt Communal Cemetery (Extension): I.A.23

Family background

b. 7 January 1894 as the elder son (second child) of Basil Arthur Charlesworth (later JP) (1866–1925) and Helen Lilian Royds Charlesworth (née Greene) (1871–1943) (m. 1891) (later Fowler after her marriage in 1925 to Major Ernest George Fowler (1875–1950). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living in Walsworth House, Hitchin, Hertfordshire (eight servants); by the time of the 1911 Census it had moved to Gunton Hall, Lowestoft, Suffolk (eight servants).

Parents and antecedents

Charlesworth’s father, Basil Arthur, was the son of (Wallace) Frederick Charlesworth (1829–1903), a member of the Stock Exchange. Basil Arthur read for a Pass Degree at Magdalen from 1884 to 1887 (BA 1887; MA 1891) and was called to the Bar (Inner Temple) in 1894. He practised for a while as a barrister and became a JP in 1901.

Charlesworth’s mother was the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Greene (1780–1860), the scion of a Nonconformist Bedfordshire family of prosperous tradesmen and the founder, probably in 1806, of the increasingly successful Westgate Brewery in the market town of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. In 1825, thanks to the deaths of a childless neighbour, Sir Patrick Blake (c.1768–1818), 2nd Baronet, and his widow, Lady Maria Charlotte Blake (née Phipps) (1772–c.1823), Benjamin acquired a half-share in their two estates at Nicola Town, St Kitts, and on Montserrat, both in the West Indies, and became the manager of their other estates on the two West Indian islands and in Suffolk. His new prosperity enabled him to acquire the ultra-Tory Bury and Suffolk Herald in June 1828, which he then used to promote free trade in beer and oppose the Reform Act (1832) and the Slavery Abolition Bill (1833).

In 1836 Benjamin, whose interests were now focused on his estates in the West Indies and “the great whirl of London commerce”, left Bury St Edmunds. So from that year, Edward Greene, JP (1815–91), Benjamin’s third son and a shrewd businessman who had entered the family brewery when he was only 13 and recognized that breweries “were judged by their beer and its price”, was left to run the Westgate Brewery on his own. So between 1842 and 1870, a period when beer drinking was growing in popularity, brewing was becoming more of an applied science, and ordinary people were becoming better off, he expanded the family firm into one of the most successful brewing concerns in Britain. Whereas the family plantations in the West Indies went into decline after Benjamin’s death, Greene’s Westgate Brewery flourished, and it increased its production from 2,000 barrels in 1836 to 40,000 in 1875. On 1 June 1887, for a complex of economic reasons that are admirably unravelled by Richard G. Wilson in his history of Greene King (see below), the Westgate Brewery merged with Fred(erick) William King’s (1828–1917) equally successful Bury brewery in order to form a new company. The two had been in increasingly fierce competition, especially over the acquisition of tied houses, since the foundation of King’s brewery in 1868. With a capitalisation of £555,000 and 148 tied houses, Greene King was one of the largest of England’s regional brewers.

Besides being a respected Suffolk entrepreneur, Edward had been an assiduous and very popular Conservative MP for Bury St Edmunds from 1865 to 1885 and, despite his years and worsening health, for North-West Suffolk from 1886 to 1891. He was known in East Anglia for his simple low church religiosity, capacity for hard work, plain speaking, fairness, integrity, generous support of local charitable causes, and paternalist concern for his workers and their living conditions, and at Westminster for his short speeches, party loyalty, and old-fashioned manners. A modernizing farmer since the beginning of his interest in agriculture in 1854, he experimented with new crops and breeds, invested heavily in modern machinery, and was involved in the financing and building of the Bury to Thetford railway that was completed in 1876. Edward’s one recreation was hunting, which he took as seriously as his work, and he became the Master of the Suffolk Hunt from 1871 to 1875. His only son (with his first wife, Emily Greene, née Smythies; 1820–48; m. 1840) was (Edward) Walter Greene, JP (1st Baronet in 1900; 1842–1920). Walter became a partner in the family firm in 1862 and was its Director from 1891 to 1920, although he was far less interested in its success and far more interested in field sports than was his father. Walter unsuccessfully contested the by-election in North-West Suffolk that was caused by his father’s death in 1891, but when he stood a second time, this time for Bury St Edmunds, in the general election of 1900, he was elected unopposed. He stepped down at the general election of 1906. In 1864, Walter married Anne Elizabeth Royds (1842–1912), and they became the parents of Helen Lilian Royds Greene, Charlesworth’s mother.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Kathleen Agatha (1892–1967); later Domville after her marriage in 1912 to Lieutenant James Henry Domville, RN (5th Baronet from 1904; 1890–1919); two daughters;

(2) Julian Basil (1899–1971); married (m. 1924) Sybil Isolda Prideaux-Brune (1894–1960); in 1934, after this marriage was dissolved, he married Sybil Maud Meiklejohn (1895–1971); one daughter.

Sir James and Lady Domville

The Sketch 19 May 1915 p 12

James Domville was the son of Admiral Sir William Cecil Henry Domville, GCB, GCVO (1849–1904), 4th Baronet, and a professional naval officer who entered the Navy as a cadet in 1906. He was commissioned Sub-Lieutenant on 30 April 1909 and Lieutenant on 30 December 1911, but resigned his Commission on 19 June 1912. He was recalled on the outbreak of war and on 1 May 1915 he distinguished himself during the Battle off Noordhinder Bank while commanding a group of four armed trawlers (top speed of 7 knots and armed with one 3-pounder gun) that were attacked by two of Germany’s latest motor torpedo boats (top speed of 30 knots and armed with two torpedoes and one 4-pounder gun each). Instead of trying to run, the armed trawlers courageously engaged the two German vessels, having taken the precaution of calling out four L-Class destroyers from Harwich which soon arrived on the scene, sank the German craft after an hour-long battle, and inflicted heavy casualties in the process. Domville later became the Captain of a destroyer, but having always been of a nervous disposition, his health was badly affected by his service in the Mediterranean and he began to show signs of mental instability (neurasthenia) in 1916. He was discharged from hospital on 21 May 1918, but after the war he became acutely depressed and finally suicidal, and his state of mind was worsened by debt to the tune of £11,629 and domestic problems. In September 1919 he shot himself in the head with a service revolver in his London club and died in hospital on the following day.

Julian Basil described himself as an engineer. During World War One he joined the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) on 4 April 1917, just after his eighteenth birthday, signed up for two years’ service on 27 September 1917, transferred on 22 February 1918 to the Machine Gun Corps – probably the Section that had taken over the RNAS’s Armoured Car Division – and was promoted Sergeant on 22 March 1918. He embarked at Southampton for Mesopotamia on 16 May 1918 and disembarked on 14 July 1918 at Basra, where he was hospitalized from 16 July to 14 September 1918. Two weeks later he was hospitalized once again, in the field, suffering from debility. These dates indicate that Julian did not, contrary to what his father suggested in his letter of 7 October 1918 to Charlesworth’s close friend Victor Albert Murray (see below), see action in the Caucasus while serving in the 39th Company of the Machine Gun Corps. This unit consisted of three armoured cars and was part of Dunsterforce, the 1,000 or so British troops under the command of Major-General Lionel Dunsterville (1865–1946) who were tasked with the capture of oil-rich Baku between late June and mid-September 1918. The attempt failed, and after being besieged in Baku, it was forced to withdraw southwards having lost c.200 of its members killed, wounded and missing. Julian was discharged from the Army on 12 April 1919.

Sybil Isolda Prideaux-Brune was the great-niece of Edward Greene’s second wife, Caroline Dorothy Prideaux-Brune (1827–1912) (m. 1870), the widow of an Admiral and a member of a Cornish land-owning family.

Fiancée

According to a letter from Charlesworth’s father to President Warren of 23 September 1918, Charlesworth had been “long-devoted” to his fiancée, to whom he had become engaged on about 20 August 1918, while on leave in England for 14 days. Her name was Florence Maud Mary Winter (1892–1969) and she was the daughter of Major Harrie Sewallis Winter (b. 1869, d. 1935 in Los Angeles, California), Royal Garrison Artillery, and Minnie Charlotte Winter (née Bryan; c.1869–1947) (m. 1891), marriage dissolved in 1920. By the time of the 1911 Census, Harrie had retired from the Army and become a manager in a shipping company. At the time of the same Census, Florence Maud described herself as an art student and was still living with her father, brother and one servant at “Drayton”, Hoyle Road, Hoylake, Cheshire. In the 1920s, Harrie moved to the USA, where, in 1928, he married Jean Shacklett Brightwell, daughter of Fernando Brightwell and N. Shoemaker, in Los Angeles, California.

In 1925 Florence Maud Mary Winter became the second wife of Major Robert Clerke Burton (1878–1962), who had served in the Central India Horse.

Education

Charlesworth attended Suffield Park Preparatory School, Cromer, Norfolk (cf. R.G.H. Copeman), from 1903 to 1906 and then Eton College from 1907 to 1910. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1912, having taken Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1911. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1913, but left without taking a degree in early 1915. His Eton obituarist wrote of him:

a quiet and unassuming boy, he suffered at times from ill-health, but while not of the robust physique that gains a boy distinction in games, his obvious kindness and unselfishness won him close friendships with boys more athletic than himself, and he left the record of a boy of singularly high character. That he would be liked at the University was certain.

President Warren described him as “truly a young Knight of God” since:

he was indeed amiable, good, chivalrous, gallant, gentle, but brave as brave […] I shall not forget how dutifully he worked, despite at one time drawbacks of health. How resolute he was in finding an opening for service of his king and country!

Raymond Frederick Charlesworth

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

War service

Charlesworth was in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps, and by 19 March 1915, when he wrote the first of the five letters that are preserved in the Liddle Collection to his friend Victor Albert Murray (1890–1967), he was already taking steps to break off his studies and join “in this most Christian game of organized murder & suicide to say nothing of the destructive & wasteful habit of destroying property etc.!” Murray, it should be noted, was not only a committed pacifist who would appear before a military tribunal in 1916, but also General Secretary of the Oxford University Students’ Christian Union, and a prospective Secretary of the Student Christian Movement of Great Britain and Ireland. Charlesworth, who came from a fairly conventional family, had, while still an undergraduate, been deeply influenced by Murray’s pacifism.

Judging by Charlesworth’s first three surviving letters to Murray, his loyalties and conscience were now deeply torn by the war, for, as he wrote to Murray, he really couldn’t “make the business out at all”, being on the one hand “absolutely convinced” by the preaching of the Christian pacifist and campaigner for women’s rights Maude Royden (1876–1956), and on the other overwhelmed by the impression made on him by “all these magnificent men who are going to fight for the safety of their homes & mothers & sisters & Miss Doones” and by “the [irresisitible] appeal of such splendid self-sacrifice[:] how can it be wrong?” Moreover, Charlesworth continued, he also felt “that these new officers (& men) are quite different to the ordinary soldiers – they joined, not from any wish for fighting or glory (as a rule) but because it seemed to them that it had to be done & that it was their duty”. This perception then led him to resist the propaganda being spread by the press and state: “the new armies are not thirsting for the blood of the Germans, as the papers want us to believe, but I don’t think they will be any the less brave or effective all the same” – a rare observation by a young scion of the pre-war establishment whose home life, as he wrote to Murray on 1 April 1915, was one of “gloomy routine”. Charlesworth’s riven attitude towards the war emerged for a second time in his first surviving letter to Murray when he wrote that whilst, “of course, there are some [members of the new armies] who find the ‘white feather brigade’ irresistible, like myself”, he then added the caveat that he did not think that many of them were “inflamed by such considerations” in the way that he was; and he ended this section of his letter by tacitly admitting the contradictions that plagued him: “Enough of this bilge, please excuse it & burn this absurd letter.”

Charlesworth would, it seems, have liked to be commissioned in the Army Service Corps, but had decided against this “as my people seem very much against it, because apparently the officers are not all absolute gentlemen” – an attitude which Charlesworth called “beastly” while adding resignedly “but I suppose they know best”, another implicit admission of his thrall to convention. So, on 14 May 1915 he was officially gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 1/1st Montgomeryshire and Welsh Horse Yeomanry (Territorial Force), a more respectable mounted unit that had been founded on 4 August 1914 at Welshpool as part of the South Wales Mounted Brigade. But a second letter to Murray – dated 1 April 1915, written from ghost-infested Blickling Hall, near Aylsham, Norfolk – indicates that by that date he had “booked his ticket for hell” at least one week previously, and suggests that he had opted for a Yeomanry Regiment because their standards of visual acuity were allegedly lower than those of other Regiments – presumably because so many Yeomanry units were used for home defence.

Despite his pacifist reservations, Charlesworth soon began to enjoy life in his bit of the Army. He told Murray that army life had enabled him to get through “the horrible uncertain stage” and allowed him to do nothing “but work & live in the present which isn’t half bad”; he described his officer colleagues as “a priceless lot […] who would make even hell quite cheerful”; he viewed his men as “mostly quite nice […], small men but very keen & efficient” and added that “being Welsh[,] they have only about 4 names between them viz. Jones, Evans, Roberts etc.”; he was ironic about his gradual progress as a horseman, the danger posed by Blickling’s rabbit holes, and his embarrassment at “swanking about in gaiters & spurs being saluted at every step”; he defined, with prophetic irony, “one of the chief and most necessary accomplishments of an officer” not as any obviously military virtue but as “the power of being cheerful under all circumstances!”; and he was amused by the stories about the ghost of Anne Boleyn “who will keep carting her head about under her arm all over the house, especially in the room next to this”, and wryly conceded that although he had not yet met her himself, “those who have say she is sweet, though her decapitated condition must rather have affected her looks one would have thought”. But towards the end of his letter the ironic enjoyment of his situation cedes to the critical–pacifist side of his personality and he writes, with some passion and without taking back what he has written by calling it “bilge”:

Really I think the world has gone mad, or is it the beginning of the end of the world as many people think? It seems too tragic that men cannot enjoy this beautiful world without blowing each other to pieces, and with what object? How much better it would be if all the people in the world would combine to fight the real evils of mankind rather than wasting their strength in this suicidal quarrel among those who ought to be friends. It is really most annoying, and it will retard human progress like anything, I’m afraid, and the waste is too heartrending – think of the good that might have been done in the world with the thousands of millions of pounds which are being thrown away. However it’s no good crying over spilt milk & I’ve told Graham [ Richard Brockbank Graham (1893–1957), another Magdalen pacifist who became a leading conscientious objector to conscription in 1916 ] to see that it doesn’t occur again!

On 29 June 1915, when Charlesworth’s unit was still at Blickling, he found time to write a third letter to Murray, which starts chattily but works up to the following, emphatic conclusion:

You’re right – about human nature & I believe the only job worth doing is something in the service of others. This job would be quite good if it wasn’t for the awful tragedy on which it is based – I’m now a convinced pacifist, – but not a word or I’ll be shot at dawn!

In September 1915, after completing its training in Blickling Park and Thetford, the Brigade became part of the 1st Mounted Division at Holt, in north Norfolk, and in November 1915 it became a dismounted infantry unit.

On 3 March 1916 Charlesworth’s Regiment, consisting of 24 officers and 448 other ranks (ORs), marched to Cromer, where it entrained for Plymouth, and on 4 March 1916 it set sail from Devonport in the SS Arcadian (1899, sunk by a U-Boat near Milos on 15 April 1917 en route from Salonika to Alexandria). The Regiment arrived at Alexandria on 13 March, where it became part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), formed on 10 March 1916 and commanded until 28/29 June 1917 by General Sir Archibald Murray (1860–1945) (see below). On the following day the Regiment travelled by train to Beni Salama Camp, on the western edge of the Nile Delta and c.40 miles north-west of Cairo. Here, on 20 March 1916, the Regiment joined the Welsh Border Mounted Brigade to form the 4th Dismounted Brigade in the Allied Western Frontier Force (WFF), and here, from 5 April to 22 May, after the requisite period of acclimatization, it trained in infantry skills, mainly musketry. On 26 May the Regiment left for El Azzab, where it did more training until 11 November 1916 and so took no part in the Battle of Romani (3–5 August 1916), to the east of the River Nile just north of Katia, when the Allied Eastern Frontier Force effectively drove the advancing Turks out of the Sinai Desert. Instead, as part of the thinly spread WFF, the Regiment’s task was to prevent the Grand Senussi’s irregular army from invading Egypt via the diagonal line of oases that runs east-south-east from the Libyan border through the Siwa Oasis to El Baharia and the huge Baharia Oasis. At some point Charlesworth’s Regiment moved to Shousha, where it received training in infantry drill and tactics until 8 December. From there to Baharia, where the training continued into January 1917 until, on 14 January, the aged steam-powered coaster SS Missir (1864, torpedoed on 29 May 1918 by UB-51 c.85 miles north-west of Alexandria) ferried it from Es Sollum, on Egypt’s northern coast c.20 miles east of the border with Libya, to Alexandria.

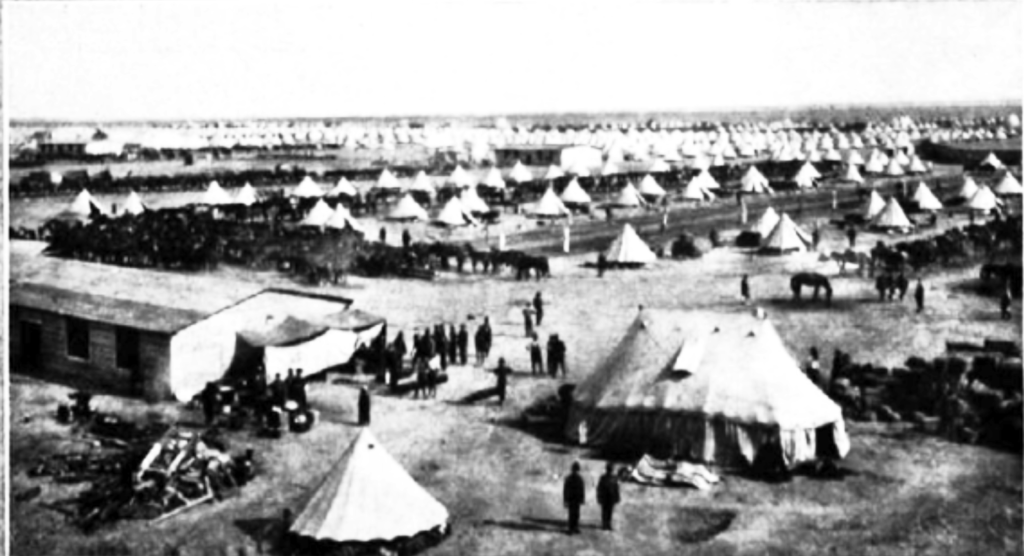

The New Zealanders’ Camp at Zeitoun (1916/17).

The Regiment then spent about six weeks at Zeitoun, the large training base just outside Cairo, where it continued to improve its musketry and learn infantry drill and tactics so that, on 4 March 1917, at nearby El Helmia, the 4th Dismounted Brigade could be transformed into the 231st Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Charles Edensor Heathcote (1875–1947) in the 74th (Yeomanry) Division, commanded by Major-General Eric Stanley Girdwood (1876–1963) until November 1918, with Charlesworth’s Regiment redesignated as the 25th (Montgomeryshire and Welsh Horse Yeomanry) Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. On the same day, coincidentally the date of Charlesworth’s promotion to probationary Lieutenant, the new Division began to assemble at El Arish, a sizeable town on the northern coast of the Sinai Desert some 90 miles east of the city of Kantara, that had been captured from the Turks on 21–23 December 1916. Then later on in the month, the Regiment moved into the Sinai Desert, where Allied troops were preparing to advance northwards and cross the southern border of the Ottoman Empire into Palestine. But as two-thirds of the 74th Division, including Charlesworth’s Brigade, were still in El Arish, it did not take part in the First Battle of Gaza (26–28 March 1917) – which the well-dug-in Turkish defenders of Gaza City and the coastal road northwards to Jerusalem won decisively at a cost of nearly 4,000 Allied casualties (see R.N.M. Bailey). On 4 April 1917, Charlesworth wrote a much briefer letter to Murray in which he expressed his sadness at the painful and sorrowful course of the war in Europe, his regret at not having seen “a decent bit of green grass for over a year now”, and his frustration with “even this mild form of belligerency” in the Middle East which, he commented, “ is becoming more than a joke”. But he also described the joy he had experienced at being taken on his first flight by their Magdalen friend J.R. Philpott, now a Captain in the Royal Flying Corps and waiting somewhere in England between being released from hospital and joining 63 Squadron.

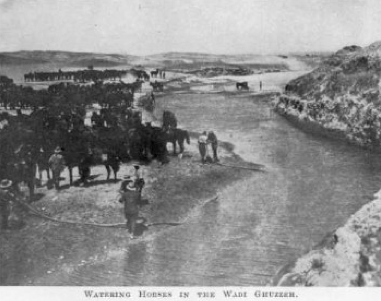

Watering Horses in the Wadi Ghazze (1916/17).

By 7 April the rest of the 74th Division had reached the Gaza area and was occupying a line along Wadi Ghazze, a deep river valley “of varying width – from 30 to 200 yards across, and with precipitous banks from 10 to 20 feet high” – that runs through the Sinai Desert from south-east to north-west and is dry in April but issues into the sea about five miles south of Gaza during the rainy season. During the Second Battle of Gaza (17–19 April 1917), the 74th Division was in reserve and so, once again, did not take part in the fighting even though it was ordered to stand to on the afternoon of 19 April and could hear the sounds of battle from Wadi Ghazze. Between the two battles, the Turks had strengthened the defences around Gaza, brought up reinforcements and established a line of strong redoubts along the road that links Gaza with Beersheba, about 18 miles to the south-east, and although the Second Battle’s outcome is often regarded as indecisive, it cost the Allies nearly 6,500 casualties killed, wounded and missing, and the Turks only about half that number. As a result of this inconclusive outcome, the General Officer Commanding (GOC) the Eastern Frontier Force (EFF), the Canadian Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Macpherson Dobell (1869–1954), was replaced on 19 April by Lieutenant-General Philip Chetwode (1869–1950), and the GOC EEF, General Sir Archibald Murray, was recalled to Britain (despite his invaluable logistical work in the desert), and replaced on 28/29 June 1917 by the more dynamic and more accessible Lieutenant-General (later Field-Marshal) Sir Edmund Allenby (later the 1st Viscount Megiddo) (1861–1936). Allenby immediately divided the troops under his command into XXI Corps, the Desert Mounted Corps, and XX Corps (comprising the 10th (Irish) Division, the 53rd (Welsh) Division, the 60th (2/2nd London) Division, and Charlesworth’s 74th Division), commanded until November 1918 by Lieutenant-General Philip Chetwode.

Defenders of Gaza in the first attack, 1917

The six-and-a-half months that followed the Second Battle were a period of stalemate, and during the first half of May 1917, Charlesworth’s Battalion moved a few miles eastwards, to a position near Wadi-en-Nukhabir, a tributary of the Wadi Ghazze that flows into it from the north-east during the rainy season. They also held a line from Dumb-Bell Hill to Tel el Jemmi, along the Mansura Ridge, which straddles the road going due south from Gaza and was now the Allied front line, having been wrested from the Turks during the recent battle after fierce fighting. On 16 May, the War Diary records that an “officers patrol encountered enemy”, and by 19 May the Battalion was in the front line trenches at an unspecified location, probably on the left of the Allied front line in trenches that connected Lees Hill with the hill of Ali Muntar and the road to Beersheba to their front. Here they spent most of the time training, patrolling no-man’s-land, and watching out for the “wily Turk” who was not very active on this front. But they also had to cope with the hot dry wind known as the Khamsin or Sirocco, that blows from the “parched, sun-scorched desert, either east, south-east, or south”, brings with it “a mist of fine sand, clouding the sun and shortening the horizon”, and strikes men “with a paralysing languor, a raging thirst, and fever”. Moreover, as the trenches were not in good condition, the Battalion spent three periods during the next two-and-a-half months (3–5 June, 20–24 June and 1–8 July) repairing and improving them. During this period, on an unspecified date, two officers and 50 ORs from Charlesworth’s Regiment raided the Cactus Garden to the south of Ali Muntar where they found some 80 Turks, whom they dispersed with grenades, killing seven and capturing two, while sustaining only two casualties themselves.

On 1 July 1917 Charlesworth was confirmed in the rank of Lieutenant, and on 9 July his Battalion left the Mansura Ridge and moved about three miles westwards in order to do three weeks of “vigorous training” in the coastal dunes and improve their musketry, which was rated “indifferent”. On 6 July, more artillery arrived from England in the shape of the 44th Brigade and these were organized into two batteries, each with six 18-pounder field guns – more were on the way. By 1 August Charlesworth’s Battalion, together with the rest of 74th Division, which now numbered 575 officers and 16,006 ORs, were encamped as a reserve back in the field, near Gaza, doing Brigade training, and this they continued throughout September. By early October the Battalion had returned to the coastal dunes a few miles south-west of Gaza, at Samson’s Ridge, a former strongly-held Turkish position that had been captured at bayonet point by the 160th (Welsh) Brigade on 19 April, and on 7 October the Battalion moved about five miles south-south-eastwards, to the desert village of Sheikh Nuran, where its training intensified until, on 25 October, XX Corps began a five-day march eastwards, to Khasif, a few miles west of Beersheba, where Charlesworth’s entire Division moved into covered positions in preparation for the coming assault on that town.

Beersheba (1917), with Turkish tents on the outskirts of the town (top right).

The plan of attack was extremely well thought-out and had been carefully rehearsed: once the problem of water supply had been solved by opening up old wells at Khasala and Asluj and extending the desert railway from El Shellal to Kharm (see Bailey), XX Corps was to deliver the main attack by driving into Beersheba’s western flank, while the Desert Mounted Corps was to make a wide enveloping sweep around the enemy’s outer flank to the south and east. During the night of 30/31 October Charlesworth’s Battalion moved into line at Kent Wadi, just to the south-west of Beersheba, where it dug in – as far as that was possible – in the hard stony ground. Charlesworth was personally detailed to take out a patrol of four men and returned at 04.30 hours on 31 October, having been stopped by snipers in Y Wadi. Then, just before 07.00 hours on the same day, after a 65-minute long artillery bombardment of the Turkish trenches and their wire entanglements, 60th and 74th Divisions, i.e. half of XX Corps, began their advance on the “very strongly held” defences surrounding the town, and took heavy casualties as they did so once the artillery support had ceased. On the right of the attack, the 181st Brigade, part of 60th Division, took Point 1069, a defensive position in front of the main Turkish front line, by 08.30 hours. But on the left of the attack, where cover was limited, the heat was worsening, and the landscape was difficult to negotiate; the four leading Brigades of the 74th Division were soon slowed down by enfilading rifle and machine-gun fire from Y Wadi, so that, by 10.40 hours, they were forced to dig in even though they were within 600 and 1,000 yards of the main Turkish positions.

At 12.15 hours, however, the British artillery began to fire again, and covered by a creeping barrage and its attendant pall of dust, the infantry continued their advance, cut the Turkish wire, and reached their objectives by 13.00 hours, by which time the enemy were in full flight towards Beersheba itself. During this attack, when Charlesworth’s 25th Battalion was at the forefront of the 231st Brigade, Acting Corporal (later Sergeant) John Collins, DCM (1880–1951), won the Victoria Cross for gallantry under fire, the first to be awarded in the Palestine Campaign. Charlesworth had been chosen to be the “directing officer” of the attack, and his Commanding Officer (CO) later wrote that “under very trying circumstances”, he “never went a yard out of his way, and our admirable direction was entirely due to his leading”. As General Chetwode did not want the two infantry Divisions to become involved in the fighting in Beersheba itself, he halted their advance and the town was captured during the afternoon of 31 October 1917 by cavalry units, notably the 4th (Australian) Light Horse Brigade, causing the defenders, the Ottoman III Corps, who had fought on Gallipoli, to withdraw north-north-westwards to the defences around Sheria and north-eastwards towards the hills of southern Judea near Tel el Khuweilfe, leaving nearly 2,000 of their comrades as prisoners. During the action, Charlesworth’s Battalion took c.140 prisoners but lost c.220 of its number killed, wounded or missing: “Very hot and trying lying out in the sun”, the Battalion War Diary later commented.

Between 1 and 7 November, the Allied advance northwards had three main focuses, all of which can be seen in retrospect as aspects of the Third Battle of Gaza. The first is also known as the Battle of Tel el Khuweilfe (1–6 November 1917), a small town c.13 miles north of Beersheba at the southern end of the Judean Plateau, described as “an arid, waterless, and mountainous tract of country”, where there was, nevertheless, an all-important water source. The second, and most important of the three Schwerpunkte, involved the well-prepared Turkish defensive line that curved downwards and westwards from Tel el Khuweilfe, then westwards through Tel esh Sheria, where there were important wells and the north–south railway line crossed the Wadi el Sheria, then on through nearby Abu Hureira on the maritime plane, and finally north-westwards to Gaza on the coast. And the third Schwerpunkt involved a carefully phased attack on the town of Gaza itself, designed to persuade the Turkish generals that it was the offensive’s main objective.

Tel el Sharia, where a railway station on the north-south Turkish railway line to Beersheba was located.

And so, after two-and-a-half weeks of heavy shelling by Allied artillery and naval forces off-shore and a week of fierce and prolonged fighting, the remains of the Turkish garrison finally withdrew in good order northwards from the ruins of Gaza by midnight on 6/7 November, destroying roads, bridges, culverts and water-lifting plant as they did so.

Gaza after its surrender to Allied forces (late 1917).

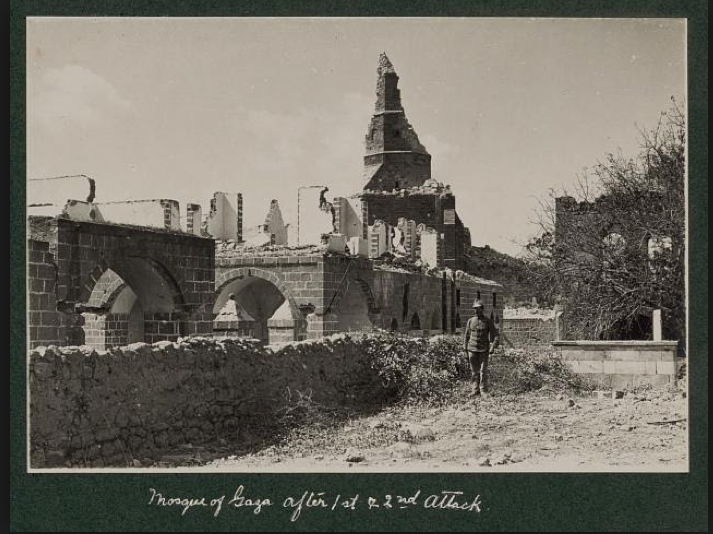

The Gaza Mosque after the Second Battle of Gaza (1917)

Charlesworth’s Division was engaged in the second aspect of the Battle. At 01.00 hours on the night of 1 November, the 231st Brigade moved eastwards to Wadi es Saba, just on the edge of Beersheba, where it helped to clear the area of salvage and bury the Turkish dead. On 3 November it was decided that XX Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps should move northwards some five or six miles and prepare to attack the Turkish line on the following day. But water shortage problems caused the attack to be pushed back by two days until proper supplies had arrived. So, on 5 November, “with all ranks on half a gallon of water” and washing and shaving forbidden, Charlesworth’s Battalion, together with the rest of the 74th Division, marched north-westwards until it reached the defensive line joining the village of Abu Hureira (about five miles north of Beersheba and straddling the road linking that town with Gaza) with Tel esh Sheria to the east, where it took up a position on the eastern end of the Allied line, with the 60th Division on its left. At 04.00 hours on 6 November, the 74th Division opened the attack by XX Corps, outflanked the Turkish line to the east over very open country, rapidly took some of the redoubts and short sections of trench, and at 13.30 hours reached its objective, the north–south railway line to Beersheba. It was followed by the 10th and 60th Divisions who were trying to press on to Tel esh Sheria along the Wadi Sheria. After a day of intense fighting, which ended in the destruction by the Turks of a large ammunition dump near Sheria station, the Turks retired westwards towards the main road at Abu Hureira, where they had established a large redoubt that was successfully stormed by the 10th Division on the following day. Elsewhere the fighting went on until dusk on 6 November, when the 60th and 74th Divisions were ordered to turn 90 degrees in order to face possible Turkish counter-attacks from the north-east. Tel esh Sheria was taken at about 04.30 hours on 7 November, and by the end of that day, after more fierce fighting, the entire Turkish line between Tel esh Sheria and Abu Hureira had been captured. Although, on the following day, the 74th Division was in reserve, the 60th Division was able to penetrate as far north as the town of Huj, seven miles east-north-east of Gaza and a desert railway terminus, in support of the Australian Mounted Division. Surprisingly, the War Diary of the 25th Battalion has little to say about the fighting on 6 and 7 November and its attendant casualties, but it does record that the Battalion spent a lot of 7 and 8 November collecting military salvage and burying the Turkish dead.

Because of water shortage and the lack of adequate transport, it was decided not to involve XX Corps in the next phase of the fighting – with the exception of the 60th Division, which was ordered to leave Huj and join up with the rapidly advancing XXI Corps. This phase began on 7 November, when Allenby ordered his troops to continue their advance northwards from the Wadi Sheria, and it culminated in the taking of the Mughar Ridge (13 November) and the crossroads town of Latron (16 November), c.15 miles west of Jerusalem and eight miles south of Ramleh, where the Jaffa–Jerusalem road enters the Judean Hills. The defeat of 16 November caused the Ottoman III Corps to withdraw further northwards into the Judean Hills, destroying more of the infrastructure as they went and setting up defensive strong-points in a rough terrain that favoured defence. As a result, General Allenby immediately decided to pursue the Turks in order to prevent them from regrouping and organizing a well-planned counter-attack.

Meanwhile, together with the other elements of the 74th Division, Charlesworth’s 25th Battalion spent from 9 to 17 November in or near the village of Kharm, the terminus of the east–west branch line from the coastal town of Rafah into the desert, and it then spent a week in or near the recently completed railhead at El Shellal, some seven miles west of Kharm. But from 23 to 29 November, i.e. after the start of the rainy season on 19 November, the 74th Division, now equipped with steel helmets, marched northwards to help relieve the exhausted XXI Corps and participate in the encirclement of Jerusalem from two sides.

Junction Station, Palestine (late 1917 or early 1918).

(Donor British Official Photograph Q12711)

The 25th Battalion advanced via El Mejdal (25 November), Nahr Sukereir (26 November), the key railway interchange c.20 miles to the west of Jerusalem that was known as Junction Station (27 November), and then Latron (28 November), and although the distance between the two previous places was just seven miles, it took the Battalion four-and-a-half hours to cover it, as the road climbed uphill all the way. Somewhat laconically, the Battalion War Diary commented that “most of this march was over very rough mountain paths where single file formation was necessary”, but the official history of the 74th Division put it more dramatically, describing the country as one of “terraced hills, of narrow valleys between steep precipitous sided hills, and of ridges like hills”. The 231st Brigade arrived in Latron at 12.30 hours and at 19.00 hours was ordered to march along the high road to Enab and thence to Beit Annan, where it arrived at 04.30 hours on 29 November, after marching along a “rough track with loose boulders, and winding in and out of the hills”. Here it was ordered to relieve the 8th Mounted Brigade in the front line by occupying a stretch between Wadi Zait (south-east of Beit Dukka) and Hill 1750, a high point that commanded the surrounding countryside and was occupied by the Turks. According to the Battalion’s War Diary, the march to the front line was made “under great difficulty, [the] track being so precipitous”, or, as the official history of the 74th Division put it, through “a jumble of steep rocky hills, falling precipitously into deep wadis, and rising over 2,000 feet in some places” and via “native tracks running up and down the sides of mountains”.

Moreover, as the available intelligence was patchy and the standard maps were old and inaccurate, on 30 November 1917 Charlesworth’s Battalion, along with the rest of the 229th and 231st Brigades, found itself involved almost immediately in unplanned and confused fighting around Hill 1750 and the village of Beit-Ur-el-Foka, nine miles north-west of Jerusalem and one mile north-west of the village of El Tireh. Elements of the 74th Division took the initiative and enjoyed success at first, and the War Diary of the 25th Battalion records that the Turks occupying Beit-Ur-el-Foka were taken by surprise and that over 600 prisoners were captured. But this proved to be an overstatement, and when the Turks counter-attacked, they fought with extreme tenacity, retook both the village and the hill, and went on to take El Tireh, forcing the 229th and 231st Brigades to withdraw. The confused fighting around Beit-Ur-el-Foka and Hill 1750 continued until elements of the 10th Division arrived on 4/5 December, i.e. four days after the 25th Battalion had withdrawn to a Wadi west of Beit Annan in order to spend the first four days of December resting and building roads, and it had cost the Battalion five officers and 74 ORs killed, wounded and missing. Its War Diary concluded: “The Battalion had had 6 days hard marching, the last 2 nights of which were spent in marching the whole night in addition to the day marching, in most difficult and tortuous country.”

On the night of 5/6 December 1917, the 231st Brigade, including Charlesworth’s Battalion, returned to the front in the mountainous country north-west of Jerusalem and relieved the 60th Division in the Beit Izza-Neby Samwil defences, on top of a commanding hill. On 8 December it took part in XX Corps’s successful offensive against enemy positions in extremely cold, wet weather, to the west and north of Jerusalem, during which the 231st Brigade was tasked with holding the line against counter-attacks. But in the early hours of 9 December, it was discovered that the Turks had withdrawn from Jerusalem (and the city was duly surrendered to the British), and at 09.30 hours Charlesworth was sent out with a patrol to see whether El Jeeb, about seven miles north-west of Jerusalem, was still occupied by the enemy – but the patrol was prevented from reaching the village by hostile fire and reported that at least 50 Turks were still defending it. Later that day, the Battalion marched back to the front line at Wadi El Marna, which was difficult because heavy rain had all but destroyed the road, and “steel helmets & the first rum ration [were] issued to the troops”. But no Allied units entered Jerusalem until after General Allenby had made a formal entrance on foot early on 11 December 1917.

The 25th Battalion stayed in the Judean Hills for another ten days, with its left flank on the mountain village or Beit-Ur-et-Tahta, c.13 miles north-west of Jerusalem, making roads and undergoing specialist training, before marching off at 13.00 hours on 20 December, presumably to take part in the 74th Division’s assault on the Turkish positions to the north of Jerusalem. The assault, which included the occupation of Jerusalem, had been scheduled to begin on 24 December but was postponed until 27 December because of the deterioration of the already vile weather on Christmas Day, and it was not until 28 December that the 74th Division took Beituniye, just to the west-south-west of Ramallah, and Ramallah itself on 29 December.

From 30 December 1917 to 16 February 1918, Charlesworth’s 25th Battalion was largely in Corps reserve, and employed in constructing the road that was being built towards Ain Arik, in the Judean Hills roughly five miles west of Ramallah. The back-breaking, monotonous work was frequently interrupted by appalling weather, which varied between “heavy rain” and “bitterly cold rain” and was so bad that during the night of 6 January 1918 six of the Battalion’s newly arrived small white donkeys died of exposure. On 8 January 1918, while his Battalion was engaged in this dispiriting work, Charlesworth wrote his last extant letter to Murray. It is a long letter, written in pencil on a military notepad during the “horrid” rainy season that afflicts the “unholy land” from December to February and makes military operations impossible. Charlesworth, who wrote it while “huddled up under a leaky bivvy sheet”, described the meteorological situation as follows:

the heavens [shower] milk & honey in awful profusion until the gorge-like valleys are one roaring torrent of molten butterscotch & embryo toffee, and the little hills skip so high all around – presumably to keep their feet dry. We are at present on such a lofty hill top that we are usually swathed in the low clouds which rest lovingly on every hill above 2000 feet.

But despite the depressing weather and in contrast to his first three extant letters to Murray, Charlesworth’s earlier feelings of acute ambivalence towards the war have become far less complicated and, after two-and-a-half years of military service away from the pacifists whom he had known at Oxford, more those of a proper British officer. His sense of the similarities between the warring nations has given way to a straightforward dislike of Teutonic aggressiveness in any shape or form, even architectural; and his earlier attraction to pacifism, though still audible beneath the ironies, has been largely occluded by a resigned, quasi-professional willingness to take what comes without dwelling on it, combined with the determination to survive. Thus, in what is the most philosophical paragraph of his letter, he told Murray:

As a matter of fact the nearer and fuller acquaintanceship with real war, has not affected me nearly as much as I had expected. No unpleasant sight or happening has yet begun to haunt my dreams as I had feared & one is constantly so surprised and delighted at finding oneself still alive, that there is little time for one as selfish as myself to feel the loss of friends less fortunate – and at the worst moments life seems but a wild impossible dream wherein some other self is acting. – I suppose death is like that.

But after getting these darker feelings off his chest, the rest of his letter deals with lighter subjects: his mixed feelings over Philpott’s capture by “Johnny Turk”; what he has enjoyed reading – an adventure story by P.C. Wren called The Wages of Virtue; a sight-seeing visit to Jerusalem; and the virtues of the “bronzed and virile looking” British Tommy in contrast to the “pastey [sic] faced weaklings” and “decadent and despicable lot” who were said to inhabit that city.

On 16/17 February 1918, the 231st Brigade was attached to the 60th Division for forthcoming operations to the north of Jerusalem, during which it was to support the advance of the 181st Brigade near Mukhmas, about five miles north of Jerusalem on the main road to Nablus. From 18 to 21 February the advance continued without opposition, and from 24 February to 7 March, when the Battalion moved to Wadi Medway, it was back at construction work on the Nablus road. So the 74th Division took only a very minor part in the dramatic capture of Jericho, c.15 miles north-east of Jerusalem (19–21 February 1918), and on 3 March 1918 it received orders to prepare to leave Palestine for France, where the situation was starting to become critical as the Germans pressed forward towards Paris on three fronts during the build-up to their massive spring offensive that would be known as Operation Michael.

Five days later, however, the 74th Division, including Charlesworth’s Battalion, prepared to take part in the general advance northwards that became known as the Battle of Tel ‘Asur (and the Battle of Turmus ‘Aya). The point of the action, which took place along a 14–26-mile front from the Mediterranean coast on the west to the Jordan Valley on the east, was to create a secure base for operations in Transjordan. XX Corps straddled the road to Nablus, with the 74th Division on its western side, between the 10th and the 53rd Divisions, and the 60th Division on its eastern side, next to XXI Corps, and the start line of both Divisions just above the village of El Bireh. At 01.30 hours on 9 March 1918, the 25th Battalion supported the 10th (Shropshire and Cheshire Yeomanry) Battalion, the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, in its successful attack on Selwed Hill, which it took at 05.00 hours, and three of its Companies pushed forward while ‘D’ Company, under Charlesworth, who had been promoted Acting Captain on 27 February 1918, waited until the advance was successful before following through in support. At 09.15 hours the 25th Battalion, together with the 10th Battalion of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, was ordered to continue the advance and attack the Burj el Lisaneh-Sheikh Saleh Ridge, but it and its right-hand neighbour were found to be strongly held, and this, plus the nature of the intervening country, which included the cavernous gorges of the Wadi el Jib and the Wadi el Nimr, at first “rendered a further advance impossible”. Nevertheless, at 19.30 hours the order was repeated, a way was found across the gorge of the Wadi el Nimr, and at 23.00 Charlesworth’s Battalion deployed for an uphill advance onto the precipitous ridge. According to the Battalion’s War Diary, “The enemy was entirely taken by surprise and after throwing a few bombs, hastily withdrew towards Mezrah esh Sherkiyeh”, and at 03.30 hours on 9 March the ridge was taken “without a single casualty”.

The rest of the day was spent consolidating the position and throwing back a Turkish counter-attack: two more unsuccessful counter-attacks followed on 10 March at 06.30 hours and dusk. The two other Divisions to the west of the Nablus road experienced similar resistance at first, but when, on 11 March, the 231st Brigade continued its advance across very difficult terrain, it encountered no opposition and by 06.15 hours Charlesworth’s Battalion had taken the village of Sheikh Selim. At 14.15 hours on the same day, the 25th Battalion continued its advance to Turmus ‘Aya and the high ground beyond, but in the end it was stopped by heavy resistance at Khirbet-Amurieh, a small conical hill that rises steeply from the surrounding plain, having suffered 70 casualties killed, wounded and missing. But overall, the battle was successful, especially on the plain between the Nablus road and the River Jordan, where casualties were light, and the subsequent five-mile advance provided the Allies with a new front line that remained static during the hot summer weather until Allenby’s final advance northwards and north-eastwards could begin in September 1918. So on 13/14 March the 231st Brigade was relieved by the 230th Brigade, and the 25th Battalion, now in reserve, carried on building roads in the direction of Nablus until 5 April, when, with the rest of the 74th Division, it began its journey back to the Western Front via Ramallah (7 April), Suffa (8 April), Latron (9 April) and Ludd (10 April). On the following day it entrained for the railhead of Kantara, just east of the Suez Canal and c.100 miles north-east of Cairo, and it trained here from 12 until 28 April.

On 29 April 1918 the Division travelled by train to Alexandria, where it embarked on the 11,000-ton passenger liner SS Malwa (1908; scrapped 1932) and disembarked at Marseilles on 7 May 1918. After resting for a day, Charlesworth’s Battalion entrained on 9 May and three days later it arrived at Noyelles-en-Chaussée, about six miles north-east of Abbeville. From here it marched three miles westwards to the village of Domvast, where it trained until 22 May 1918 in trench warfare, especially defence against gas, with which it was completely unfamiliar, and it was issued with new masks. On the following day it was taken by train to Magnicourt-sur-Canche, c.30 miles to the west, and rested for a day before marching another nine miles westwards to the village of Habarq, where it trained for a month in the tactics of cooperation with tanks and contact aeroplanes. On 26 June it rested in billets at St-Hilaire-Cottes, just to the south of Norrent-Fontes, before taking part in a series of tactical exercises until 9 July, when it moved to the trenches at Ham-en-Artois, just north of Lillers, and suffered its first casualties in France. On 17 July, a Sergeant Varley of Charlesworth’s Battalion entered the German trench, saw that the sentry had his back turned, and quietly captured a machine-gun, which he brought back safely. Then, beginning on 18 July 1918, the Allied counter-attack gradually drove the Germans back north-eastwards, and after the 25th Battalion had come out of the trenches on 23 July and spent five days in Brigade reserve, it moved on 28 July to the St-Floris Sector of the front, between St-Venant and Merville, where it was heavily shelled with gas shells. Charlesworth missed the start of the advance by the British IVth and the French Ist Armies on 8 August, having been granted home leave for the first time in early August 1918, during which, a couple of days before his return to France on 21 August, he became engaged to Maud Winter.

Meanwhile, the 25th Battalion stayed in the St-Floris area until 18 August, when the Germans withdrew further north-eastwards, and the Battalion was compelled to intensify its patrolling in order to establish the extent and quality of the German resistance – and once again the Germans countered with hundreds of gas shells. On 25 and 26 August 1918 the Battalion marched to billets in Robecq, just south of St-Floris, and then Mazinghem, some seven miles to the west, where it rested until 29 August and then, together with the rest of 74th Division, entrained for the battlefields of the Somme, well to the south. Here, as part of III Corps, the Battalion detrained at Méricourt-sur-Somme, eight miles south of Albert, and then withdrew another eight miles north-westwards to Ribemont, some seven miles north of Villers-Bretonneux. After taking part in the Battle of Bapaume (2–3 September 1918), Charlesworth’s Battalion moved south-east to Tincourt Wood, about four miles east of Péronne, where fighting began in earnest once again on 5 September.

The Allied advance north-eastwards then continued with some speed, and after Charlesworth’s Battalion had rested and recuperated out of line for a week or so with effect from 9 September, it returned to the front line in order to take part in the Battle of Epehy on 18 September 1918 when, starting at 05.20 hours, the British IIIrd and IVth Armies and the French Ist Army made a well-organized surprise attack on a 17-mile-long section of the Hindenburg Line under the cover of a heavy creeping barrage by field artillery, using three-minute lifts. The attack was launched at 05.30 hours in a cold downpour of rain, and although Charlesworth’s 231st Brigade took its first objective without much trouble, the second objective was tenaciously defended by a mass of machine-guns, and the two leading Battalions, one of which was the 25th, were brought to a halt and formed a defensive flank along the Bellecourt Road. But Charlesworth had already been mortally wounded at around 06.30 hours at Ronssoy (Orchard Post), some ten miles north-north-west of St-Quentin near the northern end of the front, and his CO described what happened as follows:

He was hit by machine-gun bullets as he was leading his company forward in the attack, and as the gun was doing serious damage to his men he gallantly went for it to try and silence it and save his men. Although in doing so he sacrificed himself, his act saved numerous lives. We have lost in him a splendid officer and a splendid companion. He had done magnificently with his company, and his men adored him – nothing was ever too much trouble for him to do for them, and he lost his life in trying to save them. I cannot tell you how those of us who had served for the last year and a half with Raymond feel his loss; all last winter in Palestine he did splendidly, and, however hard the times, was always bright and cheery.

Charlesworth died of his wounds, aged 24, at 02.00 hours on 19 September 1918 in No. 20 Casualty Clearing Station, at Doingt, just to the east of Péronne, one of the 25th Battalion’s 110 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing that day and one of the 74th Division’s 185 officers and 3,336 ORs killed, wounded or missing during September 1918. Buried: Doingt Communal Cemetery (Extension); Grave I.A.23; the inscription reads “Thy Kingdom come”.

Doingt Communal Cemy (Extension); Grave I.A.23.

Charlesworth’s Eton obituarist commented:

As one who knew him well wrote: [he was] shy and modest […] mostly silent while others talked […] yet I think many of us knew or suspected that behind that quiet and unassuming manner there lay a strength which would be capable of great things if put to the proof […] The Trial came and he showed the qualities which we had expected.

On 23 September 1918 Charlesworth’s father wrote a letter to President Warren in which he said: “He mourned the loss of nearly all his great friends at Magdalen & often used to say in his letters that it seemed unfair for him to be left.” Warren clearly replied with his customary perspicacity, sympathy and delicacy of feeling, for on 28 September 1918, Charlesworth’s father, who was an emotional and deeply religious man who was interested in missionary activities and had found great comfort in the CO’s account of his son’s death, responded with a second letter to Warren in which he said:

Though I write all day & much of the night, I cannot keep pace with the kindness of my friends. When I was thinking last night what I should say in reply to your letter, I thought that I should say that among the multitude of letters there were four that touched me most deeply. Today has brought the two which I add to them. Five of them are from those to whom our dear boy owes his training – the others from a very dear old friend to whom I owe some of mine – Of the six, two come from Magdalen. Yours & Cookson’s are those two I prize most highly of all. One expects from those who live in & love beautiful Magdalen, beauty of thought & expression – but what can I say to express to you my gratitude for the words you used – “He was indeed, amiable, good, chivalrous, gallant, gentle but as brave as brave – truly a young “Knight of God”. Believe me, this is no mere empty expression of thanks: you perhaps do not know how proud you have made me – how grateful I am. I have quoted your words & some of Cookson’s in many letters to our friends, so amazingly kind. Knowing now as perhaps we might not have known, had he lived, what those, with a right to speak, thought of his character, may we not, in the midst of our proud sorrow, almost rejoice that we have been privileged to give our best & dearest to such a cause? I thank God that some strange instinct led me, when my father said I might choose my college, to choose Magdalen – always dear to me – even more dear than Winchester and that I was allowed to make my son, as you have put it, a grandson of that beloved place. I rejoice that perhaps his name may some day find a place in the long and noble roll of which there will be a record in Chapel? Had he lived, his name would not have been – as I hope it now may be – permanently recorded among those of Magdalen’s gallant sons: surely another cause to make me glad. […] In one of his last letters he wrote “I feel that I must love everyone, I can’t get up a scrap of hatred even for the Hun”. Still he was a crusader in the Holy Land & I know from three brother officers how well he bore himself. Of course you shall have details when I know them and we are deciding which photograph to send you: I am so glad we had so many taken in the garden here when he was home in August – the best we think was in a group, from which we hope to have a separate picture made.

Charlesworth’s friend Murray also wrote an immediate letter of condolence to his family, to which Charlesworth’s father replied on 7 October 1918 with even more feeling than he had to Warren ten days earlier. The letter, understandably, expresses a very high view of Charlesworth’s personality and beliefs, and also shows what consolation could be had from a fairly standard letter of condolence from a sympathetic superior officer, comrade, or friendly Chaplain, and what psycho-spiritual support could be derived amidst an unprecedentedly violent and bloody war from conventional Christian religiosity. But ironically, whilst that latter form of comfort was more available to the bereaved a century ago than it is today, it must also have had the effect of prolonging the conflict that was causing the bereavement by generating the belief that the sufferings of the departed had some meaning within a powerful and established religious scheme of things. The important part of Mr Charlesworth’s lengthy and moving reply reads as follows:

He was indeed, as the President of Magdalen said[,] “truly a young Knight of God” – hating & loathing as he did the folly & wickednesses of war, [but] since he was called to serve, he served in the right spirit – allowing no bitterness or hatred to enter his heart, even for his enemies: indeed in one of his last letters he wrote “I feel that I must love everyone, I can’t get up a scrap of hatred even for the Hun”. Truly a young Knight of God. And he ended a life, which, as you know, he tried to live straight[,] cleanly and unselfishly by the most unselfish act of all – by the gift of his life in a successful attempt (as his C.O. said) to save his men whom he really loved & who (his C.O. said again) “adored him”. We are thankful that he left us such an example and pray that it may always remain vivid. You who knew him so well & others, all speak of the loveable nature of him: his simplicity[,] his modesty[,] & quiet unassuming manner – but one likes to have a written record & for that reason especially I shall treasure your letter among several which I value most highly. I agree so fully in what you say as to him having “got there” in religious questions: but that was all founded on the one and only thing that matters in the whole world – Love. And of course you know how I agree as to the continuity of our love and fellowship with him – but for our Faith, life would amid all the sorrows & partings & horrors of these days be unsupportable & “not worth going on with” – “if in this life only we have hope” – Ah how sorry I am for those who have no Faith to support them – no wonder they set their teeth & grow hard and live just for the present – but we who believe he is still there to love & be loved – that he is called to some other wonderful work that we do not as yet comprehend – we can indeed take comfort & courage in our attempt to “get near the heart of things” & live such lives as may bring us all together again.

Charlesworth died intestate but had expressed the wish that his estate – £288 3s. 10d. – should go to his fiancée.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

** R[ichard] G. Wilson, Greene King: A Business and Family History (London: Bodley Head and Jonathan Cape, 1983), passim (esp. pp. 60–129).

* –– ‘Greene family’ (per. 1801–1920), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 23 (2004), pp. 556–9.

*Dudley Ward (1922), pp. 20–234.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Captain Raymond Frederic Charlesworth’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,915 (8 October 1916), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘In Memoriam: Captain Raymond Frederic Charlesworth’, The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,668 (24 October 1918), p. 504.

The Sphere [photo], 2 November 1918.

[Anon.], ‘Baronet Found Shot in his Club’, The Times, no. 42,205 (15 September 1919), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Sir James Domville’s Death’, The Times, no. 42,206 (16 September 1919), p. 13.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sir James Domville’s Affairs’, The Times, no. 42,214 (25 September 1919), p. 5.

Ford (2009), pp. 299–391 (esp. pp. 338–341, 355–61, 364–7).

Mortlock (2011), pp. 89, 111, 138–49.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/290-297 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to F.R. Charlesworth [1912–1918]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/78.

ADM188/631/39024.

ADM196/144/52.

Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967), ‘In no strange land’, The Murray Papers, Liddle Collection, Leeds University: CO 066 (File 5). Contains: five letters from Charlesworth to Murray of 19 March 1915, 1 April 1915, 29 June 1915, 4 April 1917 and 8 January 1918; one Christmas card from Charlesworth to Murray of Christmas 1917; one letter from Charlesworth’s father to Murray of 7 October 1918.

WO95/4427.

WO95/4679.

WO374/13313.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Baku’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Baku (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Hareira and Sheria’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hareira_and_Sheria (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Jerusalem’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Jerusalem (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Mughar Ridge’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mughar_Ridge (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Tell ’Asur’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tell_%27Asur (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Tel el Khuweilfe’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tel_el_Khuweilfe (accessed 28 February 2019).

Wikipedia ‘Dunsterforce’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunsterforce (accessed 28 February 2019).