Fact file:

Matriculated: 1914

Born: 30 March 1896

Died: 15 September 1916

Regiment: Rifle Brigade

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Pier and Face 16B and 16C

Family background

b. 30 March 1896 as the older son (in a family of two boys) of Charles Hector Parsons (1865–1915) and Mary May Parsons (née King) (1869–1943) (m. 1893). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at Claremont, Sherbourne Road, Yardley (two servants); it later moved to Monkspath Priory, Shirley, Warwickshire, and at the time of Parsons’s death his widowed mother was living at 5 Vicarage Road, Edgbaston, near Birmingham.

Parents, antecedents and sibling

Parsons’s father was the son of Charles Joseph Parsons (1837–93) a Birmingham coffin manufacturer who was elected Borough Auditor and Assessor for the Deritend and Bordesley Ward of Birmingham in 1866. During the banking crisis of the mid 1860s the Birmingham Banking Company was the largest bank to fail; it was restructured and reopened in August 1866 and Charles Joseph Parsons together with many small manufacturers and businessmen was one of the partners. After a series of amalgamations and name changes the bank was taken over by the Midland Bank in 1914. Charles Hector followed in his father’s business but retired early, possibly due to bad health. But in 1910 he was elected a Warwickshire County Councillor.

Parsons’s mother was the daughter of James King (1835–1914), a cabinet maker who later became a partner in Chamberlain, King and Jones Ltd., house furnishers of Birmingham. When he died he was described as “one of the oldest and most respected tradesmen in Birmingham”. He left £64,000. The founder of the firm, Joseph Butler Chamberlain (1817–74), was not (in the male line) related to the better-known Joseph Chamberlain (1836–1914), the Liberal Unionist and one-time mayor of Birmingham.

Eric King’s younger brother was Charles Roy (“Peter”) (1897–1975), who in 1920 married Joan Louise Allday (1897–1978), the daughter of a Solihull pneumatic engineer; they had one son.

Charles Roy was awarded the MC in December 1917 while serving in France as a Lieutenant in the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. Later he served on the headquarters staff of the 184th Infantry Brigade. He became a successful breeder of race-horses and hunters in Henley-in-Arden, Warwickshire.

Education

Parsons attended Lindley Lodge Preparatory School, Higham-on-the-Hill, near Hinckley, Leicestershire (closed in the 1930s/1940s), from 1906 to 1909. He then attended Repton School from 1909 to 1914, where he played cricket in the First XI in 1913 and 1914. He was accepted at Magdalen as an Exhibitioner in Natural Sciences in 1913 and matriculated on 13 October 1914. He was exempted from Responsions because he had an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate, but after taking an Additional Responsions Paper on the French Historian and Politician Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877) in Michaelmas Term 1914, he left without a degree at the end of that term in order to join the Army.

Eric King Parsons

(Courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

War service

Parsons, who was 5 foot 8 inches tall, applied for a Temporary Commission on 28 November 1914 and on 10 December 1914 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 9th (Service) Battalion, the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own), that had been formed in Winchester on 21 August 1914. His history thus runs parallel to that of the slightly older Herbert Garton. By November 1914 the Battalion was in billets at Petworth, where it trained until February 1915. Parsons landed at Le Havre with his Battalion on 20 May 1915 as part of 42nd Brigade, 14th (Light) Division. The Battalion then travelled by train to Cassel (22 May) whence it marched to Bailleul (5 June) via Zeggers Capel (23 May), St Sylvestre (27–30 May) and Zevencoten (31 May–5 June). It spent six days in the trenches at Bailleul, taking casualties from heavy shellfire, and then, on 12 June, it marched northwards to the Ypres area where it stayed until 27 July, mainly in the trenches near Poperinghe, and just on the edge of the débâcle that took place at Hooge Crater of 29/30 July (see B. Pawle, H.N.L. Renton and O.G. Parry-Jones).

On 5 August 1915 Parsons was promoted Lieutenant and became his Battalion’s Transport Officer at around the same time. From 8 to 10 August, the Battalion took part in the fighting at Hooge, a limited action which largely consisted in a surprise attack by the British 6th Division and elements of the 14th (Light) Division, and the recapture of the huge crater that had been created at Hooge on 19 July 1915 and then recaptured by the Germans ten days later. During this fighting, Garton was wounded and invalided out of the Battalion for about nine months. The Battalion was still in the Wieltje/Vlamertinck area throughout September and took part in the attack on Bellewaerde Ridge and Farm on the 25th of that month which cost the British 4,000 casualties. The attack, which began at 04.30 hours and involved an advance upon a glacis that was swept by machine-gun fire, got into the German trenches but failed to hold them. The War Diary attributed this to the fact that the Battalion suffered very heavy casualties (including six officers killed and four wounded) very early on in the fighting, to the numerical superiority of the Germans who seemed to have “an endless supply of bombs”, to the failure of the 6th Division’s attack on the right, and to the “extreme difficulty” involved in “getting messages through quickly and finding out what was happening in other parts of the line”.

The 9th Battalion stayed in the vicinity of Elverdinghe until 14 February 1916, when it moved south to the Arras Sector of the front. It was still there in late May when Garton rejoined it and, like the 7th and 8th Battalions of the Rifle Brigade (in the 41st Brigade of the 14th Division), it was experiencing a rise in casualties from around 5 to 50–60 per calendar month. When the Battle of the Somme began on 1 July 1916, Parsons’s Battalion was still in the Lens/Arras area. It did not leave there until 1 August, when it began a week of rest in Candas before moving to the village of Fricourt, north-east of Albert, which had been captured on 2 July. During this period, Parsons was sent on a course at HQ to learn the duties of an Adjutant, and on the basis of this qualification he was promoted Captain on 2 July.

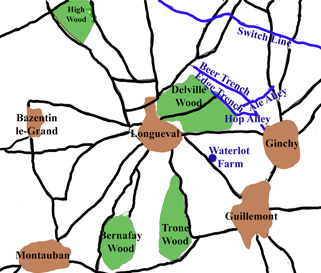

The Battalion arrived in Fricourt on 12 August and seven days later marched north-west to Longueval and the adjacent Delville Wood, where, for two days, it took over two new trenches from the 10th Battalion, the Durham Light Infantry, which was also part of the 14th (Light) Division (42nd Brigade). Parsons’s Battalion then stayed in the Fricourt/Delville Wood area until 31 August 1916, losing 43 other ranks as casualties. The Battalion spent the period 1 to 13 September at Le Fay, well away from the battle area, where it trained for the next major phase in the fighting that would become known as the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (15–22 September), famous because it was here that tanks were used for first time. During the night of 14/15 September the Battalion, which had spent the previous day at Dernancourt, gradually moved up into the front line, arriving on the rear slopes of Caterpillar Valley facing north-westwards towards the almost obliterated Delville Wood. 14th (Light) Division was positioned along the Longueval–Ginchy Road (South St) and out into the fields to the north of Delville Wood between the Guards Division (right/east) and the 41st Division (left/west), with Parsons’s 14th Division in its centre.

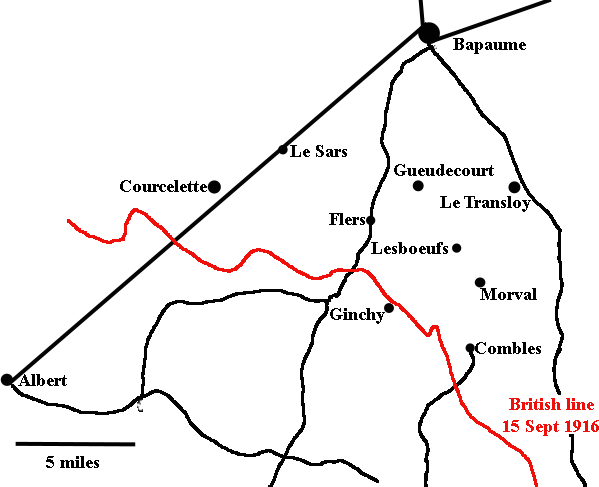

Map of the Flers-Courcelette Region

Map of the start of the attack by 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade on 15 September

On 15 September 1916, the first two Brigades of the 14th Division (43rd and 41st) began their attacks at 06.20 and 06.30 hours respectively in a north-easterly direction towards Gueudecourt, beyond Flers, nearly three miles away, with Garton’s 42nd Brigade forming a third wave with a slightly later zero hour. So advancing on a two-company front, with ‘A’ Company on the right supported by Parsons’s ‘C’ Company and ‘B’ on the left supported by ‘D’ Company, the Rifle Brigade’s 9th Battalion set out from the trenches near Trônes Wood, just to the south of Delville Wood and the west of Guillemont, reached the north-east corner of Delville Wood by 06.45 hours, and crossed Hop Alley and Ale Alley.

After that initial rush, it becomes difficult to reconstruct what happened. It seems that when the 9th Battalion were about 400 yards from the First Objective (the Green Line), its four companies changed into open order, whereupon they were caught by heavy machine-gun fire from the front and the German position on the right known as Pint Trench. But as the advancing companies could not have rushed the machine-guns without going through their own barrage, they settled down in shell-holes to wait for the barrage to pass over them. Once this had happened, the Battalion began to move forward once again and relieved elements of the 41st Brigade at the Second Objective (the Brown Line or Gap Trench), just south of Flers. And although it was able to pass through Flers, which had been cleared of Germans by tanks and infantry between 08.20 and 10.00 hours, its right flank was still unprotected so that its advance was stopped by the machine-gun fire just short of the Third Objective, Bulls Road, which ran just to the north of Flers. During the advance, ‘D’ Company ceased to exist, ‘B’ Company was driven back, but ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies held on near Flers until 16.00 hours, when the Battalion was withdrawn to Montauban in reserve. It now consisted of only four officers and 140 other ranks, having lost 16 officers killed and wounded – including its Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Herbert Picton Morris (1883–1916), his second-in-command and all four Company Commanders – and 298 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. 42nd Brigade did, however, take all its objectives and eventually stopped its advance just short of the village of Gueudecourt, one-and-a-half miles north of Flers.

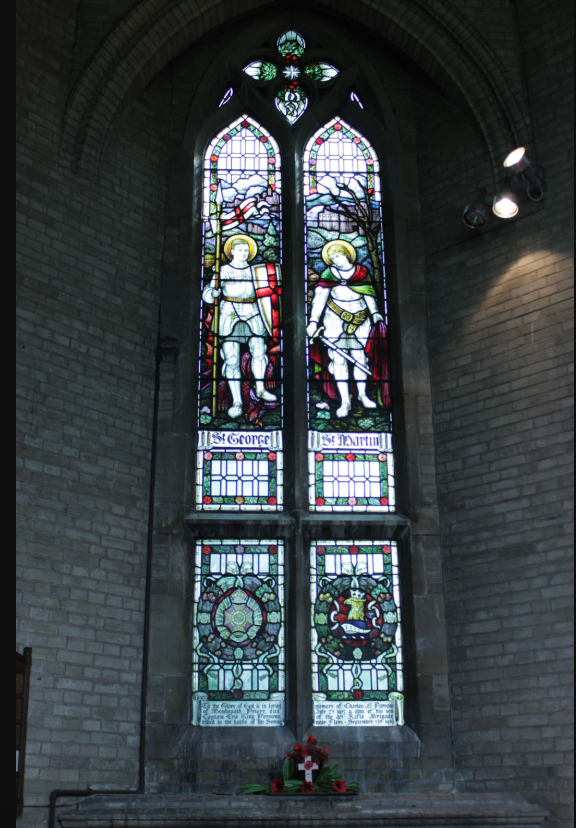

Four tanks were deployed at Flers on 15 September, and although only one came through that fighting intact, they had enabled Flers village to be captured very rapidly during the early stages of the Battle even if they had no direct effect on that part of the Battle in which the 9th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade was involved. Parsons was killed in action in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, aged 21. He has no known gave, but is commemorated on Pier and Face 16B and 16C, Thiepval Memorial, and together with his father by a memorial window in St Patrick’s Church, Salter Street, Birmingham.

He died intestate but his estate was valued at £276 2s 2d.

Memorial window St Patrick’s Church, Salter Street, Birmingham

(Photos courtesy of the Solihull Heritage & Local Studies Service at The Core Library, Solihull)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Captain Eric King Parsons’ [brief obituary], The Times, no. 41,281 (15 September 1916), p. 6.

Berkeley and Seymour , i (1927), pp. 138–40, 152–76, 196–208.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 101–4.

Pidgeon (2002), pp. 35–45.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: PR/2/18 (President’s Notebooks [1913]), p. 328

MCA: PR 32/C/3/943 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence. Letter relating to E.K. Parsons [1916])

OUA: UR 2/1/88.

WO95/1901.