Fact file:

Matriculated: 1911

Born: 6 March 1886

Died: 26 September 1916

Regiment: Coldstream Guards

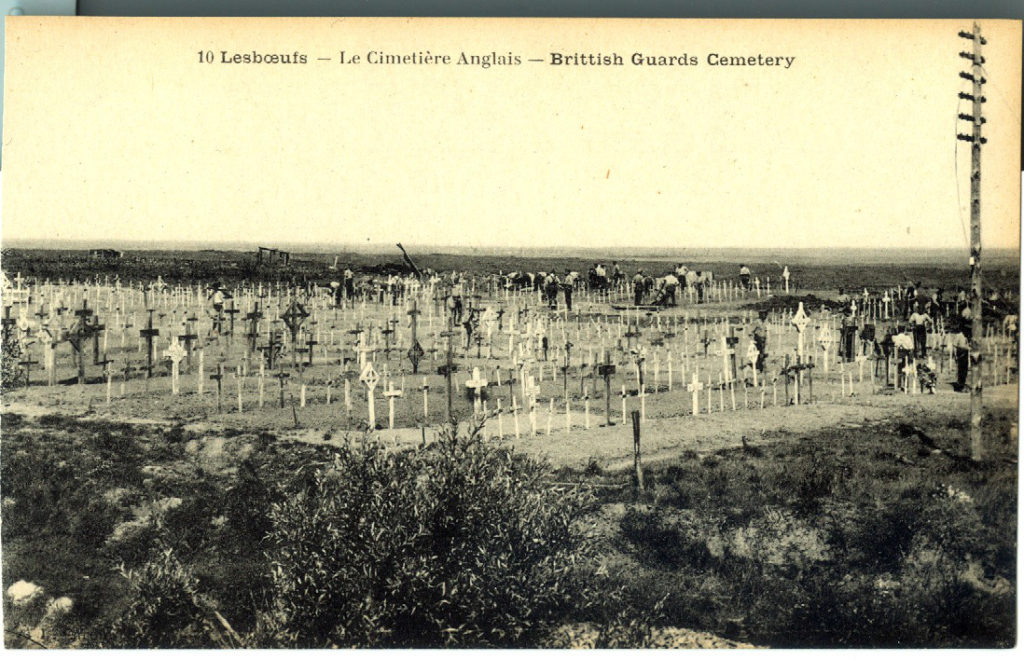

Grave/Memorial: Guards’ Cemetery, Lesboeufs: Special Memorial

Family background

b. 6 March 1886 at Hans Place, Chelsea, London SW, as the eldest surviving son (of six children) of Sir William Francis Clerke (1856–1930), 11th Baronet, of Hitcham, and Lady Beatrice Clerke (née Menzies) (1859–1954) (m. 1884). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family was living at 46, Lennox Gardens, Chelsea, London SW (seven servants); in 1901 and 1911 it was at the same address (with nine and eight servants) and also at Mertyn Hall, Flint.

Parents and antecedents

Clerke’s paternal grandfather, Sir William Henry Clerke Bt (1822–1882), was a principal clerk in the Treasury and Deputy Lieutenant for the county of Flint. Sir William’s mother, Mary Elizabeth Kenrick (1797–1873), was the only daughter of George Watkin Kenrick of Mertyn, Flint, and through whom the Mertyn estate came into the Clerke family. Clerke’s paternal grandmother, Georgina Gosling (1828–1909), was the daughter of the banker Robert Gosling (1795–1869), a partner in Gosling’s Bank, which traded under the sign of the Three Squirrels in Fleet Street. In 1896 several banks in London and the provinces, including Gosling’s, united to form Barclays Bank, a joint-stock bank.

Clerke’s maternal grandfather, Graham Menzies (1821–1880), was a prosperous distiller. In 1879 he bought the Hallyburton Estate for £235,000 (c.£11m in 2005) from the Marquis of Huntly. When it was built by Graham Menzies and Co., the Caledonian Distillery, Haymarket, Edinburgh, was the largest of its time. In 1877 six distilleries amalgamated in order to allocate production in fixed proportions and to set prices for grain spirits, but although amalgamated, each distillery was still run by its own directors. This amalgamation, known as The Distillers Company (DCL) was joined in 1884 by Menzies and Co. The DCL was first taken over by Guinness and later by Diageo. On his death Graham Menzies left £432,628 10s. (c.£20m in 2005).

Clerke’s father matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1874, took his BA in 1878 and was called to the Bar in 1881, at Inner Temple. He never practised. However, he took a particular interest in the Royal Hospital for Incurables in Putney, and was its chairman from 1923 until his death in 1930.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Ronald Graham Longworth (1888–89);

(2) John de Vere (1889–96);

(3) Beatrice Janet Elsie (1891–1980); later Henderson after her marriage in 1916 to Robert Evelyn Henderson (1881–1925): one son, two daughters;

(4) David Herbert Hamund (1897–1965);

(5) Charles Nigel (1899–1918).

Robert Evelyn Henderson was the son and nephew of Directors of the Bank of England, the Managing Director of the Borneo Company and other companies connected with the Far East, a Director of the London Association, and a farmer. He served with the 3rd Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, from March 1900 to 1903, when he resigned with the rank of captain. Part of this service was in South Africa during the Boer War. On 18 August 1914 he applied for appointment to a commission in the Special Reserve of Officers and was appointed Lieutenant in the 1st Lovat’s Scouts (London Gazette, no. 28,973, 13 November 1914, p. 9,275); on two occasions he served as an aide-de-camp on the General Staff. At some time he was transferred to the Guards Machine Gun Regiment and in January 1919 he relinquished his commission in that regiment due to ill heath (LG, no. 31,133, 17 January 1919, p. 1,032).

David Herbert Hamund served in France with the 15th Hussars: 2nd Lieutenant (LG, no. 29,671, 18 July 1916, p. 7,102), Lieutenant (LG, no. 30,531, 15 February 1918, p. 2,182). He remained in the Army until November 1922.

Charles Nigel was an invalid.

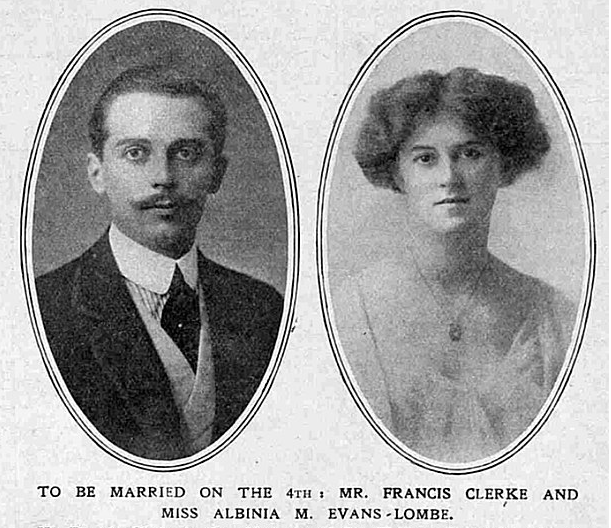

(Daily Sketch, 4 October 1911, no. 975, p. 16)

Wife and children

In 1911 Francis Clerke married Albinia Mary Evans-Lombe (1887–1972) of Bylaugh Park, Norwich, and they had two sons. After his death, she married (6 March 1920, in Cannes, France) Captain Anthony Henry Evelyn (“Harry”) Ashley (1894–1921); and then finally (1923) Group-Captain (later Air Chief Marshal) Edgar Rainey Ludlow-Hewitt, GCB, GBE, CMG, DSO, MC, Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, DL (1886–1973). Clerke and his family lived at 46, Lennox Gardens, before moving to 3, Cranley Gardens, London SW; after her marriage to Ashley, Albinia lived at Westbrook House, Bromham, near Devizes, Wiltshire, and stayed there for the rest of her life.

Albinia Mary was the elder daughter of a wealthy Norfolk landowner, Major Edward Henry Evans-Lombe (1861–1952) and Albinia Harriet Evans-Lombe (née Leslie-Melville) (1862–1956) (m. 1886) of Bylaugh Park, Thickthorn and Marlingford Hall, Norfolk.

Albinia Mary Evans-Lombe (1887–1972)

(Photo courtesy of Alan Robinson Esq.; photo © the descendants of Anthony Henry Ashley)

Clerke’s older son, John Edward Longueville (from 1930 Sir, the 12th Baronet of Hitcham; 1913–2009), was educated at Eton College and Magdalene College, Cambridge. He married (1948) Mary Beviss Bond (1924–98; marriage dissolved in 1986): one son, two daughters. He gained the rank of Captain while serving in the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry (Territorial Army), fought in World War Two, and was invested as a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in 1948. Mary Beviss Bond was the daughter of a professional soldier.

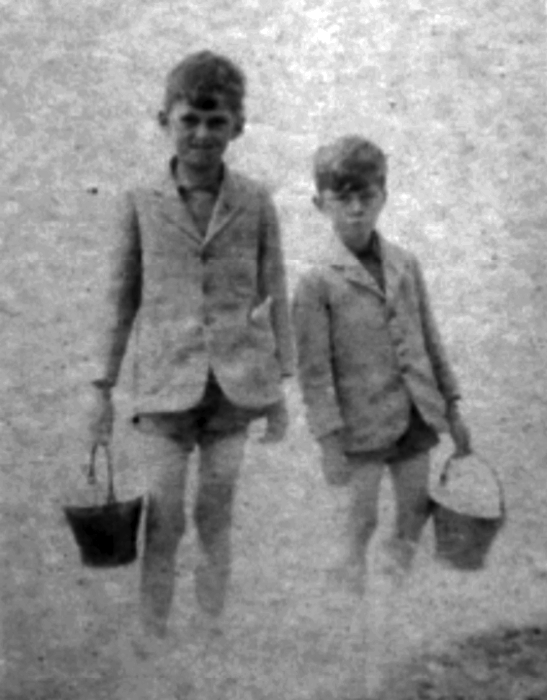

John and Rupert Clerke (c. 1923)

(Photo courtesy of Alan Robinson Esq.; photo © the descendants of Anthony Henry Ashley).

I am told that the families of both Clerke and his brother officer Harry Ashley generally believe that Clerke’s younger son, Rupert Francis Henry (later Group Captain, DFC; 1916–88), was the natural son of Ashley, his future stepfather by his mother’s second marriage in 1920. If this is the case, then Rupert, who was born in April 1916, must have been conceived in about July 1915, i.e. a month before Clerke joined the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards in which Ashley had been serving since the outbreak of war. Rupert certainly remembered Harry Ashley, and under the terms of his mother’s will was the son to inherit a number of Ashley’s personal possessions, including family silver, furniture and letters from the Prince of Wales, of whom Ashley was an exact contemporary and friend at Magdalen. Unfortunately, many of those letters were destroyed and only a few from 1913 and 1914 have survived (see the Bibliography at the end of Ashley), which are now owned by one of Rupert’s two daughters. Like his elder brother, Rupert was educated at Eton College and Magdalene College, Cambridge. He married (1945) Ann Jocelyn Tosswill (1921–2000; marriage dissolved in 1972): one son, one daughter. He then (1975) married Pamela Emily Bayliss (1925–99). He fought in the RAF in World War Two.

Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt was the second son of a clergyman; after beginning his military career as an officer in the Royal Irish Rifles (1905–14), he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. He became the Commanding Officer of No. 1 Squadron, then of No. 3 Squadron, then of 3rd Corps Wing, and by the age of 31 he had reached the rank of Brigadier. He served as the Head of the Staff College (1926–30), Deputy Chief of the Air Staff (1933–35), Air Officer Commanding India (1935–37), Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command (1939–40) and Inspector-General of the RAF (1940–45).

Education

From 1896 to 1899 Clerke attended The Evelyns School, Colham Green, Hillingdon, Uxbridge, Middlesex (1872–1931), which was run by Godfrey Thomas Worsley (1842–1920) (cf. R.A. Perssé, C.A. Gold, R.P. Stanhope, E.G. Worsley, T.G. Rawstorne, J.F. Worsley). He then attended Eton College from 1899 to 1905 and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 March 1905, having taken Responsions in Hilary Term 1905. But he then left without a degree in March 1906 and worked for Barclays Bank. There are no records of Clerke’s early activities with Barclays, but by the time of his mobilization in August/September 1915 he was Assistant to the Local Director of the branch at 19, Fleet Street (formerly Goslings Bank). This was quite a senior position since the customers of Goslings, established at the above address in 1650, included many members of the aristocracy, lawyers, famous literary men, national figures such as Clive of India and Benjamin Franklin, newspapers such as The Times, and various other longstanding organizations. In 1896, Goslings was part of the amalgamation that created Barclays & Co. Because the value of the deposits at the Fleet Street branch was so high, it was the only branch of Goslings in the district and the firm’s local head office. Similarly, because the business of the district consisted mainly of high-class private and professional accounts, the directors of the Fleet Street head office were all members of the Gosling family until the late 1940s. So Clerke was working for the family bank that at one time had his great-grandfather as a partner.

Francis William Talbot Clerke

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

War service

Clerke attested for the Special Reserve of Officers on 8 September 1915 and joined the Coldstream Guards at Windsor on the following day. On 14 September 1915 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of that Regiment (London Gazette, no. 29,300, 17 September 1915, p. 9,232). Although the War Diary of the 2nd Battalion does not record the names of new officers, and although Clerke’s medal card does not contain his disembarkation date, his father told President Warren in a letter of 24 October 1916 that he went to France in January 1916, and Ross-of-Bladensburg’s detailed history of the Coldstream Guards 1914–18 first mentions his name in March 1916 (p. 425). Moreover, the letter that Clerke’s Colonel wrote to his parents after his death suggests that he had been with the Battalion for quite some time. During his time with the Battalion, Clerke became the Battalion’s recognized expert on the use and care of the Lewis Gun, a medium machine-gun that started to be issued to British units in autumn 1915. So during his time with the Battalion, Clerke would have attended a course away from the Battalion that lasted several weeks.

The 2nd Battalion had been in France since 13 August 1914 as part of the 4th Guards Brigade (2nd Division), and after seeing action in the Champagne area during the Retreat from Mons, it was sent to the Ypres Salient where it fought in the First Battle of Ypres. On 20 August 1915, the 4th Guards Brigade became the 1st Guards Brigade in the newly formed Guards Division. From 28 August 1915 to 21 September 1915, the 2nd Coldstreams were in billets at Verchocq, about 13 miles south-west of St Omer, and when the Battle of Loos began on 26 September 1915, the Battalion was in reserve in the old British front line at Loos. But late on 26 September the Battalion moved into the new British front line, and at 16.00 hrs on 27 September it participated in the Divisional attack on Hill 70 as part of the 1st Guards Brigade, on the left of the line, losing 21 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing. It stayed in line until 30 September and helped to consolidate the new position by bringing in wounded and collecting large quantities of discarded arms and equipment. During its brief first period on the Loos front the Battalion was subjected to heavy shelling and lost a total of 29 ORs killed, wounded or missing, a very low number of casualties in comparison to the other Battalions of the Guards Division. The 2nd Battalion was in the trenches near Loos once more from the evening of 3 October onwards and helped to beat off the bloody German counter-attacks that took place on the afternoon of 8 October (see Ashley for a description). But by the end of October the fighting on this sector of the front had died down, and on 26 October the entire Division, including the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, was moved c.11 miles northwards, to positions at St-Hilaire near the town of Estaires and six miles south-west of Armentières, an even more quiet sector of the front. The 2nd Battalion remained here until 17 February 1916, losing 55 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing during this three-and-a-half-month period.

From 17 February to 17 March 1916 the Guards Division was in reserve west of Poperinghe, in the Ypres Sector, and on battlefield courses near Calais, after which it took over from the 6th Division in the Ypres Salient itself, defending a line of badly damaged and waterlogged trenches that extended in an arc from the village of Boesinghe, two miles north of Ypres, to Hooge, about three miles to the east of the city. The three Brigades each spent a 14-day stint in line, followed by a week in reserve, and although no major pitched battles took place during this period, a persistent and considerable amount of shelling, sniping and raiding took a steady toll of casualties in the attempt to straighten out the front line, which lasted until 20 May 1916.

But in late July 1916 the Guards Division began to move southwards in the direction of the battlefields of the Somme and by 1 August 1916 it had concentrated in Doullens. On 10 August 1916 the Division took over trenches to the south of Hébuterne, at the northern end of the British line and to the south-west of Gommecourt. The move was completed by 14 August, by which time the Guards Division was positioned in the trenches running through Ginchy Wood. The village of Ginchy, two miles south of Flers, is situated on a high plateau running northwards for 2,000 yards, and then eastwards in a long spur for nearly 4,000 yards. The village of Lesboeufs is a mile and a half south of the village of Gueudecourt and stands on the northern end of the spur, with the village of Morval on its southern end. Morval is two miles from Lesboeufs, two miles north-east of Ginchy, and commands a good view in every direction. Another spur juts out from the plateau for a mile in a south-easterly direction and then falls sharply into the Combles Valley towards Falfemont Farm (see W.L. Vince). Bouleaux Wood, a mile to the west of Combles, is on the crest of the spur, with Leuze Wood in front of it and lower down. The British extreme right at Leuze Wood was 2,000 yards from Morval and in between there lay a broad, deep branch of the main valley that is overlooked by Morval and flanked at its head by the high ground east of the valley that looks down into it. The Guards Division was positioned opposite this area, with the 6th Division on its right and the 56th (1/1st London) Division on its left, and was tasked with taking Lesboeufs, an impossible undertaking should the other two divisions prove to be unable to clear the two flanks and take Morval and Bouleaux respectively. Within this strategic situation, the 2nd Coldstreams were positioned in Ginchy Wood, with the Coldstreams’ 3rd Battalion (1st Guards Brigade) and 1st Battalion (2nd Guards Brigade) on its left and right respectively, the only time in the history of the Regiment when all three Coldstream battalions took part in a major front-line action together.

When, at 06.20 hours on 15 September, the opening day of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, the 1st Guards Brigade emerged from Ginchy Wood to attack the strong point that was known as the Triangle, 600 yards away, together with the trench that fed into the Triangle from the north that was known as the Serpentine, it came under very heavy machine-gun fire from the sunken road that went from Flers to Ginchy and suffered very heavy casualties. Nevertheless, with very little support from the half dozen tanks that managed to reach the starting line – four of which had got lost or become unserviceable – the sunken road had been cleared and both primary objectives had been taken by 07.15 hours. By 11.00 hours, and despite a heavy hostile barrage, the advance had moved forwards by another 600 yards, and taken another objective. But by this time, only three of the 2nd Battalion’s officers were still intact and functioning: its Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Laing, and Lieutenant William George Edmonstone, the eldest son of the 5th Baronet, who was killed in action later on in the day, aged 19. Ross-of-Bladenburg summarized as follows:

The situation then up to about 11 a.m. was roughly as follows: The Left group were consolidating in the captured trench, which they believed to be the third objective, or the Blue line, unwilling to make an assault on the final, or Red line, until their right was safe, the Right group in the same trench, some 500 yards to the east, were actively engaged in driving the enemy out of the part which was interfering with the Progress of the Divisional attack. In the Left ground, moreover, the men not belonging to the 1st Brigade [i.e. the Coldstream Guards’ 1st Battalion] had already been ordered to sideslip to the right to assist in clearing the line that lay between the two groups. But it was not easy to sort them out. The trench was crowded with troops belonging to almost every battalion of the two brigades, and with only a very small percentage of officers; it was blocked by many who were wounded, it was subjected to heavy fire, and consolidation could not for a moment be suspended […] – then it was discovered that the line captured was not the third, but the first or Green line.

So the Coldstreams’ 2nd Brigade, consisting of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, was ordered forward, to Lesboeufs church, only to be checked by machine-gun and artillery fire. But Colonel Campbell of the 3rd Battalion rallied them with a hunting-horn (as his father had done on 28 March 1879 during the Zulu War), for which he earned the Victoria Cross, and by 11.15 hours they had taken their objective and gone 600 yards beyond it. But once again, the attackers thought that they were further on than they actually were – in the Blue line, the third objective – when they had in fact only reached the Brown line, the second objective. So the surviving Guards had to consolidate for the night, drive off counter-attacks, and hold on in defensive positions until dawn on 17 September. Between 10 and 17 September 1916, the Guards Division lost 4,964 of its men, of whom 172 were officers; the three Coldstream battalions lost 40 officers and 1,326 ORs killed, wounded or missing; and the 2nd Battalion lost 446 men killed, wounded or missing, of whom 167, including seven officers, were killed in action. But Clerke was not one of the casualties and after the action he was appointed the Battalion’s Acting Adjutant.

The village of Morval, captured by elements of the British 4th Army on 25 September 1916 during the Battle of Morval (25-28 September) 1916). Clerke took part in this action before being killed in action at Lesboeufs on the following day.

So on the night of 18/19 September 1916, a replacement draft of 200 men and four officers joined the 2nd Battalion, At 18.00 hours on 20 September, the reconstituted 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Coldstream Guards moved up into the captured German Blue line and spent the next four or five days digging communication and assembly trenches. Then, on 25 September, the 2nd Battalion, still in 1st Guards Brigade, elements of the Guards Division, took the village and the road linking it with Gueudecourt, about 6 miles to the north-west-north. This time, the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards was held in reserve so did not see any action until 12.35 hours, when they helped to clear the village and trenches of Lesboeufs, about 11 miles to the north of Albert. Clerke survived this action but was killed in action, aged 30, at about noon on 26 September 1916 in the trenches near Lesboeufs when an enemy shell scored a direct hit on the grenade store. It also killed Major Harry Wilson Verelst, MC, aged 26, and Lieutenant John Atholl Macgregor, MC, aged 36. All three officers were initially buried on the western side of the sunken road at Lesboeufs but now have no known grave and are commemorated on one of the several Special Memorials that were put up in the Guards’ Cemetery, Lesboeufs. Clerke left £1,656 18s. His wife received a gratuity of £100 and a pension of £100 p.a. (which went up to £140 p.a. in 1917) and his sons each received a gratuity of £33 6s 8d and an allowance of £24 p.a. Clerke’s father wrote to President Warren on 24 October 1916 and said: “I do indeed feel very proud of my son for having laid down his life for us and his country[,] but the personal sorrow remains all the same.”

The original Guards Cemy at Lesboeufs (c. 1919/20). At the time of the Armistice, the Cemetery contained only 40 graves, but its size gradually increased as bodies were discovered or transferred from smaller cemeteries in the surrounding area.

The modern Guards Cemetery at Lesboeufs (2015) was designed by Sir Herbert Baker (1862–1946) and contains or commemorates 3,136 casualties, of whom about a third are unidentified

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Alan Robertson Esq. and the families of both Clerke and his brother officer Harry Ashley for providing us with genealogical information and photographs.

Printed sources:

Ross-of-Bladensburg (1928), vol. i, pp. 425–88.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. R.E. Henderson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 44,117 (12 November 1925), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘Sir W.F. Clerke’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,576 (28 July 1930), p. 14.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt’ [obituary], The Times, no. 58,863 (17 August 1973), p. 16.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 52.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 100–1 and 115.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/311-312 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to F.W.T. Clerke [1916]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/56.

WO95/1215.

WO95/1342/2.