Fact file:

Matriculated: 1909

Born: 24 March 1890

Died: 8 May 1917

Regiment: Royal Warwickshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Orchard Dump Cemetery: IX.A.47

Family background

b. 24 March 1890 as the younger son of Charles Anthony Vince, MA (1855–1929) and Janet (Jenny) Vince (née Lang) (b. c.1858 in Paisley, Scotland, d. 1944) (m. 1886). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at Mill Hill School, London (two servants); at the 1901 Census at 285, Gillott Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham (four servants); and at the 1911 Census at 8, Lyttleton Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham (two servants).

Parents and antecedents

Vince’s paternal grandfather, Charles Vince (1823–74), was the son of Charles Vince (b. c.1790), a carpenter of Farnham in Surrey. He left school early and became an apprentice to Mason & Jackson, the firm for which his father worked, and joined the local Mechanics Institute. But even as a youth he had always read much, and even when training as an apprentice he maintained “a strong interest in intellectual pursuits”. Although he came from a Congregationalist family, he decided, “when he came to think for himself” and after several years of deliberation, that the teaching of the Baptists was closest to his own beliefs. Consequently, in 1848, he began to study for the Baptist Ministry at Stepney College, and in 1852, when only 29, he became the Minister of Mount Zion Baptist Chapel, Graham Street, Birmingham, where he worked for 22 years, “never daring to sever the bond which had grown up between himself and [his parishioners]”, by whom he was held in special esteem. Writing of his work as a pastor, his obituarist described him as “a Puritan without Puritan sternness” and “a saintly character” whose humility, natural sweetness, wide sympathies, and large and tender charity “ensured him not merely the regard or the liking, but the love of all who came into personal association with him”, and considered him “one of the best men who has ever lived and laboured in Birmingham”.

Charles worked for a time as the Editor of the leading Baptist magazine The Freeman (1855–99; merged with The Baptist Times until it ceased publication in 2011). He also published two books: one, entitled The Character of Christ: An Argument for the Historical Verity of the Four Gospels, was based on a series of lectures that he had given in 1864 for the Young Men’s Christian Association in London’s Exeter Hall, on the north side of The Strand (built 1829–31; demolished 1907 and replaced by the Strand Palace Hotel); and the other, entitled Lessons from the Life of David, appeared in 1871. But, his obituarist stressed, despite his learning,

his great strength lay not in literature, but in preaching and speaking […] for he had the rare natural gift of adapting himself, as without effort, to all audiences: he was at home amongst the humblest as amongst the most cultivated and refined, and could move either to tears or laughter, or sway them to passion, at his will.

Besides being “much in demand” as a preacher and lecturer in all kinds of venues all over the country, Charles was “a sort of bishop” in the wider Baptist community: he possessed the “faculty of wise counsel” and was frequently “consulted by Baptist churches in their choice of ministers, and by ministers in the difficulties encountered in their work”. At the same time, he was also a passionate proponent of those policies of social and educational reform which made nineteenth-century Birmingham into a model of municipal government, and in his obituarist’s view he brought his “leading characteristic”, a “perfect and instinctive charity”, to bear as much on matters secular as on matters religious, with the result that he numbered many political opponents among his friends. Charles was a committed Liberal all his adult life and was elected one of that party’s members of the School Board when it was founded in 1870. He was also, for a time, a member of the Town Council, the Free Libraries Committee, and the Committee of the Old Library, and stood for much more besides with the result, according to his obituarist, that “wherever there was work to be done, reform to be promoted, wrong to be redressed, public sympathy to be aroused, or public energy to be stimulated, there Mr. Vince was to be found”. But the same obituarist was also of the opinion that the stress caused by Charles’s incessant and many-sided work had a profoundly deleterious effect on the health of a man who was “endowed with a peculiarly sensitive and even anxious temperament” and possessed a “deep sense of responsibility”: “he did too much for even a robust man to endure with impunity”, and the ultimate result was an early, long-drawn-out, and painful death.

Charles Vince, by Henry Joseph Whitlock, albumen carte-de-visite (1860s) (Photographs Collection (NPG Ax18308); copyright National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London, given by Phyllis Cunnington, 1962)

Vince’s paternal grandmother was Hannah Mayhew (1823–1917), the daughter of John Mayhew (1785–1853) bank agent and draper of Beccles, Suffolk.

Vince’s maternal grandfather was probably William Lang (b. c.1824, d. after 1901), the husband of Janet Lang (b. c.1825, d. after 1901), a tanner/leather merchant of Paisley (just west of Glasgow), Renfrewshire, Scotland.

Vince’s father was one of the first batch of boys to enter King Edward VI School, Birmingham, via an admission examination rather than by a Governor’s recommendation, and he went on to play “a prominent part in the varied activities of the School”. He revived the School Chronicle, he was a frequent speaker at Debating Society, he was Librarian and he was a member of the School XV. Versatility was his hallmark and an obituarist would describe him with complete justification as a “Scholar, Schoolmaster, Preacher, Man of Letters, Politician, and Man of the World”. After leaving King Edward’s, he became a Classical Scholar of Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he won the Porteous Medal for a Latin Dissertation and rowed in his College VIII. In 1878 he was appointed Composition Master at Repton and in 1880 he was elected to a Fellowship at his old College. From 1886 to 1891 he was the Headmaster of Mill Hill School, London, but the lure of politics was too great and after the general election of 1892 he returned to Birmingham at the personal behest of Joseph Chamberlain (1836–1914) (see N.G. Chamberlain), to become Secretary of the city’s Liberal Unionist Association until his retirement in 1919. As such, he played a major part in Chamberlain’s tariff reform campaign of 1903 and actually published a book on the subject with a preface by Chamberlain, whose ideas and personality he greatly admired: “No man could have desired a more considerate chief. It was characteristic of Mr Joseph Chamberlain that when he gave you his confidence, he gave it freely.” During World War One, he was Secretary of the Imperial Tariff Committee in Birmingham. He also served on the City’s Library Committee, he was President of the Central Literary Association and the Dramatic and Literary Societies, and he preached regularly. He translated Demosthenes’ De Corona and De Falsa Legatione, published a volume of sermons, wrote a monograph on the liberal and radical statesman John Bright (1811–89), authored the third and fourth volumes (1902) of J. Thackray Bunce’s four-volume History of the Corporation of Birmingham (1878–1923), and was working on a Latin Grammar at the time of his death. An obituarist concluded:

To know him was a liberal education. He had a wonderful memory; his tastes in literature were catholic; he was probably one of the best Italian scholars in the city; he was always willing to help in any difficulty; and if, as was seldom the case, he could not solve your problem at once, he could always put you on the track of such books as would help you.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Charles (1887–1976); married (1915) Emily (Millie) Millicent Cohen (1868–1941);

(2) Margaret Ellen R. (1899–1903).

Charles attended King Edward VI School from 1899 to 1906 and then joined the staff of the Birmingham Gazette, where he became a well-regarded leader-writer. During World War One he served for a time with the Royal Sussex Regiment, and after being invalided out he worked for the Intelligence Directorate at the War Office. In 1920 he joined the Royal National Lifeboat Institution as Assistant Secretary (Publicity), remained in charge of its publications until his retirement in 1953, and in 1946 published Storm on the Waters, an account of the lifeboat service during World War Two. In 1958 he donated the money that enabled his old school to build Vince House, the Headmaster’s residence, in memory of his father.

Emily Millicent Cohen was the daughter of a Hamburg-born watchmaker and diamond dealer and a Scottish mother, and her family lived for many years at 27, Frederick Street, Birmingham, in the city’s Jewellery Quarter. She began her professional career as a secretary and by 1901 had set up her own typewriting agency. But by 1908 she was running her own interior design business from Oakley House, 14–18 Bloomsbury St, London, not far from the home of Agnes Garrett (1845–1935) at 2, Gower Street. It seems that Emily Millicent had learnt her trade from Agnes Garrett who, besides being a noted campaigner for women’s rights, was the first woman to set up her own interior design company. Emily Millicent dedicated her Decorating and Care of the Home (1923) to Agnes, and her book owes much to Rhoda and Agnes Garrett’s House Decoration (1875), emphasizing light and simplicity. She published two more books: Furnishing and Decorating Do’s and Don’ts (1925) and Practical Home Decorating (1932).

Education

Vince attended King Edward VI School, Edgbaston, Birmingham, from 1901 to 1909, where he was a Foundation Scholar from 1902 to 1908. Unlike the other members of his year who gained places or awards at the older universities, Vince, in common with his father and elder brother, was not narrowly focused on academic work and his character as an “all-rounder” emerges very clearly from his long list of achievements while at school. He was a Prefect 1907–09, the Secretary and Sub-Treasurer of the Literary Society 1907–08, the Captain of Fives in 1908, a member of the First cricket XI 1908–09 (Vice-Captain 1909), the Captain of his House’s Fives team 1906–08, the Captain of his House’s cricket team 1909, a Sub-Librarian 1906–08, the Librarian 1908, the Editor of the King Edward’s School Chronicle 1908–09, a Sergeant in the school’s Officers’ Training Corps (of which he was one of the first members), and Captain of School and General Secretary of the School Club from January to July 1909. In 1908 and 1909 he participated actively in the school’s Debating Society, and on Speech Day 1909 he took part in the school’s Greek play, received prizes for Latin Verse and English Recitation and a bronze medal for gymnastics, and was awarded the Dale Memorial Medal (initiated in 1899 in memory of Dr R.W. Dale, old boy and governor, and awarded to “the pupil of the school most distinguished during the previous year for scholarship and good conduct”). As a cricketer, he was a vigorous if erratic batsman who was capable of following a duck in one game with over 70 runs in the next, and as a debater his views tended to the conservative and were often sarcastically expressed. He seems to have had a reputation for getting things done, for when he became Librarian, the Editor of the Chronicle remarked: “Under W.L. Vince’s management the Library should continue to flourish as it has done in the past”, and after the school’s Officers’ Training Corps had taken part for the first time in the Public Schools’ Camp at Tidworth in July 1909, the Chronicle noted: “Our thanks are due also to Sergeant Vince, who attended to his duties and became efficient, while carrying out the onerous work of School Captain.” When, as Secretary of the School Club, he reported on its activities in 1909, his values were very evident from the following:

It has been a year of many successes and few disappointments. The various sections of the Club have flourished, the teams have had good records, while the keenness that has been shewn is a very healthy and promising sign for the future. One exception and one only must be mentioned and that is the Debating and Literary Society, where the energy of the officials has met with very poor support. It is a good sign of the healthy state of the Club that very few reforms have been found necessary. The most important is undoubtedly that made by the Library Sub-Committee, where a stand has at least been made to prevent the abuses which have grown up of late years and have led to the loss of a considerable number of volumes.

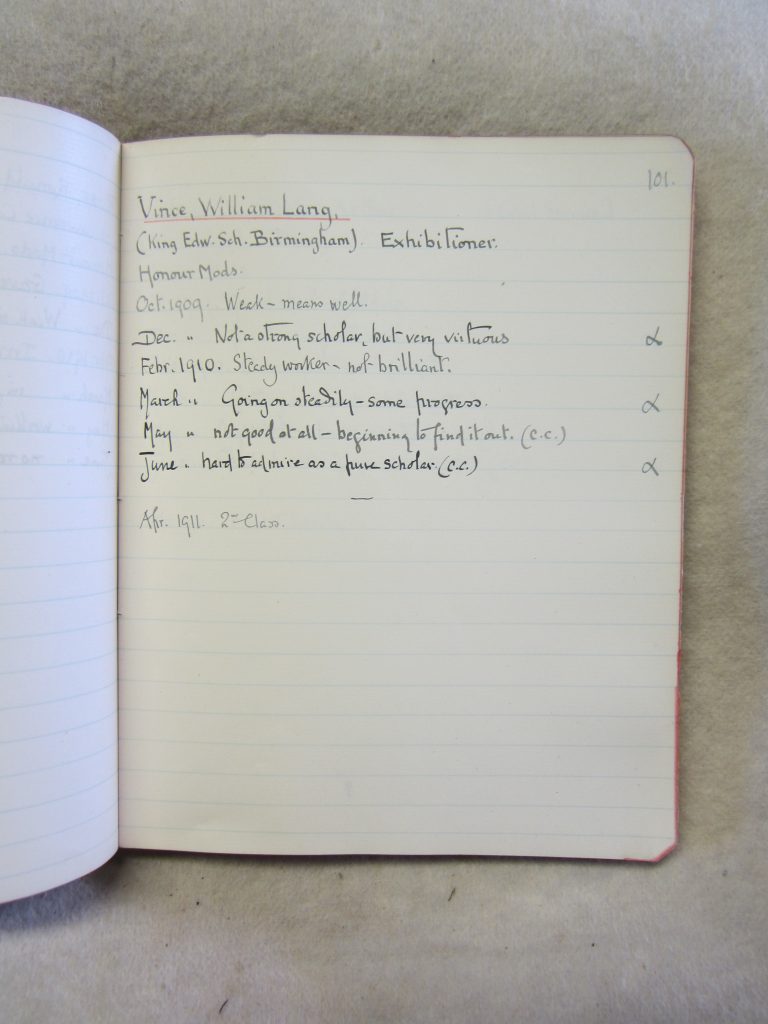

Vince’s academic record (1909–11), compiled by H.W. Greene et al. (Magdalen College Archives: F29/1/MS5/5: Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895–1911], p. 101)

But overall, Oxford clearly made a significant impression on Vince, and on 15 May 1917, i.e. a week after his death in action, Vince’s father acknowledged this when he responded as follows to a letter of condolence from President Warren:

We are very grateful to you for writing so fully and so kindly about our boy: such testimony is precious to us, and will be linked in our minds with memories that have become sacred. – It seemed to me that all the time he was at Magdalen he was growing steadily in intellectual and moral strength without losing his boyish simplicity and modesty; and though in a sense whatever promise he gave of usefulness has become part of the enormous wastage of the war – we must always be grateful to his college & his university.

William Lang Vince, in Magdalen College Rugby Team 1912–13 (Courtesy Magdalen College) (Courtesy Magdalen College)

War service

Having served for four years in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps and passed Certificate ‘A’, Vince, who was 5 foot 7 inches tall, returned to Oxford as soon as the war broke out to apply for a commission. But, as his father recorded in his letter of 15 May 1917, it was not successful,

as the Oxford doctor discovered and reported a trifling varicose vein – and at that time the W[ar] O[ffice] had no anticipation of the number of officers they would shortly want – In Birmingham, however, three new battalions, from which manual workers were excluded, were raised [by the Lord Mayor and a local committee] and equipped by public subscription. The first C.O. of the First City Btn. (= 14th Royal Warwicks) was my friend Sir John Barnsley [1866–1908], an old Volunteer Colonel (now Brig[adier] General). I sent Willie to Barnsley, who was glad to have the help of an Oxford O.T.C. man, and got him a commission without difficulty.

So on 29 August 1914 Vince was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 14th (Service) Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, also known as the 1st Birmingham Battalion (London Gazette, no. 28,961, 3 November 1914, p. 8,883), and assigned to XII Platoon in ‘C’ Company. From 5 October 1914 to 25 June 1915, the Battalion was stationed at Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire, where it trained as part of the 95th Brigade, 32nd (New Army) Division, and during this period, on 27 January 1915, Vince was promoted Lieutenant (LG, no. 29,143, 26 April 1915, p. 4,051). According to his father, “he was remarkably popular with the men” and

contributed a great deal towards keeping the battalion amused and in good spirits during the time of training – which was prolonged to weariness – partly because (the men being for the most part fairly well educated) their n[on-]c[ommissioned] officers were constantly getting commissions in other battalions.

From 25 June to 28 July 1915 the Battalion was under canvas at Wensleydale, taking part in brigade and divisional manoeuvres, after which it spent a week at Hornsea, on the east coast of Yorkshire, learning how to fire rifles. On 5 August, it went to Codford, on Salisbury Plain, where it took part in more manoeuvres and trained in trench warfare with rifles. The Battalion crossed to Boulogne during the night of 21/22 November 1915, travelled by train to Condé-Folie, on the Somme about eight miles south-east of Abbeville, after which it marched nine miles north-westwards in icy and difficult conditions to Vauchelles-les-Quesnoy, an eastern suburb of Abbeville, where it rested for four days. By early December the Battalion was at Sailly-Laurette, some seven miles south of Albert on the Somme, and had its first taste of the trenches in the valley to the east of Albert that runs from Fricourt to Maricourt. The Battalion War Diary reads:

At length we reached what looked like an open drain full of mud. This, we were informed, was the front line. Sentries were posted and we began the night’s vigil in surroundings completely strange, and with no idea of what might appear out of the darkness. The situation was very different from what we had imagined. We seemed to have reached the depth of misery. It was a cold, dark night, and there we were squatting on a wet fire step with no shelter of any description. Later on we treated such a case as all in a day’s work, but as yet we knew nothing. […] practically no rations, at any rate no hot rations, came up for us during this time: so that with little food and in the appalling living conditions, our first visit to the trenches was not the soul-stirring adventure we had hoped for.

On 15 December 1915, the Battalion took over a sector of trenches at nearby Carnoy for three days, then withdrew south-south-westwards to Bray-sur-Somme and Froissy, and returned to the front line from 27 to 31 December 1915. In the New Year, the Battalion was transferred to 13th Brigade in the 5th Division on the principle that New Army troops should be distributed among more experienced battalions. On 8 January 1916, the Battalion was pulled out of the line for two months to train at Vaux-sur-Somme, six miles west of Bray-sur-Somme, and on 10 March it began a six-day march via Villers-Bocage, Doullens, Grand Rullecourt, Agnez-les-Duissans and Duissans to the trenches outside St Nicholas, a northern suburb of Arras, where it stayed for six weeks. Then, after a week’s rest, the Battalion took over the left sub-sector in front of Roclincourt, just to the north-east, and held this part of the line until 21 June 1916.

On 3 July, the third day of the Battle of the Somme, the 5th Division set off for Le Cauroy, rested until 13 July, then marched for six days via Franvillers and Méaulte, just to the south of Albert, to the trenches at Montauban-de-Picardie where, on 20 July, it took over the second line for two days in preparation for the Battle of Pozières Ridge (23 July–3 September) and was subject to heavy shelling. At 21.50 hours on the evening of 23 July, after an artillery barrage, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of the 14th Battalion and elements of the 1st Battalion, the Royal West Kent Regiment, attacked Wood Lane, the German trenches along the track that ran 400 yards in front of the British trenches from the south-east corner of High Wood, i.e. over the same ground where J.B. Hichens and his Battalion had taken such heavy casualties on 15 July 1916 and where their bodies were probably still lying, and where the same fate awaited J.A.P. Parnell and his Battalion on 8 September 1916. The attack of 23 July was meant to be a vital preliminary to the assault on the German trench that ran along the ridge to the east of High Wood and was known as the Switch Line. Although the attacking troops made good progress for the first ten minutes, they were caught in the light of flares while moving up the ridge towards Wood Lane and enfiladed by machine-gun fire from the south-west corner of High Wood, which caused the loss of 16 officers and 469 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing. The 14th Battalion was then pulled out of the line, reinforced, and sent back to the trenches on 29 July just to the right of its previous positions, and at 17.50 hours on the following day the Battalion’s ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies took part in the attack on Longueval but made little headway because of machine-gun fire and lost another six officers and 165 ORs killed, wounded or missing – i.e. 640 men within eight days. The remains of the Battalion, including Vince, then marched south-west to Dernacourt, just outside Albert, and the War Diary reads:

The First Birmingham Battalion had practically ceased to exist, for very few of the original officers and men were left. When the division was relieved, 16 officers and 289 other ranks constituted the full strength of the battalion. Comrades of many months had disappeared, the fate of many was unknown, and many were gone beyond recall.

Vince’s father would later comment in his letter to President Warren:

It has not been a lucky battalion: it suffered so severely [so] many times that it long ago lost its special character as a body of Birmingham clerks and the like: hardly any of the original officers are now left, and it has never taken part in any big success. The first time they were badly cut up [which must mean 23 July 1916], Willie was away in a training school in France, with a view to a captaincy – & returned to find nearly all his best friends out of action. – Later [almost certainly 29 July 1916], he was one of three officers only of the btn. who came out of a hard day’s fighting unhit.

On 4 August, the Battalion entrained for Étrejust, c.14 miles south of Abbeville, where it spent three weeks, training and taking on replacements. This period included 48 hours of leave for old members of the Battalion, and as these could be spent anywhere in France except Paris, most men went to Le Tréport, c.25 miles away on the coast to the north-east of Dieppe. On 24 August the Battalion returned to Dernacourt and spent the following day in “bivouacs near Bray, where we had had our first experience of trench warfare under the very worst conditions”. On 29 August 1916 Vince’s Battalion moved back into the front line and on 2 September it took up positions for the attack on the following day. The aim of this attack was the capture of the north-west/south-east line that ran from High Wood through Ginchy, Guillemont, Wedge Wood, and Le Forêt. As things turned out, the action lasted until 6 September 1916 and became known as the Battle of Guillemont. Vince’s 13th Brigade had two objectives: (1) the capture of the German strong-point at Falfemont Farm, a mile to the south-east of Guillemont, plus the main trench line for about 400 yards to the right, and (2) the capture of the German main line trenches from the left of Falfemont Farm up to and including Wedge Wood, a distance of about 450 yards. Furthermore, the attack on the first objective had to be completed in advance of the main attack in order to prevent the Germans, who were holding the Farm, from using their machine-guns against the left flank of the French 127th Regiment, who were on the right of the 13th Brigade and tasked with taking Combles. So at 09.00 hours the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers attacked Point 48, just to the left of the Farm, but suffered nearly 300 casualties and was forced to retire. The subsequent attacks by other elements of the 5th Division further over to the left were more successful, and by 13.00 hours the British had taken the German front line and second line, which extended north-westwards from Wedge Wood to the south-east edge of Guillemont. Vince’s 14th Battalion was held in reserve until 12.10 hours, when 13th Brigade used it and the 15th Battalion, The Royal Warwickshires, to make a second attack on Falfemont Farm even though both Battalions were open to concentrated rifle and machine-gun fire from the Farm. ‘C’ Company of the 14th Battalion attacked the gunpits that were positioned in the valley to the right of Wedge Wood, came under intense artillery, machine-gun and rifle fire, lost very heavily, and was held up. Nevertheless, it resumed the attack, and after repeated attempts it took the gun-pits and several prisoners at 13.40 hours. At 12.50 hours, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies attacked the second objective, and although both Companies suffered heavy casualties, ‘B’ Company on the left managed to occupy and hold the front German trench that looped around the south of Wedge Wood. Of this engagement Vince’s father wrote:

On Sept[ember] 3 last year, [the Battalion] were in an attack which failed entirely – by some blunder the artillery that was to support them did not arrive till it was too late. – Willie, then acting as Captain, took 120 men out of the trench, and brought back only 40 unhurt: he was chiefly distressed because he had only two couples of stretcher-bearers to collect his wounded.

Falfemont Farm was finally captured on 5 September 1916 after the Birmingham Battalion had lost two officers and 142 ORs killed in action or missing and seven officers and 152 ORs wounded, a total of 293 casualties. But Guillemont had been taken and the British line extended along the road that ran from Wedge Wood to Ginchy and then round the south of Ginchy. Although Vince received a superficial wound from shell fragments during this fighting, he did not report sick until 16 September, by which time the wound had become infected and he had become debilitated and developed mild diarrhoea – his father wrote “enteritis”. So two days later he was sent to hospital in nearby Corbie, and then, when the condition persisted, to No. 8 General Hospital in Rouen, where he was a patient from 20 to 25 September. From here he was transferred to No. 1 Southern General Hospital, Edgbaston, Birmingham, where he arrived on 28 September suffering from “debility caused by infection and enteritis” – a diagnosis which, according to his father, was changed by the doctors to “chronic colitis”. As his condition rapidly improved, he was discharged on 25 October but given three weeks of convalescence leave, which was extended thus enabling him to spend Christmas at home, “still on sick leave”. On 13 January 1917 Vince was declared fit for Home Service only, and according to his father “he was sent to a training battalion: first at Exmouth, then on Salisbury Plain”. He was not declared fully fit for active service until 20 March 1917. Meanwhile, on 29 September 1916, the 5th Division had moved further north for six months, to positions near Béthune and La Bassée, with the 14th Battalion stationed mainly in the area of Festubert and Givenchy. But on 23 April, i.e. two weeks after the beginning of the Second Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917, the Battalion was moved back near the front line, just north of Avian, and although the 14th Battalion’s War Diary makes no mention of Vince’s return, his father records that he returned to France on 18 April, where he seems finally to have returned to his old Battalion on about 24 April 1917. Vince wrote home “that he found a spirit of confidence in victory very different from what he had known last summer on the Somme”, and after a good week’s rest, the Battalion took up position in the trenches on 2 May 1917 somewhere between Arleux-en-Gohelle, Oppy and Roclincourt, where it lost six officers killed in action or wounded, 33 ORs killed in action, and 76 ORs wounded, mainly through shell-fire. Vince wrote his last letter home on Sunday, 6 May: “he had then been living in a dug-out for days”. On Tuesday 8 May 1917 he was standing in the trench somewhere between Oppy and Fresnoy-en-Gohelle, “talking with two other officers”, when a 5.9 German shell killed him instantaneously, aged 27, together with Captain Bernard Turner (1892–1917), aged 25 (another of the Battalion’s “original volunteers”), and Lieutenant Edmund Sproston Knapp Barrow (1882–1917), aged 34. His father’s letter then continues:

It is not a cheerful story: yet he always wrote cheerfully, complaining of nothing, blaming nobody – I have only one anecdote, which I think illustrates his own character (though he would never have told it if he had thought so himself). A young 2nd-Lieutenant – a boy barely of military age – had been sent from home to join the battalion: he had never been under fire, but was eager to fight. – He was ill, but hearing that the btn was to attack next day[,] he persuaded the doctor to send him to the trenches. But when the word was given to leave shelter & attack, the boy’s heart failed him and he stayed behind. After the fight[,] Willie found him in a terrible state of humiliation; and instead of reporting him for cowardice & disobedience, took pains to talk him back to his self-respect, attributing his failures – (justly as the event proved) to his malady. The next day the attack was renewed: the young officer was the first to leave the trench & fought with a courage & coolness that entirely won the respect of the men.

And later on, President Warren wrote of Vince:

Singularly modest and dutiful, he had ambitions more because he thought it his duty to have them, than for any selfish reason. He was much interested in public affairs, and he would certainly have made a very useful and probably successful man, for he had abundant sense and diligence, and an attractive and winning disposition.

Vince’s father concluded his letter as follows – at first pathetically and then very tellingly:

As for myself. I feel myself a rather useless person: but I am doing what I can as hon. sec. of the Advisory Committee – and I am in the National Service Committee: also on one which organises entertainments for wounded soldiers – I am glad you think that Birmingham has done well: and indeed I find the spirit of the people here all that we could desire. For this we owe much to the local Lab[our] & Soc[ialist] leaders who (with a few exceptions – & they have done us great harm) have behaved patriotically & helpfully throughout. The trouble among the engineers does not extend to Birmingham though we hear deplorable accounts of Coventry.

Vince and his two comrades are buried in Orchard Dump Cemetery, Arleux-en-Gohelle, in Graves IX.A.47, IX.A.23 and IX.A.46; Vince’s headstone is inscribed: “B.A. of Magd. Coll. Oxford. Son of C. A. Vince of Birmingham”. He is also commemorated on a memorial tablet in the War Memorial Chapel, King Edward VI School, Birmingham. He left £370 17s 7d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Charles Anthony Vince, M.A.’, The Old Edwardians Gazette and Year Book, 1928, 27, no. 138 (10 June 1929), pp. 9–11.

*R.G. L[unt], ‘Charles Vince’ [obituary], Old Edwardians Gazette, no. 214 (January 1975), p. 39.

Printed sources:

‘Mr Charles Vince’ [obituary], Birmingham Daily Post, no. 5,079 (23 October 1874), p. 5.

[Anon.], King Edward’s School Chronicle, 24, no. 177 (November 1909), pp. 73–81.

[Anon.], ‘Lieut. W.L. Vince Killed’ [obituary], Birmingham Daily Post and Journal, no. 18,395 (14 May 1917), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant William Lang Vince’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,478 (15 May 1917), p. 9.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 19 (18 May 1917), p. 256.

Bowater (1919), pp. 34–5, 62–3.

[Anon.], ‘Noted Unionist Dead’, The Scotsman (Edinburgh), no. 26,731 (30 January 1929), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. C.A. Vince’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,114 (30 January 1929), p. 2.

C[harles] A[nthony] Vince, ‘Latin Poets in the British Parliament’, The Classical Review, 46, no. 3 (July 1932), pp. 97–104.

Fairclough (1933), p. 192.

Patrick Howart, ‘Mr Charles Vince’ [obituary], The Times, no. 59,243 (13 November 1974), p. 18.

Carter (1997), passim but esp. pp. 222, 264, 284.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 56, 88–9.

Deborah Cohen, Household Gods: The British and their Possessions (New Haven: Yale UP, 2006), pp. 93, 105–9.

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 107–10 and 296.

Archival sources:

MCA: F29/1/MS5/5 (Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895–1911]), p. 101.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1176-1178 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to W.L. Vince [1917]).

OUA: UR 2/1/70.

WO95/1556.

WO339/12943.

On-line sources:

Elizabeth Crawford, ‘Mrs Millicent Vince: Pupil of Agnes Garrett and Interior Decorator’: https://womanandhersphere.com/2012/07/22/mrs-millicent-vince-interior-decorator/ (accessed 2.8.20).