Fact file:

Matriculated: 1904, Fellow from 1909

Born: 1 December 1885

Died: 12 May 1915

Regiment: Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Grave/Memorial: Le Touret Military Cemetery Memorial

Family background

b. 1 December 1885 at 5 Museum Villas, Oxford, as the elder son (of three children) of the Revd Canon John Octavius Johnston DD (1852–1923) and Harriette Louisa Johnston (née Mallam) (c.1847–1932) (m. 1884).

Parents and antecedents

Johnston’s father, himself the son of a clergyman, was a scholar and high churchman “who exercised no small influence in the Church of England, partly by his books and partly by his work in training ordination candidates”. He studied Classics at Keble College, Oxford 1874-78, was awarded a 1st in Theology in 1878, and was the curate of Kidlington from 1879 to 1881. In 1881 and 1884 he was the Principal of St Stephen’s House, Oxford, and from 1882 to 1895 he was Chaplain of Oxford’s women’s prison. From 1885 to 1895 he was Chaplain and Tutor in Theology at Merton College, Oxford, Vicar of All Saint’s, Oxford, and served as examining chaplain to successive Bishops of Oxford. In March 1895, he became the Principal of Cuddesdon Theological College and Vicar of Cuddesdon, near Oxford, where he stayed for 18 years; in 1891 the vicarage was staffed by three servants. He was also a Proctor in Convocation, an honorary Canon of Christ Church, and an examining chaplain for the Bishops of Lebombo and Calcutta. In 1913 he moved to Lincoln as Canon and Chancellor of the Cathedral. As a scholar, he is primarily remembered for helping to complete the four-volume life of Edward Bouverie Pusey (1800–82), one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement, that had been begun by Henry Parry Liddon (1829–90) and appeared in 1893–97; he also wrote a monumental biography of Liddon that appeared in 1904.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Gertrude Esther (1887–1971) (later Steer after her marriage in 1911 to Revd Reginald Pemberton Steer (1883–1953); five children;

(2) Hugh Liddon (1889–1968).

Reginald Pemberton Steer, Johnston’s brother-in-law, read for a pass degree at Magdalen from 1903 to 1907 (MA 1912). He then studied for the priesthood at Cuddesdon College, was ordained deacon, and served as the Curate of St Matthew’s, Bethnal Green, in 1910, and as the Curate of All Saints’ Church, Southampton, from 1910 to 1914. From 1914 to 1930 he was simultaneously the Vicar of Tidenham, in the Forest of Dean, on the western edge of Gloucestershire near Chepstow, Monmouthshire, and the Perpetual Curate of Beachley, some three miles south of Tidenham; during his time at Tidenham he was Rural Dean of the South Forest Deanery, Gloucestershire, from 1927 to 1930. From 1930 to 1935 he served as the Vicar of St Mary’s, Selly Oak, Birmingham, a living with a gross income of £452 p.a. and the cure of 8,186 souls, and Rural Dean of King’s Norton, Gloucestershire. From 1935 to 1943 he was Vicar of St Laurence’s Church, Stroud, Gloucestershire, and Rural Dean of Bisley, Gloucestershire. He was made an Honorary Canon of Gloucester Cathedral in 1937.

Reginald was also the brother of Gordon Pemberton Steer (1889–1915), who died on 26 December 1915 in the 14th General Hospital Wimereux, France, of wounds received in action while serving with the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Wiltshire Regiment.

Hugh Liddon studied Classics at Magdalen from 1908 to 1912 and was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations in 1910 and a 3rd in Greats in 1912. During World War One he served in the 5th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Rifle Brigade) alongside several other members of Magdalen, rising to the rank of Major, and winning the MC on 2 June 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,608, 2 June 1916, p. 5,574). He was ordained deacon in 1923, and in 1927, when he was the assistant curate at St Martin-in-the-Fields to the Revd Hugh Richard Lawrie (“Dick”) Sheppard (1880–1937), a well-known Christian pacifist and the future Dean of Canterbury (1929–31), he was invited to take charge of the BBC’s extremely popular quarter-of-an-hour Daily Service, and for three years he did so almost continuously. In 1931 he became Rector of Cranleigh, Surrey, and remained there until his retirement in 1962: he was remembered as “the perfect English gentleman in holy orders”.

Education and professional life

Johnston attended the Grange School, near Folkestone, Kent, from 1896 to 1899, and Radley College (Junior and Senior Scholarships) from 1899 to 1904. He played football in the School XI from 1901 to 1903, and rowed in the School VIII from 1903 to 1904, twice at Henley. According to his biographer (see below), he

applied himself to his school work with an obstinate resolution, and allowed no possibility of doubt as to his disapproval of what seemed to him idleness or frivolity […] Whatever he set out to accomplish he threw his weight in that direction, like a young bull charging.

It was these qualities that enabled him to win all the scholarships that were open each year to Radley’s sixth-formers (e.g. the James Scholarship and the Richards Gold Medal), and many prizes (e.g. the Worsley Prize, the History Essay Prize and the Latin Prose Prize). But his biographer added that his school work, which would have been mainly Latin and Greek prose composition and the study of Latin and Greek texts, was marked more by “strength of purpose” than by “a natural sensibility to the forms of language and literature”, and his headmaster recorded that his “intellectual output” at school was characterized by “solid ability” and “remarkable soundness of judgment” rather than “classic beauty”, “external grace or lightness or brilliance of epigram”. In December 1902 he was elected to an Open Classical Demyship at Magdalen, but being underage, he stayed at Radley until the end of the Summer Term 1904 and was the school’s Senior Prefect in his last year.

Johnston matriculated at Magdalen on 18 October 1904, was exempted from Responsions, and immediately awarded the Squire Scholarship (1904), a University award to the undergraduate intending to take Holy Orders who, in the trustees’ judgement, combined “the greatest ability with the greatest moral strength”. At Magdalen he made particular friends with Hubert Hector Smith and the socially concerned Edward Vivian Birchall. He sat his First Public Examination in Summer Term 1905 and Spring Term 1906, when he was awarded a 1st in Classical Moderations at the same time as E.H.L. Southwell – though by this time he had begun to find the grind of the Classics syllabus tiresome. Over the next two years he kept goal for the University in several football matches. In February 1905, together with R.P. Stanhope at No. 7, A.H. Huth at stroke and N.G. Chamberlain at No. 2, he rowed in Magdalen’s 1st Torpid, and in Spring Term 1906, together with Stanhope and A.H. Villiers, he rowed at No. 6 in the 1st Torpid – which was stroked by Huth and came Second on the River. On the first occasion Magdalen’s Captain of Boats noted: “Heavy & somewhat rough. Rather heavy with his hands over the stretcher, but swings & has promise”, and on the second: “The strongest worker in the crew; a Radley oarsman of experience who backs up stroke well, and always rows himself out.” In Summer Term 1906, he rowed at No. 6 in the Magdalen VIII that went Head of the River, and, presumably, attended the bacchanalian Bump Supper so graphically described by G.M.R. Turbutt. This crew had the sad distinction of being one of two Magdalen VIIIs to lose five of its nine members in the war. Southwell, Stanhope, A.G. Kirby and L.R.A. Gatehouse as well as Johnston would be killed in action or die as a result of wounds received in action; the second ill-fated crew was that of the 1907 VIII.

After Magdalen’s VIII had competed for the Grand Challenge Cup race at Henley in summer 1906 but lost to the Belgian crew, Magdalen’s Captain noted of Johnston:

A strong, even rather over-muscular oar, his muscles seem to be in the wrong places for rowing and he cramps his reach and quickness. He rowed well at Oxford. At Henley he was badly late very commonly throughout practice, but in the race he rose to the occasion, and was in time all over. His work is very effective when it comes on: he needs more lightness of touch and quicker leg drive.

In October 1906, Magdalen was confident that its crew would retain the Oxford University Boat Club Fours’ Cup with the same crew that had won in the previous year, but on the day before the races Gatehouse fell ill and Johnston, who had not rowed since Henley, offered “without hesitation” to take his place. Magdalen’s Captain commented:

Luckily [Johnston] was fairly fit, having played football for the college regularly; but as he had done no rowing since Henley he could hardly be expected to do himself justice. He rowed however with great energy and as usual was able to row himself well out.

In the first heat the Magdalen IV beat Balliol, but on the next day they lost to New College by only two feet in an extremely close race – the last occasion on which Johnston did any serious rowing for the College.

Surprisingly, perhaps, in view of Johnston’s intellectual temperament and commitment to academic work, he got on well with “the average hearty man” who was more typical of Magdalen’s undergraduate population during the late Victorian/Edwardian periods. During his final year he was a very good and popular President of Magdalen’s Junior Common Room. He was, for example, allegedly responsible for persuading the College to build “luxuriously appointed bathrooms” for its undergraduates. These activities, however, did not stop him being awarded a 1st in Summer Term 1908.

During Johnston’s undergraduate years, two experiences were of special importance for him. The first was the study of Philosophy with Clement Charles Julian Webb (1865–1954; Fellow and Tutor in Philosophy at Magdalen 1889–1922; first Oriel Professor of Christian Religion at Oriel College, Oxford, 1920–30). Webb was particularly concerned with the Philosophy of Religion and the societal aspects of religion, and a close friend and correspondent of Baron Friedrich von Hügel (1852–1925; naturalized British citizen in December 1914), the Austrian lay Catholic philosopher whose mother was English and whose major work, The Mystical Element in Religion, was published in 1908 (revised in 1923). The second key experience was his involvement with the Student Christian Movement (SCM). Originally founded in 1889 as the Student Volunteer Missionary Union – a “loose network of students dedicated to missionary work overseas” – it had been known officially as the SCM since 1905 but maintained Christian mission as its central concern. The SCM brought Johnston into contact with a variety of forms of religious faith, and during its summer camp in July 1908, at Baslow, in Derbyshire’s Peak District, Johnston decided that his long-term aim should be missionary or educational service abroad. But by this time, the SCM was becoming increasingly liberal in its theology, a trend which, as we shall see, would cause Johnston considerable theological difficulties.

Together with Maurice Powell, Johnston took his BA on 22 October 1908, and in the same month he returned to Oxford in order to work towards a Fellowship in Theology as a Liddon Scholar – a non-University scholarship that was awarded to the best man in the year who intended to be ordained. During the academic year 1908–09 Johnston lived at 15 Long Wall Street with Charles Ivo Sinclair Hood, who had also decided to become ordained and was spending a fourth year at Magdalen in order to take Greats. But as Johnston realized that the foremost theologians of the day were German, he arranged to spend the spring and early summer of 1909 learning German in Marburg, where Johann Wilhelm Herrmann (1846–1922), the last great German liberal theologian, was Professor of Systematic Theology. Although Johnston attended lectures by Herrmann and enjoyed many aspects of student culture and popular German life, he became very critical of the Germans. He described them in a letter as facially “hideous”, “gross burglars in flesh and soul”, a “morally and spiritually fat people” whose “civilization is barbarism”, whose customs are “beastly”, whose “applause and appreciation [in the theatre] is too bestially unrestrained”, whose “learning [is] a sin against nature”, and whose “religion [is] rank atheism” even though, “as [human] machines they’re gorgeous and colossal”. So by the end of his stay, he was eager to return to England, where he studied the work of English divines such as Christus Consummator (1886) by Bishop Brooke Foss Westcott (1825–1901).

On 5 October 1909 Johnston sat Magdalen’s Prize Fellowship examination and on 25 October he was elected to a Prize Fellowship – nowadays a Junior Research Fellowship – and assigned a room in Magdalen’s New Buildings. But at about the same time, when the number of Protestant missionaries to China was growing rapidly, especially from Britain and the USA, he became the paid Secretary of the United Universities Scheme (UUS) for the establishment of a Christian university in China, and he spent Spring Term 1910 working in the UUS’s office in Albemarle Street, London W1, and speaking around the country on its behalf. Of his Oxford friends whom he regularly saw during his time in London, four (Smith, Villiers, C.T. Mills and R.N.M. Bailey) would be killed in action.

At about the same time, when Johnston was preoccupied by the problems involved in the evangelization of China and the establishment of a Christian institution in an oriental culture, he was moved to write two complementary essays that relate to these issues. One, entitled ‘Modern Missionary Methods – A Question’, appeared in October 1910 in The East and the West: A quarterly Review for the study of Missionary problems, and the other, entitled ‘A Student’s Religion’, appeared in February 1910 in The Student Movement, the SCM’s house journal. The first begins by discussing how best to support contemporary missionary endeavour in a “westernizing” world where “self-support” by itinerants was no longer feasible and long-distance support “from home” was no longer desirable. The latter method of support, Johnston argued, permitted missionaries, especially Protestant missionaries who were “either authorised or sanctioned by trading companies”, to maintain a “superior style of livelihood” to the so-called “inferior heathen races” and generated an unacceptable and unchristian “superiority of attitude”. Consequently, he concluded, missionaries were needed who were both professionally qualified and who “would bring to their temporal work and life all the purifying and ennobling influences of religion, while adding to the force of their religious testimony the credential of efficiency in another sphere”. And in the second, Johnston set out three very high-minded aims for the student who aspired to do missionary work. During his studies, he must grow intellectually as well as morally and spiritually and not “use the ideas of [his] infancy to cover the experience of [his] manhood”; he must transform his childish relationship with his earthly father into something more complex; and he must view study “not as an incident”, but as an activity that enables “God to use our minds as the means of His revelation to us”.

In November 1910, Johnston accepted a three-year Lectureship in Theology at New College, Oxford, where he became a close friend of Edwyn Robert Bevan (1870–1943; later OBE and FBA), a quondam classical scholar of the College and a distinguished freelance academic who was an enthusiastic supporter of inter-faith contact and whose wide-ranging interests included archaeology, ancient history, and comparative religion. Bevan was made an Honorary Fellow of New College in October 1914 and after World War One it was he who wrote Johnston’s memorial biography – a book that is now so rare that it does not appear in the list of 29 book publications which concludes Bevan’s Wikipedia biography.

The lectureship did not start until January 1911 so Johnston was able to spend August to December 1910 working on behalf of the UUS in China and North America. He set out for China in early August 1910, and travelling via Canada and Japan arrived in Shanghai on 5 September. He then visited several cities in China that were served by “centres of Western education” – notably Shanghai, Nanking, Kuling, the Wuchang–Hankow–Hanyang group of cities (otherwise known as the Wu-Han centre), Changsha, Peking (now Beijing), and the German colony of Tsingtau. In late October he left for Japan via Shanghai and then, in early November, he moved across to America and Canada where he spent a month visiting universities and setting up committees in support of the UUS. But by the time he arrived back in Oxford just before Christmas 1910, his eyes had been opened to complex problems of which, on his own admission, he had not been sufficiently aware before his travels, and these provoked a substantial essay entitled ‘The New China and the New Education’. This appeared in The East and the West in January 1912, i.e. just after the end of the Qing (Ch’ing) Dynasty (1644–29 December 1911) and during the short but turbulent period (January 1912–September 1913) of the new Republic of China spearheaded by the modernizing Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925).

In January 1911, Johnston moved into a room in the Garden Quad of New College, where his duties involved a lecture course for the Honours School in Divinity, tutorials in Theology, teaching the Pass School Divinity students, and doing a small amount of teaching for Greats. He proved to be a popular tutor, whom students could approach about their “perplexities and troubles and temptations”. But as he acquired more experience as a university teacher, the single-minded idealism of his two first publications was gradually replaced by more complicated attitudes that would pull him in several directions for the rest of his civilian life and, probably, finally put him off the idea of ordination. So when, on Christmas Day 1912, he happened to go into the little Roman Catholic church in Cowley and found “a miscellaneous small crowd of all ages and classes and smells kneeling around the crèche”, he later contrasted it, with unmistakable nostalgia, with “the typical Anglican performance of carols at Magdalen” that he had just attended. Yet although he found himself being drawn towards the earthy Volkstümlichkeit of popular Catholicism, he also realized that as a budding theologian, he needed to get to grips with the Modernist critique of the Bible and orthodox dogma, a highly controversial example of which was constituted by the Revd James M. Thompson’s Miracles in the New Testament (1911). Thompson (1878–1956; Fellow of Magdalen 1904–56) was Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity when he wrote this book, and his ultra-Modernist, ultra-rationalist views on the subject of Christ’s miracles caused the Bishop of Winchester to deprive him of his licence to hold a cure of souls and nearly cost him his Fellowship (see David William Llewellyn Jones and C.I.S. Hood). Nevertheless, Bevan tells us that any tensions in Johnston’s theological thinking were ultimately reconciled by his “firm belief that the great Reality behind the universe” could be “apprehended with different degrees of truth and clearness” in all the different forms of religion, a conviction that caused him to become increasingly interested in comparative religion.

At the same time, Johnston was also gaining a reputation in the SCM as a “coming man”; and in April 1911, the Revd Tissington Tatlow (1876–1957), a brilliant and dynamic organizer who had been the first travelling Secretary of the Student Volunteer Missionary Union in 1897, the Secretary of the British Colleges Christian Union in 1898, and the first General Secretary of the SCM (1903–29), of which he has been described as the “vital centre” and “spiritual leader”, got him elected as a member of the SCM’s Executive. As such, Johnston was proposed almost immediately as a possible representative at the SCM Summer Conference in Holland from 10 to 15 July 1911 – though in the end he refused the offer and from 4 to 7 July participated instead in a small SCM conference on the “problem of truth” at Swanwick, near Fareham, Hampshire. Moreover, like his friend Edward Vivian Birchall, who had become the Secretary of the socially concerned Agenda Club in mid-1911, Johnston developed a social consciousness by becoming actively involved in Oxford’s Cavendish Club, which aimed to persuade young men from privileged backgrounds to undertake voluntary social work.

In June 1911 Johnston attended camp with the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps and oversaw a three-week-long reading party for undergraduates in Marburg; on 30 June he took his MA alongside T.E.G. Norton; and in October 1911 he was proposed for membership of the SCM’s Standing Committee on Apologetics – a theological term which means “the defence of the Christian theology against modern objections using historical, evidential and reasoned bases”. But by April 1912, the relevant sub-committee had been unable to find the time to convene and it remained silent until December 1912, when it submitted a report to the SCM’s Executive Committee recommending the publication of a series of seven pamphlets: “On Comparative Religion, or on The Finality of Christianity” (which sounds like Johnston’s suggestion); “On the Bible”; “On Natural Law and Christianity”; “On the Validity of Experience”; “On Christian Ethics”; “On Theosophy” and “On the ‘Attitude to the Universe’”. But although the Executive Committee agreed to the proposal, nothing more was heard from the sub-committee until Christmas 1913, when it informed the Executive Committee that it had tried to meet in early November but had been unable to do so and so had not yet made any progress with the project. Consequently, the old sub-committee was disbanded and a new one formed, but without Johnston as one of its members, probably because he had too much to do in Oxford.

Then, at the very large Quadrennial Conference of the Student Volunteer Missionary Union that took place in Liverpool between 2 and 8 January 1912, Johnston delivered a powerful lecture entitled ‘The Call of Christ to Study’, which was published later in the year as part of the conference proceedings. While the lecture develops the argument of ‘A Student’s Religion’, it is more daring and explicitly Christocentric. Beginning from the assertion that “to the Christian[,] nothing that is concerned with truth can be insignificant, since his Master claims that He is the Truth”, Johnston argued that “if we could see Christ as He is[,] we should all find all the subjects of our study as true avenues of approach to Him, we should see in Him, consummated and radiant, all the truth of which we catch fragments and gleams in our partial study”. Consequently, he concluded, science and faith were not opposed to one another “for the attitude of science and that of faith is one and the same – sitting at the feet of the Truth, simply and humbly waiting upon the revelation of reality”. With this in mind Johnston told his student audience that it is:

God’s discipline to teach us the true spirit of work – steady plodding where we see nothing but the next thing to do, in sure trust and confidence that we shall be guided wherever we are working […] with singleness of heart. No dashing to and fro, no planning and executing, however good, no attendance at meetings or conferences, no enthusiasm and excitement, can ever, as a preparation for life, make up for the conscientious thrusting on, often alone and unencouraged, through what seems wastes of learning – it is not only the mind, but the whole of our spiritual being that is braced and stiffened in every fibre by such effort.

Admirable though these sentiments may be, one wonders how a contemporary student of – say – golf studies would react to the first four propositions and what a contemporary Dean who was looking to increase his School’s Research Assessment Exercise score would make of the fifth one.

Because of the shared concern with mission, the liberal SCM was still able to work fairly harmoniously with the more fundamentalist and intensely evangelical Intercollegiate Christian Union (ICU). But in February 1912, not long after the Liverpool conference, the SCM’s Executive Committee received a resolution from the London ICU which complained, politely but firmly, that:

recent conferences of the Student Movement have shown a lamentable lack of definite aggressive spiritual teaching as applied to the life of the individual, and have been too academic and theological in character. They have consequently failed to exercise a permanent influence on the religious life of a larger number of those present, – in a word, men are not converted. We should like to see the Programme of the Conferences dealing most particularly with such subjects as the necessity of conversion and the practical means of development and maintenance of the spiritual life, and the imperative necessity of putting such means into practice.

The authors of the above letter almost certainly included Johnston’s lecture in their critique and it would be interesting to know how he responded to it, given his broadening view of theology, developing interest in comparative religion, and growing reservations about the value of conventional missionary methods.

Certainly, Johnston’s substantial and thoughtful essay on ‘The New China and the New Education’ evinced an unease about “fiercely evangelistic” institutions, and although it appeared in print in January 1912, it must have derived to a considerable extent from his experiences in China in the run-up to Sun Yat-sen’s bloodless revolution of 1911. In it, Johnston was clearly trying to work out how Christian beliefs and institutions could usefully function within a culture whose values, forms of thought and educational practices were so different from those of the West, and he concluded that the best way forward for Christianity in China was largely one of “gradual habituation to Christian ideas and practice, rather than anything that would lead to a more personal faith”. But such liberal gradualism would not have been acceptable to the ICU, whose central doctrines, as evidenced by the letter cited above, were substitutional atonement for human sinfulness via Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, assent to that doctrine via personal conversion, and belief in the literal truth of the Bible. The divergence between the liberal and evangelical wings of the SCM increased over time and in 1928 the evangelical wing finally split away to become the Intervarsity Fellowship of Evangelical Unions.

In April 1912, the Executive Committee of the SCM proposed Johnston as the third of three editors of a “Collection of Prayers for Students” and in September 1912 it was considering Johnston as the SCM’s representative at the World Student Christian Federation at Lake Mohonk, in Ulster County, New York State. But the money could not be found and Johnston stayed in England, where he was extremely busy because of his Oxford commitments, one of the most time-consuming of which was his involvement in the local religion of oarsmanship. Indeed, during the Summer Term of 1912, much of his time must have been taken up either with the coaching of the New College and Magdalen VIIIs, long-standing rivals on the river, or with writing and reviewing. Then, shortly after the end of that term, the Governing Body of New College offered him a Fellowship beginning in October – which he declined, partly because he was not sure that he wanted to stay in Oxford and partly because he suspected that Magdalen, to which he felt a greater loyalty, would make him a similar offer. Moreover, by July 1912, he was re-reading von Hügel’s The Mystical Element in Religion, a work that would, according to Johnston’s biographer, have the greatest influence on him during the next three years of his life – his last. And on 20 December 1912 his name appeared on the list of all those members of| departmental committees and officers of the SCM who had attended an all-day meeting “to consider changes in the [SCM’s] basis and constitution as proposed by the Second Commission”.

During the academic year 1912/13, Johnston gave his first lecture series at New College. Entitled ‘Christ and Christian Devotion: A Comparative Study of Religions’, the three lectures grappled with the problem of what, if anything, entitled Christianity to claim pre-eminence over other religions that involve a divine incarnation. On 16 April 1913 Johnston gave an address to the annual conference of the Jewish Christian Muslim Association which took place in the London headquarters of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. In October 1913 a version of that address appeared in The East and the West as ‘Supply of Missionaries – The Apostolic Way’ and indicates that Johnston was still concerned with the problems of modern evangelism, for he used his familiarity with St Paul’s life and work to show how evangelists spread the Gospel when the Christian Church was in its infancy. Although the text began with the assertion that in those days “the whole Church was intensely ‘missionary-hearted’”, it concluded that the “main method by which ‘the way’ became known and entered” was the impression made by “the witness of the ordinary believer in the course of his or her work-a-day life”.

Meanwhile, Johnston continued to train the VIIIs of his two colleges, and in Eights Week of 1913 he had the satisfaction of seeing Magdalen’s first VIII stay Head of the River and its second VIII finish fifth after bumping six VIIIs, including New College’s first VIII. But at about the same time, the United Universities Scheme, in which he had invested so much time and effort, finally collapsed for lack of money. However, just before the end of the calendar year, the SCM’s Theological College Department Executive strongly urged that Messrs Johnston and Spencer should be selected from the members of the already extant sub-committee and proceed with the proposed book of prayers so that it could appear in time for the SCM’s Summer Conference of 1913. The Executive also proposed that the book should be divided into two sections, with Part I consisting more of daily prayers and Part II consisting more of a “definite collection of Prayers”. In April 1913, the Executive added to its advice by giving Spencer and Johnston five further guidelines, and although they did not have a draft ready by the summer, in September 1913 they were able to report that they had collected enough material to produce such a publication. So the Executive decided to appoint readers for a draft version who would do their work over the next two to three months, and submit their reports at Christmas 1913. Then at Easter 1914, Tissington Tatlow seems to have lost patience with the progress of the project and reported to the Executive Committee that “as it now stood, [the Book of Prayer] did not answer the purposes for which it was originally intended [and] was now primarily a book for private devotion and less for use at retreats, Christian Union meetings, etc., etc. [but] could be easily revised”. So taking the hint, the Committee “decided to leave the revision and completion of the book to Mr Tatlow, Mr Hunter and Mr. Martin” – and, by implication, drop Spencer and Johnston as its editors. However, in September 1913 the Executive Committee of the SCM appointed Johnston as a member of its new Sub-Committee on Schoolboys Camps, and at Christmas 1913, after two short meetings, the sub-committee sent in a long report approving of such camps, regarding them as offering good chances for evangelization.

During 1913, Johnston also spent a considerable amount of time turning his first lecture series into a book. The series consisted in three groups of lectures: (1) ‘The Soul: Some Points in the Psychology of Religion’, (2) ‘Christ’s Consciousness of Himself’, and (3) ‘Christianity and the Other Religions of an Incarnation’, all of which were very obviously the result of intensive study and marked by considerable intellectual confidence, qualities that were already evident in his very knowledgeable review of Dr Hermann Roemer’s (1816–94) book on the Bābī-Behā’ī movement (1911) that had appeared in the July 1912 issue of the International Review of Missions. His book, Some Alternatives to Jesus Christ: A Comparative Study of Faiths in Divine Incarnation appeared early in 1914 as the third volume in The Layman’s Library (edited by F.C. Burkitt, the Norrisian Professor at Cambridge, and the Revd G.E. Newsom, Professor of Pastoral Theology at King’s College, London, and published by Longmans & Co.).

Meanwhile, at the start of the academic year 1913/14 Johnston had returned to Magdalen as a full Fellow and Dean of Studies, with a set of rooms in the New Building that overlooked the Deer Park. So he was able to devote even more time to training Magdalen’s rowers, and in Michaelmas Term 1913 he helped President Warren to coach the trial VIII for the Boat Race of spring 1914. By now, Johnston had such a good reputation among the undergraduate community that on 15 November the student newspaper The Isis selected him as its “Isis Idol” of the week. This meant that he featured there as the subject of one of a long-running series of pen portraits of people at Oxford, mainly undergraduates, who were considered by their peers to be leading lights of the university – most of whom, let it be said, later sank without trace. Although parts of the encomium were ironic to the point of flippancy – “His dealings with the fair sex are limited to the one time possession of a bicycle named Phyllis” – it concluded: “His deep convictions and conscientiousness make him above all others a really ‘sound’ man; and his understanding and sympathy make him an invaluable friend, a fact taken advantage of by many.”

In January 1914 Johnston published two lengthy, tightly argued and very knowledgeable review essays in journals that were more academic and more prestigious than those in which he had published so far, and they give us a clear idea of the direction in which he would have gone had the war not intervened. Both concern mysticism and the first, which appeared in The Journal of Theological Studies, dealt solely with The Mystic Way (1913), by the Anglo-Catholic Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941). The second appeared in the Quarterly Review and discussed seven publications (1912/13) – four examples of “modern mysticism” and three books on mysticism, of which one – Underhill’s The Spiral Way (1912) – had been published under the pseudonym of John Cordelier. Like Johnston’s own work, The Mystic Way was heavily indebted to von Hügel, and although Johnston was fulsome in his praise of the book’s strengths, especially those of its last two parts and its focus on a side of Christianity “which has until recently been largely ignored”, he identified five weaknesses in its argument that illuminate his own theological position. First, Underhill’s book tended towards reductionism as it viewed mysticism as “the true essence of all real religion”, and “progressive union with God” as “the characteristic feature of true mysticism”. Second, it overlooked the fact that the historical roots of Christianity lay in a prophetic, not a mystical forebear – i.e. the Judaism of the Old Testament. Third, it erred by applying mystical categories to the life of Jesus, thus presenting him as a “sort of Prometheus” rather than as a sacrificial redeemer. Fourth, it was beset by a dualism, regarding “matter as ‘clogging’, in the familiar neo[-]platonic way”. And fifth, it downplayed the practical and ethical sides of Christianity and the place of sin in the overall scheme of things. Consequently, Johnston concluded, it makes Christianity “a less rich and varied thing than it actually is”. For Johnston,

what we find in the New Testament is not the lonely flowering of a perfected mysticism in this, the ordinary, sense of the word, but the fusion at white heat of both these supreme types of the religious consciousness [the Prophetic and the Mystical] in their most powerful and balanced form, each supplementing and correcting the flaws of the other till they combine to present the perfect relation of man to God.

Or in other words, Johnston criticizes Underhill’s book for not doing what his own book aimed to do: to bring into relief the uniqueness of Christ and the precedence of Christianity over other world religions, for it concluded:

I feel that the superiority of the Christian consciousness in religion is like the supremacy of the Greek genius in art; that it is the sudden bloom of a gradual growth; that in it is found complete what is elsewhere at the best fragmentary; that the scattered beauties outside it are here united in one organic whole; that there is nothing really comparable to it before or since; and that it is possible to trace it as a powerful factor in the creation of all that is most like it […] Half-way between the East and the West, half-way between the dawn of history and to-day, there comes to the Christian a figure Who, in all the richness and beauty of a perfect humanity, yet claims to be the Son of God, the fulfilment of all hopes, still with us, loving and powerful, for ever.

Johnston’s second review essay overlaps with the first as it, too, is centrally concerned with “a tangled problem – what is meant by mysticism”, given that “the term has been used as the worst abuse or the highest praise according to the taste of the writers; and the description they give of it has varied in sympathy with their views”. But to a greater extent than in the preceding review essay, Johnston wants to know why this “mystical revival”, which would, in the not so distant past, have seemed like “an obscurantist reaction”, “has almost completely swept away the narrow limits of toleration imposed by that older rationalism”. One explanation, Johnston argues, is the “passing of Victorian optimism, and even of the ‘Edwardian’ compromise with pessimism” which “has turned the thoughts of all who have time to think towards the great question of the value of life which is bound up with the nature of consciousness and its relation to the universe”, for it is here that “the mystic appears to have something important to say and is now listened to with avidity”. Within this quintessentially Modernist context, Johnston discusses the poetic works of Francis Thompson (1859–1907), the Bengali polymath and first non-European winner of the Nobel Prize for literature Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), and Michael Fairless (the pseudonym of Margaret Fairless Barber: 1869–1900) in order “to arrive at some understanding of modern mysticism”. His conclusion is that all three poets are low-grade mystics – like, it must be said, so many other modern mystics. Using the classic stages of the Mystic Way, Johnston states that Thompson “never emerged fully into the light of the ‘Illuminative Way’, still less reached the ‘Unitive’ state”. Similarly, he argues that Tagore’s poetry has “no coherent body of theology or religious practice behind it”, and lacks both “the same deep need to work out his religion in social life” and a “clearly apprehensible idea of [God] and the way to faith in Him”. Finally, although Barber’s poetry “is transfused with a warm glow of mystical religion”, Johnston considered that this state of blessedness had been easily attained, without the writer having been beset by any of the dark tribulations that tended to afflict the pre-modern mystic. Johnston also argued that because his three subjects tend towards pantheism, they play down the reality of evil and are more or less blind to the struggle with evil in which God is eternally engaged. Consequently, he concluded, the flaws in the mystical writings of his three subjects were symptomatic of the age:

So it would seem that this double truth of the essential antagonism between the righteousness of a loving God, and the rebellion of a humanity which is potentially good or bad, is one that most needs to be recovered in our time – and that without the loss of the large-hearted sympathy and patience towards others, which has been one of the best characteristics of modern religious development.

It was precisely Johnson’s desire to be actively involved in the transcendental struggle between good and evil that moved him to enlist a few months later.

Finally, in May 1914, just before the outbreak of war, Johnston published an article in The Challenge in which he discussed the idea of “miracle” in the light of the book Christentum und moderne Weltanschauung (1911–14), by the German Lutheran theologian Professor Carl Stange (1870–1959), and in the context of the controversy that had been sparked by his Magdalen colleague J.M. Thompson’s Miracles in the New Testament (1911) (see above). Moreover, for several years Johnston had felt a particular affinity with manual workers – partly, according to his biographer, because of his ascetic side, partly because of Christ the Carpenter’s hold over his imagination, partly because of his natural friendliness, and partly because of his “feeling that the life of the manual worker, concerned with the broadly human, the more primitive, pleasures, pains and strivings, had something more real about it than the life of the middle class”. Indeed, two of his most negative categories were “literary”, which he equated with second-hand, and “North Oxford”, which was for him the symbol of bloodless, respectable, middle-class, “literary” culture. In summer 1914, these beliefs led him to rent a working man’s house near the Magdalen Mission in Oakley Square, London NW, just to the west of Regent’s Park, with a view to working as a coalman in London during the vacations so that he could join a Trade Union. He also took some London boys who were associated with the Magdalen Mission on a camping holiday near Christchurch, Dorset, and participated in various religious conferences, including the SCM Conference at Swanwick. He was staying with Bevan and his family at Rempstone, four miles north-east of Loughborough, Leicestershire, when, in late July, the imminence of war became inescapable.

Military and war service

Johnston does not seem to have done any military service during his undergraduate years at Magdalen (1904–08), but he became a Private in the Oxford University Rifle Volunteer Corps from 20 May to 31 September 1908, took his Certificate ‘A’ in December 1908, and was a Corporal in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps (OUOTC) from 21 May to 7 June 1910 (when he resigned, presumably because of his journey to China). But he was back with the OUOTC as a Sergeant by 18 March 1911, as this was the day when he was promoted Acting Second Lieutenant on the Unattached List (Territorial Force: Officers’ Training Corps) (London Gazette, no. 28,476, 17 March 1911, p. 2,238), and from 23 March to 24 April 1911 he may have been a member of the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Irish Guards. On 10 January 1913 he was promoted Lieutenant and from 23 March to 4 April 1914 he was in the Volunteer Battalion of the Grenadier Guards. But when war was declared he returned to Oxford, where, on 15 August, he was made a Second Lieutenant on probation so that he could, on 26 August 1914, find a niche as an officer in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (LG, no. 28,876, 21 August 1914, p. 6,598; no. 29,172, 25 May 1915, p. 5,081).

Initially, his job was to train 200 recruits, mainly in the Portsmouth area, where the 3rd Battalion would spend most of the war. But as Johnston wanted more active military service, on 2 October 1914 he published a piece in The Challenge (reprinted in Bevan, 1921, pp. 192–9), setting out the principles that had induced him to take up arms. Essentially, the essay says that Johnston saw the coming conflict as “transcendental strife”, “a great struggle between God and the powers of evil”, a war against “some malign spirit of triumphant evil” in which England, holding on to “a Christian sense of justice, mercy, and truth”, has been given “the courage to stake our lives in a quarrel which is not ours nor our allies’ alone, but God’s”. It concluded:

All we need is, with perfect love and forgiveness in our hearts, to do all in our power by fair fighting to render the evil genius of modern Prussia innocuous for the future. In so doing we use God’s power in the service of His righteousness and in the spirit of His love. So shall we be fellow-workers in God’s purpose for the coming of His kingdom, when, evil being done away, war, too, shall cease, and yet the triumph of the Lord be secured.

The wording is highly significant for it suggests that Johnston’s distinction of 1909 between the simple peasant Volk and the new machine culture that had been imposed on them, has become a sharp distinction between Catholic South Germany and Protestant North Germany. Consequently, in a letter to Bevan sent from Portsmouth dated 17 September, Johnston wrote:

It seems significant that no great work, as far as I know, poetical, artistic, or musical, has been done in North Germany, and that since Prussian domination no great work at all has come out of the German Empire – with the significant exception of Nietzsche.

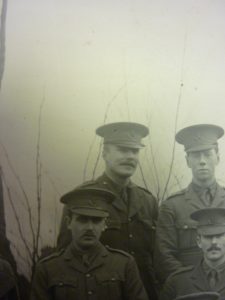

Shortly after the article appeared, Johnston sent a copy to a friend, commenting in his accompanying letter: “I’m happier [training recruits] than I’ve been for years, as things have become more simple than I ever expected they could be on this earth.” Moreover, in a letter to his mother of 22 January 1915, Johnston would name ‘For the Fallen’, by Laurence Binyon (1869–1943) (first published in The Times on 21 September 1914), and ‘Sacramentum Supremum’, by Henry Newbolt (1862–1938) (inspired by a Japanese officer’s account of the Battle of Mukden of 1905 during the Russo-Japanese War), as his favourite poems. And in the same period, Johnston’s slightly younger Cambridge contemporary, Rupert Brooke (1887–1915; off the island of Skyros, Greece, where he is buried), would translate the same sentiments into the even more rapturous verse of his five widely read sonnets entitled 1914. For both young men, military service during the first six months of the war offered a means of simplifying their lives in a world that was becoming increasingly complex, and there is no doubt that in the above photo Johnston looks less gaunt and more relaxed than ever he did in the rather grim photos that were taken of him while he was a young academic.

By mid-November 1914, Johnston was one of seven Magdalen Fellows who had become, or were about to become, commissioned officers in the armed forces. After spending Christmas 1914 with his family in Lincoln, he received his marching orders on 30 January and landed in Le Havre on 2 February 1915, where he was confirmed in the rank of Second Lieutenant on 10 February (London Gazette, no. 29,063, 9 February 1915, p. 1,333). But in early February, he wrote a long letter to his mother which indicates that his military experience was causing his ideas about the war, generated in the hot-house world of an Oxford college and a middle-class clerical family, to modify. While he claimed that his feelings about the war were still what they were in the previous July, censoring his men’s post had begun to make him relativize his own position:

The men’s letters home, however, have done me an awful lot of good, teaching one [NB (RWS)] to see what the war is costing and creating – much more of both with them than with me, I fear. There’s the most touching simplicity in their determination to “do their bit” clashing with an intense, though almost inarticulate, longing for home. […] One doesn’t hear much about the cause, and nothing of passionate love or hate, but only a sort of dog-like fixity of intention to get through with the job. The home-life revealed is what means quite everything to them, though in many cases it’s clearly not what we should understand by the term.

Johnston also began to realize that the war was hitting France harder than Britain – which caused him to add:

But when one thinks of the fellows we’ve lost – John Perssé [see Rodolph Algernon Perssé], [Robert] Wilfrid [Raleigh] Gramshaw [(1890–1915) a graduate of Exeter College, Oxford; died on 27 January 1915 of wounds received in action at Cuinchy on 25 January 1915 while serving as a Second Lieutenant in the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Royal Sussex Regiment], Alistair Menzies [see Alastair Graham Menzies] in the last lists – I’m glad to feel we’re paying the price too. It’ll be cheap if we can buy back our own and the nation’s soul from selfish ends and cowardice.

Johnston stayed in No. 2 Infantry Base Depôt at Le Havre until about 19 February, and on 21 February 1915, he and 30 ORs (other ranks) joined the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, at the hamlet of Les Choquaux, near the village of Locon (see G.M.R. Turbutt) to the north of Béthune, as reinforcements for ‘D’ Company. The 2nd Battalion, part of the 5th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division, had been in action in France since 14 August 1914, and lost heavily during the “race to the sea” and the fighting around Ypres (see Turbutt), and when Johnston joined it was in Divisional Reserve until 4 March, when it moved to the trenches at Cuinchy, 100–200 yards from the enemy positions.

This group photograph of officers of the 52nd Light Infantry (2nd Battalion, the Ox. & Bucks Light Infantry) was taken at Les Choquaux on 23 February 1915 Johnston is on the extreme left in the back row.

(Courtesy of Major Bob Sheldon, the Curator of the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum)

Detail showing Johnston from the group photo immediately above

(Courtesy of Major Bob Sheldon, the Curator of the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum)

Johnston’s Battalion was in and out of the same trenches or resting at Beuvry until 27 March. But on 28 March it pulled back to Gorre, where it stayed until 4 April, Easter Day; and from 5 to 13 April it was back in the trenches, this time near Festubert. On 6 April, his platoon suffered its first casualties – one OR wounded and one killed – and on c.7/8 April Johnston wrote a rather disturbed and disturbing letter to someone called Christina which he felt the need to explain to his mother on c.11 April:

As I explained [in the previous letter to his mother] I had come in early that morning from a rather successful piece of military murder, and the contrast of it with the happy Rempstone atmosphere and the blessedly innocent talk about war made me feel very blood-stained and unworthy to be in touch. It seemed as if I was bound to make clear the hard, unromantic reality, in order not to be under false pretences in continuing to hear from and write to her. It was not merely that I had caused death and injury to other men, but that in my heart of hearts I felt a certain triumph and satisfaction in having done so. […] And to that is added a certain sporting interest in beating the enemy at his own game which he’s forced us to play.

From 23 March to 22 April the Battalion rested behind the front, and on 13 April – not 11 April as dated in Bevan’s biography – Johnston mentioned in a letter to his mother that a second son of C.R.L. Fletcher (1857–1934, Demy of Magdalen 1876–1880, Fellow of Magdalen 1889–1906) had been killed in action (see E.H.L. Southwell and C.I.S. Hood):

George [Fletcher], a master at Eton – wrote me a wonderful letter of courage and hope about them both. I think the Army that is being enlisted beyond will be the finest stuff of that which joined here, before it’s all over.

Both Johnston and George Fletcher are referring to Second Lieutenant Walter George Fletcher who was killed in action on 20 March 1915 near Armentières, aged 27, while serving in the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. On 17 April Johnston cycled north through Armentières to see his younger brother and E.V.D. Birchall, both of whom were serving in the Bucks Battalion which was at that time in support of the London Rifle Brigade. He met up with them for lunch in Ploegsteert Wood, since he mentions that G.H. Morrison had been killed there, then cycled up to Ypres to see “Cherry” (Francis Newbolt) – who would be wounded during the 2nd Battle of Ypres a few weeks later – and managed to arrive back near Festubert by 21.00 hours! On 23/24 April Johnston’s Battalion was back in the trenches near Festubert but then rested in Béthune from 24 April to 8 May. On 2 May 1915 Johnston’s dramatic change in attitude to the war became evident when he wrote in a letter: “I shall be anti-military to my dying day – it’s quite extraordinary how even the soldier’s good qualities are spoilt by the environment.”

On Sunday 9 May Johnston survived the Battle of Aubers Ridge, to the south of Neuve Chapelle, because his Battalion was in Divisional Reserve at Le Touret, a mile or so to the west, and so, as he later wrote to Bevan: “we were of the battle, but not in it”. But at 20.00 hours on that day the 2nd Battalion set off to march through Le Touret and La Couture in order to reach Richebourg St Vaast as part of the attempt to relieve the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Division. But then, a mere five hours later, at 01.00 hours on Monday 10 May, Johnston’s Battalion received orders to relieve the 1st Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment which was in breastworks south of the Rue du Bois, near Richebourg l’Avoué. As there were only two hours left before dawn, the relief had to be done with great dispatch, partly through narrow communication trenches where unburied dead bodies made progress difficult. But the move went off without mishap and on 10 May the Battalion found itself organizing the front line near Richebourg l’Avoué, two miles north-east of Festubert. Working while a good deal of shelling was going on, two companies were detailed to repair the front-line breastworks and two to improve other trenches to the north and south of the road. On that day Johnston wrote to Bevan:

I really think [the Germans] have no sense of proportion – another form of humour. I mean, just as most […] depends on seeing contrasts, so all the German ethos is a gigantic megalomania – for which there can be no relativity – and it’s difficult to think of them at all as anything except machine-guns, and it’s hard to love such. Perhaps some day we may appreciate each other, but, as you know, long before this I could not stomach even German theology.

According to the diary of Captain Guy Blewitt (1894–1969; later Major, DSO, MC: see Turbutt), who managed against all the odds to survive the war, Johnston’s ‘D’ Company moved from the cover of the support breastworks and into the firing line at 20.00 hours on the evening of 10 May and spent the following day preparing for the coming attack. But during the night of 11/12 May 1915, Johnston went out into no-man’s-land with two stretcher-bearers, Privates Hickman and Angel, to recover men who had been wounded during Sunday’s battle and whom he had noticed during the course of the day. But they accidentally came within 60 yards of the German trenches and were challenged by a sentry, and while they were trying to crawl away, a flare went up and the Germans opened fire, wounding Private Angel in the side and Johnston in the stomach. On Johnston’s orders, he and Angel were left where they were while Hickman returned to the British lines to get help. But the firing continued, and after waiting for an hour until it had died down, Captain Blewitt allowed Hickman to take a search party to look for the two wounded men. They found Angel, who had managed to crawl some distance, and after bringing him in, they returned to look for Johnston until dawn, but to no avail. Further search parties on the following nights were equally unsuccessful and it was at first thought that Johnston had been captured. But a Private who had taken part in the searches reported that their adversaries had been the Prussian Guards, who had been killing their prisoners that day. So if Johnston did not die of his wounds, he may have been murdered, aged 29. On 17 August 1915, somewhat belatedly, he was promoted Lieutenant.

The main part of the Battle of Festubert finally took place after Johnston’s death, between 15 and 18 May. The Germans suffered very heavy losses and were pushed back 600 yards, and the British took 785 prisoners and captured ten machine-guns. But the battle was particularly significant because it demonstrated the British Army’s relative lack of high-explosive shells – which caused a public outcry and led to a change of government.

Johnston’s parents never really came to terms with their son’s death, and for at least three years they hoped against hope that he had been captured and/or lost his memory. On 27 June 1916, C.C.J. Webb noted in his diary that the President had shown him a “letter of Canon Johnston’s, showing that he still hopes for news of Leslie and refuses to regard him as probably dead”; and it was not until May 1918 that his family informed the War Office that it “desired that action consequent on official acceptance of death” should now be taken. On 20 July 1918 Webb noted that Johnston’s rooms in College had still not been touched and on 1 October 1918 that Bevan had sent him “a list of J. L. J’s books (wh[ich] were, it seems, left to him) to choose one or two from for myself & to pass it on to special friends of his among his brother fellows”. Nevertheless, no obituary in the normal sense ever appeared, and the obituary for Johnston’s father of 1923 says, tellingly, that he “leaves a widow, with two sons and a daughter”. Johnston has no know grave but is commemorated on Panel 26 of Le Touret Memorial (Le Touret Military Cemetery).

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special Acknowledgements:

**Edwyn Robert Bevan, A Memoir of Leslie Johnston (London: SCM, 1921); Bevan began work on this book by 29 June 1919, and the brief biography published here is greatly indebted to Bevan’s work.

Printed sources:

Tuchars, ‘Isis Idol no. 493: John Leslie Johnston (Magdalen College)’, The Isis, no. 517 (15 November 1913), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘A New Magdalen “Eight”’, The Times, no. 40,695 (13 November 1914), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘General Notes’, The Student Movement, 17, no. 9 (June 1915), p. 183 [brief report that Johnston is missing in action].

Mockler-Ferryman, i [24] (4 August 1914–31 July 1915) (n.d.), pp. 225–47 and 404–5.

[Anon.], ‘Student Movement News from Far and Near’, The Student Movement, 18, no. 1 (October 1915), p. 17 [brief report that Johnston is still missing in action].

[Anon.], ‘Death of Canon Johnston’, The Times, no. 43,492 (7 November 1923), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘Rev. H.L. Johnston: Start of BBC’s daily service’, The Times, no. 57,156 (23 January 1969), p. 10.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 155, 334.

Tim Card, Eton Renewed: A History from 1860 to the Present Day (London: John Murray, 1994), p. 134.

Richard Sheppard, The Gunstones of St Clements: The History of a Dynasty of College Servants at Magdalen, Magdalen College Occasional Paper 6 (Oxford: Magdalen College, 2003), pp. 64–9.

Harris (2004), pp. 62–86.

Hugh Martin, ‘Tatlow, Tissington (1876–1957)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 53 (2004), pp. 825–6.

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 83 and 106–8.

Richard Sheppard, David Roberts and Robin Darwall-Smith, Gladwyn Maurice Revell Turbutt, 1883–1914: A Biography (privately printed at Alfreton, Derbyshire, by The Higham Press, 2017), esp. pp. 126–64.

Archival sources:

The Cadbury Library, Birmingham University (Special Collections), the Archives of the Student Christian Movement, Box 31 (Executive Committee Minutes, vol. 6, [1910–1914]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: 04/A1/1 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1888–1907]), pp. 398, 438, 448, 459, 462.

MCA: 04/A1/2 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1907–26]), unpag.

OUA: OT 4/2.

OUA: UR 2/1/54.

OUA(DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161; MS. Eng. misc. e. 1163.

WO95/1348.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Edwyn Bevan’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwyn_Bevan (accessed 28 December 2020).

John Richardson, ‘Familiar Frailties’ [essay on-line concerning rifts in the SCM], Trushare Files No. 111, New Directions Archive: http://trushare.com/0111AUG04/TR111COVE.htm (accessed 28 December 2020).

Books by John Leslie Johnston:

Some Alternatives to Jesus Christ: A Comparative Study of Faiths in Divine Incarnation (The Layman’s Library, No. 3, edited by F.C. Burkitt [The Norrisian Professor at Cambridge] and the Revd G.E. Newsom [Professor of Pastoral Theology at King’s College, London] (London: Longmans & Co., 1914). Completed Christmas 1913, based on lectures given in the Theological Faculty, Oxford). Page vii contains special thanks to C.C.J. Webb. Although copies of this book are now scarce, it is available on-line.

Articles by John Leslie Johnston:

‘A Student’s Religion’, The Student Movement, 12, no. 5 (February 1910), pp. 110–12.

‘Modern Missionary Methods – a Question’, The East and the West: A quarterly Review for the study of Missionary problems, 8, no. 32 (October 1910), pp. 412–21.

‘The Salt of the Earth’, The Student Movement, 13 (November 1910), pagination unknown. [This article is missing from the one run of the periodical that is known to exist in a public library, either in Britain or abroad].

‘The New China and the New Education’, The East and the West: A quarterly Review for the study of Missionary problems, 10, no. 37 (January 1912), pp. 27–39.

‘The Call of Christ to Study’, in Tissington Tatlow (ed.) Christ and Human Need: Being addresses delivered at a conference on Foreign Missions and Social Problems. Liverpool, January 2nd to 8th, 1912 (London: SVMU, 1912), pp. 130–7.

[Anon.]. ‘The Bābī-Bahā’i Movement’ [review of Hermann Roemer, Die Bābi Behā’ī: Eine Studie zur Religionsgeschichte des Islams (Potsdam: Tempel-Verlag, 1911)], International Review of Missions, 1, no. 3 (July 1912), pp. 546–51.

‘Supply of Missionaries – the Apostolic Way’, The East and the West: A quarterly Review for the study of Missionary problems, 11, no. 44 (October 1913), pp.439–47.

‘Mysticism in the New Testament’ [review of Evelyn Underhill, The Mystic Way] The Journal of Theological Studies, 15, no. 58 (January 1914), pp. 244–54.

‘Modern Mysticism: Some Prophets and Poets’, The Quarterly Review, 220, no. 438 (January 1914), pp. 220–46.

‘The Meaning of Miracle’, The Challenge, 1, no. 4 (22 May 1914), p. 108.

[Published anonymously], ‘The Christian Warrior’, The Challenge, 1, no. 23 (2 October 1914), p. 612.

‘The Suffering Servant in Saint Mark’, The Interpreter (April 1916), pagination unknown. [This periodical could not be located in any British library].