Fact file:

Matriculated: 1908

Born: 16 September 1889

Died: 15 July 1916

Regiment: Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)

Grave/Memorial: La Corbie Communal Cemetery (Extension): 1.D.26

Family background

b. 16 September 1889 at 1, Balgillo Crescent, Broughty Ferry, Dundee, Scotland, as the eldest son (of four children) of George Alexander Gilroy (1851–1921) and Anne Brydon Gilroy (née Wilson) (1867–1951) (m. 1888 in Cheshire). The 1891 Census records the family as living at 1, Balgillo Crescent and having three servants.

Parents and antecedents

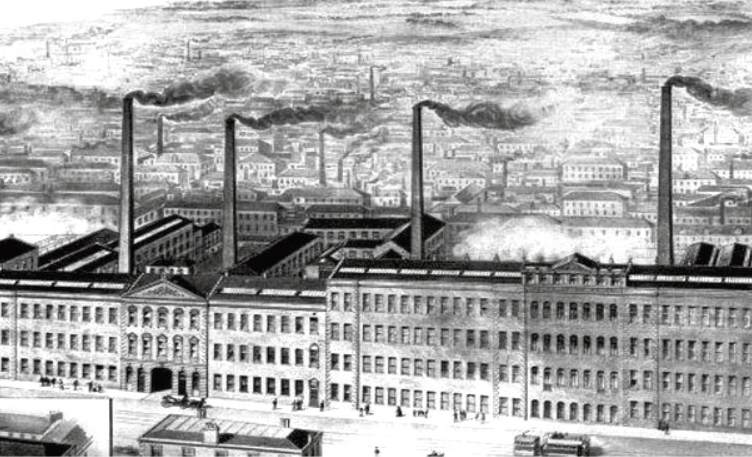

George Alexander, i.e. Gilroy’s father, was the third son of the linen merchant George Gilroy (1815–92; m. 1846) and the grandson of Alexander Gilroy (c.1782–1832), a carpenter and linen-manufacturer in the small market town of Dundee (population 16,000 at the end of the eighteenth century). Flax-spinning mills first appeared in Dundee in 1793, and by 1834 24 mills were turning out yarn. As Dundee became the centre of the coarse linen industry in Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century, its population increased (by 30,000 between 1841 and 1861). Its shrewd merchants, seeking to diversify their products, saw just their opportunity after raw jute, known in India for centuries and in London since 1793, began to arrive in Dundee in the 1820s via such London merchants such as Thomas Henry and Gilmore & Co. Jute was first spun in Dundee in 1832, but was harder to spin than flax and it took time to learn how to work it in industrial quantities. It was not until 1849 that Robert Gilroy (1810–72), Alexander’s oldest son, was able to acquire an empty factory from the bankrupt William Boyack that had been standing empty for several years. This he expanded into a purpose-built jute mill called Tay [Bridge] Works which, from 1863 onwards, was the Gilroys’ major factory and which was possibly Britain’s largest textile mill of the time. Mark Watson describes it as a “perfect example of a jute mill which expanded judiciously when trade was good, and does much to explain the pre-eminence of Gilroy Brothers”. But rapid industrial growth had not been accompanied by a proportionate increase in the provision of sanitation and housing, and the great wealth of the few contrasted starkly with the poverty of the textile workers, who Chris Whatley has described as numbering “some of the most impoverished” members of Britain’s urban workforce. Thus, between 1841 and 1861, only 568 new houses were built for the expanding workforce and as late as 1901, 72 per cent of Dundee’s population lived in a one- or two-roomed house.

During the second half of the nineteenth century the manufacture of jute in Dundee overtook that of linen. This was partly because of the growing military demand for strong, coarse cloth and partly because of the huge growth in international trade thanks to modern methods of communication and transportation. Gilroys rapidly became one of the two largest jute firms in the world, employing nearly 3,000 people. Because, for many years, Dundee had a near monopoly in the industrial working of jute, the expanding Dundee (population 79,000 in 1851; 160,000 at the end of the century) became known as “Juteopolis” and firms like Gilroys, Grimonds, Cox Brothers and Baxter Brothers as “Juteocrats” (see also V. Fleming). By the 1860s, Gilroys and Cox Brothers were among Dundee’s first jute merchants to bypass the London middlemen and import the material from Calcutta to Dundee directly using their own baling and pressing plants in India and their own fleets of sailing vessels constructed in Dundee. They also invested wisely and profited greatly from the Crimean War (1853–56), the American Civil War (1861–65), when jute production peaked, and the Franco-Prussian War (1870/71). In 1867, George the elder used the family’s new wealth to build the mansion of Castle Roy (demolished 1953/54) in the fishing village of Broughty Ferry, four miles from the centre of Dundee.

But during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Dundee’s jute industry began to decline, and during the years of the First World War, as the demand for Indian raw materials and goods grew globally, Calcutta overtook Dundee as the world’s leading jute manufacturing centre. So in 1920 Gilroy, Sons and Co. Ltd amalgamated with other firms, including Cox Brothers (founded 1841), to form Jute Industries Ltd (voluntary liquidation 1933).

George Alexander, who described himself in Censuses as a Jute Spinner and Manufacturer, became a Director of the family company and it is probable that he had moved to Cheshire, i.e. to the vicinity of Liverpool with its docks, by the time of the 1871 Census, since he and his family do not appear in the Scottish Census until 1891, when they were living at 1, Balgillo Crescent, Broughty Ferry, Dundee. At some point, the family added the name Brydon to its given names.

Gilroy’s mother was the daughter of George Richard Wilson (1838–1907) and Jane Anne Lamb (1841–1908) of The Hermitage, Oxton, Cheshire. George Richard Wilson was originally from Lanarkshire, but became a successful Liverpool merchant and ship-owner. In 1924, after George Alexander’s death, Anne Gilroy moved to Rufflets, just outside St Andrews, a palatial mansion in the baronial style which she had built specially and which became one of the first country house hotels in Scotland.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Kenneth Reid (1892–1915; killed in action on 12 March 1915 at Neuve Chapelle, the day before his 23rd birthday, while serving as a Lieutenant with the 2nd Battalion, the Black Watch);

(2) Isla Brydon (1894–1983); later Forrester after her marriage (1915) to the professional soldier Robert Edgar Forrester, DSO (awarded 27 September 1901 while serving in South Africa with the 6th Battalion, the Black Watch) (c.1877–1915; killed in action on 16 June 1915 near Cuinchy, while serving as a Captain with the 1st Battalion, The Black Watch);

(3) John Douglas (1897–1983); married (1927) Frances Mona Rudd (1898–1974) (West Lodge, Horsham, Sussex); two daughters.

Kenneth Reid was educated at Winchester, became a regular soldier and was commissioned in September 1911, probably with 2 Company, the 2nd Battalion, the Black Watch, and joined them in India (see M.A. Girdlestone and E.H.H. Rawdon-Hastings). The Battalion was stationed in Bareilly when war broke out and on 21 September it sailed for France, where it disembarked in Marseilles on 12 October 1914 as part of the 21st (Bareilly) Brigade, 7th (Meerut) Division, IV (Indian) Corps. From late October until 24 November, the 1st Battalion was involved in the fighting near the village of Gorre, east-north-east of Béthune and half-way to Festubert, and it was during this period that Kenneth Reid was wounded for the first time (cf. Rawdon-Hastings). He was wounded again during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March), and died of wounds received in action on 12 March 1915.

Robert Edgar Forrester served in 1905 as aide-de-camp to the Viceroy of India. While in the trenches at Cuinchy, the Battalion War Diary records on 16 June “Captain R E Forrester Commdg D Company shot through the head 6.00 pm”. He left his wife £13,420 (over £400,000 in 2005).

John Douglas, too, was educated at Winchester but left in 1916 to go to the Royal Military College Sandhurst. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 9th Lancers (“The Dehli Spearmen”) and served with this Regiment until 1928, when he joined the Regular Army Reserve of Officers as a Captain. He rejoined his Regiment at the start of World War II, and was appointed Captain in the Pioneer Corps (London Gazette, no. 35,412, 6 January 1942, p. 188). Later that year he was transferred to the Corps of Royal Engineers, Movement Control Section (LG, no. 35,783, 10 November 1942, p. 4,919).

Frances Mona was the daughter of Mr and Mrs Percy Rudd of Kimberley, South Africa. Henry Percy Rudd (1869–1961), who succeeded Cecil Rhodes as head of the De Beers Consolidated Diamond Mines, was the son of Charles Dunell Rudd (1844–1916), one of the founders with Rhodes of the De Beers Mining Company and of Gold Fields of South Africa Ltd. In 1902 he retired to Scotland and bought the Ardnamurchan Estate.

Education

Gilroy attended Ardvreck House Preparatory School, Crieff, Perthshire (founded 1883), from c.1896 to 1902, after which, like his brothers, he attended Winchester College (1902–08). Here he became Head of ‘H’ House, a Commoner Prefect and Captain of Commoner VI (the six-a-side game of football specific to Winchester that is known as “our game”) (1906–07). He was an excellent wicket-keeper and a useful batsman and played against the MCC at Lord’s in his final year. In July 1908 he captained the Winchester XI (with I.B. Balfour in the team) in the disastrous game against Eton after he had just recovered from mumps and when four out of five of Winchester’s first players were incapacitated by the illness.

He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 October 1908, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1908. On 23 October 1908 he was awarded the Diploma in Forestry alongside 13 other Magdalen men, four of whom would be killed in action (G.H. Morrison, M.M. Cudmore, G.W. Cattley and T.Z.D. Babington). During his time at Magdalen he played cricket in the College’s First XI: six members of the team (M.K. MacKenzie, Gilroy himself, H.M.W. Wells, the two Cattley brothers (G.W. and C.F. Cattley and I.B. Balfour) would be killed in action. Gilroy took the First Public Examination in October 1909 and Michaelmas Term 1910, but left without taking a degree after Trinity Term 1911 and went into his father’s business in Dundee. He was a keen golfer and also played cricket for Forfarshire, gaining distinction as both a batsman and wicket-keeper. An obituarist wrote:

He was a young man of fine character, and had proved himself a brave and most efficient officer. Among sportsmen he was exceedingly popular, and this was due not only to his prowess on the cricket field, but to his manly and pleasing personality.

War service

Gilroy, who had served in the Winchester College Officers’ Training Corps for two terms and was 5 foot 10½ inches tall, enlisted as a Private in the New Army on the outbreak of war. He applied for a Temporary Commission on 21 August 1914 and within a few months obtained one in the 8th (Service) Battalion, The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders), not long after it was formed at Perth on 21 August 1914. He was promoted Lieutenant on 10 February 1915, while the Battalion was training in the Aldershot area.

The Battalion’s 29 officers and 1,007 other ranks (ORs) disembarked at Boulogne on 12 May 1915 as part of the 26th (Highland) Brigade, 9th (Scottish) Division. It arrived at Bailleul on 17 May and stayed in that area until 26 May when it began to march via Nieppe to Steentje, where it stayed until 24 June. From 26 to 30 June the Battalion was in the trenches near Fouquerieul and then, after 30 June, spent time in the trenches east of Festubert. From 6 to 17 August it was in the front line, about midway between Plantin and Festubert, and then, briefly, in billets at Robecq, after which it rested and trained behind the lines at Béthune until 1 September. From 2 until 21 September, four days before the start of the Battle of Loos, the Battalion was in and out of the trenches between Annequin and Vermelles, holding the firing line while the British and German artillery fought a duel over their heads and machine-guns sprayed the enemy front line. After moving into the line late on 24 September opposite the fortified German hillock known as the Hohenzollern Redoubt, the 9th Division spent the night checking rations, water and ammunition in closely packed reserve trenches. The 2nd Division was on its left, just to the south of the La Bassée Canal, and the 7th Division on its right, just to the north of the Vermelles to Hulluch road. So Gilroy was less than a mile to the north of the slightly younger F.M. Carver, who had matriculated at Magdalen a year after Gilroy had left.

At dawn – 05.30 hours – on 25 September, following a 40-minute-long artillery bombardment of the German trenches, the Division, with 26th and 28th Brigades leading on the right and left respectively and the 27th Brigade in reserve, advanced due east under cover of a gas attack to capture the Redoubt. Although the attack, with Gilroy’s Battalion in its second wave, was met by withering machine-gun fire from the left, the Battalion took the Redoubt and several other significant objectives by 07.00 hours, and by 09.30 hours had pushed on to the west end of Fosse No. 8. Gilroy’s Battalion managed to hold this line until 13.30 hours under continuous artillery, machine-gun and small arms fire, but found itself in a very exposed position because the Battalion on its left had not managed to advancing equally far and the Battalion on its right had retired. A relief was organized, but while it was in progress the Germans counter-attacked on the right and Gilroy’s Battalion was not able to retire until 02.30 hours on 26 September. Gilroy himself, however, survived the first day of the battle unscathed since he and two other officers had been deliberately held in reserve to fill the gaps that would inevitably be caused by officer casualties. But on 27 September, when Gilroy and the other two men rejoined the 8th Battalion, 26th Brigade advanced and occupied Dump Trench, to the east of the Hohenzollern Redoubt – which would not be retaken by the Germans until 3 October – and for the rest of that day helped the badly depleted Battalion to resist the increasing German pressure. When the 8th Battalion was withdrawn from the front line at 05.00 hours on 28 September, it had lost 19 of its officers and 492 ORs killed, wounded and missing. He was awarded the MC on 1 January 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,608, 2 June 1916, p. 5,573).

On 28 September 9th Division was relieved in the line by 28th Division and Gilroy’s Battalion went to billets in Béthune. Two days later it travelled northwards to Poperinghe, back in the Ypres Salient, then a relatively quiet part of the front, where it stayed in billets until 4 October. Nine days later, on 13 October, Gilroy’s Battalion was in trenches to the south of Ypres, in the Bedford House and Blauweport area, where it stayed until 18 December before spending nearly six weeks in reserve at Bailleul. During the first period, on 26 October, Gilroy was promoted Temporary Captain and given command of ‘A’ Company.

On 25 January the Battalion returned to Belgium, where it was issued with steel helmets – and spent the next four months alternating between the trenches in the southern sector of Ploegsteert Wood and periods of relative inactivity at Piegeries – “The Piggeries” as it was known to the troops – and Creslow. But then, on 1 June, it began to march eastwards wards the Somme battlefields, training at Argoeuvres from 14 to 23 June in the run-up to the battle, and on 25 June it arrived at billets in La Corbie. On 30 June the Battalion was sent to Celestine Wood, on 11 July to Carnoy, and on the following day it waited in Breslau Alley Trench until 23.00 hours before taking up position 400 yards south of Longueval, a village six miles north-east of Albert on the Bazentin Ridge. On 13 July the Battalion moved back to Breslau Alley trench and at 03.25 hours on 14 July, the 9th (Scottish) Division launched an assault in the direction of Longueval and Delville Wood – “Devil’s Wood” – with Gilroy’s Battalion (to the right) and the 10th Battalion, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (to the left), in the lead, and reached the Wood before a shot was fired. Although the assault was held up by a strong point in the south-east corner of the village which was not taken until 17.00 hours, the Division took two German trenches and the south-western edge of Delville Wood by 10.00 hours. But Longueval was heavily shelled all day and the northern end of the village was not captured until 04.00 hours on 18 July. On 19 July, Gilroy’s Battalion was down to six officers and 165 ORs, having lost 28 officers – including all four of its Company commanders – and 540 ORs killed, wounded and missing during the fighting.

Gilroy was badly wounded during the attack on Longueval on 14 July and died, aged 27, of wounds received in action in No. 5 Casualty Clearing Station, Corbie-sur-Somme, on 15 July 1916. He is buried in La Corbie Communal Cemetery (Extension), Grave 1.D.26, with the inscription: “Dolce et decorum est pro patria mori” (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”: Horace, Odes, III.2.13 – though it should be noted that when Horace wrote this oft-quoted line, he was being ironic). Gilroy is commemorated on the reredos in St James Episcopal Church, Cupar, Fife, Scotland, with the inscription: “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13), an inscription that is also to be found in Latin and English on Magdalen’s War Memorial and in English on the gravestones of C.R. McClure, R.H.P. Howard, J.W. Lewis, R. Roberts, E.G. Worsley, A. Tait-Knight and J.F. Russell. He is also commemorated on the Strathkinness War Memorial, Fife, and the plaque that commemorates the 13 members of the Forfarshire Cricket Club who were killed in action 1914–19. He left £8,515 8s. 7d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgement:

*Chris Whatley, ‘From Second City to Juteopolis: The Rise of Industrial Dundee’, in Billy Kay (ed.), The Dundee Book: An Anthology of Living in the City (Mainstream Publishing: Edinburgh, 1990), pp. 33–50.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Eton v. Winchester’, The Times, no. 38,690 (4 July 1908), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘Dundee Losses: Military Cross Hero Killed’ [obituary], Dundee, Perth, Forfar, and Fife’s People’s Journal, no. 3,056 (22 July 1916), p. 7.

Rendall et al., ii (1921), p. 146 (photo of a drawing).

Alexander Hastie Millar, Glimpses of Old and New Dundee (Dundee: Malcolm C.

Macleod, 1925), p. 65.

Wauchope, i (1925), pp. 163–4 and 179.

Wauchope, iii (1926), pp. 5–25.

S.G.E. Lythe, ‘Shipbuilding at Dundee down to 1914’, Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 11, no. 3 (November 1964), pp. 219–33 (esp. p. 224).

Rachel Britton, ‘Wealthy Scots, 1876–1913’, Historical Research, 58, no. 137 (1985), pp. 78–94.

Enid Gauldie, ‘The Dundee Jute Industry’, in J. Butt and K. Ponting (eds), Scottish Textile History (Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1987), pp. 112–25.

Mark Watson, Jute and Flax Mills in Dundee (Tayport [Fife]: Hutton Press, 1990), pp. 13–14, 22, 56–8, 89 and 108.

Tara Sethia, ‘The Rise of the Jute Manufacturing Industry in Colonial India: A Global Perspective’, Journal of World History, 7, no. 1 (1996), pp. 71–99 (esp. 71–6).

Louise Miskell and C.A. Whatley, ‘”Juteopolis” in the Making: Linen and the Industrial Transformation of Dundee, c.1820–1850’, Textile History, 30, no. 2 (autumn 1999), pp. 176–98.

Warner (2000), pp. 159–92.

McCarthy (2002), p. 46.

E.M. Wainwright, ‘Dundee’s Jute Mills and Factories: Spaces of Production, Surveillance and Discipline’, Scottish Geographical Journal, 121, no. 2 (2005), pp. 121–40.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/66.

WO95/1766.

WO339/11901.

On-line sources:

Electric Scotland, ‘The Industries of Scotland: Linen and Jute Manufacturers’: http://www.electricscotland.com/history/industrial/industry10.htm (accessed 8 April 2018).