Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 3 October 1894

Died: 21 December 1916

Regiment: Royal Flying Corps

Grave/Memorial: Varennes Military Cemetery: I.C.30

Family background

b. 3 October 1894 in Mary-le-Bone, London, the only surviving son (of four children) of William Henry Brereton (1861–1936) and Sarah Brereton (née Ambler) (1860–1937) (m.1884). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 195, Adelaide Road (three servants); by the 1901 Census it had moved to 24, Nottingham Place, Baker Street, Marylebone, London W1, a boarding house with 15 visitors and four servants; and the same address in 1911 with five boarders and five servants.

Parents and antecedents

Brereton’s father was the son of the Reverend Charles Brereton (c.1814–1895) the Curate of St Mary’s, Bedford, and described himself as a Professor of Music. He was a bass vocalist who also played the pianoforte and the organ. On 9 May 1887 he was “duly admitted to the place and office of a Probationary Gentleman of the Chapel Royal”, an appointment that was confirmed in the following year. He served in this capacity until 1935 at least, and by 1924 he was the Treasurer of the Royal Society of Musicians of Great Britain. But he supplemented his Gentleman’s income by keeping a large boarding house on his own account at 24, Nottingham Place.

Brereton’s mother was the daughter of John Ambler (1830–95), a commercial traveller, and she was a soprano vocalist who also taught music at London’s Foundling Hospital, established in 1741 in the Coram’s Fields district of Bloomsbury by the philanthropist Thomas Coram (c.1668–1751). William Hogarth (1697–1764) was also a founding Governor and several prominent eighteenth-century artists were its patrons. But the Hospital was particularly devoted to musical education and originally used blind children for its services. These were made fashionable by Georg Friedrich Handel (1685–1759), who frequently had The Messiah performed there. Later on, the Hospital produced many musicians for military bands in both the Army and the Navy.

Both parents were members of the Royal Society of Musicians.

Siblings

(1) Dulcibella (1886–1964); later Petman after her marriage in 1934 to Richard John Petman (c.1870–1956);

(2) Edith Mary Hill (1889–1962); unmarried;

(3) John Francis (1890–91).

Richard John Petman married Georgiana Mabel Rainier in Hampshire in 1896. They had no children. They emigrated to Canada and settled in Vancouver, where he was a solicitor. She died in 1930 and he returned to England. On 1 May 1916, although he was 44 years old and had no previous military experience, Petman had attested for service in New Westminster, British Columbia, and served as a Private in 121st Infantry Battalion, which sailed for England on 14 August 1916 and was later absorbed into the 16th Reserve Battalion. He served in an administrative capacity in England, was returned to Canada and discharged as medically unfit in March 1918. But he was awarded the British War Medal. The criteria for this medal were slightly different from those applied to the British Army. The medal was awarded to all ranks of Canadian overseas military forces who came from Canada between 5 August 1914 and 11 November 1918, or who had served in a theatre of war. This meant that his service in England entitled him to this medal.

Education and professional life

From 1904 to 1909 Brereton attended Magdalen College School as a chorister, where he began to row with some proficiency. Then, from 1909, when his voice broke, to 1912, he was a day boy at St Paul’s School, London, where he was a member of the (Junior) Officers’ Training Corps and the school’s Shooting XIII; he was in Woolwich C Class for the last three of his six terms. According to his obituarist, Brereton was characterized by “optimism, loyalty, and freedom from care”, but academically his performance was very poor, and for five out his six terms at St Paul’s he came near the bottom of his form and attracted comments like “backward”, “very backward”, “little knowledge”, “prepares work well but is very illiterate”, “requires constant attention”, “inaccurate. Makes no effort” and “the progress made is certainly slow for a boy of his age”. So it sounds as if he suffered from what would now be called dyslexia (a term that was coined in 1887 by the German ophthalmologist Dr Rudolf Berlin (1833–97)). His performance improved during his final term at St Paul’s, and after leaving, Brereton became a clerk with the Peninsula and Orient (P&O) Steam Navigation Company in January 1913.

Magdalen College Choir (1907); Brereton is the tallest boy (fourth from right) sitting in the front row (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College School)

Military and war service

Despite Brereton’s three terms in the Army Class at St Paul’s, he never sought to become a regular soldier. But he attested for the Territorial Forces (TF) on 18 November 1912 – his height was 5 foot 6 inches – and joined the Surrey Yeomanry (Queen Mary’s Regiment) (TF) in January 1913, where he was promoted Lance-Corporal on 1 December 1913. He was still training with that Regiment when war broke out, and he was called up on 3 September 1914. But on 28 November 1914 he left the TF, having been commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 11th (Service) Battalion (Pioneer), the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, on 16 October 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,940, 16 October 1914, p. 8,256). Here he would soon have made the acquaintance of the slightly younger P.H.G. Pye-Smith, who joined the same Battalion as a Second Lieutenant on 22 December 1914.

Brereton disembarked with the 11th Battalion at Boulogne in the early hours of 20 May 1915, and on the same day the Battalion travelled by train to Rubrouck, 40 miles inland, and finally arrived at Vlamertinghe in a fleet of motor buses on 26 May, where, at 11.00 hours, they began work strengthening defence systems and digging support and communication trenches – and took their first casualties. Two days later, despite working two shifts (day and night) and concentrating on the most exposed trenches during the night, the Battalion’s first fatal casualty occurred on 28 May. They continued working on the defences near the north–south Ypres Canal until 11 June, then spent three days in billets in Ypres while working on nearby trenches, taking several casualties from shell-fire as they did so. On 20 June the Battalion returned to its billets in Ypres, and using whatever could be scrounged and the skills of the trained artisans that were already part of it, set up its first workshop for the construction of such useful items as duck-boards and rifle racks. Despite the heavy rain, which made work difficult, and the shelling, which caused a steady stream of casualties, the same pattern of work in roughly the same area continued until late October.

The Battalion had its own machine-gun for defensive purposes that was also used to relieve the machine-gun sections of other Battalions, and on 11 July 1915, the Battalion War Diary tells us that “the machine-gun section in the trenches under Lieut[enant] Paget was relieved by the reserve section under 2nd Lieut[enant] Brereton and Serg[ean]t Rawson […] having been in the trenches for nearly seven days”, a remark which goes to explain the remark in one of Brereton’s obituaries that he “was for some time in charge of a machine gun”. On 29 July the Battalion was asked to “stand to” in case of a German breakthrough, and when the heavy fighting continued in August, the Battalion saw the destruction of St Martin’s Cathedral in Ypres and helped bring out bodies, and was sent to the area of Sanctuary and Zouave Wood in order to repair trenches and damaged rifles, and provide carrying parties.

On 22 October, after three months of heavy work in the front line, the Battalion was sent back westwards by train to Poperinghe, and then marched the five miles westwards to billets in Watou, where it rested and trained for nearly a month. On 19 November the Battalion returned to its billets in Ypres, where it did similar work, but also worked on the trench tramway system to Sint Jaan. From 15 to 31 December the Battalion was back in Watou, but was “stood to” on 19 December, when a German attack was repulsed, after which it worked on the canal bank defences at Elverdinghe, just north-east of Ypres, until 13 February 1916, when it left for a month’s rest and training in billets at Ledringhem, 20 miles west of Ypres and south-west of Wormhout in northern France.

On 19 February 1916, the Battalion left Ledringhem: it spent 20 to 28 February at Villers Bocage, a small town that straddles the N25 c.12 miles south of the cross-roads town of Doullens, and 28 February to 3 March at Fosseux, halfway between Doullens and Arras, before moving to Dainville, a south-western suburb of Arras, from where it worked on nearby trenches until 11 March. On the latter date, the Battalion moved into Arras itself, which was relatively quiet in comparison with Ypres, and worked on the defences at nearby Ronville, Achicourt and St-Sauveur until 26 July. On this day it began to travel in a wide circle south-westwards, via Beaumetz-lès-Loges and Ivergny, further over to the west until finally, on 7 August, it arrived at a location 1,000 yards south-west of Albert. Throughout the rest of August and September, Brereton’s Battalion constructed strong-points, repaired trenches, and worked on improving roads in this general area, suffering a steady stream of casualties as it did so; on 17 and 24 August it acted as the Reserve during the fighting near Delville Wood.

Although Brereton officially left the 11th Battalion on 25 August 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,748, 12 September 1916, p. 8,988) and joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) on the following day, when he graduated as a Flying Officer (Observer), he had actually left the 11th Battalion at the beginning of June, possibly because his work as a Pioneer had become too boring for him, and had been attached to No. 6 Squadron for training, probably on 3 June 1916. From 2 to 22 July Brereton was on a temporary posting in England and on his return it is probable that he briefly rejoined No. 6 Squadron. But on 1 October he was posted to No. 5 Squadron and two days later moved to No. 15 Squadron, at Léalvillers, between Amiens and Arras, in which F.H. Hodgson had been serving as a pilot from 8 June 1916. However, Hodgson had left after being seriously wounded on 6 September 1916. No. 15 Squadron had been formed from a flight of No. 1 Reserve Squadron at South Farnborough, Hampshire, on 1 March 1915. It worked at Hounslow from 13 April to 11 May 1915 and was then stationed at Dover until 23 December 1915, equipped with the Royal Aircraft Factory’s B[lériot] E[xperimental] 2(c). During this stay, one of its pilots, John Aidan Liddell (1888–1915), was awarded the VC for his exploits on 31 July while on a reconnaissance mission over the area Ostend/Bruges/Ghent.

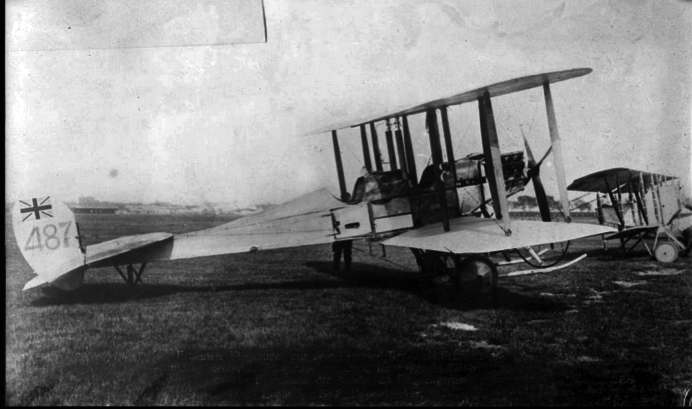

The BE2, a twin-seat (tractor) biplane, had been in service with the RFC for about three years, and the BE2(c), of which c.3,500 were built, was less a modified and more a redesigned version of its predecessors. It had new wings that were equipped with ailerons, not wing-warping, as its control surfaces, and increased dihedral and forward staggering; it was given an enlarged fin to prevent swinging on take-off and improve its spin recovery; and it had a streamlined cowling that gave it a much more modern appearance. Although, unlike the FE2(b) and FB5 (see A.S. Butler and H.M.W. Wells), it had a single, enclosed fuselage, its V-8 engine gave it a similar top speed (72 mph) and ceiling (10,000 feet), which it took 45 minutes to reach. Because of its well-known stability, it was unsuitable as a fighter, but ideal as a light bomber and photo-reconnaissance machine.

Nevertheless, by late 1915 the BE2(c), too, had become an easy target for the Fokker E1 monoplane fighter (the Eindecker; see Butler and Wells) and was nicknamed “kaltes Fleisch” (“dead meat”) by the German pilots. No. 15 Squadron arrived at St-Omer, in France, on 23 December 1915 and was first stationed at Droglandt, near Cambrai, as part of 2nd Wing, where it was used mainly for reconnaissance in the Courtrai/Menin area. Once the 4th Army was formed on 5 February 1916 under the command of General Sir Henry Rawlinson (1864–1925), No. 15 Squadron, in accordance with Trenchard’s restructuring of the RFC (see Butler and Wells), had joined it on 8 March 1916 and was sent to Marieux, well to the west of the Somme Front. During the run-up to the Battle of the Somme the Squadron had been engaged in escort duties, keeping watch on the enemy trenches and train movements, offensive patrolling, counter-battery observation for the artillery, light bombing and photographic reconnaissance on behalf of VIII Corps. This was commanded by Lieutenant-General Aylmer Hunter-Weston (1864–1940), who had gained a reputation for incompetence as a result of his handling of VIII Corps on Gallipoli during the previous year. On the Somme, VIII Corps was initially responsible for the Northern Sector of the British line between the Rivers Ancre and Serre and opposite Gommecourt and Beaumont Hamel.

On 25 June 1916, the Squadron had taken part in the RFC’s mass assault on German observation balloons, and on 6 July its size was increased from 12 to 18 machines. On 7 July it was joined by Lieutenant William Barker (1894–1930), who would become Canada’s top flying ace during World War One with 52 victories, and Canada’s most highly decorated soldier ever, winning the VC, the DSO and bar and the MC and two Bars. When V Corps, under Lieutenant-General Sir Edward Fanshawe (1859–1952), replaced VIII Corps in the Northern Sector in mid–late August 1916, No. 15 Squadron became part of the new Corps. It was then used mainly for bombing missions, such as the one on 6 September 1916, when five BE2(c)s from 4, 7 and 15 Squadrons dropped one-and-a-half tons of bombs on Bertincourt airfield, south-east of Arras, and during which Hodgson was seriously wounded. Partly because of its new role and partly because of the increased availability of fighter aircraft, No. 15 Squadron logged “a bare half-dozen combats […] during the month of September [1916] and these were all of an indecisive character resulting in the enemy retiring after an exchange of shots, usually made at a considerable range”.

On 2 October 1916, the day before Brereton joined it, No. 15 Squadron was moved from Marieux to the airfield at Léalvillers, about 10 miles to the south-east. On 20 October 1916, Brereton and his pilot, Lieutenant S.V. Thompson, who survived the war, were involved in their one and only recorded combat, for which a combat report exists. They were engaged in artillery observation over Beaumont Hamel at a height of 4,500 feet when they “saw four hostile machines coming down in spirals behind us”. Thompson

turned and attacked one machine from above. This machine dived away after having [taken] ½ drum from [our] front gun on [his] port side at 150 yds. Fired at it. We turned and attacked two others behind us with [the] front gun, about two more drums [were] fired at them from 100 to 300 yds. All the four of them went off towards Achiet-le-Grand. Another [BE]2(c) and a De Havilland Scout were also engaged with the same machines. One of the last two machines was hit in the fuselage with several tracers. The hostile machines did not seem to be firing at all. No damage to my machine. […] This was fortunate, for a few minutes previously, east of Grandcourt, this same BE[2(c)] had had one longeron, two aileron spars, and a top main spar shot through in an encounter with four other hostile aeroplanes.

On 31 October 1916, Brereton was promoted Temporary Flight Lieutenant (Captain), and probably confirmed in that rank during the following month (London Gazette, no. 29,902, 12 January 1917, p. 564). On 10 November 1916, the day when Brereton went on leave for a week, probably only in France, No. 15 Squadron played a prominent part in the capture of Beaumont Hamel, and in December 1916, after the end of the Battle of the Somme, it was used mainly for artillery observation with XIII Corps, now positioned to the north of V Corps, on the northern extremity of the British front line.

Varennes Military Cemetery I.C.30 (Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; © The War Graves Photographic Project)

Brereton’s death on 21 December 1916, after he and his pilot had spent two hours over the lines on an artillery flight, was deemed an accident, for the engine of their aircraft failed during landing, causing it to lose speed and dive into the ground. Brereton, who was due to return to England in January 1917 to retrain as a pilot, was killed instantly, aged 22, and his pilot, Second Lieutenant Markham, was injured but survived the war. In a letter to his parents that they received after his death Brereton wrote: “I have had the honour to fall for England. Do not on any account grieve for me, but rather be proud you were able to have a son to offer.” The effects returned to his family included a small prayer book, a Bible, two pipes, a tobacco pouch, and a gold ring. On 27 December 1916, the diarist and Fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb wrote in his Diary: “We were grieved today by the news of the death in action of Herbert Brereton, our chorister, whom we had known since he came to our house as a child of 11 at our first Xmas together with Tony Scatterford.” He was buried on 25 January 1917 in Varennes Military Cemetery, Grave I.C.30; the inscription is “Until the Day”. He left £248 16s 1d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Our Roll of Honour – XVI’, The Pauline, 35, no. 230 (March 1917), unpag.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary’, ibid., p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Roll of Honour: Lieut. H. Brereton, R.F.C.’, The Lily, 11, no. 11 (March 1917), p. 134.

Bebbington (2014), pp. 80–5.

Archival sources:

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161.

RAFM (Casualty Card, Brereton, Herbert).

AIR1/166/15/153/1.

AIR1/689/21/20/15.

AIR1/1219/204/5/2634.

AIR1/1359/204/21/7.

AIR76/53.

WO95/1890.

WO339/10539.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Foundling Hospital’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foundling_Hospital (accessed 6 July 2018).