Fact file:

Matriculated : 1903

Born: 8 May 1883

Died: 20 April 1915

Regiment: East Surrey Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery, Wytschaete: 6.G.27

Family background

b. 8 May 1883 as the third son (five children) of Robert Norton, FRGS FSA (1844–1920) and Edith Norton (née Holland) (1845–1931) (m. 1875). At the time of the 1891 Census the family (plus three servants) was living at Penrhiwardwr, Eflwysbach, Denbighshire; at the time of the 1901 Census the family (plus seven servants) were living at 41, Hertford St, Mayfair, Westminster, London W1. It later lived at 16, Kensington Palace Gardens, London W8 (now in the middle of embassyland and reckoned to be one of the most expensive residential streets in the world), and Coombe Croft, Kingston-on-Thames, Surrey.

Parents and antecedents

Before settling in England, Norton’s father had worked as a merchant in Rio de Janeiro for Messrs Norton & Megaw Co. Ltd. He and Matthew Walker had founded the firm in 1868 with the formal seal of approval of the Emperor Don Pedro Segundo, using substantial funds borrowed from F.S. Hampshire and Co. Ltd (Santos), for whom Robert had previously been working. The firm must have been successful since the loan was repaid within two years and the business closed down only recently.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Harry Egerton (1877–1950) (m. [1909] Mary Froude Llewellyn Bellew [1866–1962]);

(2) Robert Holland (1878–1965) (m. [1909] Mabel Violet Megaw [1889–1967]);

(3) Margaret Eleanor (1880–1959) (later Swanwick after her marriage [1904] to Eric Drayton Swanwick [1871–1955], a solicitor);

(4) Frederic Herbert (1888–1968).

In 1911, Robert Holland was a barrister.

During the war, Frederic Herbert was a Private in the Cyclist Corps and then in the Suffolk Regiment and went to France on 16 April 1915.

“He had good all-round abilities and in particular much literary and artistic capacity: gifted and amiable, he showed promise of a life of honourable usefulness and perhaps of distinction, now, alas! not to be realized.”

Education and professional life

Norton attended Bilton Grange Preparatory School, near Dunchurch, Rugby, Warwickshire [founded at Yarlet Hall, Staffordshire, 1873; moved to its present site 1887; cf. I. Bayley Balfour], from c.1890 to 1897, then Uppingham School from 1897 to 1902 (cf. S.L.M. Mansel-Carey), and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1903, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1903. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Michaelmas Terms of 1904 and then read for an Honours Degree in Modern History. He was awarded a 4th in Trinity Term 1906 and took his BA on 20 October 1906 (MA 1911). According to President Warren, “he had good all-round abilities and in particular much literary and artistic capacity […]: gifted and amiable, he showed promise of a life of honourable usefulness and perhaps of distinction, now, alas! not to be realized”. He originally intended to be a barrister, joined Lincoln’s Inn, and was awarded a 3rd class degree in Constitutional Law and Legal History by the Council of Legal Education in April 1908. But instead, in October 1908, he began a two-year course at the School of Architecture at University College, London (UCL), under the distinguished architectural historian Frederick Moore Simpson (1855–1928), who was Professor of Architectural History at UCL from 1903 to 1919. In October 1908 he registered for the course in Architecture; in November 1909 he registered for courses in Building Construction and the History of Architectural Development, plus a half day at the Slade School of Art; and in October 1910 he registered for an evening class in Architectural Design and completed a two-year course in 1913. He then, like G.M.R. Turbutt a few years previously, became a pupil of Edward Prioleau Warren (1856–1937), the brother of Magdalen’s President Warren, of Bedford Square, London W1; he took his MA alongside J.L. Johnston on 30 June 1911. Norton was a competent visual artist and a keen traveller – while he was still an undergraduate at Magdalen he visited Germany, the part of the Habsburg Empire that would become Czechoslovakia after World War One, and Sicily – and he also wrote occasional articles for the literary press, some of which evoke a rural England that was passing and a European past that had gone. The same sense of history can be found in his poetry, a selection of which was included in the Memoir detailed in the Bibliography. The poem ‘Pageantry’ (1907), where Shakespeare’s Henry V is all too audible, seems to suggest that it is still possible to recall the glories of that past by imaginative re-enactment.

Pageantry

[The Oxford Pageant, June 27th–July 3rd, 1907]

Enclosèd within walls of seven days make,

A seven day cycle set before our eyes,

Of all pertaining to our Heritage.

For this brief time we hear the trumpet’s call,

For this brief span we watch the march of years.

A pageantry and royal magnificence,

A progress medieval, day when kings were kings.

Drum in our ears the voices of the Past,

Ring bells to shake the ivied casement too,

To praise though silently, and late

Is now our privilege, the deeds, the thoughts,

The actions of a race, our pattern for all time,

Our ancestors, our very kin in blood,

To these in joyful reverence bow we now our knee.

Gone pious founders of these glorious piles,

Gone those that worked them, all are gone,

Even the very priest that consecrated them,

Gone are the souls that sang their praises here,

Gone are the ravagers to oblivion most,

But are they past recall? Ah no!

For here to-day we see them soul for soul.

And we remain, O wondrous tale of men,

A race still English with the same sinews

That fought at Cressy and at Agincourt

Inhabit now these halls, these cloistered hearths.

Tuned are the spirits to another chord,

But still in patriotic zeal the same,

Always the same, in joy, in hope the same,

In noble presence the same, bow to the Past.

But in other poems, the focus is more on the brevity of life and the inevitability of death, on decay and the irretrievable loss of youth. They suggest, like so many poems by young men of the time, a familiarity with the early poems of W.B. Yeats and A Shropshire Lad (1896) by Alfred Edward Houseman (1859–1936), albeit without their self-deflating irony. Here is an example:

Reverie

Göhrisch (Sächs[ische] Schweiz), August 1907

As in the woods I wander musing,

Amid pine stems straight and stately,

Stems in the gentle sunlight, orange-fringed,

(Some perchance rooted sixty years gone by!)

Life seems a fleeting vision truly –

E’en as the speck of sunlight through the boughs,

Which dances here and there is gone for ever,

Merged in the evening’s shadowy gloom,

So do we shine in dance for one brief step.

These stalwart pines, themselves are doomed also,

And in due time a younger sap will rise

Up in their place and vaunting to the heavens,

Supplant them, e’en so as in their youth,

Other men lived and most have died anon.

When making his will, Norton gave his address as 13, Kensington Palace Gardens, London, and 7, Stone Buildings, Lincolns Inn [London WC2].

Military and war service

Soon after leaving Oxford, Norton joined the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”) on 18 April 1908 and served with the Cavalry Squadron. Then, on the outbreak of war, like a large number of other young men who had been in similar organizations at school and university (see A.H. Huth, C.R. Priest, E.F.M. Brown), Norton joined the 16th (Service) Battalion (Public Schools), Middlesex Regiment (The Duke of Cambridge’s Own), that had been raised in London on 1 September 1914, as a Private. But he was soon commissioned Second Lieutenant (16 October 1914) and transferred to the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, the East Surrey Regiment, the same unit as Huth and R.H.P. Howard. Like them, he was soon attached to the Regiment’s 1st Battalion, part of the 14th Brigade, 5th Division, but did not arrive in France until 26 January 1915, two days before Huth joined the Battalion.

The 1st Battalion had served in France since 15 August as part of 14th (Infantry) Brigade, 5th Division, participated in the Retreat from Mons (during which it lost well over 372 men killed, wounded and missing), fought in the Battle of Le Cateau (26 August), and taken part in the Battles of the Marne and the Aisne. By 10 October, it had reached Diéval, 10 miles south-west of Béthune, and it took part in the Battle of La Bassée (10 October) and the fighting for Richebourg L’Avoué (13 October) and Lorgies (23 October). It then moved northwards into the Ypres Salient, near Mount Kemmel, dug in for the winter in the trenches east of Lindenhoek/Wulverghem, with regular periods of rest and re-equipment at Dranoutre, near Neuve Église, over to the west. The trenches were in such a bad state that the men were issued with gumboots, but at some places the mud was so deep that it came over the tops of the gumboots and cases of enteric fever began to occur. On 24 November the Battalion finished an eight-day stint in the trenches when they suffered 58 casualties killed, wounded and missing, marched to Dranoutre, and spent the period from 29 November to 1 December in the trenches near Wulverghem. From 5 to 10 December the Battalion was in Reserve at Neuve Église, in billets for two weeks over Christmas, and then in the trenches again from 29 December to 4 January 1915. Huth had disembarked in France on 12 January 1915 but did not join the 1st Battalion until 28 January. On 3 February 1915 Norton was assigned to the Battalion’s ‘D’ Company when it was in the trenches near Messines, several miles south of Ypres. Despite the appalling mud, the Battalion continued in the above, relatively uneventful routine until 4 April, when it was sent northwards through Ypres to trenches just south-east of the village of Verbranden Molen, where it finally arrived on 11 April.

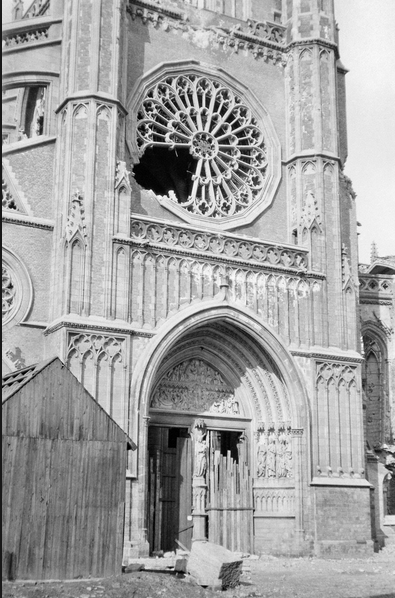

Ypres Cathedral (probably 1914 or mid-April 1915, since the damage in the photograph is not quite as extensive as the following description might lead one to expect and it was written down in April 1915) (Courtesy Imperial War Museum).

“The Cathedral on the left of the Cloth Hall is destroyed. Huge gaping holes are seen here and there. In other places the round mark where the shell has struck and not gone through can be seen. All the doors and openings are barricaded up. The wonderful stained glass windows have been smashed to atoms. Outside among the ruins there is a statue which wonderfully enough has remained untouched, though stones are heaped on every side. Thousands of shells have fallen here.”

This meant negotiating Ypres, and when the Battalion passed through that town on 7 April 1915, Norton was particularly shocked by the immensity of the damage to the town in general and to the Cloth Hall and Cathedral in particular, and on 9 April he described the experience in a letter to his parents:

Alas, what a wreck [Ypres]has become! I took a stroll round last evening and the poor Cloth Hall is completely gutted and most of the Central Tower gone, though not by any means all. The pinnacles at the corners are still intact, and a good deal of the battlements and the whole of the façade is [sic] intact, but still how sad! The interior is full of troops and horses, as indeed is every building here, and the sight reminds me somewhat of what it must have been like in England during Cromwell’s time [Norton may well be recalling here the exaggerated accounts of Puritan vandalism in Magdalen’s Chapel in May 1649, when Cromwell and General Thomas Fairfax dined in College as the guests of John Wilkinson (d. 1650), Magdalen’s new Puritan President]. The Cathedral is a wreck though part is still standing.

A few days later, in a letter to a friend that he probably wrote from Verbrandenmolen, Norton continued his description of the devastation caused by war, albeit with a touch of irony:

This is by far the most comfortable place we have been in, in fact the only town worthy [of] the name we have been in. The mud is still appalling and I wonder if it will ever dry up. It is lovely weather here at present, but every now and then it rains again. It is pitiable to see this poor country! Houses completely gutted, and no glass in any windows, as this always goes first. Our own mess-room has no glass in the windows, and so you may imagine that it is not too warm, as the wind is cold here. It is a curious thing to think that the noise of the war never ceases, noon and night, but is absolutely continuous. […] Luckily these people seem to have inherited a sort of insouciance to war, and they carry on their farming and ploughing in the vicinity of shelling with equanimity. I hope I shall come back. There is so much to see and to do yet, and to know how all this is going to end.

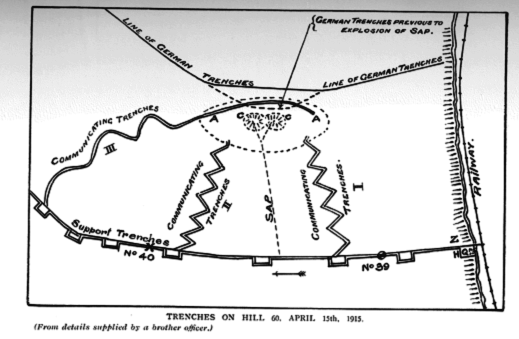

Map of the trenches on Hill 60 that was made on 11 April 1915 (i.e. nearly a week before the battle began in earnest on its crest). The map is somewhat confusing since the bottom is north and the top is south.

But he never did return to the area, for by 02.00 hours on 19 April his Battalion had taken over the British positions on and around Hill 60, where the final phase of the second battle for its possession (17 April–7 May 1915) had begun at 19.00 hours two days previously. But the name “Hill 60” is something of a misnomer and needs some explanation, for the site comprises three artificial mounds of earth just to the south-west of the village of Zwarteleen, about two-and-a-half miles south-east of Ypres, that were created by spoil when a deep cutting was excavated for the Ypres–Comines railway which runs roughly from the north-west to the south-east. The northern part of the site on the eastern side of the railway is known as Hill 60, while the southern part of the site on the western side of the railway, being more of an elongated ridge, was known as “The Caterpillar”. The third mound, about 300 yards down the northern slope of Hill 60 in the direction of the village of Zilleke, was known as “The Dump”. All three mounds were priority objectives because they formed high points in the flat, low-lying Belgian plain, but Hill 60, being about 40 feet high, was the most important of the three because it formed a high point overlooking the lower ground to the west and north-west in the direction of Ypres. Consequently it was an ideal place for observation posts and had been captured by the Germans from the French on 10 December 1914.

Five months later, the second battle for the control of Hill 60 began on 17 April 1915, when the British exploded five huge underground mines (10,000lbs/five tons of high explosive) at ten-second intervals beneath the German positions on the Hill’s crest, followed by a 15-minute-long artillery bombardment. The effect of the explosion was enormous: “Trenches, parapets, sandbags disappeared and the whole surface of the ground assumed strange shapes – here torn into huge craters, there forming mounds of fallen débris.” About 150 Germans were killed instantly by the shock and its effects, and the hand-to-hand fighting began when a Company of the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment), stormed the hill at the cost of almost no casualties. But having crossed the 40 to 60 yards that separated their positions at the base of the southern side of the Hill from those of the enemy on its crest, they found that many of them had been working in their shirt sleeves, without equipment. An eye-witness published a long report in The Times of 26 April in which he said:

Stunned by the violence of the explosion, bewildered and suddenly subjected to a rain of hand-grenades, thrown by our bombing parties, they gave way to panic. Cursing and shouting, they were falling over one another and fighting in their hurry to gain the exits into the communication trenches [which led down the northern side of the hill]; and some of those in [the] rear, maddened by terror, were driving their bayonets into the bodies of their comrades in front.

But although the British were able to capture the crest of the Hill in a few minutes – which, because of the explosion, now possessed two huge craters on its northern side and three on its southern side, approximately in a straight line – they almost immediately came under fire from German artillery that was ranged around three sides of the Hill and the whole position soon “became obscured in the smoke of bursting shells”. The British artillery responded in kind, and a terrific artillery duel “was maintained far into the night” of 17/18 April, during which the Hill’s new occupants had to throw up new parapets that faced towards the Germans, block the old German communication trenches, dig new communication trenches on the British side so that reserves could be brought up and the wounded could be taken down to the 14th Field Ambulance, and “generally make the position defensible”. Meanwhile, their German opponents crawled back up the Hill via their former communication trenches in order to throw hand grenades over the barricades and into the craters that were now in the hands of the British. And for the next four days, the same kind of intense, hand-to-hand fighting surged backwards and forwards across the Hill’s shattered landscape and its mess of winding trenches and along a sector of the front that was c.250 yards wide and 200 yards deep. An officer noted: “The Hill and communication trenches were littered with dead and dying and the sights witnessed were most distressing.”

Despite heavy and continuous shelling, the West Kents held Hill 60 until they were relieved at about 02.00 hours on 18 April by the 2nd Battalion, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) (see A.J.F. Hood). But later that morning, at 04.30 hours, a German counter-attack on the left of the hill forced the KOSB back from the front line of trenches, and by the time the 2nd Battalion was relieved in its turn at 11.30 hours by the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) (see G.U. Robins), it had lost 211 men killed, wounded and missing. Although the Hill was heavily shelled throughout the rest of 18 April, the Germans launched no more counter-attacks during the daylight hours and between 02.00 and 05.00 hours on 19 April, the 2nd Battalion, the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, was relieved by ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies of Norton’s Battalion, supported by the 1st Battalion, the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Regiment. After helping the survivors on the crest of the Hill to force the Germans backwards and out of their newly regained footholds there, some of the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Companies plus ‘A’ and one half of ‘C’ Company of the East Surreys took over the front trenches (marked ‘A’ to ‘A’ on the map above), supported by five machine-guns. The other half of the East Surreys’ ‘C’ Company, where Huth was in command, were tasked with holding the 300-yard front, which extended from the right-hand crater on the Hill and down the Hill’s right-hand side to the bridge over the railway; one half of ‘D’ Company (now minus Norton, who had been transferred to a platoon in ‘B’ Company) was in support in the trenches immediately behind the Hill; the other half of ‘D’ Company held the fire and support trenches on the left-hand side of the Hill; and Norton’s ‘B’ Company held the fire and support trenches on the left-hand side of ‘D’ Company (marked with an ‘x’ just above ‘No. 40’ on the map). And so it was that Norton was now in command of the platoon that was tasked with holding the middle communication trench (designated ‘II’ on the map) that zig-zagged up the Hill to the left-hand side of the left-hand crater.

The late evening of 18 April and the small hours of 19 April were fairly quiet, but throughout the daylight hours of 19 April another artillery duel took place, causing much damage and an “enormous” number of casualties, especially in the support and three communication trenches behind Hill 60. At 17.00 hours the shelling became even worse for an hour and as the casualty figures increased and the damage to the trenches became more extensive, it was realized that more reinforcements were badly needed. So Norton and another officer gathered together as many men as possible – about 30 Other Ranks from their own Battalion and the 1st Battalion of the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Regiment – and judging that the badly damaged 250-yard-long Communication Trench ‘II’ was “just practicable”, led them up to the top of the Hill across the ghastly detritus of modern mechanized warfare. So the survivors on Hill 60 worked throughout a second night at repairing the damage done to their trenches by shelling, and it was while Huth was supervising the work being carried out by his half of ‘C’ Company that he was killed in action, aged 33, by a shell or hand-grenade.

According to the East Surreys’ Historian, at 11.00 hours on 20 April 1915 “a most terrific bombardment of the position” recommenced, with the Germans making greater use of heavy howitzers, which enabled them to lob shells with greater accuracy onto the positions behind the Hill, blowing in earthworks and trenches and burying their occupants. And for a second time in two-and-a-half days:

the bursting of shells was incessant & the noise was deafening. The little hill was covered with flame, smoke and dust, and it was impossible to see more than ten yards in any direction. Many casualties resulted, and the battered trenches became so choked with dead, wounded, débris and mud as to be well-nigh impassable. Every telephone line was cut and all communications ceased, internal as well as with sector headquarters and the artillery, so that the support afforded by the British guns was necessarily less effective.

The East Surrey’s Adjutant, Captain Damer Wynyard (1890–1915), was blown to bits by a shell at about 11.30 hours while he was attending a group of wounded men, and their Commanding Officer, Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Herbert Paterson (1869–1915), was also killed in action when a shell hit the Battalion HQ (at point ‘z’ on the above map), over by the railway line. There is some doubt about the circumstances of Norton’s death on 20 April, but he was certainly still alive between 11.00 hours and noon since he commanded the detail which buried Wynyard’s remains. He also survived the concerted German assault on the southern and eastern slopes of the Hill that began at 18.30 hours, supported by a heavy artillery bombardment during which, according to an officer who survived the attack, “the enemy employed shells giving off asphyxiating gases freely”. This attack was driven off, mainly by “our machine-guns” which did “tremendous execution”, as was a second German attack at about 20.00 hours. One source later claimed that Norton was killed in action during the earlier attack by a heavy howitzer shell while bringing reinforcements up the Hill along a badly damaged communication trench. But that scenario is more appropriate to 19 April than it is to 20 April and besides, by the late afternoon of 20 April there were no more potential reinforcements in the support trenches in the rear. According to a second eye-witness – Norton’s batman, who would have stayed near him during the fighting – he was killed in action, aged 31, by a shot in the head which killed him instantly just after 19.00 hours when he was with the remnants of his platoon and firing at the attacking Germans over the rim of the left-hand crater on top of the Hill. His body then fell back into one of the mine craters, where his batman and another soldier laid it on a sandbag, where it was subsequently hit by a shell or grenade that blew it to pieces.

More reinforcements had arrived on the Hill at about 18.00 hours on 20 April, together with Major [later Brigadier] Walter Allason (1875–1960), who took command of the men who were dug in on its summit. The German shelling died down during the final hours of 20 April, but it recommenced at 03.00 hours on 21 April, and using the barrage as cover, German infantry armed with hand grenades once again crawled up their side of the Hill and hurled them into the “labyrinth of winding trenches surrounding the craters” that formed the British positions, causing the struggle to “surge backwards and forwards”. But the attack was beaten back yet again, and at 06.00 hours, the 1st Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment managed to “climb over the prostrate forms of their fallen comrades”, reach the defenders, and hold the Hill, now a “scene of utter devastation”, for a further two days. Once Norton’s Battalion was relieved, the survivors made their way down the Hill and marched to Kruisstraat, a few miles to the north-west, carrying Colonel Paterson’s body with it for a proper military burial. Despite the legend on the commemorative plaque (below), Norton’s remains were finally recovered, too, and are buried in Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery (south of Ypres), Grave 6.G.27, with the inscription: “And they, the knights of God, shall see his glory” (adapted from the penultimate line of ‘Subalterns: A Song of Oxford’, written in September 1916 by the American poet Mildred Huxley [1899–1998(?)]). He is commemorated by a plaque in St Martin’s Church, Eglwysbach, Denbighshire (also known as Clwyd and Sir Ddinbych). During the three days in which it was involved in the fighting, the 1st Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment suffered c.280 casualties killed, wounded and missing (7 officers killed and 9 wounded; 42 Other Ranks killed, 158 wounded, and 64 missing believed killed), and three of its members were awarded the Victoria Cross (VC). One of these was Private [later Corporal] Edward Dwyer (1895–1916), the second youngest VC of World War One. The fighting for Hill 60 restarted in earnest on 1 May 1915 and ended on 5 May 1915 when the Germans re-took it by means of the gas attack (chlorine) that killed G.U. Robins. By the time that the Germans finally abandoned the Hill on 15 April 1918, it had claimed the lives of three members of Magdalen besides Huth, Norton, and Robins – R.H.P. Howard, J.R. Platt and G.F.W. Powell – and would contribute to the post-war death of a seventh – A.J.F. Hood.

St Martin’s Church, Eglwysbach, Denbighshire

(http://www.clwydfhs.org.uk/eglwysi/eglwysbach.htm)

President Warren wrote a warm letter of condolence to Norton’s parents soon after their son’s death, and his father, Robert, visibly moved by Warren’s sensitivity and percipience, sent him two letters of thanks shortly afterwards. In the first, dated 10 May 1916, Robert Norton wrote: “Such a letter and expressions of affection and appreciation of Tom’s talents & character are the greatest solace to his Parents” and in the second, undated, he declared that of the hundreds of letters he and his wife had received about Tom, “none has been more appreciated and given us more comfort than the letter you have so kindly worded. It is indeed a comfort to us to know that you liked the dear Boy and had discovered some fine points in his nature.”

On 25 July 1915, a private Memorial Service for the relatives and friends of the 48 officers of the East Surrey Regiment who had lost their lives in the war so far took place in All Saints Church, Kingston-on-Thames, Surrey, and the list of the fallen which prefaced the long report that appeared in the Surrey Advertiser of 30 July 1915 contained the names of three Magdalenses: Norton, Huth, and Howard. Consequently, the large congregation was “principally composed of relatives and friend[s] of the fallen officers, but a number of local residents also attended to mourn the gallant dead. […] Ladies predominated, and the many evidences of deep mourning visible in the church told their own pathetic story of family bereavements created by the cruel war.” Nevertheless, the approaches to the church “were lined by men of the East Surrey Regiment who are recovering from wounds received in battle”; and the church, whose interior had been “tastefully decorated for the occasion with a profusion of palms, ferns, and white flowers” was already the resting place of “several battle-stained flags of the East Surrey Regiment”. Although the arrangements had been made and the form of service drafted by officers from the Regiment’s Kingston Depôt, they had been approved by Dr Samuel Taylor (1859–1929), the second, and recently appointed, Suffragan Bishop of Kingston (1915–22). The church choir was in attendance, and the regimental band from the East Surrey Depôt supplemented the organ in the accompaniments. While the congregation was assembling[,] it played the “exquisitely plaintive” Adagio from Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique, “and almost before the last lingering note had died away[,] the opening strains of Borowski’s sublime Elégie stole softly from the organ.”

The service itself opened with the familiar Victorian hymn, ‘Brief life is here our portion’, after which one of the clergy said the opening sentences of the Burial Service. Special Psalms (15, 23 and 121) were sung to appropriate chants, and were followed by the anthem ‘Blest are the departed’ from Spohr’s Last Judgment, “and while the choir were blending their voices in the grandly modulated harmonies[,] the radiant rays of the sun filtered through the stained-glass windows and lit up the somewhat sombre interior of the church”. The lesson was taken from St John 11: 11–28, and was followed by the hymn ‘The Saints of God, their conflict past’, sung to Sir John Stainer’s “beautiful tune”. The prayers were read by the Revd Albert Stewart Winthrop Young (1842-1918),, the Vicar of Kingston, who also intoned the versicles, and were followed by the “gladsome hymn” ‘Ten thousand times ten thousand’. “All tears were stemmed by the assurance it gave of victory over death, and the combined voices of the choir and congregation, augmented by the sonorous volume of tone produced by the organ and band, had the effect of transforming the inspiring tune into a veritable paean of triumph.”

The Bishop of Kingston then delivered an address which the reporter described as “teeming with touching sentiment that went home to the hearts of all who heard it”. It is worth including here in considerable detail as it is a highly professional piece of religious rhetoric which begins with a sincere attempt to offer comfort to members of the congregation who had lost friends and loved ones. The address began by dwelling on the mysterious nature of their suffering and then justifying it in terms of its moral purpose and achievement. But its concluding, climactic paragraphs move away from the transcendent and the moral and become more of a skilfully penned exercise in jingoism which made considerable use of horror stories about German atrocities that were circulating in the popular press, especially Lord Rothermere’s newspapers, and contrasts the alleged traditional moral superiority of the British soldier and his officers with their German counterparts.

The sermon begins with Bishop Taylor in a suitably low and intimate key:

It is with mingled feelings that we join in such a service as this to-day. And first of all there is our sympathy with those to whom the fallen were bound by the close ties of relationship and affection. Theirs is the deepest sorrow. That personal loss is not to be talked about. The heart knoweth its own bitterness. We stand by with respect for their grief. It is what each of us at some time in life comes to understand. May they realize more and more fully what so many mourners have done through these long months of war, that those who pass from our sight do not pass out of the love and care of our Father; and though the line seems to us so awfully deep, and the veil so impenetrable, there is no separating line or veil in His sight between the living and those whom we call dead, for ‘all live unto Him’: […] ‘Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.’

The second part of the sermon begins as follows:

And our next thought is one of gratitude. These lives we commemorate were laid down for us. That no invading army has landed on our shores, that we have slept by night in peace, that the din of battle has been kept so far away that it is hard for us to realize the horror of its menace and its suffering – we owe to those who have as truly fought for the defence of England as if the battle had been on English ground. The sights witnessed by the streets of Dinant, by the square at Liège; the brutal wreck of Rheims and Louvain, the cruelties of Aerschot, of Termonde, that which is too sordid to tell, we do well to remember. For, although, as the Belgian poet has said, “although it makes our voices break, though our eyes may burn, though our brains may turn”, it brings to mind part of the debt we owe to those, of whom the fallen officers of the East Surrey Regiment stand as representative to us to-day; for which we would bring our wreath of grateful memory to lay upon their graves. The least of all services done to our brethren is done unto the elder Brother and Saviour of us all, and receives His reward. What then can we do but speak out our thanks for lives laid down, for suffering borne, for the sacrifice of which we may well ask ourselves if we are worthy? “They loved not their lives unto the death.” They have shown us that there is something more precious even than life. In our sight they climbed “three great peaks of honour which we had too much forgotten, Duty, Patriotism, Sacrifice”. We thank them, and we thank God for them; it is part of our goodly heritage as a people, for evermore.

And so to our thoughts of sympathy and our gratitude we add our pride. If pride is ever fitting for us poor mortals, and that within walls consecrated to the worship of the Almighty, it may be felt by us at this time, pride not in ourselves, but in the magnificent bravery of those whose ears are now deaf to both our praise and blame, because they are in the near presence of God. They are not my words, but those of one who has the right to utter them, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in the Field to the 85th Brigade, of which the 2nd Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment formed a part: “Your colours have many famous names emblazoned on them, but none will be more famous or more well-deserved than that of the second Battle of Ypres … I wish to thank you, each officer, non-commissioned officer, and man, for the service you have rendered by doing your duty so magnificently; and I am sure that your country will thank you too.” Those battle honours that begin at Dettingen [1743], that were gained in Europe, Asia, and Africa, North, South, East and West, among them all that long struggle which stretched from April the 22nd to May 13th [1915] will shine, and no name be more brilliant than that of the second Battle of Ypres, one of the most desperate fights of all the great war.

Ours is not a pride for valour and for stubborn endurance alone; it is a pride for the moral quality of it all. Was there ever an army in which men followed their officers with more unquestioning devotion? It is to the credit of both alike indeed, but it began with the confidence in those who could not drive, but knew how to lead; who gave orders for no hard task that they were not themselves ready and foremost to face; who cared out of their hearts for those who looked up to them; who could say with that gallant gentleman, Captain Francis Grenfell [1880–1915; awarded the VC for his part in the Action at Élouges, Belgium, on 24 August 1914], in his last words: “Tell them I die happy. I loved my squadron.” It is our great pride, whether we were to lose, which is unthinkable, or to win, which God grant speedily, that we fought not as brutes but as gentlemen. War is no child’s play, and there have been ghastly scenes enough in this one, but in our record there is no foully-stained page such as degraded officers and men of the German army have written in the towns and villages of Belgium, France, and South Africa; the deep disgrace that will not pass away, that turned the honourable profession of the soldier for his country’s defence into the opportunity of the common ruffian; that in its barbarity knew neither age nor sex, neither fear of God nor pity of man, that has had no parallel for centuries, and has yet to meet stern reckoning, for the cry of a wronged people has gone up to the ears of the God of Hosts.

We do well to be proud of those for whom all that is impossible, whose leaders have had another ideal from their school days onwards – without fear and without reproach. It is that which comes down to us in the old battle cry of Cressy [Crécy (1346)] – “St George for England” – that which is meant by the name of the soldier-martyr who stands for the Empire’s chivalry; which still persists as our ideal [illegible word] of the poor materialised thought of later days.

Let him deride

Whose soul with coarser sense is blurred;

But England loves that unseen guide

Sent forth to work His Master’s word,

Who sleeplessly by land and wave

Hath kept her, and shall keep her thus,

Strong servant of the God who gave

His angels charge concerning us.

After the address the hymn ‘O God our help in ages past’ was sung, and after the Blessing, pronounced by the Bishop, the congregation sang the National Anthem. The band ended the commemorations with Handel’s Dead March in Saul and Largo in ‘C’; four buglers sounded the Last Post, and a solo soprano sang ‘The last sad rites are o’er’.

Norton left £26,665 13s 11d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Langley (1972), pp. 64–70.

*Cave (1998), pp. 19–41.

Printed sources:

[Lieutenant C.W.G. Ince], ‘British Grip on Hill 60: Terrific Assaults Resisted: Incessant Firing’, The Times, no. 40,838 (26 April 1915), p. 7; reproduced in Cave (1998), pp. 28–31 as ‘Eye-Witness at Headquarters in France’.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 17 (30 April 1915), p. 274.

John Buchan, ‘A Soldier’s Battle: The Second Fight for Ypres: April 22–May 13’, The Times, no. 40,905 (13 July 1915), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘For the Gallant Dead: East Surrey Regiment’s Heavy Toll of Officers: Impressive Memorial Service’, The Surrey Advertiser (Guildford), no. 3,963 (31 July 1915), p. 5.

[Ince], (1915), p. 7.

E.B.M., ‘In Memoriam: Tom Edgar Norton’, [brief obituary], University College [London] Union Magazine, 8, no. 4 (November 1915), p. 176.

E.A.B. Barnard (ed.), A Memoir of Tom Edgar Grantley Norton [privately printed] (no publisher, 1915). [The only known copy is in Magdalen Library as Magd. Nort-T (Mem)].

Errington (1922), p. 272.

Pearse and Sloman, ii (1923), pp. 30–77.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 83, 107, 113–16, 237.

Parker (1987), pp. 158–62.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 350.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

OUA: PR 32/C/3/902-95 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to T, E. G. Norton [1915]).

OUA: UR 2/1/51.

WO95/1548 (‘Report on Operations near Zwarteleen on Hill 60: April 17th, 18th, and 19th 1915’ [draft]).

WO95/1552.

WO95/1553.

WO95/1558.

WO95/1561.

WO95/1563.