Fact file:

Matriculated: 1901

Born: 17 May 1883

Died: 21 October 1914

Regiment: Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Grave/Memorial: Poelcapelle British Cemetery: no known grave (name on Special Memorial)

Preamble

A much longer and more detailed version of the life of G.M.R. Turbutt was privately printed by his nephew, Gladwyn Richard William Turbutt, DL, MA (Oxon.), Hon. D. Litt. (Derby), High Sheriff of Derbyshire 1998–1999. See: Richard Sheppard, David Roberts and Robin Darwall-Smith, Gladwyn Maurice Revell Turbutt, 1883–1914 (Higham, Alfreton, Derbyshire: The Higham Press Ltd, 2017), pp. ix + 181. The authors of the book version and this abbreviated version, in which most minor errors have been corrected, would like to acknowledge Mr Turbutt’s generosity and thank him most sincerely for his help and encouragement.

Family Background

b. 17 May 1883 at Ogston Hall, Brackenfield, near Alfreton, Derbyshire, as the elder son of William Gladwin Turbutt, JP (1853–1932), and Edith Sophia Turbutt (née Hall) (1851–1932) (m. 1879). A fine sketch of the Hall by Turbutt’s mother is to be found in the Derbyshire Record Office (D37 MP/75). Not counting workers who lived in associated cottages, the family had 13 servants (including two governesses) living in the Hall at the time of the 1861 Census, 7 at the time of the 1871 Census, 13 at the time of the 1881 Census, 12 (including a governess) at the time of the 1891 Census, 7 at the time of the 1901 Census and 6 (including a governess) at the time of the 1911 Census.

A photo of the south front of Ogston Hall, taken late in the second half of the nineteenth century or the first decade of the twentieth century.

Parents and antecedents

The Turbutts were a well-to-do, politically conservative, Derbyshire family whose name can be traced back to the early seventeenth century. Although the family was high church, it was not so to an extreme, and Turbutt, who found no difficulty in attending Compline and Benediction during his pre-war stays in France, found St Barnabas’ Church, Oxford, with its “processions and incense and such like” “too high” ([IV] Diary 4 June 1905).

A house had stood on the site of Ogston Hall since the Middle Ages, but after the Turbutts acquired the estate from the Revells in 1724, a new Hall was built (1767–68). This was subsequently enlarged (1850–52 and 1864) and Turbutt, who trained as an architect from 1906 to c.1909 (see below), modified the building still further between 1903 and 1913 by adding battlements and a twin-pillared balustrade in the garden. The Hall also contained a fine library (see below). A major portion of the estate, some 515 acres, was broken up into 56 lots and sold on 19 March 1952.

As a committed churchman, William Gladwin had a benevolent attitude towards his tenants and employees that was prefigured, when a senior boy at Harrow, by his ability to recognize every boy in the school. He inherited the Ogston estate in 1872, when it comprised 2,928 acres and produced an annual income of £4,656 (c.£186,000 in 2005). Although English agriculture was about to experience a slump that would last until the end of the nineteenth century, William Gladwin managed Ogston with care. Indeed, before the heavy taxation imposed on such estates by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s Liberal government (supported by 29 Labour MPs) took effect after December 1909 so that they could finance old age pensions, unemployment insurance and increased defence expenditure (see below), he had effected many improvements there.

Nevertheless, William Gladwin was an active Conservative. In 1881 he contested the old East Derbyshire Parliamentary Division (created for the 1868 election and abolished in 1885 under the Redistribution of Seats Act in order to create seven new constituencies), but was defeated by the Liberal Unionist candidate Alfred Barnes, JP (1823–1901). And when the new constituency of Chesterfield was created in 1885, Barnes became its MP, too. For many years William Gladwin was President of the Mid-Derbyshire Unionist Association, and when the Clay Cross Parliamentary Division was created in 1918 (Liberal 1918–22; solidly Labour 1922–50), he held official positions in it and was very active on its behalf. He was for many years a member of Derbyshire County Council, but after being defeated in 1907 he did not seek re-election. He was also a member of Chesterfield Rural Council and Chesterfield Board of Guardians, a Governor of Derby Training College and a Governor of Derby Grammar School until it was placed under the jurisdiction of Derby Borough Education Authority. From 1889 to 1890 he served as High Sheriff of Derbyshire.

William’s son Gladwyn derived his artistic predisposition and abilities from his mother, the third daughter of Thomas Dickinson Hall, JP, DL (1808–79), of Whatton Manor, Nottinghamshire, who was a landowner and member of the gentry. But despite his cultivation and artistic gifts, G.M.R. Turbutt, as will emerge from the narrative that follows, accepted unquestioningly the validity of several middle-class prejudices – notably about Jews, politically active feminists who were campaigning for the vote, and the politically active industrial working class and its representatives.

Horse and trap outside the east front of Ogston Hall, near Alfreton, Derbyshire; the lady in the trap is probably Turbutt’s mother; the young man leaning against the trap and wearing a Harrow boater is probably G.M.R. Turbutt; and the smaller boy standing behind the horse is probably Richard Babington Turbutt (Courtesy of the Derbyshire Record Office, Matlock [D37/MP/167])

Ogston Hall, near Alfreton, Derbyshire, with four people playing croquet; the lady on the left is probably Turbutt’s mother; the lady on the right is probably his older sister; Turbutt is probably the boy in the white shirt with his hand in his pocket; and the smaller boy is probably Richard Babington Turbutt (Courtesy of the Derbyshire Record Office, Matlock [D37/MP/177])

Brother of:

(1) Rachel Gladwyn (1881–1972);

(2) Richard Babington (1887–1964); married (1923) Christine Margaret Dunn (1899–1976); three children.

Richard Babington Turbutt (detail from a photograph of Christ Church oarsmen, 1909) (Courtesy of Christ Church, Oxford).

After attending Harrow School and taking a 4th class degree in Science at Christ Church, Oxford (BA 1909; MA 1918), Richard Babington took the Army Examination as a University Candidate, passed, and was gazetted 2nd Lieutenant (London Gazette, no. 28,172, 22 August 1908, p. 6,305) to the Royal Field Artillery (the 147th Battery, which was equipped with howitzers), and stationed at Woolwich until the end of October 1911 (LG, no. 28,336, 4 February 1910, p. 866). In September 1911, when the Second Morocco Crisis (April–November 1911) nearly brought about a European war, his unit was ordered to have its guns fitted with shields and he was transferred into the Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA). Turbutt wrote in his diary:

The national railway strike was on at the same time and the Government was compelled to use every power at their disposal to quell it promptly for fear of declaration of war. The dockers’ strike was also in full swing. My brother was in part of a force guarding New Cross, & they were encamped in Hyde Park. ([VIII] Anecdota Ogstoniana 1908–14).

On 1 November 1911 Richard’s new unit was ordered to Clonmel, in County Tipperary, and, while training in July 1912 on the Practice Artillery Range at the Glen of Imaal in the Western Wicklow Mountains, Richard had a lucky escape when a shell from his howitzer burst prematurely at the muzzle of the gun, which it damaged badly but without harming any of its crew.

On 31 December 1913 Richard sailed from Southampton with a draft of troops for a spell of garrison duty in Jamaica where, on the outbreak of war, he “worked the wireless station he had set up at Port Royal, Kingston Harbour, for the Admiralty” ([VIII] Anecdota Ogstoniana 1908–14). He was retained there in this capacity until the Admiralty had completed a big new wireless station in the centre of the island at Christiana, then drafted home in early April 1915 and sent to train at Sheerness and Lydd. In September 1915 he landed in France with the 58th Siege Battery as Signals Officer to Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Douglas Hamilton (1867–1936), and in January 1916 he was promoted Captain (London Gazette, no. 29,727, 19 August 1916, p. 8,500) and given command of a section of 6-inch Mk VII guns, acting independently from the rest of the Battery. While serving with this unit during the Battle of the Somme, he was gassed and then severely wounded near High Wood on 27 September 1916, and invalided home. After spending many months in hospital at 27 Berkeley Square, Mayfair, London W1, and then convalescing for a period, he was given command of 390th Siege Battery, RGA, a battery of 6-inch howitzers at Falmouth.

In July 1917 Richard and his Battery were sent to Corso, Italy, and in October 1917 his Battery to Taranto, in the heel of Italy. From here it moved to Alexandria, Egypt, where it remained until January 1918, when it returned to Taranto via Port Said. It then moved north to join General Herbert Plumer’s Army on the River Piave, where it was tasked with backing up the still badly demoralized Italian forces. The Battery subsequently moved to the Asiago Plateau, where it saw out the war. For his services on the Italian front Richard was decorated with the Italian Bronze Medal for Military Valour (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,520, 27 October 1919, p. 3,490). He spent the trying period of demobilization at the Villa Rose, Torreglia, in the Colli Eugenei Hills near Padua, but then suffered a bad recurrence of the malaria that he had originally contracted in Alexandria and was invalided home to Birmingham University Hospital via Badighera, Marseilles and Boulogne. In April 1919 he rejoined the Army at Dover and was moved in succession to Shoreham, Woolwich, York, Ripon, Derby, Gullane, Hornsea, Gonrock, Aberdeen and Broughty Ferry before being given a Territorial Adjutancy at Port Glasgow on the Clyde. In 1921 he was promoted Temporary Major (London Gazette, no. 32,345, 3 June 1921, p. 4,525) and after completing a three-year tour of duty, he retired from the Army in December 1925 with the rank of Major. On coming back to Derbyshire to reside at Higham Cliff, near Ogston, he was offered and accepted the job of sub-agent to the various northern estates of the Conservative politician and Prime Minister Anthony Eden (1st Earl of Avon) (1897–1977) ([VIII] Anecdota). On 21 March 1936 he ceased to belong to the Reserve of Officers on medical grounds (LG, no. 34,266, 21 March 1936, p. 1,819), but during World War Two he became a Sector Commander in the Home Guard with the rank of Colonel. From 1950 to 1951 he served as High Sheriff of Derbyshire.

Education and professional life

From 1892 to 1896 Turbutt was educated at the Reverend George Charles Carter’s (1853–1930; Headmaster 1887–1906) Preparatory School in Farnborough, Hampshire, and he then attended Harrow from 1897 to 1901. Little is known about his time there, but his lyrical description of a House supper that he attended there on 10 December 1904 – i.e. while he was at Oxford – indicates that he was very attached to the place:

Harrow station at last! What joy: It was over a year since I had been down to the dear old place – “Ye scenes of my childhood whose loved recollection / Embitters the present compared with the past.” [Lord Byron, Hours of Idleness] – The sight of the “Hill” inspired in me as it must in the heart of every true Harrovian who loved his school a “thrill” of joy which I shall never forget. To think that I should be back again at that place, the scene of so many joys and sorrows, all of which had become idealized by time, and shrouded in the web of romance, which increases year by year. Even the ugly buildings of the Knoll my old house seemed beautiful. I knew every brick of it, every bar that crossed the windows, & I may say every flaw in the bars, and they brought back the memory of the summer mornings when I used to clamber down sheets let out of a window on the upper storey without bars, to go out birds nesting at 3 a.m. After our cab had rolled its weary way up the hill it stopped at the door of the Knoll – Out we jumped and were received on the door step by our hospitable host, who would not hear a word until he had given us a bounteous tea. The “old chums” match was on, on the same day, & wonderful to relate, we in the old chums were not beaten but we drew with them 2 all. When we went into the House we found a lot of the old boys (familiar faces to us, though we had not seen them for so long). […] Eleven of us were staying in the House, put up where we could get in. Barnes [Richard Langley Barnes (1883–1967)] and I shared a room in the sick rooms. The House supper was put off till eight. We all dressed and came down to a most gorgeous spread prepared by our kind host and hostess. Claret Cup & lemonade to drink and everything that money could buy, reason could allow, and discretion could eat was provided. I sat between Jack Reunert [b. 1881 in Windybrow, Johannesburg, RSA, d. 1946] and C[lare] V[alentine] Baker [1885–1947], both of whom were in the house still, and were when I was there, but how altered. They were both young fellows, now one was a double flannel [i.e. had been awarded two school colours for his sporting proficiency] and the other a 6th form coat and fez [the “fez” is a round hat with a tassel, similar to a nineteenth-century smoking hat, that is worn by Harrovians who play the school’s special version of football], and School racquet players, of course they were on the “Phil” [i.e. members of the Philathletic Club at Harrow, a club for the school’s élite sportsmen]. After dinner Mr Owen [1860–1949] made his kind speech stating how glad he was to see us all again, and then speeches and songs followed thick and fast in unending succession. Last of all [Arthur Grayson] Hartley [1882–1946] made a speech proposing the health of Mr & Mrs Owen which was drunk with unceasingly renewed cheers, & we sang ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow’. We ended up with ‘God save the King’ & ‘Auld Lang Syne’, and then adjourned, the boys to their beds (as it was 11.30 and they unfortunates had school at 8 a.m. (some at 7) the next morning. I do pity them.) we to the dining room where were cigarettes whiskey etc., and a charming fire to drive away the thoughts of sleep and dispell [sic] dull care from so happy a throng. I say happy because I feel sure that no-one in that rooms [sic] had ever felt happier (in its best sense) in all their lives. ([IV] Diary 10 December 1904)

Turbutt passed Responsions in September 1901 and matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 October. We do not, however, know anything about his academic performance during his first term as he had to return home on 2 December because of illness. But apart from one term in which he was rated β, he performed satisfactorily throughout his time at Magdalen and was rated α in each of them by President (later Sir) Thomas Herbert Warren (1850–1930; President of Magdalen 1885–1928). Warren, it should, however, be stressed, seems to have awarded termly grades for being the right kind of chap with the right collegiate attitudes rather than for academic ability alone. Thus, α seems to have denoted anything from “excellent” to “acceptable”, β anything from “marginally acceptable” to “in serious risk of failing”, and γ, a rarity, “beyond hope”. Turbutt passed the First Public Examination – a paper in History – in Michaelmas Term 1902 and spent the subsequent terms reading for a Pass Degree in History with Modern Languages (Groups B1 [English History], B2 [French Language] and B5 [German Language and Literature]). He passed the Second Public examination – a second paper in History – at the end of Michaelmas Term 1903, and thanks to some hard work in March 1904 (see below), he scraped through German in Hilary Term 1904 and was able to take his BA on 20 October 1904.

Turbutt’s academic profile at Magdalen College, 1901–04, compiled by Herbert Wilson Greene et al. (MCA: F29/1/MS5/5: Notebook containing comments by H.W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895–1911], p. 53) (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College)

The most successful subject [during the Edwardian era] was Natural Science. Indeed, in the second half of the nineteenth century it was the one school [subject] to produce respectable results. […] The large majority of Magdalen’s students, even the demies [Scholars], did not excel in Schools, whatever their potential on admission.

Or to put it another way: at Magdalen under Warren – unlike at Balliol under Benjamin Jowett (1817–93; Master of Balliol 1870–93) – uninspired Humanities dons were required to administer old-fashioned syllabi to undergraduates who, to a considerable extent, lived in their own sport-centred culture, had few worries about future careers, and were able to satisfy the demands of the system by a small amount of barely adequate academic work. Moreover, at Magdalen the Humanities dons tolerated a Junior Common Room essay bank from which their tutees could borrow an ancient essay by a third party on a standard topic and read it out as their own some five minutes later. As we shall see, Turbutt was a gifted young man with scholarly potential in several areas, and being neither a drone nor a Hooray Henry, could well, with the right kind of direction, have become more than an enthusiastic amateur in an academic field that was connected with books, libraries, archives and/or architecture. So it is probably fairer to view his rather indifferent performance at Oxford as the failure of an academically stagnant college to spot the potential in a young man whose interests did not engage with conventional requirements even though he possessed the enthusiasm, intelligence, knowledge and potential that could flourish in private, among friends and mentors whose interests chimed with his own.

Because of his traditional upbringing and conservative views, Turbutt was not disposed to be critical and, as we shall see, had great affection for many aspects of Oxford. So he was not at all averse to spending a fourth year there, going through the motions of studying for a qualification in Law (Group B4 [Law]). Nevertheless, his Diary entries dealing with the years 1904–06 [IV] strongly suggest that despite Turbutt’s very real attachment to Oxford, his major interests were not typical of Magdalen’s undergraduates of the time. The Diaries display a passing interest in cricket when W.G. Grace (1848–1915) played for the Gentlemen of England against the University in the Parks ([IV] Diary 23 May 1905), a proper interest in cricket when Eton played Harrow ([IV] Diary 13 July 1906), an equally passing interest in soccer when Magdalen played Jesus in a cup tie ([IV] Diary 3 November 1904), a loyal interest in rowing when Magdalen went Head of the River ([IV] Diary 25 May 1905; see below), a polite willingness to engage in “badger digging” with “the gentlemen of the party” when he was on holiday with friends in Cornwall ([IV] Diary 9 August 1905), a hospitable interest in shooting when he was at home over the Christmas vacation, a well-bred interest in the sport when he and his family were staying with friends at Sharsted Court, near Newnham, Kent, in autumn 1905 ([IV] Diary 20–21 October 1905), and an occasional flash of enthusiasm for trout fishing ([IV] Diary 16 September 1904 and 5 June 1906). But being by nature a quiet and uncompetitive man, Turbutt tended to stand apart unobtrusively from the profanum vulgus of his contemporaries with their predilection for macho pastimes and blood sports, and he recorded a definite distaste for such “laddish” events as the noisily “debauched” Magdalen “Afters” that sometimes took place in Hall on Sunday evenings during term-time ([IV] Diary 23 October 1904).

Turbutt’s tastes and preferences can be adduced from his seven closest friends during his Oxford years: (1) Arthur Grayson [Dalison] Hartley, Harrow, Oriel College, Oxford (1901–04), future solicitor (“He is my greatest friend up here”: [IV] Diary 11 June 1904); (2) Arthur Andrew Partridge Winser (1881–1966), Academical Clerk at Magdalen (1900–04), 4th in Literae Humaniores, future clergyman; (3) Charles Frederick Pierce (1877–1936), Academical Clerk at Magdalen, future clergyman; (4) Robert Neale Menteth Bailey (1882–1917), Eton, a young man of scholarly tastes and a future Clerk to the House of Commons, who devoted most of his free time to the Working Men’s College in London, and died of wounds received in action in Palestine on 1 December 1917 (judging from what he says in his long letter of 30 May 1915 to Turbutt’s mother, he knew Ogston very well and got on well with Turbutt’s whole family); (5) Richard Godfrey Parsons (1882–1948), Demy at Magdalen (1901–05), 1st in Literae Humaniores, 1st in Theology, future clergyman who became Bishop of Southwark and Bishop of Hereford; (6) Edward Malcom Venables (1884–1957), Magdalen College School, Chorister, and Commoner at Magdalen (1903–07), 3rd in History, future clergyman; (7) Frederick Clyde Patton (1882–1958), Harrow, Balliol College, Oxford, 4th in History.

The seven young men shared a “Liberal High Church” Anglicanism, a social awareness that was, on the whole, to the right of centre, a love of music, especially church music, and, more untypically for the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, a lack of concern with sport. So they were neither “Hearties” nor “Bloods” – let alone “Hooray Henrys”. But nor were they “Aesthetes” or “Grecians” in the Wildean sense; and nor were any of them budding career academics like E.M.R. Stadler, C.H.G. Martin or L.W. Hunter, who had well-focussed interests in specialist topics very early on and while at Magdalen were already pursuing their embryonic careers via academic distinction or relevant qualifications and experience. To be more precise, Turbutt’s cast of mind and disposition – which were certainly shared by Bailey – were those of the serious gentleman antiquary, but not that of the dilettante, who had the time and money to permit his interests to range freely across several areas. Turbutt was particularly interested in architecture, especially ecclesiastical architecture, music, especially church music, drawing and sketching, and old books, especially the business of book production in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century England (see [I] Notes). His interest in this latter topic had clearly been stimulated by his father’s interest and the contents of his family’s library, for in February 1902 he gave his father a birthday present consisting of a copy of Tenures by Sir Thomas Littleton (1402–81), one of the earliest treatises – in Norman-French – on English law, and a copy of The Bishop’s Bible (1572). This, Turbutt remarked in his accompanying letter, was:

even larger than our Great Authorized version […] It is one of those which Queen Elizabeth ordered to be chained in the Cathedrals of England, and it still has the Swivel of the Chain. […] I am comparing it with the perfect Bodleian Copy, and I have pages to write on it yet before I can send it you – It appears to be a particularly interesting one as the place where the wicked Favourite Lord Leicester’s portrait ought to be is left blank in my edition, but is printed in the 1572 edition. ([I] Notes. Letter to his father of 6 February 1902)

Consequently, he was a member of Oxford’s Antiquarian Society and it was to this body that he presented a paper on early book production at its meeting in one of Magdalen’s lecture rooms on 17 February 1905.

G. M. R. Turbutt, The Grammar Hall, Front Quad, Magdalen College, Oxford, ([V] Designs and Sketches [1904-09])

(Courtesy of and copyright Gladwyn Turbutt).

When we entered the church what a surprise met our eyes! One could not imagine a more perfect piece of Norman architecture, solid, massive, yet beautiful on account of its vastness and simplicity. It seemed strange to think that in that church, which seemed so new owing to the beautiful colour of the Caen stone, William the Conqueror had walked, and now lay interred, that Archbishop Lanfranc himself had consecrated it in 1077 in the presence of the Great Conqueror.

But despite the usefulness of the French railways, Turbutt showed a distinct dislike of modernity, especially its factories, homogenized landscapes and “hideous modern art” ([II] Diary of Journeys).

At the end of the Michaelmas Term 1903, Turbutt passed two further papers (one in History and an English essay). And in March 1904, with one final paper looming at the end of the summer term (B5; German Language and Literature), Turbutt and Patton spent three weeks in Arendsee i. d. Altmark, a remote little town on the edge of the Lüneberg Heath that boasted few distractions, in order to do some intensive academic work and brush up their German. In pursuing the latter aim, Turbutt, whose former governess, Fräulein Leiter, was German, had more success than he had had in France for on 7 April 1904 he wrote to his mother that he could now say “absolutely anything I want to in German” – a skill that would prove its usefulness in a decade’s time for the interrogation of German prisoners. Since Turbutt was last on the Continent, his architectural taste had become more sophisticated, and the opinions, descriptions and judgements that are contained in his letters rely far less on generalizing adjectives such as “beautiful” and “charming” and are altogether more reasoned, knowledgeable, detailed and subtle. They evince a sure grasp of architectural terminology and, as always, are illustrated with meticulously executed and atmospheric pen-and-ink drawings. But Turbutt was also more ready to indulge in mild stereotyping than had been the case during his month in France – as his remarks on Cologne Cathedral, which he and Patton had visited en route to Arendsee, show:

Externally as well as internally, there is absolutely no originality in it. It is stolid like the German nation. […] The most beautiful thing is the Triforium which I consider perfect and of the highest art. It closely resembles the cloisters of Salisbury Cathedral. ([II] Diary of Journeys)

By the time of Finals, Turbutt was working up to 13 hours a day and allowing himself the occasional long walk or visit to the theatre. On 7 May 1904, for example, he saw A Winter’s Tale for the first time and commented: “What a treat to see something respectable at the Theatre instead of the usual Musical Comedy trash” ([IV] Diary 7 and 8 May 1904). His first paper went well: “Good Luck what an easy paper and very little subject matter. Just the Questions I had particularly prepared. I was in writing hard till 12.30.” But his second paper, “Unseens and German Literature” was harder, and his third paper was nearly disastrous:

very long German proses and [a] very unfair Grammar Paper. Questions [such] as “What influence had Luther’s Bible on the growth of the German language”. I stayed in the whole of the 3 hours, but did not do quite ¾ of the paper owing to want of time. ([IV] Diary 9 and 10 May 1904)

On 16 June Turbutt had his compulsory Viva Voce exam:

I went in at 10 o[’]clock for it, but to my horror my name was called out among those who were to stay, so I was awfully afraid that I had not done sufficient prose for them in the Exam. I was right. They set me another piece of German Prose, and I was so nervous that I thought I should never pass. It was hard. I sat down to it and racked my brains for an hour during which I heard everybody else being viva’d for good or bad. After an hour they took my unfinished prose and told me to come in again in 10 minutes. I fled back to my rooms to look up some words that I had missed in the prose. When I returned they told me that they had looked through my prose and noticed that I was careless about my punctuation which was very important in German. They then asked me whether I had read all the Literature as I seemed weak on the Romantic School. I answered that I had not done all the Romantics as I did not know that they all were included in the period. They then asked me which part of the Literature I liked best, and here I came out in shining colours as I was probably the only person who had read any of the literature besides that set for Schools. I said I preferred the Lessing period, as I felt I knew many of his works fairly well. They were very pleased at this. We then had quite an amicable, not to say amusing discussion on all Germany’s great men most of whom I was well up in, and I gave my criticism of various people. When I left (it was lecture room 2 in the New Schools), I felt a sigh of relief steal over me which was augmented to joy when at 12.30 I read my name on the list as having passed. I have now pass[ed] Smalls. Mods. Divinity. French History and German and am qualified to take my Degree. ([IV] Diary 16 May 1904)

To celebrate, Turbutt and a friend spent the afternoon by riding out to Abingdon to see Dr Paulin Martin (1842–1929),

who had, as I had heard, some nice books. I was not disappointed. He had beautiful treasures. Mathew’s. Cranmer’s – Geneva Authorised Bishops’ Bible, and many editions of each. A nice copy of the 1st Folio of Shakespeare but with the Portrait & Verses from the second, also wanting the last leaf, also 2 second folios, one third and one fourth. The 1526 (Pynson) Chaucer as the one at home, but only the Canterbury Tales part. The 1542 edition (Bonhaus [recte Bonham]), the 1561 with woodcuts and without, the 1598 (Bishop) one. Then “The Chronicles of England” printed [by Gerard Leeu] at Antwerp. 1492. – Wynkyn de Worde’s Polychronicon 1495 also Golden Legent [sic] 1498. Pynson’s Froissart (only one vol.). All the old chronicles such as Fabian. Holinshed. Lanquets. Grafton. 1st Fairie Queene of Spenser. All the first 5 editions of Isaac Walton’s Angler except the 3rd. A Shakespeare Quarto (Romeo & Juliet 163r.) The 1st Prayer book of Ed[ward] VI [1549]. Early missals. And countless other treasures all of inestimable value. There were only about 400 to 500 books in the Library but all plums and collected by himself. I am informing him about several facts about his books that he did not know. I did not have time to see half his treasures but he has invited me over to come and see some more.

There is a great row on in College this evening, probably because Schools [Finals] are over for most people. I think I shall have no difficulty in getting leave to stay on for another year at Oxford now as father wishes it, and I have passed Schools, so the Dons will not object I think. ([IV] Diary 16 May 1904 [loose leaves])

The end of term passed off well, with dinners, parties, outings, tickets for the Trinity Ball (“about 500 people, not very select” ([IV] Diary 21 May 1904 [loose leaves]) and Encaenia, where Turbutt saw Marconi receive an honorary degree. On 2 June, Turbutt received

a most insulting note from Slatter & Rose stationers High Street saying that unless I paid a bill, which I had incurred last term, by Friday they would summons me. This is what Oxford tradespeople do. When one is in ones 3rd year they are so afraid of ones going down that they are a perpetual nuisance. ([IV] Diary 2 June 1904 [loose leaves])

On the same day Turbutt met the Reverend Henry Austin Wilson (1854–1927; Fellow 1876–1927), Magdalen’s Fellow Librarian,

and asked him whether he had read the article in the Bibliographical Transactions on Early Latin Grammars. Magdalen School & College produced no less than 5, after the Garlandia. [John] Anwykyll. [John] Stanbridge. [John] Holt. [Thomas] Wolsey and [John] Collet [sic]. I suggested that the Library should get a copy of the Publication. Till recently the only old grammars of this kind that the College possessed were knocking about in the Boys library at the School!!! ([IV] Diary 2 June 1904 [loose leaves])

While it is true that the first three men named by Turbutt were all connected with Magdalen School and/or College in the last two decades of the fifteenth century and produced grammars, the Christian Humanist John Colet (1467–1519; Dean of St Paul’s 1505–19), who took his MA from Magdalen in 1590, did not. Neither did Wolsey, who was a Fellow of Magdalen from c.1497 to c.1502, even if, later on in his career, he did become interested in the standardization of school textbooks.

On 13 September 1904, Turbutt and his father, who were very close to one another, set off for a fortnight’s trip to Scotland and the Orkney Islands. Their first stop was Edinburgh, where a friend showed them round the major city sights and the University: “Their arrangements are considerably better than ours and they have fine billiard[,] debating and reading rooms. The one point in which we score over them is in our library” ([III] Diary [14 September] 1904). On 15 September they travelled to Forres and then, on 17 September, to Thurso. Two days later they crossed to the Orkney Islands, where they spent the rest of their holiday visiting the islands’ antiquities. They started their return journey on about 22 September, reached Edinburgh on 24 September, and on the following day worshipped at the English Cathedral,

where we had a charming service, with very fair singing. Of course not quite up to Magdalen standard, but nevertheless, very good. The hymn ‘Far from my heavenly home’ was most beautifully sung, as indeed it requires. It is almost wickedness to let a village choir try to sing it. In the afternoon we went to the service there again and had services of Barnby in F and one of Goss’s Anthems. In the evening we went to service at St Gyles, and a very painful proceeding it was. People lounging about in a most irreverent manner. St Gyles has the most beautiful bells that I have ever heard, and as far as the building goes it is very good, except that it has one transept filled up with a huge and ugly organ and abominable choir stalls, and the other transept is ruined by a large erection called a porch.

But once back home, Turbutt adjudged the trip to have been “quite delightful and free from practically all the numerous little inconveniences and unpleasantness which usually attend such impromptu trips” ([III] Diary [26 September] 1904).

After he agreed to take his BA at once, on 20 October 1904, Magdalen’s Tutorial Board allowed Turbutt to stay up for a further year and study Law, a subject that would have been of some relevance for a future member of the Derbyshire Bench ([IV] Diary 7 July 1906). But his Diaries suggest that his heart was not primarily in his studies, even if he began by trying to get his head around the Law of Contracts in Michaelmas Term 1904. But he did not fret too much if the room assigned for the lecture was too full for him to get into, as happened quite often at the start of term. And although at the end of the term he dutifully passed Group B4 of the Pass School in Law (the English Law of Contracts), he sat no more exams.

Nevertheless, Turbutt’s two final terms at Oxford were not wasted and he settled down to enjoy the city’s aesthetic and cultural life to the full, something that rural Derbyshire, for all its delights, could not offer to anything like the same extent. At the centre of Turbutt’s life during his fourth year were the city’s musical events, ranging from public concerts through church liturgy to the Scouts Concert ([IV] Diary 10 November 1904) with P.V.M. Benecke (1868–1944), Magdalen’s shy and polymath Tutor in Ancient History (Fellow 1891–1944) tinkling the ivories, and from Gilbert and Sullivan ([IV] Diary 8/9 May 1905) to more of those private “musical soirées” with friends that had been such “a great abstraction from work” in the previous terms ([IV] Diary 14 October 1904). On 4 February 1905 he was even persuaded to go and hear Sousa’s band, which he adjudged “very entertaining”, “a wonderful band” with a “superb” saxophonist and drummer – a very surprising judgement from someone whose tastes inclined to the conservative and classical. Turbutt also decided to take piano lessons and singing lessons from Dr John Varley Roberts (1841–1920), the prolific composer of church music and Magdalen’s unstoppable, larger-than-life organist and Informator choristarum (1882–1918), and profited greatly from their growing friendship. Dr Roberts, it should be stressed, was a masterly Informator and President Warren’s notebooks contain some newspaper cuttings from November 1899 which report on a visit made by an American organist, Dr Miles Farrow (1871–1953), to various choirs all over England. He considered Magdalen’s choir “the finest […] in England to-day” and gave his reasons for saying so as follows:

There are in this choir sixteen boys and ten men, two daily services, and of course, daily rehearsals for the boys who attend the choir-school. The golden rule of Dr Roberts is to “cultivate soft singing” and “strengthen the head voice.” Never does he allow the least forcing or pushing of the voice, and the consequence is that the quality is the most beautiful that can be imagined, and the music is unaccompanied. Pitch is maintained absolutely. Not once could I detect the least tendency towards flatting [sic] and they sing sometimes whole services without the organ.

Moreover, although he was already an accomplished draftsman, Turbutt also went for drawing lessons with Alexander Macfarlane (c.1839–1921), Oxford’s first Ruskin Master of Drawing (1871–1922). To these new pleasures, one must add the late-night conversations in friends’ rooms or in his own new set of rooms in 5 Long Wall Street, inter-collegial dining with large, well-cooked meals that in those days could be brought to students’ rooms, and more modest opportunities for quiet good fellowship over fruit and coffee such as the evening that he and his friends enjoyed on Sunday 23 October 1904:

Had Venables in to Breakfast. Went to Lunch with Patton, & dinner at Buols Restaurant [at 21 Cornmarket, now defunct]. Had my usual soirée in the evening, consisting to [sic] Pierce, Bailey, Parsons, Venables, a sort of standing invitation, and we talk and eat fruit, and drink coffee etc. and some of us go to the University sermon or Balliol Concert, but none of us to the debauched Magdalen “After”.

It was almost certainly Magdalen’s architecture that had attracted Turbutt in the first place, but once there, he discovered a variety of less obvious inter-collegiate subcultures and was exposed to a range of new, unexpected, sensory experiences, which he began to enjoy with greater consciousness and appreciation. After walking through Oxford on two evenings around Guy Fawkes Day 1904 he noted, for example: “At 11 p.m. I walked up the High Street to post a letter & the effect of light was beautiful. The whole of St Mary’s & the Camera was light [sic] by a magnificent bonfire in B.N.C. Quad […], and the air was full of rockets with coloured stars”, and: “The whole of Oxford is a perfect glow. Every College has its bonfire and fireworks. Magdalen looks lovely. The Town and buildings are lit up red with the glow of the bonfire in St Swithun’s Quad.”

As a graduate, Turbutt was vouchsafed more extensive insights into the lives of the Senior Members of the College, and he has left us a fascinating account of eating dinner on Magdalen’s High Table ([IV] Diary 9 November 1904):

In the evening I dressed then went to the Chapel Service. We had Goss’ Wilderness [Sir John Goss (1800–80), The Wilderness (1862)]. In the evening I dined with the Bursar P.V.M. Benecke, at the High Table in Magdalen. At 7 p.m. I went into the Senior Common Room and when we had all collected there we went into Hall (in order of seniority of Fellows), I being taken by Mr Benecke my host. Mr Cowley, the Vice[-]President, was presiding and said grace after which we all sat down, and then the Undergrads came in. Wine was immediately handed round, and we drank to one another in the accustomed way – i.e. my host drank with me first, and then various Fellows during the course of the meal drank with me – i.e. Mr Greene, Mr Brightmann, Mr Dunn Pattison [killed in action in Mesopotamia on 8 March 1916], Mr Webb, Mr Godley – and the Vice-President sent round word that he wished to drink with me. The dinner consisted of soup, fish, joint, pheasant, sweet, biscuits etc. After we had finished we all retired to the Senior Common Room where wine & dessert were waiting. We all sat down around the room at little tables, and, as the custom goes, the two junior fellows, i.e. Mr Brightman [the Dean of Divinity] & Walter Raleigh [the Professor of English Literature], handed round the dessert.

The Magdalen Fellowship (1906): Benecke is fifth from the right in the back row; Cowley is fourth from the right in the back row; Webb is third from the right in the back row; Varley Roberts is on the extreme left of the front row; Frank Edward Brightman is fourth from the left of the front row; President Warren is in the very middle of the front row; Godley is second from the right of the front row and Herbert Wilson Greene is on the extreme right of the front row (Courtesy of Magdalen College Oxford)

Sir Walter Raleigh (second from right) at an Oxford Volunteer Corps parade; Robert Bridges (1844–1930), the Poet Laureate, is third from right (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Among the curious customs of ancient standing is one that nobody may get up without the permission of the President, Vice-President, or in the case of neither being present, the Senior Fellow’s permission, so the V[ice-]President was frequently called upon to give permission to ring the bell etc. After a time we retired to the Smoking Room where coffee, cigars, cigarettes were served. Here we remained till I bade my host goodnight at 10.45: He shewed [sic] me all the pictures by Buckler and all the designs of our new roof in the Hall. He also explained to me how that Bodley had wished to put up a roof with geometrical tracery, but that he had been made to alter it when the proofs of perpendicular tracery were found under the plaster. I was weighed among other things, and found myself only 10 stone exactly which disappointed me as I used to be much more. The Oxford air apparently does not agree with me.

Nevertheless, on his third day back at Oxford in the Hilary Term, after an idyllic Christmas vacation in Derbyshire which, with its low-key shooting parties, snow-covered landscapes, tobogganing, skating, dances, family gatherings, church attendance and local social events recalls Jane Austen’s Longbourn and Dickens’s Dingley Dell, Turbutt woke up with the thought: “Few things have given me greater joy in my life than to wake up the first morning of term and find myself in Oxford. It is one of the most charming places in the world, and I shall never forget the delightful time I spent there as an undergraduate” ([IV] Diary 22 January 1905).

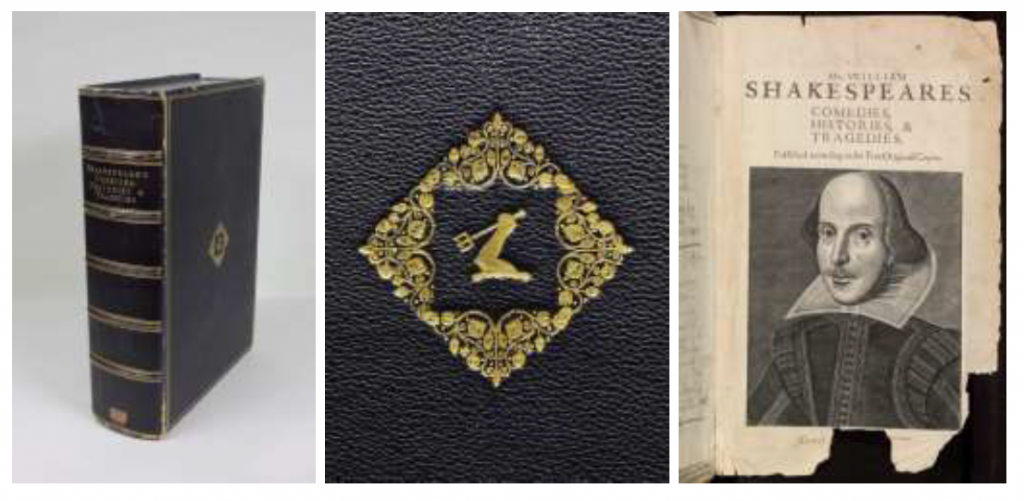

Although, at the start of Hilary Term 1905, Turbutt had resigned himself to eight weeks of unexciting but necessary work on the Law of Tort, that expectation was disrupted by his bibliophilia. By early 1902, young Turbutt, whom President Warren would describe posthumously as being of “studious and book-loving tastes”, had been using the Bodleian’s holdings to make careful comparisons of early editions of the Bible, and by summer 1904 he possessed an impressive knowledge of early printed books and a developed interest in bibliography. By 1905 he was wont to bring down early printed books from his family’s library in order to compare them with editions in the Bodleian. In c.1750, Richard Turbutt (1689–1758), Turbutt’s great-great-great-grandfather, had purchased a seventeenth-century folio edition of the collected plays of William Shakespeare, which remained in his family’s possession until the early twentieth century. On 23 January 1905, according to his Diary [IV], Turbutt took his family’s battered Shakespeare with its damaged title page into the Bodleian to get it dated more accurately by the bibliographer Falconer Madan (1851–1935; Bodley’s Librarian 1912–19) and obtain some advice about its restoration. Madan immediately consulted his younger colleague, Strickland Gibson (1877–1958), then an assistant librarian, and the two experts realized that they were dealing with “one of the most interesting bibliographical finds ever made”, for they had realized that Turbutt’s book was not just an early edition but a First Folio – i.e. the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, which appeared in a large folio edition in November 1623, seven years after his death. The First Folio contains 36 plays, 18 of which had never appeared in print before and which would have been lost but for the edition.

Although the title page of the copy was damaged and lacked a date, Gibson and Madan managed to prove that it was a First Folio, and, more importantly, that it was the Bodleian’s long-lost copy. The copy is assumed to have been sent there under an agreement between Sir Thomas Bodley (1545–1613) and the London Stationers’ Company that required a copy of every new book published in England and registered at Stationers’ Hall, London, to be sent to Oxford’s Library. Moreover, Turbutt’s copy is the only extant copy that is known to have entered a library on publication, and its patterns of wear demonstrate which plays were most often read by its early readers. The Turbutts’ copy appears to have been sold by the Bodleian as a duplicate after it had received a copy of the second issue of the Third Folio (1663–64). Although this contained seven additional plays, only one, Pericles, turned out to have been written by Shakespeare. By 1674, the First Folio had disappeared from the Bodleian’s catalogue, and well before the turn of the nineteenth-to-twentieth century it was assumed that this copy had been irretrievably lost, possibly, like the Stationers’ Hall’s original copy, during the Great Fire of London (1666).

The crucial evidence for the veracity of Madan’s and Strickland’s discovery was the printed waste that was used for the end-leaves of the binding. It matched the waste used for the end-leaves of three other books that were sent for binding with the First Folio and identified from the Library’s accounts as those that were sent to the Oxford master binder William Wildgoose on 17 February 1624. Further evidence was provided by the realization that the Turbutts’ First Folio had been “bound in identically the same fashion with the marks of the chain in the same place” ([IV] Diary 23 January 1905). It is now believed that the Turbutt First Folio is the most distinguished in the world because of its original binding from 1624, the presence of all the text leaves, and a most remarkable provenance. Indeed, the volume is held in such esteem that the Bodleian very rarely allows anyone even to touch it.

From left to right: the Turbutt Shakespeare (Photo courtesy of Mr Andrew Honey and the Bodleian Library); the Turbutt crest on the Turbutt Shakespeare (Photo courtesy of Mr Andrew Honey and the Bodleian Library); the title-page of the Turbutt Shakespeare (Copied from http://firstfolio.bodleian.ox.ac.uk).

Turbutt’s Diary then continues, incredulously:

That such a treasure could exist was beyond belief, and that it should once more revisit the walls of its former home was equally curious. […] Mr Madan’s advice was to have nothing done to it except to have a Morocco case made for it, as so many copies were tampered with & one could have no proof of their genuineness.

The find caused considerable excitement in the Bodleian and on 2 February 1905 Madan drafted a letter for publication in the Athenaeum. A week later Turbutt’s father gave permission for the draft to be sent, and after some more research had been completed, the Turbutts’ First Folio was exhibited at the Bibliographical Society, 20 Hanover Square, London W1, on 20 February. On the following day, a report on the event appeared in The Times with which Turbutt was not happy: “It was very bad, and all the names were wrong” ([IV] Diary 21 February 1905). Reports subsequently appeared in The Westminster Gazette and The Star which pleased him even less. But on 24 February Turbutt commissioned the blue case proposed by Madan, and on 1 March he spent much of the day at the Bodleian, “trying to draw conclusions about 1st folios of Shakespeare like an idiot as though enough was not already known about them under all conscience”. So apart from spotting a couple of “peculiarities” that puzzled him, he did not get very far. Although these did not prove to be important, his efforts added to our understanding of the contemporary reception of the First Folio, as Madan pointed out:

This copy adds a definite original contribution to Shakespearian criticism, from a consideration of the comparative wear and tear of the various plays, caused – and this is the point – not by an individual owner but by successive readers in a public library. Mr G.M.R. Turbutt, who suggested this line of inquiry, has carefully examined more than once every leaf of the volume.

Then, on 5 March 1905, President Warren invited Turbutt to show the Folio to Viscount Goschen (1831–1907), Chancellor of the University of Oxford from 1903 to 1907, who was coming to Oxford that day especially to see the book. Turbutt duly put the Folio on display after dinner and recorded in his Diary that it aroused a lot of interest “and I got the various people to sign their names to the list of people who had inspected the volume since it had been on show in the Bodleian”. Then, on the afternoon of 10 March, Robert Theodore Gunther (1869–1940), Magdalen’s Scientific Fellow and the founder of Oxford’s Museum of Science (1926–30), showed Turbutt round the Clarendon Press and introduced him to the University Printer (or Comptroller), Horace Hart (1840–1916), “a genial middle aged short man with a whitish beard and gold specs, very full of conversation”, who showed him round the Press. Turbutt expressed himself “glad to make his acquaintance as he had helped me so much in the information about the Shakespeare, & certainly had contributed a lot towards the knowledge of the Types”. Despite his dislike of the modern, Turbutt was extremely impressed by “the ‘Monotype’”:

a machine which made the type out of molten lead as it went on; a truly wonderful invention, quite new & direct from America. They had two such machines. Another very interesting machine was the one which folded the quires, & also one which sewed them. I was also very much taken with the Collotype room, & the apparatus for the electrotype, all very wonderful. What would Gutenberg & Fust & Schoeffer [early printers] have thought had they been taken round? ([IV] Diary 10 March 1905)

Eight days later, after a detour to inspect the British Museum’s First Folios, Turbutt and his parents set off on a three-week-long journey, mainly by train, that would take them via Calais to Paris, Lyons, Avignon, Arles, Marseilles, Genoa, Milan, Como, Lucerne, the St Gotthard Tunnel, Strasbourg, Paris and Calais. They greatly enjoyed the tour, especially the Papal Palace at Avignon, the Roman amphitheatre at Arles, the sub-tropical environment around Cannes, the palaces at Genoa, and the Alpine scenery in general. Turbutt arrived back in Oxford on 9 April, in the middle of the Easter vacation, and commented: “Oxford seems very funny when the University is down. Not a soul stirring in the Colleges. Mr Brightman is the only Magdalen Don up. Nobody else in College, no Chapel services – nothing. – Everything as quiet as death in the evening.” Ten years later many other visitors to Magdalen, whether in or out of term, would have such spectral experiences, but for reasons that were much more tragic.

For Turbutt, the Trinity Term of 1905 was a mélange of trials and delights, but he had clearly decided to enjoy the latter despite having to wrestle with Torts for a second term, and on 1 May, after ascending Magdalen’s tower to welcome in the dawn to the accompaniment of the College Choir, he left us yet another affectionate account of a custom that continues until this day:

It is customary for undergraduates of Magdalen College if not too lazy to ascend the Great Tower to see the sun rise on May morning at least once during the course of their residence. Many of course there are who scoff at the idea but probably repent it later. Neither my friends nor I however rank among such, and far from scoffing at the old custom, as each year has come round we have got up at 4 a.m., ascended the tower at 4.30 and seen (or not seen as the case may be) the sun rise and heard the Hymn or College Grace which is sung on the top by the Choir. The whole scene is most impressive and those who will take the little trouble of an early rise [will be] well repaid. The Choir [are] in su[r]plices and the undergraduates and Dons in academical costume (cap & gown). The number of other people who are up on the Tower is comparatively few owing to the scarcity of the Tickets to be had, but looking down below the whole of the Magdalen Bridge is crowded with people who come to hear the ceremony, such is the enthusiasm of the Oxford Town. Today the weather was unsettled. Yesterday had brought with it incessant thundershowers and in the night the wind had got up. At 4 am, when I rose, it was blowing a gale, I however dressed and went round to the College to get in before the ticketed town who were admitted at half-past. I felt very much honoured as I had received a special invitation from Dr Varley Roberts to partake of the breakfast which he gave in the College Hall at 5.45 to the choristers[,] dons & undergraduates whom he had invited (the latter class being limited to about ½ doz., and the dons and chaplains amounting to about the same number). On the top of the Tower our robes were gaily blown about by the winds and we had a few spots of rain, but otherwise the weather was not inclement, and while the hymn was being sung the sun shone forth in all his glory. At 5.45 I went to the College Hall where there was a very festive gathering. Dr Varley Roberts our host was the leading feature. Of dons there were Mr Benecke, Webb, Pickard-Cambridge, Cowley. The Chaplains were Revs Blockley, Negus and Myers. Undergraduates: Pierce, Winser, Patheram (the 3 Academical Clerks), Gambier-Parry, Venable[s], and myself. Then there were the 16 choristers and 2 or 3 guests (not belonging to the College) of the Doctor’s. We had a delicious and much wanted breakfast of Coffee, Tea, Cold chicken & ham, Tongue, Toast, bread, butter, jam etc. At about 6.45 we adjourned and those who wished to smoke accompanied the Doctor to Pierce’s rooms, but I went away as I had a train to catch later on in the morning.

The train took Turbutt and his friend Bailey to Ascott-under-Wychwood, where they began a 10-hour circular walk around Oxfordshire and the Cotswolds, during which they visited places of interest and covered 30–40 miles. Such expeditions, or their equivalent on bicycles during which Turbutt and his friends must have covered at least double that distance ([IV] Diary 6 May 1905), became a regular feature of Turbutt’s life and they paid dividends eight years later in the Army, where route marches in full kit alongside arms drill, musketry and trench-digging formed the greater part of basic training.

Eights Week fell in late May, and in the late afternoon of Wednesday 31 May 1905, Turbutt, Parsons, and two ladies hired a punt to watch the last part of the rowing races. Turbutt’s Diary contains what is probably the only surviving account of a train of events that began innocently enough but ended in what most people nowadays would consider unacceptable, not to say shocking, behaviour on the part of educated young men. It begins:

Oh! What an anxious moment! We had already cut the hay in the field in the middle of Addison’s Walks “on spec”, thinking that we should remain Head, but that was a secret. How ignominious it would have been had we lost just on the last night when we had everything ready for our rejoicings. We moored our boat in a good position commanding a view of the Gut [the slightly narrower part of the River Isis with a twist in it about half-way along the Bumps course] and Finish and anxiously awaited the result. At last the gun fired and the race commenced. By the green bank we were leading by nearly a length, and at the end we finished in great style having pulled up considerably and run away from the boat behind. We are Head of the River once more, and have honoured our unique reputation of having been among the first 3 boats on the river for over 25 years. We also hold the record for being Head of the River. When the races were over we punted back to Magdalen and bade farewell to the 2 ladies. At 8 pm the Bump Supper was to take place. We all changed into oldish clothes as we knew what it would mean. There was a band in the Minstrels’ Gallery and they played during the supper. Champagne was provided in unlimited amounts and soon the dinner changed from hilarity to debauchery. Bread corks wine glasses bottles and plates were thrown about the room and there was not a square foot of floor without some broken glass on it. The President, The Dean (Mr Cookson), the Vice-President & Mr Greene were the only Dons present. When the supper was over and everybody had drunk to everybody else innumerable times the President rose & amid roars of applause proposed the health of the King which was drunk with musical honours which were drowned by discordant vociferations of 200 tongues which could not keep quiet. The President then made a speech not one word of which I could hear owing to the noise. The healths and speeches followed one another. Morrell (Captain of boat) [Wolwyche-]Whitmore (President of J.C.R.) [Wilson-]Evans (Captain of University College boat) and many others spoke, and finally an old Magdalen Member. By the end everybody practically had thrown his wine glass on to the floor, and the whole Hall echoed with the noise of breakage. Thus ended the most debauched supper that I have ever been at.

This was the first part of the evening’s entertainment. Next followed the Bonfire which had been built up in the field about 15 feet high. A wooden bridge had been built from the Walks to the field and we all crossed over letting off innumerable fireworks which had been provided in the Cloisters. The President, fulfilling his task admirably, and gently smiling at the coarse jokes and tottering gait of drunken undergrads, lit the bonfire himself which burned up magnificently. He and the Dons stood amid squibs and crackers exploding on every side and watched it for a short time and then retired. When the bonfire was getting low a thing was done which seemed to me the most extraordinary and absurd of the whole evening. As though it was some heathen orgie [sic], two eights boats were solemnly drawn up the river & through the meadow and thrown on to the bonfire. A most amazing waste, considering that the boats cost so much to build. At 12 pm. I retired to my rooms in a most filthy state. The bridge (wooden) across to the field had been burned when fuel was short so we had a dirty muddy bank & a ditch to jump to get back. I jumped it but failing to get a footing in the very slippery & steep bank I slipped back into the ditch, and was covered in mud and water. Two rather severe calamities occurred besides the usual events such as “debagging” unpopular members of the College and burning their trousers. One unfortunate man – [Ingram Ilbert] Owen [1885–1973] – had his rooms completely wrecked. Not a pane of glass left in the windows and not a stick of furniture left unbroken in his room: all his books destroyed & thrown everywhere. Some of the better fellows of the College tried to stop it, but to no avail. [The experience, which is recounted at much greater length in the book on Turbutt (pp. 61–5), had a shattering effect on Owen’s career at Magdalen and, possibly, a very negative effect on the rest of his life.] The other was that in the Hall Murray [probably John (“Jack”) Murray (1884–1967)] had his face by his eye cut by someone who threw a wine glass with considerable force at it. Winser took a loaded revolver from one man – Glover – a wretched man who was horribly drunk [Harold Matthew (later Sir Harold) Glover (1885–1961) got a double first and had a distinguished career in the Indian Forest Service, rising to the Chief Conservator of Forests in the Punjab (1939–43)]. Thus ended an evening which, to say the least of it, was an amusing experience. It was the first Bump Supper strange to say that we had had for the whole four years I had been up. ([IV] Diary 31 May 1905)

A contemporary wooden bridge from Addisons’ Walk to the Meadow

(courtesy and copyright Professor John Gregg)

There is an eerie sense in which the fires, the violence, the noise and the wanton waste prefigured events that were still eight years away, and Turbutt’s account gives us a surprisingly frank, not to say brutal, insight into the psychological resources that would permit well-educated English gentlemen to fight as fiercely as they purportedly did.

In about May 1905, Madan suggested to Turbutt that they and Gibson should produce an illustrated monograph about the Folio. It would be published by the Clarendon Press and sold by subscription, and Turbutt would contribute an essay on the Folio’s history 1700–1900 (see [IV] Diary 3 May, 24 May and 30 May 1905). The plan came to fruition and proofs were ready for inspection in the Bodleian on Bank Holiday Monday, 12 June. Rather ingenuously, given what had been thrown around and smashed during the rout in Magdalen ten days previously, Turbutt noted in his Diary: “The Library was very crowded owing to its being Bank Holiday, and the whole of Oxford was very vulgarised, but one has to put up with such things sometimes, and we can but trust that the people derive some sort of pleasure from throwing things & orange peel about” ([IV] Diary 12 June 1905). Turbutt’s reputation spread, and on 13 June he was invited out to Begbroke to have tea with Herbert Arthur Evans (1846–1923), the editor of the quarto facsimiles of Shakespeare’s plays, who had tutored Turbutt during the month before he matriculated. Turbutt noted:

We had a long conversation on valuable editions, and he showed me many of his books some of which were very fine as 1st editions of Ben Jonson, & Beaumont & Fletcher, but most of them wanting some portion of the Preliminary or of the text. His perfect copies he has unfortunately been compelled to sell, for want of money, & then I sympathized very much with him as I had been forced to do the same on several occasions & could only afford to keep the inferior editions of my rare books, but after all they are better than nothing and if they are produced during the author’s life-time and are corrected by himself there is a lot of interest attached to them. I met a niece of his there who also apparently took a certain amount of interest in such a mad hobby as bibliography & literature.

On 15 June Turbutt gave a “Leaving Supper” for some of his Magdalen friends and Dr Varley Roberts: “We had a most pleasant evening and were well sustained by conversation and Music. Venables, Winser & Pierce & myself sang and the Doctor played the piano. It is a sad thought [that] this is the last dinner of its kind that I shall have at Oxford” ([IV] Diary, 15 June 1905). On 26 June he attended the Magdalen Ball with Rachel Venables, his friend’s sister, and on 28 June he sang madrigals in the evening concert in the Hall. The next day he awoke feeling very sad,

thinking that it was the last service that I should ever hear at Magdalen as a member of the College in the sense of being resident. This was in short my last day of Oxford life; a life which for four years had been the most delightful imaginable. I had had everything that I wanted and had so far never had to deal with the stern reality of life which is bound to come to everyone sooner or later.

But Turbutt subsequently came back for a few days to finish packing, and when he had finally said his good-byes, “especially [to] Dr Roberts who was one of my best friends”, he noted:

Farewell to Oxford!!! It was a very sad moment when the train rolled out of Oxford and I bade farewell to my University life for ever. I had spent four of the happiest years of my life there, but now, instead of [the] joys of college, the stern reality of life lay before me, and the delightful surroundings of Magdalen were to be transmuted to those of an office in Westminster. But every good thing must as a rule come to an end sooner or later and I thank my God that he has given me so many happy years which I have spent for better or for worse, as he only knows. ([IV] Diary 11 July 1905)

Turbutt was, however, soon back at Magdalen, attending the Gaudy on 22 July. He arrived the previous day, and “after supper Winser, Pierce & myself went out in a punt on the Cherwell by moonlight, & had to climb over the gates into Addison’s Walks on the way back as of course we were locked out”. At 11 a.m. the following morning,

we all assembled in Hall to make a presentation to Dr Varley Roberts for his services to the College during the past 24 years. Just certain of his friends had subscribed, and they [consisted] chiefly of Choristers; but there were one or two others besides like myself. The President was there with Mrs Warren, & Dr & Mrs Varley Roberts came. The President made a speech eulogising the various merits of the Doctor and then the senior chorister and the second presented the gifts. There was an illuminated address with the names of the subscribers on it. (It was painted by one of the Lay Clerks – John Kay –). There was also a beautiful silver salver with the following [Latin] inscription on it. […] There was also a cheque of between £60 – £70. Mr Brightman & Mr Macray among others also made speeches, and the Doctor made a long speech of thanks at the end. The whole ceremony lasted about 1 hour.

Magdalen College Choir (1907); Dr Varley Roberts is the large man with a beard and a black bow tie who is sitting on the left of President Warren. The boy with the prominent parting on the left side of his head who is standing third from the right in the third row is David Ivor Davies (1893–1951); in 1913 he changed his surname to Novello. As Ivor Novello, Davies became a song writer and star of the stage, and later still a film actor and script-writer, who made no secret of his homosexuality; his best-remembered creations are probably the song ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’ (1914), which became immensely popular during World War One, and the classic one-liner of the silver screen: “Me Tarzan, you Jane.” Third row: second from left Dennis Henry Webb; third from right John Fox Russell. Front row: second from right John Clement Callender; sixth from right Herbert Brereton; seventh from right Charles Eric Hemmerde. (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College School)

In the evening the Gaudy took place:

At 7 pm we all assembled outside the Hall and at about 7.15 proceeded to take our places which had all been previously arranged for us and indicated to each of us by means of a chart. I had been placed at the choir table, and I knew every member of the choir well, and they were special friends. In the centre of the High Table was the President with a large bowl of white lilies and red geraniums in front of him, which are the Magdalen colours. The rest of the high table was decorated with pink carnations, while the other tables were arranged with sweet peas and red and yellow daisies. In the middle of the dinner Pickard-Cambridge, the youngest Fellow of the College, delivered a Latin oration commemorating all the events which had taken place during the last year and which were of interest to the College. There was also a printed list of them, and I was much surprised to see that our Shakespeare was mentioned. After the sweets, the whole choir, boys and men, all of whom are of course present at the dinner, sang the College Grace which was simply too beautiful for words to express. A sense of reverence came over the whole dinner when it commenced, and when it ended nobody could speak for a few seconds. It is indeed one of the things which every Magdalen man must be proud of. At this stage of the dinner the boys left, and dessert was handed round, also cigars and coffee and wines – and the speeches began. The President. The President of Corpus [Thomas Case (1844–1925)]. The Rev. Canon [Edward Russell] Bernard [(1842–1921)]. Mr J[ohn] A[ndrew] Hamilton [1859–1934; from 1927 the 1st (and only) Viscount Sumner of Ibstone] and the Vice[-]President were amongst those to speak – and they all spoke excellently; each one sharpening his wits against the other speeches. At 10.30 or 11 we were adjourned to the Junior Common Room where we smoked and heard glees and songs, the former of which the choir had indulged in, in Hall also, and cheered the company with excellently sung madrigals. After 12 pm people gradually began to disperse and I with Pierce & the Senior Proctor [C.C.J. Webb] left at 1.30, we three being the last people left in the room.

Turbutt spent most of the summer and autumn enjoying himself and the local society at home in Derbyshire or with friends down in Cornwall. Among other things he sorted through his personal papers “before going up finally to town” and noted in his Diary on 16 October 1905:

It is impossible to imagine how much amusement can be extracted out of old letters etc. Many I had to burn as being too personal or private to keep but they caused a great deal of amusement. Many of the papers connected with Magdalen I kept out of association with those 4 happy years of Oxford life. They were unsurpassable for pleasure in spite of one or two little clouds, and the sight of any paper which throws light on any of the events thrills me in a way that nothing else does, so I refused to destroy them.

But two days before Turbutt’s departure for London, his Diary records that at about 3 p.m.,

we [the family] were very much surprised by a ring at the front door bell, and in came a dark little man with a hooked nose and unpleasant expression. On being asked his purpose he stated that he had called to inquire whether there was any chance of buying the First Folio of Shakespeare. He had been sent by Sotheran & Co [the oldest firm of booksellers in the world, established in York in 1761, now at 2–5 Sackville Street, Piccadilly, London] all the way from London on this errand, as Sotheran had written 3 days before and we had not answered the letter. This little man asked to have 5 minutes conversation with Father, but Father, seeing that he had come rather to spy out the land, said that if it was about the book, it was unnecessary as he had no intention of parting with the volume; shewing [sic] that Jews and Americans cannot get everything they wanted provided they pay enough. The little man was quite baffled & with an oily farewell quitted the establishment: what a funny tale he will have to tell Sotheran when he returns. ([IV] Diary 17 October 1905)

Although Turbutt’s Diary says nothing more on the matter for the next six months, Sotherans were already acting, strictly anonymously, on behalf of Henry Clay Folger (1857–1930), an American oil tycoon and collector of Shakespeareana, for later on in the same month and still without betraying his identity, he offered the Turbutts via Sotherans the huge sum of £3,000 (£236,000 in today’s money) for their First Folio so that he could add it to his already large collection of First Folios. The Turbutts needed the money and were clearly tempted by the offer, but gave first refusal to Oxford if the same sum could be raised by 31 March 1906. As the Bodleian had no funds for purchases of this order – the most it had ever paid for a book was £220 10s. (c.£9,000 in today’s money) for a volume of Anglo-Saxon and early English charters, the Library’s Curators authorized a low-key appeal for funds and there matters rested for six months.

Given Turbutt’s interests, it was entirely logical that after leaving Oxford, he should be apprenticed to study architecture in London with Edward Prioleau Warren (1856–1937), the younger brother of Magdalen’s President, who lived at that time at 18 Cowley Street, London SW1, i.e. not far from Westminster Abbey. Turbutt’s post-Elysian life had begun on Saturday 17 June 1905, when he went out by tram to Cholsey, then in Berkshire, now in south Oxfordshire, where Warren had just built himself a new house [Breache House] and taken up residence there on the previous day. Four months later, on 23 October 1905, Turbutt moved into his new rooms in 28 Albion Stret, Hyde Park, London W2, and five days after that he and his father went to his future office “in 20, Cowley St where I am to learn architecture”:

After a short interview with Mr Warren, […] my father left me […] I was given the plans sections & elevations of a cottage built for Mr Bennett at Dorchester to begin on; needless to say, the task – though requiring care – was not very difficult. I had to correct the plans to a scale of ⅛ inch to the foot. […] At 5 p.m. the office work was done so I returned to my rooms. ([IV] Diary 30 October 1905)

Turbutt was neither lonely nor completely cut off from Oxford, for his friend Hartley and his sister lived just opposite him; he soon bumped into Frederick Patton; and other friends called or came to stay. At 5 p.m. on 31 October he went to tea at the Deanery, Westminster, with his Magdalen friend, Richard Godfrey Parsons, who was studying theology as a lay student for a year with the Dean of Westminster. Dr Joseph Armitage Robinson (1858–1933; Dean 1902–11) had formerly been the Norris Hulse Professor of Divinity at Cambridge (1893–99) and his scholarly expertise in Patristics had earned him several honorary doctorates, including two at the Universities of Göttingen (1893) and Halle (1894). Parsons:

showed me all over the Deanery which is delightful & most interesting. He also showed me the Jerusalem and Jericho rooms and the Hall used as a Dining Hall for the Westminster boys: also all sorts of little secret passages & ways from the Deanery into the Abbey, and to crown everything, the Abbey by moonlight. The effect inside was most beautiful. We also walked all along the roofs of the Cloisters from which we got a lovely view. He is indeed fortunate to have such a delightful place in London to live in, and nobody could ever forget it. It was a sad moment when I said goodbye to him and returned to my rooms. ([IV] Diary, 31 October 1905)

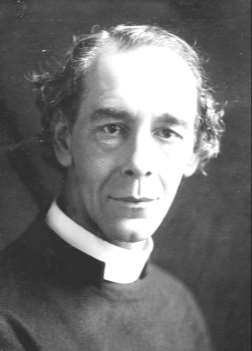

Dr Joseph Armitage Robinson (Courtesy of Miss Christine Reynolds; copyright the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey)

Turbutt was back at the Deanery with Parsons on the evening of Guy Fawkes Day, a Sunday:

After lunch I looked through a lot of very interesting photos of the Coronation, and the Westminster Pancake. There is an old custom at Westminster School that on Shrove Tuesday the cook makes a large pancake which is thrown among the boys to be scrambled for. The boy who gets the largest part receives a guinea from the Dean. What the origin of the custom is I do not know. At 3 p.m. we went to the evensong at the Abbey. We occupied the Minor Canons’ seats which was a great privilege, and the seats were vey nice. The sermon, which was very good, was preached by the Rev. Hensley Henson [1863–1947], Vicar of St Margaret’s Westminster. The anthem was ‘O come hither’ by [Louis/Ludwig] Spohr [1784–1859], out of the Last Judgment [1825–26]. It was very nicely sung, but the singing cannot compare with that of St Paul’s or Magdalen for quality. ([IV] Diary 5 November 1905)

After that, during the week, Turbutt’s life, like those of his friends, was much more governed by routine than had been the case at Oxford, but there were concerts and plays in the evenings, and Turbutt bought a “Piano Player ‘Euterpe’ which is a very wonderful instrument, playing the most difficult pieces with the greatest facility. It has only been invented a year or two, & is indeed a marvellous machine” ([IV] Diary 20 October 1905). On Sunday 26 November, Turbutt went back to the Abbey for evensong, where he met the Dean, who lent him the stall of one of the Canons for the service and then invited him and the preacher to stay for supper, “which invitation we accepted”. Turbutt then stayed on for Compline, which the Dean held in his private chapel or thereabouts: “The Dean was very kind, & said he hoped I should often come to see him” ([IV] Diary, 26 November 1905). This meeting marked the start of a friendship that would last up to the end of Turbutt’s life. On the weekend of 2/3 December, Turbutt was back at the Deanery with Parsons, who was recovering from scarlet fever, and this time the Dean, who had recognized Turbutt’s enthusiasm for architecture and ancient buildings, showed him

all the kitchens and cellars of the Deanery most of which are very ancient. He also showed me the very interesting plaster effigies of the Kings & Queens of England which have recently been discovered in the Deanery. There was one particularly fine one of Henry VII only with his nose broken off partially.

The Dean also provided the two friends with tickets that permitted them to listen to Brahms’s Requiem, performed with full orchestra, from choir seats in St Paul’s:

It was most beautiful and impressive, and performed with the utmost skill and taste by that wonderful choir at Paul’s under the supervision and directorship of Dr [later Sir George Clement] Martin [1844–1916; organist of St Paul’s 1888–1916]. ([IV] Diary 5 December 1905)

On 3 February 1906, Turbutt moved to Tower Hill Manor House, Gomshall, near Guildford, Surrey, and commuted into London daily. Meanwhile, back in Oxford, by 12 March 1906 only £1,300 had been raised for the purchase of the Turbutts’ First Folio. So Bodley’s Librarian, the Celtic and Biblical scholar Edward Williams Byron Nicholson (1849–1912), got permission from the Curators to spread his net wider and implement two strategies. He approached the 5,000+ members of Oxford’s Convocation and published a long letter in The Times asking for contributions from any source. His appeal was reasonably successful but fell short of its target, and on 30 March Turbutt noted in his Diary that up to 28 March: