Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born: 7 October 1883

Died: 11 May 1917

Regiment: London Regiment (London Scottish)

Grave/Memorial: Tank Cemetery, Guémappe: C.23

Family background

b. 7 October 1883 in the East Indies as the eldest son and eldest child of the six children of Duncan Mackinnon [II] (1844–1918) and his second wife, Margaret Braid Mackinnon (née MacDonald; b. 1853 in Bengal, d. 1932) (m. 1882). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living at 16, Hyde Park, London W2 (five servants), and was still using this address in 1911; after being widowed, Margaret Braid lived at 22, Hyde Park Square, London W2.

Parents and antecedents

The Mackinnon family had its origins in the Scottish Highlands and are reputed to have moved to Campbeltown – a “Royal Burgh” (1701) at the head of a small sea loch at the south-eastern end of the Mull of Kintyre – from the neighbouring Island of Arran in the Firth of Clyde. William Mackinnon [I] [later Sir; 1st Baronet] (1823–93), with whom the Mackinnon family’s rise to riches began in earnest, was the son of Duncan Mackinnon [I]. William [I] was born in Argyll St, Campbeltown, as the youngest of 13 children, only five of whom survived into adulthood, and he attended school until he was about 13, when he was apprenticed to a grocer. His father, Duncan Mackinnon (1766–1836) became a revenue constable (customs official) in 1820 and his mother, Isabella Currie (1779–1861) (m. 1798), was the daughter of a tenant farmer.

Although William was soon able to set up his own grocery shop on Main Street, in 1841 the failure of his business and a serious respiratory illness caused him to move to Glasgow, 61 miles north-east of Campbeltown and Scotland’s leading industrial centre, where he worked first as a clerk in a silk warehouse and then in the office of a merchant who traded with India in cotton and cotton goods. In 1846, when the trading monopoly of the East India Company was coming to a close and more opportunities for private enterprise were starting to multiply, William, using his commercial experience as a base, went out to Calcutta, where there was sizeable Scottish business community, with the intention of developing trade relationships between Calcutta, Liverpool and Glasgow. Once there, he immediately travelled northwards to the Ganges, where he became a working partner of Robert Mackenzie (c.1816–1853, who drowned when the immigrant ship Aurora sprang a leak and sank off Cape Howe in South-East Australia). Mackenzie was a former bank clerk from Campbeltown and an old school-fellow of William’s who had recently set up a small general trading agency in Ghazipur. In December 1847 William and Mackenzie founded Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. at the village of Cossipore, just north of Calcutta, and in 1853 the firm relocated to Calcutta itself, where, in September 1856, it became the Calcutta and Burmah Steam Navigation Company (C&BSN), plying its trade between Calcutta and Rangoon. Between 1860 and 1862 the C&BSN grew from three to nine steamers and paid out dividends at 8%, and in late 1862 it became the British–India General Steam Navigation Company (BINC), whose headquarters were at Winchester House, Old Broad St, London EC2. Under William’s direction, the Company became one of the largest shipping companies in the world, trading mainly in cotton, metal goods, silk goods and jute sacking, around the coasts of India, Burma and the Persian Gulf, and along the east coast of Africa.

In 1852, following Robert Mackenzie’s death, William [I] set up the firm of William Mackinnon & Co. in Glasgow – initially at 116, St Vincent Street. It “quickly became the driving force of the UK end of the business” and specialized in arranging exports from Glasgow and Liverpool – mainly cotton goods but sometimes iron commodities. For most of the 1850s and 1860s William worked as its resident partner, looking for work and “obtaining the finance for the purpose-built steamships which he was determined should be added to the company’s fleet”. During these early years, he was particularly successful in obtaining credit from the City of Glasgow Bank (founded 1839), of which he became a shareholder in 1857 and an assiduous Director for three years starting in July 1858. Although his interest in the Bank diminished after autumn 1861, as the focus of his new business interests gradually moved to London, he remained a Director of the Bank until 18 July 1870 (Chairman from 1865 until 1870), but sold all his shares in 1874. During the 1870s William Mackinnon & Co. became less successful as a business – making profits of a few thousand pounds p.a. This was partly because of global economic trends, partly because William lost interest in the cotton goods trade, and partly because of his shift of focus: he finally retired from the Glasgow firm in 1884.

During the 1860s, the BINC competed with the pre-eminent P & O Company to establish other lines of connection between India and Britain, the Dutch East Indies, and Australia. Moreover, William had the Company’s ships constructed so that they could transport troops – e.g. the garrisons of places like Aden and Singapore, and even entire regiments – making it unnecessary for the Indian Government, with which he had increasingly close links, to maintain a large transport fleet, and ensuring employment for his vessels. In 1864 the Company began transporting Muslim pilgrims to and from Jeddah, and in spring 1865 it took over the Netherlands India Steam Navigation Company (NINC). Although, within a year, William had assembled a fleet of eight steamships in order to establish a line of connection between India and Australia via Indonesia, by 1870 the routes covered by his ships still did not extend to southern Africa or Australia. Forbes Munro summarizes the achievements of the Mackinnon Group and its two steamer companies as follows: it was

the pre-eminent shipper of mails, money, passengers and fine cargos around the coasts of India and its near neighbours. It had created regular steam lines where none had existed before, along routes on which it introduced more frequent scheduled sailings over time. It offered new transport facilities on which many members of the travelling public, and the merchant communities and local officials at the many ports, came to depend. It had built a network of agents and sub-agents to foster its interests and to mediate with its customers […]. It had also blocked the rise of a potential rival in Burma and had seen off two competitors in western India.

As a result, the Company grew physically and benefited financially, and “by 1870, on a paid-up capital of £442,000, it had assets worth £633,788, including 23 steamers valued at £441,000 and financial reserves of £111,444”. In short, the Mackinnon Companies were increasingly acting as “agents of empire” by providing “routine services for and within an established imperial order” and their “informal imperialism” had “started to acquire wider horizons”.

Photograph showing PS Ramapoora (1887–1919; scrapped) of the BINC after arriving at Rangoon from Moulmein (a nine-hour journey)

In 1856, William [I] married Janet Colquhoun Jameson (1833–94), the eldest daughter of Robert Jameson (c.1796–1874), a Glasgow solicitor, who was a respected member of the Glasgow élites and would act as William’s principal legal adviser for 18 years. In 1869 William bought the mansion house and estate at Loup and Balinakill, Argyllshire, in the north-west corner of the Mull of Kintyre, and began to develop the centre of Clachan, the nearest village, where most of the estate workers lived and where there was a jetty looking westwards towards the Atlantic Ocean. His obituarist in the Argyllshire Herald would later comment:

In both these estates [the second one being Strathaird on the island of Skye], the tenants are in a most comfortable condition, and unlike many other parts of the Hebrides, the rents fixed by the landlord are not exorbitant, but suited to the circumstances of the tenants, and not that of the “grinding” rate which has proved so disastrous to so many well-doing and capable farmers in the county.

William and Janet soon began to entertain friends and family on his new estate, especially in the spring and autumn, and also potential business associates whom they needed to impress. Summers were frequently spent on the continent in the fashionable spa town of Bad Homburg, in the Taunus Mountains of Hesse; and winters were spent in the relative warmth of the south of France and Italy. When William and Janet of necessity paid a visit to London, they did not stay in another property of their own, for they did not own one down south, but in the Burlington Hotel, Burlington Street, London W1, where they entertained as generously as they did in Balinakill.

The Suez Canal opened in November 1869, and according to Forbes Munro, William responded to the challenge it presented by increasing the size of his joint trading fleet over the next 13 years from 23 vessels (totalling 21,752 tons and valued at £441,000) to 84 steamers (totalling 123,704 tons and valued at £1,078,604). It thereby became the world’s largest company-owned fleet. At the same time, he gradually switched from sail (c.64% in 1872/73) to steam (c.71% in 1882/83); diversified into “inter-continental steamshipping between Asia and Europe”; and invested in large, specialized steamers that were designed to carry “heavy deadweight cargoes”. Consequently, the BINC and the NINC not only had at their disposal cash reserves for long-term investment and protection against fluctuations of the market, but succeeded in becoming two of “the greatest beneficiaries of the opening of the Suez Canal” with the result that William was “propelled […] into the front rank of British ship-owners of the time”.

The RMS Le Quetta (1881–90) passing through the Suez Canal. On 28 February 1890, while en route from Brisbane to Batavia, she sank in five minutes after hitting an uncharted rock off Albany Island near the far northern coast of Queensland, causing the death of 134 of the 292 passengers and crew on board.

By removing the necessity of making the long voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, the Suez Canal also brought the territories in the north-west corner of the Indian Ocean significantly closer to Europe. William and his staff began thinking about the economic and political implications of this new situation in early 1869, especially the desirability of providing Mombasa, a coastal town in East Africa that already possessed an excellent harbour, with a new surrounding infrastructure – thereby turning it “into a maritime cross-roads between Britain, India and South Africa”. And when, in 1878, he opened negotiations with Sultan Barghash-bin-Said (1837–88), the second Sultan of Zanzibar (1870–88), he was offered c.590,000 square miles of relatively unused inland territory as a British Protectorate. But the British Government was not interested in investing taxpayers’ money in such a proposal, and so, over the next decade, allowed the East African coastal territories to be carved up among various Western European powers with imperial ambitions during the so-called “Scramble for Africa.” But although William’s desire to create a “hub port” in East Africa had not made much progress by mid-1879, in October of that year he opened a monthly service from Bombay to Delagoa Bay (now Maputo Bay), c.250 miles north of Durban in the Natal, which called in en route at Zanzibar and Mozambique.

Nevertheless, the 12 years following the opening of the Suez Canal saw not only a growth of Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co.’s activities, but also a change in their nature, and the Group’s investment portfolio showed “an increasing concentration on shipping at the expense of both commodity production and manufacturing”. By 1875 the Group’s centre in Britain had moved from Glasgow to London, “the hub of the British financial system” with “abundant access to the commercial finance”, marine insurance, and tea wholesaling, and by 1881, its combined capital stood at £2.87 million and its assets at nearly £3.5 million. 1881 was also the year when Mackinnon’s Queensland Royal Mail Line began services between London and Brisbane, and as the number of assisted migrants to Queensland grew – from 3,190 in 1880 to 15,395 in 1883 – so Mackinnon was able to increase the frequency of voyages from once a month to once a fortnight. In 1886–87 he created the Australasian United Steam Navigation Company, which meant, according to Forbes Munro, “that the Mackinnon group now dominated steam-shipping in coastal waters throughout the great swathe of territory comprising India, Indonesia, and Australia” and was “the world’s largest maritime conglomerate”. But the end of the 1880s saw the beginning of a global depression which affected Australia and diminished the initial success of Mackinnon’s Queensland venture. The situation was repeated in the East Indies, where the Dutch reacted to the depression by excluding British shipping from their colonies, thereby threatening “the activities of William Mackinnon and his business group at several points across their sprawling trade and transport empire”, and in 1890 William, whose commercial attention was by now well focused on East Africa, succumbed to Dutch pressure by selling the Netherlands–India company to a Dutch firm that specialized in the fast delivery of packages and parcels.

On 2 October 1878 The City of Glasgow Bank collapsed because of extensive loans that were poorly secured, speculative investments in risky foreign ventures, false reports of gold holdings, falsified balance sheets, and secret purchases of its own stock in order to hold up share prices. The crash, which ruined all but 254 of the Bank’s 1,200 share-holders, revealed that the Bank was more than £7,300,000 in debt, and in the course of their investigations, which culminated in a trial in January 1879 when all the current Directors received jail sentences, the liquidators decided that William, as a past Chairman of the Board, must be partly responsible for the Bank’s situation. So having estimated that he was liable to the tune of £400,000, they raised a motion against him in the Court of Session. But William refused to accept the charges or negotiate any form of compromise with his accusers, and in the end the case against him was dropped and he was released from all liability.

After weathering the legal and financial storms in Glasgow, William moved to London in 1882, where his interest in East Africa was reawakened. Although between 1883 and 1885 this interest had been alive but focused on Egypt and the Congo, by 1885 it had returned to Zanzibar and the “Swahili Coast” of East Africa, where a competition for new colonial territories was developing between Britain and Germany, with Germany in the lead by autumn 1886. By this time, according to J.S. Galbraith, William had become “a convert to the religion of imperialism”, and as he was “a far more ardent imperialist than the cautious politicians of Whitehall”, he was willing to attempt “by private means to accomplish great public ends”. So in order to realize his earlier ideas about “the development of trade along the Arab–Swahili coast”, William proposed the setting up of the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEA), and set out its six main aims as follows in a document of April 1888:

(1) abolition of the slave trade;

(2) perfect religious freedom;

(3) a justice system that gave due regard to indigenous customs and laws;

(4) an absence of trade monopolies;

(5) restrictions on the import of spirits, opium, arms and ammunition;

(6) equal treatment of all nationalities.

Consequently, in September 1888, Queen Victoria granted William a Royal Charter to set up the IBEA, with himself as President (Chairman) of its Court (Board) of Directors. But the Charter also charged the new Company with the discharge of imperial duties and the protection of British interests without the receipt of British aid. So although the Anglo-German agreement of July 1890 settled several outstanding colonial issues and, in theory at least, gave William a better opportunity to realize his high-minded expansionist schemes in East and Central Africa, these enjoyed little success. The British Treasury was still unwilling to support a new colonial venture along the coast of East Africa and his Scottish backers were unable to offer him any further long-term financial support because of the Group’s difficulties in other parts of the world and the “general depression in the shipping trade” of 1891–93.

In 1882 William was made a Commander of the Indian Empire (CIE) and on 15 July 1889 he became the 1st Baronet of Inverar in recognition of his creation of IBEA. But the title lapsed on his death as he and his wife had no children – and he left no natural successor as leader of the Mackinnon Group. In March 1893, William, whose health had been failing for at least four months and whom Forbes Munro describes as a “spent force”, resigned as President of IBEA. On 22 June 1893 he died peacefully in the Burlington Hotel, aged 70, of “acute quinsy”, a particularly severe throat infection connected with tonsillitis. By the time of his death, the Mackinnon Group of companies owned c.110 vessels and employed more than 1,300 officers and engineers and over 10,000 seamen, stokers and stewards. And in her study of “Wealthy Scots, 1876–1913”, Rachel Britton records that in 1893 Sir William Mackinnon, 1st Baronet, merchant and landowner, came second in that year’s table of wealth with an estate worth £560,563 (£38,962,218 in 2005) – of which about £260,000 (c.46.4%) went to his widow, family members, friends, employees and local charities. His cousin James’s son Duncan [II] received £60,000 and William stipulated that if any of Duncan’s children survived him, then the trustees were to divide that sum equally between them. Duncan’s son William [II], the subject of this biography, received £5,000 and Duncan [III], William [II]’s younger brother, together with three others of William’s relatives, were left the residue of the estate “to be divided up among them”. According to Britton, in 1904 Peter Mackinnon, another member of the family who lived in Dunoon and described himself as an East India Merchant, came eighth in the table of wealth with an estate worth £301,968.

William’s coffin was brought from London to his home and the extremely plain funeral, which attracted a congregation of over 200, many of whom had come from Glasgow by ferry, took place on 28 June 1893. Two simple services were held simultaneously – one inside and one outside the Mackinnons’ mansion – during which the coffin was carried through the village to the Clachan Burying Ground on the Mull of Kintyre, where it was interred not in a family grave but in the cemetery where many of the previous Lairds of Ballnakill already lay. At the request of his widow, there were no wreaths and no floral tributes.

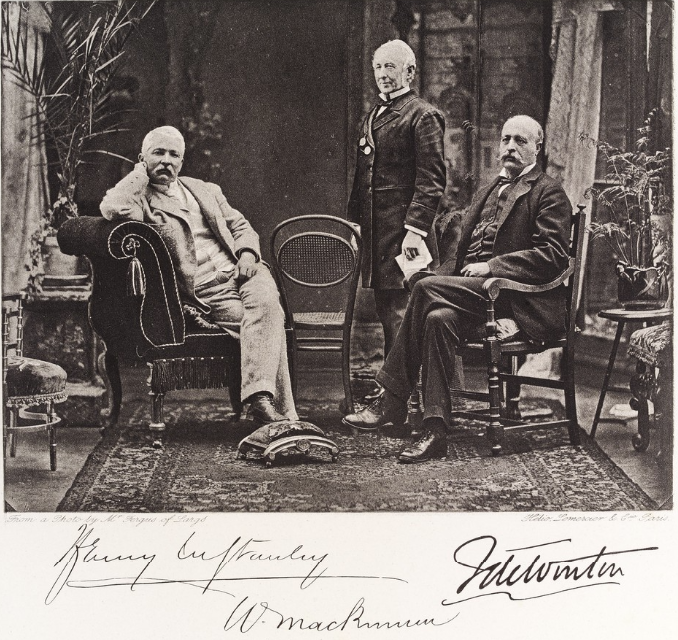

Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), Sir William Mackinnon (1823–93) and Major-General Sir Francis Walter de Winton (1835–1901) (c.1890)

(Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

Several obituarists – including Henry Morton Stanley – pointed out that William [I]’s commercial zeal was not motivated solely by considerations of power and profit, and the aims informing IBEA also indicate this. Rather, he was endowed with a high moral sense that derived from his long-standing and devoted commitment to the Free Church of Scotland, “according to the principles as formulated in 1846” following the “Great Disruption of 1843”, when William sided with the Constitutional Party. Consequently, he was committed to a “work ethic that sustained long hours of labour and a willingness to suffer the discomfort of regular travel in the interest of family and firm”. Indeed, according to Forbes Munro, Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. was distinguished from other Calcutta firms by its more active support of the Kirk. Moreover, many of the Group’s resident partners in Calcutta were “elders or deacons in the Free Church in Calcutta, and sat on its Financial and Corresponding Board”, and the Group contributed generously to the work of the Kirk both at home in Scotland and abroad. One obituarist noted that “many a poor and struggling man could tell of [William’s] warm-hearted liberality”. Besides having a Calvinist aversion to alcohol and smoking, William was a strict Sabbatarian, and if one of his vessels was in port on a Sunday, it was not allowed to leave that day; moreover, all work – including the opening of letters and telegrams – was forbidden and its officers and crew were required to attend church; and if a vessel was at sea on a Sunday, church services on board were obligatory. He also disapproved of “all innovations in public worship as contrary to Scripture and to the entire genius of Presbyterianism” – including the use of instrumental music in churches.

When, in 1866, there was a devastating famine in the Bengalese state of Orissa (now Odisha) that would cause over a million deaths, imports of rice were urgently needed. But as soon as William [I] learnt that the Mackinnon Group’s agents had negotiated a very profitable contract with the Indian Government for importing rice from Burma to Orissa at enhanced rates, he ordered the work to be done at rates that were even lower than the ordinary ones. He was a committed opponent of slavery, and when, in 1886, c.£30,000 was needed to mount an armed expedition, led by Henry Morton Stanley, for the relief of Emin Pasha (1840–92), William personally donated c.10% of that sum. He did this partly to prevent the death of the man whom General Gordon had left in charge of Equatoria, the southernmost province of the Sudan, before his own death in Khartoum at the hands of Mahdist rebels on 26 January 1885. But he also felt that such an expedition would contribute to the suppression of the slave trade and hasten the opening up of Africa “to legitimate commerce, civilisation, and Christianity just as had happened in India”.

Finally, in summer 1891, William’s IBEA founded the East African Scottish Mission, an interdenominational organization whose aims were not only ethical and religious, but also educational and industrial. Shortly before his death, Sir William and his nephew Duncan MacNeill (1837–92) created the Mackinnon MacNeill Trust, whose mandate was “to provide a decent education to deserving Highland lads”. In 1915, after sufficient funds had accumulated, the Trust founded a residential school, the Kintyre Technical School, which specialized in engineering and agriculture, in Southend, near Campbeltown. In 1925, because the original building had been destroyed by fire, the College moved to Helenslee House, Dumbarton, and operated there until 2000. The Trust still exists and now awards educational bursaries to both boys and girls from the Highlands. William’s obituarist in the Argyllshire Herald called him “a model man in every sense of the word, useful to his generation in all possible ways, and after attaining his allotted span, dying in harness, beloved and respected by all classes, from kings of the nation and eminent men in all walks of life, down to the humble peasant”. And in The Scotsman his obituarist described him as

the true-born Highland gentleman, courteous and courtly in manner, gentle and genial, hospitable and helpful. His heart always warmed to the tartan wherever he saw it. The clan feeling was very strong in him. Anyone who bore the name of Mackinnon or had a drop of Highland blood in his veins could always rely on substantial help from him. […] It gave him unalloyed pleasure to make others happy. He lived not for himself, but whatever form his many-sidedness took, he always worked for some high and worthy object, either philanthropic or patriotic.

Duncan Mackinnon [II], the father of William [II] (our subject) and Duncan [III] Mackinnon, was the son of William [I]’s cousin James, and in 1864, after serving an apprenticeship with William Stirling & Co., “one of Glasgow’s oldest and most distinguished merchant houses”, which specialized in the manufacture and export of linen and cotton goods, he was sent out to Calcutta to become an assistant in Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. He was made a Director of the firm in 1870 and in 1873 he returned to Campbeltown to marry Jean (“Jeanie”) Macalister Hall (1846–79), “a lively and attractive young woman” who was the daughter of a Glasgow solicitor, and also a member of a family to whom the Mackinnons were already related. In 1877 Duncan [II] was appointed a Commissioner of the Port of Calcutta and became the President of the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, and seemed set for a distinguished career in a rising firm. But as Jeanie did not particularly like Calcutta, she insisted on having their first child in Campbeltown, where the infant – a little girl – died when she was only two days old. Jeanie’s health had been weakened by the difficult birth and when, in March 1879, circumstances required Duncan to return to Calcutta, Jeanie accompanied him, only to die there herself on 4 April 1879, a few days after their arrival. As a result, Duncan suffered a nervous breakdown later in the year and went back to Scotland in August 1880 in order to attend his wife and daughter’s re-interment in Campbeltown Cemetery. Two years later he married for the second time, but his promising career in India was over. Nevertheless, he returned to Calcutta for a short term of duty in 1883, but made it clear that he regarded the city’s climate as a health hazard. In 1884, when each of the Senior Partners was made responsible for the firm’s affairs in different parts of the world, Duncan was allocated the London–Calcutta Line and various related activities. Despite all his personal vicissitudes, he rose to becoming a Director and finally the Chairman of the firm, and in 1894, after his uncle’s death, he found himself in overall control of the BINC. When he died, aged 73, on 1 March 1918, his widow and two daughters inherited an enormous estate worth £11,781,000 (less tax of £1,308,667), the equivalent of over £470 million in 2005.

Siblings and their families

Older brother of:

(1) Peter (1885–1904);

(2) Duncan Mackinnon (Duncan [III];1887–1917; killed in action on 9 October 1917 at Louvois Farm, near Langemarck, while serving as a Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, the Scots Guards);

(3) Gladys Margaret (1889–1973); later Pollok after her marriage in 1921 to Allan Bingham Pollok (later OBE) (b. 1874 in Ireland, d. 1949): two sons and two daughters;

(4) James Macdonald (1891–94);

(5) Katharine Auld (1894–1937), Ardmaddy Castle, Oban.

Peter was destined for a career in the Royal Navy and from 15 May 1900 to 15 September 1901 he underwent four terms of very tough training as a naval cadet aboard HMS Britannia, the three-deck hulk of a wooden battleship that had been launched in 1860 as the HMS Prince of Wales. It was renamed HMS Britannia in 1869, when it was sent from Portland to Dartmouth as a replacement for an earlier HMS Britannia that had been serving as the Royal Naval College since 1863, pending the construction of the shore-based College at Dartmouth (which opened in 1905). Peter was commissioned Midshipman on 15 October 1901 and served in the Channel Squadron on the cruiser HMS Diadem (1896) from 15 September 1901 to 4 February 1902. He was then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet, where he served aboard the pre-Dreadnought battleship HMS Irresistible (1898) from 4 February 1902 to 1903 and then the newly commissioned pre-Dreadnought battleship HMS Albemarle (1901; scrapped 1920) from 1903 to 31 January 1904, when he committed suicide by shooting himself in the head during a bout of “temporary insanity”.

Duncan [III] had done no rowing before he came up to Magdalen in October 1905, but he quickly made a name for himself as an oarsman and in December 1907 he rowed in the trial VIIIs. But although he rowed well in the winning crew that was captained by Arthur Clements Heberden of Trinity College (c.1887–1917; killed in action on 10 July 1917 while serving as a Second Lieutenant in the Second Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps), he was passed over at the end of 1907 when the Oxford VIII was selected for the race of 1908 – perhaps because it was thought that he was as yet lacking in experience and style. Nevertheless, in summer 1908 he rowed at No. 4 with A.G. Kirby and J.R. Somers-Smith in the Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC) VIII that remained Second on the River. Although, in the same year, Magdalen could enter only one IV at Henley, Duncan gave further proof of his prowess as an oarsman, for with Collier Robert Cudmore at bow and Gillan at No. 2 – both of whom would survive the war – and Somers-Smith as stroke, he helped Magdalen’s IV to win both the Stewards’ Cup and the Visitors’ Cup in record time (7 mins 28 secs and 7 mins 30 secs; the first record stood until 1925). This fine performance led the Olympic Committee to invite Leander and the MCBC IV to represent Britain in the Olympic Regatta of summer 1908, which was rowed at Henley over a course that had been lengthened to one-and-a-half miles. The MCBC IV then beat the Argonauts (Toronto) in the semifinal followed by Leander in the final to win an Olympic Gold Medal and their fifth consecutive event on Henley water.

Duncan was elected Junior Common Room President for the year 1908–09, which began with him and Somers-Smith rowing in the crew that won the autumn OUBC IVs. At the end of 1908, he again rowed as no. 7 in the Oxford trial VIII that was stroked successfully and for the first time by the legendary Robert Croft Bourne (1888–1938) of New College, and he was also selected to row as a powerful no. 5 in Bourne’s first crew of 1909, five other members of which were also Magdalen men: Cudmore, A. Stanley Garton, James Gillan, Kirby and A.W.F. Donkin (cox). This crew of heavyweights won comfortably and broke a run of three Cambridge victories. Later in the year, the same crew succeeded in remaining Second on the River in five hard-fought races during Eights Week of 1909. At Henley a few weeks after that Duncan rowed with Somers-Smith, Kirby and R.P. Stanhope in the Grand Challenge Cup Race. But Kirby had sprained his knee badly while training and had to row the race with it bandaged, and Stanhope, the stroke, strained his stomach and had to row with his body strapped up. So it was, perhaps, inevitable that they were beaten in the Grand by a Belgian crew and in the Stewards’ by Thames. Nevertheless, at the end of the year Duncan rowed in the Magdalen crew that won the Varsity IVs with ease, and was elected President of the OUBC for 1910. That year would be a great one for Duncan, and on 23 March 1910, with himself at no. 5 again, Oxford won the Boat Race with ease once again by three-and-a-half lengths after spurting for one final time when they reached The Dove public house. Among the oarsman then were Donkin as cox for the fourth time, Garton (No. 6) and Philip Fleming (1889–1971; Magdalen 1908–10, left without taking a degree; the younger brother of Valentine Fleming) (No. 7).

In May 1910, Duncan rowed as No. 5 with Milo Massey Cudmore, the younger brother of Collier Cudmore, and W.D. Nicholson in the Magdalen VIII that went Head of the River after a gap of three years by bumping Christ Church off Head on the first evening of the Torpid races. A few weeks later, the same Magdalen VIII was entered for the Grand at Henley, where it crowned the year by finally winning that most prestigious of trophies, the first college VIII to do so, by beating Jesus (Cambridge) and Leander by three-quarters of a length. In doing so, the VIII had, in effect, beaten the invincible Bourne himself, for on this occasion it was he who was stroking the Leander VIII which included Duncan [III]’s old friend Kirby as one of its crew. Duncan was, however, persuaded to row for Oxford for one last time, and on 1 April 1911 he rowed at No. 7 in Bourne’s third crew. This crew not only beat Cambridge yet again by two-and-three-quarters lengths, but broke all previous records for the Putney to Mortlake course by completing it on a fast spring tide and with a light easterly wind in the “wonderful time” of 18 minutes 29 seconds. Moreover, Nigel McCrery points out that the race was made “all the more interesting” because it was followed by Prince Albert (the future George VI) (1895–1952) and the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) (1894–1972), who was an undergraduate at Magdalen from 15 October 1912 to August 1914 (p. 175). Although the Magdalen VIII with its five Blues was knocked off Head of the River by New College in the summer races at Oxford, the same crew, rowing with 12 foot 6 inch oars, “admirably stroked by Bourne” and reinforced by Kirby and Fleming, went on to Henley. Here they won the Grand for the second successive year, another first for a college VIII, by defeating New College, Ottawa, and Jesus College, Cambridge. It must have been a wonderful moment for the friends to share, not least because it was the last time that Duncan would appear on the river.

A much fuller version of the above text is to be found in Duncan Mackinnon’s own biography.

During World War One, Allan Bingham Pollok served as a cavalry officer (Captain, then Major) in the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers and the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars (London Gazette, no. 31,622, 28 October 1919, p. 13,218), and fought in France and Flanders with the British Expeditionary Force and then in Mesopotamia. On 4 December 1916 he became the Commanding Officer (CO) of No. 2 Cavalry Officers Cadet School (LG, no. 29,803, 24 October 1916, p. 10,397) and in early 1919 he was made Assistant Commandant of the Remount Service (LG, no. 31,113, 17 January 1919, p. 1,026).

Wife and children

William Mackinnon [II] married Lucy Vere Stewart (1883–1977) in 1908; she was the third daughter of Hinton Stewart, a merchant from Strathgarry, Perthshire.

He was the father of:

(1) Duncan [IV] (later JP) (1909–84); married (1932) Pamela R. Brassey (1911–85); two children;

(2) Angus (later MC, DSO) (1911–87);

(3) Esme (“Muffie”) Margaret (1913–99); later Murphy after her marriage in 1936 to Louis M. Murphy (later Colonel) (1908–74).

William [II]’s family lived at 46, Queen’s Gate Terrace, London SW7, then 50, Evelyn Gardens, Kensington, London SW7.

Duncan [IV], William’s first son, studied at Magdalen from 1928 to Christmas 1929. He joined Smith and Aubyn in 1932, and became the Company’s Chairman from 1955 to 1973; from 1959 to 1961 he was Chairman of the London Discount Market. In the 1930s he joined the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, but smashed his knee in a sporting accident at the beginning of the war and thereafter served as a Captain on regimental duties. From 1949 to 1950 he was High Sheriff of Oxfordshire.

In 1939, Angus, William’s second son, enlisted as a Territorial Army volunteer in the 8th Battalion, the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders. He was with them in the British Expeditionary Force (51st [Highland] Division) in 1940, stationed among French units in the vicinity of Metz. When the French Army collapsed in June 1940, the Battalion marched 400 miles to the French coast. His conduct as a very junior officer earned him the MC. From 1941 to 1943, he was a member of General Auchinleck’s Staff in the Middle East, and while serving in this capacity, he spent several days in an open boat after his troop ship was torpedoed in the South Atlantic. On another occasion he reconnoitred the German lines for Auchinleck by travelling in the bomb bay of a Blenheim bomber. By D-Day, he was second-in-command of his Regiment’s 7th Battalion and in September 1944 he became the Battalion’s CO; during the Battle of the Bulge (16 December 1944–25 January 1945) he was awarded the DSO.

During the 1930s, William’s daughter Esme became a champion Alpine skier who represented England. At the age of 18 she won the first World Alpine Ski Championship in 1931 when the event was held at Murren in Switzerland.

Louis M. Murphy was a professional soldier in the Indian Army who became Master of the Devon and Somerset Staghounds and left £103,544 (c.£500,000 in 2005).

Education and professional life

From c.1890 to 1898 Mackinnon attended Grove House Preparatory School (also known as Mr Pridden’s School after its founder Frederick S. Pridden (1854–1916), a former housemaster at Clifton College), Boxgrove, near Guildford, Surrey (cf. William Mackinnon and H.F.C. Horsfall). He then attended Rugby School, Warwickshire, from 1898 to 1902, where he became his House Captain in 1901 and a member of the first shooting VIII in 1902. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1902, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1902. In the Trinity and Michaelmas Terms of 1903 he took his First Public Examinations, including an optional paper in Classics, and he then began to read for a Pass Degree during the three terms from Michaelmas Term 1904 to Trinity Term 1905 (Groups A1 [Greek and/or Latin Literature/Philosophy], B3 [Elements of Political Economy], and B4 [Law]). He took his BA on 29 June 1905. In his final year, he was persuaded to row in the 2nd Torpid VIII (with E.H.L. Southwell), but he discovered that, unlike his brother Duncan Mackinnon, he had little talent for the sport, and the Captain’s Book noted: “Mackinnon rowed hard, but his style is not to be recommended.”

After graduating, he went into business as a merchant and was made a partner in the following firms, all three of which were linked in some way with William Mackinnon [I]’s nineteenth-century enterprises: (1) William Mackinnon & Co., 203, West Broad Street, Glasgow (see above); (2) Gray, Dawes & Co. (1907), 23, Great Winchester Street, London EC2, a firm specializing in ship chartering and marine insurance which had been set up in 1865 by a nephew of William [I] with the help of his uncle; and (3) Duncan Macneill & Co., Winchester House, Old Broad St, London EC2, a firm specializing in tea-broking, bill-broking and other financial transactions involving a middleman that had been set up in 1870 by an orphaned nephew of William Mackinnon [I].

“His coolness under fire and sound judgment did much to bring D Company through with comparatively few casualties. He looked after his men like a father and never spared himself on their, or on our, behalf.”

War service

William Mackinnon enlisted on the outbreak of war, and after completing his basic training he was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 1 September 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,940, 16 October 1914, p. 8,261). He was immediately posted to the 3/14th Battalion, The London Regiment, which had been formed in London in November 1914 and never saw service overseas. At first, his main task was to help with the training of recruits and on 11 June 1915 he was promoted Temporary Lieutenant. On 2 June 1916 he was promoted Captain (LG, no. 29,605, 30 May 1916, p. 5,445) and on 18 November 1916 he was transferred to the 1/14th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (The London Scottish) (Territorial Forces).

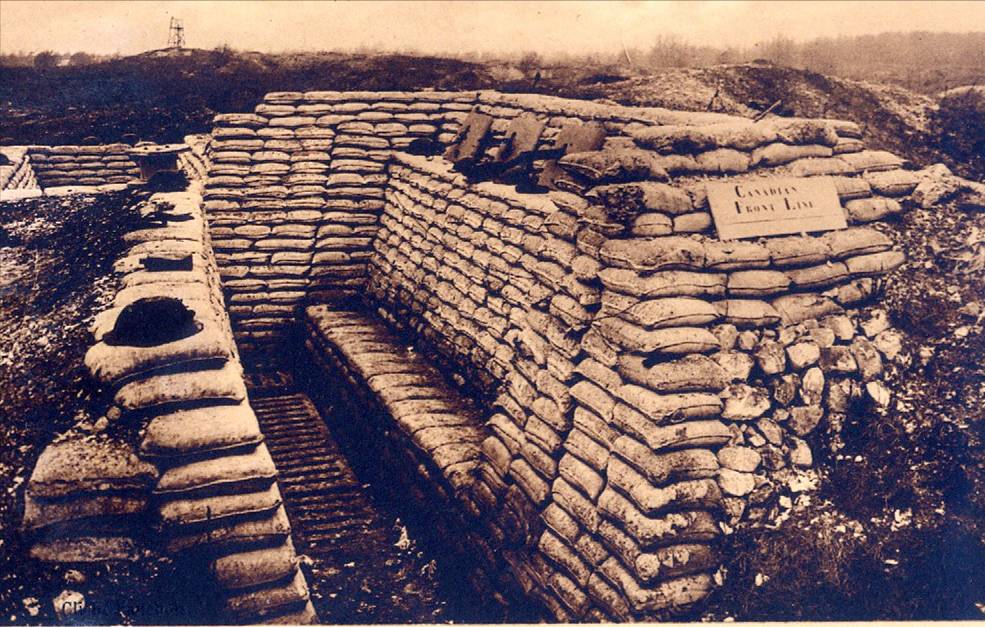

This unit had disembarked at Le Havre on 16 September 1914 and suffered terrible casualties during the Battle of the Somme (1 July 1916–18 November 1916) as part of 168th Infantry Brigade, in the 56th (1/1st London) Division. On 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the 168th Brigade was part of the failed pincer movement that became known as the Battle of Gommecourt (see J.R. Somers-Smith) – and lost 500 of its members killed, wounded and missing. The Brigade was then withdrawn to absorb reinforcements, and returned to the front between 6 September and 7 October, when it took part in the Battle of Morval and the capture of Combles (25–28 September), and also the opening phase of the Battle of Transloy Ridge (7 October). During this period, the 168th Brigade suffered a further 531 casualties, making a total of more than 1,000 casualties during the previous two-and-a-half months, 50 of whom were officers. During the small hours of 8 October 1916, the survivors of the 1/14th Battalion were withdrawn to Frémont, six miles north-north-east of Amiens, and after spending ten days there and absorbing more reinforcements, the Battalion, as part of the 56th Division, moved northwards to the Laventie sector of the front, between Béthune and Armentières, where it was allocated to trenches at the tiny village of Fauquissart, two miles south-east of Laventie. After receiving a heavy artillery barrage on arrival, the Battalion settled into a relatively quiet routine of six days in the front line, six days in support at Laventie, and, occasionally, 12 days behind the front in Divisional Reserve where amenities were better. In February 1917 Captain E.D. Jackson, a regular officer of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, took command. During the preceding 15 months of hard fighting, William had, however, been held back in England.

Between 9 February and 15 March 1917 the Germans withdrew eastwards along a 50-mile front (Operation Alberich) to their newly fortified Hindenburg Line. This was not a retreat, but a strategic move that was designed to shorten their line, straighten out a salient, improve their communications, and leave a large area of scorched earth to their front. So the two Allied Commanders in the west, General Douglas Haig (1861–1928) and General Robert Nivelle (1856–1924), drew up plans for a two-pronged attack on the flanks of the Hindenburg Line: the British around Arras and the French a week later on the Aisne near Laon, to the south-east. Although the 56th Division was meant to take part in the offensive, William’s Battalion was withdrawn from the line on 9 March and moved to billets at Vieille-Chapelle, between Béthune and Estaires. On 10 March the Battalion marched five miles north-westwards to Merville, where it entrained for the crossroads town of Doullens, 30 miles west-south-west of Merville. From here it marched another four miles north-eastwards, to billets in the village of Brévillers where it joined Third Army’s VII Corps under the somewhat lacklustre command of Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas D’Oyly Snow (1858–1940). On 12 March 1917 it marched to Ivergny, two miles north-east of Brévillers, where it trained and absorbed “a draft of well-known officers from the Third Battalion”, which included William, who was assigned to ‘D’ Company.

William’s Battalion trained hard for the next two weeks and then, on 23 March, moved c.13 miles eastwards to Gouy-en-Artois, where they did more training. On 27 March the Battalion marched c.17 miles eastwards to the ruined village of Agny, just south of Arras. Here it was attached to 169th Brigade and ordered to dig assembly trenches opposite the village of Neuville-Vitasse, two miles to the east, as this was to be one of its objectives during the coming offensive. In order to maintain secrecy, the Battalion lived in cellars and dug trenches at night, sometimes out in no-man’s-land, a task which involved a two-and-a-half mile march in darkness on narrow, slippery tracks with barbed wire and deep trenches on either side. Although it was often harassed by artillery, casualties were light until 28 March, when two shells killed ten men of ‘A’ Company and wounded 39 others. On 1 April the Battalion went into Reserve at Achicourt, just north-west of Agny, but two days later relieved another Battalion in the old British front line. On 4 April 1917, the preliminaries to the Second Battle of Arras began with a bombardment by the British on a 14-mile front from the western slopes of Vimy Ridge just north of Arras to the valley of the Cojeul. On 8 April, Easter Sunday, an unusually sunny day, the bombardment increased in intensity, and in the evening the attacking troops moved into the new assembly trenches through a drizzle that changed to sleet and huge flakes of soft snow. Mackinnon’s’s Battalion took up its positions between Neuville-Vitasse and Beaurains, just to the north, after dark, and sought what shelter they could. The trenches were deep in mud, it was hard to recognize landmarks, and the waterlogged ground was exceptionally difficult to negotiate as there were no duckboards and the men were heavily laden with “buckets of Lewis gun ammunition, a spade, bombs etc.”

The attack began at 05.30 hours on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917, the opening day of the Second Battle of Arras (9 April–16 May 1917). To the north of 56th Division, the Canadians successfully stormed Vimy Ridge on the left end of the front, while at the other end of the front, which curved round the eastern side of Arras to the south, 56th Division’s objective was Neuville-Vitasse together with a section of the German double line of defence that was immediately in front it. William’s 168th Brigade was tasked with taking the village itself and 167th Brigade with attacking the trenches to the south of the village, while 169th Brigade was in Divisional Reserve. When the Divisional attack began at 07.30 hours, 168th Brigade had two Battalions of the London Regiment (1st/12th (Rangers) and 1st/13th (Kensingtons)) at the front of the advance, with Mackinnon’s’s London Scottish in support and the 1/4th Royal Fusiliers in Reserve. At 11.30 hours, the London Scottish were called upon to attack a part of the German line known as the Cojeul Switch; it comprised three lines of trenches, and lay 1,400 yards beyond the British assembly trench. Three Companies moved forward, with William’s ‘D’ Company on the left, led by Captain Filshill (who seems to have survived the war), but the ground was so broken up and the mud so deep that progress was slow. So after a pause to realign the leading companies, the Battalion advanced against the forward German position and soon discovered that although the supporting barrage had transformed the trenches into lines of shell-holes, it had lifted prematurely, since the enemy line was still strongly defended by rifles, bombers and machine-guns. Although ‘A’ Company managed to force its way through all three German lines, it found itself outflanked and had to fall back to the second line. ‘D’ Company also moved through the three German lines, overran its objective, captured 150 prisoners, and halted 700 yards further on. But because 167th Brigade on its flank had been checked, ‘D’ Company was soon almost surrounded and being enfiladed by machine-guns from the side and rear. Whereupon it withdrew to the second German line, known as Telegraph Hill Trench, north of the Feuchy Road (see P.H.G. Pye-Smith), and helped to clear it completely. The Reserve Company then came up at dusk to bomb and clear the third trench, and finished this work by dawn. During the action, the Battalion lost three officers wounded and 87 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing, but took 290 German prisoners and captured two machine-guns, a trench mortar and a cache of ammunition, and some men were able to re-equip themselves with greatcoats and ground-sheets that the Germans abandoned in their trenches.

10 April 1917 was spent consolidating, and the Germans made no counter-attacks, mainly because they had been disrupted by the spectacular Canadian success at Vimy Ridge. Early on the afternoon of 11 April Mackinnon’s Battalion was relieved and marched back in a driving snow-storm to spend a miserable night in open trenches. For the next six days the Battalion held its position, conducted night patrols, stood-to, supported the front line against counter-attacks that did not materialize, and continued the hard work of improving shallow trenches in cold and wet weather conditions. As the British advances ceased and the great French offensive to the south ground to a halt after making small gains of territory in exchange for an enormous loss of life, the first stage of the Second Battle of Arras ended on 17 April, except for local actions to improve the line. Mackinnon’s Battalion was recalled to Arras on that day, having lost six officers and 140 casualties killed, wounded and missing, and his ‘D’ Company was able to muster 56 men, who were “very tired and dirty, shaving and washing having been quite impossible during the whole period”. On 19 April, the 56th Division was relieved and on 21 April William’s Battalion was taken by trucks to billets in the village of Coigneux, c.13 miles south-west of Arras, where it was to refit, reorganize and recuperate. Quite a few of the men needed to recover from exposure, since the Battalion had had no shelter for ten days and many still lacked the greatcoats which they had been ordered to dump before the assault of 9 April. Nevertheless, the 56th Division was transferred to XVIII Corps, and after only three days’ rest, William’s Battalion was gradually moved northwards via Gouy-en-Artois and Simencourt, about eight miles to the north, and found themselves back in Arras as the Divisional Reserve on 28 April.

The first half of the Second Battle of Arras had achieved very little: the French losses were enormous; their advance had been halted; widespread mutinies had occurred in the French Army and General Nivelle had been replaced by General (later Marshal) Philippe Pétain (1856–1951) as its Commander-in-Chief. On 2 May 1917, Mackinnon took over as the CO of ‘D’ Company, and on the following day, the second half of the Second Battle of Arras began. This was a diversionary attack along a 16-mile front by the First, Third, and Fifth British Armies and as its aim was to assist the French attack further south, the British front extended from Acheville in the north, about four miles east of Vimy, to the vicinity of Bullecourt, which was c.13 miles to the south (see R.H. Hine-Haycock and P.W. Beresford). The 56th Division attacked east of Arras, north of the Arras–Cambrai road, with 167th and 169th Brigades in the front of the attack and the 168th Brigade in support. During the night the 168th Brigade took over the front line, with the London Scottish occupying a section of the line just east of recently captured Monchy-le-Preux and the adjacent village of Guémappe. The next few days were spent consolidating in the teeth of enemy artillery fire, which was particularly accurate because the chalk trenches held by the Battalion made very distinct aiming marks. The Battalion’s pipe band, whose members acted as stretcher-bearers, suffered particularly severe losses, especially when their aid post was hit by a shell.

During the night of 8/9 May, the Battalion was moved back into the dug-outs of the old German trenches near Wancourt, a mile south-west of Guémappe, and returned to the front line during the night of 10/11 May. Then, on the evening of 11 May 1917, Mackinnon’s Battalion took the leading part in a minor operation, having been ordered to capture the 550-yard-long front of an advanced enemy position that was known as “Tool Trench” and ran north–south immediately above the Arras–Cambrai road. At the same time, the 1/4th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers was ordered to take a defended post that was known as “Cavalry Farm” and situated just south of the road. After two days of slow bombardment, the attack was made at 20.30 hours, i.e. at dusk, and without a preliminary barrage, in order to achieve surprise. Three Companies of the Battalion took part in the attack, with ‘D’ Company on the left. The regimental history relates:

The men moved forward in two lines. Two minutes later German flares and rockets were calling for help, and within another minute the German artillery put down a heavy barrage on our front trenches. But by this time the assaulting companies were well forward, and so escaped the barrage. As they approached Tool Trench it was evident that the Germans had been badly surprised. Many of them were seen in the trench without arms or equipment, and when the Scottish closed upon it, most of the enemy had left and were running away eastward. Those who remained in the trench, mostly non-commissioned officers, were killed or captured, the Lewis Guns were rushed up and inflicted severe casualties on the fleeing enemy, and in a few minutes the Scottish were busy consolidating the ground they had won so quickly. ‘D’ Company, on the left and the highest ground, unfortunately overran its objective in the dusk. The trench here consisted chiefly of a line of shell holes and was very difficult to recognize. Before it got back into line with the other two companies, ‘D’ Company was caught by heavy machine-gun fire, and suffered many casualties, including the Company commander and senior platoon commander – Captain Mackinnon and Lieut. [Herbert Edward] Hawkins [b. c.1887 in France, d. 1917).

‘D’ Company then consolidated in a fairly good trench, having captured two heavy and four light machine-guns, three of which they turned on the enemy after persuading a German to show them how to work them. It then fought off a counter-attack using bombs and a trench mortar, and the Royal Engineers blocked the trench and wired it. The London Scottish held their objective throughout that night and the following day – their final contribution to the second phase of the Second Battle of Arras – which cost it five officers and 70 ORs killed, wounded and missing. William was killed in action near Guémappe, aged 33. He was buried in Tank Cemetery, Guémappe, Grave C.23, with the inscription: “God proved him and found him worthy for himself.” He is commemorated on the Memorial in St Columba’s Church, Albert Street, Oxford (originally the Presbyterian Chaplaincy that was founded in 1908: the Church was dedicated in 1915), on the Memorial in Inverness Town Hall, on the Memorial next to his parents’ grave in Clachan Cemetery, Kintyre Peninsula, Argyllshire, and on a plaque inside Clachan Church itself. Lieutenant Hawkins is buried next to Mackinnon, in Grave C. 24.

Not long after the battle, A.S. MacAskell, one of Mackinnon’s subalterns, who had been wounded on 10/11 May but survived the war, wrote to William’s widow:

From the 4th to the 8th when we held this part of the line we had an anxious a time as the battalion has ever experienced in the line. Owing to the intensity of the Hun artillery fire. Throughout the whole of the operations your husband was a fine example to us all, for his coolness under fire and sound judgment did much to bring ‘D’ Company through with comparatively few casualties. He looked after the comfort and welfare of the men like a father, and never spared himself on their, or on our, behalf.

On 14 June 1917, Mackinnon’s mother wrote the following letter to President Warren, thanking him for his letter of sympathy:

Our sorrow and loss are very great, but there are points of comfort of which I will be glad to tell you. William left us in full health and strength and so cheerfully that it is difficult even yet to realize that he will not return. We have been told that he did not suffer at all, and that he was reverently laid to rest in the British Cemetery near at hand, the place and spot all carefully noted. We have also heard that his work was most excellent, so much so that it was reported and we heard of it incidentally. […] We are proud to know that he did his best so nobly and unselfishly and we are very thankful that he did not experience the cruel and outrageous treatment so often meted out by the Germans to their prisoners. When we look at his dear wife and children, the grief of it all is intensified. One is so grieved to see the young so bereft and wounded. But on the other hand we are so glad to have the children – they are very dear, and such sweet comforters. There are two boys and a girl. […] Before William left, he and his wife arranged that their house in Queen’s Gate Terrace should be used as a Hospital for Officers. It was accepted by the War Office, and has been most beautifully fitted and is called the Mackinnon Hospital. Mrs William [i.e. William’s widow] is going on with this work. She has been very brave, and of course the work is a great resource. […] Of my own sorrow and loss I can scarcely write. I have been helped most wonderfully and know I will be yet. Duncan [i.e. William’s younger brother, who would be killed five months later] comes home fairly often, and sometimes for the weekend. I cannot bear to think of where he may be sent next! I have to take short views and ask for grace “just for today”. My husband keeps well, his memory not being quite good he does not always remember his great loss [–] which is perhaps merciful.

William left £85,904 (c.£4,000,000 in 2005).

The Mackinnon Memorial, Clachan Burying-Ground, Kintyre Peninsula, Argyllshire. Mackinnon’s parents are buried in the grave to the right of the Memorial

(Photo © John Blake Esq.; courtesy of John Blake Esq.)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would particularly like to acknowledge their debt to **J. Forbes Munro, Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823–1893 (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2003). This book is a fascinating and authoritative study of the Mackinnon Group’s rise to riches during the nineteenth century, and provided us with most of the material with which to sketch the life of William Mackinnon [I] and thus create a highly simplified background for our microscopic account of the lives of two younger members of the Mackinnon family (see also Duncan Mackinnon) who were killed in action in World War One. We would like to express our unreserved thanks to Professor Munro for his generosity in giving us permission to cite from his work.

** We would also like to acknowledge our debt to Alan Macdonald (the nom de plume of Bill MacCormick) for allowing us to make use of material from Pro Patria Mori: The 56th (1st London) Division at Gommecourt, 1st July 1916 (West Wickham, Bromley, Kent: Iona Books, 2008), his meticulously researched and immensely informative book on the 56th (London) Division’s attack on Gommecourt on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

*E.I. Carlyle, rev. John S. Galbraith, ‘Sir William Mackinnon, baronet (1823–1893)’, ODNB, 35 (2004), pp. 660–1.

* Lloyd (2001), pp. 106–13.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Sir William Mackinnon’ [obituary], The Times, no. 33,985 (23 June 1893), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Sir William MacKinnon, Bart.’, Argyllshire Herald (Campbeltown), no. 1,857 (24 June 1893), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sir William Mackinnon, Bart,’ The Scotsman (Edinburgh), no. 15,599 (29 June 1893), p. 4.

–– ‘The late Sir William MacKinnon, Bart.: The Funeral and Pulpit References’, ibid., no. 1,858 (1 July 1893), p. 3.

–– ‘Will of the late Sir William MacKinnon’, ibid.. no.1,859 (8 July 1893), p. 3.

A.J.A., ‘Mackinnon, Sir Wm, first baronet (1823–1893)’, DNB, Supplement vol. iii (1901), pp. 127–8.

[Anon.], ‘Capt. William Mackinnon’ [brief obituary], The Scotsman (Edinburgh), no. 23,092 (23 May 1917), p. 10.

[Anon.], Memorials of Rugbeians who fell in the Great War, vol. 5 (August 1919), unpaginated (printed for Rugby School by Philip Lee Warner [OR] of the Medici Society Ltd).

Lindsay (1925), passim, but especially p. 147.

Rugby School Register, Vol. IV (1929), p. 117.

Galbraith, John S., ‘Italy, the British East Africa Company, and the Benadir Coast, 1888–1893’, The Journal of Modern History, 42 (1970), pp. 549–63.

[Anon.], ‘Mr Duncan Mackinnon’ [obituary], The Times, no. 62,012 (14 December 1984), p. 14.

Rachel Britton, ‘Wealthy Scots, 1876–1913’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, 58, no. 137 (May 1985), pp. 78–94.

J.M. Mackenzie, ‘Essay and Reflection: On Scotland and the Empire’, The International History Review, 15, no. 4 (1993), pp. 715–21.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 31–3, 115, 131.

J. Forbes Munro, Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823–93 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer, 2003), especially pp. 15–25, 32–3, 40–6, 65–7, 86–7, 94–102, 109–16, 132–6, 151–3, 181–212, 239–58, 334–45, 451–75, 512–14.

Alan Macdonald, Pro Patria Mori: The 56th (1st London) Division at Gommecourt, 1st July 1916 (West Wickham, Bromley, Kent: Iona Books, 2008).

Nigel McCrery, Hear the Boat Sing (The History Press: Stroud, 2017).

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR 32/C3/825-827 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence: Letters concerning D. and W. Mackinnon [1917]).

Roger Hutchins, ‘The Mackinnon Brothers’ [ms. 2008].

OUA: UR 2/1/48.

ADM196/50/2.

WO95/1266.

WO95/2956.

WO374/44796.

The Papers of Duncan Mackinnon (Acc. 6168), The Archives, The National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge, Edinburgh.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘British India Steam Navigation Company’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British-India_Steam_Navigation_Company (accessed 20 June 2018).

Hector L. Mackenzie, ‘Sir William Mackinnon, Bt’, The Kintyre Antiquarian & Natural History Society Magazine, WebEdition15, March 1998: http://www.kintyremag.co.uk/1998/15/page8.html (accessed 20 June 2018).