Internees

When war was declared in August 1914 there were several thousand British nationals in Germany. Some were married to Germans and were permanent residents; others worked and lived in Germany; some were studying or on holiday; others were from British merchant ships interned in German ports or rescued from ships torpedoed by the German Navy. One class that caused problems for other internees were the pro-Germans, for example the sons and even the grandsons of Germans who had become naturalized British but had then returned to Germany. Their sons and grandsons, who had never been out of Germany, had kept their British nationality to avoid conscription in the German Army. This group of pro-Germans was eventually segregated from other internees, although many, perhaps not surprisingly, preferred to remain in the camp rather than take up the offer of freedom provided they fought for the Kaiser.[1]

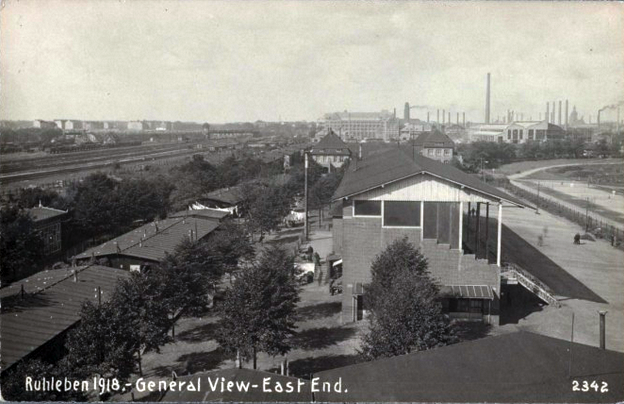

In total 5,000–10,000 British men, women and children were stranded in Germany when war was declared. Initially these internees were only required to report every three days to their local police station and women, children and men over military age or unfit to serve were allowed to go home. But after reports of the “inhuman conditions in Newbury Camp” (see Albert Victor Murray) in the German press, the German government issued an ultimatum “that unless the interned Germans were released by November 5th all Englishmen in Germany would be arrested and interned”.[2] During November–December 1914 British civilians were rounded up and interned in camps, the main one being at Ruhleben racecourse near Berlin, which housed over 4,000 British men. The location may have been inspired by the British use of Newbury racecourse as an internment camp from early September. About 5,000 British nationals were interned during the war, compared with 26,000 Germans interned in Britain.

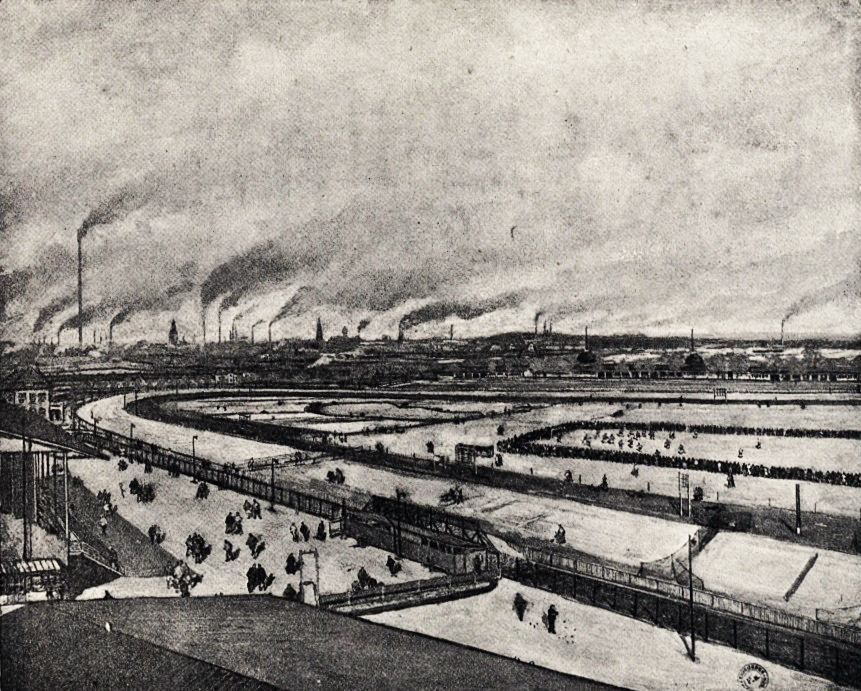

The racecourse Ruhleben (section of panorama) by Nico Jungman[3]

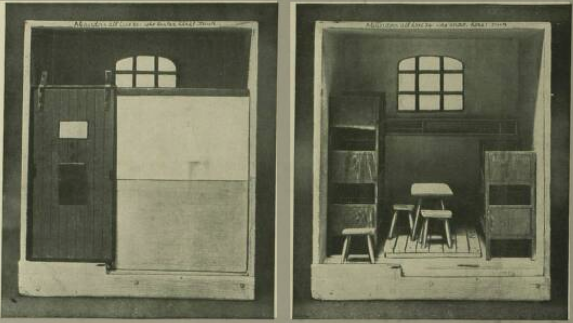

The first account in The Times of the British interned in Germany at Ruhleben is headed ‘A colony of jockeys and trainers’,[4] as these had formed a substantial part of the population of Hoppegarten, the German equivalent of Newmarket. Initially these men and others who joined them were housed in the grandstand and in 12 stables. Each stable consisted of a central passage with horseboxes on either side, with six men to a horsebox and more in the hayloft above. This unit was called a barrack and at the beginning there were 300–400 men in each barrack.

Horseboxes at Rhuleben[5]

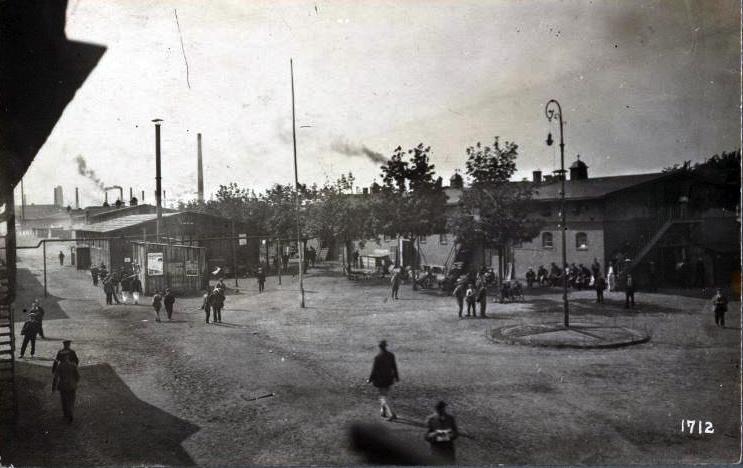

Over the four years of the camp new buildings including wooden barracks were erected and the lanes between them were given the names of London streets. In the early stages of the war the interests of British subjects in Germany were entrusted to the American ambassador, James Watson Gerard (1867–1951), who visited Ruhleben a number of times, and who by his influence and funds from both the American and British governments improved the lot of the prisoners. In a letter to the New York Times in 1918 Dr Alonzo E. Taylor (1884–1948), a medical doctor on Gerard’s staff, commented on the conditions at Ruhleben:

[I] surveyed the Ruhleben camp in 1916, […] The Ruhleben internment camp is located in a race track to the west of Berlin. Here were thrown together painters, sculptors, musicians, singers, actors, university professors and a great many business men, to whom were gradually added the crews of merchant ships and trawlers captured at sea. Here were also gamblers, jockeys and prize-fighters; and criminals from England and France who had found haven in Germany before the war. […] The quarters were crowded, dirty, inadequately heated; the roofs leaked and were never repaired; all of the equipment was of the crudest type; the men were literally herded in. […] the food conditions were entirely inadequate, both from the standpoint of quality and quantity.[6]

The American ambassador wrote about Alonzo Taylor’s visit to Ruhleben:

Professor Alonzo E. Taylor of the University of Pennsylvania, a food expert, […] joined my staff in 1916 and proved most efficient and fearless inspector(s) of prison camps. Dr. Taylor could use the terms calories, proteins, etc., as readily as German experts and at a greater rate of speed. His report showing that the official diet of the prisoners in Ruhleben was a starvation diet incensed the German authorities to such fury that they forbade him to revisit Ruhleben.[7]

Ruhleben camp with the racecourse to the right and the grandstand in the centre (With permission, Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library)

Trafalgar Square looking to YMCA, Ruhleben internment camp (With permission, Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library)

When the USA entered the war the Netherlands legation in Berlin took over the responsibility for overseeing the welfare of the British prisoners in Ruhleben.

Several books[8] were published during and shortly after the war by men who had been interned in Ruhleben, describing conditions in the camp. They all agree that the conditions, especially in the first few months, were particularly bad, more through unpreparedness and incompetence than from malice, but that things did improve when the running of the camp was largely in the hands of the internees. Each barrack elected a captain and it was the Committee of Barrack Captains who essentially ran the camp.

Baron von Taube, Count von Schwerin, Rittmeister von Brocken, and Count von Hochberg, Deputy Commandant of the staff at Ruhleben 1915 (From Israel Cohen’s The Ruhleben Prison Camp)

The main role of the Germans was to enforce internment. The inadequate supply of food provided by the Germans was supplemented by food parcels sent from home and by families and various charitable organizations. Additionally, the internees could buy food and other necessities, such as knives and forks, locally. Many, especially those in the “millionaires’ barrack” (see Mark Kearley), had come into the camp with money or had money sent from home, but others had nothing, and the Barracks Committee raised money from the better off to help the less fortunate. Later the British government made a weekly loan to destitute internees to buy food etc., the money to be paid back after they returned home. This is not the place to discuss details of life in Ruhleben, which can be obtained from any one of the books referred to in the footnotes. Israel Cohen’s (1879–1961) The Ruhleben Prison Camp: A Record of Nineteen Months’ Internment is helpful and more objective than some of the others. Cohen had lived in Germany for several years working as director of the English department of the Zionist Central Office in Cologne and later in Berlin, and while in Berlin he was a correspondent for The Times and Manchester Guardian. Although, unlike many, he was not interned for the duration of the war, his book describes the development of camp life; how basic problems such as bad food and medical and dental treatment were to a certain extent overcome; and it allows us to imagine what living in Ruhleben was like.

Camp concerts and theatricals are familiar to anyone who has seen films or read about World War Two prisoner of war camps; what was perhaps exceptional at Ruhleben was the extent to which they used captive expertise to develop a series of high-level courses in both the arts and the sciences. These were given by, amongst others: Sir James Chadwick (1891–1974), who later won the Nobel prize for physics and was studying with Hans Geiger (1882–1945) in Berlin when he was interned; Edgar Bainton (1880–1956), the composer, was interned while visiting the Bayreuth Festival; the historian and spymaster Sir John Masterman was interned while an exchange lecturer at the University of Freiburg; the portraitist Charles Mendelssohn Horsfall (1865–1942), a distant cousin of Paul Victor Mendelssohn Benecke (1868–1944), Fellow of Magdalen, through his mother Alexandrine Mendelssohn; and the artist Nicholas Wilhelm Jungmann (1872–1936), who while interned executed a number of paintings of Ruhleben and the life of the internees.

Physical Laboratory, Ruhleben (From Israel Cohen’s The Ruhleben Prison Camp)

The art studio, Ruhleben (From Israel Cohen’s The Ruhleben Prison Camp)

Ruhleben Prisoners Lining up for Bacon Ration at Christmas,[9] by Nico Jungmann; the original work is in the Imperial War Museum

Efforts were made by, amongst others, the Ruhleben Prisoners’ Release Committee and individual members of both Houses of Parliament – including Mark Kearley’s father, Viscount Devonport – to support the exchange of British prisoners interned in Germany for the German prisoners interned in the UK. However, the government refused to countenance such an exchange, which had been proposed by the German government. Robert Cecil (1864–1958) (later 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood), Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, stated the government’s position in July 1916: “[It] cannot accept the proposal to repatriate all the Germans interned in this country in exchange for the British civilians interned in Germany, since that would be to send back some 26,000 Germans in exchange for only 4,000 British.”[10] This was seen by the British government as giving the Germans another division and merely getting a brigade in return. A number of elderly and sick prisoners were repatriated on a one-for-one basis, but most were interned until the end of the war.

Towards the end of the war, due to the food parcels arriving at Ruhleben and the British blockade of Germany, the prisoners had a much better diet than most Berliners – to the extent that they took the precaution of hiding food in case the camp was raided.[11] On 8 November 1918, as part of the revolution sweeping Berlin and Germany at that time, the camp guards deposed their officers and formed a soldiers’ council, which was well disposed towards the prisoners. The Armistice agreement was signed at 05.00 on 11 November 1918, and Clause 10 of the “Military Clauses on the Western Front” starts “The immediate repatriation without reciprocity, according to detailed conditions which shall be fixed, of all Allied and United States prisoners of war, including persons under trial or convicted.”[12] All prisoners had left the camp well before the end of November, with the bulk of them arriving in the UK before the end of the month. The first party of 600 arrived in Leith from Denmark on 28 November.[13]

Three Magdalen men were interned in Ruhleben; had they not been it is likely that one or more would have been killed at the front.

—

[1] Matthew Stibbe, British Civilian Internees in Germany; The Ruhleben Camp, 1914–18 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), pp. 124–5.

[2] Israel Cohen, The Ruhleben Prison Camp: A Record of Nineteen Months’ Internment (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1917), p. 22.

[3] Nico Jungmann, ‘My Life at Ruhleben’, The Studio, 73 (1918) p. 92.

[4] The Times, no. 40,691 (9 November 1914), p. 7.

[5] Illustrated London News, no. 4,005 (22 January 1916) p. 21.

[6] A.E. Taylor ‘Enemy Artists in Germany’, New York Times (13 April 1918), p. 14.

[7] James W. Gerard, My Four Years in Germany (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1917), Chapter X. Also available on-line: http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/memoir/Gerard/4yrs3.htm#ch9 (accessed 22 April 2022).

[8] [Anon.], In the Hands of the Huns: Being Reminiscences of a British Civil Prisoner of War 1914–1915 (London: Simpkin Marshall Hamilton Kent & Co. Ltd, 1916).

Geoffrey Pike, To Ruhleben – and Back: A Great Adventure in Three Phases (London: Constable and Company Ltd, 1916).

Right Rev. Herbert Bury, My Visit to Ruhleben (London: A.R. Mowbray & Co. Ltd, 1917).

Douglas Sladen, ed., In Ruhleben: Letters from a Prisoner to his Mother (London: Hurst and Blackett Ltd, 1917).

Joseph Powell [Captain of the Camp] and Francis Gribble, The History of Ruhleben: A Record of British Organisation in a Prison Camp in Germany (London: W. Collins Sons & Company Ltd, 1919).

Israel Cohen, The Ruhleben Prison Camp: A Record of Nineteen Months’ Internment (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1917).

For a more recent account see Matthew Stibbe, British Civilian Internees in Germany: The Ruhleben Camp, 1914–1918 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013).

[9] Nico Jungmann, ‘My Life at Ruhleben’, The Studio, 73 (1918), p. 95.

[10] Reply of German Government, Hansard, HC Deb. vol. 84, cols 512–4 (13 July 1916).

[11] Matthew Stibbe, British Civilian Internment in Germany; The Ruhleben camp, 1914–18 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 183.

[12] The Times, no. 41,945 (12 November 1918), p. 8.

[13] The Times, no. 41,960 (29 November 1918), p. 5.

-

Barrett, Robert Guy Lionel (1884-1974)

-

Kearley, Hon. Mark Hudson (1895-1974)

-

Shiell, William George (1890-1974)