Albert Victor Murray (1890-1967)

Albert Victor Murray in Magdalen (c.1911)[1]

(Albert) Victor Murray[2] was born in Choppington, Northumberland,[3] on 1 September 1890. In 1915 he wrote ‘In No Strange Land’,[4] a recollection of his friendship with Kenneth James Campbell (1891–1915), his contemporary at Magdalen, who served as Machine-Gun Officer with the 9th Battalion the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.[5] Campbell was killed in France on 10 May 1915 at Hooge, on the Menin Road, just east of Ypres, while single-handedly operating his machine-gun from a wheelbarrow amid a “hail of shells”. Had his Commanding Officer not been killed during the same action, Campbell’s extreme bravery might have won him the Victoria Cross.

Kenneth James Campbell (1891-1915) (Courtesy of Magdalen College)

In this recollection, Murray contrasts his upbringing with that of Campbell and describes his father, John Ridley Murray (1861–1922), as follows:

My father was a greengrocer – and very good one too, although he had tried various things before he came to that. He was a grocer originally, – “master grocer” as he is described on my birth certificate, not that the adjective made much difference in the Northumbrian mining village where we lived. He was a modest man and inoffensive, and there are other men to whom that type of quietness is more galling than downright aggressiveness, and my father was removed from his business and had to find something new to do.

He started to manufacture lemonade. He knew nothing about this kind of thing but he learned it as he went along and became good at this too. Here he had to endure a mild measure of publicity and to condone certain artifices which were doubtful in his eyes. His lemonade was described as “celebrated” before the public had had sight of a single bottle. All went well until he was enticed to remove his growing business to a seaside resort (Berwick-upon-Tweed) where presumably people would drink more lemonade. At great cost he got himself established, and but for one thing might again have done well. That one thing was water. It had not been previously tested and it was now found to be useless for aeration. So my father had to leave all that and he became a greengrocer, a less adventurous but more certain trade.[6]

Quite a contrast to Campbell’s home in Scotland “on the edge of a lovely salt-water loch […] The garden was the loveliest I have ever seen, nothing but roses, three hundred and sixty-five varieties of them.”[7]

Murray wrote an account of his early life which was published in 1992 as A Northumbrian Methodist Childhood. His paternal grandfather, Ridley Murray (1826–92), was a coal miner; but it was his maternal grandfather, Robert Lawther (1843–99), the father of his mother, Elizabeth (b. 1868), who made a lasting impression on Murray even though he died when Murray was only eight. Robert Lawther had started in the mines, but ill-health compelled him to take on lighter surface work: running a newsagent’s, becoming a “citizen’s advice bureau”, a councillor and magistrate, and a Primitive Methodist lay preacher. Both families lived in Scotland Gate, a mining town near Morpeth in Northumberland which had a population of about 5,000 at the time of Murray’s birth. This was anything but the usual background of a Magdalen undergraduate in the Edwardian period, and Murray gives much credit to his local Church School from where he won a scholarship to Morpeth Grammar School and from there an Exhibition at Magdalen, where he matriculated in 1909. Despite his untypical background, Murray seems to have settled well into what must have been to him a very “strange land”, and his signature appears on an autographed copy of the menu for the dinner celebrating the College going Head of the River in Torpids (rowing races) of February 1913. Other signatories include Edward Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII who was an undergraduate at Magdalen 1912–14) and T[homas] Herbert Warren (Magdalen’s President from 1895 to 1928). But of the c.60 junior members of Magdalen who signed the menu, at least six would be killed in the war[8]. Despite his background, he made many good friends during his time at Oxford, as his war-time correspondence testifies.

Magdalen College Boat Club menu (February 1913); the Prince of Wales’s signature is bottom right on the centre panel and Victor Murray’s is second down on the left in the right-hand panel[9]

Murray read Modern History and initially had difficulty in coping with independent study,

but K. [Kenneth Campbell] did it all so easily […] he tackled Stubbs’ Charters[10] with a nonchalance that amazed me. Soon he felt he ought to take me in hand, and he did so. We worked a good deal in each other’s rooms and he discussed the problems as we went along.[11]

They both read for the special paper ‘Italian special period, 1498–1509’, and the wealthy Campbell went to Italy to “study the special paper on the spot”, but of course Murray could not go. But “when he came back, we used Baedeker[12] as a text-book and K. went over the ground with me until I knew Florence and Venice almost as well as if I had been there myself.”[13]

In a long letter[14] to Murray from the front, written about a month before he was killed, Kenneth Campbell wrote of his life at Magdalen and described something of his experiences and fears of front-line work. He wrote of his men, expressing a view still recognized by some, saying: “The labouring classes have been awfully spoilt by a mixture of grandmotherly legislation and […] Trades Unionism” – and this from someone who had been brought up on the edge of a lovely salt-water loch. But the general tenor of his letters would not have made Murray happy, coming from a disturbed young man whose change of circumstances had upset the order of his life and his religion.

Despite having a Primitive Methodist preacher as a grandfather, Murray did not have a very religious upbringing, and claimed: “Neither my father nor my mother were very religious people.”[15] But various letters to him suggest that he and his close friends at Oxford were brought together by a strong Christian belief, which had been instilled into him when a child at the Sunday School of the Scotland Gate Primitive Methodist Chapel, where he became assistant leader of the Junior Christian Endeavour and in this capacity wrote and produced an operetta in 1908 entitled A Little Pilgrim’s Progress.[16]

Murray’s interest in the stage continued at Oxford. At the end of June 1916 he appeared in a traditional “kitchen stair” play in what was later to be known as the Oscar Wilde Rooms. There were a number of short plays produced by his friend John Brett Langstaff[17]. “Our original melodrama was finally titled The Winning Stroke patterned on Thomas Hardy’s The Dynasts and adding to our cast Stod Hoffman[18], Charles Jury[19], Victor Murray and Purdon Hough[20].”[21] There was a collection in aid of the Serbian refugees in Oxford. Among the audience were Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873–1938)[22], John Masefield (1878–1967)[23] and the President, Sir Herbert Warren.

Another of Victor Murray’s friends, Kenneth Desmond Murray (1892–1915), was at Westminster School before going to Christ Church, Oxford. He served as a Second Lieutenant in the 9th Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment, and was killed near Hulluch during the Battle of Loos on 19 September 1915 (no known grave: commemorated on the Loos Memorial, panels 65–7). On 27 December 1914, five days after receiving his commission, he wrote to Murray, transferring the account book of the Oxford University Christian Union to him and instructing him on how to deal with the Union’s finances. He then went on to discuss a letter which he had received from Murray and which no longer exists, but at whose contents it is possible to make a reasonable guess. Victor Murray seems to have had some sort of breakdown – possibly from agonizing over his pacifism when so many of his friends had joined up, even though at that time he was under no legal obligation to enlist. And in his letter to Kenneth Murray he must have revealed both the agony of his position and his justification of it. As a result, Kenneth Murray did his best to understand Murray’s arguments – but failed:

I find it very hard to answer your letter. I’ve read it two or three times and I get on all right till we come to the anima naturaliter Christiana, Vergil, Jeremiah and so on. There I confess I am at sea. The difficulty I think is partly this, that you are seeking to solve a problem which hasn’t presented itself at all to many people. Many of us I think have not experienced what you call “the sorrow and agony of it, that the war should be at all”. Of course we all agree that the war is a deadly thing, but you mean something more than that. You say again “The more of the infinite we pack into this finite shell of ours, the more it is going to hurt.” Perhaps this is the explanation, that your spiritual susceptibilities are finer than ours (don’t think I’m being sarcastic, I’m perfectly serious), and so you feel a difficulty where we find none, or if you like you feel a knife digging into you where we feel only a pin prick. […] I can’t see what you’re driving at […] I agree of course entirely in the Fellowship of the Federation, the need of prayer as a unifying element and “the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem”. […] You remember you promised to go and see a doctor as soon as you got home, be sure you do it won’t you. I’m not at all sure you ought to be reading hundreds of letters about the war. I believe it makes you worry which is bad for you. At any rate see what he says.[24]

In line with the above suppositions, Kenneth Murray subsequently began a letter dated 2 May 1915 as follows: “I’m awfully sorry to hear you’ve broken down again. I hope it isn’t really bad this time and that you soon got off the jigsaws.”

Victor Murray had certainly had health problems while an undergraduate at Magdalen, and a photograph of him that is dated June 1910 and preserved in the College’s archives shows him recovering from an unspecified complaint in the Acland Hospital. According to one report, the complaint may have been a psychological condition that was caused by overwork, and in 1911 the College sent him to Germany for a long holiday during which he spent time in Tübingen and Marburg. So if the stress of overwork was the cause of that illness, then it is perhaps unsurprising if stress due to his wartime responsibilities and feelings about the war caused it to recur.

“Oxford: In hospital in the Acland Home, June 1910” (Courtesy of Magdalen College)

In other letters, Kenneth Murray discussed the war and meeting common acquaintances from Oxford. These included Philip Howson Pye-Smith (1896–1917) of Magdalen who was killed by a shell on Telegraph Hill, just east of Arras, on 15 May 1917 while serving as a Second Lieutenant with the 11th (Service) Battalion (Pioneers) of the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, and Mansel-Carey – probably David Vernon (1895–1990) rather than his brother Spenser Lort Mansel-Carey (1893–1916), who died of wounds in No. 5 CCS, Corbie, east of Arras, on 24 February 1916 while serving as a Lieutenant with the 8th Service Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment. Mansel-Carey was on active service in France when the letter was written at Worthing, Sussex. But the final letter in this series of seven came not from Kenneth Murray but from his sister Helen, thanking Victor Murray for the kind letter he had written when Kenneth was posted missing.

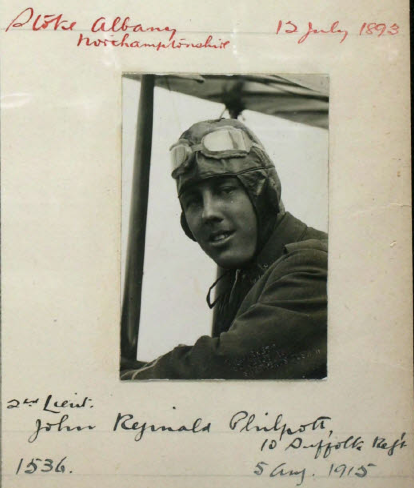

A further letter which alluded to Murray’s illness came from another of Murray’s Magdalen friends – John Reginald (“Rex”) Philpott (1893–1918), the son of Canon John Nigel Philpott (1859–1932). Rex was in the Royal Flying Corps / Royal Air Force, won an MC and died on 15 January 1918 as a prisoner of war of the Turks in the camp at Afyon Kara Hissar, western Turkey. He wrote the letter in August 1915 from Shoreham, Sussex, where he was enjoying his flying training, and signed it “Your most loving friend Rex”.[25] It says: “Your account of yourself distresses me very much, old boy. I wish you wouldn’t talk like that. Of course you’ll get well again […] I do wish I could say or do something because I feel such a swine to be more or less enjoying myself here at the government’s expense.”

John Reginald (“Rex”) Philpott; photo taken on 5 August 1915 when he was learning to fly at Stoke Albany, Northamptonshire

Yet another of Murray’s correspondents was Geoffrey Harold Woolley (1892–1968), VC, OBE, MC, a former undergraduate of Queen’s College, Oxford, who returned to Oxford after the war to read Theology and was ordained in 1920. Writing on 15 May 1915, Woolley reminded Murray of kinder days: “a moonlight punt down the Cher by Magdalen, or a voyage up to Wytham to eat strawberries at the Inn, and nearly upset the boat in picking some iris by the bank”.[26]

Geoffrey Harold Woolley, VC (1892-1968)

Less than a week after writing the letter, Woolley was awarded the Victoria Cross. The citation reads:

For most conspicuous bravery on “Hill 60” during the night of 20th–21st April, 1915. Although the only officer on the hill at the time, and with very few men, he successfully resisted all attacks on his trench, and continued throwing bombs and encouraging his men until relieved. His trench during all this time was being heavily shelled and bombed and was subjected to heavy machinegun fire by the enemy.[27]

The hand-to-hand fighting for the possession of this “high point” was intense and brutal, and some two weeks later 90 men were killed on “Hill 60” in one of the first gas attacks on the Western Front. Woolley was the first Territorial Army officer to be awarded the Victoria Cross. But Woolley, like all of Murray’s friends, had doubts and wrote in the letter of 15 May that he was “too sensitive and imaginative to be a soldier”.

But the most illuminating collection of letters is of those written by Frederick Raymond Charlesworth (1894–1918), the son of Basil Charlesworth (1866–1925) (who had also studied at Magdalen and was by 1914 a stockbroker living at Gunton Hall, Lowestoft).[28] Raymond went to Eton and matriculated at Magdalen in 1912, some three years after Murray, though they overlapped for a year. Charlesworth’s five extant letters date from March 1915, just as he was about to enlist, to January 1918, and are important because they are the only extant letters that cover the period when Murray was registered as a conscientious objector.

Frederick Raymond Charlesworth (1894-1918) (Photo Courtesy of Magdalen College Archives)

Not surprisingly, the letters say much more about Charlesworth than they do about Murray. Nevertheless, they emphasize just how popular Murray was and what an extensive network of friends he had. In a letter of 19 March 1915, Charlesworth hopes that Rex Philpott “has not been indulging in any of his nocturnal expeditions with this new wound it might make things serious as you say”, and in a letter of 1 April 1915 that was written just after he had joined the Montgomeryshire Yeomanry Charlesworth wrote: “I have apparently taken the irrevocable step and booked my ticket to hell”; on 29 June 1915 he described visiting Alexander Bowhill (1893–1984; Magdalen 1912–14) at Hunstanton, where Bowhill was stationed with the Lovat Scouts from 15 April to 21 August 1915 in order to repel any invasion. In letters dated March 1917 and 8 January 1918 Charlesworth again refers to Graham.

At this time Murray must have been worrying about friends, for Charlesworth wrote on 1 April 1915 “Don’t talk bilge about life being isolated because you have far more friends than most people and probably more than you realize” but, of course, most of them were serving in the forces. And in June 1918, possibly trying to reassure Murray: “You know I don’t believe there’s any one I know who has as many friends as you have, but they can’t help it.” But what is most striking about these letters and may have caused Murray the most pain is the extent to which Charlesworth was torn between his Christian beliefs and pacifism on the one hand, and his feeling of patriotic duty on the other. It is clear that he did not discuss this painful rift of loyalties either at home or with his fellow officers, and after his death his father was very pleased indeed to receive a letter in which President Warren described him simply as “truly a Knight of God”.[29]

In an early letter, dated 19 March 1915, Charlesworth had written: “I have taken steps to join this most Christian game of organized murder and suicide to say nothing of the destructive and wasteful habit of destroying property etc.” And six weeks later, on 1 June 1915, he followed up earlier comments with another outburst of anger and frustration: “Really I think the world has gone mad, or is it the beginning of the end as many people think? It seems too tragic that men cannot enjoy this beautiful world without blowing each other to pieces and with what object?” Finally, on 29 June 1915, he declared that he was “now a convinced pacifist”, adding “but not a word or I’ll be shot at dawn”.

One suspects that Charlesworth’s feelings mirrored Murray’s to a significant extent. Nevertheless, the two men managed to resolve their dilemmas in different ways, for in his letter of 19 March 1915 Charlesworth had also written:

You know I really can’t make the business out at all – I am absolutely convinced by Maude Royden[30] and then I go and see and talk to all these magnificent men who are going to fight for the safety of their homes and mothers and sisters […] and the appeal of such splendid self-sacrifice seems irresistible – how can it be wrong?

Another of Murray’s Oxford correspondents was James Saumarez Mann (1893–1920), a Scholar at Balliol who had been persuaded by Murray to become President of the Christian Union at Oxford as from Easter 1914.[31] Mann was wounded in the trenches in 1915 while serving with the 6th Battalion of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment). In a letter that he wrote to Murray from a Red Cross Hospital in Rouen on 26 September 1915, he contrasted his own “several months of convalescence” with the situation of his “beloved platoon wintering in the trenches”, and went on to say: “It is the limit when my family see in [my wound] the hand of Providence. I fume with rage and could almost wish to get killed, to spite them later on. I’m afraid I shall never preside over the CU again, but more of that anon”[32] – another example of the strain being felt by his friends at the front which must have caused Murray more pain. During his convalescence, Mann learnt Sanskrit: he also learnt Arabic and after the war he was attached to the Indian Political Department of the Colonial Service as a Political Officer with the rank of Captain. During the Iraq Rebellion of 1920, he was shot by a sniper on 22 July and buried in Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery.

James Sumarez Mann (1893-1920), convalescing at Somerville College (3rd Southern General Hospital) (Photo courtesy of Balliol College)

Another of Murray’s close friends was Kenneth Charles Goodyear,[33] who enlisted as a Private in the Royal Army Medical Corps and was killed in action at Vermelles on 28 September 1915. At the time of the 1911 Census, Murray and Goodyear were staying together at the Lyn Valley Hotel in Lynmouth, Hampshire, and although no letters from Goodyear to Murray have survived, he must have been as close to Murray as Kenneth Campbell, since Murray commemorated them both on the fly-leaf of his Bible on 17 December 1915:

The fly-leaf of Murray’s Bible dated 17 December 1915: “To the Memory of K.J.C. and K.C.G. killed in action, 1915, who endured the Cross despising the glory and are now set down on the right hand of GOD.”

(Courtesy of John Murray, Victor’s son)

In December 1914 Murray became Secretary of the Oxford Students’ Christian Union and was later appointed Secretary of the Student Christian Movement, at that time the largest student organization in the country and a forerunner of both the National Union of Students and the World University Service. Although it was clearly painful for him to compare his position at home with that of his friends at the front, Murray was able to pursue his not inconsiderable duties until the Conscription Act came into force on 27 February 1916; on 25 February 1916 a copy of Army form W.3236 was sent to his home in the pit village of Willington, Co. Durham. It stated:

You are hereby warned that you will be required to join for service with the colours on the 11th March 1916. You should therefore present yourself at Drill Hall, B[isho]p Auckland, on the above date no later than 9.30 am o’clock, bringing this paper with you.

But as Murray was at that time living and working in Oxford, he chose to appear before the Oxford Local Tribunal on 3 March 1916. The Tribunal was chaired by the Mayor (C.M. Vincent[34]).

Albert Victor Murray, 25, 3, Grove Street, formerly an Exhibitioner of Magdalen College, student (examination in March) General Secretary of the Oxford (University) Student Christian Union, and prospective Secretary of the Student Christian Movement of Great Britain and Ireland, claimed absolute exemption. He stated that he had a conscientious objection to war and to any service directly incident to war. He was preparing for ministerial and pastoral work in the future, which would not only be interrupted, but for conscientious reasons would be made impossible to do if any kind of war service was undertaken. Applicant enclosed letters from Arthur S. Peake[35], The Rev. B. H. Streeter[36] (a circular sent with this letter showed that whereas membership of the Oxford Student Christian Union was 220 at the end of Summer Term 1913, at the beginning of Summer Term 1914 it had advanced to 412), from the Rev. Tissington Tatlow[37], and the President of Magdalen, Sir Herbert Warren, who stated that he had reason to believe the applicant’s objections might be considered as coming from a conscientious person. Dr. Selbie[38] wrote that he was convinced of the bona-fides of the applicant as a conscientious objector to military service, and he was preparing for work which might be considered of national importance.

The Town clerk: Are you a theological student?

The applicant replied that he had a year at Mansfield [College, Oxford]. He was doing theological work in Mansfield and Christian Union work. It became impossible to do the two, and he temporarily gave up the theological course in Mansfield intending to back to Mansfield afterwards.

The Mayor: You are a B.A. are you not?

Yes.

The Town Clerk: Do you intend to become a minister?

Yes.

You are not a member of a theological college at present?

I am only an Honorary member of Mansfield.

Lieut. Baldry: I take it the applicant cannot be exempted as a theological student?

The Town Clerk: No. I gather that. That is why I put the question.

The Mayor: You will be exempted from combatant service.

The applicant said if a man made out his claim then he had a right to absolute exemption.

The Town Clerk: If the Tribunal are satisfied there are exceptional grounds in your case you would be entitled to an absolute exemption.

The Applicant said surely there was the ground that he was doing a particular sort of work, and to engage in any war service would make it quite impossible to do it. Did he understand it was the intention of the Tribunal that he should immediately engage in some non-combatant service?

The Mayor: That depends on when you are called up by the Military Authorities.

Applicant: One has the right to appeal. I suppose?

The Mayor: Certainly.[39]

The letters of support for Murray are not available, but it is perhaps surprising that he sought support from Burnett Hillman Streeter, who in 1915 had published War, This War and the Sermon on the Mount, a book unlikely to give succour to a conscientious objector. Streeter writes:

“Love your enemies,” verily and indeed – but it is also written, “thou shalt love thy neighbour.” Take as literally as you like the words, “If a man smite thee on the right cheek, turn to him the other also” – yet there is one thing they cannot mean – “If a man smite thy sister on the cheek look the other way.” If a wanton injury is threatened to one weaker than myself and I have power to prevent that injury, then, if I fail to exercise that power, I become morally a particeps criminis, and no casuistry can absolve me from complicity in the injury itself. No act is more essentially Christlike than the deliverance of the oppressed. Even if in a particular case the threatened party would be willing in the name of Christ to submit to the injury, it is no less my duty to prevent the wrong being done – if possible by persuasion, if not by force.[40]

Presumably Murray needed Streeter as Senior Treasurer of the Oxford Student Christian Union to emphasize his importance to the Union. Murray did keep a private letter from Arthur Peake[41] written a few days after the meeting of the Tribunal. While Peake wrote to the Tribunal in support of Murray, he did not always show the same degree of support in private, and on 11 March 1916 he wrote to Murray as follows:

I don’t agree with your point about vocation. I see how you might feel that conscientious objection forbad[e] you assisting in any way in the war, so that RAMC work might be ruled out. YMCA work you would not, I expect, be released for. You would be unable to fulfil your vocation in prison. Our country has some right to our service, and in a time of great strain some right to a say in the form our service should take, provided conscience is not violated, and if it is made impossible for you to carry out your vocation[,] then why not take the second best?[42]

As can be seen, Murray had an extensive network of influential friends and acquaintances which he had almost certainly made by being an active Christian at Oxford, and he obviously made use of them after his failure to obtain absolute exemption. While his letters have not survived we can guess their content from the replies he received, and one good example is a letter that he received from J.H. Whitley,[43] the Liberal MP for Halifax (1900–28) and future Speaker of the House of Commons (1921–28), dated 25 March 1916, i.e. about two weeks after Murray had appeared before the Local Tribunal. Whitley wrote:

I send you a Hansard to show that at last things were moving the right way; also I have been pressing all I can to get your further appeal allowed in view of the Govt statement of the new Comtee [44] to decide on alternative services, on it I hear the B[isho]p of Oxford and T. E. Harvey[45] are to serve.

Murray’s connection with Whitley becomes clear later on in the letter when Whitley refers to “Per”, his son Percival Nathan Whitley (1893–1956) of New College, Oxford. In 1916 Percival Whitley suffered considerable personal abuse and narrowly avoided imprisonment as a conscientious objector, but was twice mentioned in dispatches during the World War One for his distinguished voluntary service with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).[46]

Murray also discussed his position with the Bishop of Oxford, Charles Gore[47], and on 26 February, i.e. before the hearing of the Local Tribunal, Gore asked him: “Do let me know how the tribunal treated you.”[48] But although he was one of the few speakers in the House of Lords who spoke against the harsh treatment of conscientious objectors, Gore was not wholly sympathetic towards Murray’s plight and on 4 March 1916, i.e. after the result of the Local Tribunal, he wrote a second letter to Murray in which he said:

I deeply regretted the measure of compulsory service, but I think it was necessary, and that being so, I think that the Tribunals will have to be somewhat stern, or all sorts and kinds of persons would secure exemption. […] Then as regards conscientious scruples, I know that yours are perfectly genuine, but I cannot say that I share them. […] From the point of view of the Student Union, of course if you claimed exemption on the ground of conscientious objections, you will make it very clear that your objections are not shared by the Union. I wish I could write more sympathetically. I will pray. Yours affly Oxon.[49]

So what were Murray’s grounds for applying for absolute exemption – which did not wholly convince either Arthur Peake or the Bishop of Oxford? In the first paragraph of a long hand-written letter in which he outlined his case to the Oxfordshire Appeal Tribunal (see below), he stated the grounds for his conscientious objection. In the rest of the letter he discussed the importance of the Student Christian Movement and the Christian Union, in both of which he was heavily involved and because of which he was not prepared to join the Friends’ Ambulance Unit or the Young Men’s Christian Association.

Gentlemen.

I am asking for absolute exemption instead of exemption from combatant duties only, because the distinction between combatant and non-combatant service seems to me to be largely a distinction without a difference. There is a cleavage of opinion of course, about such a service as that of the R.A.M.C., but in so far as my objection is neither a political one nor a matter of expediency, I can only urge my obligation to follow what I feel and know to be the will of God for me in this question, even though the results of such a position may seem to many people to be illogical and unsound. While therefore I myself believe that such a conscientious objection can also be justified on grounds of reason, it is not primarily on those grounds that I base my claim. Wise or foolish, I can but be loyal to that condition which lies deepest within me, and to which I have come in no spirit of faction, but through prayer, thought and service.[50]

Murray appealed and in its edition of Friday 14 April 1916, the Oxford Chronicle reported on Murray’s appearance before the Oxfordshire Appeal Tribunal. This was the second sitting of the Tribunal and very few decisions were taken because the chairman Mr Francis Fitzgerald and three other members from Banbury could not attend because of “inclement weather” and so Dr Hugh Hall took the chair. The report on the Tribunal is given here in full to allow Murray’s case to be seen. It is interesting to note that, like Cole, he seems to be making two cases: the first based on his conscience, the second on the work he was doing.

OBJECTION TO WAR ALTOGETHER

Albert Victor Murray (aged 25) 3, Grove Street, Oxford, formerly an Exhibitioner of Magdalen College, general secretary of the Oxford University Students’ Christian Union, and a prospective secretary of the Student Movement of Great Britain and Ireland, had claimed absolute exemption on conscientious grounds, but was granted exemption from combatant service and appealed against that decision.

In reply to the Chairman, the appellant said he considered his present occupation was one of national importance. As to his conscientious objection, he objected to war altogether, and if in the organisation of war there were some forms of service which were called combatant and non-combatant it did not really affect the objection. He did not object to fighting because it was killing people, but he objected to the whole business of war entirely as the very negation of the Christian spirit, and therefore anything that was organised with a view to that, even if it was along the lines of service which in all other ways was helpful to humanity because of its organisation, he could not accept.

The Chairman: Don’t you draw any distinction between a defensive and an offensive war? – No.

Supposing this country was overwhelmed like Belgium. You would take it lying down if a wave of invasion went over the country, ruining property and women and children: you would still hold you had no right to resist oppression? – I think one would resist oppression but not by war. I am not standing aside in this war; I am not holding a negative position. In the atonement of Jesus Christ there is a principle which is greater and stronger than any military principle.

In reply to further questions, witness said he objected to being under the military machine because the military spirit was the negation of the Christian spirit. If the war went on for another twelve months there might be a more stringent Military Service act which would say to those who had accepted non-combatant service the need had become more urgent, could they not do combatant work?

The Chairman said that was anticipating the future. He was running in front of his conscience and anticipating something that might never happen.

Appellant: Conscience is the attitude which can see things far off.

The Chairman said he thought the appellant would do well to look round the world as it was and see what a terrible danger the country would be in from aggression and the invasion of a most blood thirsty type of people if his views were adopted.

Appellant pointed out that conscience was not confined within national barriers and the same objection to war was being made in Germany. He was connected with the Christian Student Movement and in connection with that he would like to read the following: “We feel that we deserve some real consideration in view of the fact that it was our members in colleges who were in nearly every instance among the first to offer their services to the King when the war broke out. A census taken by us three months after the outbreak of war showed that in the English universities an average of 55 per cent. of the students had joined the forces, while of our numbers amongst them 66 per cent. had joined. This movement had 10,000 members in British colleges when the war broke out. In almost every college we have lost all our leaders, and have replaced them by men under military age or physically unfit for military service, in some cases by medical students or men making munitions. The loss of leaders makes it imperative for us to keep a travelling secretary steadily at work, or else our branches would be liable to lapse in many places. In the student field of Great Britain there are still between 12,000 and 15,000 students in college. In the new universities the number of men under age and physically unfit is very large, so there is plenty of work to be done. We have not even suggested to any man of military age who is serving that he should consider the claims of our work: secretaries and clerks have been instantly set free at the call of the country, and we would not ask for Mr. Murray were it not that we recognise his position is such that he is not available for military service.” Applicant added that he would like to point out that it was spiritual work in which he was engaged. He had a letter from a major of the O. and B. L.I. at Salonika who thought that he should remain at his work in Oxford.

Captain Bailey: Supposing you were taken ill what would happen to the work? – It would not go on.

That would happen if you joined the army?- Yes.

Decision in this case was postponed.[51]

The letter supporting Murray from a serving officer was sent by Major Cordy Wheeler of the 7th Battalion the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry writing from the Salonika Army on 12 March 1916[52], too late for Murray’s first Tribunal appearance but available by the time of the Appeal Tribunal. Major (later Colonel) Cordy Wheeler, DSO[53] (1884–1972), was a schoolmaster and part-time theological student at the time of the 1911 Census. He matriculated as a member of Keble College in 1911 and graduated with a degree in Theology in 1914. Wheeler and Murray presumably met through the Student Movement. Wheeler wrote: “I am only too glad to support his [Murray’s] claim for exemption from military service. My reason for so doing is that Mr Murray is singularly fitted in every way to carry on a work which is of quite unique value to Church and State.” Whether or not Murray presented this letter to the appeal Tribunal, it had no effect.

At the meeting of the Local Tribunal on Monday 1 May 1916, Murray’s application to change his previously granted exemption from combatant service was heard. It was stated that since the date of the original certificate, arrangements had been made for him to do work of national importance that was acceptable to the Government. But Lieutenant Baldry opposed this, too, on the grounds that: “To submit that [he] could do work of national importance at this crisis when [he] had had every opportunity [to do so] since the war began was absurd. The only way [he] could do work of national importance was to go into the army and be drilled.” Consequently, the application to alter the certificates was refused. The point here was that while, as a non-combatant, Murray would still be under military orders, with an absolute exemption or doing work of national importance he would not.

On 10 April 1916, Murray had received another summons on Army Form W 3236, signed by Major A.K. Slessor, the Recruiting Officer[54], requiring him to join for service with the Colours on 26 April at the Recruiting Office, 90 High Street, Oxford. But on 22 April, four days before he was due to report, Murray received a hand-written note from Major Slessor which read:

If you fail to present yourself on the day and hour specified on your notice paper[,] I have no option but to issue a warrant for yr arrest at once. I suggest that you present yourself here, under protest if you like, not go to Cowley Barracks with any other men due that day and then start on yr self imposed martyrdom if still so disposed instead of going through the degrading preliminaries I get so sick of seeing and giving a world of trouble to a great many over-worked officials.

Murray did not comply and was arrested immediately after the rejection of his application to the Local Tribunal on 1 May. Consequently, he was brought before the Bench on Tuesday, 2 May:

Detective Chas. Wassell [1882–1960] said several days previously he had received an army warrant with respect to the defendant. At six o’clock the previous evening he saw the defendant as he left the sitting of the Tribunal. He asked him if he had received the notice to join up, and he replied “yes”. He inquired why he had not done so and the defendant said he was waiting the result of that night’s proceedings at the Tribunal. He took him to the police station and charged him, but he made no reply.

Major Slessor said the defendant was called up under the Military Service Act on April 26th. He failed to appear and [the] witness sent out a warrant the next day for his arrest.

[The] defendant had previously appealed as a conscientious objector. The appeal was refused as was also leave to appeal to the Central Tribunal.

[The] defendant who had nothing to say was fined 40s. to be deducted from his army pay, and handed over to a military escort.[55]

Murray and one other man were taken to Cowley Barracks and put in the guardroom. But Murray’s network was still active and he received a letter from “Bill”, presumably written on 3 May 1916, who was a member of the Student Christian Movement of Great Britain and Ireland,[56] and who wrote: “A note from Dick Graham came to Fan [?] by second post, and has just been brought here by Sarah [?]. I am very sorry to hear that you’ve been arrested.”[57]

Murray’s imprisonment did not, however, last long, for on 3 May 1916 he underwent a medical examination at Cowley Barracks, was declared unfit for military service and discharged. It is worth noting that “Both [defendants] testify, to the kindness and courtesy with which they were treated alike by the police and Military Authorities.”[58] But this was not always the case. (Compare it, for example, with Graham’s Conscription and Conscience, Chapter 4, and Gilbert Murray in Hobhouse’s I appeal unto Caesar, pp. viii–xi.)

Murray’s discharge on medical grounds after one day with the Colours. The date of this certificate is either wrong (should be 1916) or was issued a year later to give Murray protection from a further call up.

Murray’s release activated his network once more and he received letters from Whitley (“I am so glad!”) and from the Bishop of Oxford (“… relieved beyond measure that you are let free”).[59] But the extent of his connections is brought home in a letter from Professor Peake dated 6 May 1916: “Many thanks for your letter. I was corresponding with Graham[60] and Gilbert Murray about you. […] It was a great relief to get your letter and know that you were the other side of the tunnel.”[61] But more surprising still, on 5 May 1916 Lieutenant Baldry, Murray’s military adversary, wrote to Murray declining an invitation on the grounds that it was his only weekend off in the month when he would be able to see his family, but ended: “I hope to meet you again under happier auspices and less trying conditions.”[62]

Murray’s case aroused some criticism of the procedures – notably why Murray could not have had his medical at an early stage, thus making all the Tribunal’s hearings unnecessary. In a long letter to the Oxford Chronicle Baldry defended the military position by pointing out that they could not order a medical until the man had come under military jurisdiction. But he conceded that it was possible for a man to be given a medical at Cowley Barracks in advance of his hearing and to be given the appropriate certificate if he was found to be unfit. Murray had, however, chosen not to avail himself of this opportunity. Baldry then added: “The result would have been the same two months ago as it was last week, with the exception – that we should have been spared the sight of a man like Mr. Murray standing in the dock at the City Police Court charged with an offence against the law of the land. I believe Mr. Murray will now admit the ‘futility’ of this applies to his own actions.”[63] It seems that Baldry had missed the point of Murray’s actions.

Instead of being ordained after the war, Albert Victor Murray became a lecturer in education at Selly Oak Colleges, Birmingham, and eventually President of Cheshunt College in Cambridge. He was elected Vice-President of the Methodist Conference in 1947, and after he retired to Grassington he continued preaching and lecturing, particularly to working-class audiences.[64] He died on 10 June 1967.

An interesting letter by Murray focuses on another, largely forgotten aspect of the war, the treatment of German nationals. On 3 November 1914 Murray wrote to “The Commandant, Concentration Camp, Newbury” [65], i.e. the internment camp that had been set up at the end of August 1914 on Newbury Racecourse with Colonel Gregory Sinclair Haines (1858–1919) as its Commanding Officer.

The camp was eventually staffed by the Berkshire National Reserve and was largely a transit camp, from which most of its civilian prisoners would be transferred to camps on the Isle of Wight. Although a pejorative term by 1914, the expression “Concentration Camp” did not connote what it does today. Nevertheless, it derived from the official name for the internment camps for civilians which the British had set up in South Africa during the Second Boer War and which even then gained a certain notoriety because of their high mortality rates due to disease. The letter in question sought special permission and an appropriate pass that would enable Murray to visit the Reverend J(acob) W(ilhelm) Hauer (1881–1962), an internee who was applying for a special scholarship at Magdalen. The pass was granted and Murray’s task was then allegedly to discover what work he was doing for that scholarship. His referees for the pass were Dr Selbie and Mr Clement Charles Julian Webb (1865–1954), Magdalen’s Philosophy Fellow (1889–1922).

Hauer was educated at the Mission College in Basel, Switzerland, and had been a missionary in British India from 1907 to 1911. He matriculated at Oxford as a non-collegiate member of the University in 1911, was admitted to Jesus College in January 1913, and was awarded a 1st in Literae Humaniores in Trinity Term 1914. On 5 August 1914, C.C.J. Webb wrote in his compendious and detailed Diary: “We declared war on Germany before midnight yesterday […] Greats list out: Edward Bridges [1892–1969][66] and Hauer 1st; wrote to both. It was odd writing to Hauer, who is a German subject.”[67]

Despite what Murray says, Hauer does not seem to have applied for a special scholarship at Magdalen but continued as a member of Jesus College, whose Battels records show him to be in residence:

Fri. and Sat. 7–8 August 1914

Fri. 9 August to Mon. 26 October 1914 [i.e. Long Vacation 1914]

Fri. 20 November to Thurs. 17 December 1914 [i.e. the second half of Michaelmas Term 1914]

Mon. 25 January to Sat. 13 March 1915 [i.e. Hilary Term 1915]

Fri. 23 April to Mon. 17 May 1915 [i.e. part of Trinity Term 1915].[68]

In his diary entry of 22 October 1914 Webb notes that Hauer had “been arrested as an enemy alien and is to be removed to a detention camp”. Webb was obviously concerned because on the following day he wrote “Went to the Chief Constable about Hauer. He was in the police yard, where I saw him & talked to him. Nothing can be done till he has been taken to detention camp; then he may appeal to the military authorities.” The reason for his concern becomes clear in the entry for 28 October “Hauer up as candidate for admission as a B. Litt. student. Decided that being an enemy alien should not be a bar. […] He went off to Newbury (Murray’s ‘Concentration Camp’) on Monday.” On 23 November Webb writes “Hauer released and now back in Oxford”, presumably after an appeal to the military authorities, and back in Jesus College according to the Battels records. On 2 December Hauer was accepted as a B.Litt. candidate by the Litterae Humaniores Board. He may have started his B.Litt. work at Jesus College as their Battels records show him to be in residence until 17 May 1915, and the last entry is followed by the note: “Down. Interned as a German.” At the time of Murray’s letter of 3 November 1914, however, Hauer was an internee. He was finally released from internment after promising “that he would not take up arms”, and sent back to Germany in 1915,[69] probably when he left Jesus College. Hauer never started at Magdalen.

Murray possibly knew Hauer through the Student Christian Union, although it is doubtful that he would have subscribed to Hauer’s religious views, had he known them. While this is not the place to discuss such a complex and devious a person as Hauer in detail, some highlights are not without interest.

According to Karla Poewe and Irving Hexham, Hauer received his first doctorate (Dr promov.) in Tübingen in 1918 and his second doctorate (Dr habil.) in 1920, having studied under the supervision of Professor Richard Garbe (1857–1927), Professor of the History of Religions, whose chair he would later fill.[70]

Jacob Wilhelm Hauer (1881–1962) (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-2004-0413-500/CC-BY-SA); “Hauer liked comparison with Nietzsche”[71]

Hauer speaking at a meeting in Germany c. 1935

In their detailed paper on Hauer, Poewe and Hexham note that: “Having learned of Hauer’s Nazi activities, Hartenstein [the Director of the Basler Mission] wrote to Hauer on 29 November 1933 that ‘because your name is still mentioned in connection with the Basler Mission’ in public discussions and newspapers, […] he [Hartenstein] was forced to declare publicly ‘that the connection between your name and the evangelical Missionswerk is dissolved’.” However, Hauer must have undergone a sudden change of views in 1933 for as late as April of that year he was the only member of the Tübingen University faculty who opposed, effectively vetoing, the granting of an Honorary degree to Hitler, on the grounds that he had no academic accomplishments to his name.[72] Then Poewe and Hexham tell us that in 1934, “Himmler and Heydrich persuaded Hauer to join the SS (Schutz-Staffel) (SS number 77779) and SD (Sicherheitsdienst)” and that in 1937, he joined the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter-Partei)”.[73]

According to Rosemary Dunhill, one-time Archivist of Jesus College, Oxford, Hauer lost sympathy with extreme Nazi racist ideology from 1936 and even staged a protest after 9 November 1938, the date of Kristallnacht in Tübingen when the Nazis sacked and burned the synagogue there. Nevertheless, from 1945 to 1947 he was interned. From the papers of his denazification tribunal[74] Hauer was from 1938 to 1941 an Untersturmführer in the SS and from 1941 to 1943 a Hauptsturmführer, equivalent to a captain. In agreement with Dunhill, Poewe and Hexham have little to say about Hauer’s links with the Nazi Party itself and its affiliated organizations after mid-1937, when the party failed to embrace Hauer’s new religion – the Deutsche Glaubensbewegung, incorporating German paganism and much influenced by the Bhagavad Gita. However, as shown below, Hauer was having personal conversations with Himmler in late 1938/early1939. In the same vein, Karla Poewe writes:

With the exception of fellow SS officers, none of Hauer’s correspondents was told that he was a member of the SS and the SD and that he could, and would, spy on them. The most famous example was Martin Buber [1878–1965] who probably did not know that Hauer had spied on him and who later wrote a generous letter of reference for his so-called Persilschein[75] that helped Hauer get off lightly in the denazification hearing.[76]

In January 1939 Hauer applied for permission to marry Annie Brügemann, subject to producing suitable family trees showing them both to be pure Aryans and to a satisfactory medical examination to eliminate the possibility of either of them carrying an inherited defect. In his formal application dated 28 February 1939[77] he explains that he brought up the issue of marriage in a personal conversation with Heinrich Himmler (1900–1945), Reichsführer of the SS, who gave Hauer provisional permission to marry. This claim is supported by a letter from Himmler dated 19 January 1939,[78] which suggests that Hauer may have been, as late as at least the first part of 1939, more influential than his rank entailed. It is worth noting that of all the major figures in the Nazi Party Himmler was the one most sympathetic to Hauer’s religious outlook. The same application form notes a satisfactory medical examination of Hauer and Annie Brügemann, by Dr Albert Schramm of the SS, and it appears that Hauer was attached to a SD unit under the command of Dr Franz Six (1909–75), who would have directed police operations in the UK had a German invasion in 1940 been successful. So Murray and Magdalen were perhaps fortunate that Hauer did not apply for a scholarship and was returned to Germany in 1915.

There is a certain irony in one of the photographs among Murray’s papers, taken in St John’s Quad, Magdalen. It shows two unidentified men in officer’s uniform and Murray, with a pipe, plus a second man in civilian clothes. The name “Conrad E. Snow” is written on the back of the photograph, and he was presumably either the second man in civilian clothes or the photographer. Conrad Snow was an American Rhodes Scholar and came up to Magdalen in Michaelmas Term 1913, where he read Law. He later practised Law in Rochester, New Hampshire, and in 1950 served on a clemency board that was sent to Germany to consider recommendations for parole for some German war criminals.[79] So it is just possible that he dealt with some of Hauer’s erstwhile colleagues.

Murray (with pipe) and friends Magdalen (c. 1915); the man out of uniform on the right is possibly Conrad Snow

Murray and two of the same three friends outside Magdalen (c. 1915).

—

[1] Grateful thanks to John S. Murray, Victor’s son, who has corrected a number of errors and provided more information, and who gave this photograph and other Murray papers to the Liddle Collection, University of Leeds. The editors also wish to thank him for allowing us to quote at length from his father’s memoir and his correspondence.

[2] Thanks to Richard Davies of the Special Collections, Brotherton Library, Leeds University, who provided me with so much material on Murray and his friends from the Liddle Collection. LIDDLE/WW1/CO/066.

[3] Or Scotland Gate as he would probably have liked to call it. A.V. Murray, A Northumbrian Methodist Childhood, edited by Geoffrey E. Milburn (Morpeth: Northumberland County Library, 1992), pp. 2–3.

[4] Murray’s title is also the title of a poem by the religious poet Francis Thompson (1859–1907).

[5] Murray’s memoir is quoted in full in Campbell’s biography in Slow Dusk.

[6] Albert Victor Murray, ‘In No Strange Land’ (typescript, Liddle Collection, Leeds University; LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5) p. 1.

[7] Ibid. p.2.

[8] It is not easy to read all the signatures.

[9] Menu provided by Caroline Marsh from the papers of George Gordon Miln (1890–1918); killed in action on 22 April 1918, while serving as a Captain with 15th Battalion, Cheshire regiment); see his entry in Slow Dusk.

[10] William Stubbs, Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History: From the Earliest Times to the Reign of Edward the First. (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1874).

[11] Albert Victor Murray, ‘In No Strange Land’, p. 2.

[12] Probably Karl Baedeker, Italy from the Alps to Naples; Handbook for Travellers, (Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, Publisher, 1904).

[13] Albert Victor Murray, ‘In No Strange Land’, p. 3.

[14] Dated 23 March 1915, The Low Country (sic); LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[15] Murray (1992), p. 59.

[16] Ibid., p. 92.

[17] John Brett Langstaff (1889–1985) graduated at Harvard University, coming up to Oxford to read for a B.Litt. at Magdalen in 1914 just after the beginning of the war. Most of the students who had matriculated in 1912 and 1913 had enlisted, and few are mentioned in his book Oxford – 1914. One of those on the Magdalen Memorial he knew well was Phillip Howson Pye-Smith. But he also discusses some of those who, for whatever reason, had not enlisted and were in residence, for example Graham and Murray. He went back to the United States, where he was ordained, but returned to enlist in the Artists’ Rifles in October 1918, being discharged two months later as “not fit for service”. In 1919 he became head of the Magdalen Mission in London, but he eventually returned to the USA, where he was the incumbent of various Episcopalian churches in New York.

[18] Stodard Ogden Hoffman (1892–1941), brother of Charles Gouverneur Hoffmann (1888–1974) (Magdalen Commoner 1913–16), an American contemporary of Langstaff at Magdalen.

[19] Charles Rischbieth Jury (1893–1958) (Magdalen Commoner 1913–18), poet and academic from Glenelg, South Australia. Jury enlisted in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry on 8 October 1914, he was badly wounded at Ypres in 1915, and invalided out of the army, returning to Magdalen in March 1916 to continue his studies. He was awarded a 1st in English Language and Literature in June 1918 and took his BA in July.

[20] See paragraph on Hough, Edwin Purdon Kighley (1895–1937), in the section ‘Magdalen men who for no reason we know of did not serve in the armed forces’.

[21] John Brett Langstaff, Oxford – 1914 (New York, Washington and Hollywood: Vantage Press, 1965), p. 275.

[22] Pacifist and patron of the arts.

[23] Writer and from 1930 Poet Laureate.

[24] Letter from Kenneth Murray to Victor Murray dated 27.xii.14, from Lightwood, Kenley, Surrey; LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[25] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[26] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[27] London Gazette Supplement 29,170 (21 May 1915) p. 4,990.

[28] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[29] Letter from Basil Charlesworth to Albert Murray, 7 October 1918; LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[30] Maude Royden (1876–1956) was educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. She worked in a settlement in Liverpool; gave up her position on the Committee of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies because of its support for the war; and became the Secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation with other Christian pacifists. She corresponded with Murray: LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 2.

[31] James Saumarez Mann, An Administrator in the Making: James Saumarez Mann, 1893–1920, Edited by his Father (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1921), p. 303.

[32] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 5.

[33] As well as his Slow Dusk biography, see also his entry in this section under ‘Magdalen Alumni who served in non-combatant units’.

[34] See the essay ‘Pacifists and Conscientious Objectors: They Did Not Fight’, note 21.

[35] Arthur Samuel Peake (1865–1929), from 1904 the Rylands Professor of Biblical Exegesis in the University of Manchester.

[36] Burnett Hillman Streeter (1874–1937), Fellow and later Provost of The Queen’s College, Oxford, Senior Treasurer of the Oxford Student Christian Union.

[37] Rev. Tissington Tatlow (1876–1957), General Secretary of the Student Christian Movement.

[38] William Selbie (1862–1944), Principal of Mansfield College 1909–32.

[39] [Anon.], ‘Military Service; Oxford Local Tribunal; Secretary of the Student Christian Movement’, The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,202 (10 March 1916), p. 8.

[40] Burnett Hillman Streeter, War, This War and the Sermon on the Mount (London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1915) p. 5.

[41] Peake, like Murray, was a Primitive Methodist, and had encouraged and helped him.

[42] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[43] John Henry Whitley (1866–-1935), Liberal MP for Halifax (1900–28). On his retirement he declined the customary peerage and a knighthood. See H.J. Wilson, ‘Whitley, John Henry (1866–1935)’, rev. Mark Pottle, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: OUP, 2004). Also on-line at: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-36875?rskey=59jilM&result=2 (accessed 6 April 2022).

[44] The Pelham Committee, which was set up in 1916. As things turned out, Harvey was made a member but not the Bishop of Oxford. See John Rae, Conscience and Politics: The British Government and the Conscientious Objector to Military Service 1916–1919 (London: OUP, 1970), p. 125.

[45] Thomas Edmund Harvey (1875–1955) Liberal (later Independent Progressive) MP for West Leeds 1910–18. Harvey was a Quaker, museum curator and social reformer.

[46] John A. Hargreaves, ‘Whitley, Percival Nathan (1893–1956)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004. Also on-line at: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-67944?rskey=btedRx&result=1 (accessed 6 April 2022).

[47] Alan Wilkinson, ‘Gore, Charles (1853–1932)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004. Also on-line at: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-33471?rskey=TR4QBF&result=2 (accessed 6 April 2022].

[48] Bishop of Oxford to AVM, 26 February 1916; LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[49] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[50] Statement of Albert Victor Murray to the Oxfordshire Appeal Tribunal, under the Military Service Act 1916; LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[51] [Anon.], ‘Appeal Tribunal, The Second Sitting at Oxford’, The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,207 (Friday 14 April 1916) p. 5.

[52] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[53] Wheeler was second in command of the 7th Battalion, the Ox. and Bucks Light Infantry, in Salonika when he was awarded the DSO (gazetted 26 July 1917) for taking command of the battalion and organizing an attack while wounded. In 1918 he was given command of the 11th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment. After the war he became headmaster of Laurence Sheriff School in Rugby.

[54] Probably Arthur Kerr Slessor (1863–1931), Major in the Sherwood Foresters and Steward of Christ Church.

[55] [Anon.], ‘Undergraduate Conscientious Objectors; Prosecution by Military Authorities; Defendants Before Magistrates’, The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,210 (5 May 1916), p. 5.

[56] Probably William Paton (1886–1943), an undergraduate at Pembroke College, Oxford), who was an Assistant Secretary. Later in 1916 Paton was dispatched to India as a YMCA secretary to prevent him from being imprisoned as a pacifist.

[57] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[58] [Anon.], ‘Undergraduate Conscientious Objectors; Prosecution by Military Authorities; Defendants Before Magistrates’, The Oxford Chronicle, 4,210 (5 May 1916), p. 5.

[59] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[60] Either Richard Brockbank Graham or more likely his father.

[61] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[62] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 1.

[63] Lieutenant Walter Burton Baldry, ‘Conscription and Medical Examination’, letter to the The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,211 (12 May 1916), p. 7.

[64] [Anon.], ‘Prof A.V. Murray’ [obituary], The Times, no. 56,966 (13 June 1967), p. 12.

[65] LIDDLE/WW1/CO 066, File 2.

[66] Edward Ettingdene Bridges, first Baron Bridges (1892–1969), Secretary to the Cabinet; son of the poet laureate Robert Seymour Bridges (1844–1930).

[67] Quotations are from the Webb diaries (August 1914–end 1916), Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Eng.misc.d.1112.

[68] Battels records from the archives of Jesus College, Oxford.

[69] Karla Poewe and Irving Hexham, ‘Jakob Wilhelm Hauer’s New Religion and National Socialism’, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 20, issue 2 (2005), pp. 195–215, p. 205.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Karla O. Poewe, New Religions and the Nazis (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), p. 12.

[72] Gregory D. Alles, ‘The Science of Religions in a Fascist State: Rudolf Otto and Jakob Wilhelm Hauer during the Third Reich’, Religion 32, pp. 177–204, p. 178.

[73] Poewe and Hexham (2005), p. 207.

[74] Bundesarchiv Berlin (Bundesarchiv, Referat R3, Finckensteinallee 63, 12205 Berlin: www.bundesarchiv.de).

[75] Persilschein is an ironic derivation from the washing powder, Persil, and in this context refers to statements from former enemies or victims exonerating suspected Nazi offenders brought before an Allied denazification Tribunal.

[76] Poewe (2006).

[77] Bundesarchiv Berlin, Bestandssignatur R8361-III; Archivnummer 68338.

[78] Ibid.

[79] [Anon.], ‘Conrad Snow, 86, Dies; Headed State Department Loyalty Board: Clashed With McCarthy Over Inquiry Into Communists – General in Reserve’ [obituary], New York Times, 23 December 1975, p. 28.