Richard Brockbank Graham (1893-1957)

The two most significant organizations of conscientious objectors during the Great War were the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) and the Friends’ Service Committee (FSC). According to Kennedy their collaboration during the war was not always harmonious.[1] However, Horace Alexander (1889–1989) (see below), a member of the FSC, and Fenner Brockway[2] (1888–1988), a founder of the NCF, both consider this a misrepresentation of what happened and their rebuttal led Kennedy to modify his views.[3] The NCF started as a left-wing organization in November 1914 with the aim of convincing the Government that compulsory military service would be impossible or at least disadvantageous.[4] With time it developed into the major pacifist organization in the country and broadened its aims to accommodate those who were prepared to take a stronger or weaker stance against military service. In contrast, the FSC was based on the pacifist beliefs of Quakers, and was created in 1915 at the yearly meeting of Quakers. Although it was a smaller and much better organized group than the NCF, it, too, expressed a variety of opinions leading to a variety of responses to conscription.

Both organizations anticipated the possibility of conscription in the United Kingdom for the first time, but they were to be treated differently:

The Government […] wished to avoid any implication of religious persecution and were ‘perfectly willing to give Friends anything’, but they would never accept the ‘political objector’. In other words by showing special consideration for Quakers, the Government contemplated driving a wedge between religious COs and the more numerous and largely socialist objectors of the No-Conscription Fellowship. Ultimately, this strategy failed because leaders of the FSC, some of whom were also socialists, were determined to make common cause with the NCF.[5]

So the Quakers agreed that in the event of conscription, no exemption be accepted by members of the Society which was not available to others, and indeed “condemned this granting of ‘preferential treatment’ to Friends as a violation of ‘the spirit and concern of the Adjourned Yearly meeting … to unite ourselves to the fullest extent with all conscientious objectors’.”[6]

Here we are more interested in the FSC, as one of Magdalen’s undergraduates, Richard Brockbank Graham, was an original member of the committee, the 21 founding members of which are listed in the ‘Notes on the early members of the Friends Service Committee’ at the end of this essay. A third of these received prison sentences rather than obtain exemption from military service and alternative positions. Five were too old to be conscripted in 1916, although Harrison Barrow was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for publishing the pamphlet A Challenge to Militarism without previously having submitted it to the Press Bureau.[7] Four obtained exemption: Richard Graham and Horace Alexander by agreeing to join the General Service Section of the Friends Ambulance Unit as teachers, Robert Long as already involved in a peace organization, and Henry Harris as the Diplomatic Correspondent of the Daily News. John Heath worked for the Ministry of Pensions and the Ministry of Labour and was involved in the founding of the Whitley Council, which sought to seek agreement between workers and employers on a variety of issues. Robert Davis was exempted conditional upon continuing his Quaker extension work. Charles Elcock was exempted conditional upon continuing work for the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Yorkshire, and then Friends’ War Victims Relief Service in their London office. Although the FSC would “become the most intransigent of all peace organizations, urging conscientious objectors to reject offers of alternative service”,[8] not all Quakers were as intransigent as some members of the FSC, since a third (1,000) of all Quakers of military age served, and over a hundred of them were killed.[9]

The case of Richard Graham is particularly interesting. He was the eldest son of John William Graham (1859–1932), son of the Quaker Michael Graham (1826–1906), a Preston tea dealer, and Margaret Brockbank (1863–1945), daughter of the Quaker Richard Bowman Brockbank (1825–1912), a miller, corn merchant, and amateur geologist who lived in Burgh, Cumberland. Richard had one brother (Godfrey) Michael Graham (1890–1972) and three sisters, Olive (later Alexander) (1892–1942), Rachel (later Sturge) (1900–1976), and Agnes Bowman (later Yendel) (1905–77). John William Graham was a prominent Quaker. He read Mathematics at King’s College, Cambridge, becoming first a schoolteacher and then Tutor in Mathematics at Dalton Hall in Manchester before becoming its Principal (1897–1924). But he is best known as a Quaker thinker and as a leader of the Quaker renaissance.[10] He was, as we shall see, very much involved in the peace movement.

Richard’s brother Michael read Natural Sciences (Biology) at his father’s old college, King’s Cambridge, and as he went up his father’s parting words to him were: “Thou art going to King’s, where thou’lt meet the nicest people thou’lt meet in the whole of thy life.”[11] On graduation he became a marine biologist and from 1948 to 1958 he was the Director of Fishery Research at the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. But Michael did not share his father’s or Richard’s pacifist views and described his activities during the First World War as follows:

On January 1, 1917, I joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, and after a period of training as wireless operator, went to sea in ships of the Auxiliary Patrol as a telegraphist. In the summer of 1918, I obtained a commission in the same service, and was at sea until the end of the war in the Motor Launches of the Dover Patrol.[12]

According to his obituary:

In the Second World War he took a leading part in organizing the Lowestoft fishing fleet’s contribution to the evacuation of Dunkirk, besides going on a highly secret mission elsewhere, and later on the continent, as an Honorary Wing-Commander, he helped to develop operational research on stricken tanks. He was mentioned in despatches and awarded the O.B.E.[13]

Nevertheless, the obituary goes on to say, “neither this degree of bellicosity nor his readiness to drink wine caused a rift, and at the end of his life he was a valued member at Quaker meetings”.[14]

Olive, Richard’s eldest sister, married the pacifist Horace Alexander who was, like Richard, exempted from military service as a schoolteacher although he was on the FSC. He spent much of his life as a lecturer but is best known for his friendship with Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) from 1928 until Gandhi’s assassination. After Gandhi’s Salt March of 1930, he acted as an intermediary between the Viceroy, Lord Irwin (1881–1959; later 1st Earl of Halifax), and the imprisoned Gandhi, who would later describe Alexander as “British in nationality, but Indian at heart”.[15] Rachel, Richard’s second sister, was the second wife of Paul Dudley Sturge (1891–1974), a Quaker non-combatant who served in France as a British Red Cross Society Chauffeur and received the 1915 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. From 1935 to 1956 he was Secretary of the British Friends’ Service Council when, together with its American counterpart, they were awarded jointly the Nobel Peace Prize in 1947. He was also involved in helping to rebuild Germany after each of the two world wars.[16] Agnes, Richard’s youngest sister, married the poet and sculptor Norman Charles Yendell (1906–84).

Richard Graham first attended Bootham School, York (1906–10), a Quaker foundation, and then Manchester Grammar School (1910–12), where he was in the football first eleven and the cricket second eleven. In December 1911 he was awarded an Exhibition in History at Magdalen, where he obtained a second class in Literae Humaniores (1916). In 1925 Richard married Gertrude Anson (1895–1987), the daughter of George Edward Anson (1848–1927), a wholesale clothing manufacturer, with whom he had a son and two daughters. Like Richard’s brother Michael, his brother-in-law, Wilfred (later Sir Wilfred) Anson (1893–1974),[17] was a war hero, who was awarded the Military Cross on 1 January 1917 for his gallantry while serving with the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. He later became Director of the Imperial Tobacco Company and Pro Vice-Chancellor of Bristol University.

Conscription began in January 1916, and when called up, Richard Graham applied for exemption on grounds of conscience. He appeared before the Oxford Local Tribunal, and his appearance was reported in the Oxford Times of 4 March 1916:[18]

Richard Brockbank Graham, aged 22, Magdalen College, taking his final examination in Literae Humaniores in June next, applied for absolute exemption. He believed that warfare was fundamentally wrong and un-Christian both in itself and as a means even to a good end. For this reason he should think it wrong to contribute anything, as a soldier or a non-combatant, to the success of the present war beyond what was necessarily involved in the doing of any useful work. With regard to applying for absolute exemption, he was certainly anxious to render the community the truest service of which he was capable, but in deciding what this service is he could only be guided by what seemed to him to be right. He had no desire to do work to which the tribunal could justly object, but as he should only do work approved by the Tribunal, if he was convinced independently that it was right of him to do it, he felt bound to claim absolute exemption.

The Town Clerk: “that is rather wordy, Mr Graham? What does it all mean?” Mr Graham said that he was quite ready to elucidate anything the Tribunal wished him to.

In reply to a question as to how long he had been a conscientious objector, applicant replied that it was almost four years.

Applicant’s father, who appeared with him, read part of a letter from the President of Magdalen (Sir Herbert Warren) who wrote that applicant’s statements were certainly to be considered as coming from a conscientious person. He would be the last person to plead for anybody of military age and fitness, but he believed Mr. Graham held his views with conviction. The father stated that the letter continued with laudatory remarks upon the applicant’s character, which perhaps it was well not to read in public.

Applicant’s father stated that both he and his son were members of the Society of Friends, and that since his son was very young he had evinced sympathy with that Society’s tenets. He and his son were in the habit of devoting much time to peace work in public and in various ways. Plenty of evidence could be brought forward.

Lieut. Baldry: “You are a member of the Society of Friends?”

Applicant: “Yes”.

Lieut, Baldry: “Do you agree with their teachings?”

Applicant: “I do not answer that question directly. Each member is free to follow his own conviction on particular points”.

Lieut. Baldry: “It is no catch. You agree with them and their actions?”

Applicant: “Oh yes”.

Lieut. Baldry: “The Society of Friends has an ambulance at the Front which Mr. Graham can go to”. (laughter)

Upon a remark by the applicant’s father, the Town Clerk said that the Tribunal could only let anyone off combatant service.

Applicant (rising): “It is provided by the Act that absolute exemption may be given – (loud applause). I can read you a passage from the Orders of Council”.

Mr. Graham then proceeded to show under Schedule 2, Section 5 of the Act, that the King might by Order in Council decide the constitution of the tribunals and direct their action. Under these directions he then quoted the circular relating to the constitution, functions and procedures of the local tribunals. “There may be exceptional cases in which a genuine conviction and the circumstances of the man are such that neither exemption from combatant service nor a conditional exemption will adequately meet the case. Absolute exemption can be granted in this case if the tribunal are fully satisfied of the facts”. (applause)

Lieut. Baldry: “Mr. Graham says he is a member of the Society of Friends. He approves their doctrines and actions and they have got an ambulance at the Front”.

Applicant explained that in the Society of Friends they did not have matters of dogma at all, and every Friend was not expected to do what a particular section might decide to do itself. As in other things, each man was left to say himself what particular work he would or would not do. (loud applause)

The Mayor: “Order Order, or I shall clear the room”.

Applicant’s father: ‘The Tribunal has to give the minimum exemption which satisfies the conscientious objections of the applicant”.

Applicant was exempted from combatant service and temporarily exempted from any services until July 1 in order that he might take his examination.

Applicant: “I shall certainly appeal”, (applause).

A further article added:

Lieutenant Baldry gave notice of an appeal against Graham’s exemption from Combatant service.[19]

It is clear that Richard Graham had done his homework and seemed more aware of the workings of the Act than members of the Tribunal. So it is easy to see why he might have been considered “a leader amongst the conscientious objectors of town and university”, a point that is emphasized by his interest in Albert Victor Murray’s appeal. Graham’s appeal was heard at the first meeting of the Oxfordshire Appeal Tribunal, which was held in the Sessions Room of County Hall on Tuesday 21 March 1916.[20] The Tribunal’s constitution was announced in the London Gazette on 29 February 1916: Francis Fitzgerald (1865–1939), the Recorder of Newbury (Chairman); the Hon. Harold Albert Denison (1857–1948), one time Lieutenant in the Royal Navy; Sir Walter Gray (1848–1918), First Steward of Keble College, Oxford, or 13 years and four times Mayor of Oxford; Edmund Augustine Bevers (1849–1921), Dental Surgeon at the Radcliffe Infirmary and twice Mayor of Oxford; Henry James Cooke (1858–1931), Secretary and Manager of the Co-operative Society; Alfred Denis Godley (1856–1925), Fellow of Magdalen (1883–1912), Public Orator of Oxford University (1910–20), author of the well-known poem in macaronic Latin ‘The Motorbus’, and Officer Commanding the Oxford Volunteer Rifle Force: “He was an ardent supporter of voluntary military training, and the patriotism which was one of his deepest feelings found practical expression in his training and organization of a volunteer force during the First World War”.[21]; Hugh Hall (1848–1940), barrister and journalist; Ernest Samuelson (1856–1927), manufacturer of flour milling and agricultural machinery, later High Sheriff of Oxfordshire; William Smith (1848–1916), blanket manufacturer (died before the first sitting of the Tribunal); Frederick William Young (1874–1937), farmer. The Oxford Chronicle complained that the composition of the Appeal Tribunal was partisan on the grounds that the four City representatives were all Tories, whereas, in what was supposed to be a non-partisan body, half of the six County representatives were Liberals. There is no evidence that Godley, who had been a lacklustre Tutor in Classics at Magdalen until his retirement[22] and who may have been involved in awarding Graham an Exhibition, excused himself from the proceedings on the grounds of bias. Indeed, as noted above, he was unlikely to have been sympathetic to Graham. James Lungley (1863–1936), a solicitor, was Clerk to the Tribunal and Captain W.H. Bailey was the military representative; the defending solicitor, Frank Gray (1880–1935), was a solicitor in Oxford from 1903 to 1916, when he joined the Royal Berkshire Regiment as a private soldier. From 1922 to 1924 he was the Liberal MP for Oxford.

The Oxford Times reported that: “There was a large attendance of the public, chiefly however, sympathisers of the conscientious objectors, and Mr Sydney [sic] Ball[23], of St John’s College, was amongst those present.”[24] Graham was the seventh conscientious objector to appear before the Oxford Appeals Tribunal and his expectations cannot have been high since all the previous cases had either been dismissed or ended with the appellant being given exemption from combatant service alone. The report reads:

Richard B. Graham (22), Magdalen College, a member of the Society of Friends, who had claimed exemption on conscientious grounds, had been [temporarily] exempted from combatant service. Mr Frank Gray also appeared in this case.

A letter from the President of Magdalen and another from Appellant’s father were read. The former testified that he had reason to believe that when Appellant advanced conscientious objection, this might be considered as coming from a conscientious person. His father was a member of the Society of Friends, and his son had been brought up under the tenets of that body. The letter from Mr. Graham senr. was to the effect that his son held beliefs which would prevent him undertaking military service in any form.

-Appellant urged that his objection to non-combatant service was part of his whole objection. His objection was not primarily to killing. It was not only physical repulsion to killing, but went further because he regarded war as contrary to the Christian law of love and kindness, and he regarded it as impossible for a nation to go to war and conduct war in the complete spirit of love and kindness towards the enemy and in general. For that reason he refused to be organised for war, whether it involve the actual taking of life by himself or not. He would not go into the R.A.M.C. (although he would help a wounded soldier) partly because to do so was to be organised for war, but chiefly because when one entered that body, one had to take the military oath, and become part of the machine of war.

He should approve of ambulance work which was not under military authority. Appellant added that 23 members of his society had received absolute exemption.

-The Chairman pointed out that the Society of Friends had an ambulance at the front.

-Appellant replied that the ambulance was organised by certain individual Friends not by the Society as a whole. The Society as a whole objected to being organised for the successful prosecution of the war.

-The Chairman: There are members of the Society who have different views to yours as to non-combatant service.

-Appellant: There are certainly Friends who have different views from mine. There are some in the trenches. Appellant further said he would not object to taking part in the work of an ambulance unit that was not under military control.

-The Chairman: On what grounds do you base your objection to good work because it is under military control?

-Appellant: I don’t like to give my conscience into anybody else’s keeping.

-Appellant in answer to Capt. Bailey said he thought there was no military discipline in the Friends Ambulance Unit.

-Bailey: “There must be of some sort”.

-John Wm. Graham, appellant’s father, was allowed briefly to support his son’s statements.

-The Court dismissed the appeal. The Chairman saying Appellant would have to abide by the [temporary] exemption already given from combatant service.[25]

The FAU (Friends Ambulance Unit), set up largely on the initiative of Philip Noel-Baker (1889–1982), was a voluntary nursing corps that provided an outlet for Quakers who did not want to be seen as avoiding military service through cowardice. But after the introduction of conscription in 1916 it “became tainted by the accusation of a too-cozy relationship with the military authorities”[26] and was no longer an alternative for some of those who wished to avoid military control.

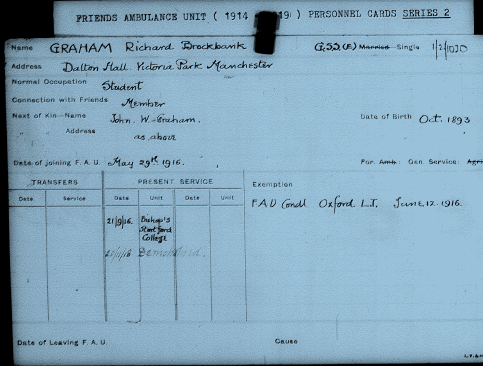

The support that Richard Graham received from his father was not perhaps as it might seem from the newspaper reports. In the 1890s “[John] Graham’s vision of ‘an energetic and self-sacrificing peace policy’ struck a responsive chord among some co-religionists.”[27] But in a lecture of 1911 he said that Quakers “should be prepared to assist in defending the Nation – most assuredly as non-combatants – in any war threatening British security.”[28] And in 1913 he wrote to Richard: “I think our duty as citizens compels us to defend the country against an invader.”[29] Although such statements were hardly likely to appeal to an Absolutist member of the FSC, Kennedy describes at some length[30] how John Graham influenced his son’s attitude to exemption, advising him to apply for absolute exemption, as the law allowed, but to further cover himself by declaring his intention to take up teaching, an occupation that might be defined as “work of national importance”.[31] This was, of course, at odds with the views of most FSC members, who, as we have seen, refused to accept alternative service. Nevertheless, it seems as if John Graham’s views prevailed, for Richard, like his brother-in-law Horace Alexander, became a schoolteacher. Although his name does not appear among those who went to prison in the War-time Service Lists that were published in Bootham, his school magazine, he is listed there under Old York Scholars who were serving with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, with “Edl.” after his name to denote the Educational Section – which may indicate that he took up a teaching position on the grounds that it was a less militaristic option than serving with the FAU at the front. His FAU Personnel Card shows that he joined on 28 May 1916 for General Service and that he was granted conditional exemption by the Oxford Local Tribunal on 12 June 1916. There was, however, opposition to conscientious objectors going into teaching and Lord Charnwood (Godfrey Rathbone Benson, 1st Baron Charnwood 1864–1945) put down the following motion in the House of Lords in November 1917: “That no person who has applied for exemption (conditional or total) from military service on the ground of conscientious objection ought thereafter to be permitted to teach in any school or college supported or assisted by public funds.”[32] But the motion was soundly defeated.

Richard Brockbank Graham, FAU Personnel Card

Graham was seen by his colleagues as a militant conscientious objector and at times perhaps an insufferable one, as suggested by Langstaff’s description: “[…] Dick Graham, who has a ‘Quaker bug’ of ‘not fighting’ but makes everybody feel like punching his head for the things he does and says.”[33] And, in letters to his friend Victor Murray (a conscientious objector), Raymond Charlesworth (1894–1918) – who himself agonized about joining the army, being torn between “Christian pacifism” and the “magnificent men who are going to fight for the safety of their homes & mothers & sisters”, did so and died of wounds near Péronne – wrote: “I have apparently taken the irrevocable step and booked my ticket for hell as RBG (Graham) would no doubt consider it” (1 April 1915); and later: “I had a long letter from RBG the other day, he seems to be going strong and sticking violently to his convictions” (24 March 1917); and “Dick Graham, that thick skinned old pedagogue still writes some pages of bilge periodically” (8 January 1918).[34] But one cannot help feeling that there is affection for Graham in these remarks.

After taking his final examinations in the summer of 1916, Graham left Magdalen, and on 21 September 1916 he became an assistant Master at Bishop’s Stortford College. This was not a surprising choice since the College’s Headmaster, Frances Samuel Young (1871–1934), was at least sympathetic to pacifist views. Not only did he accept Graham as a teacher during the war, but after Graham’s demobilization on 20 November 1918 he engaged three conscientious objectors as masters, and “refused to continue military training for the boys in peacetime despite representations from the War Office”.[35] From 1919 to 1927 Graham taught at Leighton Park, a Quaker school, before becoming Headmaster of King Edward VII School, Sheffield, in 1928, and Headmaster of Bradford Grammar School from 1938 until his retirement in 1953.[36]

Richard Graham (right) at Bishop’s Stortford College c.1919

(Courtesy of Jeremy Gladwin, Headmaster of Bishop’s Stortford College)

Graham’s interest in the peace movement and the consequences of his conscientious objection did not, however, end in 1918. In February 1927 the No More War Movement began publishing in their magazine No More War a series of brief statements by some hundred people under the heading, “Why I Believe in the No More War Movement, Leaders of Thought and Action Give Their Reasons”.[37] Among those writing were John and Richard Graham. Richard wrote:

Because there is enough goodwill in the world, if we make it known, to make complete peace a practicable policy. Because I for myself would feel it wrong to surrender my will and service even to my own country for war: our allegiance in war and peace should be to wisdom and loving the Peace-Lord.

But his father took a more practical approach:

The pressure of public opinion at the critical moment before a war, and the facilities for inflaming fear and evoking a mistaken loyalty, are so great and so dazzling, that nothing but a solemn resolution not to fight at any time, taken deliberately in advance, and made part of our habitual mind, is strong enough to stand against the whirl to war.

Richard Brockbank Graham, Headmaster of King Edward VII School, Sheffield (1928-38).

Graham was an expert and enthusiastic mountaineer and a member of the Alpine Club and the Fell and Rock Climbing Club. He was “well known to the entire climbing fraternity as a cheerful and generous companion, a natural leader with a great eye for a route, and a fine strategist and tactician who was particularly strong on snow and ice”.[38] In 1923 Brigadier Charles Granville Bruce (1866–1939), the leader of the 1924 Everest Expedition, put Graham’s name forward to the Alpine Club as a member of the expedition. But the Everest Committee withdrew the offer. “The Everest invitation gave him (Graham) tremendous pleasure; so to learn soon afterwards that some militarist members among the team nurtured conscientious objections of their own towards climbing with a ‘non-fighter’ was a bitter blow.”[39] This was by no means true of all members of the expedition; George Mallory (1886–1924) wrote a “furious letter” to Bruce, and Howard Somervell (1890–1975), another member of the expedition, threatened to leave the Alpine Club because of the treatment of Graham. But it was not a military member of the expedition who was instrumental in destroying Graham’s hopes but Bentley Beetham (1886–1963), who apart from Andrew (Sandy) Irvine (1902–24), who had been too young, was the only member of the expedition not to have served in the war. Like Graham, he had been a schoolmaster.[40]

Apart from having a distinguished career in education, Graham played an active role in the local Society of Friends, the League of Nations Union and the Youth Hostels Association, which well reflected his interests. He was a member of the Committee, chaired by Arthur Hobhouse (1886–1965) (brother of Stephen, see below), whose work led to the founding of the National Parks system with the opening of the first, the Peak Park, in 1951.

Notes on the early Members of the Friends Service Committee[41]

Horace G. Alexander (1889–1989)[42]

Brother-in-law of Richard Brockbank Graham; Friend of Gandhi and supporter of Indian independence; exempted from military service – became a teacher.

Harrison Barrow (1868–1953)[43]

Birmingham Alderman; too old for conscription but served a six-month sentence for publishing a pamphlet entitled A Challenge to Militarism (contrary to the Defence of the Realm Act).

Alfred Barratt Brown (1887–1944)[44]

Principal of Ruskin College (1925–44); imprisoned for publishing the leaflet Repeal the Act, and twice as conscientious objector.

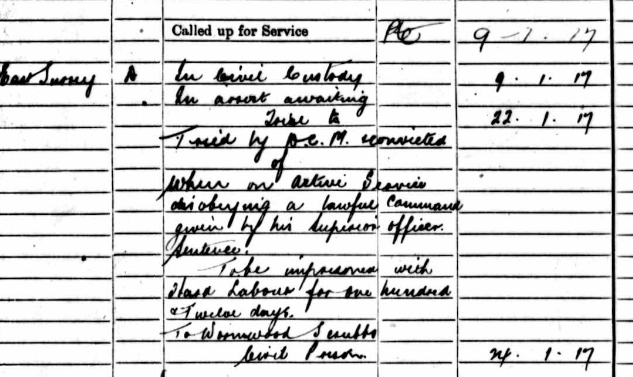

Roderic Kendall Clark 1984–1937)

Export merchant; he was granted unconditional exemption but this was lost after the military authorities appealed. He was sentenced to 112 days’ imprisonment with hard labour (see his service record below);[45] five subsequent courts martial resulted in imprisonment for two-and-a-half years in total before his release in April 1919.[46]

Excerpt from Roderic Kendall Clark’s Record of Service

James Herbert Crosland (1874–1949)

Steel business; too old for conscription in 1916; Quaker Chaplain to conscientious objectors in Liverpool prison. He emigrated to Australia in 1935.

Robert Davis (1883–1967 )

Author of Quaker Witness for Peace (1940).

Charles Ernest Elcock (1878–1944)[47]

Architect; designed The Daily Telegraph Building in Fleet Street.

Charles Irwin Evans (1870–1941)[48]

Headmaster of Leighton Park; too old to be conscripted in 1916.

Hugh Gibbins (1879–1942)

Member of the Independent Labour Party and machine manufacturer in Birmingham; “would have been allowed to continue his business by the Tribunal if he had been willing to recognize that the Tribunal had any authority over him”. Refused certificate of exemption by the Tribunal; drafted into the Non-Combatant Corps on 1 January1917; refused to sign his Record of Service or take a medical; sentenced to 112 days’ hard labour; on being released from prison he was again arrested by the military authorities.[49]

Richard B. Graham

See biography above.

Henry Wilson Harris (1883–1955)[50]

Journalist, diplomatic editor of the Daily News, editor of The Spectator; MP for Cambridge University 1945–50.

John St George Currie Heath (1882–1918)[51]

Warden of Toynbee Hall; worked for Ministry of Pensions and the Ministry of Labour; helped found the Whitley Council.

Stephen Hobhouse (1881–1961)[52]

Peace activist and prison reformer; details of his imprisonment are given in I appeal unto Caesar.[53]

Geoffrey Hoyland (1889–1965)[54]

Headmaster of Downs School; a leader of the FSC Absolutist faction.[55]

Wilfrid Ernest Littleboy (1885–1979)[56]

Chartered accountant; served a total of 28 months in prison.

Robert J. Long (1882–1953)[57]

Northern Friends Peace Board Secretary 1913–42; granted exemption from military service in 1916 as being employed full time by a recognized religious organization – and so did not spend time in prison, other than visiting and supporting those who were serving sentences for their conscientious objection.

Robert Oscar Mennell (1882–1960)[58]

Tea merchant, Secretary and later Chair of the FSC; suffered several terms of hard labour and solitary confinement.

Harold John Morland (1869–1939)[59]

Accountant and former partner in Price Waterhouse and Co.; too old to be conscripted; Quaker Chaplain in a Maidstone prison.

John Turner Walton Newbold (1888–1943)[60]

Schoolmaster, Communist MP for Motherwell and Wishaw (1923–24); in 1915 fined £25 for writing a letter “containing statements likely to interfere with the success of his Majesty’s Forces”.[61]

Hubert William Peet (1886–1951)[62]

Journalist; served three periods in prison totalling 28 months. He gives a detailed description of the prison life of a conscientious objector that was partly reproduced in These Strange Criminals.[63]

Arnold Stephenson Rowntree (1872–1951)[64]

Liberal MP for York 1914–18; Director of Rowntree’s Chocolates; a leading supporter of adult education; a member of the Executive of the FAU during the Great War; too old to be conscripted.

—

[1] Thomas C. Kennedy, ‘Fighting About Peace: The No-Conscription Fellowship and the British Friends’ Service Committee, 1915–1919’, Quaker History, 69, no. 1 (Spring 1980), pp. 3–22 (esp. pp. 12–13).

[2] (Archibald) Fenner Brockway, Baron Brockway (1888–1988). Left-wing politician and campaigner. David Howell, ‘Brockway, (Archibald) Fenner, Baron Brockway (1888–1988)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: OUP, 2004) [http://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2167/view/article/39849, accessed 13 Aug 2016].

[3] Letters from Horace Alexander, Fenner Brockway and Thomas Kennedy. Quaker History, 70, no. 1 (Spring 1981), pp. 4–57.

[4] Thomas C. Kennedy, The Hound of Conscience: A History of the No-Conscription Fellowship, 1914–1919 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1981).

[5] Thomas C. Kennedy, British Quakerism 1860–1920 (Oxford: OUP, 2001), pp. 328–29.

[6] Ibid., p. 331.

[7] [Anon.], ‘Challenge to Militarism – Society of Friends’ Disclaimer’, The Times, no. 41,833 (4 July 1918), p. 8.

[8] Martin Ceadel, Semi-Detached Idealists: The British Peace Movement and International Relations, 1854–1945 (Oxford: OUP, 2000), p. 191.

[9] Kennedy (2001), p. 313.

[10] Kennedy (2001), pp.141–44.

[11] Obituary, King’s College Cambridge, Annual Report of the Council Under Statute D. III 10 on the General and Educational Condition of the College, November 1972, pp. 38–40.

[12] Bootham Commemoration Scholarship Fund 1935, p. 27; many thanks to Jenny Orwin, Archivist and Trust Administrator, Bootham School, York.

[13] See note 53.

[14] Ibid.

[15] [Anon.], ‘Horace Alexander’ [obituary], The Times, no. 63519 (7 October 1989), p. 12.

[16] Obituary, The Friend, volume 132 (17 December 1974), p. 1476.

[17] [Anon.], ‘Sir Wilfred Anson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 59,025 (27 February 1974), p. 20.

[18] [Anon.] ‘Oxford Tribunal’, The Oxford Times, no. 2680 (4 March 1916), p. 6.

[19] [Anon.], ‘The Conscientious Objectors: War Office Order’, The Oxford Times, no. 2680 (4 March 1916), p. 7.

[20] [Anon.], ‘Oxfordshire Appeal Tribunal; Local Tribunal Decisions Upheld’, The Oxford Times, no. 2,863 (25 March 1916), p. 4.

[21] E.C. Godley, ‘Godley, Alfred Denis (1856–1925)’, rev. Richard Smail, ODNB (OUP, 2004) [http://ezproxy.ouls.ox.ac.uk:2117/view/article/33435, accessed 31 Oct 2013].

[22] Matthew D’Ancona, L.W.B. Brockliss, Robin Darwall-Smith and Andrew Hegarty, ‘“Everyone of us is a Magdalen Man”: The College, 1854–1928’, in L.W.B. Brockliss (ed.), Magdalen College Oxford – A History (Oxford: Magdalen College, Oxford, 2008), pp. 452–53.

[23] One of the few anti-Imperialists who remained in Oxford during the High Imperial period was the Fabian Sidney Ball (1857–1918), the Philosophy Fellow of St John’s College, Oxford, who would often remark that Imperialism was the last refuge of a scoundrel, an extension of Dr Johnson’s famous judgement on patriotism.

[24] [Anon.], ‘Oxfordshire Appeal Tribunal; Local Tribunal Decisions Upheld’, The Oxford Times, no. 2,863 (25 March 1916), p. 4.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Kennedy (2001), p. 315.

[27] Ibid., pp. 250–51.

[28] Ibid., p. 306.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., pp. 327–32.

[31] Ibid., p. 329.

[32] John Rae, Conscience and Politics: The British Government and the Conscientious Objector to Military Service 1916–1919 (London: OUP, 1970), p. 199.

[33] John Brett Langstaff, Oxford – 1914 (New York, Washington and Hollywood: Vantage Press, 1965), p. 186.

[34] Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967); The Murray Papers, Liddle Collection, Leeds University: CO 066 (File 5).

[35] Rae (1970), p. 236. Apart from Graham, Rae probably means Norman Monk-Jones (1894–1977), the son of a Congregational Minister who served with the British Red Cross, and Percy Horton (1879–1970), who joined the No-Conscription Fellowship, was an Absolutist, and had been sentenced to two years’ hard labour in Edinburgh after a court martial. He went on to become Ruskin’s Drawing Master at Oxford.

[36] [Anon.], ‘Mr R.B. Graham; Education in the North’, The Times, no. 53,764 (13 February 1957), p. 10.

[37] The whole series of statements was republished by NMWM as a pamphlet, Why I believe in the No More War Movement. By leaders of thought and action in religion, politics, industry, science, education, literature, drama (London, 1929); Richard p. 36, John p. 31.

[38] Wade Davis, Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest, (London: Vintage Books, 2012), p. 472.

[39] Tom Holzel and Audrey Salkeld, The Mystery of Mallory and Irvine (Pimlico: Random House, 2010), p. 340; see also [Anon.], ‘Mr R.B. Graham; Education in the North’, The Times, no. 53,764 (13 February 1957), p. 10.

[40] Davis (2012) pp. 473–74.

[41] John W. Graham, Conscription and Conscience (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1922), pp. 160–61.

[42] [Anon.], ‘Horace Alexander: Gandhi’s Quaker friend whom India honoured’ [Obituary], The Times, no. 63,519 (7 October 1989), p. 12.

[43] [Anon.], ‘Mr Harrison Barrow: A notable Birmingham figure’ [Obituary], The Times, no. 52,547 (16 February 1953), p. 8.

[44] [Anon.], ‘Mr A Barratt Brown’ [Obituary], The Times, no. 50,883 (4 October 1947), p. 7.

[45] [Anon.], ‘News in Brief’, The Times, no. 41,386 (26 January 1917), p. 5.

[46] Peace Pledge Union, ‘Remembering the Men who said No: Roderic Kendall Clark’: https://menwhosaidno.org/men/men_files/c/clark_rk.html (accessed 27 March 2021).

[47] Detailed accounts of his appearance before various tribunals and the results are given in the Imperial War Museum, Lives of the First World War: https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/lifestory/7648022 (accessed 27 March 2022).

[48] See extract from Quaker Dictionary at: http://trilogy.brynmawr.edu/speccoll/dictionary/index.php/EVANS,_Charles_Irwin,_1870-1941 (accessed 27 March 2022).

[49] Birmingham Mail, no. 16,009 (Saturday 21 April 1917), p. 3.

[50] The Annual Monitor For 1919–20, Being an Obituary of Members of the Society of Friends from October 1st, 1917, to September 30th, 1919 (London: Headley Brothers [18 Devonshire St, EC2], 1920), pp. 168–79.

[51] [Anon.], ‘Mr Wilson Harris: Former editor of the “Spectator”’ [obituary], The Times, no. 53,138 (13 Jan 1955), p. 11.

[52] Vera Brittain, ‘Mr Stephen Hobhouse’ [Obituary], The Times, no. 55,046 (4 April 1961), p. 11.

[53] Hobhouse (1918), pp. 20–23.

[54] [Anon.], ‘Mr. Geoffrey Hoyland’ [obituary], The Times, no. 56,357 (25 June 1965), p. 15.

[55] Kennedy (2001), p. 348.

[56] Kennedy (2001), p. 351. Also on-line at: ‘Remembering the men who said no’: https://menwhosaidno.org/men/men_files/l/littleboy_wilfred_%20ernest.html (accessed 12 April 2022).

[57] Barry Mills, Robert J Long (1882–1953) the first Secretary of the Northern Friends Peace Board, Centenary Essays, Northern Friends Peace Board (Bolton: 2013). [https://nfpb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2019/02/robert_long.pdf]

[58] Detailed accounts of his appearance before various tribunals and the results are given in the Imperial War Museum, Lives of the First World War: https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/lifestory/7647020 (accessed 27 March 2022).

[59] Fred Murfin, PRISONERS for PEACE: Account by Fred. J. MURFIN of his Experiences as a CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTOR during the 1914–18 war (Cornwall Area Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), 2014), p. 21.

[60] [Anon.], ‘Mr J.T.W.Newbold’ [obituary]: The Times, no. 49,478 (24 February 1943), p. 7.

[61] [Anon.], ‘A Quaker on War; Defence of the Realm Prosecution; An Intercepted Letter’, The Times, no. 41,016 (19 November 1915), p. 5.

[62] [Anon.], ‘Hubert Peet’ [obituary], The Times, no. 51,892 (6 January 1951), p. 8.

[63] Peter Brock (ed.), These Strange Criminals: An Anthology of Prison Memoirs by Conscientious Objectors from the Great War to the Cold War (Toronto: Toronto UP, 2004), pp. 38–49.

[64] [Anon.], ‘Mr Arnold Rowntree’ [obituary], The Times, no. 52,008 (23 May 1951), p. 8.