Fact file:

Matriculated: 1912

Born: 25 February 1894

Died: 14 January 1921

Regiment: Coldstream Guards

Grave/Memorial: Romsey Abbey Cemetery, Hampshire

Family background

b. 25 February 1894 at 62, Lounds Square, London SW1, as the only child of the Rt Hon. (Anthony) Evelyn Melbourne Ashley, JP, DL, PC (1836–1907), and his second wife, Lady Alice Elizabeth Ashley (née Cole) (1853–1931) (m. 1891). The family lived at Broadlands, near Romsey, Hampshire, a magnificent estate on the banks of the River Test that was acquired by the Palmerston family in 1736 and given its present Palladian style in the 1760s by Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716–83); also 13, Cadogan Square, London SW; and Classiebawn Castle, near Cliffoney, the Mullaghmore Peninsula, Sligo, Ireland, a 10,000-acre estate which Ashley’s father had inherited from his uncle, the Liberal politician and statesman William Cowper-Temple (1811–88), 1st Baron Temple (from 1880). William Cowper-Temple was the stepson of Henry John Temple (1784–1865), 3rd Viscount Palmerston (Prime Minister 1855–58 and 1859–65). At the time of the 1901 Census, 14 servants were employed at Broadlands.

Ashley at OTC Camp (June 1913)

(Photo courtesy of Alan Robinson Esq.; photo © the descendants of Anthony Henry Ashley)

“A photograph cherished by his Magdalen friends shows them both [Ashley and the Prince of Wales] with another College comrade in the O.T.C. camp, the picture of merry joie de vivre. His story is so sad that it can scarcely be set down without tears. But of all those whom the roll and scroll with its Maiorem dilectionem nemo habet honours and records, none leaves a more blamelessly gallant, and none a more amiable, name and memory.”

Parents and antecedents

Ashley’s father was the fourth son of the Liberal reformer and philanthropist Anthony Ashley-Cooper (1801–85), 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, and Lady Emily Caroline Catherine Frances Cowper (1810–72) (m. 1830), the sister of William Cowper-Temple. Ashley’s father graduated from Cambridge in 1858 and from then until 1865 was Private Secretary to Lord Palmerston. A member of Lincoln’s Inn, he was called to the Bar in 1863 and after Palmerston’s death became a barrister on the Oxford Circuit until 1874. Independently wealthy, he devoted most of his time for the next two years to completing the five-volume biography of Lord Palmerston of which Lord Dalling (Henry Bulwer Lytton; 1801–72) had published the first two volumes in 1870. Volume 3 appeared in 1874 and the two final volumes in 1876. As the result of a by-election, Ashley’s father became the Liberal MP for Poole, Dorset, from 1874 to 1880, and at the general election of 1880 he was returned as the Liberal MP for the Isle of Wight. During Gladstone’s second administration (1880–85) he served as Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade (1880–82), Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies (1882–85), and Second Commissioner for Ecclesiastical and Church Estates (1880–85). But in 1886 he broke with Gladstone over home rule for Ireland – which he opposed – and joined the Liberal Unionist Party. However, he never held a parliamentary seat again despite several attempts to do so. He was made a Privy Counsellor in 1891, became a Verderer of the New Forest, one of a group of people whose task is to protect and conserve that area, and was five times Mayor of Romsey (1898–1902). He left £150,613 4s. 8d.

Ashley’s mother was the daughter of William Willoughby Cole (1807–86), 3rd Earl of Enniskillen, a British palaeontologist and Conservative MP for Fermanagh from 1831 to 1840.

Siblings and their families

Through his father’s first marriage (1866) to Sybella Charlotte Farquhar (1846–86), Ashley was the half-brother of:

(1) Wilfrid William (later JP, DL, PC; from 1932 1st Baron Mount Temple of Lee) (1867–1939); married first (1901) Amalia Mary Maud Cassel (1879–1901), two daughters; and then (1914) Muriel Emily (Molly) Spencer (1881–1954);

(2) Sybil Katherine (1869–76);

(3) Lillian Blanche Georgiana (1875–1939); later Pakenham after her marriage in 1895 to Colonel Hercules Arthur Pakenham (later CMG, DL, JP) (1863–1937), one son, two daughters.

Wilfrid William Ashley was described by one anonymous obituarist as “one of the last of that fine, courteous, world-understanding line of Victorians, or rather Edwardians, […] whose appearance stamped them as belonging to quite another era” and by Sir Patrick Hannon, MP (1874–1963), as one of the “great gentlemen of our time”, “in the finest sense of the term an English country squire” and an “exemplary landlord”. He read for a Pass Degree at Magdalen from 1885–88, but left without taking a degree. He then travelled widely, especially in “far-off sporting lands” like Africa and America where he could hunt big game, and served in both the Militia and the Regular Army from 1886 to 1903, ending his career as a Major. During this period he fought in the Second Boer War but was invalided home in 1901. He was “early marked out for political preferment”, and his political career began in 1899, when he was Private Secretary to Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836–1908; Prime Minister 1905–08), the leader of the Liberal opposition. But Campbell-Bannerman believed in home rule for Ireland, whereas Wilfrid William saw republicanism there as one aspect of a world-wide conspiracy against the British Empire, which probably explains why, in 1906, he was elected as Unionist MP for Blackpool with a majority of 3,061 – an unusually large number of votes, given that the Liberals were currently sweeping the country and came to power with a huge parliamentary majority. During the 12 years that Wilfrid William represented the constituency, he succeeded in increasing his electoral lead before moving to the Fylde Division of Liverpool from 1918 to 1922, and finally becoming the MP for the New Forest and Christchurch Division of Hampshire – his home territory – from 1922 to 1932. From 1911 to 1913 he was a Unionist Whip and when war broke out he became the Commanding Officer of the 20th Battalion, the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, until 1915, when he was recalled to Britain from France to become the Personal Private Secretary to the Financial Secretary in the War Office. In 1917 he helped found Comrades of the Great War, a nonpolitical association which represented the rights of ex-servicemen and -women and was one of the four organizations that amalgamated on 15 May 1921 to form the British Legion.

After the war, Wilfrid William opened Broadlands as the venue for the first meeting between British and German industrialists, believing that free trade was a major way of improving relations between Britain and Germany and healing the wounds of the immediate past. In 1922 he became Private Secretary in the Office of Works and Ministry of Transport, where he initiated a much-needed programme to improve Britain’s road network, bridges and tunnels and electricity supply; in 1924 he became the Under-Secretary of State in the War Office; he was made a Privy Councillor in 1924, and from that year to 1929 he was a forward-looking Minister of Transport who pushed forward with his earlier reforms to Britain’s infrastructure – arguably the political achievement for which he will best be remembered. In 1936 he became Chairman of the Military Manoeuvres Committee. After becoming a peer, he remained politically active, but on the right of the political spectrum. He had opposed the creation of an Irish Free State and in the 1930s he chaired the Anti-Socialist and Anti-Communist Union (founded as the Anti-Socialist Union in 1908 and revived after World War One) and at one point he was President of the Navy League (founded in 1894 as a way of promoting the interests of the Royal Navy both inside and outside of Parliament).

After Hitler’s seizure of power Wilfrid William, like a significant section of smart London society, supported Nazi Germany, partly because he saw it as the final stage in Germany’s transformation into a nation state that had begun during the Napoleonic period, and partly because he regarded a strong, re-armed, unified Germany as a bulwark against Bolshevism. Consequently, in September 1935 he helped to found and became the President of the Anglo-German Fellowship, whose aim was to improve relations between Britain and the new Germany, and at first he was pro-appeasement on the grounds that Germany had been badly treated by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and was justified in taking steps to rectify those injustices. Thus, in his last speech to the House of Lords, on 24 February 1937, he spoke out against the Franco-Soviet Pact (ratified 27 March 1936) on the grounds that it would draw Britain into a war with Germany “that nine-tenths of the people in this country abhor”, maintained that, in his view, “Germany has in the past and is now doing what she can to promote good relations between other countries and herself”, and concluded by asserting: “It will not be Germany’s fault if there is war, but the fault of other Powers who have not treated her as she should be treated.” Wilfrid William may have been naïve, but he was not a racist and denounced Nazi Germany’s antisemitism in a speech that he gave as early as March 1933. Moreover, after a diplomatic visit to Germany in June 1937, when he met Hitler in camera, he began to understand the implications of Nazi Germany’s racist policies and to turn more decisively against them. Nevertheless, on 26 February 1938, just two weeks before the Anschluβ of 12 March, he published a letter in The Times that justified Hitler’s desire to unify the German-speaking peoples of Europe, stated that “this sense of nationhood in the German mind today carries with it the recognition of the ‘divine right of other peoples to existence and independence’” and concluded that ‘the integrity of the countries of Eastern Europe is equally in no danger from such a philosophy”. And on 12 October 1938 he was one of the 26 signatories of a letter to The Times that supported the Munich Agreement of 30 September 1938 on the grounds that it was a “rectification of one of the most flagrant injustices” of the Treaty of Versailles and “took nothing from Czechoslovakia to which that country could rightfully lay claim and gave nothing to Germany which could have been rightfully withheld”. But four weeks later, as a protest against the anti-Jewish pogrom of 9 November 1938 that became known as Kristallnacht, he resigned the presidency of the Anglo-German Fellowship, and in his letter of resignation he also denounced Germany’s treatment of Catholics and Lutherans. A High Steward of Romsey, he, like his father and half-brother, is buried in the cemetery there.

Amalia Mary Maud Cassel was the only child of the German-born merchant banker, financier and philanthropist Sir Ernest Joseph Cassel (1852–1921).

Muriel Emily Spencer was the daughter of a clergyman and the former wife (m. 1903; marriage dissolved 1914) of Rear-Admiral the Hon. Arthur Lionel Ochoncar Forbes-Sempill (1877–1962). She proved to be an excellent political hostess at Broadlands.

In 1922, Wilfrid William’s elder daughter, Edwina Cynthia Annette (1901–60), married Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900–79), 1st Baron Romsey (1947), 1st Viscount Mountbatten of Burma (1946), 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (1947) and the last Viceroy of India (1947). He was assassinated by an IRA bomb in his fishing-boat just off the family property at Mullaghmore; three other people also died including a grandson.

Hercules Arthur Pakenham was a professional soldier from 1883 to 1898. In 1906 he became High Sheriff of County Antrim and the Commanding Officer (CO) of the London Irish Rifles. During the first half of the war he was CO of the 11th (Service) Battalion, the Royal Irish Rifles, and during the second half he worked for MI5. A major landowner in County Antrim, he was a member of the Northern Ireland Senate from 1928 to 1937.

Wife and children

At some point in 1915, Ashley became informally engaged to the Hon. Edith Victoria Blanche Winn (1895–1966), but around Christmas 1915 the engagement was broken off and in July 1916 Miss Winn married Guy Randolph Westmacott (later Lieutenant-Colonel, Croix de Guerre, DSO) (1891–1966). He became an officer in the Grenadier Guards in mid-1916 and served as a distinguished intelligence officer during World War Two.

On 6 March 1920, at the British Vice-Consulate in Cannes and the English Church of All Saints, Cap d’Antibes, France, Ashley, though confined to a wheel-chair because of the spinal wound he sustained on 6 May 1916 (q.v.), became the second husband of Albinia Mary Evans-Lombe (1887–1972). She was the elder daughter of a wealthy Norfolk landowner, Major Edward Henry Evans-Lombe (1861–1952) and his wife, Albinia Harriet Evans-Lombe (née Leslie-Melville) (1862–1956) (m. 1886) of Bylaugh Park, Thickthorn and Marlingford Hall, Norfolk, and the widow of Francis William Talbot Clerke, who had been killed in action at Lesboeufs on 26 September 1916 while also serving as a subaltern in the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards. After their marriage Ashley and Albinia lived at Westbrook House, Bromham, near Devizes, Wiltshire, and she continued to live there for the rest of her life and throughout her third marriage, to Group-Captain (later Air Chief Marshal) Edgar Rainey Ludlow-Hewitt (1886–1973).

Albinia Mary Evans-Lombe (1887–1972)

(Photo courtesy of Alan Robinson Esq.; photo © the descendants of Anthony Henry Ashley)

Ashley was stepfather to:

(1) John Edward Longueville (from 1930 Sir, 12th Baronet of Hitcham) (1913–2009); married (1948) Mary Beviss Bond of Natal (1924–98), marriage dissolved in 1986; one son, two daughters;

(2) Rupert Francis Henry (later Group Captain, DFC) (1916–88); married first (1945) Ann Jocelyn Tosswill (1921–2000), marriage dissolved in 1972; one son, two daughters; then (1975) Pamela Emily Bayliss (1925–99).

A photograph of Ashley in his wheelchair shortly before his death (1921). His wife Albinia is seated on the left and his two stepsons, Rupert (sitting) and John (standing), are on the right. The woman in the centre is their nanny.

(Photo courtesy of Alan Robinson Esq.; photo © the descendants of Anthony Henry Ashley)

John Edward Longueville was educated at Eton College and Magdalene College, Cambridge. He gained the rank of Captain while serving in the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry (Territorial Army), fought in the World War Two, and was invested as a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in 1948. Mary Beviss Bond was the daughter of a professional soldier.

A photograph of Albinia, John (on her right) and Rupert (on her left) that must have been taken in c.1921 by Ashley while sitting in his wheel-chair (see the shadow bottom right)

(Photo courtesy of Alan Robinson Esq.; photo © the descendants of Anthony Henry Ashley)

We are told that the families of both Clerke and his brother officer Harry Ashley generally believe that Clerke’s younger son, Rupert, was Ashley’s natural son. If this is the case, then Rupert, who was born in April 1916, must have been conceived around July 1915, i.e. a month or two before Clerke joined the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards in which Ashley had been serving since the outbreak of war (see under E.L. Gibbs). Rupert certainly remembered Ashley, and under the terms of his mother’s will he was the son who inherited a number of Ashley’s personal possessions, including family silver, furniture and letters from the Prince of Wales, of whom Ashley was an exact contemporary and friend at Magdalen (q.v.). Unfortunately, many of those letters were destroyed and only a few from 1913 and 1914 have survived (see the Bibliography below), which are now owned by one of Rupert’s two daughters. Like his elder brother John, Rupert was educated at Eton College and Magdalene College, Cambridge. During World War Two he fought in the RAF.

Education and professional life

Ashley attended the Reverend Churchill’s School, Stonehouse, Broadstairs, Kent (1884–1970; cf. W.G.S. Cadogan, G.A. Loyd, B.O. Moon), from c.1901 to 1907, then Harrow School from 1907 to 1911, after which he spent a period with a private tutor, the Reverend Canon Edward Southwell Garnier (1850–1938), the Rector of Quidenham with Snetterton, who lived at Quidenham Parsonage, Attleborough, Norfolk. Ashley passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1912 and matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 15 October 1912, the same day as Edward, Prince of Wales, who, according to his biographer Frances Donaldson, was “diffident and lonely” when he first arrived at Oxford, finding himself “surrounded by young men who had come up with friends they had made at Eton, Harrow, Winchester or some other public school”. But he soon became friends with Ashley, who was copiously supplied with charm and amiability, and sent him a Magdalen Christmas card in December 1912 that contained a view of the College’s tower.

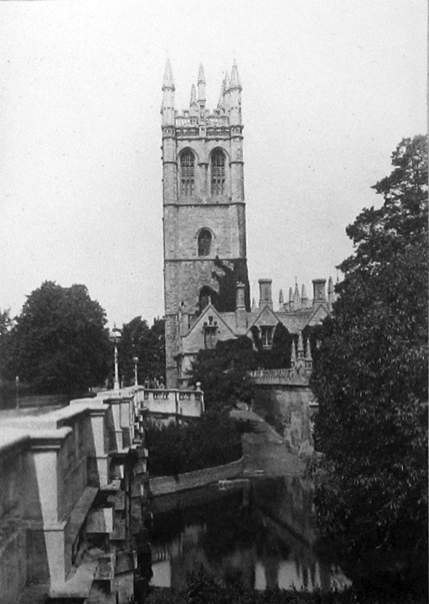

The photo of Magdalen that formed part of the College Christmas card in 1912

By the end of the academic year 1912/1913, the two young men’s friendship had become closer – partly through their membership of the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps (OUOTC) and partly because of their mutual lack of enthusiasm for academic work and preference for such activities as field sports, spectator sports (especially rowing), partying, dancing and pipe-smoking, a hobby, as another Magdalen man had called it, to which Ashley had introduced his friend “Eddie” during their first year at Oxford. When, in the long vacation of 1913, the Prince spent nine weeks improving his German by visiting very close relations in Germany in the company of Cadogan, he sent Ashley two entertaining letters in which he described the high and low points of the tour, to which he had not looked forward at all. On the positive side, he had enjoyed a 700-mile drive through southern and central Germany, the western parts of Austria-Hungary (now the Czech Republic) and Dresden and Leipzig, to Berlin, where he had fun and games in the Luna-Park and the Palais de Danse. On the negative side there was a final “ghastly week” staying with the Kaiser at the palace on Berlin’s Unter den Linden, “where, appearing in one uniform after another, each more dazzling than the last, this cousin received him first sitting on a wooden horse in his own sitting room, and later at dinner, after which he took him to the opera to hear Aida”. The tour also involved a visit to the Prince’s aunt and uncle King Wilhelm and Queen Charlotte of Württemberg in Friedrichshafen, during which he attended the deposed and exiled King Manuel II of Portugal (1889–1932), when he married his cousin Princess Augusta Victoria (1890–1966) in Sigmaringen on 3 September. After his return, on 14 September, he wrote to Ashley from Scotland: “It is ripping to be home again & up here after that 9 weeks hell in Germany & I am out on the hill [deer stalking] or grouse shooting every day, which is glorious.”

Meanwhile, back home in the same year, Ashley took an Additional Responsions Paper on the French politician and historian Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877) – who is now best remembered for his ten-volume history of the French Revolution (1823–27) and his bloody suppression of the Paris Commune of 1871. Ashley passed the examination, and this would permit him to take only one part of the First Public Examination (Classical Literature) in March 1914, when his royal friend was preparing to spend two very enjoyable weeks in northern Norway learning to ski, toboggan and climb mountains. Then, following his success in Responsions, Ashley embarked upon a course of study in Trinity Term 1913 that could have led him to a Pass Degree in 1915 by taking Group E1 (The Elements of Military History and Strategy); but instead, he left without taking a degree in 1914 and, like so many other young men, joined the Army having attended the OTC camp with the Prince of Wales for the second year.

Ashley is second from the left; the short man on his left is the Prince of Wales (the photo was probably taken during Torpids in Spring 1913)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

“Tall – standing six feet four – dark, handsome, graceful, singularly active, indeed a striking figure and one of the best-looking young fellows of his time at Oxford, he had here as everywhere ever so many friends.”

War service

Ashley, who was 6 foot 4 inches, was an enthusiastic member of the OUOTC and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Guards Special Reserve of Officers on 28 January 1914. In July 1914 he was attached to the Coldstream Guards for basic training and he was mobilized as a Second Lieutenant in the Regiment’s 2nd Battalion (see Gibbs) shortly before 28 August 1914, the day when the Prince of Wales, who was doing his basic training as a Subaltern in very insalubrious conditions at Warley Barracks, near Brentwood, Essex, wrote to him to congratulate him (London Gazette, no. 28,879, 25 April 1914, p. 6,694). The 2nd Battalion had been in France since 13 August 1914 as part of the 4th Guards Brigade in the 2nd Division, and had seen action in the Champagne area during the Retreat from Mons (23 August–5 September 1914). But from 19 September until 24 October 1914 Ashley was on the sick list with jaundice, and after being taken ill again on 31 October 1914, he appeared before a Medical Board at Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital, Millbank, London, on 4 November 1914. He was then sent on sick leave suffering from jaundice and enteritis until 3 January 1915, thus missing the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–22 November 1914), in which the 2nd Battalion participated after fighting in the First Battle of the Aisne. But in January 1915 he reported that he was fit for General Service and returned to duty without presenting himself before another Medical Board. So on 22 January 1915 he returned to France and rejoined the 2nd Battalion four days later with a draft of c.200 replacements. On 9 March 1915 he was promoted Lieutenant (LG, no. 29,160, 11 May 1915, p. 4,625), but from 11 to 14 March, according to the diary kept by Lancelot Gibbs, the 2nd Battalion’s Adjutant since 17 November 1914, he spent another period in hospital. Ashley’s Battalion then spent a relatively quiet time in and out of the trenches near Cuinchy; it played no part in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) and only a minor part in the Battle of Festubert (15–25 March 1915), when it suffered only a few casualties. By the end of May, the weather had improved significantly and Lancelot Gibbs’s diary tells us that on 30 May 1915, Ashley, accompanied by six officers from the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards (including Gibbs), went for a ride in the Bois des Dames and tackled some gentle jumps at a local French cavalry school.

Captain Henry Ashley (April 1916) (MS62-BR97-1)

(Photo courtesy of Ms Karen Robson, Hartley Library, University of Southampton; © Broadlands Archives, The Archives, University of Southampton)

On 20 August 1915, the 4th Guards Brigade became the 1st Guards Brigade in the newly formed Guards Division. From 28 August 1915 to 21 September 1915, the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards were in billets at Verchocq, about 13 miles south-west of St Omer, and when the Battle of Loos began on 26 September 1915, the Battalion was in reserve in the old British front line at Loos. But late on 26 September the Battalion moved into the new British front line, and at 16.00 hrs on 27 September it participated in the Divisional attack on Hill 70 as part of the 1st Guards Brigade, on the left of the line, losing 21 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing. It stayed in the line until 30 September and helped to consolidate the new position by bringing in wounded and collecting large quantities of discarded arms and equipment. During its brief first period on the Loos front the Battalion was subjected to heavy shelling and lost a total of 29 ORs killed, wounded and missing, a very low number of casualties in comparison to the other Battalions of the Guards Division. The 2nd Battalion was in the trenches near Loos once more from the evening of 3 October onwards, the day, incidentally, when Ashley was promoted Temporary Captain (confirmed 29 August 1916), and it helped to beat off the bloody German counter-attacks that took place on the afternoon of 8 October, after which, it was estimated, 8,000–9,000 German dead were left on the field. Here is Ross-of-Bladensburg’s brutally frank description of the scene in the British front line after the fighting was over:

The trenches presented a terrible scene of carnage; arms, legs, heads, which had been blown off from their bodies, were heaped up in ghastly piles, numbers of dead British and German soldiers lay about mixed up together blocking communications, the parapets were much damaged and useless, working parties were rebuilding them and trying to bury the dead outside the defences, and all the time bullets and larger projectiles were flying in every direction. It was a veritable pandemonium and confusion and a very dreadful picture of the realities of war. (i, p. 399)

But by 19 October 1915 the fighting in this sector of the front had died down, and on 26 October the entire Division, including the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, was moved to Hesdigneul-lès-Béthune, just south-west of Béthune.

On 30 October Ashley went on leave for an unknown period near the town of Estaires and six miles south-west of Armentières, an even more quiet sector of the front. The 2nd Battalion remained here until 17 February 1916, losing 55 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing during this three-and-a-half-month period. From 17 February to 17 March the Guards Division was in Reserve west of Poperinghe, in the Ypres Sector, and on battlefield courses near Calais, after which it took over from the 6th Division in the Ypres Salient itself, defending a line of badly damaged and waterlogged trenches that extended in an arc from the village of Boesinghe, two miles north of Ypres, to Hooge, about three miles to the east of the city. The three Brigades each spent a 14-day stint in the line, followed by a week in Reserve, and although no major pitched battles took place during this period, a persistent and considerable amount of shelling, sniping and raiding took a steady toll of casualties in the attempt to straighten out the front line which lasted until 20 May 1916. Thanks to this relative lull in the fighting, Ashley was on leave in England in March 1916.

Ashley became a victim of this situation, for on 6 May 1916 he was badly wounded by a shell splinter near Sint Elooi, one of the 89 members of the 2nd Battalion who were killed, wounded and missing during this “uneventful” period. The splinter fractured the 6th thoracic vertebra of his spine and, when he was operated on on 10 May 1916, his spinal cord was found to be partially severed too, causing him to have no control over his lower limbs and to loss of sphincter control. He embarked at Calais for England on 4 June and on the same day was admitted to Lady Ridley’s Hospital for Officers, 10, Carlton House Terrace, St James, London SW1. On 14 June, while resident at 13, Cadogan Square, London SW, he attended a Medical Board at nearby Caxton Hall, and was offered leave equivalent to the loss of two limbs, a gratuity of £250, and a wound pension, initially for a year. He attended further Medical Boards in 1916 and 1917, and when no improvement was found, he was judged to be completely paraplegic as a result of wounds received in action and, on 5 July 1917, permanently unfit for military duty. So he retired on half-pay (7s. per day) on 13 March 1918, and on 13 March 1919 this was extended for another 12 months. On 12 December 1919 he retired on full retirement pay, but by 1919, when he was living at Lilford Hall, Oundle, where he had already spent three months in early 1917, he had begun to get attacks of sudden unconsciousness and convulsions; he had also developed a large bedsore and ulceration over his right hip, and these were causing the blood poisoning that, after five weeks of suffering, hastened his premature death on 14 January 1921, aged 26, at Westbrook House, Bromham, near Devizes, Wiltshire. On 26 January 1921, his mother, Lady Alice Ashley, wrote in a letter to President Warren, with whom she had already corresponded during the past five years:

He loved his life & was able to enjoy it thoroughly, even with its many limitations, & he continued wonderfully strong, up to 3 months ago. The last year of his life was extra happy with his devoted wife, & her two little boys of 7 & 4½ (the youngest boy was his Godson). He loved the children, & was so busily engaged in bringing them up!! He made a good Father & then[,] alas!! that it has only last[ed] one year.

And Warren wrote in Ashley’s obituary:

his radiant friendly nature and courage lived. For many weeks and months he was in hospital. He read and wrote and saw his many friends and played his music, of which he was very fond, and above all devoted himself to cheering the lives of the private soldiers who were his fellow sufferers. […] Then he spent many months in Lord Lilford’s pleasant home, in Northamptonshire, surrounded by wild nature, reading and talking and able to enjoy the sport which he had always loved, of fishing, and even of shooting with success from a chair. He married […] a lady who devoted herself to making his broken career happy and aiding his brave endurance. There have been, and alas! for years there must be, many late lingering victims of the desolating War. Yet the fate of few in its sharp contrast of health and helplessness can be harder than this.

Ashley’s well-attended and very public funeral service took place at Romsey Abbey, Hampshire, on Tuesday 18 January 1921, and both the Romsey Advertiser and the Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette published extensive accounts of the event, of which the following is a synthesized version:

Nearing mid-day a strong detachment from the Hampshire Depot at Winchester […] formed an avenue along the approach to Romsey Abbey Church; whilst a detachment from the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards […] took up its position at the entrance to the north porch of the Abbey. Inside the porch the Romsey Branch of the Comrades of the Great War, of which the deceased was Commandant [for Romsey], formed an avenue up to the entrance to the nave. While the congregation were assembling the church organist […] played ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth’ from the Messiah. The Mayor […] and Corporation of Romsey, having robed at the Town Hall, marched in procession to the Abbey [with the mace bearers carrying draped maces]. The chief mourners had in the meantime been arriving by motor cars, and a great number of people from the town and district attending, the Abbey was well filled when the Vicar […] and surpliced choir met the corpse at the north porch. The coffin, covered with the Union Jack, on which was laid [the] deceased’s cap, belt and sword, was borne up the nave on the shoulders of six employees, the detachment of Coldstream Guards walking on each side of the coffin. The procession up the nave was headed by the churchwardens with draped staves […]. The police […] regulated the traffic at the Abbey and the Cemetery. The service commenced with the chanting of Psalm xxxix, and the hymns sung were ‘Love Divine, all loves excelling’ and ‘Ten thousand times ten thousand’. The Nunc Dimittis was sung as a recessional. The mortal remains having been carried out of the church and placed in the motor hearse, the funeral cortege proceeded to the [Botley Road] cemetery, the detachment from the Hampshire Regiment marching in front with arms reversed. The Mayor and Corporation left the Procession at the Market Place. Nearly a dozen motor cars followed containing mourners. […] As the funeral cortege passed through Romsey it was noticed that every shop was shuttered, whilst private houses had their blinds drawn in silent token to the universal love and esteem in which the deceased was held. All along the route from the Abbey to the cemetery the pavements were lined by the inhabitants. At the entry to the cemetery the cortege was joined by the tenants on the Broadlands Estate […] There was a great concourse of people round the grave, which is near that of the late Hon. Evelyn Ashley ([the] deceased’s father). The inside of the grave was lined with moss, evergreens and white flowers. Rev. A. J. Robertson said the committal, and the coffin having been lowered with a wreath from the widow on the breastplate, the Vicar pronounced the Benediction. The firing party [of 24 men] from the Hampshire Depot then fired three volleys over the grave, after which the [four] buglers sounded the ‘Last Post’ and the ‘Reveille’. Having looked at the coffin, the chief mourners departed, and then the general public came up and looked in, being very much impressed by the whole affair.

Ashley is buried in Grave E4596; and his mother placed a memorial stone in Romsey Abbey or Memorial Gardens. His name was added to Magdalen’s War Memorial just before it was unveiled by the Prince of Wales on 8 February 1921, but it does not appear either on Harrow’s Roll of Honour or in Harrow Memorials of the Great War. He left £32,375 4s. 7d.

The Botley Road Cemetery, Romsey Abbey, Hampshire; Grave E4596

(Photo courtesy of Ms Phoebe Merrick; © Ms Phoebe Merrick)

It was decided after the war that any Commonwealth or British serviceman who had died while in service with the military between 4 August 1914 and 31 August 1921 should, regardless of the cause of death, be accorded war grave status. Although Ashley was in the Army until 12 December 1919 and died on 14 January 1921, he was not accorded war grave status; nor does his name appear on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Roll of Honour; and the Army Council refused to grant his widow remission of death duties because, in their view, his death occurred more than three years after he had left the Army – while a more generous mathematics might have seen the gap between his leaving the Army and his death as a mere 13 months.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

Ashley’s descendants own a collection of 15 letters etc. to Ashley (March 1905–May 1916): a letter from his father (March 1905), an Easter card from his Brigade’s two Chaplains (April 1916); a Christmas card (December 1912) plus 11 letters from the Prince of Wales (1 July 1913–28 September 1914). We are most grateful to Alan Robinson Esq. for being given access to this correspondence (which also includes ten photographs taken by the Prince of Wales at OTC camp in June 1913). Our thanks also go to Ms Phoebe Merrick for providing us with a photo of Ashley’s grave (see above) and to Ms Karen Robson of the Broadlands Archives, the Hartley Library, the University of Southampton, for allowing us to use the photograph of Captain Henry Ashley.

**E.J. Feuchtwanger, ‘Ashley, Wilfrid William, Baron Mount Temple (1867–1939)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 2 (2004), pp. 656–8.

*Reginald Lucas, rev. H.C.G. Matthew, ‘Ashley, (Anthony) Evelyn Melbourne (1836–1907)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 2 (2004), pp. 651–2.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Mr. Evelyn Ashley’, The Times, no. 38,492 (16 November 1907), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Capt. Henry Ashley’, The Romney Advertiser, no. 931 (new series) (21 January 1921), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Funeral of Captain Henry Ashley’, The Salisbury and Winchester Journal and General Advertiser for Wilts, Hants, Dorset, Devon, Somerset and Berks, [no issue no.] (21 January 1921), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Ashley’s Funeral’, The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, no. 5,483 (27 January 1921), p. 9.

[Thomas] H[erbert] W[arren], ‘Captain Anthony Henry Evelyn Ashley’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine,

39, no. 10 (28 January 28), p. 157; reprinted in The Romney Advertiser, no. 933 (new series) (4 February 1921), p. 1.

Ross-of-Bladensburg (1928), i, pp. 371–437.

Mount Temple [Wilfrid William Ashley], ‘Rise of German Nationhood: Compatriots without the Reich’ [letter to the Editor], The Times, no. 47,929 (26 February 1938), p. 8.

‘[Letter] to the Editor’, The Times, no. 48,123 (12 October 1938), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Lord Mount Temple’, The Times, no. 48,348 (4 July 1939), p. 16.

R.D.B., ‘Lord Mount Temple’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48,349 (5 July 1939), p. 16.

Sir Patrick Hannon, MP, ‘Lord Mount Temple’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48,354 (11 July 1939), p. 16.

Frances Donaldson, Edward VIII (1974) (London: Omega Books [Futura Publications Ltd], 1976), pp. 38–49.

Richard Griffiths, Fellow Travellers of the Right: British Enthusiasts for Nazi Germany, 1933–1939, (1980) (London: Faber and Faber [Faber Finds]: 2010), pp. 185–6, 205, 208, 220, 225, 239, 293, 308, 329–30, 338–9.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 172, 297.

David J. Hogg, In Memoriam: Tyntesfield and the First World War (second edition)(Croydon: CPI Group, 2014), pp. 199, 222, 269.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C3/43-61 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to A.H.E. Ashley [1912–1921]).

OUA: UR 2/1/78.

WO95/1215.

WO339/19372.

On-line sources:

Andy Pay, ‘Roll of Honour: Hampshire: Romsey War Memorial’: http://www.roll-of-honour.com/Hampshire/Romsey.html (accessed 5 August 2018).