Fact file:

Matriculation: 1908

Born: 2 October 1889

Died: 29 June 1915

Regiment: Royal Fusiliers

Grave/Memorial: Calvaire (Essex) Military Cemy (to the east of Ploegsteert on the Witteweg); Grave I.0.1.

Family background

b. 2 October 1889 near San Francisco, USA, as the younger son (youngest child) of Edward Martin Knight (1848–1935) and his second ‘wife’ Emily Belinda Knight (née Banfield) (1859–1951). At the time of the 1901 Census Knight was living with his mother, brother and maternal grandfather at 43, Kempe Road, Willesden, London NW6; at the time of the 1911 Census Knight, his mother and brother were boarding with Charles Samuel Ive and his wife at 16, The Avenue, Bedford Park, Chiswick, London W4.

Edward Martin Knight (b. 1848, d. after 1915)

Parents and antecedents

Knight’s paternal great-grandfather George [I] Knight (1775–1845) was the brother of Richard Knight (1768–1844), who had been trained in chemistry by Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) and had been converted by him to Unitarianism. Richard Knight was one of the founders of the British Mineralogical Society (1799–1805) and in its first year he read a paper describing the first method of preparing malleable platinum; he also reported on his analyses of lead and iron ores. In 1807 he was one of the 13 founder members – who included Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829) – of the Geological Society, and was one of the original “Subscribers for life” at the founding of the Royal Institution. After the death of their father William Knight in 1799, Richard and George continued the family’s ironmongery business under the name of ‘R and G Knight’, although their major interest stayed with the manufacture and sale of chemicals and scientific equipment. Sir Humphry Davy recommended to the Board of Agriculture the use of the Knights’ chemical chest for the analysis of soils. They also sold furnaces, retorts, stills, electric batteries, etc.

Richard retired from the business in 1838, but George continued and was joined by his two sons, including Knight’s grandfather George [II] Knight (1812–62), to form “George Knight & Sons, Scientific Instrument Makers and Ironmongers”; the name later became “Manufacturer of Philosophical Instruments”. The business flourished, George [II] began to describe himself as a “gentleman”, and the family moved to 46, Regent Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1, where it lived from 1842 to 1862. Unfortunately, in June 1862 George got into debt and had to sell the business to satisfy his creditors (London Gazette, no. 22,639, 1 July 1962, p. 3,341), so when he died, he left less than £100. But the business was then bought by James How (1821–72), who had worked with George Knight & Sons for upward of 20 years.

Knight’s father was born in Camden Town, north-west London, and after George [II] died and left so little to his family, Edward Martin seems to have begun his working life as a merchant sailor, serving as an apprentice on the Englishman from Liverpool in 1863 and as Third Mate on the Achilles, also from Liverpool, in 1868. On 6 May 1867 he was awarded his “Second Mate Ticket” and then, on 4 September 1869, he was awarded his “Only Mate Ticket” by the Board of Trade. In 1870 he married his first wife Mary Collin (b. 1850, d. probably 1922), and they had five children (three sons, two daughters). In the 1871 Census he gave his occupation as commercial traveller, but over the next decade he had an erratic career. In 1874 he sued for bankruptcy as a draper and auctioneer; in 1876 he sought liquidation with the agreement of creditors as a wringing machine dealer, but later the same year he took out one patent for the improvement of washing machines and another for a new kind of bottle stopper. In 1882 he took out a third patent, this time for an improvement in knife-cleaning machines, and in 1884 he again sued for bankruptcy – this time as a merchant and manufacturer. By the time of the 1881 Census, he and his family were living in Cheetham, an inner-city area of Manchester, where he gave his occupation as machinery agent.

In the mid-1880s Edward Martin left his first family and went to the USA, possibly to avoid the summons to the Royal Courts of Justice that was issued in November 1887 by a former business partner. According to his son George Edward Knight (1873–1949):

Sometime after the end of 1881 when Edward and Mary’s last child was conceived, Edward appears to have come to the end of his tether and he went away. His reasons were never discussed in my presence nor can I find any record of them and I do not know if Mary knew of his intentions […] I was under the impression that he just deserted his family but I now think that it is quite possible that he set off to join his elder brother in San Francisco to try and mend his fortune and met his death on the way. [As noted below, George Edward had no knowledge of his father’s other family]. The immediate effect was that Mary and her five children became the responsibility of her brothers and sisters until the children were old enough to earn their living.

In 1886, though not legally divorced, he had ‘married’ Emily Belinda Banfield, with whom he had two sons in San Francisco. In 1893 he became a naturalized American, giving his occupation as “inventor”. In 1903 he took out a US patent for a mould for making filter pads and at this time he was living in Brooklyn, New York. Meanwhile by the time of the 1891 Census his first family had moved to 8, Cranborne Road, Wavertree, Liverpool, where Mary was still living in 1901. His great-grandson has told us that the two families were unaware of each other’s existence until about 2000.

At some point George returned to England with his second family, and Edward Charles, his eldest son by this ‘marriage’, writing in 1975 outlines what happened:

Shortly after my brother’s [Arthur George’s] arrival, my mother and us babes were packed off back to England and lived with her brother Tom (widowed) and his family in Camberwell. Two or three years later we rejoined my father in Jersey City, New York, and we boys went first to a boarding school in Hempstead, Long Island, and subsequently to a farm day school in Greenwich Village, Long Island. My mother was then free to travel the U. S. with my father and brew coffee to keep him awake in the small hours. In or about 1900, events decreed that we boys should return with my mother to England where we took a Flat in Kensal Rise where we continued our schooling at St Augustine’s (staffed by C of E Sisters).

In 1975 he described his father’s reaction to Arthur George’s death:

Early in 1915, the sad news of my brother’s death in action was received. My mother wrote to convey this to my father – she had an address – he wrote back in the terms one would expect, but since then not a word.

Later, Edward Charles called the military authorities and explained that although their father was still alive, he had deserted his family, was heard of only at irregular intervals, and had no permanent address. But in 1919 Edward Martin Knight was granted a US patent for organic filtering material and at this time his address was Ottawa in Canada. In the US Census of 1920, Edward M. Knight and his, at least third, ‘wife’ Henrietta were living in Brooklyn, New York. Henrietta was originally English and had entered the USA in 1918. In 1924, when filling out a page for the Register of his dead brother’s secondary school, Edward Charles presumed their father to be dead. This was premature since Edward Martin Knight died of fibrosis of the myocardium in Brooklyn on 3 February 1935, when his occupation was given as “inventor” and his general area of business as “water filters”.

Thomas Banfield (1819–1906)

Knight’s mother was the daughter of Thomas Banfield (1819–1906), a publisher’s assistant (i.e. a printer), and Eliza Agnes Banfield (née Bennett) (1822–91). She was trained as a book folder, and her brother, Arthur George Banfield (1857–1938), became a printer compositor. From 1851 to the 1881 Census the family lived at 13, Ireland Yard, EC4, in the Blackfriars area of the City of London, i.e. close to the River Thames, since Thomas worked nearby at the Times printing works in Printing House Square, London E2, and by the time of the 1891 Census, the family had moved to 103, Boyson Road, Walworth, London E17. As Emily Belinda now bore all the responsibility for bringing up and educating her two sons, she took any suitable employment that was available and paid reasonably well. By 1901, she, her two sons, her brother and her widowed father, presumably now retired, had moved to the Willesden address (Willesden being a more up-market suburb in London NW6), probably because she herself was now working for the Hogarth Press, Willesden, London N4. And by the time of the 1911 Census (2 April), the surviving members of the family had moved further west still, and were living at 16, The Avenue, Bedford Park, London W4 (i.e. in London’s first “garden suburb”), near where she was employed as the Manageress of a printing works. Later on still she ran the Rose Tea Rooms, The Cliff, Rottingdean, Sussex.

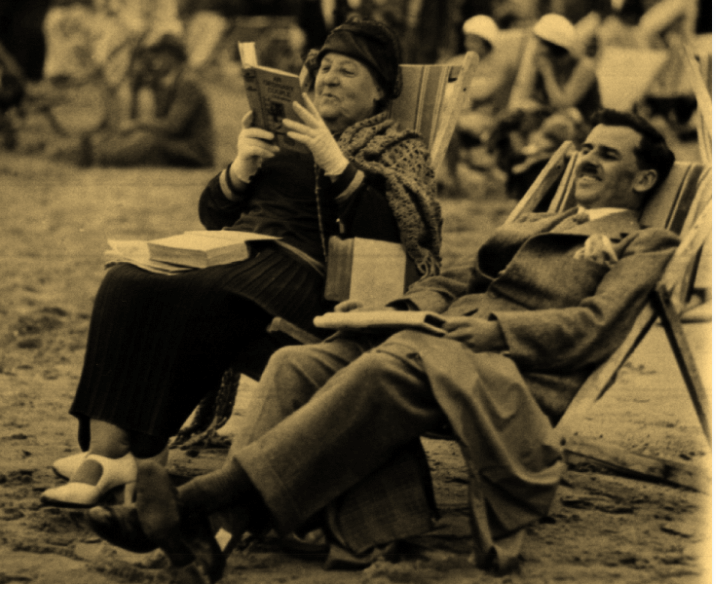

Emily Belinda Knight and her son Edward Charles

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

Siblings and their families

Half-brother of:

(1) May Louise (“Polly”) (1872–1930) (later Jones after her marriage in 1896 to Edward Webster Jones (1867–1939); one son and one daughter;

(2) George Edward (1873–1953), married (1896) Ada Walton (b. 1873, d. probably 1961); one son;

(3) Herbert Watson (1876–1946), married (1901) Gertrude Evelyn Wade (1876–1943); one son, one daughter;

(4) Lily Anderson (1879–1969);

(5) Harry Littlefield (1883–1973), married (1907) May Sharpley; one daughter.

Brother of:

Edward Charles (1888–1979), who married (1913) his cousin Ethel Emily Banfield (1885–1977); three sons, four daughters.

A photo of Edward Martin Knight’s first family (taken in Liverpool, on New Year’s Day 1900). Standing: Lily Knight, Edward Webster Jones, Harry Knight, Herbert Knight. Seated: May Louise (Knight), Shelton Webster Jones, Mary Knight (neé Collin), George Knight. In front: Ada Knight.

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

At the time of the 1901 Census Edward Webster Jones was a stationer and printer, and he and his wife were living with her mother at 10, Cranborne Road, Wavertree, Liverpool; by the time of the 1911 Census they had moved to 47, Plattsville Road, Mosely Hill, Liverpool.

At the time of the 1901 Census George Edward was an author and journalist working for a news agency, and he and his wife were living at 4, Grafton Manor, St Pancras, London W1; by the time of the 1911 Census they had moved to 58, Berkeley Road, Crouch End, London N8.

At the time of the 1901 Census Herbert Watson was a newspaper manager, and he and his wife were living at 48, Gibson Square, Islington, London N1; by the time of the 1911 Census they had moved back north to Birkenhead.

At the time of the 1901 Census Lily Anderson was a visitor at Wyndale, Green Lane, Wavertree, Liverpool; by the time of the 1911 Census she was living with her sister at 47 Plattsville Road, Mosely Hill, Liverpool.

At the time of the 1901 Census Harry was working as an optician’s shop assistant traveller and living with his mother at 8, Cranborne Rd, Wavertree, Liverpool; at the time of the 1911 Census he was living at 12, Glenfield Road, Balham, London SW12 and working as a commercial traveller for Crawford’s Biscuits.

Edward Charles Knight and Arthur George Knight, taken in Hempstead, Long Island, New York

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

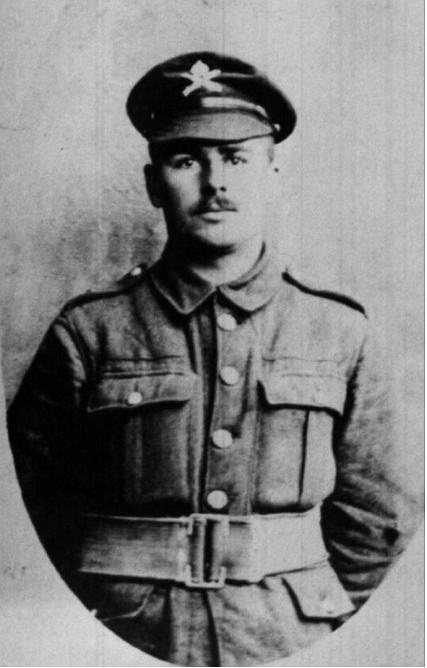

By the time of the 1911 Census, Edward Charles had followed his mother and her parents into the publishing business, but when he married in 1913 he described himself as a commercial traveller in office furniture and gave his address as 26, Gainsborough Road, Bedford Park, London W4. By the time of his brother’s death in action, he and his family were living at 17, Semley Road, Norbury, London SW16. During the war he served as a Private in the Machine Gun Corps.

Private Edward Charles Knight, Machine Gun Corps

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

Ethel Emily Knight was the daughter of Edward Charles’s uncle, Arthur George Banfield (1857–1938), and a Census Sorter in the Civil Service.

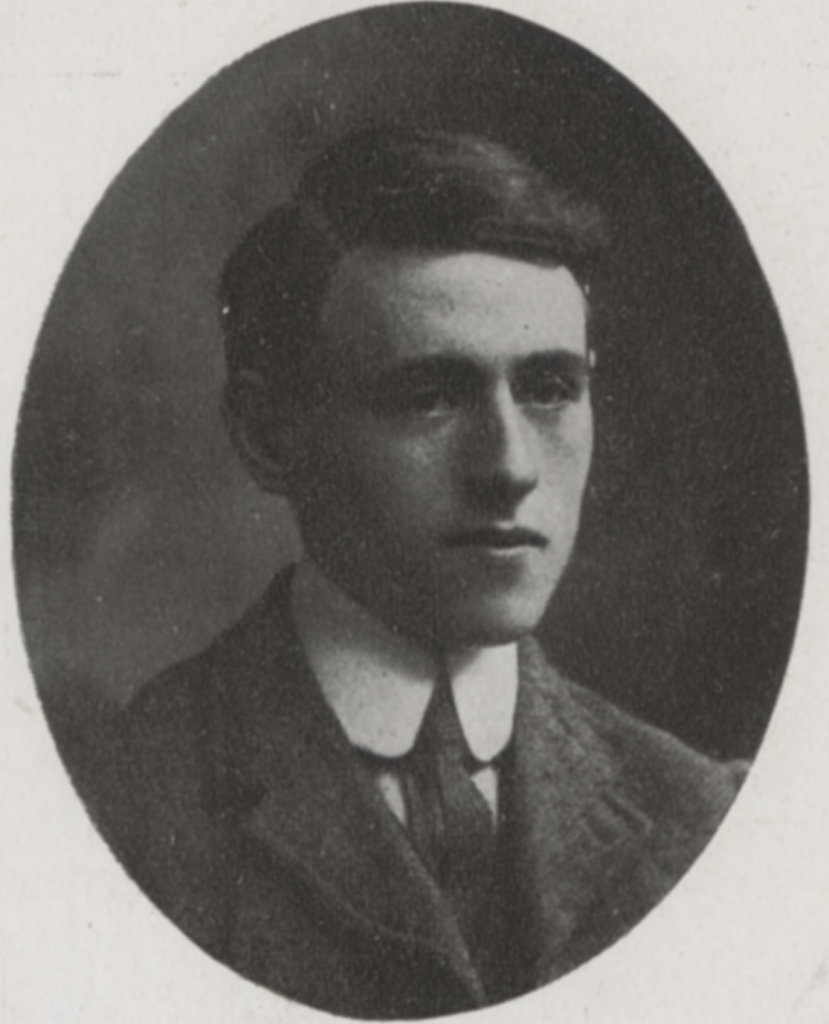

Arthur George Knight, BA

(Dulwich College War Record 1914–1919, p. 145)

“Of keen and distinguished ability, he was too much inclined to follow the lines of his own intellectual interest, and this led to him missing a First Class, though he showed [an] unusual gift for research, in which he would probably have done well.”

Education and professional life

Knight attended a private school in the USA, but when he was 16 and attending Crawford Street LCC School, London SE, he obtained a London County Council intermediate scholarship that enabled him to become a Day Scholar at Dulwich College, in South London (1906–8), where he played in the 2nd Rugby XV (1907–8). When he matriculated at Magdalen, he was financed by means of further scholarships, including a Demyship in Modern History that was awarded him on 14 October 1908. He failed Responsions in September 1908, resat them in Michaelmas Term 1908, and then took the First Public Examination in October 1909 and the Preliminary Examination in Jurisprudence in Michaelmas Term 1909. He was awarded a 2nd in Modern History in Trinity Term 1911 and took his BA on 30 November 1911. He was an excellent long-distance runner and ran in the Hare and Hounds (8 miles) for Magdalen, the cross-country run against Cambridge (1909), and the one mile race against Cambridge (1910 and 1911), earning him two half-blues. After graduating, he ran for the Thames Hare and Hounds.

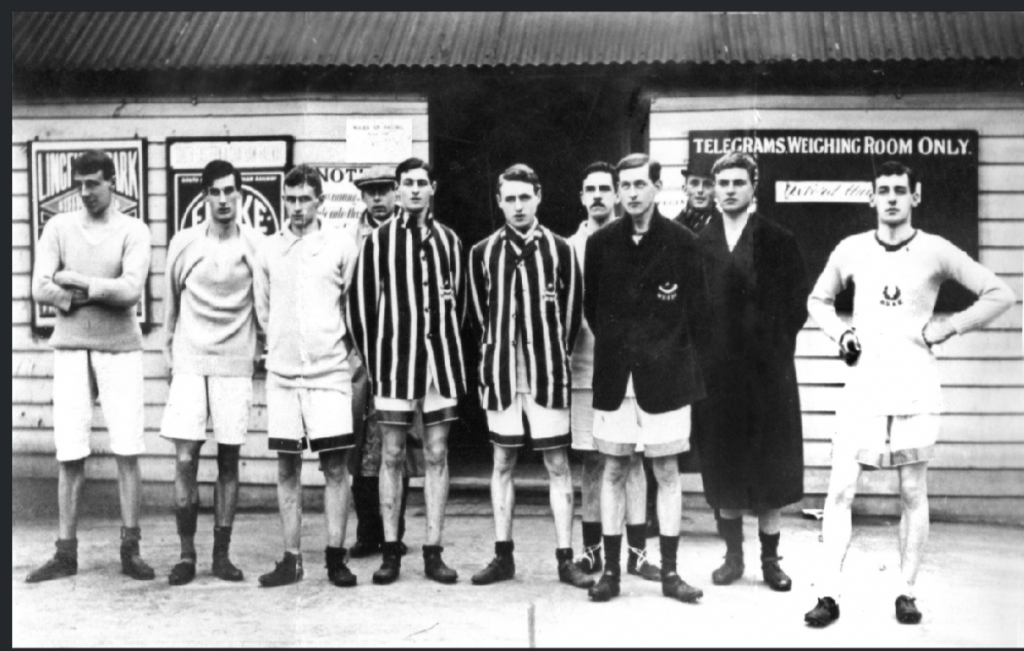

An athletics photograph (laurel wreath emblem), probably of the Oxford University Cross Country Club. Knight is wearing the striped half-blue blazer on the right.

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

At the time of the 1911 Census (2 April), Knight was still living at 16, The Avenue, Bedford Park, London W4, but after graduating he gave his business address as Bedford Road Chambers, 42, Theobalds Road, London WC, the address to which his mother moved later in 1911 and where she lived until her son’s death in 1915, when she moved to nearby 38, Great St James Street, Bedford Row, London WC. After working as a private examinations tutor and travelling (1912–13), Knight became an Assistant Master at Rossall School, Fleetwood, Lancashire, from 1913 to 1914. At about this time he was considering journalism as a career and at his death he left the unfinished and never-published manuscript of a book entitled Comparative Thought in England during the French Revolution. President Warren wrote of him posthumously:

Of keen and distinguished ability, he was too much inclined to follow the lines of his own intellectual interest, and this led to him missing a First Class, though he showed [an] unusual gift for research, in which he would probably have done well.

Arthur George Knight

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

War service

On 8 August 1914, Knight wrote to President Warren, informing him that he was already drilling with the London Rifle Brigade: the 5th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment, a smart Territorial Battalion which recruited from men who worked in the City of London and several of whose officers had been undergraduates at Magdalen (Cable, Donner, E.G. Garton, H.W. Garton, Kennedy, Kirby, Mackenzie, Mackworth, Maclachlan, Maltby, Monteith, Morrison, E.K. Parsons, Pawle, Perssé, Pigot-Moodie, Somers-Smith and Southwell). He wanted to apply for a Commission in that unit via the University. Knight then attested almost immediately, was briefly enlisted as a Private, and on 15 August 1914 applied for a Temporary Commission with that Regiment, but suppressed his origins and claimed that he was “British born”. Although his application was unsuccessful, he was discharged from the London Rifle Brigade on 28 August 1914 so that he could be commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 9th (Service) Battalion of The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) (London Gazette, no. 28,876, 21 August 1914, p. 6,595), and on 10 March 1915 he was promoted Lieutenant (LG, no. 29,133, 16 April 1915, p. 3,723).

A group photograph of the 9th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) with Knight sitting seventh from the left in the second row holding a swagger stick

(Courtesy of Ken Maxwell)

Before leaving for Southampton on 31 May 1915, the Battalion trained at Colchester and Aldershot, and in February Knight represented it in the Hare and Hounds at the Army Sports that was held at Folkestone, Kent, and came in first. The Battalion arrived in Boulogne on 1 June 1915 as part of the 36th Infantry Brigade, 12th Division. On 2 June it travelled by rail to Wizernes, just east of St-Omer, and then trained at La Becque until 6 June. From 10 to 15 June it was at La Chapelle d’Armentières learning about trench warfare and it then marched to the area of Le Bizet, “117 yds away from Belgium”, as he said in a letter to his mother that he wrote from billets on 27 June 1915. On the following day it went into the trenches east of Ploegsteert for a four-day stint, where he and another officer were “in charge of a fort or advanced work very close to the lines & the Germans”. On the same day he wrote another letter to his mother:

Dearest Mater, Can’t write a long letter after all, as there is such a lot to do here with a green officer looking after green men in a very novel position that I have little time for anything but eating and sleeping. As I told you, we are in a sort of fort with the Germans very close at hand – and I find myself transformed in a moment into an engineer planning to repair and improve the defences, a mortar sniper seeking methods to circumvent and destroy the Hunnish sniper, a wet nurse for my men, more or less helpless – everything new. I have to learn my job & carry on at the same time! However, I have been doing much the same thing for a long time, so that I am fairly used to it. Your parcel arrived just in time before I started for the trenches. Everything in it – and I could not tell what came from whom – was a thing I wanted. Do you know what I wish you could do some time, not at once, but when you would like to make a present to my platoon. I have seen some big tins of Mackintoshes Toffee – about 4 lbs I should think – the ordinary Mack’s Toffee. Would you send one of those. They would love it, and I should like to know that it came from you to them. Good bye, for a little time, little mother. I shall be back soon with a voice like a snapdragon.

But at 02.30 hours on 29 June 1915, Knight, together with three ORs (other ranks), was killed in action, aged 25, when the Battalion came under heavy fire and he was going to the assistance of one of his men. Although he is never mentioned by name in the Battalion’s War Diary, Knight is definitely the officer who was buried near Essex HQ Farm, Le Bizet, at 18.15 hours on the same day. He is now buried in Calvaire (Essex) Military Cemetery (to the east of Ploegsteert on the Witteweg), Grave I.0.1. The inscription reads: “A verrye parfit gentil knyghte” (line 13 of ‘The Knight’ from the Prologue of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales). He left £42 7s. 3d. but owed £15 1s. 0d., which his family gradually paid, including the cost of a .38 automatic pistol (£4), a holster (6s. 6d.), and 50 cartridges (5s.), all from Harrods. As his mother “was not largely dependent” upon Knight for financial support, she received no pension from the Army.

Calvaire (Essex) Military Cemetery (to the east of Ploegsteert on the Witteweg); Grave I.0.1

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Ken Maxwell, Knight’s great-nephew, for providing us with a great deal of family information, including most of the photographs and the four letters which Knight wrote from the front.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant A.G. Knight’ [obituary], The Times, no. 40,897 (3 July 1915), p. 6.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, extra number (5 November 1915), p. 17.

Photo, The War Illustrated, vol. IV: The Summer Campaign – 1915 (London: The Amalgamated Press, 1916), p. 1,431.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Arthur George Knight’ [obituary], Dulwich College Roll of Honour (London: J.J. Keliher & Co. Ltd [The Marshalsea Press], 1923), pp. 145–6.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/764 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to A.G. Knight [1914]).

MCA: MC:P179 (Papers of Arthur George Knight (1889–1915))

MCA: MC:P179/MS1/4–7 (Transcripts and photocopies of four letters from Knight to his mother [1915]).

OUA: UR 2/1/66.

WO95/1857.

WO339/11370.

On-line sources:

Brian Stevenson, [history of the Knight and how business], Micscape Magazine (November 2012): http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artnov12/bs-HowJ.pdf (accessed 10 January 2019).