Fact file:

Matriculated: 1899

Born: 5 October 1881

Died: 1 May 1915

Regiment: Monmouthshire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Sanctuary Wood Cemetery: V.L.16

Family background

b. 5 October 1881 in Dowlais, Glamorgan, as the only son of Edward Pritchard Martin, JP (1844–1910) and Margaret Martin (1847–1911) (née James) (m. 1870). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at Gwenllyn Uchaf, Merthyr Tydfil (three servants); it moved to The Hill, Abergavenny, Monmouthshire (Sir Fynwy; see below), in 1902 where, at the time of the 1911 Census, the family employed five servants.

Parents and antecedents

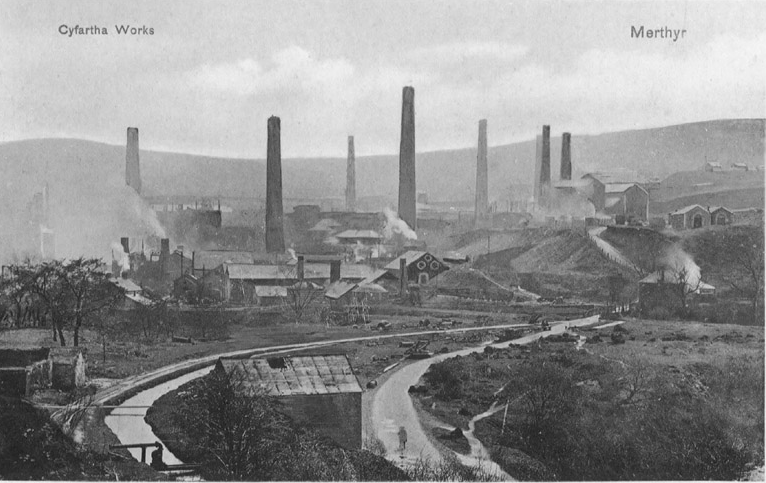

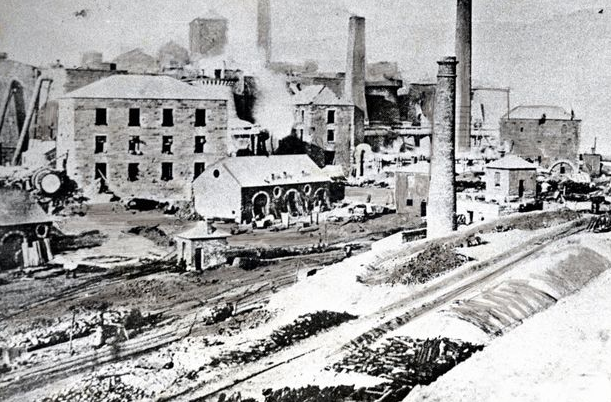

The family traces its roots back to Hugh Martin (1534–75) of Thackthwaite, Cumberland, but Edward, Charles’s father, was a mining engineer whose father, George Martin (1813–87), had, for 58 years, been the collieries’ agent to the Dowlais Iron Company (DIC, founded 1759), one of world’s great industrial concerns in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The DIC expanded as a result of the railway boom of the 1820s to 1840s and by 1836–37 was producing 20,000 tons of rails p.a. for railways all over the world: by 1845 its 17 blast furnaces employed 7,300 men, women and children. Thanks largely to the legendary Scottish engineer William Menelaus (1818–82), who, after a decade of stagnation for DIC, had joined it in 1851 as its Engineer Manager in charge of mills and forges and become its General Manager in 1855, the DIC became the most important iron works in South Wales during the second half of the nineteenth century. Between 1863 and 1882 it is estimated that the Company’s profits averaged c.£120,000 p.a. Edward Martin also worked for the DIC, becoming its Deputy General Manager in 1869, and then moved across to the Cwmavon Works and the Blaenavon Iron Works. In 1882, a year when DIC made a profit of £192,441 (equivalent to over £5.5 million in 2005), Edward returned to the expanding company as General Manager after Menelaus’s death, and from 1887 to 1895 he supervised the planning and construction of the Dowlais-Cardiff Works on Cardiff Moors.

Edward, like Menelaus, acquired the reputation of being an innovative modernizer, and was well-respected both in his profession and the county as a whole (Bessemer Gold Medal of the Iron and Steel Institute 1884, President of the Iron and Steel Institute 1897–98, President of the South Wales Institute of Engineers, President of the Monmouth and South Wales Colliery-Owners’ Association, High Sheriff of Monmouthshire 1903). After the DIC merged with Arthur Keen’s Patent Nut and Bolt Co. (1901) to form Guest, Keen and Co., and then with Nettlefolds (1902) to form Guest Keen & Nettlefolds, Edward became Vice-Chairman and Managing Director of the new company (which started with a capital of £3,000,000). As such, he would have known the (slightly younger) Edward Steer (1851–1927), the father of G.P. Steer. In 1902, he retired from active management while keeping his seat on the Board, and acquired The Hill, a magnificent country house on the edge of the National Park and at the foot of the Deri Mountain (sold 1917; let for ten years in the 1930s to Dr Arthur Leigh Tatham and Mrs Elinor Gertrude Tatham, the brother-in-law and sister of A.C. Hobson).

Charles’s mother, Margaret, was the daughter of Charles Herbert James (1817–90), the son of a maltster of Merthyr Tydfil. After being educated at Taliesin Williams’s School, Merthyr Tydfil, and Goulstone’s boarding school at Bristol (1830–32), Charles Herbert was articled to William Perkins and qualified as a solicitor in 1838. Raised as a Wesleyan, he later became a Unitarian and President of the Unitarian Association and was active in the civic life of Merthyr Tydfil. He chaired the town’s Science and Arts Committee, enthusiastically supported its library, and became its Liberal MP from 1880 to 1888.

Martin’s maternal grandmother Sarah Thomas (1817–1897) was the sister of C.H. Davies’s grandfather, Charles Thomas (1822–1909), and another of their sisters, Cecile Thomas (1818–1910), was the mother of Magdalen’s President Warren.

This means that Martin and Davies were second cousins.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Clara Isabella (1874–1952);

(2) Sarah Bertha Enid (1875–1912); later Ferguson after her marriage in 1902 to Victor Ferguson (1866–1956); one son;

(3) Mary Harriette Mabel (1876–1957); later Barnard after her marriage in 1900 to Samuel Barnard (1863–1943); two sons, two daughters;

(4) Ann(i)e Beatrice (1880–1958); later Cresswell after her marriage in 1904 to Stuart Cornwallis Cresswell (1869–1959); one child;

(5) Jessie Margaret (1886–1962); later Munro after her marriage in 1911 to Patrick Munro (1883–1943).

Samuel Barnard was a mathematician who studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, from 1882 to 1885, graduated as 4th Wrangler, and became a Fellow in 1886. In September 1888 he became an assistant master at Rugby School and between 1903 and 1936 he and the mathematician James Mark Childs (1871–1960) authored a good number of substantial algebra and geometry textbooks for use in schools and universities.

Stuart Cornwallis Cresswell was a surgeon.

Patrick Munro was an Oxford Rugby Blue (1903–05) who went on to play for Scotland (1905–07 and 1911; Captain 1911). He entered the Sudan Civil Service and became Governor of Darfur (1923–24) and Khartoum (1925–29). After leaving the service he became the Conservative MP for Llandaff and Barry (1931–43).

Wife and child

In 1912 Martin married Beatrice Elise Hanbury(-)Williams (1885–1971). They had one son and lived at Nantoer, Abergavenny, and Manor House, Butters Marston, Warwickshire.

Beatrice Elise came from a distinguished Welsh family that had been in the iron business since the late seventeenth century. She was the niece of Sir John Hanbury-Williams (1859–1946), head of the British Military Mission to the Russian High Command during the war. Her later name was later Solly-Flood after her marriage in 1916 to Arthur Solly-Flood (later Major-General, CB, CMG, DSO) (1871–1940).

Charles and Beatrice’s son was Charles Edward Capel (1913–98), who married (1936) Margery Violet Edlin (1910–47); they had one boy and one girl. His second wife (m. 1949) was Pamela Rachel Palles Sword (née Rydon) (b. 1918, d. 1977 in Tangier), marriage dissolved; he then (1955) married Joy Angela M. Lazzolo Frankau (1920–2011).

Charles Edward Capel Martin attended Eton College (c.1926–c.1931), and while he was there he ran illicit motorcycles. He began his driving career as an amateur racing driver in 1932, on Southport Sands, Lancashire, while he was an apprentice at Austin’s. But his real career as a racing driver began in 1934, when he came fourth at Le Mans. In the following year, he and his friend Charles Brackenbury (1907–59) won the Biennial Cup at Le Mans, France, and in 1936 he won the Brooklands 500 mile race at Brooklands, Surrey. Other successes followed all over Europe in the years leading up to the outbreak of war. His obituarist described him as a “cheerful extrovert” who drove “with enthusiastic verve” and as someone who was “absolutely in the spirit of pre-war racing”.

During World War Two he was commissioned Acting Sub-Lieutenant (RNVR) on 19 April 1940, became a member of Coastal Forces, and was the First Lieutenant on M[otor] G[un] B[oat] 59 from 29 October 1940 to March 1942, during which time he was promoted Temporary Lieutenant (RNVR) on 19 April 1941. He then spent a “frustrating year” from March 1942 to November 1943 as Captain of the MGB 318, a C-type Fairmile MGB with a wooden hull that was part of the 15th MGB Flotilla. This Flotilla was based at Dartmouth and consisted from 1940 to 1945 of MGBs 318, 502, 503 and 718 and the MASB 36. It was known as “SOE’s Private Navy” because its main tasks consisted in landing stores, mail and agents on the Brittany coast for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and bringing back returning agents, downed aircrew and other fugitives.

The tasks were difficult, hazardous, and by no means easy to carry out. For example, during the nights of 9, 11, 14 and 15 October 1942 Charles Edward was involved in four failed attempts to land stores in France. On the first date, high seas and winds forced the MGB 318 and 328 to return to Dartmouth; on the second, the two MGBs got close in to the blacked-out French coast but were prevented from landing their cargo by uncharted rocks, leaving Charles Edward “shaken”; on the third, the operation had to be abandoned because of time-tabling problems; and on the fourth, unexpectedly difficult weather problems made it impossible to get the cargo onto the shore so that the crew were forced to return to England yet again with their mission unaccomplished. Charles Edward undertook similar operations with mixed results at intervals throughout 1943 and on 18 January 1944 he was awarded the DSC for his 13 operations to the enemy coast on behalf of the SOE as Commanding Officer of MGB 318 – “the majority of which were carried out in weather conditions which precluded normal Coastal Forces op[eration]s” and all but two of which “necessitated penetrating deeply at night into the rocky, shoal and strong tidal waters guarding the north coast of France west of the Cherbourg Peninsula”. The citation freely acknowledged that “a high degree of skill and courage [was] essential to have carried out this number of expeditions close in shore, each of which entail[ed] considerable risk” and declared that Charles Edward’s “capabilities as a seaman during the course of these op[eration]s” had been “outstanding”. It continued: he was “twice in action with enemy trawlers”, when he showed “great coolness and judgment” and:

on two of the operations in question the ship was caught in water conditions which ultimately reached full Gale Force: one in dangerous proximity to enemy waters towards daylight and one on a lee shore. It was due to Lieutenant Martin’s seamanship and the efficiency of his crew [two of whom were awarded the DSM] that his ship was saved from foundering and subsequently made port, albeit damaged.

In January 1944 Charles Edward became Captain of the fast minesweeper HMS Grey Wolf, which had been recently converted from S[team] G[un] B[oat] 8 (commissioned on 17 April 1942) and turned into one of the seven all-steel craft that formed the 1st SGB Flotilla. The flotilla was based at Newhaven, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander (later Sir) Robert Scott (1909–89), the son of the Antarctic explorer. Like the German E-Boats, SGBs combined the functions of an MGB with those of an MTB and were used against their German counterparts in the English Channel during the run-up to D-Day. In June 1944, Charles Edward was awarded the US Legion of Merit for services in the Bay of the Seine at the time of the D-Day landings. After the war he returned to motor-racing and became a Vice-President of the Brooklands Society.

Charles’s third wife, Joy Frankau, was the niece of Gilbert Frankau (1884–1952), the popular novelist and poet of World War One. She was previously married (in 1945) to the society portraitist, sculptor and magazine illustrator Vasco V. Lazzolo (1915–84), aka Victor Lazzolo. Lazzolo was an intimate friend of the osteopath Dr Stephen Ward (1912–63) and one of the few people who were prepared to give evidence on Ward’s behalf when he was brought to trial in July 1963 during the Profumo affair. In the 1940s Joy was becoming moderately well-known for her appearances in such films as Tilly of Bloomsbury (1940), Notorious Gentleman (1945), Trojan Brothers (1946), The Turners of Prospect Road (1946), The Gay Lady (1949), Old Mother Riley’s New Venture (1949) and Old Mother Riley, Headmistress (1950).

Education and professional life

From c.1888 to 1895 Martin attended Oakfield House School, Rugby, whose headmaster was the Reverend John Monteith Furness (c.1826–1909). He then moved to Eton College from 1895 to 1899, where, according to a letter written by his wife after his death, he found most subjects boring and achieved few good results except when he was allowed to go his own way. The other boys regarded him as “modest, simple-minded and rather shy” and he lacked “the school accomplishments which make boy heroes”. He may have been moved to apply to Magdalen because President Warren was a cousin of his mother’s, and he matriculated there as a Commoner to study Natural Science on 10 October 1899, having passed Responsions in September. He took an additional paper in Mathematics (Algebra and Geometry) in Hilary Term 1901 and passed the rest of the First Public Examination (Holy Scripture) in Trinity Term 1902. But he had begun to read for an Honours degree in Natural Sciences in Michaelmas Term 1900, when he passed the Preliminary Examination in Chemistry; and in Trinity and Michaelmas Terms 1901, he passed the Preliminary Examinations in Botany and Mechanics and Physics respectively. Being a keen field naturalist with a love of the outdoors, he decided to specialize in Zoology and spent Trinity Term 1903 studying Natural Science in Germany, becoming fluent in the language in the process. He was awarded a 2nd in Zoology in Trinity Term 1904 and he took his BA on 10 November 1904.

His Eton obituarist noted that “his real life’s work began after his degree”, and from 1904 to 1906 he stayed in Oxford as a postgraduate student, though it is not clear how he managed to fund his studies – most probably from private means. For some of his time in Oxford Martin shared digs with N.G. Chamberlain. In 1905 he was elected a Life Fellow of the Zoological Society of London, for which you had to have a recommendation from three existing Fellows, and he finally took his MA on 18 February 1911. Having been an introverted boy while at school, Martin became something of a split personality while at university. In order to fit in with Magdalen’s prevailing undergraduate ethos of sport-centredness, he seems to have adopted the persona of an ebullient “hearty” or “blood”, i.e. a “cheery”, keen, all-round sportsman who loved the hunting saddle and helped to start the Magdalen College Beagles (see P.V. Heath). But he also had a very serious scientific side and his obituarists were clearly bemused by his contradictory character. On the one hand, they described him as being like “a great healthy youth full of the spirit of adventure” who refused to be “trammelled by conventions and accepted standards”, as the eternal boy, “lighthearted and jolly and lovable” who was an infuriatingly poor time-keeper and could be “erratic and exasperatingly elusive in his ordinary life”. But on the other hand, they perceived that “research was a great quest to which he had devoted his life” and that his “mask of carelessness […] concealed a noble seriousness of purpose”, an immense patience “when he was in the laboratory”, a “very remarkable intellectual power and ‘grip’”, “a will of iron”, “a very independent turn of mind”, a “quality of genius”, “the spirit of a pioneer” and “the mind of a savant”. So it seems that Martin’s scientific talents began to emerge in earnest only after he had overcome his need to conform, been awarded an undistinguished degree in Zoology, and emerged from the protective persona that shielded him whilst simultaneously assuring him of a place in the “hearty” undergraduate culture of Edwardian Magdalen. With great and particular accuracy, one of his obituarists would describe him as “the real student who develops after, rather than before his degree”.

Thanks to a recommendation from Robert Theodore Gunther (1869–1940), Magdalen’s Science Fellow from 1896 to 1928, whose specialism was Zoology and who founded Oxford’s Museum of Science (1926–30), Sir John Murray (1841–1914: the Scottish marine biologist who is regarded as the father of modern oceanography) invited Martin to co-operate in the survey of the freshwater lochs of Scotland by working at Loch Tay, in the central Scottish highlands, during the long vacation of 1905. In October 1906 Martin was elected to the Biological Scholarship at the German-run Stazione Zoologica in Naples. The institute was by then the Mecca of Europe’s most prominent marine biologists, having been founded in 1872 by the famous German zoologist and Darwinist Anton Dohrn (1840–1909), with whom Martin became “an intimate fellow-worker”. Before taking up a post at Glasgow University on 1 October 1907 as the Junior Assistant to the Scottish embryologist John Graham Kerr (1869–1957; later Sir), the Regius Professor of Zoology at Glasgow (1902–35), Martin was briefly in charge of the privately run Eustace Gurney laboratory at Sutton Broad, Norfolk (founded 1903). He also gave lectures at Oxford and Cambridge and in October 1908 he may have been one of two runners-up singled out for praise in the competition for Oxford’s prestigious Rolleston Memorial Prize. The prize, which still exists, was founded in 1883 in memory of George Rolleston (1829–81), the Linacre Professor of Physiology, and was awarded for original research by young postgraduates in Animal and Vegetable Morphology, Physiology and Pathology, and Anthropology. In 1910 Martin carried off the prize itself. Between 1907 and 1914 18 publications bearing his name appeared in scientific journals, and he allegedly acquired a “European reputation” as a scientific “investigator of a very high order”; he was deemed to have a “distinguished career” ahead of him.

Martin stayed at Glasgow for four years, teaching elementary Zoology to large classes of medical students. Professor Kerr grew very fond of him and thought very highly of him indeed, later writing that he regarded him

as intellectually one of the biggest men I had ever met. There was no-one of his generation of young Zoologists who seemed to me to present greater possibilities of accomplishing really big things. And of course we here all loved his personality.

While at Glasgow, he began to produce his stream of publishable research – mainly on Protozoology, defined as “the study of the structure and life-history of those low and minute forms of animal life whose vital processes are almost beyond the limits of microscopic vision”. He began with the Turbellaria (1907–09) and passed to the Acinetaria, on which he collaborated, with special reference to fowl parasites, with Muriel Robertson (1883–1973), then Junior Assistant to the Professor of Protozoology at the University of London (1909–11). But his father’s sudden death in September 1910 caused him to resign his academic post with effect from July 1911 and return to Abergavenny in order to assume family responsibilities.

Once back in Wales, Martin began to enjoy the pleasures of life as a sporting gentleman and country squire. Besides marrying the very eligible daughter of a prominent local family on 11 June 1912, he regularly hunted with foxhounds and was Master of the Crickhowell Harriers. But his scientific friends hoped that he would eventually combine this way of life with research in the private laboratory that he had installed in his home for “he bade fair to be […] one of that type to which English science owes so much, the gentleman of independent means who pursues it for its own sake and at the dictates of natural predilection and passion”. This hope was fulfilled and during the last phase of his life Martin’s research interests were mainly centred on pathogenic protozoa. He worked partly as a voluntary worker in the Lister Institute, founded in 1891 as part of Edinburgh University; partly in a similar capacity in the Protozoology Department of the Rothamsted Experimental Station (now Rothamsted Research), Britain’s oldest agricultural research station (founded 1843), near Harpenden, Hertfordshire; and partly, as his scientific friends had hoped, in his own laboratory. According to Sir John Russell (1872–1965), Director of Rothamsted Station (1912–43), he “designed ingenious methods for the isolation and collection of soil organisms” and “discovered and attacked the remarkable Flagellate Protozoa that lurk in ‘Sick Soils’, a matter of very great importance to agriculturists and horticulturists”. In his obituary of 1916, Russell, who had taken some trouble to collect his data, was fulsome in his praise of Martin’s achievements:

The great characteristic of Martin’s work was the freshness of his outlook. He never would be bound by tradition or convention, or even by time or circumstance. His work, therefore, was really original; he looked at the problem from a new point of view, attacked [it] in a new way, and always got an interesting result. This was well shown in his work at Rothamsted. He was at once attracted by the hypothesis that soil protozoa constitute one of the factors keeping down the bacterial numbers in the soil, and with characteristic enthusiasm he speedily struck a way through the experimental difficulties with which the subject bristled. He devised a method which for the first time demonstrated the presence of trophic amoeba in the soil and isolated and studied typical organisms present. His naturalist’s instincts led him to make some very shrewd faunistic observations, which are being fully confirmed by later work.

He was a member of the Savile and the Oxford and Cambridge Clubs.

Military and war service

It is possible that Martin was a member of the Oxford University Volunteer Rifle Corps while he was at Magdalen, but it is certain that he joined the University Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) while he was a Demonstrator at Glasgow, and he was gazetted Second Lieutenant (unattached) on 12 October 1909 (London Gazette, no. 28,300, 22 October 1909, p. 7,766). After returning to Wales, Martin, who was 6 foot 1 inch tall, applied for a Territorial Commission on 3 April 1912, resigned his OTC Commission on 20 April 1912, and joined the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment (Territorial Force) on 5 June 1912 (LG, no. 28,614, 4 June 1912, p. 4,044). In 1913, he qualified at the Hythe School of Musketry, the best of its kind in Britain, and became his Battalion’s Machine-Gun Officer and musketry specialist. On 25 October 1914 he addressed all of its officers and non-commissioned officers on the conduct of range practices.

Charles Herbert George Martin, BA MA FZA : detail from a group photo of the officers of the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, the Monmouthshire Regiment, probably just before leaving for France in February 1915.

When Martin’s Battalion was mobilized on 4 August 1914, he was immediately made its Assistant Adjutant on 5 August and promoted Lieutenant on 29 August 1914. The Battalion was selected for attachment to the Regular Army during the autumn manoeuvres of 1914 and trained at Oswestry, Shropshire, and Northampton until 31 October 1914. It was then sent to the Grundisburgh area of Suffolk, where it worked on defensive trenches and coastal defences until 10 January 1915. After several more weeks of training in the Cambridge area, the Battalion embarked at Southampton on 13 February and arrived at Le Havre on 15 February as part of the 83rd Brigade, in the 28th Division. Then, on 12 March 1915, after training near Bailleul in the techniques of trench warfare for a further four weeks, the Battalion went to the relatively quiet trenches on the western slope of the north–south Messines–Wijtschate Ridge (Kemmel-Ploegsteert). It took its first casualty here on 15 March and thereafter suffered a slow but steady stream of casualties before coming out of the line on 2 April. After resting for a few days, the Battalion was sent northwards via Ypres on 8 April to trenches east and south-east of Polygon Wood, near Frezenberg (cf. R.H.P. Howard), in the Zonnebeke sector of the Ypres Salient, where it stayed until 12 April. After five days’ rest in Ypres, the Battalion returned to the same trenches on 18 April and held them for 17 days without relief during the second half of the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915), taking numerous casualties.

On 1 May 1915 Martin became the Battalion’s second officer casualty when he was killed in action here during fierce hand-to-hand fighting, aged 33. His Commanding Officer later wrote:

He was a great loss: he was an officer greatly beloved by his own men – “My people!” as he always called them – and a keen machine-gunner. He had made a name for himself before the War in the world of science and applied himself with characteristic thoroughness to the study of his favourite weapon.

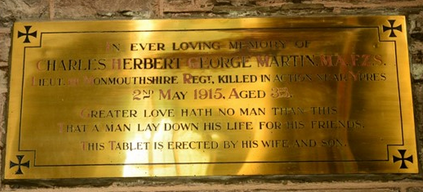

The Battalion’s position became increasingly exposed because of German advances further to the north of the Ypres Salient and it was evacuated on 3 May when it was forced to withdraw to a new front line near Frezenberg. Here it took part in four more days of fierce fighting until, by 8 May, only four officers and c.130 other members of the Battalion remained. Martin is buried in Sanctuary Wood Cemetery, east of Ypres, Grave V.L.16. He is commemorated on a brass plaque in St Mary’s Church, Abergavenny, that was put up by his wife and son and on the town’s War Memorial.

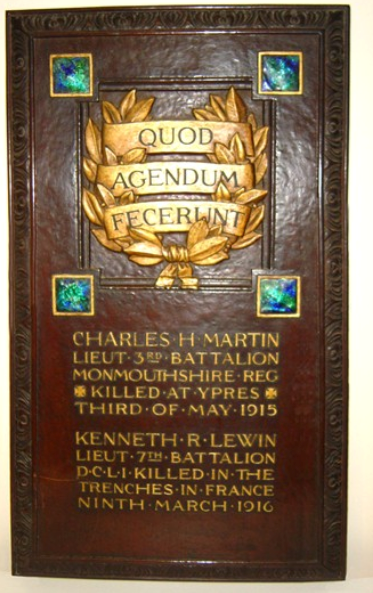

One other member of the Rothamsted Research Station died in the war: Kenneth Robert Lewin (1889–1916), a Project Professor there, whose future as a research scientist was possibly even brighter than Martin’s and who collaborated with him in 1914 on two publications on soil protozoology (see the Bibliography). He was killed in action on 9 March 1916, aged 26, while serving in the Ypres Salient as a Lieutenant in the 7th (Service) Battalion, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. Lewin is buried in Bard Cottage Cemetery, Grave I.F.12. After the war, Russell, the Station’s Director, decided that his two colleagues should be properly commemorated, and commissioned a bronze memorial plaque from the artist and sculptor William Reynolds-Stephens (1862–1943) that was completed in 1920 and is displayed in the stairwell of the Research Station’s administration building. In a letter of 5 May 1920 to the Classical Philologist Professor Albert Curtis Clark (1859–1937), a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, Russell said that he wanted as its inscription a sentence from the Roman Catholic Breviary for the Epiphany or Lent “They saw their duty and they did it” and he asked Clark if he could provide a Latin translation of not more than 20 letters. Clark suggested “Quod agendum erat viderunt et fecerunt”, but this was too long. The final version reads, tersely: “Quod agendum fecerunt” (“They did what had to be done”) and involves an unintentional hint of bitter irony, since human choice and duty are now absent and the nature of “what had to be done” is left impersonal, undefined and ambivalent. He left £11,361 4s 3d and his widow sold the family home in March 1916.

After the War, Robert William Theodore Gunther (see above), who knew Martin well, commented:

In that most wasteful of all wars, there was no graver instance of Waste than that of the best brains of the best School [Zoology] in the University, for within that School from among men of a particular type, of proved and exceptional ability, the casualty list was well over 50 per cent! Similar cases of the squandering of the most precious assets of the country were considered by the Conference of Headmasters who, on December 23, 1915, passed a resolution, “That very grave loss to the country is caused by the employment of young students of exceptional mathematical ability as subalterns in Line battalions.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Notes’, Nature, 95, no. 2,376 (13 May 1915), p. 298.

One who knew him, ‘The Late Lieut. C.H.G. Martin’ [obituary], Abergavenny Chronicle, 79 (14 May 1915), unpaginated.

[Thomas] H[erbert] W[arren] and R[obert] T. G[unther], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 19 (14 May 1915), pp. 305–6.

F. Keeble, ‘Obituary: C. Martin’, Gardeners’ Chronicle, 57, no. 3,881 (15 May 1915), p. 270.

[Anon.], In memoriam: Charles Herbert George Martin (n.p., n.p., 1915) [contains the three obituaries listed above].

[Anon.], ‘Charles Herbert George Martin’ [obituary], The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,530 (4 June 1915), p. 822.

John Buchan, ‘A Soldier’s Battle: The Second Fight for Ypres: April 22–May 13’, The Times, no. 40,905 (13 July 1915), p. 7.

E.J. Russell, ‘Charles Martin’ [obituary], Biochemical Journal, 10, no. 1 (March 1916), pp. 9–10.

Günther (1924), pp. 435–6.

[Anon.], On the Western Front: 1/3rd Batt. Monmouthshire Regiment (Abergavenny: Seargeant Bros. Ltd. 1926), pp.18–60 [contains a photo of Martin in a group] p. 9, col. E.

John A. Owen, The History of the Dowlais Iron Works 1759–1910 (Newport, Mon.: Starling Press, 1977), pp. 81–91.

Anthony Summers and Stephen Dorril, Honeytrap (Sevenoaks: Coronet Books [Hodder & Stoughton Paperbacks], 1987), pp. 44–50, 168, 278, 290.

E. Jones, A History of GKN, 2 vols, vol. 1 (1759–1918), vol. 2 (1918–45) (London: Macmillan, 1987–90).

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Charles Edward Capel Martin’, Motor Sport, 74, no. 4 (April 1998), p. 100.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), p. 316.

B. Llewellyn James, ‘George Thomas Clark (1809–1898)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 11 (2004), pp. 803–06 (esp. p. 804).

John Williams, ‘Menelaus, William (1818–1882)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 37 (2004), pp. 809–10.

W.T. Morgan, ‘James, Charles Herbert (1817–1890), Dictionary of Welsh Biography: https://biography.wales/article/s-JAME-HER-1817 (accessed 29 January 2020).

Sir Brooks Richards, Secret Flotillas (2 vols) (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2012–13), i (Clandestine Sea Operations to Brittany 1940–44), pp. 119–20, 144–5, 150, 179, 316.

Archival sources:

ADM 1/14598.

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PR/2/15 and PR/2/16.

OUA: UR 2/1/42.

The Archive of Rothamsted Research, Hertfordshire.

WO95/2274 [contains the typescript of chapter III of On the Western Front (‘Second Battle of Ypres – April May 1915’)].

WO374/46371.

On-line sources:

Osmond Family Organization, ‘Martin Family’: https://sites.google.com/view/osmond-family-organization/histories/martin-family (accessed 29 January 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Steam Gun Boat’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steam_Gun_Boat (accessed 17 January 2020).

Walter Thomas Morgan, ‘James, Charles Herbert (1817–1890), M.P.’, Dictionary of Welsh Biography: https://biography.wales/article/s-JAME-HER-1817 (accessed 17 January 2020).

Scientific articles by Charles Martin:

‘Notes on some Oligochaets found on the Scottish Loch Survey’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Series B, 28, part I (October 1907), pp. 21–7.

‘Notes on some Turbellaria from Scottish Lochs’, ibid., pp. 28–34.

‘The Nematocysts of Turbellaria’, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science [QJMS], series 2, 52, part 2 (March 1908), pp. 261–77.

‘Weldonia parayguayensis. A doubtful form from the fresh water of Paraguay’, Zoologischer Anzeiger (Leipzig) [ZA], 32, no. 25 (14 April 1908), pp. 758–63.

‘Some Observations on Acinetaria: Part I: The “Tinctin-körper” of Acinetaria and the Conjugation of Acinetaria papillifera’, QJMS, 53, part 2, no. 210 (January 1909), pp. 351–77; ‘Part II: The Life-Cycle of Tachyblaston ephelotensis (Gen. et spec. nov.), with a possible identification of Acinetopsis rara, Robin’, ibid., pp. 378–90; ‘Part III: The Dimorphism of Ophryodendron’, ibid., 53, part 3, no. 211 (May 1909), pp. 629–64.

[With M(uriel) Robertson], ‘Preliminary Note on Trypanosoma eberthi (Kent) (= Spirochaeta eberthi, Luhe) and Some Other Parasitic Forms from the Intestine of the Fowl’, Proceedings of the Royal Society (London), Series B, Vol. B81, no. 549 (9 October 1909), pp. 385–91.

[With R. Elmhirst (The Superintendent of the Marine Station at Millport)], ‘On a Trypanoplasma from the stomach of the conger eel (Conger niger.)’, ZA, 35, no. 14/15 (15 February 1910), pp. 475–7.

‘Observations on Trypanoplasma congeri: Part I: The Division of the Active Form’, QJMS, 55, part 3 no. 219 (September 1910), pp. 485–96 [no further parts appeared].

[With M(uriel) Robertson], ‘Further Observations on the Caecal Parasites of Fowls, with Some Reference to the Rectal Fauna of other Vertebrates’, ibid., 57, part 1, no. 225 (August 1911), pp. 53–81.

[With (Major) W. G(len) M. Liston, I.M.S.], ‘Contributions to the Study of Pathogenic Amoebae from Bombay’, ibid., 57, part 2, no. 226 (November 1911), pp. 107–28.

‘A Note on the Early Stages of Nuclear Division of the Large Amoeba from Liver- abscesses’, ibid., pp. 279–81.

‘A Note on the Protozoa from Sick Soils, with Some Account of the Life-Cycle of a Flagellate Monad’, Proceedings of the Royal Society (London), Series B, Vol. B85, no. 580 (20 August 1912), pp. 393–400.

‘Some remarks on the behaviour of the kinetonucleus in the division of Flagellates: With a Note on Prowazekia terricola, a new Flagellate from Sick Soil’, ZA, 41, no. 10 (14 March 1913), pp. 452–6.

[Letter of 19 March 1913 from The Hill, Abergavenny], ‘The Presence of Protozoa in Soils’, Nature, 91, no. 2,266 (3 April 1913), p. 111.

‘Further Observations on the Intestinal Trypanoplasmas of Fishes, with a Note on the Division of Trypanoplasma cyprini in the Crop of a Leech’, QJMS, 59, part 1, no. 233 (May 1913), pp. 175–195.

[Letter of 27 January 1914, jointly signed with K(enneth) R(obert) Lewin from Lawes Experimental Laboratory, Rothamsted], ‘Soil Protozoa’, Nature, 92, no. 2310 (5 February 1914), p. 632.

‘A Note on the Occurrence of Nematocysts and Similar Structures in the Various Groups of the Animal Kingdom’, Biologisches Centralblatt (Leipzig), 34, no. 4 (20 April 1914), pp. 248–73 (with 8 text figs).

[With K(enneth) R(obert) Lewin], ‘Some Notes on Soil-Protozoa’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London), Series B, 205, [no issue number], (November 1914), pp. 77–94.