Fact file:

Matriculated: 1907

Born: 10 January 1889

Died: 4 September 1914

Regiment : Royal Horse Guards

Grave/Memorial: Baron Communal Cemetery

Family background

b. 10 January 1889 at Clayton Hall, Staffordshire, as the only son of Sir James Heath, JP DL MP (1852–1942), 1st (and only) Baronet Heath (1904), and his first wife Lady Euphemia Celina Heath (née Van der Byl, c.1861–1921, born in Cape Town, South Africa) (m. 1881). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was still living at Clayton Hall (housekeeper and three servants), but by the time of the 1901 Census it had moved to Ashorne Hill, Newbold Pacey, Warwickshire (14 live-in servants and several coachmen, grooms and gardeners scattered around the estate). The family was still living there at the time of the 1911 Census, but in 1914 it moved to Oxenden Hall, Market Harborough, Leicestershire. Also 34, Wilton Crescent, London SW; and 5, Hans Place (just behind Harrods), London SW.

Voltelin was a family name on Heath’s mother’s side.

Parents and antecedents

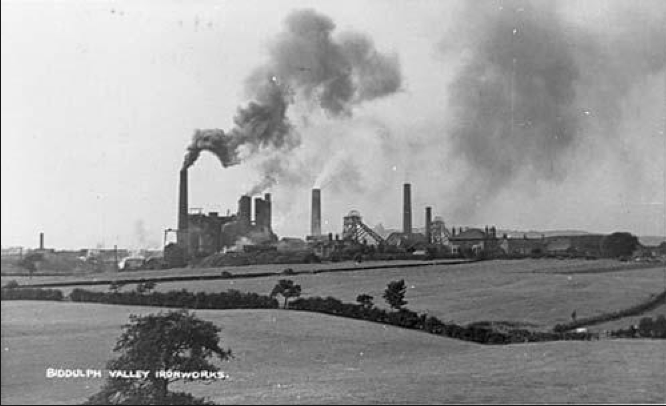

The Heath family is a large one and has been living in the Burslem area of Staffordshire since 1468 at least. It numbers several men who were successful potters by the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century – for example: Thomas Heath (1779–1839) was a well-known master-potter who lived at The Hadderidge, Burslem, where he manufactured earthenware, and Joseph Heath (c.1793–1874) was also a master-potter who became a manufacturer of some repute in High Street, Tunstall (one of the six towns that federated in 1910 to form Stoke-on-Trent). Heaths are buried in the churchyard at Hanley (another of the six towns), and the Heath family there, who flourished in the first half of the eighteenth century, owned mining property in Cobridge, three miles north of the centre of Stoke-on-Trent. But Sir James Heath’s family descends from that part of the family who lived in Caverswall and Carmountside, two Staffordshire villages to the east-south-east and north-east of Stoke-on-Trent respectively, and includes a good number of master-potters who became successful in the Burslem area in the second half of the eighteenth century. Heath’s great-great-grandfather, William Heath (c.1735–1802), came from Caverswall, and Heath’s great-grandfather, Robert Heath [I] (1779–1849), William’s fourth and youngest son, lived at Sneyd, near Burslem, and Kidsgrove. Heath’s grandfather, Robert Heath [II], DL JP CC (1816–93), the member of the family who succeeded in “gentrifying” it, was Robert [I]’s only son, and he married a co-heiress by whom he had three daughters and five sons (the second of whom was Heath’s father, James). He became an ironmaster, and established blast furnaces and the pits to keep them supplied with coal – first in the Biddulph Valley (with its own branch line in 1859), and then, in c.1863, at Ford Green (Norton Colliery), just to the south. By doing so, he became one of Staffordshire’s biggest employers, whose works gained widespread recognition for the quality of their iron. (These eventually collapsed as a business in 1928, after becoming Heath and Low Moor Ltd after an amalgamation c.1919.) Moreover, by the time of his death in 1893 Robert [II] had expended more than £300,000 in the purchase of Knypersley Hall, Clough Hall, and, in 1871, Biddulph Grange, a total of 8,000 acres or more.

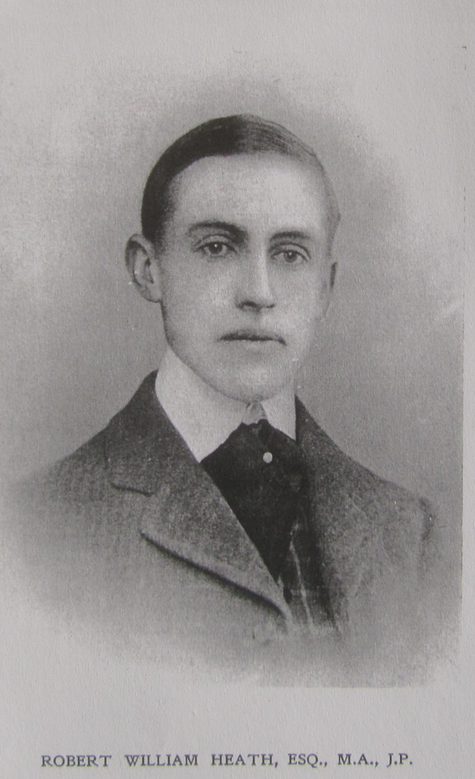

Percy Voltelin Heath’s cousin Robert William Heath, MA JP (1876–1954): the family likeness is striking (Robert William was the eldest son of Robert [III], who was the elder brother of Percy Voltelin’s father). (Photo c.1900)

In 1888 Robert [II] bought Clough Hall and sold it in 1889 to a consortium of Manchester businessmen who attempted to turn the estate into a huge pleasure centre for local people; but the scheme failed and the consortium was declared bankrupt in 1894. Robert [II] bought Biddulph Grange from James Bateman (1811–97), a horticulturist and landowner who had moved there in 1840 from Knypersley Hall with his father John Bateman (1782–1858) and had developed the property, especially its gardens, which became well-known for their splendour. Robert [II] was Conservative MP for Stoke-on-Trent from 1874 to 1880 and in 1884 High Sheriff of Staffordshire. He left £320,045, and his eldest son, Robert [III] (1851–1932), immediately inherited Biddulph Grange, but in 1896 a large part of it burnt down and had to be rebuilt, and from 1923 to 1991 it became a hospital. By the time the National Trust acquired it in 1991, its magnificent gardens had totally decayed; but over the next 25 years they were restored to their former glory.

In 1873, Heath’s father, James, who had been educated at Clifton College, became a partner in his father’s company aged 21, and while doing business on the firm’s behalf travelled twice round the world. On the death of Robert [II] in 1893, James and his brother Arthur (1856–1930), Robert [II]’s third son, changed the company’s name from Robert Heath & Co. to Robert Heath & Sons. They also acquired a huge industrial site at Birchenwood, near Kidsgrove, and set up Birchenwood Colliery in order to produce coke and coking by-products.

James Heath served as the Unionist MP for North-west Staffordshire from 1892 to 1906 and as an officer in the North Staffordshire Yeomanry (Queen’s Own Royal Regiment) for 29 years, eventually becoming the Regiment’s Colonel-in-Chief. In 1899, during the Second Boer War (1898–1902), he raised and commanded 300–400 Imperial Yeomen (members of a volunteer unit of fast-moving mounted infantry that was sent to South Africa in January 1900 to counter a series of defeats in the previous year by the mobile Boers).

Arthur Heath was also educated at Clifton College and went on to attend Brasenose College, Oxford, from 1875 to 1879. While an undergraduate, he got a double Blue – rugby union and cricket – and played rugby against Cambridge on four occasions. After leaving Oxford, he became even more well-known as a first-class cricketer – mainly at the county level. Besides being a successful businessman and industrialist, he was active in the Territorial Forces. In 1880 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the same Yeomanry Regiment as his brother James, and served with the Regiment for 30 years; like James, too, he became its Colonel-in-Chief (1906–10). From 1900 to 1906 he sat as the Unionist MP for Hanley, Staffordshire, and from January until December 1910 as the Unionist MP for Leek, also in Staffordshire. Although he retired from the Yeomanry in 1910, during World War One he served in a Howitzer Brigade of the Territorial Forces until 1915 and is referred to in his nephew’s obituary of 19 September 1914 as “Colonel”. His will gives his address as Keele Hall, the building that became the centre of the University College of Staffordshire in 1948 (University of Keele in 1962).

After the death of his first wife, Sir James Heath married three more times: (ii) (1924), Mrs Joy Nitch Smith (née Ivy Amelia Hounsell) (1893–1977), a divorcee and American citizen, marriage annulled in 1924 (USA) and 1927 (Britain); (iii) (1927) Sophie Catherine Theresa Mary Peirce-Evans (1896–1938), marriage annulled in 1930 (USA) and 1932 (Britain); during the 1920s and 1930s she was a world-famous pilot who was known as “the Irish Aviatrix” and had many firsts to her name, such as the first solo flight by a woman from South Africa to London; (iv) (1935) Dorothy Mary Hodgson, B.Sc. (1899–1981), who was the daughter of a retired official in the Indian Forestry Service and became the penultimate Mayor of the Borough of Chelsea (1963–64) before its amalgamation with the Borough of Kensington. Having served on Chelsea Borough Council since 1949, she was elected Alderman of the Borough of Chelsea in January 1965 in recognition of her public service.

Siblings and their families

Percy Voltelin’s sister was Hylda Madeleine (1881–1960), later James after her marriage in 1907 to [i] Captain George Millais James (1880–1914), who was killed in action by a sniper, aged 34, on 3 November 1914 near Zillebeke, south-east ofat Ypres, while serving as Brigade Major in the 22nd Infantry Brigade, 7th Division (no known grave); two daughters. She then became Hylda Bates after her marriage (1918) to [ii] Major Cecil Robert Bates (1882–1935); one son, one daughter.

Education

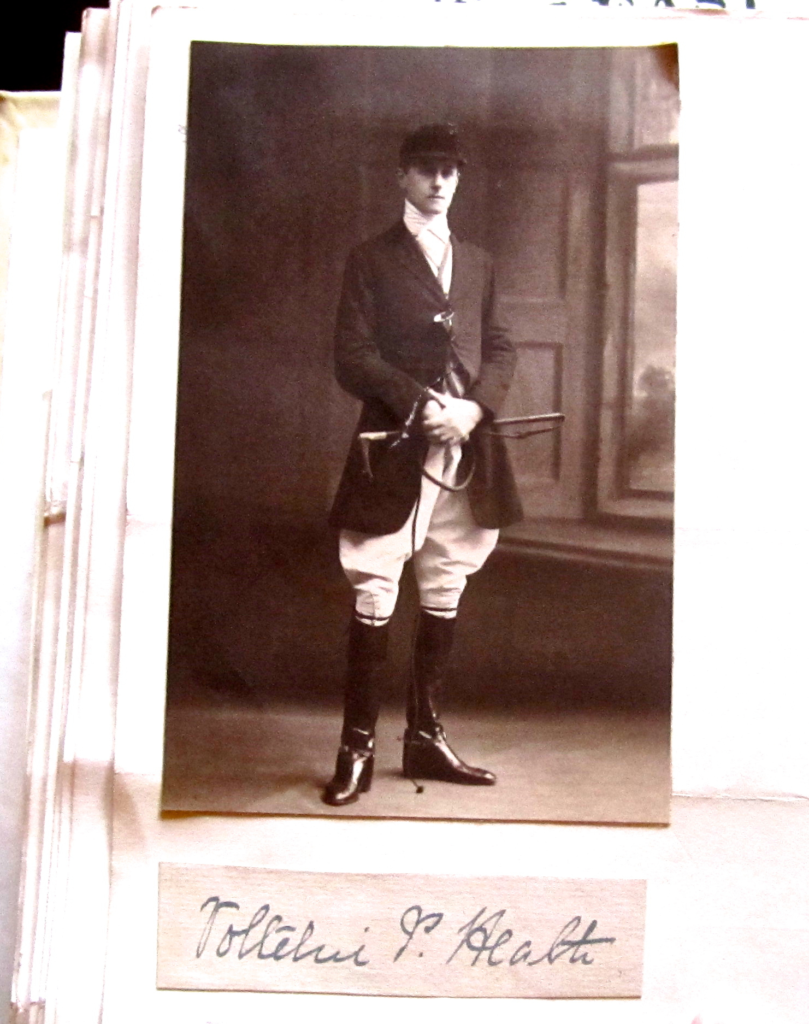

Clearly, Heath’s family had resolved that their son was going to be gentrified and moved out of the class of successful businessmen into which he had been born. He attended Mr Dunn’s Preparatory School, Ludgrove, Cockfosters, New Barnet, Hertfordshire, from c.1893 to 1898 (cf. N.G. Chamberlain). The school, which became Ludgrove School when it moved to Wixenford, Wokingham, Berkshire, in 1937, was founded in 1892 by the noted footballer Arthur Dunn (1860–1902). Then, after attending Eton College from 1902 to 1907, Heath matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1907, having passed Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1906. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1908, and in Trinity Term 1911 he was awarded a 2nd in Modern History (Honours). He took his BA on 11 November 1911 alongside T.E. Lawrence (the future Lawrence of Arabia, who was a Senior Demy [Research Student] at Magdalen for a year) and Stephen Grosvenor [“Luggins”] Lee (1889–1962; Fellow and Tutor in History at Magdalen 1920–47). And according to his obituary in the Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel, he had “a brilliant career” at Oxford, for besides getting a good second(-class) degree in the History School – “just missed a first” – “he read papers at the meetings of the literature and political clubs”; “was a leader of the sporting section of the University, being the President of the Bullingdon Club, Master of the [University] Drag [Hounds – a pack maintained by Magdalen and New Colleges], and Captain of the [University] Polo Team.”

Percy Voltelin Heath, BA, dressed as Master of the University Drag Hounds

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Military and war service

Heath was commissioned (probationary) Second Lieutenant on the Unattached List on 25 June 1908, i.e. after his first year at Oxford, and joined the Royal Horse Guards (“The Blues”) as a University candidate in July 1911, soon after leaving Oxford. He was confirmed in the rank of Second Lieutenant on 21 October 1911 and promoted Lieutenant on 13 April 1912. It cost an individual c.£600 p.a. to be an officer in such a socially exclusive Regiment and Heath, for whom such a sum would not have posed a problem, played polo for the Horse Guards and moved in fashionable Court circles: he was a member of the Marlborough and Bachelors’ Clubs, also the Hurlingham (an exclusive riverside sports club in Fulham frequented by the British social elites) and the Ranelagh (sailing). An obituarist tells us that he was “not a little interested in politics” and would probably have followed his father into the House of Commons.

Percy Voltelin Heath, BA. The photo first appeared in The Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel, no. 3,158 (19 September 1914), p. 8.

“The more I see of this war the more I feel it is a struggle between freedom, affection, culture, in fact between civilization on the one hand and iron discipline, stern mathematics and deep calculated greed on the other. The stories of German cruelties are not a bit exaggerated! and these are the more wicked in that they are done in cold blood and as part of a system – – I got some papers here last night – The war seems to be having a wonderful effect on the Country. After a struggle like this, neither public nor private thought can ever quite drop back to the old stupid point of view of the past.”

On the outbreak of war, when Heath was a serving officer, the Household Cavalry Composite Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin Berkeley Cook (1869–1914, who died in hospital of wounds received in action on 4 November 1914) was formed by taking one Squadron each from the depleted 1st Life Guards, 2nd Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards. It was then assigned to the 4th Cavalry Brigade in the (1st) Cavalry Division that was commanded by Major-General (later Field-Marshal) Allenby (1861–1936, later Viscount Allenby of Megiddo and Folkestone). Heath was among those seconded to the Regiment, which left Hyde Park Barracks for Southampton on 15 August 1914 and disembarked at Le Havre the following day to join up with the rest of the Brigade (which had been arriving in France between 15 and 18 August). It then travelled by train to Hautmont in northern France, 14½ miles south of Mons (just over the border in Belgium), but stayed at Dimont, eight miles to the south-east, until 21 August, when it crossed into Belgium to help stem the German advance through Belgium towards France. The Regiment first saw action when it was in support of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade at Halte, near Mons, on 22 August and reached Saultain (c.20 miles to the south-west of Mons) on 23 August, where it resisted a strong attack by German infantry until it was ordered to retire. It then went to the assistance of the 4th Division, commanded by Major-General Thomas D’Oyly Snow (1858–1940), whose mounted and support troops were still en route to France from Britain, to hold the line in the area of Cambrai from 23 to 25 August and at the Battle of Le Cateau-Cambrésis on 26 August, thereby covering the British Expeditionary Force’s retreat from Mons south-south-westwards in the direction of Paris (see G.M.R. Turbutt, E.D.F. Kelly). During the night of 26–27 August the Composite Cavalry Regiment acted as the rearguard for Snow’s incomplete Division, and on the following day it took part in a stiff rearguard action at Vendhuile, 19 miles west-south-west of Le Cateau-Cambrésis and on the left of the British line. The Regiment then continued its withdrawal for a further four days, with a minor skirmish with the enemy on 29 August, and finally reached Compiègne, a march of c.50 miles, on 31 August, where it fought a rearguard action to cover the retreat of the 3rd (King’s Own) Hussars, who were under attack.

On 31 August Heath, who had taken three horses with him to France, wrote a letter to his mother in which he described his recent experiences as follows:

Here we are at Compiègne, only about 40 miles from Paris. The ten days of retreat have been most exhausting both for horses and men. – We – the Cavalry had to cover the Infantry after that hammering they had near Mons – so for ten days we have fought & retreated & manoeuvred. We have often had to move off in the middle of the night & three times have actually marched all through the night – We have been fortunate in suffering very few losses. The more I see of this war the more I feel it is a struggle between freedom, affection, culture, in fact between civilization on the one hand and iron discipline, stern mathematics & deep calculated greed on the other. The stories of German cruelties are not a bit exag[g]erated! and these are the more wicked in that they are done in cold blood & as part of a system – – I got some papers here last night – The war seems to be having a wonderful effect on the Country. After a struggle like this, neither public nor private thought can ever quite drop back to the old stupid point of view of the past. So glad Hylda & Georgie are coming back for good – He will be delighted to get out here & it will be nice for you having them at Oxendon.

Farm in Néry occupied by C Squadron, 11th Hussars, on 1 September 1914

(http://www.britishbattles.com/firstww/battle-of-nery.htm)

But at 05.30 hours on 1 September, news reached the 4th Cavalry Brigade that the 1st Cavalry Brigade – which included the 11th (Prince Albert’s Own) Hussars – and ‘L’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, had been attacked through thick fog by a vastly superior force of German cavalry at the village of Néry, 12 miles south of Compiègne. So Heath’s 4th Cavalry Brigade at once advanced to take up a blocking position on Mont Courmont, the highest piece of ground in the area, one and a half miles to the south of Néry. A Squadron of the 2nd Life Guards and Heath’s troop from the Royal Horse Guards were then sent forwards to reconnoitre the village, and when they saw some dismounted enemy soldiers near the sugar factory on its southernmost edge, they charged forwards, causing the Germans rapidly to retire – whereupon Heath dismounted his men and opened fire. But the Germans soon counter-attacked Heath’s small force, and as it retired, Heath’s troop lost several horses and five men wounded and he himself was hit in the foot and the thigh by a bullet which broke the bone. When some of his troopers tried to get Heath back on his horse, he was hit in the head and had to be left where he had fallen. After the Germans had been beaten off, a doctor managed to reach him and found him conscious but dangerously wounded. At first, it was hoped that he would survive, but he died of his wounds, aged 25, on 4 September 1914 at the hospital in the Château Baron, to the south-east of Néry. He was buried in Baron Communal Cemetery; the inscription reads “Son of Sir James & Lady Heath of Oxenden Hall Market Harboro”.

Percy Voltelin Heath’s grave in Baron Communal Cemetery. The Cemetery is so small that the 16 British military graves, all from September 1914, have been jammed together, side by side and one on top of the other. This makes some of them very difficult to photograph well.

By the time that the fighting at Néry ceased at around 08.45 hours on 2 September 1914, three members of ‘L’ Battery had been awarded the Victoria Cross and the British had succeeded in pushing back the advancing Germans – but at a heavy cost, having lost around 135 men killed, wounded and missing and 380 horses.

Heath’s obituary in the Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel said:

He gave up what might have been a great career in any sphere of life to help to put an end to the brutal system against which we are at war, and his example had a good effect in North Staffordshire. It undoubtedly stimulated recruiting, and his death has placed the fighting spirit amongst the Biddulph [Hunt] even higher than ever. […] The death of Lieutenant Heath is mourned by the whole community, the grief that is felt being only relieved by the knowledge that the gallant, able and popular young officer died in an heroic and glorious death in the service of his country.

The diarist and Fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb, who recorded Heath’s death in his Diary on 16 September 1914, was less enthusiastic and simply remarked: “Voltelin Heath died of his wounds nr Paris: a cleverish, conceited boy but no doubt a gallant one. R.I.P.” Heath left £580. The remnants of the Household Composite Cavalry Regiment were disbanded on 11 November 1914 and merged with the equally battered 7th Cavalry Brigade (see Kelly).

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Robert Heath, Esq., J.P., D.L.’, in: Staffordshire and some Neighbouring Records: Historical, Biographical & Pictorial (London: Allan North, [n.d. but before 1914]), pp. 263–4.

George Rickwood and William Gaskell (eds), ‘Robert William Heath, Esq., M.A., J.P. Staffordshire Leaders: Social and Political ([Leyton] London: The Era Press [1907]), pp. 156–8.

[Anon.], ‘The Opening Meet of the University Drag Hounds at Woodstock on Monday, October 13th [1913]’, The Isis, no. 513 (18 October 1913), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘New College & Magdalen Beagles’, The Isis, no. 514 (25 October 1913), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘Sir James Heath’s Son: Killed in Action’, The Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel, no. 3,158 (19 September 1914), p. 8.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 33, no. 1 (16 October 1914), p. 11.

Clutterbuck, i (1915), p. 180.

Bell (1922), pp. 64–7.

[Anon.], ‘Colonel A.H. Heath’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,497 (26 April 1930), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Col. A.H. Heath: Member of Well-known Staffordshire Family’, Staffordshire Advertiser, no issue no. (26 April 1930), p. 9.

Cook (n.d.).

Percy W.L. Adams, ‘Notes on the Heath Family of North Staffordshire’, in: Notes on some North Staffordshire Families (Tunstall: Edwin H. Eardley, [1931]), pp. 86–92.

[Anon.], ‘Ex-Mate of Lady Heath takes 4th Wife at Age of 83’, Chicago Herald Tribune, 94, no. 30 (7 February 1935), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Sir James Heath’ [obituary], The Times, no. 49,430 (30 December 1942), p. 6.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 144, 153–4, 192, 203, 326.

Anne Ferris, Biddulph Grange (Stoke-on-Trent: Sherwin Rivers Ltd, 1985).

F.M.L. Thompson, Gentrification and the Enterprise Culture: Britain 1780–1980 (Oxford: OUP, 2001), pp. 59, 122–42.

Derek J. Wheelhouse, Biddulph, vol. 2 (Stroud: Tempus, 2005).

Takle (2007), pp. 96–8, 105.

Beckett (2006), pp. 46–7, 171.

Becke ([2009]), pp. 324–-44.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/640–642 (President Warren’s Wartime Correspondence, Letters relating to P.V. Heath [1914]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

OUA: UR 2/1/63.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1112.

WO95/1135.

WO95/1660/1

WO95/1665.

WO339/8045.

On-line sources:

‘Arthur Heath’, Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Heath (accessed 10 October 2017).

‘Sir James Heath, 1st Baronet’, Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_James_Heath,_1st_Baronet (accessed 10 October 2017).