Fact file:

Matriculated: 1897

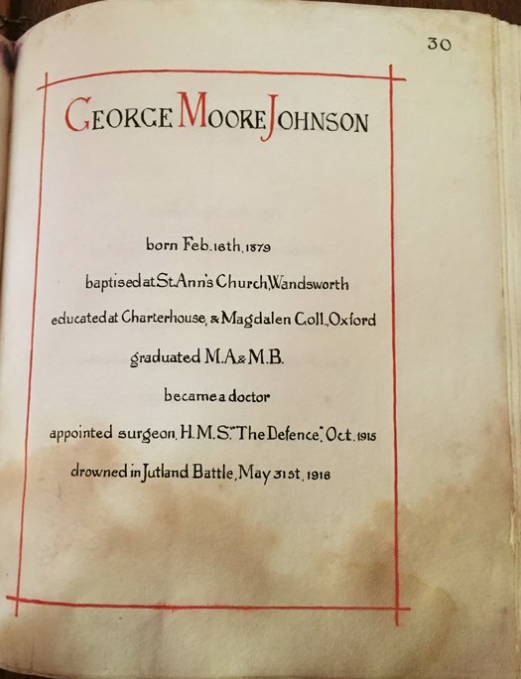

Born: 16 February 1879

Died: 31 May 1916

Regiment: Royal Navy, HMS Defence

Grave/Memorial: Plymouth Naval Memorial: Panel 10

Family background

b. 16 February 1879 in Wandsworth as the elder son of George William Moore Johnson (1851–1909) and Mary Elizabeth Johnson (née Rowell) (b. c.1850–1936) (m. 1878). At the time of the 1881 Census the family lived at 2 St Anne’s Hill, Wandsworth, with three servants, and according to the 1891 and 1901 Censuses they then lived at Moat Lodge, 31 The Avenue, Beckenham, Kent, with three servants. By the time of the 1911 Census the widowed Mary Elizabeth was living at “Woodville”, 27 Beckenham Grove, Shortlands, Kent, with two servants.

Parents and antecedents

According to Census records, Johnson’s father was a broker’s clerk in 1881, in banking in 1891, and a bank clerk in 1901, almost certainly working for Child’s Bank, Fleet Street, London. But in the London Gazette of 18 February 1907 he is listed as one of the partners of Child’s Bank together with Victor Albert George Child Villiers, 7th Earl of Jersey, GCB, GCMG, PC, JP, DL (1845–1915), and Frederick George Hilton Price (1842–1909) (antiquary), the two senior partners. Child’s Bank eventually became part of the Royal Bank of Scotland while retaining some degree of independence, and in 2018 it was still working from Fleet Street.

George Johnson was the son of the Reverend Arthur Johnson (c.1804–1867), a graduate of Christ Church, Oxford, a Lecturer at St Vedast’s, Foster Lane, and a schoolmaster. He was killed in a carriage accident on 6 May 1909. Arthur was the son of the Reverend William Moore Johnson, one-time curate of Henbury, Gloucestershire, and Chaplain to the Right Honourable Lord Hutchinson (1757–1832). William Moore, together with Thomas Exley (1774–1855), wrote the four-volume Imperial Encyclopaedia: or, A New Universal Dictionary, published by J. & J. Cundee in London in 1812.

Siblings

Johnson’s brother was Arthur Moore Johnson (1882–1952), a professional soldier who was an “exemplary” gentleman cadet at Sandhurst in 1901/02 and was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers (RDF), on 17 January 1902 (London Gazette, no. 27,398, 17 January 1902, p. 388). By this time the family must have been reasonably well off, for it was able to afford to pay the £150 tuition fee – well over a working man’s average yearly salary – that was required to send a cadet to Sandhurst for a year. During the Second Boer War, from April to May 1902, he served in operations in the Cape Colony, the Orange River Colony and the Transvaal, and was awarded the Queen’s Medal with four clasps. Between the end of the Second Boer War and the outbreak of World War One, the 1st Battalion, RDF, garrisoned various places throughout the British Empire. He was gazetted Lieutenant on 29 December 1906 (LG, no. 27,985, 11 January 1907, p. 257), and on 24 April 1912, while seconded to the Egyptian Army (November 1910–August 1912), he was gazetted Captain (LG, no. 28,606, 10 May 1912, p. 3,370).

In 1912, at Greystones, County Wicklow, he married Annie Mary (May) Hicks (1889–1971), the only daughter of the late Charles Phillip Giffen Hicks (b. 1845, d. 1896 in Bermuda), Captain RN; she was also the stepdaughter of Colonel Geoffrey Downing (b. 1865 in Ireland, d. 1897), who commanded the 1st Battalion of the RDF. In August 1914 the battalion was stationed at Fort St George in Madras, but was soon sent back to Britain, where it landed at Plymouth on 21 December 1914 and became part of the 86th Brigade in the 29th Division. On 16 March 1915, numbering about a thousand other ranks (ORs) and 26 officers (one of whom was Arthur Moore), it embarked at Avonmouth on the SS Ausonia (1909–18; torpedoed and sunk by gunfire by the U-55 on 30 May 1918 620 miles west of Fastnet with the loss of 44 lives), sailed for the eastern Mediterranean, and disembarked in Alexandria on 30 March, where it spent a week acclimatizing at nearby Mex Camp. On 7 April it re-embarked on the Ausonia for Mudros, the main port of the Greek island of Lemnos, where it disembarked on 10 April.

5th Battalion, the Connaught Rangers, disembarking from HMS Clacton at Mudros, before going to Gallipoli, 29 July 1915; three companies of the 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers would have landed on ‘V’ beach from these boats (IWM Q 55092)

On 25 April 1915, the 1st Battalion of the RDF took part in the disastrous British landing on Gallipoli’s ‘V’ beach, on Cape Helles, the south-western tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula, and much of what follows comes from the pen of an anonymous Company Commander of the 1st Battalion, the Royal Munster Fusiliers (RMF) – now identified as Captain (later Colonel, DSO) Guy Westland Geddes (1880–1955) of ‘X’ Company. Starting at about 04.30 hours, three of the four RDF companies, including Arthur Moore’s ‘Y’ company, were carried across to the Peninsula in perfect weather by the auxiliary screw minesweeper HMS Clacton (1904–16; torpedoed by the U-73 on 3 August 1916 off Chai Aghizi, in the Levant). But the fourth RDF company, ‘W’ company, together with members of three other regiments, making nearly 2,000 troops in all, were packed into the SS River Clyde (1905; broken up 1966). This vessel was a large steam collier which, at the suggestion of its temporary Captain, Commander (later Commodore) Edward Unwin RN (later VC) (1864–1950), had been turned into a “Trojan Horse”, i.e. an early version of a landing assault ship. It had two wide ports specially cut on either side of the hull, beneath which a wide gallery ran down to the bow, and from which fully laden soldiers could access two gangways that led to the beach across a bridge that was formed by a steam-powered hopper-barge pulling three lighters. ‘V’ beach is just to the east of ‘W’ beach but separated from it by a cliff (see A.M.F.W. Porter), and is now a peaceful stretch of fine sand 320 metres long and nine metres wide that is backed by a sandy escarpment about three metres high. It forms “a natural amphitheatre” that slopes gently upwards to a height of 100 feet and has the village of Sedd-el-Bahr just above it on the right-hand side. But General Otto Liman von Sanders (1855–1929), the head of the German Military Mission to the Ottoman Army and commander of the Ottoman Army on Gallipoli, had anticipated such an invasion, and ensured that the natural defences offered by ‘V’ beach were strengthened by two 15-feet-thick barbed wire entanglements. These were partly submerged and held in place by solid metal stakes that were riveted so firmly to plates sunk into the ground that the heavy guns of the Royal Navy had been unable to destroy them during the preliminary barrage, which lasted from 05.00 to 06.25 hours. Besides such natural and man-made defences, ‘V’ beach was overlooked on both sides by two ruined forts which provided excellent cover for machine-gun nests, of which the Turks had four to six on the cliffs that covered the beach (see H. Irvine).

When they were sufficiently near to ‘V’ beach and it was still dark, the c.700 men of Arthur Moore’s battalion who were on board the Clacton were transferred into six “tows”; each of these consisted of a steam pinnace pulling four vulnerable wooden cutters, and each cutter contained 40 men who, it was intended, would land 30 minutes before the 2,000 men on board the River Clyde. After the pinnaces had cast off their “tow”, the men in the cutters were required to row the last few hundred yards to the beach themselves (see Porter). But the Turks, who were more numerous, better armed, and better marksmen than the British commanders had assumed, held their fire until the invaders were 20 yards from the shore before opening fire and then concentrated their fire on the oarsmen. As a result, the cutters began to drift and were easy targets for the Turkish machine-gunners. So while many of the invading troops were killed or wounded while trapped in the cutters or when trying to wade ashore while weighed down with 60 pounds of equipment, others were drowned when their boats sank or because of the equipment, and others burned to death when their boats caught fire under the fusillade. It was estimated that of the first boatload of 40 men, only three reached the shore, and that of the first “tow” of 240 men, not more than 40 made it to the beach. Besides which, the tactical preparations for the landing were poor and Geddes later said that:

[although] we all knew our job and what was expected of us […] we felt we should have liked to have viewed in reality the scene of our landing beforehand. The maps issued were indifferent, and painted but a poor picture of the topographical features [–] as we found out later.

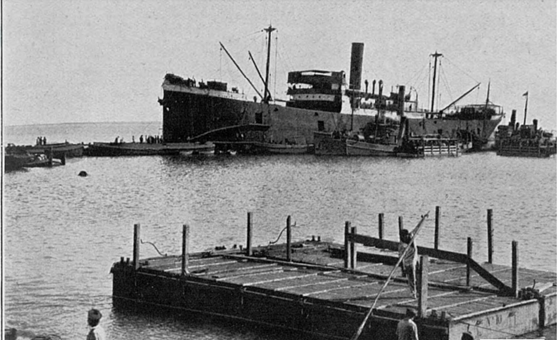

The beached River Clyde (1905; broken up 1966), with its pontoons on ‘V’ Beach, Gallipoli

(Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, no. 2,177, 5 June 1915, p. 9)

Some of the surviving cutters reached ‘V’ beach at about 06.25 hours and took cover on the port side of the River Clyde, which, having arrived there at about the same time, had been deliberately grounded near a stony pier under the cliffs on the right of the beach beneath the old fort at Sedd-el-Bahr. But the lateral current there was much faster than anticipated and the River Clyde was just too far from the shore for its two gangways to reach the shallows, let alone the shore itself. So with the 1st Battalion of the Munster Regiment in the lead, the heavily laden troops aboard the old collier were forced to struggle through deep water, causing more than a few of them to drown, and like the three Companies of the RDF in the cutters, these unfortunate men were exposed to another withering hail of Turkish small-arms and machine-gun fire and much heavier fire from two 37 mm Turkish pom-pom cannons – probably taken off a ship – that did a huge amount of damage very quickly. It was estimated that of the first 200 men who tried to reach the shore via the gangway outside the collier, 149 were killed outright and 30 were within minutes – “literally slaughtered like rats in a trap” as Captain Geddes put it. Aboard the collier, Captain Unwin RN clambered waist-deep into the strong current where, at great personal risk, he and some of his sailors began to improvise a bridge of lighters that would enable their passengers to get ashore more easily. But although almost 1,000 men had left the River Clyde by 11.00 hours, nearly half of them had been killed or wounded before reaching the far side of the beach, which, to cite Ford, had been turned into a “charnel house”, with the RDF alone losing 21 officers and 510 men killed, wounded and missing in the first 15 minutes and provoking one observer to comment that “the carnage on ‘V’ beach was chilling”.

The Commanding Officer of the RDF’s 1st Battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Alexander Rooth (1866–1915), was an early casualty and his second-in-command, Major Edwyn Fetherstonhaugh (1867–1915), was also killed. Another of those killed was the Battalion chaplain, Father William F. Finn (1875–1915), a Carmelite priest who was the first chaplain to be killed in the war. Lieutenant Robert Bernard (1891–1915), the son of John Henry Bernard (1860–1927; the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin from 1915 to 1919), took over the command of his company only to be killed while renewing the attack on the following day. Although the British succeeded in establishing a bridgehead over the next five days, the landings at Cape Hellas cost the RDF ten officers and 153 ORs killed, 13 officers and 329 ORs wounded and 21 ORs missing, leaving one officer and 374 ORs as survivors. Arthur Moore was one of the wounded and played no further part in the Gallipoli campaign; on 30 April 1915, the survivors of the 1st Battalion of the RDF and the 1st Battalion of the RMF amalgamated for a month or so as the “Dubsters”; not surprisingly, the RMF’s War Diary, which had ceased on 10 April 1915, when the 1st Battalion reached Lemnos, did not recommence until 19 July 1915. For a more detailed account of the landing on ‘V’ beach see the biography of Harold Irvine.

Officers of the 1st Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, in a photo taken immediately before sailing for Gallipoli; Johnson is 4th, Major Fetherstonhaugh 6th and Lt Col. Rooth 7th from the left in the front row; Father Finn is 7th from right in the second row

The 1st Battalion of the RDF was evacuated to Mudros on 1 January 1916 and from there to Egypt on 8 January 1916, but was soon moved to France, where it disembarked in Marseilles on 19 March 1916. It fought there and in Belgium for the rest of the war, and by the Armistice it had lost 4,780 of its members killed in action. Meanwhile, on 23 October 1916, Arthur Moore was gazetted Temporary Major in the Hertfordshire Regiment (Territorial Force) (London Gazette, no. 29,811, 31 October 1916, p. 10,631), even though he had been gazetted Major in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers on 18 January 1917 (LG, no. 29,946, 15 February 1917, p. 1,626). But on 9 May 1917 he relinquished his Territorial commission when he left the Hertfordshire Regiment (LG, no. 30,288, 17 September 1917, p. 9,641). With effect from 6 June 1922 he was placed on the half-pay list on account of ill health (LG, no. 32,692, 5 May 1922, p. 3,608), possibly due to his wounds from Gallipoli. In 1939, when he gave his occupation as retired Major in the Census, he was living with his wife in Torrington, Devon, where he died in 1952. He was cremated in Plymouth and is commemorated on the family grave in the St John the Evangelist churchyard, Shirley, Croydon, where his parents were buried. His wife, who was cremated in Loughborough, is also commemorated there. He left £11,288 2s. 11d.

Wife

Johnson arrived in Liverpool on 17 February 1915 on board the steam ship the SS Dominion (1898–1922; scrapped in Germany), which had sailed from Philadelphia as part of the America Line and stopped at St John’s, Newfoundland, where Johnson boarded her. As his destination he gave “Woodville”, Shortlands, Kent, his mother’s address, and he gave his occupation as physician. He was accompanied by his wife (“Mrs Johnson”, with no other name given) and she, like her husband, was 35 years old. We can find no evidence of his having married before he went to Newfoundland and so suppose he met and married his wife while there. His obituary in The Lancet offers sympathy to his wife, while a somewhat strange obituary in Günther’s History of the Daubeny Laboratory does not mention her, and even more strangely refers to him as George Montague Johnson; and yet Günther must have taught him. No reference to his wife appears in the records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which gives his mother’s name and incorrectly refers to his father as being MB, MA, thereby mixing him up with his son. The newspaper report below does refer to his wife, although she is once again unnamed.

“In his work he shewed much ability, and was always capable of dealing with any difficult situation. By his patients he was respected for his professional skill, and there were few who did not appreciate the sympathy which he extended, often accompanied by some expression of his peculiarly characteristic humour.”

Education and professional life

Johnson attended Arlington House Preparatory School, Brighton, Sussex, from 1888 to 1893 and then Charterhouse from 1893 to 1897. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 21 October 1897, having passed two parts of Responsions (Classical Literature and Mathematics) in Trinity Term 1897; he then passed the third part (Holy Scripture) in Michaelmas Term 1897. He passed the Preliminary Examination in Natural Science over a period of four terms (1899–1900), and was awarded a 4th in Physiology (Honours) in Trinity Term 1901. He took his BA on 17 October 1901. On 21 February 1917, his brother Arthur Moore wrote to President Warren that George’s four years at Magdalen “were some of the happiest years of his life, in spite of the fact that he was sent down for one term!”. Arthur’s opinion may have been due to his belief that his brother had neglected his studies for the sake of sport. Johnson was a natural athlete and, according to one of his obituarists, was “gifted with a superb body”. He had sampled rowing at Magdalen in Michaelmas Term 1897 and been selected to row in the 2nd Torpid VIII in the following term alongside such notable Magdalen College Boat Club contemporaries as A.P.D. Birchall, A.H. Huth, G.S. Maclagan, and C.P. Rowley. But he was not involved in competitive rowing after that, and the College’s cricket and football records have not survived. We do know, however, that he attended Natural Science lectures in the College’s Lecture Room, failed his first public exam in the Rudiments of Natural Science in October 1898, and managed only a gamma in the term exam on 12 December. That was a poor result after four terms, and it is likely that he was sent down for the Hilary Term 1899 to concentrate on his studies, because at the end of that term he gained an alpha in his term exam, and a beta in the same exam at the end of the following term. Magdalen’s President had the measure of his academic career: “Though not naturally endowed with the gift of readily answering examination questions, he obtained Honours in Physiology in 1901 and became a very sound medical man.”

After taking his BA, Johnson stayed for nearly three more years at Oxford working towards his first BM. He passed Organic Chemistry in June 1902, Materia Medica in December 1902, and Human Anatomy and Human Physiology in December 1903. He then, as was usual at the time, entered the London Hospital Medical College as “a composition student” on 1 March 1904 to do the clinical training for his second BM. He was a Clinical Clerk under Dr Isidore Schorstein (b.c.1844 in Paris, d. 1906) from March to April 1904, and a Dresser under Messrs Hutchinson and Barnard from May to July 1904. After attending 37 maternity cases, he worked as a Post Mortem Clerk under Dr F.J. Smith from November 1904 to January 1905 and as an out-patients Clinical Clerk under Dr Andrews from December 1904 to January 1905. He spent a second spell as a Dresser under Messrs Eve and Furnivall from February to April 1905 and as a Clinical Clerk under Dr Head from February to April 1905. All his mentors rated him “good” or “very good”. He then passed the second BM in Pathology in June/July 1905, in Forensic Medicine in 1906, and in Medicine, Surgery and Midwifery in April 1907. After some referrals, he passed the third BM for Medicine and Midwifery in December 1907 and was finally awarded the BM (Oxon.) and BCh on 23 January 1908.

Later that year he returned to Oxford, where he took his MA as House Physician and later House Surgeon at the Radcliffe Infirmary. He left Oxford some time in 1909 and went to Penzance, where he worked as a GP for some 18 months: he was still there at the time of the 1911 Census, renting a room at 7 Alverton Terrace, in a house belonging to one Herbert Wood, a retired butcher. His obituarist in The London Hospital Gazette, William Jenkins Oliver, who was a near contemporary of Johnson’s at the London Hospital and a friend from his time at the Radcliffe Infirmary, noted with some regret that after getting his medical qualifications, Johnson “did not appear to be able to settle down and to take up some definite line of work” and that he did not truly believe that “circumstances, coupled with his rather impatient temperament, allowed him to come to any decision”. This judgement is borne out by the fact that after leaving Penzance, Johnson worked in several general practices in different parts of the country and spent a brief period as Assistant Medical Officer to an asylum before going in January 1913 to Trinity, Newfoundland, a community of less than 200 inhabitants on Trinity Bay.

He practised in Newfoundland until he and his wife returned to England in January, arriving at Liverpool on 17 February. Oliver ventured the opinion that Johnson might have remained in Newfoundland if war had not broken out and that he “seemed to be more satisfied with his life and work under such surroundings than here at home in England”. Johnson’s obituarist in The Lancet implies that he probably preferred the outdoor life of remote northern Canada because he was “always fond of sport and good at all games, […] a good shot and a keen and successful fisherman and boatman; indeed in the course of his professional duties in Newfoundland he often went out in such weather that the fishermen would be anxiously awaiting his return”. When Johnson returned to England, he found that the authorities were slow in engaging extra medical assistance for the armed forces. So he spent the next nine months working under the Senior Officer of Public Health in Ipswich as assistant tuberculosis officer and school medical officer for East Suffolk.

In August 1915, Johnson and his wife were staying at Perranporth, on the north Cornish coast between Newquay and St Ives, and while they were there, on Saturday 28 August, Johnson was summoned before the West Powder Bench and charged with failing to obscure a light that was visible from the sea. As the report in the local paper, which appeared once a fortnight, is a wonderful period piece that combines stand-up music hall comedy with Toytown, here is a short extract from the long report. The witness, one PC Dingle,

stated that on Sunday night, the 15th inst., about 11 o’clock, he was on duty on the Western Cliffs, Perranporth, when he saw a light in a window at Rock View House. He went to the house and saw a light in the window. No blinds were down and the window was open. The house was situated on the beach, and the windows faced the sea. Witness called out: “I want to speak to the lady in that room”. Sir George [Smith – Chairman]: How did you know there was a lady in that room? Witness: I went there on the previous Friday and saw the lady.

After more high courtroom drama, it transpired that Mrs Johnson had, for a second time and after being cautioned, left a small candle burning while opening the dark blinds “which Mrs Robins, the proprietress of the house” had provided for the use of guests. Mrs Johnson had, the evidence indicated, kept the blinds down while undressing and was just getting into bed when the policeman called out. On hearing him, Mrs Johnson pulled down the blinds and extinguished the offending candle. The Chairman fined Johnson “£1 inclusive” as “the case was not […] affecting the defendant”.

War service

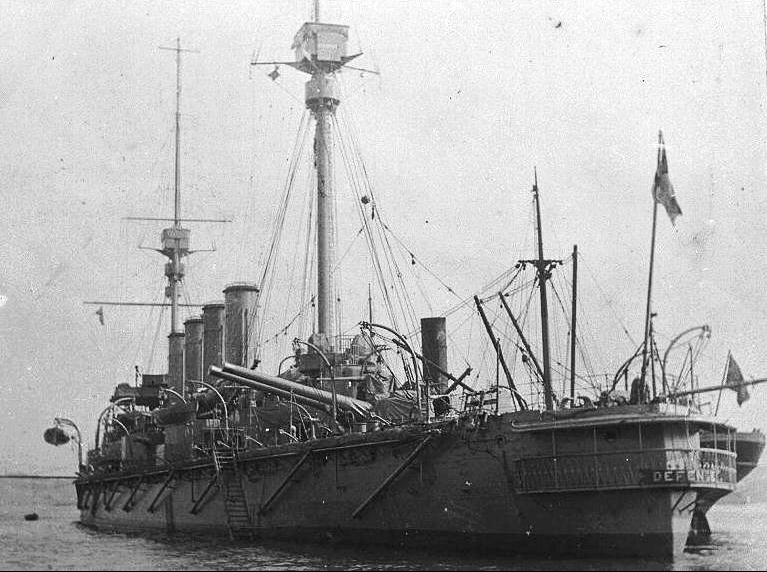

Not long afterwards, Johnson applied for a post as a surgeon in the Royal Navy, preferably aboard a big ship. On 28 September 1915 he was commissioned Temporary Surgeon Lieutenant RN, and on 29 October he was appointed to the armoured cruiser HMS Defence (1907–16), where he was one of three medical officers. The Defence had cost £1,362,970 and was the most modern of three four-funnelled Minotaur class armoured cruisers of 14,600 tons displacement – the other two being HMS Minotaur (1908–20; scrapped) and HMS Shannon (1908–20; scrapped). She was laid down in February 1905, launched in April 1907, and joined the 5th Cruiser Squadron in February 1909 before being transferred to the Home Fleet’s 1st Cruiser Squadron in July 1909. This squadron consisted of four ships – HMS Defence, HMS Warrior (1906–16; foundered and sank on 1 June 1916 as a result of battle damage), HMS Black Prince (1906–16; sunk with all hands on 1 June 1916), and HMS Duke of Edinburgh (1906–20; scrapped), the only member of the 1st Cruiser Squadron to survive the Battle of Jutland.

Although the Minotaurs were still relatively young ships in August 1914, by June 1916 they were, according to Andrew Gordon, “elegant antiques” and being replaced by battle cruisers. This new type of capital ship was the brainchild of Admiral Sir John Fisher (1841–1920), who wanted the Royal Navy to have some capital ships that had the armament of a conventional battleship but were lighter and faster, and so could be used more effectively for reconnaissance in the days before radar. The Germans also began to build battle cruisers during the years leading up to World War One, although, like all German capital ships, they were more lightly armed and slower than their British counterparts. They were, on the other hand, more heavily armoured, broader beamed (and therefore more stable as gun platforms), and with better water-tight sub-divisions – distinguishing features that would become of great importance during the Battle of Jutland. However, whether we are discussing Britain or Germany, the pace at which battle cruisers had been developed during the pre-war years meant that by August 1914, older armoured cruisers like the Defence were already obsolescent since they were coal-fired, had a maximum speed of 23 knots, and carried only four 9.2-inch guns in twin centre-line turrets and ten 7.5-inch guns in single barbettes – five on either side. In contrast, the more modern battle cruisers were oil-fired, had a maximum speed of 25 to 27.5 knots, and were equipped with 12- or 13.5-inch guns, mostly in centre-line turrets. Nicholas Jellicoe, the grandson of the British admiral, summarized the situation of the Minotaurs as follows: they were “the last of the pre-Invincibles [the first class of British battle-cruisers]”,“badly limited in armour and armament” and as such “the cruiser equivalents of pre-dreadnoughts”.

By the time that Johnson joined the Defence, she had, as part of the Royal Navy’s four-ship Mediterranean Cruiser Squadron, “played an unheroic role” as Rear-Admiral Sir Ernest Troubridge’s (1862–1926) flagship at the eastern end of the Mediterranean, where she was involved in the last phase of the Royal Navy’s abortive pursuit of the German battle cruiser SMS Goeben (1911; decommissioned from the Turkish Navy 1954; sold and broken up for scrap 1973–76) and the German light cruiser SMS Breslau (1911; sunk off the Island of Imbros on 20 January 1918 after hitting five mines during the Battle of Imbros). After being pursued across the Mediterranean between 28 July and 10 August 1914, these two ships were guided by a Turkish pilot through the Dardanelles to Constantinople, where, on 16 August, i.e. three months before the Ottoman Empire joined in the war on the side of Germany, they were transferred to the Ottoman Navy as the Yavuz and the Midilli respectively. It later transpired that the whole incident, ending as it did, had played a major part in Turkey’s decision to enter the war on the side of Germany, and in early November 1914, Troubridge was court-martialled for failing to engage the enemy. Although he was acquitted, he was relieved of his command and was never again given a seagoing command.

In the same month, the Defence was ordered to the South Atlantic and the Cape of Good Hope in order to take part in the hunt for the German Navy’s East Asia Squadron. Consisting of five ships and commanded by Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee (1861–1914), the German Squadron had, on 1 November 1914, inflicted the first defeat on a unit of the Royal Navy for a century by defeating the 4th Cruiser Squadron at the Battle of Coronel off the coast of Chile. But on 8 December 1914, during the Battle of the Falkland Islands and before the Defence could arrive on the scene, the German squadron was destroyed and von Spee and his two sons had perished. Later in December the Defence arrived back in British home waters as part of the 1st Cruiser Squadron and soon became part of the British Grand Fleet (formerly the Home Fleet). But on 29 July 1914, about a week before the outbreak of war, Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty from September 1911 to 21 May 1915, had dispatched the Grand Fleet from Portland to the anchorage at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands to the north of Scotland, where it arrived on the following day. And here, in January 1915, the Defence became the flagship of the pugnacious, controversial and rigidly spartan Rear-Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot (1864–1916; killed in action aboard the Defence on 31 May 1916), whom the historians Andrew Gordon and Robert Massie would respectively characterize as “a demanding, competitive disciplinarian”, and a “remorselessly efficient […] tyrant, bully and physical training fanatic”.

Britain depended on the Grand Fleet to prevent an invasion by Germany, and it consisted of 151 ships armed with 1,700 guns, whereas the German High Seas Fleet consisted of 99 ships armed with 900 guns. Moreover, the British fleet possessed 28 dreadnought-type battleships whereas Germany had only 16 (plus six pre-dreadnought battleships). So the British Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe (1859–1935), envisaged one decisive battle with the German High Seas Fleet that would guarantee British dominance of the North Sea. In contrast, although Admiral Reinhard Scheer (1863–1928), the commander of the German High Seas Fleet from January 1916 (when he took over from the terminally ill Vice-Admiral Hugo von Pohl (1855–1916)), wanted to break the British blockade of Germany and open up routes into the Atlantic by developing a more aggressive strategy, he understood that the German navy’s numerical inferiority put it at a considerable disadvantage. So he avoided a major confrontation with the Grand Fleet during the first six months of his command and engaged in several minor engagements with the Royal Navy in an attempt to weaken it piecemeal. But by early summer 1916 Scheer had become more confident, and he decided to attempt to lure a significant part of the Grand Fleet into the reach of his own battleships, destroy it, and so achieve a greater parity between the two fleets that would enable him to dispute the British command of the North Sea.

Before his promotion Scheer had commanded the squadron that contained the most modern German capital ships, and in order to implement his strategy he decided to use his 1st Battle Cruiser Scouting Group as bait. This unit consisted of five fast battle cruisers under the command of Vice-Admiral Franz von Hipper (1863–1932): (1) SMS Von der Tann (1910–19; scuttled at Scapa Flow, wreck raised 1930, broken up 1931–34); (2) SMS Moltke (1911–19; scuttled at Scapa Flow, wreck raised 1927, broken up 1927–29); (3) SMS Seydlitz (1913–19; wreck scuttled at Scapa Flow, raised 1928, scrapped 1930); (4) SMS Derfflinger (1913–19; scuttled at Scapa Flow, wreck raised in 1939, broken up 1946–48); and (5) SMS Lützow (1913–16; scuttled by torpedoes from a German submarine to prevent its capture by the British after it had been seriously damaged during the Battle of Jutland).

When it fought the Battle of Jutland, Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet consisted of his 28 dreadnoughts (including the four available super-dreadnoughts of the 5th Battle Squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral (Sir) Hugh Evan-Thomas (1862–1928; see below); eight armoured cruisers (including the 1st Cruiser Squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral Arbuthnot; see above); 26 light cruisers; over 70 destroyers; and the three modern battle cruisers of the 3rd Battle Cruiser Squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral (Sir) Horace Hood (1870–1916; killed in action aboard his flagship the Invincible on 31 May 1916). These three battle cruisers were: HMS Invincible (1909–16; sunk on 31 May 1916); HMS Indomitable (1908–20; sold for scrap 1921); and HMS Inflexible (1908–20; scrapped 1920).

But Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet also consisted of the semi-independent Battle Cruiser Force, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty (1871–1936). This comprised the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral (Sir) Osmond de Beauvoir Brock (1869–1947): (1) HMS Lion (1912–20; scrapped 1924); (2) HMS Princess Royal (1911–18; sold for scrap 1920); (3) HMS Queen Mary (1913–16; sunk on 31 May 1916); and (4) HMS Tiger (1913–31; sold for scrap 1932); the 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral (Sir) William Pakenham (1861–1933): (1) HMS New Zealand (1911–20; broken up for scrap 1922); and (2) HMS Indefatigable (1911–16; sunk on 31 May 1916); the four available super-dreadnoughts of Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron mentioned above, which, on 22 April 1916, had been ordered to join Beatty’s Force, and did so a month later, on 22 May 1916: (1) HMS Barham (1914–41; torpedoed by the U-331 off Sollum and Sidi Barrani in the Mediterranean on 25 November 1941); (2) HMS Valiant (1914–48; scrapped); (3) HMS Warspite (1913–47; wrecked on the Cornish coast when under tow and scrapped); (4) HMS Malaya (1916–48; scrapped); and (5) HMS Queen Elizabeth (1914–48; scrapped; the one member of the 5th Battle Squadron that did not take part in the Battle of Jutland because she was undergoing repairs). The Battle Cruiser Force also included 12 light cruisers, 28 destroyers, and one seaplane tender – the converted cross-Channel ferry HMS Engadine (1911–19; reconverted to the Philippine SS Corregidor, and sunk by a mine in Manila harbour during the night of 16/17 December 1941 with the loss of 900–1,200 lives, mainly civilians).

During the early months of the war cryptanalysts working in the Admiralty’s Room 40 had cracked the German naval code, and Jellicoe gained an early advantage over Scheer on 30 May 1916 when they learnt at around noon that the High Seas Fleet would set out northwards from its base at Wilhelmshaven at 03.00 hours on the following day. The information reached Jellicoe at Scapa Flow shortly after 17.45 hours on 30 May and at 22.30 hours Jellicoe’s ships set out from Scapa Flow to hunt down and engage in a decisive battle with the as yet unsuspecting High Seas Fleet, which was still at anchor in its home port of Wilhelmshaven, c.570 miles to the south-east on the Jade Bight on the North Sea coast. Meanwhile, at 21.10 hours, Beatty’s battle cruisers had set off from their base at Rosyth, in the Firth of Forth, c.300 miles south of Scapa Flow, followed by Evan-Thomas’s four super-dreadnoughts at 22.07 hours. Beatty’s entire force then headed north-east in order to rendezvous with Jellicoe’s ships at 14.00 hours on the following day at the eastern end of the Long Forties, an area of deep water that runs approximately from Aberdeen to the southern tip of Norway. Once there, the main task of Beatty’s force was to locate the German fleet and provide Jellicoe with continuous information about its course and speed. But as an integral part of Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet, Arbuthnot’s 1st Cruiser Squadron was also tasked with long-distance scouting, keeping enemy cruisers at bay, and beating off attacks by fast torpedo-boat destroyers. So on 31 May 1916 Arbuthnot positioned his Squadron 16 miles ahead and starboard of Jellicoe’s main battle fleet.

At 14.20 hours on 31 May, scouts from Beatty’s force reported the enemy ships to the south-east; at 15.22 hours, while steering in a south-westerly direction, Hipper’s Scouting Group sighted Beatty’s six battle cruisers over to the west; at 15.30 hours Beatty’s force identified Hipper’s battle cruisers; at 15.40 hours the two fleets were about ten miles apart and closing rapidly; and at 15.48 hours Hipper ordered his ships to open fire on Beatty’s battle cruisers, each of which was assigned as a target to one of his own ships, thereby beginning the “run to the south” which lasted until 16.54 hours.

With a 500-yard interval between each ship, Beatty’s two Battle Cruiser Squadrons formed a line, with the four super-dreadnoughts of the 5th Battle Squadron seven miles behind them. But for reasons that are still controversial, Beatty hesitated to give the order to open fire and it was not until 15.45 hours that the Captain of the Lion – the leading ship in the line and Beatty’s flagship – decided to do so independently. Then, at 15.54 hours, i.e. within the opening minutes of what quickly became a running battle, a shell from the Moltke hit the Tiger’s ‘Q’ turret, did a great deal of damage, and “almost brought the ship to a standstill”. At 15.55 hours the modern battle cruiser Queen Mary scored the first British hit on a German ship when she landed two shells on the Seydlitz, but at 15.58 hours the Princess Royal was hit twice by shells from the Derfflinger’s 12-inch guns, and at 15.59 hours, the Lützow wrecked the Lion’s ‘Q’ Turret with a critical hit that would have destroyed the ship had it not been for the bravery of the mortally wounded turret commander, Marine Major Francis Harvey (1873–1916). Although he had lost both legs, Harvey managed to crawl to the voice-pipe and order the turret’s magazines to be flooded, thereby saving the ship and several hundred lives, for which he was awarded a posthumous VC. At 16.02 hours, the Von der Tann scored several hits with her 11-inch shells on the Indefatigable, the last ship in the line, igniting the cordite charges that were ready for use by ‘A’ turret, and after an interval of about 30 seconds two huge explosions broke her in two, hurling her 12-inch guns into the air “just like matchsticks” (as a survivor later put it) and killing all but three of her complement of c.1,020 men. At 16.24, the Lützow damaged the Lion even more badly by hitting her three times in 30 seconds before shifting her fire to the Princess Royal.

Meanwhile, the five super-dreadnoughts of the 5th Battle Squadron continued to approach Beatty’s badly mauled fleet and between 16.08 and 16.10 hours opened fire on the rear of the German line with their 15-inch guns, badly damaging Von der Tann and Moltke. Then, at 16.25 hours, joint salvoes from the Derfflinger and the Seydlitz landed several 12-inch shells on the modern battle cruiser Queen Mary, which was “considered the best gunnery ship of the Royal Navy”, and caused a huge explosion forward, “followed by a much heavier explosion amidships” that split her in two. She began to list and a minute later rolled over and sank within 90 seconds, killing all but 20 of her complement of c.1,280 men. Nicholas Jellicoe tells us that archaeological research has now confirmed that the explosions aboard the Queen Mary, the Invincible, and the Indefatigable were almost certainly the “direct result of an obsession with gunnery speed”. The inflammable silk bags containing the British cordite – an unstable chemical that deteriorates with age – had been “brought up from the magazines and stacked in the passageways below the guns” so that they were ready for immediate use, and fireproof magazine doors were left open to speed up the delivery of ammunition: practices that were condoned in British ships.

Besides inflicting considerable damage on Beatty’s initially superior force, Hipper’s ships continued to steam southwards for one hour and six minutes in order to draw it into the path of the High Seas Fleet, which was heading northwards. Ironically, the German commanders had no idea that the Grand Fleet was at sea and neither Jellicoe nor Beatty was aware of the German fleet. But at 16.28 hours a lookout on the SMS König (1914–19; scuttled at Scapa Flow, where she still lies on the bottom of the bay), Scheer’s leading dreadnought, sighted an action to the north-north-west; at 16.35 hours lookouts on the light cruiser HMS Southampton (1912–26; sold for scrap 1926) spotted the advancing High Seas Fleet; at 16.38 hours this important news was signalled to Jellicoe; and at 16.40 hours, Beatty turned his force northwards in order to persuade the German admirals that he was fleeing from certain defeat by the German fleet. But his real aim was to entice Hipper’s battle cruisers and Scheer’s battleships towards the big guns of the British Grand Fleet, of whose presence at sea and proximity the German admirals were unaware until they had blundered into Jellicoe’s carefully laid trap. At 16.50 hours Beatty’s battle cruisers passed Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron steaming in the opposite direction (i.e. southwards), but Beatty failed to signal his turn to Evan-Thomas so that the 5th Battle Squadron continued to steer into danger and, by 16.55 hours was coming under heavy fire as the König and Scheer’s other battleships were able to concentrate their fire on each of its ships in turn. But by 17.00 hours all four of Evan-Thomas’s battleships had turned northwards, and over the next 30 minutes, despite the German shelling, they formed a protective screen for Beatty’s four surviving battle cruisers.

At 17.33 hours, when the two main battle fleets were closing at nearly 40 miles an hour, Beatty’s most northerly ship, the light cruiser HMS Falmouth (1910–16; torpedoed south of Flamborough Head by U-63 and U-66 during the Action of 19 August 1916), part of the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron, sighted a warship in the haze five miles away. It proved to be the 1st Cruiser Squadron’s Black Prince, followed by the Defence and Warrior acting as outer scouts for the Grand Fleet. At 18.00 hours, Jellicoe’s flagship, the dreadnought battleship HMS Iron Duke (1912–46; scrapped), sighted the now badly damaged Lion and at 18.14 hours, after a delay that was caused by poor visibility, Beatty reported to Jellicoe on the position of the High Seas Fleet. At first, Jellicoe held his course, but at around 18.16 hours, after careful reflection, he ordered his ships to turn to port (eastwards) and change their normal cruising formation of six columns of four ships into one compact concave line that extended over six miles. This, Jellicoe hoped, would enable him to “cross the T”, a manoeuvre that had brought about the destruction of two-thirds of the Russian Fleet during the Russo-Japanese War at the decisive Battle of Tsushima (27/28 May 1905), and allow his battleships to direct a continuous succession of broadsides onto the German Fleet as it advanced northwards in a single line beyond Beatty’s and Arbuthnot’s ships.

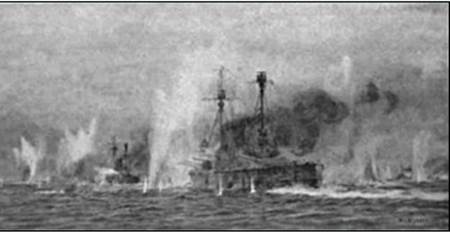

But for some 15 minutes during this complex and dangerous manoeuvre, there was considerable “turmoil”, as Massie put it, at what became known as “Windy Corner”, where a dozen groups of smaller ships like light cruisers and destroyers were trying to maintain their battle stations relative to their capital ships while steaming at full speed. The result, according to Andrew Gordon, was a “navigational nightmare” which involved several near-collisions and during which the impetuous Arbuthnot added to the confusion. For while, in theory, his scattered squadron’s armoured cruisers should have turned in such a way that they could have moved directly to the disengaged side of Jellicoe’s battle-line without getting in anyone’s way, his attention was drawn to the crippled German light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden (1915–16; finally sunk during the small hours of 1 June 1916 and currently still lying inverted on the sea bed). A shell from the Invincible had disabled her at 17.53 hours by exploding in her engine-room, and although she was on fire and adrift between the two converging battle fleets, she was still capable of firing salvoes. So Arbuthnot, who had made it very clear to his command that he would engage the enemy “remorselessly” whenever it came within the range of his guns, led the Defence and the Warrior into a cataract of fire from the big guns of the German High Seas Fleet and ordered the Defence to close with the Wiesbaden, firing with her forward 9.2-inch guns as she did so. By doing this he may also have believed that he was screening Jellicoe’s battleships from possible torpedoes, and that because his armoured cruisers lacked centralized director-firing, their turret captains would have lost sight of the target if his flagship had not headed straight for it. But as the Defence led the 1st Cruiser Squadron as it closed on the crippled Wiesbaden, “firing incredibly fast”, the Lion emerged from the haze and had to turn hard to port, missing the Defence by only two hundred feet and nearly ramming Warrior, which had to take sudden evasive action. But the two armoured cruisers succeeded in turning to starboard and poured broadside fire into the Wiesbaden, leaving her listing heavily. Nevertheless, at about 18.16 hours and despite the dire situation of his ship – which would finally sink with all hands apart from one survivor – the Wiesbaden’s Captain retaliated by ordering his guns to fire, and a salvo of 5.9-inch shells hit one of the Defence’s turrets. And at about the same time, Hipper’s battle cruisers and Scheer’s four leading battleships also emerged from the haze and engaged the two armoured cruisers at only 8,000 yards range, hitting the Defence with at least three salvos of 12-inch shells, one of which penetrated her after magazine next to ‘X’ turret and another of which struck her behind her forward turret seconds later. Other German ships added their firepower, and at about 18.20 hours on 31 May 1916 there was a massive explosion aboard the Defence, creating a huge cloud of black smoke. When it cleared, the sea was empty as the Defence had sunk very rapidly, becoming the third out of 14 British ships sunk during the Battle of Jutland, with the loss of her entire complement of 903 men, including Johnson, aged 37. According to one eyewitness, who was on board HMS Obedient (1916–19; sold 1921), a member of the 12th Destroyer Flotilla:

There was one incident at “Windy Corner”, which, alas, was more prominent than any other. From ahead, out of the mist, there appeared the ill-fated 1st Cruiser Squadron led by the Defence. At first, the Defence did not seem to be damaged, but she was being heavily engaged, and salvoes were dropping all around her. When she was on our bow, three quick salvoes reached her, the first one “over”, the next one “short” and the third all hit. The shells of the last salvo could clearly be seen to hit her just abaft the after turret, and after a second, a big red flame flashed up, but died away again at once. The ship heeled to the blow but quickly righted herself and steamed on again. Then[,] almost immediately[, there] followed three more salvoes. Again the first was “over”, the second one “short” and the third a hit, and again the shell of the hitting salvo could be clearly seen to strike, this time between the forecastle turret and the foremost funnel. At once, the ship was lost to sight in an enormous black cloud, which rose to a height of some hundred feet, and from which some dark object, possibly a boat or a funnel was hurled into space, twirling like some gigantic Catherine-wheel. The smoke quickly clearing, we could see no sign of a ship at all – Defence had gone. Mercifully this death, by which the 900 or so officers and men of the Defence perished, was an instantaneous one, causing them probably no suffering.

And according to another eyewitness, who was on board the Warrior, the Defence “suddenly disappeared completely in an immense column of smoke and flame, hundreds of feet high. It appeared to be an absolutely instantaneous destruction, the ship seeming to be dismembered at once.” Commander George van Hase, Chief Gunnery Officer on the Derfflinger, complemented these accounts as follows:

At 8.15 p.m. on 31 May 1916 we received a heavy fire. Lieutenant-Commander Hausser, who had been firing at a torpedo boat with our secondary battery, asked me: “Sir, is this cruiser with the four funnels a German or an English cruiser?” I directed my periscope at the ship and examined it. In the grey light the colour of the German and the English ships looked almost exactly the same. The cruiser was not at all far from us. She had four funnels and two masts exactly like our Rostock who was with us. “It is certainly English” exclaimed Lieutenant-Commander Hausser, “May I fire?” “Yes – fire away!” I said. I became convinced that it was a large English ship. The secondary guns were aimed at the new target and Hausser commanded “69 hundred!” At the moment in which he was about to order “Fire!” something horrible, something terrific happened. The English ship which I meanwhile supposed to be an old English battle cruiser, broke asunder and there was an enormous explosion. Black smoke and pieces of the ship whirled upward, and flame swept through the entire ship, which then disappeared before our eyes beneath the water. Nothing was left to indicate the spot where a moment before a proud ship had been fighting, except an enormous cloud of smoke. According to my opinion, the ship was destroyed by the fire of the ship just ahead of us – the Lützow, the flagship of Admiral Hipper. […] The whole thing lasted only a few seconds and then we engaged with a new target. […] I shall never forget the sight I saw through my periscope in all its gruesomeness.

So for 85 years it was generally assumed that the Defence had more or less disintegrated. But in 2001 a diving team from Deep Blue Expeditions located the wreck c.45 meters down at 56º 58′ 02″ north 05º 49′ 50″ east, some 90 miles off the northern tip of Denmark’s Jutland peninsular, and were surprised to discover that unlike the Invincible and the Indefatigable, now “reduced to shapeless lumps by a century of saltwater”, much of the Defence was intact, albeit with her turret roofs blown off. Although the hull below the waterline on both sides of the ship next to the magazine of ‘X’ turret has been destroyed – which explains why, although the Defence sank like a stone, she remains upright on the seabed, albeit fairly heavily silted and draped in fishing nets, with at least four of the 7.5-inch guns on her port side still turned outwards in the firing position. The divers also discovered that, unlike other Jutland wrecks, she had not been disturbed during the 1920s–30s and 1950s by prospectors dynamiting for ferrous material, and that even her propellers had not been removed. Over the next two years, Starfish Expeditions found that although her forward and aft gun turrets had been destroyed, ammunition in some of the side casements was still intact, and they even discovered a pile of unbroken plates from the wardroom pantry. Their photographs also suggest that the explosion blew off her bow and stern but that the midships section survived relatively intact. Subsequent dives in 2003 and 2015 confirmed these findings, and since 2006 the wreck has been designated under the Protection of Military Remains Act (1986).

After the destruction of the Defence, the Warrior was hit by 17 heavy shells that killed or wounded 107 men, ignited fires in several places, and caused her to list to starboard. But she was saved initially, partly because the Germans shifted fire onto the nearby 5th Battle Squadron, and partly because the damaged Warspite circled her and took a dozen heavy hits before the two ships could limp away. Warrior was then taken in tow but sank during the night with no further loss of life. The Black Prince, Arbuthnot’s third cruiser, had been too far to starboard to be involved in the action, but while seeking her designated night station in the rear of the fleet, she became isolated and lost, and blundered into the blacked-out German battle fleet. Raked by fire from four dreadnoughts at ranges of 500 to 1,000 yards, she became an inferno and exploded. The Duke of Edinburgh, Arbuthnot’s fourth cruiser, had been unable to follow her two sister ships across Beatty’s bows and managed to escape their fate by hauling away northwards in time and falling in with the battle cruisers.

After a confused night action the Battle ended on 1 June. Although the British had lost more men – 6,097 as against 2,551 – and more ships – 14 as against 11 (3 battlecruisers, 3 armoured cruisers and 8 destroyers as against 1 pre-dreadnought battleship, 1 battlecruiser, 4 light cruisers and 5 destroyers), several German capital ships had been badly damaged and the Royal Navy was able to retain control of the North Sea, an outcome that enabled the Allies to continue their blockade of German ports, thus starving Germany of raw materials and food, and although the Germans claimed the victory, the High Seas Fleet never again put to sea to challenge the Grand Fleet.

Johnson has no known grave, but is commemorated on panel 10 of the Plymouth Naval Memorial, and in the memorial book of St Mary’s Church, Shortlands, Kent, his mother’s home town. He left £409 3s. 4d.

President Warren said posthumously that “many will miss his sunny, amiable good nature and his pleasant wit”; his obituarist in The Lancet recorded that “he had a very keen sense of his duty to his medical work, to which he applied abilities considerably above the average” and that his many friends “felt certain that he would have done good and distinguished service in his profession” for “he had a boundless store of energy and lived his life with a zest and keenness it was a pleasure to watch” and had an “unusual capacity of forming real friendships sociably and professionally”. His obituarist in The London Hospital Gazette said something similar:

In his work he shewed much ability, and was always capable of dealing with any difficult situation. By his patients he was respected for his professional skill, and there were few who did not appreciate the sympathy which he extended, often accompanied by some expression of his peculiarly characteristic humour. To his friends – and, indeed, to all – he was ever true and very straight in all his actions. There was nothing lukewarm or indifferent about Johnson: he did all that he had to do very thoroughly.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would like to express their unreserved thanks to Nicholas Jellicoe (the 3rd Earl Jellicoe and grandson of Admiral Jellicoe) for allowing them to make extensive use of his minutely researched, fair-minded and authoritative book *Jutland: The Unfinished Battle (Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2018), without which two unrepentant landlubbers could not have steered their way through the complexities of a major naval engagement. Thanks are also due to Dr Roger Hutchins, who wrote an early version of this biography and helped the Editors get the final version into shape. And also to Benjamin Butcher, Library Officer, Cornwall Council, who despite the closures due to coronavirus was able to provide information on the West Powder Division Petty sessions of 1915.

Printed sources:

Cecil Francis Romer and Arthur Edward Mainwaring, The 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the South African War (London: A.L. Humphreys, 1908).

[Anon.], ‘A Perranporth Visitor: Fined for Exposing Lights near the Sea’, West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, [no issue no.] (30 August 1915), p. 3.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, no. 22 (9 June 1916), p. 359.

[Anon.], ‘George Moore Johnson MA, MB, BCh Oxon.’ [obituary], The Lancet , 2, no. 4,842 (17 June 1916), p. 1,235; reproduced as [Anon.], ‘Obituary: Surgeon G.M. Johnson’, The London Hospital Gazette, vol. 21, no. 7, issue 192 (July 1916), p. 330.

W[illiam] J[enkins] O[liver], ‘Surgeon G.M. Johnson’ [obituary], The London Hospital Gazette, 21, no. 7, issue 192 (July 1916), pp. 330–1.

There is a small but dramatic watercolour of the action in W.L. Wyllie’s More Sea Fights of the Great War including the Battle of Jutland (London: Cassell, 1919).

Harold William Fawcett and Geoffrey William Winsmore Hooper, The Fighting at Jutland: The Personal Experiences of 45 Officers and Men of the British Fleet (London: Macmillan, 1921), esp. pp. 192 and 198; also available on-line (Internet Archive 2019) at: https://archive.org/details/fightingatjutlan0000fawc/ (accessed 13 October 2020).

Günther (1924), pp. 434–5, 466.

Innes McCartney, ‘In Search of Jutland’s Wrecks’, Dive Magazine (1 March 2002), press release of 8 June 2001.

Rodge (2003), pp. 93–9, 102.

Leslie Hollis, HMS Duke of Edinburgh, IWM Docs, typescript memoir, p. 8., cited in Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, Jutland 1916 (London: Cassell, 2004), p. 199.

Callwell (2005), pp. 78–85, 147–65.

Lawrence Burr, British Battlecruisers 1914–18 (Osprey Publishing [Bloomsbury Publishing], 2006) p. 42.

Robert K[inloch] Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (London: Vintage Books [Random House], 2007), pp. 30, 40–6, 53, 182, 208–21, 237–44, 249, 254, 284, 613–18, 635, 647, 656.

Ford (2010), pp. 224–9.

Innes McCartney, ‘The Armoured Cruiser HMS Defence: A case-study in assessing the Royal Navy shipwrecks of the Battle of Jutland (1916) as an archaeological resource’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 41, no. 1 (March 2012), pp. 56–66; typescript also available on-line at http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/29393/3/HMS%20Defence%20ijna%20submission%20IJM%20final%20for%20BURO.pdf (accessed 20 October 2020.

Andrew Gordon, The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command (London: Penguin [Random House], 2015), pp. 392–3, 430, 441–6.

Chris Leadbeater, ‘The North Sea yields its secrets’, The Daily Telegraph, no. 50,074 (21 May 2016), pp. 14–15.

Jellicoe (2018), pp. 42–101, 112–17, 128, 140, 199, 386 n.13.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/721 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to G.M. Johnson [1916]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

MCA: PF2/13 (President’s Notebooks), pp. 67, 93, 139 and 189.

OUA: UR 2/1/33.

Royal London Hospital Archives: MC/S/1/9 (Student Register F, 1903–07).

WO 95/4310: 1 Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers: War Diaries for Jan 1915–Jan 1916; May–June 1915 missing.

Cornwall County Archives, Truro: AD81/8 (Minutes, Petty Sessions, West Powder Division, Truro [1912–28])

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Jutland’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Jutland (accessed 11 October 2020).

Wikipedia, ‘Order of battle at Jutland’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_battle_at_Jutland (accessed 11 October 2020).