Fact file:

Matriculated: 1910

Born: 6 March 1892

Died: 9 November 1918

Regiment: London Regiment (Artists’ Rifles)

Grave/Memorial: Tournai Communal Cemetery (Allied Extension): V.D.1

Family background

b. 6 March 1892 as the only child of Gervase O’Bryen (also O’Brien) Alington (1851–1929) and Mary Charlotte Swan Alington (née Lister) (1854–1944) (m. 1887). At the time of the 1911 Census the family was living at Killard, New Road, West Malvern, Herefordshire (two servants), but after their son’s death, Alington’s parents moved to 9, Montpelier Grove, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire.

Parents and antecedents

The Alingtons are an ancient Cambridgeshire family, particularly associated with the village of Horseheath, a few miles south-east of Cambridge, where several of the family are buried. One of them was killed at the Battle of Bosworth (22 August 1485), the final battle of the Wars of the Roses, and the family came into particular prominence under the Stuarts. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many of them became clerics.

The Reverend John Alington (1801–83), Alington’s grandfather, was a Demy (Scholar) at Magdalen from 1818 to 1825. He was awarded a BA in 1822 and an MA in 1825, and from 1825 to 1835 he was a Fellow of Magdalen, during which time he acted as Senior Dean of Arts (1828–29) and one of the Bursars (1830). From 1832 to 1834 he was Rector of Croxby, near Caistor, Lincolnshire, a parish of 140 souls and with a gross income of £329 p.a. that was in the gift of Magdalen; and in 1834 he became Rector of Candlesby, a parish of 235 souls in the same diocese that was also in the gift of Magdalen and paid a gross stipend of £206 p.a. By 1861 he was the Vicar of Luddington, yet another Lincolnshire parish.

Alington’s father studied at Queen’s College, Oxford, from 1868 to 1872, when he was awarded a BA. He was awarded an MA in 1879 and two years later he was an assistant master at a preparatory school in or near Torquay. At the time of the 1911 Census he described himself as an artist/painter but there is no record of his works.

Alington’s mother was the daughter of a clergyman, the Reverend Thomas Henry Lister (1819–89), who studied at St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, and was awarded a BA in 1847 and an MA in 1851. He was ordained deacon in 1847 and priest in 1848; from 1848 to 1865 he was Vicar of Luddington, Lincolnshire, and from 1878 to 1882 he was Rector of Somersby with Bag Enderby, also in Lincolnshire. Alington’s maternal uncle, the Reverend James Stovin Lister (1863–1928), was also a clergyman. He studied at Clare College, Cambridge, and was awarded a BA in 1888 and an MA in 1892. He was ordained deacon in 1889 and priest in 1891; from 1889 to 1892 he was Curate of Hope-under-Dinmore, Herefordshire; from 1892 to 1894 he was Curate on Broughton, Lincolnshire; from 1894 to 1895 he was Curate of South Stoke, Buckinghamshire, and from 1895 to 1896 he was a Chaplain in Madrid. On his return he became Vicar of Kilmeston with Beauworth, near Alresford, Hampshire, from 1897 to 1904 and then Curate of Pill, Somerset, from 1905 to 1906, when he took over his father’s old parish of Somersby with Bag Enderby.

Gervase Alington was a cousin of Geoffrey Hugh Alington.

He was also a cousin of the Reverend (later Right Reverend, DD) Cyril Argentine Alington (1872–1955), a prominent cleric, educationalist and classical scholar who was elected Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, in 1896. Although he was ordained priest in 1901, Cyril Alington began his career as an assistant master at Marlborough from 1896 to 1899, then moved to Eton until 1908, when he became the Headmaster of Shrewsbury and was responsible for the appointment of E.H.L. Southwell as an assistant master there. In 1917 he returned to Eton as Headmaster and stayed there until 1933, when he was made Dean of Durham (until 1951). From 1921 to 1933 he was Chaplain to King George V. In World War Two his youngest son, Patrick Cyril Waynflete Alington (1920–43), was killed in action at Salerno, aged 23, while serving as a Captain in the 6th Battalion of the Grenadier Guards: he is buried in Salerno War Cemetery, Grave III.A.47. Cyril Alington was also a prolific author: he has 68 entries in the Bodleian catalogue: between 1922 and 1954 he published at least 15 works of fiction and between 1914 and 1954 he published at least 31 other works on a variety of topics and in a variety of genres (including witty light verse).

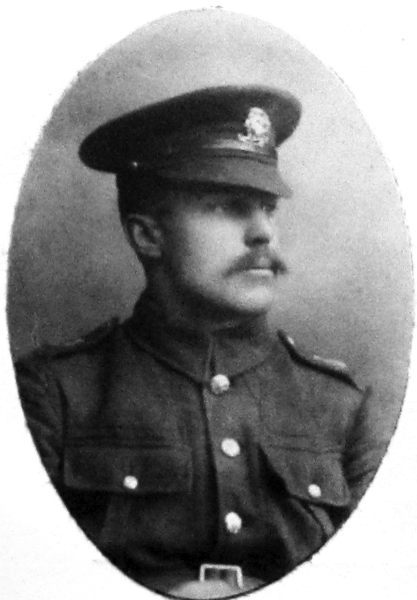

Gervase Winford Stovin Alington, BA, MM and Bar, from a College group photograph 1912

(Courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Education and professional life

Alington attended Hill Side Preparatory School, West Malvern, Worcestershire (now defunct), from 1901 to 1905. But in 1864, his maternal grandmother, Gertrude Isobel Frances MacLaren (1833–96), a classical scholar, had established Summer Fields Preparatory School on a 70-acre site in north Oxford, where it still exists today (cf. G.H. Alington, A.J.B. Hudson, A.M.F.W. Porter, E.G.R. Romanes, T.Z.D. Babington). Alington studied there from 1905 to 1906, and finally attended Radley College, where he was an Exhibitioner, from 1906 to 1910. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 18 October 1910, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1910. He took his First Public Examination in Trinity Term and October 1911, and then read for a Pass Degree from 1913 to 1914 (Groups A1 [Greek and/or Latin Philosophy/Literature], B3 [Elements of Political Economy], and D [Elements of Religious Knowledge]). He may have resat some of these in Trinity Term 1915 and he finally took his BA on 24 June 1915. In the interval between leaving Magdalen and joining the Army, he lived at 4, Spa Buildings, Cheltenham, and when he was finally accepted as a recruit, he gave his profession as “School Master”. An obituarist writing in the Parish Magazine of St James’s Church, West Malvern, the village where Alington’s parents were living at the time of their son’s death, noted that Alington used to read the lessons there at morning service and was hoping to take Holy Orders after the war.

War service

Alington was probably in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) throughout his time at Magdalen and tried to enlist in the Army on the outbreak of war. But he was told then and on two subsequent occasions – once by the Inns of Court OTC – that he was not acceptable for military service because of a knee injury. Nevertheless, he was deemed to have enlisted on 2 March 1916 and was called up for service in autumn 1917, when British losses were running very high because of the unceasing fighting around Ypres. When President Warren later asked Alington’s father about his son’s military experience, the latter replied, in a letter of 27 June 1919, that he knew nothing about it as his son had been “scrupulously silent on all his doings”. He was, however, able to tell Warren that on 6 September 1917, Gervase, who was only 5 foot 4 inches tall, had been accepted as “Potential Officer Material” by the Artists’ Rifles, i.e. the 2/28th (County of London) Battalion of the London Regiment, which was used as an Officers’ Training Battalion for likely candidates with no military experience (cf. W.A. Fleet). So Alington trained with No. 15 Officer Cadet Battalion at Hare Hall, Romford, Essex, and was promoted Corporal on 1 February 1918.

On Easter Sunday, 31 March 1918, Alington embarked for France as part of a draft, and for two days, 1–2 April 1918, he was attached to the 1/28th Battalion of the London Regiment, another battalion of the Artists’ Rifles, which was by then a line battalion and part of 190th Brigade in the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division. On 3 April 1918, i.e. just two days before the end of the German spring offensive known as Operation Michael (21 March–5 April 1918), Alington was formally transferred to the 1/17th (County of London) Battalion of the London Regiment (Poplar and Stepney Rifles), a unit that was largely recruited from the East End of London and formed part of the 140th (4th London) Brigade in the 47th (1/2nd London) Division. At the time of Alington’s transfer, it was in the support trenches on the Bouzincourt–Martinsart road just north of Albert, which was held by the Germans from 26 March to 22 August 1918. By 6 April Alington had joined his new Battalion in the trenches between Senlis-le-Sec and Warloy-Baillon, to the west of Albert, and two days later, when it had moved up to billets in Hédauville, two miles north-west of Albert, he reported sick with a mild attack of trench foot and then spent a week in hospital at Rouen and about ten more days convalescing and recruiting at Trouville, on the coast. By the time he returned to the Battalion towards the end of April, the Battalion must have been in billets again at Warloy-Baillon, and it spent the next three months in the support and front-line trenches in that part of the Somme front which lies to the south and south-west of Albert, with occasional periods in Reserve much further away to the west.

The Second Battle of the Somme (also known as the Second Battle of Bapaume) began on 21 August and ended on 3 September with the capture of Mont St-Quentin and Péronne, and its first two days, i.e. 21 and 22 August, are sometimes given the subtitle of the Third Battle of Albert because of the recapture of that pivotal town from the Germans on 22 August, when Alington’s Battalion was still in Reserve at Baizieux, about five miles west of Albert. But the Battalion then took part in its first major action, the push eastwards through Albert to the Hindenburg Line, and by 25 August the fighting had cost it seven officers and 118 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing. On 30 August 1918 it advanced ten miles eastwards through Maricourt to a point near the village of Maurepos, and on the following day it took part in the successful attack on Rancourt, three miles to the north-east, at the cost of relatively few casualties. On 2 September it was near the village of Moislains, some four miles north of Péronne where there was an important bridge across the north–south Canal du Nord, and the War Diary reads as follows:

At 3 a.m. a written message was received altering the operations to some extent. 140th Bde were now to follow in [the] rear of 74th Division, the latter being responsible for taking and mopping up Moislains. The 140th Bde was to cross the Canal du Nord south of Moislains, in [the] rear of 74th Division, and swing north to join up with the 142nd Bde.

On coming down the forward slopes to the west of the Canal at Moislains, the 1/17th Battalion came under extremely heavy artillery and machine-gun fire from the town itself. Nevertheless, the Battalion pressed forwards, crossed the Canal, and on 6 September 1918 assisted in the capture of the large crossroads village of Liéramont, just under five miles north-east of Péronne, which the Allies had taken by then. But the fighting between 1 and 5 September had cost it nine officers and 262 ORs killed, wounded or missing, and on 6 September the survivors were pulled back c.25 miles westwards to the village of Heilly, around. three-and-a-half miles north of Corbie from where, over the next six days, it made is way northwards to the town of Auchel, about eight miles south-west of Béthune, where it stayed until 26 September 1918.

During the period from 24 August to 22 September 1918, Alington was a runner, came through without a scratch, and, together with 15 other members of the 1/17th Battalion, received the MM from his Colonel on 26 September 1918 for the part he had played in the encirclement and capture of Péronne. On 27 September 1918 the Battalion marched 12 miles south-westwards to the village of Brias; on 3 October it moved north-eastwards to the town of Merville, and thence a few miles eastwards to Lestrem; and it spent from 5 to 16 October in and out of the front line in the general area of Laventie/Fromelles/Estaires until it was pulled back westwards to St-Floris and then eight miles south-westwards to St-Hilaire-Cottes (17 October), where it trained until 25 October 1918. On 22 October Alington was awarded the Bar to his MM; on 26 October 1918 his Battalion advanced eastwards to billets at Lomme-Canteleu, a western suburb of Lille (which the retreating Germans had evacuated on 17 October); on 28 October it marched through Lille itself; and by 1 November 1918 Alington had joined the HQ Section of the Battalion’s ‘A’ Company when it was in the support trenches at Honnevain, two miles north-west of Tournai (Doornik) in Belgium. Here it was subject to shelling for three days until, on 4 November 1918, Alington’s Battalion relieved another battalion of the London Regiment in the trenches in front of Froyennes, a mile or so to the south-east, where it stayed until 7 November. Once again it was shelled, but suffered no casualties, and on 8 November 1918 the Battalion War Diary noted that according to reports from civilians, the enemy had evacuated the western portion of Tournai after four years of occupation.

Consequently, when the Battalion sent out daytime patrols, these were not met with fierce defensive fire and were, despite nine OR casualties, able to establish that the Germans were still holding the east bank of the River Escaut. On 9 November 1918 the Germans withdrew still further eastwards, even from their position on the east bank, and once this withdrawal had been confirmed, orders were issued to throw a pontoon bridge across the River Escaut. This task was accomplished by 08.30 hours, and by 11.00 hours on the same day the entire Battalion had walked across the river in single file and taken up the line that runs from the railway in the south of Tournai, through La Tombe in the centre, to the suburb of Kain in the north. But when scouts began to advance through the town towards the high ground on its north-east side, they met with opposition from machine-guns that were concealed in a wood just outside the town. But the advance continued, the machine-guns were withdrawn, and by dusk the Battalion had reached the village of Melles – according to civilian reports about 15 minutes after the Germans had left. The Battalion War Diary recorded that during this advance, which continued without loss as far as Montroel-aux-Bois on the following day, two (unnamed) ORs had been killed in action, one of whom must have been Alington, aged 26. One of his fellow non-commissioned officers, Corporal C.J. Hibbard, subsequently wrote to Alington’s parents:

Corp[ora]l Alington was truly & honestly one of the most respected men in the whole company, not only by the men, but by the officers. Being with him day & night, week after week, I saw & have often tried to copy his unfailing patience and good-humour. I have never heard him say an unkind thing, or do a mean action. I don’t think he could. This is a regiment made up of some of the roughest East End men, yet every night & morning, in the line & out, Corporal Alington […] got on his knees & offered up his daily prayers. He never failed to attend any service we were able to have & was undoubtedly the padre’s most helpful member. He was the coolest man by far I ever saw up the line, and I have seen some cool ones.

Other former comrades wrote that “he was absolutely fearless in action” and that “his conduct often calmed me down”. Alington’s Company Commander wrote to his parents in similar vein:

Day by day, as we grew in acquaintance, the perception of his sterling qualities, mental & intellectual, engendered in the hearts of his comrades – Officers & men – an appreciation, an admiration, which in my long experience of warfare I have very rarely seen equalled & never surpassed. His tranquillity in all circumstances proved that he saw the affairs of life & death in their proper perspective. Thro’ it all his devotion to his religion never failed. His death coming at the 11th hour as it did is the more regrettable.

And his obituarist in the Malvern News, who had clearly been given access to the many letters of condolence received by Alington’s parents, echoed Corporal Hibbard’s view of the exceptional roughness of the men in his Battalion and stated that their son “won the respect and affection of his comrades, both by his gallantry and by the simple, unassuming goodness of his deeply religious character; [and they] grew to respect him and to love him”.

The news of Alington’s death reached C.C.J. Webb on 22 November 1918, who wrote in his Diary: “He was his parents’ only child & they were wrapped up in him”, and four days later, on 26 November, Alington’s father wrote an impassioned letter to President Warren which bears out Webb’s opinion:

for the present we are wonderfully upheld by God’s mercy thru’ the prayers of our friends & his & by a great sense of thankfulness so that at times even waves of joy pass thro’ us. For without presumption I feel we can say God has taken him to himself because He loved him. This “absolute fearlessness” in one of his nature was nothing less than a direct gift from God & I believe the Medal & Bar were won for us to treasure when he was gone as well as for an example to his men.

Alington was buried first in the grounds of the White Château, Froyennes (a village to the north-west of Tournai); then in Tournai Communal Cemetery (Allied Extension), just off the Douai road that runs south-west from Tournai, Belgium, Quartier Sud (Faubourg Notre Dame Auxilliatria), Grave V.D.1, inscribed: “Faithful unto death” (Revelation 2:10). He is commemorated on a brass plaque in St Benedict’s Church, Candlesby, Lincolnshire, where his grandfather had once officiated. He left £223 6s. 2d.

Tournai Communal Cemetery (Allied Extension), just off the Douai road that runs south-west from Tournai, Belgium, Quartier Sud (Faubourg Notre Dame Auxilliatria); Grave V.D.1.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed material:

Peter C. McIntosh, ‘MacLaren, Archibald (1819?–1884)’, DNB, 35 (2004), p. 722.

A.F.R., ‘In Memoriam: Gervase Winford Alington’, Malvern Gazette, no. 1,073 (29 November 1918), p. 2; also as ‘A.F.R. writes’, Malvern News, no. 2,579 (30 November 1918), p. 2.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 114–16, 125–6, 146–7.

Archival material:

MCA: PR32/C/3/23-33 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to G.W.S. Alington [1918–1919]).

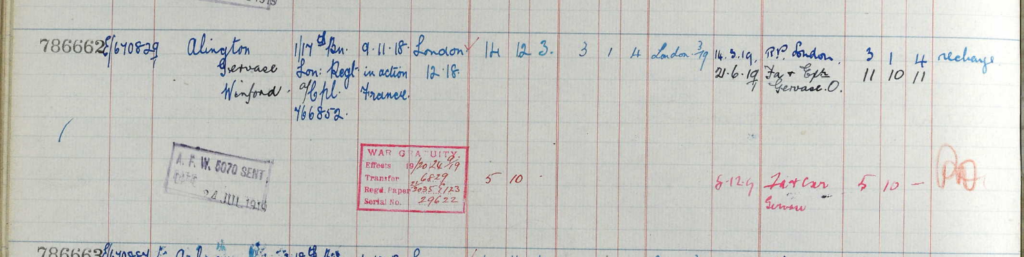

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/71.

WO95/2732.

WO95/3119/2.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Cyril Argentine Alington’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyril_Alington (accessed 8 April 2019).