Fact file:

Matriculated: Did not matriculate

Born: 7 February 1896

Died: 26 October 1916

Regiment: South Wales Borderers

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Pier and Face 4A

Family background

b. 7 February 1896 at Falcondale, Lampeter, Cardiganshire, as the eldest son (of four children) of Major John Charles Harford, DL, JP, 1st Baronet (1860–1934) and Blanche Annabel Harford (née Raikes) (1860–1904) (m. 1893). At the time of the 1901 Census the family (with seven servants) was living at Falcondale Manor, Lampeter, Cardiganshire (seven servants living in), where Harford’s father was lord of the manor.

Parents and antecedents

The Harfords were a wealthy land-owning family that had migrated from Marshfield, Gloucestershire, and settled at Bristol during the seventeenth century. One of Harford’s paternal great-grandfathers, Abraham Gray Harford (1786–1851), assumed by Act of Parliament the surname and arms of Battersby on inheriting the estate of his kinsman, William Battersby (b. c.1737) in 1815. But Harford’s grandfather, John Harford Battersby, JP, DL (1819–75), had his name changed back to Battersby Harford by Royal Decree in 1850. Harford’s other paternal great-grandfather was Christian Charles (Baron) von Bunsen (1791–1860), a former Prussian Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in London (1838–39 and 1841–54), who, on behalf of Frederick William IV of Prussia, negotiated the establishment of a Prusso-Anglican bishopric in Jerusalem. He married Frances Waddington (1791–1876) from Llanover, Monmouthshire, whose younger sister was Augusta Hall (1802–96), Lady Llanover, patron of Welsh culture and the inventor of the Welsh national costume. They met in Rome and he wrote to his sister: ‘An English family with three daughters, who are here, take a great interest in me.’ Through his wife von Bunsen developed an enthusiasm for Welsh culture, attending the National Eisteddfod in 1838. In 1840 he adjudicated in an essay contest on ‘The effect which Welsh Traditions have had on the Literature of Germany, France, and Scandinavia’, which was won by the German Arthurian Scholar Albert Schultz (1802–93). His wife Frances wrote a memoir of her husband.

In 1850 John Battersby Harford married Mary Charlotte von Bunsen (c.1830–1919), one of von Bunsen’s ten children. His sister married another, the Reverend Henry George Bunsen (1818–85), who was educated at Rugby School (his father being a friend of Thomas Arnold (1795–1842)) and who in the late 1830s attended Oriel College, Oxford, at the time of the Tractarian controversy and graduated with a 2nd in Literae Humaniores in 1840. He held various ecclesiastical positions including that of domestic chaplain to the Duke of Sutherland, who made him Rector of Donington, one of the Duke’s patronages. He was naturalized British by private act in 1842.

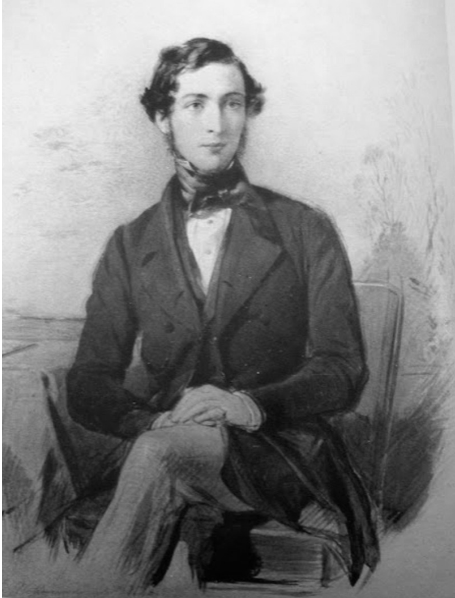

John Battersby Harford (1819–75), Harford’s grandfather

John Battersby Harford was a contemporary at Balliol of his brother-in-law Henry George Bunsen, taking his BA in 1841. After his marriage he settled in Westbury on Trym, Gloucesteshire, taking over the estate of Stoke Park, which his father had bought in 1838. In 1851 he was commissioned Captain in the 1st Gloucestershire Artillery, and was High Sheriff of Bristol. By 1860 he had become President of the Board of Trustees of Bristol Royal Infirmary and Honorary Secretary of the Bristol School of Practical Art; in 1861he became Sheriff of Gloucestershire. In 1866 he inherited the estates of his uncle John Scandrett Harford (1785–1866) of Blaize Castle, who died childless; these estates included Falcondale Manor near Lampeter. In 1869 he sold Stoke Park and lived both in Blaize Castle House and Falcondale Manor, taking up positions in both Gloucestershire and Cardiganshire.

Harford’s father was described during his lifetime as “one of the most active public men in the County of Cardigan”. A Conservative politician who twice – unsuccessfully – stood for Parliament, he was also High Sheriff of Cardiganshire in 1885, served as that County’s Deputy Lieutenant from 1886 to 1887, and was on the Commission of the Peace for Cardiganshire and Gloucestershire. He retained Blaize Castle Estate until it was sold to Bristol City Council in 1926. This allowed him, like his father, to hold positions in both Gloucestershire and Cardiganshire. He was also prominent in the affairs of the neighbourhood of Lampeter and became Mayor of that town from 1887 to 1888. He was a member of the Councils of the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, and St David’s College, Lampeter, Chairman of the Four Counties’ Farm, and a Trustee of the Diocese of St David’s. He served in the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment (London Gazette, no. 24,810, 10 February 1880, p. 625) before joining the 2/1st Pembrokeshire Yeomanry, a distinguished volunteer regiment which dates back to 1794, played a major part in repelling the French invasion of Britain at Carag Wasted Point in 1797, and fought as part of the Imperial Yeomanry in the Second Boer War (LG, no. 27,364, 11 October 1901, p. 6,647). He resigned from this Regiment as Major in 1904 (LG, no. 27,675, 10 May 1904, p. 3,005), the year in which he became Chairman of the County of Cardigan Territorial Association. From 26 August 1914 until 1916 he served with his old cavalry regiment as Captain (26 August 1914; Hon. Major 23 October 1915) and was sent to France on 13 June 1917, where he served as a Town Major and Army Commandant until 1918. In 1926 he became Chairman of Quarter Sessions for Cardiganshire. A keen agriculturist, he devoted much time to promoting the welfare of farming and the farming industry; an enthusiastic sportsman, he particularly enjoyed hunting and shooting and finally dropped dead unexpectedly on a golf course, a month after he had been made the 1st Baronet Harford in June 1934 for political and public services, and a week before he was to receive the freedom of Lampeter. His estate was worth the equivalent of £6 million in 2005.

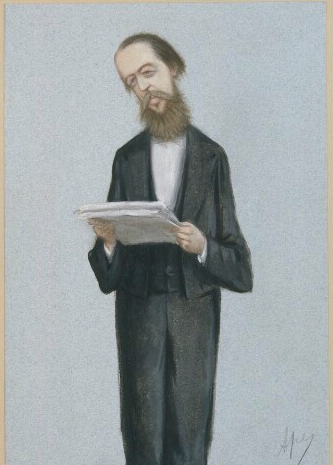

Harford’s maternal grandfather was the Right Honourable Henry Cecil Raikes, PC, JP, DL (1838–91), of Llwynegrin, Mold, Flintshire, a barrister, journalist and distinguished parliamentarian who was MP for Chester (1868–80), Preston (1882) and Cambridge University (1882–91), Principal Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons and Chairman of Ways and Means (1874–80), and Postmaster-General in Lord Salisbury’s second administration (1886–91). He was also a prominent member of the Anglican laity.

Henry Cecil Raikes by Carlo Pellegrini, watercolour, published in Vanity Fair, 17 April 1875

(NPG 2596 © National Portrait Gallery, London)

His maternal grandmother was Charlotte Blanche, née Trevor-Roper (1836–1922), second daughter of Charles Blayney Trevor-Roper (1799–1881) of Plas Teg Mold. She was a first cousin of Bertie William Trevor-Roper (1885–1978), the father of the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper (later Lord Dacre) (1914–2003).

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Mary Annabel (“Mollie”) (1894–1966), later Hill after her marriage in 1916 to Charles Loraine Hill (1891–1976); marriage dissolved in 1944; two sons, three daughters;

(2) George Arthur (later Sir, JP, DL, OBE, 2nd Baronet (1897–1967), who in 1931] married Anstice Marion Tritton (1909–93); two sons, one daughter;

(3) William (b. 1899, d. in infancy).

Charles Loraine Hill was the son of Charles G. Hill (1861–1934), a member of the Hill family whose Bristol ship-building firm dates back to 1704. He was also the founder of the major Bristol ship-building firm Charles Hill & Sons (1845–1975), and the Bristol Shipping Line (1879–1970). In 1919 he and his family were living at 2 Dirleton Terrace, Llandeilo.

George Arthur was educated at Harrow and the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) and then joined the 21st (Empress of India) Lancers from 1917 to 1923. He was promoted Lieutenant in 1918 and in the same year went to India, where he served on the headquarters staff of the Meerut Division. From 1940 to 1945 he served in the 17th/21st Lancers and on the General Staff. From 1938 to 1939 he was High Sheriff of Cardiganshire.

Education

Harford attended Durnford House Preparatory School, Wareham, Dorset, from 1906 to 1910, and then Harrow School from 1910 to 1914, where he acquired his Certificate ‘A’ and became a Corporal in the Harrow (Junior) Officers’ Training Corps. He was also Captain of his House cricket XI, played Rackets, and ran cross-country for his House, being the winner in 1914. Magdalen accepted him as a Commoner in 1914 but he did not matriculate.

John Henry Harford (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford, and also Harrow Memorials, iv, 1919, unpaginated)

“He went to his death like a gallant gentleman”.

Military service

On 31 August 1914, Harford applied for a permanent commission with the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, the South Wales Borderers, and in September was given a commission as Second Lieutenant with effect from 15 August (London Gazette, no. 28,918, 29 September 1914, p. 7,692). He was then transferred to the Regiment’s 2nd (Regular) Battalion, i.e. the Battalion (LG, no. 29,121, 6 April 1915, p. 3,433) which had been largely wiped out by the Zulus at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 only to distinguish itself at Rorke’s Drift on the following day. The 2nd Battalion had also been the only British unit to take part in the Japanese-led siege of the German naval base and colony (since 1898) of Tsingtao (552 square miles, now Qingdao, China), from 31 October until 7 November 1914.

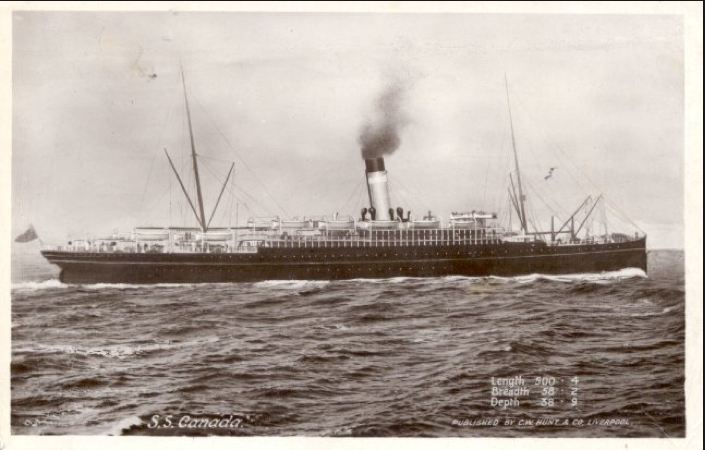

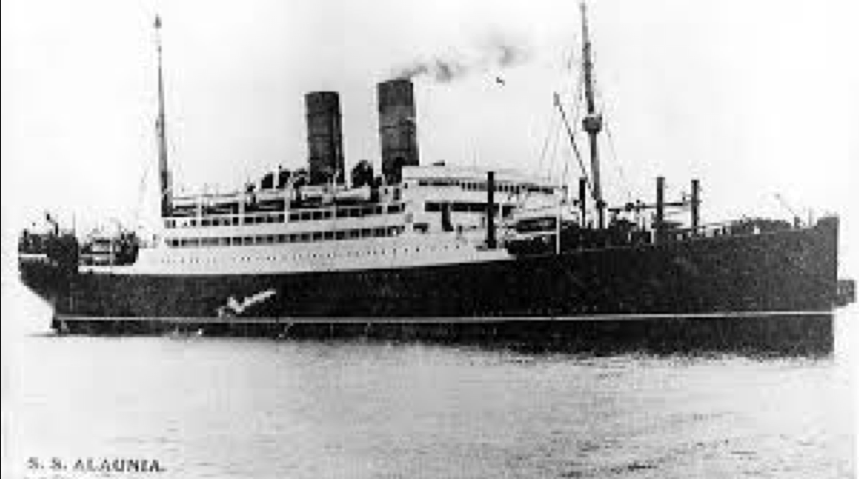

In December 1914 the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers had embarked at Hong Kong and sailed to Plymouth, where it arrived on 12 January 1915. It spent the next two-and-a-half months training in the techniques of trench warfare near Rugby, where Harford joined it, as part of 87th Brigade, in the 29th Division. This was commanded by Major-General Aylmer Hunter-Weston (1864–1940) and consisted of Regular battalions that had been taken off garrison duty all over the Empire. The 29th Division, comprising 12 battalions and some 18,000 men, began to leave for the Gallipoli peninsula on 10 March 1915, and on 17 March 1915 most of Harford’s Battalion, i.e. 26 out of 27 officers and 938 out of 1,080 other ranks, set out from Avonmouth on the SS Canada. Travelling via Malta, the Battalion arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 29 March. On 9 April, after a period of re-equipment and acclimatization in Mex Camp, five miles outside the city, the Battalion left Egypt, mainly on the SS Alaunia (cf. E.G.R. Romanes; H. Irvine).

RMS Alaunia (1913; sunk by a newly laid German mine on 19 October 1916 off the Royal Sovereign Lightship, near Hastings, East Sussex, with the loss of two lives)

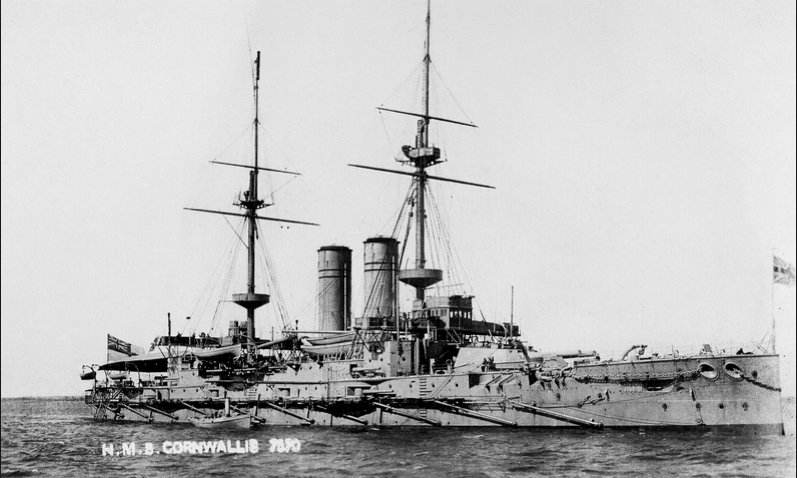

On 11 April the Battalion arrived in Mudros Harbour, on the Greek island of Lemnos, about half-way between the Peloponnese and Gallipoli; and on 21 April, after extensive training and preparation for the attack that was planned on the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, most of the Battalion left Lemnos for the Greek island of Tenedos (now the Turkish island of Bozcaada), which is to the south of the Dardanelles and much closer to the Turkish coast. In the afternoon of 24 April, the Battalion’s ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies transferred from the Alaunia to the pre-Dreadnought battleship HMS Cornwallis – which had been active around the Dardanelles shelling Turkish positions since 18 February 1915 – and left Tenedos at 22.00 hours.

HMS Cornwallis (1904; torpedoed with the loss of 15 lives by UB32 on 9 January 1917 c. 63 miles east of Malta)

At 03.30 hours on 25 April, the Cornwallis arrived to the west of Tekke Burnu (Cape Tekke), just north of Helles Burnu (Cape Helles), on the southernmost tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula, ready to play its part in the landing by 29th Division on five beaches designated by the letters ‘X’,‘Y’,‘W’,‘V’ and ‘S’ (see hand-drawn map prefacing A.M.F.W. Porter). It is not known in which Company Harford was an officer, but between 05.00 and 07.30 hours on 25 April, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies of the 2nd Battalion, the South Wales Borderers, landed on ‘S’ Beach, a three-mile stretch of sand at the right-hand end of Morto Bay on the south-eastern side of Cape Helles. But for lack of sufficient room aboard HMS Cornwallis, ‘A’ Company, commanded by Captain Roland Gaskell Palmer (b. 1876 in Sydney, Australia, d. 1915), together with the 1st Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the Plymouth Battalion of the Royal Marine Light Infantry (60th (Royal Naval) Division), landed on ‘Y’ Beach, on the western side of the tip of Helles Burnu and 3,000 yards to the west of the key village of Krithia (Alçitepe) (see also I.B. Balfour).

The landing on ‘S’ Beach was a diversionary attack, whose purpose was to draw Turkish attention away from the four main landings on the western side of the peninsula, beyond the village of Sedd-el-Bahr and over two miles away. But ‘S’ Beach was not protected by barbed-wire entanglements, and it was almost undefended apart from a Turkish trench halfway up the 200-foot-high cliffs known as Eski Hissarlik, from where, nevertheless, its 17 defenders could defilade the beach with direct rifle and machine-gun fire. ‘D’ Company, the first to land, succeeded in scaling the cliff that rose up from the beach and then outflanked and enfiladed the Turkish trench. Consequently, the Battalion was soon able to capture the observation post on top of the cliffs that had been known as De Tott’s Battery since the Russo-Turkish War of 1768 to 1774. But the attack then stalled in front of Hill 236, some 500 yards to the north of ‘S’ Beach, and the Battalion, after suffering about 65 casualties killed, wounded or missing, followed orders by digging in and staying where it was until it was relieved by the French in the early hours of 28 April.

Meanwhile, by 05.45 hours on 25 April, the British invading force, including ‘A’ Company of the 2nd Battalion, the South Wales Borderers, had landed unopposed in small boats known as cutters on ‘Y’ Beach, a narrow strip of sand on the western coast of the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, about five miles north from Cape Hellas (Helles Burnu) and two miles west-north-west of the village of Krithia (Alçitepe). Here, its principal task would consist in taking the strategically placed hill-top village of Achi Baba, roughly another two miles past Krithia. When the Battalion landed, the heavily laden men were faced with cliffs between 150 and 200 feet high, but were able to get to the top of them via apparently undefended gullies. When they arrived there, there was no sign of the enemy, and when patrols finally discovered the Turks, they were found to have retired in strength behind a ridge c.1,200 yards north of the Battalion’s left flank. So at c.15.00 hours the attackers, the Battalion, who had no spades or picks in their kit, formed a long and therefore thinly held defensive semicircle on the top of the cliffs, using entrenching tools to make a shallow trench in the rocky ground and their packs as substitutes for sandbags.

At 16.00 hours the Turks, supported by machine-guns and artillery, launched the first of several counter-attacks against the thinly held British positions which continued throughout the night of 25/26 April and were driven off with the bayonet in fighting that became increasingly hand-to-hand and savage. The Turkish counter-attacks went on until about 07.00 hours on 26 April 1915, when the centre of the British line finally broke, sending some men back down the cliffs to ‘Y’ Beach. But the survivors of the 1st Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) and ‘A’ Company of the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers counter-attacked with bayonets, causing the Turks to withdraw, but not before they had inflicted 697 casualties on the British Battalions, 296 of which came from the 1st Battalion of the KOSB, including its Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Stephen Koe (1865–1915), and 70 from ‘A’ Company of the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers. Indeed, because of the high level of casualties and the shortage of small arms ammunition of the appropriate calibre, the British situation on ‘Y’ Beach and the cliffs above it had become so difficult that the senior officer of the ‘Y’ Beach force, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier) Godfrey Estcourt Matthews (1866–1917; killed in action at Cambrin on 13 April 1917) of the Royal Marine Light Infantry, decided unilaterally that he no longer had enough properly equipped troops at his disposal. So having heard nothing from Divisional HQ during his 29 hours on ‘Y’ Beach, at about 09.30 hours he ordered his depleted troops to evacuate the poorly defended cliff-top, starting with the wounded, a procedure that was completed by about midday.

During the two months that followed these initial landings, Harford’s Battalion suffered far heavier casualties in the Eski Line, where the battles to the south of Krithia (Alçitepe) took place. These culminated in the Battle of Gully Ravine (Ziğin Dere) (28 June–5 July), when the British finally captured all the south-western tip of Helles Burnu, including ‘Y’ Beach.

But on 8 June 1915, i.e. two days after the end of the Third Battle of Krithia, Harford was transferred from the South Wales Borderers to the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers (The London Regiment), another Regular battalion, and the one in which Romanes had been serving when he was mortally wounded two days earlier. In August 1914, the Battalion had been stationed in India and it arrived back in England in mid-January 1915, where it was initially sent to Stockingford, near Nuneaton, as part of 86th Brigade, also in the 29th Division. After two months near Coventry, this Battalion, consisting of 27 officers and 962 other ranks (ORs), had also sailed from Avonmouth for Gallipoli in the SS Alaunia. They arrived on Lemnos on 11 April, where they practised rowing and getting in and out of small boats in Mudros Harbour.

Allied troops practising landing drills in Mudros harbour, the island of Lemnos (1915) ; string of seven cutters is being pulled by a small trawler.

On 25 April, ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies of the 2nd Battalion, plus the machine-gun section, arrived off ‘X’ Beach. This beach was on the western side of the Gallipoli Peninsula and about three miles south-west of ‘Y’ Beach; it was also to the north-west of ‘S’ Beach, but on the opposite side of the Peninsula. It was, however, defended by a mere 12 Turkish soldiers – who ran away once the naval shelling began. So the Fusilier Battalion’s first two Companies took ‘X’ beach without loss by 06.30 hours and then advanced up Hill 114, supported by ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Companies with additional ammunition and entrenching tools, and took that by 11.00 hours. They also occupied the Turkish trenches on the left with little opposition, but when they tried to capture their heavily defended second line of trenches, they suffered heavy casualties and were forced to retire. During the night of 25/26th April, the Turks counter-attacked on several occasions and were driven off, and although the 2nd Fusilier Battalion successfully repulsed another counter-attack at 14.00 hours on 26 April, it was in action all day on 27 and 28 April, i.e. the first two days of the First Battle of Krithia, reduced to half its strength, and forced to withdraw to the Brigade Reserve Line. At 10.30 hours on 1 May, the Fusiliers were attacked by 18,000 Turks, and although the Battalion killed c.2,000 of their opponents during fierce hand-to-hand fighting, its own strength was reduced to 6 officers and 425 ORs, a total that went down to 5 officers and 384 ORs after the Second Battle of Krithia (4–8 May) and to 2 officers and 278 ORs – the equivalent of two companies – after the Third Battle of Krithia (4–6 June). Between 10 and 17 May the Battalion was out of line, resting, but having returned to the front line, it was involved in an assault on the enemy trenches on 22 May that cost it 40 casualties.

So pending officer reinforcements, Harford was transferred to the 2nd Battalion of the Fusiliers a day after it had been sent down to Gully Beach, on the north-western side of the southern tip of the Helles Peninsula, in order to rest and refit. From 13 to 17 June, the Fusiliers’ 2nd Battalion, now numbering 13 officers and 307 ORs, went back to the trenches at Geoghan’s Bluff, and when it relieved the 1st Battalion of the KOSB in the firing line again on 23 June, it had increased its strength to 17 officers and 662 ORs. The Battalion was in the trenches from 23 to 28 June, the first day of the Battle of Gully Ravine, when the Allied ships out at sea started to bombard the Turkish trenches very heavily indeed. At 11.30 hours, the 2nd Battalion began to advance from Geoghan’s Bluff, and according to the Battalion War Diary the attack was successful and the position consolidated by hand-to-hand fighting. But the Diary then adds that during the engagement of 28 June the Turkish artillery had been deployed very effectively and was responsible for most of the Fusiliers’ casualties on that day, which it put at 3 officers and 27 ORs killed in action, 3 officers and 175 ORs wounded, and 3 officers and 57 ORs missing. Harford was one of the wounded officers, having been hit in the chest by a bullet that had lodged below the right shoulder blade and against the ribs, and on 9 July 1915 he was sent to the 19th General Hospital in Alexandria, where he arrived on about 13 July 1915. On 2 August he left Alexandria on the 6,763-ton, 520-bed hospital ship, HMHS Glengorm Castle, and 13 days later he arrived in Southampton.

From Southampton he was taken to London in order to be admitted to the Harold Fink Memorial Hospital at 17 Park Lane, one of the 352 auxiliary hospitals in the London District that had been established by the far-sightedness of Sir Charles Keogh (1857–1936). It was here that the foreign body was extracted, and during his time here, on 23 August 1915, Harford was formally attached to the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers. On 10 October 1915 he was promoted Lieutenant. Although Harford was keen to rejoin a unit that was on active duty, he was also suffering from loss of weight, pleurisy and “haemothorax of the right side”, and on 1 September 1915 a War Office Medical Board at Caxton Hall categorized his wound as “very severe” and decided that even though no injury to the lung could be detected, Harford would not be fully fit for another five months. Nevertheless, on 20 November 1915 another Medical Board reduced that period to three months and in the end, probably because there was a shortage of good officers, he was released for duty on 7 December 1915.

Despite the above formalities, on 8 December 1915 Harford reported for duty with the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the South Wales Borderers at Hightown, Lancashire, possibly because by this time he was actively seeking a Regular Commission in the Regiment’s 1st Battalion, the unit in which, according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website and other records, he was serving at the time of his death. However, it was with the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, not the 1st (Regular Battalion), that Harford reported for duty on 13 May 1916 when it was in Corps Reserve at Englebelmer, five miles north of Albert. The 2nd Battalion had arrived in Marseilles from Suez on 18 March 1916, when it was still part of the 87th Brigade in the 29th Division, and it trained at Domart-en-Ponthieu until the end of that month. After a series of strenuous route marches it had finally reached Louvencourt, in the area of the Somme, on 12 April 1916.

At Englebelmer, from 19 to 28 May, the Battalion trained in the use of hand grenades and smoke bombs, firing a Lewis Gun, signalling, bayonet fighting, wire-cutting and contacting reconnaissance aircraft from the ground. Then, on 28 May, it moved into a new firing line between Beaumont Hamel and Auchonvillers and spent its time there wiring and building new communication trenches in the teeth of heavy rain. From 6 to 16 June, the Battalion was back at Louvencourt, using every available man for fatigue duties and practising attacks on German trenches in very bad weather conditions. On 23 June, the Battalion returned to the trenches to the left of 36th Division, and on 26 June the rain fell so heavily that the trenches “rapidly became full of water”. Indeed, by 29 June, the trenches were in such a bad condition that during the daytime, most of the men had to be kept in deep dug-outs in the old line. But the Battalion was now well-supplied with four Lewis Guns and eight Vickers machine-guns, and these kept up a continuous fire on the enemy trenches in order to prevent the Germans from mending their wire before the coming attack.

On 1 July 1916, the attack by 29th Division on Beaumont Hamel was preceded by the explosion of a huge mine, consisting of 40,000 lbs of ammonal. Half a Company of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (86th Brigade) then rushed to occupy the crater, armed with four Stokes Mortars and four machine-guns, but made no further progress because of machine-gun fire, and the same fate awaited the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers (87th Brigade), who were situated on the Fusiliers’ left. According to the Battalion War Diary:

By about 07.30 [hours] the leading companies [of the SWB] (‘A’, ‘C’, ‘D’) had lost nearly all officers and about 70% of the men. ‘A’ Coy [on the left] reached a point about 20 yds from [the] E[nem]y’s front line just to the south of the nose of the [Beaumont] salient where they were held up by m[achine-]g[un] fire and bombs from the trench. ‘C’ Coy [in the centre] crossed the hollow by sunken road and reached a point about 60 yards from [the] E[nem]y’s wire where they were under m[achine-]g[un] fire from their right flank. ‘D’ Coy [on the right] reached a point about 300 yards from our wire.

Reserve ‘B’ Coy left the support trench at 07.30 hours, came under machine-gun fire while passing through the British wire, and “advanced steadily across the open till practically all men were hit”. According to the Battalion War Diary, no-one “reached the Enemy’s trench and it was impossible to bring the bodies in: practically all those reported missing were probably killed”. As Harford’s name does not appear in the list of 15 officers and 384 ORs killed, wounded or missing, he was either very lucky, or, more probably, one of the 10% of the officers and men who had been left behind at Englebelmer as a reserve and who moved up to the front line at 09.30 hours.

Despite the awful toll, the remnants of the Battalion were moved into the front line on 2 July, where they remained until 8 July repairing the trenches and digging graves for the dead. On 8 July the depleted Battalion, now numbering 15 officers and 217 ORs, were moved back to Acheux in divisional reserve. They stayed here until 17 July, but then returned to the front line until 22 July, when they were moved back into Brigade Reserve in Mailly Wood. Two days later the entire 29th Division were withdrawn over three days to the town of Doullens, well to the west of the front line, whence they entrained for the Ypres Salient. After their arrival, they stayed near Poperinghe until 30 July, re-forming and training the new men. So, by 31 July, when the Battalion moved to the trenches on the Canal Bank near Wieltje, north of Ypres, its strength had built up to 34 officers and 519 ORs. The Battalion War Diary commented on these new trenches as follows:

Most of [them] are in very bad repair, and consist of a breastwork in front and a built-up parados behind, as it is impossible, owing to water being very near the surface, to dig deeper than two feet. Parts of the front trench are not continuous, and it is nearly impossible to go round the whole trench system by day. There is only a communication trench which is practicable.

On 3 August the War Diary added that the “amount of work to be done is limitless”. Luckily, the sector was relatively quiet – apart from machine-gun fire by night, artillery fire by day, and the occasional gas alert – and the Battalion was able to work intensively on the trenches even though there was “very little apparent result to show for it” and even though “any piece of trench which has not been thoroughly revetted at once commences to fall in and has to be re-dug”.

The Battalion stayed in the Ypres Salient until 7 October 1916, when it entrained for the Somme front, arriving at Cardonnette, north-east of Amiens, on 10 October. It then marched to Buire on the River Ancre on 13 October and finally arrived at a crowded and dirty camp south-west of Fricourt. Here, it practised attacking in wet and cold weather conditions until 19 October, when it was guided “along a track that was very deep mud” to the trenches south-west of Gueudecourt, taking casualties as it went. Moreover, because the men arrived at the trenches soaking wet and without any chance of getting dry, many of them developed trench feet. So during the Battalion’s two days in the front line (21–22 October), 3 officers and 20 ORs were killed in action, 7 officers and 58 ORs were wounded, 45 ORs were reported missing, and 4 officers and 64 ORs were admitted to hospital with trench feet. On 23 October, when the Battalion was in the support trenches 600 yards south-west of Gueudecourt, another 75 ORs were hospitalized with trench feet; on 24 and 25 October, partly because of the incessant rain, the same thing happened to a further 43 ORs, bringing the effective strength of the Battalion down to 19 officers and 393 ORs.

The Battalion was still in the same trenches on 26 October 1916, when its War Diary recorded: “In the early morning a patrol under Lieut[enant] J.H. Harford went out to discover if the enemy had any wire cut on our front. The patrol was unfortunately caught by the enemy’s fire and Lieut[enant] Harford was killed.” According to another report, Harford was lying in a shell-hole, trying to find enemy wire, when Very Lights betrayed his position to a German sniper and he was killed in action, aged 20. He has no known grave. He is commemorated on Pier and Face 4A of the Thiepval Memorial. He left £87 9s. 8d. His Chaplain wrote: “He went to his death like a gallant gentleman.”

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Frances Baroness Bunsen, A Memoir of Baron Bunsen: Late Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary of His Majesty Frederic William IV at the Court of St. James (London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1868). Also available online at http://books.google.com/.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant John Henry Harford’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,330 (21 November 1916), p. 4.

Harrow Memorials, iv (1919), unpaginated.

O’Neill (1922), p. 100.

Gillon (1930), pp. 123–59.

[Anon.], ‘Major Sir John Harford’ [obituary], The Times, no. 46,808 (17 July 1934), p. 9.

Wilkinson-Latham (1975), pp. 27–29.

[Anon.], ‘Mr Charles Hill: Leading figure in shipping’, The Times, no. 59,889 (17 December 1976), p. 20.

Westlake (1996), pp. 22–6.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 28–9.

Rodge (2003), passim, but especially pp. 43–59, 64–76, 167–84.

N.D. Daglish, ‘Raikes, Henry Cecil (1838–1891)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 45 (2004), pp. 800–02.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

WO95/1280.

WO95/2304.

WO95/4310.

WO95/4311.

WO339/25521.