Fact file:

Matriculated: 1906

Born: 3 September 1887

Died: 10 August 1915

Regiment: Welsh Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Helles Memorial: Panels 140–144

Family background

b. 3 September 1887 at Glan Merthyr, Glamorgan, as the third son and seventh child (of nine children) of William Evans JP, M.Inst.CE (1844–1915) and Elizabeth Evans (neé Evans) (1853–1920) (m. c.1876). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living in Llwyncelin House, Merthyr Tydfil (two servants) and was still living there in 1894. When William Evans returned to Wales to work after a spell in Stockton, he and his family lived at Brynteg, Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorgan, and were still living at this address at the time of the 1911 Census (three servants).

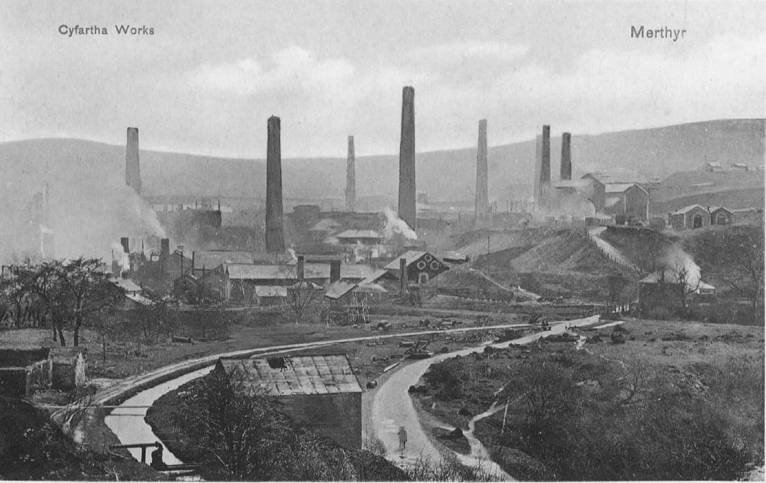

William Evans entered the Dowlais Iron Works at an early age as an office boy, but being both intelligent and observant, he gradually rose to the position of Furnace Manager. In 1876 he was appointed General Manager of the Dowlais and Cyfarthfa Steelworks; in the 1881 Census he described himself as “Bessemer Steel Works Manager”; in the 1891 Census he described himself as “Manager of Iron Works”; a few years later he moved to a similar appointment in Stockton; and in 1911 he described himself as “Manager of Iron, Steel and Coal Works”. When the Cyfarthfa Works were reconstructed and adapted for steel manufacture, Evans returned to Wales to take charge of them, and when Messrs Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds acquired the controlling interests in the Dowlais and Cyfarthfa Works in 1902, he was appointed General Manager of the combined undertaking. He was a Justice of the Peace for three counties – Glamorgan, Brecknock and Monmouth – but his time was primarily devoted to the management of the industries under his care. He became a Mason on 4 May 1876, and although he was not able to attend the Lodge meetings for some years, he still took an interest in Masonry and contributed towards the Charities. On the occasion of the Centenary Celebration of his Lodge, he contributed a handsome sum towards the building fund. He left £42,899 13s. 5d.

Evans’s mother was the daughter of John Evans, a carpenter in Beaufort, Monmouthshire. At the time of the 1871 Census she was a pupil teacher. On her death she left £2,794 17s. 7d.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) John (c.1877–1914); married (1902) Mabel Hannah Davies (1876–1862); three children;

(2) William (“Willie”) (1879–1905, died of pneumonia);

(3) Margaret Amy (1881–1942); later Jones after her marriage in 1916 to Thomas Faenor Jones (1867–1955);

(4) Edith Mary (1882–1959); later Rees after her marriage in 1912 to William John Dan Rees (1874–1934); one son, one daughter;

(5) Sarah Elizabeth (b. 1884, d. after 22 March 1955);

(6) Martha (“Mattie”) (1886–1961); later Thomas after her marriage in 1918 to David Rowland Thomas (1881–1955; later KC/QC); one daughter;

(7) Richard Stanley (1892–1915); killed in action, aged 23, in the same place and on the same day as his elder brother while serving as a Lieutenant in the same Battalion of the Welsh Regiment;

(8) Gertrude Elizabeth (b. c.1905).

John was educated at Shrewsbury School, after which he became an apprentice at the Cyfarthfa works, eventually becoming Furnace Manager and later Manager of the Dowlais works. He suffered from ill health and some time before his death he spent time in Egypt seeking a cure.

Thomas Faenor Jones was the brother of Howel R. Jones, who, by mid-1916, had become the General Manager of the Dowlais and Cyfarthfa Works and Collieries. Thomas Faenor received his early training in Dowlais, and for some years occupied the position of the steelworks’ Manager under Messrs Crawshay Brothers, Cyfarthfa Works, and subsequently that of Works Manager to the Glasgow Iron and Steel Company at Wishaw, North Lanarkshire. He gave up this appointment in about May 1915 to fill a similar appointment in South Wales.

William John Dan Rees was the son of a land and estate agent and described himself as a clerk. He left £197.

David Rowland Thomas was the son of a Welsh nonconformist deacon and began his working life as a clerk in Cardiff Post Office. He then went to London where he worked for a time as a journalist but also studied Law, and he was called to the Bar by the Middle Temple on 23 June 1909. He became a barrister for the South Wales and Chester Division, part of the Wales and Chester Circuit, took silk in 1931 and was made Recorder of Carmarthen in 1935 and a Master of the Bench of the Middle Temple in 1937. From 1941 to 1954, he was a Metropolitan Police Magistrate; he died while on a sea voyage a year after his retirement from that position. When he retired, the regular spectators at Marlborough Street Court wrote him a letter in which they expressed their admiration of the way in which he had performed his duties: “In the administration of justice, it is our mature and unanimous opinion that you brought to the difficult task a human, humane, and (on suitable occasions) humorous outlook such as is all too rarely to be found in magisterial courts.”

Richard Stanley was educated at Mill Mead Preparatory School, Shrewsbury, from c.1899 to 1905 and Shrewsbury School from 1905 to 1911, when he passed Responsions in the Hilary Term and matriculated at Hertford College, Oxford, in October. He passed the first Public Examination in Hilary Term 1912 (Classical texts [Greek and Latin]) and Trinity Term 1913 (Scripture); and was awarded a 4th in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1914 – though he never took his BA, presumably because he had already joined up. He was commemorated on a memorial plaque in Mill Mead Preparatory School and when the School was closed in 1966, the plaque was transferred to St Giles’ Church, Shrewsbury.

Education

Evans attended Mill Mead Preparatory School, Shrewsbury, from c.1894 to 1901 and Shrewsbury School from 1901 to 1906 (cf. E.H.L. Southwell). He then matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 16 October 1906, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1906. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1907 and was awarded a 2nd in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1909. He took his BA on 7 October 1909. From October 1908 he seems to have made his career in the Army, but at the time of the 1911 Census he was at the Crown Hotel, Shrewsbury, giving his profession as law student.

War service

Tudor Evans was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 1/5th Battalion (Territorial Force), the Welsh Regiment, in 1908 (London Gazette, no. 28,186, 16 October 1908, p. 7,477), and promoted Lieutenant in 1911 (LG, no. 28,476, 17 March 1911, p. 2,237), and Captain on 7 July 1914 (LG, no. 28,847, 7 July 1914, p. 5,283). On 28 August 1914 he became a Staff Captain (LG, no. 28,885, 31 August 1914, p. 6,889) but was allowed to give up that appointment on 9 January 1915 in order to rejoin the fighting Battalions of his Regiment. The Battalion mobilized at Pontypridd when war broke out, trained nearby until 22 August 1914, travelled by train to Conway on 30 August, and then trained for nearly a year – near Northampton; at Tuddenham, Norfolk; at Otley, West Yorkshire; at Little Stonham, near Stowmarket, Suffolk; and near Cambridge, Royston and Bedford. On 17 April 1915 the Battalion became part of the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade in the 53rd (Welsh) Division (Territorial Force), commanded by Major-General the Hon. John Lindley (1863–1931).

But when, on 19 July 1915, the 53rd Division travelled to Devonport in order to embark for Gallipoli as part of the recently formed IX Corps, it had seen no real action, had no Signal Company and only one field ambulance, and had to leave its artillery in England because of the logistical difficulties of carrying the right kind of ordnance to Gallipoli and unloading them and the horses and equipment. Shortage of the right kind of guns – field guns and howitzers – and lack of ammunition would become a major problem for the British in the mountainous landscape of the peninsula. Nevertheless, as a member of one of the two Territorial Divisions in IX Corps, the Battalions of the 53rd Division were more experienced than the three untried New Army Divisions which formed the rest of the new Corps, and to make things worse, the command of IX Corps had been given to the elderly, inexperienced, and over-cautious Lieutenant-General Frederick William Stopford (1854–1929), who had retired in 1909 without ever commanding men in battle.

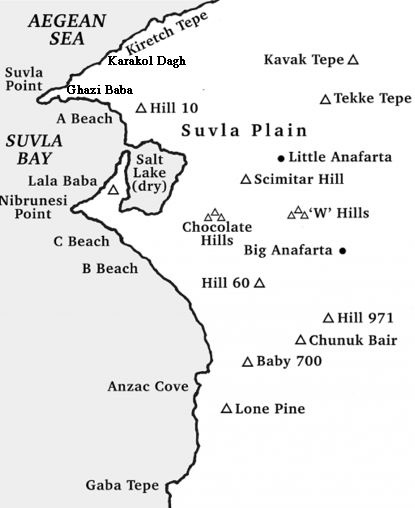

The aim of the whole operation, which had been planned in 10, Downing Street, London, by Lord Kitchener’s Dardanelles Committee as recently as June–July 1915, was to break the costly stalemate in the centre of the western sector of the peninsula, where British and Dominion troops were still pinned down on or in the cliffs above a narrow and overcrowded strip of beach at Anzac Cove. This was to be achieved by landing IX Corps at three points on Suvla Bay, 6–10 miles north of Anzac Cove, during a moonless period: on Beach ‘A’ (the whole of Suvla Bay) and Beaches ‘C’ and ‘B’ (further to the south and below Niebruniessi Point). But these landings would be synchronized with (1) the combined British–ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) attack on the Sari Bair heights (see E.C. Willoughby) and (2) a diversionary assault on uncaptured Krithia, in the south of the isthmus (see E.T. Young), by elements of the 29th and 42nd (East Lancashire) Divisions. Four Brigades from two Divisions of IX Corps would begin the three-pronged assault by landing in absolute silence at 22.00 hours on 6 August 1915 at the two ends of Suvla Bay.

At the northern end, two of the four New Army Battalions – the 9th (Service) Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers and the 11th (Service) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment – both members of 34th Brigade (11th (Northern) Division), would, by 01.00 hours on 7 August, take Hill 10, a vantage point no more than about ten feet above sea level at its highest point, with a small Turkish garrison in the centre of the bay between the dried up Salt Lake and the sea. This would then allow the 11th Battalion to swing up leftwards towards the southern end of the ridge known as Kiretch Tepe that ran parallel to the Gulf of Saros. The 11th Battalion would then advance along the ridge for two miles before digging in, and then wait for reinforcements who would continue the advance along the ridge, through the hills, and across Suvla Plain, and take the high point known as Tekke Tepe ridge (c.800 feet high). In the south, the 32nd and 33rd Brigades (also 11th (Northern) Division) were to land on the northern and southern ends of ‘B’ Beach respectively, and take Lala Baba, a low hill (c.150 feet high), that was garrisoned by a small number of Turks and situated just to the north-east of Niebruniessi Point and just to the west of the Salt Lake.

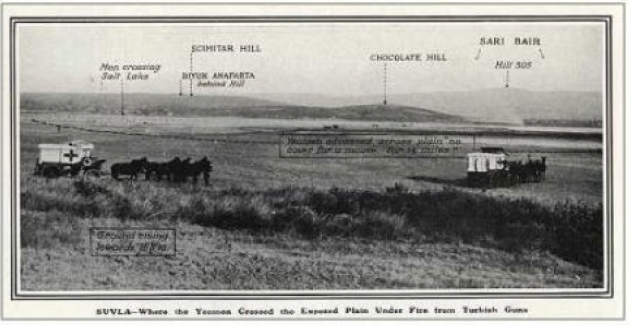

32nd Brigade would then swing north and link up with 34th Brigade on Hill 10, and the combined force would then advance inland for two or three miles in order, by 01.30 hours on 7 August, to take the well-protected Turkish strong-point on Yilghin Burnu, the adjoining Green and Chocolate Hills that rose up from the eastern side of the dried up Salt Lake and derive their names from their respective colours. Throughout this entire night action, silence and speed were to be essential, as the Turks had positioned eight mountain guns and four field guns on the high ground that overlooked and therefore commanded the Anafarta Plain. The initial pincer movement, combined with the rapid thrust eastwards, would, it was hoped, allow the rest of IX Corps to land without difficulty at Suvla Bay, establish a supply port, and open up a gateway into the ring of hills surrounding Anarfarta Plain through which the invading troops could advance and link up with the force that was assaulting Sari Bair, a mountain ridge “not half a dozen miles to the south-east” that can be seen in the background of the photo below.

The Anafarta Plain, looking north-eastwards across Anafarta Plain and the Salt Lake from a position inland, probably in the foothills of Kiretch Tepe (1915).

At the southern end of the invasion the landings went reasonably well at first and Lala Baba was soon taken as planned, although the cost in casualties was heavy, especially among the officers. For instance, the 6th (Service) Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment, part of 32nd Brigade, lost all but three of its officers, including its Commanding Officer (CO). But then as two of the four Battalions comprising 34th Brigade – the 5th (Service) Battalion of the Dorsetshire Regiment and the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers – arrived very late on the peninsula, the planned night-time link-up on Hill 10 was delayed by several hours, and the advance northwards to Kiretch Tepe was delayed even longer, until about 07.00 hours on 7 August, by which time, of course, dawn had broken.

At the northern end of the invasion, things started less well. The two leading Battalions of 34th Brigade – the 9th (Service) Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers and the 11th (Service) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment – were landed on the wrong parts of the beach. This caused confusion and delay, and when the 9th (Service) Battalion first tried to take Hill 10, it attacked a sand dune instead and would not take the correct hillock until 07.00 hours on 7 August, by which time it had lost 14 of its officers killed, wounded or missing, including its CO, and the few defending Turks had quietly pulled out eastwards. Only then was the 11th Battalion of the Manchester Regiment free to swing northwards as planned, get onto Kiretch Tepe ridge and reach the high point known as Karakol Dagh – which it took by noon despite the difficult terrain, acute thirst and exhaustion because of the intense summer heat. Having advanced a total of three miles, the 11th Battalion held this position until 21.00 hours, when it was relieved by elements of the 10th (Irish) Division, but the action had cost it 15 officers and 200 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing.

By dawn at about 06.00 hours on 7 August, the overall situation had not greatly improved: elements of 32nd Brigade had become mixed up with 34th Brigade, several Battalions from the 11th Division were still waiting for precise orders, the 31st Brigade, part of the 10th Division, had been landed without proper maps on ‘C’ Beach because ‘A’ Beach had earlier proved to be too deep for the invading troops, hostile artillery fire was causing annoyance all along the line, and a serious water shortage was starting to develop. But, most importantly, although the relatively small number of Turks on Suvla Bay – about 1,500 men in various places under the command of Major Wilhelm Willmer, a Bavarian cavalry officer – were slowly retiring eastwards, the British troops were not pursuing them, even though reliable intelligence from several sources had correctly diagnosed the situation and even though the spirit, if not the letter, of General Stopford’s orders, “enjoined an extreme activity”. For most of 7 August, this lack of absolutely clear directions from the General Officer Commanding (GOC) IX Corps was causing considerable disagreement among the various Brigade commanders about what they should now do. Finally at 15.00 hours, a group of Battalions under Brigadier Felix Frederic Hill, DSO (1860–1940), the GOC 34th Brigade, began an advance from Hill 10, accompanied by elements of another two Brigades from points between Hill 10 and the Salt Lake, towards Yilghin Burnu (Chocolate Hills), and captured the two adjoining hills at about 19.00 hours despite an unnecessarily long march route, shelling, snipers, a difficult terrain, and the inevitable thirst and exhaustion. Nevertheless, an informed professional commentator later wrote that:

[the] outsider will find it hard to escape from the broad general conclusion that amongst the commanders, the staff and the regimental officers concerned in the landing […] the vital importance of a very early advance, and therefore of the initiation of vertebrate offensive action at the first possible moment, was not sufficiently recognised.

He went on to say, more specifically, that the secrecy surrounding the operation meant that when the “regimental officers and troops” of the 11th Division, consisting of the 32nd, 33rd and 34th Brigades, “set foot on shore”, they had “no definite conception of what they were about to do, or of what they were being called upon to face”. Moreover, even when elements of 31st and 33rd Brigades had taken the two high points of Yilghin Burnu, the British troops did not press on further into the higher ground beyond and were either withdrawn from Yilghin Burnu and the nearby curving ridge known as Scimitar Hill (Yusufçuk Tepe = Dragonfly Ridge; see the photo above) to the foot of the Hill, or even recalled to Suvla Beach.

Within the first 24 hours of the invasion, IX Corps lost c.1,700 of its inexperienced troops killed, wounded or missing. Moreover, the general state of confusion, combined with extreme tiredness, thirst, and bad decisions on the part of poorly informed and indecisively led Brigadiers, brought about a widespread inertia that caused 8 August 1915 to become a day of inaction and rest for the exhausted British soldiers. And although this situation gave General Stopford, whose headquarters was now near Ghazi Baba at the very northern horn of ‘A’ Beach, time to consolidate his beachhead by ordering the 31st and 32nd Brigades to move forward and form a line between Kiretch Tepe and Yilghin Burnu, it effectively put an end to the advance along Kiretch Tepe towards the ridge at Tekke Tepe and fatally delayed the infestation of the all-important high ground above Yilghin Burnu. So it was not until 04.00 hours on 9 August, following the personal intervention at about 17.00 hours on the previous evening by Sir Ian Hamilton (1853–1947), the Commander-in-Chief of the whole Gallipoli enterprise, that the four Battalions of the 32nd Brigade, which were believed to be more concentrated than those of the other Brigades, began a badly coordinated two-mile long advance on Tekke Tepe with orders to gain a foothold on the high ground to the north of Suvla Plain. But lack of initiative and the day’s delay had given the Turks the time to rush reinforcements from the town of Bolayir, c.33 miles away on the neck of the Gallipoli isthmus, into the hills surrounding Suvla Bay. So when the 6th (Service) Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment (32nd Brigade) reached Tekke Tepe in advance of the other three Battalions and began the assault on the ridge in earnest, it was on its own and almost immediately encountered stiff resistance from fresh Turkish troops of the 12th Division that were led by General Mustafa Kemel (1881–1938; from 1934 Atatürk = “Father of the People”). Consequently, it lost 15 officers and 300 ORs killed, wounded or missing within 30 minutes, gave way, and so compromised the troops on its right. The Turkish defence soon turned into fierce counter-attacks in which W Hill (Ismail Oglu Tepe) and Scimitar Hill were recaptured and two of the other three Battalions of 32nd Brigade were decimated. Other attempts on 9 August to retake the lost high ground east of Suvla Bay on IX Corps’s southern flank proved costly failures, whilst on Kiretch Tepe in the north of Suvla Bay, intense heat, the lack of water, and the absence of adequate artillery support prevented the untried New Army Battalions from making any real progress.

Within the first 24 hours of the invasion, IX Corps lost c.1,700 of its inexperienced troops killed, wounded or missing. Moreover, the general state of confusion, combined with extreme tiredness, thirst, and bad decisions on the part of poorly informed and indecisively led Brigadiers, brought about a widespread inertia that caused 8 August 1915 to become a day of inaction and rest for the exhausted British soldiers. And although this situation gave General Stopford, whose headquarters was now near Ghazi Baba at the very northern horn of ‘A’ Beach, time to consolidate his beachhead by ordering the 31st and 32nd Brigades to move forward and form a line between Kiretch Tepe and Yilghin Burnu, it effectively put an end to the advance along Kiretch Tepe towards the ridge at Tekke Tepe and fatally delayed the infestation of the all-important high ground above Yilghin Burnu. So it was not until 04.00 hours on 9 August, following the personal intervention at about 17.00 hours on the previous evening by Sir Ian Hamilton (1853–1947), the Commander-in-Chief of the whole Gallipoli enterprise, that the four Battalions of the 32nd Brigade, which were believed to be more concentrated than those of the other Brigades, began a badly coordinated two-mile long advance on Tekke Tepe with orders to gain a foothold on the high ground to the north of Suvla Plain. But lack of initiative and the day’s delay had given the Turks the time to rush reinforcements from the town of Bolayir, c.33 miles away on the neck of the Gallipoli isthmus, into the hills surrounding Suvla Bay. So when the 6th (Service) Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment (32nd Brigade) reached Tekke Tepe in advance of the other three Battalions and began the assault on the ridge in earnest, it was on its own and almost immediately encountered stiff resistance from fresh Turkish troops of the 12th Division that were led by General Mustafa Kemel (1881–1938; from 1934 Atatürk = “Father of the People”). Consequently, it lost 15 officers and 300 ORs killed, wounded or missing within 30 minutes, gave way, and so compromised the troops on its right. The Turkish defence soon turned into fierce counter-attacks in which W Hill (Ismail Oglu Tepe) and Scimitar Hill were recaptured and two of the other three Battalions of 32nd Brigade were decimated. Other attempts on 9 August to retake the lost high ground east of Suvla Bay on IX Corps’s southern flank proved costly failures, whilst on Kiretch Tepe in the north of Suvla Bay, intense heat, the lack of water, and the absence of adequate artillery support prevented the untried New Army Battalions from making any real progress.

RMS Caledonia (1904; torpedoed 125 miles east of Malta by UB65 on 4 December 1916 while en route from Salonika to Marseilles with the loss of one life).

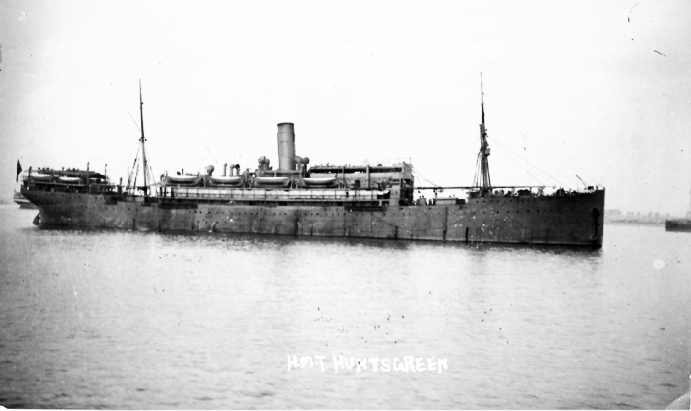

SS Huntsgreen (1907 as the German merchantman Derflinger; captured at Port Said 1914 and renamed; scrapped 1932 after being sold back to the Germans)

On Lemnos the 1/5th Battalion, consisting of 28 officers and 811 ORs, underwent preparatory training for the task ahead of them, whose relevance and usefulness would later be questioned. On 8 August, the 1/5th Battalion transferred to HMS Rowan, a merchantman that had been converted into an armed boarding steamer, and, together with the rest of the 53rd Division, landed on ‘C’ Beach, Suvla Bay, on 9 August. But instead of being directed immediately towards Chocolate and Green Hills, they bivouacked overnight at Lala Baba.

HMS Rowan (1909; sank off Corsewall Point, near Stranraer, on 8 October 1920, after colliding with another ship in thick fog with the loss of 36 lives) (Photo courtesy of Caledonian Maritime Research Trust)

On 10 August 1915 the attack on the high ground to the east of Suvla Plain was repeated and 158th Brigade was ordered to start the day by acting as the Reserve for Tudor Evans’s 159th Brigade during the first phase of a combined assault on Scimitar Hill. 159th Brigade was to lead the advance, and 158th Brigade was to go through the 159th Brigade once a certain point had been reached in order to become the leading Brigade. At first the attack was unopposed, but at 04.45 hours, while the Welsh battalions were crossing the dried-up Salt Lake, the Turks opened up with shrapnel, causing casualties. The formations opened out about 200 yards beyond the Salt Lake, but then came under rifle fire, and when 158th Brigade caught up with 159th Brigade in order to leap-frog, it found that the men of 159th Brigade were mainly entrenched or taking cover under ledges. But the advance continued, and when the Welsh battalions opened fire at c.11.30 hours, they were about 200 yards from the Turkish positions. They then assaulted those positions and the enemy withdrew, but when the Welshmen reached the top of Scimitar Hill the Turks enfiladed them with machine-gun fire and shrapnel. So, “suffering severely”, the 158th Brigade was forced to pull back to the line held by the 159th Brigade, having lost 168 ORs and 12 officers killed, wounded or missing, two of whom must have been Rees Tudor Evans, aged 26, and his brother Richard Stanley Evans, aged 23. The casualties in 159th Brigade were so high that day that after the battle the 1/4th and 1/5th Battalions were amalgamated to form the 4th Welsh Composite Battalion, which remained in existence until 10 February 1916.

Rees Tudor Evans was later presumed to have died of wounds received in action and on 6 August 1917, Evans’s father wrote a letter to President Warren in which he said:

Several of the men from the 1/5th state that Capt. Evans was shot through the right wrist, he would not give in, and was afterwards shot in the side, but would not allow his men to carry him back to a dressing station, telling them to leave him and look after other wounded men.

Later on Major H.M. Davies wrote:

It was a brave advance – but with little if any chance of success as there was no arrangement of artillery support, nor coordination with flanking units. One seemed to have been wedged in somewhere in the blue. In view of experience gained later one felt that had there been some sort of co-operation from the R.A. – that regimental officers had the power to call for or arrange for [the] support of the R.A. – greater confidence would have been inspired in all ranks. I feel that the Brigade Commander knew little of what was going on and that Regimental officers – particularly platoon leaders – know [sic] less. Further – one often wondered whether the training received prior to embarkation was of the right sort – that undoubtedly is where much of the fault lay, but perhaps I am making this criticism on [sic] the light of subsequent experience.

Evans has no known grave. All three parts of the tripartite attempt to defeat the Turks on Gallipoli failed, and although the Battle of Suvla Bay dragged on until 21 August 1915 and cost the Turks more casualties than it did the British, it was they who won the decisive victory which, to all intents and purposes, put an end to active operations on the Gallipoli Peninsula five months before the Allies finally withdrew. General Hamilton, with Lord Kitchener’s approval, fired General Stopford on 15 August, followed a few days later by the GOCs of the 11th and 53rd Divisions, Major-General Frederick Hammersley (1858–1924) and Major General Lindley. Hamilton himself would be fired by the Gallipoli Committee in London on 14 October. The two Evans brothers are commemorated on Panels 140 to 144, Helles Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. Tudor Evans left £1,199 6s 9d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgement:

*Stephen Chambers, Suvla: August Offensive (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2011), esp. pp. 27–108.

Printed sources:

Letter in the South Wales Echo, 20 September 1915.

[Anon.], ‘Welsh Pioneer of Industry, Death of Mr William Evans of Cyfarthfa’ [obituary], Western Mail, no.14,269 (13 February 1915), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘New Recorder of Carmarthen’, The Times, no. 47,075 (28 May 1935), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘New London Magistrate’, The Times, no. 48,863 (1 March 1941), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Mr D. Rowland Thomas’ [obituary], The Times, no. 53,177 (28 February 1955), p. 11.

Westlake (1996), pp. 156–7.

Callwell (2005), pp. 182–98, 209–40.

Ford (2010), pp. 247–51.

Gariepy (2014), pp. 224–47.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/59.

WO95/4323.

WO374/23158.

On-line sources:

Gallipoli Association, ‘OoB – August Offensive: Order of Battle Mediterranean Expeditionary Force’: https://www.gallipoli-association.org/campaign/order-of-battle-mef/oob-august-offensive/ (accessed 17 April 2019).