Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born : 11 August 1884

Died: 5 May 1920

Regiment: Scots Guards

Grave/Memorial: St John the Baptist Churchyard, Rowlands Castle, Redhill, East Hampshire

Sir Frederick Loftus Francis Fitzwygram, 5th Baronet, MC, MA

(Photo courtesy of Lieutenant-Colonel C.J. Bell, OBE, CO of the 1st Battalion, the Scots Guards)

Family background

b. 11 August 1884 at The Lowlands, Farnham, Surrey (his mother’s sister’s house), as the only surviving son of Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Wellington John Fitzwygram, 4th Baronet of Walthamstow, MP, JP, FRCVS (1823–1904), of Leigh Park, Hampshire, and Lady Angela Mary Ada Louisa Fitzwygram (née Vaughan) (c.1845–1935) (m. 1882). At the time of the 1891 Census, 13 servants were living in at Leigh Park and at the time of the 1901 Census, the number had dropped to nine. But at the time of the 1911 Census the family were not in residence and only two servants had been left there. But Lady Angela and her daughter Angela Katherine were living at the family’s town house (20, Eaton Square, Belgravia, London SW1 – just to the south of Buckingham Palace) with ten servants.

Leigh Park House (c.1911): a watercolour by Angela Fitzwygram

(From The Last of the Line (p. 17) by kind permission of Steve Jones)

Parents and antecedents

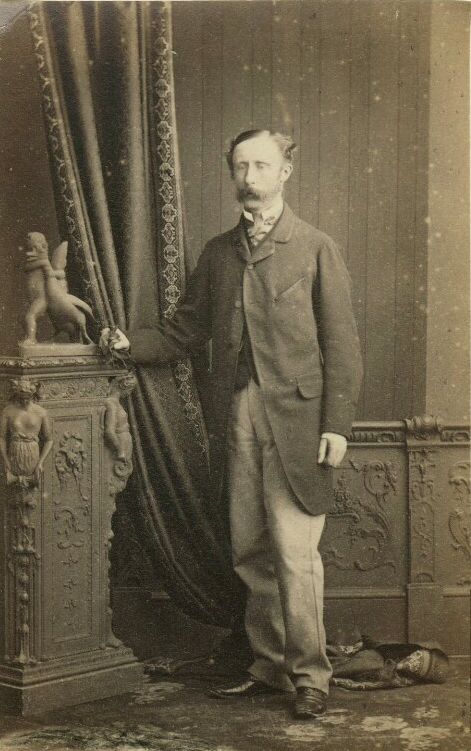

Sir Robert Wigram [I] (1744–1830), engraved by James Henry Watt (1799–1867) from a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Sir Robert Wigram [I] (1744–1830), who established the Wigram family’s considerable wealth, was born in Wexford, near Dublin, Ireland, as the son of a Bristol merchant. He qualified as a surgeon and sailed to India as a ship’s doctor, but due to ill health he became land-based. Nevertheless, he also became a very successful merchant, trader with India, and ship-builder. According to his obituary in the Annual Register he owned three ships and was “one of the greatest importers of drugs in England”. In due course he also became head of Reid’s Brewery (founded 1757; merged with Watney’s in 1898), Liquorpond Street (now Clerkenwell Road), London EC1; head of Huddart’s Rope Works, Limehouse, London E14; founder and chairman of the East India Docks (founded by Act of Parliament in 1803); and Principal of the nearby Blackwall shipbuilding yard, London E14. His status is indicated by the fact that he chaired a meeting of merchants and bankers during the troubled time of the French Revolution. A leading supporter of William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806; Prime Minister 1783–1801 and 1804–06), Sir Robert Wigram was the Tory MP for the rotten borough of Fowey, Cornwall, from 1802 to 1806 and for Wexford from 1806 to 1807, but he resigned from politics when the seat was abolished. In 1805 he became the first Baronet of Walthamstow, Essex, where he lived in Walthamstow House. He married twice: first Catherine Broadhurst (1750–1786) (m. 1772) and second Eleanor Watts (1767–1841) (m. 1787). He fathered 23 children, of whom at least 14 survived to adulthood: three with his first wife and eleven by his second. From 1812 to 1813 he served as the High Sheriff of Essex.

Sir Robert Wigram [I]’s eldest son, Sir Robert Wigram [II] (1773–1843), became the second Baronet, but changed his name to Robert Fitzwygram in 1832 by Royal Licence, a step which the Gentleman’s Magazine considered “a fanciful alteration, and […] not in good taste”. In 1812 he married Selina Hayes (1791–1866). He was particularly interested in promoting science and helped to found the London Institute (which opened in Old Jewry, London EC2, on 18 January 1806 and whose purpose was to make a scientific education more widely available in Britain’s capital city). Sir Robert Wigram [II] applied for election to a Fellowship of the Royal Society in late 1805: it was considered by several actual Fellows on 7 November 1805 and they granted his request on 27 February 1806 on the grounds that he was a “Gentleman conversant with several branches of science” and likely to become “an useful and valuable member” of the Society. He then followed his father by becoming the Tory MP for the rotten borough of Fowey, Cornwall, from 1806 to 1818. In 1829 and 1831 he was elected Tory MP for Wexford, but was, on both occasions, unseated by petition.

Robert Wigram [II]’s eldest son, Sir Robert Fitzwygram Wigram (1813–73), became the third Baronet, never married, and apart from saying that he graduated from Christ Church, Oxford, in 1834, none of his obituaries has anything to say about how he spent his life. But when he died, the baronetcy passed to his younger brother, Sir Frederick Wellington John Fitzwygram (1823–1904), the second son of Robert Wigram [II], whose baptismal sponsors (godfathers) were the Duke of Wellington (1769–1852) and Prince Frederick Augustus (1763–1827; the second son of George III, the Duke of York and Albany, and the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army from 1795 to 1809 and 1811 to 1827).

Frederick became a professional cavalry officer by purchasing a commission and then served in the British Army for 46 years – firstly, from 1843, when he was 20, in the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons (raised in 1689) and then, from 1860, in the 15th (The King’s) Hussars (raised in 1759). After leaving Eton, Sir Frederick was reported as saying that he had done so “without the slightest knowledge of any subject which had been the smallest use to him in afterlife”. Nevertheless, and unusually for the time, he qualified in Veterinary Science at the Dick (now the Royal) Veterinary School in Edinburgh in 1854. He then served in the Crimean War (1853–56), during which, in the context of the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–55), his Regiment distinguished itself on 25 October 1854 as part of the Charge of the Heavy Brigade, its one military action, but lost heavily through disease. He was present at the fall of Sevastopol in September 1855, for which he received the Crimean Medal with one clasp and a Turkish Decoration. In 1860 he transferred to the 15th Hussars as their Commanding Officer and served in Ireland and India, where he acquired a reputation for being “a staunch friend to Tommy Atkins”. It is related that “while serving in India he was so strongly impressed with the urgent need for summer quarters on the hills for wives and children, that he gave £10,000 [£431,000 in 2005] towards providing suitable dwellings”.

During the second part of Sir Frederick’s professional life, when his Regiment was not actively engaged in warfare, he gradually became prominent in the world of veterinary medicine by writing well-received books on the care and management of horses (e.g. Lectures on Horses and Stables (1862), Notes on Shoeing Horses (1862; 2nd edition 1863), Directions for Shoeing Horses with Ordinary Feet (1896), Horses and Stables (1869; 5th edition 1901)); and he finally became Vice-President of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (1872–75) and then its President (1875–79). Betty Marshall maintains that during his seven years of office in the RCVS, he “transformed the status and organisation of the veterinary profession” and “produced a unified profession with a recognised and respected qualification” (p. 18).

Sir Frederick Fitzwygram, 4th Baronet

(Photo by Southwell Brothers, albumen carte-de-visite (1860s) NPG Ax46341)

Sir Frederick returned to Britain from India soon after his brother’s death, and in 1874 he bought the c.2,500-acre Leigh Park Estate (now in part an overspill suburb of Portsmouth) together with its Gothic-style house. Sir George Thomas Staunton (1781–1859; Liberal MP for several constituencies in southern England from 1818 to 1852, including for Portsmouth 1838–52) had bought Leigh Park Estate in 1820, not long after his return from China, where he had been a diplomat and became a respected Sinologist. Sir George made several improvements to Leigh Park’s buildings and to the property in general, creating, inter alia, a gamekeeper’s cottage, a library to house his collection of Chinese books, the park and a wonderful Regency walled garden. But the original house was pulled down in 1864 and replaced by a Gothic-style house with 40 rooms (but only one bathroom) that was built by William Henry Stone (1834–96; Liberal MP for Portsmouth from 1865 to 1874) in the following year – when he took his seat in Parliament. Sir Frederick Fitzwygram then added to his predecessors’ improvements by installing glasshouses in Sir George’s walled garden so that fruit and vegetables could be more easily grown there, building lean-to greenhouses for the same purpose, and constructing a greenhouse solely for the purpose of growing cucumbers and melons.

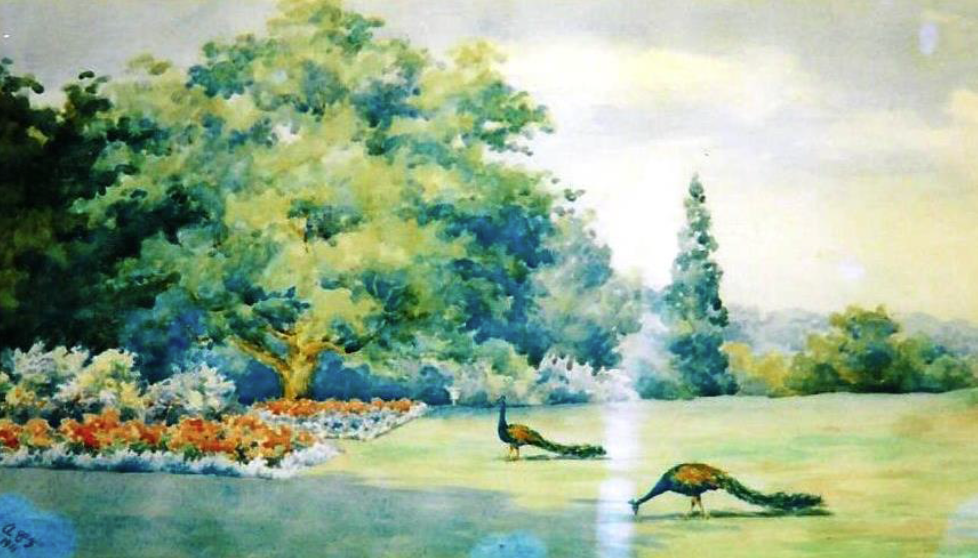

The gardens of Leigh Park House (c.1911), a watercolour by Angela Fitzwygram

(From The Last of the Line (p. 17) by kind permission of Steve Jones)

From 1879 to 1884, when he retired from the Army, Sir Frederick was GOC (General Officer Commanding) the Cavalry Brigade at Aldershot and Inspector-General of Cavalry, after which he became actively involved in politics. When Sir James Elphinstone (1805–86), a former naval commander who had been MP for Portsmouth from 1857 to 1865 and 1868 to 1880, retired from politics, the Conservative Party would have been glad to secure the services of Sir Frederick as his successor, but this was not possible as he was still a serving officer. In 1884, however, Lord Henry Scott (Lord Henry Montagu-Douglas-Scott; 1832–1905), who then became Lord Montague, retired as MP for Hampshire South because of ill-health, having held the seat for the Conservatives since 1868. Whereupon Sir Frederick was invited to stand as his successor, and having “entered the contest with all his characteristic energy”, was returned as the Conservative MP for Hampshire South with a substantial majority. And when this constituency was abolished in the following year, Sir Frederick successfully stood as the Conservative MP for Fareham and held this seat unopposed from 1885 to 1900 – when he retired from politics. His main parliamentary interests were military and agricultural. Sir Frederick was also a magistrate who sat on the Havant Bench and a Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire, and in 1901 he was made the Honorary Colonel of the 2nd Volunteer Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment (formed in 1859 with its headquarters in Portsmouth).

Sir Frederick was known as a strict but kindly disciplinarian; he had surprisingly advanced ideas about farming and took considerable interest in the management of Leigh Park Estate. He was greatly concerned for the wellbeing of his tenants, especially in their old age, and his lengthy obituary in the Portsmouth Evening News describes him as a “model landlord” who,

in his early days at Leigh Park […] took in hand the provision of better dwellings for the employees of the estate, and numerous pretty cottages testified to the kindly interest he had always taken in the welfare of the many workmen who lived on the estate: carters, blacksmiths, painters, plumbers, forestry and farm workers, to name but a few. Several improvements in the management of the estate were also instituted, greatly to the advantage of the people employed on it, yet the genial landlord always took every opportunity to encourage thrift.

But Sir Frederick’s social concerns were not confined to his own dependents, for he was

a liberal supporter of Friendly Societies, and took a lively interest in all institutions which tended to the development of the principle of self-help among the industrial classes. His breezy park and well-kept gardens have always been thrown open to the people of Portsmouth during the summer months for charitable fetes, and he even provided a big tent and cooking appliances for the convenience of the numerous parties visiting his grounds, which have almost been regarded by the inhabitants of this borough as a ‘People’s Park’.

Other features of Sir Frederick’s regime at Leigh Park were: the annual fruit, flower and vegetable show which took place there, usually in July, and which also involved a prize for creating the most beautiful cottage garden; the annual Harvest Home for the estate employees and their families, which usually took place in September or October; and an annual gymkhana, which usually took place in October. But Sir Frederick, the obituary continued, was a true “philanthropist” who was “anxious to use his wealth and influence for the good of the community, irrespectively of party or creed”. So when, during a period of insecure property values and financial troubles generally, the Portsea Island Building Society (established 1846) collapsed in April 1892, Sir Frederick seems to have stepped in financially on behalf of the sufferers – mainly members of the working class who were trying to acquire their own homes. (The collapse was partly because of fraud activities on the part of the Secretary, Thomas Pratt Will (1818–96), who was, in June/July 1893, found guilty of misconduct and the falsification of accounts and sentenced to five years’ penal servitude in Parkhurst Prison, on the Isle of Wight.) Sir Frederick did good in various other ways, too – but always “in a quiet and unostentatious manner”, and “there was scarcely a charitable organization of which he was not a supporter”. Every year at Christmas time, his estate provided Portsmouth Workhouse with a load of evergreen fronds so that the inmates could dress the building and make it look less austere.

After his retirement, on 10 January 1901, “in recognition of his many services and to express the gratitude of the inhabitants”, Sir Frederick was presented with the Honorary Freedom of the Borough of Portsmouth at a ceremony which, presided over by the Mayor, took place in the Town Hall at a special meeting of the Town Council and was followed by “the customary banquet in the evening”. The report continues: “the scroll containing the Freedom was enclosed in a casket of silver-gilt of very handsome design and workmanship and the presentation formed a very pleasing conclusion to Sir Frederick’s career, coming as it did so soon after his retirement from political life”. Then, 15 months later, Sir Frederick and his wife “were also made the recipients of presentations from their Havant neighbours in recognition of the interest they had shown in local affairs for so many years”. On Saturday 26 April 1902 the members of the Havant branch of the Hampshire Friendly Society presented Sir Frederick with a silver salad-bowl, “and on the following Tuesday a deputation of Havant residents […] waited on him and Lady Fitzwygram at Leigh Park, and presented the former with a silver salver, and the latter with a bracelet of turquoise and pearls set in gold”.

Frederick Loftus Francis Fitzwygram’s mother, Angela Mary Ada Louisa (née Vaughan), was the daughter of Thomas Nugent Vaughan (c.1808–47), an Irish magistrate and railway company director, who had died of cholera in Dublin, and Frances Mary Vaughan (1810–77) (née Territt), the widow of Major-General George John, Viscount Forbes (1786–1836). After the death of her second husband Frances Mary Vaughan reverted to the name Viscountess Forbes, and her eldest son by her first marriage became the 7th Earl of Granard in the Irish Peerage. From 1837 to 1874 she served as a “Woman of the Bedchamber” to Queen Victoria.

Siblings

Brother of:

(1) Robert, born and died 31 August 1883;

(2) Angela Catherine Alice (1885–1984). She did not marry.

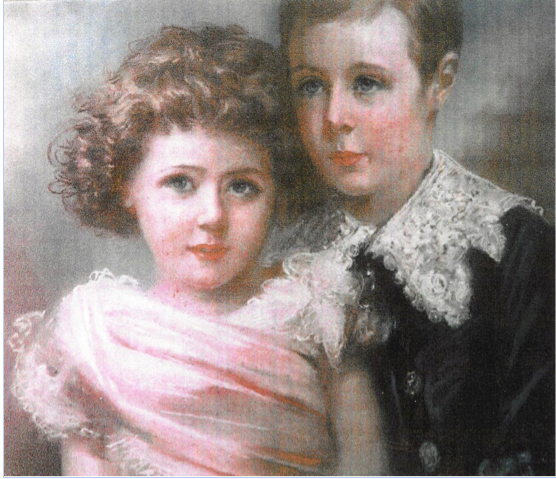

Frederick Loftus Francis and Angela Catherine Alice Fitzwygram (painted c.1895 by an unknown artist)

(By kind permission of Alexandra Hayward (Sitwell))

During World War One, Angela worked as a nurse at the Langstone Towers Auxiliary Military Hospital, in nearby Havant, and throughout her life at Leigh Park she was an enthusiastic supporter of the local Conservative and Constitutionalist Associations. After her brother’s death, Angela and her mother tried to run the Leigh Park Estate as before, making it available to various functions and the general public. But as the decade went on, it became ever harder to do this and as her mother grew older, Angela had to take over more and more responsibility for the estate, which was signed over to her entirely on 17 April 1926 and which she inherited on her mother’s death on 5 August 1935. In July 1930, when she was 85, Lady Fitzwygram had fractured her thigh in a fall at home and was thereafter all but house-bound.

On 17 December 1936, on Angela’s instructions, Farebrother, Ellis & Co. of 29, Fleet St, London EC4, auctioned off the outlying portion of the estate – amounting to c.1,265 acres and mainly consisting of 18 tenant farms, smallholdings, and cottages – plus potential building land around Havant and Rowlands Castle. But although the tenants were given a guarantee that they would have the option of buying the property in which they were living, this did not happen and instead of the seventy-four lots listed in the sale catalogue, the property was sold off in one lot – starting at £50,000 – at the knock-down price of £65,500 (plus the timber at £4,129 to the same bidder). It has to be said, however, that the purchaser, a successful property developer and builder, offered all the tenant farmers and smallholders the chance of staying where they were and most of them accepted this offer. Angela left Leigh Park in 1939 and moved to a smaller house in a few acres of land at Hindhead, Surrey, where she lived until her death not long before her hundredth birthday. In doing so she severed the last substantial connection between the Fitzwygram family and the Leigh Park estate – though she continued to be the owner of the unsold property until about May 1944.

From August 1940 to 1944 the estate was used for top-secret experimental work by the Admiralty Mine Design and Research Department; by October 1943 Portsmouth City Council was taking a serious interest in acquiring the remaining land from its various owners; on 10 January 1944 Angela approved a sale of “Building Materials and Estate Equipment”; and by early February 1944, thanks to the political shrewdness and sterling efforts of Councillor Frederick George Hutton Storey (1903–70), Portsmouth City Council had agreed to buy the remainder the Leigh Park Estate, including Leigh Park House, so that a satellite town could be built there. On 9 May 1944 it was announced publicly that the Council had acquired two areas of land, amounting to 1,672 acres, for £122,465, i.e. £75 an acre, whereas those plots of land which had been sold off between the sale of 1936 and 1939 had cost up to £500 an acre, meaning a substantial saving for the public purse. As much of the estate was deemed green belt by the Portsmouth Council it was not built upon and was left as it was to become the Staunton Country Park. But after standing empty for 15 years, Leigh Park House was demolished for safety reasons in June 1959.

Education

A fascinating and highly laudatory description of the way in which the two young Fitzwygrams were trained to be model English children appeared on 12 November 1898 in the women’s magazine Home Chat:

‘Freddie’ […] is fourteen, and is now at Eton, in Mr White Thompson’s house. He is talented, very studious, and possesses already a courtly charm of manner and speech that is remarkable in so young a boy. Both he and his sister ride well, and Freddie loves cricket and sport – especially shooting, the keeper at Leigh Park being of opinion that he will make a first-rate shot. He was very popular at his preparatory school and will probably be so at Eton. […] General Sir Frederick FitzWygram is as fond of his two children as their mother is, and during his convalescence in the early autumn, after an interval of bad health, it was a pleasant sight to see him with his son, who was at home for the holidays, and whose supporting arm and interested companionship were always at his father’s service. There is a bond of good fellowship, as well of respect and love, between the father and son: and both Freddie and Kitten are typical English children, healthy, handsome and happy, and the sunshine of their mother’s life.

Lady Fitzwygram’s love for her boy and girl is sufficiently strong and unselfish to prevent her [from] spoiling them. They have been from babyhood constantly with her and with their father; yet have learnt to consider that the time and attention given to them by both is a privilege of love, and not a right to be demanded in and out of season without consideration for the many duties – social and otherwise – that necessarily occupy the time off their parents. They have been trained to immediate and unfaltering obedience in small as well as great things, to gentleness in manner and speech, to courtesy and to self-control. The example held up to Freddie has been that of yielding to his mother’s and sister’s wishes before his own; and there has therefore been no contradictory influence in his life to spoil what his own nature would guide him to be. There is strength as well as sweetness in that nature. The home training of the two, in fact, has been a régime of kindness, of justice, and at the same time of firm and careful control. Plenty of work and learning, without sacrificing health to mental culture; plenty of healthy enjoyment in between; no idle or listless hours; no useless cramping rules; the life, in fact, that – given by English mothers at their best to their children – makes representative Englishmen and Englishwomen.

From c.1891 to 1898 Fitzwygram attended St Neots School, Sunningdale, Berkshire, (founded 1886 as Mr Locke’s School, Sunningdale, Berkshire and moved to Eversley, Hampshire, in 1888), after which, despite his father’s reservations, he attended Eton College from 1898 to 1902, where he won the King’s German Prize in 1901.

Fitzwygram matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1902, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1902. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1903 and then read Modern History. He was awarded a 3rd in Modern History (Honours) in Trinity Term 1905, having already taken his BA on 27 January 1905, and his MA in 1911. When he played for Magdalen’s 2nd cricket XI against Magdalen College School in the traditional matches of 1904 and 1905, he was opposed by H.H. Dawes, probably the School’s most outstanding cricketer of the pre-war era. Fitzwygram was also a passionate huntsman, and after his father’s death in 1904 he established his own pack of c.22 dwarf beagles at Leigh Park with which he hunted hares – mainly between Havant and the village of Liss, c.16 miles to the north-north-east. The pack was kept up throughout the war, even while he was a prisoner of war, and he last hunted the pack in March 1920, shortly before his death. The pack was then sold to Captain Keith Stuart Murray Gladstone, MC (1894–1965), of Moortown House, Ringwood, Hampshire, who changed its name from the Leigh Park Beagles to the New Forest Beagles. In 1907 Fitzwygram emulated his late father by joining the Havant Bench and sitting there when available.

Military and war service

Fitzwygram was gazetted Second Lieutenant on the Unattached List on 21 July 1905 and in the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Scots Guards, a year later (London Gazette, no. 27,820, 21 July 1905, p. 5,068; no. 27,933, 20 July 1906, p. 4,975); on 6 March 1909 he was promoted Lieutenant in ‘F’ Company (LG, no. 28,249, 11 May 1909, p. 2,560). In late July 1914, the 2nd Battalion was stationed at the Tower of London, carrying out the ordinary duties of a peace-time garrison. But by 20 September it was in camp at Lyndhurst in the New Forest, as part of 20th Brigade (commanded by Brigadier (later Major-General Sir) Harold Goodeve Ruggles-Brise; 1864–1927) in the 7th Division (commanded by Major-General Sir Thompson Capper; 1863–1915).

Like most British infantry divisions of the time, the 7th Division comprised three infantry brigades, each of four regular battalions, most of which, up to the outbreak of war, had been garrison battalions in Britain’s overseas empire. Consequently, it was necessary to await the return of all of them before the new Division could be properly constituted. But by 4 October 1914 the waiting was over and at 21.00 hours the 7th Division marched to Southampton, where it embarked for France at around midnight on the SS Lake Michigan (1901–18; torpedoed by U-100 on 9 April 1918 while en route from Liverpool to St John, New Brunswick, Canada) and the SS Cestrian (1896–1917; torpedoed by UB-42 on 24 June 1917 four miles south-east of the Island of Skyros, Greece, while en route from Salonika to Alexandria, with the loss of only three lives out of her 800+ passengers and crew).

Three days later, at 07.00 hours, the Division disembarked at the Belgian port of Zeebrugge, tasked with helping the Belgian Army, reinforced by the British Royal Naval Divison, to prevent the Germans from capturing the key port of Antwerp. But as it was unable to do this, it was forced to withdraw eastwards by train to Bruges, where Fitzwygram’s 2nd Battalion arrived by 11.00 hours on 7 November 1914. Then, on 9 October, according to the letter that Fitzwygram wrote to President Warren on 3 February 1915 to congratulate him on his knighthood of August 1914, the 7th Division, including the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards, had to pull back south-eastwards for another 24 miles to Ghent and create an eastwards-facing front there in order “to cover the retirement of the Belgians from Antwerp”, 32 miles to the east-north-east. Although Fitzwygram told Warren that the inhabitants of Ghent had greeted the 7th Division with great enthusiasm and given them gifts of food and tobacco, his opinion of the Belgians as a whole was pretty grim and he continued his letter to Warren as follows:

They are more like a mob than an army & have put up a very poor show. When Antwerp was bombarded the Belgiums deserted the forts they were holding, & on the Yser, the only way the French force, which was behind them, succeeded in making them fight was by shooting every Belgian that came back! However the British Public like to read of Belgian bravery, so the papers kindly oblige them.

For three more days the 2nd Battalion moved towards Ypres over difficult cobbled roads, which made marching uncomfortable, and finally reached the village of Zillebeke, a mile and a half south-west of Ypres, at 01.00 hours on 15 October, four days before the start of the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–22 November 1914). Here it was relieved by French troops and began to make contact with the advanced British units that were being transported north-westwards from the battlefields of the Aisne during the so-called Race for the Sea (see G.M.R. Turbutt).

During the early part of the First Battle of Ypres, the heaviest fighting on the 40-mile-long front took place in the southern sector, towards Armentières, just over the border in Northern France, and Fitzwygram’s Battalion was not involved in it. But after a brief period of being in reserve at Verbranden Molen, just south of Zillebeke, the Battalion began to see heavy action. Soon after midnight on the night of 16/17 October sounds were heard of an attack on 21st Brigade; during 17 October 20th Brigade mounted a reconnaissance in force eastwards towards Gheluveit (Geluveld) in order to establish the German positions. By 22 October the Battalion was at the village of Veldhoek, just north of the Menin Road and three miles east-south-east of Ypres; the Germans attacked and the Battalion moved a mile or so north-eastwards to Polygon Wood, where it spent the day. It then experienced heavy fighting in the area between Zandvoorde and Kruise[e]ke, roughly two miles to the south of the wood, until 26 October, during which period its original strength was reduced from 1,004 to 460 officers and ORs (other ranks). By 24 October, ‘F’ Company, which was dug in north of the Menin Road, had been reduced to 26 survivors including Fitzwygram, and the rest had been buried alive by shell fire or taken prisoner. In a report, Major-General Capper, the Divisional Commander, commented as follows on the fighting in which the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards had been involved during the night of 25/26 October:

they were almost completely surrounded by the enemy, and were attacked in front and rear; nevertheless their reserve company counter-attacked the enemy and drove him from some houses, capturing 8 officers and 200 other prisoners. During the fighting this battalion lost very heavily.

On 27 October the 20th Brigade was ordered to move northwards to Gheluveit in order to support the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, another unit with which it was brigaded, and Fitzwygram’s Battalion was involved in such intense fighting that by the evening of that day it was reduced to 11 officers and c.500 ORs. After these few days of action, the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards needed to be drastically reformed and Fitzwygram was promoted Captain with effect from 30 October 1914 (London Gazette, no. 29,001, 8 December 1914, p. 10,554; no. 29,084, 26 February 1915, p. 1,984). But almost immediately, at dawn on 29 October – after only one day’s rest – the Battalion returned to the dug-outs at Veldhoek, only to discover that the German artillery was concentrating its fire on the Menin Road. So between 10.00 and 11.00 hours, Fitzwygram’s 2nd Battalion and the 2nd Battalion of the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment), part of 91st Brigade and in the 7th Division since 19 September 1914, were sent up to counter-attack the Germans in a north-easterly direction. The attack succeeded and all positions beyond Gheluveit that had been lost earlier were recaptured. But when, in darkness and heavy rain, the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards were withdrawing to the main British line, their own side mistook them for the enemy and opened fire, causing many casualties. So as, by the end of 29 October, the 2nd Battalion had lost four officers and 136 ORs killed, wounded and missing over the previous three days, it was sent to the Army Reserve at Méteren, well to the south-west of Ypres over the border with France and just west of Bailleul. On 5 and 6 November it was relieved at the front and sent to Bailleul, where, on 11 and 12 November, it was reinforced by 12 new officers and 535 ORs.

On 14 November, with a week of the First Battle of Ypres still to go, the reconstituted 2nd Battalion was moved a good way to the south-east and into a different sector of the front. It took over trenches from the 19th Brigade at Sailly-sur-la-Lys, c.12 miles west of Lille and two miles north-east of Estaires, with an Indian Brigade on its right. The weather here was cold, with hail and snow; snipers were fairly active; and the trenches needed much repair work, being in a very poor condition that was made worse by the winter weather. From here, an officer and eight ORs made the 2nd Battalion’s first raid on the enemy’s trenches during the night of 27/28 November. After this, nothing unusual occurred until the night of 17/18 December, when, at the hamlet of Rouges Bancs, just to the north-north-west of Fromelles and about four miles south-east of Sailly-sur-la-Lys, the Battalion took part in a major two-company attack on the German positions, during which Fitzwygram was wounded in the head by shrapnel while leading ‘F’ Company on the right. Guardsman James Mackenzie of Fitzwygram’s Battalion (1889–1914) was awarded a posthumous VC for rescuing a badly wounded man from in front of the German trenches under very heavy fire (Edinburgh Review, no. 12,771, 23 February 1915, p. 2) (he was killed in action on the following day while attempting to repeat this act of bravery; no known grave). However, the attack was not a success and the Battalion was withdrawn from the trenches on 19 December having suffered 186 casualties killed, wounded and missing.

The Battalion returned to the trenches on 23 December, when it began a four-days-in and four-days-out routine that went on until the end of February 1915, pending the arrival of Kitchener’s New Army battalions. Fitzwygram was sent back to England to convalesce, and as he was still there on 12 May 1915, playing cricket for the Household Brigade against the MCC, it is certain that he took no part in the Christmas Day truce, when almost the entire 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards left their trenches unarmed and went to the centre of no-man’s-land in order to meet their German opponents, the 15th, 37th and 158th Regiments and a Jaeger Regiment (Light Infantry), to talk, exchange little presents, sing, and play a game of football. But during his convalescence, he concluded his letter to Warren of 3 February with the observation: “The Germans are putting up a very fine fight & we shall have to put at least 2,000,000 more men into the field if we are to beat [them].”

Sir Frederick Loftus Francis Fitzwygram, 5th Bt, MC, MA

(Daily Record, no. 21,244, 20 February 1915, p. 8)

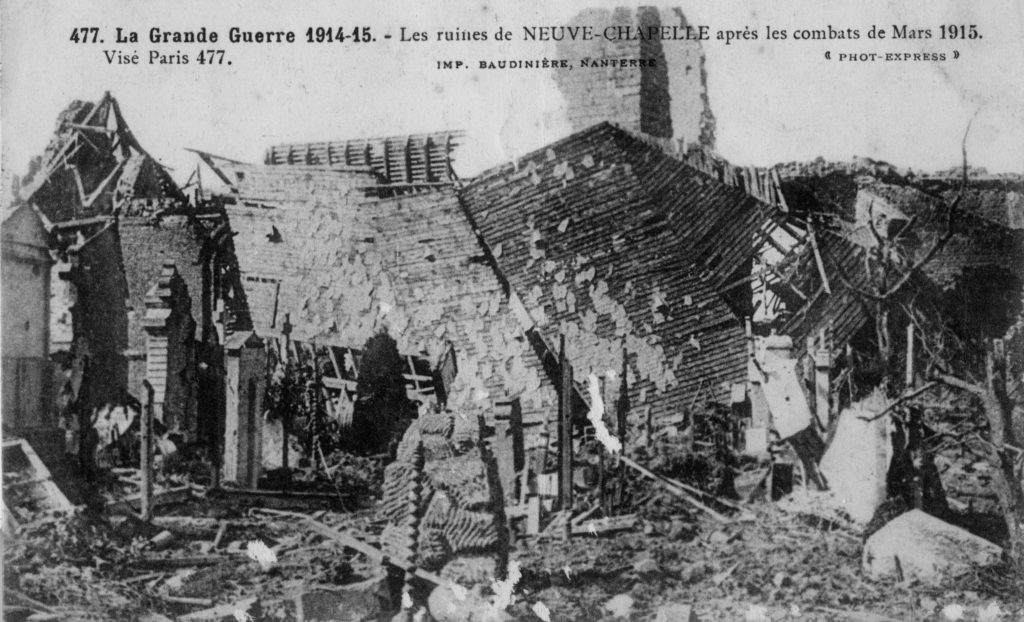

Fitzwygram’s Battalion remained in the bad, waterlogged trenches near Sailly-sur-la-Lys until 1 March 1915, when it marched about six miles north-westwards to Vieux Berquin via Estaires and Neuf Berquin, and thence about four miles south-eastwards to Estaires, where it prepared for the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March), the first major British offensive of the war. It required 87,000 British and Indian troops to punch a hole through the German line on a two-mile front, in the mistaken belief that the German trench defences were not yet sufficiently developed to resist such an attack. But the Germans were contemptuous of British offensive potential and had withdrawn men and guns to the Russian front. So the British High Command proposed that independently of any action by the French, a surprise attack should be made on the narrow front by 48 battalions (40,000 men) against three German battalions (1,400 men with 12 machine-guns). The offensive had three aims: the capture of the village of Neuve Chapelle and the low-lying Aubers Ridge that lay beyond it; the elimination of the German-held salient that bulged out westwards round Neuve Chapelle into the Allied line; and the exploitation of any territorial gains by means of a cavalry attack in the direction of Lille. General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s IV Corps was to open the assault in the north, while the IV (Indian) Corps’s Meerut Division – minus M.A. Girdlestone’s Bareilly Brigade – was to lead the attack in the south.

The two-pronged attack began on 10 March, when Fitzwygram was still recovering from his wound in England. But on this day, his Battalion of the Scots Guards marched to and dug in in Cameron Lane, near Pont-du-Hem, on the east side of the Estaires–La Bassée road, where, as part of the Corps Reserve, it took no part in the fighting. The attack was preceded by a 35-minute bombardment by 342 guns along a 2,000-yard front, during which, it has been estimated, the British fired more shells than during the entire Second Boer War. Things went well initially and the British and Indian infantry took their first objective, the village of Neuve Chapelle. Then, at 04.00 hours on 11 March, the 2nd Battalion was marched up to the front line and ordered to attack at 07.00 hours in support of the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, in the direction of Piètre on the right and Aubers on the left – both to the north-east of Neuve Chapelle. But by the morning of 11 March, the Germans had brought up reinforcements and placed them in positions that were as yet unknown to the British generals, and as a result the Grenadiers were held up after advancing only 1,000 yards. Moreover, by mid–late morning the visibility was poor; the British and Indian artillery were running out of shells whereas the German artillery was not; and the five Battalions of 20th Brigade, who were supposed to be at the forefront of the attack, were forced to dig in and sit out the day under a fairly heavy German bombardment – which caused numerous casualties. As a result, little progress was made and the losses increased as British and Indian units assaulted unassailable enemy positions. During all of this, Private Isaac Reid (c.1895–1915) of Fitzwygram’s Battalion left his position suffering from battle stress and shell-shock. He was caught and arrested a few hours later, tried before a Field General Court Martial, sentenced to death and executed by firing squad on 9 April 1915, aged 20, even though he expressed regret for his action.

To make matters worse, the Germans had situated machine-guns on their flanks which prevented the forward movement of Allied reserves, and they launched a counter-attack which succeeded in regaining most of the land that the Allies had taken on 10 March. Because of this, the British were forced to cancel the continuation of their attack, which they had hoped to begin in the mid-morning of 12 March. Unfortunately, the lack of field telephones and the deaths of two runners prevented both Fitzwygram’s Battalion and the 2nd Battalion of the Border Regiment – another element of 20th Brigade – from hearing of the cancellation and they assaulted the heavily fortified German strongpoint known as the Quadrilateral as originally planned, but without artillery support. Although, as a result, both Battalions suffered heavy casualties from rifle and machine-gun cross-fire, when artillery support materialized at 11.30 hours it was heavy and accurate and the attacking battalions captured the German position and took c.800 prisoners and a machine-gun in the process. Finally, in the late afternoon of 12 March 1915, the 7th Division took part in a concluding assault on the German positions, but soon became bogged down in the churned-up battlefield; other assaults proved to be equally unsuccessful and by the end of 12 March, the 22nd Battalion of the Scots Guards alone had lost three officers and 289 ORs killed, wounded and missing. So on 13 March, the day after the fighting had officially ended on 22.40 hours, 20th Brigade was pulled back into Corps Reserve.

The Battle cost the British and Indian units c.11,200 officers and men killed, wounded and missing and the Germans about the same number of casualties. In the aftermath of the battle, Sir John French (1852–1925), the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force from August 1914 to December 1915, blamed its lack of success on the shortage of shells – despite the huge number which had been fired – and this led to the so-called “shell crisis” of May 1915 which brought down Asquith’s Liberal government and caused the creation of a Ministry of Munitions under David Lloyd George.

Between the end of the Battle of Neuve Chapelle and the start of what became known as the Second Battle of Ypres (21 April–25 May 1915), Fitzwygram’s 2nd Battalion remained in the trenches near Sailly-sur-la-Lys or trained nearby – mainly route-marching – or was used by the Royal Engineers for fatigues or was in billets in Laventie, a mile or so to the south. On 4 April and in late April, 165 and 125 reinforcements arrived for the 2nd Battalion, but on 12 May it left its billets in Laventie and marched to new ones in the village of Hinges, two miles north of Béthune and about four miles north-west of Festubert. Then, on the early evening of 15 May, the eve of the Battle of Festubert (16–25 May), the 2nd Battalion, with Fitzwygram now a Captain and back in charge of ‘F’ Company, marched to just north of Festubert and by 23.00 hours had taken up the positions from which it would launch its assault on the following day.

At 03.15 hours on 16 May 1915, after a 30-minute artillery bombardment, the 2nd Battalion, with ‘F’ Company on the right, attacked eastwards towards the hamlet of La Quinque Rue, whereupon at c.05.30 hours the Germans responded with heavy machine-gun fire and counter-attacked from an orchard on the attackers’ left and from their left rear. Apart from 37 ORs who managed to fight their way out to the right and link up with the 1st Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, part of 22nd Brigade, ‘F’ Company was completely surrounded and, if its officers and men were not killed in action during the fierce hand-to-hand fighting that ensued, they were forced to surrender. By the end of 16 May, ten officers and 401 ORs of the 2nd Battalion of the Scots Guards were killed, wounded and missing. At first, Fitzwygram was reported missing presumed dead, but during the fighting he had been badly wounded by a bullet that went through his right shoulder diagonally, just missed the joint, and caused a compound fracture of his right arm, just below the shoulder, and when he was taken prisoner by the Germans he was unconscious. His mother received the official news of this on 21 May 1915, and in a letter that Fitzwygram wrote to President Warren on 21 July 1915 from the Reserve-Lazarett in Düsseldorf, where he had arrived on 10 June after three weeks in a field hospital, Fitzwygram described what had happened as follows:

We had taken two lines of trenches & a small fort behind. When the German counter-attack came[,] our outposts were unable to get up to us, & the lot I was with were surrounded. I was knocked out in the middle of the fight & when I came to[,] the Germans had charged our position. I don’t know what happened, except that a lot of dead, English & German, were found two days later.

The Germans saw to his injuries and generally treated Fitzwygram well. The fighting at Festubert resumed on 20 May 1915, and the village was taken, but at a total cost to the 7th Division of 167 officers and 4,123 ORs killed, wounded and missing.

George Valentine Williams (1883–1946), a journalist and popular novelist who worked during World War One as a war correspondent for Lord Rothermere’s stridently pro-war Daily Mail and who, on 7 August 1915, would publish a heroising account there of G.U. Robins’s death near Hill 60 on 5 May 1915, published a stylistically similar account of the circumstances surrounding the destruction of ‘F’ Company and Fitzwygram’s wounding. This appeared in the same newspaper on 29 July 1915:

A great wide grave somewhere near the Rue de Bois, a ragged country road about which the battle raged, contains the remnants of a company of Scots Guards, eighty gallant ‘Jocks’ and two of their officers, who died rather than nullify the Guards’ boast that they had never lost a trench in this war. The lost company formed part of the 2nd Battalion of this historic regiment which went forward with the rest of the infantry through a green vapour of lyddite smoke to attack the German trenches. The heavy casualties which they have suffered in this war have not been allowed to affect the standard of physique which was ever the pride of the jocks, and it was a truly splendid set of men that dashed across the open, Sir Frederick Fitzwygram at their head, side by side with the Borders, in the face of a murderous fire. The Borders, badly enfiladed by machine-gun fire, were checked in their rush; the Guards, more fortunate, went on, one company outdistancing the rest. That company was never seen again. After the first stage of the fight was done[,] word came back to the Brigade headquarters that the British troops had found and buried the bodies of two Guards officers about the spot where the lost company had been seen, with the Germans pouring a murderous fire from three sides. An officer was sent to investigate. This is what he found. Over against two rough crosses marking the graves of the two officers eighty Scots Guards lay dead in the open. Their comrades, who had given a decent sepulchral send-off to the two officers of the party, had not had time, in the heat of the fight, to bury the men. Soaked by the rain, blackened by the sun, their bodies were not beautiful to look upon; but the German dead spread plentifully around. The empty cartridge cases scattered all about, the twisted bayonets and the broken rifles show a price a Scots Guard sets upon his honour. No monarch ever had a finer lying-in-state than those eighty Guardsmen dead amid the long coarse grass of this dreary Flanders plain.

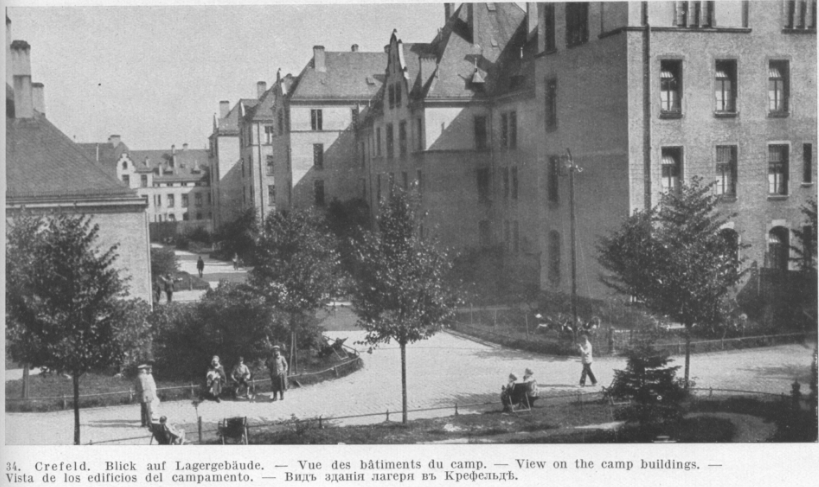

In November 1915 Fitzwygram told his mother in a letter that he had been released from the Düsseldorf hospital and was now confined to the Officers’ Internment Quarters at nearby Krefeld, where he was “privileged” to be sharing a small room with a brother officer, given that there was so much overcrowding among the internees. He remained at Krefeld until he was moved to Holland in April 1918 – probably as part of an exchange programme by means of which sick prisoners of war were interned for the duration of hostilities in a neutral country: Fitzwygram was sent to the Dutch coastal resort of Scheveningen where he was probably accommodated in a hotel. In June 1918, the Eton Chronicle reported that although a large number of Etonian officers were now interned in Holland, “it was not thought advisable, owing to the prevailing circumstances, to have an Etonian Dinner on the Fourth of June [Founder’s Day]” and so a cricket match was arranged instead that was played on the sports ground at Scheveningen’s Tentoonstellings Terrein. Fitzwygram played for the losing side and scored 12 runs, but did not bowl – probably due to his injured arm. He was mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, no. 29,072, 16 February 1915, p. 1,658); awarded the MC on 5 May 1919 (LG, no. 31,769, 27 January 1920, p. 1,219); and promoted Major on 22 January 1920 (LG, no. 31,763, 30 January 1920, p. 1,358).

Fitzwilliam was released on 26 December 1918 and after his return home to Leigh Park House in the early days of 1919, he continued to indulge his interests in cricket and beagling – though after his death his obituary in the Portsmouth Evening News noted that although “he took little part in public affairs” he did continue “the established custom of allowing the use of the park for various purposes, particularly for children’s outings”, and that many of these had been revived in 1919, causing the park to be “crowded with happy parties on many of the weekly holidays”. Between 24 May and 26 July 1919 he played cricket at least ten times at Lords – mainly for the Household Brigade at both Lords and the Kennington Oval, but also once for I Zingari against Harrow School. In summer 1919 he also played several games for Havant Cricket Club, of which he was the captain. But in early May 1920, newspapers began to report that Fitzwygram had been sick for about three weeks and was now “dangerously ill”. He died on the night of 5 May 1920, aged 35, at Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital, Millbank, London, of what his death certificate calls “blood poisoning following influenza”. It may well be that the influenza was part of the Spanish flu pandemic that affected 500 million people worldwide and caused between 50 and 100 million deaths between January 1918 and December 1920. But the immediate cause of the blood poisoning seems to have been an accidental cut which Fitzwygram incurred while hedging and which may have been made more acute by the direct or indirect effect of his wounds.

Mr Haggie (left) and Sir Frederick Fitzwygram (right) hunting with the South Oxfordshire Foxhounds at Thame

(Daily Sketch, no. 1,400, 26 November 1919, p.30)

As Fitzwygram was still a serving officer, he was accorded full military honours at his funeral. His body had been brought from London to Hampshire by train on Saturday 8 May 1920, and the funeral service began at 03.15 hours on Monday 10 May 1920, when his coffin was borne on a gun carriage from Leigh Park House, through Leigh Park to the churchyard of St John the Baptist’s Church, Rowlands Castle, Redhill, Hampshire. Colonel Roger Stephen Tempest, CMG, DSO (1876–1948), Major Harold Walter Edwards, DSO, MC (1887–1973), Captain Walter Alastair Boyd, MC (1890–1956) and other brother officers walked behind it; his mother, sister, and various aunts and cousins were the family mourners; sergeants of ‘F’ Company of the 2nd Battalion, the Scots Guards, acted as pall bearers; ORs of the same Battalion provided a firing party; and the local boy scouts formed the guard of honour. At the church “there was a large gathering, which included representatives of all classes in the surrounding district” and Fitzwygram’s body was laid to rest in the same vault as three other members of his family in the churchyard at Rowlands Castle. The memorial cross above the family grave bears the inscription “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see their God” (Matthew 5:8), which is also the first line of a well-known hymn with words by John Keble (1792–1866) and music by Charles Lockhart (1745–1815).

Fitzwygram’s coffin leaving Leigh Park House for the funeral

(From The Last of the Line by kind permission of Steve Jones)

A long report of Fitzwygram’s death appeared in the Portsmouth Evening News on Friday 7 May 1920, which began by saying it was “a loss which will be felt in many respects through this part of Hampshire, and genuine sympathy will be extended by all classes to Lady and Miss Fitzwygram, the mother and sister of the deceased.” It continued:

It had been locally known for just over a week that Sir Frederick was seriously ill, and prayers were offered for his recovery at St Faith’s Church, Havant, on Sunday. We understand that his illness has been of about three week’s duration, and originated with an attack of influenza, but other complications ensued, and the end came as a result of blood poisoning. […] On his return home [from captivity] in the early days of last year, [he] resumed his interests in life. He was keen respecting his military duties, and although he took little part in public affairs, he was a great supporter and devotee of sport. For years the Leigh Park Beagles have provided famous sport in this part of Hampshire, and Sir Fred has spent many happy days with his pack during the past winter, the season having been a highly successful one. At cricket he was clever both with bat and ball, and fulfilled many cricket engagements last season. Not only was he President of the Havant Cricket Club, but he found time to play in many matches for the Club last year, his skill contributing much to what proved to be a season of successful victories. Since he inherited Leigh Park, Sir Fred had continued an established custom of allowing the use of the park for various purposes – particularly for children’s outings, and the revival of many of these last year saw the park crowded with happy parties on many of the weekly holidays.

Although the writer of the above report-cum-eulogy was clearly doing his best for his subject and said all the correct things, one has the overall sense that he had difficulty doing so for the simple reason that his subject was never a commanding personality like his father. In the pretty little painting of him and his sister, it is she who stands out as the forceful one, and in the other pictures that we have of him, there is a weakness about his facial expressions, a lack of determination and direction which makes him look to one side and away from the viewer. The same also applies to the massive painting of him in the uniform of a subaltern of the Scots Guards, from which he is staring straight at the viewer, but blankly, timorously almost. Did he, like so many young men of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, feel overwhelmed by an impressively powerful father despite that father’s reported affection for both of his children? And is it just chance that his chosen breed of dog was dwarf beagles, which, we are told, he started to breed only after his father’s death in 1904? His wounding and experiences as a prisoner of war would have done little for his strength, and what we know of his post-war activities suggests a young man whose character is held together by custom and family tradition but lacks independent-mindedness and those qualities which are needed for real leadership, whether as an upper-class civilian or as a Guards officer. So when he was attacked by what may have been influenza and blood-poisoning that was caused by a trivial domestic injury, he seems to have simply faded away, liked but not greatly respected by his social inferiors who referred to him, even in print, by the affectionately familiar, but not particularly deferential name of “Sir Fred”.

Fitzwygram is commemorated by a window in the south transept of St Faith’s Church, Havant, and on the Havant War Memorial, which is just outside St Faith’s. The window was dedicated at the packed morning service on Sunday 24 September 1922 and features St George (left), St Michael (centre) and St Hubert (right), the Patron Saint of hunters inter alia. The following inscription is under the figure of St Michael: “In loving memory of Sir Frederick L.F. Fitzwygram, Bt. M.C., Major Scots Guards. Died from the effects of the Great War, 5th May 1920, aged 35 years. He being made perfect in a short time, fulfilled a long time” (The Wisdom of Solomon 4:13). The west window in St Faith’s commemorates his father and the Chancel contains a memorial to his mother.

South transept window, St Faith’s Church, Havant

(Courtesy Martin Baxter, http://www.hampshirechurchwindows.co.uk)

Fitzwygram’s title passed to a distant cousin, Sir Edgar Thomas Ainger Wigram, 6th Baronet (1864–1935), a great-grandson of Robert Wigram [I]. Although on the outbreak of war Fitzwygram had ensured that his successor to the baronetcy would have an adequate income, his mother and sister were the main beneficiaries of his estate – £257,989 4s. 2d.

At first, because of the uncertainties surrounding Fitzwygram’s death, his name did not appear on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Roll of Honour. But it was decided that any Commonwealth or British serviceman who had died while in service with the military between 4 August 1914 and 31 August 1921 should, regardless of the cause of death, be accorded war grave status. Which means that besides those men and women who were killed in action or died of wounds received in action, the Roll of Honour now includes those who died because of disease, illness, accident, suicide, homicide and even judicial execution. Additionally, the Roll of Honour also now includes the names of those who, having been discharged from service, died within the war period from injury or illness that was caused or exacerbated by their war service. But such cases qualify for inclusion only if it can be proved to the service authorities that their death was service attributable. Fitzwygram falls into the former category.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*Betty Marshall, Sir Frederick Fitzwygram of Leigh Park House (Havant Regional Papers No.1) (Havant: Friends of Havant Museum Local History Group, 1999).

*Steve Jones, Lt. General Sir Frederick Wellington John Fitzwygram, Bt., of Leigh Park (1823–1904) – History of the Leigh Park Estate, 1874–1904 (Includes a History of the Fitzwygram/Wigram Family, Vol. 1 (Havant Borough History Book No. 68) (Havant: Museum Local History Booklets, 2016).

** Steve Jones, Major Sir Frederick Loftus Francis Fitzwygram, Bt, MC of Leigh Park (1884–1920): “The Last of the Line” (Includes a History of Leigh Park, 1904–1944 (Havant Borough History Book No. 73) (Havant: Museum of Local History Booklets, 2017).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], Annual Register 1830 (London: Baldwin and Cradock, and others, 1831) p. 277.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Sir Robert Fitz-Wygram [sic]’, Surrey Comet, no. 996 (6 September 1873), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Failure of a Building Society’, The Times, no. 33,508 (15 December 1891), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘The Portsea Building Society’, East and South Devon Advertiser, no. 1,468 (1 April 1892), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Portsea Island Building Society’, The Times, no. 33,603 (4 April 1892), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Model Mothers’, Home Chat, 15, no. 101 (12 November 1898), pp. 403–5.

[Anon.], ‘Sir F. Fitzwygram: Aged Baronet’s Death’, Portsmouth Evening News, no. 8,556 (10 December 1904), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Frederick Fitzwygram, Obituary’, The Times, no. 37,575 (14 December 1904), p. 10.

[From our Military Correspondence], ‘Need for Shells: British Attacks Checked’, The Times, no. 40,854 (14 May 1915), p. 8.

G[eorge] Valentine Williams, ‘The Festubert Fighting: Splendid Gallantry of All Ranks: The Lost Scots Guards: A Record of the Queen’s’, The Daily Mail, no. 5,976 (29 May 1915), p. 5.

George Valentine Williams, ‘How the Scots Guards Died’, The Daily Mail (29 July 1915).

[Anon.], ‘Sir Frederick Fitzwygram: His Death in London: Officer and Sportsman’, Portsmouth Evening News, no. 12,286 (7 May 1920), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Sir Frederick Fitzwygram’, The Morning Post, no. 46,163 (7 May 1920), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sir F. Fitzwygram’ [report on the funeral], – – – , no. 46,166 (11 May 1920), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Funeral of Sir F. Fitzwygram, Hampshire Advertiser, no. 6,707 (15 May 1920), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Sir Frederick Fitzwygram’, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 93, no. 2,435 (15 May 1920), p. 406.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Major Sir Frederick Fitzwygram, and [Anon.], ‘May 11, 1920: Funeral: Major Sir F. Fitzwygram, Bt., M.C.’. Source unknown; both extant as cuttings pasted into the back cover of MCA: PR/2/19 (Warren’s Notebooks [Sept. 1917–Dec. 1921]).

Petre, Ewert and Lowther (1925), pp. 23-47, 55-68, 78-88, 90-6.

Bridger (2000), pp. 60, 71-2, 90

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/456-460 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to the Hon. F.L.F. Fitzwygram [1915–1918]).

OUA: UR 2/1/47.

Online sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Sir Robert Wigram, 1st Baronet’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Robert_Wigram,_1st_Baronet (accessed 18 March 2018).

Wikpedia, ‘Sir Robert Fitzwygram, 2nd Baronet’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Robert_Fitzwygram,_2nd_Baronet (accessed 18 March 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Frederick Fitzwygram’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Fitzwygram (accessed 18 March 2018).