Fact file:

Matriculated: 1900

Born: 17 February 1882

Died: 25 May 1917

Regiment: Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars

Grave/Memorial: Templeux-le-Guérard British Cemetery: II.E.40.

Family background

b. 17 February 1882 at Newport, Fife, Scotland, as the eldest child of Robert Fleming (1845–1933) and Sarah Kate Fleming (née Hindmarsh) (1857–1937) (m. 1881).From 1890 the family lived at Walden House, Chislehurst, Kent (eight servants), from 1902 at Joyce Grove, Nettlebed, to the north of Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire (12 servants), and from 1903 also at 27, Grosvenor Square, London W1.

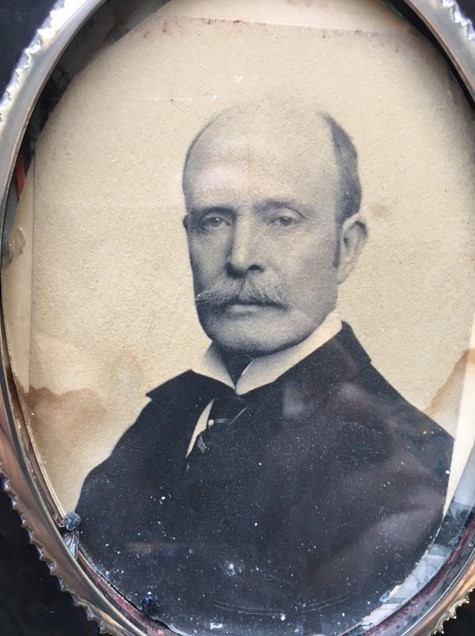

Parents and antecedents

Robert Fleming, who was born in a tiny house in Liff Road, Lochee, near Dundee, was the fourth child of John Fleming (1806–73), a farmer, who, after being ruined as a mill-owner by the crisis in the flax industry of 1843, became an overseer at one pound a week in one of Dundee’s linen and jute mills (see G.B. Gilroy). At that time, Dundee had some of the worst slums in Europe and five of John’s children died of diphtheria. When Robert was 13, he started work as an office boy at £5 p.a. and within two years became a clerk for the Cox Brothers, at that time the world’s largest firm of jute spinners. When he was 21, he became a book-keeper with Edward Baxter & Sons, whose Chairman was a Dundee merchant with large interests in American securities.

During his time with the firm, Robert became interested in stocks and shares, and despite the crash of 1866 in Britain which affected him personally, he became particularly interested in the potential of the booming American stock market during the period of recovery after the Civil War (1861–65) and visited America on behalf of his Principal in c.1870. Although the principle behind investment trusts had been known on the continent since the Middle Ages, Robert played a central role in designing a modern version and establishing the guidelines for their sound management. He thereby enabled nervous British investors to earn twice the interest from American railroad bonds that they could have earned from British government stocks. In 1873 he convinced four of Dundee’s leading businessmen to act as trustees for Scotland’s first investment trust, the Scottish American Investment Trust, of which Fleming became the Secretary. Over the next two years, two further trusts were floated, using money that had been raised mainly in Dundee, and thanks largely to Fleming’s efforts, the trusts did very well, despite the economic depression that afflicted America between 1873 and 1879. For the next half-century, Robert was regarded as an authority on investment in America and became a Director of several similar trusts and an adviser to many others. In the 1880s, he became a recognized expert on American railroads, and two important railroad systems were constructed in America thanks to his advice: the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fé and the Denver and Rio Grande lines. At some point, Robert was responsible for organizing bond- and shareholder opposition to Jay Gould (1836–92), the leading American railroad developer and speculator whose reputation was that of a “Robber Baron” and who was trying to gain control of the Texas and Pacific Railway for very little money.

In 1888, Robert’s links with London became stronger when he set up the Investment Trust Corporation there, and in 1890 he moved his business from Dundee to London, where he worked for three decades as a highly reputable City financier, underwriting companies all over the world by means of his network of investment trusts, insurance companies, etc.: it was, for example, his advice that assisted the formation in 1908 of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, the fore-runner of BP. It is estimated that by the time of his death, he had crossed the Atlantic c.130 times; he had become a Director of the Royal Bank of Scotland (1907), the British Investment Trust (1889), and the Metropolitan Trust Company (1899). In 1909, he set up his own private bank, Robert Fleming and Co., at 8, Crosby Square, Bishopsgate, London EC2: it was acquired by Chase Manhattan in 2000.

Robert was a serious and somewhat taciturn man who was committed to hard work and intolerant of idle conversation. Although he could appear severe and intimidating, he was a kindly person by nature and an adoring husband and father. He loved such outdoor pursuits as rowing, walking, stalking and shooting, having learnt to shoot during his time with the Dundee Volunteers when a young man. In 1903, the Flemings moved to Joyce Grove, a 2,000-acre estate at Nettlebed in Oxfordshire, where he demolished the seventeenth-century house that stood there and replaced it with what John Pearson called “an architectural tyrannosaurus” of a house that is now a Sue Ryder Home. Duff Hart-Davis describes it as “decidedly Gothic and totally hideous” and as being of “devastating ugliness”: but Pearson, more charitably, records that it:

was undoubtedly the best that money could buy. No window was left plain if stained glass could possibly be used instead. No balustrade remained uncarved. There was a hint of Chartres, a memory of Spa, an echo of all the most recent châteaux built along the valley of the Loire, with craftsmen brought over from France to achieve the correct effects. There were to be forty-four bedrooms, a great fireplace of Carrara marble weighing eleven tons, and the largest conservatory in south Oxfordshire.

In the latter part of his life, Robert took much interest in farming and forestry. Being philanthropically inclined, he also supported both local and national causes, particularly hospitals. He donated a recreation ground to the village of Nettlebed and in 1912 had a multi-purpose hall designed for the village by the Arts and Crafts architect Charles Edward Mallows (1864–1915). In 1906 he was appointed a member of the Finance Committee of King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London, and in 1909/10, he served as High Sheriff of Oxfordshire. During World War One he served on the Financial Facilities Committee and gave up part of his Grosvenor Square house for the use of wounded officers. He also gave large sums of money to University College, Dundee, including the money that was needed for the Fleming Gymnasium: in 1928 St Andrew’s University awarded him an honorary LL.D as a gesture of gratitude for his gifts and advice over many years. At about the same time Robert also acquired Black Mount, an 80,000-acre deer-forest near the Bridge of Orchy, in Argyllshire, where he and his family used to go for a sporting holiday every August. The estate is still owned by the Fleming family, since some years later it was put on the market by the Breadalbane Trustees and bought by Philip Fleming and his brother-in-law, the 2nd Lord Wyfold (see below). At Christmas 1928 Robert gave £130,000 to Dundee in order to finance the Fleming Housing Scheme, “which transported hundreds of slum-dwellers from their crowded, insanitary hovels in the backstreets of the city to the pleasant open spaces of a garden suburb at Wester Clepington”. He added a further £25,000 in September 1929, when the foundation stone of the project – a total of 400 houses – was laid by the Duchess of York; on the same day the grateful City of Dundee made him a Freeman of the City. He left nearly £2.2 million (according to the Measuringworth site, this would have been worth £95 million in 2005 – although, of course, nearly half of that sum would have been paid in tax), and is buried in the churchyard of St Bartholomew’s Church, Nettlebed, Oxfordshire.

Valentine Fleming’s mother was the daughter of a senior tax official in Scotland, and she and Robert got to know one another when they attended the Lindsey Street Congregational Church in Dundee.

Valentine Fleming (seated left), his parents (back row) and siblings (from left to right) Kathleen, Dorothy and Philip

(Photo c.1899, courtesy of the Fleming family)

Siblings and their families

Older brother of:

(1) Dorothy (1883–1976); later Hermon-Hodge after her marriage in 1906 to the Hon. Roland Herman Hermon-Hodge (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO, MVO, DL, JP, 2nd Baron Wyfold of Accrington from 1937) (1880–1942); one son, four daughters;

(2) Kathleen (1886–1957); later Hannay after her marriage in 1918 to Walter Maxwell Hannay, Croix de Guerre (1873–1952); two sons;

(3) Philip (1889–1971); married (1924) Joan Cecil Hunloke (1901–91), the daughter of the Olympic sailor (1908) and courtier Sir Philip Hunloke, GCVO, JP (1868–1947); two daughters, one son.

The Honourable Roland Herman Hermon-Hodge was the eldest of the seven sons (nine children, of whom one daughter – Marguerite – died in infancy in 1879) of Robert Trotter Hermon-Hodge (1851–1937), the 1st Baron Wyfold of Accrington, a well-known sportsman who lived at Wyfold Court, Rotherfield Peppard, near Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire. In 1877 Robert Trotter Hodge, as he was then called, married Frances Caroline (1856–1929), the daughter of the wealthy cotton-master Edward Hermon (1822–81), who had been the MP for Preston from 1868 to 1881 and built Wyfold Court between 1872 and 1878. On 1 January 1903, Robert Trotter Hodge had his name changed to Robert Trotter Hermon-Hodge by Royal Licence. He was the Conservative MP for Henley-on-Thames from 1895 to 1906, and after the death of Valentine Fleming he took over that constituency from 1917 to 1918 (London Gazette, no. 30,072, 15 May 1917, p. 4,756). Two of Robert Trotter’s sons died on active service during World War One. John Percival Hermon-Hodge (1890–1916) was killed in action at Ploegsteert Wood on 28 May 1915, aged 24, while serving as a Second Lieutenant with the 1/4th Battalion, the Ox. & Bucks Light Infantry (buried in Rifle House Cemetery, Grave III.F.1, inscribed “Sixth Son of Lord & Lady Wyfold Praemium Virtutis Gloria”); and George Guy Hermon-Hodge (1883–1916) died of wounds received in action on 7 July 1916, aged 32, while serving as a Captain with the 165th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (buried in Gezaincourt Communal Cemetery Extension, Grave I.B.12, inscribed “Son of Lord & Lady Wyfold ‘Quo Fas et Gloria Ducunt’”). A third son, Major the Hon. Robert Edward Udny Hermon-Hodge (1882–1937), was a brother officer of Valentine Fleming in the QOOH.

In 1899, Roland was gazetted to the 3rd Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, and served in the Second Boer War, gaining the Queen’s Medal with five clasps and the King’s Medal with two clasps. He became the Battalion’s Adjutant in 1905 and served throughout the Great War as Brigade Major, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General and Deputy Assistant Adjutant General. He was promoted Major in 1917, mentioned in dispatches once (possibly twice), awarded the DSO in 1917 and promoted Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel in 1919 (LG, no. 29,890, 2 January 1917, p. 197; no. 30,111, 1 June 1917, p. 5,476).

Walter Maxwell Hannay was a merchant.

Philip Fleming was educated at Eton and was a Commoner at Magdalen from 1908 to 1910, but left without taking a degree. While at Oxford, he won the Inter-University point-to-point, stroked the Magdalen VIII that went Head of the River in 1910 and 1911, and in 1910 rowed at No. 7 in the victorious Oxford VIII that included Duncan Mackinnon, Arthur Stanley Garton (see H.W. Garton and E.C. Garton) and A.W.F. Donkin (cox for the fourth time). In 1912, at the Olympic Regatta in Stockholm, Philip stroked the Leander Eight (all but one of whom were ex-Magdalen) which won by a length against New College, Oxford, and brought home the Olympic gold medal. After leaving Oxford, he joined the family firm in 1911, two years after Fleming, and soon became a partner. During World War One he was an officer in the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars. He disembarked at Dunkirk with his elder brother and the entire Regiment on 22 September 1914, and rose to the rank of Major. After being demobilized in 1919, Philip worked as a merchant banker, became “one of the best liked and most widely respected members of the City establishment”, and held many directorships. He had a reputation for being “an exceptionally shrewd investor with a real flair for finding winners in the most unlikely situations”, and was noted for his common sense, caution and invariable courtesy to those with whom he had dealings. But his real passion was sport, about which he was “a perfectionist”, and field sports in particular. Like his father and elder brother, he was an excellent shot and enjoyed deer-stalking; he rode with the Bicester and Heythrop Hunts and was Chairman of the latter for several years. His family home was Barton Abbey, Steeple Aston, Oxfordshire. Philip became a JP (1927), High Sheriff of Oxfordshire (1948), and Deputy Lieutenant of Oxfordshire (1949), and in 1951 he founded the PF Charitable Trust. After Robert Fleming left Joyce Grove to him and his sisters, Dorothy Wyfold and Kathleen Hannay, they gifted it collectively to St Mary’s Hospital, Praed Street, Paddington, London W2, in 1940.

Wife and children

In 1906 Valentine married Evelyn (“Eve”) Beatrice Ste Croix Rose (1885–1964) (m. 1906). Evelyn was the sister of an Eton and Magdalen contemporary, Harcourt Gilbey Rose (1876–1952), and Valentine may have met her through an Oxford Commemoration Ball. Her brother was a distinguished oarsman who was later knighted for services to rowing and was the brother-in-law of G.S. Maclagan, another distinguished oarsman. Valentine and Evelyn lived first at 27, Green Street, just off Park Lane, in Mayfair, London W1, until 1911. But Robert Fleming settled more than £250,000 (the equivalent of £14,337,500 in 2005) on his son, and the couple used this money to buy Braziers Park, a mock-Gothic mansion at Ipsden, Oxfordshire, that was four miles away from Joyce Grove. When Valentine became an MP in January 1910, the couple sold their residence in Green Street and moved to Pitt House, a white Georgian mansion on the edge of Hampstead Heath in north-west London that had belonged to the elder Pitt (1708–78). On the outbreak of war Valentine sold Braziers Park and acquired the house and estate of Arnisdale, Inverness-shire, in the Highlands of Scotland. It was an ideal location for deer-stalking and by 1916 Valentine was building a new house there. In 1923 Eve sold Pitt House and moved to Turner’s House, 118, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London SW3.

Evelyn was the beautiful, flamboyant, extravagant daughter of a Berkshire solicitor. She was, according to Andrew Lycett, “the very antithesis of Fleming thrift and heartiness” as she had an artistic temperament and dressed with an exotic garishness. But she was also the granddaughter of two men who, having risen to the very top of their professions, had been knighted in recognition. Her maternal grandfather was Sir Richard Quain (1816–98), a distinguished surgeon and the editor of the Dictionary of Medicine (1882), who had risen from being a tanner’s apprentice to the position of Physician Extraordinary to Queen Victoria; her paternal grandfather was Sir Philip Rose (1816–83), who had been Benjamin Disraeli’s legal adviser. On becoming a widow, Evelyn inherited Pitt House and all Valentine’s horses, carriages and cars outright, but the rest of his large estate, valued at £265,596 gross (the equivalent of £11,436,563 in 2005), was turned into a trust fund whose income, for Evelyn, would drop to a mere £3,000 p.a. if ever she re-married. But although Evelyn kept to the strict terms of the trust, she had an affair with the painter Augustus John (later OM, RA) (1878–1961), by whom she had a daughter, Amaryllis Marie-Louise Fleming in 1925, who did not learn her father’s true identity until she was about 24. Evelyn Fleming is buried in St Bartholemew’s Graveyard, Nettlebed, near Henley, Oxfordshire.

Valentine and Evelyn had four sons:

(1) (Robert) Peter (later Lieutenant-Colonel, OBE) (1907–71); married (1935) Celia Johnson (later DBE) (1908–82); one son, two daughters;

(2) Ian Lancaster (later Commander) (1908–64); married (1952 in Jamaica) Ann Geraldine Mary Rothermere (née Charteris; 1913–81); two sons, one of whom was stillborn (1948) and the other of whom committed suicide (1975);

(3) Richard Evelyn (later Major, MC) (1911–77); married (1938) the Hon. Charmion Hermon-Hodge (1913–2001), the daughter of Roland Hermon-Hodge and therefore a first cousin; three daughters, five sons (three of whom studied at Magdalen);

(4) Michael Valentine Paul (reportedly mentioned in dispatches three times) (1913–40); died as a prisoner of war in Lille on 1 October 1940 of wounds received in action while serving as a Captain with the 4th Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry; married (1934) Letitia Blanche Borthwick (1913–2002); three sons, one daughter; her later name was Thomson after her marriage in 1945 to Major J.C. Thomson (1911–2001), a merchant banker; one son, one daughter (twins).

Valentine Fleming with his four sons; (Robert) Peter standing right; Ian standing left; Richard seated at front; Michael on his father’s knee (c.1915)

(Photo courtesy of the Fleming family)

As a child, (Robert) Peter Fleming suffered from a rare digestive illness which could not be named or cured and which deprived him of his sense of taste and smell. But he was recovering by the time he went to Durnford Preparatory School, near Swanage, Dorset, from 1916 to 1920. From 1920 to 1926 he attended Eton as an Oppidan Scholar, where, like his father, he became a member of the elite society known as “Pop”. He also became Captain of the Oppidans (i.e. head of school except for the 70 Scholars) and editor of the Eton College Chronicle, and he acquired a reputation for his caustic wit. From 1926 to 1929 he was an undergraduate at Christ Church, Oxford, where he obtained a first in English even though he did not much enjoy the academic side of university life. He also acted in a lot of plays – and despite his mother’s disapproval, his lack of talent as an actor, and the imminence of finals, he became President of Oxford University Dramatic Society in his final year. Despite his enthusiasm for the stage, he also became a member of the notoriously “hearty” Bullingdon Club and the editor of Isis.

Peter’s family wanted him to join the family firm after leaving Oxford and sent him to New York for six months, starting in September 1929 to do an apprenticeship with a firm of stockbrokers. But the work bored him to tears and being a lifelong enthusiast of shooting game, he left in December to go on shooting expeditions in Alabama and Guatemala. After these he returned to England, where he made one last attempt to work in the City and several other abortive attempts at finding work before becoming assistant literary editor on The Spectator in the spring of 1931. From mid-September to mid-December 1931 he travelled in China before returning to his job on The Spectator, and from April to November 1932 he took part, as the unpaid special correspondent for The Times, in a poorly organized expedition to Brazil in order to search for an explorer, Colonel Percy Fawcett (b. 1867, d. in or after 1925), the original Indiana Jones, who had disappeared in the Matto Grosso while looking for the lost city of ‘Z’ (El Dorado). The experience led to Brazilian Adventure (1933), his highly entertaining first book, which was translated into many languages, enjoyed great success in Britain and America (not least because it “administered the coup de grace to a boastful type of travel book then fashionable”) and had, in the words of one critic, “set the world laughing”. In June 1933, Peter travelled to China as special correspondent of The Times to report on the civil war that was raging there. He interviewed Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1975), the Commander-in-Chief of the Chinese Nationalists from 1925 until his death, entered territory that was held by the Communists, returned home via Japan and the USA, and used the experience as the basis of his second best-seller, One’s Company (1934). In August 1934 he returned to China, where, for seven months in 1935, he made a 3,500-mile journey by road through Szechwan, Tsaidam and Sinkiang and down into northern India, which resulted in 14 pieces in The Times and his third successful travel book, News from Tartary (1936).

On his return home, in December 1935, Peter married the highly successful actress Celia Johnson (1908–82), whom he had first met in 1929, and in March 1938 the two of them travelled to China to report on the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) and the completion of the Burma Road. Having been a member of the Guards’ Special Reserve since September 1930, Peter joined the Grenadiers on the outbreak of World War Two. Although, for most of the war, he saw little active service in the orthodox sense, he worked, inter alia, for the Special Operations Executive alongside Allix Peter Wilkinson, the future son-in-law of A.H. Villiers, and was given a series of training, undercover and intelligence jobs in Britain, the Balkans and the Far East which, being unconventional, often proved to be extremely dangerous. From 1942 to 1945 he served under Field-Marshal Archibald Wavell (1883–1950; Viceroy of India 1943; from 1947 Earl Wavell) as head of ‘D’ Division in New Delhi and so was in charge of military deception operations throughout south-east Asia. After the Japanese surrender, Peter returned to civilian life as a Lieutenant-Colonel with an OBE (1945), settled at Merrimoles, south Oxfordshire, just off the A4130, which he had had built in 1938–39 on the Nettlebed estate that his uncle Philip, “in an act of great generosity” had given him because none of Valentine’s sons had received anything from Robert Fleming’s will and Sarah Kate, Robert’s widow, had died intestate. Here Peter became an “enlightened and progressive landowner, and moved contentedly in a wide circle of friends”. He became a member of the County Council and commanded the local Territorial Army Battalion. In 1952, following his father and grandfather, he served as High Sheriff of Oxfordshire, and in 1970 he became the County’s Deputy Lord Lieutenant.

Peter’s obituarist summarized his opinion of his post-war life as follows:

If he had wished, he could have had a dazzling career, fully in the public eye. But he preferred a role less familiar to his own generation than it was 50 years earlier: that of an English country gentleman, cultured and enterprising, whose first concern was with his own estate and countryside, but who remained acutely interested in what was astir in the world beyond.

Although Peter continued to write fourth leaders for The Times as Atticus and a column for The Spectator as Strix, he also turned his authorial skills to serious military history and wrote four more successful books: Invasion 1940 (1957), The Siege at Peking (1959), Bayonets to Lhasa: The Full First Account of the British Invasion of Tibet in 1904 (1961), and The Fate of Admiral Kolchak (1963). After the death of his younger brother Ian in 1964, Peter sat on the Board of Glidrose Ltd, the company which managed the literary rights over Ian’s estate. Also, like his father and grandfather, Peter was an excellent shot and returned every autumn to Black Mount estate, Argyllshire, for a shooting holiday. It was here, while he was out grouse-shooting, that he died suddenly in 1971. He and his wife are buried next to one another in the churchyard of St Bartholomew’s, Nettlebed.

Ian Lancaster Fleming was still at preparatory school when his father was killed in action, and was deeply affected by his death. At Eton he showed little academic potential and directed his energies into athletics, for which he had an exceptional talent. In 1925 and 1926 he became only the second Etonian to become Victor Ludorum (Junior and Senior) two years in succession. He was also active in school journalism and edited an ephemeral magazine called The Wyvern. But his academic performance worsened over time; he left Eton a term early under a cloud after being relegated to the Army Class; and although his widowed mother arranged for him to attend the Royal Military College Sandhurst, beginning in 1926, he was totally unsuited to its tough military discipline and left without a commission in 1927. Then, hoping that Ian might find a job in the Diplomatic Service, his mother arranged for him to spend the year 1927/28 in a quasi-finishing school for men in Kitzbühel, Austria, and then to study in Munich and Geneva (1928–31), where he learnt German, French and Russian, read widely, developed a range of unusual tastes, enjoyed himself, and acquired the reputation of being a playboy. But in 1931 he failed the Foreign Office’s competitive examination and in 1932 he was given a job in Reuters Press Agency which, on his own admission, taught him to write and involved him in going to Moscow in order to cover the trial of six British engineers who had been accused of espionage and wrecking (March/April 1933). After leaving Reuters in October 1933, he finally found work in the City – first with a small bank and then with a firm of stockbrokers, where he showed no aptitude even though he remained a Junior Partner there until 1945.

But in May 1939 he was invited to join the Naval Intelligence Division in “Room 39” as part-time personal assistant to Admiral John Henry Godfrey (1888–1970), the Director of Naval Intelligence, and this time he struck lucky. He proved to be not only a very good administrator, but also someone with the quick mind, off-beat imagination and flair that are vital for intelligence work. So he quickly rose from Lieutenant to Commander, was put in charge of the top-secret sub-section known as 17M, and played a key part in several important wartime projects, including Operation Mincemeat, which became famous as “The Man Who Never Was”. But Ian already wanted to write spy novels, and when, after the war, he was employed by the Kemsley (now Thomson) newspaper group as the manager who looked after its correspondents worldwide, his contract allowed him to take three months’ holiday every winter in Jamaica, which he had got to know during an Anglo-American naval conference there in 1942. In 1945 he acquired land on the island’s north coast and had a house built there called Goldeneye after his wartime plan to maintain communications with and defend Gibraltar if Spain should enter the war on the side of the Axis and attempt an invasion. In March 1952 he married his long-standing mistress Ann Rothermere (1913–81) in Jamaica, and Caspar, their only child to survive, was born in London six months later, only to die of a drug overdose in 1975.

In early 1952, Ian wrote Casino Royale, his first 007 novel, which enjoyed great success – probably because its glitz, glamour, sex and non-stop action contrasted so greatly with the dull, lean, repressively routinized world of the 1950s – and from then on, Ian used his annual stay in Jamaica to write a Bond novel a year until his death in 1964. In 1959 he left regular newspaper work to devote himself to writing fiction, but in April 1961 he suffered a heart attack that was probably connected with personal, professional and legal problems. Three months later, however, he signed a contract with the film producers Albert R. (“Cubby”) Broccoli (1909–96) and Herschel (“Harry”) Saltzman (1915–94): the first Bond film, Dr No, starring Sean Connery (b. 1930), came out in autumn 1962 and was immediately successful. Nevertheless, his heavy smoking and drinking worsened his heart condition and almost certainly contributed to his death in hospital in Canterbury in August 1964. He is buried in St James’s Churchyard, Sevenhampton, near Highworth, Swindon, Wiltshire. During his lifetime alone, Ian sold 30 million books; it is estimated that 100 million have been sold worldwide; and by 2000 the Bond films had made over $3 billion in box-office returns and £400 million in profits, not counting the sales of videos, DVDs etc. Unlike his father, grandfather, uncle, elder brother and two younger brothers, Ian disliked field sports and Scotland, preferred golf, bridge and swimming, and avoided family gatherings whenever possible, especially at Christmas.

Richard Evelyn Fleming was educated at Eton from 1924 to 1930, where he was Master of Eton Beagles, and at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was a Commoner from 1930 to 1933 and graduated with a 2nd class degree in PPE. After a short apprenticeship with Barings, he joined the family firm and soon became a Director. His obituarist speaks of his “remarkable ability and energy and his infectious good humour”, and suggests that these qualities helped Flemings to extend its activities in Britain, the USA, the Middle East and Hong Kong. During World War Two he served as an officer in the Lovat Scouts and the Seaforth Highlanders, gained the rank of Major, was wounded in 1944, and was awarded the MC (London Gazette, no. 36,850, 19 December 1944, p. 5,854) and the TD. After the war, he succeeded his uncle Philip as Chairman of Flemings and was Director of several investment trust companies, Barclays Bank and Sun Alliance Insurance Company; he was also Chairman of Pilgrim Trust. As he was devoted to Scotland, he went on holiday every year to Black Mount in order to stalk, shoot and fish. He also hunted with the Heythrop Hunt and the Oxford Beagles, “who he rescued from disaster when university support was withdrawn”. His obituarist described him as a generous friend, who was respected for his fairness, good judgement, and personal concern, and concluded: “Never was there a more upright, courageous and inspiring personality.”

Although he was the youngest of the four brothers, Michael Valentine Paul Fleming seems to have combined the virtues of the other three. Like Ian he was a keen golfer, and like Peter and Richard he was an excellent shot. One obituarist wrote:

He was the good companion of men of all ages: he enjoyed the good things of life and appreciated them for their quality, and for the happiness they gave to his friends. Besides the memory we all carry with us of Michael as the happy host, there comes back the picture of him with gun in hand – and he was quick on the trigger and accurate – and of that happy, carefree figure striding the hills, ever keen and tireless.

Like Ian Fleming, he was characterized by charm, good looks, gaiety and humour, and like Peter Fleming, he had “a nimble mind and tongue”. He had been a keen member of the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars (Territorial Force) ever since leaving Eton, but in 1937 he moved across to the 4th (Territorial Army) Battalion of the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry since his “stern sense of duty” persuaded him that it was there that competent officers were most needed, and he raised a platoon from people who lived around the family home at Nettlebed. He turned into an excellent and well-respected officer, of whom a brother officer wrote posthumously: “In the regiment his powers of leadership grew in a most striking but effortless way, as he adapted himself to the new outlook and occupations which life in the Army impressed on him.” Another brother officer wrote:

He was always receptive, always resourceful, always vigorous. I can never remember an occasion on which he looked bored or baffled, or any movement of his that even remotely suggested apathy, or lethargy, or fatigue. He brought with him everywhere quickness of thought and power of decision, and he could rapidly convert his decision into action. His outstanding feature was always his irrepressible vitality.

The 4th (TA) Battalion went to France in January 1940 as part of 145th Brigade, 48th (South Midland) Division. During the two weeks of fighting which began on 10 May, Michael was reportedly mentioned in dispatches three times (London Gazette, no. 35,126, 1 April 1941, p. 1,951), but his Battalion was gradually pushed back westwards and encircled by the Germans at Watou, just north of the Franco-Belgian border, where most of the survivors, including the wounded Michael, were taken prisoner. After Michael’s death from wounds in Lille, where he is buried, one of his obituarists concluded that his loss left one “not merely with a permanent sense of bitter personal loss, but with dumb fury at the crude waste of war”.

Fleming’s wife Evelyn was a gifted violinist, and Amaryllis Fleming (1925–1999), inherited her mother’s musical ability – although Evelyn forbade her daughter to follow her in the violin and directed her towards the cello when she was nine. Amaryllis began to play the piano when she was three and made her first radio broadcast – on BBC Children’s Hour – when she was only 15. In 1943 she won a scholarship to the Royal College, where she studied the cello with Ivor James (1882–1963) of the Menges Quartet and John Keighley Snowden (1892–1958), and won all the College prizes. She appeared in public for the first time in 1944, when she played Elgar’s Cello Concerto at Newbury with the augmented Newbury String Players. After World War Two she took lessons with Pierre Fournier (1906–86) in Paris and later said of him that “he opened my eyes to the immense possibilities of colour, nuance and phrasing”, and in 1950 she visited Prades in the French Alps to work with Pablo Casals (1876–1973) on Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A minor (1850).

In 1949, together with the former child prodigy, the violinist Alan Loveday (1928–2016) and the pianist Peggy Gray (dates unknown), she founded the Loveday Trio; in 1951 she played for the first time with the Fidelio Ensemble; in 1952 she won the Queen’s Prize and performed in London for the first time; in 1953 she gave her first recital with the pianist Gerald Moore (1899–1987) and performed Elgar’s Cello Concerto with Sir John Barbirolli (1899–1976) and the Hallé Orchestra at a Promenade Concert; and in 1955 she and the pianist Lamar Crowcon (dates unknown) won the Munich international competition for cello and piano. In the late 1950s she developed a particular interest in the music of the Baroque and acquired a five-string cello that had been made by a member of the Amati family from Cremona in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. In 1968 she, together with the viola player Kenneth Essex (dates unknown) and the violinist Granville Jones (1922–68), formed the Fleming String Trio; and in 1974 she was appointed Professor at the Royal College of Music. She suffered a stroke in 1993, which left her unable to play the cello, but she continued to teach at the Royal College of Music and Wells Cathedral School. Described as a “flamboyant, extrovert person” and an “extraordinary all-round intelligent person” with an “engaging personality”, she was an exceptional teacher with a prodigious memory for the strengths and weaknesses of her pupils, but left relatively few recordings because of her perfectionism. In the early 1990s, after a trip to Bhutan, she was drawn to Eastern mysticism, meeting the Dalai Lama in spring 1997.

Education and professional life

Valentine, who, according to John Pearson, was “one of those rare, slightly baffling Edwardian figures of whom nothing but good is ever spoken”, attended Mr Hawtrey’s Preparatory School, Westgate-on-Sea, Kent, from c.1889 to 1896. The school had been founded in 1869 at Aldin House, Slough, by the Reverend John Hawtrey (1850–1925); it was known as St Michael’s School from 1869 to 1925; it moved to Westgate-on-Sea in 1883; and it existed in various locations until it merged with Cheam Preparatory School, Headley, Berkshire, in 1994 (cf. H.W. Garton and E.C. Garton). From 1896 to 1900 Valentine attended Eton College, where, like Peter after him, he became a member of the élite society known as “Pop” and acquired a reputation for his outstanding personal qualities. When, on 28 May 1904, he was singled out by the Oxford University student newspaper The Isis as its 269th “Isis Idol”, the anonymous author of the accompanying panegyric claimed that while at Eton, he was “presently engaged in all the various fields for energy which that establishment offers” and although that may be something of an exaggeration, he was certainly a good all-rounder and an excellent oarsman who rowed for the Eton VIII in 1900.

He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1900, having passed Responsions in the Hilary and Michaelmas Terms of 1900, and here, according to the Isis idolator, “under [Magdalen’s] kindly shelter [he] has enjoyed a career of unbroken success in the world of letters, sport, and good fellowship”. He passed the First Public Examination (Scripture and Jurisprudence) in Michaelmas Term 1901, was awarded a 3rd in Modern History on 2 August 1904, and took his BA on 22 June 1905. “But”, his encomiast continued with a certain irony, despite his academic successes “he is no bookworm – rather the reverse”, being a good cricketer, an enthusiastic and proficient player of tennis, squash and billiards, and “a daring and successful player at Beggar My Neighbour”. In 1902, Valentine rowed with G.C.B. James in the Oxford University Boat Club IVs and the OUBC Trial VIII and might have made the Blue Boat had he not developed a boil at the last minute. He was Magdalen’s Captain of Boats 1903–04 and he was in the College VIII that came Second on the River in 1903 and 1904. In summer 1904 he, together with James, helped the Magdalen VIII to win the Ladies’ Challenge Plate at Henley for the first and last time: the same VIII also tried for the Visitors’ Challenge Cup but lost. The Captain noted in his Book:

Fleming is heavy with his hands and lets his slide go at the beginning. A very hard worker and was invaluable in the middle of the boat. His general good humour and light-hearted badinage helped the crew in several trying periods of depression.

When Magdalen’s 1st VIII were competing in the Henley Regatta in mid-June 1906, the part played by Valentine in the history of the Magdalen College Boat Club was remembered by a note in the Captain’s Book:

The warmest thanks of the Boat Club and the College are due to Mr. and Mrs. Fleming, whose son Mr. Val Fleming was a wellknown [sic] Magdalen oarsman, being captain in 1903. During practice and the Regatta they kindly invited the crew to make their house at Nettlebed their headquarters. We were driven down to the river each day in motors, and had the advantage of the cooler air on the hill of Nettlebed on returning in the evening. Everything was done to make the crew comfortable by our hosts, to whom we and the College have every reason to be most grateful.

On 16 December 1907 Valentine’s prowess as an oarsman was recognized when he was made a Steward of the Henley Royal Regatta.

But according to The Isis, if one really wanted to understand Valentine’s love of field sports,

one must see him in his sanctum at Longwall House. The skyline – if we may use the metaphor – is broken by a forest of horns – royals and ten-pointers enough to have depleted Scotland. Below are smaller trophies, the roebuck, the fox, and what an admiring lady has described as “a lovely rabbit”, the victim of the New College and Magdalen Beagles. Looking round his walls[,] we are transported by [Archibald] Thorburn [1860–1935; a Scottish artist specializing in birds and animals] and Cecil Aldin [1870–1935; an English artist specializing in drawings and sketches of animals, sports and rural life] from one sporting scene to another: now we have cleared a monstrous obstacle and are in the same field as the hounds; now we are holding well in front of a driven blackcock; in another moment we must follow a twenty-pounder best pace down the stream. Fortunately suitable weapons are ready to our hands, for the Farlows are stacked in the corner and the Purdeys peep out beneath the sofa. A nodding acquaintance with the classics is indicated by [John Guille] Millais’ “Red Deer” and [Augustus] Grimble’s “Salmon Rivers” in his book-case.

Nor, the writer continued,

have his social successes been less numerous – indeed[,] popularity is assured for one who is literally all things to all men. Thus he is President of the Junior Common Room and Librarian of the History Library; he is an inevitable member of every committee, and, what is more, an energetic member. His versatile spirit revolts at the specialization of the present day; for him the question of the moment is always first – whether he is discussing the advantages of a classical education with the Deans or the merits of the Jock Scott [an artificial fly used by fishermen] with his gillie. His philosophy of life has been the easy creed of “Carpe diem” and long may he continue to practise it! We can leave him with no better wish than that it may bring him the same success in after life that it has during his “Varsity career”.

According to Andrew Lycett, Valentine emerged from Magdalen “with a degree in history and the manners and bearing of a perfect English gentleman”. After graduation, he decided to train as a barrister, and on 12 January 1906 he was awarded a 3rd in the first part of the Bar Exams (Evidence, Procedure and Criminal Law), followed by another 3rd in the second part of the Bar Exams on 12 January 1907. But although he was called to the Bar later on in the same year, he never practised and was taken into his father’s merchant banking firm, Robert Fleming & Co., of Crosby Square, London EC2, of which he became a partner in 1909. A member of the right-wing Primrose League and an opponent of Home Rule for Ireland, he was accepted as Unionist candidate for the Henley Division of South Oxfordshire on 18 December 1909, and on 15 January 1910 he defeated the Liberal Philip Morrell (1870–1943), the husband of Lady Otteline Morrell (1873–1938), who had come in on the landslide election of 1906, by 5,340 to 3,701 votes, a majority of 1,639.

While an MP, between 10 March 1910 and 1 November 1913, Valentine made a total of 32 interventions, two of which were speeches and the rest questions, predominantly on rural Scotland, the operation of the Poor Law, and local issues in rural Oxfordshire. One of his speeches (13 July 1910), in which he seconded the amendment for rejecting the Reading Borough Extension Bill, was a swingeing attack on the Borough of Reading for trying to annexe part of Oxfordshire, the nearby town of Caversham. Another (13 March 1912) was a passionate critique of the “ludicrously inadequate” opportunities for the training and recruiting of Territorial units, the smallness of British Territorial Forces in comparison with the armies of other major European powers, and a plea for the institution of national military service. Because Valentine clearly knew what he was talking about – he was, in Andrew Lycett’s estimation, “one of the best trained volunteer officers in the British Expeditionary Force when he set off for France” – he was asked to serve on the Paul Committee, whose remit was to investigate and report on the administration and financing of the Territorial Forces. Valentine was a very good but reticent speaker, and by April 1913 it was rumoured that the pressures caused by the worldwide success of his family’s business were moving him to think of resignation at the end of the current Parliament, and his constituency even went so far as to find a prospective successor – Captain (later Major) Henry Nevile Fane (1895–1947) of the Coldstream Guards. During the war, Fleming was, however, sometimes recalled from France to take part in a parliamentary debate.

“Valentine Fleming … was most earnest and sincere in his desire to make things better for the great body of the people, and had cleared his mind of all particularist tendencies.”

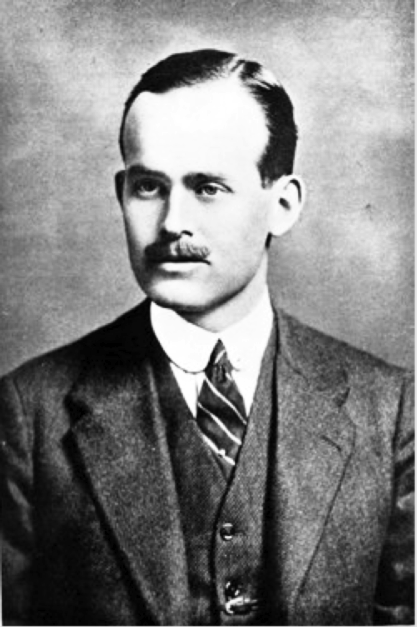

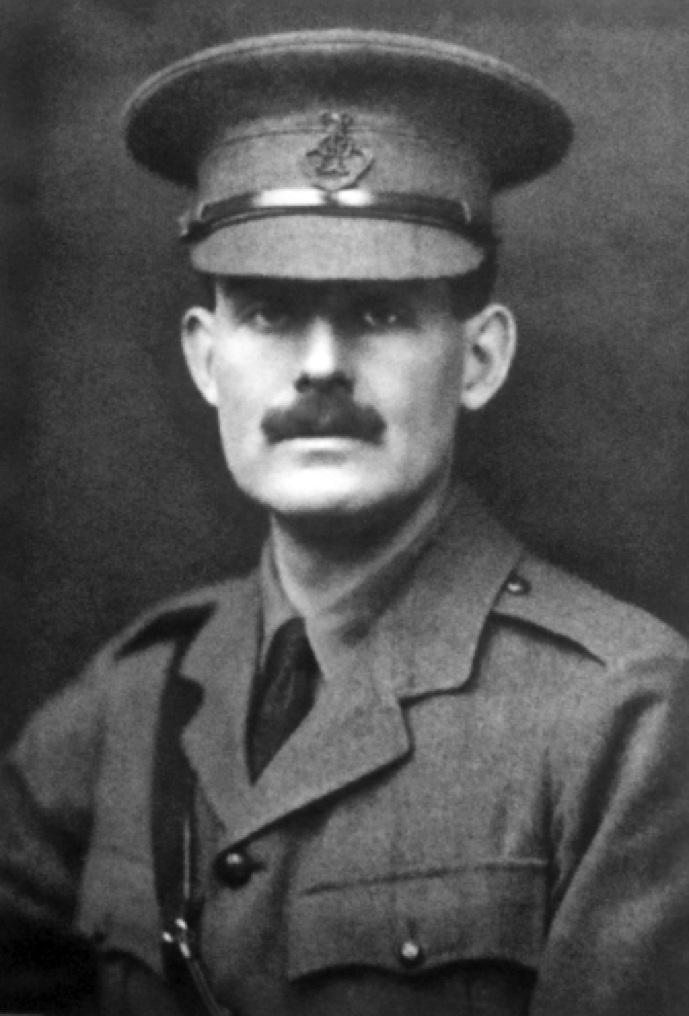

Valentine Fleming, DSO MP (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

But Fleming’s friend Winston Churchill saw the situation rather differently and put it as follows in his obituary of 25 May 1917:

Valentine Fleming was one of those younger Conservatives who easily and naturally combine loyalty to party ties with a broad liberal outlook upon affairs and a total absence of class prejudice. He was most earnest and sincere in his desire to make things better for the great body of the people, and had cleared his mind of all particularist tendencies. He was a man of thoughtful and tolerant opinions, which were not the less strongly or clearly held because they were not loudly or frequently asserted. The violence of faction and the fierce tumults which swayed our political life up to the very threshold of the Great War, caused him a keen distress. He could not share the extravagant passions with which the rival parties confronted each other. He felt acutely that neither was wholly right in policy and that both were wrong in mood. Although he could probably have held the Henley Division as long as he cared to fight it, he decided to withdraw from public life rather than become involved in conflicts whose bitterness seemed so far to exceed the practical issues at stake. Friends were not wanting on both sides of the House to urge him to remain and to encourage him to display the solid abilities he possessed. It is possible we should have prevailed. He shared the hopes to which so many of his generation respond of a better, fairer, more efficient public life and Parliamentary system rising out of these trials.

But events have pursued a different course.

A week later, in an obituary where Churchill’s influence is very evident, President Warren said:

Both in his election speeches and in his career in the House, Fleming showed a singular and too rare temper. A man of business rather than a student, and of affairs rather than letters, he yet had a special capacity for acquiring and presenting what was essentially valuable in political ideas and ideals. His natural courtesy, agreeable address, and bright common sense, made him singularly acceptable, and few men of his age were more persuasive or effective. And this was the more remarkable because he eschewed party, and regarded its bickerings and battles as often a somewhat squalid waste of time. He had indeed, though neither pensive nor melancholy, a dash in him of Falkland, and had announced his intention of retiring from politics and devoting himself to the life of business and the country, for which he was so well fitted.

But the outbreak of war frustrated his intentions and Fleming had to remain an MP in absentia until his death in 1917.

As The Isis article makes clear, Fleming was passionate about field sports: he excelled at them all and kept a pack of beagles, followed by one of basset-hounds. Like his father, he enjoyed the Black Mount estate, and his proficiency with a rifle enabled him to represent the House of Commons in July 1910 when it defeated the Lords in the Vizianagram Challenge Cups: one of his opponents was Earl Stanhope (see R.P. Stanhope). Fleming was also a keen billiards player, and in 1912 he contested the final of the American Billiards Challenge. In 1916, he was elected Fellow of the Zoological Society of London.

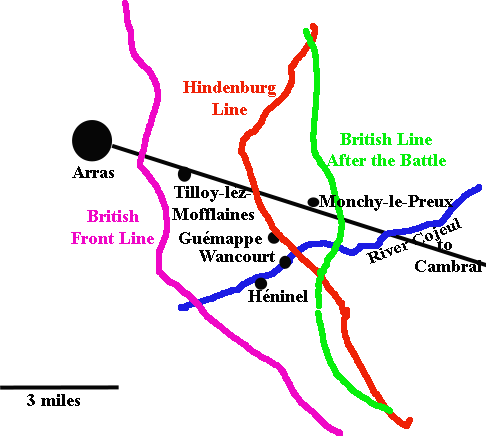

Military and war service

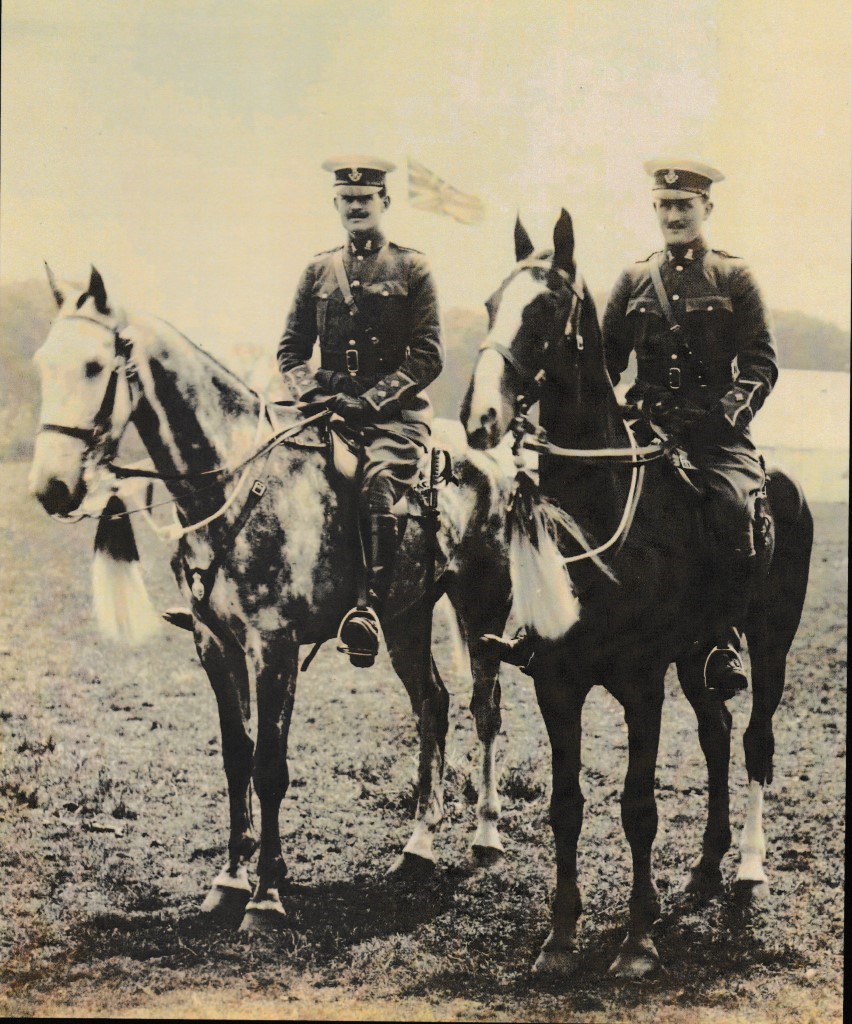

Lieutenant Valentine Fleming (c.1909)

(Used with permission from Ian Fleming Images © Fleming Family)

Fleming was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Imperial Yeomanry on 15 October 1904 and promoted Lieutenant on 24 April 1909. Although he became an energetic MP just eight months later, he found the time to learn his work as an officer in the 1/1st Oxfordshire Yeomanry (Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars: QOOH) (Territorial Force), Winston Churchill’s Regiment since 1902, and, according to Churchill’s obituary, went on most of the courses of instruction that were available.

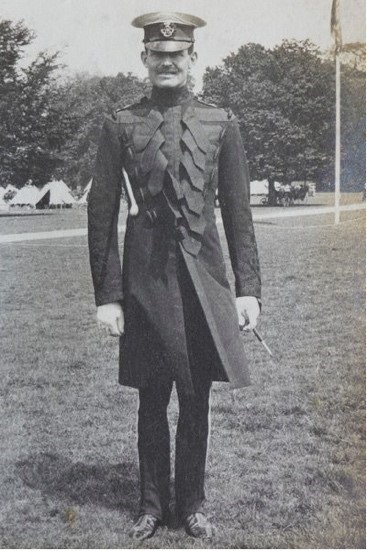

Members of the 1/1st Oxfordshire Yeomanry, part of a group photograph; Winston Churchill seated in the centre; Valentine Fleming 3rd row right

(With permission from Ian Fleming Images © Fleming Family)

Like many Yeomanry officers, Fleming was “drawn from the land-owners and country gentlemen of the district”, and his commission was transferred to the QOOH on 1 April 1908. He was promoted Captain (Territorial Commission) on 6 May 1909.

Thanks to his pre-war experience and willingness to undergo training, Valentine was, when war broke out, not only the best-turned-out officer in his Regiment, but also a very capable soldier. He was mobilized with the rest of the Regiment at Oxford on 4 August 1914 as part of the 2nd South Midland Mounted Brigade in the 1st Mounted Division. After about four weeks training in England, on 22 September 1914 he and Philip disembarked at Dunkirk with their Regiment – comprising 26 officers and c.525 other ranks (ORs) – the first Territorial Force unit to see active service. Fleming was the second-in-command of his Regiment’s ‘C’ Squadron, and the Regiment’s Adjutant was the slightly younger Guy Bonham-Carter, with whom he had overlapped at Magdalen from 1902 to 1904. Finally, Adrian Wentworth Keith-Falconer (1888–1959) also landed with the QOOH on the above date: another brother officer who managed to survive the war, wrote the regimental history, and penned what is probably Fleming’s most fulsome obituary.

The Regiment stayed at Dunkirk until 29 September 1914, when it marched 23 miles south-westwards to Hazebrouck, where it trained in infantry tactics. It then patrolled in the area of Nieppe/Strazeele and Bailleul/Berthen, i.e. along the Franco-Belgian border, until 6 October, when it retired to Bergues, seven miles south-east of Dunkirk, where it spent two nights in billets. On 8 October it marched to Malo-les-Bains, a suburb of Dunkirk, where it did further training until 15 October. On 17 October it was billeted in the infantry barracks at St-Omer and did more training in this general area until 30 October. During this period, Fleming was one of the two officers in the Regiment who preferred to live in tents, like their men, rather than in hotels, like their brother officers.). On 9 October 1914, the Division had become part of the two-Division (later three-Division) Cavalry Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Edmund Allenby (1861–1936), who is now best remembered for the part he played in the war against the Turks in Palestine. From 31 October until 11 November 1914 the QOOH was part of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade in the 1st Cavalry Division (formed on 13 September 1914). On 1 December 1914 Fleming’s captaincy was upgraded from being a Territorial to a Regular commission (with effect from 19 August 1914: London Gazette, no. 28,873, 18 August 1914, p. 6,506); his promotion to Major (Territorial Commission) soon followed (with effect from 2 November 1914: LG, no. 28,991, p. 10,150). About this time, Fleming was given command of ‘C’ Squadron, with Philip as his second-in-command.

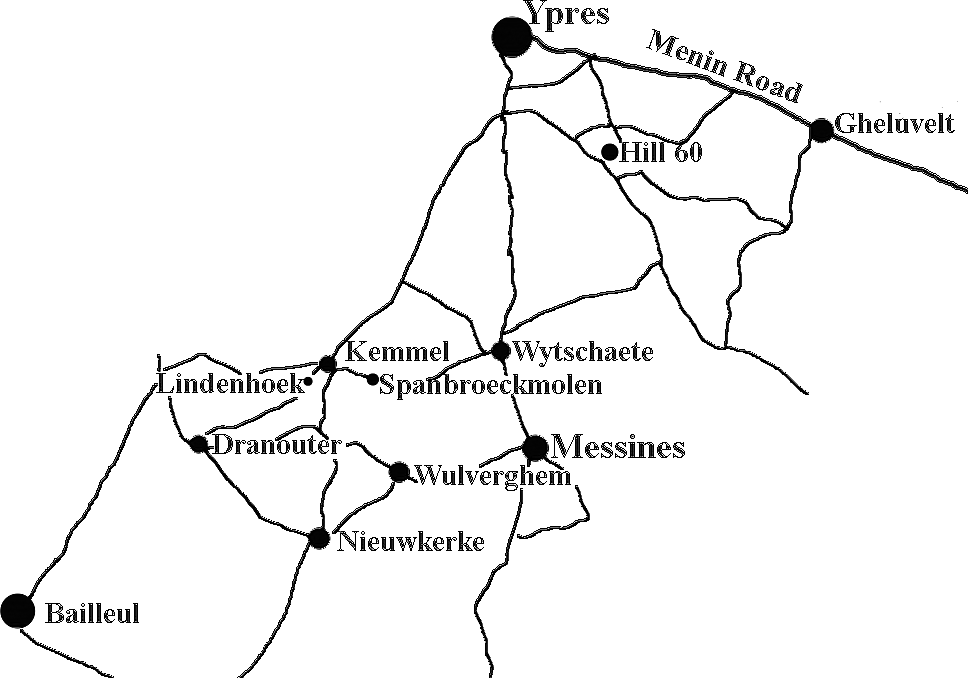

Although the first Battle of Ypres began on 19 October and ended on 22 November 1914, the serious fighting for control of the ridge linking Wytschaete and Messines began on 21 October, when the Germans began their attempt to break through the British front line and into the flatlands beyond, and advance south-westwards in order to capture the major Channel ports, notably Calais and Boulogne. The British Expeditionary Force responded by trying to push further north-eastwards into Belgium and outflank the advancing Germans. The crux of the Battle came about at first light on 30 October, when the German artillery began to bombard the British positions for an hour and then advanced towards Ypres along the Menin road. Then, at about 16.00 hours, they finally broke through to the strategically important crossroads at Gheluvelt (Geluveld), about four miles due east of Ypres. Earlier that day the QOOH had been ordered to saddle up in the pouring rain and march the c.21 miles south-eastwards to Nieuwkerke (Neuve-Église), just over the border in Belgium.

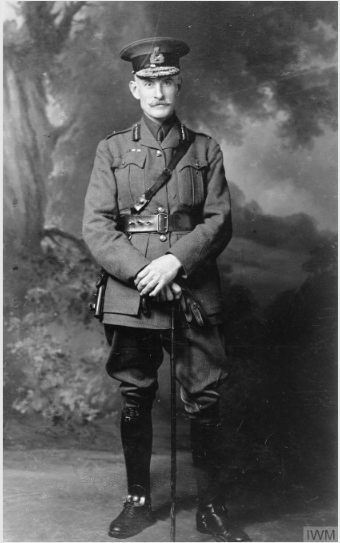

The QOOH arrived at Nieuwkerke at 06.45 hours on 31 October and its Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Dugdale (1869–1941; later CMG, DSO), reported as ordered to Major-General Sir Henry de Beauvoir de Lisle (1864–1955). De Lisle, who had taken over from General Allenby as the General Officer Commanding the 1st Cavalry Division on 12 October, then ordered the Regiment to move to the small town of Messines (Mesen) (1,400 inhabitants), some two miles east of Wulverghem and five miles south of Ypres. When it arrived here at about 08.30 hours, it became part of the 1st Cavalry Division, which had been tasked by General Haig with the defence of Messines, whose importance throughout the war lay in its commanding position. Rising c.150 feet above the surrounding countryside, the town and the ridge linking it with Wytschaete formed a natural hindrance to any body of troops that wished to pass south of Ypres from east to west.

Major General Sir Henry de Beauvoir de Lisle, KCB, DSO (1864–1955; GOC 1st Cavalry Division with effect from 12 October 1914)

(Photo ©IWM: HU 94721)

The Grand Place of Messines before the fighting that took place there in late October / early November 1914

The QOOH began by riding to the bottom of the hill that was surmounted by Messines, then dismounted and began to dig a long line of Reserve trenches. But it was very soon ordered forward to the front-line trenches, and according to an unfinished letter that Fleming wrote to his family a few days later, probably on 5 November 1914:

We had to throw down our tools, leave greatcoats and everything and start off to take a line of advanced trenches which were supposed to have been dug as the troops on our left had begun to fall back. Off we went[,] each squadron on its own front extended and in about 300 yards we began to come under the German shell fire, not very heavy but very frightening. However[,] the men stuck it very well when they found they were not hit, and we went on to find when we got to the crest of the hill that only about enough trench had been dug for one squadron, so we disposed ourselves as well as we could behind ditches, trees, etc. and lay there firing occasional shots at distant German infantry. Meanwhile the village on our left [possibly Blauweroorhoek] was burning like mad and wounded men kept coming back saying the troops on our left were being driven back, so it was anxious, especially as about midday our area was very heavily shelled for about four hours. But we found it was all right and were very lucky only to have four men wounded [the Regiment’s first casualties]. There we stayed until 11.30 p.m. [on 31 October 1914]. They looked like attacking at dusk but did not. At 11.30 we were relieved by some infantry, marched about three miles back, and had just started to prepare food in a barn, when out we had to go again and relieve some other cavalry who had been holding a barricade in M[essines]. This was very exciting, the whole place burning like a torch, and the Germans brought a little gun up under the smoke with which they fired at the barricade to try and set it alight. However the street was too straight and whenever the smoke lifted[,] our maxim sorted them up [sic] and they did not try our left flank which was the weak one. Then[,] at 5.30 a.m. [on 1 November 1914] we were relieved in our turn and marched back to N[euve] É[glise] very weary and famished: two nights and one whole day very hard at work, no sleep, very cold at night (no time to get out and put on coats and think things). Very cold and very hungry [we] arrived at N[euve] É[glise]: about 7 a.m. [on 1 November] fires just started, everyone waiting for tea when up galloped de L[isle. He told us that] the Germans had got through the left [flank of the British line] just an hour after we left. Out we had to turn leaving everything in the road and do a long advance, part of it under rifle (not shell) fire and then fall back to a line of trenches the digging of which our advance had covered. The Germans did not come on with the attack but started very heavy shell fire which they kept up till dark.

The Regimental War Diary confirms all this, and at 07.00 hours on 1 November the two squadrons that had previously been manning the barricades at Messines set off north-eastwards along what is now the N134 from Wulverghem for a couple of miles towards the Wytschaete–Messines Ridge, where the Germans were reported to have broken through the British line. But when the reconnoitring party arrived at the Steenebeek, a brook which crosses the N134 just before Messines Hill begins to rise up steeply from the countryside, they heard that the British Cavalry on their right – probably the 5th (Princess Charlotte of Wales’s) Dragoon Guards – had received orders to retire from the hill-top town. So the QOOH tried to support them by means of long-range rifle fire directed at the enemy troops who they could see coming over the ridge. But when they tried to retire themselves, they came under rifle and machine-gun fire that killed Acting Major Brian Charles Baskerville Molloy (1876–1914) and wounded one OR. For the rest of the day the two squadrons stayed in their trenches along the Wulverghem–Wytschaete road (N365) until they were relieved at about 20.00 hours and were able to return to their billets in Wulverghem. Valentine Fleming’s unfinished letter picks up the narrative at precisely this point:

At dark [on 1 November] we were able to crawl back by reliefs out of the trenches and get some bread and bully beef, and at midnight were relieved and got three hours sleep exactly and some hot tea and coffee. Then off again and spent the next morning [2 November 1914] digging a new line of Reserve trenches [to the east of Lindenhoek, just south of Mount Kemmel and about nine miles south-west of Ypres]. Just as we had finished these (5ft. deep[,] 2ft. 6 in. wide, traverses etc. etc., and very hard work) off we had to march again to relieve some Regulars in the advanced trenches [i.e. the front line,]. We were there all night [2/3 November 1914]; between the 9th [Queen’s Royal] Lancers and the 4th [Royal Irish] Dragoon Guards – no sleep of course) and all next day [3 November 1914]. That next day was very hot, the most terrific shell fire. The troops on our left had a vile time and we had to support them in the afternoon [at the crossroads on the Wulverghem–Wytschaete road] as well as look after ourselves and then at night [3/4 November 1914] occupy their trenches till reliefs came – which they did at 11.30 [3 November 1914]; and at 2.30 a.m. yesterday morning [4 November 1914] we got to sleep on the floor of a cottage [one OR killed in actionand one OR wounded]. Woke up at 10 [on 4 November 1914], had a huge meal, and then moved into three farms where we had last night [4/5 November 1914] and today [5 November 1914] to rest, and did we sleep and eat last night and today? – I don’t think.

So when, during the early evening of 5 November 1914, the extremely fierce fighting of the previous six days came to an end, the Germans, at considerable cost, were in possession of Wytschaete, Messines and the ridge that joined them, and held a front line that extended for about five-and-a-half miles south-westwards from Hill 60 in the north to Spanbroekmolen in the south. But, as Cave and Sheldon make it clear, these places had not originally been their final objective, but simply an intermediate part of their strategy to break through south of Ypres in the direction of the Channel ports (p. 119). Moreover, despite Valentine Fleming’s graphic letters, the QOOH had been used mainly as a Reserve unit during the fighting and general withdrawal south-westwards, and had not suffered losses that were comparable to those of other British and French battalions and regiments. But the Germans had also taken very heavy losses and were nearly out of ammunition, two factors that helped the front line to stabilize. Nevertheless, the Germans held the newly acquired high ground until 7 June 1917, when, at 03.10 hrs, they were blown off the ridge by the detonation over 20 seconds of 19 huge mines containing 454 tonnes of ammonal and gun cotton, probably the largest man-made explosion before the advent of nuclear weapons, which killed c.10,000 Germans.

By 6 November 1914, the QOOH was secure in its new billets in farms between Dranouter (still in Belgium) and Bailleul (just in France), and could now rest. But these were by no means ideal, and one of Fleming’s brother officers who survived the war described them as follows:

Our new billets were, I think, the worst we ever had. The farms were small and filthy beyond words, and the inhabitants equally disagreeable. To add to our discomforts the weather, which hitherto, though cold at night, had been generally fine and sunny, now took a turn for the worse, and soon settled down to rain almost incessantly for weeks. The horses, picketed out in the field, were over their fetlocks in mud; the men, once wet – and they had to go out in the rain at least three times a day to water and feed – never got properly dry, and even the officers were none too comfortable. For example, in ‘D’ Squadron the officers ate and washed and slept in one small dirty brick-floored room, with a fireplace, but no possibility of lighting a fire because the chimney had been bricked in. Next door, in the kitchen, ten sergeants, four officers’ servants, the sergeants’ cook, and a number of exceedingly dirty and unpleasant inhabitants were herded together while the servants struggled with the inhabitants for a place on the fire to cook. And of course everybody was smoking, and the windows [were] all shut to keep out the wind and rain. The atmosphere may be imagined, but anyway it was warm.

Fleming continued his unfinished letter of about 5 November 1914 by commenting on his recent experience of warfare:

Well, it was an introduction to war a good deal more abrupt and arduous than we had quite bargained for. The idea was that we should find gallopers and orderlies for the various generals and act as reserves etc., but the situation [on] the night we came up was so anxious and they had lost so heavily [that] they had to use us properly. I think we may fairly claim to have done well. De Lisle congratulated the Colonel on the behaviour of the regiment [sic] and our Brigadier (2nd Cavalry Brigade) Molyneux was really quite effusive, and all the regular soldiers said they never thought that yeomanry would have stood the shell fire, which during the last three days is said to have been the heaviest of the whole war. The Kaiser himself was behind the Germans at this point in the line (M[essines]) [he was watching the events of 1/2 November]. They knew the line was thin and if we had got out and wobbled when we began to feel it really badly it would have been very serious because there were no, or practically no, supports at that particular moment and place. But we were extraordinarily lucky to lose so few men. Poor Brian [Molloy] and two men killed, seven wounded, and half a dozen knocked up from hunger, fatigue, etc. Poor Brian – I am sorry. We had all got so fond of him and he was a very brave creature.

Captain Brian Charles Baskerville Molloy (1876–1914), killed in action 1 November 1914, aged 38, while serving with the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars; no known grave; commemorated on Panel 5 of the Menin Gate Memorial, Ypres

(Photo © IWM: HU 125794)

If we had lost a lot of men the first day[,] it would have made a lot of difference, but when they found [that] these huge shells fell so often and hit so few[,] they got steadied and stuck it out very well. It is impossible to describe the din and destruction that these shells make, no person could find words to do it. It’s the moral effect rather than the actual, because one shrapnel shell which is filled with bullets might do a lot of harm one hundred yards from its fall, but these “Hairy Marys” as they are politely dubbed, though if they hit they of course completely eradicate, may fall within two yards of a man lying down and only frighten him, but the holes they make and the columns of earth and stone they send up and the ear-splitting crashes of the things are very shaking. It’s very cold at night in the trenches, especially if it’s wet, and oh so sleepy. I personally cannot sleep until anything that’s going on is over; some can lie down and sleep anywhere for half an hour, but not me. I am afraid [we suffered] very heavy losses the last week. One of the most pathetic things in the actual battle area is the wretched animals. All the farms are either shelled to atoms or abandoned, the fences broken, cows, horses, pigs, dogs, etc. straying everywhere, so wretched and not knowing what to do. I picked up a kitten which came out of a burning barn at M[essines] the night we were at the barricade and took it into N[euve] É[glise] but in the night it went away. A goat came running up and down the line of our trenches bleating one night – It was [a] very clear moon and the Germans started sniping it, so we pulled it by the leg into the trench and milked it. I am clean and replete today but [letter breaks off].

The QOOH spent 6/7 November in the trenches between Wulverghem and Wytschaete, from 14.30 hours onwards on the following day in billets north-west of Bailleul, and 9 November in Reserve on the Dranouter–Neuve-Ểglise road. On 10 November, the QOOH’s no. 1 Squadron, together with men from the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards, and two other troops of the QOOH plus elements of the 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers, were in the trenches at Wulverghem, about half-a-mile west of the Steenebeek brook. Here Fleming wrote a long and remarkable letter to his friend Winston Churchill in which he described the “first week’s serious fighting” in a manner that may remind the modern reader of a huge Expressionist canvas by Otto Dix (1891–1969).

It begins: “Well [–] you will have heard of our first week’s serious fighting. Let me give you some general impressions of this outstanding conflict:–”

1. First and most impressive the absolutely indescribable ravages of modern artillery fire, not only upon all men, animals and buildings within its zone, but upon the very face of nature itself. Imagine a broad belt, ten miles or so in width, stretching from the Channel to the German frontier near Basle, which is positively littered with the bodies of men and scarified with their rude graves; in which farms, villages, and cottages are shapeless heaps of blackened masonry; in which fields, roads and trees are pitted and torn and twisted by shells and disfigured by dead horses, cattle, sheep and goats, scattered in every attitude of repulsive distortion and dismemberment. Day and night in this area are made hideous by the incessant crash and whistle and roar of every sort of projectile, by sinister columns of smoke and flame, by the cries of wounded men, by the piteous calls of animals of all sorts, abandoned, starved, perhaps wounded. Along this terrain of death stretch more or less parallel to each other lines and lines of trenches, some 200, some 1,000 yards apart, hardly visible except to the aeroplanes which continually hover over them [–] menacing and uncanny harbingers of fresh showers of destruction. In these trenches crowd lines of men, in brown or grey or blue, coated with mud, unshaven, hollow-eyed with the continual strain[,] unable to reply to the everlasting rain of shells hurled at them from 3, 4, 5 or more miles away and positively welcoming an infantry attack from one side or the other as a chance of meeting and matching themselves against humanassailants and not against invisible, irresistible machines, the outcome of an ingenuity which even you and I would be in agreement in considering unproductive from every point of view. Behind these trenches, a long way behind, come the guns hidden in hedgerows and copses, dug into emplacements, concealed in every imaginable way from the aeroplanes which give their range; behind them again come the reserves and supports and masses of cavalry, or at least their horses, for all the English cavalry are in the trenches; behind them again the forward supply and ammunition depots; next the Headquarters and last the big base, in our case on the coast.

2. Next to the destructiveness of the thing, what most amazes me is the number of non-combatants required to transport, to supply, to connect generally[,] to provide and equip the comparatively small fighting line. Every road between the coast and the trenches hums with motor transport, every base is the centre of converging lines of supplies, every trench, every regimental, every brigade, every divisional, every army corps headquarters is connected and linked up with field telephones, motor bicyclists and motor cars. In fact far more men in uniform are seen behind than in the actual fighting line, and what is satisfactory is that the whole machine appears to work admirably. It is a very different problem to tackle from the South African War. Here[,] each battle is a prolonged bombardment of a series of carefully prepared positions; all the appliances of 20thcentury civilisation can be brought to work and the result is good.

It is wonderful to see the variety of uniforms and of faces; and to hear the babel [sic] of tongues at the big centres. In or on the way to the trenches people are either too tired or too frightened to talk, and all movements take place in the dark. One night last week, beautifully starlight [sic], I was riding up the reverse slope of a wooded hill round which were encamped the most extraordinary medley of troops you could imagine, French Cuirassiers with their glistening breastplates and lances, a detachment of the London Scottish, an English howitzer battery, a battalion of Sikhs, a squadron of African Spahis [light cavalry from French colonies in Saharan Africa ] with long robes and tartans, all sitting round their camp fires, chattering, singing, smoking, the very apotheosis of picturesque and theatrical warfare with their variety of uniforms, saddlery[,] equipment, and arms. Very striking it was to see the remnants of an English line battalion marching back from the trenches through these merry warriors, a limping column of bearded, muddy, torn figures slouching with fatigue, with wool[-]caps instead of helmets, sombre[-]looking in their khaki, but able to stand the cold, the strain, the awful losses, the inevitable inability to reply to the shell[-]fire, which is what other nations can’t do. It’s going to be a long long war in spite of the fact that on both sides every single man in it wants it stopped at once. [end of letter]

On 11 November, a grey foggy morning, the QOOH was relieved at daybreak and transferred from the 2nd to the 4th Cavalry Brigade and from the 1st to the 2nd Cavalry Division. It then returned to its billets north-west of Bailleul and spent 12–14 November in billets near the hamlet of La Becque, about seven miles south of Lille between the small towns of Avelin and Attiches, before being sent north-eastwards towards the Belgian front. From 15 to 17 November it was back in its former trenches in front of Wulverghem, where it suffered a few more casualties. The weather was terrible and Fleming’s brother officer who was cited above has left us another grim description:

The weather was perfectly foul, pouring rain and cold. We had to ride about 3½ miles at a walk; we then dismounted and marched another 3 miles to the trenches in an absolute downpour of rain. The men hated marching on foot, not being accustomed to it. The worst part about it was the weight one had to carry; full haversack and water-bottle, rifle and ammunition, waterproof sheet and blanket. Many of the officers also carried a rifle and ammunition, besides field-glasses and a revolver. On top of this everybody wore a heavy greatcoat or British warm, and very often a light Burberry or mackintosh over it. Later in the war British warms were issued to the men, but at this period and for long afterwards, they wore long heavy greatcoats, the lower part of which became caked with mud in the trenches, and the whole soaked through and through with rain, adding greatly to the weight. Although the head of the column generally moved at a foot’s pace, the rear troops usually had to march at four or five miles an hour, and often to double, in order to keep up, owing to the congested state of the roads and the difficulty of keeping close touch in the darkness. The result was that, whatever the weather, hot or cold, dry or wet, one almost invariably arrived at the trenches in what is coarsely, but exactly, described as a “muck sweat”.

Conditions in the trenches were even worse:

The trenches were inches deep in water and the sides a mass of thick, clammy slime, so that everything one touched – rifles, ammunition, food – was immediately covered with it. The trenches were so narrow that it was impossible to get along them; there was only one miserably inadequate communication trench, full of water, which led nowhere; there were no sanitary arrangements and no drainage. The men were not supposed to get out of their trench even at night, and as a matter of fact it was no easy matter to get out, climbing up the steep, slippery side in one’s full equipment. Above ground the muddy surface was equally slippery, and even in well-nailed boots it was impossible to keep one’s feet. So that troops relieving or being relieved slithered and fell in all directions, often into some ditch or shell hole full of water. […] We remained in these trenches seventy-two hours, unable to move a limb by day or by night without being shot at by snipers at close range, and desperately cold, with the temperature some 15 degrees below freezing-point all the time. Many of the men got frost-bitten, and in some cases lost one or more toes, while a few eventually died from gangrene setting in and poisoning the whole system. During all this time we had nothing but cold bully and biscuit to eat and ice-cold water to drink, except for a mouthful of rum.

The QOOH returned to billets at La Becque on 18 November 1914 and from 19 November until 19.00 hours on 22 November it relieved the French in the trenches in front of Kemmel, just to the east of Loker (Locre) in Belgium, where it lost one OR killed in action and three ORs wounded. By this time, Fleming had gained the reputation of being a brave and conscientious officer who took good care of his men, and an incident that occurred on the morning of 20 November shows why. A Trooper in his ‘C’ Squadron was badly wounded in the trenches, whereupon Fleming immediately went to him, had him bandaged up, and carried him to the dressing station with the help of a Sergeant even though it was daylight and they were in full view of the enemy. The weather was freezing cold, and had the man been left in the trench until it was dark, he might well have died of exposure.

At 19.00 hours on 22 November the QOOH was relieved by the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards and proceeded to billets at Noote Boom in northern France, just south-west of Bailleul, where it stayed in Reserve until the end of December 1914, when Fleming’s Regular captaincy was confirmed as a Regular captaincy. Although the Regiment was still in Reserve, it was also a good five miles well away from the front line, and the men spent their time constructing shelters for horses and carrying out whatever training was posted. A colleague later recalled that when in “Reserve”, harsh physical conditions were replaced by monotony, since there was practically no work to be done beyond the daily routine of stables and exercise from about 09.30 to 11.30 hours. So Fleming took up running and persuaded colleagues to do likewise, and he also showed himself to be an imaginative inventor of training schemes so that there was “a very fair variety of recreation, considering the circumstances”. The same officer also recalled that although the terrain was unsuitable for cavalry training, being 90 per cent plough-land with very few jumpable objects except dikes and ditches, a few jumps were constructed over which to train the horses. A couple of officers from other regiments brought back some harriers and beagles from England and started hunting hares, but although this supplied the British officers with some sport, the French Government disapproved of it so much that the British Commander-in-Chief was forced to forbid all forms of hunting and shooting. Polo matches were also organized, with the QOOH being the first regiment to play the game in France, albeit on very rough pastures and generally with only two players per side: nevertheless, the officers got a lot of fun out of it. The men – and some of the officers – played football, and such pastimes helped rather tedious days to pass pleasantly enough: “We were thankful to be left in peace for a time, and did not worry about the future, while we soon grew accustomed to our cramped billets and scarcely noticed the petty discomforts, thinking that any change would inevitably be for the worse.” On 29 November 1914 a replacement draft of three officers and 40 ORs arrived from England.

On 6 December 1914 Fleming wrote another long letter to a friend whom he knew as Randolfo and who, although an officer in another British regiment, it has not been possible to identify. Fleming had expected to meet up with him in Saint-Omer at the end of October and was “immensely disappointed” that the meeting could not take place: “But”, he wrote to his friend, “console yourself with the reflection that it may be bloody in Britain but it’s positively fucking in France.” He then continued with “a faithful account of what we have actually done” which to some extent overlaps with the material cited above: