Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born: 10 March 1885

Died: 11 February 1915

Regiment: North Somerset Yeomanry

Grave/Memorial: Ypres Town Cemetery: E2.18.

Family background

b. 10 March 1885 at Tyntesfield, near the village of Wraxall, North Somerset, as the sixth son and eighth child (of ten children) of Antony Gibbs [II], MA, JP, DL (1841–1907), and Janet Louisa Gibbs (née Merivale) (1850–1909) (m. 1872). From 1872 until 1890, three years after Antony inherited the estate of his mother – Matilda Blanche Gibbs (née Crawley-Boevy) (1817–87) (m. 1839) – the family lived at Charlton House, Portbury, an Elizabethan house with an early Victorian front a few miles west-north-west of Bristol, where Antony managed the model farm that was completed in 1882. It then moved to Tyntesfield, a large house six miles south-west of Bristol and much larger than Charlton House. By the time of the 1891 Census, the house alone employed 17 servants, but by the time of the 1901 Census, that number was down to a housekeeper and five servants, and according to the 1911 Census, when Tyntesfield had become the residence of Antony’s oldest son and his wife, that number had dropped to four. But on all three occasions, other employees would have lived on the estate. The family’s other addresses were Pytte, Clyst St George, Devon, and 16 Hyde Park Gardens, London W2.

Eustace Lyle’s mother was the oldest child of John Lewis Merivale (1815–86) and Mary Anne Merivale (née Webster) (c.1825–57) (m. 1849), an Exeter family who had known the Gibbs family for many years. John Lewis was Clerk in the Chancery Registrar’s Office from 1841 to 1882 and Senior Registrar of the Supreme Court from 1882 to 1885. In his youth he had been the best friend of the novelist Anthony Trollope (1815–82).

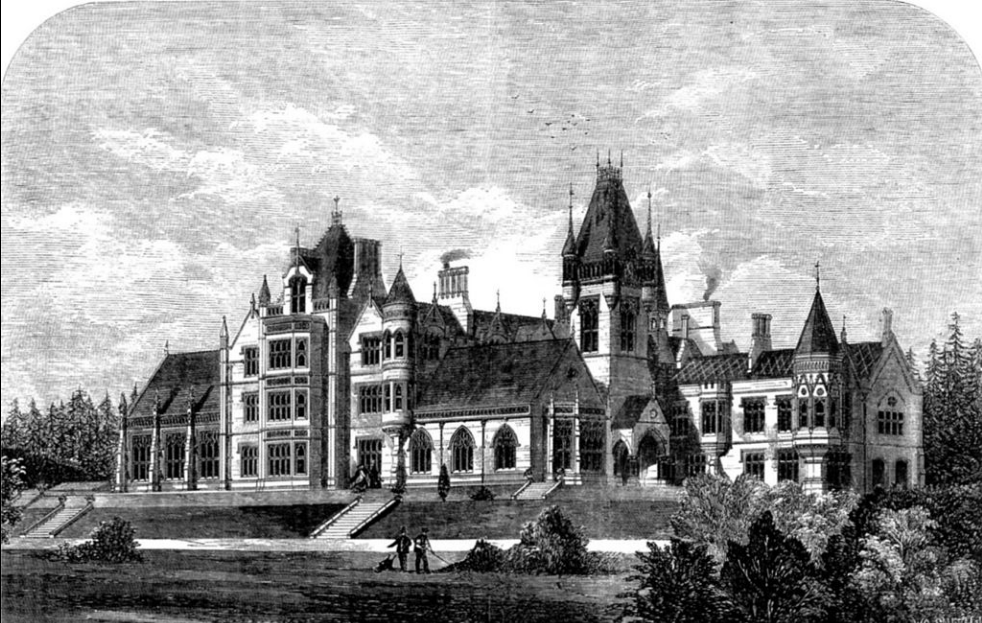

Tyntesfield as depicted in an 1866 edition of The Builder magazine; in 1935 the then Lady Wraxall decided that the central clock tower should be demolished.

Parents and antecedents

According to Aidan Crawley (see below), the Gibbs family came “from yeoman farmer stock round Exeter”, and according to Rachel Gibbs’s detailed genealogical study, its main branch goes back to the Gibbs family of Fenton in Dartington, near Totnes, in 1321, whilst its sibling branch can be traced back to 1560 at Clyst St George, Topsham, Exeter.

Eustace Lyle’s great-grandfather, Antony Gibbs [I] (1756–1815), was educated at Exeter Grammar School and apprenticed in c.1758 to Mr Brook of Exeter, who exported woollen cloth to Spain, Italy and elsewhere. Antony went into the trade, learnt Spanish when he was 17, and in 1778 acquired a wool factory in Exwick, a suburb of Exeter. He then improved his financial prospects considerably by marrying (1784) an heiress, Dorothea Barnetta Hucks (1760–1820), the daughter of William Hucks of Knaresborough (1717–82), who came from a family of Welsh descent that had made a fortune in brewing and acquired estates at Aldenham, in Hertfordshire, and others, including Clifton Hampden, in Oxfordshire. William Hucks was the son of Joseph Hucks (1682–1749), who was possibly the scion of a brewing family and was the younger brother of William Hucks (before 1678–1740), one of the MPs for Wallingford and Abingdon from 1715 to 1734, whose family estates at Aldenham and Clifton Hampden would eventually come to George Henry Gibbs (see below) and his descendants.

When Antony [I]’s factory went bankrupt in 1789, he moved to Madrid, where he founded a firm that successfully traded English woollen cloth for fruit and wine. But in 1797 the firm was driven out of Spain by the Napoleonic War and for four years Antony conducted his business from Lisbon. In 1802 he moved his headquarters to Cadiz but in 1807 he was forced to leave Spain for a second time by the continuing war with France. So in September 1808 the House of Antony Gibbs & Son, merchants and bankers, was opened at 13 Sherborne Lane, Lombard Street, London EC4 (cf. A.H. Huth), and Antony’s two eldest sons – William Gibbs (b. 1790 in Madrid, d. 1875 – Eustace Lyle’s grandfather) and George Henry Gibbs (1785–1842) – became partners in 1813, when the Company was reconstituted as Antony Gibbs & Sons – a name it retained until 1 July 1948. After their father’s death in 1815, William and George Henry became the family firm’s sole partners and its rise was largely due to their efforts.

In September 1814, Charles Crawley [II], BA (1788–1871), who had been educated at Rugby and University College, Oxford, became a clerk with Antony Gibbs & Sons. He was already connected with the Gibbs family, since in 1784 his father, the Reverend Charles Crawley [I] (1756–1849), had married Mary Gibbs (1759–1819), the sister of Antony Gibbs [I], making him a cousin of William and George Henry and a nephew of Antony [I]. On 5 January 1818 he accompanied William Gibbs to Cadiz, Spain, and in the following year he was made a partner of the Gibbs family firm with effect from 1 January 1820. On 1 January 1822, John Moens (b. 1797 in Dublin, d. 1842 in Cruses Darieu, Peru), Antony [I]’s agent, set up the firm’s first South American office in Lima, Peru, where it traded under the name of Gibbs, Crawley and Co. and then under various names including Gibbs and Cia S.A.C. from 1948. In 1822, 1823 and 1826 the firm opened offices in Valparaiso in Western Chile, Arequipa in Western Peru, and Guayaquil, a port city in Western Ecuador, but much hard work and risky speculation yielded little profit until the 1830s. In 1825 Charles Crawley [II] married Eliza Catherine Grimes (c.1795–1881) and in 1828, Charles and Eliza, accompanied by their first child (Charles Edward Crawley; 1827–93), sailed for Valparaiso, where they arrived on 3 January 1829. Although not particularly efficient, Charles oversaw the firm’s affairs in South America until April 1833, when he retired from his directorship and returned to London. In 1829, he had helped to persuade Moens, whom the London firm had come to regard as a liability, to become the Director at $300 per month of a concern called Campania Maquinaria that was based at the mining centre of Cerro de Pasco, high up in the Peruvian Andes. Despite his retirement, Charles’s partnership continued in reality until 1838, when his two younger sons (George Walter and Francis Baden) died in the cholera epidemic, and even then he remained a nominal partner and retained a good salary until the end of 1846, when the firm decided to drop his surname.

In 1838, Charles retired to Littlemore, Oxford, where he became the new high-church squire and where John Henry (later Cardinal) Newman (1801–90), together with a few friends, lived in a modest, quasi-monastic community until 1846. Here, Charles devoted himself to furthering the Tractarian movement, a vocation that included building and restoring churches and founding schools, colleges and hospitals, beginning with places in Clifton Hampden and Aldenham. In 1842 Charles succeeded George Henry Gibbs as Director of the London Assurance Corporation, a position from which he resigned in 1865. In April of the same year, 23 years after their father’s death, and after much hard work and some serious economic set-backs, William and George Henry Gibbs, who were by now earning £20,000 p.a., managed to obtain the monopoly over Peruvian guano, Peru’s major source of income and foreign exchange. As a result they were able to turn the House of Gibbs into one of the most powerful representatives of European capitalism in Peru and the most important firm in one of South America’s largest trades. The monopoly was finally cancelled in 1861, not least because of charges from opposition politicians in Peru of misconduct and the “wilful ruination of Peruvian wealth”. These charges are now thought to have been exaggerated and unsubstantiated, for the Peruvian government took the lion’s share of the profits and spent a large proportion of these on equipping its army. But by this time the Gibbs enterprise was exporting nearly 162,000 tons of guano a year to England alone, where it had become the country’s favourite fertilizer and made William Gibbs one of its richest men: throughout the 1860s he had £1.2 million (= c.£50,000,000 in 2009) of his own capital invested in the firm. When supplies of guano began to diminish, Antony Gibbs & Sons became pioneers in the manufacture of nitrate of soda.

William Gibbs had acquired the Tyntes Place estate at Wraxall, Somerset in 1843/44, but during the early 1850s, Tyntesfield, as it was known by then, had been greatly enlarged by the architect Alexander Roos (1810–81), the son of a German cabinet-maker who had set up a thriving business in Rome. So starting in 1850, William used the family wealth to acquire an impressive collection of old masters and family portraits, and between 1863 and 1865 he also transformed the house at Tyntesfield into a huge Gothic Revival mansion, much of whose former fabric was buried within the higher walls of the new edifice. He also had an engine house installed which provided the whole house with electric light. The architect who was mainly responsible for these changes was John Norton (1823–1904) of Bristol, but an exuberantly conceived chapel was designed by Sir Arthur William Blomfield, ARA (1829–99), and the house and its furnishings benefited from decoration by John Gregory Crace (1809–89).

Matilda Blanche and William Gibbs (centre) and their family at Tyntesfield (c.1862/3); the man with his back to the window on the left of the photo is very probably Antony Gibbs [II], the father of Eustace Lyle

In January 1840, George Henry’s son, Henry Hucks Gibbs (1819–1907), became a member of Lincoln’s Inn, and in 1843 he started working for the London branch of Antony Gibbs and Sons, becoming a partner in 1848. By the time of William Gibbs’s death in 1875, Henry Hucks had acquired a reputation as a skilled financier and so became the firm’s Prior – as the Senior Partner of the House of Gibbs was known – until his death in 1907. He was also the Governor of the Bank of England from 1875 to 1877 and persuaded the Gibbs family firm to diversify into shipping, mining, commodity trading and, increasingly, merchant banking. He served as High Sheriff of Hertfordshire for 1884; from April 1891 to July 1892 he was MP for the City of London; and in 1896 he was made the 1st Baron Aldenham.

In contrast, Henry Hucks’s cousin, Antony Gibbs [II] – William’s second child and oldest son, one of seven children and the father of Eustace Lyle Gibbs – was not so much a businessman as a highly cultivated man with sophisticated aesthetic tastes (cf. Huth). He was educated at Radley College (1855–57) and Exeter College, Oxford (1862–67; MA 1867), and although he studied Law and became a member of the Inner Temple in 1865, he never joined the family firm. He did, however, spend 22 years of his life as an active officer in the North Somerset Yeomanry, a volunteer cavalry regiment that was formed in 1798 and occasionally used in the nineteenth century to help the civil power suppress riots. He joined as a Cornet on 3 January 1871 (just before the Cardwell Reforms abolished that rank and replaced it with the rank of Sub-Lieutenant, now Second Lieutenant), he was promoted Captain in October 1881 and Major in 1886, and he resigned his commission in 1893. But he increasingly directed the major part of his energies into inventing, creating, and collecting objets d’art. He invented an energy-conserving bicycle and besides being an accomplished wood carver and ivory turner, he was a gifted organist. After inheriting Tyntesfield from his mother, Matilda Blanche Gibbs (née Crawley-Boevey), who had continued her husband’s philanthropy and donated large amounts of money to many Anglo-Catholic causes, Antony [II] used his wealth to commission the Anglo-Catholic architect Henry Woodyer (1816–96), a pupil of the Roman Catholic architect Augustus Pugin (1812–52), to modernize and make considerable changes to the house, and to extend the gardens.

Partly because of these “improvements”, Antony [II], his wife, Janet Louisa Gibbs, and their nine surviving children, did not move to Tyntesfield until 1890. Nevertheless, he was the patron of several Anglo-Catholic churches, and served as a JP from 1867 to 1907, as High Sheriff of Somerset in 1888 and as Deputy Lieutenant of that county from 1889 to 1907. He was a member of the Council of Radley College from 1890 to 1897, and, together with his younger brother Henry Martin Gibbs (1850–1928), donated a very large sum to Keble College, Oxford, in memory of their father that enabled it to build the side of its main quadrangle which now includes the hall, library, common rooms, and kitchen. He was active on behalf of the Diocese of Bristol, a Life Governor of the Bristol General Hospital, and “for a great many years” President of the North Somerset Conservative Association. He also enlarged the family’s collection of continental water colours, English oil paintings and old masters. A long obituary described him as the “best and most considerate of landlords” and “a large-minded Conservative and a loyal Churchman and promoter of all good and useful work in the County of Somerset and elsewhere”, who would be remembered “by most men who knew him best for that singular gentleness and humility of character which, in spite of large wealth, induced him to avoid ostentation and shrink from public gaze”.

Family life at Tyntesfield during the 24 pre-war years was good, “halcyon”, even “stable and secure”, with all kinds of games, sports and pastimes available for the young and old, children and guests. There were balls and foreign travel in the winter and summer, holidays in Scotland during the shooting season, church and chapel services on Sundays and festival days, horse-riding at all levels of competence, trips to the coast and nearby Clifton, regular family gatherings, visits to other well-off families in their country seats, and tuition at home for Eustace’s three sisters that involved a Fräulein and a Mademoiselle. It is all presented in fascinating detail by David J. Hogg in chapters one, two and four of his admirable In Memoriam (pp. 6–61, 104–25).

In 1905 Gerald Henry Beresford Gibbs (1879–1939), the 3rd Baron Aldenham and a grandson of Henry Hucks Gibbs, married Lillie Caroline Houldsworth (1877–1950), the elder sister of William Gilbert Houldsworth. As Gerald Henry had no children, the title passed on his death in 1939 to his cousin, Captain Walter Durant Gibbs (1888–1969), who had already, in 1935, inherited the title of Baron Hunsdon of Hunsdon from his father Herbert Cokayne Gibbs (1854–1935), another son of Henry Hucks Gibbs who, in 1919, had married the widow of Algernon Hyde Villiers. Then, in 1915, Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Ralph Crawley-Boevey Gibbs (1891–1957; Magdalen 1910–12; see below), William Gibbs’s grandson, married Dorothy Elizabeth Houldsworth (1894–1951), William Gilbert’s younger sister (and they had two sons and three daughters). During World War Two the 74th Field General Hospital was set up in the grounds of the house and after the war the site was renamed Tyntesfield Estate (Tyntesfield Park from 1946) and many of the existing huts were used to house local families. The 4th Baron Wraxall is currently (2020) the barrister the Hon. Antony Hubert Gibbs (b. 1958). Tyntesfield House was acquired by the National Trust in June 2002: the public donated £7.5 million, c.£17.5 million came from the National Lottery, and a controversial £25 million was provided by the National Heritage Memorial Fund for the renovation of the house and the many other buildings, for renewal of the 550-acre estate, and for ongoing maintenance. The house currently attracts over 110,000 visitors p.a.

Siblings and their families

On 5 June 1915, The Times contained a report on Founder’s Day at Eton College, an annual celebration which takes place on 4 June. But 4 June 1915 was the first Founder’s Day of World War One, and its effects on the foundation were clearly at the forefront of some of those who gave public addresses, for here is an extract from the above report:

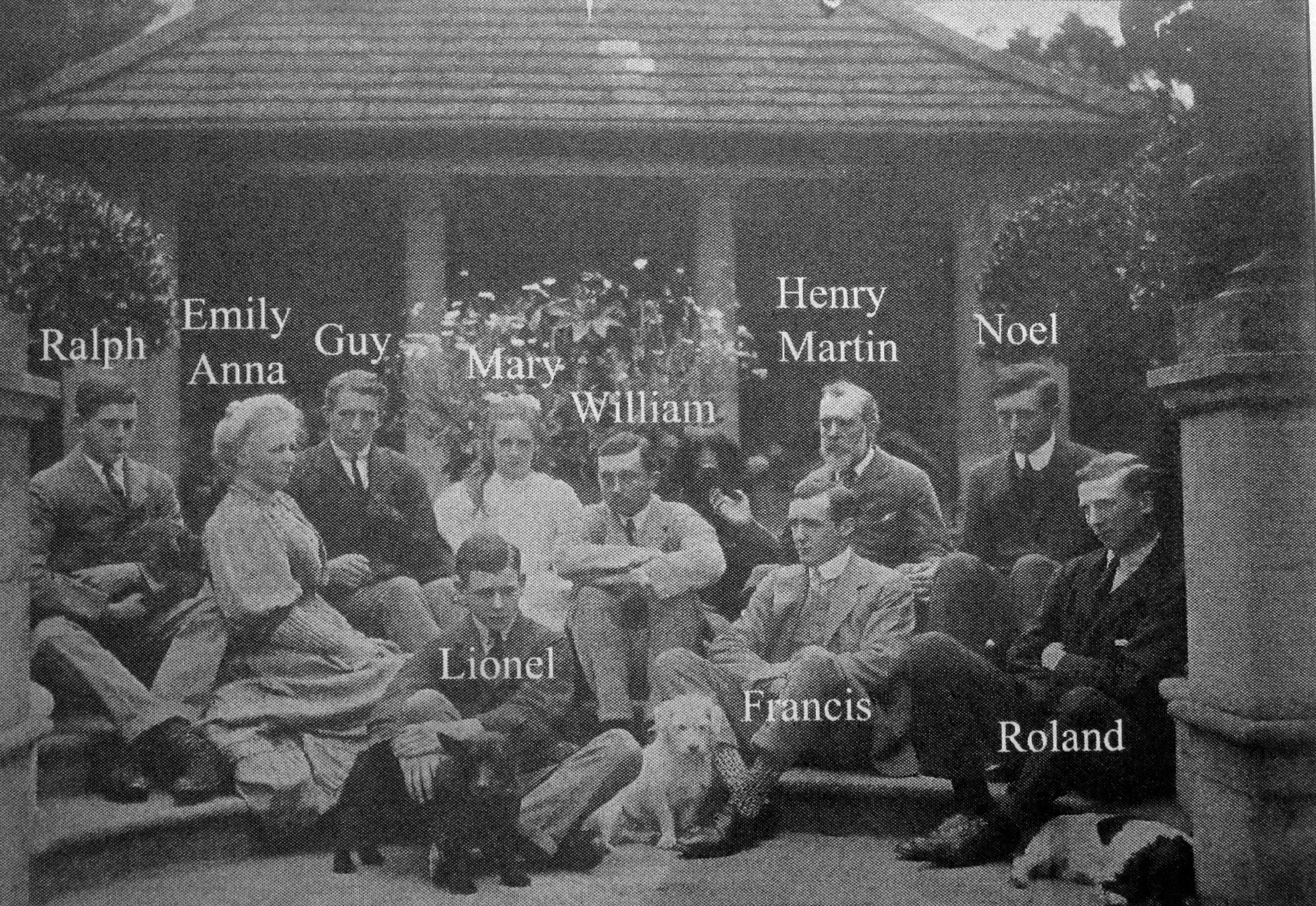

Eton has given, as have all the other public schools, many of her sons to the service of the country. How many there are under arms it is impossible to say, but there is a published record […] of those actually on active service. In the latest edition, which appeared yesterday, there are 2,210 names. Of these[,] 321 have been killed or have died of wounds, 432 have been wounded, and 261 have been mentioned in despatches. The list is widely representative and there are some fine examples, too, of service by individual families. General Gough, V.C., who died of his wounds in February, was one of six Goughs, but the highest record belongs to the family of Gibbs. The names of 11 of its members appear in the list, and nine of the 11 were at one house, Miss Evans’s.

So for the record, here are some details about Eustace Lyle’s siblings and cousins.

Eustace Lyle was the brother of:

(1) George Abraham (later MP, PC) (1873–1931); married first (1901) the Hon. Victoria de Burgh Long (later CBE) (1880–1920); two sons, one daughter; and then (1927) the Hon. Ursula Mary Lawley (later OBE) (1888–1979); two sons;

(2) Antony Hubert (“Huie”; later JP, TD) (1874–1957); married (1899) Mary Mercy Llewellyn (1875–1956); two sons, three daughters;

(3) Albinia Rose (1876–1941); later Bennett after her marriage in 1899 to Richard Alexander Bennett, MA (1872–1953); two sons, three daughters;

(4) William (1877–1963); married (1911) Ruby Mabel(le) Brassey (1887–1981); two daughters;

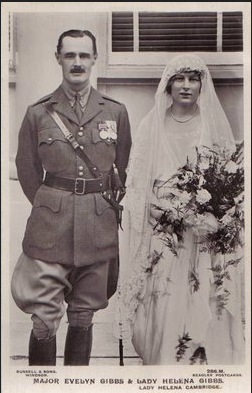

(5) John Evelyn (later MC) (1879–1932); married (1919, in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle) Lady Helena Frances Augusta Cambridge;

(6) Anstice Katherine (“Nancy”) (1881–1963); later Crawley after her marriage in 1903 to Revd Arthur Stafford Crawley (1876–1948); three sons, two daughters;

(7) Louis Merivale (1883–84);

(8) Janet Blanche (1887–1974); later still Gibbs after her marriage in 1915 to Major William Otter Gibbs (1883–1960) (later JP, DL); one child;

(9) Lancelot Merivale (“Lags”; later Brigadier, CVO, DSO, MC and Bar) (1889–1966); married first (1929) the Hon. Marjory Florence Maxwell (1906–39); one son; then (1942) Diana Primrose Quilter (1916–2011), marriage dissolved in 1945, after which she married (1947) Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Tennant (1907–55); two daughters.

The nine surviving Gibbs children (1894); Eustace Lyle is the second seated small boy from the right

(Courtesy of David J. Hogg Esq.; ©The National Trust, Tyntesfield)

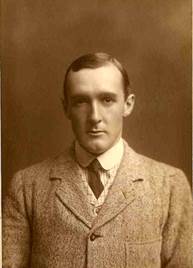

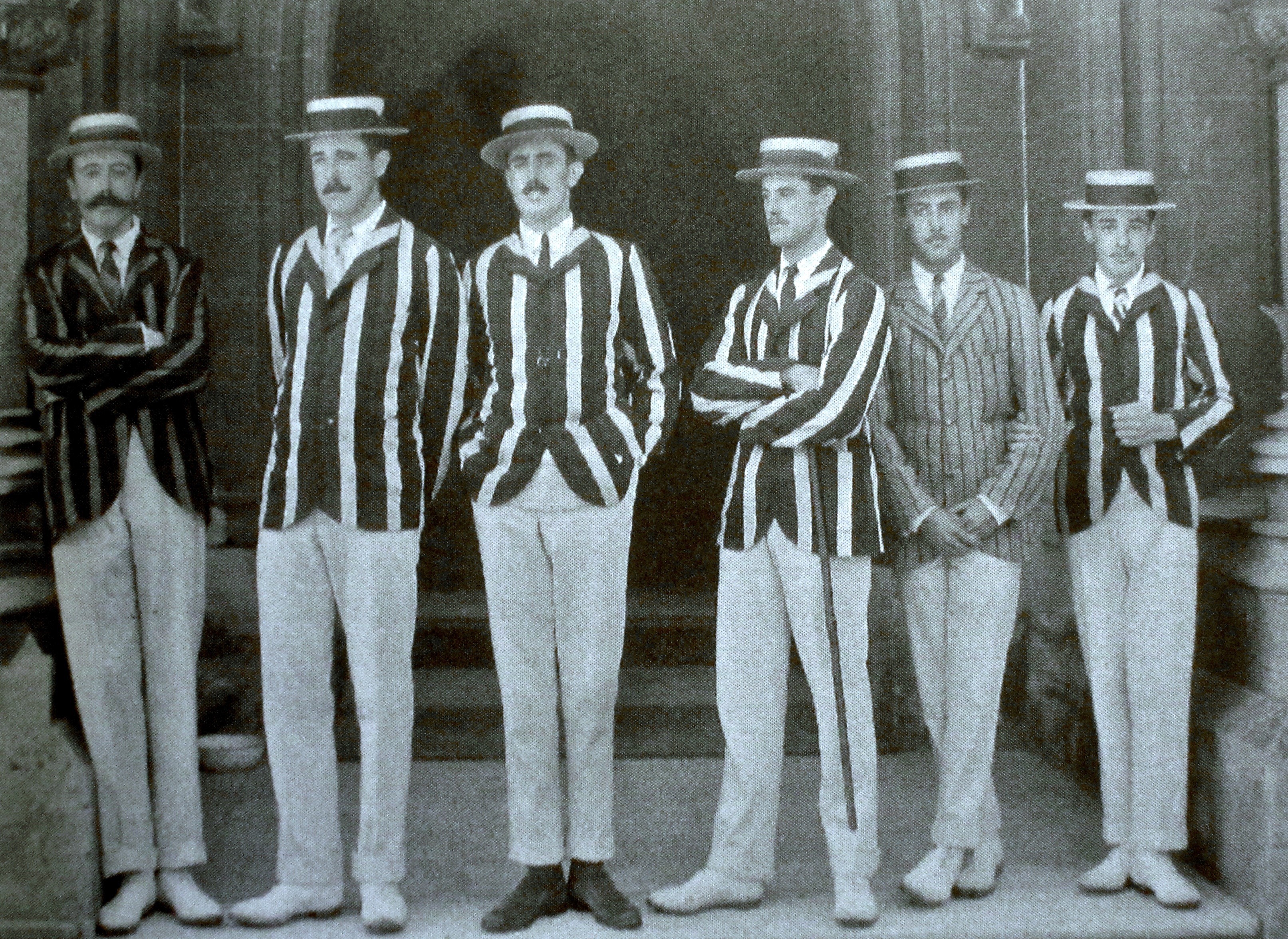

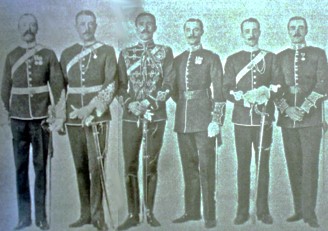

The Gibbs boys in descending order of age from left to right (c. 1910): George Abraham, Antony Hubert, William, John Evelyn, Eustace Lyle and Lancelot Merivale

(Courtesy of David Hogg Esq., In Memoriam, p. 15; ©The National Trust, Tyntesfield)

George Abraham Gibbs

George Abraham’s first names go back to Doctor George Abraham Gibbs (1718–94), the father of Antony [I], but these names are also to be found in the name of his uncle George Abraham Gibbs (b. 1848, d. 1870 in Jamaica) and George Abraham Crawley (1864–1926), the well-known artist, designer and purveyor of English taste in the USA and the eldest son of the successful railway contractor George Baden Crawley (1833–79) (q.v.), whose father, just to complicate matters, was also called George Abraham Crawley (1795–1862). From c.1880 to 1887 George Abraham Gibbs was educated at Pembroke Lodge Preparatory School, Southbourne, Bournemouth, Hampshire (founded in 1880), before studying at Eton (1887–92) – where he, like all Antony [II]’s sons, including Eustace Lyle, plus at least three other younger members of the Gibbs family, were members of the Cadet Corps. George Abraham then studied at Christ Church, Oxford (1892–97), where he was Master of the Beagles and “developed an enthusiasm for things military”. A keen traveller, after taking his degree he spent some time travelling in Europe, Africa and India, finding many opportunities for hunting and shooting.

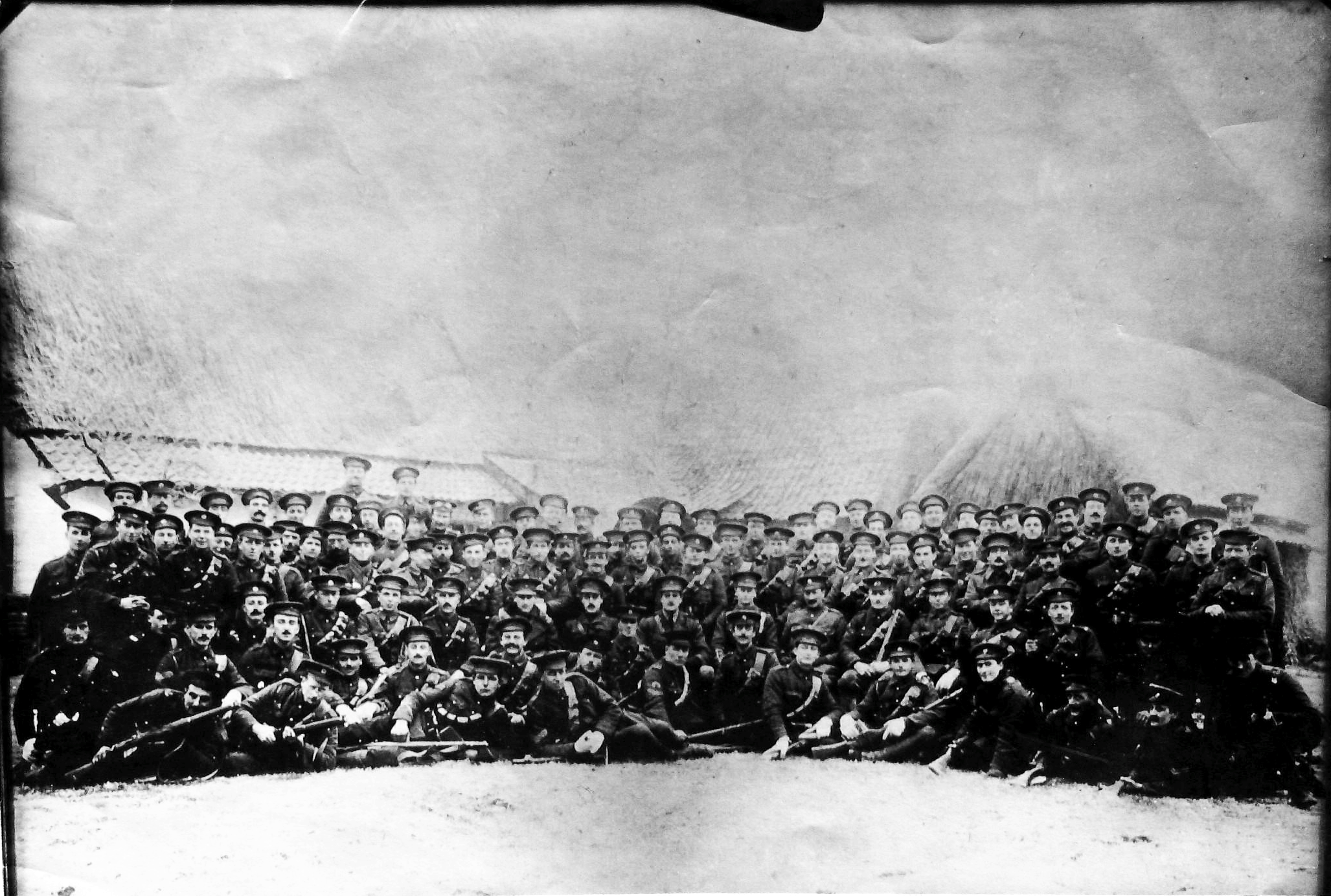

On 28 January 1893 he joined the North Somerset Yeomanry as a Second Lieutenant and was promoted Captain in September 1895. During the Second Boer War George Abraham served with the 48th Company of the 7th Battalion of the Imperial Yeomanry, a volunteer unit of fast-moving mounted infantry that had been raised in 1899 and was sent to South Africa in January 1900 to redress a series of defeats by the more mobile Boers during the opening months of the war. Here, he took part in operations in the Transvaal (May and June 1900, including the entry into Pretoria on 5 June and actions near Johannesburg and Diamond Hill on 11 and 12 June) and was awarded five clasps He was promoted Major in c.1902 and Lieutenant-Colonel – and therefore the Commanding Officer of the Regiment – in 1908. After being injured in a riding accident in South Africa on 30 June 1900, he was invalided home in July, where he became acquainted with the Hon. Victoria Florence de Burgh Long (1880–1920) – probably through local political circles – and they married on 26 November 1901. On 30 December 1901 they set off on a honeymoon which took them through Europe, Egypt and India, and lasted until April 1904, when they returned to Tyntesfield.

At the General Election of February 1906, which the Liberal Party won by 130 seats, George Abraham was elected Conservative MP for Bristol West (1906–28) by a majority of 365 votes. His popularity grew in his constituency, and in 1924 he kept his seat with a majority of 17,300 votes. In 1911 George Abraham and his wife moved from Tyntesfield, now almost empty, to 22 Belgrave Square, London SW1, one of the largest and most fashionable squares in London; in 1911 and 1912 the couple went on a tour of Canada, and in spring 1914 they visited Madrid. Although George Abraham did not see active service during World War One, in 1914 he raised the 2/1st Regiment of the North Somerset Yeomanry (NSY) for the purpose of supplying drafts to the 1/1st Regiment, which was in France, and commanded it until 1917, when his time in the military came to an end. But from October 1916 to 1917 he had been the Acting Brigadier who commanded the NSY Brigade that was equipped with bicycles and based at Ipswich; and from 1917 to 1928 he was a member of the Territorial Army Reserve. During World War One his first wife, Victoria, directed the Bristol Soldiers and Sailors Help Society and was awarded the CBE for her work in 1918, but she died of septic pneumonia and pleurisy on 29 March 1920 as a result of the post-war ‘flu’ pandemic. In 1927 George Abraham married for the second time – the Honourable Ursula Mary Lawley (1888–1979), the elder daughter of Arthur Lawley, the 6th Baron Wenlock (1860–1932), and sometime Maid of Honour to the Queen. She had worked for the nursing services in France during World War One and become prominent in the Somerset branch of the British Red Cross Society – work for which she was awarded the OBE in 1945.

An enthusiastic freemason, George Abraham was Provincial Grand Master for the Province of Bristol from 1908 and President of the Somerset Society from 1912 to 1922. As Conservative and Unionist MP for Bristol West until 1928, he was not a frequent speaker but was active behind the scenes and rapidly gained the confidence of his party. During Lloyd George’s wartime coalition government (1916–22), he was Parliamentary Private Secretary (1916–19) to his father-in-law, Walter Hume Long (1854–1924; 1st Viscount Long of Wraxall in 1921), who sat as a Conservative MP in every Parliament from 1880 to 1924 – albeit for several different constituencies, including North Wiltshire from 1880 to 1885 and Bristol South from 1910 to 1918. Long was Secretary of State for the Colonies from December 1916 to January 1919 and the First Lord of the Admiralty from January 1919 to February 1921. George Abraham was also a Government Whip (1917–21) and Treasurer to the Royal Household (1921–24 and 1924–28), and in 1923 he was made a Privy Councillor. On his retirement from politics in 1928 he became the 1st Baron Wraxall of Clyst St George. His obituarist in The Times described him as “an admirable example of that class of public-spirited country gentleman who have for generations served this country in their homes and in Parliament”. He left £366,973 7s. 1d. (= c.£16,802,020 in 2017).

During World War One, Victoria’s brother, Brigadier Walter (“Toby”) Long, CMG, DSO (1870–1917), the General Officer Commanding (GOC) 56th Brigade in the 19th (Western) Division and a “promising young General”, was killed in action by a stray shell, aged 37, while inspecting front-line trenches near Hébuterne, five miles north-west of Beaumont-Hamel. He is buried in Couin British Cemetery, Grave VI.C.19, with the inscription “Duty”.

Antony Hubert Gibbs

Antony Hubert was also educated at Pembroke Lodge Preparatory School from c.1884 to 1887. He then studied at Eton (1888–92) and Trinity Hall, Cambridge (1893–97). He worked for a while as a banker in the City, but after his marriage in 1899 he and his wife made their home in Clyst St George, East Devon, four miles south of Exeter. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the North Somerset Yeomanry in 1895, promoted Lieutenant in December 1898, Captain in 1904 and Major in June 1912. He served in the 1/1st NYS from 4 August 1914 to March 1917 and landed in France with his Regiment on 2 November 1914 as part of the 6th Cavalry Brigade in the 3rd Cavalry Division. Antony Hubert stayed in France with his Regiment until May 1915, but from then until March 1917 he commanded the 1/3rd NYS at Bath, and from May 1917 until the Armistice he was on the Staff of the Quarter-Master General Southern Command at Salisbury.

After the war he was a Director of the City Bank and the Exeter Bank in Devon and a Local Director of the National Provincial Bank. He left £44,919 2s. 6d. (= c.£1,072,017 in 2017).

Antony Hubert’s wife was the daughter of Colonel Evan Henry Llewellyn (1847–1914) and Mary Blanche Llewellyn (née Somers) (c.1847–1914) (m. 1868). Both before and after the war she was active on many committees concerned with welfare. Her father was a retired army officer who sat as the Conservative MP for North Somerset from 1885 to 1892 and 1895 to 1906. He was, coincidentally, the great-great-grandfather of David Cameron (b. 1966), the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016.

Antony Hubert’s elder son, Evan Llewellyn Gibbs (1906–40), became a Captain and Company Commander in the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards and was killed in action at Dunkirk in June 1940. He has no known grave.

Albinia Rose Gibbs

In 1899 Albinia Rose married Richard Alexander Bennett, MA (later JP), the elder son of the Reverend Alexander Sykes Bennett (1847–1912) and Jessica Bennett (née Payne) (1844–88) (m. 1868). His father had studied at Exeter College, Oxford, and from 1861 to 1863 was the Curate of Wilton, Wiltshire, two miles west-north-west of Salisbury. From 1863 to 1880 he was the Vicar of St Peter’s, Bournemouth, one of the best- endowed Gothic Revival churches in England, which was constructed between 1855 and 1879 as the mother church of Bournemouth under the aegis of Richard Alexander’s paternal grandfather, the Reverend Alexander Morden Bennett (1808–80). From 1845 until his death, Alexander Morden was the first Vicar of St Stephen’s, Bournemouth, a new Gothic Revival church designed by John Loughborough Pearson (1817–97), and he was followed in this living by Alexander Sykes Bennett from 1881 to 1911. Richard Alexander studied at Eton, where he overlapped with the three older Gibbs boys, through whom he got to know his future wife. He then studied at Christ Church, Oxford, where he overlapped with Antony Hubert. After their marriage, he and Albinia Rose made their home in Thornbury Park, to the north of Bristol. From 1896 to 1899 he played cricket for Hampshire as a right-handed batsman and a wicket-keeper; he captained a team that toured the West Indies in 1901–02; and he also played for the MCC. In 1911 he became Director of a brewery and during World War One he was an officer in the 2/1st Gloucestershire Yeomanry (Territorial Force), a unit that served in England for most of the war until, in April 1918, it was sent to Dublin for the remainder. Richard Alexander was demobilized as a Captain in March 1919.

William Gibbs

William followed his two elder brothers at Pembroke Lodge Preparatory School from 1887 to 1891, attended Eton from 1891 to 1896 and Magdalen College, Oxford, from 1896 to 1899, when he was awarded a third in Jurisprudence. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars on 17 February 1900 and promoted Lieutenant on 29 November 1900. From 1901 to 1902 he served with his Regiment in the Second Boer War and was awarded the Queen’s Medal with five clasps for his part in the operations in Cape Colony (December 1901–January 1902), in the Orange River Colony (January to March and May 1902), and in the Transvaal (March to May 1903). In 1907 he was promoted Captain and from March 1913 to October 1916 he was the Brigade Major of the Eastern Mounted Brigade. From October to December 1915 he served in Gallipoli with ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) units from October to December 1915 and then became a Staff Officer in the Western Defence Force in Egypt until October 1916. From October to December 1917 he was in France as a Major with the 12th (Service) Battalion, the Yorkshire Regiment, and from April 1918 to April 1919 he served with the 7th Hussars once more, this time in Mesopotamia, where, in September 1918, he became their Commanding Officer with the rank of Acting Lieutenant-Colonel. On 28 October 1918 he was wounded at Shergat, near Mosul. He was mentioned in dispatches twice (London Gazette, no. 29,845, 1 December 1916, p. 11,803; no. 31,386, 3 June 1919, p. 7,236) and awarded the French Croix de Guerre avec palme. In 1919 he was confirmed in the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel; in 1920 he became a member of the Regular Army Reserve of Officers; and from 1926 onwards he became an officer – an Exon – in the King’s Bodyguard of the Yeomen of the Guard. He left £42,053 16s. 7d. (= c.£740,904 in 2017).

His wife was the daughter of Henry Arthur Brassey, DL, JP (1840–91), of Preston Hall, Kent, one of the two Liberal MPs for Sandwich, Kent (1868–85), and High Sheriff of Kent (1890).

John Evelyn Gibbs

John Evelyn, like his three older brothers, attended Pembroke Lodge Preparatory School, from c.1886 to 1892, before transferring to Eton (1892–97). But he then entered the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) (1898–99), was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards on 20 January 1900, and promoted Lieutenant on 1 November 1901. During the Second Boer War, he served in operations in Cape Colony (July 1901 to 31 May 1902), and was awarded the Queen’s Medal with three clasps. On 15 August 1901 he wrote a letter to his sister Anstice (“Nancy”) in which he rejected the idea that the war in South Africa was “fun” and described just how difficult it was for British troops to deal with “the wily Boer”, even when their columns outnumbered the Boers’ small mobile groups of 60–100 horsemen. On 17 October 1901 – in another letter to Nancy – he was even more negative about the situation in South Africa, describing conditions there as “frightfully hot and dusty […], in fact horrible”. On 6 April 1902 he repeated his tacit assessment of the military situation in South Africa in a third letter to Nancy by ending an account of the way in which a group of 13 Boers had managed to cross the British line without being detected with the weary conclusion: “and so it goes on”. When the Second Boer War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging on 31 May 1902, the boredom of military life continued, for on 14 August 1902 Evelyn wrote in a fourth letter to Nancy: “Rather afraid we shan’t be able to play today at polo as it has been raining which will be a terrible thing as one has only got polo to look forward to all the week. (We did though and it was awful!!)” Finally, on c.15 September, Evelyn was finally able to leave South Africa – the last member of his family to do so – and he arrived back in England on about 7 October 1902.

But despite the trials of the two preceding years, he decided to remain in the Army and served as the Adjutant of the 3rd Battalion, the Coldstream Guards, from about April 1904 to around April 1907. From September 1907 to June 1910 he was in India as aide-de-camp to Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynmound (1845–1914), the 4th Earl of Minto and Viceroy of India from 1905 to 1910. John Evelyn was promoted Captain in January 1910, and when King George V was crowned on 22 June 1911 he served as acting aide-de-camp to Field-Marshal Lord Kitchener (1850–1916; 1st Viscount Kitchener from 1902). In August 1914, almost immediately after the outbreak of World War One, John Evelyn went to France with the 1st Battalion, the Coldstream Guards, which was heavily involved in the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–30 November 1914), the Germans’ first major attempt to take Ypres. When, on 26 October, his brother Lancelot (see below) spent ten minutes with John Evelyn on the road to Gheluvelt, in southern Belgium, not far from Ypres, he learnt that although John Evelyn himself was “very well”, his Battalion “had suffered terribly […]. Only 10 officers left at all and only 80 men in [his] Company”. Three days later, on 29 October 1914, when John Evelyn was in command of a composite Company of men from the Coldstream Guards and the Black Watch that was involved in the heavy fighting on the road into Gheluvelt, two battalions of Bavarian infantry broke into the British trenches. Although John Evelyn’s composite men, who were a little to the north, succeeded in beating back three heavy attacks by 06.00 hours, they were finally overwhelmed by the weight of numbers.

At first it was feared that he, like so many of his fellow officers, had been killed in action, but Lancelot, whose 2nd Battalion, the Coldstream Guards, was positioned nearby, made strenuous efforts to find out what had happened to Evelyn and reported his findings in two letters to Nancy of 29 and 30 October. He discovered that the Germans had begun their attack at 05.30 hours and that by 07.40 hours, after the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, had been forced to withdraw, they had managed to get behind John Evelyn’s neighbouring Battalion and surround the survivors, who fought “back to back, [John] Evelyn in the middle”, and in confirmation of this, a Corporal from John Evelyn’s Company told Lancelot that he had last seen Evelyn “standing with about 11 men round him trying to fight their way out”. So at first John Evelyn was posted “missing”, but it later transpired that he was one of the two officers of his Battalion who had managed to survive the fierce hand-to-hand fighting of 29 October and that he had been wounded and captured, together with between 100 and 150 other ranks from his Battalion. So he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war (PoW) in Germany.

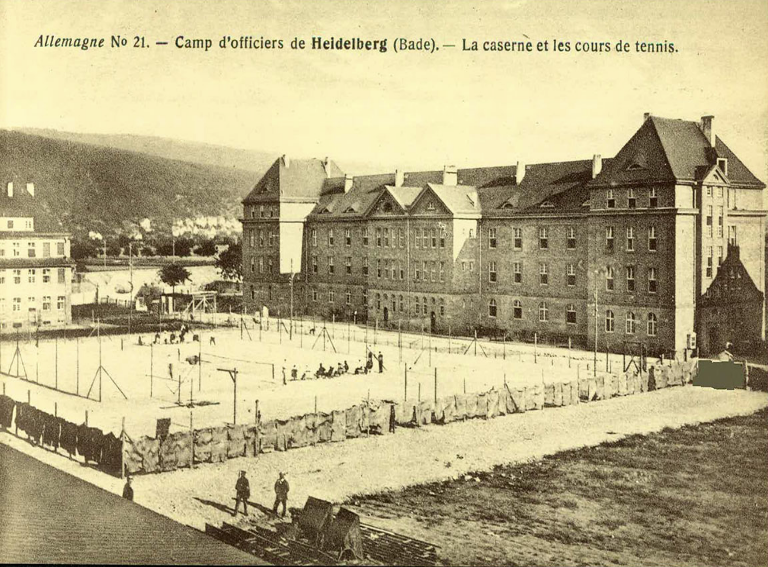

PoW Camp for Allied Officers just outside Heidelberg, Germany, showing the main barrack block and the tennis courts.

John Evelyn’s first PoW camp was situated a few miles outside Heidelberg, and conditions were good there. But by mid-July 1917 he had been moved to a camp at Schwermstadt, a small town in Lower Saxony 32 miles north of Hanover. In a letter to Nancy of 26 July 1917, Lancelot reported, courtesy of a recent escapee, that even though Schwermstadt was not “such a good place as Crefeld”, John Evelyn was “very well and seems happy with several friends” and that he was taking “a good deal of exercise and is allowed out 4 times a week on ‘parole’”. But, he added: there were no tennis or fives courts; washing arrangements were primitive; the PoWs had to wait in long queues for their pay, mail, food etc.; and were reliant for good food on English parcels as the German food consisted only of “soup twice a day and also that coffee about 3 or 4 times a day”. Clearly, the naval blockade of food supplies to Germany and Austria-Hungary which the British had imposed at the outbreak of war was beginning to cause serious shortages. Luckily, Lancelot concluded: “there are no Russian or French prisoners to feed from the English parcels” so that “food should now go much further”; “the Germans do not take things out of the parcels”; and “the German orderlies are good and kind”. By mid-November 1917, John Evelyn had been transferred yet again and told Nancy in a letter of 15 November that he and others had been “moved from Holzminden [40 miles south-south-west of Hanover] at short notice” to a camp in Freiburg im Breisgau, in south-western Germany. John Evelyn was very happy about the transfer since conditions at Holzminden had clearly deteriorated over time, whereas “here it is peaceful and the minimum of worry. There it was all the reverse”. Freiburg’s old university served as the camp; the cooking facilities were vastly better; and whereas the younger internees could play football “on a very good grass field outside the town”, the older ones were allowed out on two long walks and two short ones in the country during the week. John Evelyn stayed there until April 1918, when he was transferred to The Hague, in Holland, where, after the Armistice, he helped in the repatriation of other PoWs. He was finally released on 12 January 1919 and awarded the MC in the following year (London Gazette, no. 31,759, 27 January 1920, p. 1,219).

After the war was over, John Evelyn was promoted Major (with effect from 17 July 1915) (LG, no. 31,216, 4 March 1919, p. 3,127), Lieutenant-Colonel (with effect from 1 October 1920) (LG, no. 32,093, 19 October 1920, p. 10,174) and finally Colonel (with effect from 22 September 1926, with seniority from 1 October 1924) (LG, no. 33,208, 5 October 1926, p. 6,371). From 1920 to 1921 he commanded the 1st Battalion of his old Regiment, and from 1928 to 1930 he commanded the 129th (South Wessex) Infantry Brigade (Territorial Army). From August 1930 he was the Commanding Officer of the Coldstreams and their Regimental District. His wife, whom he had met in 1914 at Waterloo Station when he was en route to the front, was the third child of Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Adolphus Charles Cambridge (1868–1927), Queen Mary’s younger brother, who became the 1st Marquess of Cambridge in 1917 on renouncing his Germanic title of His Highness, the 2nd Duke of Teck. So Lady Helena renounced her title of the Princess of Teck at the same time and became Lady Helena Cambridge. Their marriage, with John Evelyn’s brother Lancelot as best man, took place on 2 September 1919 in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, where Lord Adolphus was the Governor and Constable from 1914 to 1927, before a very distinguished congregation. John Evelyn died at Estcourt Grange, Gloucestershire, and is buried in St John the Baptist’s Graveyard, Shipton Moyne, Gloucestershire. He left £13,743 15s. 2d. (= c.£629,243 in 2017).

Anstice Katherine (“Nancy”) Gibbs

Nancy worked as a nurse in the Nunthorpe Hospital, York, during World War One, from 1916 to 1918. When she died in 1963 she left £8,456 13s. 7d. (=£148,985 in 2017).

Her husband, the Reverend Arthur Stafford (“Staff”) Crawley, was the youngest son and sixth child of the successful and very wealthy railway contractor George Baden Crawley (1833–79) and distantly related to Lord Baden Powell and G.F.W. Powell. In his eminently readable autobiography, Nancy and Arthur’s second son, Aidan Merivale Crawley, MBE (1908–93), would later describe his family as “unostentatious gentlefolks who lived worthily – did faithful and useful service in whatever profession or calling they happened to be engaged”, adding that they also “developed certain proclivities. They were strong churchmen, they married members of the Gibbs family every three or four generations, they went to Harrow School, and over the last hundred and fifty years have been good games players”. Aidan’s father fitted into this pattern precisely. He studied at Harrow before matriculating at Magdalen (1895–8; BA 1898; MA 1908); he obtained two Blues in 1898 (cricket and athletics); he was a keen horseman and rode to hounds (cf. H.B. Cardwell); and while at Magdalen he came under the influence of Cosmo Gordon Lang (1864–1945), Magdalen’s Dean of Divinity from 1893 to 1896 and the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1928 to 1945, who encouraged Arthur Stafford to think of ordination (cf. A.A. Steward) and performed the betrothal when he married Nancy Gibbs at Tyntesfield on 16 June 1903.

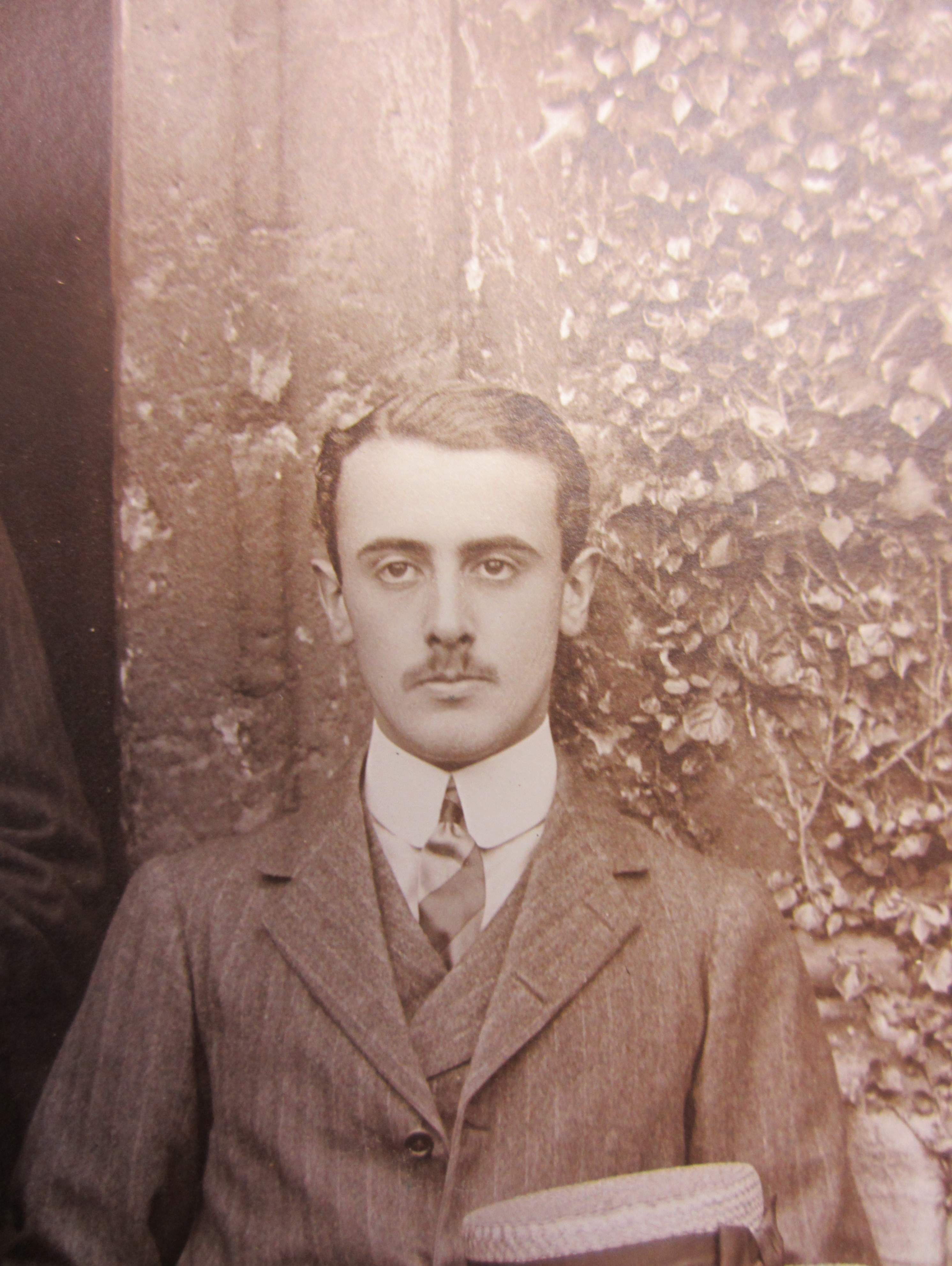

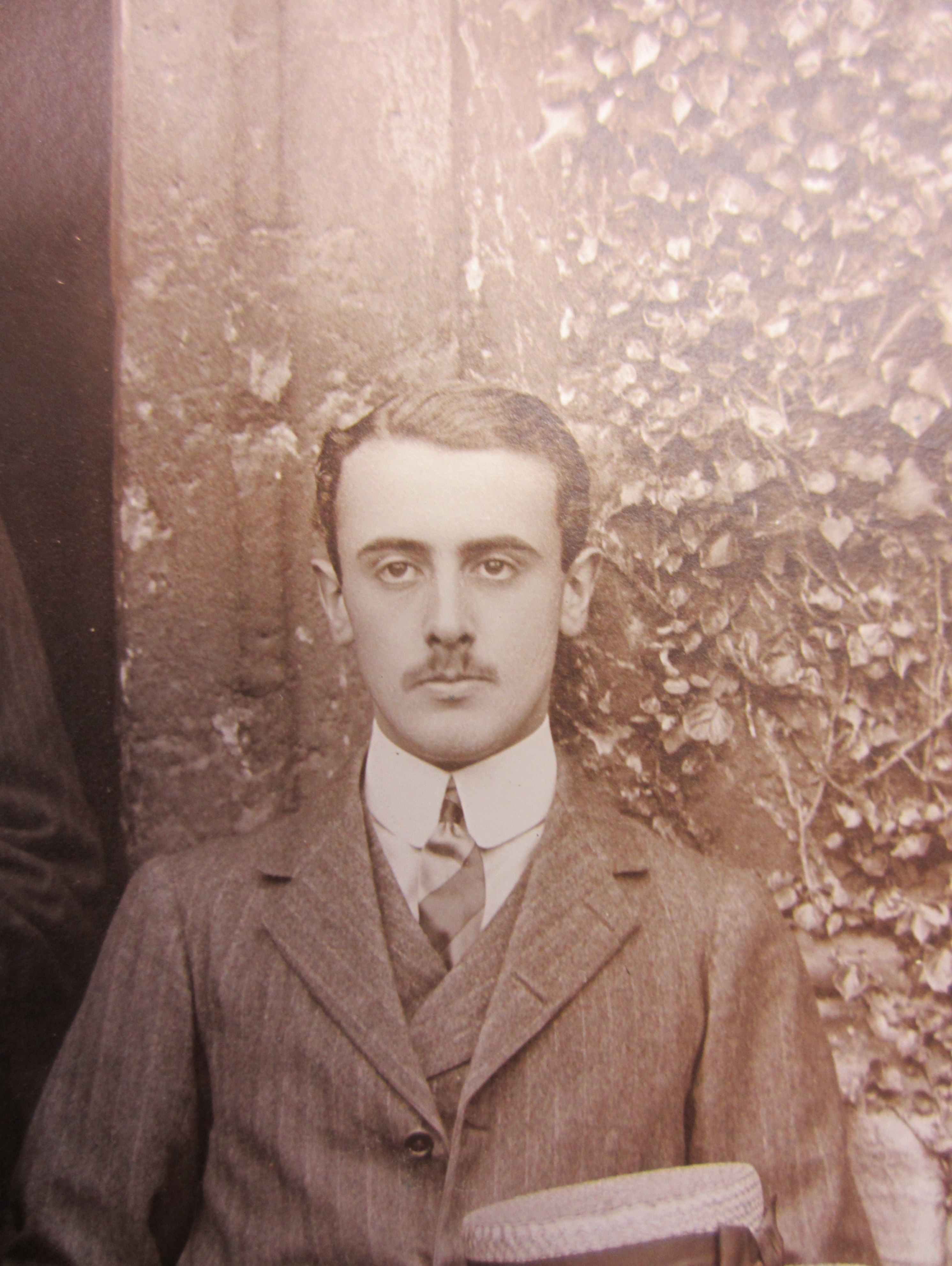

Arthur Stafford Crawley (1897); detail from the photo of the Waynflete Society, 1897

(Courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

After a tour of India (1899–1900), Arthur Stafford studied at Cuddesdon Theological College, Oxfordshire, in 1900 and was ordained Deacon in 1901 and Priest in 1902. From 1901 to 1903 he was Bishop’s Chaplain and, simultaneously, the Curate of St Dunstan’s Church, Stepney, i.e. in the diocese where Cosmo Gordon Lang was Suffragan Bishop from 1901 to 1908, and he then served as Curate of St Luke’s Church, Chelsea, from 1903 to 1905. From 1905 to 1910 Arthur Stafford was Vicar of Benenden, Kent, and from 1910 to 1918 he was Chaplain to Lang, who was Archbishop of York from 1908 to 1928. Arthur Stafford also held the livings of Bishopsthorpe (1910–18), the village where the Archbishop’s palace was located, and Acaster Malbis (1914–18), three and five miles south of York respectively.

Right from the start of the war, Arthur Stafford was eager to minister to troops at the front, but being a family man with responsibilities, it took him a certain amount of time to arrange things. But on 10 September 1914, having left his family living for the duration in the Elizabethan wing of the Bishopsthorpe palace, he disembarked in France as an Army Chaplain (4th Class; promoted to a Chaplain 3rd Class on 10 September 1918 “without increase in pay or allowances [while acting as Senior Chaplain]”). By early February 1915 he was attached to the very large No. 14 General Hospital at Wimereux, a coastal town just north of Boulogne, and he was still there on 10 March 1915. But when the Guards Division was formally established on 20 August 1915, he was made one of its Chaplains, an appointment that was almost certainly connected with the fact that the new Division was commanded by his brother-in-law, Frederick Rudolph Lambart, Major-General (later Field-Marshal) the 10th Earl Cavan (1865–1946), who had married Arthur Stafford’s sister, Caroline Inez Crawley (1870–1920) in 1893. Cavan knew Arthur Stafford well and had a high opinion of him which grew as the war went on. On 2 October 1915 Cavan mentioned in a letter to his wife that he had heard from a third party that Arthur Stafford had done “splendidly all through the last fighting in Vermelles” (i.e. during the First Battle of Loos: 25 September–8 October 1915); and in a brief but reassuring letter to Nancy that he wrote on the same day he said: “Just one scribble to tell you Stafford did splendid work with the wounded all though our last fight. God keep him. I knew he would do well.” So on 12 October, the eve of the Second Battle of Loos, Cavan had Stafford to dine, noting in a letter to Caroline Inez that he was “thankful for a good meal and a few quiet hours”. And on 15 December 1915 he remarked in another letter to Nancy that Stafford Crawley, about whom he was clearly concerned, did not look well and gets “so deadly white”.

Lancelot Gibbs frequently mentions Arthur Stafford in his Diary and it is clear from his remarks that he took his pastoral work very seriously. He held impromptu and more informal services when and where he could, even on 16 July 1916 (i.e. during the Battle of the Somme: 1 July–18 November 1916) in a small dug-out; he also organized regular services and burials, and conducted the occasional church parade – though we hear relatively little about these. If there was work to be done, he seems to have been fairly indifferent to the weather, and when, on 24 September 1915, Lancelot showed him round his large and battered “Parish” for the first time, he was seen to be wearing “a most indifferent waterproof that got wet through before starting, but didn’t seem to mind”, and in the run-up to the Battle of the Somme he seems to have preferred living in a dug-out to living in comfort with the other officers. Aidan Crawley painted a very moving picture of his father’s work in the Army which dovetails with the above observations. Apart from conducting services,

his real job was to get to know the men and officers and help them in every possible way. Because he was a parson […] they would often talk to him in ways they would not dream of talking to each other. Young officers who lacked the confidence to lead, officers and men who were scared stiff and nearing breakdown, men who hated each other, men who simply wanted to get out of it all and go home, would pour out their feelings to him, knowing that not a word would ever be repeated. […] In many ways it was like ministering to a parish, but a parish so closely knit that everyone knew everyone else’s business. It was rewarding because, at some time or another, almost every man wanted to see and talk to him.

On one occasion, not long before the Battle of the Somme, Arthur Stafford had had to minister to a 24-year-old guardsman who had been sentenced to death for desertion on the basis of very flimsy evidence and whom the Divisional authorities refused to reprieve. Although there are discrepancies in the documentary material, the condemned man was almost certainly Guardsman William Thomas Henry Phillips (possibly 1892–1916), the son of William Phillips (1849–1931), a Cumberland iron ore miner, and Mary Phillips (née Beck) (1860–1934) (m. 1880: two boys, four girls), who was shot on 30 May 1916. At the time of the 1911 Census William Thomas Henry was also an iron ore miner who lived with his parents at 22 Scalegill, Moor Row, Egremont, Cumberland. He had arrived in France on 21 August 1914 with the 1st Battalion, the Coldstream Guards, and by the time of his trial in 1916, he was under a suspended sentence of ten years’ penal servitude for a previous case of desertion. So, Aidan continued:

When it came to writing to the boy’s parents, Father simply lied, saying that their son had been killed in action [on 12 June 1916 – the date that also appears on his medal card]. It was, he said, his worst experience in the whole war, and it haunted him for the rest of his life.

Despite the lie, his family did not receive a war gratuity (“not admissible”), and when, on 17 July 1919, William’s younger brother Joseph (b. 1896) applied for medals on his behalf, the application was refused because of his desertion.

In autumn 1916 Arthur Stafford was awarded the MC for his work as an Army Chaplain, especially with the wounded, and in the following year he was awarded a Bar to his MC for a similar reason – rescuing wounded soldiers between the trenches while under fire (London Gazette, no. 13,012, 16 November 1916, p. 2,074; no. 30,308, 25 September 1917, p. 9,970). News of the MC reached Lancelot Gibbs on 3 October 1917 and the citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during an attack on a hostile position. He displayed the greatest fearlessness and devotion to duty throughout the day, never hesitating to expose himself that he might render assistance to the wounded, and making his way twice through an intense bombardment in order to fetch stretcher-bearers. His conduct afforded a splendid instance of gallantry and self-sacrifice.

Nevertheless, the continuing horror of life at the front was affecting Arthur Stafford increasingly deeply, and Aidan Crawley also records how, when his father came home on occasional periods of leave, “he never talked about the war” and how, as a result, his family only realized the strain under which he was labouring when his hair began to fall out. In autumn 1917, Arthur Stafford was finally sent home on extended sick leave which lasted until summer 1918, when, at the request of Cavan, a Lieutenant-General since 1 January 1917, he resumed his Army Chaplaincy, this time with the HQ of the 48th (South Midland) Division in northern Italy, where it had been serving since 21 November 1917. After the Italian rout at the Battle of Caporetto (October–November 1917), Cavan became the Commander-in-Chief of the two British Divisions that were sent to the River Ilonzo in order to rebuild the North Italian front, and he made a decisive contribution to the Allied victory at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto (24 October–3 November 1918) – which brought the war in Italy to an end.

Arthur Stafford remained with the 48th Division until March 1919 and was mentioned in dispatches on 5 June 1919 (London Gazette, no. 31,384, 3 June 1919, p. 7,212). After his demobilization he worked until 1922 with the Church of England Men’s Society in the dioceses of Bristol, Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, and it was in this capacity that on 22 May 1921 he dedicated the War Memorial at Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, on which are carved the names of the 22 men of the parish – including that of B.R.H. Carter – who had been killed in action in World War One. From 1922 to 1924 he was Vicar of East Meon, Hampshire, and from 1924 to 1928 he worked in York as Chaplain to Archbishop Cosmo Lang and Clerical Secretary to the Diocesan Board of Finance, becoming an Honorary Canon and Prebendary of Givendale in York Minster. When Lang became Archbishop of Canterbury (1928–42), Arthur Stafford worked as Assistant Secretary to the Central Board of Finance from 1928 to 1929 and became an Honorary Canon of St Albans and Diocesan Secretary. But from 1929 to 1948 he was a Canon of St George’s, Windsor Castle, and in that capacity he acted as Chaplain-in-Ordinary to King George VI from 1944 until his death in 1948. He left £17,765 13s. 5d. (= c.£544,431 in 2017).

Arthur Stafford Crawley and Anstice Katharine (“Nancy”) on the Terrace at 4 Canons Cloister, Windsor Castle.

(Courtesy of David J. Hogg Esq., In Memoriam, p. 430)

On 31 July 1936 Aidan Merivale Crawley was commissioned Pilot Officer in the General Duties Branch of 601 Squadron (Auxiliary Air Force – later RAF), and transferred to flying duties on 1 November 1938 (London Gazette, no. 34,325, 22 September 1936, p. 6,080; no. 34,566, 1 November 1938, p. 6,823). He reached the rank of Flight-Lieutenant and was shot down over the Western Desert near Tobruk in July 1941 while serving either in No. 73 (Fighter) Squadron or as Commanding Officer of No. 34 (Fighter) Squadron, after which he was a PoW until May 1945. In 1945, he married Virginia Spencer Cowles (b. 1910 in Brattleboro, Vermont, d. 1983; OBE in 1947), a prominent journalist, travel writer, biographer and war correspondent, and went on to become a well-known journalist, television executive, editor, and also politician. He was the Labour MP for North Buckinghamshire from 1945 to 1951 but left the party in 1956 over the issue of Clause 4 and became the Conservative MP for West Derbyshire from 1962 to 1968. During the post-war Attlee administration he was Parliamentary Private Secretary for the Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1945 to 1948, a Delegate to the Council of Europe from 1949 to 1951, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Air from 1950 to 1951, and a member of the Monckton Commission on the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland from 1958 to 1960. From 1951 to 1960 he also worked in television; he became the Founder Chairman of London Weekend Television in 1967, and was the company’s President from 1972 to 1974; from 1975 to 1978 he made documentary films in conjunction with EMI Films Ltd. In 1972 he was President of the MCC.

Nancy and Arthur’s fourth child, Anstice, Lady Goodman (1911–2001), was also prominent in public life, most notably as Chief Welfare Officer for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration after World War Two.

Janet Blanche Gibbs

In 1915 Janet Blanche married William Otter Gibbs, the eldest son of Henry Martin Gibbs (1850–1928) and Emily Anna Gibbs (née Otter) (1854–1928) (m. 1882); Henry Martin was the sixth child and fourth son of William Gibbs (1790–1875) and Mathilde Blanche Gibbs (née Crawley-Boevey) (1817–87) (m. 1839). So Henry Martin was one of the three younger brothers of Antony Gibbs [II] and he lived with his large family (nine children) at Barrow Court, on the south-west side of Bristol and three miles north-west of Tyntesfield. Consequently, Janet Blanche (Eustace Lyle’s youngest sister) and William Otter were cousins.

William Otter was educated at Eton from 1896 to 1901 and the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) from 1901 to 1902, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 10th (Prince of Wales’s Own) Hussars in November of that year (London Gazette, no. 27,497, 21 November 1902, p. 7,534). He then served in India for nine years with the 5th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry – at Mhow (1903–06), where he was promoted Lieutenant with effect from 13 June 1904, and at Rawalpindi (1906–12), where he was promoted Captain with effect from 10 April 1907 (LG, no. 27,713, 13 September 1904, p. 5,913; no. 28,016, 26 April 1907, p. 2,813). From June 1912 to June 1914 he was attached to the Egyptian Army. He embarked for France on 11 August 1914, where he was attached to the HQ of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade. On 3 September 1914 he was attached to the 18th (Queen Mary’s Own) Hussars and he rejoined the 10th Hussars on 20 October, 12 days after the Regiment had landed at Ostend (LG, no. 29,017, 22 December 1914, p. 11,022). He was wounded at Hooge, east of Ypres, on 1 November 1914 during the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–30 November 1914), hospitalized in England, and promoted Major with effect from 4 February 1915 (LG, no. 29,084, 26 April 1901, p. 1,981). He returned to the Ypres Salient on 12 March 1915, was wounded for the second time near Potijze during the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915), and returned to France on 19 August 1915, where he was mentioned in dispatches on several occasions (LG, no. 30,072, 15 May 1917, p. 4,755). He became Commanding Officer of his Regiment with the rank of Acting Lieutenant-Colonel, but on 9 June 1918 he was seconded to the Tank Corps and was slightly wounded on 23 August and 17 October 1918.

In September 1919 he retired from the Army as a Lieutenant-Colonel and joined the Reserve of Officers. A resident of Somerset, he became a member of Somerset County Council from 1922 and a JP for Somerset (Long Ashton petty sessional division) from 1924. He succeeded his father as the Lord of the Manor of Barrow Gurney, and became Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Somerset in 1935 and High Sheriff of Somerset in 1936. From 1928, as a member of the Somerset Territorial Army Association, he commanded the 5th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry (TA) and became its Honorary Colonel in 1936. In 1938 he was made aide-de-camp to George VI. William Otter Gibbs left £9,583 18s. 10d. (= c.£201,085 in 2017).

Lancelot Merivale Gibbs

Lancelot Merivale had no direct connection with Magdalen, but he did have several indirect connections with the College via two of his older brothers, one brother-in-law, and three cousins who had studied there. His story is worth telling here in some detail for two reasons. First, his social background was not dissimilar to that of more than a few Magdalenses who were killed in action in World War One. Second, being a Regular Officer in a pukka regiment who became a Staff Officer during the Battle of the Somme, he took part in or was present at several major engagements when numerous Magdalenses became casualties and these are described in the extraordinarily detailed personal Diary that he kept, with one break, throughout he war. The Diary, interspersed with letters to and from the front by other members of the Gibbs family, forms the major part of David J. Hogg’s meticulously edited In Memoriam (pp. 129–417), and it makes fascinating reading – not least because so much of what is said there could have been said by many a well-educated subaltern from a prosperous upper middle-class family. The value of In Memoriam for researchers who are interested in the human side and personal cost of the Great War cannot be exaggerated.

Moreover, from time to time, Lancelot encountered one celebrated member of Magdalen – the “Pragger”, as the Prince of Wales was universally known in the ghastly argot of Edwardian Oxford. The Prince had studied at Magdalen without much enthusiasm or distinction from the start of the Michaelmas Term 1912 to July 1914, and would probably not have returned to the College even if the war had not happened, since, on his own admission, he had had enough of Oxford and wished to travel abroad. So when war broke out, he showed the same passionate enthusiasm for taking part in it that carried away so many of his generation, and after being delayed for several months by his father, he was finally permitted to join the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, which landed at Zeebrugge, Belgium, on 5 August 1914. In November 1914 he was attached to the Staff of Sir John French (1852–1925), the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force from 4 August 1914 to 18 December 1916. In May 1915 he was transferred to the General Staff of the First Army Corps, whose HQ was near Béthune, and in September 1915, a month after the formation of the élite Guards Division at Lumbres, near St-Omer, he was attached to the Staff of Major-General (later Field-Marshal) Frederick Rudolf Lambart (the 10th Earl of Cavan) (1865–1946), its GOC from 18 August 1915 to 3 January 1916 (see above under Arthur Stafford Crawley).

From autumn 1917 to May 1918 the Prince was with XIV Corps on the Italian front; from May to November 1918 he was back in France as a Staff Officer with the Canadian Corps; and he finally returned to Britain in February 1919. As the prince was a gregarious and persuasive young man whom it proved impossible to keep out of the front line whenever he was near it, Lancelot encountered the Prince reasonably often: his Diary mentions him 17 times, mainly casual meetings for brief periods of time in the course of duty. But on 27 December 1915, when Lancelot’s motorcycle ran out of petrol in the middle of nowhere, the Prince stopped his “large grey Daimler” and supplied him with a cupful. After that, their contacts were less formal: on 28 August 1916 and 7 September 1916 they dined together in a party, on 23 November 1916 they went on a shopping trip to Amiens with a group of friends, during which the Prince insisted on carrying most of the parcels, and finally, after an excellent dinner at Golbert’s Restaurant which went on until 23.00 hours, they were turned out by the local Gendarmes. On 1 October 1916, the Prince lent Lancelot his car – as he was willing to do “to any brother officer who could find the courage to ask for it” – so that he and Stafford Crawley could have a look at the village of Dromesnil, 47 miles to the south-west, where the next HQ of the 2nd Guards Brigade would be situated. And over the next two years they met on two more occasions: once in Lille on 26 October 1918 and once on 22 February 1919 at a formal reception in the British Embassy, Paris, to mark the Prince’s return to England when, Lancelot noted, he “talked to all”.

Like four of his brothers, Lancelot was educated at Pembroke Lodge Preparatory School from c.1896 to 1902, and Eton from 1902 to 1908, the year in which he began his military career as a Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, the Somerset Light Infantry (London Gazette, no. 28,212, 5 January 1909, p. 134). In December 1910 he transferred his commission to the 2nd Battalion, the Coldstream Guards, in 1911 he was awarded the Coronation Medal of George V, and in July 1913 his Lieutenancy in the Coldstream Guards was confirmed (LG, no. 28,444, 6 December 1910, p. 9,141). He left for France with the 2nd Battalion on 21 August 1914, part of the 4th (Guards) Brigade in the 2nd Division, and after arriving at Coulommiers on the River Grand Morin on 4 September, between 6 and 12 September his Battalion took part in the Allied advance from the River Marne to the River Aisne alongside G.M.R. Turbutt’s 2nd Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, part of the 2nd Division’s 5th Brigade. Between 13 and 29 September these two Brigades took part in the heavy fighting around Soupir, just north of the River Aisne, and on 12 October 1914, after the fighting was over, Lancelot mentioned in a letter to his eldest brother George Abraham that the three Coldstream Guards Battalions had suffered a “great loss of officers” during the fighting of the last few weeks (see Turbutt).

On 14 October 1914, together with the rest of the 2nd Division, the 2nd Battalion moved northwards by train towards Belgium, and on 21 October, the third day of the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–30 November 1914), the 2nd Battalion took up a position in the front line near Sint Juliaan that was only 400 yards from the German trenches and very close to Gheluvelt, where John Evelyn would be wounded and taken prisoner on 29 October. As Lancelot was clearly an efficient officer who looked after his men and kept his head in difficult circumstances, his Commanding Officer asked him informally on 17 November 1914 to take over as Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, a position which was formalized in April 1915 and back-dated to 9 March 1915, and which Lancelot held until April 1916 (London Gazette, no. 29,131, 13 April 1915, p. 3,684). On 17 November 1915 Lancelot discovered that his Battalion was in support of the 1/1st North Somerset Yeomanry, in which five of his brothers and cousins – Antony Hubert, Eustace Lyle, Guy Melville, Ralph Crawley-Boevey and Lionel Cyril (see details of the cousins below) – were currently serving, four of whom survived the war. By 21 November 1914 the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards was marching northwards, in very cold weather, towards Ypres, as part of the “Race for the Sea”. At c.05.30 hours on that day they reached Ouderdom, about four miles south-west of Ypres, and at c.11.30 hours they reached Méteren, some two miles west of Bailleul, in the very north of France and around ten miles south-west of Ypres. In the late afternoon of 23 November Lancelot met up with his five cousins who were in the NSY, and from 29 November to 7 December 1914, when he returned to Méteren, he was on leave in England.

After his return, he was promoted Temporary Captain, but nothing much happened to his Battalion until 22 December 1914, when it set off southwards towards Béthune, a distance of about 14 miles. After spending the night in a girls’ school, the Battalion left Béthune at 07.00 hours, marched in a north-easterly direction for six miles, and waited in the cold for three hours in order to take over water-logged trenches at a location that must have been very near to Neuve Chapelle (see F.L.F. Fitzwygram). As the cold weather persisted – as did sniper activity – and the trenches proved to be in poor repair, casualties slowly mounted up, and on 27 December 1914, when a German attack was expected and prepared for, it began to rain hard: “Not a good Christmas” wrote Lancelot in his Diary. But the weather got warmer; the front quietened down; and the men started to improve the state of the trenches with the help of the Royal Engineers, causing Lancelot to reflect in a letter to Nancy that although he and the Colonel lived in “a windowless and holey roofed house” that was “very cold”, it was at least “drier than the trenches”. Over the period around New Year, the weather became wetter and “rather colder”, and several of Lancelot’s friends were killed or badly wounded – “Dreadful all the best people being killed”. But in the early evening of 2 January 1915 the Battalion was relieved by a Battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment and marched to Locon, around six miles to the south-west and just north of Béthune. Here they stayed in “comfy billets after some very bad trenches” and did “a hard week’s work […] practising new forms of attack”, which involved going across to Hazebrouck in groups and learning how to use the new-fangled “bombs and hand grenades”. On 7 January 1915, in pouring rain, Lancelot accompanied his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Major-General Sir) Cecil Edward Pereira (1869–1942), to look at the Battalion’s new trenches at Richebourg St Vaast, about four miles over to the west. The rain persisted until 10 January, when the Battalion took over from the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards for a day in the trenches at the Rue de Bois. But after that they did very little of note until 25 January 1915, when news of a German attack at Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée suddenly arrived, causing the Battalion to be put on 20 minutes’ notice. The attack never materialized, however, and on 29 January Lancelot developed a high temperature and was hospitalized until 1 February, when he returned to his Battalion near Béthune. Here he learnt that it had been heavily attacked that morning and taken about 50 casualties, but that it had counter-attacked successfully near Cuinchy, where a bridge spans the La Bassée Canal, and had succeeded in retaking the lost trenches and capturing another 100 yards of territory. On 6 February 1915 the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards mounted a second counter-attack, rushed the nearby brickworks, and emptied several German trenches.

From 7 to 25 February 1915, when Lancelot was on leave in England once again, the 2nd Battalion’s sector of the front line was relatively quiet, and on returning to France at midday on 4 March, he found his Battalion in the same billets at 135 rue de Lille, Béthune, doing very little in preparation for the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) (see M.A. Girdlestone, Fitzwygram). During that battle, the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards simply waited around – either near Cuinchy on the banks of the La Bassée Canal, or in billets behind the line – and until 21 April 1915 (when a three days on – three days off routine began), the Battalion continued to lead a relatively peaceful life in the trenches. This new arrangement enabled the men to return to their billets for baths, changes of clothing, and occasional purchasing expeditions into Béthune, where it was also possible to get a decent haircut. There were, of course, still occasional losses to enemy shells and snipers. But in general the feeling was that the Germans had lost interest in this British section of the line and were now more concerned first, with the sections that were held by the French, and second, with the threat to the industrial regions of Silesia that had developed on the Eastern Front because of the Russians’ capture of the Austro-Hungarian fortress town of Przemyśl after a siege – the longest of World War One – that had lasted from 16 September 1914 to 22 March 1915.

On 26 April 1915 news of the 2nd Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915) started to trickle in, but it was not until 1 May that Lancelot noted in his Diary that the “Ypres show was a very bad one”. But four days later he also noted that it was “very quiet in our front” and on 13 May he remarked in a letter to his sister Nancy: “So far this fighting has not involved us at all and I don’t much think it will.” In saying this he was wrong, for the Battle of Festubert (15–27 May 1915), which took place around five miles south-west of Neuve Chapelle, was a series of confused attacks by British, Canadian and Indian troops which cost the Guards Battalions c.660 other ranks (ORs) and c.25 officers killed, wounded or missing, and gave rise to much heavier losses in the Indian Battalions. On 18 May, Lancelot’s Battalion was in Reserve, but by 22 May it had lost two men killed in action and 11 wounded, and on 28 May it moved back to Lapugnoy, some six miles west of Béthune. In a letter of 29 May 1915 to his brother George Abraham Gibbs, Lancelot wrote:

We had the most exciting and unpleasant and lucky 24 hours that I have had since I have been out here. We took over a bit of the line that had just been captured from the Germans. They did not feel like counter-attacking; but just shelled us for the whole 24 hours we were in, as hard as they could. I should think they must have put out between 4,000 and 5,000, as I counted 94 in one minute when they [were] coming rather quicker than usual.

He also noted that on 28 May the Germans sent a kite over the British trenches at nearby Givenchy to which the following message was attached: “We are too strong to retire, we have not enough men to attack, we are too proud to ask for peace, but we want peace and to go home.” But by this time, the weather had improved significantly and on 30 May 1915, Lancelot, accompanied by six friends (including A.H.E. Ashley), went for a ride in the Bois des Dames and tackled some gentle jumps at a local French cavalry school.

During the small hours of 31 May 1915 the 2nd Battalion, together with two other Battalions of the 4th (Guards) Brigade, began to march south-westwards for about six miles to Noeux-les-Mines, where it was billeted in the local Mairie and continued, as Lancelot put it in a letter to Nancy of the same day, to enjoy “times of rest”. The following day was, however, spent cleaning up the billet because, as so often in the view of the incoming British troops in both world wars, the French had left the place in a filthy state. But during the night of 6/7 June 1915, the 2nd Battalion relieved the 1/20th (Blackheath and Woolwich) Battalion of the London Regiment in well-kept trenches with “palatial dugouts” near Vermelles, around three miles due east of Noeux-les-Mines, where they stayed, with the weather becoming “hotter than ever”, until the small hours of 9 June. Until 27 June, the Battalion was in and out of trenches near Vermelles and Sailly-Labourse, two miles to the north-west, taking casualties from the German artillery. But from then until 5 July 1915 it did very little in Vendin-lès-Béthune, a northern suburb of Béthune, before moving back to the trenches just south of the La Bassée road at Cambrin, five miles to the east-south-east, which Lancelot described as “Not a very nice line, Germans so close [c.20 yards] and they bomb so much”. From 10 to 14 July 1915 Lancelot was a patient in No. 1 Clearing Hospital in a château near Choques, just north-west of Béthune, suffering from debilitation. But on 17 July, the day of his confirmation as Captain (London Gazette, no. 29,406, 17 December 1915, p. 12,651), he was back with the 2nd Battalion and relieving the 3rd Battalion in the trenches at Beuvry, on the eastern outskirts of Béthune, where he spent four quiet days before going on leave to England from 21 to 30 July.

After his return the weather was uninterruptedly hot and Lancelot’s 2nd Battalion spent three fairly uneventful weeks in and out of the trenches at Le Plantin and Le Quesnoy, near Béthune. But on 20 August 1915, together with the rest of the 4th (Guards) Brigade, the 2nd Battalion began a long march north-eastwards to Lumbres, eight miles west of St-Omer, in order to become part of the 1st Guards Brigade in the newly created Guards Division, whose GOC from 18 August 1915 to 3 January 1916 was Major-General the Earl of Cavan. This appointment was particularly welcome to Lancelot’s Battalion since Cavan had been a popular Commanding Officer of the 4th (Guards) Brigade from 14 August 1914 to 19 June 1915. But Cavan was also related to the Gibbs family via his first wife, Caroline Inez Crawley (1870–1920) (m. 1893), since she was the daughter of George Baden Crawley and the sister of Nancy’s husband Arthur Stafford Crawley (see above).

Lancelot’s Diary gives the impression that very little of importance happened during the first month of the new Division’s existence and that very little in the way of a training programme was organized for the men. On 12 September 1915 he was able to set off for England for a further period of leave, during which he was able to spend time with his family. He began his return journey on 21 September, rejoined his Battalion on the following day, and reached Nédonchel, 13 miles west of Béthune, on 23 September 1915, three days before the start of the Battle of Loos (26 September–8 October 1915). During the night of 25 September the entire 4th (Guards) Brigade route-marched in the pouring rain to Auchel, six miles west-south-west of Béthune. They arrived there at 09.00 hours and waited in bad billets until 13.00 hours before continuing the march in even worse rain, during which they had to wait by the side of the road for three hours. They then “moved on in jerks and stops” until, at 22.00 hours, they finally reached Noeux-les-Mines, some nine miles to the east, where, despite their c.20-mile march, the tired troops were once again assigned bad billets. Although, on 26 September 1915, the 4th (Guards) Brigade was supposed to act as the point unit for the entire Guards Division, it waited around all morning for a reason that Lancelot did not understand. And it was not until it was quite dark that the Brigade arrived on the all-important Hill 70, a low hill with bare sides in the front line where it was supposed to support the 21st Division, i.e. a good six hours after the British had launched a disastrous assault. Even to Lancelot’s inexperienced eyes, the 21st Division seemed to be “in a terrible muddle”, with “Brigades so congested that they didn’t know where any of their Battalions were. Men walking in every direction and kit lying thick in every trench”. And when Lancelot’s 2nd Battalion did get into the old German front-line trench – now the British second trench – they found it “full of men of all Battalions of 21st Division”, who were equally disoriented and confused.

In his excellent account of the Battle of Loos, Philip Warner endorses Lancelot’s assessment of the situation, and identifies seven major reasons for the confusion that reigned throughout the 21st Division at dusk on 26 September 1915: (1) the strength of the German defenders had been considerably greater than anticipated; (2) the same applied to the condition and strength of their unified trench system; (3) the British attack at 11.00 hours had not been preceded by an artillery bombardment involving gas and/or smoke shells; (4) because of this, the gaps in the German wire were narrow; (5) the British had attacked over open ground where they were an easy target for artillery and machine-gun fire; (6) the attacking troops belonged mainly to relatively untried formations of Kitchener’s New Army; and (7) many of their maps were unreliable or inaccurate to the point of uselessness.

So it was a relief for Lancelot’s 2nd Battalion when, at about 20.00 hours on 26 September 1915, they were ordered to occupy the front-line trenches even though they were in bad repair. Consequently, much of 27 September was taken up by the dangerous task of improvement, which cost the 2nd Battalion 18 casualties. During the night that followed, the 2nd (Guards) Brigade took up position on the 2nd Battalion’s right and the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards took up position on its left, but when, during the afternoon of 28 September, the 2nd (Guards) Brigade mounted an attack on Puits 14 bis (Shaft 14a), it made little progress because of determined German resistance and heavy machine-gun fire, with the result that one of its constituent Battalions, the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, suffered heavy losses. On 3 October 1915, the Germans recaptured the Hohenzollern Redoubt, a German defensive strongpoint near Auchy-les-Mines, about six miles east of Béthune, and on 8 October they tried once again to retake lost ground but gave up after suffering heavy losses – bringing the first phase of the Battle of Loos to an end.

Lancelot’s Battalion was involved in the heavy fighting on both days, and in one of the three letters that Cavan wrote to his wife Inez on 9 and 10 October 1915, he commended it – together with the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstreams, the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Guards and the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards – for the victory, which, he wrote, had cost the Guards Division 526 ORs and 19 officers killed, wounded or missing. He also made special mention of the key part played by “bombs” (hand grenades), over 9,000 of which had been thrown during the fighting on 8 October. At 17.00 hours on 12 October, Lancelot, “very glad to be ‘shot’ of some of the beastliest trenches he had ever been in”, marched with his Battalion some eight miles north-westwards to Verquin, just south of Béthune, where “fairly good billets” awaited them. But at 14.00 hours on 13 October 1915, the 46th (North Midland) Division re-opened the fighting by assaulting the Hohenzollern Redoubt – unsuccessfully, according to Philip Warner, “through lack of hand grenades”. Then, at 14.30 hours on the same day, the Germans counter-attacked and retook the Redoubt in a bloody battle that lasted from 13 to 15 October 1915 and cost the 46th Division between 3,643 and 3,763 of its members.

On 15 October 1915, the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards returned to their billets at Vermelles and spent two days cleaning up before going up to the front line again on 19 October, the day when the Battle of Loos finally ended. But by 19.00 hours on 21 October 1915 they had returned to Vermelles, and from then until 20 November, when it took over from the Regiment’s 1st Battalion in the front line at Pont du Hem, the 2nd Battalion rested, played games, enjoyed various forms of entertainment, and did a certain amount of training. On 24 November 1915, Lancelot set off for yet another two weeks’ leave in England, and after returning to France on 8/9 December 1915, he did a stint in the trenches. On 14 December 1915 he began as Acting Staff Captain to the 1st Guards Brigade and confessed in his Diary that he was “very frightened” at being in the presence of so many senior Generals, and on 17 December 1915, when he had been left alone in Brigade HQ, he noted that the “Divisional General came in and asked several questions. Luckily I knew the answers to all”. Sometimes, as on 20 and 27 December 1915 and 12 and 25 January 1916, Lancelot’s work involved visiting various Battalions using unreliable, not to say dangerous, forms of transport. On Christmas Day 1915 Lieutenant-General Cavan left the Guards Division to become GOC IV Corps, and at midnight on 31 December 1915 the two opposing sides wished one another “A Happy New Year” by exchanging fire for a minute or so.