Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 18 June 1891

Died: 3 May 1918

Regiment: Lancashire Fusiliers and Royal Air Force

Grave/Memorial: Ramleh War Cemetery: CC.58

Family background

b. 18 June 1891 at “Preswylfa”, the Cliff(e), Llanbeblig, Caernarfon (formerly anglicized as Carnarvon), Gwynedd (cf. the photograph of his grave at the very end of this biography). He was the elder son (of five children) of John Williams [III] (b. 1857, d. 1917 in the Asylum, Denbigh) and Sarah Anne Williams (née Griffiths) (1863–1951) (m. 1890). At the time of the 1901 Census the family had two servants, but by the time of the 1911 Census this figure had dropped to one.

One of the very few known photos of William Humphrey Williams, which was taken outside the east front of the neo-Grecian St George’s Hall, Liverpool (opened 1854), on 25 September 1913 when he, his father and his brother were taking part in a concert there that was being given by the Carnarvon Choir. The small boy in the front row is John Arthur Julian Williams, William’s brother. His father, John Williams, is standing behind the boy’s left shoulder, and William Humphrey himself is standing behind John Williams’s left shoulder.

(Photo courtesy of T. Meirion Hughes at Caernarfon Ddoe /Caernarfon’s Yesterdays)

Detail from the above photo

St George’s Hall, Liverpool

Parents and antecedents

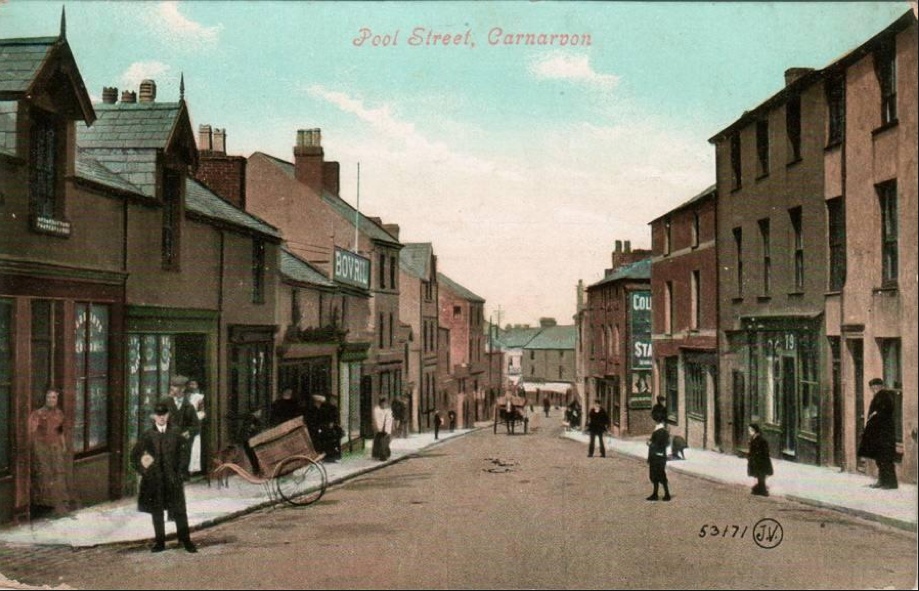

Williams’s paternal great-grandfather John Williams [I] (b. 1782, d. 1867/8 living with his second son, Humphrey) was a blacksmith, whose smithy stood on Castle Square, Caernarfon, “before any houses were built on the road that led from the front of the square up to Henwalia, the base of ancient Segontium”. He was a proficient musician, “being the leading man in Llanbeblig choral and congregational singing, when the bass violin and other string instruments were accessories to the music before organs and harmoniums had penetrated these parts of Wales”. John [I] also composed several tunes for use by congregations, including ‘Pool Street’, which was often used at funerals in the Caernarfon area to accompany the hymn entitled ‘Cyfaill yn y Glyn’ (‘A Friend in the Glen’). John [I] had four sons and one daughter: John [II] (b. c.1811, d. 1876 in Llandudno); Humphrey (1818–83); Robert [I] (b. c.1822, d. 1891 in Llandudno); William (b. before 1822, d. before 1891, and possibly 1876 in Liverpool); and Anne (later Edwards) (b. after 1822, d. before 1891 in Caernarfon or Llandudno).

John Williams [II] was clearly the most successful of the five: like his brother William, he was educated in Liverpool, but was then apprenticed back in Caernarfon. He then became the assistant to an uncle who was Land Agent of the Mostyn Estate in Flintshire, north-west Wales (i.e. the property of the Mostyn Baronetcy that had been created in 1660), and he succeeded his uncle in that capacity in 1827 at the extraordinarily early age of 16. He flourished in this role, married a local girl in c.1838, and in 1849 acquired the lease of Bodafon Farmhouse, one of the largest farms in the area, which occupied 173 acres across two parishes and employed ten servants at the time of the 1851 Census. John [II] played a central part in helping Edward Lloyd-Mostyn (the 2nd Baron Mostyn; 1795–1884, MP for Flintshire, which was much larger in the nineteenth century than it is today), in 1831–37, 1841–42 and 1847–50, to transform 955 acres of the estate (in which Llandudno – “hardly more than a small fishing village” – was situated), into an up-market “watering place”. He may also have been the anonymous author of the first tourist guide to Llandudno, and he was certainly the first “to suggest that the town should be incorporated by Act of Parliament” – The Llandudno Improvement Act was passed by Parliament in 1854. It was he, too, who “through the medium of several influential journals published in Liverpool and elsewhere, caused to be circulated numerous articles descriptive of the natural beauties and healthful advantages” of the new holiday resort.

John [II] became what in contemporary parlance would be known as the local “Mr Big”, for he was “intimately concerned with every public undertaking and every public board in the neighbourhood”. For 34 years he was a Guardian of the Poor and for 27 of them he chaired the committee; from 1856 until his death he was the Secretary of Llandudno Gas and Water Company; he was the Secretary of Llandudno’s Market Hall Company, Hydropathic Centre, Turkish Baths, and Public Baths; he was the Agent for the Ty Gwyn and Old Mine Companies; and he managed the estates of several local gentlemen; he was one of the Managers of Llandudno and Eelwys Rhos National Schools, thereby “largely contributing towards educating the children of the lower classes of the place”; and he was the Honorary Secretary of the Lifeboat Institution from c.1862 until his death. A religious man, he was, for 36 years the Rector’s Churchwarden at St George’s Church, the parish church of Llandudno from 1840 to 2001 (now a business centre), and for 40 years he acted as the Parish Clerk; he was also the President of the local Bible Society, “a branch of which he was the first to introduce into the town”.

Described in one obituary as “an honourable, unambitious, and upright man”, it was said that John [II] had “a large number of private friends who will not soon forget his help in time of anxiety or trouble, or his geniality in the circle in which he moved”. Another obituary said that he “held no ordinary place in the opinions of his fellow townsmen” and that “in every matter that had a tendency to further the interests of the town and to increase its welfare, his services were always first solicited”. Indeed, “‘what does John Williams think?’ was the first question that was asked of any fresh undertaking” and as his influence grew, “the fact that he had approved of a scheme inspired confidence in its success”. As a mark of gratitude for his public service, he was made Deputy Constable of Conway Castle and Mayor of Conway, and in September 1859 the worthies of Llandudno and the surrounding area expressed their appreciation by organizing a Testimony on his behalf. They raised over £300 (= £1,300 in 2005), some of which was used to buy John a silver tea and coffee service that was “both useful and ornamental”, and some of which the committee used at his own request to buy a gold watch for his wife and each of his children. The gifts were presented at a formal dinner, presided over by one of the Mostyn family, that took place on Monday, 31 October 1859.

However, on 11 June 1864, in the midst of all this progress and new prosperity, the North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality published a wittily satirical, albeit reasonably good-natured, exposé of some of the failings of several of the presiding “local divinities”. One of these was, inevitably, John [II], whose influence was said to be exercised to such an extent “that even a new shower-bath to be invented by any more brilliant genius than [is] common in Llandudno […] would not be patented unless Mr. John Williams of Bodafon had the first pull at it”. Nevertheless, the pseudonymous writer identified three matters that were deserving of complaint: (1) the steepness of a local hill that had been worsened for travellers by the insertion of an extra barrier at John [II]’s behest and that was even harder to negotiate than the three extant ones; (2) the growing uncleanliness and unhealthiness of the small back streets of Llandudno “between the Parade and Mostyn Street”, whose drainage was defective and which were “fast degenerating into a dirty mass of small, close-packed houses”; and (3) the nuisance that was caused, especially during the heat of summer, by the common practice of keeping pigs in back yards, combined with the absence of a properly regulated municipal slaughterhouse. “Verily,” the writer concluded, “our household Gods might see to these small matters with profit.”

Several of John [I]’s children inherited his musical gifts and interests. Robert [I] was a talented member of several church choirs in the Llandudno area. He began his working life as a shoemaker and prospered, living in Llandudno from c.1841 until his death, and ending up owning both the Royal Hotel in Church Walks and the Nevill Hotel, Vaughan Street, near the railway station. But Humphrey, Williams’s paternal grandfather, was probably the most distinguished amateur musician of the five. An obituarist described him as “one of the pioneers of singing in North Wales” and he became well-known locally as the conductor of the choir that called itself “The Welsh Harmonists”. In c.1854–56, when Humphrey was established as a jeweller and (master) watch- and clock-maker, he married Ann Jones (b. c.1822, d. 1866 in Llanbeblig, possibly a victim of the cholera epidemic of 1866/67), and by the time of the 1861 Census the family was living at 160, Pool Street, Llanbeblig, Caernarfon. But after Ann’s death, when the children were between six and ten years old, the family moved a short distance to 20, Castle Square, Llanbeblig, Caernarfon. In 1895 Slaters Directory recorded that this address was occupied by “Williams & Pritchard, Watchmaking & Music Warehouse”, an indication that after Humphrey’s death his inheritors had extended the original business to include things musical, and for ten years, starting on 1 January 1905, the ground floor was leased to E.H. Owen and Son, Auctioneers. Humphrey left £1,155 (c.£80,000 in 2005).

Pool Street, Caernarfon (probably during the Edwardian period)

Williams’s father, John Williams [III], was Humphrey Williams’s oldest child (of three sons and two daughters). The other two sons were Howel (c.1861–1921), who became a well-travelled sea-captain despite his proficiency as a violinist, for which, aged 16, he was awarded a gold medal at the National Eisteddfod at Caernarfon in 1877; and Robert Humphrey (1859–1948), who became the surveyor of the Vaynol Estate at Port Dinorwic (now Y Felinheli, between Caernarfon and Bangor on the Menai Strait). John [III] not only began his working life as an apprentice watchmaker and inherited his father’s musical gifts, he was also endowed with a great deal of creative energy. For example, when he was eight he began to learn the piano with Dr Roland Rogers (1847–1927), the cathedral organist at nearby Bangor from 1871 to 1891, and he grew to be a very distinguished church organist, music teacher and choirmaster who was, allegedly, “known to every Welsh singer”; his exceptional abilities in the latter role were recognized “over a wide area”. But he was especially well-known as a musician in North Wales, where he also enjoyed a reputation as an adjudicator in musical competitions and Eisteddfodau, and conductor at Church of England musical festivals. He was, with some justification, sometimes referred to by the honorific title of Professor of Music, and in June 1914 he described himself as “one who took an interest second to none in choral and congregational church music”. One obituarist, echoing the judgements of others, ascribed John [III]’s success to his talent “for analysing a piece of music and teaching the members of the choir to sing it exactly in the way the composer had intended it to be sung”, paying particular attention to the words. Expatiating further, he concluded:

[Williams] took the trouble to explain the meaning of the words in detail, the way to pronounce them and where to put the stress. He believed that the music be the accompaniment for the words. He took pains to explain to a choir the meaning of the words and laid stress on proper articulation. After a choir had mastered the music fairly well he would take up the words and every sentence would be given due attention. Though the training was at times monotonous it was very successful, as after results proved. If he was not satisfied with the ensemble he would ask each of the four voices to sing a given portion, and if he could not get the desired effect, or if he detected a mistake, he would call upon individual members to sing it.

His career as a trainer and conductor of choirs went back to 1875, when he was only 19 and founded the Cymdeithas Goraul Caernarfon (Caernarfon Choral Society) “with the object of performing oratorios”. In 1876 the choir took part in the National Eisteddfod at Wrexham and won first prize, and then, on numerous occasions, repeated the achievement elsewhere – mainly in the Principality of Wales but also at the London Eisteddfod on two occasions (see below). In 1886, 1894 and 1906 he trained and conducted the choir that sang at the National Eisteddfod in Caernarfon, and in 1910 he did likewise in Colwyn Bay; in 1888 the choir won first prize in the chief choral competition at the National Eisteddfod in Wrexham for the second time; in 1891 it won second prize at Swansea; in 1892 it won first prize at Rhyl; in 1898 it shared the first prize with Builth Wells at Blaenau Ffestiniog; and in 1909 it won first prize in London once more, this time in the Albert Hall (see below); it came first at Wrexham for the third time in 1912. When the Caernarfon Choir “carried all before them” and took the first prize at Rhyl, their singing was deemed to be “of such exceptional merit” that it gained “the unqualified commendation of adjudicators and audience” and was later declared to be “the most signal success achieved by a choir trained by Mr Williams”.

But perhaps John [III]’s most spectacular triumph as a conductor and choirmaster took place in London on Tuesday 15 June 1909, when the choral competition associated with the Welsh National Eisteddfod took place in London’s Royal Albert Hall. Seven choirs (of which one dropped out), each numbering between 160 and 200 members, entered the competition, and they were required to sing three test pieces. The adjudication was surprisingly tough and to the point, and the Caernarfon Choir “created a surprise in musical circles” by winning a “fine victory over the principal South Wales choirs” (scoring 273 out of a possible 300 points, winning them the first prize of £150) while the Llanelly Choral Society were the runners-up (scoring 243 points, winning them the second prize of £50). An Adjudicator read out the results with considerable sternness on behalf of the other judges – one of whom was the organist and composer Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924), a founder professor of the Royal College of Music in 1882 who taught music there for the rest of his life and who was well-known for his quarrelsomeness, sharp tongue, and intense dislike of vulgarity and musical modernism. He ascribed the Caernarfon Choir’s prize-winning performance to its ability to catch the serious mood of the major test piece – ‘Come, ye Daughters’, the opening chorus of J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion – and combine a near perfect sense of intonation with an ability to make its voices fill “the vast space” of the Hall. In contrast to the other five choirs, he said that the Caernarfon Choir possessed “musicianship and confidence, and the texture of the counterpoint was all revealed” and rammed the point home by giving most of the other choirs something of a ticking off! A musically trained member of the Caernarfon Choir concurred with the judgement in print a few days later and ascribed its success solely to the skill of its conductor:

I am convinced that the teaching of our conductor displayed an intimate knowledge of the Sebastian Bach resonance and that he was in perfect touch with this class of music. I attribute the success of our choir to a better intelligence of phrasing, a better and more sonorous tone throughout, together with the production of closer harmonies.

And The Musical Herald wrote that

The Carnarvon Choir at once impressed everybody by their delightful smoothness and tenderness, with plenty of gradation of force, neat moving together, more like a quartet than a big choir. […] In my opinion, as well as that of the judges, this choir was quite ten per cent. better than the best of the South Wales choirs present in this competition. It was the only choir from North Wales.

Caernarfon Choral Society, the winners of the Chief Choral Competition, National Eisteddfod of Wales (London 1909); John Williams [III] is sitting in the middle of the front row, holding his conductor’s baton

The choir itself were, of course, delighted with their success, which gave rise to “a scene of wild enthusiasm outside the Albert Hall. [The members of the choir] lifted their conductor shoulder high as soon as he appeared outside and would have carried him away had he not been obliged to go for the Prize.” On the day after the competition, David Lloyd George (1863–1945), the then Chancellor of the Exchequer (1908–15), showed the choir round the Houses of Parliament and, together with his wife and one of his daughters, entertained them for tea for two hours in 11 Downing Street, where the choir responded with impromptu solos by individuals. It concluded its stay in London with a concert at the Surveyors’ Institution, 12 George Street, Parliament Square. So when, at 6 p.m. on the Wednesday, John Williams [III] arrived at Colwyn Bay railway station for his weekly rehearsal with the town’s choir in the Church Room there, he was taken to a friend’s house in ignorance of what awaited him later. Three charabancs had been sent to Old Colwyn to fetch the Old Colwyn Silver Band, and when John [III] had been taken as far as Marine Road in a carriage, he was greeted by the band playing ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes’ from G.F. Handel’s oratorio Judas Maccabeus. A procession formed led by the band, and the hero of the hour walked to the rehearsal room through streets lined by hundreds of cheering people. At the top of Station Road a lady from the crowd gave him a beautiful bunch of roses and at the Church Room itself, an informal celebration of the choir’s success took place at which a local dignitary gave a speech in which John [III] was described as the “wizard” of North Wales. The great crowd responded by raising “cheer after cheer for Mr Williams” and singing ‘For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow’.”

John Williams [III]’s remarkable musical talents attracted attention from the very top of British society. For on 26 June 1896, when the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII (1841–1910; reigned 1901–10) was installed as Chancellor of the newly founded University of Wales (established 1893), John [III] was honoured by being selected to lead the choir on that occasion. And when, on 25 April 1899, the Duke of York (the future George V; 1865–1936; reigned 1910–36) and his German-born wife Princess Mary (May) of Teck (1867–1953) visited Caernarfon during their official visit to North Wales, John Williams [III] was invited to conduct his Côr Meibion Brenhinol Eryri (Snowdonia Royal Male Voice Choir, formed in 1897 from singers from Caernarfon and Llanberis) at a concert in Caernarfon Castle, which, after centuries of neglect, had been restored by the British public purse during the three final decades of the nineteenth century. The venue was politically highly significant, for the very first Prince of Wales, later Edward II (1285–1327; reigned 1307–27), was reputed to have been born in its Eagle Tower exactly 615 years previously, and shortly after his birth he was presented by his father to the Welsh as their Prince who could speak no English. Apparently the Duke of York so much enjoyed the performance of “several national airs” that he requested, perhaps for political reasons, an encore of the National Anthem and some hymns in Welsh, after which the conductor was formally presented to him.

So it is perhaps not surprising that when, on 24 November 1899, during one of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s (1859–1941) not infrequent visits to the British Court to see his grandmother, accompanied by Count Bernhard von Bülow (1849–1929; the German Foreign Secretary 1897–1909 and future Chancellor 1900–09), John Williams [III] and the Caernarfon Choir, numbering 50 singers “from quite humble walks of life”, were summoned by the future King Edward VII to perform in St George’s Hall at Windsor Castle before the Kaiser and Kaiserin and a range of honoured guests (though the Queen herself could not attend because of a family bereavement). The choir sang the National Anthem twice (once in Welsh – “a musical and open tongue” – and once in English), both settings arranged by John Williams [III]; the March of the Men of Harlech, also arranged by John; Grieg’s ‘Recognition of Land’ (solo and chorus); Gwylim Gwent’s ‘Nyni yw’r meibion cerddgar’ (‘We are the Music Makers’ (part-song and chorus); Saintis’s ‘On the Rampart’ (chorus); a selection of Welsh melodies, arranged by John’s old teacher Dr Roland Rogers; ‘Hen wlad fy nhadau’ (‘Land of my Fathers’) (solo); De Rille’s ‘Martyrs of the Arena’ (chorus); and ‘God Bless the Prince of Wales’. The audience were so delighted by the singing, that they afterwards presented the conductor with a baton studded with diamonds, and the Kaiser allegedly complimented the choir “for opening their mouths like Germans”! Repetitions of the royal concert programme followed.

John [III]’s concert at Windsor would not be his last Royal Command Performance for, on 13 July 1911, he made the Caernarfon Choir famous “throughout the length and breadth of the land” when they performed for the waiting crowds in advance of the ceremony at Caernarfon Castle during which the future Edward VIII (1894–1972; Magdalen 1912–14) was instituted as Prince of Wales in the presence of the new King and Queen. According to one obituarist, John [III] led the choir’s 30 members, dressed in national costume, as they “beguiled for us something more than pleasantly the hours of waiting” by performing an unaccompanied selection of Welsh vocal music “which had been selected for its representative qualities as well as for its beauty”. The choir then led the singing during the more formal part of the proceedings, which, thanks to pressure from David Lloyd George, had taken place for the very first time away from the Palace of Westminster.

Castle Square, Caernarfon on the day of the Investiture of the Prince of Wales on 13 July 1911

Edward, Prince of Wales, aged 17, at the Investiture with the King and Queen. To his credit, he thought he looked silly in his ceremonial garb

A panoramic view of the Investiture in Caernarfon Castle: the choirs seem to be ranged on a dais behind the podium in the centre of the photo

Despite his passionate concern for Welsh choral culture, John Williams [III] demonstrated on 21 June 1913 that his national loyalties were less narrowly focused when he conducted a male voice choir of 1,000 “picked male voices” from the four Welsh dioceses of Bangor, Llandaff, St Asaph’s and St David’s, bolstered by singers from Welsh parishes in London, when a huge demonstration against Mr Asquith’s Liberal Government’s Welsh Church Bill took place in London’s Hyde Park between 4.30 and 6.30 p.m. The Bill was part of a century-long campaign by Welsh nonconformists who objected to paying tithes to the Church of England to disestablish the established Church of Wales and replace it by the Church in Wales. Three days earlier, on 18 June 1913, the Bill had nearly been thrown out by Parliament, but in the end had gone through by 99 votes. At about 4.30 p.m. 18 processions – an estimated 120,000–125,000 men and women from all walks of life – which had begun from various starting points throughout London and represented 922 of the 1,097 parishes in the dioceses of London, Southwark and St Alban’s, began arriving at Hyde Park, where they assembled around 12 platforms from which, starting at 5.30 p.m., they were addressed by ecclesiastical and secular dignitaries. The report in The Times set much store by the simplicity, earnestness and determination of the “simple, clear-cut resolution” that was passed at the end of the meeting: “We will not have our Church dismembered and four of its dioceses disestablished and disendowed.” The part played by the massed choir was deemed “a notable feature of the proceedings”, for it sang ‘O God, our Help in Ages Past’ at the beginning and ‘The Church’s One Foundation’ at the end, when the meeting broke up peacefully at 6.30 p.m., even while the individual processions were still arriving. Despite such vocal opposition to the Bill, it received the Royal Assent on 18 September 1914, but because of the war did not come into force until 31 March 1920.

John Williams [III] was also associated with several other choral organizations, in and outside of Caernarfon. When Dr Roland Rogers resigned his post as organist at Bangor Cathedral in 1891 because of disagreements with the Dean, his Arvonic Male Voice Choir was also disbanded. But several of its members helped John to form the nucleus of the Côr Meibion Brenhinol Eryri, of whose achievements we have already heard. John [III] also, on occasion, conducted several classic oratorios such as Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s Elijah, but perhaps his other major achievement as far as the cultural life of Caernarfon was concerned was to help set up and run the Caernarfon Operatic Society, probably in the mid- to late 1890s. The quality of the Society’s productions got better and better, and in May 1908 a newspaper critic commented: “I really think that Carnarvon ought to be proud of the Society, for I doubt whether any other town of its size in the kingdom could carry out such work with such conspicuous success without going outside a small radius of the town for its principals, chorus, or orchestra.” He also noted that by May 1908, the Society had performed six operas by Gilbert and Sullivan: Trial by Jury, HMS Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado, The Gondoliers and one other, as yet unidentified. John not only sang the main male parts, but was also the society’s Musical Director and Stage Manager, while his eldest son’s old friend and employer, A.W. Kay-Menzies (1890–1960), had become the society’s Business Director (q.v.). Profits from the earlier productions went towards the building of the Caernarfon Cottage Hospital, which opened in 1900. Although the critic cited above was very appreciative of John Williams’s work, he also made the following, perceptive comment:

[his] intonation was doubtful on several occasions, while his voice seemed a trifle worn throughout. What surprises me, however, is that he is able to do so well, considering the tremendous amount of work he undertakes. He was musical director, stage manager, and took the leading roles of both operas [Trial by Jury and HMS Pinafore] on this occasion. Could not this multiplicity of work be avoided in future? I throw out this suggestion in the kindest of feelings, believing as I do that both Mr. Williams and the Society would benefit if they were adopted.

But the far-sighted warning was not heeded, and from 1915 John [III] would pay a high price for the stress that was caused by his many-sided work. The continuing successes of John Williams [III]’s choir caused its reputation to spread beyond the borders of Wales, and it was invited to perform in such venues as Liverpool (see the photo above), Kettering, Northampton and Wolverhampton. But its conductor never lost interest in his immediate locality, where he was also a Freemason and a Major in the 1/6th (Caernarvonshire and Anglesey) Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers as well as the paid organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Caernarfon, from 1880 until May 1915, when the “serious breakdown in health” that was dimly foreseen by the anonymous newspaper critic of 1908 forced him to retire, aged 58. On learning of this decision, the municipality set up a committee to organize a testimonial on his behalf which “sought the co-operation of patrons of Welsh music” both inside and outside of the Principality of Wales, and raised over £500. John Williams [III] died in the Denbigh Asylum on 25 November 1917 and his funeral on 30 November was very well attended: the route from Llanbeblig Church to the parish graveyard where he is buried was “thickly lined with people”; and the congregation sang his two favourite hymns – ‘O God our Help in Ages Past’ and ‘Marchog Iesu yn llwyddiannus’ (‘Onward March, All-conquering Jesus’). The report in the local press then continued: “At the graveside the Carnarvon Choral Society sang very impressively the old Welsh hymn ‘Cawn esgyn o’r dyrys anialwch’ (‘The comfort of journey’s end’) and a bugler of the Royal Engineers sounded the ‘Last Post’”. David Lloyd George, Britain’s Minister of Munitions from 25 May 1915 to 9 July 1916 and Prime Minister from 6 December 1916 to 19 October 1922, said of John Williams [III] when he heard of his breakdown: “There are few men to-day who could point to such a series of successes as those achieved by Mr. John Williams in his sphere.”

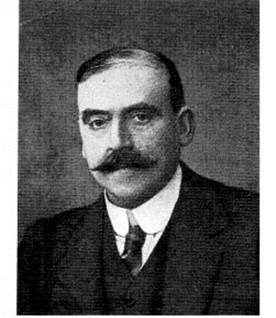

Mr John Williams [III], Late Conductor of Caernarfon Choral Society (The Musical Herald [January 1918])

Williams’s mother Sarah Anne was the daughter of a Caernarfon Councillor, the corn merchant William Lloyd Griffiths (1824–96), and his wife Catherine Ennor Julian (1841–1926), and on John Williams [III]’s death – he left £1,528 10s. 6d. – she was awarded a pension from the Civil List.

Christ Church (1862) now ‘Yr Hwylfan’ (‘The Fun Centre’), Caernarfon, Gwynnedd

Poster advertising the National Eisteddfod of Wales that was held in London’s Royal Albert Hall on 15–18 June 1909

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Kathleen Roberta (1883–1977);

(2) Millicent Margaret Ennor (1887–1972); later Cowan after her marriage in 1927 to Richard Hamilton Cowan (1897–1941);

(3) Eva Julian (1899–1993); later Whitworth after her marriage (1925) to Millington George Harold Whitworth (1898–1990);

(4) John Arthur Julian (1902–87) married (1926) Gladys Lye (1901–80).

Kathleen Roberta never married.

Richard Hamilton Cowan was the son of Dr Richard Hamilton Cowan (1857–1900) and Laura Hamilton Cowan (b. 1861, date of death unknown; possibly died in Canada). Late in World War One, he joined the Navy as a Midshipman and became a Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve on 1 March 1919. In May 1927 he was posted to the HMS Excellent, the naval gunnery school that was based on Whale Island, Portsmouth, Hampshire. Between that date and 1933 he was the Gunnery Officer of the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland (1926; scrapped 1959), which served on the China Station from 1928 to 1938 and played a decisive part in the Battle of the River Plate (13 December 1939), which led to the scuttling of the German surface raider the Graf Spee. During World War Two he served on HMS Wasp, from 1940 to 1941 the HQ of 43 Coastal Defence Craft that was based in the Lord Warden Hotel, Dover, where he died on 22 May 1941. He is buried in the Naval Reservation, Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery, Kent, Grave 1332.

The Lord Warden Hotel, Dover (HMS Wasp) (1921)

Millington George Harold Whitworth attested on 2 June 1916 and was mobilized on 6 November 1916, the day when he was attached to 203(S) Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery. He served on the Continent, ending up as part of the occupation forces in Cologne, and was demobilized on 4 December 1919. In 1919 he gave his home address as Osborne Mount, Osborne Road, Wallasey, Cheshire.

John Arthur Julian was a salesman and ended his professional life as a Sales Manager.

Education, engagement and professional life

Williams came to Magdalen College School as a Chorister in 1902, remained as a Chorister until his voice broke in c.1905, and stayed at the school as an ordinary boarder on a special scholarship until 1908, having taken the Oxford and Cambridge Junior Certificate Examination. He initially worked with A.W. Kay-Menzies (1890–1960) at the Alexandra Slate Quarry at Nantile, Gwynedd, opened in the 1860s and owned by the Amalgamated Slate Association Ltd, Caernarfon. He was subsequently apprenticed to Turner Bros, the highly successful firm of asbestos manufacturers which later changed its name to Turner Brothers Asbestos Company. The firm had been founded in Spotland, Rochdale, Lancashire, in 1871 and in 1879 it became the first business in Britain to weave asbestos cloth using power-driven machinery. In 1913 it moved its base of operations to Trafford Park, Manchester, where it continued working until it became defunct in 1998.

The Alexandra Slate Quarry, Nantile, Gwynedd

It is possible that while Williams was working in Rochdale he became acquainted with Edith Ormerod (1894–1962), the elder daughter of Thomas Pickles Ormerod (b. 1858 in Rochdale, Lancashire, d. 1911 in Opawa, Christchurch, New Zealand), a tanner and leather merchant, and Alice Mary Ormerod (née Duckworth) (b. 1862 in Rochdale, d. 1916 in Rochdale). Edith and her mother had previously lived in Christchurch, New Zealand, and almost certainly returned home to the Rochdale area after Thomas Pickles’s death in 1911, where they lived at Fern Bank, Castleton, Lancashire. Williams’s engagement to Edith was announced in Flight on 9 May 1918, i.e. about a week after his death (see below). Edith later (1922) married James Caldwell Alexander, MC (1884–1959), and had a son and a daughter.

James Caldwell was the son of a “dry salter” and worked as a clerk in the offices of a methylated spirits and varnish manufacturer whose factory was in Eccles, a western suburb of Manchester. When war broke out, he trained with the 1/7th Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Lancashire Fusiliers, applied for a Territorial Commission on 28 October 1915 and was gazetted Second Lieutenant in that Brigade with effect from 16 November 1915 (London Gazette, no. 29,402, 14 December 1915, p. 12,457). But on 14 October 1916 he had already landed in France, attached to the 7th (Service) Battalion of The King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment), which had been there on active service since July 1915. In 1917, Caldwell won the MC “for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty whilst in command of a raiding party. He led his men so close under our barrage that a complete surprise was effected, in spite of uncut wire, and the raid was successful, largely owing to the coolness, determination, and fine leadership of this Officer” (London Gazette, no. 30,234, 18 August 1917, p. 8,357). On 31 July 1917, when he was back with the 1/7th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers and in the Ypres Salient, he was wounded by a gunshot in his left shoulder for which he required extensive electrotherapy and massage treatment; and in March 1918 he was quite badly injured in the left heel, leg and hand while playing games. As a result he was sent back to Scarborough, North Yorkshire, where he was judged to be fit enough for Home Service duty only.

Military and war service

Williams trained at Southport and Crowborough and on 1 September 1914 he was commissioned Temporary Second Lieutenant in the 1/6th Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Lancashire Fusiliers, and on 7 December 1914 he was promoted Temporary Lieutenant (London Gazette, no. 28,995, 4 December 1914, p. 10,308; LG, no. 29,027, 1 January 1915, p. 129). But the Battalion, which had been raised on the outbreak of war with Germany at Rochdale, Lancashire, had embarked at Southampton in the SS Saturnia (1910; scrapped 1928) on 9 September 1914 and arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 25 September 1914 as one of the four Battalions that constituted the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade (the other three being the Regiment’s 1/5th, 1/7th and 1/8th Battalions).

SS Saturnia (1910–28)

This Brigade formed part of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division, Britain’s first Territorial Division to go overseas during World War One, and together with the 10th and 11th (Indian) Divisions, the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade, and the Bikaner Camel Corps, its initial task was to train in the vicinity of Cairo and act as a Reserve, should Egypt’s small indigenous Army, the Indian Divisions, and the various other units that were dug in along the Suez Canal need help against Turkish attacks from the East. When Britain declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 5 November 1914, no Turkish troops were anywhere near the Canal, but during December they began to amass c.120 miles to the east in the area near Beersheba. Their subsequent advance westwards across the Sinai Desert began in early January 1915 and their initial attempt to take the Suez Canal took place on 26 January 1915, with other unsuccessful attacks taking place on 2–5 February, 22 March, 30 May and in late June 1915. But by late April 1915, the 2nd Mounted Division (TF) had arrived in Egypt, enabling some elements of the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade – which had not been involved in the initial invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula on 25 April 1915 – to embark at Alexandria on 4 May 1915 and land on the following day on ‘W’ Beach, at the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula just west of Cape Helles. Once ashore here, they joined up with the 87th and 88th Brigades (which had already seen much fighting on the Peninsula) and the 29th Indian Brigade (which had also been there since April) in order to reinforce the battered 29th Division during the imminent Second Battle of Krithia (6–9 May 1915).

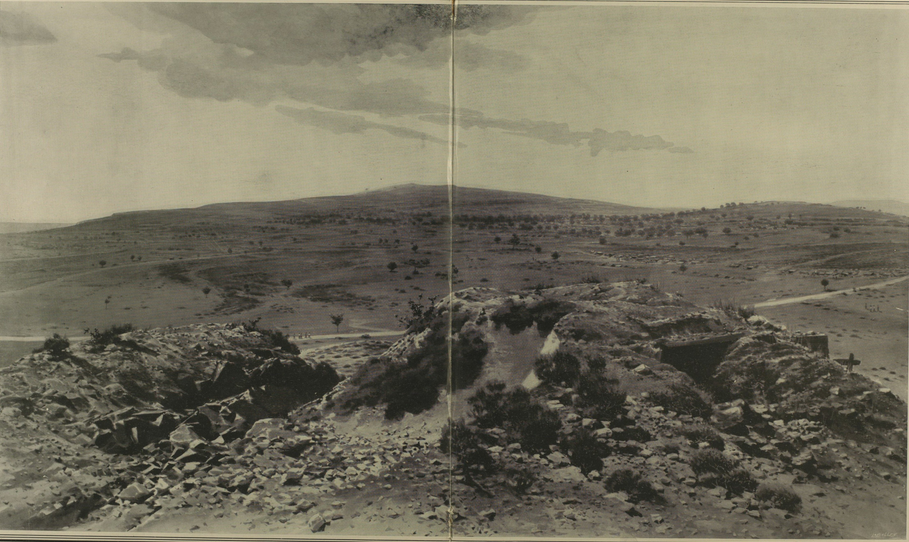

The War Diary of Williams’s 1/6th Battalion is not easy to read and contains very little detail – probably because of the difficult and stressful circumstances under which it was written. But various sources indicate that the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade led the left-hand prong of the three-prong assault on the well-protected and well-defended strategic village of Achi Baba, on a high point in the centre of the southern part of the Peninsula. This involved the Fusiliers advancing slowly along Gully Spur, where concealed machine-guns, especially on the smooth plateau overlooking ‘Y’ Beach, and heavy artillery fire caused them heavy casualties. So by 16.30 hours on 6 May 1915 the attacking troops were compelled to dig in for the night. On 7 May, the Brigade re-opened the attack on the left of the line, but was still prevented by shrapnel and the cleverly sited machine-gun batteries from advancing more than 20 yards, and at 15.00 hours they reported that “they were definitely held up by the accurate cross-fire of batteries of machine-guns concealed in the scrub on the ridge between the ravine and the sea”. Moreover, by this time the 1/7th Battalion – and probably the 1/6th Battalion, too – had had no food or water for two days. So rather than persist in a situation of stalemate, the entire Allied force was ordered to mount a general attack, starting at 16.45 hours. Despite the troops’ fatigue and their inability to take Achi Baba, the attack was partially successful – except on the left of the line, where the War Diary of the 1/7th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers recorded that it had lost 25 officers and 124 other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded and missing. So the battered Lancashire Brigade was replaced by the New Zealand Brigade and withdrawn, first to ‘W’ Beach and then to bivouacs in the centre of the southern end of the Peninsula just inland from Morto Bay.

The country leading up to Achi Baba

On 26 May 1915 the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade was re-designated as the 125th Brigade, 42nd (East Lancashire) Division, and from 3 to 23 June the 1/6th and 1/7th Battalions were back in the front line where, between 4 and 10 June 1915, they were involved in more attacks on Turkish positions that cost the 1/7th Battalion eight officers and 171 ORs killed, wounded and missing. Despite spells in the Support and Reserve lines, on 24 June 1915 the 1/6th and 1/7th Battalions were taken across to the Greek island of Lemnos, and thence to the Greek island of Imbros (the Turkish island of Gökçada since 1970), for three weeks’ rest. Here, at the end of June or beginning of July, the two Battalions received a draft of reinforcements before returning to Cape Helles on or about 14 July 1915. Here they landed on ‘V’ Beach where, according to his medal card, Williams finally arrived in person from England via the island of Lemnos on 22 July.

Between 6 and 9 August, together with Australian units, the two Battalions took part in heavy fighting near Gully Ravine, at Krithia Vineyard – i.e. during the Battle of Krithia Vineyard, which lasted from 6 to 13 August 1915. Quite apart from the obvious wish to gain ground and improve the local situation, the point of these engagements was diversionary. Sir Ian Hamilton, the Commander-in-Chief on Gallipoli, sought to delude the Turks into thinking that a major offensive was taking place in the southern sector of the Peninsula and so prevent Turkish Reserves from being sent northwards to Suvla Bay and ANZAC Cove, some 20 miles away, where fresh but inexperienced Allied troops had landed on 6/7 August and were attempting to break out into the mountainous hinterland that formed the central part of the Gallipoli Peninsula. But Otto Liman von Sanders (1855–1929), the German Commander of the Turkish forces on Gallipoli who had significantly improved their fighting efficiency over the preceding year, had seen through the Allies’ diversionary intentions, which he described as “a singularly brainless and suicidal type of warfare”, and so did nothing to weaken the Turkish position in the north of the Peninsula.

British troops somewhere near Krithia Vineyard (c.August 1915)

The Vineyard, which lay to the west of the road that linked the strategically important village of Krithia in the centre of the southern part of the Peninsula with the southern coast, was taken from the Turks by a rush attack on a front of about 1,200 yards on Saturday 7 August. Whereupon the Turks, who had, as it turned out, been about to launch their own offensive, riposted with two particularly ferocious counter-attacks on 8 August, one at 04.40 hours and one at 20.30 hours, plus continuous grenade attacks throughout the following night, but failed at first to regain the Vineyard, “which was held unyieldingly in spite of all efforts of the enemy to reconquer it”. As a result, the two British Divisions that were involved in the evenly balanced action during its first three days lost heavily. On 6 August 1915 the 29th Division lost 54 officers and 1,851 ORs killed, wounded and missing, and on 6 and 7 August the 42nd Division lost 80 officers and 1,484 ORs. So if we include the losses that were caused in August by the diseases that were endemic on the Gallipoli Peninsula, then Williams’s 1/6th Battalion, which had numbered 20 officers and 567 ORs on 3 August 1915, sank to nine officers and 336 ORs by 30 August. Moreover, the attempts to break out in the north of the Peninsula proved to be failures and the British attack on Scimitar Hill on 21 August 1915 turned out to be the first day of the last major British offensive of the Gallipoli campaign.

On 24 August 1915 the 1/6th Battalion went into Reserve, with Williams now in ‘D’ Company, but by the beginning of September it was back in the firing line, this time between the sea and the eastern end of Fusiliers Bluff. On 13 September Williams was formally “taken onto the strength of the 1/6th Battalion” and assigned to the Battalion’s Mortar Group, and on 18 September the Battalion was relieved by the 1/10th Battalion (TF) of the Manchester Regiment and moved to bivouacs on Gully Beach, on the western side of the southern end of the Peninsula. But in contrast with the spring and summer, the overall military situation was fairly static throughout the last week of September and all of October, and although Williams’s Battalion was in and out of the trenches near Gully Ravine, where it continued to take casualties, it did not participate in a major action. On 1 October 1915 the 1/6th and 1/7th Battalions became part of Corps Reserve in Gully Ravine, where, on 7 October, they were reinforced by ten new officers, and on 18 October they took over the right of Gully Ravine. But by the end of October, casualties and sickness had damaged the 1/6th Battalion to such an extent that it was temporarily amalgamated with the 1/7th Battalion, which was itself down to 24 officers and 359 ORs by 31 October 1915 and 21 Officers and 329 ORs by 30 November 1915.

In October 1915, however, Williams applied for a Regular Commission in the Royal Field Artillery with the support of his Commanding Officer, who considered him “a capable and energetic officer who has shown much keenness in [the] performance of his duties” and had “sufficient confidence and the necessary qualification to make an efficient horseman after due instruction”. But as there were no vacancies, he was compelled to remain with the 1/6th Battalion, in whose War Diary there are no entries between 7 and 20 November 1915 because its officers and 75 of its ORs had been taken across to the Greek island of Lemnos for some well-earned rest.

On 2 November the surviving members of the amalgamated Battalion moved inland to the Support and Reserve trenches on Geoghegan’s Bluff, a flattish area above Gully Ravine which was then the front line and where a Turkish attack was repulsed on 22 November, and finally, on 26 November, into the Eski Hissarlik Line. The Battalion worked the same rota in December, but on 12 December, without any explanation, the Battalion War Diary noted “Lt W.H. Williams taken off the strength”, and on 13 December, also without any explanation, “Lt W.H. Williams taken on the strength” – it was probably a question of short-term illness. On 19 December the Battalion was ordered to attack the Turkish lines as part of the diversionary tactics that would permit the imminent evacuation of the entire Allied Force from the Gallipoli Peninsula. The Turks responded with a counter-attack but were repelled, and on 24 December the Battalion went into Reserve at Gully Ravine, where it spent Christmas in dug-outs whose roofs were made of corrugated iron. On 27 December the Battalion moved to ‘W’ Beach, from where Fleet Messenger HMS Ermine (1912; sunk by a mine on 2 August 1917 off the village of Stavros in the Northern Aegean between Saros and Lemnos with the loss of 24 lives) transported it later on the same day to Lemnos.

HMS Ermine (1912–17) in Mudros Harbour (1917)

(Courtesy Caledonian Maritime Research Trust)

Williams was the only original officer in his Company who came through the campaign intact, but even he suffered from a poisoned arm and was incapacitated for a few months – the Battalion War Diary does not say when. It does however record that he rejoined his Battalion from VIII Corps on 29/30 December 1915, when it was still at Mudros, where he was attached to ‘B’ Company. On 30 December, the day of his departure for Egypt, he was also appointed Quartermaster, promoted Temporary Captain and given command of ‘D’ Company. From 1 to 11 January 1916, while it was still on Mudros, the 1/6th Battalion, which at 16 officers and 386 ORs was now down to about one-third of its proper strength, underwent training, mainly in the art of route-marching, of which they would have done none since leaving Egypt for the Dardanelles. Then, on 13 January 1916, Williams’s Battalion embarked at Mudros for Alexandria, where it arrived on 16 January. After acclimatizing for a week at a nearby training camp, it entrained for Tel-el-Kebir, a training camp that was mainly for Australian troops and situated on the edge of the desert c.131 miles to the south and 52 miles north-east of Cairo, and arrived there on 26 January 1916.

The training camp at Tel-el-Kebir

(Courtesy Australian War Memorial, CO4757)

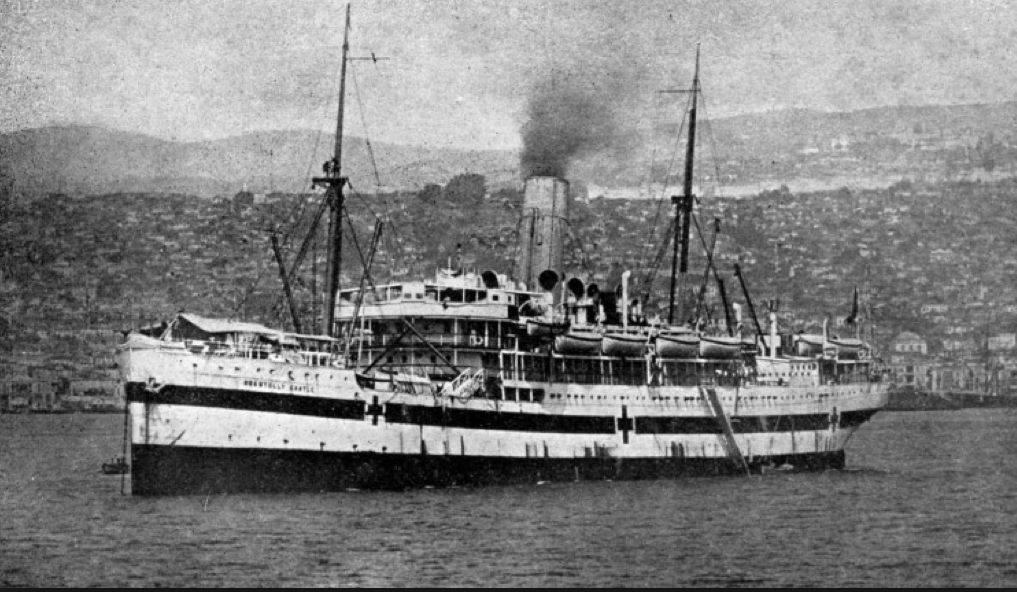

After resting at Tel-el-Kebir until 29 January, the 1/6th Battalion was taken by train to El Shallufa, a crossroads town at the southern end of the Great Bitter Lake and one of the defensive bases guarding the Suez Canal. It stayed here until 1 March, doing very little except building and maintaining emplacements. But on 2 March 1916 Williams, a Second Lieutenant once more, was transferred back to ‘B’ Company and on 14 March he, together with one other officer and 35 ORs from the 1/6th Battalion, was attached to the newly formed 125th Machine-Gun Company – though his name does not occur in the unit’s War Diary for the period in question. On 17 May 1916 he began an extended period of hospitalization at the Red Cross Hospital at Gaza; on 29 June HMHS Glencoates (no information available) ferried him from Alexandria to Cyprus where, on 5 July, he began a spell in the Army’s convalescent camp on Mount Troodos – reckoned to be the “coolest place in the Mediterranean” because it was several thousand feet above sea level and surrounded by pine forests – suffering from muscular rheumatism. On 30 July he was returned to Alexandria aboard HMHS Grantully Castle (1910; scrapped 1939) but was then sent westwards along the coast to No. 19 General Hospital at Ras el Tin because he was still suffering from neuritis (inflammation of one or more nerve ends); and he was finally returned to duty with the 1/6th Battalion from No. 17 General Hospital, situated in Victoria College, Alexandria, on 8 September 1916 – he was later promoted Lieutenant retrospectively with effect from the previous day.

HMHS Grantully Castle (1910–39; date and location unknown)

No. 21 General Hospital at Ras-el-Tin, Egypt

Between 17 May and 8 September 1916, Williams’s 1/6th Battalion had an uneventful, not to say boring, time – at least for the first three months. On 2 May, all training was suspended between 10.00 and 16.00 hours because of the fierce summer heat, and on 25 May the entire Battalion was moved to the Suez Quarantine Station at Port Tewfik, at the southern end of the Suez Canal where it flows into the Gulf of Suez. We do not know why, but the move may have some connection to the reason for Williams’s hospitalization. By 29 May the men’s work had been reduced to five hours a day because of the heat – between 05.00 and 09.00 hours and 18.30 to 19.30 hours – during which period they were, however, involved in building a quarantine perimeter around their camp. On 19 June the Battalion transferred from its quarantine camp at Port Tewfik to the town of Suez itself, a couple of miles to the east, and on 22 June the Battalion was moved 45 miles northwards to El Ballah, another town on the Suez Canal that was situated around eight miles east of Ismailia, where the troops occupied themselves with building defences until 29 July, when they route-marched a further 19 miles northwards to Kantara (Al Qantjarah), also on the Canal. Then on 30 July the Battalion moved to Hill 70, 12 miles from and overlooking the road to Romani (Bi’r ar Rummanah), the site of ancient Pelusium, and about three-and-a-half miles from the Bay of Pelusium (Tineh, Tina) on the northern Sinai coast. The Turks’ first attack on the Suez Canal had taken place on 26 January 1915 and Romani, 24 miles to the east of the Canal, was to be the Schwerpunkt of their third and final assault – this time by an Ottoman/German Army numbering some 16,000 men and commanded by General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein (1870–1948). But the Allies were well-prepared for the attack, knowing that it would have to come along the coastal road to Kantara.

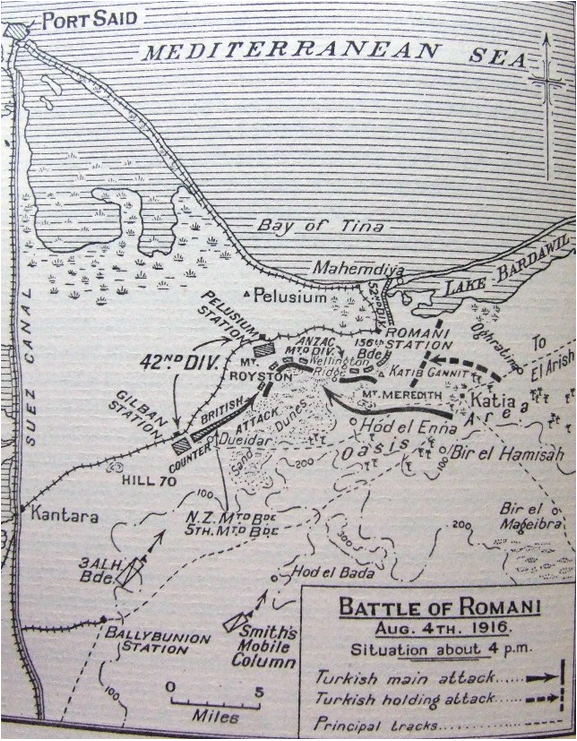

Battle of Romani (3–5 August 1916)

(Map from The Palestine Campaigns by Lieut-Gen. Sir Archibald Wavell; London: Constable & Co, 1928)

Opinions vary about von Kressenstein’s ultimate intentions when making this attack: did he want to capture significant sections of the northern parts of the Canal, or did he simply want to capture Romani and establish a well-fortified position between it and Kantara from which heavy artillery could bombard slow-moving shipping on the Canal, thereby seriously hampering Allied supplies? Whatever the answer, when von Kressenstein’s Army attacked during the night of 3/4 August 1916, it was met with spirited resistance by the 53rd (Lowland) Infantry Division, who were well dug in to the south and east of Romani, and the Allied cavalry, especially elements of the Mounted Division of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), who played a central role in the fighting. So before it was necessary for the Allied units that were positioned on and around Hill 70 to outflank the enemy, it had been brought to a standstill and driven back in a pitched battle that took place between 3 and 5 August 1916.

Unfortunately, we do not know how the 1/6th Battalion reacted to the news of the attack since their War Diary entries between 1 and 7 August are all but illegible. Other sources suggest, however, that on 4 August 1916 the entire 42nd Division, including the 1/6th Battalion, was ordered to assemble at the recently completed Pelusium station. They also suggest that, once the cavalry had done its work on 4 August and it was clear by 05.30 hours on the morning of 5 August that the enemy were in full but orderly retreat, the 42nd Division was part of a force of 50,000 men in the Romani area that was ready to pursue them at 06.30 hours. We also know that Williams’s 125th Brigade arrived at Hod el Enna, four miles south of Romani, at c.11.15 hours on 5 August. The general pursuit soon turned into an advance. By 12 August, notwithstanding the intense heat and shortage of water, which, as usual, caused many casualties in both armies, it was obvious that the victorious Allies had begun an advance whose purpose was the recapture of the Sinai Desert and the invasion of Palestine. The campaign had been a costly one, with the Allies losing c.1,200 men killed, wounded and missing and the Central Powers 9,000 men killed, wounded and missing plus 4,000 prisoners, i.e. just over 20 per cent of its strength.

From 15 to 19 August the 1/6th Battalion took part in a Brigade operation whose purpose the War Diary does not made clear, and by the end of the month, when the weather was cooling down, it started to practise route marching by night, probably in the vicinity of Romani, which by now appears to be its base. And, on 8 September 1916, when Williams reported for duty with the 1/6th Battalion there, it was practising “Brigade in attack”. From 10 to 15 September the Battalion rested for five days at Mohamedieh on the northern coast of Egypt between Port Said and Alexandria; it then returned to Romani until 20 September, from where it moved by train to Dueidar, a small oasis about ten miles south-west of Romani and near Hill 70, where, for several weeks, the men helped to create better defences. On 24 October 1916 the Battalion War Diary noted that Second Lieutenant Williams “has five weeks leave to England”, but although this was later extended to six weeks, he did not leave the Battalion until 24 November and was back in Alexandria by c.5 December – which makes it unlikely that he got further than Marseilles and probable that he had either been sent back to Egypt or returned of his own free will because his request to be transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had been granted while he was en route. We do not know why he had asked for such a transfer, but perhaps he had heard about its successes during the previous summer when the Allies were advancing eastwards against the Turks, or perhaps, like many young officers, he had become bored by tedious manual labour in an uncomfortable and inhospitable desert environment.

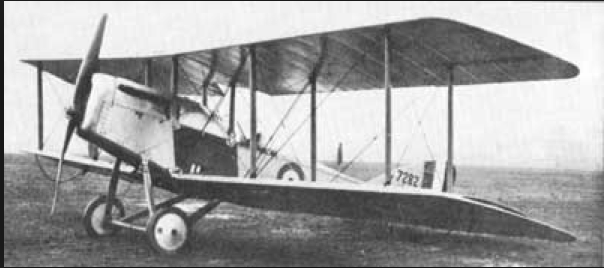

Whatever the truth of the matter, on 7 December 1916 Williams was sent to the RFC base at Ismailia (now Matar El Galaa), c.112 miles to the south-east. And on 10 December 1916 he was attached to No. 3 School of Military Aeronautics at Aboukir (Abu Qir), on the northern coast of Egypt and c.14 miles north-west of Alexandria, where he learnt to fly and got his “wings” within three months, probably on a Maurice Farman Shorthorn trainer. During this period of training, from 24 December 1916 to 11 January 1917, Williams was attached to No. 59 (Reserve) Squadron at Moascar, just to the west of Ismailia, and on 19 January 1917 he was attached to No. 23 (Reserve) Squadron back at Aboukir. On 5 March 1917 he was graded as Flying Officer and posted to 20 (Reserve) Wing at Aboukir as an Instructor where, on 18 April 1917, he was appointed Acting Flight Commander (Acting Captain) with pay. But from 25 May 1917 to 2 June 1917 he was hospitalized once again – this time in Suez with some kind of fever. Despite the illness, he was gazetted Captain with effect from 1 June 1917 on 7 August 1917 (London Gazette, no. 30,223, 7 August 1917, p. 8,116) and on 24 June 1917 he was appointed Flight Commander. At some point during his time at Aboukir he conducted Prince Arthur, the Duke of Connaught (1850–1942), the third son of Queen Victoria, and General Jan Smuts (1870–1950), the South African statesman, military leader and philosopher, on a visit round the airfield. As a member of the British War Cabinet (1917–19), Smuts played a major role in setting up the Royal Air Force.

A Maurice Farman Shorthorn, RFC Aboukir, Egypt (1917); the Shorthorn can be distinguished from the Maurice Farman Longhorn by the length of the elevator that was, unusually for the time, on the front of the aircraft

RAF Aboukir, Egypt (date unknown, but probably well after World War One since the wooden hangars next to the main runway in the 1917 photo have been replaced by larger, more modern ones)

Officers of the 40th (Army) Wing seated in an olive grove at Ramleh, Palestine; the officer sitting on the far left may well be Williams, given the resemblance to him as he appears in the photograph that was taken outside St George’s Hall (see above)

On 2 February 1918, No. 142 Squadron, RFC, was formed at Ismailia as an Army Co-operation Squadron and equipped with a mixture of light bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. It then became part of the 40th (Army) Wing, which had been set up on 5 October 1917 at Ramleh (also Ramla and Ramallah), an important crossroads and rail/road interchange in Palestine about nine miles south-west of Tel Aviv, during Allenby’s preparations for the final advance on Jerusalem. It consisted of No. 1 Squadron (Australian Flying Corps) (No. 67 (Australian) Squadron (RFC) from 16 March 1916 and February 1918) and Nos 111, 144 and 145 Squadrons (RFC). The advance ended on 11 December 1917, when General Allenby (1861–1936; later 1st Viscount Allenby), displaying a fine political sensibility, entered the Holy City on foot via the Basrah Gate to accept its formal surrender from the Mayor and other civic dignitaries.

General Allenby’s Entry into Jerusalem on 11 December 1917; Colonel T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”) is just visible behind his left shoulder

Given its allotted task in the field, No. 142 Squadron’s aircraft included not only the long-distance B(lériot) E(xperimental) 12(a) and 12(b) and the R(econnaissance) E(xperimental) 8, but also the lesser-known single-seat Martinsyde Elephant, of which a total of 271 were built and of which there were two versions – the G.100 (Scout) and the later, modified, G.102 (Light Bomber and Reconnaissance). When No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps (AFC), had arrived in the Middle Eastern theatre of war on 14 April 1916, it had been equipped, inter alia, with 17 Martinsydes, which it used on operations between June 1916 and 12 April 1918, when Williams fetched the last one (A3955) on behalf of 142 Squadron. Five of the 17 had been written off in combat or accidents by the time that Williams took delivery of A3955, but starting in October 1917, when five brand-new Bristol Fighter F.2Bs were delivered, all No. 1 Squadron’s Martynsides were gradually phased out and replaced, for ease of maintenance, by the greatly superior, two-seat Bristol Fighter F.2B, of which 4,469 had been built by the time that production ceased in December 1926.

The Martinsyde G.100 Elephant

The Martinsyde G.102 Elephant

Known colloquially as the “Biff” or “Brisfit”, the first two prototypes of the Bristol Fighter F.2B had first flown on 9 September and 25 October 1916 respectively, and from 18 July 1917 the final service model of the F.2B was increasingly issued to the RFC’s fighter-reconnaissance Squadrons as a replacement for the B.E.2(c) and the F.2B’s flawed predecessor, the Bristol Fighter F.2A. Because both versions of the Martinsyde had large wing areas and greater than average lifting power, they could stay aloft for around five-and-a-half hours, two-and-a-half hours longer than the F.2B. But like the B.E.12(a) and (b), they lacked the speed, manoeuvrability, all-round visibility and armaments of their most successful German opponents such as the Fokker DIII and so were considered more appropriate for the conditions that prevailed in the Middle East. In contrast, the F.2B, which was powered by the Rolls-Royce Falcon III engine (275 h.p.), was much more manoeuvrable than the Martynside, could climb to 10,000 feet in just over 11 minutes, had a service ceiling of 20,000 feet, and a top speed of 125 mph, making it more evenly matched with the latest Fokkers.

But early in April 1918, No. 142 Squadron changed its role and transferred to No. 5 Wing as an Artillery Spotting and Reconnaissance Squadron. Williams, who was one of four officers to be transferred from the Training Brigade in Egypt to the more operational Palestine Brigade on 1 April 1918, finally reported for duty with No. 142 Squadron on 3 April 1918, when it was at Julis, 16 miles north-east of Gaza. On 18 April the Squadron moved northwards to Ramleh, where its strength was two B.E.12(a)s, four Martinsydes, and two R.E.8s, and it was from this airfield that it took an active part in operations against the Turks until the Armistice of 31 October 1918, playing a particularly significant role in the Battle of Megiddo (19–25 September 1918), the last Allied offensive in the war against the Turks.

Williams began flying duty with No. 142 Squadron on 4 April 1918, when he did a test flight from 14.50 hours to 16.25 hours (1 hr 35 mins) in one of the Martynsides, and here is a summary of his subsequent sorties during his very brief time with the unit:

5 April 1918: Williams and four other pilots (plus one Observer in the R.E.8) went on a bombing raid from 09.25 hours to 12.05 hours (2 hrs 40 mins) in one Martynside, two B.E.12(a)s, and one R.E.8. in support of Allenby’s first raid east of the River Jordan on the railway facilities at Amman (see T.H. Helme). Williams, flying the Martynside, dropped two 112-pound bombs from 6,200 feet on the railway station at Amman, Jordan, one of which hit the target.

Hejaz Railway – Amman (Amon, ancient Philadelphia) station

(Courtesy Imperial War Museum, photograph Q 59648)

6 April 1918: Williams made a test flight in a B.E.12(a) from 09.40 hours to 09.45 hours (5 mins).

7 April 1918: Williams made two test flights in a B.E.12(a) from 08.55 hours to 09.00 hours and from 17.05 hours to 17.20 hours (a total of 20 mins).

8 April 1918: Williams made two test flights in a B.E.12(a): from 09.55 hours to 10.15 hours and from 15.00 hours to 15.15 hours (a total of 35 mins).

11 April 1918: Williams made a test flight in a Martynside from 09.30 hours to 09.45 hours (15 mins).

12 April 1918: Williams fetched the last Martynside from No. 1 Squadron (AFC), which was stationed then on the aerodrome at El Mejdel (Mejdel Yābā; Aphek), c.35 miles away. The flight, which took place between 18.20 and 18.45 hours, lasted 25 mins.

13 April 1918: Williams made three practice bombing flights in the Squadron’s new Martynside: one from 05.55 hours to 06.30 hours, one from 06.40 hours to 07.05 hours, and one from 16.20 hours to 16.30 hours (a total of 1 hour and 10 mins).

14 April 1918: Williams (plus Observer) made a test flight in an R.E.8 from 06.30 hours to 07.00 hours (30 mins).

16 April 1918: Williams (plus Observer) practised formation flying in an R.E.8 from 07.15 hours to 07.40 hours (25 mins).

18 April 1918: Williams made a test flight in a Martynside from 17.10 hours to 17.30 hours (20 mins).

19 April 1918: Williams made two test flights in a Martynside from 06.05 hours to 06.30 hours and from 15.50 hours to 16.10 hours; he then flew a Martinsyde from El Mejdel to Ramleh from 17.10 hours to 17.30 hours (a total of 1 hour and 5 mins).

23 April 1918: Williams made a test flight in a Martynside from 06.40 hours to 07.00 hours (20 mins).

24 April 1918: Williams (plus Observer) flew an R.E.8 from Ramleh to El Mejdel – probably Mejdel Yābā – and back from 06.35 hours to 07.00 hours and from 07.55 to 08.15 hours (a total of 45 mins). Mejdel Yābā is east of Joppa and was the base of No. 1 Squadron (AFC), which exchanged its Martynsides for Bristol Fighters in Autumn 1917 (see photo below).

Bristol Fighters at Mejdel Yābā aerodrome, Palestine, the base of No. 1 Squadron (AFC) in 1917/18

26 April 1918: Williams (plus Observer) made a test flight in a B.E.12(a) from 06.45 hours to 07.25 hours. He then flew three more sorties in the same machine on the same day: one in order to practise formation flying from 16.15 hours to 16.40 hours; and a return flight to Junction Station (a strategic railway junction where the line east to Jerusalem branches off eastwards from the main line southwards to Gaza and Beersheba), from 17.00 hours to 17.10 hours and from 18.00 hours to 18.15 hours (a total of 1 hr 30 mins).

29 April 1918: Williams flew a B.E.12(a) for an engine test from 08.30 hours to 09.10 hours (40 mins).

1 May 1918: Williams flew one of the three B.E.12(a)s to go on a long-distance bombing raid from 15.50 hours to 18.00 hours (2 hrs 10 mins) – probably in support of General Allenby’s unsuccessful second raid east of the River Jordan on the mountain village of Es Salt (see Helme). During the sortie, Williams dropped three 20-pound bombs from a height of 4,000 feet on a group of Turkish cavalry.

3 May 1918: Williams piloted one of the two Martinsydes during a long- distance bombing raid from 16.15 hours to 18.10 hours (1 hr 55 mins) carrying twelve 20-pound bombs – probably in support of the same raid as two days previously. He was killed, aged 26, just six days before the announcement of his engagement to Edith Ormerod (see above) in Flight magazine, in an accident which is described as follows in The Short History of No. 142 Squadron:

It was on his return from a bomb raid in a Martinsyde scout on 3rd May that Captain Williams […] met with a fatal accident. Landing at Ramleh in the failing light of the late afternoon, his undercarriage caught a tree on the aerodrome[,] turning the machine upside down. On hitting the ground it caught fire, and some [of its load of] bombs, which for a reason which was never discovered, had not dropped, exploded[,] blowing [the] Pilot and machine to pieces.

And on 4 May 1918, after Williams’s remains had been buried in Ramleh Military Cemetery (Grave CC.58, with the inscription “Preswylfa, Carnarvon, North Wales”), his Commanding Officer wrote the following letter to Williams’s parents and copied it to his fiancée:

He had been out on duty over enemy country, in company with several other machines. After doing their job of work they all returned to our Aerodrome together, and your son[,] flying in very low, collided with a solitary tree, which was the cause of his death. There is no doubt that he was killed absolutely instantaneously, and can have suffered no pain whatever.

Williams is commemorated on the Magdalen College School War Memorial and on the Caernarfon Cenotaph, Castle Square. He left £200 0s. 7d. to his widowed mother.

Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel; Grave CC.58

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; photo © The War Graves Photographic Project)

The Caernarfon Cenotaph (Cofeb rhyfel), Castle Square (unveiled in 1922); the original Cenotaph was without the Welsh Dragon and had a French 75 mm field gun standing at one of its corners

On Christmas Eve 1920, C.C.J. Webb wrote a letter to President Warren in which he continued a discussion that had begun earlier:

I return to W.H. Williams’s letters. It is clear he should not be on the tablets [i.e. the College War Memorial]! Carter thinks, however, that the “W.H. Williams” there is a chorister: but no such chorister appears in the Callendar [sic] since [18]89 at any rate. There was a W. W. Williams whom I remember, who was in the choir in 1905 and was one of the first lot we used to have here after I arrived [at Holywell Ford, where he and his wife lived after their marriage in 1905]. I don’t know whether he (I see his odd second name was Wmffre – however you may pronounce that!) was killed in the War. If so the initials are wrong. Or perhaps there was a W.H. Williams in the casualty lists, who was mistakenly supposed to be our exhibitioner.

Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; photo © The War Graves Photographic Project)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would particularly like to express their grateful thanks to T. Meirion Hughes at Caernarfon Ddoe / Caernarfon’s Yesterdays, for the photograph of the Caernarvon Choir at Birmingham, also to Ken Morris of Caernarvon Traders for the obituary and newspaper photograph.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Tribute of Respect to Mr John Williams, of Bodafan’, The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser, no. 1,696 (8 October 1859), p. 12.

[Wanderer], ‘Sea Side Sketches’, ibid., no. 1,914 (11 June 1864), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Mr. John Williams, of Bodafon, Llandudno’, ibid., no. 2,570 (10 June 1876), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Funeral of Mr. John Williams, Bodafon, Llandudno’, ibid., no. 2,571 (17 June 1876, p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Llandudno: Death of Mr Robert Williams, of the Royal Hotel’, Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald and North and South Wales Independent, no. 3,025 (27 February 1891), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘The Royal Visit to North Wales’, The Times, no. 35,813 (26 April 1899), p. 14.

[Anon.], ‘The Queen will arrive at Windsor ….’, The Times, no 35,979 (6 November 1899), p. 9.

[Our Special Correspondent], ‘The German Emperor at Windsor’, The Times, no. 35,996 (25 November 1899), p. 12.

[Our Special Correspondent], ‘Carnarvon Operatic Society: Performance of “Trial by Jury” and “H.M.S. Pinafore”’, The North Wales Express, no. 1,421 (8 May 1908), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The Successful Conductor: Record of Mr John Williams’, Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, no. 2,890 (18 June 1909), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘At 11, Downing St: Humorous speech by Mr. Lloyd George’, ibid.

[Anon.], ‘Carnarvon Choir’s Success: Fine Victory over South Wales: The Adjudication’, ibid.

[Anon.], ‘Press Opinions’, ibid.

[Anon.]. ‘Rousing Reception: Mr. John Williams at Colwyn Bay’, ibid.

[Anon.], ‘Why Carnarvon Won: Mr John Williams’ Praise of the Choir’, ibid.

[Anon.], ‘National Eisteddfod in London’ (with portrait photo), The Musical Herald (London), no. 736 (1 July 1909), pp. 199–202.

[Anon.], ‘The National Eisteddfod: Royal Albert Hall, London (June 15 to 18)’, The Competition Festival Record, Extra Supplement to The Musical Times, no. 12 (1 July 1909), [pp. 33–5].

[Anon.], ‘The King’s Speech’, The Times, no. 35,996 (14 July 1911), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Defence of the Welsh Church: The Hyde Park Demonstration’, The Times, no. 40,233 (9 June 1913), p. 10.

[Anon.], ‘Defence of the Church in Wales: Today’s Demonstration in Hyde Park’, The Times, no. 40,244 (21 June 1913), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Welsh Church: Protest Meeting in Hyde Park’, The Times, no. 40,245 (23 June 1913), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Musical Festival at Carnarvon’, Llangollen Advertiser (Denbighshire, Merionethshire and North Wales Journal), no. 2,789 (19 June 1914), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Testimonial to a Welsh Musician: Mr John Williams’s Career’, ibid., no. 2,829 (18 May 1915), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Famous Choir Leader’ [obituary], The Cambrian Daily Leader, no. 13,937 (26 January 1917), p. 1.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Death of a Famous Welsh Choir Conductor’, The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality, no. 6,274 (30 November 1917), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Mr John Williams, Carnarvon: Impressive Funeral’, ibid., no. 6,275 (7 December 1917), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Mr. John Williams, Conductor of Carnarvon Choral Society’ (with photo) The Musical Herald (London), no. 838 (1 January 1918), pp. 7–8

[Anon.], ‘To be married’, Flight, 10, no. 19 (no. 489) (9 May 1918), p. 521.

[Anon.], ‘Death of a Carnarvon Officer’, Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, [no issue no.], (17 May 1918), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Roll of Honour: Captain W.H. Williams, The Lily, 11, no. 17 (June 1918), pp. 218 and 219.

Peter Lewis, The British Fighter since 1912: Fifty Years of Design and Development, New edition (London: Putnam, 1967), pp. 65 and 87.

Owen Thetford, ‘Bristol Fighter’, in: Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918, 5th edition (London: Putnam, 1971), pp. 125–6.

Westlake (1996), pp. 56–8.

Chambers (2003), pp. 29–32.

Callwell (2005), pp. 192–7.

Ford (2010), pp. 299–308.

Sir Ian Hamilton’s Despatches from the Dardanelles, etc. (Uckfield, East Sussex: The Naval & Military Press, 2010), pp. 44–57.

Bebbington (2014), pp. 323–6.

Gariepy (2014), pp. 224–47.

Archival sources:

AIR 1/2028/204/326/3.

AIR 1/2029/204/326/5.

AIR 1/2031/204/326/11.

AIR 1/2031/204/326/12.

AIR 1/2031/204/326/26.

AIR 1/2032/204/326/28.

WO95/4299 (6th Border Regiment).

WO95/4315 (1/6th Lancashire Fusiliers).

WO95/4315 (1/7th Lancashire Fusiliers).

WO95/4588 (6th Border Regiment).

WO95/4594 (1/6th Lancashire Fusiliers).

WO95/4594 (125th MG Coy).

WO374/823.

On-line sources:

Meirion Hughes and Keith Morris, ‘A Musical Family’ [article on the Williams family of Carnarvon], Caernarfon Ddoe / Caernarfon’s Yesterdays: http://www.carnarvontraders.com/musical.shtml (accessed 14 September 2018).

Robert David Griffith, ‘Williams, John (1856–1917)’, Dictionary of Welsh Biography: http://yba.llgc.org.uk/en/s1-WILL-JOH-1856.html?query=Williams,+John+&field=name (accessed 14 September 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Romani’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Romani (accessed 14 September 2018).

Wikipedia: ‘Force in Egypt’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Force_in_Egypt (accessed 14 September 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘2nd Mounted Division’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_Mounted_Division (accessed 14 September 2018).