Fact file:

Matriculated: 1911

Born: 3 July 1892

Died: 30 July 1915

Regiment: Rifle Brigade

Grave/Memorial: Ypres Menin Gate Memorial: Panels 46 to 48 and 50

Family background

b. 3 July 1892 as the fourth son (fifth of seven children) of George Strachan Pawle, DL, JP (1856–1936), and Clotilda Agatha Pawle (née Hanbury) (1858–1942) (m. 1880).

Parents and antecedents

The rise of the Pawle family from urban prosperity to a prominent place in the Hertfordshire gentry seems to have been made possible by the growth of increasingly lucrative jobs in the financial sector of the City of London during the eighteenth century. But it accelerated during the first half of the post-Napoleonic nineteenth century – the heyday of Pawle’s great-grandfather, Francis [I] Pawle (1795–1874), who in 1819 married Mary Sophia Dawes (1793–1839). Francis was born in Pentonville, part of the prosperous north London Borough of Islington, and at the time of his marriage was living at 18, Camden Street, Islington, a three-storey terrace house which, judging from the style, must have been recently built. By 1826 he was dealing in shares and according to the Census of 1841 he was still living in Islington as an established stockbroker. Ten years later, he had moved southwards, nearer the City, and was living at 12, Park Terrace, Highbury, an elegant row of terrace house that must have been built in c.1829. He probably retired when he was 60, i.e. in about 1855, and in 1871 he was living at 108, Birkheads Road, Reigate, Surrey, just round the corner from the railway station in a fashionable suburban town that had been steadily expanding since the arrival of the London–Brighton railway in 1841–42. At the time of his death, Francis Pawle was living at 2, St Mark’s Cottages, Reigate, a name that suggests they were close to the Anglo-Catholic Church of St Mark’s, Reigate, which had been built in the northern part of the town in 1860 to help cope with the population expansion.

In 1851, Frederick Charles Pawle (1827–1915), Francis [I] Pawle’s eldest son, was still living with his father at 12, Park Terrace, but by 1861, i.e. nine years after his marriage in Islington on 2 June 1852 to Helen Mary Strachan (1829–1924), he was living at 80, London Road, Reigate, just south of the railway station, with six servants, including a nurse and an under-nurse. By 1871 the family had moved a few hundred yards further south, to 32, London Road, presumably to accommodate their growing number of children, and had increased the number of their servants to around ten – including a nurse and a coachman. But by 1881 they had left the area around the station, moved to “Northcote”, 113, Gatton Road, on the north-eastern edge of Reigate, and reduced their staff of servants – which now included a butler and a footman, sure signs of growing prosperity – to seven once more. Between 1854 and 1872 they produced 12 children (ten sons and two daughters – see below). By 1891 their address was 118, Gatton Road – which may be the result of a renumbering rather than a move – and in 1911 they gave their address simply as “Northcote”, with the number of their servants remaining at seven. Their prosperity was clearly on the increase, and when they died, Frederick Charles and Helen Mary left £116,893 5s. 8d. and £11,009 5s. 8d. respectively.

Frederick Charles Pawle (1827–1915) and Helen Mary Pawle (1829–1924)

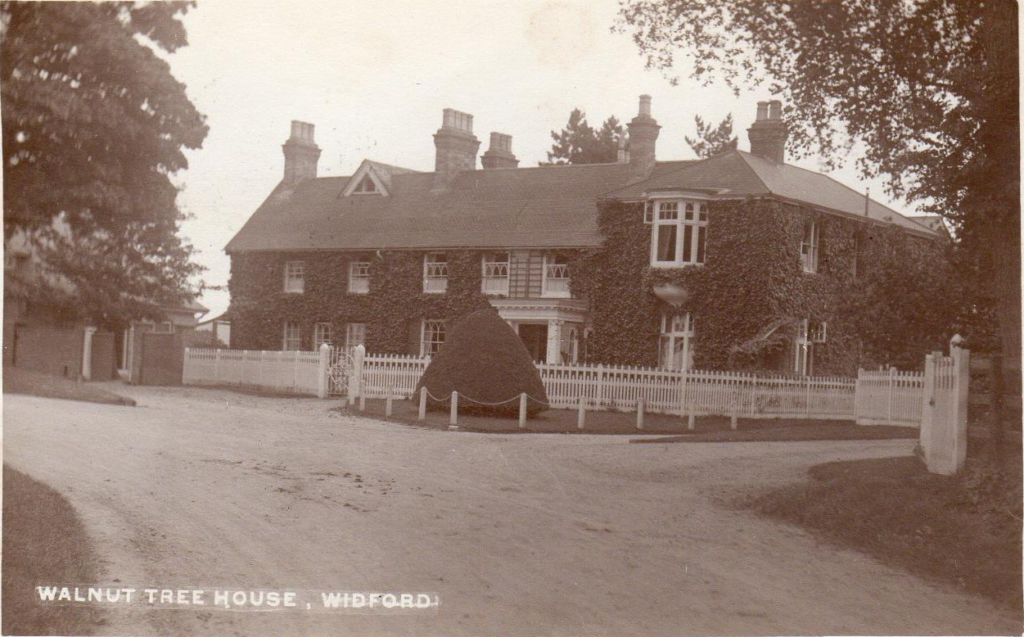

George Strachan Pawle, Bertram Pawle’s father, was Frederick Charles’s second son, and in 1881, a year after their marriage, he and his wife were living with his parents at 113, Gatton Road, Reigate. But at some juncture between then and 1891, George Strachan Pawle’s family moved away from Surrey to Walnut Tree House, 32, Ware Road, Widford, Ware, Hertfordshire (four servants, increasing to five in 1901), an even more rural location. They were still living there in 1912 and continued to do so until George Strachan died in 1936, having prospered in the City to the same degree as his father: he left £114,038 16s. 6d. and six years later his widow left £15,379.

Walnut Tree House, Widford, Ware, Hertfordshire

From 1877 until his retirement in 1926 George Strachan Pawle worked in the London Stock Exchange with Campion and Co. (1877–1900 and 1906–26) and Jourdan and Pawle (1900–06) as a stockbroker and dealer in foreign bonds “throughout the balmy days of the market that ended with the Great War”. Besides stock-broking, George Strachan had a variety of business interests. For a time he was interested in breweries in England and Australia, and he formed the successful Melbourne City Properties Trust, of which he remained Chairman until the day of his death. For many years he was also a Director and then the Chairman of the old-established lead and shot works of Walkers, Parker and Co. By 1912 he had become a JP. Politically a Liberal, he reduced the Conservative vote considerably when he stood as a candidate for Hertford in January 1910 and lost by 1,692 votes to Sir John Fowle Lancelot Rolleston (1848–1919). He was also an enthusiastic famer who “loved nothing better” than to show visitors round his 300 acres and well-stocked, well-ordered farmyards. His obituarist describes him as a “handsome man, with fine physique and unbounded energy”, and sport was as important to him as it would be to Bertram. He won the Veterans’ Cup for the Stock Exchange Walk to Brighton in 1903 (10 hours and 19 minutes); he was a keen follower of the Puckeridge Foxhounds and rode to hounds until he was 80; and he was an enthusiastic cricketer with a pitch in the grounds of his house.

On the outbreak of war, George probably joined one of the (unidentified) supernumerary Companies of the Rifle Brigade that were used to guard vulnerable points in England. But in late 1915 he was commissioned Lieutenant in the 24th (Home Counties) Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Rifle Brigade, which had been formed on 10 November 1915, making him the oldest subaltern in the British Army. In early 1916 the Battalion was sent to India, where it arrived at Agra, just below the Himalayas, on 25 February 1916. Little is known about the Battalion’s history as it kept no War Diary and was dispersed on 29 November 1919, but it served in various places in northern India, and was concerned mainly with matters of internal security. By the time George Strachan returned to Britain he had been promoted Captain, but his health had been badly affected by the Indian climate. After the war, he became interested in County Council matters and was an active member of Hertfordshire County Finance Committee and the Territorial Association. He became a Deputy Lieutenant and High Sheriff of Hertfordshire in 1923.

George Strachan’s eleven siblings were:

(1) Frederick Dale (1854–96); married (1877) Amy Louisa Cattley (1857–95); one daughter;

(2) Mary Isabella (1857–1948); later Richardson after her marriage in 1879 to Walter Brankstone Richardson (1851–84), one daughter; then Rundall after her marriage in 1889 to George William Rundall (1852–1926), one daughter;

(3) Lewis Shepheard (1859–1947); married (1885) Angelina Burgess Weatherall (1863–1930); one daughter, two sons, of whom one, Derek Weatherall (1887–1915), was killed in action in World War One (see below) and the other, Hugh Lewis (1889–1961), survived the war (see below);

(4) Arthur (died in infancy 1861);

(5) Helen Margaret (1862–1904), later Heasman after her marriage (1889) to William Gratwicke Heasman (1862–1934); two sons, one daughter;

(6) Ernest Dosseter (1864–1944); married (1892) Elizabeth (“Bessie”) Lyman Stevens (1866–1943); two sons, two daughters;

(7) Harold (1866–88);

(8) Leonard Philip (1868–71);

(9) Reginald [I] (1870–1958); married (1925) Myra Bateman (1878–1941); then (1941) Margaret Clarke (1883–1965);

(10) Clement Dawes (1872–1931); married (1904) Audrey Woodforde Hartcup (1883–1955); two sons, one daughter;

(11) Malcolm Gerald (1874–1917); died, aged 44, on 27 June 1917 while on active service in Lahore, serving as a Captain in the 2nd Garrison Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment (see below).

Lewis Shepheard Pawle started as a stock jobber and became a stockbroker. He lived at Hutchin’s Barn, Knotty Green, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, a sixteenth-century timbered house with a minstrels’ gallery that is valued now (2018) at over two and a half million pounds. Lewis Shepheard’s second son, Hugh Lewis (1889–1961), was educated at Harrow and began his professional life as a stockbroker. But like many young men who had undergone training as a cadet at a public school, he tried to enlist as a Private in the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (1st Public Schools Battalion) on 15 September 1914, four days after it was raised at Epsom, Surrey, as one of the four new Public Schools Battalions. On 29 March 1915 he applied for a Territorial Commission, giving his profession as “artist”, and on 7 June 1915 he was made a Second Lieutenant in the 2/1st Battalion, the Hertfordshire Regiment (promoted Lieutenant in the following year). On 1 September 1917 he was diagnosed with increasing deafness and transferred into the 2/5th Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Essex Regiment, which was stationed in England until it was disbanded in March 1918. Hugh Lewis’s deafness was worsened by exposure during the winter of 1916/17: he left the Army on 9 February 1919 and relinquished his commission on 30 September 1921 (London Gazette, no. 32,548, 13 December 1921, p. 10,216). But in the late 1920s he and his wife, Margaret Florence (née Walden; 1890–1981; m. 1926) became stained glass artists and for 30 years worked in the London studio of Archibald Keighley Nicholson (1871–1937), a member of the Arts and Crafts Movement, who had set up the studio in the late 1890s. In 1954 Hugh Lewis also became librarian and treasurer of the British Society of Master Glass Painters (founded in 1926).

William Gratwicke Heasman was trained as a doctor but was also a well-known county-class cricketer who played for Sussex and also, while living in the USA, for the Philadelphia cricket XI.

Ernest Dosseter Pawle was also a stock jobber and his oldest son, Reginald [II] Brooks Pawle (b. 1894, d. in the USA) attended Marlborough School as a boarder and enlisted in the 10th Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers, on the outbreak of war. But like so many of his family, he transferred to the Hertfordshire Regiment, and was gazetted Second Lieutenant there on 10 June 1915. He went to France on 25 June 1917. From 1 October 1920 to 4 May 1921 he was a Special Constable in the RIC (the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, known colloquially as “The Black and Tans”), a unit that had been formed in 1919 to assist the regular police during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21). It attracted many ex-servicemen who had no regular employment, and acquired an extremely bad reputation among the Irish for their violence and cruelty towards the civilian population. After a spell in the Gold Coast Police from 1921 to 1922, he emigrated to the USA, where he became a manufacturer.

Reginald [I] Pawle became a mining engineer and later lived at Rookwood, Doods Park Road, Reigate, quite near to the railway station and just to the east of his grandfather’s old residence, at 108, Birheads Road. He left £134,372 16s. 8d.

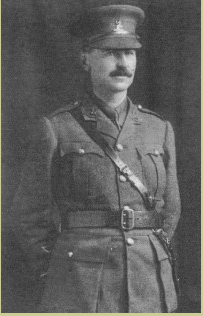

Captain Malcolm Gerald Pawle (1874–1917)

(Photo courtesy of John Hamblin, Esq.)

Malcolm Gerald Pawle, too, was educated at Marlborough College, where he spent two years in the College’s Officers’ Training Corps and proved himself so good a marksman that he was chosen to be a member of the Shooting VIII. In 1900 he became a member of the Stock Exchange, where he worked as a stockjobber, and having attested on 29 September 1914, he was accepted as a Private in the 19th (Service) Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers (the 2nd University and Public Schools Battalion), which had been raised at Epsom on 11 September 1914. But as he had already completed two years of basic training in a Junior Officers’ Training Corps and was 6 foot 3 inches tall, Malcolm Gerald was discharged to a commission in a Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment on 3 December 1914. Then, on 18 August 1915, he was made Commanding Officer of ‘D’ Company of the 1st Garrison Battalion of the Essex Regiment that had been formed as a Provisional Battalion at Denham, Buckinghamshire, on 21 July 1915 from drafts of men who were unfit for active service because of “age, infirmities or wounds”. On 25 August 1915 the Battalion, comprising 27 officers and 984 other ranks (ORs), sailed from Devonport on the RMS Empress of Britain (1905–30; scrapped) for Mudros, the major port on the Greek island of Lemnos, c.31 miles off the west coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula, where it arrived on 3 September 1915.

Malcolm Gerald’s medal card indicates that he disembarked at Lemnos on 6 September 1915 with the rank of Acting Captain. But according to the Battalion’s War Diary, the men suffered so badly from sickness, mainly dysentery and diarrhoea, that by mid-November three officers and 113 ORs had been shipped back to base or to Britain. On 23 October he was put in charge of a detachment consisting of a Warrant Officer, four Sergeants and 69 ORs, which he conducted to Cape Helles, at the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, before returning to Lemnos. Here, as from mid-November 1915, he was moved from ‘D’ Company to a mounted patrol whose main task was to prevent the sale of liquor in the camp areas and stop the illicit smuggling and sale of military clothing. On 26 December 1915 he was made Commanding Officer of ‘A’ Company and embarked at Mudros for the Greek island of Tenedos (now the Turkish island of Bozcaada) – c.30 miles due east of Lemnos and just off the coast of Asia Minor – as part of a detachment of seven officers and 350 ORs. He rejoined his unit at Mudros on 22 January 1916, i.e. after most Allied troops had been evacuated from Gallipoli to Egypt, because, as a second-line unit that was primarily concerned with logistics and communications, there was no need for the 1st Garrison Battalion to leave Lemnos until February 1916.

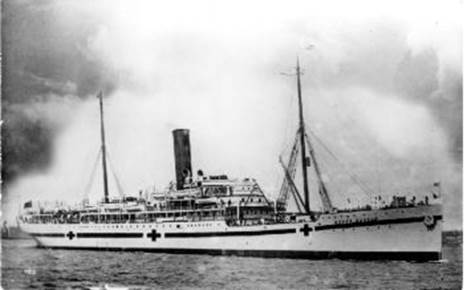

The Battalion was then taken to Egypt and stationed at Ismailia on the Suez Canal, but as Malcolm Gerald did not have a strong constitution, he could not cope with the Egyptian climate and was admitted to the Anglo-American Hospital in Cairo on 7 May 1916. On 15 May 1916 he was transferred to the Sirdarich Convalescent Home, also in Cairo, and on 2 June 1916 he was sent back to England on the hospital ship HMHS Dover Castle (1904–17; torpedoed off Bône, Algeria, on 26 May 1917 by the UB-67 while en route from Malta to Gibraltar with the loss of seven lives).

HMHS Dover Castle (1904–17)

On his arrival in England, Malcolm Gerald went before a Medical Board at Caxton Hall, London, where he was diagnosed as suffering from “D.A.H.” (Disturbed Action of the Heart) and weight loss following a febrile attack that may have been caused by paratyphoid when “on Field Service” on Lemnos during the previous autumn. On 21 August and 25 September 1916 he went before a second Medical Board that convened on both occasions at the War Hospital, Croydon, Surrey, suffering from nausea after food and dyspepsia. As a result, he was given a month’s sick leave, after which another Medical Board on 31 October 1916 declared him fit for General Service. After a fifth and final Medical Board had confirmed this diagnosis on 4 November 1916, he was attached to the 1st (Reserve) Garrison Battalion of the Royal Suffolk Regiment that had been formed at Gravesend on 14 March 1916 and would stay in the area of Gravesend, Tilbury and the Isle of Grain for the rest of the war.

But Malcolm Gerald volunteered once again for foreign service, and this time he was attached not to the 1st Garrison Battalion of the Essex Regiment, but to the 2nd Garrison Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment – which had been formed in Bedford in December 1916 and would land in India in February 1917, where it remained until January 1920 as part of Karachi Brigade in the 4th Quetta Division of the Indian Army. Once in India, Malcolm Gerald was stationed in the city of Hyderabad, in the Sindh District of modern-day Pakistan, where, unfortunately, the excessive heat proved too much for him, and he died of septic pneumonia in the Station Hospital at Lahore on 27 June 1917. Although his name is on the Karachi War Memorial, he was buried in an unspecified civil cemetery and now has no known grave. He is also commemorated on the Stock Exchange War Memorial in London. He left £13,291 14s 6p.

Pawle’s mother, Clotilda Agatha Pawle, was the eighth child and youngest daughter of Philip Hanbury (1802–78) and Elizabeth Christina Hanbury (née Collot d’Escury) (1818–77) (m. 1845). At the time of the 1871 Census the family was living at “Woodlands”, an estate of 27.5 acres, London Road, Reigate, Surrey (six servants). Philip Hanbury was a member of a banking family whose trading history goes back to the eighteenth century and whose London premises were 60, Lombard Street, London, EC3 (more recently the headquarters of TSB). In 1864 the banking firm known as Hanbury, Lloyds & Co. amalgamated with the firm of Hoare, Barnett, Hoare & Co., and in 1884 Lloyds Banking Co. took over the firm of Barnetts, Hoares, Hanbury & Lloyd. Pawle’s mother’s family was prominent in southern Africa.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Francis [II] (“Frank”, later JP) (1883–1954); married (1913) Doris (“Dorrie”) Nellie Judd (b. 1891 in Salisbury, North Carolina, d. 1977); one son, two daughters;

(2) John [I] (1884–1960), married (1912) Margaret Dorothy Love (1890–1962); two sons;

(3) Hanbury (“Tim”; later Brigadier, CBE, DL, TD) (1886–1972); married (1915) Mary Cecil Hughes-Hallett (1890–1971); one son, two daughters;

(4) Eveleen (1889–1948);

(5) Frederick Strachan (1899–1996); married (1918) Dorothy Kathleen May (1896–1992);

(6) Wilfred George (1901–69); married (1936) Betty Marion Sherwell (b. 1907, d. 1988 in Valencia, Spain); 1 daughter.

Francis [II] Pawle was educated at Haileybury (where he was a cadet in the Junior Officers’ Training Corps) and, from 1901 to the end of Michaelmas Term 1904, Merton College, Oxford (where he began by reading Classics but probably ended up reading for a Pass Degree). On 10 December 1904, the College’s Warden’s and Tutors’ Committee resolved, however, that “Mr Pawle be required to take his name off the books at once, for drunkenness and disorderly conduct in the streets” (i.e. sent down from the University) as he had been gated for “drunkenness and disorderly behaviour” twice before. But two days later, in what was clearly an extraordinary meeting of the same Committee (since Pawle was the sole subject of discussion), it was resolved “that the resolution of Dec. 10 be rescinded and that Mr. Pawle be permitted to take his degree in July 1905, on condition that he does not come into Oxford in the interval”. In April 1902, Francis was apprenticed for seven years with a stockbroker who was also a member of the Skinners Company, one of the London Livery Companies.

During World War One, Francis [II] served in the 2/1st and then the 1/1st (Regular) Battalion of the Hertfordshire Regiment, part of the 118th Brigade, 39th Division from 29 February 1916. He was commissioned Temporary Lieutenant on 17 September 1914, and promoted Temporary Captain on 29 September 1914 and Temporary Major on 5 August 1918. From 19 to 30 March 1915 he was a 2nd-class instructor at the Machine-Gun School, Bisley. On 13 November 1916, during the penultimate phase of the Battle of the Somme that is known as the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November), Francis was wounded by shrapnel in two places in his right thigh when the 39th Division was attempting to take the Hansa Line at Thiepval/Beaumont Hamel. The wound went septic and he was sent back to England, arriving in Southampton from Le Havre on 21 November 1916. He spent time in King Edward VII Hospital for Officers, which was then situated at 9, Grosvenor Gardens, London SW1, and on 8 January 1917 a Medical Board gave him two months’ sick leave. But by 10 March 1917 his lower wound had not healed properly, and when it was realized in August 1917 that the wounding had permanently damaged his leg, he was given light duties in the 5th (Reserve) Battalion (until 8 April 1916 the 3/5th Battalion (Territorial Forces)) of the Bedfordshire Regiment. On 17 September 1917 he reported for duty with the Ministry of Munitions and relinquished his commission on health grounds on 7 February 1918.

Francis [II] later became a Director of the Melbourne and General Investment Trust and his brother Frederick Strachan became its Chairman. Like two of his younger brothers, Francis was a passionate beagler and had his own pack even before the Great War. Indeed, he was so keen on the sport that his pack would occasionally meet before dawn for a couple of hours’ hunting before he left to work in the Stock Exchange. Francis was also an enthusiastic cricketer, and for over 50 years he and his father raised teams to play against nearby Haileybury. After World War Two, Francis restored the family’s private cricket ground, placed it at the disposal of Widford’s Cricket Club, and gave the local football club facilities to play on one of his pastures. He was also a “first-class game shot” and organized shoots “in the old style, with most of the staff from his gardens and from his farm and many others from the village taking part in the day’s fun”. He left less than £7,000.

Francis [II]’s only child was John [II] Hanbury Pawle (1915–2010). He was educated at Harrow, where he became Captain of Cricket, and in 1934 he matriculated at Pembroke College, Cambridge, from where he graduated in 1937 with a BA in Economics and History, after which he did a course at Westminster School of Art before becoming a stockbroker like so many of his family. While at Cambridge he distinguished himself as a sportsman, gaining a Double Blue at cricket (1936 and 1937), a Blue at tennis, and a Half-blue at Rackets (1937). When World War Two was imminent, he was gazetted Probationary Lieutenant on 5 August 1939 and thereafter served in destroyers in the Dover Patrol Squadron and the North Atlantic. In 1939 he married Doris Tolkien (1915–93); they had three sons and one daughter. After the war he returned to the City, retiring in 1979 as a partner with Fielding, Newson, Smith (stockbrokers). He also continued his sporting activities, playing cricket for Essex from 1935 to 1947 and becoming the British amateur rackets champion from 1947 to 1950. He was also Master of Widford Beagles and published a little book on the subject entitled Hints on Beagling in 1976. After retiring from the City, he became a full-time painter, producing a host of cheerful, attractive, semi-abstract works, mainly still lifes and Mediterranean landscapes, in some of which the influence of Van Gogh’s late pictures is particularly evident. Between 1981 and 2009 his work was shown in over 20 exhibitions, mainly in Britain but sometimes also abroad.

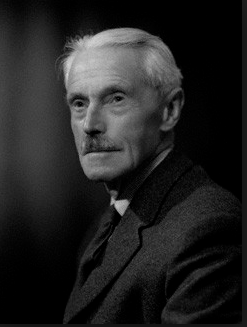

John [II] Hanbury Pawle (1915–2010)

(Photo first published in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 22 August 1956 (no issue number), p. 1)

John [I] Pawle, who lived at Havers Park, Bishop’s Stortford, served in the 1st Battalion of the Hertfordshire Regiment as a Captain (promoted 11 January 1915) and CO of the Bishop’s Stortford Company. He was twice wounded during the early stages of the war, severely at La Bassée/Béthune in February 1915, when it was feared for a time that his wounds were fatal. But although he lost one eye and the sight of the other was badly impaired, disfiguring him for life, he made a marvellous recovery, and by summer 1915 he was expressing a desire to return to the front. Ill health caused him, however, to resign his commission on 30 July 1916. After the war he became a stockbroker and, like many others, was ruined by the so-called Clarence Hatry scandal of 1929 when it transpired that Clarence Hatry (1888–1965) and three others had, via wholesale forgeries of bearer securities in trustee stocks worth £795,000 (c.£27,000,000 in 2005), been defrauding a large number of investors. They were tried in 1930 and Hatry was sentenced to 14 years’ penal servitude, which included hard labour. For 37 years John [I] was the Secretary of the Association of Masters of Harriers and Beaglers. He left £439 8s. 9d.

The financial consequences of the Hatry scandal compelled John [I]’s older child, (Shafto) Gerald (Strachan) Pawle (1913–91), to leave St Peter’s School, York, where he had been a boarder. But he was given a job on the Yorkshire Post and became a well-known cricketing reporter and correspondent. He served in the Royal Navy during World War Two, worked for The Times and the Telegraph after the war, and wrote several successful books (see the Bibliography below). In 1953 he married Lady Mary Clementine Pratt (1921–2002), the eldest child and only daughter of John Charles Henry Pratt (1899–1983), since 1943 the 5th Marquess of Camden (whose third wife was Cecil Rosemary (1921–2004), the only daughter of Brigadier Hanbury Paul, John [I]’s younger brother: see below). Gerald and his wife made their home at Tresona, St Mawr, Cornwall, and in 1980 he became High Sheriff of that county.

Hanbury Pawle was educated at Haileybury from 1900 to 1903, became a professional soldier, and was gazetted Second Lieutenant on 12 July 1911, promoted Lieutenant on 12 November 1913 and Captain on 11 January 1915. During World War One he served in both the Hertfordshire and the Bedfordshire Regiments and was awarded the Croix de Guerre (France) on 9 December 1916 for the part his Battalion had played in the Battle of the Somme. He rose to be the CO of the Hertfordshire Regiment (promoted Lieutenant-Colonel on 1 January 1931), but during his retirement he shifted his military activity from the Regular to the Territorial Army (TA), and in 1936 he is referred to in a legal document as a “Colonel”. In summer 1938, now a Temporary Brigadier, he commanded the 161st (Essex) Brigade (TA) when it participated in two weeks of manoeuvres in Kent that prepared the men for night operations and gas attacks, trained the officers in “battle procedure” and taught them how to translate the theory into flexible practice. From August to November 1939, still a Brigadier, he commanded the same Territorial Brigade – now enlarged from four to eight volunteer battalions. Four of these were taken from the Essex Regiment and two each from the Middlesex and Royal Berkshire Regiments, and they totalled 5,000 men (as opposed to 2,267 men in the previous year). Finally, in 1940, he was appointed General Officer Commanding the 202nd Independent Brigade (TA). When he finally retired in 1944, he was made an Honorary Brigadier.

In civilian life Hanbury became a Director of McMullen & Sons, the Hertford Brewery, and a Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Hertfordshire. During World War Two he wrote several handbooks for Territorials and the Home Guard (see Bibliography below), and between 1930 and 1955 he wrote one or two books of fiction with highly moral and religious messages. His first novel, The Sacred Trust (1930), is basically a romance that is played out providentially during the 1920s in a large cantonment in Bareilly, a north Indian city in the province of Uttar Pradesh. But one reviewer described the novel as “a story which vividly contrasts the life of the idle rich and those who, as employers or in other capacities, regard wealth as a sacred trust and care for the well-being of others”. In its opening and concluding chapters, its moral centre, the ageing factory owner Stuart Marsden, preaches a Christian Socialism that recalls the philanthropic work of such families as the Rowntrees and the Cadburys over the previous century. In the 1930s he lived at “Mylnefield”, Great Amwell, near Ware, Hertfordshire; in the 1950s and early 1960s he lived at Nether Hall, Widford, Ware; and by mid-1963 he gave his address as Home Field House, Widford, Ware. Hanbury Pawle was a committed churchman in the Anglo-Catholic tradition and was clearly worried by the decline of organized religion in a world that “has changed during the past 40 years almost beyond recognition” and which he saw expressed in “the low attendance at church on Sunday by ‘the younger generation’”. He published a letter on the subject in The Times on 9 July 1956 in which he attributed the decline to the fact that Christians were required to assent to doctrines and ideas that were irreconcilable with modern thinking and couched in antiquated, unacceptable or excessively flowery language. He continued in the same vein with two more letters to The Times that appeared on 22 January 1962 and 1 June 1963, but voiced the opinion in the earlier of the two that a Reformation was in the offing which could solve the problem, clearly thinking of the new translation of the New Testament that had appeared in 1961, the new translation of the Old Testament that would appear in 1970, and the alternative Prayer Book that would come into use in 1965. His hopes may have been optimistic, but they were expressed when Hanbury Pawle was nearly 80, and they show an open-mindedness which one does not normally expect from a senior military man of that age and generation.

Hanbury Pawle, CBE, DL, TD, by Bassano Ltd (19 July 1961)

(Photographs Collection (NPG x171005); copyright National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London, purchased 2004)

Hanbury’s younger daughter, Rosemary Cecil Pawle (1921–2004), became a well-known painter. Her first married name was Townsend after her marriage in 1941 to Group-Captain Peter Woolridge Townsend (b. 1914 in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), d. 1995); marriage dissolved in 1952; two sons. Her second marriage (1953) was to John Adolphus de Laszlo (1921–90); one son, one daughter; marriage dissolved in 1977. She then became the 5th Marchioness Camden after her marriage in 1978 to John Charles Henry Platt, 5th Marquess of Camden (1899–1983). Peter Townsend was a top-scoring fighter ace during World War Two, who became Equerry to King George V in 1945 and then to Queen Elizabeth II from 1952 to 1953. In the early 1950s he was romantically linked with Princess Margaret (1930–2002; later Countess of Snowdon), left the RAF in 1956 after spending three years as the Air Attaché in Brussels, and in 1959 married a Belgian woman, Marie-Luce Jamagne (1939–95). John de Laszlo was an exporter and stockbroker, and the son of the society painter Philip Alexius de Laszlo de Lombos (1869–1937) and Lucy Madeleine Guinness (1870–1950).

Frederick Strachan Pawle joined the Royal Field Artillery as a Gunner on 27 July 1917 and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 23 December 1917. He served in France, but returned to England on 11 August 1918 suffering from a minor disorder which was operated on on 19 August 1918. Although on 1 October 1918 he was deemed to have recovered, he was sent on a month’s convalescence leave and was demobilized on 14 January 1919. After the war he became a stockjobber.

The brothers’ one sister, Eveleen Pawle, became an Anglican Benedictine nun in Stanbrook Abbey, Callow End, near Malvern, Worcestershire, and was there until her death. The order – a contemplative one – was founded in Cambrai, Flanders, in 1625 under the auspices of the English Benedictine Congregation by Sister Gertrude More (1606–33), the great-great-grand-daughter of St Thomas More (1478–1535). In 1793, i.e. during the French Revolution, it was forced to seek refuge in England after its property had been seized and the sisters had spent 18 months in prison in Compiègne under very harsh conditions. The destitute nuns had no permanent home until they were able to have a new abbey built, a process which started in 1838 and went on until 1886. In 2002 the Community decided to move as the original house no longer met their needs, and in 2009 it moved into an “eco-community house” at Crief Farm, Wass, North Yorkshire.

Other members of the Pawle family who were killed in action in World War One

Three other members of Pawle’s family were killed in action in or died because of the war. On his father’s side:

(1) Malcolm Gerald Pawle (1874–1917), the youngest brother of Pawle’s father and thus Pawle’s uncle;

(2) Captain Derek Weatherall Pawle (1887–1915), the son of Lewis Shepheard Pawle (1859–1947), another, older brother of Pawle’s father, so Derek was Pawle’s cousin. Lewis Shepheard described himself as a gentleman and when Derek Weatherall was killed in action, the family was living at Hutchin’s Barn, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. But by the time of Lewis Shepheard’s death, it had moved to 2, Albert Hall Mansions, Kensington Gore, London SW7, on the south side of Hyde Park.

On his mother’s side:

(3) Randolph Frederick Barclay Hanbury (1886–1917), the third son of Frederick Barclay Hanbury (1848–1925) and Edgiva Hanbury (née Clarke) (1855–1918) (m. 1875), who had four sons and three daughters. Randolph’s wife was Lily Georgina Hanbury (née Bessant) (1884–1972) (m. 1910); one son, two daughters, living at 177, Blagdon Road, New Malden, Surrey.

Derek Weatherall Pawle was educated at Harrow School and the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) and began his Army career as a Second Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of the Border Regiment at Pretoria, South Africa, in 1906. In 1908 he was seconded to the 2nd Battalion of the Northern Nigerian Regiment, part of the West Africa Frontier Force, and by April 1915 he was stationed on Nigeria’s eastern frontier with the new German colony of Cameroon, ceded by the French in 1911. He was stationed at the tiny village of Gurin, on the Faro River between Garna and Yola and c.700 miles north of the sea, commanding a force that consisted of one colour-sergeant and 41 Nigerian soldiers and police constables and was tasked with the defence of a circular mud fort that marked the frontier. The force also included the local political officer, Captain Joseph Frederick John Fitzpatrick (c.1882–1942), who was a Reserve Officer and had been in the Nigerian Service since 1907, but who had served with some distinction in the Second Boer War as a subaltern the Essex Regiment.

Captain Derek Weatherall Pawle (1887–1915)

At 05.00 hours on 29 April 1915, the Germans, commanded by Captain von Crailsheim, made a surprise incursion into Nigerian territory. They sent in 350 infantry and 40 mounted infantry who were led by 16 European officers and equipped with four maxim guns which enabled them to inflict considerable damage on the mud fort, which they attacked from two directions. The ensuing battle lasted seven hours “and was of a particularly fierce character”, but at noon the German force withdrew most of its men – probably because, after firing some 60,000 rounds, they were running short of ammunition – after losing three officers and 33 soldiers killed and four officers and 28 soldiers wounded. In contrast, the Nigerians lost one non-commissioned officer and ten soldiers wounded and three soldiers and one officer – the newly promoted Captain Pawle – killed in action. After the battle, Captain Fitzpatrick, who would go on to be the Senior Administrative Officer in Northern Nigeria, said the following in a letter to Derek Weatherall’s father:

… Your son, who was O. C. Troops, could have withdrawn his little force and retreated. No thought of the kind suggested itself to him. He opened fire at the enemy at once, and we had a very heavy action from 5 a.m., the enemy using three of his guns continually and making repeated attempts to get his infantry up to the assault. Your son was shot through the head soon after the start of the action. He dropped at once and did not suffer at all. When he was killed he was in the act of getting the men to fire at the right range, going from loophole to loophole constantly, in the bravest possible manner. He smoked a cigarette all the time, and set a great example of courage and selflessness to us all.

Pawle’s body was originally buried at Gurin but is now buried in one of the three Commonwealth War Graves Commission graves to be found in Yola Station Cemetery at Adamawa, near the west bank of the River Benue.

Randolph Frederick Barclay Hanbury, a nephew of Pawle’s mother, joined the Royal West Kent Regiment as a Private and then transferred to the Machine Gun Corps. He was killed in action, aged 31, on 3 May 1917, the second major part of the Battle of Arras (3–15 May 1917) and has no known grave.

Education

Like his father before him, Bertram Pawle attended Haileybury (Haileybury and Imperial Service College from 1942) from 1906 to 1911. As a member of Highfield House, he had “a clean, vigorous, splendidly successful School life”, according to his housemaster there, the Reverend Thomas Dewe, MA (1865–1960; Scholar of Brasenose College 1884–87; awarded a 2nd in Mathematics in 1887; assistant master at Haileybury 1891–1923; Senior Assistant Master [Second Master] 1919–23; ordained deacon 1894, and priest 1895). Pawle was a member of the First cricket XI (1908–11; Captain 1911) and played seven innings at Lord’s; and after leaving school he became a Minor Counties cricket player (1911–12). According to Dewe, he could also have gained his Colours in football if illness had not intervened, but made up for this by being one of the 1st Racquets Pair (1910–11; Captain of Racquets 1910–11), playing in the Public Schools Championship, and promoting the game at Haileybury. In his final year at Haileybury, he became a College Prefect and, in 1911, Head of his House and Cadet Lieutenant (the Senior Cadet Officer in Haileybury’s Officers’ Training Corps). During his two final years at school he showed a growing aptitude for public speaking: he won the Mason Recitation Prize in 1910 and became the Secretary of the Debating Society in 1911.

After passing Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1910, Pawle matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 17 October 1911 and read Classics. During his time at Magdalen, he became Master of New College and Magdalen Beagles and Captain of the College Cricket XI. Although President Warren’s obituary in the Oxford Magazine conceded that Pawle was “of good intellectual ability and always ready to do his duty”, it also said that he had opted for the Honours course “more in virtue of these qualities than because he was a scholar”. Similarly, although the Revd Dewe would later say that Pawle was “very keen on taking a good degree and on being an educated man”, he achieved only a 4th when he took the First Public Examination in the Hilary Term of 1912 and Classical Moderations in the Hilary Term of 1913. Pawle then began reading for Greats, in Trinity Term 1913, but left without taking a degree on the outbreak of war.

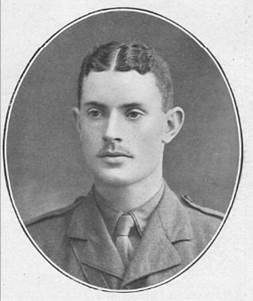

Bertram Pawle

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Bertram Pawle

(Photo first published in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, no. 2,188, 21 August 1915, p. 5)

“I always thought that the services under the [Chapel] dome were the most beautiful and inspiring things in my life, but now, although we have to use a shed or a ruin for a chapel and have to get up at an unearthly hour to attend, I think even they are surpassed” (Pawle’s final letter to the Revd Thomas Dewe shortly before he was killed in action).

In a brief obituary that appeared in R.L. Ashcroft’s history of Haileybury, the author described Pawle’s housemaster as follows: there was “a disarming simplicity and sanctity about Dewe, almost a childlikeness which was very lovable. He always thought the best of everyone, and many tried to live up to his estimate of them.” The accuracy of this characterization comes across very clearly in an obituary of Pawle in which Dewe had said of him:

Bertram Pawle’s first act at Haileybury was to play cricket as a boy of 14 just before he joined [July 1906] and it was likewise his last as captain of the XI at the end of his fourth year in the team. In between he revealed himself as the very best product [that] cricket at an English Public School can mould. Knowledge, patience, quickness of decision, courage, joyous leadership, they all became his. The coveted opportunities of leadership, such as being Head of House, came quite late to him in his last year; he was content to wait and to co-operate loyally in his characteristic fashion. […] The fourth son of a loyal and generous Haileyburian father, he might have been said to have inherited a successful career; but although in the first few steps his heritage may have helped him, he threw himself so thoroughly into all he undertook that he quickly justified each advance. To give a single instance of capacity – twice in succession, by good leadership, [he] won for Highfield [House] and its smaller section the Army Bugle. To me, the attractiveness of his friendship seemed his greatest possession. Such a quality ensured his happiness at Oxford, and indeed gave him an entrance into the most coveted friendship of the Oxford of his day. A really brilliant career seemed open to him. Then came the avalanche of 1914.

The cryptic reference at the end of the letter is to Pawle’s friendship with the Prince of Wales, with whom he shared a passion for beagling, and in 1996 Magdalen acquired 26 letters etc. which the Prince of Wales had written to Pawle (1913–15). On 16 September 1915 the Prince wrote with evident sadness to President Warren that he doubted whether they would ever see Pawle – who was still officially missing – again. Dewe, who loved Pawle like the son he did not have (he was married with two daughters) showed similar but even stronger feelings about Pawle and his potential in a long, hand-written memorial that he wrote for Pawle’s mother in August 1915. Here he affirmed that “in his quiet school-boy days [Pawle] had always imbibed the noblest inspirations of surroundings” and that “for the full four years [at Haileybury Pawle] had followed out a high standard of consistent Christian life”. As, judging from Dewe’s remarks about cricket that were quoted above, he clearly considered sport the most important way of giving proper shape to that life, his memorial concentrated on Pawle’s sporting prowess and achievements. Consequently Dewe had very little to say about Pawle’s academic and intellectual capabilities – except that he had “plenty of ability” in Mathematics and “produced his work with most welcome neatness”. But above all, Dewe sensed the intimate connection between Pawle’s character as it had developed at Haileybury and the military personality that he had developed in the Army, speaking of “the deep chivalry of his character” and “chivalrous resolve”, his “normal fearlessness”, his natural authority and capacity for leadership, and his instinctive ability to function as one of a unit. Thus, when Pawle was Captain of the first XI, a post which Dewe described as “onerous and responsible”, “he just placed himself at the service of his side, playing according to the game – willing to take his risks enjoying each big drive just a little more than the most delighted spectator. I doubt if he ever considered his average or analysis”. President Warren’s obituary involves a similar appreciation:

Bertram Pawle […] was again a young fellow of quite unusual attraction, and an ideal young Englishman and young officer. […] But all through, successful as he was, he was something more than his achievements. […] Graceful, attractive, successful in everything to which he turned his hand, he was always most modest. “I am afraid I have done very little,” he wrote to the President when he was gazetted, “to enhance the glory of the College lilies, but I have tried never to disgrace them, and perhaps there I have been successful”.

Military and war service

On 26 August 1912 Pawle was commissioned Second Lieutenant (University Commission) in the 8th (Service) Battalion, the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) (London Gazette, no. 28,879, 25 August 1914, p. 6,696). It was formed on 21 August 1914 with Acting Lieutenant-Colonel Ronald Maclachlan (c.1873–1917), the brother of Alexander Maclachlan, as its CO, and although no rifles were available until late October, the men were kept busy with squad drill, marching and physical training: they learnt to shoot in November. Pawle, who thanks to his educational background was already skilled in military affairs, was promoted Lieutenant on 7 December 1914 and Captain on 6 March 1915 after attending a course at the Staff College which he passed with distinction. Not surprisingly, in two letters to President Warren (30 September [1914] and 20 November 1915), Lieutenant-Colonel Maclachlan, who would be killed in action on 11 August 1917 as the GOC (General Officer Commanding) 12th Infantry Brigade near Loker (formerly Locre), ten miles south-west of Ypres, was fulsome in his praise for Pawle, describing him as “one of my best officers” and his death as “a grievous loss”, not least because he was “simply loved by the men”. It was probably to these comments that President Warren was referring when he wrote in the Oxford Gazette that Pawle’s “chief, Colonel Maclachlan, […] had the highest opinion of him and spoke of him in the warmest terms.”

By May 1915, the Battalion was ready to go to France, where it disembarked on 20 May as part of the 41st (Greenjacket) Brigade, the 14th (Light) Division. From 28 May to 2 June, it was in the trenches near Bailleul and taking casualties. After more instruction in trench warfare, it went into the line for the second time on 7 June, just south of Sint Elooi. On 16/17 June, during the First Action at Hooge (cf. H.N.L. Renton and J.J.B. Jones-Parry), when the 3rd Division incurred heavy losses while trying to take the German trenches on Bellewaerde Ridge, just to the north of Hooge, Pawle’s Battalion was in Reserve. It then marched to Vlamertinghe where it rested for ten days before being sent, on 29 June, to trenches a quarter of a mile south of Hooge, in Railway Wood, south-east of Ypres, where it experienced a gas attack and shelling on 2 July.

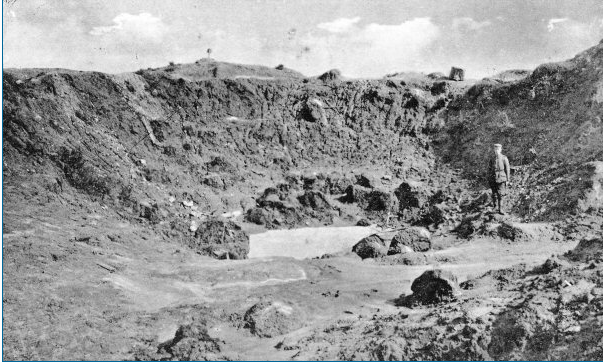

On 26 July, while the Battalion was resting near Poperinghe from 9 to 21 July, Pawle and two other Captains went to inspect the trenches that the 14th (Light) Division was soon to take over from the 3rd Division (which had been fighting in France since August 1914 and in the Ypres Salient since October 1914). The new trenches were north of Zouave Wood and Sanctuary Wood, and ran along the north side of the east–west Menin Road, just to the south of Bellewaerde Lake and through the destroyed village of Hooge. As the ruins of Hooge village and Château protruded from the flat Belgian landscape, they were considered strategically important, and so, on the evening of 19 July, the departing 3rd Division blew a huge crater under the ruins that was 120 feet wide and 20 feet deep, and protruded 15 feet above the earth’s surface. The crater, created for defensive purposes, would prove to be the Battalion’s nemesis, but as the Germans had been driven out of it, the potential danger was not recognized at the time and the crater was insufficiently protected by barbed wire.

Hooge crater: taken in 1915 by a German photographer (cf. the uniform of the soldier to the right of the picture)

So at 21.00 hours on 29 July, Pawle’s Battalion set off for its new positions and reached them at about midnight – ominously, without any interference from the Germans who, it is now believed, had intercepted the British wireless and telephone traffic and knew that an inexperienced unit was in the trenches opposite them. With the crater in between them, ‘A’ Company (Lieutenant Sidney Clayton Woodruffe (1895–1915), aged 19, awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his part in the action) was in the trench to its left and ‘C’ Company (Captain Edward Foss Prior (1888–1916)), which would bear the brunt of the imminent German onslaught, was in the trench to its right. ‘B’ Company (Captain, later Major, Alwyn Lionel Compton Cavendish (b. 1890 in India, d. 1928 in Sudan)), ‘D’ Coy (Captain, later Lieutenant-Colonel, Arthur Charles Sheepshanks (1885–1961)) and Battalion HQ were in Reserve, 400 yards to the rear, in the north of Zouave Wood.

Then, just before dawn at 03.15 hours on 30 July 1915, the Germans poured liquid fire from Flammenwerfer (flame-throwers) – the first use of this weapon during the war – into the excessively narrow, tightly packed trenches and then shelled them for two to three minutes. Bombers (specialist grenade-throwers), then charged through the virtually unprotected and undefended crater and swung right and left along the trenches, worsening the panic and killing any survivors who had not, unlike Woodruffe and some of his men, managed to organize themselves. According to the letter that Lieutenant-Colonel Maclachlan wrote to President Warren on 20 November 1915, Pawle was killed in action when he was trying to do just this: “up in front rallying sorely startled men”. A counter-attack at 04.00–05.00 hours by ‘B’ Company was shot to pieces by carefully placed machine-guns that swept the open ground between Zouave Wood and the trenches, as was ‘D’ Company when it counter-attacked at 14.45 hours. The action, which enabled the Germans to penetrate the British lines opposite the much disputed Hooge Château, cost the Battalion 488 casualties killed, wounded and missing out of its initial strength of 769, including Pawle, aged 23, one of the 19 officer casualties (cf. H.N.L. Renton and J.J.B. Jones-Parry). Ironically, one of the Battalion’s five officers to survive the débâcle unharmed was a Major Tod, the German word for “death” (cf. V.G.F. Shrapnel); he later became an Instructor at the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) and seems to have survived the war.

Liquid fire being used at Hooge in 1915 (German photo)

The Battalion War Diary does not tell us where or how Pawle was killed in action; nor do any of the obituaries tell us much about the horrific circumstances of his death. But the obituary that appeared in the Hertfordshire Mercury hinted obliquely at what had happened when it styled Pawle as “another precious young life [to have been] sacrificed to the Moloch [an ancient Ammonite god to whom children were allegedly sacrificed by fire] of German militarism and aggression”. Furthermore, the letters from Pawle’s men that were collected by the Army after the débâcle in an attempt to give a coherent account of what had happened to Captain Pawle are wildly divergent. According to Sergeant Frederick F. Birmingham (1883–1940), writing from a Hospital Ship on 13 October 1915, Pawle was “most certainly dead” and his body “would have been lying out between the lines in Sanctuary Wood unless he has been burned”, because “nearly all the Company saw him killed as he was leading them on the 30th July at Hooge. We made a counter attack in the afternoon [14.45 hours according to the War Diary] after they had driven us out by liquid fire.” But Rifleman William James, writing on 30 August 1915, claimed that he heard a Sergeant state that “he saw Captain Pawle [being] taken prisoner by three Germans at Hooge”. Another witness, Sergeant [later Colour-Sergeant] Rupert S. Belding (1878–1952), thought (2 September 1915) that Pawle had been killed during the liquid fire attack itself and stated categorically that there was “no hope of the above [officer] having escaped”. And a fourth witness, Rifleman F. W. Carter, stated on 30 August 1915 that he saw Pawle “leave the firing line trench and go forward […] with a bombing party of about 12 in all” and that the only member of the party to get back was Corporal (later Sergeant) Charles J. Saxby (1876–1932), who later told him “that the whole party was lost, as the Germans cut them off”.

But in his letter which accompanied the obituary in the Hertfordshire Mercury, Lieutenant-Colonel Maclachlan, who seems to have heard the rumours that were circulating and who was certainly more aware than his men of the distortions that can be caused by the fog of war, wrote:

The facts are shortly these: On the night of 28–29th we took over a line of trenches at [Hooge], and just at dawn that morning the Germans, using some foul form of liquid fire, assaulted the trenches we held. I can only get the most confused accounts of what happened, as practically the whole company has disappeared, but the last I heard of your son he was most gallantly fighting and rallying the men. He was seen on the top of the parapet firing at Germans at close range, and I am certain he fought it out to the last. I pray God that by some lucky chance he may be alive and in German hands, but it is but a faint hope […]. He was with two other officers of the Company at the time [both were kia at Hooge on 30 July 1915] […] [Lieutenant Sidney] Milsom [1886–1915, no known grave] and [Second Lieutenant Thomas Keith Hadley] Rae [1890–1915, no known grave], and they too are missing and believed to be killed. He was a natural soldier and an ideal leader of men, who had the most supreme confidence in him. No other officer knew his work better […] I have been in close touch with your boy for just a year […] and he has been one of my mainstays ever since.

The Hooge crater was recaptured on 9 August by the 2nd Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, part of the 18th Brigade in the 6th Division (see H.W. Garton and C.F. Cattley).

President Warren wrote a letter of condolence to Pawle’s parents, to which his father replied on 13 August 1915:

I know Bertram valued your good opinion more than anybody else’s, and he did try his hardest to live up to a high ideal of life. To me he was an inspiration. It may be that the God who gave him to me wished to spare his pure soul from the agonised trials [that] civilisation and Humanity must suffer when men’s fury is exhausted. We give our grateful thanks to Almighty God for his 23 years of glorious life. ‘’tis better to have loved and lost / than never to have loved at all’ [Alfred Lord Tennyson, In Memoriam, Canto 27, stanza 4]

And Dewe’s Memorial concludes with the following appreciation of Pawle’s death before quoting three stanzas of the same poem:

He offered himself. Offered himself with all his powers to live a soldier’s life – to be a soldier, willing to live up to the limit of his oath[,] a member of that noble army who steadfastly set their faces to meet their hour, even though the goal, should[ered] so early, be the great white cross, the final earthly moment and witness of their whole haunted [?], noble self-surrender.

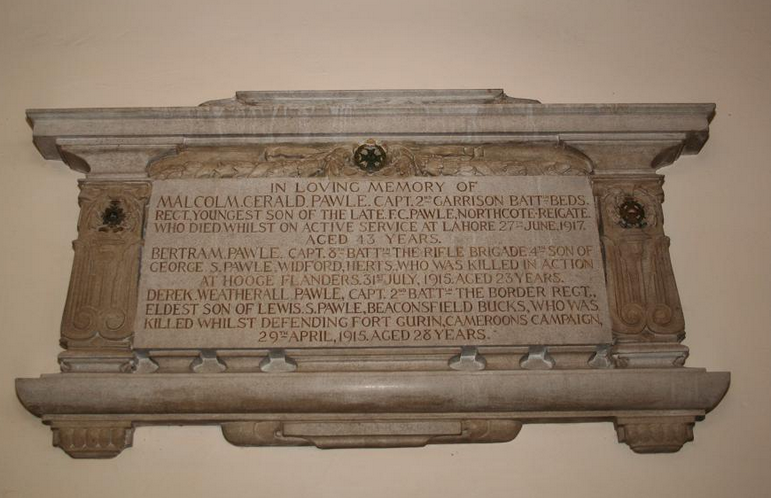

Pawle has no known grave and is commemorated on Panels 46–48 and 50 of the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial; on the Memorial Tablets in the Chapel Cloisters at Haileybury; in a memorial volume entitled Memoirs of Bertram Pawle’s Days at Haileybury that was presented to his mother after his death; on an alabaster family memorial plaque in St Mary Magdalene’s Church, Reigate, Surrey; and finally on a wall monument in St John the Baptist Church, Widford, that is inscribed:

In Memory of Bertram Pawle, Captain 8th Battalion The Rifle Brigade and of Magdalen College Oxford, Fourth Dearly Beloved Son of George Strachan and Clotilda Agatha of this Parish, Fell in Action at Hooge 31st July 1915 and lies buried on the field of battle in Flanders. Age 23 years ‘It is not the length of life that counts, but what is achieved during that life’.

Pawle died intestate but his estate was valued at £730 10s.

The memorial plaque to the three members of the Pawle family who lost their lives in World War One in St Mary Magdalene Church, Reigate, Surrey

Pawle’s plaque and scroll, the memorial that was sent to the next-of-kin of all killed in action from Britain and the Commonwealth, had not reached Pawle’s family by mid-January 1919, i.e. three-and-a-half years after Pawle’s death. When Pawle’s father received the official letter of apology from the War Office for this state of affairs, he jotted the following terse reaction in the margin of the official reply form: “I suppose one may expect this in say another 3½ years.”

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘A Ten to One Fight: British Garrison’s Victory in Cameroons’, The Observer, no. 6,480 (1 August 1915), p. 8.

G.W. Rundall, ‘“A Ten to One Fight”’ [letter to the Editor], The Observer, no. 6,481 (8 August 1915), p. 12.

[Anon.] ‘The Late Captain Bertram Pawle’, Hertfordshire Mercury, no. 4,207 (7 August 1915), p. 7 [photo].

[Anon.], ‘Captain Bertram Pawle’ [obituary], The Times, no. 40,933 (14 August 1915), p. 5.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’ [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, extra number (5 November 1915), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘Capt. John Pawle’, Essex Newsman, No. 2,430 (5 August 1916), p. 1.

[Anon.], The History of the Royal Fusiliers “U.P.S.”: University and Public Schools Brigade (Formation and Training) (London: “The Times”, [July] 2017), passim.

[Anon.], ‘Brigadier-General R.C. Maclachlan’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,558 (16 August 1917), p. 9.

Berkeley and Seymour, i (1927), pp. 107–11, 120–30.

H.S. Clapham, Mud and Khaki: The Memoirs of an Incomplete Soldier (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1930) (Reprinted by the Naval & Military Press, 2003).

[Anon.], ‘Hatry Case Ended’, The Times, no. 45,420 (25 January 1930), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘G.S. Pawle’ [obituary], The Times, no. 47,327 (19 March 1936), p. 19.

[Anon.], ‘Method in Army Training: Battle Procedure’, The Times, no. 48,072 (13 August 1938), p. 15.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. Francis Pawle’ [obituary], The Times, no. 52,858 (17 February 1954), p.10

Hanbury Strachan Pawle, ‘“I Do Believe Them”’ [letter to the Editor], The Times, no. 53,578 (9 July 1956), p. 9.

R.L. Ashcroft, Haileybury 1908–1961 (Haileybury: The Haileybury Society, 1961), pp.26 ff.

Hanbury Strachan Pawle, ‘Religious Census’ [letter to the Editor], The Times, no. 55,295 (22 January 1962), p. 11.

–– ‘The 39 Articles’ [letter to the Editor], The Times, no. 55,716 (1 June 1963), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. Clarence Hatry’ [obituary], The Times, no. 56,346 (12 June 1965), p. 12.

Moore (1975), pp. 23–4.

[Anon.], ‘Still Painting’, The Times, no. 65,235 (7 April 1995), p. 27.

Nigel Cave, Sanctuary Wood and Hooge (London: Leo Cooper, 1995).

[Anon.], ‘John Hanbury Pawle’ [obituary], Pembroke College, Cambridge Society: Annual Gazette, no. 85 (September 1911), pp. 161–2.

Churchill (2014), pp. 130–7

Archival sources:

MCA: GPD/66/5 (Thomas Dewe [Housemaster], Bertram Pawle as I knew him at Haileybury – written for his mother [hand-written memorial dated August 1915 (unpag.) that was presented to Pawle’s mother after his death]).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: P414/C64/33 (Letter of 16 September 1915 from the Prince of Wales to President Warren).

MCA: PR 32/C/3/834-839 and 948-949 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence (Letters relating to B. Pawle [1915]).

OUA: UR 2/1/76.

WO95/1895.

WO95/4356

WO95/4410.

WO339/5386 (Malcolm Gerald/Graham Pawle).

WO339/100075 (Frederick Strachan Pawle).

WO339/11629.

WO374/52782.

WO374/52783 (Hugh Lewis Pawle).

WO374/54707 (C.E.V. Pawle)

On-line sources:

Widford Parish Council: www.widford.org.uk (accessed 23 June 2018).

Steven Fuller, The Bedfordshire Regiment in the Great War, ‘Officers died in Garrison or Home units, or attached to other regiments’: http://www.bedfordregiment.org.uk/biographies/officersdiedother.html (accessed 23 June 2018).

‘Liquid Fire Attack at Hooge’: http://www.ramsdale.org/hooge.htm (accessed 24 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Gurin’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Gurin (accessed 23 June 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Stanbrook Abbey’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanbrook_Abbey (accessed 23 June 2018).

Publications by [Shafto] Gerald [Strachan] Pawle:

Squash Rackets (London: Ward, Lock & Co.,1951).

The Secret War, 1939–45 (London: George C. Harrap & Co., 1956); also published as The Wheezers and Dodgers: The Inside Story of Clandestine Weapons (Barnsley: Seaforth, 2009).

The War and Colonel Warden [i.e. Winston Churchill]: Based on the Recollections of Commander C.R. Thompson, personal assistant to the Prime Minister, 1940–45 (London: George C. Harrap & Co., 1963).

R.E.S. Wyatt: Fighting Cricketer (London: Allen & Unwin, 1985).

Publications by Hanbury Pawle:

With V.G. Stokes, Notes for Instructors on the History of the 49th and 66th, 1st and 2nd Battalions, the Royal Berkshire Regiment (Princess Charlotte of Wales’s) (Reading: [privately printed], 1925).

The Sacred Trust: A Novel (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1930).

Notes on the Framing of Tactical Exercises for Officers of the Territorial Army (Aldershot: Gale and Polden Ltd, 1939), 5th edn 1943.

Pamphlets on Civilian Defense (London: [publisher unknown], 1940–44).

The Framing of an Exercise for the Home Guard (Aldershot: Gale and Polden Ltd, 1941).

Thoughts and Notes for the Home Guard Commander (Aldershot: Gale and Polden Ltd, 1942).

The Seven Locks (Edinburgh: Parole, 1944).

In our own Hands (Edinburgh: [privately printed], 1946).

Before Dawn (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1955).