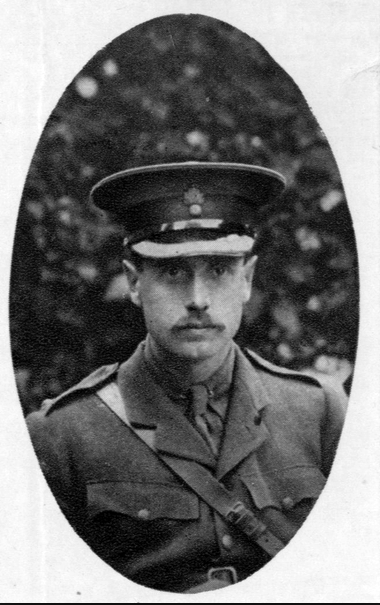

Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born: 3 March 1885

Died: 17 September 1916

Regiment: Grenadier Guards

Grave/Memorial: Corbie Communal Cemetery (Extension): 2.E.5

Family background

b. 3 March 1885 illingdonat Colham House, The Evelyns Preparatory School, Colham Green, Hillingdon, Middlesex, as the second son (of six children) of Godfrey Thomas Worsley (1842–1920) and Frances Worsley (née Hill) (1854–1947) (m. 1882). The above address was also the family home and by the time of the 1901 Census it accommodated, apart from Godfrey Thomas’s family and the 64 pupils, two assistant masters, one butler, one matron and eleven servants. By the time of the 1911 Census it accommodated, apart from the 42 pupils, two families (Godfrey Thomas’s and, from 1910, Evelyn Godfrey’s), two other assistant masters, one French Assistant, two matrons, two governesses and eleven servants.

Parents and antecedents

The Worsley family can be traced back to the reign of Henry VII and most of its members came from the gentry and professional classes.

Evelyn Godfrey’s father was the son of a clergyman; he was a schoolmaster who, after teaching at a preparatory school at Brading (Isle of Wight) in the 1880s and 1890s, came back to mainland England to become the Headmaster of The Evelyns School. In the nineteenth century there were several small private schools in the Hillingdon area, not least because of the proximity of Eton College. Evelyn’s School (founded 1872) was one of the most important of these private schools and maintained close connections with Eton until it closed in 1931.

Evelyn Godfrey’s mother was the daughter of the Reverend Melsup Hill (c.1818–91), who studied at Jesus College, Cambridge (BA 1840; MA 1869, and was ordained deacon in 1841 and priest in 1842. From 1845 to 1857 he was Perpetual Curate of St John, Kidderminster, and in 1857 he became the Rector of Shelsley Beauchamp, Worcestershire, a living with a population of 572 and a stipend of £500 p.a.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Hugh Barrington (later Commander RN, DSO) (1883–1965); married (1908) Mary Elizabeth Joan Rashleigh (1887–1971); one daughter;

(2) Madeline Rose (1884–1949), later Rashleigh after her marriage (1909) to her second cousin Dr Hugh George Rashleigh, MRCP, LRCS (1876–1948);

(3) Francis le Geyt (later Commander RN) (1886–1964); married (1914 in Rondebosch, South Africa) Irene Beatrice Guillemard (1891–1971), one son, one daughter (both b. in Nairobi, Kenya);

(4) John J. (1887–c.1889);

(5) John Fortescue Worsley (1888–1917; killed in action on 27 November 1917 near Cambrai while serving as Lieutenant with the 3rd (Regular) Battalion, the Grenadier Guards;

(6) Ralph Edward (1896–1971, in Palma, Spain).

Hugh Barrington entered the Navy on leaving school. He was gazetted Sub-Lieutenant on 15 July 1902, promoted Lieutenant on 3 January 1905 and by the time of his marriage he was a Lieutenant-Commander. He was awarded the DSO on 17 May 1918 (London Gazette, no. 30,687, 14 May 1918, p. 5,858) and mentioned in dispatches in the same year for services on the Mediterranean Station.

George Burvill Rashleigh, the father-in-law of Hugh Barrington Worsley (and Evelyn Godfrey), was a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn and the elder son of the Reverend Henry Burwell Rashleigh (1820–1916), the Vicar of Horton Kirby, Kent, from 1916 to 1927.

Francis le Geyt also entered the Navy on leaving school. He was gazetted Sub-Lieutenant on 30 November 1905 and promoted Lieutenant on 26 June 1908. Although he was transferred to the Retired List on 26 May 1913, he served in World War One with the rank of Commander. After the war, he emigrated to Kenya with his family and took up coffee farming.

Francis le Geyt’s wife, Irene Beatrice Guillemard, was the daughter of Dr Bernard J. Guillemard, a medical practitioner who had studied at Edinburgh and was the Assistant Astronomer at the Cape.

Francis and Irene’s only son, John Godfrey Bernard Worsley (1919–2000), came back to England to study Fine Art at Goldsmiths College, London, and began his professional life by producing illustrations for romantic magazines. On the outbreak of World War Two, he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and spent three years on escort duty in the North Sea and the Atlantic before becoming the youngest member of Sir Kenneth Clark’s team of official war artists. In 1943 he was made the official Admiralty artist in the Mediterranean, but later in the same year, while taking part in a raid on Italy, he was captured by the Germans, who at first thought that he was a spy because of his drawing materials. But he was finally sent to Marlag O, near Bremen, where he assisted escapes by creating the dummy prisoner of war with a papier-maché head and movable ping-pong-ball eyes that is celebrated in the film Albert RN (1953) and is now in the Portsmouth Naval Museum. After the war, John Godfrey painted many portraits of the Allied leaders, and 61 of his paintings now hang in the Imperial War Museum and 29 in the National Maritime Museum. Although he is best known for his seascapes, he also worked in glass, bronze and paint, made 700 drawings for TV versions of The Wind in the Willows and Treasure Island, and drew the illustrations for the comic strips ‘PC49’and ‘Tommy Walls’ in the Eagle comic. In the late 1960s, he became Scotland Yard’s official police artist, making sketches for eye witnesses which proved to be more lifelike than photo-fits.

Ralph Edward was educated at Radley College, just south of Oxford, from c.1903–12 and probably trained as a solicitor since he became a Private in the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”). He attested on 16 October 1914 and was subsequently commissioned into the 4th Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Dorsetshire Regiment on 12 December 1914 (London Gazette, no. 29,003, 11 December 1914, p. 10,591). The 4th Battalion had been mobilized on the outbreak of war; it trained for two months on Salisbury Plain and set sail from Southampton on 9 October 1914, arriving at Bombay (now Mumbai) on 10 November. On 18 February 1916 the Battalion sailed from Karachi; it landed in Basra on 23 February 1916, where it became part of 42nd Brigade, in the 15th Indian Division. For the rest of the war, it took part in the fighting in Mesopotamia. We do not know exactly when or where Ralph Edward joined the 4th Battalion, but he was in Alexandria, Egypt, when he was gazetted Captain on 21 November 1917. When a period of leave in England came to an end on 27 November 1918, he asked to remain there on compassionate grounds and was transferred to the Regiment’s 3rd Battalion, which had been stationed in Wyke Regis and had served as the Portland Garrison since June 1915. After being demobilized on 3 July 1919, he worked from 1919 to 1928 with Messrs Turner, Morrison & Co. Ltd in Calcutta and Bombay, and from 1928 to 1930 with Messrs Holmes, Wilson & Co. in Calcutta. He seems to have given up professional work during the 1930s and lived at Hillcrest, Vine Lane, Hillingdon, and in Chartham, near Canterbury, Kent. During World War Two, he worked in HM Dockyard, Devonport.

Wife and children

Worsley’s wife (m.1910) was Katherine Maria Theodosia Rashleigh (1888–1974); they had two daughters. She was the younger sister of Mary Elizabeth Joan Rashleigh, the wife of Worsley’s older brother Hugh Barrington, and both women were daughters of George Burvill Rashleigh (1848–1916) and Lady Edith Louisa Mary Bligh (1853–1904), the daughter of the 6th Earl Darnley (whose family seat since the eighteenth century had been Cobham Hall, north Kent, to the west of Chatham and the north of Maidstone). In 1919 Katherine was married again, to her second cousin the Reverend William Hugh Rashleigh, BA, MA (1867–1937), and once more took the name of Rashleigh: they had one son and three daughters.

William Rashleigh was the elder son of the farmer William Boys Rashleigh (1827–90) and Frances Portia Rashleigh (née King) (1836–1906) (m. 1863) of Horton Kirby, Kent. He had studied at Brasenose College, Oxford (BA 1887, MA 1889) and was ordained deacon in 1892 and priest in 1894, i.e. while he was an assistant master at Tonbridge School, Kent (1890–1900). After holding two curacies, in Gloucestershire and Kent (1900–11), he became the Rector of St George the Martyr with St Mary Magdalene, Canterbury, from 1911 to 1916, and he then moved back to his home village. He finally became the incumbent of Ridgmont, near Bletchley, Bedfordshire, a parish of 494 people that was in the gift of the Duke of Bedford with a stipend of £367 p.a. Rashleigh was the elder brother of Dr Hugh George Rashleigh, the husband of Katherine’s sister-in-law Madeleine Rose, and the second cousin of her first husband. Hugh George graduated from one of the London hospitals in 1902 and became a General Practitioner in Chatham.

Francis Evelyn George Rashleigh, DFC (1920–43) was the only son of Katherine, Evelyn Godfrey’s widow, and William Rashleigh; he married (1941) Alice Ann Hartley (b. 1919); one son. He was gazetted as a Pilot Officer on 27 June 1939. He served in 202 Squadron, an Air Sea Rescue Unit that specialized in picking up downed aircrew in Vickers Supermarine Walrus Mk II amphibian aircraft, and obtained his DFC, the Squadron’s first gallantry award for a rescue mission, in August 1941. While stationed in Gibraltar, he rescued the crew of an aircraft which had come down on the French Moroccan coast and been surrounded by 200 hostile Arabs. Rashleigh managed to land out of sight of most of the Arabs, but near enough for the crew to dash to safety. They scrambled aboard under fire and the pilot immediately turned the tail of his aircraft towards the enemy, opened his throttle, and hid their take-off behind a cloud of dust. After the cessation of hostilities in the Central and Western Mediterranean, the Squadron was moved to the Eastern Mediterranean, and at 13.30 hours on 30 September 1943, while flying a Walrus from Cyprus to Kos on a communications flight, Rashleigh, now a Flight-Lieutenant, was shot down off the island of Leros by Major Ernst Düllberg of JG27, flying a Bf. 109. Both he and his navigator, Sergeant Clifford Platt (1918–43), were killed in action, aged 23 and about 25 respectively. He and his wife had lived in Balcombe, Sussex, and the processional cross used in the village church has his name on it. He is commemorated on columns 267 and 271 of the Alamein Memorial and the War Memorial plaque in Balcombe Church.

Alice Ann Hartley later became Alice Ann Leigh-Bennett after her marriage (1948) to Thomas Neville Leigh-Bennett (b. 1915 in the Malay States, d. after 1970). He was the son of Harold Leigh-Bennett (c.1879–1949), who described himself as a Mining Engineer at the time of the 1911 Census and as a retired Civil Engineer in 1948, and who, in the late 1920s and 1930s, lived at Hillcrest, Beecham, Reading. Thomas Neville attended Shrewsbury School from 1929 to 1934, where he became a Praeposter and was a member of the First Cricket XI (1931–34) and the First Football XI (1932–34). After leaving school he was awarded an Exhibition at Brasenose College, Oxford, where he graduated with a 3rd class degree in Modern Languages (French and German) in 1938 before becoming an Assistant Master at Sedbergh School, Yorkshire. On 22 February 1941 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps and later became a Lieutenant. He married his first wife, Mary L. Poole (b. c.1919), a few months later in 1941. Their marriage was dissolved and at the time of his second marriage he was a trainee licensed victualler and living at the Royal Oak Hotel, Cobham, Surrey. In July 1950 his commission was transferred to the Secretarial Branch of the RAF Reserve and he was gazetted as Flight-Lieutenant. He later worked for the Department of Commerce and Industry, Hong Kong. His first wife remarried in 1949.

Worsley was the father of:

(1) Margaret Katherine Worsley (1911–2000), later Collet following her marriage (1935) to Mark Harold Collet (later Lieutenant-Colonel, MC, RM) (1897–1968), his first marriage (1918) having been dissolved (1934); one son, one daughter. She then became Worsley again after her marriage (1981) to Charles Edward Austen Worsley (1902–90), the son of the Reverend Canon Edward Worsley (1844–1923) and Mrs Ethel Adela Worsley (1857–1913).

(2) Diana Mary (b. 1914, d. after 1965, probably abroad), later Gutch after her marriage (1938) to John Robert Gutch (later KCMG, OBE, 1910–88); three sons.

John Robert Gutch was High Commissioner of the West Pacific from 1955 to 1961.

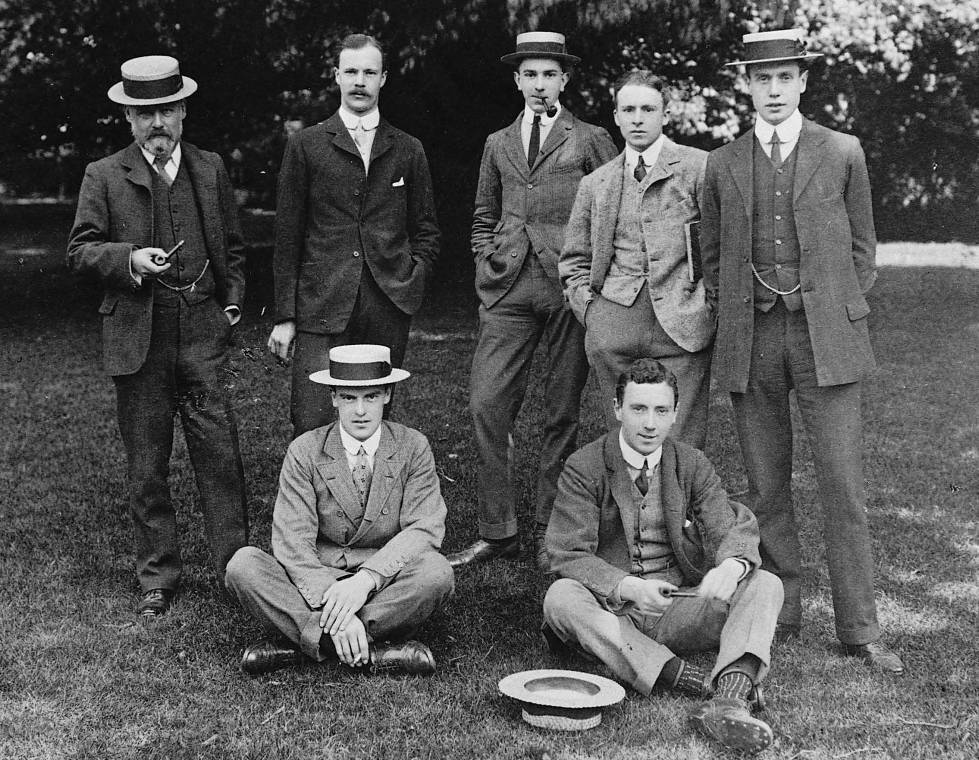

Classical Honours Moderations reading party at Cropthorne, Worcestershire (1904) (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

From left to right (standing): Christopher Cookson (Senior Tutor; Fellow of Magdalen 1894-1919); Algernon Hyde Villiers (kia 23 November 1917 at Bourlon Wood); Arthur Purling Middleton, Alan Harrison Kidd; Evelyn Godfrey Worsley (kia 17 September 1916 on the Somme), the brother of John Fortescue Worsley (kia 27 November 1917 at Fontaine-Notre-Dame, near Cambrai); (seated): Alan Campbell Don, Anthony William Chute.

Education and professional life

Worsley attended The Evelyns Preparatory School, Colham Green, Hillingdon, Uxbridge, Middlesex, whose Headmaster was his father (1872–1931; cf. R.A. Perssé, C.A. Gold, R.P. Stanhope, F.W.T. Clerke, T.G. Rawstorne, J.F. Worsley), from c.1892 to 1898, and then Winchester College from 1898 to 1903, where he was a member of Winchester College Volunteer Rifle Corps, Head of ‘A’ House, a Commoner Prefect, and member of Sixth Book. He played cricket and football for his House, and rowed and played golf. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 19 October 1903, having been exempted from Responsions. He took the First Public Examination in the Hilary Terms of 1904 and 1905, when he was awarded a 3rd in Classics Moderations. He then read for an Honours Degree in Modern History and was awarded a 2nd in Trinity Term 1907. After taking his BA on 10 October 1907, he returned to Evelyns School to work under his father, whom he succeeded as Headmaster in 1912. During the war, in his son’s absence, Godfrey Thomas Worsley resumed his old job, and after his son’s death he wrote to President Warren, on 3 October 1916, thanking him for his “most kind” letter of condolence:

I cannot say how much we value your warm testimony to our dear Evelyn’s worth & character. He lived indeed a pure & blameless life, & he has died a noble death; and we do not [be]grudge the sacrifice. Without presumption I feel that it may be said of him ‘He being made perfect in a short time, fulfilled a long time’, and ‘His lot is among the saints’ [The Wisdom of Solomon 4:13 and 5:5]. He showed himself eminently fitted in every way for the work he had taken up, & he had an extraordinary influence, young as he was, on the parents as well as on his boys.

War service

Worsley applied to the Special Reserve of the Grenadier Guards on 20 January 1916 and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on the same day. He began his service with the Regiment in the 5th (Reserve) Battalion and was later transferred to the 3rd (Regular) Battalion, in which R.P. Stanhope, H.D. Vernon and his elder brother John Fortescue Worsley were already serving. The 3rd Battalion had landed at Le Havre on 27 July 1915 and on 20 August 1915 become part of the 2nd Guards Brigade, in the newly formed Guards Division. But Worsley was not made a probationary Second Lieutenant until 22 January 1916 and was confirmed in that rank in the following month. The Battalion spent the first six months of 1916 in and out of the line near Ypres: the routine consisted of five days in the front line, three days in Camp B cleaning up, and another five days in support in the battered town of Ypres itself. In mid-July 1916, together with the rest of the Guards Division, the 3rd Battalion began to move to the Somme, newly equipped with steel helmets. On 10 August 1916 the Guards Division began to take over trenches to the south of Hébuterne and the move was completed by 14 August. Worsley landed in France on 12 August 1916 and joined the 3rd Battalion on 27 August, when it was in billets at Morlancourt and training for the coming Battle of Flers-Courcelette in the newly prescribed techniques of open fighting, which the Battalion War Diary described as follows:

There were 3 days of Brigade Training, in which the assault was practised. The basis on which the formations were founded was that it was necessary to move all supporting troops simultaneously with those detailed for the actual assault in order to avoid the enemies’ [sic] barrage. Accordingly the Brigade was formed up in nine waves […] at 50 yards distance and at zero time all waves advanced together under cover of (1) a standing barrage on the enemies’ [sic] front line, (2) a creeping barrage starting 100 yds in front of the assault and moving forward at 50 yds per minute. When the creeping barrage reached the standing barrage, both lifted to 200 yards beyond the German front line. The leading waves passed over the front line and formed up behind the barrage. Standing barrage was then put down on to the second line. The front trench was cleared by the new waves.

On 9 September, the Battalion moved to Happy Valley, a track that led from the direction of Albert up to Bazentin-le-Petit, Mametz Wood and ultimately High Wood. It had been captured from the Germans on 14 July 1916 and was hidden from the Germans by the valley’s sides, but because they shelled it regularly, it was also known as Death Valley. On 13 September 1916 the 3rd Battalion marched to Carnoy, and at 21.00 hours on 14 September they began to march by companies via Trônes Wood and Guillemont to the assembly point behind the front line east of Ginchy, which the 3rd Battalion’s war diarist drily described as labouring “under every disadvantage except that it was not shelled by the enemy”. Ginchy, two miles south of Flers, is situated on a high plateau running northwards for 2,000 yards, and then eastwards in a long spur for nearly 4,000 yards. The village of Lesboeufs is a mile-and-a-half south of the village of Gueudecourt and stands on the northern end of the spur, with the village of Morval on its southern end. Morval is two miles from Lesboeufs, two miles north-east of Ginchy, and commands a good view in every direction. Another spur juts out from the plateau for a mile in a south-easterly direction and then falls sharply into the Combles Valley towards Falfemont Farm (see W.L. Vince): Bouleaux Wood, a mile to the west of Combles, is on the crest of the spur, with Leuze Wood in front of it and lower down. The British extreme right at Leuze Wood was 2,000 yards from Morval and in between there lay a broad, deep branch of the main valley that was overlooked by Morval and flanked at its head by the high ground east of the valley that looks down into it. The Guards Division was positioned opposite this area, with the 6th Division on its right and the 56th (1/1st London) Division on its left, and was tasked with taking Lesboeufs, an undertaking that was possible only if the two adjacent divisions were able to clear the two flanks and take Morval and Bouleaux respectively.

When the Battle of Flers-Courcelette opened on 15 September 1916, Worsley’s Battalion was the Right Front Battalion and the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards was the Left Front Battalion of the 2nd Guards Brigade, with the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards immediately behind them as the Right Support Battalion next to the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Guards as the Left Support Battalion. Each of the four Battalions was formed up in four waves, with No. 4 Company and R.P. Stanhope’s No. 3 Company in the front, and No. 2 Company and No. 1 Company behind them respectively, and a gap of 50 yards between each platoon. The attack by the Guards Division was supposed to be supported by 11 tanks, but only six arrived, and of these, two took no part in the battle, three got lost, and one ditched (see H.R. Bell, who commanded one of them). Worsley’s 3rd Battalion was in position by 03.00 hours and the men were issued with rum and sandwiches. Then, at 06.00 hours, the artillery of 6th Division fired 40 large-calibre shells, and at 06.20 hours the Guards began their attack on the two German strong-points known as the Triangle and the Serpentine under a creeping barrage. But the ground around Ginchy was “a battered mass of irregular ridges and shell-holes, which overlapped and stretched away into the early morning mist”, making it very difficult to establish a clear line of advance, especially since there were no landmarks. In contrast, the German machine-gunners had an unimpeded field of fire and the War Diary of the 3rd Battalion provides the following account of what happened next:

Our Left Front company [No. 4 Company] was met by machine-gun fire as soon as it got up & lost Captain Mackenzie [its Commanding Officer] and Mr Asquith [Lieutenant Raymond Asquith (1878–1916), the Prime Minister’s son] at once. […] The last remaining officer of the Coy also fell within 200 yds of our own trenches.

But the Right Front Company (R.P. Stanhope’s No. 3 Company) got off “much more fortunately & did not seem to lose until a considerable way out”. They managed to capture “a line of shell holes held by Germans 250 yards out” and killed everyone there, even though this simply “impaired the cohesion of the assault”, and even though their Commanding Officer and most of their officers had been killed or wounded, the survivors succeeded in taking the first objective, the Green Line, 600 yards from the starting-line. But although the intense machine-gun fire made it impossible to go further on the right of the assault, in the centre, where units had become intermingled, a mixed group from various units of the 2nd Guards Brigade pushed forward past the Green Line for 800 yards and got near the second line of German trenches, but then had to fall back to the Green Line for lack of numbers.

So by the evening of 15 September, Worsley’s 3rd Battalion held a small frontage that was to the right of the first objective and it had to fight off enemy counter-attacks throughout the night of 15/16 September. The war diarist made the following comment on the day’s events: “It appeared that Les Boeufs would have fallen into our hands without opposition or at any rate with only an ill-organized resistance if more troops could have been pushed on”, and gave the following reasons for the assault’s very limited success:

(1) the Battalion’s left flank was/appeared to be unsupported as the 1st Battalion had started behind it;

(2) its right flank was completely exposed – not least because the 6th Division failed to advance in support of the Guards Division (they had been held up by a German strong-point called The Quadrilateral);

(3) the closeness of the attacking formation and the irregularity of the assembly trenches caused the waves to become muddled up;

(4) the Brigade tended to split up to the right and the left in order to cover its exposed flanks.

The 3rd Battalion of the Grenadiers lost heavily during the day’s fighting, but 20% of its officers, Company Sergeant Majors and senior NCOs (Non-Commissioned Officers) of the Grenadiers’ 3rd Battalion had been deliberately kept in reserve for such a calamitous eventuality, and when, on 20 September, the survivors of the Battalion fell back on Carnoy, the Battalion could be reconstituted in a matter of days and moved back to Trônes Wood by 26 September.

Worsley went into the trenches for the first time during the night of 14/15 September 1915, and either because he was very new to the Battalion or because he was confused with his brother – who was at home in Britain on sick-leave from early September to early October 1916 – his name does not appear in its War Diary in connection with the attack on Flers, his first action, on the following day. Not long after the attack began, Worsley was seriously wounded less than two miles south of Flers by a rifle bullet that badly splintered his thigh. Guardsman Teague, a member of his Company who was also wounded in the attack, but far less severely, later described the circumstances as follows. Worsley was leading and cheering on his men in the Charge of the Guards during their offensive against Les Boeufs, when he and Worsley fell almost at the same moment. They managed to get into a small crater which gave them just enough shelter, even though shells continued to burst all round them. The soldier could have crawled to safety, but remained with Worsley and tended his wound as best he could from 07.00 to 19.30 hours, when the stretcher-bearers found them. During this period, Teague occasionally crawled out of the crater to get a water bottle and food from a comrade who had been killed in action. Teague was able to walk back to the British lines and survived the war, but Evelyn died, aged 31, on 17 September 1916 at No. 5 Casualty Clearing Station, Corbie, about ten miles to the south-west, without regaining consciousness after undergoing surgery.

Evelyn Worsley is buried in Corbie Communal Cemetery (Extension), Grave 2.E.5; the inscription reads “Greater love hath no man than this” (a shortened version of John 15:13; see also C.R. McClure, R.H.P. Howard, J.W. Lewis, G.B. Gilroy, R. Roberts and A. Tait-Knight). The closely packed graves may indicate that it was difficult to identify the bodies of the dead individually. H.D. Vernon was killed in action south-west of Ginchy on 15 September 1916, aged 23, and R.P. Stanhope was also killed in action south of Flers, aged 31. In late September 1916, “a very nice Memorial Service to Evelyn” took place at the school, at which “Reginald Steer[,] his old Magdalen friend”, whose brother Gordon Pemberton Steer had died on 26 December 1915 of wounds received in action near Givenchy, “gave a delightful little address.” Evelyn Worsley left £8,427 10s. 6d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Second Lieutenant Evelyn Godfrey Worsley’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,280 (23 September 1916), p. 9.

Ponsonby (1920), i, p. 343; ii, p. 107; iii, p. 242.

Rendall at al., ii (1921), p. 28 (photo).

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 52.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 100–01.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1239 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to E.G. and J.F. Worsley [1916]).

OUA: UR 2/1/52.

WO95/1219.

WO339/52793.