Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 27 January 1893

Died: 6 November 1917

Regiment: Royal Army Medical Corps attached to Royal Welsh Fusiliers

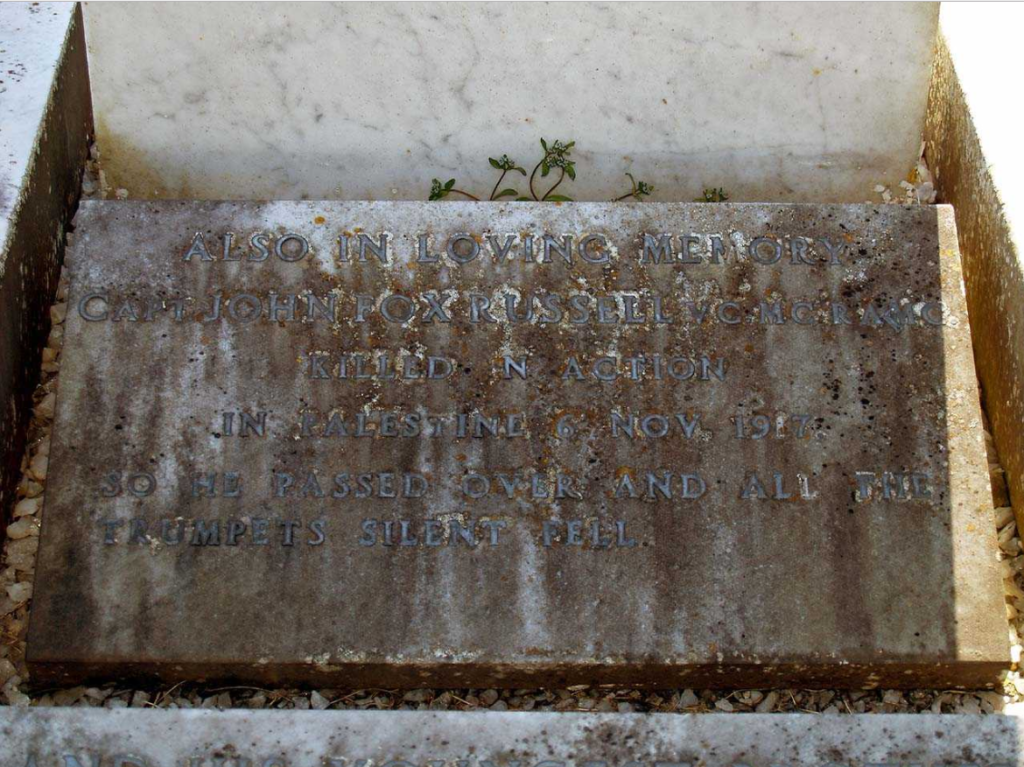

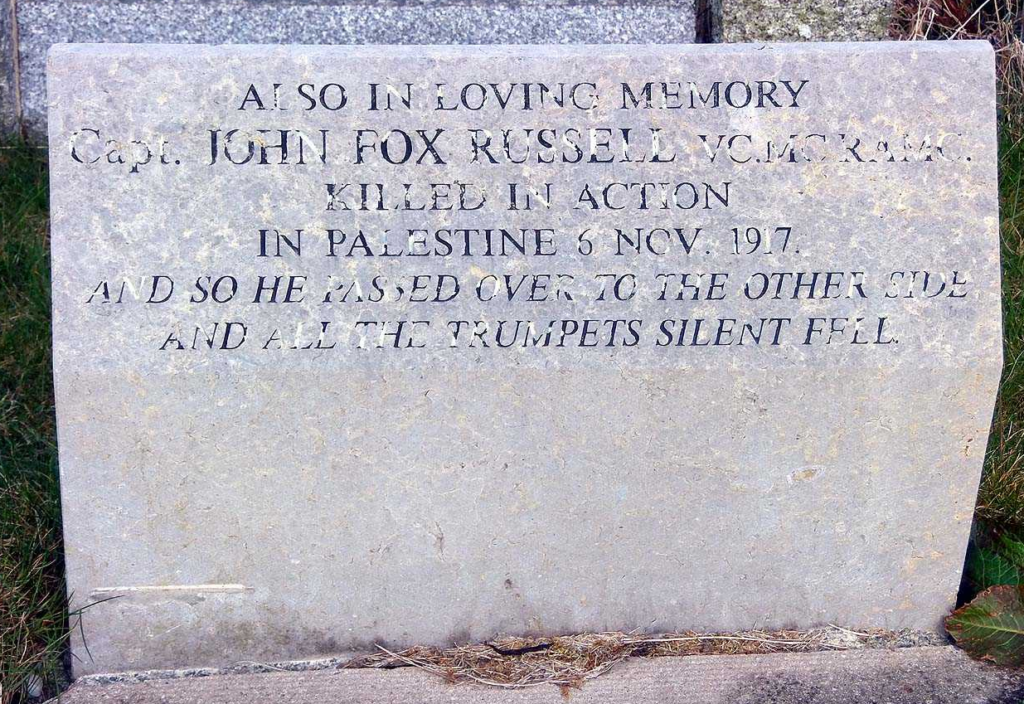

Grave/Memorial: Beersheba War Cemetery: F.31

*Magdalen’s memorial includes a ‘DSO’; but this is an error; his campaign medal card WO372/7 names him as Fox-Russell, VC, MC. A reasonable search failed to find evidence of a DSO.

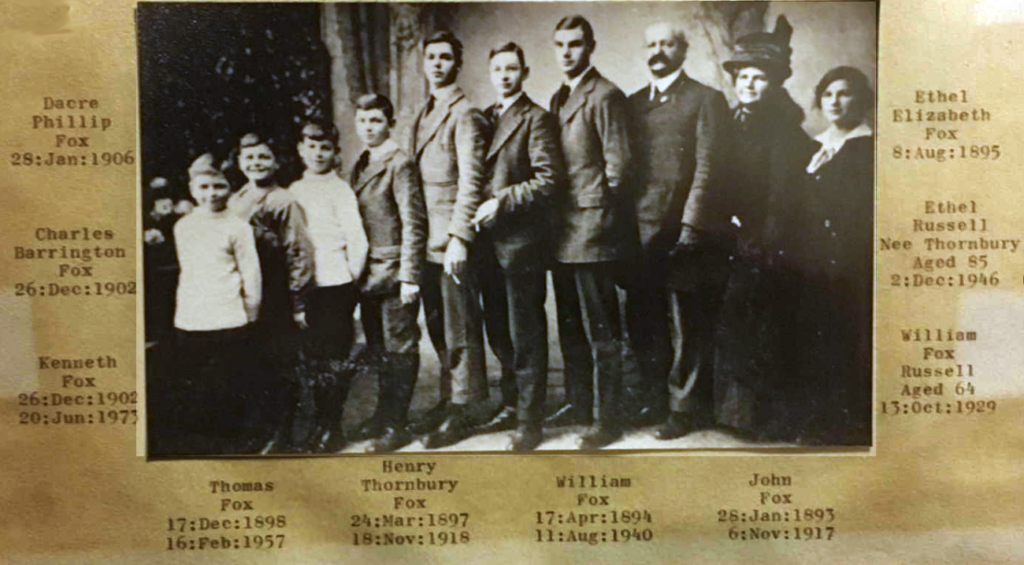

Family background

b. 27 January 1893 in Holyhead, Anglesey, as the oldest of the eight children (seven boys, one girl) of William Fox Russell (1863–1929) and Ethel Maria Fox-Russell (née Thornbury) (1861–1946) (m. 1892). At the time of the 1901 Census the family was living at 5 Victoria Terrace, Holyhead (one servant); and at the time of the 1911 Census the family was still living there together with William’s business partner (three servants). By 1929 the family had moved to Khandala, Seabourne Road, Holyhead.

Parents and antecedents

John Fox Russell’s paternal great-grandfather John Russell [I] (1792–1856) was christened in the coastal village of St Bees, Cumberland, and moved to County Limerick, Ireland, in c.1820, where he became a merchant. He lived in the townland of Edwardstown (now Lios Mothláin Beag), became a merchant, and was a JP and a Poor Law Guardian. His son John Russell [II] (1831–1901) (John Fox Russell’s grandfather) was born in Limerick, County Limerick. John Russell [II], married Elizabeth Fox (1836–1911), a farmer’s daughter, who, like her father-in-law, came from St Bees, Cumberland (now Cumbria). They had eleven children, five of whom had the name Fox. In the 1901 Census John Russell [II] described himself as a landed proprietor of Glenview, Ballyneety, County Limerick; he was also a JP. A brief note announcing his death appeared in The Warder and Dublin Mail (27 July 1901), and although it stated that ‘He was for a term High Sheriff of the County Limerick’, we can find no evidence to support this claim.

Fox Russell’s aunt Eleanor Russell (1861–1915) married (1885) Charles Ernest Heath, who was to become Major General Sir Charles Heath, KCB, CVO (1854–1936) and in 1916 Deputy Quarter-Master-General.

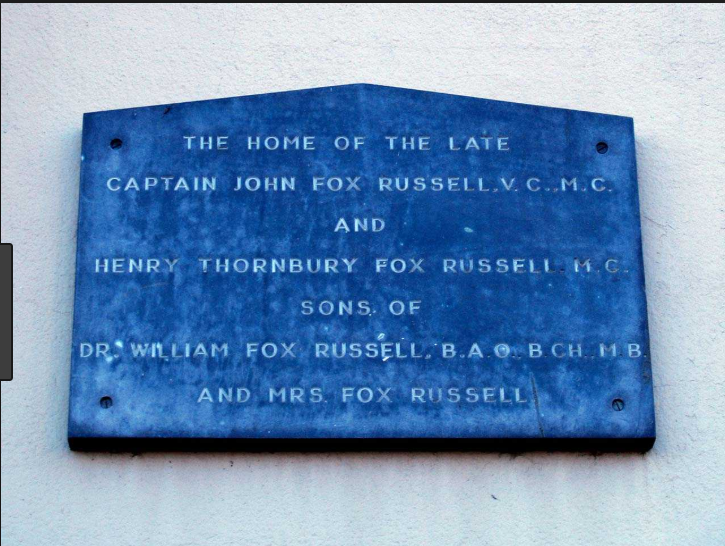

5 Victoria Terrace, Holyhead (see below). The memorial plaque is to the left of the arch.

(Courtesy of Phil Evans)

Fox Russell’s maternal grandfather, William Henry Thornbury (1836–72) was born in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, as the son of Nathaniel Henry Thornbury (1808–81), a Colonel in the 4th Bombay Native Infantry and Secretary to the Bombay Military Board. According to The Times, William Henry died on 10 September 1872 in the Diamond Fields, South Africa, but according to the probate record he died in Colesbeeg De Beirs, South Africa. There was, however, no such place, and Colesbeeg is almost certainly a misprint for Colesberg, a small town in Northern Cape Province, and De Beirs is probably an incorrect spelling of De Beers, the name of the owners of a farm where diamonds were found in 1871, which led to the South African diamond rush. A second mine was found a few hundred yards away and was initially called De Beers New Rush but eventually had the name Colesberg Kopje, which in the probate record became Colesberg De Beers, or Colesberg on the De Beers property. When the township of Kimberley was established, the name Colesberg Kopje was changed again to the Kimberley mine.

It seems that William Henry left his family in England and went to the diamond fields to make his fortune, which he may possibly have done since a description from a “colonial newspaper” is reported by Charles A. Payton in his book The Diamond Diggings of South Africa. A Personal and Practical account: “Mr. Thornbury, who has just returned from the Diamond Fields, has shown us an extraordinary stone which he has brought down with him for the purpose of sending it to England. […] The stone is supposed to be of great value.” But the Probate Calendar for 1873 lists the value of his estate as under £300.

Fox Russell’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Collins (1837–1926), was the daughter of Henry Collins (1808–83), a solicitor who was born in Cumberland and died there but spent some time in India, where Elizabeth was born in Khandala, Maharashtra, a hill station south-east of Mumbai. Khandala, it will be recalled, was the name William Fox Russell gave to the house in Holyhead into which the family moved into after his mother-in-law’s death.

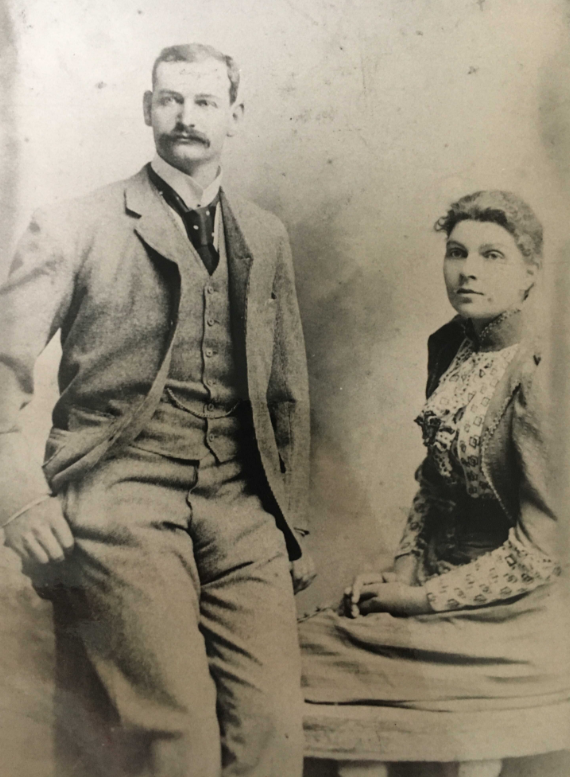

Fox Russell’s father was born in Ballyneety, County Limerick, in 1863 and in October 1882 he entered the School of Physic (since 2005 School of Medicine), Trinity College Dublin, where he was awarded his MB, BCh in 1889; he registered as a Medical Practitioner on 1 January 1890. While an undergraduate he played football for the university and was ‘one of the best walkers Ireland ever produced’. By 1892 he was in practice in Holyhead, where in April he proposed the toast “Conservative and Unionist Cause” at the annual dinner of the Holyhead Conservative Club, shortly before his marriage. He remained in Holyhead for the rest of his life, where he was active in the town’s political, social and sporting life. In May 1896 he was appointed a 2nd Lieutenant in the Volunteer Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

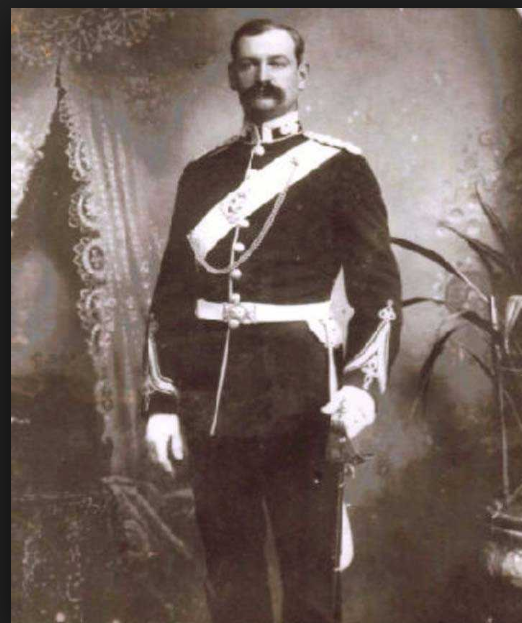

Dr William Fox Russell, Anglesey Militia Territorials c. 1907

(Courtesy of Brian Collins, R.W.F. Photos)

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) William Fox Russell (1894–1940); married (1928 in Dublin) Victoria Alice O’Moore Skelly (1896–1981); three children;

(2) Ethel Elizabeth Russell (1895–1979); married (1917) Francis Graham John Manning, DSC (1892–1981); two children;

(3) Henry Thornbury Fox Russell (1897–1918);

(4) Thomas Fox Russell (1898–1957); married (1923) Gwladys Margaret Jones (1900–2004); two children;

(5) Charles Barrington Fox Russell (1903–94); married Florence Elinor Copland (1903–87); three children;

(6) Kenneth Fox Russell (1903–73); married (1948) Rhoda Ellen Hughes (1904–1972);

(7) Dacre Phillip Fox Russell (b. 1906, d. 1988 in Victoria, Australia); married Vivian Harrison (1934 in Victoria) (1903–86); one child;

At the time of the 1911 Census William Fox Russell was an apprentice fitter with the L&NW Railway Steamship Service. He was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the Army Service Corps in September 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,902, 15 September 1914, p. 7,298), promoted Lieutenant in March 1915 (LG, no. 29,156, 7 May 1915, p. 4,412), and was sent to France in July 1915. In 1939 he was a dairy farmer on Anglesey.

Ethel Elizabeth Russell’s future husband, Francis Graham John Manning, attested on 2 September 1914 and was posted as a Private in the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment. He gave his trade as a sea officer who had served for four years with the Harrison Line of Liverpool. He was discharged on 25 August 1915 having been selected for a temporary commission as Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve. He served on the pre-Dreadnought battleship HMS Vengeance (1899–1922; broken up) and the convoy sloop (‘Q’ ship) HMS Silene (1917–21; sold), a heavily armed and specially disguised merchant ship that specialized in anti-submarine warfare. After a period of Special Service, he was promoted Lieutenant RN and awarded the DSC in 1918 (London Gazette, no. 30,536, 19 February 1918, p. 2,301) for his anti-submarine work. In 1939 he was a Master Mariner.

The 6th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers marching through Aberystwyth in 1914. The officer at the front of the column is Henry Thornbury Fox Russell.

(Courtesy of Brian Collins, R.W.F. Photos)

Henry Thornbury Fox Russell was gazetted 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th (Carnarvonshire and Anglesey) Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (London Gazette, no. 28,906, 18 September 1914, p. 7,406). The Battalion landed in Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 9 August 1915 and the Battalion War Diary reports that he was hospitalized on 28 November 1915. In December 1915 the 6th Battalion left Gallipoli to serve in the Palestine Campaign in Egypt, where Henry Thornbury was promoted Lieutenant in March 1916 (LG, no. 29,737, 6 September 1916, p. 8.781) and Captain in July 1916 (LG, no. 30,193, 20 July 1917, p. 7,418). In March 1917 he was seconded for duty with the Royal Flying Corps and on 27 December 1917 he took his aviation certificate at the Military School, Thetford, Norfolk, in a Maurice Farman biplane. On 13 February 1918 he was made a Flight Commander (LG, no. 30,550, 26 February 1918, p. 2,609) and when he was awarded the MC in the same month, the citation read as follows:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He formed one of a patrol which silenced an enemy battery. He dropped bombs on to two of the guns, silenced others with his machine gun and then engaged transport on a road. This operation was carried out under heavy fire and very difficult weather conditions. On another occasion he dropped bombs and fired 300 rounds on enemy trenches from a height of 100 feet. His machine was then hit by a shell and crashed in front of our advanced position [near Bourlon Wood]. He reached the front line, and while there saw another of our machines brought down. He went to the assistance of the pilot, who was badly wounded, extricated him under heavy fire and brought him to safety. He showed splendid courage and initiative.

(London Gazette, no. 30,780, 2 July 1918, p. 7,923)

He was then appointed as an Instructor at Hooton, near Chester, training volunteers from Canada and the USA. But on 18 November 1918, flying a Sopwith Dolphin biplane, he went into a spin at 900 feet and was killed in the subsequent crash.

Thomas Fox Russell was indentured as an apprentice in Liverpool on 4 June 1915 on the SS Malakand (1905–17; torpedoed on 20 April 1917 by U-84 off the Scilly Isles with the loss of one crew member). His first voyage was from Liverpool to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and back to Glasgow (4 June–10 October 1915) as part of a crew of 64. His daughter Pamela Fox-Russell wrote of her father:

His ship was sunk at the battle of Jutland but he survived. On another occasion he was under a gun when it was fired, making him totally blind and deaf. At Greenwich Hospital he recovered his sight and hearing in one ear and he met his brother Henry (RFC) who had an arm injury.

Although the list is probably not complete, Thomas’s name does not appear in the Directory of Jutland crews. But his Admiralty record shows that from 7 November 1916 he was a Midshipman in the Royal Navy and serving on the destroyer HMS Moy (1904–19; scrapped), and that in 1917 he was serving on HMS Hibernia, a King Edward VII Class pre-Dreadnought battleship (1906–22; scrapped), the first warship to launch an aircraft while it was underway (1912). Thomas was demobilized on 3 March 1919 and in 1920 the Board of Trade awarded him the Certificate of Competency that enabled him to serve as First Mate on foreign-going steamships; in 1923 this was followed by his Master’s certificate. During World War Two he was not sufficiently fit for active service but served as a Lieutenant RN in the Admiralty.

Charles Barrington Fox Russell at the time of the 1939 register was a farmer on Anglesey.

Kenneth Fox Russell may also have been a farmer on Anglesey.

Dacre Phillip Fox Russell left Britain for Australia in August 1926 on the ill-fated RMS Ormuz [II] (so named 1920–27; sold for scrap as the SS Dresden after hitting a rock off the Norwegian island of Bokr on 20 June 1934 and capsizing on the following day at the cost of four lives). He gave his profession as farming and settled in the state of Victoria, Australia. In February 1936 he enlisted in the Australian Militia Forces for three years but gave his occupation as Tram Conductor. In 1938 he was promoted Corporal and in February 1939 he re-enlisted for a further three years and was promoted Sergeant in October; from 19 September 1939 he was on war service. His probate record gives his occupation as retired Public Servant.

Wife

John Fox Russell married Alma Grace Isabella Tylor (b. 1894, d. 1990 in New Zealand) on 26 September 1916. On 10 October 1916 he sailed from Devonport to join his unit in the Middle East (see below) and they never saw one another again. Alma was the daughter of Alfred Edward Tylor (1855–1930), a partner in in Woods, Tylor and Brown, shipowners, and Grace Mary Tylor (née Miller) (1866–1919) (m.1891). In 1919 she married Donovan Francis Edwin Whitehouse (1895–1944) who had served during the war as a Pilot Flight Officer in the Royal Naval Air Service. They had two children. At the time of the 1939 Register the family was living in Godstone, Surrey, and Donovan was a Chartered Accountant. After his death Alma moved to New Zealand and by 1957 was on the electoral roll for Lyttleton, Canterbury. When she died in New Zealand in 1990, her name was given as Alma Thomas, indicating that she had married for a third time.

Education

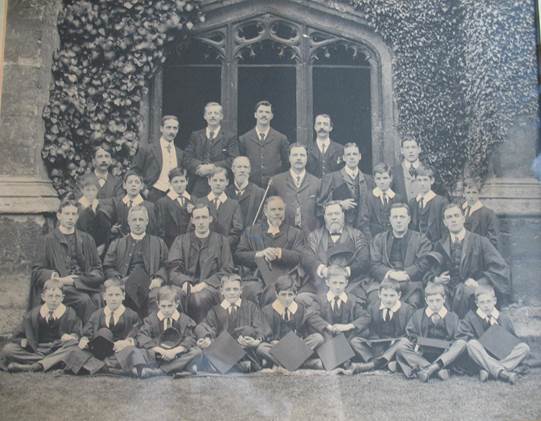

Magdalen College Choir (1907); Fox Russell is the boy standing third from the right in the third row

(Courtesy of Magdalen College School)

Fox Russell was first educated at the Thomas Ellis School in Holyhead, but in September 1904 was made a Chorister at Magdalen College School, where he was a contemporary of H. Brereton and D.H. Webb. When his voice broke he ceased to be a Chorister, left the school at the end of the summer term 1907, and went to St Bees School, where he was an enthusiastic member of the Officers’ Training Corps (Junior Division). In October 1909 he passed the Preliminary Examination in Arts that was set by the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons of Ireland and he was thereby enabled to enter a medical school. While one might have expected him to study Medicine in Dublin, it was not uncommon for students to pass the entrance examinations that were set by Irish, Scottish or Welsh bodies and then study in England. So Fox Russell decided to hyphenate his surname and register at the Middlesex Hospital, London, where he began his medical studies on 13 October, some three months before his seventeenth birthday. After gaining his Certificate of Practical Pharmacy in 1911 and his Certificate in Practical Anatomy in 1913, he returned to Holyhead in 1913 to gain experience in his father’s practice.

During his time as a student, Fox Russell became a member of London University Officers’ Training Corps (Senior Division) and rose to the rank of Cadet Sergeant in ‘D’ Section (Medical). While in Holyhead he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 6th (Carnarvonshire and Anglesey) Battalion, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (London Gazette, no. 28,792, 13 January 1914, p. 338). When war was declared he was at camp with his Battalion, and he was promoted Lieutenant on 2 September 1914 and gazetted as Temporary Captain in March 1915 (LG, no. 28,886, 1 September 1914, p. 6,910; no. 29,113, 26 March 1915, p. 2,998). Shortly afterwards he was seconded to complete his medical studies and according to the UK & Ireland Medical Directory of 1917 he obtained his MRCS (Member of the Royal College of Surgeons) Eng. and LMSSA (Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery of the Society of Apothecaries) Lond. in 1916.

War service

In April 1916 Fox Russell was transferred to the Royal Army Medical Corps and relinquished his commission with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers; he was promoted Captain on 24 October (London Gazette, no. 29,590, 19 May 1916, p. 5,059; no. 29,809, 31 October 1916, p. 10,611). At first he was posted as Medical Officer to a battery of the Royal Field Artillery, but at his own request was soon transferred to his old unit – now the 1/6th Battalion, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (RWF) – in which his brother was serving. At this time, the 1/5th, 1/6th and 1/7th Battalions of the RWF together with the 1/1st Battalion of the Herefordshire Regiment formed the 158th Brigade, part of the 53rd (Welsh) Division. After being evacuated from the Gallipoli Peninsula, the 1/6th Battalion was stationed in Egypt, where Fox Russell joined it in late October/early November 1916 at El Ferdan (Al Fardan) Camp on the west bank of the Suez Canal c.15 miles south of Kantara. Some troops from the Battalion had been involved in the Battle of Romani (3–5 August 1916) (see R.N.M. Bailey, F.R. Charlesworth, A.W. Macarthur-Onslow), some 30 miles north-east of Kantara, which had halted the westwards advance of a combined force of Ottoman and German troops towards the Suez Canal. But during November it was engaged in strengthening the defensive positions on the Canal in the El Ferdan area, and in December the Brigade started training for an advance eastwards across the Sinai Peninsula and northwards into Palestine.

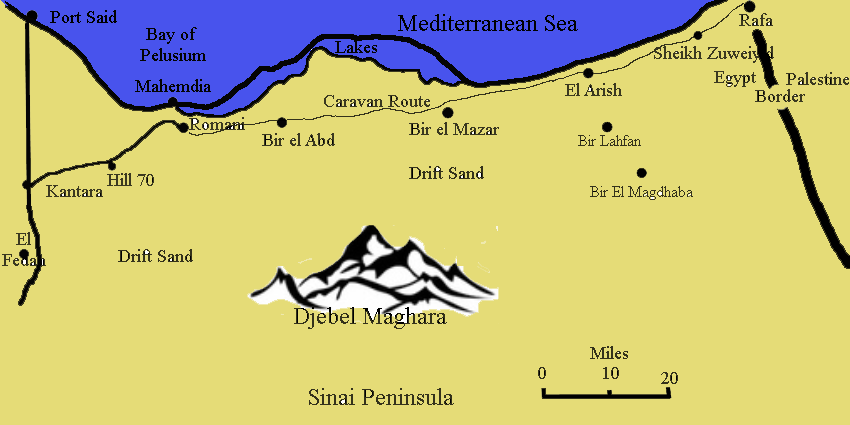

On 3 January 1917 the entire Battalion was ordered to join the rest of the 53rd Division at Romani and for the next ten weeks the 1/6th Battalion followed the successful advance of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) Mounted Brigade and the 5th Mounted Division to the Turkish defensive line which stretched some 25 miles from Beersheba in the south-east to Gaza on the Mediterranean coast, and was 20 miles north of the border between Egypt and Ottoman Palestine. On 4 January the Battalion marched to Kantara in bad weather, continued its march north-eastwards, past Hill 70 and Pelusium Station, and finally reached Mahemdia on the Mediterranean coast on 8 January, where it spent 12 days undergoing special training and laying a wire mesh over the sand in order to make its progress easier. From 21 to 23 January the 1/6th Battalion marched along the caravan route to Bir El Abd; in the last days of January it marched to Bir el Mazar and thence to El Arish, where the Battalion War Diary recorded with some pride that on no day of marching did any man fall out, although after one arduous day an officer and 13 men had been hospitalized. El Arish had been captured by the ANZAC Mounted Brigade on 20 December 1916 after the Turks had retreated to their entrenchments around Bir Lahfan in the Sinai Desert some 20 miles to the south of El Arish, where they were defeated in the Battle of Magdhaba (23 December 1916). Following a second defeat at the Battle of Rafah (9 January 1917), the Ottoman forces withdrew across the Egyptian border with Palestine and towards Gaza.

On 3 January 1917 the entire Battalion was ordered to join the rest of the 53rd Division at Romani and for the next ten weeks the 1/6th Battalion followed the successful advance of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) Mounted Brigade and the 5th Mounted Division to the Turkish defensive line which stretched some 25 miles from Beersheba in the south-east to Gaza on the Mediterranean coast, and was 20 miles north of the border between Egypt and Ottoman Palestine. On 4 January the Battalion marched to Kantara in bad weather, continued its march north-eastwards, past Hill 70 and Pelusium Station, and finally reached Mahemdia on the Mediterranean coast on 8 January, where it spent 12 days undergoing special training and laying a wire mesh over the sand in order to make its progress easier. From 21 to 23 January the 1/6th Battalion marched along the caravan route to Bir El Abd; in the last days of January it marched to Bir el Mazar and thence to El Arish, where the Battalion War Diary recorded with some pride that on no day of marching did any man fall out, although after one arduous day an officer and 13 men had been hospitalized. El Arish had been captured by the ANZAC Mounted Brigade on 20 December 1916 after the Turks had retreated to their entrenchments around Bir Lahfan in the Sinai Desert some 20 miles to the south of El Arish, where they were defeated in the Battle of Magdhaba (23 December 1916). Following a second defeat at the Battle of Rafah (9 January 1917), the Ottoman forces withdrew across the Egyptian border with Palestine and towards Gaza.

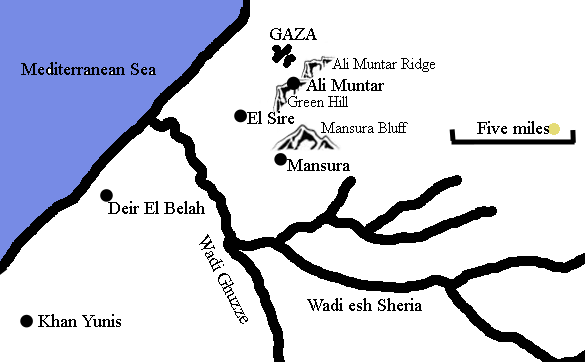

From 8 to 19 March 1917 the 1/6th Battalion continued to strengthen defences and took part in Divisional exercises. On 24 March the Battalion marched through Khan Yunis and bivouacked in a garden about a mile and a half east of the town and on the following day it moved to Deir el Belah, where the men were given a hot meal and replenished their water bottles. Early on 26 March it crossed the Wadi Ghuzze and marched to Mansurah as part of the first attack in the First Battle of Gaza (see Bailey, Charlesworth, H.F. Yeatman). But their guide got lost; the situation was not helped by the early morning fog; and the advance over ground that was both rocky and steep was tiring. The ensuing delay also meant that the Battalion was obliged to march in daylight and was spotted by the Turks.

The attack on Mansurah and the Ali Muntar Ridge began at 11.20 hours with the 1/6th battalion in support of the 1/5th Battalion. When the advancing Fusilier Battalions were 5,000 yards from their objective they came under heavy artillery fire, and at 600 yards from the Turkish trenches they were pinned down by intense rifle and machine-gun fire from the town. But when the 161st Division attacked Ali Muntar from the west the Fusilier Battalions were asked to push forward at 18.00 hours and within ten minutes had captured Green Hill on the Ali Muntar Ridge, taking five officers and 107 other ranks prisoners. Lieutenant-General Sir Charles MacPherson Dobell (1865–1954), the Commander in Chief of the Eastern Force, and Lieutenant-General Sir Philip Chetwode (later Field Marshal and the 1st Baron Chetwode) (1869–1950), the General Officer Commanding the Desert Mounted Corps, decided that if Gaza was not captured by nightfall, the fighting must stop and the forces be withdrawn. So being unaware of the success at Ali Muntar, the Allied forces, including the mounted force, some of whom had entered Gaza, were ordered to withdraw. By the next day the Turks had reinforced their position, and the First Battle of Gaza – which was so nearly a success – ended in defeat. Despite the failings of its commanders, the men of 53rd Division and 161st (Essex) Brigade had taken the well defended Ali Muntar Ridge by sheer determination and provided most of the day’s 4,000 Allied casualties, including 523 dead and c.500 missing.

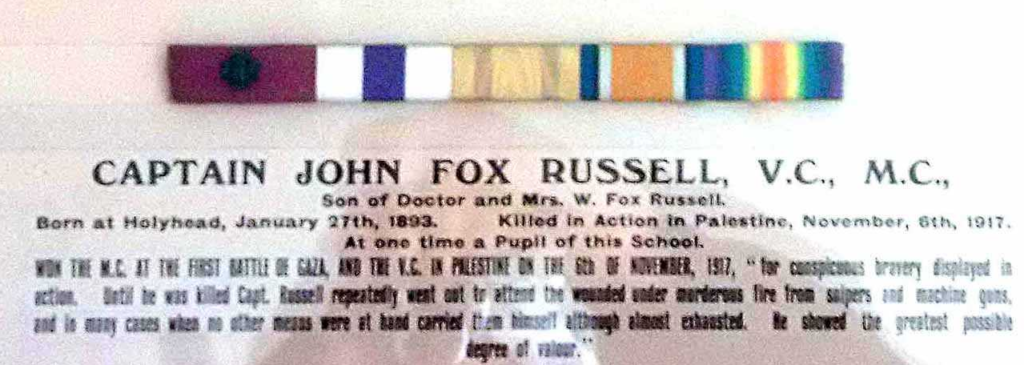

The 1/6th Battalion then bivouacked for the night behind the Mansura Bluff, but as, by 07.45 hours on the following morning, the enemy had decided to launch a counter-attack and their shelling began doing much damage to the camels and bivouacs, they moved north-east, dug in, and watched the 161st Brigade retire from Green Hill and the 6th Battalion of the Essex Regiment withdraw from El Sire. The Turkish counter-attack forced the Allies to break off battle on 28 March 1917, and retire behind the Wadi Ghuzze. Nevertheless, John Fox Russell was awarded the MC for his part in the action and his citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He showed the greatest courage and skill in collecting wounded men of all regiments, and in dressing them, under continuous shell and rifle fire” (London Gazette, no. 30,234, 14 August 1917, p. 8,382).

Having lost a third of its officers and nearly a quarter of its men as casualties, 1/6th Battalion “rested” for the first two weeks of April – undergoing training and making route marches from the defensive position in Deir El Belah. There were also regular medical inspections and John Fox Russell gave every man a cholera injection and saw to it that everyone passed through the disinfection train.

During the gap of three weeks that separated the first two Battles of Gaza, the Allies extended the new railway to Deir el Belah on the coast below Gaza, and used it to bring up eight Mk 1 tanks and 14 pieces of heavy artillery. On the other side, the Turks had reinforced their defensive positions in and around the city, widened and deepened the front-line trenches and defences, and extended their line of entrenched positions and redoubts 12 miles east of Gaza to Abu Hureira and c.18 miles south-east of Gaza towards Beersheba. General Dobell knew of the military significance of these changes and decided that his second assault on Gaza would be more like those being conducted on the Western Front in Europe. Three Infantry Divisions – the 52nd, 53rd and 54th – would make a frontal attack on the southern side of the city and this would be preceded by a heavy and systematic bombardment of the enemy positions that would include the use of eight tanks and c.350 gas shells as well as heavy-calibre shells from ships off-shore.

On 17 April 1917 the Second Battle of Gaza took place, with the 1/6th Battalion in Reserve (see Bailey, Charlesworth, Yeatman). But since the Turks had improved their defences the attack was a second failure. This led to Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Murray (1860–1945), the General Officer Commanding the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, being replaced by Lieutenant-General Sir Edmund Allenby (later Field Marshal and the 1st Viscount Allenby) (1861–1936), who had already proved his skill as a cavalry commander on the Western Front. Although the summer heat prevented much military action, John Fox Russell was kept busy dealing with septic sores, diphtheria and scarlet fever; dust that was worse than the fine sand of the Sinai Desert; lice, fleas and flies (that were repelled by crude oil-on-sacking screens); scorpions and spiders; poor and monotonous food; and poor morale that was due to no home leave for two years. To combat this, Allenby instituted rest camps by the sea, good canteen service, much entertainment, and leave to Cairo. Nevertheless, on 17 June 1917 Fox Russell became ill and was sent back to base hospital for ten days before re-joining his Battalion on 29 June.

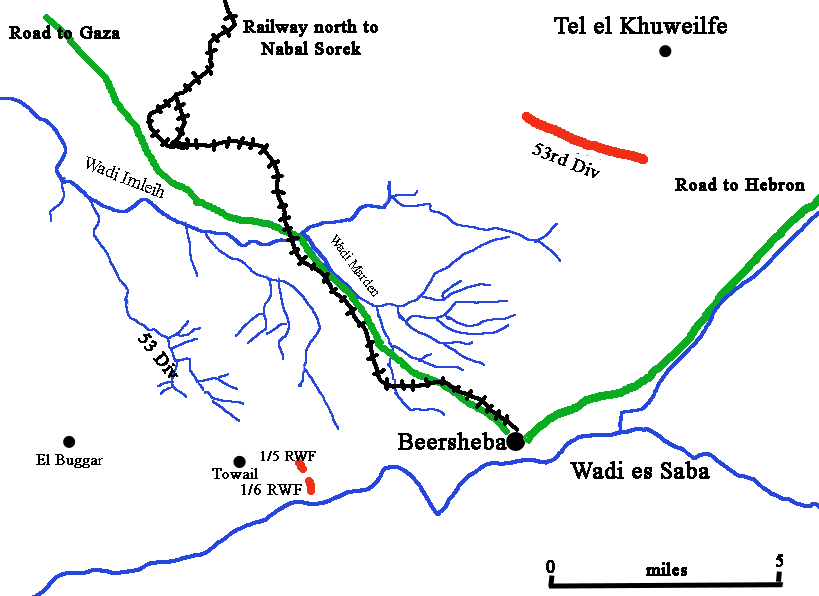

The Turks then established a strong defensive line stretching 30 miles across the coastal plain from Gaza in the west to Beersheba in the east. To the east and north of Beersheba were the Judean Hills, which separated the coastal plain from the Dead Sea valley, a region unsuitable for military manoeuvres but patrolled by the forces of both sides with occasional skirmishes. The Turkish line was higher than the territory occupied by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) – especially the redoubts at Hareira and Telaha in its centre – and this made a frontal assault both difficult and potentially costly since the attackers would have to cross several deep wadis. Beersheba, for example, was in the southern foothills of the Judaean Hills and defended from the west by the Wadi es Saba which was, in places, ten metres deep with steep banks. So in order to force the Turkish line, on 31 October 1917 the EEF attacked the two ends of the defensive line, Gaza and Beersheba, but focused its attention on Beersheba since Allenby correctly assumed that the Turks would expect the attack to make Gaza its priority. During the Battle of Beersheba (see Bailey, Charlesworth, W.H.R. Crick, T.H. Helme, Yeatman), the 53rd Division (including Fox Russell’s 1/6th Battalion) was situated west of Beersheba and south of the Beersheba–Gaza road so that it could repel a counter-attack from Hareira to the north and/or capture the Beersheba garrison if it tried to retreat to Gaza.

On 27 October the battalion was ordered to leave Deir El Balah and take up a position in support of the 1/1st Battalion of the Herefordshire Regiment. On the following day they were ordered to El Buggar to lay a cable to Towail about four miles to the east, and on 31 October they took up their positions with the 53rd Division south of the Gaza road. The attack on Beersheba, largely by the Desert Mounted Corps, was successful but part of the Turkish garrison was able to retreat northwards along the Hebron road and towards Tel el Khuweilfe. At the other end of the defensive line, units of the EEF eventually occupied Gaza on 7 November after the successful Third Battle of Gaza, which had begun on the night of 1/2 November. From 1–5 November the 1/6th Battalion took part in the pursuit of the enemy forces northwards and helped to consolidate the outpost positions that had been taken by the vanguard, and by 3 November it was close to Tel el Khuweilfe, the attack on which began with the 1/1st Battalion of the Herefordshire Regiment on the right, and the 1/6th and 1/7thBattalions of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the centre and left respectively (see Crick, Helme, Yeatman). At 04.00 hours an artillery barrage began as a prelude to further advances; at 04.20 hours the barrage became a creeping barrage, which lifted every hundred yards. The 1/6th and Herefordshire Battalion took a flat-topped hill on which nine Turkish guns were positioned; the 1/7th Battalion cleared Khuweilfe Hill but saw a mass of troops below them through the mist, and mistakenly believing them to be Turks, called in artillery fire at 05.15 hours, compelling the other two British Battalions to withdraw 200 yards. Meanwhile, taking advantage of the mist, Turkish machine-gunners worked their way around the British flank, and when the shelling stopped, the Turks advanced against the new positions from the front and right flank. Although, when the fog lifted at 07.00 hours, it was seen that all the British Battalions had achieved their objectives, the enemy machine-guns on both flanks made it necessary for them to withdraw to the second position, which they consolidated under heavy machine-gun fire and held for the rest of the day despite many casualties. The Regimental History of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers then goes on to say:

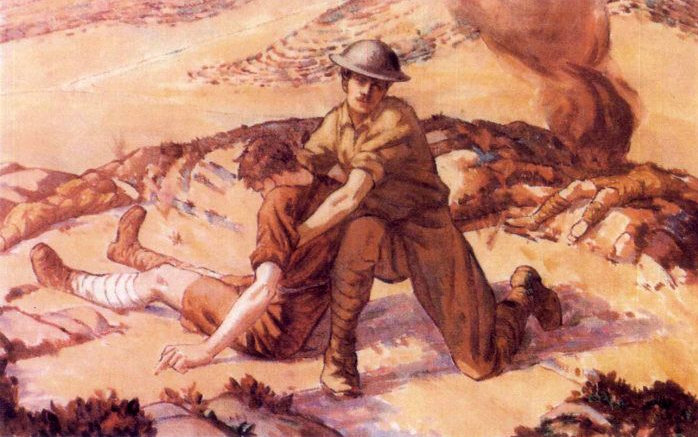

The heat of the day now fell across the battlefield. The khamsin [a hot dry wind] began to blow, and the men, whole and wounded, suffered agonies of thirst. The air was thick with clouds of flies. […] The line held by our 6th Battalion was a sketchy one, enfiladed in many places, below commanding underfeatures [sic] in others, so that the battalion was under a continual strain all day. Captain Fox Russell, the Medical Officer attached to the battalion, showed the greatest gallantry in rescuing and attending the wounded in the exposed and precarious position until he was killed.

Over 50 per cent of the officers and 30 per cent of the other ranks were killed or wounded during the action at Tel el Khuweilfe on 6 November 1917, including John Fox Russell, aged 24. For his part in the battle he was awarded the Victoria Cross, and the citation reads:

For most conspicuous bravery displayed in action until he was killed. Captain Russell repeatedly went out to attend the wounded men under murderous fire from snipers and machine-guns, and in many cases, when no other means were at hand, carried them in himself, although almost exhausted. He showed the greatest possible degree of valour. (London Gazette, no. 30,471, 8 January 1918, p. 722).

The Regimental History also included three comments on “Dr John”, or “Foxey”, as he was variously known. Captain J. Morgan wrote that:

his coolness and bravery have always been a subject of talk in a regiment in which there were many such. I remember only about three days before he was killed some shells dropped among our men; he was into the smoke and had the wounded out before many of us realised what had happened.

Company Sergeant-Major Owen Williams recorded that “he went through a hail of bullets to attend to a wounded man, and thus fell one of the noblest and best of Britain’s sons”. And Captain Revd D. Williams recalled that “on the day of the battle he worked untiringly, exposing himself to danger with the utmost abandon and self-sacrifice, in order to bring in the wounded, until at last he was struck by a machine-gun bullet”. Fox Russell was buried first in Khuweilfe Military Cemetery, Palestine (Grave A.3), but in October 1919 his body was transferred to Beersheba War Cemetery, Grave F.31 (inscription: “He gave his life for others. Greater love hath no man than this”: adapted from John 15:13); see also C.R. McClure, R.H.P. Howard, J.W. Lewis, G.B. Gilroy, R. Roberts, E.G. Worsley and A. Tait-Knight).

Beersheba War Cemetery; Grave F.31

(Courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; Photo © The War Graves Photographic Project)

Beersheba War Cemetery; Grave F.31

(Courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; Photo © The War Graves Photographic Project)

Fox Russell’s Victoria Cross is on display at the Army Medical Services Museum, Keogh Barracks, Mytchett, Surrey, and the Wellcome Library owns an extensive file of correspondence that largely concerns his two gallantry medals. In 1955, his widow – now Alma Whitehouse – wrote to the War Office from the Oxford and Cambridge University Club indicating her wish to present the medals to his old unit. When the War Office replied, it pointed out, after due expressions of gratitude, that it no longer existed, that its successor was “going out of business”, and that the presentation of his medals to the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) would be more appropriate. Alma agreed to this and was invited to their mess for the handing-over ceremony. But in a letter to General Robert Eric Barnsley (1886–1968), RAMC, her brother-in-law – Thomas Fox Russell – expressed his dismay that the medals had been presented to the RAMC and went on to say that his father had these medals, together with the MC awarded to his other son, Henry Fox Russell, displayed in a special case on his desk in his surgery. He also wrote that it was his father’s greatest wish that the medals should remain in possession of a member of the family. At a later date he relented somewhat and sent the RAMC information about his brother. In contrast, Fox Russell’s sister, Betty Manning, also wrote to General Barnsley but said how very pleased she was that her sister-in-law had “decided to give John’s cross to the RAMC”. Finally, in October 1956, Alma wrote to General Barnsley once more to say that she was very pleased with a portrait of her husband that had been painted from a photograph for the RAMC Officer’s Mess at Millbank.

John Fox Russell, painted by Howard Barron (1900–91)

(Courtesy of University College London Medical School)

The painting was later transferred to the Middlesex Hospital and a plaque under the painting reads:

These panels and arms originally surrounded the door into the old Junior Common Room. Together with the panelling of the Common Room these were a gift to the School by Middlesex graduates as a memorial to their colleagues named on the panels who gave their lives in the 1914–18 war.

With the opening of the Windover Building in 1959 the Common Room was used for other purposes and in 1979 these panels and arms together with the posthumous portrait of Captain J. Fox Russell V.C., M.C., R.A.M.C. which originally hung in the Common Room were moved to this site.

With the opening of the Windover Building in 1959 the Common Room was used for other purposes and in 1979 these panels and arms together with the posthumous portrait of Captain J. Fox Russell V.C., M.C., R.A.M.C. which originally hung in the Common Room were moved to this site.

When a painting by a Miss Pearson to commemorate John Fox Russell was unveiled on the second anniversary of his death, his father spoke and gave some details about his death:

Our son was passing a wounded lad and said to him “I will be back in a minute to tend your wound.” And the boy replied, “Dr John, do not go. There is a ‘sniper’ over there and he’ll be sure to kill you.” And here is his answer: “That man is also wounded, and to him I go, life or death.” We were proud to be parents of such a son. If the time comes and you are called on to defend your country, look at the picture of this boy and follow his example fighting for freedom and justice. (From the Welsh)

In 1975 a memorial plaque was unveiled on the outside of John Fox Russell’s old home, 5 Victoria Terrace, Holyhead, by the local MP, Cledwyn Hughes.

John Fox Russell; this may be the painting that was dedicated on the second anniversary of his death. (So far we have failed to trace this painting, which appears on several websites.)

(Courtesy of Brian Collins)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

We would particularly like to thank David Bebbington, the author of Mister Brownrigg’s Boys, which contains an essay on John Fox Russell, and Dr Roger Hutchins, who has written a brief, unpublished biography of John Fox Russell, for allowing us free use of their research, in particular for his military career.

We would also like to thank:

Andrew Fox-Russell for allowing us to use his family photographs and for sharing family information with us;

Brian Collins for allowing us to use his Royal Welsh Fusiliers photographs and Phil Evans for his photographs of Holyhead;

Deanne Attreed, Divisional Partnerships and Projects Manager at University College London Medical School for helping us find the portrait of John Fox Russell.

Printed sources:

Charles A. Payton, The Diamond Diggings of South Africa: A Personal and Practical Account (London: Horace Cox, 346 Strand, 1872).

[Anon.], ‘Medical Students’ Register: List of Medical Students Registered During the Year 1909’ (London; The General Medical Council, 1909).

[Anon.], ‘John Fox Russell L.M.S.S.A. Victoria Cross’ [Obituary], The Lancet (2 February 1918), vol. 191, no. 4,927, p. 196.

[Anon.], ‘Y Diweddar Capten Fox Russell, V.C., M.C., Cofio Arwr Yng Nghaergybi. Dadorchuddio Darlun’ [The late Captain Fox Russell, V.C, M.C., Remembering a Hero in Holyhead, Unveiling a Picture], Y Clorianydd, no. 4,269 (26 November 1919), p. 4.

C.H. Dudley Ward, History of the 53rd (Welsh) Division (Cardiff: Western Mail, 1927), pp. 17–139.

C.H. Dudley Ward, Regimental Records of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, vol. 4, 1915–18 (London: Forster, Grooms & Co., 1929), pp. 157–160.

David Bebbington, Mister Brownrigg’s Boys; Magdalen College School and the Great War (Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books, 2014), pp. 156–66.

Archival sources:

ADM 340/120/32.

Wellcome Library RAMC/801/14/22.

WO374/59795.

WO95/4626

On-line sources:

K.J. De Beer, ‘Colesberg Koppie: Kimberley Diamonds’: http://kareldebeer.blogspot.com/2009/06/colesberg-koppie-kimberley-diamonds.html (accessed 21 August 2018).

Pamela Fox-Russell, ‘My Father’s First and Second World Wars and my first’, WW2 People’s War: An archive of World War Two memories – written by the public, gathered by the BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/22/a8477922.shtml (accessed 4 September 2018).

Directory of Jutland crews, Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project: https://www.jutlandcrewlists.org/directory-of-names (accessed 4 September 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Romani’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Romani (accessed 25 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Magdhaba’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Magdhaba (accessed 25 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘First Battle of Gaza’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Battle_of_Gaza (accessed 25 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Second Battle of Gaza’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Battle_of_Gaza (accessed 28 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Third Battle of Gaza’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Battle_of_Gaza (accessed 30 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Beersheba (2017): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Beersheba_(1917): (accessed 30 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Battle of Tel el Khuweilfe’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tel_el_Khuweilfe (accessed 30 August 2018).