Fact file:

Matriculated: 1910

Born: 11 February 1893

Died: 17 June 1916

Regiment: Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

Grave/Memorial: Béthune Town Cemetery: III.K.22

Family background

b. 11 February 1893 at Alderbury, Wiltshire, three miles south-east of Salisbury, as the only child of the Hon. Robert Nicholas Hardinge (1863–1946) and Mrs Mary Hardinge (née Lynch-Blosse) (1865–1955) (m. 1892). At the time of the 1901 and 1911 Censuses, the family was living in South Lawn House, Ascott-under-Wychwood, Chipping Norton, Gloucestershire (four servants on both occasions). They later moved to Brockworth House, Gloucestershire.

Parents and antecedents

In the 1901 Census, when the family employed only four servants, Hardinge’s father described himself as a “farmer living on own means” even though he came from a very distinguished family of diplomats, colonial officials, politicians and professional soldiers.

Hardinge’s mother came from a family of Irish nobility (County Mayo) and was the only child of Sir Robert Lynch-Blosse, the 10th Baronet Lynch-Blosse.

Hardinge’s paternal great-grandfather, Henry, the 1st Viscount Hardinge of Lahore and Kings Newton (1785–1856), was a Tory politician and professional soldier who was present at Sir John Moore’s death at Corunna (1809) and would have fought at Waterloo had he not lost a hand a few days before, at the Battle of Ligny. He became Governor-General of India from 1844 to 1848 and succeeded Wellington as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army from 1852 to 1856, i.e. during the Crimean War.

Hardinge’s paternal grandfather, Charles Stewart, the 2nd Viscount Hardinge (1822–94), was a Conservative politician and married Lady Lavinia Bingham (c.1836–64), the second daughter of George Bingham, the 3rd Earl of Lucan (1800–88), who commanded the cavalry on the occasion of the Charge of the Light Brigade (1854).

Hardinge’s Uncle Charles, 1st Baron Hardinge of Penshurst (1858–1944), was a career diplomat who, despite having graduated with a 3rd in Mathematics from Cambridge, was accepted for the Foreign Office in 1880 and for ten years served in a series of relatively minor posts in Constantinople (1881–84), Berlin (1885), Washington (1885–86) and Sofia (1887–89). But over the decade his hard work, dedication, and understanding of the commercial side of a diplomatic career earned him much respect and took him to more senior posts in Constantinople (1890–92), Bucharest (1892–93), Paris (1893–96), Persia (1896–98) and St Petersburg (1898–1906). He then became a Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office and developed statesmanlike skills in the company of King Edward VII. He is credited with cementing friendly relations with France and Russia during the first decade of the twentieth century, and with being a leading exponent of anti-German feeling. From 1910 to 1916 he was the Viceroy of India, but after being badly wounded by a terrorist bomb in 1912 and losing his beloved wife to a sudden illness in 1914, he became less effective than he had been and is seen as being responsible to a considerable extent for the military disaster in Mesopotamia in 1916 (see R.P. Dunn-Pattison, J.R. Philpott). After the war, he seemed to lose touch with the new diplomatic situation in Europe, resigned his ambassadorship in Paris after two years (1920–22), went into semi-retirement, and played only a marginal role in the seismic political and diplomatic events of the next 22 years.

Education

Hardinge attended Tyttenhanger Lodge Preparatory School, Seaford, East Sussex, from c.1900 to 1907, and then Wellington College, Berkshire, from 1907 to 1910. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 18 October 1910, having passed Responsions during Hilary Term 1910. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1911 and probably re-sat one or more of the papers in October 1911. He then read for an Honours Degree in Modern History, was awarded a 3rd in Trinity Term 1914, and took his BA on 8 August 1914. While at Magdalen, he was a keen all-round sportsman, and he rode to hounds, especially with the Heythrop and Cotswold Hunts. He also decided to join the Regular Army, a profession for which he was eminently well equipped, being aggressive, unconcerned by danger and hardships, and very resilient mentally, emotionally and physically, as will emerge from his Diary and his letters from the front that are cited below. On this point, the numerous letters that his family received from friends and colleagues after his death were in complete agreement.

“Like the gallant young fellow he was, he was always trying to lead the officers and men by his fine example. His untiring efforts to see that everything was perfectly conducted relieved me of much arduous work: personally, as you know, I was very fond of him, and for one so young it was really wonderful the knowledge he had acquired in his profession. Officers and men loved him, and his gallant conduct at all times was a splendid example to all ranks.”

Military and war service

Hardinge served in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps for four years, and while still a young man was clearly identified as someone with considerable officer potential since, on 21 January 1913, i.e. a year before he graduated, he was gazetted Second Lieutenant on the Unattached List. Then, on 4 August 1914, his lieutenancy was transferred to the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Cameronians, a “famously Presbyterian Regiment” whose ORs (Other Ranks) were “the toughest of men, hard-drinking, foul-swearing, utterly loyal to the regiment” and largely “drawn from Lanarkshire coal mines and Glasgow slums”. The 1st Battalion was commanded from October 1913 to 15 June 1915 by Lieutenant-Colonel (later Major-General) Philip Rynd (“Blobs”) Robertson (1866–1936) and formed part of the 19th Brigade that was commanded by Major-General Laurence George Drummond (1861–1946). The 19th (Light) Brigade was founded in France as an Independent Brigade in August 1914 and did not become part of any Division until 12 October 1914, when it became part of the 6th Division until 31 May 1915. So during the first nine to ten months of its existence it was used as a mobile Reserve. It also included the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, the 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment.

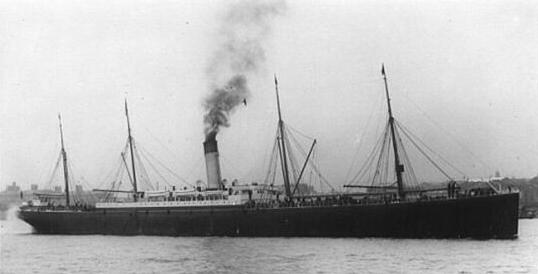

After joining his Battalion on 8 August 1914, Hardinge spent the next few days “flying to London to get uniform and flying to Oxford to take a degree”. But then, on 19 August, he took a draft of 30 men over to Nigg, near the sea on the Cromarty Firth, and waited there until 30 August, when he was put in charge of 90 men bound for Southampton and thence to St-Nazaire, at the mouth of the Loire, on the SS Armenian (1895–1915; torpedoed on 28 June 1915 by UB-24 off Trevose Head, Cornwall, with the loss of 29 lives [mainly Americans] and 1,422 mules).

From St-Nazaire, late on 4 September, Hardinge and his men sailed c.55 miles up the Loire to Nantes with a load of horses, to which most of his men were completely unused. Here, after midnight, they were landed with great difficulty and parked on a racecourse in the care of an irritated British officer who was not expecting them and had no room for them. The local French had never seen men in kilts before and were ecstatic at the sight; many of the Scottish soldiers got drunk on local wine; and Hardinge wrote in his diary that “it was all like a nightmare, but a ludicrously absurd nightmare in spite of it all, and one couldn’t help howling with laughter the whole time”. By 05.45 hours on 5 September Hardinge and his men had arrived at a rest camp near Nantes, where they found much confusion, a scarcity of tents, and men having to sleep under the skies. Nevertheless, here they stayed until 17 September, putting up with leaky billets and pouring rain, and passing the time by going on route marches. But apart from these travails, “things went very well” and the officers, who could get passes out of camp, discovered “a most attractive little café […] with the cheapest and most delicious dishes”. The weather soon worsened and the ground turned to quagmire, until at last, at 08.00 hours on 17 September, Hardinge and his detachment left Nantes by train for an unknown destination. This turned out to be the village of Septmonts, on the River Aisne and about three miles south-south-east of Soissons, and Hardinge’s name first occurred in the Battalion’s detailed and well-kept War Diary on 21 September 1914, when he formally handed over “the infernal draft” to the Cameronians’ 1st Battalion and was assigned to ‘B’ Company, commanded by Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO) Harry Hylton Lee (1877–1946).

Meanwhile, on 14 August the main body of the 1st Battalion had embarked on the SS Caledonia (1904–16; torpedoed on 4 December 1916 by UB-65 12 miles east of Malta while travelling from Salonika to Marseilles, with the loss of one life) and disembarked in Le Havre on the following day. Once he had become part of the Battalion, Hardinge heard about its 15 mph train ride to the Belgian border on 16/17 August, advance through Valenciennes to the Mons Canal (21–23 August), and experiences during the Retreat from Mons. By 03.00 hours on 24 August, when the 1st Battalion’s retreat started, it had advanced into Belgium as far as Condé on the western flank of the Mons Canal, but then, over the next 12 days, it zig-zagged back south-south-westwards via St-Quentin and Ollezy (27 August), Noyon (28 August), Carlepont, Attichy and the River Aisne (30 August), Compiègne and Lacroix-St-Ouen (31 August), Fresnoy-le-Luat (1 September), Dammartin-en-Goêle (2 September), Chanteloup-en-Brie (3 September) to Grisy-Suisnes (5 September) as part of the British rearguard. The going was hard: the Battalion marched an average of 20 miles per day, sometimes in pouring rain and sometimes on dusty, congested roads in heat that got worse as the days went on, and sometimes they had perforce to march at night, when it became intolerably cold. Proper drinking water was hard to find; rations were scarce, especially fodder for the horses, and the men frequently had to set off without sufficient sleep or a proper breakfast; their 60-pound packs were very heavy as they had to carry their own rations; their woollen Glengarry caps were excessively hot; foot problems were commonplace; and extreme fatigue among the officers meant that it was hard for them to maintain discipline. By the end of August, they were off the available maps, and Lieutenant-Colonel Robertson drily noted in the Battalion War Diary: “As we had no maps it was v difficult to carry out orders.” Moreover, the rearguard was constantly harassed by groups of Prussian light cavalry – the dreaded Uhlans – who, it was rumoured, killed prisoners out of hand, whether wounded or not, and failed to repatriate captured medical staff. Captain Ronald Hugh Waldron Rose (1880–1914; killed in action 22 October 1914, aged 34; no known grave), who had joined the Battalion in May 1900 and kept an increasingly interesting and informative Diary throughout his two months in France and Belgium, wrote on the night of 31 August, when the Battalion had reached La-Croix-St-Ouen: “No water, little food. This is trying, very trying. It soon gets cold. There is a good deal of firing. We are in reserve. Four of us huddle together to keep warm. It is very wet with dew. A miserable night with hardly any sleep. Too cold.”

Captain Ronald Hugh Waldron Rose (1880–1914)

(Historylinks Museum, Dornoch: Catalogue no. 2008.140.01)

By 4 September, the Battalion was missing 327 packs, with Captain Lee’s ‘B’ Company alone missing 73 greatcoats, 46 packs, 41 canteens, and 84 entrenching tools. Moreover, c.186 men were missing because of exhaustion, getting lost, or desertion – though by 23 September nearly 150 stragglers had managed to catch up with the main body of the Battalion. During the Retreat, the 1st Battalion was involved as a Reserve in the Battle of Le Cateau-Cambrésis (26 August), when, according to a brother officer, it had “had the narrowest of shaves of being wiped out”, and it just missed the action at Néry (1 September), where P.V. Heath was mortally wounded. Rose remarked on the evening of the action at Néry: “On the way we pass the place where the deed was done. It is a little corner of hell. They are shooting the wounded horses. The men have been moved. The road is covered with blood trails.” By 2 September, the gruelling march was seriously affecting the soldierly mien of the Battalion, and Rose recorded, with some amusement:

We are a strange-looking crowd now, men and officers unshaved. The men, who love to be as unorthodox as possible[,] have taken every opportunity. Many caps are lost, and […] comforters and caps of other units have taken their place. Equipment is extremely dirty and all kinds of odds and ends in the shape of blackened canteens, etc., are tied on. Some have their trousers cut to shorts, and some have French colours in their caps. Knives and spoons are inserted in the puttees. It is a beautiful cool morning, so I wish we could get under way. No water, so our breakfast has been dry biscuit, and about a tablespoon of tea each.

Company cooks of the Cameronians preparing breakfast during the Retreat from Mons

(Photo 2008-142-030 from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

But as the day went on the heat returned and Rose added: “Men try to eat unripe pears and apples. Anything to slack [slake?] their maddening thirst. The dust makes my throat very bad.” And on 3 September, sick and all but exhausted, Rose wrote: “The torture of the day is trying to keep awake. Feet very sore, very tired, very dirty. […] Exhaustion, depression as to the situation [in] general.”

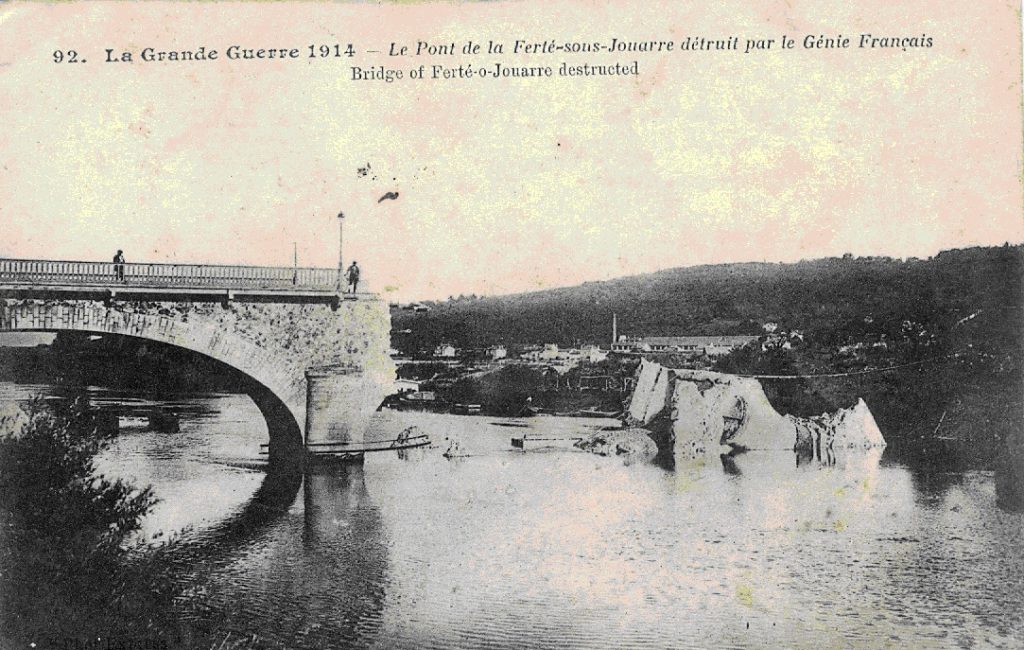

Once the Battalion had reached the southernmost limit of its retreat on the evening of 3 September, i.e. when Hardinge was waiting with his reinforcements in St Nazaire, it was allowed to rest for two days at Chanteloup-en-Brie and then, after a 14-mile night march, at Grisy-Suisnes on 5 September. But on 6 September the Battalion received a new officer and 89 ORs as reinforcements, and its tired, hungry and increasingly miserable men began to advance east-north-eastwards, through clear evidence of the Germans’ retreat, towards Jossigny, Villeneuve-St-Denis (7 September), La Haute Maison, where it formed for an attack at Pierre Levée, and the ridge at Signy Signets, where it was heavily shelled by the enemy from the north bank of the River Marne (8 September) and took casualties from the shrapnel. The Battalion finally reached La Ferté-sous-Jouarre early on 10 September and crossed the River Marne that morning via the pontoon bridge that had been constructed next to the wrecked bridge. The Battalion then marched ten miles north to Certigny and bivouacked, but its mood had improved markedly, for instead of being the quarry, it was they who were finally chasing the Germans.

The bridge at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, destroyed by French engineers to prevent the Germans from using it

Cameronians Crossing the Marne on a hastily erected pontoon bridge at La-Ferté-sous-Jouarre on 10 September 1914; the remains of the original bridge can be seen on the previous photo

(Photo [2008-142-008] from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

On 11 September, after an 11-mile march to billets in Marizy-Ste-Geneviève, Rose gave vent to an uncharacteristically vituperative outburst about his men which says much about the stress and strain from which he was suffering:

One grows to hate the soldiery, they are utterly improvident, filthy and much like beasts. They were billeted among the beasts last night. There are unrecognised heroes amongst them, men who are always cheerful and bright, but others are a constant source of irritation, and behave like monkeys, if you take your eyes off them for one minute.

By now, lice were becoming a major problem for officers and men alike and all were in need of baths and new clothing. On 12 September, the Battalion reached Buzançay and La Carrière d’Évêque, in the high ground south of the River Aisne, where it was again heavily shelled from the northern bank but where Rose was able to remove his boots for the first time in four days, only to have difficulty getting them on again. The Battalion stayed here in worsening weather for two days while c.13 miles away to the north, between Venizel on the left of the line and Bourg-et-Comin on the right, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) crossed the River Aisne. The British began their part of the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September 1914; see G.M.R. Turbutt) by advancing on the strong-point that the Germans had established at Chivres-Val, about two miles north-east of Venizel, on an escarpment that was linked to the east by minor roads, with the long ridge known as “Le Chemin des Dames”, whose eastern tip was captured by the French Army on 13 September. On 14 September Rose wrote that the Battalion had slept in a German trench, which was quite warm, but then continued: “Rain begins one of the most miserable dawns I have ever known. Feel like others depressed, suffer much from cold”; and on 15 September the Battalion followed the rest of the BEF and crossed the River Aisne at Venizel, two miles east of Soissons, in persistently heavy rain, which provoked Rose to comment: “Much rain, soaked, a night of absolute misery”.

The Battalion spent the next five days in Reserve in a large wood or forest just to the north of Venizel, from where they could hear “a fearful battle” going on not far to the north-east. The weather improved briefly on 16 September, but then more heavy rain set in for two days, lowering morale, and explaining, to some extent at least, why the British attack to the north-east had come to nothing. It was within this increasingly deadlocked situation, with troops facing each other across a gap of 80 to 100 yards without being able to move, that the Battalion was sent back across the River Aisne in boats on 19 September, having been issued, at last, with waterproof sheets that helped to keep them dry. On 21 September, the Battalion was sent to billets in the village of Septmonts, about three miles south-south-east of ruined Soissons, where it received back pay and the first ever free issue of tobacco, and where, on the same day, it was joined by Hardinge and his reinforcements – an event that was duly noted by Rose. Another 88 reinforcements arrived on 22 September, bringing the Battalion’s strength up to 27 officers and 1,136 ORs – unnecessarily, as it turned out, since the Battalion had lost only one officer and 12 ORs wounded and had suffered no fatal casualties at all since its arrival in France.

From 22 September until 5 October 1914 the Battalion stayed in billets at Septmonts, a “fairytale haven” which, according to Andrew Davidson’s wonderful account, was “embowered in a wooded valley off a treeless ridge” and offered “a tranquil sprawl of walled lanes, small cottages and bigger homes”. Here, the men used their time to rest, shave, clean up “by section in large wooden tubs” and have their lice-ridden clothes replaced or steam-cleaned, to renew their strength by means of regular meals, and to harden their muscles again by means of route marches, work on trenches and the construction of other earthworks. Rose was clearly relieved by the luxury of such a life, especially the experience of warm beds, but Hardinge, having missed the Retreat from Mons, seems to have been more than a little surprised at the kind of life that he and his men were required to live in the field, for he wrote in his Diary that between his arrival on 21 September and 5 October, he and the other men had been compelled to live the “life of a vegetable”:

In the morning we do work by Companies, either trench digging, route marching, or platoon training; in the afternoon and evening we amuse ourselves in various unsuccessful ways, such as walking out to forage for eggs, hacking on transport horses, sleeping or beating for Major [Richard] Oakley [1872–1948; Commanding Officer of ‘C’ Company, later Brigadier-General, DSO] and Capt. [Thomas Sheridan, later General Sir Thomas] Riddell-Webster [1886–1974]. We are compelled to rise every morning at 4.30 in order to stand to arms between five and six. The idea of it all is that, should we be called upon to move up to reinforce or to fall back, this is the hour when we should most likely be needed, and so, at this hour, we are to be found ready.

Lieutenant-Colonel (later Major-General) Philip Rynd Robertson (1866–1936), Mentioned in dispatches seven times, CMG, CB, KCB, Croix de Guerre (France and Belgium), Order of Leopold (Belgium), Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, The Cameronians (October 1913–June 1915) (Photo [2008-144-015] from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

Judging from the Battalion War Diary, Lieutenant-Colonel Robertson was a brusque and severe Commanding Officer, “a stickler for duty and quick to spot slacking”. But he was also a kindly, thoughtful man who “prided himself on knowing his men” and was concerned about their welfare. So when, at the end of September, Hardinge reflected on the events of the last five weeks and noted in the Battalion War Diary “1 cooker per Company would be the greatest help”, Robertson approved the comment, which was picked up by the divisional staff, who immediately acted on the report by putting out a contract for field kitchens. In early October, Hardinge began to receive news of the deaths of four of his Oxford friends during the Retreat from Mons: Heath, H.R. Inigo-Jones, W.G. Houldsworth and Geoffrey William Polson (1890–1914), an alumnus of New College who had joined the Regular Army as a University Candidate in 1913 and was killed in action, aged 23, while serving in the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Black Watch.

But on 5 October 1914, the deadlock began to come to an end, with both sides trying to advance by outflanking the other. Having waited for nightfall for the sake of concealment, the 1st Battalion of the Cameronians began to leave Septmonts at 17.00 hours in order to take part in the so-called “Race to the Sea” as the rearguard Battalion of the 19th Brigade. It then marched due south for about ten miles to St-Rémy-Blanzy, where it rested for a day before turning due west and then, on 7 October, marching for about 14 miles through the villages of Corcy, Fleury, Villers-Cotterêts and Crépy-en-Valois – which Hardinge described as “the most beautiful country imaginable” – finally reaching the village of Vez. Just near Fleury the Battalion “saw the most wonderful meteor: we all gasped in amazement: personally I looked on it as an omen”. After a day’s rest, the Battalion continued its march west-north-west – this time by daylight when it was less cold – through Béthancourt-en-Valois and Orruy, until it was allowed to bivouac for a day out of sight of aircraft in the Forest of Compiègne behind Béthisy-St-Pierre, two miles north of Néry. But during the night there were several degrees of frost and Hardinge noted in his Diary: “Am eagerly awaiting parcels from home, but they don’t arrive: woollen gloves are the most urgently needed.” On 10 October the Battalion marched seven miles to Pont-Sainte-Maxence, where it crossed the River Oise. It then turned right and marched due north for a further five miles up the long straight Roman road which is today’s D1017, until it reached the railhead at Estrées-St-Denys. Here it entrained in two groups and was taken very slowly through the night towards St-Omer, but via Amiens and the coastal town of Étaples. Hardinge commented on the military situation as follows: “Strong force of Germans endeavouring to get round the French left flank as far north as Lille and St-Omer; the only force opposed to them are French Reservists; hence our job is to go and hold them off at all costs to the last man; so it seems that we are properly in for it at last.”

Three Officers of ‘B’ Company (probably early May 1915)

Left to right: (probably) Lieutenant Pat Hardinge, Captain Harry Hylton Lee, later DSO (1856–1946), and Lieutenant Humphrey Seymour Ramsey Critchley-Salmonson (1894–1956) (gazetted Lieutenant 27 April 1915)

(Photo [2008-144-015] from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service

In the end, Hardinge’s ‘B’ Company detrained at Blendeques, three miles south-south-west of St-Omer, and marched eastwards to Renescure, about five miles along the road to Hazebrouck, where it met up with the rest of the Battalion amid rumours of Uhlan cavalry murdering children. It stayed at Renescure for a day and then, on 12 October, marched about eight miles eastwards though Hazebrouck to the village of Borre, where the officers learnt that the 19th Brigade had just become part of the 6th Division and was going to clear Bailleul, nine miles to the east. On 13 October, a day of very heavy rain, the Battalion was in Corps Reserve at Rouge Croix, three miles east of Strazeele; on 14 October it marched eleven miles to trenches near Bailleul that ran north–south for seven miles; and on 15 October, having marched a further three miles to Steenwerck, south-east of Bailleul but still inside the northern frontier of France, it tried to push forward further in the direction of Nieppe, where it was brought to a halt by heavy clashes between British cavalry and Uhlan patrols. Consequently, Hardinge’s Battalion was forced to bivouac, with loaded magazines and bayonets fixed, behind a defensive perimeter near Steenwerck for the night of 15/16 October: “Very thick mist, no blankets, no straw. None of us could sleep at all and were mostly up and about.” On 16 October, the date that marks the end of Rose’s Diary, the Battalion finally crossed into Belgium in a fleet of open-top London buses and was taken along the N331, via Nieuwkerke, Kemmel and Dikkebus to Vlamertinghe, just west of Ypres, a distance of 13 miles. It then practised movement using motor buses, “25 men per bus and went for a ten-mile joy-ride, thoroughly appreciated by the men. Rate pretty slow, about 10 miles an hour, but a considerable advance on the pace of infantry.”

During the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–22 November 1914), the Germans tried to break through to Ypres and open a route to the coast with its crucially important ports (see E.D.F. Kelly). But on the afternoon of 20 October, in much better weather, Hardinge’s Battalion was taken by bus southwards for 22 miles, along bad and crowded roads towards the ransacked village of Laventie, which was south of Armentières and now outside the battle zone. Hardinge wrote in his Diary:

Everything was all right till we got to Estaires; but there we had to halt in the village until a bridge was repaired, and unfortunately, French supply trains and large bodies of French Cavalry chose the same moment to pass through: the result was rather a block and confusion. However, the bridge being able to bear us, we went on about 8 o’clock and arrived at Laventie, our destination, about 8.20.

On 21 October the rest of the 19th Brigade caught up with the Cameronians, who had suddenly been ordered to march a few more miles southwards to Fromelles, on the south-eastern edge of the Ypres Salient, where the French were faced by the German 6th Army, commanded by the highly capable Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria (1869–1955), and in need of support. So three Battalions of the Brigade were sent into line between Fromelles and Le Maisnil, about a mile and a half further to the east, leaving the Cameronians in Reserve lying in a ditch by the roadside for fear of being targeted by German artillery. As the day wore on, the fighting at the front intensified and Hardinge found himself in the Company that had volunteered to support the Middlesex Regiment’s withdrawal from Le Maisnil. When the Cameronians were about 500 yards from the village, they came under heavy shell fire, with a good 20 shells a minute bursting in the village. So they split into platoons to enter the village while extending along the line of the road in order to support the retreat if necessary, crouching low and taking cover as best they could. But the German pressure was too great and on 22 October the three other Battalions of the 19th Brigade were forced to retreat through ‘B’ Company who, with four platoons from ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies that had been sent to help them, were ordered to hold back the Germans while trenches were dug at the crossroads at La Boutillerie, exactly half-way between Fleurbaix and the road linking Fromelles and Le Maisnil. But the Cameronians came under heavy shell and machine-gun fire, especially the four reinforcement platoons, and suffered their first fatalities. Fifteen men were killed in action, including Captain Rose (‘B’ Company), who was hit twice in the back and whose body had to be left where it lay; 37 ORs were wounded; and 20 men, including Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Macallan (c.1880–1943) (‘D’ Company) were missing, believed captured. Private Henry May (1885–1941), a weaver’s assistant from Glasgow, was later awarded the Victoria Cross for dragging Second Lieutenant (later Major-General, CB CBE DSO & Bar MC DL) Douglas Alexander Graham (1893–1971) (‘D’ Company) to safety on 22 October over 300 yards of exposed ground. During the afternoon, Major-General Drummond sent Hardinge on his first reconnaissance mission, which he accomplished satisfactorily, but when, in the late afternoon, his Battalion came under “the usual tea-time cannonade”, he decided to close his platoon “in to the left a bit”. Most of them were asleep,

and Corporal Eadie seemed very difficult to wake up. After one or two shakes, the truth occurred to me and a match struck confirmed my suspicions. His head was covered with blood: he had evidently been struck with shrapnel during the afternoon and was stone dead. This is one of the incidents that make one think when one is unused to the gentle art of war. To be perfectly frank, I have not really been very much frightened by shell fire so far; it very rarely takes one unawares, one usually hears it coming and is prepared; but bullets rather put fear into me. They make a nasty noise, like a bird singing out of tune, and you never know where you are: they are all round you. However, if taken in the right spirit, you can put up with both of them.

Then, between 18.00 and 19.00 hours, the Germans made “what seemed a pretty fierce attack all along the line, tremendous firing heard all around us; our artillery did jolly well, fairly plastered their lines of advance”. Later on the same day, Hardinge was sent out on a second reconnaissance mission during which he located isolated groups of men, without officers, fighting off the Germans, and other groups of men, some wounded, who were quite lost and without any notion of what they should be doing. Hardinge made his report, which the General found “admirable”, and then tried to make provisions for picking up these men and bringing them back.

The back of a trench showing sleeping quarters

(from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

Between 24 and 26 October, the Cameronians lost 19 men wounded and 14 men killed in action, some during a night reconnaissance raid whose aim was to establish the strength of the German positions. Hardinge was not involved but had to stay awake in order to keep an eye on its outcome, and left the following account of such an undertaking:

I must say a night attack is a terribly impressive thing; it has all kinds of beginnings; either there is a single shot breaking the silence, or a regular volley of musketry rattles out, or it may be the hammering of a machine-gun that first gives the alarm. Then developments usually follow quickly; rifle after rifle speaks in all directions: presently, too, the big guns begin to join in, for they are the most sleepless of them all, and the sky is lit up by the frequent flashes of the ensuing burst. The great thing about a night combat is the experience of the troops taking part in it. With those unaccustomed to it, the volume of fire may spread to amazing proportions for wholly insufficient reasons, for they have not the nerve necessary for waiting till the psychological moment arrives; that is, the moment when they get a real view of the enemy. Too often they fire at distant flashes or vaguely, at an enemy’s imagined whereabouts; for a night attack is a terrifying thing to the uninitiated. The firing seems to come from all around you; you cannot see clearly enough to distinguish the issue of the fight until the enemy is within rushing distance, or till his musketry ceases. But the old hand in the trenches treats a night attack with the utmost sangfroid: he reserves his fire; he does not lose his head, or send back wild reports. To confirm what I say about false alarms, I may say that two nights ago, we had a continuous rattle of musketry and deafening noise of cannon, and from reports received next day, no more than 10 Germans had been seen at all.

On 26 October, extremely bad rain turned the British trenches into a quagmire, and Hardinge recorded that he “slipped and stumbled and fell into holes going my various rounds and plastered myself with mud. Very little sleep was possible and we all felt very miserable, bedraggled objects in the morning, the sole consolation to most of us being that the Germans must have been as badly off, if not worse.” During the night of 27 October small parties of Germans made nuisance raids on the British trenches but pulled back quickly, and on 30 October Hardinge noted that unlike the situation during the Battle of the Aisne, where one Battalion held a stretch of c.300 yards, here they were expected to hold four times as much trench in far worse weather conditions. The first “really determined” German attack came after a heavy daytime artillery bombardment on the night of 30 October 1914, the day when the 7th Cavalry Brigade was vainly attempting to prevent the Germans from capturing the Zandvoorde Ridge (see Kelly). The Germans tried to rush the British trenches so that they could then break through to the north-west and into the embattled Ypres Salient, but the Cameronians responded in “the most disciplined and professional manner” (which later earned them a commendation from the GOC (General Officer Commanding)), and after the action was over, German casualties littered the wire in front of the Cameronians’ trenches.

The 1st Battalion of the Cameronians continued to hold the line at La Boutillerie until 18.00 hours on 14 November 1914, with so little happening that Hardinge wrote only seven lines in his diary between 31 October and 27 November. He commented in retrospect that he couldn’t say that much water had “passed under the bridges” during that period – even though his Battalion had suffered a good number of casualties due to sniping, minor actions and shelling that amounted to around 250 ORs and two officers killed, wounded and missing. Moreover, Hardinge proudly recorded, by 7 November 1914 the 1st Battalion had spent 16 continuous days in the trenches – and thus “beaten the record of any brigade in the British Army in any war”. From 14 to 17 November it rested in billets at Bac-St-Maur, a small town about three miles behind the front line and “dotted with textile works”. Here Hardinge was appointed his Battalion’s Mess President and Transport Officer, which meant that he had “to manage about 60 horses and 20 carts and wagons; see that the carts [were] brought up to the places ordered, and generally look after all the transport arrangements”. He noted that the job was a responsible one and took it as “a great compliment” that it had been given to him.

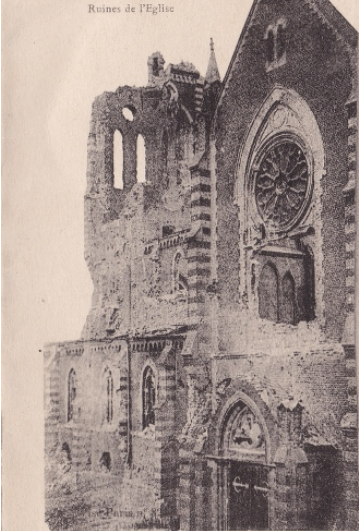

French postcard commemorating the 50 civilians killed by the Germans’ shelling of Houplines on 26 December 1914

The First Battle of Ypres officially ended on 22 November, and from 17 to 25 November and 1 to 3 December, Hardinge’s Battalion occupied verminous, fortified drainage ditches at Houplines, an eastern industrial suburb of relatively intact Armentières on the Franco-Belgian border. The foot of water which normally lined the bottoms of these hastily improvised trenches throughout the winter months was starting to freeze, and enemy snipers, equipped with excellent telescopic sights thanks to Germany’s world-class optics industry, had a clear view of them across the flat landscape from their hides in the tall factory chimneys that were scattered all over it. By now, the conditions in the trenches were appalling: there was little proper drainage or sanitation; waders had been requested but were slow in arriving; and the first cases of trench foot and frostbite were starting to appear. The Battalion War Diary commented:

Very wet – trenches in a[n] awful state. Parapets & traverses began to give way […] The men would not be able to march far as their feet & legs are swollen. They are all invested [sic] with vermin & all very dirty. Rations are brought up every evening & the men cook them in the trenches with small braziers & charcoal. Water can only be got at night & the sanitary arrangements are not easy. Buckets are now being used.

But Hardinge registered none of this in his own diary, noting instead how “well sighted” the British trenches were, “with a nice field of fire of about 200 yards” and spared from attacks by the Germans “because we have a fine wire entanglement in front”. He even found the sniping tolerable since “the place has got the reputation of being the safest spot for 30 miles!” and he did not even complain about the physical conditions during the night watches as “we have got quite a nice hut in which a capital fire is kept going and the officer of the watch usually sits in front of this, only making periodical excursions outside”. But he concluded a letter with the admission that “We sleep in shelters dug into ground and, with all our woolly caps and mufflers, look more like polar explorers than soldiers” and his diary entry ended with the observation: “We spend most of the time speculating how long [the war] is going to last and making wild bets about it.”

‘D’ Company’s line (probably Houplines, November/December 1914)

(Photo [2008-143-012] from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

From 3 to 11 December the 1st Battalion rested in billets in Houplines, and here, the War Diary informs us:

The Battalion was allot[t]ed to the 6th Divisional Baths [by the river at Pont de Nieppe, a north-western suburb of Armentières]. These baths were very well managed. 200 men went at a time. Each man handed in his shirt & underclothing & received a clean shirt &c in exchange. While he was having a hot bath his other clothes were [steam-]ironed by women – effectively killed all vermin & eggs.

On 11 December, the Battalion returned to the front line, this time to Pont Ballot, about half a mile south-west of Houplines, and stayed there until 26 December with three Companies manning the trenches and one in support to the rear: “v. wet, 18″ deep in water in some places”. On 14 December Hardinge described their return to the trenches as follows:

Back in the dear old trenches again. […] The night we came in was a most ghastly experience: the trenches were in a hopeless state, the platoon guides were such idiots that they took everyone by the longest way; I came up early to take over. H.Q. bagged our dug-out and told [Second Lieutenant Humphrey Seymour Ramsay] Critchley-Salmonson [1894–1956] to get another one dug. He thought he’d be smart and took over their telephone shelter, digging them another place for a telephone. Result: I arrived, installed our belongings in the telephone shelter. It then came on to rain and the night was pitch black and the worst night imaginable for taking over trenches. Lee had hardly arrived, very late, when H.Q. put their own servants and orderlies into the telephone place and told us to go into a small dug-out recently inhabited by two stretcher bearers. Lee was furious and so was I, almost to the extent of being insubordinate! Still, there was nothing to do but to make the best of it. The trenches were L-shaped and nobody could make out their front or where the enemy were. What a chance for the Germans to have attacked us! The next morning I received the news that every Second Lieutenant in the regiment had been promoted excepting myself, [Jacobus Darrell] Hill [1891–1973; later Major, MC] and the Rankers. Cheery! Also, it poured with rain. So, for the first time in the campaign, I wrote a depressed letter home.

In fact, on 19 November 1914, the day when the first snow fell at Houplines, Hardinge had been promoted Lieutenant with effect from 13 May 1914, but for some obscure military reason the promotion was not gazetted until 27 March 1915. After this uncharacteristic bout of low morale, Hardinge consoled himself with the bloodthirsty thought that “the order has come to us to snipe the Germans as hard as we can, so all officers are turned on to ‘observing’. This I enjoy immensely [as,] with a really good pair of glasses trained on the right spot, one can have a lot of fun.” On the following day, Hardinge described the nature of this “fun” as follows: “Had it pretty hot ‘observing’ this morning. A sniper near the three gabled house[s], I think, put in twelve shots all round. I kept moving along the trench and back again, which was just as well as he put a couple just into the spot where my head had been and about half-a-dozen made the earth fly in front of me. Finally, one whizzed by about a couple of inches from my ear.”

The Battalion’s long and monotonous stint in the trenches lasted over a month, and during it, on 23 December 1914, Hardinge was wounded: “We were looking through a periscope to spot the Germans, but unfortunately they spotted us. A German sniper was clever enough to hit the looking glass with a bullet: some of the glass cut me in the shoulder.” Although Hardinge considered the injury “trivial”, the danger of infection from anaerobic infection was ever present, and he was sent first to Lady Sarah Wilson’s hospital at Boulogne, where he began to have so much trouble with his eyes that in the end he could hardly see out of them. So after Christmas he was sent back to England, first to a hospital in Osborne House, the château on the Isle of Wight designed by Prince Albert for Queen Victoria. In a letter he wrote: “I am very comfortable here in the most palatial surroundings and an atmosphere of limousines, velvet carpets and marble baths!!” He was then allowed home on leave before being sent to Nigg, where he had spent the second half of August 1914, and he did not return to France for three and a half months.

Because of his wound, Hardinge did not participate in the attrition of the 1st Battalion by trench warfare, as a result of which, by 15 February 1915, only 305 ORs remained of those who had been mobilized on 4 August 1914, although 14 (out of 28) officers and 507 (out of 1,050) ORs survived of those who had landed at Le Havre on 15 August 1914. And even though the Battalion did not take part in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–12 March 1915), by 20 May 1915 the above two numbers had gone down from 305 to 230 and from 507 to 400 respectively. Nevertheless, within this context, the concluding note in the Battalion’s War Diary for May 1915 is very telling: “The Health of the Brigade & the Battalion has been extraordinary good. The 19th Brigade for the last 2 months have [sic] averaged about 33 men admitted to Hospital every 7 days. This is about ½ of other 6th Div[ision] Brigades.” Judging from the Adjutant’s earlier comments in the War Diary, this level of healthiness had been achieved by relatively simple means: the provision of baths every 14 days, extra supplies from home, and supplies of anti-frostbite cream.

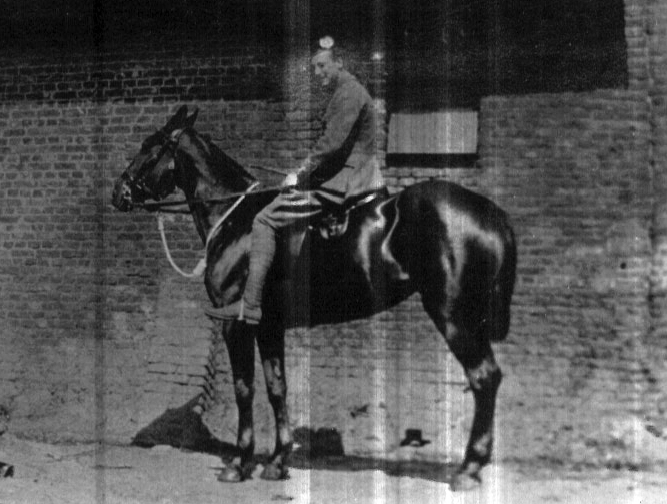

Hardinge on horseback, Armentières (18 July 1915). The horse belonged to a brother-officer, Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Francis Alexander Chetwood Hamilton, MC (1875–1956).

While recovering in Britain, Hardinge was considered ready to try his hand at commanding a Company, for he was promoted Temporary (supernumerary) Captain on 11 March 1915 (London Gazette, no. 29,263 [13 August 1915], p. 8,108); he subsequently landed at Le Havre on 12 April 1915 aboard the SS Antonia (launched as the SS Inchmarlo in 1889; captured, shelled and sunk with no loss of life as the SS Sola by UB69 on 24 October 1916, when she was 82 miles west of Bishop Rock Lighthouse en route from New York to Le Havre). On the evening of the same day, when Hardinge began writing his diary again, he arrived at Rouen in the pouring rain, left again two days later, and rejoined the 1st Battalion on 19 April, when it was in billets outside Erquinghem-Lys, just over a mile south-west of Armentières, and was assigned to ‘D’ Company, commanded by Captain Hamilton. In the afternoon, he and some friends rode into Armentières, which Hardinge thought had changed for the better: “We had tea at an excellent tea shop with lovely cakes. [When I saw it last] it was the exception, now almost the rule for shops to be open; then a few of the bolder inhabitants and an occasional Staff officer were the only people to be seen in the streets; now it has become a kind of fashionable promenade for all and every kind of officer; [it] even has a Cinema and ‘The Follies’.”

He noted the same kind of difference on 21 April, i.e. once he was “back in the dear old ditches” in the Bois Grenier-Erquinghem sector of the front line:

Before, in the dark days of November and December, we used to struggle knee deep in mud, into a channel of water, with a parapet between us and the Germans, which was continually falling in and which cost us infinite time and infinite trouble to keep in any kind of repair. Now, we follow a well beaten track, carefully marked out with white posts, which lead us to a real trench, an affair of planks and sand bags innumerable, with brick floors, deal rifle racks, and every contrivance for comfort and convenience. In fact, in contrast to what I have been accustomed to, coming into these trenches is like coming into Harrod’s Stores. Everything has become excessively scientific: instead of a muddy orderl[e]y dashing along preceded by shouts of “Gangway”, a knock is heard at the door of the mess hut and a pink paper is handed in with the message, “Fresh from the Buzzer”.

On 24 April 1915, i.e. two days after the start of the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915), Hardinge ventured the opinion that:

It is really far better being in the trenches now-a-days, excepting only for the fact that one can’t get a ride. A most beautiful communicating trench (it seems almost an insult to call it that!) leads back to Bois Grenier. At its entrance it is flanked on either side by green tubs of evergreens, and is appropriately named Shaftesbury Avenue. […] It is so broad that Riddell-Webster could get very nearly up to H.Q. on his bicycle. [Foster and I] thought we should like to see what was doing, so got up on the gunners’ hayrick to observe. You get quite a good view from the top, from the Rue du Bois on one side, round nearly to La Boutillerie on the other. The English and German trenches seem only about 20 yards apart: the German trenches are generally conspicuous owing to the very white sand bags they use (and after we have been told about concealment of trenches!!)[.] Behind the English lines one can see little black dots of men walking about, and on both sides, smoke of fires rising: now and then a shell whistles over, and bursts perhaps over a house, perhaps over a line of trenches. It is quite a Dress Circle seat in fact. I came back and had tea with ‘B’ Company. [Captain, later Lieutenant-Colonel, Harry Hylton] Lee [1856–1946; Hardinge’s old Commanding Officer in ‘B’ Company] was in great form and fed me off hard-boiled eggs and potted meat. They have a very nice mess hut with plenty of room to sit, even a box in front of the stove for their pet cat [Flamanderie Susan, “a fierce ratter”].

Three officers in Shaftesbury Avenue, the new Communication Trench. Left to right: Major Chaplin (1873–1956), Major Cecil Percival Heywood (1880–1936), Captain John Collier Stomouth-Darling (Adjutant) (1878–1916). Major Heywood was an officer in the Coldstream Guards who at the time was a General Staff Officer (GSO2) at General Headquarters; the other two were in the 1st Battalion of the Cameronians.

(Photo [2008-144-001] from the Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection, Historylinks Museum, Dornoch; Courtesy John Barnes, Esq. OBE and Mr Barrie Duncan; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

By the end of April the Germans were starting to expect an attack by the British, and on 1 May they bombarded the British support trenches near Richebourg L’Avoué for an hour and a quarter and also the nearby village of La Couture, where Hardinge’s Battalion was billeted, causing it some casualties; similar desultory shelling occurred in early May but caused only a small number of casualties.

Captain Harry Hylton Lee, later DSO (1856–1946). He is wearing a primitive gas-mask – cloth soaked in human urine (20 May 1915).

(Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum [Q 51649]; Major [later Major-General] Robert Cotton Money Collection; © South Lanarkshire Council Museums Service)

On 9 May 1915, while the Second Battle of Ypres was still raging 11 miles to the north, Hardinge’s Battalion was nearly involved in the disastrous Battle of Aubers Ridge, nine miles to the south and just past Fromelles, which took place on 9 May. It has been estimated that this futile attempt to take the Ridge and open up a route to Lille cost the British 1st Army between 412 and 458 officers and between 10,840 and 11,161 ORs killed, wounded and missing, with no ground won or tactical advantage gained, and in October 1918 the unburied dead and their uncollected military equipment were still lying about between the British and the German trenches. With hindsight, it seems that on 9 May 1915 the 6th Division was used to create a diversion. On 26 May, i.e. the day after the official end of the Second Battle of Ypres, Hardinge’s Battalion was used to support the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in the capture of a usefully situated house in no-man’s-land. At some point during May, Hardinge was put in charge of a Company and on 3 June he allowed himself to say in a letter that he thought he was “getting on pretty well” in this role because Major (later Brigadier) James Graham (“Bull”) Chaplin (1873–1956) (who took over from Lieutenant-Colonel Robertson as the 1st Battalion’s Commanding Officer on 15 June 1915) had told him during a kit inspection that he was “agreeably surprised”. Hardinge then added proudly: “Yesterday, when we had a respirator alarm, he told me we were much the best Company” – quite a compliment as Chaplin, who was a long-term professional soldier and had started his Army career in India in 1894, was on the whole not keen on volunteer officers and particularly suspicious of those from a university background. But Chaplin’s letters in The Invisible Cross (see the Bibliography below) indicate that he thought highly of Hardinge, regarded himself as his mentor, and had formed a close bond with his younger colleague, since his letters mention their every meeting. Finally, on 16 June 1915, i.e. the day after Major Chaplin had assumed command (Chaplin would not be gazetted Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel until 5 June 1916) Hardinge was finally informed that his promotion to Temporary Captain was going through – which possibly indicates that Chaplin had moved things along for him.

On 18 June 1915, probably encouraged by the “Shells/Munitions Scandal” which had broken out in Britain on 15 May because of a growing discontent with the conduct of the war, the lengthening casualty lists, and the disaster at Aubers Ridge, and had led to the fall of the Liberal Government, Hardinge made a rare criticism of the way the British organized an attack:

When the French have such an affair on, they plaster the country with shells – what they call a preliminary bombardment – for five days. Then they have a concentrated bombardment of at least five hours, and then the infantry attack. This means, instead of blowing in merely the first line trenches like we do, they smash the second line, and communication trenches too, and shatter not only the nerves of the men holding the trenches, but of their reinforcements as well.

The first half of June seems to have been a quiet time for Hardinge and his Battalion, for on 19 June he wrote to his slightly older Magdalen friend Thomas Robert Gambier-Perry (1883–1934; Magdalen 1902–06):

At the present moment I am living quite a life of peace, in a support trench with a lovely flower garden and a trench cat. The country all round looks really beautiful, and, luckily for us, we have a peace-loving type of German opposite us. I spend a good deal of my day up in a thick tree watching the German trenches through a telescope.

On about 20 June 1915, Hardinge’s Battalion moved with the rest of the 19th Brigade to a position in front of Fromelles and just north of Neuve Chapelle, where it would be on the extreme right flank of III Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir William Pulteney (1861–1941). The move was interspersed with periods in billets and by mid to late July, without much regard for secrecy, Hardinge could write in a letter that he fancied “we shall hold the line at Fromelles for quite a long time, and it’s been very quiet down there lately”. On 19 July 1915 the Battalion was in billets about three miles west of Steenwerck, just below the Belgian frontier and three miles south-east of Bailleul, when the author of its War Diary noted that “This is [the] first time since 22nd October that [the] Battalion has been out of the shelling area.” Hardinge commented:

I am lucky as ‘D’ Company has got a jolly good billet in a kind of farm house just off the road. […] The country round here is the most English-like I have yet seen in France, near Bailleul; it is quite hilly and with hop gardens. I must say I enjoy being right back from the trenches very much, and not hearing the sound of shells and machine-guns at all.

But on 23 July the Battalion went into Divisional Reserve, much nearer the front, and was allotted new accommodation near Sailly-Labourse, about four miles south-east of Béthune. On 24 July, the author of the Battalion War Diary described these billets as being “in a most disgusting & filthy condition” and Hardinge called them “a shocking bad billet, dirty and with very little room in it” – consequently, the Battalion had to spend 25 July trying to clean them up. On 31 July the Battalion was back in the nearby trenches where the sanitary arrangements were, according to the War Diary, not that much better. On 3 August patrols that went out into no-man’s-land “found dead left out after the Fromelles fight on 9 May” (the opening day of the Battle of Aubers Ridge), but so little occurred during this stint in the front line that Hardinge had little to say about it except to note that on 15 August, “A furious thunderstorm” turned the trenches “into a beastly mess.”

On 16 August 1915 the Battalion marched to billets near Le Doulieu, about three miles north of Estaires, which the War Diarist described as “v.g.”. Two days later Hardinge wrote “Well hurrah! I am a Captain at last” and on 19 August the Battalion marched back to Béthune, about nine miles to the south, in order, like the rest of 19th Brigade, to join the 2nd Division in I Corps. Hardinge described Béthune as “a much better place than Armentières: at any rate, there are very many more shops open and an excellent hairdresser, quite like a London one”. At first the Battalion became part of the Corps Reserve, but when the expected three weeks of rest did not materialize, it took up positions in the complicated trench system near Cuinchy, two miles to the east, on 25 August. Hardinge made the following entry in his Diary:

The line here is most complicated, so it has taken some time to settle down. Behind the trenches here is an absolute maze of communicating trenches, all called after London streets – Harley Street, Edgware Road, Praed Street, Conduit Street, Park Lane etc. It seems quite ridiculous, but of course it is quite invaluable as an aid to finding one’s way about, which even then is rather difficult. I got lost in the trenches last night. At the present moment I am living in the dressing station by the kindness of the Doctor in charge. I have a sort of mattress and it is quite peaceful; but rather upsetting if matters were strenuous.

On about 31 August 1915, Hardinge went on leave to his home at Brockworth House, of which he wrote during his return journey on 8 September:

You know I simply can’t believe I have had eight days leave; it seems just the glorious and very real dream of a night. It was so splendid to come home […] and everything looking so beautiful; and my room and everything just the same; and to see the hounds again. But I feel I made the best possible use of my time and enjoyed myself in a way that I shall never forget.

Just before he went on leave, Major-General Sir Sydney Lawford (1865–1953), the GOC the 41st Division – the most junior Division of Kitchener’s New Army – had tried to find Hardinge a Staff job, but the attempt failed, which Hardinge’s friends described as “very hard luck”.

During Hardinge’s leave, the Battalion had spent from 1 to 4 September 1915 in billets near Béthune and got a certain amount of its promised rest. But on 13 September it moved to Givenchy-en-Gohelle, c.11 miles to the south of Béthune and a couple of miles south of the centre of Lens, and took up positions in the nearby trenches on the following day. Then, on 24 September, the eve of what became known as the Battle of Loos (25 September–14 October 2015, the largest British offensive of 1915, involving six Divisions), Hardinge’s Battalion, together with the rest of 19th Brigade, was moved north by train despite having had no proper rest for several days, and arrived in sidings near Cambrin, about three miles east of the centre of Béthune, at 03.00 hours on 25 September. Then, having de-trained, the four Battalions of the Brigade – i.e. the 1st Battalion of the Cameronians, the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, the 1st Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders – moved in a light rain into nearby communication trenches, and waited for the cessation of the four-day-long artillery bombardment of their opponents’ trenches. The 2nd Division, which was formed from the 5th, 6th and 19th Brigades, was now positioned at the left-hand (northern) end of the Allied front line, along both sides of the La Bassée Canal (also known as the Canal d’Aire). There, additionally, it was tasked with the capture of the trenches in front of the village of Auchy-les-Mines, about a mile and a half east of Cuinchy, the focal points of which were two large craters only 60 yards away from the British parapet. These had been turned into formidable strong-points from which the Germans could enfilade the British positions on both flanks. Moreover, as Hardinge put it in a retrospective account of the Battle, the village itself was “very strongly entrenched and wired, and almost every house with a machine-gun in it”. So, after the 2nd Division had begun its unenviable task, the 9th Division, which was on the right of the 2nd Division, closer to the main focus of the whole attack, and generally considered to be “the Star Division” of Kitchener’s Army, was then to advance, swing up left, encircle Auchy-les-Mines in tandem with the 2nd Division, and advance on the village of Haisnes, about two miles below the crucial and heavily fortified town of La Bassée, from where it should have been possible to launch a break-out north-eastwards towards Lille.

Aerial view of Cuinchy showing the La Bassée Canal (Canal d’Aire), the railway running parallel to the Canal just to its south on an embankment, and the open ground to the right of the bridge. The station is just below the top right of the picture and the road across the bridge leads north to Festubert.

At 05.45 hours the waiting men of the 19th Brigade put on gas helmets because, at 06.00 hours, the British intended to release poisonous chlorine gas against the Germans for the first time in the war. But the Germans retaliated to the cessation of the British bombardment by opening up with artillery on the complex of British communication trenches, where men were queuing up to get from the railhead to their jumping-off trenches. So when, at 06.30 hours on 25 September 1915, elements of the 19th Brigade attacked the Germans across open ground that was full of craters which had been caused by mines, the men formed easy targets for well-placed machine-gun nests that were impervious to the British “cricket ball grenades” and backed by belts of uncut wire. In addition, the British deployment of poison gas – 140 tons of it compressed into 5,100 cylinders – proved to be a mixed blessing, both because of its unreliability and because of the additional warning it gave to the Germans of the imminent attack. And although, once the cylinders were turned on at 05.50 hours on 25 September, the unexpected gas badly frightened the Germans, a fickle wind blew a lot of the chlorine back towards and even onto the British positions, where it sat either in no-man’s-land or in the trenches, a situation that was worsened because, at this stage of the war, the British had only poor-quality gas-masks known as smoke helmets. Consequently, the attacking Battalions, especially the Argylls and the Middlesex in the first line, but also the Cameronians and the Royal Welch Fusiliers who were behind them in support, suffered very heavy casualties without making any gains. Although the War Diary of Hardinge’s Battalion gives no figures for the casualties incurred by the Middlesex Battalion, it records that the Argylls lost 10 officers and 452 ORs killed, wounded and missing, that the Royal Welch Fusiliers lost 6 officers and 150 ORs killed, wounded and missing, and that its own strength was reduced to 17 officers and 640 ORs. Hardinge concluded: “It seems that the attack, so far as the Argyles [sic] and Middlesex were concerned, was an utter failure”; all of which helps to explain why the above four formations barely feature in Philip Warner’s excellent account of the Battle.

Because of the slaughter of 25 September, the 19th Brigade did not take part in the renewed attacks that took place on 26 September, and on 27 September the attack that the entire 2nd Division was supposed to make on the German lines was cancelled because of the gas that still hung around the British positions. Additionally, the three or four days of absolutely incessant rain that followed 25 September turned the ground and the trenches into “a perfect sea of mud”. Nevertheless, on 27 September, in an attempt to assess the danger from any gas that lingered after an attack with gas that had begun at 16.00 hours, 40 bombing specialists from Hardinge’s Battalion and the Royal Welch Fusiliers approached the German positions to see whether they would be fired on. Thirty-two of the 40 men were killed, wounded or missing, proving the ineffectiveness of the gas attack and contributing significantly to the Battalion’s total casualties of four officers and 103 ORs who were killed, wounded or missing for the period 25 September to 2 October 1915. On the latter date, having achieved virtually nothing, the Battalion left the front line for billets in nearby Annequin; on 3 October it moved to Reserve dug-outs behind Vermelles; and on 5 October it retired to rest billets near Béthune, where it stayed until 20 October, giving Hardinge time to write up his account of the opening days of the recent Battle.

From 21 to 25 October 1915 the Battalion was back in the trenches, after which it returned to its former billets near Béthune. But on 30 October, without his departure being mentioned in the War Diary, Hardinge heard much to his chagrin that he was being transferred to his Regiment’s 10th (Service) Battalion, part of 46th Brigade in the 15th (Scottish) Division, as it was desperately short of experienced officers, having lost all but three of its original ones. Major Chaplin registered a protest, but to no avail, and on 1 November Hardinge left to join his new Battalion, which was stationed six miles away, but missed the camaraderie and professional efficiency of the 1st Battalion – not to mention his friends there – and thereafter visited it for tea and drinks whenever the two units were sufficiently near one another. The 10th Battalion, numbering 29 officers and 902 ORs, had landed at Boulogne on 11 July 1915, and on the very next day went on a route march before travelling to Audruicq by train on 13 July. The Battalion had then moved to Houchin, three miles south of Béthune, where it was in and out of the trenches until 3 September. Unfortunately, the 10th Battalion’s War Diary for September 1915 is missing, but we do know that it took part in the Battle of Loos, where the main objective of the 15th Division, in the centre of the attack, was to capture the Cité St-Auguste. Here the 10th Battalion lost 21 officers and 625 ORs killed, wounded and missing and its Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Vesey Ussher, CMG (1860–1941), was hit in the knee just after passing the first line of German trenches and had to be invalided out for several months. But unlike the 2nd Division’s attack during that engagement, the 15th Division’s attack was a partial success inasmuch as the village of Loos was captured by 08.30 hours and the strategically important Hill 70 was almost taken. Nevertheless, the Battle cost the 15th Division 152 officers and 5,849 ORs killed, wounded and missing.

From 4 to 12 October 1915 the depleted 10th Battalion was at Lillers, and from 12 to 21 October at Noeux-les-Mines before serving in the trenches opposite Vermelles from 21 October to 2 November, where it saw some action. Then, after a week away from the line at Noeux-les-Mines (2–7 November), the 10th Battalion was back in the trenches opposite Vermelles for two days, on the right of the Quarries, along Hulluch Rd (7–9 November). The War Diary records: “Attempts to put out wire in front & burying the dead occupied what time was not spent in rebuilding fallen parapets.” After two days in the support trenches (13–15 November), the 10th Battalion spent two days back in the front line (16–18 November), but in Hardinge’s view, these New Army soldiers were, for all their virtues, suffering from their inexperience and concomitant inability to look after themselves properly in the trenches. So on 22 November, while the Battalion was resting for six days at Noeux-les-Mines and Sailly-la-Bourse and Hardinge had the chance to reply to a letter from Major Chaplin’s wife Lily (1886–1956) in which she had congratulated him on his recent promotion, he seems to have been feeling thoroughly cold, miserable and lonely and wrote, in a fit of uncharacteristic dudgeon: “We are having very cold weather just at present. I am afraid I hate the 10th battn. And everything to do with it – and shall never be happy till I get back to the 1st battn.” Nevertheless, on 23 November 1915 Hardinge became the 10th Battalion’s Second-in-Command even though he was not yet promoted Major.

After a further day in the trenches at Vermelles – directly opposite the strongly fortified German defensive position known as the Hohenzollern Redoubt (26–27 November), and two additional days’ rest at Sailly-la-Bourse (28–29 November), the Battalion spent a final 12 days in the “appallingly bad” trenches (1–12 December) before travelling back northwards to Lillers by train and then marching to comfortable billets in a little mining village (13–28 December). The War Diary records: “During the previous two months little time had been spent away from the guns. It was a relief to move about open ground & to live respectably after cont[inuous] slouching in trenches for so long.” During this period, Hardinge was given eight days leave in England, after which he rejoined the 10th Battalion on 7 January 1916.

Most of the 10th Battalion’s War Diary for January 1916 is missing, but the War Diary of the 46th Brigade indicates that it was in Corps Reserve just south of Vermelles from 1 to 12 January and in Divisional Reserve near Noeux-les-Mines from 15 to 20 January. On 23 January the Battalion was able to enjoy “a most topping show”, involving some of the best variety entertainers of the time, after which Hardinge wrote in his Diary: “You can’t imagine what a lot of good a show like that does one. If only we could have it once a fortnight.” On 27 January 1916, coincidentally the date of the Kaiser’s birthday, the 46th Brigade was back in the trenches near Mazingarbe, about five miles south-east of Béthune, with Hardinge once again the temporary Commanding Officer of the 10th Battalion and now a Full Captain. Here, it was subjected to a heavy bombardment that lasted nearly four hours and particularly affected the left flank of the Brigade Sector between Vendin Alley and Posen Alley, where Hardinge’s Battalion was stationed (61 ORs killed, wounded and missing). The shelling flattened several hundred yards of trench, after which, at about 17.00 hours, the Germans mounted an assault – which was driven back by rapid fire from rifles and four well-placed machine-guns. After the engagement, the War Diary contains the following, somewhat garbled entry: “[The Divisional Commander, Major-General Sir Frederick McCracken (1859–1949)], wishes me to convey his thanks to you & your battalion, Capt. Hardinge commanding was also complimented on the work by the Brigadier – being asked if he wished to come out of the line, refused.” On 3 February, after eight days in an active part of the front line, the Battalion spent four days in advanced billets, and from 7 to 11 February Hardinge attended an artillery course at Aire-sur-la-Lys, “an extraordinary quiet, dull sort of place but nice and clean and a contrast to most of the other towns I have been in lately”, where he was billeted on the Chief Inspector of Police.

From 14 to 24 February 1916 the Battalion was occupying water-logged trenches in the Hulluch sector, to the east of Vermelles – “Frozen feet again became a prevalent ill & the conditions were very trying” – and by 3 March, after a brief rest out of line, Hardinge recorded that:

We are quite safely installed in our cellar in the outskirts of Loos[-en-Gohelle]; a place, as you know, that is very much knocked about. It is a very promising cellar […], with two velvet-seated chairs and several looking-glasses; and a very safe looking cellar too! It is funny to think one looks on a cellar now as a kind of home of luxury. I sleep on the sofa, which is very comfortable.

On 12 March 1916 the weather was warm and springlike and Hardinge commented somewhat ironically on the new system of code names that all units and formations had to use “in all telephone messages a certain distance behind the firing line”: “Our Brigade is known as Pig, and we are called Pork! The other regiments in the Brigade being called Sow, Ham and Bacon. […] Two trench mortar batteries have been called, curiously enough, Pat and Mimi.” By 14 March the Battalion had left the trenches for a week’s well-earned rest at Noeux-les-Mines, three miles due south of Béthune: “The men needed a rest badly. We had not been out of the line properly for over a month & washing was of the scantiest & [the] weather was extremely bad.” But then, on 20 March 1916, the War Diary notes: “A new spirit was agitating with the coming of spring to revive the discipline that [the] weather had eaten into & to get clean and efficient again.” And on that day the Battalion returned to the Hulluch sector for a week where “things were surprisingly quiet” because “the Enemy was too much engaged in his work at Verdun to be very active opposite us – Days passed without a shell disturbing us.” During that week, on 23 March 1916, Colonel Ussher returned to the Battalion and relieved Hardinge exactly six months after he had been wounded. On 1 April, the Battalion moved back to Cauchy-à-la-Tour, about nine miles west-south-west of Béthune, for rest and training: “Clean clothes were eventually obtained, a uniform system of wearing equipment was brought into force & the Battalion presented a different appearance from the rather mud-stained collection of beings who had been engaged [for] weary months in keeping trenches from falling in & keeping the enemy in his proper place.” On 15 April Hardinge heard for the second time that his request for a Staff job – this time as an Instructor in the 1st Army School that was currently being formed – had been turned down on the grounds that he was needed more urgently as the Second-in-Command of a Battalion – “So it doesn’t look as if I can possibly get away.”

From 24 to 30 April 1916, the 10th Battalion was back in the trenches once more, this time opposite the Hohenzollern Redoubt. It then spent about eight days in the Reserve trenches and Hardinge was given home leave for the third (and last) time. He got back to the Battalion on 9 May while it was resting at Sailly-la-Bourse, and then, on 11 May, it returned to the dug-outs at Vermelles on the left of the Hulluch Sector. Here the Germans shelled it heavily for four hours, causing a state of “chaos and darkness”, after which, in the evening, they tried to attack along the trench. Although, thanks to “the Discipline instilled with care at Cauchy” and withering defensive machine-gun fire, Hardinge’s Battalion fought off the attack, it lost two officers and 44 ORs killed, wounded and missing. From 27 May to 4 June the Battalion was withdrawn from the line before returning for its third stint opposite the Hohenzollern Redoubt, and here, on 4 June 1916, Hardinge heard that he had been awarded the Military Cross, “this tin cross of mine”, in the King’s Birthday Honours for the part he had played in the fighting of 27 January (London Gazette, no. 29,608 [2 June 1916], p. 5,573).

From 6 to 11 June 1916 Hardinge’s Battalion was in the front-line trenches, and after spending two days in Reserve, it returned to them on 14 June. But during the night of 15/16 June, Hardinge was badly wounded in the stomach by a sniper while out supervising working parties. Although the doctors thought at first that he had a chance of surviving, he died of wounds received in action, aged 23, at 06.45 hours on 17 June 1916 in No. 33 Casualty Clearing Station at Béthune, where Major Chaplin, his old CO, accompanied by Major (later Lieutenant-Colonel, DSO) Herbert Charles Hyde-Smith (1886–1956), managed to visit him. In a letter that he wrote to his wife later on the same day, Chaplin told her of Hardinge’s death and commented: “I am very sorry – he is a splendid soldier.” Hardinge’s funeral took place at Béthune on the following day.

The 10th Battalion War Diary recounts what happened to Hardinge:

On 16th [June,] Major Hardinge[,] who made it a point, ever since he took over on 22nd November 1915 the duties of second in command, to go round the line at night & see that work was being done, was shot by a sniper from Anchor Sap. Corp Walter Pollard went out to bring him in & was himself wounded. Sergt Cowan then succeeded in bringing in both Major Hardinge & Corp Pollard from where they were lying between the saps in front of Hulluch Alley. Corp Pollard was awarded the Military Medal for his gallantry in attempting to bring in Major Hardinge [London Gazette, no. 29,701 (8 August 1916), p. 7,889], Major Hardinge died of wounds in Béthune on 17.6.16, the regiment thereby losing one of its ablest officers who has shown exceptional clear judgment & gallantry when he had command of the Battalion during the enemy attack on 27th January 1916 & when, tho’ the line was battered to pieces & the regiment had lost between 1/4 & 1/5 of its effectiveness, he decided to remain in the line for the remainder of his allotted tour of 7 days & did so with success. Later he rendered valuable service in the actions of 11th May and 14/15th May.

After Hardinge’s death, Colonel Ussher wrote to his parents:

Like the gallant young fellow he was, he was always trying to lead the officers & men by his fine example. His untiring efforts to see that everything was perfectly conducted relieved me of much arduous work: personally, as you know, I was very fond of him, & for one so young it was really wonderful the knowledge he had acquired in his profession. Officers & men loved him, & his gallant conduct at all times was a splendid example to all ranks.

Brigadier (later Major-General) Torquil George Matheson (1871–1965), the GOC the 46th Brigade, echoed these sentiments, calling Hardinge “an ideal young officer, the most promising he had ever had in his Brigade” and “one of the finest leaders of men”. Many other people – friends from school and university, teachers, dons, brother-officers, his batman – wrote equally moving letters to Hardinge’s parents, with Magdalen’s Senior Tutor, Christopher Cookson, describing him as a “gentleman ‘pur sang’”. But two of the letters of condolence to Hardinge’s family are worth quoting in full. The first is from Herbert Garton, who must have heard of Hardinge’s death not long after 17 June 1916 and who would himself be killed by a sniper – near Guedecourt Wood on 15 September 1916, the first day of the Battle of Flers-Courtelette – while serving as a Captain in the 9th (Service) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own). He wrote: