Fact file:

Matriculated: 1912

Born: 22 June 1893

Died: 7 June 1917

Regiment: Worcestershire Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Lone Tree Cemetery: I.B.1

Family background

b. 22 June 1893 at “Holyrood”, 37A, St Giles, Oxford, as the only child of the Revd Charles Henry Bickerton Hudson (1861–1937) and Mrs Caroline Elizabeth Hudson (née Mills) (1866–1949) (m. 1887). The family lived at 64, St Giles, Oxford, from 1891 to 1893. In 1892 they bought Holyrood and lived there until 1919; at the time of the 1901 Census they had five people living there. By 1934 they were living at Wyke Manor, Wick-near-Pershore, Worcestershire (designed by the architect Cecil G. Hare and built in 1923–24 by Charles Henry, who was the third son of a land-owning family at Wick-near-Pershore).

Parents and antecedents

Hudson’s father was at Magdalen from 1883 to 1886, and he took his BA in 1886 and his MA in 1890. In 1886 he became Curate of St Barnabas Church, Jericho, Oxford, where he was Vicar from 1899 until 1901, when ill health forced him to retire from the ministry. St Barnabas Church had been built in 1868/69 by Thomas Combe (1796–1872), the Printer to the University, and was consecrated in 1869 by Samuel Wilberforce (1805–73), the Bishop of Oxford (1845–69), who founded Cuddesdon Theological College in 1854 as the Oxford Diocesan Seminary for preparing Oxbridge graduates for the ministry. Inspired by the Romanism of the Anglo-Catholic Tractarian Movement, St Barnabas’ architectural style resembles that of an Italian basilica; its St George’s Chapel, at the east end of the side aisle, was originally the church’s Lady Chapel, but on 25 April 1920 it was dedicated to those parishioners who had been killed in action during the Great War.

Hudson’s mother was the daughter of a Coal Master from Stourbridge, Wiltshire.

Two of Hudson’s cousins, both sons of Lieutenant-Colonel A.H. Hudson of Wick House, near Pershore, Worcestershire, died as a result of World War One. Aubrey Wells Hudson was killed in action on 22 September 1914, aged 31, while serving as a Lieutenant with the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, and Arthur Cyril Hudson was killed in action on 2 October 1916, aged 37, while serving as a Major with the 11th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment).

Education

In 1864, Gertrude Isobel Frances MacLaren (1833–96), a classical scholar and the maternal grandmother of G.W.S. Alington, established Summer Fields Preparatory School on a 70-acre site in north Oxford, where it still exists today (cf. G.W.S. Alington, G.H. Alington, A.M.F.W. Porter, E.G.R. Romanes, T.Z.D. Babington). Hudson attended Summer Fields from 1903 to 1906 and then Eton College from 1907 to 1912, where he showed himself to be “something of a runner”. He also won his football colours and became Captain of his House. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 15 October 1912, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1912. He took the First Public Examination in September and Michaelmas Term 1913, and then began to read for a Pass Degree (Group B3 [Elements of Political Economy], Trinity Term 1914) but left without taking a degree.

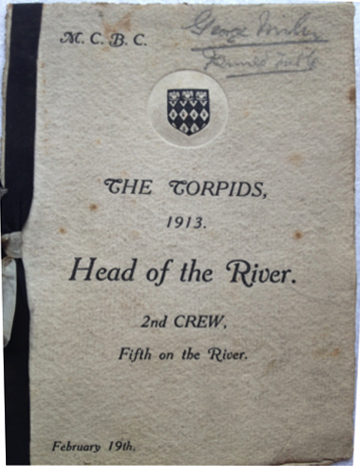

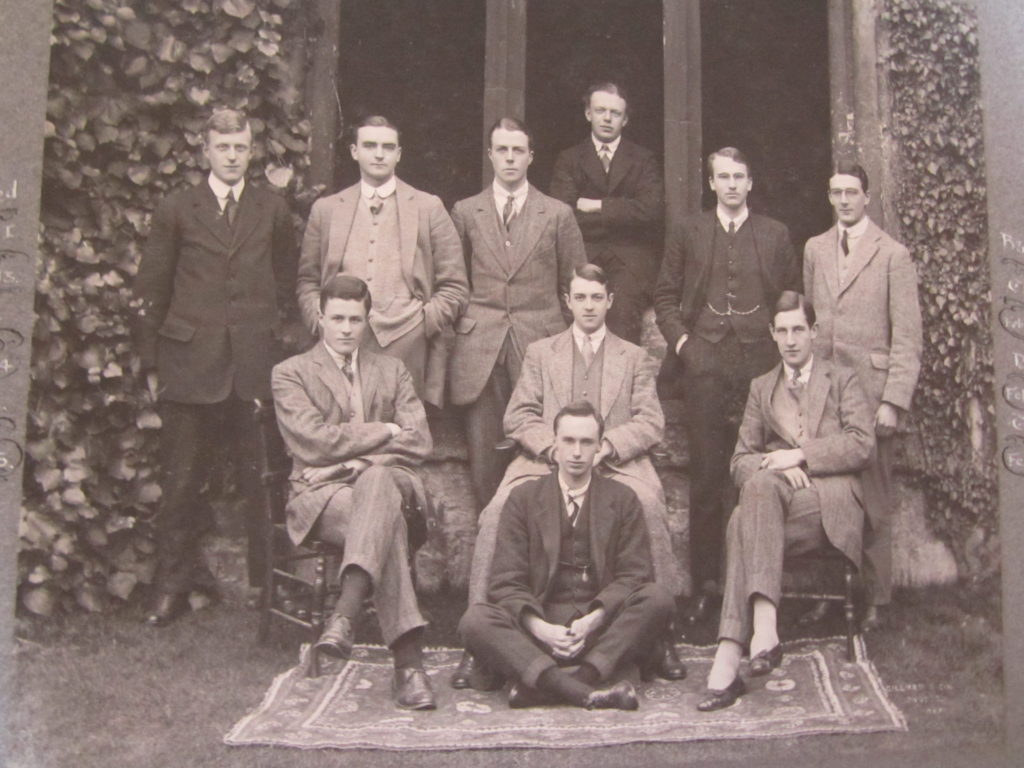

Second Torpids VIII (1913)

Cadenhead is seated on the right of the front row with his left hand over his right hand; Hudson is sitting in the centre of the second row; Lockhart is standing in the middle of the back row with his arms behind his back and his jacket tightly buttoned up.

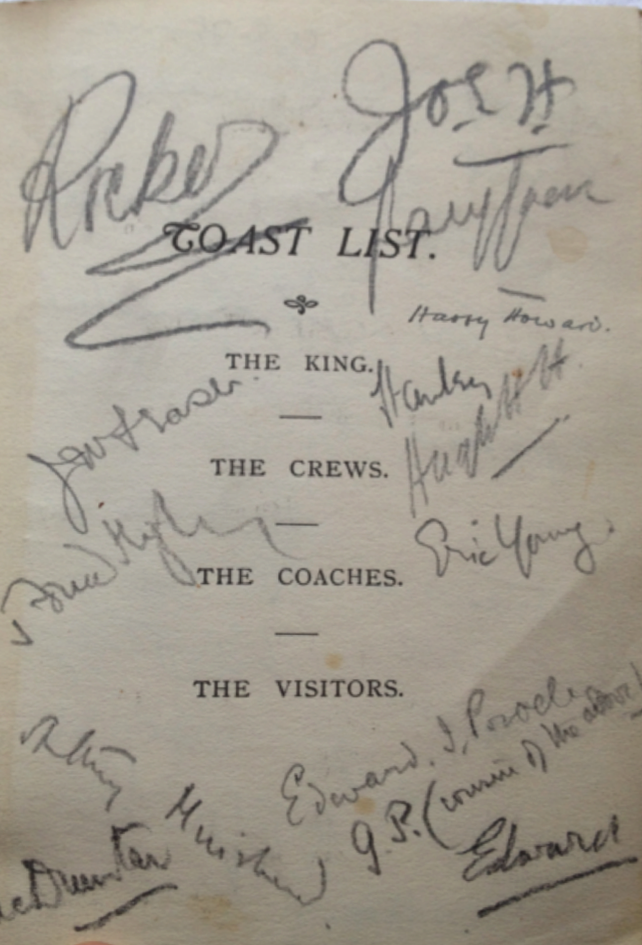

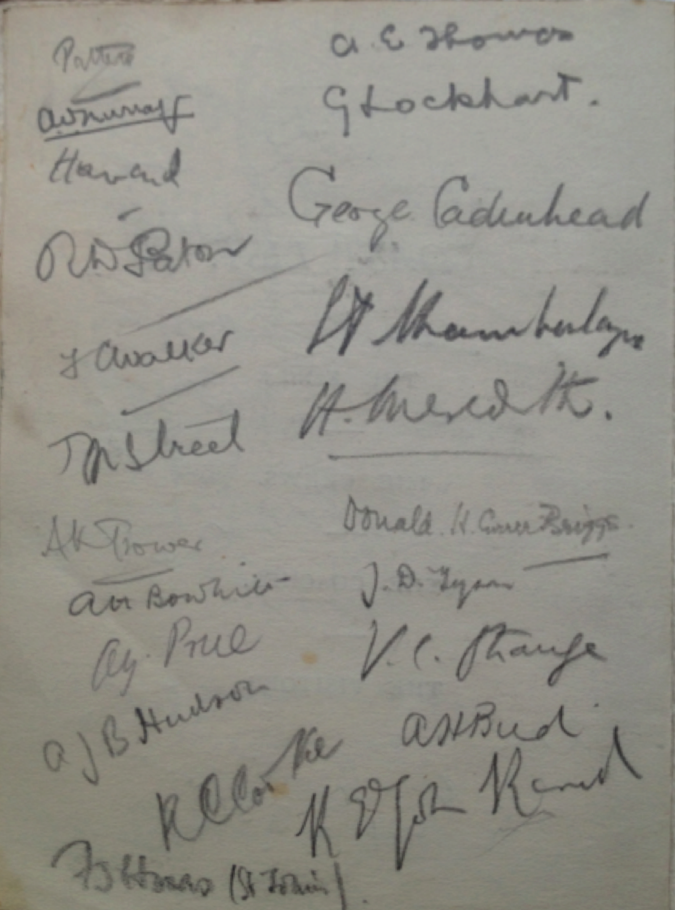

Magdalen College Boat Club menu (19 February 1913). The Prince of Wales’s signature is bottom right on the centre panel and Hudson’s is third up on the left in the right-hand panel.

(Courtesy of Ms Caroline Marsh from the papers of George Miln)

Hudson had not rowed at Eton, but took to the sport at Magdalen and made rapid improvement as an oarsman until he stroked the very successful Second Torpids VIII of February 1913. The family papers of G.G. Miln, who had rowed at no. 5 in Magdalen’s Second Torpids VIII in 1912, include a signed menu for the Dinner that was held in Magdalen on 19 February 1913 to celebrate that achievement: it had made six bumps and finished the races as the fifth placed crew in the 1st (top) Division – only four places behind Magdalen’s First VIII, which had gone Head of the River in Torpids 1913 for the second year running. It is very unusual for a Second Boat to be placed so high – and the Captain’s Book remarked: “The effort was remarkable, and their triumph over New College I very welcome.” The menu has 68 signatories, some of whom were guests from elsewhere, and they include President Warren, “Edward” – i.e. the Prince of Wales – and his Tutor Henry Peter Hansell (1863–1935). But of the c.60 junior members of Magdalen who signed the menu, 12 would be killed in action. As well as Hudson, these were: Miln himself; R.H.P. Howard; G. Cadenhead, who had rowed at no. 2 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913; K.J. Campbell, who had stroked the First Torpids VIII of 1913; J.R. Platt; R.H. Hine-Haycock, who had rowed at no. 6 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912; W.L. Vince, who had rowed at no. 7 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1912 and at Bow in the First Torpids VIII of 1913; F.C. Walker; E.I. Powell; E.T. Young; and G.B. Lockhart, who had rowed at no. 5 in the Second Torpids VIII of 1913. One of the attendees, J.D. Tyson, would be captured as a prisoner of war at Passchendaele in 1918 and was the brother of a 13th Magdalen man killed in action – A.B. Tyson – who did not attend the dinner. Another of the signatories, Albert Victor Murray (1890–1967), a close friend of Kenneth Campbell and K.C. Goodyear, who did not attend the dinner either, would be imprisoned during the war as a Conscientious Objector, albeit for one night only.

In 1914, Hudson stroked the College VIII. President Warren wrote of him posthumously:

Graceful and engaging in figure and mien, he was a most amiable and attractive character. A certain pleasing and modest youthfulness, and his eagerness for rowing, a little retarded his intellectual gifts, but he had underneath both good wits and good sense, and had he been spared he would, without doubt, have done much more service and credit to his College, and later been of true value in the wide world, as he was at Eton, and at Oxford in his brief time here. For as his last days showed, his was no shallow nature, but one deeply and solidly anchored.

Military and war service

Hudson was 5 foot 10 inches tall, and had spent two years in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps. So he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 11th (Service) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment on 4 November 1914 and promoted Lieutenant on 1 July 1915. The 11th Battalion had been formed in Worcester in September 1914 and, with Hudson as a subaltern in ‘A’ Company, landed at Boulogne during the night of 21/22 September 1915 as part of 78th Brigade, 26th Division. After training in the Somme Valley, well to the south of the fighting around Lens and Loos, the relatively inexperienced Battalion spent the period from 23 October to 9 November 1915 undergoing further training at Vaux-en-Amienois, five miles north of Amiens. But around 21 October 1915, Hudson contracted acute rheumatic fever, an event that is not recorded in the War Diary, and spent one month in hospitals in France and a further three months in various hospitals in England, one of which was the 3rd Southern General Hospital in Oxford. On 26 February 1916, a Medical Board that convened at the headquarters of the Royal Engineers, in Wareham, Dorset, declared Hudson, despite acute rheumatic symptoms, to be fit for general service at home, and he was attached to the 12th (Reserve) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment, which was stationed locally. A month later, on 21 March 1916, another Medical Board that convened at Wareham declared him completely fit for general service, and on 3 April 1916 he received orders to prepare to embark for the Middle East – which he did on 23 April 1916.

Meanwhile, on 11 November 1915, the 11th Battalion had already travelled to Marseilles and embarked for Salonika, in North-Eastern Greece, on HMS Magnificent (1894–1921; scrapped) and HMS Mars (1896–1921; scrapped), two converted Majestic-class pre-Dreadnought battleships. Following the 10th (Irish) Division (which had seen action around Suvla Bay, at the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, and arrived in Salonika between 5 and 10 October) and the 22nd Division (which had arrived in Salonika earlier in November), Hudson’s Battalion, still part of 26th Division, disembarked in Greece on 24 and 25 November 1915.

Here it became part of the Anglo-French force that was commanded by the French General Maurice Sarrail (1856–1929). The Allies had decided to send this force to the Balkans belatedly, after Austria-Hungary and Germany had invaded Serbia on 5 October and decisively defeated the

Serbs four days later. Pressure to send more military assistance increased when Bulgaria mobilized, joined in against the Serbs and Macedonians on 11 October, and took Skopje, Macedonia’s capital, ten days later. French forces then moved northwards to help the Serbs and Macedonians, but by 24 October, the Bulgarians had driven a wedge between them and the Serbs and on 5 November they captured the key railway junction of Niš, on the strategically important Berlin–Constantinople–Baghdad Railway. In late November 1915, the French, supported as far as the Greco-Macedonian frontier by the British 10th (Irish) Division, advanced northwards once more up the valley of the River Vardar towards Veleš and Skopje. But the Bulgarians forced them back southwards, and on 7–8 December 1915 the British 10th Division helped the French to escape by fighting a rearguard action at Kosturino, to the north of Lake Doiran, which is bisected by the Greco-Macedonian frontier and situated within the Vardar Valley 60 miles to the north of Salonika. Then, because of the defeat of the Serbs and Macedonians and the consequent threat of a Bulgarian invasion, the Allied task force, whose central base was at Lembert Camp in the northern suburbs of Salonika, spent the next few weeks, in the incessant rain and harsh cold of a Balkan winter, constructing an extensive ring of defensive trenches and bastions around that city to a depth of about 7–8 miles. But just as the British were forbidden to cross the Greco-Macedonian frontier, so were the Bulgarians, who dug in on their side of the dividing line, and an eight-month period of stalemate ensued which lasted until 17 August 1916, when 18,000 Bulgarians, stiffened by one German Division, captured Florina in northern Greece.

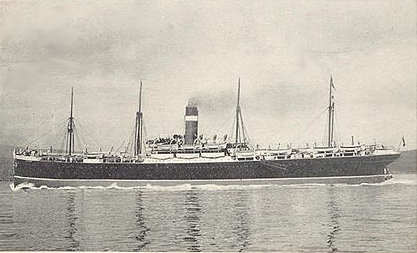

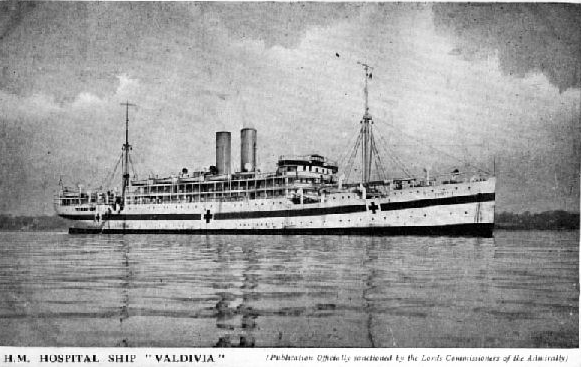

During this period, the Allied Force on the Salonika Front was gradually bolstered by the 26th and 27th British Divisions, fresh contingents from France and its colonies, and 125,000 Serbians from Corfu until it numbered more than a quarter of a million men. But the 11th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment either stayed within the Salonika defences, or trained for a summer advance across the border, or rested in Divisional Reserve (April/May 1916), or trained and patrolled in such inhospitable parts of northern Greece as the Pirnar Valley (June 1916). It was in this context that Hudson rejoined his Battalion: he travelled first to Alexandria, where, on 12 May 1916, he embarked on the SS Ionian (1901–17; on 20 October 1917 she struck a mine that had been laid by the UC-51 when she was two miles west of St Govan’s Head, Pembrokeshire, while en route from Milford Haven to Plymouth, and sank with the loss of seven lives) (cf. B.R.H. Carter), and he disembarked at Salonika on 17 May 1916. He served with his Battalion until 5 July 1916, when he was diagnosed with rheumatism and pericarditis, since his symptoms involved shortness of breath, precardial pains, and an inability to stand any strain. So he was given three months’ sick leave at home and on 8 July 1916 he left Salonika on HMHS Valdivia (1911–33; scrapped), a French passenger ship that had been lent to the British Admiralty for use as a Hospital Ship (1915–19).

Hudson arrived back in England on 22 July 1916, where, on 4 August 1916, a Medical Board that had convened at the 3rd Southern General Hospital, Oxford, concluded that the rheumatic fever had returned and gave him another eight weeks’ sick leave, which he spent at home. But on 29 September 1916, when the leave period was nearly at an end, a second Medical Board at Oxford considered him capable of eight weeks of light duty in England even though he was still suffering from rheumatism in the shoulder and shortness of breath and exhaustion after long walks. So on 2 October 1916, Hudson joined the 5th (Reserve) Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment at Fort Tregarthe, Antony, Cornwall, where he was given light duties. But three weeks later a memo dated Devonport, 23 October 1916, stated:

Last week [Hudson] was taking a gas course at Salisbury & was exposed to the effects of the chemical last Thursday. He was sick all that evening & travelled to Devonport next day & was sick during the railway journey. At Whitesand Bay Hotel next day he was there with a party & while playing the piano felt faint and giddy & was put to bed & remained there last night & the Colonel brought him here on the 22nd.

By 28 October 1916 Hudson had got over the worst effects of the gas poisoning, and on that day he appeared before a third Medical Board, which concluded that his recent attack involved “symptoms of nervous dyspepsia and flatulence (not heart disease)” and granted him another month’s leave from active service but declared him fit for more light duties at home. On 13 November 1916 a fourth Medical Board repeated the diagnosis, but on 5 December 1916 a fifth Medical Board, at the Military Hospital, Devonport, judged that he had completely recovered after being taken ill with dyspepsia, and that although he had rheumatism in his left shoulder, he was showing no signs of vascular heart disease. Nevertheless it granted him yet another month’s leave from active service.

During Hudson’s slow convalescence in England, the Allies on the Salonika Front began to advance north-westwards into the mountains of northern Greece. Hudson’s 11th Battalion was involved in this advance, and by 31 July it was in reserve at Chuguntsi, about ten miles south of the Greco-Macedonian frontier. From here, during the second week in August, it moved northwards until it became part of the left of the Allied line and was facing the Bulgarian defensive positions that were situated on the high ground around the south of the town of Doiran. The south-western part of this line, between Krastali and Doiran (three miles away), consisted of two hills: Horseshoe Hill and, just to the south of it, Kidney Hill. On 16 August 1916, the French, on the right of the Allied line to the south of Doiran, began the attack, and this was followed one day later by a British attack on the left. The intense fighting which then ensued, and in which the 78th Brigade took an active part, included the Battle of Horseshoe Hill (10–18 August 1916) and the Battle of Machukovo (13–14 September 1916). It ended with the capture of the small hill to the north-east of Doldzeli known as “le mamelon” (11/12 October 1916) and an unsuccessful assault on the Bulgarian lines near Doldzeli and the Vladava Ravine (14 October 1916). Shortly after that, the 11th Battalion was pulled out of the line, having lost 57 of its members killed, wounded and missing, and although it was back in the trenches near Doldzeli from 8 to 15 November, it did not, judging from the Battalion War Diary, take part in the Serbian–French cross-border assault that started in freezing rain on 10 November 1916 and opened up the way for the capture of Monastir, in southern Serbia, nine days later. The Balkan winter that followed this success was very severe, making a further advance impossible and putting a halt to hostilities in general. Nevertheless, the 11th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment spent the winter either in the forward trenches near Horseshoe Hill, Doldzeli and Bekirli, or in the reserve trenches well to the south, at Mihailova Ford, Rates and Chugnutsi.

The Battalion remained on the Salonika Front until hostilities ceased there in 1918, but Hudson did not rejoin it, since in February 1917 he took command of ‘B’ Company in the Worcestershire Regiment’s 3rd (Regular) Battalion, which was then part of 7th Brigade in the 25th (North-Western) Division. After its formation at Tidworth on 4 August 1914, the 3rd Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment had served in France and Belgium since 16 August 1914 and seen a great deal of action during 1916 in particular, starting with the defence of Vimy Ridge in May and concluding with the Battle of the Ancre Heights in November. So Hudson joined it in the general area of Nieppe and Steenwerck in northern France while it was making up for losses and undergoing training for ten weeks (1 February–14 April 1917). Nevertheless, the “completely recovered” Hudson showed that he was still not particularly strong and consequently prone to disease, since, on 6 March 1917, a Medical Board at Boulogne Base Hospital gave him ten days’ leave in England because of debility following a severe attack of rubella (German measles). In the second half of April, after spending a very brief period in the trenches near Le Bizet, on the Franco-Belgian border, the 3rd Battalion continued its training in the general area of Strazele, Méteren, Bailleul and Nieuwkerke (Neuve Église) until 1 June 1917. But on 2 June, during the run-up to the Battle of Messines Ridge (7–14 June 1917), the Battalion War Diary records that “‘B’ Coy, under the command of Lt A.J.B. Hudson and accompanied by 2/Lts S.T. Dixon and C. Greenhill, paraded about 80 strong and marched to the trenches to carry out a raid. The objects of the raid were to capture prisoners, reconnoitre the enemy’s trenches and ascertain the method of holding them.” Although the action followed an artillery barrage and lasted only 18 minutes, many Germans were killed and 15 were captured, of whom three were killed while crossing no-man’s-land on the way back. The report concluded: “For the most part the enemy showed little inclination to fight, and appeared to be glad to be taken.” The action cost the Battalion 13 Other Ranks killed, wounded and missing, and on 26 July 1917 Hudson was awarded the Military Cross for his part in it. The citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during a raid upon enemy trenches. He kept touch with the various parties and maintained direction throughout with great coolness and skill, thus ensuring the success of the raid” (no entry in the London Gazette).

Messines Ridge is a stretch of high ground that forms a natural stronghold to the south-east of Ypres, curves southwards from Sanctuary Wood, past Wytschaete village and Messines (Mesen), and ends to the north of Ploegsteert Wood. The Battle to take control of this key feature was fought by four Corps of General Plumer’s 2nd Army: X Corps in the north opposite the all-important Hill 60 (see A.H. Huth); IX Corps in the centre opposite Oosttaverne; II ANZAC Corps – which included the British 25th (North-Western) Division – in the south opposite Messines and the more distant Warneton; and XIV Corps in reserve. The Battle was preceded by a week of intense and highly effective artillery bombardment which ceased at 02.50 hours on 7 June, causing the Germans, who believed that an attack was imminent, to leave their trenches and man their fortifications. But on the evening of 6 June 1917, the 3rd Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment had assembled in Onslow Trench, to the west of Wulverghem, and when, at 03.10 hours, 19 of the 21 huge mines that British, Canadian and Australian tunnellers had been laying with great care and secrecy under the German positions since 22 August 1916 exploded in rapid succession, the devastating noise came as a great shock to many of the Allied troops. But the mines, which contained a total of 455 tonnes of ammonal, killed at least 8,000 Germans, traumatized many others, and created huge craters with an average diameter of between 160 and 200 feet.

Then, at 03.10 hours on 7 June 1917, just as dawn was breaking, Hudson’s Battalion charged forward and captured its main objective, Hell’s Farm, just in front of Messines, in what has been described as a “sharp fight”, probably with the 17th Bavarian Infantry Regiment. But the 3rd Battalion’s casualties were heavy, and it lost 10 officers and 239 Other Ranks killed, wounded and missing, including Hudson, who was killed in action, aged 23, half-an-hour or so after the beginning of the assault while leading the remnants of ‘B’ Company forward into the German positions. A brother officer, Lieutenant R.C. Perry, who survived the war and was with Hudson when he died, later described the events in a letter to Hudson’s parents:

The attack commenced at 3.10 AM in the dark, & on dawn breaking I found myself with about a dozen men in the German third line. Here your son appeared with a few men, whereupon we joined forces and pushed on to the next trench. On gaining it we found ourselves swept by the fire of a machine gun in our right rear and which had either been passed unnoticed by the troops on our right, or had not been [noticed] by them.

By lying flat and keeping quiet, the group managed to deceive the enemy machine-gunners, allowing some of its number to scramble from cover while avoiding the enemy fire. But one of the bullets hit Hudson in the head and emerged from his left temple, wounding him mortally at about 03.45–04.00 hours. Because attacking troops were under strict orders not to stay with wounded during an attack, Perry had to leave Hudson where he lay, but assured his parents that his “wound was such that he was spared all pain and consciousness”.

Hudson was buried in Lone Tree Cemetery (Spanbroekmolen), Wytschaete (east of Kemmel and a mile and a half to the north-west of Hell’s Farm), in Grave I.B.1. The inscription is: “Jesu, for thy bitter passion bring his soul to thy salvation” (probably adapted from a novena in the Catholic tradition). The Cemetery is just near Lone Tree Crater (now known as “The Pool of Peace”). Measuring 250 feet across and 40 feet deep, the crater was created on 7 June 1917 by the third largest of the Messines mines, containing 41 tonnes of ammonal, beneath the German strong-point on Spanbroekmolen knoll, and many of the 58 men of the 36th (Ulster) Division who are buried in Lone Tree Cemetery were killed there on that day because of the explosion’s unexpected force.

On 10 June 1917, Hudson’s father wrote a letter to President Warren in which he said:

Thank you for remembering him in Chapel – One of his last letters told of a strength which came to him from the prayers which he knew were going up for him – and they will help him still. […] I never could teach him to love books – but I have tried to teach him to love God, and to seek His grace in the Sacraments, and he has ‘kept the Faith’ – He made his last Communion in preparation for the battle on the day before – So, his last few hurried lines told us, to our comfort – I am sure he did his duty to the end. […] The one thing to set against it all [our loss] – so far as this world goes – is, that we are able to take our place in that great company from which such sacrifices have been claimed for England’s sake.

Hudson is commemorated in: Malvern Priory, Worcestershire; St Mary’s Parish Church, Wick-near-Pershore, Worcestershire; and in the side chapel of the Chapel at Wyke Manor, near Pershore, Worcestershire, where an alabaster effigy of him reposes on a quatrefoil tomb-chest. His parents set up a Memorial Trust which is still in existence and helps disabled ex-service personnel with accommodation. On 10 June 1917, the diarist and Fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb noted in his Diary: “Sad news of Alban Hudson’s death. The apple of his parents’ eyes – their only child.” Hudson left £271 3s. 2d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Peter C. McIntosh, ‘MacLaren, Archibald (1819?–1884)’, DNB, 35 (2004), p. 722.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant Alban John Benedict Hudson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,529 (13 July 1917), p. 5.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 23 (15 June 1917), p. 313.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 114–16, 125–6, 146–7.

Gilbert (1994), passim.

Peter Oldham, Messines Ridge (Barnsley: Leo Cooper [Pen and Sword Books], 1998), passim.

Alexander Turner, Messines 1917: The Zenith of Siege Warfare (Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2010), passim, but especially pp. 50–85.

Wakefield and Moody (2011), passim.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/79.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1162.

WO95/1415.

WO95/2244.

WO95/2247.

WO95/2253.

WO95/4874.

WO95/4896.

WO339/176.

On-line sources:

‘11th Battalion Worcester Regiment’: http://www.worcestershireregiment.com/wr.php?main=inc/bat_11 (accessed 29 October 2017).