Fact file:

Matriculated: 1905

Born: 14 April 1886

Died: 29 March 1917

Regiment: London Regiment (London Rifle Brigade).

Grave/Memorial: Mazargues War Cemetery: III.A.3.

Family background

b. 14 April 1886 as the younger son (of three children) of Arthur Raymond Kirby (1842–1916) and Gertrude Kirby (née Fleming) (1851–1936) (m. 1880). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family (plus seven servants including a butler) were living at 81 Cromwell Road, London SW7, and Kirby’s mother continued to live there after Arthur Raymond’s death.

Parents and antecedents

Kirby’s father was a conveyancer and the eighth of 13 children of George Goldsmith Kirby (1806–68), who was also a conveyancer. According to his obituarist, Arthur Raymond was “an able exponent of the law of companies”. Called to the Bar in 1866, his career virtually coincided “with the great development of our system of company law which, after the passing of Lord Thring’s Act in 1862, was in progress until the early years of [the twentieth] century”. He was known for his skill as a draftsman and “his drafts stated in a few words what an ordinary draftsman might fail to convey in a page of foolscap”. As such, he was much in demand. He became a Bencher of Lincolns Inn in 1902 and so would have known the fathers of Geoffrey Cadwallader Adams and Thomas Bourchier Cave.

Kirby’s uncle, Lieutenant Montagu Alexander Goldsmith, another of George Goldsmith’s sons, died of wounds received in action while serving with the 78th Foot – the Seaforth Highlanders – during the Indian Mutiny (1857), and two more of George Goldsmith’s grandsons (i.e. Kirby’s cousins), both resident in Australia, died of wounds or disease while serving in the forces during World War One.

Kirby’s mother was the youngest child of William Fleming (1797–1861), a leading merchant of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, a partner in Heugh and Fleming. He sat in the upper house at the meeting of the first Cape Parliament and was a Member of the Legislative Council.

Siblings

Brother of:

(1) Claude Arthur (later OBE; 1882–1959);

(2) Elsie Harriet (1883–1967).

Claude Arthur was at Magdalen from 1901 to 1904, read for a Pass Degree in Classics and became a Barrister. He joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as an Able Seaman on 20 October 1911 and was promoted Chief Petty Officer on 18 November 1914 while serving in the Navy’s Anti-Aircraft Corps. On 19 January 1915 he was commissioned Sub-Lieutenant and by the end of the war he was working in the experimental workshops of the Royal Naval Air Service with the rank of Commander. During World War Two he served as an officer in the Royal Air Force. He left his entire estate (£44,000) to his sister.

On Claude Arthur’s death, Elsie Harriet went to live in Portcullis House, a five-bedroom Edwardian hunting lodge where her brother had died and which, during World War One, had been used as a Red Cross nursing home.

Education and professional life

Kirby attended Cheam Preparatory School, near Epsom, Surrey, from c.1893 to 1899 (cf. J.R. Platt, L.S. Platt, G.T.L. Ellwood, A.F.C. Maclachlan, R.N.M. Bailey, E.W. Benison, C.P. Rowley). Founded in c.1645 by the Reverend George Aldrich (1574–1658), it moved to nearby Tabor House in 1719, where it stayed until 1934 when it moved to its present site at Headley, Hampshire. It was sometimes known as Manor House Preparatory School because that, according to the Censuses, was the proper name of its buildings, and from 1856 it was also sometimes known as Mr R.S. Tabor’s Preparatory School because this was the year when the Reverend Robert Stammers Tabor (1819–1900) became its Headmaster (until 1890) and set about turning it into a purely preparatory school. Arguably, it became the top preparatory school in the country. Kirby then attended Eton College from 1899 to 1905, where, in 1904, he played in the Oppidan and Mixed Wall Games. He also took up rowing at Eton, and in 1903, under his Housemaster’s tuition, he rowed in the Junior House IV which made four bumps. In 1904, after rowing in the winning crew of the trial VIIIs, he was given his colours, and in 1905, when he was Vice-Captain of Boats, he rowed in the powerful Eton VIII that won the Ladies’ Plate at Henley by defeating New College, Oxford, St John’s College, Oxford, and First Trinity. Kirby would then row at Henley every year until 1912 apart from 1908 (see below).

Having passed Responsions in Michaelmas Term 1904, Kirby matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 October 1905, and on 2, 3 and 4 November of his first term he helped an all-Etonian Magdalen crew win the University Coxless IVs (also known as the Varsity IVs), rowing against crews from Trinity, St John’s, University College and New College – an achievement that he repeated in 1907 and 1908. On 3 December 1905 he rowed at No. 5 in the Trial VIIIs, as a result of which he was selected to row in the Oxford crew against Cambridge on 7 April 1906, when Cambridge won easily. When summarizing Kirby’s achievement, his Times obituarist called him “one of the most famous oarsmen of the last decade”, an opinion that is borne out by the facts of his rowing career. Once an undergraduate at Magdalen, Kirby, “a powerful and stylish heavy-weight”, helped the College to win the Oxford University Boat Club (OUBC) IVs in the Mays for three out four successive years (1905–08). He also rowed at No. 2 in the crew captained by H(enry) C(reswell) Bucknall (b. 1885 in Lisbon, d. 1962), which won the OUBC Trial Eights, making it inevitable that he should be picked out as an oarsman of great promise, not least because of his size – he was 6 foot 4 inches tall and normally weighed 13 stone 12 lb. Consequently, to quote one of his obituarists once more, “it is not surprising to find that he soon began to make his presence felt in the sport which was to claim so large a share of his time and energy”.

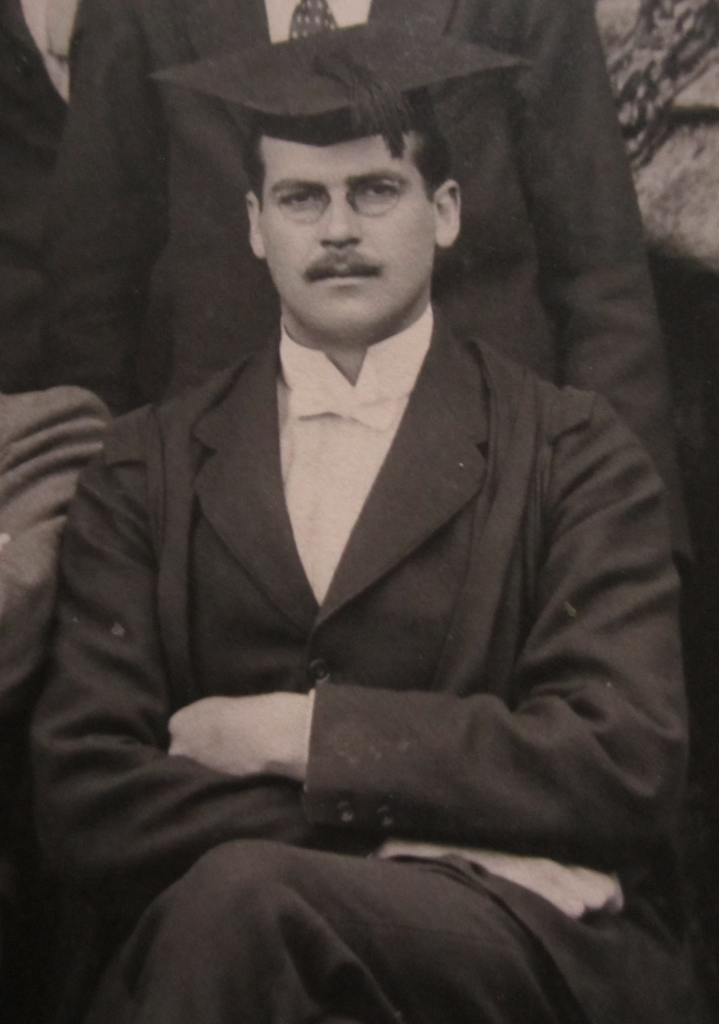

Alister Graham Kirby: “An enthusiast in rowing and a man of kindly and unassuming disposition.”

(Courtesy of Magdalen College)

Kirby was awarded the first of his four consecutive Blues in April 1906, when, as Magdalen’s only representative apart from R.P. Stanhope, who was “Spare Man”, he rowed at No. 5 in H.C. Bucknall’s University crew. Although this consisted of large and powerful men, it was not fast enough to win the race. He did not row in either of the Torpids boats that Magdalen entered for the races at the end of the Lent (Hilary) Term of 1906 even though, as the Secretary noted in his book, “the state of the Rowing at Magdalen is prosperous in the extreme, being Head of the River, having won the Fours, the 1st Torpid being Second on the River and the Second Torpid having made 7 bumps [the highest possible number]”. But in Eights Week (17–23 May 1906), Kirby was a member of Magdalen’s VIII in company with J.L. Johnston (No. 4), E.H.L. Southwell (stroke), R.P. Stanhope (bow) and L.R.A. Gatehouse, the Captain (No. 6). But although Harcourt Gilbey Gold – their distinguished coach (see G.S. Maclagan) – had described them as “Bad and Featureless” as late as 8 May, when training was well under way, they managed to hold off their old rival New College for five nights and stayed Head of the River for the second year running. Magdalen’s Captain of Boats described the race as follows in his report in the Captain’s Book:

First Day of Eights: New College bumped Univ. before the Gut so we rowed over. [On the Second Day] New College came up on us at the start, but never in danger we rowed away from them from the Gut to the Finish. Christ Church bump[ed] Univ. [19–22 May] As before New College made great efforts to catch us at the Start & as we were slow getting away, they gradually came rather closer than we could have wished, but were always out of danger after the Gut. [23 May] Got away harder & New Coll[ege] hardly came up on us at all. We made a great effort & finished up quite two distances ahead of them.

When evaluating the performance of the crew, Magdalen’s Captain of Boats referred to Kirby – who, at 13 stone 8 lb was the crew’s second heaviest member – as “The best oar in the boat. Very long, steady, and a firstclass [sic] worker, also an excellent racer.”

After a couple of substitutions during practice, the same five men rowed in Magdalen’s VIII when, on 3 July 1906, it competed at Henley for the Grand Challenge Cup, but was beaten by one-and-a-quarter lengths in the first round by the powerful Belgian Club Nautique de Gand. This particular Magdalen crew was one of the two College VIIIs that would lose five of its nine men killed in action. At about the same time, Magdalen’s rowing nomenclatura resolved that a big effort should be made during the following three years to train a Magdalen crew that was good enough to win the Grand at Henley and to subordinate every other consideration to doing so, as this was the one major honour that the Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC) had still to win. The MCBC’s growing determination to secure Magdalen’s reputation as a rowing college can also be inferred from the fact that it entered two boats in the Coxless Fours (31 October–2 November 1906), and although their second crew outshone their first crew (which included Kirby), Southwell, now the Club’s Secretary, made it quite clear that “Kirby at 5 was, as usual, a tower of strength.”

On 16 March 1907, with Southwell in front of him at No. 7, J.A. Gillan behind him at No. 5, and A.W.F. Donkin in front of him as cox, Kirby won his second Blue when he rowed at No. 6 in the University crew that was captained by A(lbert) C(harles) Gladstone (1886–1967; Christ Church, Oxford, 1905–09, the grandson of the former Prime Minister and later the 5th Baronet) and lost to Cambridge by four-and-a-half lengths. And during Eights Week (23–29 May 1907) Kirby rowed in the College VIII that included Stanhope, D. Mackinnon, Southwell and J.R. Somers-Smith, the second Magdalen VIII that was destined to lose five of its nine men killed in action. This time Christ Church – a very strong crew – went Head of the River with Magdalen in second place, and when the Secretary pondered in his notes why this should have been the case, he came to the conclusion that the crew were too heavy and thus liable to go very slowly in the middle of the river unless they were helped by a following wind, that they had gone in for too much experimentation with new-style oars, and that the crew did not make up its mind early enough. Nevertheless, at Henley from 1 to 6 July 1907, the MCBC excelled itself by carrying off all the three four-oared races: Somers-Smith, Mackinnon and the Australian Collier Robert Cudmore, the brother of Milo Massey Cudmore, were members of the Second IV that won the Visitors’ Challenge Cup by two-and-a-quarter lengths and then the Wyfold Challenge Cup “easily”; whilst the First IV, which won the Stewards’ Challenge Cup by three lengths, included Kirby himself, Stanhope and Southwell. All three would die within a mile or so of one another on 15 September 1916, the opening day of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, when tanks were deployed in battle for the first time (see the excursus in E.L. Gibbs).

Magdalen II, winners of the Oxford University Boat Club Fours, 1908; left to right: J. Forrest, J.A. Gillan, A.G. Kirby and J.R. Somers-Smith

(Courtesy of Magdalen College)

During the academic year 1907/08, Kirby was also President of the OUBC and Secretary of the MCBC, whilst his friend Southwell moved up to be the Captain of the MCBC. In the Michaelmas Term of 1907, Magdalen’s First IV again won the coxless IVs, with Somers-Smith at bow and steering, Kirby at No. 3, and Southwell as stroke. But despite that initial victory, the academic year 1907/08 was an unlucky one for Kirby and the MCBC. After Christmas 1907, Southwell had to drop out of rowing for Magdalen for academic and disciplinary reasons and was replaced as Captain of the MCBC by Kirby, who was in turn replaced as Secretary of the MCBC by J.A. Gillan. And although, on 4 April 1908, Kirby gained his third Blue by rowing at No. 5 in A.C. Gladstone’s University VIII with C.R. Cudmore (at No. 2), Southwell (at No. 3) and Stanhope (at bow), almost every member of the Oxford crew succumbed to influenza during the practice weeks, with Kirby “as the worst sufferer in this respect” since he went down with jaundice so badly that “at one time it seemed unlikely that he w[oul]d row” and he did so only against his doctor’s advice. As a result, the badly weakened Oxford crew lost to Cambridge for the third year running, this time by two-and-a-half lengths.

Then, for the Summer Eights of 1908 (21–27 May), Kirby rowed in Magdalen’s 1st VIII together with Cudmore (at No. 7), D. Mackinnon (at No. 4) and Somers-Smith (Cox). But Magdalen was up against two even stronger crews – Christ Church and New College – and remained Second on the River, having been bumped by Christ Church, who went on to win the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley a month later. Gillan evaluated his crew’s performance as follows:

There was any amount of power in the crew, but we never managed to make proper use of it, owing largely to never getting quite together. The worst faults were heaviness and slowness over the stretcher, and slipping the slides badly. The stream was very strong, the towpath being for long [stretches] completely under water.

When, however, Gillan wrote notes on the individual members of the Magdalen VIII, he said that “Kirby (at 6) was largely responsible for what pace we had, but he was also below form, as he had not recovered properly from his illness during Varsity training.” Moreover, in 1908 the Olympic Regatta at Henley took place from 28 to 31 July, three weeks after the annual Henley Royal Regatta (which normally takes place from the Wednesday to the Saturday before the first weekend in July) and caused considerable interference. So, because Kirby was in the Leander Trial VIII for the Henley Olympics, he was not available to row in Magdalen’s IV, and for the one and only time between 1904 and 1912, he did not take part in the Henley Royal Regatta.

But finally, in spring 1909, during Kirby’s second year as President of the OUBC (1908/09) – an unusual distinction – he rowed for the fourth time against Cambridge as No. 7 in Robert Croft Bourne’s (1888–1938) first crew, even though, according to Gold’s long obituary of 14 April 1917, he was very uneasy over Oxford’s three previous defeats at Putney and wondered whether he had fulfilled his early promise and ought, perhaps, to give up his place in the Oxford VIII. But after three weeks of observation and deliberation, expert opinion, provided by Gold himself and the legendary Claude Holland (1865–1917; a famous oarsman of Balliol College, Oxford, when its crews were at the height of their prowess), persuaded him to stay, and “from that time onwards his true merit as an oarsman asserted itself”, not least when he “backed up Bourne in the great spurt at Barnes which settled the chances of the favourites” (see below).

According to Gold, the Oxford crew, which had been “heavy, clumsy, and backward in the early stages of training”, eventually turned out to be “one of the finest crews that ever rowed between Putney and Mortlake”:

This crew, rowing the full course ten days before the race, beat the previous record by 24 seconds, completing the distance in 18 mins. 21 sec. In spite of this, the Press critics failed to realise Oxford’s speed, and Cambridge started with the odds 3 to 1 in their favour on a delightfully calm day. The two crews which came to the post were probably the two best which have ever taken part in the same race. At the start, the two crews raced for the lead and rowed a high rate of stroke, first one leading by a trifle and then the other, and for three miles there was never half a length between them. But at this stage the turning point of the race came, for Bourne gave his crew the opportunity of showing its worth, and to the astonishment of many they dashed out like a fresh crew and won one of the most sensational races of modern times.

President Warren was thinking of this race when, in his obituary of 1917, he credited Kirby with carrying “his College to the front at Oxford and at Henley” and turning “the tide of Cambridge success” by beating “one of the strongest Cambridge crews that ever appeared at Putney”.

Back at Oxford, in Eights Week 1909, Kirby had D. Mackinnon and Somers-Smith in the crew which again went Second on the River. But Magdalen’s Captain noted that despite being “a good waterman, who always tries to pick up the stroke quickly”, Kirby was “too heavy and slow for a 7: he tried to row neatly, and so lost his power”. But in summer 1909 at Henley, Kirby, together with Somers-Smith, Mackinnon and Stanhope, also rowed in the crew that was competing for the Grand Challenge Cup. Unfortunately, Kirby sprained his knee badly while training and had to row the race with his leg bandaged, while Stanhope at stroke strained his stomach and had to row with his body strapped up. Not surprisingly, the Magdalen VIII was beaten once more by the Belgians – but only by half a length.

After graduating in late summer 1909, Kirby left Oxford and did not row for a year, by which time he had been elected Captain of Leander. So at Henley in summer 1910 he not only rowed in the Leander IV that was defeated by Thames in the Stewards’ Cup, he also captained the powerful Leander VIII that was beaten by D. Mackinnon’s Magdalen VIII, which included M.M. Cudmore and W.D. Nicholson, in a gruelling final of the Grand. In 1911 things looked up, for when Cudmore dropped out of the Magdalen VIII that went to Henley, Kirby took his place. Moreover, although Kirby’s IV was beaten by Thames in the competition for the Stewards’ Cup, he helped Magdalen’s exceptionally fast crew, which averaged 12 stone 10¼ lb in weight and 6 foot 1½ inches in height and included Mackinnon, to win the Grand for the second year running by defeating New College, Ottawa, and Jesus College, Cambridge. In 1912, the year when the duty of sending a representative VIII to Stockholm to defend the Olympic Cup devolved upon the Club, Kirby captained Leander for the third year running. As things turned out, Kirby, who rowed at No. 7, was one of the seven Magdalenses to be selected for the Leander VIII which represented Britain. But before going to Stockholm, it was decided that the Olympic VIII should also compete at Henley for the Grand. But the VIII were not up to form in time and lost the final to Sydney (NSW) after a grand struggle that was witnessed by King George V and the Queen from the umpire’s launch. But three weeks later, after two weeks of intensive training, Kirby’s Leander VIII were in top form and turned the tables on the Australians by carrying off the trophy at Stockholm for eight-oar rowing. This was Kirby’s last race. After his retirement from competitive rowing, he turned his attention to coaching – with considerable success, as in 1913, for example, when he helped G.C. Bourne and Harcourt Gilbey Gold to coach the Oxford VIII that won the Varsity race against Cambridge on 13 March by three-quarters of a length.

Kirby was acquainted with all the major oarsmen of the era, not just those whom he met at Magdalen, and despite his success he enjoyed a wide circle of friends. So as early in his rowing career as November 1906 the Oxford student newspaper Isis hailed him as one of their “Isis Idols” in a piece that was probably written anonymously by the novelist Compton Mackenzie (1883–1972; Magdalen 1901–03), whose Sinister Street (written 1913–14), is partly set in St Mary’s College, Oxford, a thinly disguised Magdalen. The Isis eulogist distinguished Kirby from the average rowing “heavy” when he said that:

in this welterweight oarsman we have no barbarous, illiterate giant – none of your Oida’s heavy beer-swilling, moustache-twirling Philistines: rather a happy combination of mind and matter, and a by no means illiberal allowance of both. He is one of those few favoured mortals who can appreciate and talk learnedly too about the old china, curios, pictures – anything you like and as long as you like – that are to be found in the cabinet and the drawing room. He would like to be an antiquarian, but he has not the time.

And in his obituary of 1917, President Warren amplified this judgement, calling Kirby “kindly, good-tempered [and] modest amid all his successes”. Besides being a prime mover in Oxford’s rowing circles, Kirby was President of the elite Vincent’s Club in 1909, and, at about the same time, the Secretary of the notorious Bullingdon Club, a dining club for upper-class yobs that was founded in 1780 and is now (2019) happily in terminal decline. Warren later added to his encomium by saying that when Kirby became President of Magdalen’s Junior Common Room for the academic year 1908/09, he “took the leading position which was natural to him, and in the days of peace he was one of the first to support the development of the OUOTC alike by his advocacy and his example” (see below).

Kirby sat the First Public Examination in Trinity Term and October 1906, and then, from Michaelmas Term 1907 to Trinity Term 1909, he read for a Pass Degree (Groups A1 [Greek and/or Latin Literature/Philosophy], B1 [English History], and B3 [Elements of Political Economy]). He took his BA on 6 November 1909 at the same time as Collier Robert Cudmore (see M.M. Cudmore), Somers-Smith and C.A. Gold, the cousin of Harcourt Gilbey Gold, who, on 14 April 1917, would publish Kirby’s most extensive obituary in the magazine The Field. At Magdalen, Kirby was a particular friend of D. Mackinnon and the two of them were known to be the life and soul of the Sunday evening smoking concerts in Magdalen’s Hall that were known as “Afters”. After taking his BA on 8 November 1908, Kirby began studying Law as a member of the Inner Temple with a view to working in the family firm. He obtained a 2nd in the Council of Legal Education’s Examinations on 25 May 1910 and a 3rd in Real Property and Conveyancing in the Council’s Examination on 2 November of the same year, and was finally called to the Bar in 1914.

In this photograph from Stockholm (1912), the Leander crew is getting ready for an outing. From the stern: coxswain Henry Wells, stroke Philip Fleming, 7 Alister Graham Kirby, 6 Arthur Stanley Garton, 5 James Angus Gillan, 4 Ewart Douglas Horsfall, 3 Leslie Graham Wormald, 2 Sidney Ernest Swann, bow Edgar R. Burgess.

(From the collection of Leander Club. Reproduced by permission of Leander Club)

Military and war service

In his obituary, President Warren wrote:

Alister was not merely an oarsman or athlete, though for a time his achievements in this capacity were the most conspicuous part of his career. He was a man of very good ability and characteristic English sense, and his energies were not confined even then to the Boat Club.

In saying this, Warren was thinking specifically of the part that Kirby had played in popularizing the Oxford University Rifle Volunteer Corps (OURVC), which became the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps (OUOTC) in 1908, for he continued: “On one important and now historic occasion […], he represented the whole body of undergraduates before the world.” The occasion was on 14 May 1908, when Mr Richard Burdon Haldane (1856–1928; later 1st Viscount Haldane), the Minister of State for War (1905–12), who was busy reforming the British Army in preparation for a possible war with Germany, came to Oxford to address a mass meeting of undergraduates in the Town Hall on the OUOTC. Warren continued:

The gathering was a very striking one, and pre-eminently successful: I have often thought of it since. Two men of striking physique took part in the proceedings, towering above their fellows, fine as were many of these. They were Lord Lucas [1876–1916; 9th Baron Lucas], himself an old Rowing Blue [Balliol], who came as Haldane’s [Under-]Secretary [for War, 1907–08], and Alister, who, as President of the OUOTC, was selected to speak, and to make what was, in fact, a promise of support. He did so tersely and appropriately, and with complete ease. How little did we realise how soon the call of which Mr Haldane spoke would come to Oxford men, how soon that promise was to be redeemed.

But in his obituary, Warren omitted to say either that he, as Oxford’s Vice-Chancellor, had summoned the meeting in question, or that it had been preceded by a preliminary meeting that had been organized by the National Service League and taken place in Magdalen’s Hall on 8 May 1908. The report on that meeting which had been published on the following day in The Times had almost certainly been written by Warren in his capacity as Oxford Correspondent of The Times, and recorded the event as follows:

Among those present were the Vice-Chancellor in the chair, the Master of Balliol, the Rector of Exeter, the Warden of New College, the Provost of Worcester, one of the Volunteers of 1859, the Censor of non-collegiate students, Professor Bourne, Colonel Waller, commanding the O[xford] U[niversity] V[olunteers], Captain Maclachlan, adjutant to the O.U.V., Major Hicks, Keble College, Captain Slessor, Christ Church, and a number of resident graduates. Dr Bourne and Colonel Waller explained and advocated Mr. Haldane’s scheme, and general sympathy and desire to promote it were expressed. A number of meetings of undergraduates have been held in the various colleges, and much interest is being taken in the scheme.

So it is not surprising that Kirby was commissioned Second Lieutenant with effect from 8 July 1908 in the 1st (Volunteer) Battalion of the Oxfordshire Light Infantry and played a leading part in the OUOTC, to which his Territorial Commission was transferred with effect from 17 July 1908 (London Gazette, no. 28,180, 30 October 1908, p. 7,907; no. 28,216, 19 January 1909, p. 484).

Warren also noted in Kirby’s obituary that “like so many Magdalen men” – e.g. G.H. Morrison (‘A’ Company), J.R. Somers-Smith (‘P’ Company), G.H. Cholmeley (‘A’ Company), G.H. Foster and H.L. Johnston, MC (‘P’ Company), H.B. Price and H.G. Vincent (‘E’ Company) – Kirby, after leaving Oxford, was recruited for the 5th (City of London) Battalion (The London Rifle Brigade), the London Regiment (Territorial Force) and commissioned Second Lieutenant. But although he was promoted Lieutenant with effect from 31 July 1909 (London Gazette, no. 28,285, 3 September 1909, p. 6,665), he resigned his commission on 26 November 1913 and rejoined the Battalion when it was mobilized on 4 August 1914 and assembled at its HQ at 130, Bunhill Row, London EC1, as part of the 2nd London Brigade, in the 1st London (Territorial) Division. Kirby was allocated to ‘G’ Company, whose Commanding Officer (CO) was another distinguished Magdalen rower, the Honourable Major Charles (“Don”) Burnell (1875–1969) (later DSO, OBE). Burnell had gained a rugby Blue and four rowing Blues while at Oxford (1895–98), helped to win the Grand Challenge Cup (1898–1901) and the Stewards’ Cup at Henley (1899–1900), and rowed in the 1908 Olympic Regatta. He had also been in the London Rifle Brigade (LRB) from 1892 to 1912 and rejoined it in 1914; he would be severely wounded on 2 May 1915. From 22 April to 20 May 1917 and 10 May 1918 to the end of the war he acted as the Battalion’s CO and was one of its three original officers from August 1914 who managed to survive the war. On 15 August 1914 the Battalion volunteered for service abroad and then trained in Surrey until 3 November at Bisley, East Grinstead, and Camp Hill near Crowborough, where, despite tents and poor food, everyone became very fit thanks to the digging and marching.

On 4 November 1914, the Battalion, consisting of 30 officers – all products of major British public schools – and c.855 ORs, many of whom were City clerks, embarked on the SS Chyebassa (1907–38; broken up), a former cattle-carrier – at Southampton. After a cramped and uncomfortable crossing, it arrived at Le Havre early on the following morning, after which many of the men had to spend a frosty night in the open as the battalion had been supplied with insufficient tents. On 6 November, the Battalion left Le Havre in wretched weather conditions to travel by train and on foot in a north-easterly direction towards Ypres via St-Omer, Wisques, Hazebrouck and Bailleul. On 19 November the Battalion arrived in the middle of a blizzard at the village of Romarin, a mile and a half west of Ploegsteert, where the old eight-company system was replaced by the four-company system three days before the end of the First Battle of Ypres, having become part of 11th Brigade, 4th Division, III Corps two days previously. At Romarin, too, the LRB was prepared for trench warfare by two experienced Regular battalions – the 1st Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry.

By 22 November 1914, the LRB was positioned behind the lines in the Ploegsteert area, at the southern end of the Ypres Salient where the trenches followed the eastern edge of Ploegsteert Wood to the east of Ploegsteert village, with periods in the front-line trenches when they were attached to their mentor regiments. The men soon found that if life behind the front lines building reserve and communication trenches was tedious, then conditions in the front-line trenches were very bad, for the steady downpours and naturally high water table meant that the trenches, once pumped out, soon refilled, so that most contained two foot of icy water. Consequently, their walls were continually collapsing and it took three men to fill a sand-bag: one to hold it open, one to shovel, and one to scrape the mud off the shovel. Moreover, the pumps supplied by the Army at that stage of the war were inefficient and, according to Mitchinson, “frequently broke down and on occasions suction and exhaust pipes were fitted to the wrong inlet and outlet valves”. Kirby, whom Mitchinson describes as “something of an ‘engineer’”, tried to design a more efficient pump, that was “subsequently manufactured in Britain and sent out to the battalion”. Unfortunately, “it proved no more successful” than the standard issue. But in early December 1914, Kirby redeemed his reputation as an engineer by persuading the boilers to work in a disused brewery to the east of Armentières, thereby permitting the Battalion to have baths. Nevertheless, according to the Battalion’s official history, the men

settled down extraordinarily quickly to their new life, so very different from anything that they had ever been accustomed to, one saving feature of which was that the food was excellent and abundant. Moreover, the authorities provided goat-skin coats, worn with the hair outside, which were very warm but gave a most amusing appearance to the officers and the men.

But on 12 December, Kirby was severely wounded in the left temple by shrapnel, which caused him functional paralysis of the left arm, and on 20 December he embarked at Le Havre aboard HMHS Asturias (1907; torpedoed at around midnight on 20/21 March 1917, south-west of Salcombe, Devon, while en route from Avonmouth to Southampton, with the loss of 31 lives and 12 missing; she was beached at Bolt Head, south-west of Salcombe, and rebuilt as the liner SS Arcadian in 1920). On 22 December, Kirby landed in England, where his left arm continued to give him trouble for some time. So on 27 January 1915 he was lent to the Anti-Aircraft Section of the Admiralty and did office work. He then appeared before seven Medical Boards until, on 23 August 1915, he was declared fit for General Service once more, having been promoted Temporary Captain on 4 May 1915. In October 1915 he became an instructor in the Young Officers School at Tadworth/Godstone, Surrey, where he took over the training of inexperienced officers that had been begun by Somers-Smith. In February 1916 Kirby, now a Captain, left Tadworth, probably to become aide-de-camp to Brigadier-General Grant, who commanded the artillery of 58th (2/2nd London) Division (London Gazette, no. 29,540, 7 April 1916, p. 3,766). Although it was noticed in November 1916 that he was suffering from some disquieting medical symptoms, he returned to France as an officer on the Staff of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division – probably during the final phase of its operations on the Ancre (January–March 1917). On 9 March 1917 he was gazetted Lieutenant with effect from 26 August 1914 (LG, no. 29,979, 9 March 1917, p. 2,462) and confirmed in the rank of Captain (GSO3) with effect from 1 June 1916 in the Divisional Artillery “with every prospect of further promotion” (LG, no. 29,976, 9 March 1917, p. 2,378). But the disquieting symptoms persisted, and on 18 March 1917 he underwent exploratory surgery in a Marseilles hospital which confirmed that he had terminal pancreatic cancer. He died at Marseilles on 29 March 1917, aged 29, after “prolonged suffering, borne without a murmur, and ending tranquilly in death, welcomed with a smile”. A senior doctor who treated him said “that in forty years of medical experience he had never seen death more calmly and bravely met”. So there is a sad irony in the fact that 11 years previously, Kirby’s eulogist in The Isis should have remarked that he “seems to have run the gauntlet of all the diseases of a medical dictionary, and not one could resist him.”

President Warren considered Kirby to be “one of the finest young Englishmen of his generation”, and the General of Artillery to whom Kirby was attached as Staff Captain sent a letter of condolence to Kirby’s parents in which he wrote:

You will allow me to say that your son was a gallant and able soldier and his death is a real loss to his country. He was a great help to me as A.D.C., and was always ready to assist in any department of staff work. It was a great pleasure to me to have recommended him for a higher appointment, which he obtained just before he was taken ill.

Kirby’s Eton obituarist asserted that “it was his remarkable organising power and the influence of his character which attracted the notice of the highest military authorities and presaged great service to his Country”. One highly placed military personage sent a letter to Kirby’s parents in which he said:

I cannot express to you what I feel and felt about Alister. No young man has ever come into my life bringing with him, not only a sense of charm and attractiveness but also the conviction of genuine strength and character. I had the most absolute belief in his making his name known to his countrymen. With all his modesty he could never conceal his effectiveness and strength and worth. I shall always treasure his memory and feel better for having known him.

While Gold conceded that his long obituary was intended in the first place to list Kirby’s achievements “as a rowing man” and to show “how effectively he brought his sterling qualities to bear on the form of sport he loved so well and did so much to foster and encourage”, he also claimed that “in this connection it might be said of [Kirby] without fear of contradiction that he played as large a part in the undergraduate life of Oxford as any man in modern times” and he went on to offer the following justification for his views:

Alister’s sphere of influence was unlimited, and he used it in a wise, far-seeing way, as a man of the world. There was never a trace of his head being turned by success; he was always the same – natural, modest and unassuming. The impression he gave to everyone was his reliability, his power to carry through anything he took in hand, his earnestness of purpose – all most valuable in inspiring confidence in men with whom he came into contact. He had an abundant sense of humour and an even temper, qualities which made him so delightful a companion, and which were instrumental in making for him so wide a circle of friends.

He then concluded his obituary as follows:

Thus ends an inadequate record of the life, all too short, of one of the nicest fellows it has been the writer’s privilege to know. Kindly of heart, he had no enemies because he refused to quarrel, and yet [he was] a commander and leader of men; fond of a simple method of living, yet appreciating gaiety, adaptable to the mood of his companion of the moment, the truest and staunchest of friends. It can be truly said that the magic names of Eton and Oxford were made famous by a particular class of man which is not easy to describe. It is defined by some in two words – “English gentleman”; but whatever is the correct definition[,] it is a certainty that the standard has been worthily upheld and revised by the life and example of Alister Kirby.

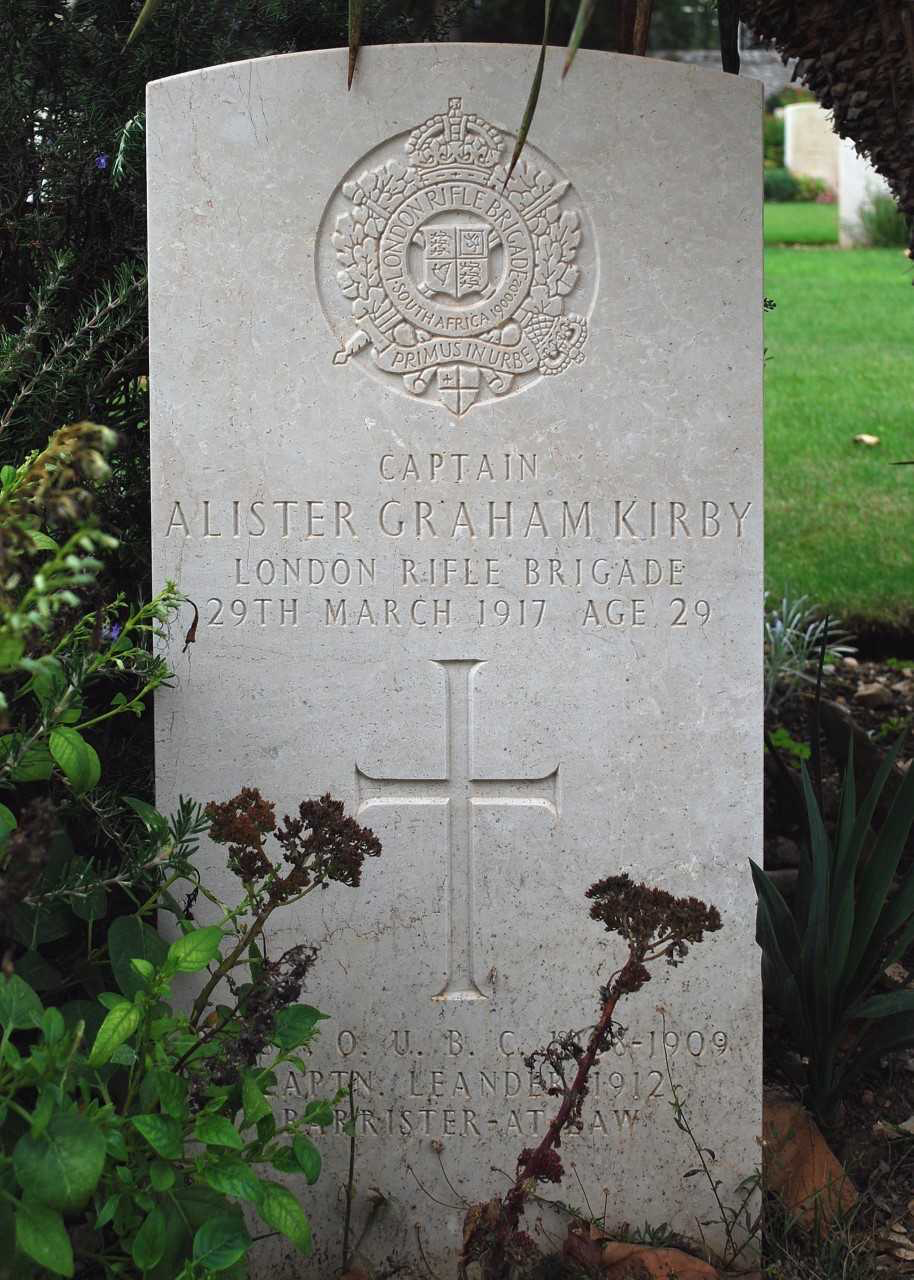

Kirby is buried in Mazargues War Cemetery (in a southern suburb of Marseilles on the southern side of the D559 to Cassis). The inscription reads: “Pres. O.U.B.C. 1908–1909 / Captn. Leander 1912 / Barrister-at-Law”. He left £631 9s 8d.

Mazargues War Cemetery is in a southern suburb of Marseilles and on the right-hand side of the D559 that runs due east to Cassis. As it is surrounded by houses, the cemetery is kept shut for most of the time, so that it is very difficult to get a photo of Kirby’s grave. This photograph was taken in the early evening through the cemetery’s front gates.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

The Editors would like to make it clear that Nigel McCrery’s excellent book Hear the Boat Sing (The History Press: Stroud, 2017) was brought to their attention as recently as January 2019. It provides detailed accounts of the lives of 42 Oxford and Cambridge Rowing Blues who died as a result of World War One, and as eight of these were Magdalenses or closely connected with Magdalen through a relative, it would seem that the Editors of The Slow Dusk and Mr McCrery have been following parallel research paths without being aware of each others’ existence and so have made use of the same resources. But whereas Mr McCrery has focused more on the finer points of top-class rowing, the Editors have focused more on family and social history. As a result the two projects not only overlap in places, but also complement each other well.

Printed sources:

[Compton Mackenzie (?)], ‘Isis Idol’, no. 337, No. CCCXXIV: Mr Alister Graham Kirby’, The Isis (Oxford), no. 348 (10 November 1906), p. 67.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. Haldane’s Scheme for a Reserve of Officers’, The Times, no. 38,641 (9 May 1908), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. A.R. Kirby’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,324 (14 November 1916), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘In Memoriam: Capt. Alister G. Kirby’, The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,607 (2 April 1917), p. 204.

[Anon.], ‘An Oxford Rowing “Blue”’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,443 (3 April 1917), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Rowing: The Late Capt. A.G. Kirby’, The Field: The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper, 129, no. 3,354 (7 April 1917), p. 505.

H[arcourt] G[ilbey] Gold, ‘Rowing: The Late Capt. A.G. Kirby: An Appreciation’, Ibid., 129, no. 3,355 (14 April 1917), pp. 532–3.

[Thomas Herbert Warren], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice’, The Oxford Magazine, 35, no. 17 (4 May 1917), p. 229.

The History of the London Rifle Brigade (1921), pp. 63–79, 318 and 323.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 29, 40–2, 107, 114, 135.

Hutchins (1993), pp. 26–31, 33, 37, and plates 14, 16, 18.

Mitchinson (1995), pp. 42–5.

Blandford-Baker (2008), pp. 83, 87, 92, 96–8, 105, 109, 111.

McCrery (2017), pp. 43, 47, 55–6, 111, 121, 151, 153–7, 180.

Archival sources:

MCA: 04/A1/1 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1888–1907]), pp. 434, 448–9, 459, 461, 464–5, 476–7, 484.

MCA: 04/A1/2 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1907–26]), unpag.

OUA: UR 2/1/57.

ADM337/93/489.

AIR76/278/88.

WO95/1498.

WO374/39859.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘Robert Bourne (politician)’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Bourne_(politician) (accessed 7 July 2019).

Wikipedia, ‘List of Oxford University Boat Race crews’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Oxford_University_Boat_Race_crews (accessed 7 July 2019).