Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born: 25 September 1881

Died: 1 April 1918

Regiment: Royal West Surrey Regiment

Grave/Memorial: Cairo War Memorial Cemetery: O.143

Family background

b. 25 September 1881. Eldest son of Charles Durant Hodgson (1853–1920) and Emily Hodgson (née Godwin-Austen) (1849–1947) (m. 1880). In 1881 Charles and Emily Hodgson were living at Cottingley House, Norbiton, Surrey, one mile east of Kingston-upon-Thames (four servants) and by November 1885, they were living at Darbinsbrook, Shamley Green. But by the time of the 1891 Census, the family had moved to Cottingley House, Kingston Vale (Coombe Kingston), Surrey, London SW15, very near Wimbledon Common (seven servants including a butler). In 1895 the family moved to The Hallams, Littleford Lane, Shamley Green, Guildford, Surrey – a mock Tudor country house with 25 rooms that had been specially designed for Charles Durant in 1894/95 by Richard Norman Shaw (1831–1912), a Scottish architect who was particularly well-known for his country houses. At the time of the 1901 Census the family employed seven servants including a butler, but by the time of the 1911 Census the number of servants had gone down to six; Charles Durant died there in August 1920.

Parents and antecedents

By 1881, Charles Durant had become a Captain in the 2nd Royal Surrey Militia, whose history goes back to 1758, and then, as a result of Cardwell’s and Haldane’s reforms, he became a Captain in the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. As a young man in his thirties, Charles Durant had political ambitions and in December 1885 stood as the Liberal candidate for the Kingston-on-Thames Division of Surrey that had been created by the Redistribution of Seats Act (25 June 1885), bringing with it 6,000 new votes in Kingston, Richmond, Petersham, Mortlake and Barnes. He lost by 3,206 to 4,915 votes to the Conservative candidate Sir John Whittaker Ellis (later the 1st Baronet of Byfleet and Hertford St) (1829–1912), who had been the Lord Mayor of London 1881–82 and represented the Division from 1885 to 1892. In July 1886 he stood for a second time, this time in the mid-Buckinghamshire (Aylesbury) by-election, against the Liberal Unionist candidate and banker Baron Ferdinand James de Rothschild (1839–98) and lost by 1,680 to 4,723 votes, allowing de Rothschild to represent the constituency until 1898. And in 1892 he contested the Kingston-on-Thames seat for a second time, but lost once again, albeit by a smaller margin (4,357 to 5,100 votes), to the Conservative candidate and former colonial administrator Sir Richard Carnac Temple (1st Baronet) (1826–1902; MP 1892–95).

In 1854, Hodgson’s paternal grandfather, William Frederic Hodgson (1811–75) bought the Kingston Brewery (founded c.1610) and its 90 tied public houses from Charles Rowlls (1791–1868). The brewery stood near the river in Brook Street, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, and had been owned by the Rowlls family during the first half of the nineteenth century. After Frederic’s death, he was succeeded by his two sons William Sanford (1841–92) and Charles Durant (see above), and by 1886 the company, now called Hodgson Brothers, was valued at something over £300,000. In 1903, the company acquired Fricker’s Eagle Brewery, Kingston-upon-Thames, and 38 tied public houses, and in 1929 it acquired F.A. Crooke & Co. Ltd, Guildford, and 36 more tied public houses. In 1943 the London brewery firm Courage & Co. bought Hodgson’s Brewery and it ceased brewing in 1965 – another victim of the mass production of beer and the industrialization of the brewing process that gave birth to the Campaign for Real Ale in 1971. The success of the Kingston Brewery meant that Charles Durant was able to live the life of a leisured gentleman by 1891 at the latest. On his death he left £87,094 0s. 4d.

The Hodgson Brothers Brewery in Brook St, Kingston-upon-Thames; the building in the background also features in the picture immediately below

A delivery van belonging to the Hodgson Brothers Brewery in Brook St, Kingston-upon-Thames (1914) (by kind permission of the Kingston-upon-Thames Museums and Heritage Service, courtesy of Alex Beard Esq.)

Charles Durant’s mother, Jane Durant Hodgson (née Sanford; 1811–41), was William Frederic Hodgson’s second wife, whom he married in 1841 after the death of his first wife, Anne Wilkinson (1805–40; m. 1839). As well as his brother William Sanford, Charles Durant had three sisters: Emily Durant (1843–1903), Jane Durant (1845–1915) and Louisa (b. 1847).

Charles Durant’s wife, Emily, was the youngest daughter of Robert Alfred Cloyne Godwin-Austen, FRS, DL (1808–84), a distinguished geologist, and her eldest brother was the explorer Henry Haversham Godwin-Austen, who was particularly well-known for his work on the geology and zoology of India. Emily left £13,007 13s. 3d. when she died, aged 98.

Robert Alfred Cloyne Godwin-Austen, FRS, DL

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Cyril Arthur Godwin (1883–1918); he died in Cairo of pneumonia, aged 33, on 20 March 1918 while serving as a Lieutenant in the 16th Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Devonshire Regiment;

(2) Harold Edwin Austen (1884–1965); married (1923) Catherine Phyllis Champneys (1899–1942), two sons; and then (1947) Eileen Mary Drew (née Robina) (1893–1991);

(3) Noel Emily Beatrice (b. 1886, d. 1967 in Dumfries, Scotland); later Charteris after her marriage in 1913 to Brigadier John Charteris, DSO, RE (1877–1946); three sons.

Hodgson’s younger brother Cyril Arthur was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he read for an Ordinary Degree in Mechanism and Applied Mechanics and was awarded a 2nd in December 1904. He then trained as a land agent, gaining practical experience by working in Lewes, Sussex, and Dulverton, West Somerset, and passed the examination of the Surveyors’ Institute. On the outbreak of war he was working on the Stratfield-Saye Estate, Hampshire, which had belonged to the Dukes of Wellington since 1817.

Before the war, Cyril Arthur had joined the Royal North Devon Yeomanry as a Trooper when he was working in Dulverton, on the Somerset–Devon border, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant in about June 1913. The Regiment was a Light Cavalry Regiment (Territorial Force), in which Duncan Mackinnon was also serving as a subaltern. Although Cyril Arthur resigned his commission on the outbreak of war and was discharged from the Regiment, on 5 August 1914 he attested and eight days later applied for a Territorial Commission, only to be reinstated in his old Regiment. Once mobilized, the 1/1st Royal North Devon Yeomanry, as part of the 2nd South-West Mounted Brigade, was sent almost immediately to the Colchester area, where it acted as a home defence unit near Clacton until September 1915, when it became a Dismounted Regiment in the 13th Division. On 22/23 September the Regiment left Clacton, travelled by train to Liverpool, and sailed for Gallipoli aboard HMTS 2810 on 24 September 1915. It landed first at the port of Mudros, on the Greek island of Lemnos, on 2 October, and then, in very hot weather, it was transferred to Suvla Bay, on the Gallipoli Peninsula itself, on the evening of 8 October. On 9 October the Regiment went into Reserve dug-outs west of Karakal Dagh, a hill in the Kiretch Tepe range, north-east of Suvla Point, where the men spent 10 October improving these. Because of snipers, no fires or cooking were allowed, and if the men wanted warm food, they had to go down to the main beach, where a cook-house had been built next to the sea. The Regiment spent the rest of the month familiarizing itself with the general area and its trench system. It then moved into a tented camp, and the whole Brigade was transferred to the 11th Division, part of IX Corps. There was some shelling and the men spent most of their time in working-parties, improving the trenches and other facilities. Unfortunately, the Hussars immediately began losing more men to disease than to the enemy so that when, on 17 October, their first battle casualty, Major Morland John Greig (b. 1864 in Pennsylvania, d. 1915), was killed by a shell, the unit already numbered 84 cases of severe diarrhoea, one of whom was Mackinnon. The treatment for this affliction was recorded in the Regiment’s War Diary: at first castor oil, then magnesium sulphate, and then, if necessary, half-grain doses of calomel, and finally opium.

On the night of 2/3 November, the Regiment moved into front-line trenches, finding them “sketchy affairs” that were accessible only at night, and although the men established posts and erected barbed wire, casualties from shell-fire began to mount up. On 11 November the Regiment was relieved, and three days later it was transferred to the 2nd Mounted Division. It spent the following two weeks digging trenches at night, but on the night of 26/27 November a violently heavy thunderstorm flooded the Regiment’s trenches “doing great damage”. The War Diary recorded: “The rise of the water was so sudden that a great many kits & equipments were lost, including many officers’ kits”, and the storm was so violent that men were washed away or buried in collapsing dug-outs. On 28 November it was very cold all day; the men were in the open all night; and when a snow blizzard lasted for three days, conditions in the open became so bad that sentries froze on their fire-steps. So the Hussars were relieved a day early, on 29 November, and 30 November was “spent in cleaning up dug-outs – Many men are sick having been subject to 3 days exposure in very severe weather; & having undergone great hardship; many men being completely submerged when the parapet gave way, blankets & waterproof sheets being lost.” 1 December was spent cleaning out the dug-outs, and the Regiment was by now so depleted that it had insufficient men to hold the line, so when it was withdrawn to camp at Lala Baba, a hill on the southern end of Beach ‘A’ on Suvla Bay, it could barely muster 50 men for duties of any kind. By 9 December 1915, the Regiment, which numbered more than 400 men when it arrived on Gallipoli, was down to 195 men and so was moved back into Reserve, where there was still more cleaning up to do. On 10 December 1915 it was ordered to prepare to evacuate, leaving its fittest men holding the line while the rest of the Division withdrew. So on 11 December ten officers and 140 other ranks (ORs) remained while the others moved out; on 12 December all spare ammunition was moved back to Lala Baba and taken off the beach; on 13 December all valises belonging to officers were sent to the beach; and at 19.30 hours on the night of 18/19 December the last remnants of the Regiment were moved from the Reserve trenches at Suvla Bay to ‘C’ Beach, just south of Niebruniessi Point at the southernmost end of Suvla Bay, boarded lighters, and arrived on the island of Imbros at 23.00 hours. They stayed here until 24 December, and although the tents there were very crowded, at least hot meals were available.

HMT Novian at Gallipoli (1915)

On 24 December the remainder of the Regiment embarked on HMT Novian (1914; broken up in January 1934) and enjoyed a Christmas dinner of sorts, with plum pudding supplied by the Lady Davies Fund. Nevertheless, over 50% of the Regiment were by now in hospitals in Alexandria or Malta, suffering mainly from frostbite. On 28 December 1915 the Novian sailed from Mudros and it arrived at Alexandria two days later, where the Regiment disembarked and marched to Ramleh, five miles to the north-east near the Suez Canal. On 1 January 1916 the depleted Regiment – consisting by now of 18 officers and 203 ORs – travelled by truck and tram to a desert camp at Sidi Bishr, now a fashionable coastal suburb of Alexandria, where it stayed until 3 March 1916. In February 1916 the 2nd South-West Mounted Brigade was absorbed into the 2nd Dismounted Brigade and became part of the large and heterogeneous force that was being assembled to defend the Suez Canal against attacks from the west by Senussi tribesmen and from the east by Ottoman forces (see R.N.M. Bailey, J.F. Russell). On 4 March 1916, the Regiment moved to Minya (Minia), a town on the west bank of the Nile about 152 miles south of Cairo, and it stayed here until 19 April when it was transferred to Qara (Gara or Djara) Oasis, in the Western Desert on the northern edge of the Qattara Depression, where the heat was so intense during the daytime that after the Regiment’s arrival there on 21 April, no parades or fatigues took place between 09.00 and 16.00 hours.

On 19 May 1916 Cyril Arthur was gazetted Temporary Lieutenant and on 9 July 1916 he became the Ammunition Officer to the Indian Dismounted Brigade From 13 July to 10 September 1916 Cyril Arthur was out of Egypt for a period of leave in England; on 14 August 1916, he was made Acting Captain; and on his return he became a General Staff Officer (Grade 3) on the Staff of the hastily created Western Frontier Force (WFF) that was commanded by Major-General Alexander Wallace (1858–1922) and had been formed on 11 December 1915 to deal with the two-pronged invasion of Egypt by Turkish-backed Senussi tribesmen from Libya (see the Excursus on Parham contained in E.F.M. Brown and Bailey). The northern prong of that invasion went eastwards along the fertile northern coast of Egypt from Es Sollum towards Alexandria, whilst the southern prong involved an advance through the band of oases that begins about 100 miles west of the Nile. Although the northern threat had caused the evacuation of Sidi Barrani and Es Sollum in November 1915 so that the Allied forces could concentrate near Mersa Matruh, it all but disappeared after the Battle of Agagia on 26 February 1916, when Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Maurice Wellesley Souter (later Brigadier, DSO; b. 1872 in India, d. 1941 in Sydney, Australia) led the Queen’s Own Dorset Yeomanry in a “death-or-glory” charge across open desert against the “fierce and well-equipped Arabs”. This was one of the last charges ever made by a cavalry regiment of the British Army and would later be described as “one of the finest charges since Balaclava”. It routed the northern Senussi and involved the capture, by Colonel Souter himself, of their Turkish Generalissimo Jafar Pasha al-Askari (1887–1936), together with his Staff; it also led directly to the reoccupation of Sidi Barrani and Sollum in the second half of March 1916. The southern threat lasted much longer, however, and the Senussis were not finally defeated until the battle that took place near the Siwa Oasis from 3 to 5 February 1917.

In January 1917, Cyril Arthur passed an Officers’ Training Course in Zeitoun, a district of Egypt, with a mark of 88% – presumably as preparation for his promotion to Captain when, on 4 January 1917, the 2nd Dismounted Brigade became part of the 16th (Royal 1st Devon & Royal North Devon Yeomanry) Battalion (TF), the Devonshire Regiment, at Moascar, Egypt, and thus part of the 229th Brigade in the 74th (Yeomanry) Division. As such, it participated in the Palestine campaign of 1917, during which Cyril Arthur was hospitalized twice – once in July and once in December. But on 9 March 1918, the first day of the Battle of Tell ’Asur (Turmus ’Aya) (8–12 March 1918), Cyril Arthur became dangerously ill with pneumonia and after being taken by train to the Nasrieh Schools Hospital in Cairo (see Bailey), he died there on 20 March 1918, aged 33, just ten days before the death there of his older brother Charles Basil (see below). He is buried in Cairo War Memorial Cemetery, Grave O.135, i.e. eight graves away from that of his older brother. His Colonel recommended him (unsuccessfully) for the MC and wrote of him: “He was one of the most fearless fellows I ever met, in fact cooler in danger than at any other time. His good humour and his good spirits were worth anything in the mess. He is a very great loss.” Cyril Arthur left £5,021 8s. 10d.

Harold Edwin Austen Hodgson (1884–1965)

Harold Edwin Austen was a farmer and already serving in the Militia before the Haldane Reforms took effect, and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on 1 August 1908. He became a member of the Special Reserve of Officers as a Second Lieutenant with effect from 6 September 1908 and was then attached to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Surrey Regiment) and promoted Lieutenant either on 1 December 1911 or in July 1912. He landed in France on 1 January 1915, probably on attachment either to the 1st or the 2nd Battalion of that Regiment, but with effect from 24 November 1915 he was transferred with the rank of Acting Captain to the 1st (Garrison) Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment, which set sail from Devonport to India on the following day. He probably spent the rest of the war on garrison duties in India and was demobilized on 17 October 1919.

Harold Edwin’s second wife, Eileen Mary Drew (née Robina; 1893–1991), was the daughter of Robert Robina (d. before 1901), a man of independent means, and the first wife of Charles Henry Phelp (1890–1931) (m. 1912), marriage dissolved in 1916. In September 1917 she became the second wife of John (“Jack”) Richmond Drew (1890–1950), one son, marriage dissolved in 1937. John Richmond was the son of Henry Drew (1856–1931), a retired banker and a talented accountant who joined the Hudson Bay Company in May 1906 and worked himself up into a senior position by the outbreak of war. John was severely wounded when he lost a hand in an explosion while serving, like Harold Edwin, as a First Lieutenant with the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, but despite that injury he became a devotee of hunting and swimming. During World War Two he served as a Group Officer for the Observer Corps.

Brigadier John Charteris, DSO, CMG

John Charteris was the son of Professor Matthew Charteris (1840–97), of Glasgow University, who held the post there of Regius Professor of Medicine from 1880 to 1887; he was also the nephew of Archibald Charteris (1835–1908), the Professor of Biblical Criticism at the University of Edinburgh from 1868 to 1898 and Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland (1892). From 1884 to 1893 he was a pupil at Merchiston Castle School, Edinburgh, Scotland’s only all-boys boarding school, which sets particular store by rugby, and then attended the Royal Military College (Woolwich) (1893–96), where he trained as an officer of engineers. Before being sent to India in 1905 he was promoted Captain, and from 1907 to 1909 he attended Staff College at Quetta, the provincial capital of Pakistan, where his performance was outstanding. As a result of this, he was made a Staff Captain in 1909 and appointed to the Staff at the HQ of India (1909–10; General Staff Officer, Grade 2, 1910–12), where he became a good friend of General Douglas (later Field-Marshal; 1st Earl) Haig (1861–1928). After a slow start in his career as an officer, Haig had become the youngest Major-General in the British Army (1904), Inspector-General of Cavalry in India (1904–06), Director of Military Training on the General Staff at the War Office (August 1906–November 1907), Director Staff Duties at the War Office (November 1907–1909) and finally the Chief of the Indian General Staff (1909–11). When Haig returned to Britain in December 1911 to become the GOC (General Officer Commanding) of Aldershot Command in March 1912, he took chosen members of his Staff in India back with him, including Charteris, who then served on Haig’s Staff at Aldershot as Assistant Military Secretary to the GOC from 1912 to 1914. When war broke out, Charteris, now a Major, went to France as one of Haig’s Staff Officers, where, from December 1915 to 1918, he served as Haig’s Chief Intelligence Officer with the rank of Brigadier (Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel 1915; DSO 1915; Brevet Colonel 1917). But as time went on, he became more unpopular, both with his peers and Haig’s political masters, partly because of his loud, ebullient, optimistic temperament, partly because his “Black Propaganda” schemes were not well received, and partly because he was not trained in military intelligence. So although he began by showing a competence in this art-form, his professional judgement proved not always to be sound. He was, for instance, over-optimistic about the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917) and the Battle of Cambrai (20 November–7 December 1917). Consequently, in January 1918, Haig was forced to dismiss him after he had seriously annoyed Lord Derby (Edward George Villiers Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby; 1865–1948), the Secretary of State for War from December 1916 to April 1918. So in 1918 he was moved sideways and became the Deputy Director-General of Transportation at Haig’s General Headquarters. In 1921 he was promoted full Colonel and sent back to India where he became the Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General until his retirement in 1922. From 1924 to 1929 he was the Conservative MP for Dumfriesshire, and over the next ten years he published four books, two on Earl Haig.

Two of his and Noel Emily’s three sons became army officers: the youngest, Euan Basil Cyril Charteris (1920–42), was awarded the MC for his part in the Bruneval Raid (Operation Biting), while serving as a Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, Army Air Corps, and was killed in action on 3 December 1942 near Massicault, Tunisia, during a premature attempt to capture Tunis using airborne troops, one of 289 men to be killed, wounded and missing. He is buried in Massicault War Cemetery, Borj el Amir, c.20 miles south-west of Tunis; Grave III.A.20.

Wife

Hodgson’s wife was Mary (“May”) Alice (“Mollie”) Hodgson (née Carpenter) (1881–1948), North Canonry, Salisbury, Wiltshire (m. 1911). They lived first at St Martin’s, Blackheath, Surrey, two-and-a-half miles south-east of Guildford, not far from the family home, and then in 26, Drayton Gardens, Kensington, SW10, at least until the time of Hodgson’s death. Mary Alice was the eldest daughter (of five children) of the Venerable Harry William Carpenter (1854–1936) and Annie Susanna Morton (1853–1929).

Harry William Carpenter graduated from Peterhouse, Cambridge, with a 1st in Mathematics in 1875 (MA 1878) and spent three years as an Assistant Master at Lancing College, Sussex, a High Church Foundation (1848). He was ordained in 1877 and very soon became the Vice-Principal of Sarum (Salisbury) Theological College (1879–80) (so very probably knew A.A. Steward and his father, the Reverend Canon Edward Steward). In 1879 he was made a Minor Canon of Salisbury Cathedral and the Cathedral’s Vicar-General, a post that he held until 1914. In 1892 he became the Cathedral’s Precentor, and in 1911 he was made a Canon and the Prebend of Netherbury-in-Terra in Salisbury Cathedral. In 1914 he became the Archdeacon of Salisbury, a post that he held until his death in 1936. A natural administrator, he held several other offices within and outside of the Diocese: from 1882 to 1914 he was the Chaplain of the Diocesan House of Mercy; from 1889 to 1934 he edited the Diocesan Gazette; from 1896 to 1933 he was the Hon. Secretary of the Diocesan Conference and a member of its Board of Finance; in 1905 he was the Secretary of the Weymouth Church Congress, and from 1914 to 1932 he was the Permanent Honorary Secretary of the Church Congress.

One of Mary Alice’s two brothers, John Philip Morton Carpenter (1893–1916), who had been an agricultural student before the war, was killed in action, aged 23, near Flers, about five miles north-east of Albert, on 15 (not 16) September 1916 while serving as a Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery. This was the opening day of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, when tanks were used in battle for the first time. He was originally buried in “a shell hole by old Battery positions and west of [the] German wire between Longueval and Flers” but is now buried in Bull’s Road Cemetery, Flers, Grave III.L.14. He died intestate but left £680 5s.

John Philip Morton Carpenter (1893–1916)

(From Lancing College War Memorial: http://www.hambo.org/lancing/view_man.php?id=145)

While Hodgson was serving abroad, Mary Alice seems to have stayed in hotels, e.g. the Hotel Prince de Galles, Monte Carlo (1918), the Regina Palace Hotel, Mentone, France, and The Chine Hotel, Boscombe, Bournemouth (September 1918).

Education

Hodgson attended Castle House Preparatory School, Petersfield, Hampshire, from 1891 to 1895 before moving to Eton College from 1895 to 1900, and he matriculated as a Commoner at Magdalen on 14 October 1901, having taken Responsions for the first time in Michaelmas Term 1900. He resat them in Michaelmas Term 1901 and then took the Preliminary Examination in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1902 and the rest of the First Public Examination in October 1902. He was awarded a 2nd in Modern History (Honours) in Trinity Term 1905 and took his BA on 10 August 1905. After leaving Magdalen he became a Barrister of the Inner Temple and was awarded a 3rd for his performance in the paper on Evidence, Procedure and Criminal Law in November 1907. He also worked for Toynbee Hall, founded in 1884 by Canon Samuel Barnett (1844–1913) in Commercial Street, the East End of London. The first university-affiliated institution of the worldwide Settlement Movement, Toynbee Hall aimed to bring about social reform by getting the rich and the poor to live more closely together in an interdependent community (see N.G. Chamberlain).

Charles Basil Mortimer Hodgson, BA

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Military and war service

On 28 May 1906, Hodgson was commissioned Second Lieutenant in a Territorial Battalion, probably one of the several that were connected with his father’s old Regiment, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Surrey Regiment), and in July 1907 he was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion of that regiment. He was still in the 3rd Battalion when he was promoted Lieutenant on 10 August 1908 and Captain on 1 October 1913 (London Gazette, no. 28,791, 9 January 1914, p. 260), and mobilized on 5 August 1914. But the 3rd Battalion soon moved from Guildford, in Surrey, to Chattenden-on-Thames, Kent, and remained in Kent as part of the Special Reserve Brigade for the rest of the war. Hodgson, however, was soon transferred to the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the same Regiment, part of the 3rd (Infantry) Brigade in the 1st Division, which had been mobilized at Bordon Camp on the eastern border of Hampshire as soon as war broke out. The 1st Battalion continued to train and absorb reinforcements at Bordon until 12 August, when it marched to the local railway station to entrain for Southampton, where it embarked on the SS Braemar Castle (1907–20; scrapped). Unfortunately, the 1st Battalion’s original War Diary for the first three months of World War One was lost on 31 October 1914, when the Battalion was nearly wiped out during fierce fighting at Gheluvelt (Geluveld), in the Ypres Salient, and the substitute text that we now have was rewritten on and after 10 November 1914 using the only source that was available – the personal diary of one of the surviving officers, “supplemented from memory”. Consequently, the extant version of the Battalion’s War Diary contains quite a lot of errors, especially where the names of towns and villages are concerned, and they have been corrected in the text that follows.

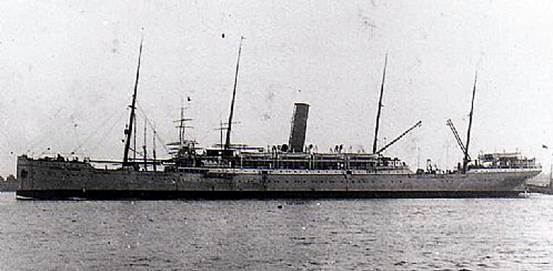

SS Braemar Castle (1907–20)

The 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own landed at Le Havre at 11.00 hrs on 13 August 1914 – but Hodgson was not present, as his medal card indicates that he did not enter France until 24 or 25 September 1914. The Battalion began by marching to Camp No. 6, just outside Le Havre, where it rested for a day before travelling northwards by train to le Nouvion-en-Thiérache, in northern France, from where it marched to the village of Leschelle, just to the south. It trained here for a further five days before route-marching north-north-eastwards for about 27 miles via the village of St-Aubin to Maubeuge, a large fortress town just south of the French frontier with Belgium. The War Diary tersely commented: “This march [was] almost entirely on rough cobble stones and very trying.” The Battalion finally crossed the frontier at about 19.00 hrs on 22 August and spent the night in billets in Croix-lez-Rouveroy, about two miles into Belgium and north-east of Maubeuge. But by the evening of 20 August 1914 seven German Armies had begun their invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg and France – from Antwerp in the north to Épinal in the south – as part of a co-ordinated, multi-pronged advance towards Paris known as the Schlieffen Plan. So on 21 August, in conformity with the agreed plan of extending the French line westwards, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) began to arrive in Mons, in southern Belgium, and by the end of 22 August two Corps (consisting of four infantry Divisions) and a cavalry contingent (consisting of five cavalry Brigades), i.e. c.70,000 men, had arrived in a pear-shaped area straddling the Franco-Belgian border whose central points were the towns of Maubeuge and Mons, ready to advance further into Belgium. But General Charles Lanrezac (1852–1925), who was in overall command of the ten Divisions of the French Fifth Army, had learnt of the arrival of the German Third Army on the exposed right flank of his Army and the imminent fall of the Belgian fortress town of Namur, c.43 miles due east of Mons. So during the night of 22/23 August, he held a difficult meeting with Field-Marshal Sir John French (1852–1925), the Commander of the BEF from August 1914 to December 1915, who promised him that in order to cover the left flank of the French Army, the two British Corps would dig in on the southern bank of the Condé-sur-Lescaut–Mons Canal and hold it for 24 hours.

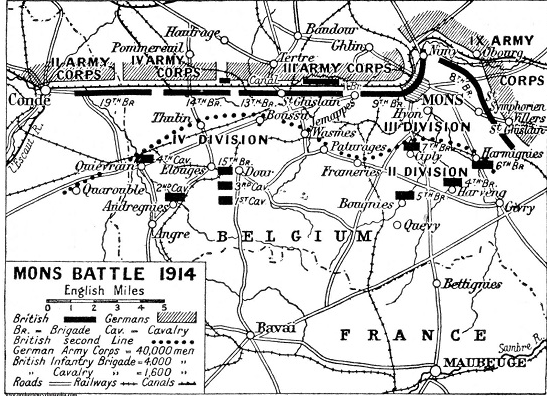

The Canal, which lies on top of the large Bérinage coalfield, runs from Condé-sur-Lescaut in the west, past St-Ghislain (eight miles to the east), to Mons (another nine miles or so to the east), where it loops northwards through the suburb of Nimy and then south-eastwards before continuing further to the east and passing a few miles north of the town of Binches (about eight miles). It is represented near the top of the map (below) by the serrated line. Of the two British Corps, II Corps, consisting of the 3rd and 5th Divisions and commanded since 21 August 1914 by Lieutenant-General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (1858–1930), occupied the left-hand (western) section of the line, while I Corps, consisting of the 1st and 2nd Divisions and commanded since the outbreak of war by Lieutenant-General (Field-Marshal from late 1916) Sir Douglas Haig (1861–1928), occupied the right-hand (eastern) section of the line. But whereas II Corps was positioned along the Canal, with the 5th Division on the left and the 3rd Division on the right in the Nimy Salient, I Corps was positioned almost at right-angles to the Canal athwart the main road that runs south-eastwards from Mons to Beaumont (now the N40). The front line of I Corps extended south-south-west for about 6 miles as far as the village of Givry so that it could help to protect both the British right and the French left if the attacking Germans managed to drive a wedge between II Corps and the adjacent French Fifth Army and seemed to be threatening them with encirclement either from the east or the west. So at 09.00 hrs on 23 August, in fine sunny weather and after a preliminary bombardment, the German First Army (von Kluck) made II Corps the focus of its assault, with the Nimy Salient, where the Canal is crossed by three road bridges and one railway bridge, the Schwerpunkt of that assault. Whilst in the east, the German Second Army (von Bülow) concentrated its attack on the French Fifth Army, leaving Haig’s I Corps – of which Hodgson’s Battalion was part – largely out of the fighting. But as the pressure of the German assault on the Canal made Field-Marshal French realize the danger of his own overall situation, he ordered the two British Corps to begin a general withdrawal southwards at midnight on 23 August.

The Battle of Mons (21–24 August 1914). NB: II, IV, III and IX Corps were all part of the German First Army and no elements of the German Second and Third Armies have been located on this map. Nor have the British 1st and 5th Divisions been located here. The map does, however, mark the British 4th Division, even though it did not land in France until 22 August; it seems to have been located where the British 5th Division ought to be.

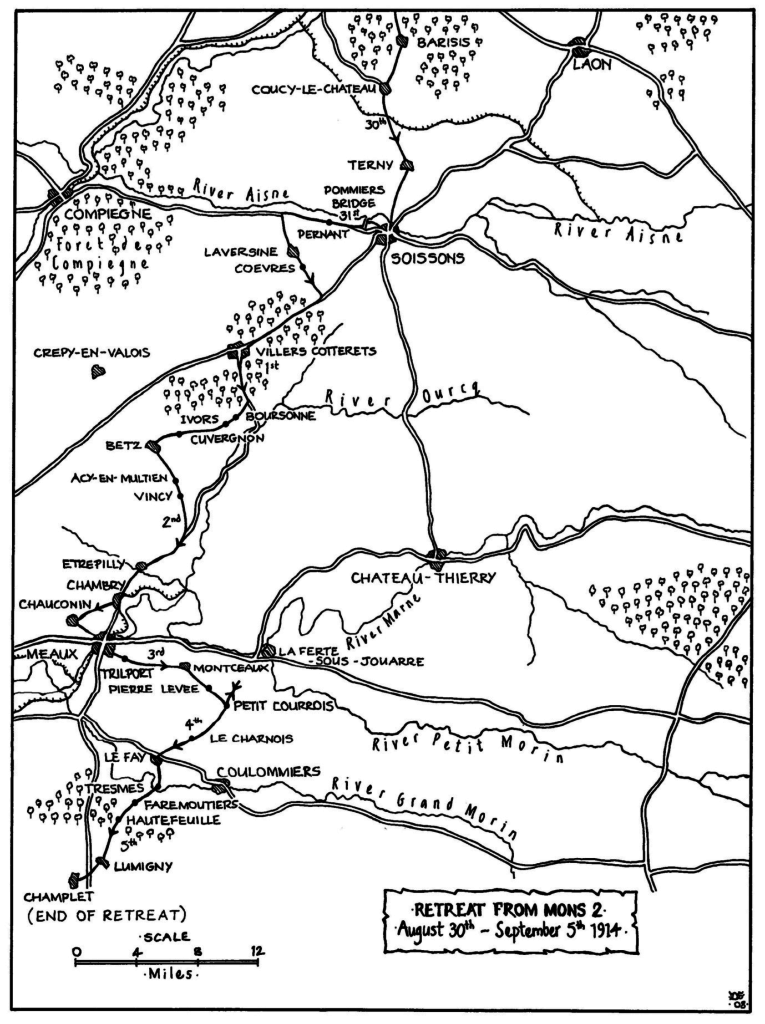

But while the Battle of Mons was developing during the morning of 23 August, at 05.00 hours the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own began to dig itself into defensive positions on a ridge to the north of Croix-lez-Rouveroy. Consequently, on the following day, it was able to cover the 3rd Brigade’s retreat from Mons before starting its own withdrawal at 19.45 hours south-westwards through Bettignies to Neuf-Mesnil, a western suburb of Maubeuge. On 25 August the 1st Battalion continued to withdraw south-westwards via St-Rémy-du-Nord, Dompierre-sur-Helpe and Marbaix to the village of Grand-Fayt, a distance of 12 miles which the War Diary described as “the worst march upto date”. Then, on 26 August, the Battalion narrowly missed the Battle of Cateau-Cambrésis, when the BEF suffered heavy casualties, losing 7,812 men killed, wounded and missing, including 2,600 taken prisoner, and 38 artillery pieces. After setting off from Grand-Fayt at 01.00 hrs, the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own marched westwards for two miles to the village of le Favil, where it reinforced the 4th Brigade of Guards by digging in opposite the nearby village of Landrecies. But at 14.00 hrs it set off southwards down what is now the D934, marched for eight miles through la Groise, and spent the night at Oisy, about five miles away. On 27 August the Battalion set off at 10.45 hours in heavy rain, marched almost continually for 27 miles via the crossroads town of Guise, where it veered south-westwards, and spent the night at Bernot, a village on the River Sambre. The march recommenced at 13.00 hrs on 28 August, when the 1st Battalion just escaped being shelled, and during the next sixteen-and-a-half hours it covered 32 miles southwards along the River Sambre, with only two-and-a-half hours’ rest during the afternoon. The following day was spent resting in billets until 17.00 hrs, when the 1st Battalion withdrew a little way to the village of Bertaucourt-Epourdon, where it rejoined the 3rd Brigade and spent the night in bivouacs. At 14.30 hrs on 30 August the Battalion set off once more and marched through St-Gobain and Septvaux until they reached Brancourt-en-Laonnais where the men were billeted for the night. Although the distance involved was not that great, the Battalion War Diary regarded the march as “the most trying of the whole retreat” because most of it “was carried out with two Battalions and Transport abreast on the road”. On 31 August the Battalion set off at 05.40 hrs and marched ten miles south-south-westwards to Soissons, followed by a further five miles along the same line of march to the village of Missy-aux-Bois, where it camped in a field and whence it departed at 08.15 hours on the following morning to march the ten miles to Villers-Cotterêts. Here they rested at the railway station for one-and-a-half hours and received a report that German cavalry units had been seen ten miles to the north-west. The 1st Battalion then turned due south, marched five miles to la Ferté-Villon, and spent the night here in bivouacs before marching 18 miles on the following day via Varreddes on the River Marne to Penchard, a suburb of Meaux that was 39 miles from the centre of Paris. But on 3 September the 1st Battalion, like the rest of the 3rd Brigade, turned due east and marched along the River Marne to the town of Sammaron, where one Company was left to guard the bridge over the Marne while the rest of the Battalion advanced a few miles and bivouacked at Perreuse. On 4 September the 1st Battalion left its camp at 07.00 hours and marched due south for ten miles to Aulnoy and Mouroux, two small villages to the north of the crossroads town of Coulommiers, on the Grand Morin river. And when, in the late afternoon/early evening, the entire 2nd Division fell back southwards, the 3rd Brigade acted as its rearguard, and on 5 September it continued to cover the 2nd Division’s withdrawal south-westwards via Maupertuis and the tiny village of Ormeaux to Rozay-en-Brie. This time, the 1st Battalion was the column’s rearguard once more, collecting stragglers as it went along, and on that day, too, 90 men – its first batch of reinforcements – arrived.

The second part of the retreat from Mons (30 August–5 September 1914) (Courtesy of Simon Harris Esq.)

The Allied advance against the retreating Germans began on 6 September 1914 – the opening day of the Battle of the Marne (6–10 September 1914) – and at 07.00 hours the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own moved eastwards, to the village of Vaudoy-en-Brie, which was taken without opposition. On 7 September the advance continued at 07.00 hrs, north-eastwards through Dagny and Chevru to Coffery, where the 1st Battalion bivouacked for the night, albeit without supplies of water. On the following morning the Battalion set out through nearby Choisy-en-Brie at 05.30 hours, crossed the Grand Morin river, and reached Jouy-sur-Morin, where they took up positions in order to cover the Guards Brigade as they crossed the river. The 1st Battalion then made a dog-leg through Champ Martin and Grand Marché to Hondevilliers, about five miles to the north, where it reinforced the 2nd Brigade, which had seen action up on the ridge, but too late to take part in the action themselves. The 1st Battalion also received a second batch of reinforcements there, consisting of another 90 or so men. On 9 September the 3rd Brigade moved off at 05.00 hours through Basse Velle and Saulchery, where it crossed the Marne by a bridge. While the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Gloucestershire Regiment provided cover, the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own went across first, followed by two of the other three Battalions with which it was brigaded: the 2nd (Regular) Battalion, the Welch Regiment and the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the South Wales Borderers. But there was no opposition and once across, the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own marched about four miles north-eastwards to Bonneil, a few miles south of Château-Thierry, where it established new positions. At 08.00 hours on 10 September, the last day of the Battle of the Marne, the 3rd Brigade set off north-westwards to reach the crossroads village of Priez. But after about seven miles, near the village of Courchamps, the 2nd Brigade, which was now leading the advancing British column, made contact with the German rearguard and took heavy casualties (see also G.M.R. Turbutt). But once at Priez, the British column turned sharp right and continued to nearby Sommelans, where it bivouacked for the night. At 04.45 hours on 11 September the Brigade continued its march east-north-east to Villeneuve-sur-Fère for c.11 miles, and on 12 September, the first day of the First Battle of the Aisne (12–28 September 1914), the Brigade began by marching to Fère-en-Tardenois, where it turned northwards and advanced via Bruys and Bazoche-sur-Vesles to Vauxcéré, where it arrived at 20.00 hours, having covered a total distance of c.17 miles. During the day, a retreating German column had been about one-and-a-half hours in front of the British Brigade on the same road, and the French artillery took advantage of the situation by shelling the Germans from both flanks over the heads of the British Battalion: luckily the latter suffered no casualties.

Vauxcéré was about four-and-a-half miles south of the River Aisne and on the following day the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own rested in billets all morning before crossing the river in the afternoon, with the weather worsening significantly, by the bridge at Bourg-et-Comin. The British Sector of the Aisne stretched from the city of Soissons in the west to the village of Villers-en-Prayères, c.14 miles east of Soissons and less than a mile east of Bourg-et-Comin, and on 13 September, with the French on their right, the BEF began to cross the Aisne in force along the entire length of the Sector. So it happened that the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own were making the crossing just four miles east of where Turbutt’s 2nd (Regular) Battalion of the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (part of the 5th Brigade in the Second Division) were doing the same at Pont-Arcy. On 14 September the 1st Battalion advanced around three miles up the steep, wood-covered, northern bank of the Aisne towards the road along the 19-mile-long ridge known as Le Chemin des Dames. It ran parallel with the river and the French had recaptured its western end from the Germans on the previous day. The 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own advanced to Paissy, about a mile south of the Chemin des Dames, and was deployed to the north-east of the village; it then advanced in extended lines of platoons with ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies in the firing line and ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies in support. No serious opposition was encountered before arriving at the road, but when the Battalion crossed the road and pushed forward c.400–500 yards, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies on the left ran into heavy rifle and machine-gun fire from the Germans, who were advancing towards the French positions, and began taking numerous casualties at a range of 1,100 yards. At 15.00 hours the Queen’s Own Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Dawson Warren (1865–1914), ordered his men to attack the German right flank, but this was not possible because of the strength of the enemy and the French withdrawal to the road. Whereupon the Germans launched a more serious attack on ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies on the British right and at 16.30 hours the 1st Battalion, too, was ordered back to the road, where the men lay 50 yards in front of the British artillery under heavy German fire until darkness. The Battalion’s first taste of serious action had cost it 1 officer and 13 ORs killed, 9 officers and 88 ORs wounded, and 39 ORs missing – a total of 150 casualties.

From 15 to 19 September 1914 the Battalion stayed near the Chemin des Dames, but improved its defences and during the first two days took far fewer casualties. But on 17 September the German shelling intensified and the French on the right of the Battalion withdrew, causing severe casualties in ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies when they moved up to fill the gap (2 officers and 60 ORs killed, one of whom was Lieutenant-Colonel Warren, aged 41 (buried in Paissy churchyard), and 1 officer and 48 ORs wounded – a total of 111 casualties). Despite a similar amount of shelling on 18 September, casualties dropped by 50% (6 ORs killed, 1 officer and 48 ORs wounded, and 16 ORs missing – a total of 55 casualties), except in one platoon “where the trenches had not been deepened through lack of time”. On 19 September the Germans attacked at 01.00 hours in a “blinding rainstorm” but were repulsed; and at 03.00 hours the Battalion was relieved by the 1st (Regular) Battalion of the Coldstream Guards and withdrew a couple of miles south-eastwards to Vendresse-Beaulne, two miles above Bourg-et-Comin, where the survivors rejoined the 3rd Brigade and supported the 2nd Battalion of the Welch Regiment. From 20 to 26 September the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own was still in or near the trenches at Vendresse-Beaulne, supporting elements of the 18th Brigade (part of the newly arrived 6th Division), relieving units in the trenches, absorbing a much-needed reinforcement of two officers and 197 ORs, driving back a German night attack, and taking a total of 46 casualties (killed and wounded), mainly because of snipers and “friendly fire”, when, on two to three occasions, British shells landed short. At 22.00 hrs on 27 September, the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own was relieved once more by the 1st Battalion, the Coldstream Guards and withdrew to a village which the War Diary calls Deuilly but which is probably Dhuizel, about two miles south-west of Bourg-et-Comin (see also Turbutt), as there is no village in France is called Deuilly. The Battle of the Aisne ended on 28 September and the 1st Battalion of the Queen’s Own became part of Corps Reserve. But on 1 October it was sent back across the Aisne to the trenches near the village of Moussy-Verneuil, two miles above Bourg-et-Comin and just below the Chemin des Dames, where it stayed until 16 October 1914, experiencing the occasional attack by the Germans and taking a steady stream of casualties. It was here, at 01.00 hours on 9 October, that the Battalion was reinforced to compensate for its recent losses by 39 ORs and ten officers, one of whom was Hodgson.

The Battalion was relieved by the French at 02.15 hours on 16 October 1914 and began to take part in the so-called “March to the Sea” – the attempt by the Allies (in competition with the Germans) to move the Schwerpunkt of the fighting on the Western Front to north-eastern France and the area around Ypres in Belgium in order to deny their enemy access to the all-important Channel ports. So at 01.15 hrs on the following day, a month after the “Race” had started, the 3rd Brigade set off, under conditions of strict secrecy and sheltered by the darkness from German reconnaissance aircraft, to march the c.19 miles southwards via Loupeigne to Fère-en-Tardenois. It entrained here at 11.15 hours, set off for an unknown final destination, and arrived at Paris at 16.00 hours, from where it continued its journey northwards on 18 October and arrived at Hazebrouck, not far from the Franco-Belgian border in north-eastern France, at 10.50 hours. The 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own then marched to Cassel, immediately below the border, continued to billet in nearby Hondeghem, where the men rested throughout the following day, the opening day of the First Battle of Ypres (19 October–30 November 1914).

At 05.50 hours on 20 October 1914 the Battalion marched to Elverdinghe, about three miles north-west of Ypres, and at 02.45 hours on 21 October the 3rd Brigade, acting as the advance guard of the entire Division, marched east-north-east through Boesinghe to the front line at Langemarck, where it deployed to the north-east of the village and came under heavy fire (see also Turbutt). As a result, it lost 3 officers wounded, 13 ORs killed, 68 ORs wounded, and 6 ORs missing – a total of 90 casualties on its first day of action in the Ypres Salient – and had to withdraw to bivouacs in a field some 400 yards south-west of Langemarck. At 05.30 hours on 22 October the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own dug in on the south side of the nearby railway, facing north-west, and at 15.00 hours on the same day the Germans attacked the 1st Brigade, which was mainly dug in north of the railway, and for a while broke into its front line. But its supporting units recaptured the trenches and at 11.15 hours the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own was ordered to advance some 1,500 yards under heavy German artillery fire. One of its platoons rushed the objective and released 50 British prisoners and captured 60 Germans. So at 12 noon a general advance of the British line was ordered, during which c.200 German prisoners were taken and many wounded were picked up, and as a result the British finally managed to reoccupy their old line of trenches north of the main road. But the Germans kept them pinned down throughout the afternoon and attacked at 18.00 hours, when they also brought up a machine-gun with which they enfiladed one of the British trenches, enabling them to capture part of their line. The situation then became confused and by the time the confusion was sorted out, 3 officers had been wounded, 16 ORs had been killed, 35 ORs had been wounded, and 89 ORs were missing. Hodgson was one of the officer casualties, having sprained an ankle, and was invalided back to England, thereby missing the Battle of Gheluvelt (Geluveld) on 31 October that represented “the supreme effort of the enemy to break through to Ypres” on a frontage of 12 miles along the road running from Ypres to Menin (Menen). The German attack was “preceded by a bombardment which, in point of violence, threw into the shade everything which the campaign had yet witnessed. [… It] commenced at daybreak, and gradually increased in volume up to eleven o’clock, when it ceased and the infantry attack commenced”. According to Lord Ernest Hamilton, the German tactics almost always took the same form:

All the batteries within the area would concentrate on the road and on the trenches immediately to [the] right and left of the road, making these positions absolutely untenable. Then, when the troops in the track of the shell-fire had fallen back dazed into semi-unconsciousness by the inferno, they would drive a dense mass of infantry into the gap, and so enfilade – and very often surround – the trenches which were still occupied to [the] right and left of the gap. By this method, companies, and sometimes whole battalions, which had stuck out the shell-fire, were overwhelmed and annihilated.

This description explains why the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own lost so heavily during the Battle – 9 officers and 624 ORs killed, wounded and missing – and why, on 8 November 1914, the survivors were transferred out of the 1st Division to become I Corps Troops. Although the Battle caused the Allies to lose their grip on Gheluvelt decisively, the Germans did not win it in any final sense either, since, to cite Hamilton: “[They] did not carry their advance beyond Gheluvelt. The ground they had gained had only been won by a prodigious expenditure of ammunition, followed by a reckless sacrifice of men, and their losses had been enormous.” More recently, Dr Spencer Jones admirably pin-pointed the significance of the battle when he described it as a “watershed”, a “transition point between the mobile, open warfare of August and September 1914 and the trench deadlock that would characterise the fighting between 1915 and 1917.”

During Hodgson’s convalescence in England, he spoke in various parts of the country on behalf of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee. On 22 February 1915 he was appointed Deputy Judge Advocate General on Sir Ian Hamilton’s Staff of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and he probably arrived on the Greek Island of Imbros in March/April 1915, where he worked under the Australian Brigadier-General (later Major-General Sir) Edward Mabbott Woodward (1861–1943), the Deputy Adjutant-General. But on 24 August 1915 he was hospitalized on the Dardanelles with enteritis (para-typhoid) and invalided out to Alexandria, Egypt, on 30 August 1915 where, on 20 September 1915, he was judged to be fit for light duties. He returned to duty on 10 October 1915 – this time at the HQ of the MEF, and worked as a Cypher Officer at Matruh with the Western Frontier Force (WFF; see above) from 20 November to 31 December 1915. From 1 January to 31 March 1916 he was promoted Staff Captain and became a General Staff Officer (Grade 3) on 1 April 1916. From 28 May to 26 June 1916 he was in England on leave and rejoined from England on 17 July 1916, after which he seems to have worked as a Staff Officer in Cairo at the HQ of WFF. During his time as a Staff Officer, his work earned him the Croix de Guerre (France) avec Palme & Légion d’Honneur on 21 May 1917, and two mentions in dispatches (London Gazette: no. 29,632, 20 June 1916, p. 6,189; no. 30,169, 6 July 1917, p. 6,764). But on 26 February 1918 he was transferred from the Queen’s Own (Royal West Surrey) Regiment and attached to the 2/24th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (The Queen’s), which had arrived in Salonika in November 1916 and in Egypt in early January 1917, having become by then the Territorial Force Battalion of the Queen’s Own Regiment and part of the 181st Brigade, in the 60th (2/2nd London) Division (see also T.H. Helme).

The 60th Division had taken part in the advance through the northern Sinai Desert, the capture of Gaza and Beersheba, and the advance north-westwards up the Mediterranean coast which culminated in the surrender of Jerusalem on 9 December 1917 and General Allenby’s entry there through the Jaffa Gate on 11 December – to a rapturous reception by the local population. By the end of the year, Allenby had succeeded in creating an extended front line around Jerusalem at a distance from the City itself of about three miles, but realized that this was not a broad enough base from which to advance eastwards across the Jordan and then northwards towards Baghdad. And as he had also begun to fear an artillery bombardment of the City and/or a major counter-attack by the Turks, he decided to secure Jerusalem by moving the entire front line outwards by six to eight miles. Once all the necessary objectives had been taken (in three/four days of fierce fighting: 25–28 December 1917), Allenby turned his attention to the capture of Jericho, c.16 miles east-north-east of Jerusalem. One of his first moves was, on 31 December 1917, to order the 53rd and the 60th Divisions to exchange locations, thereby bringing the latter Division to the east of Jerusalem and the right wing of the front line where they could defend the City from the east and the north-east. As a result, the Allied troops around Jerusalem were able to spend most of January resting, reorganizing, training, patrolling, doing very necessary work on sanitary and medical facilities, and visiting biblical sites. But at the beginning of February, Allenby started preparing his Army for an assault on Jericho which would have the effect of forcing the eastern half of the defeated Turkish Army to leave its front line – which ran north–south about eight miles away from Jerusalem – and withdraw east of the River Jordan.

The assault began during the night of 18/19 February and involved a difficult advance though very rough and rugged terrain. So by the time the battle ended on 21 February, when two Mounted Brigades of the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Division took Jericho, and a new Allied front line was established along the cliffs overlooking the Jordan Valley, it had cost the Allies 421 casualties killed, wounded and missing. So as the 181st Brigade, as part of the 60th Division, had been heavily involved in the fighting right from the start, Hodgson probably joined the 2/24th Battalion shortly after this victory – possibly as a replacement officer for one of its casualties. The rest of February was quiet, but on 1 March 1918 the Allies made a careful reconnaissance of the area between Jericho and the River Jordan in preparation for another attack, and four days later some Allied units received “tin hats” – shrapnel helmets – i.e. about a year after they had been issued on the Western Front. The Allied advance, which came to be known as the Battle of Tell ’Asur (Turmus ’Aya) and lasted from 8 to 12 March 1918, began at the eastern end (right flank) of the Palestine Front during the night of 8/9 March 1918, when Chetwode’s XX Corps (on the right, straddling the Jerusalem to Nablus road) and Bulfin’s XXI Corps (on the left, spread out over a greater area in the Judaean Hills and the western coastal plain) advanced northwards and north-eastwards respectively towards Nablus and Tul Karm against the 7th and 8th Turkish Armies.

Although the War Diary of the 2/24th Battalion – part of the 181st Brigade in the 60th Division, both in XX Corps – does not mention Hodgson anywhere by name, let alone the day on which he joined the Battalion, he must have been one of its 49 members to be killed in action or wounded on 9 March 1918 during the fighting for the mountain village of Abu Tellul. On 5 March, in very bad weather, the Battalion had moved to the village of Talaat ed Dumm, where it trained and worked on improving the road to Jericho; and two days later, on 7 March, it had moved to Talaat es Sultan, near Jericho. Then, with very little warning, all four Battalions of the 181st Brigade were taken out of Divisional Reserve on the evening of 8 March, ordered to help clear the El Madhbeh (Al Madhbah) Ridge on the following day, and capture the enemy positions at the villages of Khurbet-el-Beiyudet (2/21st and 2/22nd Battalions) and Abu Tellul (Tulul, Tellal) (2/24th Battalion), both north of the Wadi Aujah (Auja), which flowed from west to east into the River Jordan and thence c.12 miles southwards into the Dead Sea.

So during the night of 8/9 March, the first night of the Battle of Tell ’Asur (8–12 March 1918), the above three Battalions, with the 2/23rd Battalion in Reserve, set off across “exceedingly difficult” country that consisted of high rocky ridges intersected by deep valleys. But by 05.00 hours on 9 March, the 2/24th Battalion was held up near Wadi Sabat as it was unable to find its way across the now swollen river in the dark, thereby causing the 2/22nd Battalion to be held up too, because of defilading fire from Abu Tellul. Although El Madhbeh was captured by 07.30 hours and Hodgson’s 2/24th Battalion had succeeded in crossing the Wadi Aujah by the same time, the Battalion’s advance stalled for a second time because of heavy machine-gun fire. So a bombardment of the village was called down for 07.45 hours and a second bombardment began at 12.30 hours. But once a Company of the 2/24th Battalion had managed to gain a foothold on the south-east summit of the Abu Tellul hill, the Brigade provided more reinforcements and the Turkish positions were taken at 14.30 hours despite heavy enemy fire. But Hodgson had been seriously wounded in his left foot, abdomen, pelvis and buttock, and after being taken by train to the Nasrieh Schools Hospital in Cairo (see Bailey), he died there on 1 April 1918 of wounds received in action, aged 37, just ten days after the death there of his younger brother Cyril Arthur (see above). He is buried in Cairo War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt, Grave O.143, i.e. eight graves away from that of his younger brother. The inscription reads: “In loving memory of my darling husband, rest in peace beloved.” Charles Basil and his brother Cyril Arthur are commemorated on three stained glass windows in Christ Church, Sharmley Green, near Guildford, Surrey; on Blackheath War Memorial, Surrey; on Wonersh War Memorial, the Church of St John the Baptist, Surrey; and on a framed notice board and plaque at St Martin’s Church, Blackheath, Surrey. The wooden crosses that originally marked the graves of both Hodgson and John Carpenter, his brother-in-law, have hung on the walls of Salisbury Cathedral, but Hodgson’s is now affixed to an outside wall of Christ Church, Sharmley Green.

By the time that the fighting ended on 12 March 1918, Allenby’s troops, who had advanced over, had managed to push the 14–26-mile-wide Turkish front between five and seven miles northwards. On 26 May 1918, the 2/24th Battalion left the Egyptian Expeditionary Force and was transferred to France, where it arrived on 15 July 1918 as part of the 198th Brigade in the 66th Division. Charles Basil left £7,125 8s 7d.

Cairo War Memorial Cemetery; Grave 0.143

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; © The War Graves Photographic Project)

Cairo War Memorial Cemetery

(Photo courtesy of Mr Steve Rogers; © The War Graves Photographic Project)

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Surrey’, The Times, no. 31,594 (3 November 1885), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Hodgson, C.D. (Kingston Division)’ [biographical details] The Times, no. 31,618 (1 December 1885), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Surrey’, The Times, no.31,622 (5 December 1885), p. 6.

Hamilton (1916), pp. 259–75.

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant-Colonel John Charteris’ [notice], The Times, no. 41,076, (29 January 1916), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Charles Basil Mortimer Hodgson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,761 (11 April 1918), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Cyril Arthur Godwin, Hodgson’ [obituary], ibid.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Charles Basil Mortimer Hodgson’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,763 (13 April 1918), p. 4.

[Anon.], ‘Mr Charles Durant Hodgson’ [obituary], Surrey Mirror, no. 4,220 (20 August 1920), p. 8.

Dalbiac (1927), pp. 163–213.

[Anon.], ‘The Ven. H.W. Carpenter’ [obituary], The Times, no. 47,433 (22 July 1936), p. 18.

[Anon.], ‘Brig.-General J. Charteris’, The Times, no. 50,368 (5 February 1946), p. 6.

Nikolaus Pevsner and Ian Nairn, The Buildings of England: Surrey (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1971), p. 295.

Lesley Richmond and Alison Turton (eds), The Brewing Industry: A Guide to Historical Sources (Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1990), p. 182.

G.C. Boase, rev. Yolande Foote, ‘Austen, Robert Alfred Cloyne Godwin- (1808–1884)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 2 (2004), pp. 980–1.

John Bourne, ‘Charteris, John (1877–1946)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 11 (2004), pp. 213–14.

Archival sources:

OUA: UR 2/1/45.

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 2.

J77/1264/8543.

J77/3719/303.

WO95/1553/1.

WO95/1553/2.

WO95/4303.

WO95/4446.

WO95/4672.

WO339/9700.

WO339/12484 (C.B.M. Hodgson).

WO339/18681 (J.P.M. Carpenter).

WO374/33922.

On-line sources:

Wiltshire OPC Project: https://www.wiltshire-opc.org.uk/genealogy/ (accessed 13 August 2018).

Dr Spencer Jones, ‘The Recapture of Gheluvelt, 31 October 1914’: http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/portfolio/the-recapture-of-gheluvelt/ (accessed 13 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘John Charteris’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Charteris (accessed 13 August 2018).

Wikipedia, ‘Race to the Sea’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_to_the_Sea (accessed 13 August 2018).