Fact file:

Matriculated: Not applicable

Born: 16 November 1866

Died: 9 December 1916

Regiment: Royal Army Medical Corps

Grave/Memorial: Botley Cemetery, West Oxford: I.1.67

Family background

b. 16 November 1866 in Littlemore, Oxford, as the only son and youngest of the five children of Charles Thomas Palmer [I] (1834–69) and Sarah Palmer (1833–1893) (née Roberts) (m. 1856). At the time of the 1861 Census the family were living at No. 1l, College Cottages, Littlemore. At the time of the 1871 Census the widowed Sarah and four of her children – including Charles Thomas [II] – were living in Iffley, where she worked as a laundress. At the time of the 1881 Census Sarah, now classified as a pauper, was living in College Lane, Littlemore, with one daughter and Charles Thomas, both of whom were in work. At the time of the 1891 Census Sarah was living alone in College Lane.

Parents and antecedents

Palmer’s father, Charles Thomas [I], was a journeyman mason who had been born in Ramsgate, Kent. His grandfather, Charles Palmer (c.1808–98), was a cordwainer, later a boot maker and later still a hat maker in Ramsgate. At the time of the 1851 Census Charles Thomas Palmer [I] was apprenticed to his uncle Thomas Palmer (1805–63), a mason who employed four men and lived in Iffley, Oxford.

Palmer’s mother was the daughter of John Roberts (1795–1871), a coal dealer of Iffley, a southern suburb of Oxford.

Siblings

Brother of:

(1) Josepha Annie (1857–1933); later Burbrough (or Borborough) after her marriage in 1880 to Henry James Borbrough (1849–1916); eight children;

(2) Helena Elizabeth (1858–1945); later Webb after her marriage in 1878 to Alfred Webb (1857–1941); five children;

(3) Clara Hynes (1860–1942); later Augustus after her marriage in 1882 to William John Augustus (1861–1941); nine children;

(4) Fanny Roberts (1862–1892?); later Tripp after her marriage (1881) to Arthur Tripp (1860–1936); three children;

(5) Agnes Sarah (1864–1942); later Perkins after her marriage in 1891 to Ernest Walter Perkins (1867–1933); nine children.

At the time of the 1911 Census Henry James Borbrough was a college cook and he and his family were living at 18, Aston Street, Oxford.

At the time of the 1911 Census Alfred Webb was a carpenter and he and his family were living in Bournemouth, Hampshire.

At the time of the 1911 Census William John Augustus was a coachman and his family were living on the Isle of White.

Arthur Tripp served as a Private in the Army Hospital Corps from 1878 to 1890, when he left the Army to become a painter and decorator. He served in the Army Hospital Corps for a second time from 1900 to 1909, when he left again to become a painter and decorator. One of his sons – Leonard Douglas Beaumont Tripp – died in Bangalore, India, in 1919 while serving as a Private in the 6th Battalion of the South Lancashire Regiment and is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Hosur Road, Bangalore. After Fanny’s death Arthur Tripp married (1894) Frances Gibson (1873–1954); eight children.

At the time of the 1911 Census Ernest Walter Perkins was a coach driver and he and his family were living on the Isle of White.

Wife and children

Charles Thomas was the husband of Alice Wade (1878–1934) (m. 1897), and at the time of the 1911 Census they were living at 6, William Street, Cowley Road, Oxford. William Street was a speculative development on the part of William Gunston[e], a senior servant at Magdalen, and was a natural home for many of the College’s employees because of its proximity to the College.

Alice Wade was born in Mickleover, Derbyshire, as the daughter of John Wade (1846–1924), at one time a farmer of 80 acres.

Their children were:

(1) Constance Alice (1899–1986); later Bishop after her marriage (1922) to Wilfred Raymond Bishop (1895–1937), one daughter; and then Cunliffe after her marriage (1954) to Gerald Humphries Cunliffe (1882–1964);

(2) Margaret Evelyn (1901–89); later Davies after her marriage (1925) to William David Davies (1897–1969); one son;

(3) Reginald Thomas (b. 1906).

According to the 1939 Register, Constance Alice was an ambulance driver and living in Witney, Oxfordshire.

At the time of the 1911 Census Wilfred Raymond Bishop was a domestic gardener living in Wytham, near Oxford. During World War One he served in France with the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars (cf. V. Fleming).

When he enlisted in the Army, Gerald Humphries Cunliffe was a land agent living in Eynsham, Oxfordshire. He joined the Army Service Corps, became a driver, and in August 1916 disembarked in Salonika, Northern Greece (cf. T.H. Helme, A.J.B. Hudson and A.F.C. Maclachlan), where he was attached to 143 Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery. He was subsequently attached to various other artillery units until, in July 1919, he embarked on home leave from Çanakkale (Chanak), on the eastern shore of the Dardanelles. While on leave he was struck off the strength of the Army of the Black Sea, and when he was demobilized in October 1919 he became a Class ‘Z’ Army Reservist. In 1939 he was a farmer at Barnard Gate, Witney, and an Air Raid Precautions warden.

William David Davies was the son of a Welsh Calvinistic Methodist minister. He won a scholarship to Jesus College, Oxford, and matriculated in October 1915, only to have his studies interrupted by the war. When conscription was introduced in January 1916 he applied for exemption from military service as a conscientious objector, but his application was refused – first by the Local Tribunal and then by the Carnarvonshire Appeals Tribunal on 14 April 1916, when his appeal was heard in private. Nevertheless, at the sole discretion of the Appeals Tribunal he was given leave to appeal to the Central Tribunal in Westminster, which dealt with difficult cases whose outcomes could be used as precedents in Local Tribunals, and on 1 July 1916 he was exempted from Combatant Service on condition that he found work of national importance within 21 days. So from 20 July 1916 to 17 December 1918 he worked as an agricultural labourer on the Llŷn Peninsula, Carnarvonshire. After the war he returned to Oxford and was awarded a Second in Classics Moderations in 1919, a Second in Greats in 1921, and a First in Theology in 1922. He took his BA in December 1921, and his MA in 1923, the year in which he was he was runner-up in the Ellerton Essay Prize Competition of 1923, and in 1927 he was awarded a BD, the first nonconformist to gain this degree at Oxford. Although he was offered a Fellowship and the position of Theology Tutor at Jesus College, he rejected the offer as it would have required him to become a member of the Church of England. So after he was ordained in 1923, he served in a number of Calvinistic Methodist churches (now the Presbyterian Church of Wales) before being appointed Professor of the History and Philosophy of Religion at the United Theological College in Aberystwyth (1906–2003), an associated college of the University of Wales. He resigned in 1933 showing symptoms of what was probably a form of schizophrenia. Davies was a notable scholar and published several theological works in both Welsh and English. He also began writing essays and poems under the name of W.P.D. Davies, and although he claimed that he used the letter ‘P’ because it stood for Pechadur (sinner), it is more likely that he did so because it was the first letter of his wife’s maiden name.

Reginald Thomas was an electrical engineer and in 1948 he returned to England from his permanent residence in South Africa. But in 1950 he emigrated to Australia with his wife, Irene Gladys May (née Douglas) (b. 1913), on the P&O ship Maloja, from which they landed in Sydney.

Education and professional life

At the time of the 1881 Census Palmer was a gardener’s labourer; and at the time of the 1891 Census he was living with his sister Fanny and her husband and family in Mile End Old Town, in London’s East End, where he worked as a domestic servant. However, he returned to Oxford and at the time of his marriage in March 1897 he was a cook. From 12 October 1898 he was employed at Magdalen as a Roast Cook – a position with a starting salary of £3 6s. 8d. a month, the equivalent of £235 in 2017 according to the National Archives Currency Converter, a sum which went up to £4 6s. 8d. in 1910 (£313). In most years he was not paid for two months during the summer, i.e. during the long vacation, and received a larger sum in September. From October 1915 to October 1916, i.e. when he was in the Army and still alive, his College pay was halved (£2 3s. 4d.), and from February to December 1916, i.e. the month in which he died, it was drawn on his behalf by other members of the College staff.

The College staff (1901); unfortunately there is no legend to identify members of staff, but Richard Gunstone (1840–1924), Steward of the JCR (1880–1914), is readily recognised seated fourth from the right in the second row with Joseph Walter Gynes (1869–1941), Gunstone’s successor as Steward of the JCR, on his right. Palmer, who was 35 when the photograph was taken, is one of the five men in white cooks’ clothing

(Courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

War service

Palmer served as a Private in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) (Army Number WE 236). Until the new numbering system was introduced in 1920, each Regiment or Corps had its own numbering system. This caused duplication so that two or more soldiers in different regiments could have the same Army Number. In order to avoid such confusion, the Army Number in some regiments and corps had a special prefix, with WE being the prefix of the RAMC. There are no military records for Palmer, and they were probably destroyed together with thousands of others by enemy bombing in 1940. So we cannot be certain when he joined the Army. But it is likely to have been in October 1915 when his College pay was cut by 50 per cent. In the Servant’s Committee minutes of 1 September 1914, the first point is an order that “if any servant of the College enlists for the term of the War or for three years, there shall be paid to him or his representative during the time of his Service with the Colours half the wages to which he would have been entitled if he had remained in the active service of the College” (MCA: CP/9/24, vol. ii, [p.157]). Without this contribution it would have been hard for his family to survive on his RAMC pay of 1s. 2d. a day – i.e. £1. 15s a month – less than half his College salary in 1910.

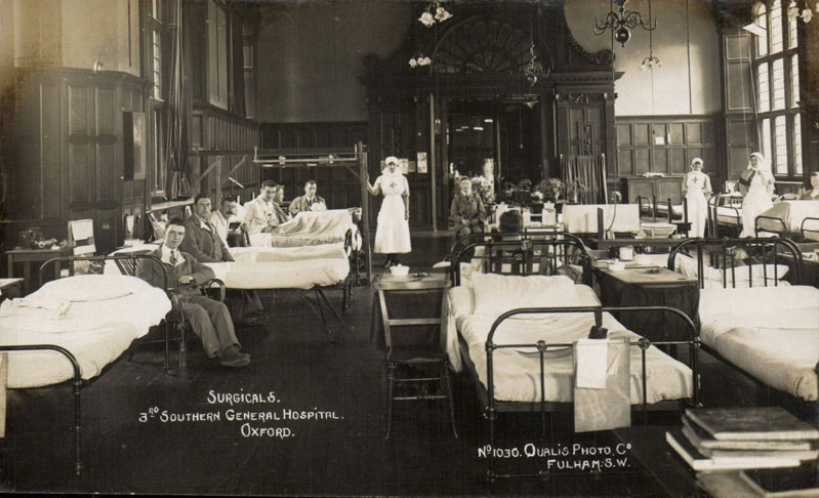

Surgical Ward 6, 3rd Southern General Hospital, Examination Schools, Oxford

Town Hall Ward, 3rd Southern General Hospital, Town Hall, Oxford

(Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library Archives- PC90; no known copyright restrictions)

We know that while Palmer was in the Army, he served in the 3rd Southern General Hospital, which was officially opened with 346 beds in Oxford’s Examination Schools on 16 August 1914 and was staffed largely by members of the Territorial Force. It expanded into adjacent and nearby buildings that included the Masonic buildings behind 49–52, High Street (48 beds), Cowley Road Workhouse (382 beds), the Town Hall (205 beds – mainly for malarial cases) etc. The first batch of Allied wounded numbered 150 men and arrived in mid-September 1914 to cheers by those gathered outside the Examination Schools, although the 40 German wounded were greeted with silence. The administrator of the hospital was Colonel George Ranking, RAMC (1882–1934), a retired Indian Army doctor and lecturer in Persian at Oxford University. Anticipating deaths in the hospital, Ranking asked the City Council for burial space. The Council agreed that British and Allied soldiers would be buried, free, in Botley Cemetery, but that a fee of 12s. 6d. (the equivalent of £37.00 in 2017) should be paid for “alien enemies”.

Palmer was 48 years old when war broke out. There was no conscription and even when conscription was introduced in 1916 he would have been too old to be required to join the Army. It is not clear why he enlisted but the hospital was staffed by the Territorial Force of which, like others of Magdalen’s servants, he may have been a member before the war. This would be another explanation for his not being paid by College for some weeks during the summer. We do not know in what capacity he served in the hospital, but as catering was a unit responsibility he may have served in the kitchens – otherwise he was likely to have been a medical orderly.

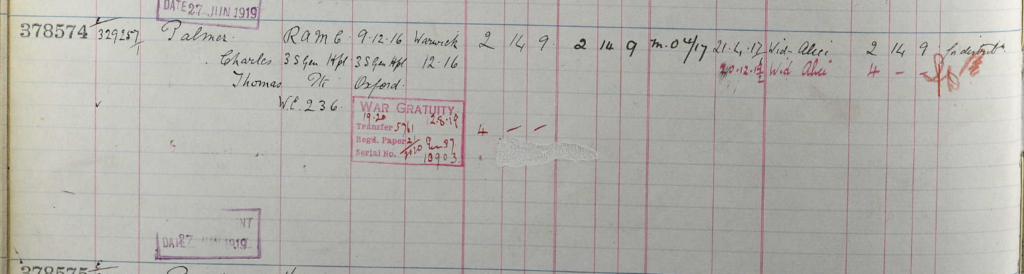

Palmer was taken ill early in December 1915 and died seven days later on 9 December. According to his death certificate he died in the Third Southern General Hospital that was located in St Peter in the East, a church that is now deconsecrated and part of St Edmund Hall. A post mortem was carried out and the cause of death given as pneumonia. This is in contrast to the entry in the College Servants and Tradesmen’s Ledger 1889–1920, which says that he died from wounds. After his death his widow, Alice, was paid £2 14s. 9d. in outstanding wages and a War Gratuity of £4 0s. 0d. (a total of £6 14s. 9d. which would have been the equivalent of c.£400 in 2017).

Palmer’s list of personal effects at the time of his death

Palmer is buried in Oxford (Botley) Cemetery, Grave I.1.67, and has no inscription on his gravestone.

Oxford (Botley) Cemetery; Grave I.1.67

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Printed sources:

Malcolm Graham, Oxford in The Great War (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2014), pp. 35–7, 48, 76–7, 133, 138–9.

Archival sources:

MCA: CP/9/24/1 (Servants Committee 1886–1905).

MCA: CP/9/24/2 (Servants Committee 1905–40).

MCA: AO/7/1 (Servants and Tradesmen’s Ledger 1889–1920), p. 109.

OUA (DWM): C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, MS. Eng. misc. e. 1161.

WO95/477.

WO95/5494 (Allocation of Heavy Batteries RGA).

On-line sources:

Cyril Pearce, Pearce Register of Conscientious Objectors: http://www.wcia.org.uk/wfp/pearceregister (accessed 26 July 2018).

Gomer Morgan Roberts, ‘Davies, William David [P.]’, Dictionary of Welsh Biography: http://yba.llgc.org.uk/en/s2-DAVI-DAV-1897.html (accessed 24 July 2018).