Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born: 10 August 1884

Died: 10 August 1916

Regiment: Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

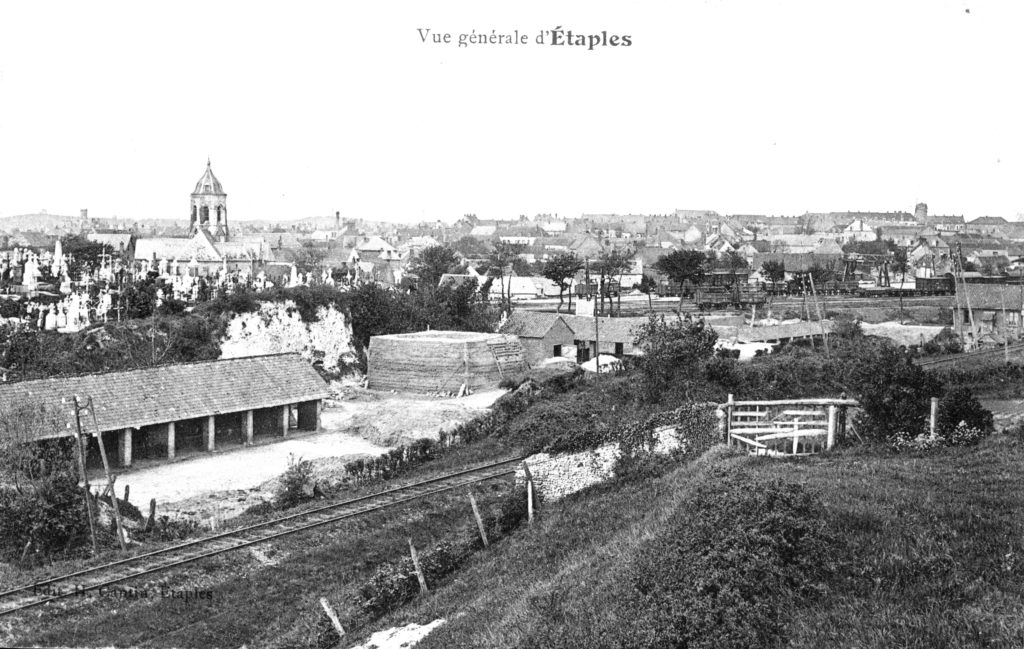

Grave/Memorial: Étaples Military Cemetery: I.B.42

Family background

b. 10 August 1884 in Bowden Hall, Upton St Leonards, Gloucestershire, as the third (youngest) son of John Dearman Birchall, JP (1828–97) and his second wife Emily Birchall (née Jowitt) (1852–84) (m. 1873). The family owned Bowden Hall from 1868 to 1924, but after John Dearman’s death, only the eldest son and his family lived there. Nevertheless, not counting gardeners, coachmen and a butler who lived in associated cottages, the family had nine servants (including a governess) living in the Hall at the time of the 1871 Census, five at the time of the 1881 Census, nine at the time of the 1891 Census, seven at the time of the 1901 Census and ten (including a governess) at the time of the 1911 Census. The unmarried children of the family tended to live at Saintbridge House, Painswick Rd, on the south-east edge of Gloucester (now a nursing home).

Parents and antecedents

Birchall’s father was a Quaker by birth but became a member of the Church of England when he married his first wife Clara (née Brook), in 1861. John Dearman was a successful cloth merchant who had established his own firm in Leeds in 1853, which, by 1871, was employing 13 hands. In 1868, five years after Clara had died of consumption in 1863, he bought Bowden Hall, a Georgian house with a 220-acre estate that had been built in c.1770 and had its bow fronts and stucco work added in 1800. It looked over the Cotswolds to Gloucester Cathedral, and John Dearman retired there in 1869. He had the park landscaped using the advice of Robert Marnock (1800–89), a leading horticulturist and garden designer. He also had the interior of the house remodelled with the help of the well-known interior designer John Aldam Heaton (1830–97) and his own brother Edward Birchall (1839–1903), who worked for Kelly & Birchall in Leeds, a firm specializing in the design of churches in the Italianate and Gothic Revival styles. John Dearman left £1,752,592 16s. 5d (the equivalent of £10 million in 2005). By the time that the Hall passed out of the hands of the Birchall family in 1924, its estate had grown to 512 acres, and since 1987 it has been a hotel.

Emily, Birchall’s mother, was a second cousin of Birchall’s father and the daughter of a Leeds wool merchant. When she married, she had just sat the Cambridge Examination for Women and been awarded a 1st (Honours), with distinctions in Divinity, Literature and French. She kept a detailed diary of their blissfully happy, seven-month-long honeymoon on the Continent that was published in 1985. John Dearman used his wealth to build up a valuable library and a large collection of blue-and-white porcelain, and to decorate Bowden Hall in a way that combined High Victorian and Aesthetic Movement taste. He occasionally acquired work from members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (founded 1848) and bought a window by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) and William Morris (1834–96). In 1894 he served as High Sheriff of Gloucestershire.

Siblings and their families

Edward was the half-brother of Clara Sophia (1862–1948), later Sinclair after her marriage (1893) to Reverend John Stewart Sinclair (1854–1919).

He was the brother of:

(1) John (“Jack”) Dearman (1875–1941, later Sir John); married (1900) Adela Emily Wykeham (1877–1965); one child;

(2) Arthur Percival Dearman (1877–1915); killed in action on 23 April 1915 during the disastrous attack on Mauser Ridge, north-east of Ypres, while commanding the 4th Battalion, Canadian Infantry (Central Ontario Regiment);

(3) Violet Emily Dearman (1878–1962);

(4) Constance Lindasja Dearman (1880–1956) (later Verey after her marriage (1907) to Reverend Cecil Henry Verey (1872–1958).

The Reverend John Stewart Sinclair was educated at Oriel College, Oxford, where he was awarded a 2nd class degree in Modern History in 1875 (BA 1876; MA 1879). He was ordained deacon in 1876 and priest in 1879 and worked as a curate in in Pulborough, West Sussex (1876–78) and Fulham (1878–85). From 1885 to 1898 he was Vicar of St Dionis, Fulham; and in 1898 he became Vicar of Cirencester, Gloucestershire, a parish of 7,536 souls with a gross income of £440 p.a., and also Rural Dean of Cirencester. In 1901 he was made an Honorary Canon of Gloucester Cathedral and in 1906 a Proctor of the Gloucester Diocese.

John Dearman was a farmer in the Cotswolds and, according to his obituarist, a “typical English country gentleman of the soundest type”. Before World War One, he served in the Gloucestershire Yeomanry (Royal Gloucestershire Hussars) and was promoted Captain on 24 July 1912. He remained in the Yeomanry during the war and in 1918 he was seconded to the Labour Corps and promoted Major (London Gazette, no. 30,957, 15 October 1918, p. 12,241) and served in France from May 1918. After the war he became the Unionist MP for North-East Leeds (1918–40). He was an ardent churchman, and his obituarist described him as “the type of layman on which the revival of religion will be based” and also claimed that he was “more than the main link between the Church Assembly and Parliament; for he was the main link in the Church Assembly between all sections of the laity”. Like his youngest brother, he “threw himself heartily into movements for better housing and social service, especially with the scouts”.

The Reverend Cecil Henry Verey was educated at Trinity Hall, Cambridge (BA 1896; MA 1899), and after training at Cuddesdon College, near Oxford, he was ordained deacon in 1898 and priest in 1900. He then worked as a curate in Bewdley, Worcestershire, from 1898 to 1902, and then at the Church of St John the Baptist, Windsor, from 1902 to 1908. After that he served as the Vicar of Bloxham, Oxfordshire, from 1908 to 1917 and as the Vicar of Painswick, Gloucestershire, from 1917 to 1929. In 1931 he became the Rector of Buckland with Laverton, in the Diocese of Gloucestershire, a parish of 266 souls with a gross income of £382 p.a.

Education and professional life

Birchall attended Mr Girdlestone’s School, Sunningdale, Berkshire, from 1893 to 1898 (cf. A.P.D. Birchall) and then Eton College from 1898 to 1903, where he played in the Eton “Field” game and for the “Oppidan Wall” in the Eton Wall Game. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner reading Natural Sciences on 19 October 1903, having unsuccessfully taken Responsions in Hilary Term 1903, and then resat them in Michaelmas Term 1903. He took the Preliminary Examination in Natural Sciences (C3 [The Elements of Physics] and C4 [The Elements of Chemistry]) in Trinity Term 1904 and the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1905 before starting to read for an Honours Degree in Chemistry, during which he attended lectures in the Daubeny Laboratory. In Trinity Term 1907 he was awarded a 4th in Chemistry and he took his BA on 7 November 1908. In December 1906 he played for the Oxford Old Etonians’ team in the annual Field Game – a cross between rugby and soccer that is played by all Etonians during their first three years in the College – against the Cambridge Old Etonians: besides himself, three others of the team of eleven would be killed in action or die as a result of the war: C.T. Mills, C.A. Gold and L.R.A. Gatehouse.

Possibly because of his family’s Quaker origins, Birchall seems to have developed a strong religious consciousness before matriculating at Oxford, where he made most of his friends among young men with similar temperaments who had translated religiosity into developed social awareness. After his death, several people who had known him at Magdalen said as much in letters to his family. One of the Fellows wrote to his sister: “I feel I must say how proud and thankful I am to have known your two brothers. Of all the many high-minded and unselfish men whom Magdalen has lost in the War, they will always stand out in our affection and admiration among the foremost.” President Warren wrote to the family in order

to condole with you in another sadly heavy and grievous loss to your living family circle and to my sorely bereaved College. True brothers they were worthy of each other. To lose them both is more than usually hard. I was deeply attached to, and fond of Edward. If Arthur was more commanding, a splendid leader man, Edward was a most winning and sterling fellow, good all through, full of capacity, which he always turned to unselfish ends.

And a Magdalen friend said of him: “He was such a rock, so sane and steady, an ideal friend and adviser. If everyone had been as unselfish as he all his life it would be a different world.” But it is more surprising, perhaps, to find his superior at the Labour Exchange in Bristol, where he worked from 1913 to 1914, commenting even more explicitly on Birchall’s spirituality in a letter to his family:

It is so glorious to think how absolutely ready he was to go. I can think of nobody I have ever known more absolutely ready. Many will long remember his outlook and the spirit of his service […] You had only to work with him to know that there was something very beautiful in him which belonged much more to another world than to us.

As a result of his burgeoning religiosity, Birchall seems not to have been greatly interested in such conventional pastimes at Oxford as organised sport, and one wonders what he made of the riotous Bump Supper of 1906 (see G.M.R. Turbutt). Instead, he began to take a keen interest in industrial problems, and soon decided to devote his life to social service. As an undergraduate he was very generous in his support – often anonymous – of those causes which interested him, but had a “supreme contempt for money grubbing” and all forms of speculation. So after graduating in 1907, he was one of the group of four young men who, in 1908, settled at Calthorpe Cottage, St James’s Road, Edgbaston, at the invitation of the socially concerned Canon William Hartley Carnegie (1859–1936; Magdalen 1878–83), the Rector of St Philip’s, Birmingham, from 1903 to 1912. Canon Carnegie wanted Norman Chamberlain and some of his friends to come to Birmingham and “engage in social and political affairs so as to equip themselves with a first-hand knowledge of such subjects from the working man’s point of view”.

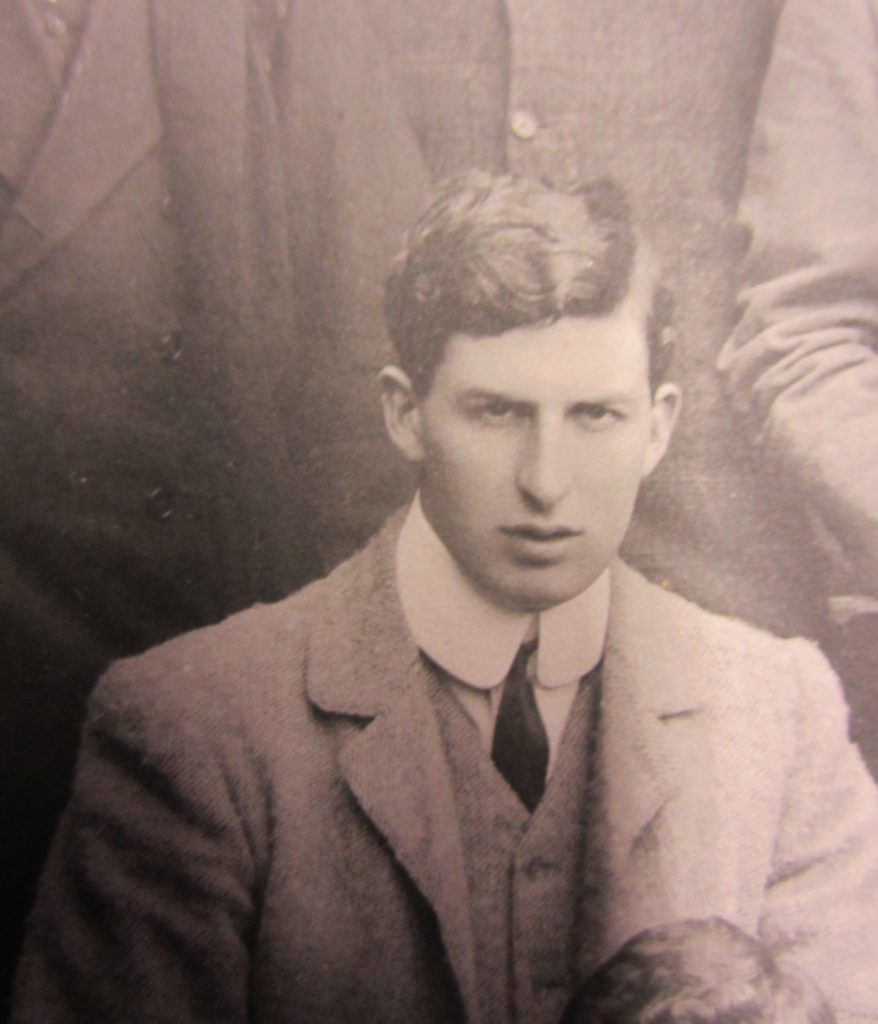

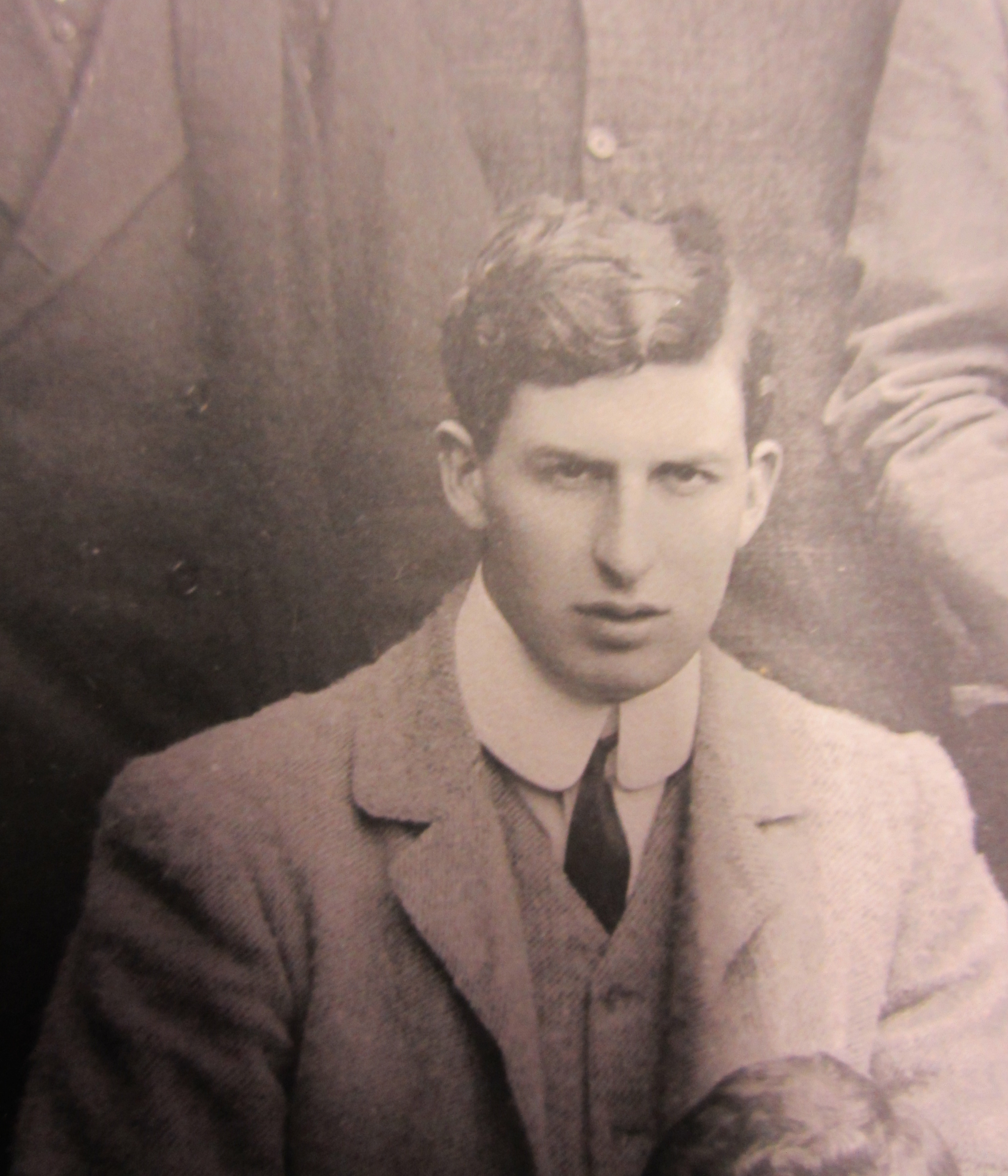

Edward Vivian Dearman Birchall, BA, DSO

(Photos courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford. Both are details from group photos (c.1905 and 1907) of Magdalen’s Rupert Society (1897–c.1910), a combination of dining club and debating society.)

“What a burden will rest on those who are left to make England worthy of the tremendous Sacrifice! & what a bad beginning is being made by this mad cry for vengeance on the Hun! Nothing upset Edward more than this. He prayed he might never have to kill a German – & He has had his wish.”

Birchall spent over three years in Birmingham, where he worked hard at the Juvenile Police Court and for Chamberlain’s City Aid Society, of which he became the Honorary Secretary. He also did a lot of good work there in connection with a system of mutual registration of charity, for which purpose “a mass of useful statistics were collected and carefully tabulated”. His work in Birmingham also brought him into contact with the embryonic Guild of Help movement and in 1911 he was appointed Secretary of the Guild of Help Conference and so became largely responsible for the negotiations which brought about the formation of the National Association of Guilds of Help in the same year. He was also appointed the first Honorary Secretary of the Association and was responsible for the moulding of its policy. Part of his work consisted in visiting the Guilds of Help in various parts of the country, where, according to the person who contributed the long obituary to the Upton St Leonard’s Parish Magazine, “his personal qualities were of the greatest value in the difficult work of co-ordination”. Moreover, in the view of the same obituarist: “the friendly relations now existing between the Guilds of Help, Councils of Social Welfare, and Charity Organisation Societies, are largely the result of his self-effacing work”. After his death, a Guild of Help Secretary wrote to his parents with obvious sincerity and considerable depth of feeling:

We had hoped in all the plans that we had laid for the uncertain future that we should have had the assistance of his unique qualities. I have never had a greater joy in working with anybody than him, and his absolute unselfishness and idealism, combined with a practical ability in handling all kinds of men and women, gave him an influence over us all that we can never hope to get from anyone else. There are many people, whom you will never hear from, whose lives have been permanently enriched by his cheeriness and unfailing freshness of outlook. We are all of us poorer by his death, and the inevitable problems of the future will be harder to face without him.

In 1911 Birchall left Birmingham for London, where he took an active part in the work of the Agenda Club, which had been founded in July 1910 by Joseph Peter Thorp (1874–1962). Thorp had been a Jesuit from 1891 to 1901 and, signing himself as ‘T’, was the drama critic for Punch from 1916 to 1934, i.e. after A.A. Milne had been called up into the Army. As little is known about the Club, it is worth setting out what can be gleaned, mainly from The Times, about its aims and history. It held an inaugural dinner on 7 December 1910 at the Hotel Cecil in London, and this was presided over by the Liberal peer, the 9th Lord Shaftesbury (1869–1961), who was known for his philanthropy and

reforming zeal. According to a report that was published in The Times on the following day, the Club was intended to be “an organized means of saving and making effective the straggling, isolated idealism of the men of good will, men who want (or wanted) ‘to do something’”. Its object, the article continued,

is not so much original creative work as the seeking out, combining, and increasing of forces which already exist, particularly in regard of philanthropic work and personal service. […] Care will be taken to confine the programme of the club not only to non-controversial subjects, but to subjects which may be attempted with reasonable hope of success. Wherever a society already exists devoted to any such objects, the co-operation of that society will be sought for the purpose of securing the fullest possible data for an effective campaign. The Agenda Club will reciprocate by placing its organization at the disposal of the particular society.

Or in other words, the Club saw itself as a central component of a two-way process: it sought to encourage the privileged to do their bit for the under-privileged, and it wanted established organizations and charities to use the expertise of its members. At first it generated considerable interest, and on 4 February 1911, its Board of Control published a long letter in The Times which developed the ideas of the original article. It began by setting out its two fundamental beliefs: (1) “there is a vast amount of good will and experience which could be applied to social service if only it were organized”; (2) “many types of men who had never hitherto been enlisted in this kind of work would be only too glad to place their services at the disposal of such bodies as could make use of them”. Consequently, it continued: “The Agenda Club can now offer to various groups engaged in philanthropic and ameliorative work the picked services in the three departments of (1) Business system and organization, (2) publicity, and (3) illustration”. So convinced was the Club that it was in the process of tapping a “vast amount of unorganized available good will in England” and “a notably increased sense of social responsibility […] especially perhaps among the younger men”, that it had its theses printed in book form and it announced its intention to distribute these to those persons who attended its recruiting meetings in March and April. Indeed, the Club generated so much idealism that one of its members persuaded the Japanese Embassy to present the Club with an eighth-century Samurai sword by Yasatsuna as its emblem.

A “well-attended” women’s meeting took place on 1 March 1911 at which the speaker, William Schooling (1860–1936), the Club’s chairman, reported to those present: “An important branch of activity already taken up by the club was work among lads for their physical, mental, and moral improvement and to prevent their drifting into ‘blind alley’ occupations”, and by the end of September 1911 an article in The Times mentioned that the Club now had about 1,000 members. But on 30 September 1911, The Times published an article at the Club’s behest which appealed for social workers and which, with hindsight, suggests very clearly that the Club was starting to discover its limitations. It reads:

The establishment of the London County Council School Care Committees has created a very large demand for voluntary social service – a demand which we have been asked to assist in supplying. The work consists in following up and securing as far as possible the medical and surgical treatment recommended by the school doctors; organizing the provision of feeding for children suffering from bad nutrition; after care; the organization of school games, and a general befriending of the school children in other ways. The demand is an urgent one, and we understand that the School Care Committees can find work for 500 helpers at once. The amount of time which can be devoted to the work is entirely a question for the individual worker to decide, as the committee will readily welcome persons who can spare anything from a few hours a week upward. Will those ladies and gentlemen who are willing to spare a portion of their leisure to this service communicate with the Agenda Club?

The goodwill was certainly there among the Club’s members, and probably some people of wealth and leisure did step forward and give to poor children what time they could spare from their other activities. But the problem of child poverty sketched out above was too big for a club of gentleman amateurs to offer anything more than small-scale support; it required much larger, state-funded measures that were required by legislation and enforced by professionals; and it suggested a new kind of social politics that would have been alien and unacceptable to most of those good souls who responded positively to the Times’s appeal. The Club also gave its support to National Health Week (28 April–4 May 1912), and that help was gladly received by those responsible for the relevant policies and legislation, but it is very evident from an article entitled ‘Public Health and the Insurance Act’ that that help was a very small drop in a very large bucket.

The one area of social deprivation where the Agenda Club made a small but positive contribution concerned golf caddies, many of whom were adolescent boys. A representative of the Club attended the AGM of the Caddies Aid Association in December 1911 and the two organizations organized a large public meeting on 11 October 1912 in the United Services Club, where the problems facing caddies were discussed in the presence of no less a personage than Prince Albert of Schleswig-Holstein (1869–1931), a grandson of Queen Victoria and a professional soldier in the Prussian Army who had grown up in Britain and liked golf. The meeting was told that in the intervening year, the joint Committee had investigated the situation of Britain’s 12,000 golf caddies and produced a booklet on its findings entitled The Rough and the Fairway. Not only were caddies poorly paid – on average 13 shillings per week – but they often lived in sub-standard housing, idled away much of the week waiting to be employed at the weekend, and were rarely trained for useful employment when they grew up. So the two organizations declared it their aim to remove caddies “from the list of ‘blind alley’ employments” by taking relevant steps. One of these seems to have been the setting-up of a joint committee – the Caddies Aid Committee – to implement reforms. But the enterprise soon got into difficulty – partly for want of funds and partly because of a clear unwillingness on the part of golf clubs to accept the Committee and the Agenda Club as a central umbrella organization for ensuring the well-being of their employees. So, in a letter in The Times that appeared on 18 March 1913, W.E. Fairlie found himself compelled to appeal to individuals for donations because the Club now had so little cash at its disposal: the Caddies Aid Committee had had free use of the Agenda Club’s office and clerical staff and published a booklet, entitled The Caddie, which was sent to 560 golf clubs around the country. But only 60 clubs had responded and now the Club was badly short of funds. Nine months later, the situation was not much better and on 9 December 1913, The Times published what would be a final report on the Agenda Club and its works. In 1913, it said, the Caddies Aid Committee had published two more booklets: Suggestions for the Formation and Work of a Caddies’ Association and Memorandum on the Employment of Golf Caddies, and “schemes in the interest of the caddies, recommended by the committee, have now been adopted by 25 well-known clubs”. Perhaps that result was better than nothing given the lack of protective legislation, but by any standards, these results show just how little the leisured and privileged classes were prepared to do for the poor, even a section of the poor whom many of them must have encountered every week, especially if the proposals that were intended to help them smacked of organized labour and therefore trade unionism.

We do not know what part Birchall played in all of this since his name does not appear anywhere in the press reports. But his obituarist spoke of ways in which “his tact was frequently of service in smoothing out difficulties that arose between this and other organisations doing similar work” and “his unfailing sense of humour and its terse expression served him in good stead in all negotiations”. Moreover, the Club’s stress on the need for co-ordination and reliable data must have made considerable sense to someone who had worked for the National Association and would leave a considerable sum for the setting up of a National Council of Social Services. So the demise of the Club must have caused Birchall considerable disappointment – but it made him see where the future lay and look for a job in the state sector that would enable him to continue his interest in child welfare. This he found in the Juvenile Branch of the Labour Exchange under the Board of Trade and he was attached to the Exchange at Bristol, where he worked until the outbreak of war. According to the Upton St Leonard’s obituarist: “to him social service was no mere hobby wherewith to fill up his spare time, but a definite career which called him to his office early on Monday morning and kept him there till Saturday at mid-day. Counter-attractions of whatever kind were never allowed to keep him from his office.”

Although Birchall’s work did not admit of lengthy holidays or the formation of relationships outside that work, his relationship with his younger sister Violet blossomed and he increasingly spent most of his spare time with her at Saintbridge House, Gloucester, which he had made his home since 1901. Thus, according to his obituarist, “there grew up the most intimate friendship with his sister. Their affection for each other was far more like the perfect relationship between husband and wife. Constant devotion to, and thought for the other, permeated their lives. The reticence, so marked with others, had no place with her. Their inmost thoughts were shared.” When his brother A.P.D. Birchall was in Canada, where he was attached to the Canadian Instructional Staff and represented the British forces in Canada, Birchall went out to see him twice and on each occasion visited the battle fields of the American Civil War, where “he extended what was already a very considerable knowledge of the events which occurred during that momentous time”.

“Birchall says that he doesn’t want to get killed a bit. He wants to die at the age of ninety-five and be buried by the vicar and the curate, and his funeral attended by all the old ladies of the parish! He strongly objects to large objects of an explosive nature being thrown at him, and then his remains being collected in a sandbag and buried by ribald soldiery and dug up again two days later by a 5.9!”

Military and war service

Birchall is said to have hated war, but as a dutiful member of the English squirarchy he was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the socially superior Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry on 9 April 1904 and promoted Lieutenant on 28 April 1906, probably in the 1st Buckinghamshire Volunteer Rifle Corps. In September 1908 he was transferred into the 120-strong ‘B’ Company of the newly formed 1/1st Buckinghamshire Battalion (Territorial Forces) that was stationed at Aylesbury and was generally known as the “Bucks Battalion”; on 5 October 1913 he was promoted Captain (London Gazette, no. 28,281, 12 December 1913, p. 9,175). He mobilized on the outbreak of war and trained for seven months, first at Cosham, a northern suburb of Portsmouth, Hampshire, and then at Swindon, Wiltshire, where it transpired that at that time only about 60% of the Battalion (c.600 men) were willing to volunteer for overseas service (4–c.25 August). But most of the training was done at or near Chelmsford, Essex, and consisted of route-marching, musketry, entrenching and practising attacks. When describing the training in a letter to his family of 13 November 1914, Captain Lionel William Crouch (1886–1916; killed in action near Pozières on 21 July 1916), a solicitor by profession, said that “We are making some ripping dug-outs with little stores and […] very nice latrines, which Birchall says are as good as an aperient to look at!” Crouch had been with the Bucks Battalion since 1907 and become a good friend of Birchall’s. So his letters from the front to his family, which were privately published in 1917, will be extensively used below to throw light on Birchall’s military experiences.

Captains Edward Vivian Dearman Birchall (left) and Lionel William Crouch: both from a group photo of the officers of the Bucks Battalion (c. March 1915)

(Photo courtesy and copyright Stephen Berridge Esq.; www.lightbobs.com)

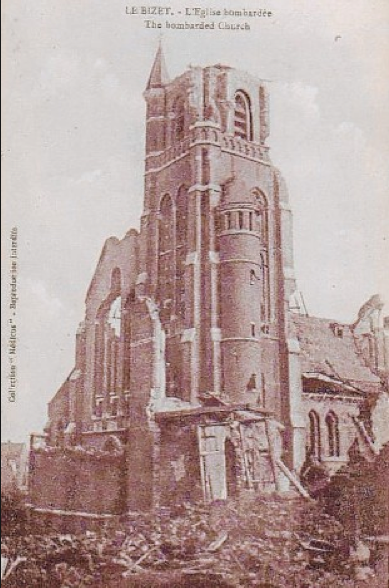

As training progressed, the members of the Bucks Battalion became more willing to go overseas, and even impatient to see action in France once they realized that other Territorial Battalions were disembarking there after doing considerably less training in England. The Battalion finally left Chelmsford on 30 March 1915 and after a “topping crossing”, disembarked at Osterhave, a southern suburb of Boulogne, on the following day as part of 145th Brigade, in the 48th (South Midlands) Division (see G.H. Alington and L.W. Hunter), with Crouch as the Commanding Officer (CO) of ‘B’ (Aylesbury) Company and Birchall as the CO of ‘D’ (Wolverton and High Wycombe) Company. After a day in a rest camp, the Battalion entrained on the afternoon of 1 April and travelled to a destination in Northern France, probably Hazebrouck, before marching at night for seven to eight miles, past Cassel just south of the Franco-Belgian border, a “very pretty village […] on the top of a hill” to the village of Terdeghem (1 April), still south of the border. There they billeted in the “garlic-scented kitchen” of a farm which had “a beautiful old oak ceiling” but was “spoiled by the dirt and stink”. So much so that Crouch remarked in a letter that “The natives seemed rather astonished at seeing me shave, wash, and clean my teeth.” The Battalion stayed in Terdeghem until 4 April, then marched to billets in Méteren, about six miles to the south-west but still in France. From 7 to 12 April the Battalion had its first experience of the trenches at Le Bizet, about eight miles east-south-east of Méteren and just over the border in Belgium. On 12 April it marched to Steenwerck, about five miles to the south-west of Le Bizet where it trained for three days in the second-line trenches and came under hostile fire. Crouch, who would prove his worth as a Company commander, wrote in a letter home:

All this doesn’t alarm me at all. I thought it would, but it only interests me intensely. I have never enjoyed myself more than during the last three days. […] The more I see of this show the more I want to see. The only thing I don’t like is the responsibility of commanding a company. What I should love would be a roving commission to saunter around where I like. A war correspondent’s job would just suit me.

The Battalion spent the period from 15 to 23 April in the Reserve trenches in Ploegsteert Wood, just north of Le Bizet, followed by four days in Divisional Reserve at Romarin, both places at the south-eastern corner of the Ypres Salient (where the Second Battle of Ypres would take place from 22 April to 25 May 1915). But from 27 April to 2 May 1915 it was back in the trenches in Ploegsteert Wood, where it incurred its first casualties. The Battalion’s third stint in the trenches lasted from 6 to 10 May 1915 and immediately afterwards Crouch wrote a long and angry letter home in which he railed against the German shelling of local civilians:

The brutes shelled the little town behind our lines [probably Le Bizet], and killed a lot of poor wretched people. I came through it on my way back last night. The church was of course already wrecked, but now there are great holes in several roofs. An estaminet just opposite the church is sans roof, a little chapel formerly used in place of the church is partially wrecked, and a convent smashed up. A shell burst outside Guy’s [his brother] and my old billet, smashing all the windows. One of my men who was in the town said the sight was pitiful, all the people and children running about nearly demented. When I came through last night, I saw some of the people coming back. The expressions on their faces made my blood boil. My man said that during the shelling there were little quiet crowds of forty or fifty people kneeling down outside each of the little shrines along the road outside the town. […] I believe some twenty houses were burnt down. These things are doing good in a way as they properly upset our chaps, and after the news of the [RMS] Lusitania [torpedoed on 7 May 1915, with the loss of 1,198 lives, many of them American] and this bombardment I think our chaps would have liked to get at the swine. […] When we came back to our billet, we found Madame’s old father installed. He is a dear old chap of seventy-nine and partially paralysed. Madame tells me how the Boches had ill-treated him. They knocked him about and punched him, and an officer shoved a revolver at his throat. The whole race want wiping off the face of the earth.

When Birchall had been in France for about a month, he heard of his brother’s death near Ypres on 23 April 1915, the second day of the Second Battle of Ypres, and in the letters home which followed this event, his normal reticence was lifted and the depth of his religious convictions revealed. Thus, soon after receiving the news, he wrote to his surviving brother John:

I still don’t realise it at all … I hope we shan’t ever treat it as a subject not to be talked about or mentioned, and I should like to go on referring to him and thinking of the things he’d have liked and his way of looking at things. For instance, I’m certainly not going to cut him out of my prayers … I’m not miserable here at all … Let us show that we do really believe that he is now in happiness and that we’re trying to be happy with him. I believe one can cultivate a sort of Communion of Saints of one’s own in a private way, though he would be amused – maybe is – at such a formal name for what is merely going on with your love and affection, instead of washing him off the slate so to speak. […] We’ve got to remember … that all these things change and pass, and the real things stand for ever … Anyway, there’s nothing in sorrow or suffering which Our Lord hasn’t been through Himself. There’s no pain He can’t sympathise with.

In a second letter he said:

I do agree entirely that a regular and designed sequence of events led up to the splendid climax: and that one can only look at the whole process and feel how wrong one has been in the past in doubting and questioning – for instance, it seemed so cruel when he was cut out of the War at the beginning, but now one can see how absolutely necessary and proper it was. The final touch of “P[ercy]” with his walking-stick, perfectly calm and collected, getting his men together in a regular hell of fire, is the perfect culmination of what was an almost perfect life. The absence of the usual funeral morbidness makes it easier to think of him now somewhere not very far away, still active, still storing up his little kindnesses and jests! It would be much harder to realize the continuity of life before and after if one had to go through all the usual horrid routine. Sometime I may be there and see his grave, but I don’t want to very much. I hate these false ideas of finality.

And in a third he asked:

Have you thought of meeting B and F [brother officers already killed in action] and all of them again? I believe, somehow, he has, and that without really leaving us. … It’s all so splendid I simply can hardly talk about it: it’s funny any sort of glory coming into our dull Quaker family.

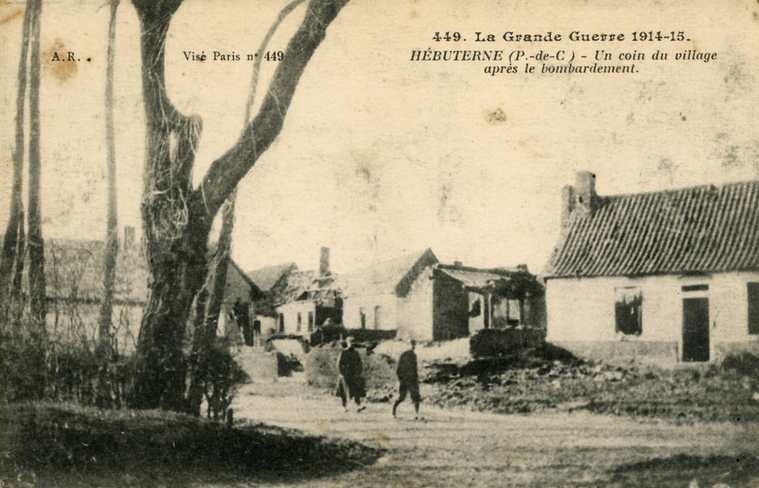

In the south-west corner of the Ypres Salient, the Bucks Battalion’s alternating routine between the trenches in Ploegsteert Wood and billets in nearby villages continued through May until 24 June, when the Battalion started a long night march south-westwards towards the trenches on the Somme. Although the exact destination was unknown to most of the officers and men, the Battalion tried to march c.15 miles parallel to the front line, but with rests and occasional stretches by train. The Battalion trained as it moved south-westwards, via Bailleul (24 June), Vieux Berquin – Busnettes (27 June), Allouagne (28 June–11 July), Houchin (12–16 July), Lières (17 July), Berguette – Doullens – Marieux (18–20 July), Coigneux (20–22 July), Bayencourt and Sailly-au-Bois (22–24 July), until it finally arrived in Hébuterne, about eight miles north of Albert and three miles north-north-west of Beaumont Hamel, where it was immediately sent for three days to the trenches just to the north-east of the badly damaged village.

During the trek south-westwards, the Battalion had had such a quiet time that on 25 July 1915, when he came out of the trenches, Crouch could write to a friend that he was enjoying himself at the front:

Personally I like the trenches. There is always something doing. […] One got rather tired of mucking about behind the line, digging trenches here and marching there. It is a grand life and nothing to grumble at. Of course sometimes one gets tired and irritable and apt to grouse at nothing. The guns are going it some just now – boom, crash! but as long as a shell doesn’t come inconveniently close, one doesn’t notice them.

He then went on to describe his “fine dug-out right in the earth” – a truly bijou residence compared with what he and his Battalion had known at the south-eastern end of the Ypres Salient:

You must first scrape your boots, then you go down four steps. The dug-out is quite large and roofed with large timbers (bits of trees). The roof is supported with a large bit of tree and large cross-beams. I forgot to say that I have a door and a fanlight over it. Inside is a good-sized table, a little table (what an auctioneer calls a ‘what-not’, I think), a tapestry cloth, a large bed with spring mattress, two pictures, and various little china ornaments, a large curtain. The dug-out is walled and roofed with some sort of leather.

But Crouch’s pride was premature, for the weather turned treacherous, and on 10 August, when the Battalion had just returned from billets in Couin, just to the west of Hébuterne,

a terrific thunderstorm broke out, the worst I’ve ever seen. Rain poured in torrents, and the trenches were rivers, up to one’s knees in places and higher if one fell into a sump. […] It was pitch dark and all was murky in the extreme. The rifles all got choked with mud, through men falling down, so I instituted an armourer’s shop in each dug-out, and the rifles were brought in one by one to be cleaned. A man worked in each dug-out all night. The rest sweated at baling with buckets. Mon Dieu, it was a night! Bits of the trench fell in. To cap it all, a thick mist arose at sunrise and we stood-to for five hours until it cleared!

Like the rest of 145th Brigade, Birchall’s Battalion would alternate for the best part of 11 tedious months between the trenches at the northern end of the Hébuterne Sector and billets in a semi-circle around the village itself. So, for the rest of 1915 and most of the first five months of 1916, the Battalion stayed almost without interruption within the quadrilateral formed by Hébuterne, Sailly-au-Bois, Courcelles-au-Bois and Couin. In mid-September 1915, it had to go through an experimental exposure to chlorine gas in a gas-filled stable in order to test the British Expeditionary Force’s new but rudimentary equipment, which, they were relieved to say, performed reasonably well but left a lot of the men with smarting nostrils and headaches. By late September, the days were often muggy and oppressive even though the nights were getting colder, but at least the trenches were “in ripping condition” as “all the floor is bricked, and is brushed over with a broom until one could eat one’s dinner off it”. Birchall had a dug-out of similar quality to Crouch’s, and when a “priceless old Orangeman” – the second-in-command of a “weird and happy-go-lucky” group of men who were temporarily attached to the Bucks Battalion for training in trench warfare – saw it, he was astonished and commented: “Shure and it’s a drawing-room with paper on the wall and all and pictures.”

On 22 October, the Battalion was out of the line and in billets at Couin (19–27 October), and Crouch wrote a letter to his sister of the “deuce of a time” that one of the Battalion’s Companies had recently experienced in the front-line trenches near Hébuterne:

They had the worst bombardment we’ve had in the last seven months [i.e. since April 1915]. Imagine thousands (literally, some say 3,000, others 6,000) of h[igh] e[xplosive] shells pitched into a fairly short front of trench. It was pretty noisy to listen to, one continual scream of shells and explosives. […] I think it speaks well for the dug-outs and other precautions that the casualties were insignificant.

The same letter tells of some “bright spirit’s brain-wave” which led to the decree that “a Captain ought to go out with each company’s working party”. But by the time Crouch and Birchall were ready to comply, they discovered that the Engineers “had scattered [the parties] all over the face of the globe” with the result that the two of them had to “tramp for two hours over this country of magnificent distances before we found the first fragments of our companies” – and some they never discovered at all! By mid-November the incessant rain had done serious damage to the trenches and Crouch wrote to his mother:

You can’t imagine their state, and what I told you [during his recent leave], that people at home can’t do too much for the poor devils of men out here, I could repeat twice as strongly. Conditions in the trenches [in] this weather are rotten. The sides all fall in, dug-outs collapse, and all leak. Even our “marble hall” [i.e. Crouch’s rather posh dug-out that was described above] leaks badly, and my bedroom is hopeless. We can only use one bed. Everything is liquid mud. When the Company took over, one length of trench was liquid mud over one’s knees. None of the men in the front-line trenches can lie down to work; they have to sit up on their packs or on a box, because the floor is all wet mud. The Huns are evidently still worse off, as their trenches opposite us lie well down a slope.

On 15 November 1915, when the Battalion was in the trenches near Hébuterne (12–20 November), frost and snow arrived, so that

the trenches are perfectly awful for the men now; everything is falling in and all the dug-outs leak. […] Viney’s [i.e. Captain Oscar Vaughan Viney (1885–1976), the second-in-command of ‘B’ Company] and my sleeping dug-out is like a well and one of the beds has had to be abandoned. The water drips from a dozen places in the roof continuously. I went into my old Company headquarters, called the Rathaus, the other night, and what a spectacle! One side has all fallen in, water pouring from the roof, and two wretched signallers squatting up in one corner with a candle and their telephone instrument, a water-proof sheet suspended over their heads to keep the water off. The savages opposite us are evidently in a far worse state, and we have fired on parties repairing and baling their trenches. Apparently their front trench has completely foundered for 100 yards in one place, as a Hun had the impudence to walk along the top of the parapet yesterday morning. The range, 750 to 800 yards, is too great for accurate shooting.

He concluded the letter with the postscript “Our great battle now will not be against the Huns, but against frost-bite.” The situation had not changed by early December, and on 4 December, when the Battalion was back in the trenches near Hébuterne (29 November–6 December 1915), Crouch wrote to his father, offering him

a brief if lurid account of our present existence. It can only be described in Tommy’s language, “bloody”. I really don’t think that swearing is bad language out here. Oh, how I should like to get hold of some of those slackers in England and put them in trenches, also those people who still think that Territorials are no good. We have had nothing but rain, rain, rain. Some parts of the trenches are well over the knee in jammy mud. It is literally true that last night we had to dig one of my chaps out of the parapet and his thigh boot is still there. We can’t get that out. All the dug-outs are falling in. The men are astonishing. The worse the weather the more cheerful they are, and Viney had to slang one platoon yesterday for singing in the trenches. Of course they get no rest; they have to work all day and all night in order to keep the water down. The sides of the trench fall in and with the water form this awful yellow jam.

But the state of the ground had even nastier consequences, and two days later Crouch recounted to his mother how the rain was revealing that the ground behind the parados was probably “full of dead Boches” who were beginning to stink, together with a French soldier called Pierre Jeanneau who was also “making himself rather unpleasant”. On 19 December, during another stint in the trenches (14–22 December 1915) after a week in billets in nearby Couin (6–14 December 1915), Crouch put matters less delicately in a letter to his father, to whom he had sent a German Pickelhaube as rather an unseasonal Christmas present:

I was awfully glad that the Boche helmet is such a success. Would you like a skull to go with it? The rain is disclosing all sorts of interesting souvenirs behind my trenches. There is a little osier-bed in front of a hedge, and evidently two shallow pits were dug and dead Boches were bundled in anyhow. The pits are now sinking a little, and boots, bones, clothes, and all sorts of débris are sticking out. There are two fine skulls there. I carried one on the end of my stick and planted him at the head of a communication trench, but it has been removed.

There was only one positive thing about such a state of meteorological misery, and Crouch put it thus in one of the two preceding letters: “Under these conditions hostilities are almost a wash-out” even if patrolling and artillery barrages could not cease completely, giving rise to “sporting scraps” in the first instance and “the deuce of a funk” in the second.

By mid-January 1916, i.e. the precise juncture when compulsory conscription was being hotly debated in Britain, Crouch informed his mother that his Battalion was “grievously short of men” and also, more tellingly, that “we are all dead tired and fed to the teeth”. So on 23 January 1916, during yet another spell in the Hébuterne trenches (21–27 January 1916) he admitted to his father that he had been “in a vile temper” because of the appalling mud and because the long-awaited “thigh gum-boots”, though “fine things”, were “awfully difficult to walk in” when the mud was so bad, and that he had caught an awful cold and developed bad stomach-ache. Seven days later, the “most infernal cold and cough” had not gone away, and Crouch had developed an equally persistent “spinning headache”. Indeed, he also felt “so beastly ‘nervy’” that he had taken, uncharacteristically, to “ducking at bullets” and jumping “like blazes” at shells. “We are all getting like that”, he concluded, “It is absurd keeping us in the trenches so long – six months continuously now.”

But despite that absurdity, the Bucks Battalion was still in the front line at Hébuterne on 4 March (2–10 March 1916), and the mud was still very bad, and it had started to snow again, and the men were so tired that on the previous day a party of four were found stuck fast because they “had exhausted themselves in their struggles and couldn’t move”. During the same stint, on 8 March, Crouch wrote to his mother that “the snow has been awful and the trenches knee-deep in half-frozen water. The nights are bitterly cold. […] I have been having awful toothache lately. It nearly drove me dotty the other night.” But in this letter, and in contrast to his usual habit of referring to the Germans in highly derogatory terms, he conceded that the Bucks Battalion’s immediate opponents “fought finely” and were “a good crowd […], always cheery. One can hear them whistling and singing even in this horrible weather, and, barring an occasional deserter, [they] fight well.” It is almost as if the myth of the moral crusade against the barbarian Huns, which had sustained the British for the first two years of the war, was turning into the realization that the two sides were on an equal footing, both inextricably enmeshed in a horrible situation about which they could do precious little.

A day or so before 21 March 1916, when the Battalion was in the front line yet again (14–23 March 1916), the winter stalemate showed signs of a thaw and Crouch wrote to his mother:

We had a very cheery time the other night. Suddenly about 2 a.m. the very deuce of a bimbardo started like a thunderclap. Every conceivable gun from a 5.9 to trench mortar and machine-gun started on us and the Battalion on our right. It was the hottest thing we have had, and they must have put in at least a couple of thousand shells. Our guns, of course, at once opened with a barrage, and our machine-guns and rifles let rip. The Boche put across some gas and also fired stink shells, but my Company was hardly at all affected by that. We didn’t get the worst of the shelling either. The Boche infantry tried to attack, but he didn’t get far against our Battalion and never reached the wire. Evidently our machine-gun and rifle fire was too hot. […] Altogether it was great fun. The din of the guns, bursting shells, and machine-gun and rifle fire was beyond all expression. The bursting shells, rockets, and flares lit up the scene every now and then, and the smoke from the bursts hung about like a mist. After the show was over, the gas from the lachrymatory shells reached my Company’s headquarters. It was too weak to affect my eyes, but I had a sore and irritable throat and it made me cough until I was nearly sick.

But on 8 April 1916, either when the Battalion had just spent six days in billets at Bayencourt (2–8 April 1916) or was about to return to the Hébuterne trenches (8–16 April 1916), Crouch felt able to write to his father that “all our spirits are reviving under the influence of the better weather” even though, by early April, the Battalion’s casualties were starting to mount once more as a result of shelling, aggressive patrolling and German raids. But as soon as the bad weather set in again on 21 April, flooding the trenches yet again and depriving the men of sleep when the Battalion had just returned to them (21–25 April 1916) Crouch’s spirits fell and he concluded a letter to his father with the uncharacteristic complaint: “I’m dead tired and everything is too horrible.” During that night, sensing that a new unit had just taken over the British line at Hébuterne, the Germans attacked one of Crouch’s outposts with grenades, killing or wounding four of his men. He and a stretcher party managed to get one wounded man out, but the others, including a Corporal who had suffered seven wounds, lost his left foot, and been severely wounded in the back and his right leg, had to stay where they were “under a couple of pieces of corrugated iron with one dead man and two wounded all day [22 April 1916]”. It took four hours to get the wounded man from the outpost to the nearest dressing station:

He was carried along soaked to the skin and covered in mud and slime, lying in a stretcher full of rain-water and blood. It was a nightmare getting that chap along the trenches, knee-deep in water and pouring rain. I’ve had no sleep and I’m nearly dead. This is the worst I have had in over twelve months. I shan’t be able to lie down for another thirty-six hours.

But on 13 May he wrote to his mother from the trenches (10–16 May 1916): “The weather is extraordinary. Yesterday it was fine and hot, and the nights are always beautiful, but to-day is miserable and wet. You can’t imagine what a difference rain makes in the trenches.”

At last, on 18 May 1916, the Battalion began what looked like a period of respite well behind the lines, after moving c.12 miles westwards to Beauval, on the main road north–south (D916) and about three miles south of the market town of Doullens, where it stayed until 31 May 1916. But as long periods in the trenches were bad for men both physically and psychologically, it was required to open that stay with an 18-mile route march westwards, to the St-Riquier training area via Candas, Fienvillers, Baumetz, and Coulonvillers.

The Battalion did further training at Neuville (1–3 June) and Agenvillers (4–9 June), c.20 miles further over to the west and north-east of Abbeville, before returning on foot via Occoches (10 June) to the area of the quadrilateral mentioned above (11 June–7 July) in preparation for the coming Battle of the Somme (1 July–18 November 1916). From 22 June to 1 July the Battalion was in billets near the village of Couin, two miles west of Hébuterne – old and leaky huts in the woods that were known as “Bleak House” – where it lost five officers because of wounds and transfers to other units (the Royal Flying Corps and Machine-Gun School), followed by four days in the trenches near Hébuterne, with the German artillery becoming ever more active. Then, on 1 July, the first day of the battle, the Battalion marched four miles south to the village of Mailly-Maillet and bivouacked south-east of the village for two days in preparation for a night attack on the German positions. But the attack was called off at the last minute, possibly because the weather had been “too utterly detestable” so that “all the roads and tracks are ankle-deep in mud and just as bad as during the worst winter weather”. So on the evening of 3 July, the Battalion returned to its old huts in the woods near Couin and stayed there until 6 July. It was supposed to take part in the big push of 7 July, but as Crouch wrote to his father on that day:

our Corps [VIII Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Aylmer Hunter-Weston (1864–1940)] show was a bit of a wash-out. Our Brigade with others actually had orders to attack, and marched some way, and then the orders were cancelled. The men were furious. We were all very disappointed. I would rather go through anything in an attack than go back to this infernal trench monotony, but perhaps it will be only temporary.

So the Battalion returned to the trenches at Hébuterne on 8 July, and on 10 July, with the weather improving and the trenches drying out, Crouch discovered that his Battalion’s location gave him a view over the battlefield which he described as follows for the benefit of his father:

From my part of the trenches one can see where an unsuccessful attack was made. Our men were wearing tin triangles on their backs for the purpose of showing the advance to aircraft. One can see these triangles glittering in the sun, not only between the lines, but also between the various German lines. In front of the German trenches one can see bodies lying, some in heaps, others by themselves or in twos and threes. The German trenches are nearly flat and all their wire [has been] swept away. I was talking to a gunner officer who watched the advance, and he said that the accounts in the papers are quite true. The men were fine; they marched ahead under very heavy shell and machine-gun fire which simply mowed them down. The survivors went straight on, not running, but walking. The dead are lying out there in hundreds. What the place will soon smell like, I hate to think.

The Bucks Battalion came out of the trenches on 12 July 1916 and spent two days in the nearby village of Coigneux before being moved by motor-lorry to Senlis-le-Sec, about seven miles south of Hébuterne, on 14/15 July. From here, at 19.00 hours on 17 July, it set out on the three-mile march south-eastwards to Albert in order to take up positions to the south of the Albert-Bapaume road where, at 01.00 hours in the night of 17/18 July 1916, designated platoons from ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies, commanded by Birchall, reconnoitred six points in the enemy line, all of which were found to be so strongly held that the action cost the Bucks Battalion 62 men killed, wounded and missing. The reconnaissance group returned during the night via an erstwhile German communication trench and the Battalion’s War Diary recorded the experience as follows:

The trench which led us back presented one of the most gruesome sights we had yet seen, the floor being literally paved with the bodies of dead Englishmen. Nor was this all. Bodies lay over the parapet with rifle and fixed bayonet still held in the hand. Others were seated or lying on fire-steps in most lifelike positions. All had been killed at least a week previously, but burial parties had been too much occupied further back to reach them as yet. It was not difficult to picture how these men had come by their end – a German machine-gun skimming the parapet with deadly accuracy at the moment when our men were going over the top of it.

But as the reconnaissance mission was deemed to have established “the position and strength of the German dispositions in this neighbourhood”, the War Diary also recorded that “the Battalion received the congratulations of the GOC 48th Division”, Major-General Robert Fanshawe (1863–1946).

On 19 July, Crouch chanced upon the same trench while reconnoitring the battlefield and sent the following description to his father later that day:

From one point evidently one of our attacks had just started, because there were ladders up against the sides, and a clearer indication still, the results of the Boche machine-gun fire, in the shape of dead men lying on the sides in the attitude of going forward. It was extraordinary to see all these men lying there apparently asleep. About fifty yards of this trench was [sic] a veritable charnel-house; the dead were everywhere on the sides, in the floor of the trench. It was like walking through a bivouac of sleeping men. One had to step over and round them. I found one of my men sitting on one; he thought that it was a pile of sandbags! All this sounds very horrible and all that from home and peace-time standards, but it isn’t so really. We don’t worry over this kind of thing.

In the evening of 18 July the Bucks Battalion moved back to bivouacs at Bouzincourt, a mile or so north-west of Albert, for two days, and prepared to take part in the continuation of the assault on the German front line between Ovillers and Pozières that was planned for the night of 20/21 July 1916. The enemy trench that was the Brigade’s objective was about 325 yards away from Sickle Trench, the British front assembly trench, and the Royal Engineers had laid a tape 175 yards from and parallel with the German front line. So, at 02.30 hours on 21 July, ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies of the Bucks Battalion, with ‘B’ Company in support and Birchall’s ‘D’ Company in Reserve, moved forwards to the tape. But the Germans sent up flares and opened fire with a large number of machine-guns, and although a party consisting of a Corporal and 46 men managed to enter the German lines on the extreme right of the line, the attack was a failure and cost the Battalion four officers (including Crouch) and seven ORs (Other Ranks) killed in action, three officers and 97 ORs wounded, and one officer and 42 ORs missing. So at 09.00 hours on 21 July the Battalion was withdrawn to Albert and its War Diary commented: “The failure of this attack was a great blow to the whole Battalion, as it was our first serious attack, and it was as disappointed and sadder men that we made our way back to the bivouacs.”

But at 04.00 hours on 23 July 1916, Birchall’s Battalion was ordered to come out of Reserve and attack the left flank of the German line where the assault by the 5th Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Gloucestershire Regiment had recently failed. The attack, which involved a charge across several hundred yards of upward-sloping ground, was preceded by the issue of a rum ration to the men, a heavy artillery bombardment from 05.00 to 06.00 hours, and a secondary bombardment by field guns from 06.00 to 06.30 hours. But even while the field guns were still firing, ‘D’ Company, commanded by Birchall, and ‘B’ Company, now commanded by Captain Viney – i.e. the two Companies of the Battalion that had suffered the fewest casualties three days earlier – began to advance along the two communication trenches in order to stay under cover for the maximum amount of time while getting as near to their objective as possible. ‘D’ Company was on the right and ‘B’ Company on the left, but being closer to the German trenches, ‘B’ Company was also closer to the many British shells that fell short, causing many casualties. These then blocked the communication trench, making progress very difficult, and despite Viney’s best efforts, ‘B’ Company just failed to reach its forming-up positions in time to take any real part in the assault.

But Birchall’s ‘D’ Company got out of the trench safely, followed the British barrage as closely as possible, and rushed the German lines. The tactic worked, the German position was rapidly taken, and c.150 prisoners and two machine-guns were captured. A German officer later stated that the assault had taken them entirely by surprise as they were waiting for the barrage to lift before manning the parapet. Viney’s ‘B’ Company then came across in support, but when it was about 200 yards from the captured German trench, shell splinters badly wounded Viney in the abdomen and he had to lie out in the open all day. So ‘A’ Company was immediately sent for and contact was made with the 4th Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment on the right. In the evening ‘C’ Company of the Bucks Battalion took over the captured trenches; the Australians took Pozières on the same day; the German trench, which ran just south of the railway that arched around the north of Pozières, was captured; and by midnight, the German front line had been pushed back a good mile north of that village. So the Bucks Battalion was able to hand over its position to the 5th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment and return to its bivouacs near Albert, whence it was withdrawn to Arvèques on 26 July. Its casualties were relatively light – 88 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing – and the successful operation earned considerable praise from the Brigade and Army Commanders.

Unfortunately, after Birchall had gone some 50 yards towards the German trench, he was hit by either a bullet or a piece of shell, possibly a British one, which went through his pince-nez case and shattered his upper thigh. He was then dragged back to the British trenches by his orderly, Bugler Joseph (“Joe”) Edward Scragg (1892–1970), a very courageous action for which Scragg, a coachmaker in the railway works at Wolverton, was awarded the DCM, a decoration for ORs that ranked just below the VC. Birchall gave Joe the damaged case as a memento, and after the war the Birchall family sent him a cheque for £100 as a gesture of gratitude for his bravery. Later, when Birchall was lying on a stretcher, he was carried by a man from the 5th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment who lived within 200 yards of his home at Saintbridge and had been a member of his sister Violet’s Bible Class. Once back in the British lines, Birchall received first aid from inter alia his CO, Lieutenant-Colonel Lewis Leslie Clayton Reynolds (later DSO, TD, DL) (1882–1974), who was a surgeon in civilian life. But it took 36 hours to transport him and Viney by road and rail to No. 6 British Red Cross Hospital (the Liverpool Merchants’ Hospital) in the huge hospital complex at Étaples, some 50 miles away, and for the next four days, lying in the next bed to Viney, Birchall was often light-headed because of shell-shock and the drugs. At first, he began to recover, but on 9 August, not long after Viney had exchanged the hospital in Étaples for one in England, a piece of bone entered a blood vessel, causing a haemorrhage, and although this was stopped, the same thing occurred again with the main artery on the following day. This, too, was stopped, but the shock of the operation combined with the loss of blood was more than Birchall’s strength could bear and he died at about 14.30 hours on 10 August 1916, his thirty-second birthday and the day after G.H. Alington had been killed in action by a shell only a mile or so away from the place where Birchall had been wounded.

On 9 March 1916 Crouch had written in a letter to a friend:

Birchall says that he doesn’t want to get killed a bit. He wants to die at the age of ninety-five and be buried by the vicar and the curate, and his funeral attended by all the old ladies of the parish! He strongly objects to large objects of an explosive nature being thrown at him, and then his remains being collected in a sandbag and buried by ribald soldiery and dug up again two days later by a 5.9!

Ironically, on 22 July 1916, i.e. the day after Crouch had been killed in action at Pozières and the eve of his own wounding, it was Birchall who wrote a heartfelt letter of condolence to Crouch’s family. It said:

He is a terrible loss; one of the real old ante-bellum company commanders who knew all his men and their homes and their families – they all loved him. Personally I feel it very deeply; I don’t think anyone could help loving him – he was so absolutely simple and loyal and kindly – and about the only man I never knew depressed or worried. He was absolutely impervious to any worry or fear of the Boche – whenever we got to a new place he always judged it by its natural amenities rather than by the measure of the Huns’ offensiveness; frankly he never gave a damn for what the enemy did to him. He and I always rather felt like two remaining members of the old régime – they are almost all gone now. […] He did more than any other man to build up the Regiment, and then when it finally took its place in this great battle, he died in the front rank. I think you will get some consolation from that.

Shortly after Birchall had been hit, Lieutenant-Colonel Reynolds wrote to his family:

I feel I must write and tell you how awfully sorry we all are that he had been so badly wounded after his perfectly magnificent leading of his Company on 23rd, which resulted in the capture of a strongly-held enemy trench and secured the position of other troops, who would otherwise have been isolated and probably had to retire with heavy loss. It is no surprise to us who have served with him for so long and know how he has never spared himself when his men have been concerned, and know that where dogged pluck and perseverance would tell he was sure to come through

and a brother officer later judged Birchall to be “one of the finest officers the Battalion ever possessed”. He was awarded the DSO for his part in the action of 23 July and the news reached him via his Battalion on the day before he died. When the award was gazetted on 25 August the citation read: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in action. He led forward his company with great dash under heavy fire, entered the enemy’s trenches, and, though dangerously wounded, refused any assistance till assured that the position was firmly held.”

During World War One, Étaples, on the French coast about 17 miles south of Boulogne and known to British troops as “Eat Apples”, was the site of 16 large military hospitals and one convalescent depot, hence the size of the Cemetery depicted below.

Étaples Military Cemetery, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944), is the largest Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery in France and contains over 11,500 graves. 10,771 of these are British and Commonwealth graves from World War One, of which c.650 are German. It is just off the D940 to the north of the town.

When, on 11 August 1916, Birchall was buried in Étaples Military Cemetery (Grave I.B.4, inscribed: “Jesus saith … Thy brother shall rise again” – St John 11:23), his brother John and sister Violet took part in the funeral procession, together with the Chaplain, a bugler, bearers from the Highland Light Infantry, and hospital staff, including the Commandant:

As the procession moved at a slow march along the road, the traffic was stopped and several hundred infantry stood to attention. The last resting-place is in a hollow formed by a semi-circular sand-dune covered with Scotch firs and gorse, looking out over the sea, and side by side with many other Englishmen who have made the great sacrifice.

Many people subsequently wrote moving letters of condolence to his family. Another brother officer, who had known Birchall at Oxford, said: “I loved Edward, I joined the Battalion because he was there, he was a great and generous friend to me, I feel his loss dreadfully. I wish I could tell you of half the nice things people say of him, from the General downwards.” A third brother officer wrote:

Well, it is the saddest news we could have had … we feel that we have lost such a leader; he was the life and soul of our mess for ten years, and in everything he did, and most markedly in Company Organization, he always set a standard which we tried to reach according to our lights. I don’t think there is any lack of brave officers or of clever ones, but I don’t know when we shall find another such leader. Well, he and Percy are together again now. I don’t know where you’ll find two such splendid lives crowned with two such triumphant deaths.

President Warren also sent a letter of condolence to the Birchall family and on 17 August 1916 John Birchall replied to Warren as follows:

He seems to have succeeded with his Comp[an]y where 5 or 6 other attempts had failed to take a certain very difficult German trench, by passing through our own shell fire & so arriving at the German trench before they were prepared for the attack. […] What a burden will rest on those who are left to make England worthy of the tremendous Sacrifice! & what a bad beginning is being made by this mad cry for vengeance on the Hun! Nothing upset Edward more than this. He prayed he might never have to kill a German – & He has had his wish.” On 13 November 1916 he was mentioned in dispatches. (London Gazette, no. 29,890, 2 January 1917, p. 232).

Birchall is also commemorated on the Memorial to Staff of the Ministry of Labour which now hangs in Caxton House, Tothill Street, London SW1. He left £45,815 2s 10d, much of which went to charities: £1,000 went towards the setting up of the National Council of Social Services (from 1 April 1980 the National Council for Voluntary Organizations), whose purpose was to bring voluntary bodies into closer relationships with the relevant government departments. The legacy enabled the creation and ensured the sustainability of the Council, which now has 4,800 member bodies. Many well-established projects – such as Age Concern, the Citizens’ Advice Bureau, Marriage Guidance Councils, the Youth Hostel Association and the Young Farmers Club – began as projects under its aegis. Another £2,000 went to the Chairman of Buckingham Territorial Army Association to help the wounded members of the Bucks Battalion, together with their widows and dependents.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgement:

*Captain Lionel William Crouch, Duty and Service: Letters from the Front (London and Aylesbury: Printed for Private Circulation by Hazell, Watson & Viney Ltd., [January] 1917), especially pp. 29, 71, 96 and 132–3; reprinted by Forgotten Books (London, 2015); on-line at: https://archive.org/details/dutyandservice00crouuoft (accessed 13 March 2018).

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘The Agenda Club’, The Times, no. 39,450 (8 December 1910), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘The Agenda Club’ [letter], The Times, no. 39,500 (4 February 1911), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘The Agenda Club’, The Times, no. 39,522 (2 March 1911), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘The Cavendish Club’, The Times, no. 39,703 (29 September 1911), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘An Appeal for Social Workers’, The Times, no. 39,704 (30 September 1911), p. 3.

[Anon.], ‘Golf: Caddies Aid Association’, The Times, no. 39,764 (9 December 1911), p. 14.

The Helper, 6, no. 4 (April 1912), p. 49, [The Helper does not exist in any British Library].

A.A. David, ‘Letter’, The Times, no. 39,861 (1 April 1912), p. 12.

[Anon.], ‘Capt. E. J. Harvey …’, The Times, no. 39,874 (16 April 1912), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Public Health and the Insurance Act’, The Times, no. 39,897 (13 May 1912), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘The Employment of Caddies’, The Times, no. 40,036 (22 October 1912), p. 13.

[Anon.], ‘Golf: The Caddie Problem’, The Times, no. 40,054 (12 November 1912), p. 16.

W.E. Fairlie, ‘Letter’, The Times, no. 40,162 (18 March 1913), p. 13.

[Anon.], ‘The Caddies Aid Committee’, The Times, no. 40,390 (9 December 1913), p. 15.

[Anon.], ‘Captain Edward Vivian Dearman Birchall’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,245 (14 August 1916), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Died of Wounds: Capt. E.V.D. Birchall’, The Oxford Chronicle, no. 4,225 (18 August 1916), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Capt. E.V.D. Birchall’ [obituary], Gloucester Journal, no. 10,116 (19 August 1916), p. 6.

[Anon.], ‘Edward Vivian Dearman Birchall’ [obituary], Upton St Leonard’s Parish Magazine (Supplement) (October 1916), pp. 1–8; a copy is held in the MCA as PR32/C/3/141.

Captain P.L. Wright, DSO, MC, The First Buckinghamshire Battalion 191–1919 (Aylesbury: Hazell, Watson & Viney, 1920), pp. 24–35.

Günther (1924), p. 467.

Swann (1930), pp. 91, 96–9.

Mockler-Ferryman, i (24) (4.viii.1914–31.vii.1915), pp. 334–42; ii (25) (l.viii.1915–30.vi.1916), pp 320–30; iii (26) (1.vii.1916–30.vi.1917), pp. 27–51, 428–9.

F.E.F., ‘Sir John Birchall’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48,826 (17 January 1941), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Mr. Joseph Thorp’, The Times, no. 55,330 (3 March 1962), p. 12.

E.V. Knox, ‘Mr Joseph Thorp’, The Times, no. 55,332 (6 March 1962), p. 15.

David Verey (ed.), The Diaries of a Victorian Squire: Extracts from the Diaries and Letters of Dearman & Emily Birchall (Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1983). (Facing p. 114 are coloured pictures of the richly decorated hall and library at Bowden Hall.)

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 83.

Emily [Jowitt] Birchall, Wedding Tour, January–June 1873, and Visit to the Vienna Exhibition, David Verey (ed.) (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1985).

Helena Michie, ‘Victorian Honeymoons: Sexual Reorientations and the “Sights” of

Europe’, Victorian Studies, 43, no. 2 (Winter 2001), 229–51 (pp. 235–41).

McCarthy (1998), pp. 57–8.

Greenwell [2011], pp. 41–52.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR32/C/3/139–41 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letters relating to A.P.D. and E.V.D. Birchall [1915–1916]); includes a copy of the obituary of E.V.D. Birchall that was published as a Supplement to the Upton St Leonard’s Parish Magazine in October 1916.

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/50.

The Archives of the Ox. and Bucks. LI 10/4/J/1 (Box 52; E.V.D. Birchall’s Papers).

Although I have been unable to locate them, the Gloucestershire Archives allegedly contain letters from Jack Birchall while on active service, including an account of the death of Edward Vivian Dearman Birchall at Ypres (D3549/31/1/13 – sources for military history) (RWS).

Captain O[scar] V[aughan] Viney, ‘Reminiscences [1914–February 1917]’, photocopy of part of a privately produced book that was written after the 1950s and is held in the Archives of the Ox. and Bucks. LI within the Birchall Papers.

WO95/2763/2.

WO374/6518.

On-line sources:

‘NCVO’: https://www.ncvo.org.uk/ (accessed 13 March2018).

‘Bowden Hall: Parks and Gardens UK’ (with a detailed bibliography): http://www.parksandgardens.org/places-and-people/site/5811/history (accessed 13 March 2018).

‘Kelly & Birchall’, Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelly_%26_Birchall (accessed 13 March 2018).