Fact file:

Matriculated: 1908

Born: 19 October 1889

Died: 28 June 1915

Regiment: Royal Scots attached to King’s Own Scottish Borderers

Grave/Memorial: Twelve Tree Copse Cemetery: VII.C.8

Family background

b. 19 October 1889 at Inverleith House, Edinburgh, as the only son (second of two children) of the botanist Professor (later Sir) Isaac Bayley Balfour, MB, MD, DSc, LLD (Hon.), FRS, KBE (1853–1922) and Agnes Boyd Bayley Balfour (née Balloch) (1857–1940) (m. 1884). At the time of the 1901 Census the family were living at Inverleith House, Arboretum Road, Edinburgh (three servants). In 1922 the parents moved to Courts Hill, Haslemere, Surrey.

Parents and antecedents

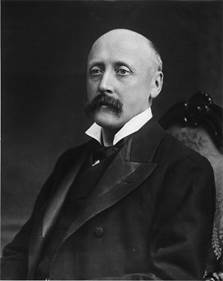

Balfour was the grandson of the distinguished Scottish botanist John Hutton Balfour, FRS, FRSE (1808–84), but his father had an even more distinguished career. He studied at Edinburgh Academy and Edinburgh University, where he was awarded a 1st in Botany (BSc) in 1873. He then studied under the botanists Julius von Sachs (1832–97) at Würzburg and Heinrich Anton de Bary (1831–88) at Strasbourg (the first Rector of the University there after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, and the founding father of plant pathology and mycology). In 1874 he served as botanist-cum-geologist on a primarily astronomical expedition to Rodriguez Island, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, where he wrote a report on the island’s flora that was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society and gained him a DSc from the University of Edinburgh. Almost six years after that, from January to April 1880, he led a second expedition to the Indian Ocean, this time to the island of Socotra, the “jewel of biodiversity” in the north-eastern part of the ocean (now part of the Yemen and since 2008 a UNESCO natural heritage site). Eight years later, his work here provided him with material for his most substantial work – The Botany of Socotra (published in 1888 as Volume XXXI of The Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh).

From 1875 to 1878 he was Lecturer in Botany at the Royal Veterinary College in Edinburgh, a post that required him to obtain medical qualifications (MB, CB in 1877, the year when he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh). But in 1879, i.e. before he was awarded an MD in 1883, he was appointed Regius Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow when he was only 26. Then, in 1884, he was elected FRS and became the Sherardian Professor of Botany at the University of Oxford, to which a Fellowship at Magdalen (1884–88) was automatically attached. Although he spent only four years in Oxford, he succeeded in reviving the neglected Botanical Garden (opposite Magdalen), and in 1887 he persuaded the Clarendon Press to found a quarterly journal – The Annals of Botany, the first botanic journal in the world – of which he became the first editor, and a series of translations of continental text-books. In 1888, like his father before him, he was appointed Queen’s Botanist in Scotland, Regius Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, and Professor of Botany at the University of Edinburgh (1888–1922). But even more than his father, he was a reformer and creative modernizer in all three institutions of which he was head, and his wife’s obituarist described the Royal Botanic Garden during his period of office as “the Mecca of botanists and keen gardening folk from all parts of the world”: the general public found a fine rock garden that Bayley Balfour had designed particularly attractive. Although his primary interest was the systematic study of rhododendra and primulae, particularly their Sino-Himalayan varieties, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes him as “the most effective all-round botanist in Britain”, who, according to his obituarist in The Times, “combined botanical science and practical horticulture in a marked degree”. The obituarist continued:

his knowledge of plants in the wilds, the garden, and the laboratory was profound, and he had an acute appreciation of the many problems presented in horticultural practice. To his knowledge and experience he joined an infectious enthusiasm and a felicitous power of exposition, with the result that his lectures and many erudite publications are models of lucidity. In addition, his knowledge of affairs and of human nature, his personal charm and his sound judgment were ever used with the sole thought of the advancement of science.

In 1897 he was awarded the Victoria Medal of Honour by the Royal Horticultural Society; in 1901 and 1921 he was awarded an LLD by the Universities of Glasgow and Edinburgh respectively; in 1919 the Linnean Society awarded him the Linnean Medal; and in 1920 he was made a KBE. Ill health, brought on by strenuous hard work, prevented him from accepting the presidency of the British Association and writing a history of Edinburgh’s Botanic Garden. When he retired in 1922, he and his wife moved to Surrey. He left £3,828 16s. 11d.

Professor Sir Isaac Bayley Balfour

(Photo courtesy of Glasgow University Archive Services: GB 248 ACCN 2116/15/13)

Balfour’s mother was the daughter of Robert Balloch (1825–1902), a Glasgow tea merchant.

Siblings and their families

Balfour was the brother of Isabella (also Isobel and Isabel) Marion Agnes (“Senga”) (b. 1885, d. 1925 at sea); later Aglen after her marriage in 1906 to Sir Francis Arthur (later Sir, GCMG, KBE) Aglen (1869–1932); three sons, two daughters. In 1927 Sir Francis married Anna Moore Ritchie (1884–1971), who had been employed as a nurse for the younger children since at least 1915.

Between 1888, when he joined the Imperial Chinese Maritime Customs Service, and 1900, Francis Aglen served in a number of posts in China: in Peking (now Beijing), Amoy (now Xiamen), Canton (now Guangzhou) and Tientsin (now Tianjin). In 1896 he was appointed to the rank of Deputy-Commissioner and in 1897 to the rank of Commissioner. Shortly after the Boxer Uprising broke out in 1900 he was posted to Shanghai as officiating Inspector-General while Sir Robert Hart (1835–1911) was a refugee under siege in Peking. In 1910 Aglen became the Deputy Inspector-General and in 1914 the Vice-Chairman of the National Loans Bureau. From then until he left the Service thirteen years later, Sir Francis, who was created KBE in 1918, was concerned not just with the prevention of smuggling and the assessment of duties and dues, but also with the management of the modernizing Chinese economy during a time of political instability when Chinese nationalism was in the ascendant. Consequently, Sir Francis found himself in an increasingly difficult position because of the growing tension between northern and southern China and in 1927 he was dismissed, albeit with honours and great courtesy, when he was unable to resolve a very difficult financial situation to the satisfaction of both sides. In the same year he was made a GCMG.

Education

Balfour attended Edinburgh Academy Junior School from 1896 to 1899, Bilton Grange Preparatory School, Dunchurch, near Rugby, Warwickshire (founded at Yarlet Hall Staffordshire 1873; moved to its present site 1887; cf. T.E.G. Norton) from 1899 to 1903, where he was Head of the School. From 1903 to 1908 he studied at Winchester College, where he spent three years in Sixth Book, the College’s most academic form, was Head of ‘F’ House (1906–08) and became the Senior Commoner Prefect (1907–08). He won the Holgate Prize (1904 and 1905), the Modern Languages Prize (1907) and the Wigram Cup for Racquets (1907). By 1906 he was a member of the Shakspere [sic] Society, where his “pleasant voice” was suited to female roles requiring “gentleness and sympathy”. He gave his maiden speech at a meeting of the Debating Society on 17 November 1905, when the question of conscription was discussed, and supported the usefulness of Volunteers. He was also a member of the “Sixteen Club”, founded in 1904 by L.W. Hunter. On 7 November 1907 he spoke knowledgeably about Peter the Great’s visit to England and on 25 June 1908, his final term, he read a paper on Party Government, “describing, first, the theory of Party and the advantage of the dual system over other forms of government; then the history of its growth in England from the accession of the House of Hanover to the present time, divided into two periods by the Reform Bill of 1832. Lastly, its prospects for the future, complicated by the formation of new groups, and the probability of electoral reform.” A moderately good cricketer, he was a member of the Winchester First XI in 1908 and so played in the match against Lord’s of 1908 when he was described as an “improving batsman” and a “useful slow bowler”, who, though “quick off the pitch” at present “played too many bad balls to get wickets cheaply”. He also played in the disastrous cricket match against Eton in July 1908, when G.B. Gilroy captained the XI after he had just recovered from an attack of the mumps which laid low another four out of five of Winchester’s first players. On this occasion, Balfour did reasonably well as a batsman, but as a bowler “soon lost his length and was dreadfully expensive”.

Photo taken from the group photograph of Magdalen’s First cricket XI (1909)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 14 October 1908 and was exempted from Responsions because he possessed an Oxford & Cambridge Certificate. He attended lectures in the Daubeny Laboratory and took part of the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1909. In summer 1909 he was a member of the College’s First cricket XI, six members of which (M.K. MacKenzie, G.B. Gilroy, H.M.W. Wells, the two Cattley brothers (C.F. Cattley and G.W. Cattley), and Balfour himself) would be killed in action. Delicate health then caused him to intercalate the Hilary and Trinity Terms of 1910 and go on a voyage around the world, but by Michaelmas Term 1910 he had recovered sufficiently to take the rest of the First Public Examination. He was awarded a 2nd in Literae Humaniores in Trinity Term 1912 and took his BA on 14 December 1912. Having decided that he wished to be a professional portrait painter, he studied drawing and painting at the Edinburgh College of Art from 1912 to 1914.

War service

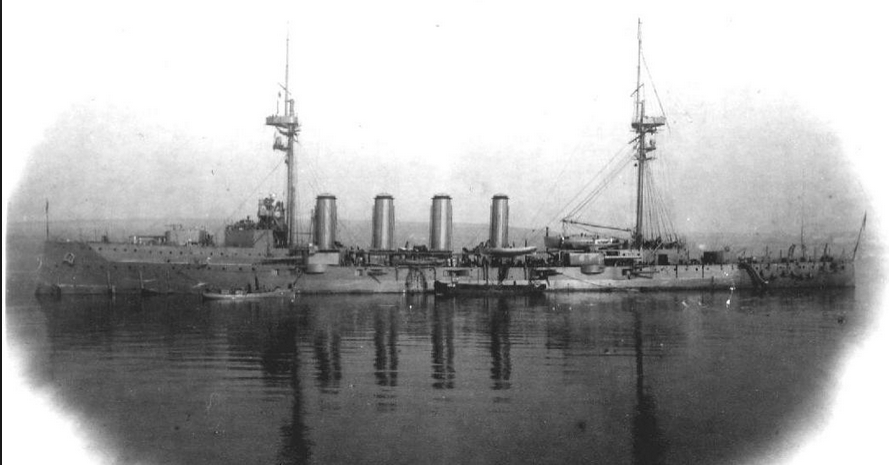

Balfour was 6 foot tall and probably in the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps throughout his time at Magdalen. He applied for a Temporary Commission on 24 November 1914 (London Gazette, no. 28,984, 24 November 1914, p. 9,695) and was commissioned Second Lieutenant on the same day in the 14th (Reserve) Battalion, the Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment). He was then attached to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion and promoted Lieutenant in January 1915 (LG, no. 29,065, 9 February 1915, p. 1,419), but was transferred to the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, part of 87th Brigade, in the 29th Division, in May 1915, when the 14th Battalion of the Royal Scots became the Regiment’s 2nd Reserve Battalion. The 1st Battalion had been mobilized on 11 September 1914, when it was stationed in Lucknow, India. It left Lucknow on 27 October, arrived at Bombay two days later, and sailed for England on the same day aboard the SS Sardinian, part of a huge convoy that increased its size at Karachi and was protected by the armoured cruiser HMS Duke of Edinburgh.

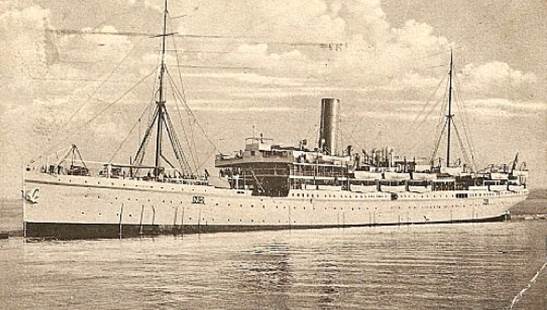

The 1st Battalion called in at Aden (9 November) and Suez (16 November), where it disembarked for Ismailia Camp as part of the 22nd Brigade in the General Reserve of the Suez Canal Defence Force. It stayed at Ismailia until 14 December 1914, when the Battalion’s 24 officers and 889 other ranks (ORs) embarked for Alexandria on the SS Geelong in order to leave Suez early on the following day.

SS Geelong (1904; sank 100 miles north of Alexandria with no loss of life on 1 January 1916 while en route from Sydney to London after colliding with another vessel)

The Battalion arrived at Gibraltar on 22 December 1914, and at Devonport on 29 December, where it entrained and was taken to Warley Barracks, near Brentwood, in Essex. It stayed here from 30 December until 19 January, when it travelled to Rugby, Warwickshire, where the newly formed 29th Division was assembling, in order to train here until 17 March. It then left by train for Avonmouth just two days after Major-General (later Lieutenant-General Sir) Aylmer Gould Hunter-Weston (1864–1940) had taken over as divisional commander.

The Battalion, consisting of 26 officers and 998 ORs, left Avonmouth aboard the HMT Dongola on 18 March, called in at Malta on 25 March, and arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on 29 March, where, with the rest of the 29th Division, it spent two weeks acclimatizing and training at Mex Camp, a few miles outside the city. But as Balfour had not yet been attached to the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB), his name does not appear on the list of officers who took part in this journey.

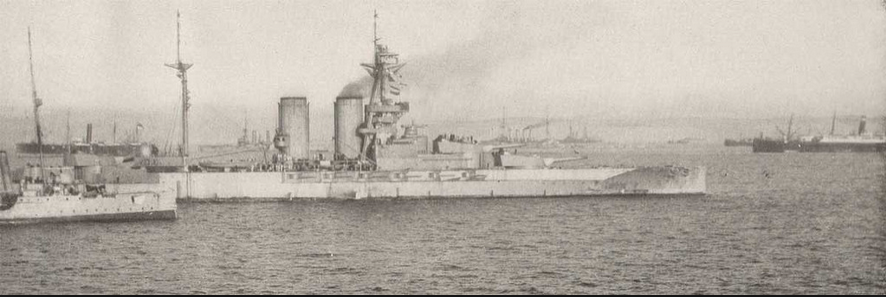

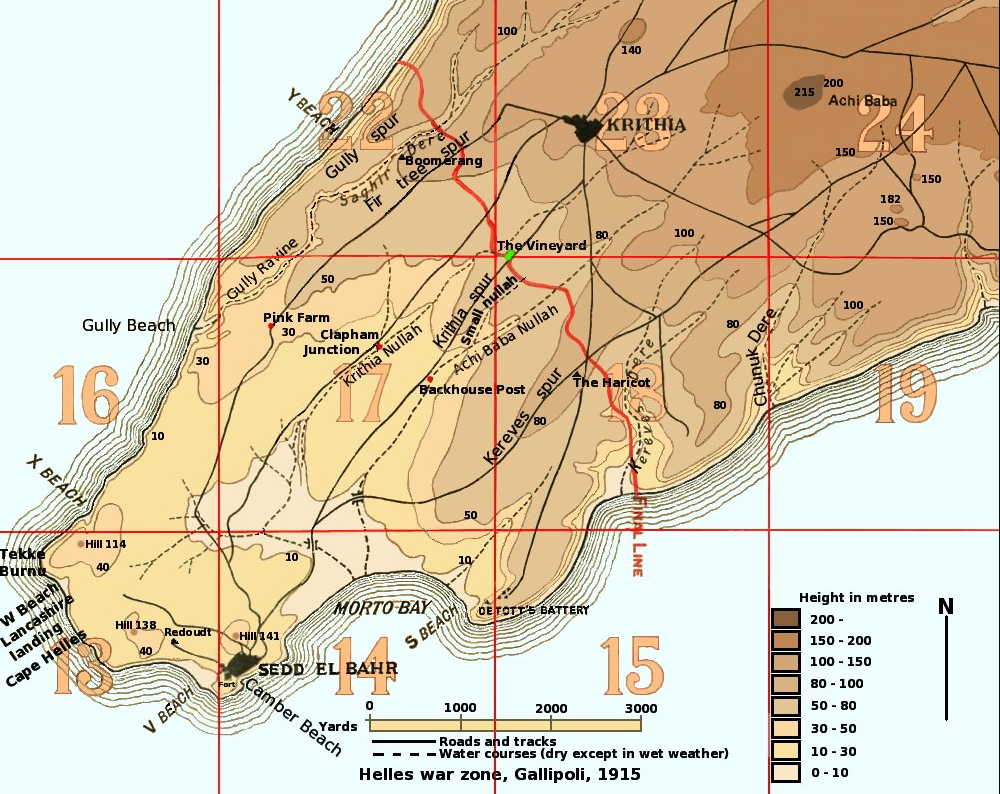

On 16 April 1915, the 1st Battalion of the KOSB embarked on the super-Dreadnought battleship the HMS Queen Elizabeth for the Greek island of Lemnos, half-way between the Peloponnese and the Gallipoli Peninsula. It arrived there on 18 April and, like the other Battalions in the Division, trained in the techniques of beach landings from small boats for a week. At 04.00 hours on 24 April 1915 the 1st Battalion of the KOSB, plus ‘A’ Company of the 2nd Battalion, the South Wales Borderers (see J.H. Harford), and the Plymouth Battalion of the Royal Marine Light Infantry in the 60th (Royal Naval) Division, together with the rest of the invasion force, embarked in Mudros harbour. Just over 12 hours later, at dawn on 25 April 1915, the 1st Battalion plus its two accompanying units landed in small boats known as cutters on ‘Y’ Beach, a narrow strip of sand on the western coast of the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, about five miles north from Cape Hellas (Hellas Burnu) and two miles west-north-west of the village of Krithia. Here, its principal task would consist in taking the strategically placed hill-top villages of Krithia and Achi Baba (Alçitepe), about another two miles past Krithia.

When the Battalion landed, the heavily laden men met no opposition and were faced with cliffs between 150 and 200 feet high, which they were able to ascend because the gullies leading up to the top of the cliffs were apparently undefended. At c.15.00 hours, the attackers, who had no spades or picks in their kit, formed a long, and therefore thinly held defensive semi-circle on top of the cliffs, using entrenching tools to make a shallow trench in the rocky ground. When patrols finally located the Turks, they were found to have retired in strength behind a ridge c.1,200 yards north of the Battalion’s left flank. At 16.00 hours the Turks, supported by machine-guns and artillery, launched the first of several counter-attacks against the thinly-held British positions, which continued throughout the night of 25/26 April and were driven off with bayonets. Another heavy Turkish attack at c.07.00 hours on 26 April caused the right and the centre of the British line to break, sending some men back down the cliffs to ‘Y’ Beach. But the 1st Battalion of the KOSB and the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers (see Harford) counter-attacked with bayonets and the Turks withdrew, having inflicted 697 casualties on the British battalions, 296 of which came from the 1st Battalion of the KOSB, including its Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Stephen Koe (1865–1915). As a result, the senior officer of the force on ‘Y’ Beach, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier) Godfrey Estcourt Matthews (1866–1917; killed in action at Cambrin on 13 April 1917) of the Royal Marine Light Infantry, decided that he no longer had enough troops at his disposal, and so, having heard nothing from Divisional Headquarters during the 29 hours on ‘Y’ Beach, began to evacuate his depleted troops from the poorly defended cliff-top, a procedure that was completed by about midday.

RMS Ausonia (1909; torpedoed by UB62 on 30 May 1918 with the loss of 44 lives 620 miles west-south-west of Fastnet when en route from Montreal to Avonmouth)

By the evening of 26 April, most of the survivors had been taken on board the RMS Ausonia, and early on 28 April, after a day at sea, the survivors of the 1st Battalion, the KOSB, landed on ‘W’ Beach and re-equipped. At about 11.30 hours the Battalion was ordered to rejoin 87th Brigade, which, with the 88th Brigade on their right and the 86th in Reserve, was advancing on Krithia – which at that time was unoccupied by the Turks and might have been taken by a concerted attack. But the men were exhausted, it was an extremely hot day, there was a shortage of senior officers after the fighting of the past few days, and units were getting mixed up.

So towards the evening the Division moved back 1,700 yards and dug in for the night. 30 April and 1 May 1915 were spent in Reserve on Gully Beach, about a mile below ‘Y’ Beach on the west coast of the Peninsula; then, just before midnight on 1/2 May, the Turks attacked en masse and were thrown back along the whole front line. From 3 to 7 May the Battalion alternated between manning the trenches in the front line and resting on Gully Beach, but on 7 and 8 May it took part briefly in the Second Battle of Krithia, in its western sector, by attempting to advance northwards up Gully Ravine, a deep valley with steep sides that ran parallel to the western coast at a distance of about 300 yards from ‘Y’ Beach and in the direction of Krithia. But costly attacks on 7 May, during the night of 7/8 May, and on the morning of 8 May were driven back by well-concealed snipers and accurate machine-gun fire, indicating that the Turks had, by now, created strong defensive positions on their side of the front line that now extended right across the Peninsula. On the evening of 9 May, after a quiet day, the Battalion went into Reserve in the low ground c.1,000 yards south of Pink Farm, so called because of the colour of the soil there, and by 12 May the entire 29th Division was out of the front line and resting for the first time in 18 days and nights. The Battalion stayed in that area until the night of 3/4 June, resting, bathing, doing fatigues for the Royal Engineers on the beaches, building roads and digging communication trenches. On 24 May the British Divisions in the south of the Peloponnese were grouped together as VIII Corps, with Hunter-Weston, a Temporary Lieutenant-General with effect from 24 May, as their GOC (General Officer Commanding). He was replaced as GOC 29th Division by Major-General (later Lieutenant-General) Henry Beauvoir de Lisle (1864–1955).

The Third Battle of Krithia – involving a frontal attack northwards by all the Divisions along the 4,000-yard-long front that was now known as the Eski Line – took place on 4 June 1915 after Lord Kitchener had ordered Hamilton to make a third assault on the two key strategic villages. The French were on the right of the line, with the Royal Naval Division on their left and the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division on the left of the Royal Naval Division. The 29th Division, reinforced by the 29th (Indian) Brigade, was on the extreme left of the line, i.e. next to the Aegean Sea, with the 1st Battalion of the KOSB in the trenches at 12 Tree Copse, the 4th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment on their left, the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers on their right, and the 29th Indian Brigade between the 4th Worcestershire Battalion and the Aegean. So, at 12.00 and 12.15 hours, at the end of a four-hour-long bombardment from large-calibre naval guns, nearly 80 British field-guns and howitzers, and quick-firing French 75s, aimed mainly at the barbed wire on the right of the line, two waves of infantry amounting to 30,000 men advanced along the whole length of the line with bayonets fixed. The first wave (20,000 men) was to take the first Turkish line of trenches and the second wave (10,000 men) was to charge through and take the two rear lines. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of the 1st Battalion of the KOSB had been tasked with attacking up the left side of Fir Tree Spur, but once the men had got across their own parapet, they walked into a hail of enfilading machine-gun and rifle fire which, as elsewhere along the line, killed or wounded most of them almost immediately. Soon after 12.30 hours, however, the two Indian Battalions and the 4th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment managed to reach the Turkish trenches, allowing the KOSB’s two remaining Companies to rush the trenches by platoons and capture 60 prisoners and a machine-gun. By 16.00 hours the entire attack had come to a halt and General Hunter-Weston ordered the men to dig in. But at 16.30 hours the Turks were seen massing in the communication trench that was held by the KOSB’s ‘D’ Company and were driven out of it by a bayonet charge. The War Diary of the 1st Battalion of the KOSB also records that at 18.00 hours ‘D’ Company managed to retake all the ground that had been lost when the Turkish attacked at 15.30 hours. Very little ground was gained as a result of the battle, especially on the two flanks, but it cost the victorious Turks upto 9,000 casualties and the Allies 6,500 men killed, wounded and missing.

The fighting continued on 7 and 8 June, but 10 and 11 June were much quieter, and it was probably on the first of those days that Balfour, who was in charge of about 60 reinforcements from the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion of the KOSB, landed somewhere on or near Gallipoli. His medal card actually says that he landed in France, but this seems unlikely given what happened next. On 12 June the 1st Battalion of the KOSB was relieved and withdrew westwards to bivouacs on the beach between Gully Beach and Gurkha Bluff, where it spent most of its time on fatigue parties until 17 June, when it moved up into the Reserve trenches near the White House, replacing the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers (London Regiment). During this period, on the night of 15/16 June, it is probable that Balfour was one of the four replacement officers who, according to the Battalion War Diary, were in charge of the 200 replacement ORs who had arrived to reinforce the Regiment’s 1st Battalion on Cape Helles. Over the next nine days, the 1st Battalion spent most of its time in the front line where it was involved in sporadic fighting and bombing, for which the Turks were better supplied than the Allies. On the night of 22 June two men crawled out into no-man’s-land and set fire to the Turkish dead with petrol because the stench of the corpses in the increasing heat of summer was making the British positions “untenable”. On 23 June the Battalion was relieved once more by the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers and spent the next four days on Gully Beach, resting and doing fatigues such as terracing the cliffs in order to turn them into better shelters. But on 27 June it moved back up the Gully to the front line in preparation for the Battle of Gully Ravine (Ziğin Dere), which began at 10.45 hours on the following day.

The outcome of the Third Battle of Krithia persuaded General Hunter-Weston that it was necessary to straighten out the two flanks of the Eski Line. So on 21 June 1915 the French contingent on the right-hand end of the line gained about 600 yards of the Kereves Dere (Kereves Ravine), a minor success which justified the attempt to do something similar a week later at the left-hand end of the line. On 28 June 1915, the battered 29th Division was instructed to move northwards along Gully Spur (see E.T. Young), reinforced by the 29th (Indian) Brigade and the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, borrowed from the 52nd (Lowland) Division, which had begun to arrive on Cape Helles on 6 June 1915, and whose task would be to advance along Fir Tree Spur (see Young). From 09.00 hours to 10.20 hours, heavy naval guns pounded the first three lines of Turkish trenches with high explosive and shrapnel; the Royal Field Artillery then fired on the dense Turkish barbed wire for 20 minutes; and the heavy naval guns then fired for a second time until 11.00 hours, when the infantry went over the top. The British also had 22 machine-guns at their disposal whose task was to enfilade the Turkish trenches between bursts of artillery fire. The Turks countered by bombarding the Allied artillery and the congested front-line British trenches, causing 156th Brigade significant losses. According to the 1st Battalion’s War Diary, the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers were the first Battalion in the Brigade to rush forward and capture the first Turkish trench near Gully Ravine (Ziğin Dere). ‘B’ and ‘A’ Companies of the 1st Battalion of the KOSB immediately followed through and took Boomerang Trench and Turkey Trench respectively, the first with very few losses, the second at considerable cost. They were followed at 11.15 hours by ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies, who leapfrogged the South Wales Borderers, linked up with ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies and tried to take Trench J11. But the Turks had made it difficult for attackers to get into that trench and it took the KOSB some time to discover how this might be done, during which they found themselves in an exposed position in no-man’s-land. Balfour, aged 25, must have met his death early on during this second phase of the attack, for according to subsequent reports he was killed in action during an assault on the second line of enemy trenches in the Gully Ravine area after another regiment had taken the first line: it seems that he “got his men into this 1st line and was killed getting out of this line to go on to the 2nd”. By 19.00 hours, the 1st Battalion of the KOSB had lost eight officers and 223 ORs killed, wounded and missing, but Balfour’s name does not appear in the casualty list – or, indeed, anywhere else in the Battalion War Diary – probably because he was a newcomer. But he was known to the Battalion’s Commanding Officer, who, on 5 July 1915, wrote a letter to Balfour’s parents in which he remarked positively on the way their son knew all his men and looked after them all.

Balfour was buried first in Gullyhead, or Geoghegan’s Bluff Cemetery (one of 925 British casualties from June/July 1915), then, after the Armistice, in Twelve Tree Copse Cemetery (south-west of Krithia), near Helles, Turkey. His grave, VII.C.8, is inscribed “Bay”. The diarist and Fellow of Magdalen C.C.J. Webb noted in his Diary on 10 July 1915: “Sad news of Bayley Balfour’s death in the Dardanelles: he was one of the most charming boys I ever had as a pupil”, and President Warren wrote of him posthumously:

he was more than [a young fellow of high intellectual ability]. He was brilliant and versatile, he had a lightness and quickness of perception and intuition, and at the same time a force of reasoning [which was] quite unusual and which must have carried him far in many lines had he been spared. He was also singularly winning and engaging, a delightful talker and companion, while his goodness of heart and absence of all self-seeking or self-consciousness endeared him to all who knew him. Truly his friends rejoiced in his light, and the shadow which his loss has brought is proportionately deep.

He died intestate, leaving £63 4s. 6d. in cash, but his estate was valued at £1,065 1s. 8d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgements:

*F.O. Bower, rev. D.E. Allen, ‘Balfour, Sir Isaac Bayley (1853–1922)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 3 (2004), p. 531.

Printed sources:

[Thomas Herbert Warren], [obituary], The Oxford Magazine, 34, extra number (5 November 1915), pp. 17–18.

Rendall et al., ii (1921), p. 174.

[Anon.], ‘A Great Botanist: Death of Sir Isaac Bayley Balfour’, The Times, no. 43,203 (1 December 1922), p. 15.

Günther (1924), p. 467.

Gillon (1930), pp. 123–59.

[Anon.], ‘Sir Francis Aglen: A Life of Service to China’, The Times, no. 46,144 (27 May 1932), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘Lady Balfour’ [obituary], The Times, no. 48,758 (28 October 1940), p. 7.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 83, 107, 113–16, 267.

Clutterbuck, ii (2002), pp. 22–3.

Chambers (2003), pp. 23, 32–8, 77, 81–2.

Ford (2010), pp. 218–42.

Gariepy (2014), pp. 187–223.

Archival sources:

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 1.

OUA: UR 2/1/65.

C.C.J. Webb, Diaries, Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1160.

WO95/4311.

WO339/16607.

On-line sources:

Wikipedia, ‘List of Turkish place names’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Turkish_place_names (accessed 29 July 2018).

Ian Hamilton, Gallipoli Diary, vol. 1 [Project Gutenberg EBook]: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19317/19317-h/19317-h.htm (accessed 25 July 2018). Vols 1 and 2 originally published in New York by George H. Doran Co., 1920.

Wikipedia, ‘First Battle of Krithia’: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=First_Battle_of_Krithia&oldid=797403088 (accessed 25 July 2018).