Fact file:

Matriculated: 1907

Born: 8 December 1888

Died: 27 November 1917

Regiment: Grenadier Guards

Grave/Memorial: Cambrai Memorial, Louverval: Panel 2

Family background

b. 8 December 1888 at Colham House, The Evelyns Preparatory School, Colham Green, Hillingdon, Uxbridge, Middlesex, as the fourth son (fifth child) of Godfrey Thomas Worsley (1842–1920) and Frances Worsley (née Hill) (1854–1947) (m. 1882). The above address was also the family home and by the time of the 1901 Census it accommodated, apart from Godfrey Thomas’s family and the 64 pupils, two assistant masters, one butler, one matron and eleven servants. By the time of the 1911 Census it accommodated, apart from the 42 pupils, two families (Godfrey Thomas’s and, from 1910, Evelyn Godfrey Worsley’s), two other assistant masters, one French Assistant, two matrons, two governesses and eleven servants.

The Worsley family can be traced back to the reign of Henry VII and came mainly from the gentry and professional classes.

Parents

John Fortescue’s father was the son of a clergyman; he was a schoolmaster who, after teaching at a preparatory school at Brading, Isle of Wight, in the 1880s and 1890s, came back to mainland Britain to become the Headmaster of The Evelyns School. In the nineteenth century there were several small private schools in the Hillingdon area, not least because of the proximity of Eton College. Evelyn’s School (founded 1872) was one of the most important of these private schools and maintained close connections with Eton until it closed in 1931.

John Fortescue’s mother was the daughter of the Reverend Melsup Hill (c.1818–91), who studied at Jesus College, Cambridge (BA 1840; MA 1868) and was then ordained deacon in 1841 and priest in 1842. From 1845 to 1857 he was Perpetual Curate of St John, Kidderminster, and in 1857 he became the Rector of Shelsley Beauchamp, Worcestershire, a living with a population of 572 and a stipend of £500 p.a.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Hugh Barrington (later Commander RN, DSO) (1883–1965); married (1908) Mary Elizabeth Joan Rashleigh (1887–1971); one daughter;

(2) Madeline Rose (1884–1949), later Rashleigh after her marriage (1909) to her second cousin Dr Hugh George Rashleigh, MRCP, LRCS (1876–1948);

(3) Evelyn Godfrey Worsley (1885–1917; died on 17 September 1916 of wounds received in action on the Somme, near Lesboeufs, while serving as Second Lieutenant with the 3rd (Regular) Battalion, the Grenadier Guards); married (1910) Katherine Maria Theodosia Rashleigh (1888–1974), the sister of Mary Elizabeth Joan; two daughters. She took the name Rashleigh again after her marriage (1919) to her father’s cousin, the Reverend William Rashleigh (1867–1937), the brother of Hugh George Rashleigh, the husband of her sister-in-law Madeleine Rose, and the second cousin of her late husband); one son, three daughters;

(4) Francis le Geyt (later Commander RN) (1886–1964); married (1914 in Rondebosch, South Africa) Irene Beatrice Guillemard (1891–1971); one son, one daughter (both b. in Nairobi, Kenya);

(5) John J. (1887–c.1889);

(6) Ralph Edward (1896–1971, in Palma, Spain).

Hugh Barrington entered the Navy on leaving school. He was gazetted Sub-Lieutenant on 15 July 1902, promoted Lieutenant on 3 January 1905 and by the time of his marriage he was a Lieutenant-Commander. He was awarded the DSO on 17 May 1918 (London Gazette, no. 30,687, 14 May 1918, p. 5,858) and mentioned in dispatches in the same year for services on the Mediterranean Station.

Hugh George Rashleigh (1876–1948), William’s younger brother, graduated in 1902 from one of the London hospitals and became a general practitioner in Chatham.

Katherine Maria Theodosia Rashleigh was the younger sister of Mary Elizabeth Joan Rashleigh, the wife of Worsley’s older brother Hugh Barrington, and both women were daughters of George Burvill Rashleigh (1848–1916) and Lady Edith Louisa Mary Bligh (1853–1904), the daughter of the 6th Earl Darnley (whose family seat since the eighteenth century had been Cobham Hall, North Kent, to the west of Chatham and the north of Maidstone).

The Reverend William Rashleigh was Hugh George’s older brother and the elder son of the farmer William Boys Rashleigh (1827–90) and Frances Portia Rashleigh (née King) (1836–1906) (m. 1863) of Horton Kirby, Kent. He had studied at Brasenose College, Oxford (BA 1887; MA 1889), and was ordained deacon in 1892 and priest in 1894, i.e. while he was an assistant master at Tonbridge School, Kent (1890–1900). After holding two curacies in Gloucestershire and Kent (1900–11), he became the Rector of St George the Martyr with St Mary Magdalene, Canterbury, from 1911 to 1916, and he then moved back to his home village. He finally became the incumbent of Ridgmont, near Bletchley, Bedfordshire, a parish of 494 people that was in the gift of the Duke of Bedford, with a stipend of £367 p.a.

Francis Evelyn George Rashleigh, DFC (1920–43) was the only son of Katherine, Evelyn Godfrey’s widow, and William Rashleigh; he married (1941) Alice Ann Hartley (b. 1919). He was gazetted as a Pilot Officer on 27 June 1939 and served in 202 Squadron, an Air Sea Rescue unit that specialized in picking up downed aircrew in Vickers Supermarine Walrus Mk II amphibian aircraft, and obtained his DFC, the Squadron’s first gallantry award for a rescue mission, in August 1941. While stationed in Gibraltar, he rescued the crew of an aircraft which had come down on the French Moroccan coast and been surrounded by 200 hostile Arabs. Rashleigh managed to land out of sight of most of the Arabs, but near enough for the crew to dash to safety. They scrambled aboard under fire and the pilot immediately turned the tail of his aircraft towards the enemy, opened his throttle, and hid their take-off behind a cloud of dust. After the cessation of hostilities in the Central and Western Mediterranean, the Squadron was moved to the Eastern Mediterranean, and at 13.30 hours on 30 September 1943, while flying a Walrus from Cyprus to Kos on a communications flight, Rashleigh, now a Flight-Lieutenant, was shot down off the island of Leros by Major Ernst Düllberg of JG27, flying a Bf. 109. Both Francis Evelyn and his navigator, Sgt Clifford Platt (1918–43), were killed in action, aged 23 and about 25 respectively. He and his wife had lived in Balcombe, Sussex, and the processional cross used in the village church has his name on it. He is commemorated on columns 267 and 271 of the Alamein Memorial and the War Memorial plaque in Balcombe Church.

Alice Ann Hartley later became Alice Ann Leigh-Bennett after her marriage (1948) to Thomas Neville Leigh-Bennett (b. 1915 in the Malay States, d. after 1970). He was the son of Harold Leigh-Bennett (c.1879–1949), who described himself as a Mining Engineer at the time of the 1911 Census and as a retired Civil Engineer in 1948, and who, in the late 1920s and 1930s, lived at Hillcrest, Beecham, Reading. Thomas Neville attended Shrewsbury School from 1929 to 1934, where he became a Praeposter and was a member of the First Cricket XI (1931–34) and the First Football XI (1932–34). After leaving school, he became an Exhibitioner at Brasenose College, Oxford, where he read Modern Languages (French and German) from 1934 to 1938 (3rd class BA), and he then became an Assistant Master at Sedbergh School, Yorkshire. On 22 February 1941 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps and he later became a Lieutenant. He married his first wife, Mary L. Poole (b. c.1919), a few months later in 1941. Their marriage was dissolved and at the time of his second marriage he was a trainee licensed victualler and living at the Royal Oak Hotel, Cobham, Surrey. In July 1950 his commission was transferred to the Secretarial Branch of the RAF Reserve and he was gazetted as Flight-Lieutenant. He later worked for the Department of Commerce and Industry, Hong Kong. His first wife remarried in 1949.

Francis le Geyt, like Hugh Barrington, entered the Navy on leaving school. He was gazetted Sub-Lieutenant on 30 November 1905 and promoted Lieutenant on 26 June 1908. Although he was transferred to the Retired List on 26 May 1913, he served in World War One with the rank of Commander. After the war, he emigrated to Kenya with his family and took up coffee farming.

Francis le Geyt’s wife, Irene Beatrice Guillemard, was the daughter of Dr Bernard J. Guillemard, a medical practitioner who had studied at Edinburgh and was the Assistant Astronomer at the Cape.

Francis and Irene’s only son, John Godfrey Bernard Worsley (1919–2000), came back to England to study Fine Art at Goldsmiths College, London, and began his professional life by producing illustrations for romantic magazines. On the outbreak of World War Two, he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and spent three years on escort duty in the North Sea and the Atlantic before becoming the youngest member of Sir Kenneth Clark’s team of official war artists. In 1943, he was made the official Admiralty artist in the Mediterranean, but later in the same year, while taking part in a raid on Italy, he was captured by the Germans who at first thought that he was a spy because of his drawing materials. But he was finally sent to Marlag O, near Bremen, where he assisted escapes by creating the dummy prisoner of war with a papier-maché head and movable ping-pong-ball eyes that is celebrated in the film Albert RN (1953) and is now in the Portsmouth Naval Museum. After the war, John Godfrey painted many portraits of the Allied leaders: 61 of his paintings now hang in the Imperial War Museum and 29 in the National Maritime Museum. Although he is best known for his seascapes, he also worked in glass, bronze and paint, made 700 drawings for TV versions of The Wind in the Willows and Treasure Island, and drew the illustrations for the comic strips ‘PC49’ and ‘Tommy Walls’ in the Eagle comic. In the late 1960s, he became Scotland Yard’s official police artist, making sketches for eye witnesses which proved to be more lifelike than photo-fits.

Ralph Edward was educated at Radley College, just south of Oxford, from c.1903–12 and probably trained as a solicitor since he became a Private in the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps (“The Devil’s Own”). He attested on 16 October 1914 and was subsequently commissioned into the 4th Battalion (Territorial Forces) of the Dorsetshire Regiment on 12 December 1914 (London Gazette, no. 29,003, 11 December 1914, p. 10,591). The 4th Battalion had been mobilized on the outbreak of war, trained for two months on Salisbury Plain, and set sail from Southampton on 9 October 1914, arriving at Bombay (now Mumbai) on 10 November. On 18 February 1916 the Battalion sailed from Karachi and landed in Basra on 23 February 1916, where it became part of 42nd Brigade, in the 15th Indian Division. For the rest of the war, it took part in the fighting in Mesopotamia. We do not know exactly when or where Ralph Edward joined the 4th Battalion, but he was in Alexandria, Egypt, when he was gazetted Captain on 21 November 1917. When a period of leave in England came to an end on 27 November 1918, he asked to remain there on compassionate grounds and was transferred to the Regiment’s 3rd Battalion, which had been stationed in Wyke Regis and served as the Portland Garrison since June 1915. After being demobilized on 3 July 1919, he worked from 1919 to 1928 with Messrs Turner, Morrison & Co. Ltd in Calcutta and Bombay, and from 1928 to 1930 with Messrs Holmes, Wilson & Co. in Calcutta. He seems to have given up professional work during the 1930s and lived at Hillcrest, Vine Lane, Hillingdon, and in Chartham, near Canterbury, Kent. During World War Two, he worked in HM Dockyard, Devonport.

Education and professional life

Worsley briefly attended The Evelyns School, Colham Green, Hillingdon, Uxbridge, Middlesex, whose Headmaster was his father (1872–1931; cf. R.A. Perssé, C.A. Gold, R.P. Stanhope, F.W.T. Clerke, T.G. Rawstorne, E.G. Worsley). He then, from c.1895 to 1902, moved to Cordwalles Preparatory School, Maidenhead, Berkshire (also known as the Reverend C.R. Carter’s Preparatory School); it was founded in Blackheath, moved to Maidenhead in 1873, renamed St Piran’s School in 1919 and closed in 1949 (cf. J.A.P. Parnell, P.F.W. Studholme). From 1902 to 1907 Worsley was an Exhibitioner at Winchester College in ‘A’ House, for which he played football, fives and golf. He also became a Commoner Prefect and a member of Sixth Book. One of the best runners of his time, he came fifteenth in the School’s Steeplechase in 1903, 4th in the same race on 10 March 1904, and on 14 March 1907 he finished a good first, 200 yards ahead of the runner-up, after running six and a quarter miles along a new course. He was also a member of the Debating Society and on 17 October 1906 spoke in favour of simplifying English spelling.

He matriculated at Magdalen as an Exhibitioner on 15 October 1907 and although he had been exempted from Responsions, he took and passed one of the Additional Responsions papers in Hilary Term 1908. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity Term 1908 and September 1908, and was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations in Hilary Term 1909, after which he changed from Classics to Law. He was awarded a 3rd in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1910 and took his BA on 27 October 1910. During his time at Oxford, he gained a Full Blue in Cross-Country Running: in December 1907 he was Oxford’s first man home in the Varsity race and in 1908 he finished third and was in the winning team. “In 1909 as Captain of the Oxford University Hare and Hounds Club he devoted himself to whipping in his team and he finished fourth” and after graduation he ran in the Thames Hare and Hounds and for the Uxbridge Athletic Club. He became a solicitor and after taking articles he left England in 1913 to enter a firm in Calcutta.

Military and war service

Worsley, who was 5 foot 8¾ inches tall, was in the Oxford University Volunteer Rifle Force from 1907 to 1908 and the Oxford University Officers’ Training Corps from 1908 to 1910. He returned home from India in July 1915, and applied for a Commission in the Special Reserve of Officers on 2 August 1915; was immediately accepted for the Reserve Battalion of the Grenadier Guards; and on 17 October 1915 he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 3rd (Regular) Battalion of that Regiment, in which R.P. Stanhope was the Commanding Officer (CO) of No. 3 Company. The Battalion had landed at Le Havre on 27 July 1915 and become part of the 2nd Guards Brigade in the newly formed Guards Division on 19 August 1915. Worsley landed in France on 28 October 1915 and joined No. 2 Company of the 3rd Battalion on the following day, when it was in billets at Norrent Fontes, about ten miles east-north-east of Béthune, manning a part of the front line that had become very quiet since the fighting of the autumn. It stayed here until 7 February 1916, when it began a long march northwards towards Wormhoudt, on the Franco-Belgian border, where it arrived on 22 February. The Battalion War Diary’s description of the Battalion’s movements then becomes confusing, but it spent the first six months of 1916 in and out of the line near Ypres, where:

the trenches […] were in a terrible state after the bombardment [to which they had been subjected during the First and Second Battles of Ypres]. The principal difficulty was that water stood in all the shell holes and the drains, of which there were very few, were blown in & the whole ground cut up. Another great disadvantage was that all the wooden revetments had been torn up & buried beneath the parapets and parados which made the work of clearing away the debris exceedingly slow.

The diary also records that because of snipers and the fear of an artillery bombardment, “not a spadeful could or can be lifted in the daytime and all work done at night has to be disguised as far as possible.” On 4 April 1916 Worsley left the Battalion for a while to go on a course so that he could become Trench Mortar Officer. The course probably lasted two weeks and took place at the Trench Mortar Training School at St-Venant. Until late July 1916, when the 3rd Battalion, together with the rest of the Guards Division, began to move towards the Somme, newly equipped with steel helmets, it alternated between five days in the front line of the Ypres Sector, five days in reserve on the Canal Bank west of Ypres, three days in Camp ‘B’ cleaning up, and five days in support in the battered town of Ypres itself. During the first half of June 1916, however, in anticipation of the coming battle, the Battalion trained at Volckeringhove, about seven miles north of St-Omer in Northern France, using models of German trenches.

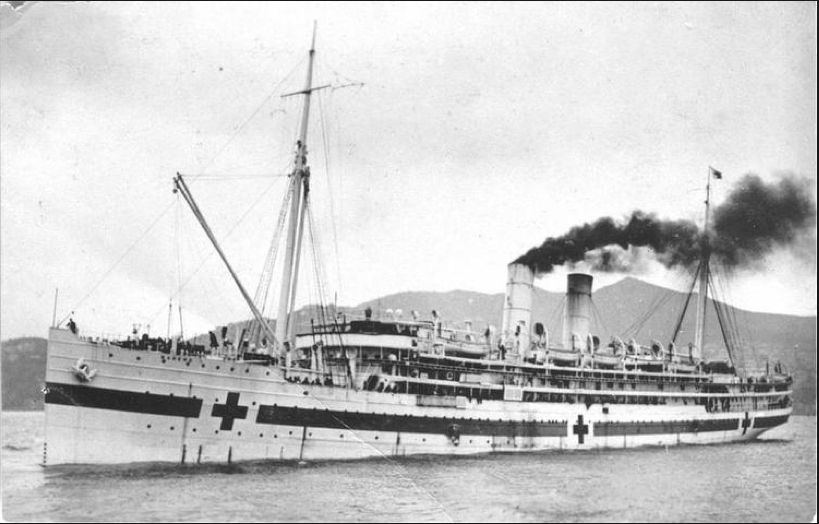

In early July 1916, Worsley’s right ear started to discharge and cause him pain, and as it was found that he had a slightly perforated right tympanum, he left his unit on 28 August 1916, crossed the Channel on 4 September 1916 from Le Havre to Southampton on the fast liner turned Hospital Ship HMHS Maheno (1905; beached off Fraser Island, off South Coast of Queensland, with no casualties on 7 July 1935 and gradually rotted into hulk). In England he was diagnosed as having otitis media that was affecting his hearing, and all but recovered after three weeks’ leave. According to a letter from Worsley’s father to President Warren of 3 October 1916, he was by then expecting “to be sent out to France very shortly”.

Meanwhile, on 30 July 1916, the Battalion had entrained at Esquelbecq, just to the east of Wormhoudt, and by 12 August it had reached the crossroads town of Doullens. By 17 August it was in billets at Morlancourt, “just behind Mailly-Maillet”, in the northern sector of the Somme front, and preparing for the coming Battle of Flers-Courcelette (15–22 September 1916; see H.W. Garton, E.K. Parsons, E.H.L. Southwell, R.P. Stanhope, H.D. Vernon, E.G. Worsley and H.R. Bell) by practising the newly prescribed techniques of open fighting for three weeks. The Battalion War Diary described these as follows:

The basis on which the formations were founded was that it was necessary to move all supporting troops simultaneously with those detailed for the actual assault in order to avoid the enemies’ [sic] barrage. Accordingly the Brigade was formed up in nine waves […] at 50 yards distance and at zero time all waves advanced together under cover of (1) a standing barrage on the enemies’ [sic] front line, (2) a creeping barrage starting 100 yds in front of the assault and moving forward at 50 yds per minute. When the creeping barrage reached the standing barrage, both lifted to 200 yards beyond the German front line. The leading waves passed over the front line and formed up behind the barrage. Standing barrage was then put down on to the second line. The front trench was cleared by the new waves.

As a result of his illness, Worsley was not with the Battalion by 9 September 1916, when it moved to Happy Valley, a track between low hills that led from the direction of Albert up to Bazentin-le-Petit, Mametz Wood and ultimately High Wood. It had been captured by the British on 14 July 1916 and was hidden from the Germans by the valley’s sides, but because they shelled it regularly, it was also known as Death Valley. Meanwhile, E.G. Worsley, Worsley’s elder brother, had landed in France on 12 August 1916 and joined the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards on 27 August, where he became a subaltern in Stanhope’s No. 3 Company. On 12 September 1916, the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards and the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards were in Reserve. But on the following day the two Battalions marched to Carnoy, and at 21.00 hours on 14 September they began to march by Coys via Trônes Wood and Guillemont to the assembly point behind the front line east of Ginchy, which the 3rd Battalion’s war diarist drily described as labouring “under every disadvantage except that it was not shelled by the enemy”.

Ginchy is situated two miles south of Flers on a high plateau that runs northwards for 2,000 yards, and then eastwards in a long spur for nearly 4,000 yards. The village of Lesboeufs is a mile-and-a-half south of the village of Gueudecourt and stands on the northern end of that spur, with the village of Morval on its southern end. Morval is two miles from Lesboeufs, two miles north-east of Ginchy, and commands a good view in every direction. Another spur juts out from the plateau for a mile in a south-easterly direction and then falls sharply into the Combles Valley towards Falfemont Farm (see W.L. Vince). Bouleaux Wood, a mile to the west of Combles, is on the crest of the spur, with Leuze Wood in front of it but lower down. The British extreme right at Leuze Wood was 2,000 yards from Morval and in between there lay a broad, deep branch of the main valley that is overlooked by Morval and flanked at its head by the high ground east of the valley that looks down into it. The Guards Division was positioned opposite this area, with the 6th Division on its right flank and the 56th (1/1st London) Division on its left flank, and was tasked with capturing Lesboeufs, an undertaking that was feasible only if the two flanking Divisions could be relied upon to clear the flanks and take Morval and Bouleaux Wood respectively.

When the Battle of Flers-Courcelette opened on 15 September 1916, Worsley’s Battalion – which, of course, he had not yet rejoined – was the Right Front Battalion and the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards was the Left Front Battalion of the 2nd Guards Brigade, with the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards immediately behind them as the Right Support Battalion next to the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Guards as the Left Support Battalion. Each of the four Battalions was formed up in four waves, with No. 4 Company and R.P. Stanhope and E.G. Worsley’s No. 3 Company in the front, and No. 2 Company and No. 1 Company behind them respectively, and there was a gap of 50 yards between each platoon. The attack by the Guards Division was supposed to be supported by 11 tanks, but only six arrived, and of these, two took no part in the battle, three got lost, and one ditched (see H.R. Bell, who commanded one of them). Worsley’s 3rd Battalion was in position by 03.00 hours and the men were issued with rum and sandwiches. Then, at 06.00 hours, the artillery of 6th Division fired 40 large-calibre shells, and at 06.20 hours the Guards began their attack on the two German strong-points known as the Triangle and the Serpentine under a creeping barrage. But the ground around Ginchy was “a battered mass of irregular ridges and shell-holes, which overlapped and stretched away into the early morning mist”, making it very difficult to establish a clear line of advance, especially since there were no landmarks. Conversely, the German machine-gunners had an unimpeded field of fire and the War Diary of the 3rd Battalion provides the following account of what happened next:

Our Left Front company [No. 4 Company] was met by machine-gun fire as soon as it got up & lost Captain Mackenzie [its CO] and Mr Asquith [Lieutenant Raymond Asquith (1878–1916), the Prime Minister’s son] at once. […] The last remaining officer of the Coy also fell within 200 yds of our own trenches.

But the Right Front Company (No. 3 Company) got off “much more fortunately & did not seem to lose until a considerable way out”. They managed to capture “a line of shell holes held by Germans 250 yards out” and killed everyone there, even though this simply “impaired the cohesion of the assault”. Then, despite the fact that their CO and most of their officers had been killed or wounded, the survivors succeeded in taking the first objective, the Green Line, 600 yards from the starting-line. On the right of the assault, the intense machine-gun fire made it impossible to go any further, but in the centre, a mixed group from various units of the 2nd Guards Brigade pushed forward past the Green Line for 800 yards and got near the second line of German trenches, only then to be compelled to fall back to the Green Line for lack of numbers.

So by the evening of 15 September, Worsley’s 3rd Battalion held a small frontage that was to the right of the first objective, and had to fight off enemy counter-attacks throughout the following night. The war diarist made the following comment on the day’s events: “It appeared that Les Boeufs would have fallen into our hands without opposition or at any rate with only an ill-organized resistance if more troops could have been pushed on”, and gave the following reasons for the assault’s very limited success:

(1) The Battalion’s left flank was/appeared to be unsupported s the 1st Battalion had started behind it;

(2) its right flank was completely exposed – not least because the 6th Division failed to advance in support of the Guards Division (they had been held up by a German strong-point called The Quadrilateral);

(3) the closeness of the attacking formation and the irregularity of the assembly trenches caused the waves to become muddled up;

(4) the Brigade tended to split up to the right and the left in order to cover its exposed flanks.

The attack cost the 3rd Battalion 395 ORs (Other Ranks), including a large number of specialist NCOs (Non-Commissioned Officers) and 17 out of 22 officers killed, wounded and missing. These included R.P. Stanhope, H.D. Vernon, who was killed in action south-west of Ginchy, and E.G. Worsley, who was mortally wounded less than two miles south of Flers, but whose name does not appear in the Battalion War Diary in connection with the above attack. This is possibly because he had been confused with his brother, who would not come back from sick leave in England until early October 1916. So on 16 September the Battalion was withdrawn to the Citadel, where 20% of its officers, the senior Company Sergeant Majors and a percentage of senior NCOs had been left to rebuild it in case such a disaster were to occur. On 20 September the Battalion was in bivouacs at Carnoy, and from 21 to 25 September, the day when the Guards Division attacked Lesboeufs for the second time and captured it, the 2nd Guards Brigade was in Reserve. So although Worsley’s 3rd Battalion took no part in this assault, it did spend 48 hours in the trenches from 28 to 30 September.

On 1 October 1916 the Battalion travelled by train to Heucourt, about ten miles south of Abbeville, where it trained until 9 November 1916, when it returned to the Somme front. Worsley must have rejoined it during this period, and at some time between 15 September 1916 and 1 April 1917 he was promoted Lieutenant. By 1 May 1917 he had moved to No. 4 Company.

After leaving Heucourt, the Battalion did stints in and out of the trenches near Lesboeufs until 6 December 1916; it then moved further south to Maricourt, where it repeated the exercise in the area of Bouleaux Wood until 25 January 1917, the day when it entrained for Méricourt, where it remained until 1 May 1917. It then alternated between resting and training for a month and a half, gradually moving towards the Ypres Salient as it did so, and it finally reached the vicinity of Elverdinghe, a few miles west of Ypres itself, on 16 June 1917. The 3rd Battalion spent the next six weeks in and out of line near Boezinghe, to the north-west of Ypres, and on the evening of 30 July, by which time Worsley was back in No. 2 Company, it was in position there on the west side of the north–south Yser Canal and ready to take part in the first phase of the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917) that became known as The Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July–2 August 1917).

Initially, the Guards Division had been ordered to cross the Yser Canal on 31 July 1917. But it was discovered on about 24 July that the German front line on the eastern bank had been obliterated by British artillery and that the Germans had been forced to withdraw 500 yards. Consequently, an unplanned and audacious river crossing on 27 July by the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, part of the 1st Guards Brigade, enabled the entire Division to cross the Canal during the nights of 29/30 and 30/31 July, by using rickety bridges made of petrol cans and without taking many casualties. It was then possible for the Division to establish a 400-yard-wide bridgehead on the Canal’s eastern bank. At 03.50 hours on 31 July, i.e. while it was still dark enough for the troops to avoid detection, the British barrage increased in intensity for six minutes, becoming a creeping barrage supplemented by machine-gun fire. Whereupon the Guards Division, led by the 3rd Guards Brigade on the left and the 2nd Guards Brigade on the right, with the 1st Brigade behind them in support, advanced eastwards along the north side of the Ypres–Staden railway and diagonally across Pilckem Ridge, in company lines, 100 yards apart, with the French First Army to their left, and the 38th (Welsh) Division, part of XVIII Corps, to their right advancing along the south side of the railway, supported by several tanks (see D. Mackinnon).

The attack had been meticulously planned and rehearsed, and was so carefully executed that the Guards Division captured all three of the primary objectives that had been assigned to it: Blue Line (500 yards from the Canal), Black Line (1,750 yards from the Canal), and Green Line (2,750 yards from the Canal). But after the Guards had reached Blue Line and taken it without much difficulty, the enemy resistance stiffened: the area was dotted with well-camouflaged snipers and pill-boxes, and the 3rd Battalion lost two officers killed in action, four officers wounded, including Worsley on 31 July, whose No. 2 Company was on the left flank of 3rd Brigade. It also lost 151 ORs killed, wounded and missing. On 1 August the Battalion was withdrawn to a rest area for four days and then spent three more days in the trenches before being withdrawn to Putney Camp, somewhere near the Franco-Belgian frontier between Proven in Belgium and Herzeele in Northern France.

It stayed in the Ypres Salient – mainly resting and training, but with periods of activity in the front line (see W.A. Fleet) until 9 October, the one-day phase of the Third Battle of Ypres that became known as the Battle of Poelcapelle. Worsley took part in this action, having returned to the 3rd Battalion from hospital on 16 August 1917. As on 31 July 1917, the Guards Division was positioned at the very northern end of the front, and was tasked this time with crossing the River Brombeek and taking three objectives, starting roughly from the Green Line of 31 July 1917 and advancing on a 1,200 yards front for about another 4,000 yards along the north side of the Ypres–Staden railway to the village of Veldhoek. The attack began at 05.20 hours, but the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards and the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards were held back until 07.30 hours, when the Brombeek had been crossed and the first objective secured. The two Battalions then pushed forward to the second and third objectives, and during the fighting Worsley’s Battalion captured 93 prisoners, four machine-guns, two trench mortars and two field guns but lost 84 of its number killed, wounded and missing. Sergeant John Harold Rhodes, DCM and Bar (1891–1917), a member of Worsley’s Battalion, was awarded a VC for single-handedly capturing a block-house using grenades and making most of its garrison surrender.

Worsley’s Battalion stayed in line on 10 October before going out of line on the following day and then resting for a month. It took no further part in the Third Battle of Ypres, and spent the last ten days of October and the first week of November in good billets. But on 10 November it began a fortnight of hard marching in heavy rain, “invariably at night” for the sake of secrecy, south-eastwards across France with no clear goal, through Heuchin, Hernicourt, Houvin, Bailleulval and Courcelles-le-Comte (seven miles north-east of Bapaume), but always towards the Hindenburg Line, where a major British offensive was developing west of the pivotal town of Cambrai. III and IV Corps had started the attack on Cambrai at dawn on 20 November, and because of their losses during the first three days of the fighting, the advance of the Guards Division towards the Cambrai Sector was accelerated. So during the next few nights the 3rd Battalion marched through Achiet-le-Petit (22 November), Rocquigny, further to the south-east (22–23 November), and Lebucquière (23 November), just to the south of the Bapaume–Cambrai road and about ten miles west-south-west of Cambrai. The Battalion’s march ended at 07.00 hours on 24 November at Ribécourt-la-Tour, about seven miles due east of Lebucquière and about five miles south-south-west of Cambrai. It was then allowed to rest for a day before taking up position on 26 November on the south-eastern edge of Bourlon Wood, opposite the village of Fontaine-Notre-Dame that lay about three miles west of Cambrai and just south-east of the village of Bourlon and Bourlon Wood (see A.H. Villiers).

It was originally intended that the Guards should break out to the north after the 51st (Highland) Division had captured Fontaine-Notre-Dame. But because the 51st Division had left that village in German hands after the initial fighting, having lost 68 officers and 1,502 ORs in the process, two of the Guards Brigades that had recently arrived in the Sector from the Ypres Salient – the 1st and the 3rd – relieved 152nd and 153rd Brigades just to the west of Fontaine-Notre-Dame in awful weather during the night of 23/24 November. The 1st Guards Brigade were positioned in the front line, with the 3rd Guards Brigade in support at Flesquières, two miles to the south beyond Anneux, and once Worsley’s 2nd Guards Brigade had arrived at Ribécourt-la-Tour, it took over as the Reserve from 51st Division’s 154th Brigade.

The three Guards Brigades remained in these relative positions for two days, but because Bourlon Wood and Bourlon village had not been captured by the evening of 26 November (see A.H. Villiers), Sir Douglas Haig, the GOC (General Officer Commanding) of the British Expeditionary Force from 1915 to 1918, decided to resolve the situation by having the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division, supported by 20 tanks, and the Guards Division, supported by 14 tanks, attack eastwards on 27 November in order to take Bourlon and Fontaine-Notre-Dame respectively. The GOC of the Guards Division, Major-General Geoffrey Feilding (1866–1932), had already offered several written objections to the plan. In his view Fontaine was well defended; when the Guards attacked across open ground into the Bourlon Salient, they would be vulnerable to artillery fire from three ridges – west of Cambrai, north of Bourlon Wood, and east of the St-Quentin–Escaut Canal; the front was too wide; and he had only six fresh Battalions, as the Guards Division had taken 3,000 casualties killed, wounded and missing during the fighting of October in the Ypres Salient. There were also, as Haig knew well, no reserves available to hold the two villages once they had been captured.

So during the night of 26/27 November, Feilding decided to take the 2nd Guards Brigade out of Reserve and move it eastwards so that it could be deployed in the following way on the morning of 27 November. It would have three objectives: first, a line that ran through the road junction at the eastern end of Fontaine-Notre-Dame to the northern end of Bourlon Wood; second, the station and eastern outskirts of Fontaine-Notre Dame; and third, the south-eastern outskirts of and road that ran south-eastwards from Fontaine-Notre-Dame to La Folie Wood, about 1,000 yards away. The 2nd Battalion, the Irish Guards, commanded by the future Field Marshal Harold Alexander (who survived the battle unhurt), would be on the left flank of the attack, with its left flank protruding into the deep mud and tree roots of the south-eastern corner of Bourlon Wood, and concentrate on the first objective; the 1st Battalion, the Coldstream Guards, would be on their right and concentrate on the second objective; and Worsley’s 3rd Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, would be on their right, in the open, straddling the main road into Cambrai and directly opposite the western entrance of Fontaine-Notre-Dame some 600 yards away from the village church, and concentrate on the third objective. Finally, the 2nd Brigade’s fourth Battalion, the 1st Battalion, the Scots Guards, was to move south-eastwards to the nearby village of Cantaign-sur-Escaut in order to guard the right flank of the other three Battalions and make contact with the 3rd Battalion of the Grenadiers by advancing north-westwards up a sunken road. Meanwhile, the 3rd Guards Brigade, including N.G. Chamberlain’s 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, would stay six miles to the south-west in the area of Havrincourt/Ribémont-la-Tour so that it could act as a defensive reserve in the case of a German breakthrough.

So, at 06.20 hours on 27 November, with the previous night’s snow turning into an icy drizzle that impeded visibility, and in almost total darkness, the attack began on an enemy who was expecting it and had over twice as many artillery pieces at his disposal. The 62nd Division got into Bourlon for a short time, losing 79 officers and 1,565 ORs in the process, while not far to the south, the two left-hand Battalions of the 2nd Guards Brigade fought their way into Fontaine-Notre-Dame, losing about two-thirds of their men killed, wounded and missing while taking hundreds of prisoners and capturing some field guns and machine-guns. But on the right of the attack, the two right-hand companies of the Grenadier Battalion (No. 1 Company and Worsley’s No. 2 Company, both of which were out in the open), were soon held up by uncut wire. They also came under concentrated machine-gun fire from La Folie Wood, on their right, and lost all their officers and the majority of their NCOs and ORs killed, wounded and missing. But the two left-hand Grenadier Companies (No. 3 and No. 4) got into Fontaine-Notre-Dame by 07.40 hours despite heavy machine-gun fire from fortified German positions in the mass of isolated houses that constituted the village and were ideal for defence, and joined in the vicious hand-to-hand fighting in the houses and narrow lanes there. Such tanks as got into the village arrived late, and a small number of reinforcements from the 4th Battalion of the Grenadier Guards were sent forward to help. But the Germans brought up large numbers of reinforcements and counter-attacked into the village, where the officer commanding the British troops realized that a 100-yard gap had opened up between his men inside the village and those elements on its southern side and that the Germans were trying to invest it. So rather than be surrounded, he ordered his men to withdraw from Fontaine-Notre-Dame.

It was later reported that 600 Germans had been taken prisoner, but by 13.00 hours on 27 November 1917 the 2nd Guards Brigade had lost 1,043 ORs and 38 officers and retired to its initial positions. Worsley, who was initially recorded as missing, was killed in action, aged 28, at almost exactly the same time as Second Lieutenant Gavin Patrick Bowes-Lyon (1895–1917), the CO of No. 3 Company, a cousin of the future Queen Mother and one of her three close relatives to be killed in action during the war. Worsley’s CO later wrote: “[Worsley] was absolutely unperturbed, and with any amount of guts. He must have done most awfully well on November 27 to have got as far as the place where he was seen to be lying dead.” Worsley has no known grave, and is commemorated on Panel 2 of the Cambrai Memorial, Louverval, which is situated on the north side of the major road that runs between Bapaume and Cambrai. He left £111 5s. 2d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special acknowledgement:

*Horsfall and Cave (2002), pp. 60, 74–85, 153–61.

Printed sources:

[Anon.], ‘Lieutenant John Fortescue Worsley’ [obituary], The Times, no. 41,742 (30 March 1918), p. 5, col. E.

Ponsonby (1920), ii, pp. 7, 86–107, 154–6, 169–71, 200–34, 253–8, 269–84, 338–48.

Rendall et al., ii (1921), p. 170 (photo).

Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 24, 52, 115.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 100–01, 117.

Archival sources:

MCA: PR/2/19 (Magdalen President’s Notebook 1917, p. 78).

MCA: PR 32/C/3/1239 (President Warren’s War-Time Correspondence, Letter relating to E.G. and J.F. Worsley [1916]).

OUA: UR 2/1/64.

WO95/1217.

WO95/1218.

WO95/1219.

WO339/36711.

WO374/76912.