Fact file:

Matriculated: 1904

Born: 19 March 1886

Died: 15 September 1916

Regiment: Rifle Brigade

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Pier and Face 16B and 16C

Family background

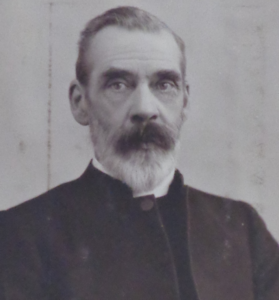

b. 19 March 1886 as the only child of the Reverend Canon Herbert Burrows Southwell, MA (1856–1922) and Mrs Sarah Ann (“Annie”) Southwell (née Willis) (1858–1934) (m. 1883), 5.5 College Yard, Worcester.

Reverend Canon Herbert Burrows Southwell, MA (1882)

(Photo courtesy of Dr David Morrison, Librarian/Archivist of Worcester Cathedral; © and by kind permission of The Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral)

Parents and antecedents

Southwell’s father was the son of a land surveyor and studied Classics and Theology at Pembroke College, Oxford (1876–80; BA 1880; MA [Oxon.] 1882; MA [Dunelm.] 1882), where, in 1881, he was awarded the Denyer and Johnson University Scholarship in Theology; he also rowed for the Pembroke VIII. He was ordained deacon in Oxford and priest in Durham in 1881, and in the same year he became the Curate of St Mary the Virgin in Oxford. Soon after that he became domestic chaplain to Bishop Joseph Barker Lightfoot (1828–89), the scholarly Bishop of Durham, who had been the Hulsean Professor of Divinity, Cambridge (1861–71), and Lady Margaret’s Professor of Divinity, Oxford (1875–79). From August 1885 to February 1901 Southwell’s father was Principal of Lichfield Theological College (1857–1972), at that time a small institution of between 13 and 20 students.

A friend described him as “a very virile personality and [a] deeply earnest and spiritual character” who was “strict but sympathetic” and a shrewd judge of character: “a man’s man”, a judgement that will be entirely borne out by the letter that he wrote to Present Warren after his son’s death and is reproduced below. From 1901 to 1912 Herbert Southwell was the Principal of the Bishop’s Hostel in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and a Canon Residentiary of Newcastle Cathedral, and from 1912 until his death in a cycling accident in 1922 he was a Canon Residentiary of Worcester Cathedral and the priest-in-charge of the small village church of Whittington, around two miles south-east of Worcester. It is said that Evelyn’s death in the war was a “blow from which he never really recovered”.

Evelyn Herbert Lightfoot Southwell, BA; two details from group photos of the Rupert Society (c.1906 and 1907)

(Photos courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

Education

From c.1892 to 1899 Southwell attended Yarlet Hall Preparatory School, near Stafford (founded in 1873 by the Reverend Walter Earle (1839–1922), who was its Headmaster from 1873 to 1887, when he moved to Dunchurch, near Rugby, to set up Bilton Grange Preparatory School). From 1899 to 1904 Southwell was a King’s Scholar at Eton College, where, from 1901 to 1904, he was a member of the Eton College Rifle Volunteers, rising to the rank of Lance-Corporal in 1904; he also rowed in ‘Victory’, one of Eton’s “Upper Boats”, in June 1904. He was elected to a Demyship in Classics at Magdalen on the same day as Maurice Powell and matriculated there as a Demy (Scholar) on 18 October 1904, having been exempted from Responsions.

Evelyn Herbert Lightfoot Southwell, BA; detail from a group photo of the Magdalen College VIII (1905)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

On 30 January 1905 Southwell began training as stroke with Magdalen’s 2nd Torpid VIII, and in mid-February 1905 he made his début as a Magdalen oarsman when he stroked that crew in the Torpids races with Duncan Mackinnon at No. 5. He was subsequently described by Magdalen’s Captain of Boats as showing “by far the most promise & ought to make a good racing stroke”, but with the reservation that “he must learn to give his heavy men more time at the finish”. Nevertheless, he acted as stroke when, on 8 May 1905, Magdalen’s 1st VIII began training in earnest for the Summer Eights (24–31 May) with a crew that included G.C.B. James at No. 2 and L.R.A. Gatehouse at No. 4. But James Douglas Stobart (1884–1970; Magdalen 1902–05), the Secretary of Magdalen College Boat Club 1904/05, was implacably negative about the crew’s initial efforts and described them in the Captain’s Book on 8 May as “Very bad row. Very short, no swing, no rhythms. Bucket of the barges”. (“Bucket” is an archaic slang word referring to an inexperienced or newly formed crew who are uneven on their slides and not in rhythm, thereby impeding the boat’s smooth forward motion.) Stobart registered a “slight improvement” on 9 May and this continued on the following day; on 13 May he described the row as “very [slow] & much too slow over the first half of the course”; and by 15 May his view of their performance had declined to “Rotten”. On 16 May Stobart called the crew “exceedingly slovenly” and lacking “life, leg drive, & swing”; and on 17 May he once more described it as “exceedingly slovenly” and spoke of

a most unsatisfactory row for we were again very slow over the first part of the course. […] but from the boat house in it was a dismal bucket; & no-one seemed properly rowed out at the finish owing to saving them selves [sic] at the start.

So a new coach took over the training “& by dint of a few home truths seemed to wake the crew up & instill [sic] some idea of rhythm into us, & by making us row a faster stroke showed us that we could”. Consequently, by 20 May Stobart considered the rowing to be “on the whole better” and showing “more drive, length & swing”, an improvement that continued on 22 May. So when the races started on 24 May, in “fine weather & good rowing conditions”, Magdalen rowed well and at the end of the day finished Second on the River, just behind New College. But Magdalen’s performance then improved so significantly that on the second day they went Head of the River and Stobart left us the following description of this feat:

The first night New College started Head of the River with Magdalen 2nd. Magdalen got away well, rowing 39 strokes in the first minute but gained very little at first on New College; till in the straight bit before the Gut we were called upon to “give her ten”. The crew answered well &, having settled down a bit by then, began to row long and hard & immediately commenced to gain. The advantage was considerably increased coming out of the Gut owing to superior coxing on our part, but at the Green Bank New College began to draw slightly away. It was a despairing effort however, for just before the crossing Magdalen again began to draw up fast & [with] our Cox taking a beautiful course, we effected our bump just opposite the boat house & went Head of the River.

So on the following days, the Magdalen crew were not “really troubled” by their main rivals – New College, University College, and Christ Church – and on the final day of the races (31 May 2005) they passed the winning post “well out of our distance” away from them. Then, when assessing the performance of the individual members of the victorious VIII, Stobart was uncharacteristically complimentary about Southwell’s contribution to Magdalen’s victory:

E.H. Southwell; rather apt to cut the finish & hurry his heavy men. If he learns to hold the finish out & get a truer beginning from the Stretcher[,] he will make a very good stroke. He races exceedingly well, & altho’ it is his first year in the eight[,] his coolness, even when Univ. came upon us at the start in the way that they did, was remarkable. Still nothing ever could destroy his habitual sang froid. To him, more than to any other individual in the boat I think (during the races)[,] is the credit due for our having kept away from Univ; for if he had lost his head in the slightest degree & hurried us ever so little at the critical moment[,] there was every possibility, & even probability, of our going to pieces. Instead of hurrying tho’ he kept the stroke long & enabled us to settle down. Magdalen are lucky to have at last found another good stroke.

So we can assume that Southwell participated with considerable enthusiasm in the orgiastic Bump Supper that followed Magdalen’s victory on 31 May 1905 and is described in great detail by G.M.R. Turbutt.

In October 1905 Southwell sat the first part of the First Public Examination and in the first week of November 1905, he, together with L.R.A. Gatehouse at No. 2 and A.G. Kirby at No. 3, was in the crew that won the coxless IVs against Trinity (first night), St John’s (second night), and New College (third and final night). Once again, Southwell at stroke was singled out for special praise:

At Weir’s Bridge the positions were unchanged, but Magdalen took the next corner rather too close & New College came up a little: however, we reduced this gain [when] going through the Gut & were a little ahead (½ [a] length perhaps), about the middle of the Green Bank […]. New College, however, took a better line from the Red Post to the Boat House, at which point we were exactly level. Southwell here picked up the stroke & kept it up the whole way to the finish & eventually Magdalen won a most exciting and well-fought Race by ¾ [of a] length.

But in late November 1905, Southwell sprained an ankle and so was prevented from stroking the University’s second Trial VIII; nor was he in evidence in February 1906, when Magdalen entered two VIIIs for the Torpid races. The 1st Torpid VIII, which included R.P. Stanhope at bow, J.L. Johnston at No. 5, Collier Robert [later Sir] Cudmore (1885–1941; Magdalen 1904–07; see his younger brother M.M. Cudmore) at No. 7, and A.H. Huth at stroke, started in 4th place and finished at 2nd place in the 1st Division. But the 2nd Torpid VIII, which “obtained a ‘highest possible’ [number] of bumps – 7 in all” – was described by Magdalen’s Captain of Boats as:

phenomenally successful, mainly owing to three facts: (i) That they were very well together & finished out well; (ii) That stroke absolutely refused to be bustled & rowed a slow stroke throughout which probably prevented bucketing; & (iii) Lastly but by no means least, the really excellent coxing of [Andrew Ninian] Wight [1885–1943]: he steered a practically faultless course on each night & very justly deserved the praise he got from certain experts on the Towpath.

But although Blandford-Baker includes Southwell in his list of the crew of the 1906 1st Torpid VIII (p. 295), he does not appear in the lists to be found in the Captain’s Book which must have been compiled immediately after the races in question (see pp. 438 and 448). Gatehouse, writing in the Captain’s Book, inclined to generosity when evaluating the crew of the 1st Torpid: Stanhope is “a hardworker [sic] who pulls more than his weight, with a sound back which is, however, perfectly firm”; Johnston is “the strongest worker in the crew; a Radley oarsman of experience who backs up stroke well and always rows himself out;” Robert Collier Cudmore is “at present roundbacked [sic] and short in the swing, but a good worker who has already got much longer”; and Huth is “a steady, cool stroke who, however, has not enough dash in him to make a good racer. His strokes are too slow at the beginning and too few per minute. But he gave his oar good length and only just failed to take [illegible word].” In his summary, Gatehouse concluded:

From this it may be seen that the state of the Rowing at Magdalen is prosperous in the Extreme, being Head of the River, having won the Fours, the 1st Torpid [VIII] being Second on the River and the 2nd [Torpid VIII] having made 7 bumps. It was merely a piece of bad luck that the 1st [Torpid VIII] did not catch Univ. on Tuesday as, from the Red Post in, five really hard strokes at any point would have given them their bump, but owing to the huge crowd it was impossible to acquaint them of this fact & cox’s voice was weak, too weak to be heard above the shouts up [sic] the barges.

On Saturday 7 April 1906 the Varsity Boat Race took place with only one Magdalen man in the Oxford crew – Kirby at No. 5 – but with Southwell as its Spare Man. It is, however, not possible to say whether Southwell’s absence from the rowing scene in Lent Term 1906 was still due to his damaged ankle or to the realization that he would have to do a lot of serious work in the course of that term if he wanted to pass the second part of the First Public Examination. Nevertheless, at the end of that term he justified his Tutors’ belief that he was “very clever” by being awarded a 1st in Classical Moderations, after which he seems to have been able to settle down once more to the more serious business of competitive rowing.

In the middle of April 1906, i.e. during the Trinity Term, when Southwell was perceived to be doing “little or nothing” academically, he, alongside Gatehouse, Stanhope, and Johnston began to train seriously for Eights Week, which began on 17 May 1906. The report on their performance that is preserved in the Captain’s Book reads as follows:

First Day of Eights: New College bumped Univ. before the Gut so we rowed over. [On the Second Day] New College came up on us at the start, but never in danger we rowed away from them from the Gut to the Finish. Christ Church bump[ed] Univ. [19 – 22 May]. As before[,] New College made great efforts to catch us at the Start & as we were slow getting away, they gradually came rather closer than we could have wished, but were always out of danger after the Gut [23 May]. Got away harder & New Coll[ege] hardly came up on us at all. We made a great effort & finished up quite two distances ahead of them. Remaining: Head of the River [for] the 2nd year in succession.

Although Gatehouse was subsequently mildly critical of Southwell’s continuing tendency “to cut the finish and hurry his heavy men”, he repeated the praise of the previous year almost verbatim, singling out Southwell’s “coolness” and “habitual sang froid” and ascribing Magdalen’s second victory largely to Southwell’s skill as a stroke:

Magdalen are lucky enough to have at last found another good stroke. […] To him is the credit for having kept away from University College; if he had lost his head in the slightest degree, and hurried us ever so little when they were in the quarter canvas, there was every possibility of our going to pieces. Instead[,] he kept the stroke long and enabled us to settle down. It is exceedingly satisfactory to have gone Head after having chased New College so hard for two years. The future looks hopeful as the crew was by no means composed of veterans.

On 7, 8 and 9 June 1906, Magdalen entered two pairs for the Oxford University Boat Club (OUBC) Pairs, with Southwell in one of them, and on 14, 15 and 16 June Magdalen entered two more pairs for the OUBC Sculls, with Stanhope in one of them, but neither won even though both men performed creditably.

As a result of Magdalen’s successes, the Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC) decided to enter its winning VIII for the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley Royal Regatta, and on 11 June 1906 the Magdalen crew began to practise under the expert eye of Harcourt Gilbey Gold (see G.S. Maclagan). Although their performance visibly improved as a result, on 3 July 1906 they were beaten in the first round of the Grand Challenge Cup by the Belgian Club Nautique de Gand. The Secretary noted:

In this race it is good to reflect that we probably rowed better and faster than at any other period of the summer. Our Belgian opponents were the ultimate winners, and there is little doubt that we could have reached the final had the draw been more lucky. In this race at any rate they were much too fast for us. […] Magdalen had a lead for a very few strokes; afterwards the Belgians drew away fast and were two lengths ahead at the half-mile. At the three-quarter-mile they were a length-and-a-half ahead and were said to be rowing well within themselves. Magdalen gained a little but could not make any real impression, and the Belgians won in front of a huge crowd by 1¼ length[s] in the fastest time of the Regatta, 7 m[ins].

The Magdalen crew, it should be noted, was one of the two Magdalen VIIIs that would lose four of its nine men killed in action.

As early as December 1905, i.e. the end of the Michaelmas Term in the academic year 1905/06, Christopher Cookson (1861–1948), Magdalen’s formidable Senior Dean of Arts (the equivalent of the modern Senior Tutor) from 1905 to 1919, who was well-known for his caustic tongue, for his strange idea that undergraduates were at university primarily to study, and for his intolerance of academic under-performance, remarked tersely of Southwell in the College’s academic record book: “Good scholar – hasn’t worked”. But despite Southwell’s excellent performance in the Examination Schools, his Tutors’ comments indicate that his enthusiasm for rowing was seriously distracting him from his academic work, and that when he did get round to doing any, it was rushed and not of particularly good quality. And by Trinity Term 1906, i.e. the final term of the academic year 1905/06, two of Southwell’s Tutors remarked in their reports that they had seen little or nothing of him.

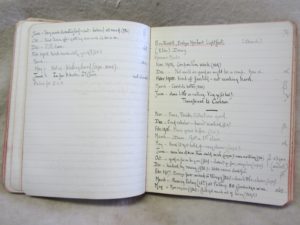

Southwell’s academic profile 1904–08, compiled by Herbert Wilson Greene et al., (Magdalen College Archive, F29/1/MS5/5: Notebook containing comments by

H.W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895-1911], pp. 73–4)

In February 1907, Magdalen entered two VIIIs in the Torpid Races for the second time. Three members of the 1st Torpid VIII were freshmen and four would be killed in action in World War One: T.B. Cave at No. 4, Duncan Mackinnon at No. 5, C.A. Gold at No. 6 and J.R. Somers-Smith, “last year’s Eton captain”, at stroke. Although Magdalen took the Headship of the River on the first day, they were bumped by Christ Church and came second at the end of the Torpids week.

Oxford won the toss at Putney on 16 March, but its crew suffered from the fact that Angus Gillan at No. 5, whom the Times correspondent called Oxford’s “strongest man”, had been weakened by influenza during the run-up to the race and was still not completely recovered on the day. Nevertheless, to use Southwell’s phrase, “he rowed with the greatest pluck”. But whilst the writer for the Times conceded that the race had been rowed in “difficult and baffling weather conditions”, he was brutally frank about the differences between the two crews: “the rowing in the Oxford boat was not at all good”, they “never rowed in unison”, “Mr Southwell, at No. 7, was not always in time with [the stroke], and the Cambridge crew were able to row with a longer stroke, being more experienced, older and physically stronger”. So although both Southwell and Kirby gained their first Blues, Cambridge, who had immediately taken the lead by rowing at 39 strokes per minute to Oxford’s 38, won by four-and-a-half lengths in 20 minutes and 26 seconds. Then, on 23 May, the third night of Eights Week in Trinity Term 1907, Magdalen were finally “rowed down” and bumped by the faster Christ Church crew – and so lost the Headship of the River even though their VIII included Stanhope at bow, Duncan Mackinnon at No. 3, Gatehouse at No. 4, Kirby at No. 6, Southwell at No. 7, and Somers-Smith at stroke. In his subsequent analysis, Southwell speculated that as a “heavy” crew, Magdalen had put too much trust in the following wind – which normally assisted them but this time let them down – and tried “too many experiments”, notably with new-style oars, about which there had been considerable discussion.

Nevertheless, for the rest of Eights Week the Magdalen VIII retained its second place with ease and went on to finish the year by winning “the Cups for all three Four-Oared Races” in the Henley Regatta – “an event which had not happened in any previous year in any club”. On 4 July the 1st VIII, which had had “the enormous advantage of the coaching of Mr Harcourt [Gilbey] Gold” and included Southwell himself, won the Stewards’ Challenge Cup against Leander by three lengths (see Duncan Mackinnon); on 5 July the 2nd VIII won the Visitors’ Challenge Cup by two-and-a-quarter lengths; and on 6 July, the 2nd VIII won the Wyfold Challenge Cup with ease, thanks to the opposing crew fouling an underwater obstacle. The pundits are also agreed that under Southwell’s and Kirby’s leadership, the academic year 1906/07 marked the beginning of Magdalen’s “First Golden Era” of rowing [recte Second, the First having lasted from 1892 to 1895] which continued until 1913. Blandford-Baker, for instance, notes that the “period from 1907 contains the most remarkable set of achievements of which the College and its Boat Club can be justly proud, covering the greatest variety of success of any of the five periods argued for” (p. 87).

When Kirby took over as Secretary of the MCBC for the academic year 1907/08, Southwell became Magdalen’s Captain of Boats, and as a result, his rowing activity increased even more. Magdalen entered three crews in the coxless Fours, with Somers-Smith at bow, Kirby at No. 3, and Southwell at stroke in the 1st crew; with Duncan Mackinnon at No. 3 in the 2nd crew; and with Gold at No. 3 in the 3rd crew. When appraising the three-week event, two weeks of which were spent in training and getting fit after the two-month-long summer break, the Secretary said that Magdalen’s rowing “showed an extraordinary improvement during the race week [end of October / beginning of November 1907 – i.e. the third week of the Michaelmas Term]. In practice we had all been stiff with the shoulders & slow in lifting from the stretcher; while even at a slow stroke we never got a long finish”. But although Magdalen went Head of the River on Wednesday 30 October 1907, the first day of the races, they were bumped off that position by Christ Church on the following day, and although they beat New College by three-and-a-half lengths on the final day of the races, Friday 1 November, they ended up in second place overall. Nevertheless, Kirby singled out two members of the 1st VIII for special praise for their performance on the first day of the races:

Southwell spurted wonderfully, and rowed, according to several unprejudiced spectators’ watches, 42 [strokes per minutes] all the way up the Barges, finally getting us home by ½ a length. Somers-Smith’s steering was perfect, while theirs was indifferent.

In the same term, on 3 December 1907, Southwell and Kirby rowed once again in the OUBC Trial VIIIs and were, together with Stanhope and two other Magdalen men who survived World War One, selected to represent Oxford on 4 April 1908 in the Varsity Boat Race. But by summer 1907, Southwell’s Tutors had begun to express considerable dissatisfaction with his irregular attendance at tutorials and below average academic performance, and towards the end of the Michaelmas Term 1907 they also began to be displeased by his increasingly wayward behaviour. This began in earnest when Southwell fell foul of the University authorities towards the end of that term, causing the rumour to do the rounds at Magdalen that the Proctors (George Chatterton Richards: 1867–1951, Fellow and Chaplain of Oriel 1897–1923, Senior Proctor 1907; and Willoughby Charles Allen: 1867–1953, Fellow of Exeter 1897–1927, Chaplain of Exeter 1898–1923, Junior Proctor 1907) had sent him down for being out of his College after hours and climbing in at 4.30 a.m. But their Black Book contains no reference to such an incident – possibly because they did not usually take such minor misdemeanours very seriously, and if, on this occasion, they did change their practice, it was probably just for the few days of term that remained. Nevertheless, in a letter of 28 December 1907, Richard Gunstone (1840–1924; known in Magdalen as “Gunner”), the legendary Steward of the College’s Junior Common Room from 1879 to 1914, who kept his ear very close to the ground where undergraduate misdeeds were concerned, wrote to Alan Campbell Don (1885–1966), a recent graduate of Magdalen with a distinguished clerical career before him:

The Term that has passed was not very eventful though we don’t often get a Demy sent down. It is late in the day to tell you about it, as it may be stale news. It was in this way, on the Saturday after the Bump Supper [7 December] there was a party in the Town and Mr Southwell & [Collier Robert] Cudmore came in over the wall [and] at 4 a.m. they went down by the Mill no doubt forgetting that Mr Webb [C.C.J. Webb: 1865–1944, Senior Proctor 1905/06] was so near [he lived in the house at Holywell Ford], and caught Southwell but the other got away and as far as I know the Dons do not know who it was Till this day.

Webb kept an extensive and detailed journal and in his entry for 9 December 1907 he described the above incident as follows:

We had been disturbed in the night by some men who came down the lane [to Holywell Ford] & (I think) came thru’ the door by the sluices, wh[ich] the servants had not bolted, & looked at the millstream in flood; smoking under our maids’ window, who were much frightened. From the bedroom window I saw them walking away up the lane; & by the time I got down and out there was no trace of them.

Despite being identified, Southwell’s unruly behaviour persisted, and after the Christmas Vacation, on 20 January 1908, it was resolved at the first meeting of Magdalen’s Tutorial Board in the Lent Term that if he “fail to give complete satisfaction to his Tutors and the Dean [i.e. Mr Cookson], his case be referred to the Officers [of the Tutorial Board – i.e. the President, the Vice-President, and the three Deans] with a view to his being deprived of his Demyship”. Accordingly, on 13 February 1908 Southwell appeared before the Officers of the Board and his misdeeds were thoroughly discussed:

The Dean of Arts reported that for about a week Mr Southwell had consistently knocked in late [and] alone upon midnight or had had visitors going out at the same time. He further reported that on the night of Saturday February 8 Mr Southwell had been reported by one of the Porters [on] duty as having come in in a state of excitement and apparent “intoxication”, and that on the night of Sunday February 9 he had been reported by the other Porter[,] Kingston[,] as having come in in a similar state. Mr Southwell admitted having drunk a good deal at Pembroke College on the Sunday, and having aggravated his condition by running home, and having therefore been somewhat affected. But he denied having been drunk on the Saturday or having been in any habit of drinking previously, and he pleaded that he had not been clearly put on Probation and asked for a further opportunity. His Tutors Mr Underhill and Mr Webb reported themselves as on the whole satisfied with his work, while thinking he might have done more. The Officers decided that[,] while thinking very seriously of Mr Southwell’s misconduct as reported to them, they did not view it as absolutely “requiring deprivation” and they therefore resolved that they would not proceed to deprive Mr Southwell [of his Demyship] but would warn him that he is [to] regard himself as distinctly “on probation” until the expiration of his Demyship, and that should he be again reported to them for misconduct or on having failed to satisfy his Tutors and the Dean[,] he would forthwith be deprived.

On 5 March 1908 the Tutorial Board considered Southwell’s position one further time, including “the representation of the Tutors in the subject” and “forbade him to row in the College Eight next term [i.e. Trinity Term 1908]”. This meant that he lost his position as Magdalen’s Captain of Boats and was replaced by his friend Kirby, with Angus Gillan (see above) acting as the Club’s Secretary. After the meeting, the President and the Dean also decided that Southwell should be gated for the rest of the Lent Term, fined £5, and given a written copy of these decisions. But the College did permit him to row as No. 3 for Oxford in the Boat Race, thereby enabling him to win his second Blue.

On 4 April 1908 Oxford lost to Cambridge for the third year running, this time by two-and-a-half lengths, after a race that was not “very interesting to watch”, partly because the Oxford VIII was suffering from three misfortunes. (i) Gillan, one of Oxford’s outstanding oarsmen, was not allowed to row because he had just got over a bad attack of influenza that had affected other members of the crew. Indeed, according to the Times reporter, “Oxford were hardly free from illness during the whole of the first half of their training.” (ii) Kirby had not completely got over an attack of jaundice by the day of the race. And (iii) the reporter identified Cambridge as “the stronger crew” because the Oxford VIII was troubled by the rough water whereas the Cambridge VIII knew how to deal with it and rowed “much more smoothly”.

Such considerations apart, Magdalen’s sanctions on Southwell had the desired effect, since after the Boat Race his name all but disappears without explanation from the Captain’s Notebook for three entire months, and during the first part of Trinity Term 1908 he lived at home in order to work without distractions. So in June 1908 he was awarded a 2nd in Literae Humaniores (Greats) – at which point it is worth noting that Southwell was the exact contemporary of Johnston who, despite his enthusiasm for rowing, never allowed his academic efforts to flag and was awarded a 1st in both Moderations and Greats. After graduation Southwell went on to row for Leander and be the spare man for an Olympic crew; he also shared the poignant distinction with Kirby and Stanhope of rowing in two of the Magdalen VIIIs that would lose four of their nine men in the war.

Professional life

After taking Finals, Southwell spent time in Berlin and at the Sorbonne in Paris and took his BA on 12 February 1910. But in May 1910 he began work as an assistant master at Shrewsbury School, Shropshire, teaching French and Classics as one of the band of brilliant young masters who had been recruited by the Reverend (Dr 1917) Cyril Argentine Alington (1872–1955; Headmaster of Shrewsbury 1908–17; Headmaster of Eton 1917–33) and a cousin of Geoffrey Hugh Alington and Gervase Winford Stovin Alington).

The Revd Dr Cyril Argentine Alington (1872-1955), Headmaster of Shrewsbury School 1908-17; Headmaster of Eton College 1917-33

(Photo courtesy of Shrewsbury School and Mike Morrogh Esq.).

Thanks to Two Men, a Memorial Book that was edited by the slightly younger Hugh Edmund Eliot Howson (1889–1933), we know a great deal about Southwell’s four years at Shrewsbury, and the abbreviated account of his life that follows derives almost entirely from that remarkable and moving source. Together with three other Eton masters – Edmund Vere Slater (1877–1933), Eric Walter Powell (1886–1933), and Charles Robert White-Thomson, an alumnus of Magdalen (1903–33) – Howson died on 17 August 1933 in a mountaineering accident on Piz Rosegg, near Pontresina, Switzerland.

Southwell began teaching at Shrewsbury on the same day that the younger and musically gifted Malcolm Graham White (24 January 1887–1 July 1916) began teaching Geography there. White, the son of John Arnold White (c.1852–1916), who lived at 24 Bidston Road, Birkenhead, and described himself as a “Merchant of American Produce”, had been a pupil at Birkenhead Preparatory School, on the Wirral, from 1894 to 1897, and at Birkenhead School itself from 1898 to 1905, where he was a member of the 1st cricket XI from 1903 to 1905 (Captain 1904/05). From 1905 to 1908 he was an undergraduate at King’s College, Cambridge, where he was awarded a lower second in 1908, having taken three Parts of the Classical Tripos in June and October 1905 (BA 1908; MA 1913). He also captained the College VIII in 1908/09, sang as a voluntary member of the Chapel Choir for four years, and did some teaching for King’s College Choir School. During his first year after graduation, he spent some time in Berlin learning German and in Rouen learning French. Moreover, although Marlborough College, Wiltshire, has no record of it and White’s name does not appear on its War Memorial, the Senior Tutor’s record book of King’s College, Cambridge, and an obituary that appeared in C.A. Macvicar’s Memorials of Old Birkonians who fell in the Great War, 1914–1918 (1920) show incontrovertibly that he taught at Marlborough from 1909 to 1910, when he began teaching at Shrewsbury.

Right from their first meeting, Southwell and White became friends and quickly developed a very close relationship with one another. Consequently, they became known as “The Men” because of their habit of addressing and referring to one another and other close Shrewsbury friends (such as Howson and the Reverend John Osborn Whitfield (1885–1965), who began teaching at Shrewsbury in 1909 and was still there in 1939) as “(the) Man/Men” – an idiosyncracy that seems with hindsight to have protected them against an emotional and physical intimacy that went beyond what was permitted by the mores of the day. Although the two friends were expert oarsmen and good musicians, Southwell was better at the former – and so was put in charge of the school’s rowing for four years, during which he coached the Shrewsbury VIII for its first appearance at Henley in 1913 – and White was better at the latter.

But Howson, writing as an anonymous “friend” in Two Men, suggests that their friendship derived not from shared interests or even from a common outlook, but from the realization that the other had tastes and interests that were new, valuable and worth acquiring. So while White “felt the debt which he owed to Southwell for literary interest”, Southwell was grateful to White “for what he had learnt of music”; and while Southwell’s preference before meeting White had been musical comedy, White introduced him to the great German classical composers – with the result that his piano playing and musical comprehension improved markedly. So it would seem that their particular friendship had a great deal to do with the complementary nature of their paradoxical personalities. Southwell was more obviously the extravert and enjoyed an easy sociability while being prone to periods of dispiritment, and Howson, who shared a house at Shrewsbury with the two friends from 1911 to 1913, had a very clear view of this side of Southwell: “Few meals passed without [Southwell] explaining exactly what he had been teaching and how, and who had done well and who badly; this soon became a source of amusement, in which he fully shared.” But Howson also understood that Southwell was a man of contrasts – and recorded:

It was typical of the amazing contrasts in his character that, immersed in a fugue of Bach, he should discover that he was overdue for the river, and after an hour’s absorption in the science of rowing, return immediately with zest to the piano.

In contrast, White, who was the more experienced teacher, was also more of a sensitive introvert, a loner who did not make new friends quickly and found it harder to adjust to new company. Nevertheless, his extravert side found a day-to-day outlet though music. So while Southwell tended to write expressive letters, White’s give less away and one has to look for his real feelings and opinions in his diary, which is very revealing; and while Southwell’s behaviour veered between wild enthusiasm and coolness when, for example, a subject embarrassed him or did not grab his attention, White found compensation for his shyness by using the vacations, which Southwell preferred to spend with his family, to face the risks and challenges of mountaineering. But according to Howson, both men shared a common characteristic – an absolute thoroughness in whatever they undertook. If a new subject or duty arose that was interesting and/or important, then there was no stopping either of them until it was completely understood. But where, for White, this would mean a kind of nervous restlessness, asking questions, and diffidence about his own powers of comprehension and execution, Southwell quietly came to grips with the facts and would never say that he understood anything until he felt he had complete mastery.

For two years from September 1911, the two friends and Howson occupied a house called Broadlands, which is situated in Field House Drive, in the suburb of Shrewsbury called Meole Brace and a mile or so south-west of the school. Howson would describe it as:

an untidy, comfortable place above the river, with a view of the twin spires and Haughmond in the distance; and there were days when you smelt the autumn mist that rose from the Severn and lay wreathed about the town and the four poplars, so that – as White said – one longed for Corot to have painted it. The ramshackle state of the house and garden, which was given over as a jungle to the cat, was a perpetual source of satisfaction to the Men. And there was the conservatory which had no flowers and the lift which sank monthly to the basement with a shattered freight of crockery, and Southwell would say, ‘We shall have to have a man about it.’”

Possibly because the house itself was never taken seriously, it was a house where many interests flourished, some fleeting, others permanent: the life of the school, metaphysics, the nature of the universe, the poetry of Racine. But above all the house was fun to live in and had something of the character of a 1960s student pad. Howson recalled:

Among later memories of [Broadlands] stands out the occasion when one member of the house became a temporary invalid through a concussion after skating, and the accent of a nurse caused so much rearrangement of rooms and furniture, and such confusion and laughter of the Men, that a misfortune was turned into a picnic; or a night at the end of a winter term, when examination papers were corrected far into the night, with intervals for biscuits and cocoa. Walter George Fletcher [1888–1915; taught at Shrewsbury from September1911 to July 1913; moved to Eton for a year; served as Second Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers with effect from 23 September 1914; and was killed in action at Bois Grenier on 20 March 1915, aged 27 (London Gazette, no. 29,151, 30 April 1915, p. 4,248)], left us at 3 a.m. and went to his house across the river shouting Meistersinger; and there were some of the party who were still found working by the dawn.

Music was central to life at Broadlands, and Howson remembers that on Saturday evenings White would play violin sonatas, while Southwell accompanied him on the piano, and that mealtimes were frequently “usurped” by Bach, Beethoven and Corelli. Sometimes, on Sunday afternoons, as many as 40 boys would come to tea and lie about the floor, reading or listening to chamber music. Ivor Atkins (later Sir; 1869–1953), who was Organist and Choirmaster at Worcester Cathedral from 1897 to 1950 and knew Southwell’s family well, paid him the following tribute for engaging in such activities:

He must have shown a missioner’s zeal in making good music known to the boys of Shrewsbury School, for he brought me glowing accounts […] of the success which came to those who co-operated with him in the work of introducing chamber music to them. The steady growth in attendance of the boys at these little music-meetings was a joy to him, and the fact that the best music easily won a way to their hearts was to him a sufficient reward.

During the vacations, when he was living in his parents’ house in Worcester, Southwell devoted a lot of time to reading and studying music, and Atkins continued:

His enthusiasm for music, and, perhaps, especially his measureless admiration for Bach, made him very attractive to me, and this attractiveness was only heightened by his quietness and modesty. He was at the time studying the piano, in which I was able to give him some help, and it was a great delight to me to watch him working at the forty-eight preludes and fugues. Though his playing was wanting on the technical side, he more than made up for it by his insight and sense of interpretation; and in discussing them with me I was very early struck by his knowledge, and by the clearness of his musical faculties. It was his habit to find his way to the organ-loft at Worcester soon after his arrival in vacation time, and I found increasing pleasure from his visits. His coming was always the occasion for some of the greatest of Bach’s organ works to be drawn upon, and though, as I have said, he had a considerable knowledge of Bach, he had had few opportunities up to this time, I should imagine, of hearing the later organ works. This was especially true of the Choral Preludes. His joy in a great work was splendid, and I shall never forget his reception of the Fuga Sopra Magnificat. He shared with another, whose ties to the Cathedral were similar to his own and who has made the great sacrifice, a power of appreciation which was nothing less than an inspiration to others.”

As teachers, both men rapidly gained the affection and respect of the boys. Howson tells us that White “could teach sitting among the boys or standing on the widow-sill and swinging from a cord” and that Southwell was “unique as a teacher”, whose

own accounts of his work were so self-deprecatory, and often so comic, that we never really knew what went on; but no boy who had been in his form ever forgot it. He probably spoke more freely and naturally to his form even than to his friends. He read poetry to them, which few can do with success […]. It was this that indirectly inspired the poems which were written for him every week, some of which were eventually published under the title of V.b when he was serving in France. Few of those who have read the book will deny that it is a remarkable result; for the poems were written by average boys of sixteen, and [Southwell’s] detailed criticism was small; they were the direct outcome of his enthusiasm. […] Of the spirit of the form his own pupils alone can adequately speak; the fourth Eclogue [written by Virgil in c.42 BC, it deals with the birth of a boy child who would be the saviour of the world] is still remembered by the gestures with which he declaimed it; for he would read it to his form whenever Christmas drew near with the enthusiasm of a religious rite; and when one of his boys was asked about the form, he said: “Mr. Southwell walks round the room reading Homer to us with tears in his eyes.”

Similarly, after his death in action, another former pupil wrote in a letter to Southwell’s father:

Unfortunately I was never in his form, but he took me for a term in French, and I can only say that those French hours were the most delightful hours I have ever spent in study. I liked them to such an extent that I often used to count the number of hours until the next one. I fear I am not a lover of books, and it was simply the personality of your son which made those hours so delightful. I don’t think I have ever got to like a master in such a short time as when I began to know your son. I think his poems were very characteristic of him, and the book he arranged, V.b, is one of the gems of my bookcase.

Once Southwell had left Shrewsbury to join the Army, his friend Ronald Arbuthnot Knox (1888–1957), one of the most brilliant classicists of his generation (see G.M.R. Turbutt and L.W. Hunter), succeeded him as form-master of V.b for five terms in 1915 and 1916, i.e. at the time when Knox was gradually converting to Roman Catholicism. When describing his spiritual journey in two privately printed books – Apologia (1917) and A Spiritual Aeneid: Being an Account of a Journey to the Catholic Faith (1918) – Knox recalled his experiences at Shrewsbury as follows:

Of the junior masters at Shrewsbury […] I can honestly say that I never came in contact in all my life with a group of minds so original. Mr. Southwell and Mr. White, who both left just before I came and have both since been killed at the front, left behind them a language and a tradition full of the strangest eccentricities and of the most penetrating humour. (p. 213)

From left to right: the Revd William Smith Ingrams (1853–1939), Assistant Master at Shrewsbury School (1883–1932, at least); Hugh Edward Eliot Howson (1889–1933); Philip Bainbrigge (1890–1918; killed in action while serving as Second Lieutenant in the 5th Battalion, The Lancashire Fusiliers, on 18 September 1918); Ronald Arbuthnot Knox (1888–1957); photo taken at Shrewsbury School during the winter of 1915/16) (Photo courtesy of Shrewsbury School and Mike Morrogh, Esq.)

Southwell and White were avid and eclectic readers and Howson tells us that:

when once an author, were he Shakespeare or Jerome K. Jerome, was admitted a classic of the house, quotations from him were permanent. Southwell’s shelves in particular comprised a strange medley, [with Swinburne’s verse drama] Atalanta in Calydon [1865] living neighbour to a volume on the golf courses of the British Isles. But there were favourites in common to both: Richard III, Orthodoxy, The Four Men, Ronsard’s poems, The Pickwick Papers (on which Southwell was almost infallible), the Song of Taliesin from the Mabinogion [a selection of texts in Middle Welsh that were collected in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries], The Babe B. A. [by E.F. Benson (1896)], Salt-Water Ballads [by John Masefield [1902]), and [A.E. Housman’s] A Shropshire Lad [May 1896]; Lamb’s Essays [Charles Lamb, Essays of Elia (1823); The Last Essays of Elia (1833)] were equally dear to White, and Southwell read The Pirate every Christmas. Perhaps the most quoted and best loved book of all was [Hilaire Belloc’s] The Path to Rome [1902; which Southwell mentions with great enthusiasm in his letters from the Front to H.E. Walker (b. c.1887), an assistant master at Shrewsbury, of 4 August 1916, and to Howson of 8 August 1916]. Charles Amieson Blake [a character in a scenario in The Path to Rome] was an accepted member of the household, as was Michael Finsbury [the attorney in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Wrong Box (1889)]. Of the classics, Virgil was the special favourite.

Both men spoke strongly to approve or disapprove of books “with feats of exaggeration that were humorous, but never intolerant”. For all that, Howson continued:

Southwell, who had an infinite patience with tiresome conversationalists and was generous to a fault, could be impatient with a tiresome author. He forgave men more readily than books; yet even in his literary antipathies he never lost balance; whatever is meant by the “Artistic Temperament”, creative or critical, it shone clear in him; so clear, indeed, that his obvious sanity over all things vital and human was the more remarkable. Though his preference was for imaginative writing, he showed remarkable grip of an argument, for all his pretence that he could not follow the plot of [Robert Louis Stevenson’s] Kidnapped [1886 …]. Once fascinated by an author, he was only content when he had searched for his innermost meaning and thrown light on every obscurity.

But, Howson continues, in contrast to White who was interested in problems of the day and fond of pictures, Southwell

was seldom heard to talk of politics, and – strangely enough – with few exceptions, such as the “Mona Lisa”, pictures had little interest for him; characteristically he devoted his time almost exclusively to other forms of art which appealed to him more. White said of him, that had he not been a schoolmaster, he would have been known as a critic; and it is probably true.

In May 1913, the denizens of Broadlands moved to the larger New House, a hostel for bachelor masters which had been recently built nearer to the boys’ boarding houses and which, as the School’s Medical Centre in Ashton Road and near its main gates, still commands a wide view over to Wenlock and the Stretton hills. Howson records:

It was something of a tragedy to leave Broadlands and all that “human disorder and organic comfort which makes a man’s house like a bear’s fur for him”, but it was a change to civilisation, and we became respectable householders.

Howson records that their two years in the New House slipped happily by:

there was the work of school hours every day, of living interest to both, and in the evening we would “sit round” (to use Southwell’s phrase) and (with Southwell himself often asleep in a chair) discuss books, theories, or the day’s events; or there would be boys to tea, and one would look into Southwell’s room and find a silent ring engrossed in books before a winter fire. […] On November 5, White annually let off five fireworks in the garden dressed in a scholastic gown and broad brimmed felt hat, […] and there was a lazy summer afternoon when Southwell in a fit of boredom suddenly announced “A ride in a cab is required”; and within the hour we were wandering sleepily round Shropshire lanes in an open Victoria, whose driver had orders to stop at every bridge, where he received a cigarette while we watched the stream under the willows; and so home, when Southwell fled to the river to coach the Henley VIII, or played the 17th Fugue of Bach, which he called “The Foundations of the Earth”. Meals were necessarily spasmodic, and White would heighten their irregularity by presenting arms from “The Port”, or giving a detailed rendering of the Eroica Symphony, or imitating a puma in its cage at the zoo. On winter evenings we would find exercise by running in the dark; and on Thursday mornings, having no early school, Southwell practised this alone before breakfast, recalling the days of Putney. And on summer afternoons there was cricket to watch, or we sat in the garden by the half-grown privet hedge; “and if it doesn’t grow quickly” Southwell would say, “we shall be overlooked by a long necked man in a straw hat”. Expeditions were frequent; sometimes “up river”; sometimes (in winter) to the town, from which Southwell would return with twenty collar studs and an early edition of Ossian [The Works of Ossian (published 1760–65) were a cycle of epic poems, allegedly written in the original Gaelic and collected by the Scottish poet James Macpherson (1736–96), but actually written by Macpherson himself]; sometimes, too, farther afield, often in company with boys, to the Briedden hills or Ludlow or Church Stretton, to climb Caradoc. Southwell often went by himself on the spur of the moment, and visited the Long Mynd or lost himself on the uplands of Clun Forest. Or White would be taken in George Fletcher’s side car, and together they would scramble on the rocks of the Stiperstones. To both Southwell and White the procession of the seasons was a pageant; the winter term was always the most welcome, but all times of the year had their glamour and mystery. They appreciated the fireside and the hillside alike, the “Friendly Town” and the “Open Road” [two books of poetry by the English writer Edward Verrall Lucas (1868–1938), both published in 1905], November winds and days of heat in the summer when it was almost too hot to row; and all with an affection that was far stronger than mere liking.

Howson concluded:

Unreal enthusiasm and bad taste made them unhappy, and they coined a new word, “spinal”, for the feeling, yet their sense of humour invariably prevailed, and left them generous and kindly. They were readily adaptable to new places and surroundings, though the power of self-adaptation came to White by effort and to Southwell by nature; but there was no circle which after a month did not receive both with open arms. White felt himself a stranger for a time at Shrewsbury; he was drawn by so many incentives, and was the slave of so many visions, that the settled habit of surrender to its atmosphere came slowly, and he was beset with doubts as to his ultimate work. These uncertainties gradually faded, and – by the time that he left – the place and its life lay close to the centre of his affections; he felt happy in his work, and one of his colleagues dared call him “the ideal schoolmaster”. It was high praise, but at least shows that White was not far from finding his life’s work. Southwell, with equal humility, was yet fond of Shrewsbury from the day of his arrival, and his happiness was infectious. Throughout, it was the one real pivot of his interests. Religion was to both a thing of wonder, not to be directed in direct speech, defying analysis, but vital. Life remained to them a mysterious web, shot with tears and folly and that laughter which marks a “gross cousinship with the most high, and feeds a spring of merriment in the soul of a sane man” (Belloc, The Path to Rome). Their humour was of that rich sort, which does not paraphrase itself, but confidently assumes its equivalent in others; yet it was never cynical, and never far removed from sympathy.

War service

Malcolm Graham White and Evelyn Herbert Southwell (October 1914–July 1915)

White was commissioned Second Lieutenant in Shrewsbury’s Junior Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) on 6 August 1910 (London Gazette, no. 28,404, 5 August 1910, p. 5,675) and promoted Lieutenant on 1 July 1911 (LG, no. 28,521, 11 August 1911, p. 5,992). As such, he became involved in the war effort almost immediately after its outbreak, and from September to early October 1914, when he was required back at school, he helped train a battalion of recruits for the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry at Blackdown. On 13 February 1915 he was promoted Temporary Captain in Shrewsbury’s Junior OTC – which meant that he was given responsibility for a Company (LG, no. 29,093, 5 March 1915, p. 2,360). In contrast, Southwell was less keen on things military and was not commissioned Second Lieutenant in the School’s OTC until 1914. According to Howson, he found “ceaseless amusement” at the thought of himself in this new part, and was forever drawing ludicrous pictures of the character of the “practical man” and pretending that military science was beyond his grasp.

Left: Evelyn Herbert Lightfoot Southwell, BA (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford). Right: Malcolm Graham White, BA (Photo courtesy of Birkenhead School, The Wirral)Towards the end of Michaelmas Term 1914 Southwell strained himself so badly while on a field day that an operation was necessary, and then, during Lent Term 1915, the friends’ last at Shrewsbury, news arrived that Walter George Fletcher had been picked off by a sniper on 20 March while serving with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. According to Gavin Roynon and Tim Card, Fletcher, who had returned to teach at Eton for a year after teaching at Shrewsbury from 1911 to1913, was one of three members of Eton’s Modern Languages staff, all OTC officers, who had been called up by the War Office on the outbreak of war because of the shortage of interpreters and liaison officers. The other two were Charles Andrew Gladstone (1888–1968), the grandson of the Prime Minister and, from 1967, the 6th Baronet, and Eric Walter Powell, an artist and Olympic oarsman (1908) who survived the war only to die in the mountaineering accident of 17 August 1933 mentioned above. Howson cites part of a letter that Fletcher had written from the Front shortly before his death:

I have now had dinner – Irish Stew, Beer, Sardines on Toast, Marmalade. Also the sun is streaming in with some real warmth and I am feeling hearty. I will therefore make some general remarks on the subject of the War. There may be some excitement in it, but that takes the form of fearful strain on the nerves without any of the exhilaration one usually associates with danger. Perhaps a day attack can be exhilarating: in fact the only time I have been pleasurably excited was when the enemy attacked us by day and we knocked them down. Our attack is yet to come. The fact remains that war is a bore and we are all fed up with it. Death: one becomes a fatalist on this subject and looks forward to the prospect of extinction: “That moving Finger writes, and having writ, Moves on……” [lines from Omar Khayyám, The Rubaiyat, trans. by Edward Fitzgerald (1809–53), 1859]. Fear and Courage: I think it was a man called Socrates who said that Courage was a right knowledge of such things as are to be feared: and to a considerable extent, he was right. When you know how little damage a high explosive shell does to you compared with the noise it makes, you don’t fear him so much. But Socrates is only partly right. I know what a fool a shell is and what a fool a bullet is, and yet I am terrified of both. But a more insinuating and demoralising fear which seizes a man is an entirely illogical unreasoning fear of the enemy as such; imagining him to possess superhuman qualities when he knows he is very human. Hence the great thing is, and will be, to make men realize that the enemy is much more afraid of you than you are of him. Hate: is non-existent – at all events on our side, I think on the enemy’s too. He too is capable of being jovial in his enmity towards us, and will signal misses or bull’s-eyes when we plug his loop-holes. Atrocities: I haven’t seen any. All first-hand evidence – even that gained on the retreat – goes to prove that the German soldier as a whole is capable of gentlemanly and chivalrous behaviour, and of this he has given numerous examples. The Future: in front of us there is a ridge on which we can see three rows of trenches, barbed, barricaded and cunningly dug. These we will have to deal with after his first line. They probably have several hundred of these behind those we see. In October [probably 1914, on the Messines Ridge (see V. Fleming)] the Germans, with unheard of courage, determination, and force, tried to break through a single line of ours and failed – Well what abaht it?

Fletcher concluded the letter by exhorting the two friends to join up, and Southwell later said that it was Fletcher’s death as much as anything that had made him take this step, a view that is substantiated by Southwell’s letter to his father of March 1915 in which he writes that he now feels obliged to take Fletcher’s place. White expressed his feelings in a letter of 26 March 1915 to George Fletcher’s father, the Imperialist historian C.R.L. Fletcher (1857–1934; Tutor in History at Magdalen 1885–1906, Fellow 1889–1906; Classics and History Teacher at Eton September 1914–Easter 1915 and January to Easter 1919):

The news which you sent us on Wednesday was to me the most terrible blow the War has sent me. George was absolutely the most splendid character I know; such a perfect honesty and directness in conversation, such a fresh and genuine temperament, made him the companion one would have chosen for any circumstances. I am telling you things you already know, but I can’t help trying to put him into words, in every sense of his loss and our great sorrow. It was a great day in our life here when he joined us at the New House. That was my happiest term here. His personality lies stamped on all the little institutions of our life, and his name is mentioned almost every time we sit down together. He was, and is our d’Artagnan. As I say that, it strikes me what a long way that comparison will go. […] I hope I may catch some of his spirit and show one hundredth part of his courage.

Second Lieutenant Evelyn Herbert Southwell, BA; photo probably taken on Salisbury Plain in mid-May 1915

(Photo courtesy of Shrewsbury School and Mike Morrogh, Esq.)

So by the end of April 1915, both White and Southwell had either applied or decided to apply for regular commissions, and had left Shrewsbury, leaving a gap “that was felt by masters and boys alike”. Lack of room prevented them from joining the same battalion, and although White had to wait a while before a posting was confirmed on 7 May 1915, Southwell was gazetted Temporary Second Lieutenant in the 13th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (London Gazette, no. 29,156, 7 May 1915, p. 4,419) – which he joined on 24 April 1915 at Perham Down, on the edge of Salisbury Plain, some six miles north-west of Andover. A memorable week of Brigade training ensued (10–15 May), and then, for more than two months, during which he and White visited Shrewsbury together for one weekend (10–12 July), Southwell worked at Windmill Hill Camp, near Ludgershall. Although his letters expressed regret that his civilian life and profession were receding and a slight shame at the Army’s success in narrowing down his life to that of a healthy animal, with “the importance attached to one’s food or bivouacs after a long march” being “rather scandalous”, he was very happy in his work. Indeed, one of his former pupils, who was himself later commissioned in the Rifle Brigade, said in a letter:

I suppose we can’t drag Mr. Southwell away from his military duties, which he seems to love. I can just see him stretching out his arm quite straight and stiff, palm of the hand turned upwards, fingers pointing up, so as to make a cup of his hand, saying “It’s that, it’s that. Very fine man”; or when some unhappy private drops his rifle, “Oh, not a good man. You stand there with a face like a plate of whoggy porridge, like some great owl.”

Southwell kept a diary, and while he admitted there that Army life was tough, machinelike even, he waxed lyrical about his experiences amidst the quintessential English countryside during the Brigade training week of May, which he called “one of the happiest I have ever known”. During that exercise, Southwell’s Company was based for a while in the Wiltshire village of Wilcot, just west of Pewsey, and for a time he was billeted at the vicarage there, where the Vicar and his wife received him and the other subalterns of his Company with great kindness:

The morning was naturally blank, but I shall not easily forget the sudden transition from the long march to the garden behind the Vicarage, where we lay about under the hedge and looked sleepily over the long, low water-meadows, and watched the consoling English mist wrapping itself round the English trees. No soldiering ever troubled the serenity of the landscape, nor the old church tower [of Holy Cross Church] behind; for the whole of that valley has just accepted very quietly the memory of the men who died for it in year after year before we ever saw it, and every one, I felt, was another perfectly present, and therefore entirely hidden and unsuspected, guarantee of that incredible peace. It was during this evening that I walked part of the way with Leggatt towards his billets at Sharcott, and so back over the fields: and it was there that I went with opening eyes down an English lane […]. But it is not of these happenings that I want to write, only my pen is so cursedly obstinate. It is of those few memories that I want reminding – The Savernake wood country at dawn, the stars over the night march, the water of the Avon, the church by the canal, the five minutes in the lane, the dear Vicar and our return to his home, the bugles as we entered Pewsey from Wilcot on the last morning, the morning in the “Ebenezer” school, – Wilcot above all, above all Wilcot: those are the things which make the Wonderful Week, and which in any future inconveniences (such as I might be excused for expecting) I hope and pray for courage to remember.

Southwell, it seems, had found a highly-charged, semi-religious vision of England that expressed what he thought he would be fighting for and he linked it with the poetry of John Masefield and, inevitably, A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad. On 27 May, while at Sidbury Camp, Southwell underwent another, similarly epiphanic experience and noted that this moment of peace was what he had been seeking for weeks.

Evelyn Herbert Southwell (July–August 1915)

On 29 July 1915, Southwell’s Battalion left for France as part of 111th Brigade, in the 37th Division, and landed at Boulogne two days later. But as Southwell had trained for less time than the other officers in his Battalion, he was left behind as OC (Officer Commanding) Details, and on 16 August he was transferred to the 15th (Training and Reserve) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade at Belhus Park, Purfleet, Essex. Here, on 19 August, he was overcome by an attack of intense nostalgia that seems, judging by the German insertion, to have been fed by Rupert Brooke’s poem ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’ (written in Berlin in May 1912 and first published in 1914 and Other Poems in May 1915). Southwell transcribed the experience in his diary as follows:

As usual, I have left a large – lieber Gott, How large! – part of myself behind on [Salisbury] Plain. Time is probably short; and that is why I have not the time to linger and dream over that adorable country. But I will give myself just five minutes very occasionally; and those will be the times when I will remember the two home signals of the tree clumps on Windmill Hill: and the finest and first and most alive Downs-Road in all the world which leads from its foot; and the very British Village to which that dear road flies; and the very Roman Guard that is kept at the top of Sidbury; and the little church spire of Chute, little known and never visited, though there was that supper in the house of the old lady, of Wiltshire, one night very late in my stay; and the night of bivouac at Fenner’s Firs; and Wilcot – but I should be a fool to trespass on that sacred ground; and Ludgershall Church and village, and my first billet there; and Salisbury Close, peaceful beyond all bearing; and Church Parade under Our Hill; and for love of that country I will even include Bulford Ranges (though I cannot go so far as Perham Down, its huts and its trenches); and the most glorious College of Marlborough must find a memory; and the Andover Road, which found me so strong (!) amidst the “fall-outs”, though so powerless to help them; and the slopes that used to call me, day after day, I well knew where, I well know where; and my own, my very own Details, whom I see, thank God, with a wistful and most worshipping affection day by day, the remnants of the 13th, ah yes! the 13th R[ifle] B[rigade] in a very strange land.

Malcolm Graham White (May–July 1915)

Malcolm Graham White, BA, in the uniform of an officer of the Rifle Brigade c.June 1915 (note the hat badge and the Sam Browne belt); the man behind him is probably H.E.E. Howson (see above)

(Photo courtesy of Shrewsbury School and Mike Morrogh, Esq.)

Meanwhile White, who had been made a Lieutenant in the 6th (Special Reserve) Battalion of the Rifle Brigade on 31 May 1915 (London Gazette, no. 29,224, 9 July 1915, p. 6,708), joined his new unit in Sheerness, the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, to take command of a company of convalescents. He found it more difficult than Southwell to adapt to Army life or to take pleasure in the immediate, and on 21 July he noted in his diary that he had just had “an hour’s loneliness and depression” and how different he felt from “the Tommies under me”, not least because of his visceral reaction to the poetry of Housman and Browning, and how he wished that he had “someone” there with whom he could talk about “everything”. Four days later, on 25 July, he wrote to Howson, who was still at Shrewsbury:

Oh Man, I wonder too if you know how I felt, when you saw me off a fortnight ago, and you and the blue hills and Shrewsbury were drawn swiftly away and then finally blotted out by the Wrekin. (“I never liked that Wrekin” mightn’t your nurse have said? – and I like him now less for his insolence and relentlessness that evening.) I was somewhat comforted by the dinner at which I was your grateful guest, but I was horribly conscious of the increasing absence of the host. I am rather dismal about the end of term. Isn’t that odd? But I feel that Men (and boys) are there and that the place is solid, and exists for me to picture at any moment I like. The end of term causes it to lose something of its existence for me. I’ve had a wonderful letter from the Man [i.e. Southwell] to-day. I wish we were together – it is really a tragedy as I miss him so very much. He is lonely, and so am I very often.

This is a significant letter because the jokiness, literariness and third-person distanciation that mark so many of the letters that passed between the three men has given way to an unashamed sense of sadness and loss. Here, for the first time in the Memorial Book, the reader begins to feel that the relationship that existed between White and Southwell, and possibly Howson, too, went well beyond the comradely or intellectual-aesthetic.

Evelyn Herbert Southwell and Malcolm Graham White (September 1915)

By mid-September 1915, with the Battle of Loos looming, the focus of both men was turning towards France. But first, on 19 September, what turned out to be the farewell reunion of the Broadlands household took place for a few hours at Purfleet, and on 20 September Southwell moved to South Camp, Seaford, in Sussex. Two days later he wrote a characteristically enthusiastic letter to his erstwhile Headmaster, the Reverend Cyril Alington, expressing satisfaction at the quality of the huts and food there, at the proximity of the sea and a town, and at the availability of the Downs for walking after the claustrophobia of the Purfleet mud-flats. On 24 September, White told Howson in a letter that while two of his “real friends” at Sheerness – probably Jocelyn Murray Victor Buxton (1896–1916; killed in action on 1 July 1916 while serving as a Second Lieutenant with the 6th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade; no known grave) and Hugh Francis Russell-Smith (1887–1916; died of wounds received in action in Rouen on 5 July 1916 while serving as a Captain in the 1st Battalion of the Rifle Brigade) – both Cambridge graduates – had been listed for front-line duties, the Colonel needed him to stay at Sheerness for the present because of the current shortage of senior officers. He concluded: “I never pretend that I want the trenches; but one part of myself says to the other part – ‘This war is an ordeal which I dare you to face; I don’t believe you can’, and the other part replies – ‘Lord, then I suppose I must try’.” But finally, on 30 September, with the Battle of Loos now over, Southwell, who was on leave in Worcester with his parents, was ordered to the Front and left on 1 October, meeting White on the way in London.

Evelyn Herbert Southwell (October 1915–June 1916):

According to Southwell’s medal card, he landed at Le Havre on 20 October 1915, but this must be a transcription error for 2 October since it was on this day that he wrote a farewell letter to his mother while he was on the train to France. Moreover, the War Diary of the 9th (Service) Battalion, the Rifle Brigade (42nd Brigade, 14th (Light) Division), in which Eric King Parsons and Herbert Westlake Garton – still away sick because of his wound – were still serving, confirms that Southwell reported for duty on 3 October. At that time, the 9th Battalion was in Reserve in the relatively quiet Ypres Sector and on 12 October, before his first taste of the horrors of a war of attrition, Southwell penned three naively enthusiastic letters about life at the Front. The first was to the Reverend John Osborn Whitfield (see above):

The inconceivable prospect of a wooden-lined dug-out, in reserve, with the yellow leaves and the October term, and nothing but the shells, still bullying the battered remains of the city a couple of hundred yards away, to remind one of realities – this was indeed a change. We weren’t idle: six hours digging per day keeps one fit all right. But this sort of digging is not like making a new trench at fifty yards, and there is time (when the three aeroplane whistles go, and work and staring upwards are forbidden) to look over one’s shoulder and watch the crumbled houses and ruined towers. “Hate the business?” Why, there is not a blade of grass or a broken brick which does not remind one that no one ever had such a time in his life as this of mine, nor ever will again! Oh yes, I am in a colossally good temper. But then I have had nothing to go through yet, like those others.

The second was to his sister:

I was pretty sleepy last night, and I slept without a break for eleven hours, but in camp. Oh! but the dawn over Flanders, and the booming of a big bombardment farther away, in a different direction, and the glorious sort of war-wind with just the right amount of suggested pestilence in it that blew over the fields as the sun rose, and reminded one that one was in a big show; and right below one the wood, huge on the map, ten short stumps on the field; and the city of Ypres with not a house standing entire; and the terribly sad view of glorious churches, battered to blazes, seen as the mist cleared in the morning, weeping to break one’s heart across the desolate plain. Oh! if I could always be as happy as I was during that trial trip, I should not have much to complain of! And the men were so glorious. They’d been in the trenches continuously for many, many days, begrimed from head to foot, their eyes heavy with want of sleep, and their whole appearance quite different from that of men who’ve not been up. It was a very, very young Corporal, and there was a deuce of a bombardment going on, and the Sergeant-Major met him: “What are you doing?” “Oh! just issuing rations, Sergt.-Maj.” That is not particularly remarkable, no doubt, and that is why it is worth quoting, as being so frightfully typical. Well, there wasn’t any risk as far as I was concerned, and it was only when we got back that somebody said, “By Gad, we’ve been under fire; what fun!”

The third was to Whitfield’s mother:

We had a glorious time there; we were heavily shelled, coupled with almost complete safety; and what more interesting experience could you wish? Safety, because our front line was too close to theirs to be aimed at, but our support trenches (and in fact the back of my dug-out, only – by fragments – occasionally, in the front line) got hit. Yet only one casualty, as their shells mostly fell between us and them. It went on for two hours and was called “fairly intense”, i.e. nothing like that before an attack. Digging a new trench at sixty yards from the Bosches [sic] under flares and (bad) rifle shots was less of an arm-chair show, rather! I would like you to think that my thirty-six hours there are a good omen, for they were absolutely the best I ever knew. I loved everything; at every step, even in the “horrible mire and clay”, I seemed so much the more admitted right into the Great Show. But I am getting foolish and must stop. It is because I am very, very happy.

Finally, when Southwell wrote to Alington on 26 October, he described the period that ended with the uneventful week in the “reserve dug-outs outside the ruined city” as: “The most priceless ten days in my life, I think.”

On the following day, the Battalion moved up to the trenches at Potijze, a north-eastern suburb of Ypres, an experience that Southwell could still enjoy despite its discomforts, and on 21 October, the day after it had ended its stay there, the Battalion entrained for Poperinghe, around six miles due west of Ypres. It then marched to billets at Houtkerque, a further five miles to the west-south-west and just over the border in France, where it stayed in Reserve for four weeks, resting and training. On 14 November 1915, Southwell wrote a letter to Ronald Knox in which he described his recent experiences at Houtkerque in greater detail and with more frankness:

The time here has really been more like training in England than anything else: we run, slowly and ponderously after my manner, before breakfast, then parade with smoke-helmets, inspect men for absurd deficiencies, shoot a little, drill, do musketry, digging, wiring, make speeches (very rarely; I’ve made two on “trench duties” to the Company on wet days, mainly because I swore when in the trenches that I would get about thirty points really hammered into them in a lump, instead of having to strafe a man here and there in each of the twenty-two bays); and so forth. Even football has found its way in; and our Coy. is as pleased as any school ever was over coming top in that. It is all very different from the trenches; sleeping in a bed seems absurd luxury, especially a bed like mine; one hopes this period will not convert us all into soft jellies again. However, no doubt things will seem more straight-forward when we do go in, as one can’t help picking up a little sense in even so short a visit as our last.

Then, on 18 November, the Battalion marched back to the trenches in Potijze, half in the Canal bank and half in the Kaaie Salient, and alternated in these positions with the 9th (Service) Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps – with which it would be brigaded in 42nd Brigade during the Battle of the Somme – until the end of the month. Unfortunately, the weather became so bad that on 20 November 1915, during a spell in the trenches in Potijze Wood, Southwell developed a severe chill and a high temperature and, much to his disgust, had to be hospitalized in No. 12 Casualty Clearing Station at Hazebrouck until 8 December. He recorded in a letter that “the authorities were very generous […]; we were excellently fed, and night after night there would be red and white wine, whisky and brandy on the table”. Nevertheless, when he was first allowed to get up and walk about he discovered that the illness had left him very weak, and during his absence from the Battalion, his batman, “an awfully nice youth,” was killed by a whizz-bang. On 11 December 1915, shortly after his return to the battalion, Southwell wrote to Mrs Whitfield concerning his hospital experiences:

I was very angry at this, being a little ashamed of going under to a very unmilitary kind of complaint like that. So I said to myself, “I will not advertise this episode”. Well, naturally there was no news from such a place, though when I got out of bed it was interesting to meet other convalescent officers and exchange talk, about where various Divisions and Battalions were, and so forth. The trenches are in a very dreadful state, frightfully wet, knee-deep in very many places, unusable in others (a trench is regarded with disfavour when it gets more than “thigh-waders-depth”!), and falling in all over the place; but the men are wonderful. They are, I repeat it with the most sincere reverence (there is no other word) – Wonderful. They have a dreadful time, especially in soaked dug-outs at night – where officers generally get at least fairly dry ones and do get more chance of a sleep, and no touch of drama comes along just now: they just stick it. I adore them; they are the people.

On the night of 5 January 1916 Southwell had a narrow escape while wiring in front of the line – a mere 15 yards away from the Germans. A machine-gun had already opened up on wiring parties several times without causing any casualties. But Southwell’s Company Commander, Captain John Alwarth Merewether (1882–1916; killed in action on 15 September 1916 at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette; no known grave), heard the breach of a machine-gun click as it was being loaded and got Southwell and his detail back into their trench just as the flare went up and the German machine-gunners opened fire.