Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born: 1 February 1886

Died: 28 November 1917

Regiment: Lothian and Border Horse attached to Machine Gun Corps

Grave/Memorial: Cambrai Memorial, Louverval: Panel 1

Family background

b. 1 February 1886 at 55, Cadogan Place, London SW1, as the youngest son (of five children) of the Right Honourable Sir Francis Hyde Villiers, PC, CB, GCMG, GCVO (1852–1925) and Lady Virginia Katherine Villiers (née Smith) (1853–1937). At the time of the 1891 Census, the family was living at 103, Sloane Street, London SW1 (eight servants); they were at the same address at the time of the 1901 Census (seven servants); at the time of the 1911 Census the family was probably living in Portugal.

Parents and antecedents

Villiers came from an eminent family of diplomats and Liberal politicians. His paternal grandfather, George William Villiers, the 4th Earl of Clarendon (1800–79), distinguished himself over a period of 50 years in highly testing and difficult political situations. He served as a diplomat in Russia (1820–23); as British Minister at the Spanish Court (1833–39), where, during a period of civil strife, he supported the Spanish Liberals against those who stood for a Catholic absolutism; as Lord Privy Seal (1840–47), in which capacity he advocated close and cordial relations with France; as the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1847–52), i.e. during most of the Great Famine (1845–52), when one million people died of starvation and another million emigrated; as Foreign Secretary (1853–59), a period that spanned the years of the Crimean War (1853–56), when, once again, he cultivated the closest possible relations with the French in order to counter the Russian threat more effectively; as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1864–65); and, finally, as Foreign Secretary for a second term (1865–70).

Villiers’s father was the eighth and youngest child (fourth son) of the 4th Earl and entered the Foreign Office in 1870, where he had a remarkable career, acting almost continuously as Private Secretary to successive Under-Secretaries and Secretaries of State until he himself was appointed Acting Second Secretary in the Diplomatic Service in 1885. He then served as Private Secretary to the Earl of Rosebery (in 1886, 1892–94) and Acting Private Secretary to the Marquess of Salisbury (1887). From 1896 to 1906 he was Assistant Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs; from 1905 to 1911 he was Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Portugal; and from 1911 to 1919 he was British Minister Plenipotentiary to Belgium (and the first British Ambassador there from 1919 to 1920). When the Germans invaded Belgium, he accompanied the country’s young King Albert into exile; he shared the hardships and dangers of the defence and evacuation of Antwerp in 1914; and throughout the war he accompanied the Belgian Government in its new seat at Le Havre. When the Germans were pushed out of Belgium, he witnessed King Albert’s triumphant return. An obituarist remarked that “throughout that trying period he displayed great steadfastness and courage, as well as those qualities of tact and judgment which belonged to his profession”. He became a Privy Councillor in 1919 and received honours from Belgium and Portugal.

Villiers’s mother was the eighth child (youngest daughter) of the banker Eric Carrington Smith (1828–1906), a partner by 1877 in the private bank that had begun its life in Kingston-upon-Hull in 1784 as Abel Smith Sons & Co. and, from 1828, was known as Samuel Smith Brothers & Co. Its principal partner, Abel Smith (1717–88), was the son of a wealthy Nottingham banker who had been sent to Hull in 1732, and by the end of the eighteenth century it had become one of the biggest British banks. In 1902, Samuel Smith Brothers & Co., together with the other quasi-autonomous Smith banks around England, merged with Union Bank of London Ltd to form the Union of London & Smiths Bank Ltd. Abel Smith became related by marriage to the Wilberforce family, also from Kingston-upon-Hull, and was the uncle of William Wilberforce (1759–1833), the abolitionist whose campaigning resulted in the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Eric Carrington Smith was the great-grandson of Abel Smith and derived his middle name from Abel Smith’s brother, the politician Robert Smith (1752–1838), who became the 1st Baron Carrington of Upton in 1797.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Dorothy (1879–1942); later Keith-Fraser after her marriage in 1904 to Captain Hugh Craufurd Keith-Fraser (1869–1906); then Graham after her marriage in 1910 to Captain Jocelyn Henry Clive (“Harry”) Graham (1874–1936); one daughter;

(2) Eric Hyde (later DSO, and mentioned in dispatches) (1881–1964); married (1928) Joan Ankaret Talbot (1901–86); three sons, one daughter;

(3) Gerald Hyde (from 1923 CMG) (1882–1953);

(4) Marjory Mildred (1890–1981); later Snell after her marriage in 1919 to Captain Ivan Edward Snell, MC (1886–1958); two sons, one daughter.

Captain Hugh Craufurd Keith-Fraser, Dorothy’s first husband, was a professional soldier. He began his military career in the Militia and moved to the 1st Life Guards in 1890. He was promoted Captain in 1896 and took part in the Second Boer War in the South African Light Horse, of which he became the Adjutant. From 1903 until his death, he was the Adjutant of the City of London Imperial Yeomanry.

Captain Jocelyn Henry Clive (“Harry”) Graham (1874–1936), Dorothy’s second husband, was the younger son of Sir Henry John Lowndes Graham, KCB (1842–1932), Clerk of Parliaments, and his first wife, Edith Elizabeth Gathorne-Hardy (1847–75), the daughter of Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, JP, PC, DCL, GCSI (1814–1906), an eminent Conservative politician from 1856 to 1892 and since 1892 the 1st Earl of Cranbrook. After leaving Eton, Harry went to the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) and was commissioned in the Coldstream Guards in 1895. From 1898 to 1904 he was aide-de-camp to the 4th Earl of Minto, the Governor-General of Canada from 1898 to 1904. He was released for a year (1901–02) to serve in the Second Boer War, but left the Army in 1904 and from 1904 to 1906 was the Private Secretary of Lord Rosebery (1847–1929), the former Liberal Prime Minister (1894–95). Henry then worked as a journalist on the short-lived Tribune, but became a freelance writer until the outbreak of war, when he rejoined the Coldstream Guards and served with them in France from 1917 to 1918. He had begun publishing light, comic, not to say blackly humorous verse in 1898, when he brought out Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes under the pseudonym Col. D. Streamer, a pun on the name of his Regiment. Over the next 34 years, he published c.70 books, mainly satirically humorous verse and the texts of musical comedies. The ones that he wrote himself included the record-breaking The Maid of the Mountains (1917), which ran for 1,352 performances at Daly’s Theatre, London, A Little Dutch Girl (1920), The Lady of the Rose (1921), and Betty of Mayfair (1924). He also collaborated on English translations or adaptations of The Land of Smiles (1931), The White Horse Inn (1931) and Viktoria and her Hussar (1931). His most popular song, made famous by the Austrian tenor Richard Tauber (1891–1948), was ‘You are my heart’s delight’, from The Land of Smiles, with music by the Austrian–Hungarian composer Franz Lehár (1870–1948); another hit was ‘Good-bye’ from The White Horse Inn. But he had a more serious side, and it emerged in the 12-page-long memoir with which he prefaced his edition of Algernon Hyde’s papers that was published by SPCK in 1919 (q.v.). Towards the end of his life, he became a Trustee of the British Museum.

Harry and Dorothy’s only child, Virginia Margaret Graham (1910–93) (later Thesiger after her marriage in 1939 to Anthony Frederic Lewis (“Tony”) Thesiger (1906–69), also made a name as a humorous writer and contributed many poems and articles to Punch. She was also a film critic for The Spectator (1946–56), a drama critic for The Sunday Chronicle (from 1948), a film and book critic for The Evening Standard (from 1952), and a columnist for Homes & Gardens (1953–82). She attended finishing school with the actress and comedienne Joyce Grenfell (1910–79) and thereafter corresponded with her until her death. Her husband was a Commoner reading History at Magdalen from 1925 to 1928 but left without taking a degree and became the manager of a tea plantation and a merchant.

Eric Hyde was educated at Wellington College, and during World War One he served with the 1st Battalion, the Highland Light Infantry. Of his four children, his only daughter died in infancy; one son, James Michael Hyde Villiers (1933–98), became a distinctive character actor who tended to play authority figures and cold and somewhat effete villains in films, but also worked for the theatre and on TV; and another son, Dr John Francis Hyde Villiers, FRSA, FRAS (b. 1936), worked for the British Council (1960–79) and was the Director of the British Institute for South-East Asia (1978–83).

Gerald Hyde became a clerk in the Foreign Office in 1903 and was promoted to the rank of Third Secretary in the Diplomatic Service in 1907. In 1913, he became Private Secretary to the Right Honourable Sir Francis Dyke Acland, PC (1874–1939), the long-standing MP who, between 1906 and 1939, held four seats for the Liberals and was, from 1911 to 1915, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. In 1921 Gerald Hyde was promoted to the rank of Assistant Secretary and he was the Second British Plenipotentiary at the conference on the status of Tangiers that was held in Paris in December 1923. After being implicated in the celebrated “francs case” of 1928, when three Foreign Office employees were accused of using their position to speculate in foreign currencies, he resigned from the Civil Service, even though he came out of the affair very well. He returned to the Civil Service during World War Two and worked in the Ministry of Economic Warfare, whose Minister was responsible for the Special Operations Executive.

Marjory Mildred became the wife of the barrister Ivan Snell, MC. All three of their children served in World War Two, but their second son, Christopher Villiers Ivan Snell (1921–44), was killed in action on 27 June 1944, i.e. after the fall of Rome, during the fighting near Lake Bolseno while serving as a Lieutenant with the 5th Battalion, the Grenadier Guards.

Wife and children

In 1911 Villiers married Beatrix Elinor Paul (1890–1978) in St Margaret’s, Westminster), and they had one son and one daughter. She later became the Honourable Mrs Walter Gibbs after her marriage in 1919 to the banker Captain Walter Durant Gibbs (1888–1969) (two sons). Villiers and Beatrix lived at 56, Draycott Place, off Sloane Avenue, Chelsea, London SW3, and after Villiers’s death, Beatrix lived at Stanstead Lodge, Stanstead Abbots, Hertfordshire. But according to President Warren, the couple settled in Euston, near the Magdalen College Mission, “to which they gave unstinted work and thought”.

Beatrix Elinor was the only daughter of the author, journalist and Liberal politician Herbert Woodfield Paul (1853–1935) and so a distant relative by marriage of A.C.P. Mackworth. Like his only son, Humphrey Mackworth Paul (c.1885–1958), Herbert Woodfield was President of the Oxford Union (in Hilary term 1906 and Michaelmas term 1875 respectively). From 1892 to 1895 Herbert Woodfield was the Liberal MP for South Edinburgh and from 1906 to 1909, he served as the Liberal MP for Northampton until a nervous breakdown forced him to retire. During this period, he spoke with considerable feeling against imperial expansion, the university vote, the rule of great families in Britain, and Toryism. By 1910 he had recovered sufficiently to become the second Civil Service Commissioner, a post which he held until 1918. His many publications include Men and Letters (1901), a collection of essays on literary and historical subjects; a biography of William Ewart Gladstone (1901), whom he greatly admired; a book on Matthew Arnold (1902), with whom he had many literary sympathies; an edition of Lord Acton’s letters to Gladstone’s daughter Mary (1904); a biography of the historian James Anthony Froude (1818–94) (1905); a five-volume History of Modern England (1904–6), which he reputedly wrote by means of his prodigious memory and without reference to printed sources; a second collection of essays entitled Stray Leaves; a study of the age of Queen Anne (1906, revised edition 1912); and Famous Speeches (1910), an anthology of political speeches from Cromwell to Gladstone. His obituarist described him as “a man of extraordinary cleverness, wit, and learning; he was a very fine talker in a dry and caustic style; in society, he could be charming; and he had a few devoted friends”. But, the writer added, he “found it more difficult than most people to suffer fools gladly”, so that it sometimes seemed

as if a bad fairy had been present at his christening. No account of him could be just which omitted reference to his bitter tongue and the sudden eruptions of something like malignity which would ruin a promise of friendship or freeze a dinner-table which he had just been delighting with his more genial wit.

This, perhaps, accounts for Paul’s failure to rise to a position of greater distinction in public life; his son, Humphrey Mackworth, also failed to fulfil early promise after trying to make his way at the bar and in politics.

Algernon Hyde and Beatrix Elinor Villiers had two children:

(1) Charles English Hyde Villiers, later Sir Charles (1975), MC (1912–1992), who in 1938 married Pamela Constance Flower (1914–43), with whom he had two sons: Nicholas Hyde (1939–98) was lost at sea in mysterious circumstances, and Robert Hyde died at birth in 1943 together with his mother. In 1946 Charles married Countess Marie José de la Barre d’Erquelinnes (1916–2003?), the daughter of a Belgian count, with whom he had two daughters.

(2) Mary Theresa Villiers (1917–1984); later Wilkinson after her marriage in 1945 to Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Peter Allix Wilkinson, DSO, OBE, CMG, KCMG (1914–2000); two daughters.

Sir Charles Villiers, MC, the godson of J.L. Johnston, spent two years working for the merchant bank Glyn Mills before reading PPE at New College, Oxford (1933–36). In 1936, while continuing his work as a merchant banker, he joined the Grenadier Guards; he then fought at Dunkirk and, from 1943 to 1945, served with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in Austria and Yugoslavia. During the war, he rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and in 1970 he was awarded the Yugoslav Order of the People for helping to organize the Yugoslav Resistance. After the war he returned to banking and joined Herbert Wagg & Co., where he specialized in corporate finance. He was made a partner in 1948, and when the bank merged with J. Henry Schroder & Co. in 1960 to become J. Henry Schroder Wagg, Villiers became a Managing Director (1968–71). From 1968 to 1971 he was Managing Director of Sir Frank Kearton’s Industrial Reorganization Corporation, whose task was to improve the competitiveness of British industry via mergers and rationalization. After achieving a considerable degree of success, he became Chairman of Guinness Mahon (1971–76), and also chaired the Northern Ireland Finance Corporation (1972–73). He then succeeded Sir Monty Finniston (1912–91) as Chairman of the British Steel Corporation (BSC) (1976–80) and, not least because of growing political pressure, initiated a difficult strategy of rationalization that included the closure of loss-making plants at a time when BSC was losing £1 million per day. The closure of the Consett steelworks in 1979 caused thousands of redundancies, a three-month-long national steel strike, and losses of over £200 million. It also encouraged steel-using industries to switch permanently to imported steel. Until 1989, Sir Charles remained Chairman of BSC (Industry) Ltd, the subsidiary that had been set up to encourage new industries to provide jobs for former steelworkers by moving into former steelmaking areas. In 1985 he launched the British–American Project, an organization that promotes Anglo-American ties. He also served as a Director of Courtaulds, Sun Life Assurance and Bass Charrington, as a Trustee of the Royal Opera House, and as Chairman of the Theatre Royal, Windsor.

During World War Two, Mary Theresa Villiers served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, but in 1970 she was severely injured in a motoring accident in Kent which left her brain-damaged for the rest of her life.

Peter Allix Wilkinson, whose father was killed in action on 6 February 1915 at Ypres while serving as a Captain in the 2nd Battalion, the East Yorkshire Regiment, came from a military family which included three Generals. After studying Modern Languages at Cambridge from 1932 to 1935, he was commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers in September 1935. He was in Czechoslovakia learning Czech when Hitler annexed the country on 16 March 1939 and after the outbreak of World War Two he was sent to Poland from August to October 1939 with a military mission, whose Chief of Staff was Colonel (later General) Colin Gubbins (1896–1976). Here, Wilkinson observed the effects of Blitzkrieg and reported his findings to his superior officers. But they were dismissed by the French and British General Staffs on the grounds that such tactics could not succeed in Western Europe. He then served as a member of No. 4 Military Mission in Paris and Budapest, becoming acquainted with Peter Fleming in the process (see V. Fleming), and after the fall of France in June 1940 he worked once again with Colonel Gubbins on the formation of “Independent Companies” (the forerunners of the commandos) and “Auxiliary Units” (guerrilla resistance units that were to operate in post-invasion Britain). Gubbins soon recruited him for SOE and he first served with this organization in Crete during the German invasion of 20 May–1 June 1941. He was then transferred to SOE’s Czechoslovakia Section and helped supply Czech agents with the weapons that they needed for the assassination, on 27 May 1942, of Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich (1904–42), a senior officer in Himmler’s Sicherheitsdienst, the Reichsprotektor of Bohemia-Moravia, and, as Chairman of the infamous Wannsee Conference, one of the central architects of the Shoah. Finally, from December 1943 until the end of the war, Wilkinson led SOE’s No. 6 Special Group in Yugoslavia and Austria, a unit that was tasked with hastening the German defeat in those countries. He was decorated by Poland in 1940 with the Cross of Valour, Czechoslovakia in 1945 with the Order of the White Lion, and Yugoslavia in 1984 with the Order of the Yugoslav Banner.

Wilkinson ended the war as a Lieutenant-Colonel, but in 1947 joined the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and spent the next five years working for the Allied Control Commission in Vienna. A career diplomat, he was First Secretary in Washington (1952–55), Secretary-General for the 1955 Four Powers Heads of Government Conference in Geneva, Counsellor in Bonn (1955–60), Under-Secretary in the Cabinet Office (1963–64), Senior Civilian Instructor in the Imperial Defence College (1964–66), Ambassador to Viet Nam (1966–67), Deputy Under-Secretary in the Foreign Office (1967–68), Chief of Administration for the Diplomatic Service (1968–70), and the British Ambassador to Vienna (1970–71). After his wife’s motor accident, he took early retirement from the Diplomatic Service in order to nurse her. Nevertheless, he served as the Coordinator of Intelligence in the Cabinet Office (1972–73), and together with Joan Bright-Astley (1910–2008), who worked at the core of the wartime Cabinet Office and was allegedly one of the three or four women on whom Ian Fleming based the fictional Miss Moneypenny (see Fleming), he co-authored Gubbins & SOE (1993). His fascinating wartime memoirs, Foreign Fields: The Story of an SOE Operative, appeared in 1997 and again in 2002.

Captain Walter Durant Gibbs, Beatrix Elinor’s second husband after Villiers’s death, was the son of Herbert Cokayne Gibbs (1854–1935), the 1st Baron Hunsdon of Hunsdon, and the grandson of the banker Henry Hucks Gibbs (1819–1907), the 1st Baron Aldenham (see E.L. Gibbs). Walter Durant became the 2nd Baron Hunsdon of Hunsdon when his father died on 22 May 1935 and the 4th Baron Aldenham on 21 March 1939 on the death of his cousin, Gerald Henry Beresford Gibbs (1879–1939), who had no male children and whose wife, Lillie Caroline (1877–1950), was the elder sister of William Gilbert Houldsworth. Walter Durant was educated at Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated with a BA in 1910. He was commissioned Lieutenant on 15 February 1911 in the Hertfordshire Yeomanry, i.e. the same Territorial Force regiment as Villiers (q.v.), served in Persia, was mentioned in dispatches twice and promoted Captain on 28 November 1916. He became a partner in the firm Antony Gibbs & Sons (see Gibbs), a Director of Westminster Bank Ltd and Commercial Union Assurance Company.

Captain the Hon. Vicary Paul Gibbs (1921–1944) was the elder son of Walter Durant Gibbs and Beatrix Elinor Gibbs. In 1942 he married Jean Frances Hambro (b. 1923) and had two daughters, one of whom died in infancy. Jean Frances later became Elphinstone after her marriage in 1946 to Reverend the Hon. Andrew Charles Victor Elphinstone (1918–75), a nephew of the Queen Mother); one son, one daughter.

Jean Frances was the third daughter of the banker, politician and civil servant Angus Valdimar Hambro (1883–1957) and his second wife, Vanda Dorothy Julia Hambro (née Charlton) (1885–1981) (m. 1916). He was killed in action during the Battle of Arnhem on 20 September 1944, while serving as a Captain with the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards.

Anthony Durant Gibbs (1922–86) was the younger son of Walter Durant Gibbs and Beatrix Elinor Gibbs and became both the 5th Baron Aldenham and the 3rd Baron Hunsdon of Hunsdon on 30 May 1969. In 1947 he married Mary Elizabeth Tyser (b. 1921), the only child of the shipping magnate Walter Parkyns Tyser (1867–1944) and his second wife Jessie Woodriffe Berkeley Quill (1893–1978); three sons, one daughter. He served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve during World War Two and became a Master of the Merchant Taylor’s Company in 1977.

Education and professional life

Villiers attended St Andrew’s School, Southborough, near Tunbridge Wells, Kent, from c.1893 to 1900, and was then a Scholar at Wellington College, Berkshire, from 1900 to 1902. He was awarded an Exhibition at Magdalen in 1902, when he was only 16, and matriculated there as a Demy on 19 October 1903, having passed Responsions in Trinity Term 1903. Although he began by reading for an Honours Degree in Modern History, he changed to Classics, about which he knew little, and by dint of hard work on his own, he took the first part of the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1905 and was awarded a 3rd in Classical Moderations; he took the rest of the First Public Examination in the following term. He then made rapid and visible progress, much to his Tutor’s evident gratification, and in Trinity Term 1907 he was awarded a 2nd in Literae Humaniorae (Classics). Villiers was over 6 feet tall, and in 1906 he rowed with J.L. Johnston and R.P. Stanhope in the first Torpid VIII that was stroked by A.H. Huth and went Second on the River. In the same year he was President of Magdalen’s Rupert Society, a cross between a debating society and a dining club that existed between 1897 and c.1910 and was probably named after Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619–82), the colourful and impetuous Commander of the Royalist Cavalry during the English Civil War (1642–46). During his time at Oxford, he also became Librarian of the Union.

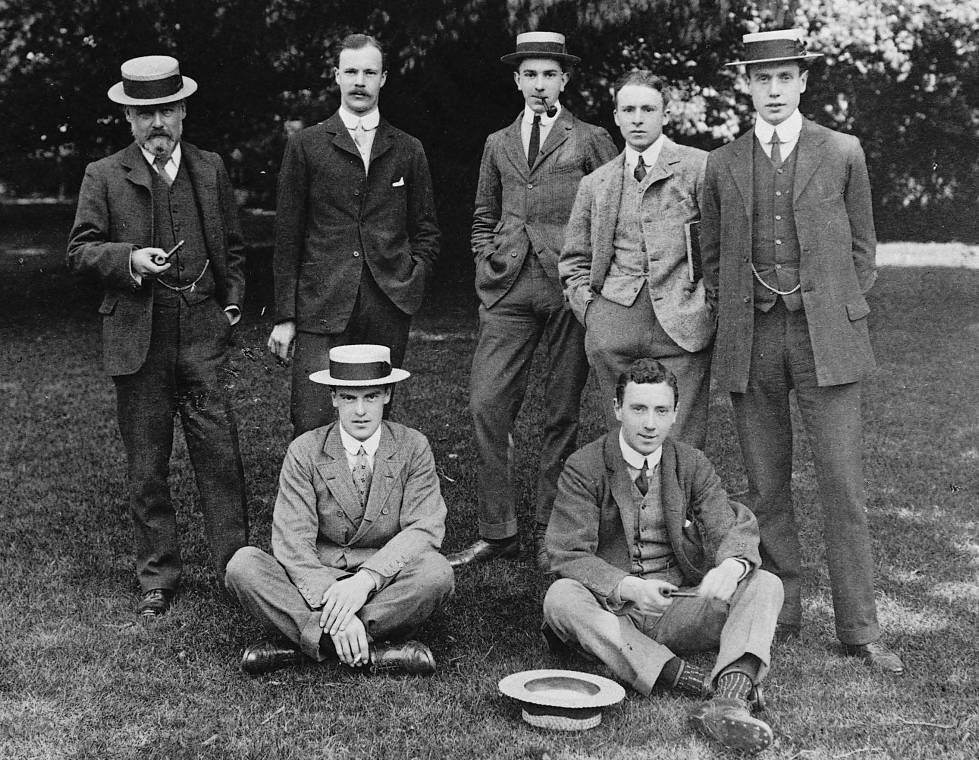

Classical Honours Moderations reading party at Cropthorne, Worcestershire (1904) (Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford). From left to right (standing): Christopher Cookson (Senior Tutor; Fellow of Magdalen 1894-1919); Algernon Hyde Villiers (killed in action 23 November 1917 at Bourlon Wood); Arthur Purling Middleton, Alan Harrison Kidd; Evelyn Godfrey Worsley (killed in action 17 September 1916 on the Somme), the brother of John Fortescue Worsley (killed in action 27 November 1917 at Fontaine-Notre-Dame, near Cambrai); (seated): Alan Campbell Don, Anthony William Chute.

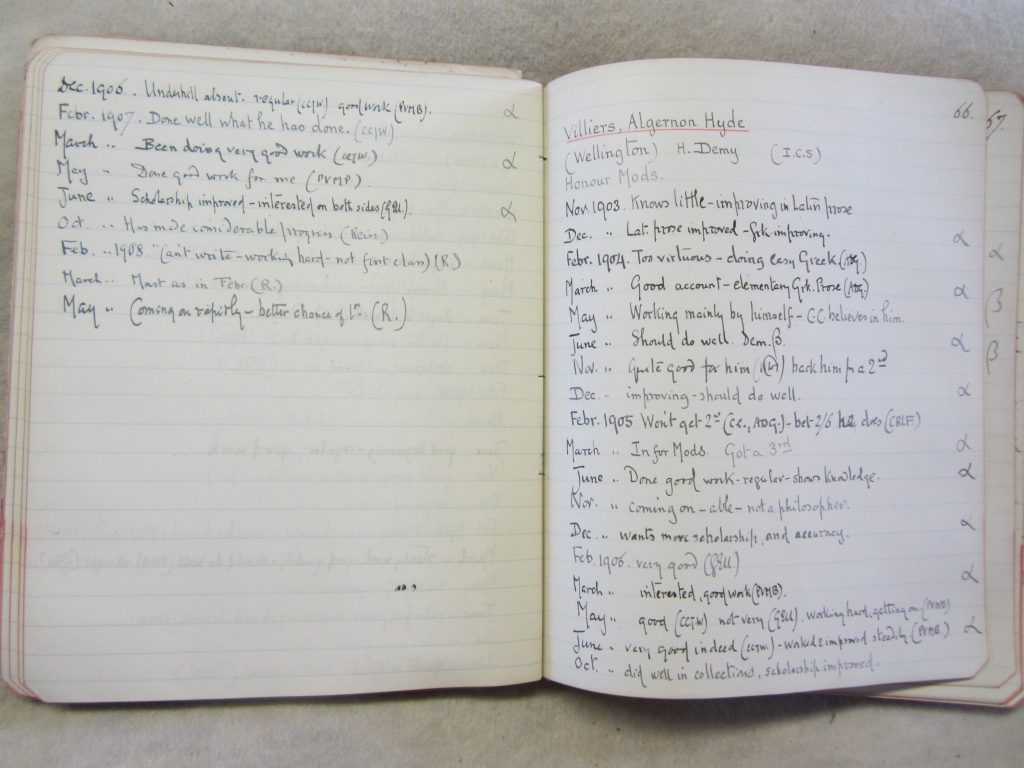

Villiers’s academic record (1903-07), compiled by H. W. Greene et al., Magdalen College Archives: F29/1/MS5/5 (Notebook containing comments by H. W. Greene et al. on student progress [1895-1911]), pp. 65-6.

Military and war service

While at school, Villiers wanted to become a professional soldier, but was prevented from doing so by his short sight. The same defect also prevented him from joining the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps before the war and from being accepted as an infantry officer on the outbreak of war. Nevertheless, on 1 September 1914 he attested for and became a Trooper (Private) in No. 3 Troop of the 1/1st Hertfordshire Yeomanry, a cavalry regiment (Territorial Force) that had been formed on the outbreak of war. He then saw nine days of enjoyable home service in Culford Park, near Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on an estate that had belonged since 1889 to the 5th Earl of Cadogan (1840–1915), the father of W.G.S. Cadogan. As Villiers was with companions whom he liked “more and more”, he complained only about the “pretty loathsome” food and “undrinkable” tea and the job of being “troop orderly”, since it meant fetching the cooking pots and cleaning them before the next meal. He commented: “That is horrible. The cans are called ‘dixies’, presumably from their unutterable blackness, which is only equalled by the greasiness within. One’s hands get into a ghastly condition.”

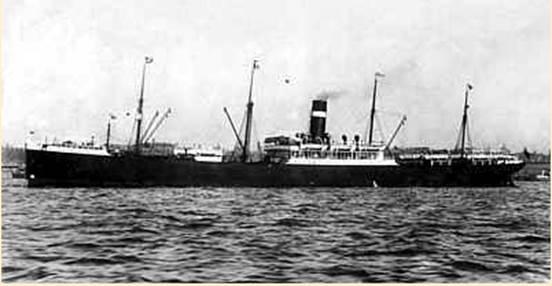

On 10 September 1914, Villiers and his Regiment left England for Egypt on the 8,200-ton liner SS Ionian (1901; sunk by a mine on 21 October 1917 two miles west of St Govan’s Head, Pembrokeshire with the loss of seven lives). The ship carried some 3,600 soldiers and was badly overcrowded, and for the first four days the bad weather caused many cases of sea-sickness, so that Villiers, who had made it his business to distribute bread and tea to the sufferers below decks, described the conditions there as “the inferno”: “the men who two days ago were swearing and bucking and bursting with life now lay in prostrate droves before me, and feebly raised a hand or a faint cry for a crusty bit”.

But his worst experience occurred when he was “told off to a fatigue party” whose task it was “to get provisions up from the hold, and convey them to the proper parts of the ship for use”. The work was hard on the hands and at times repulsive, but Villiers, who was a rich and cultivated young man and thus unused to manual labour, found that he could bear his part, and took pleasure in working hard at it. The party was commanded by “a foul-mouthed old sergeant” who distinguished Villiers “by most courteous observations” on his “supposed unfamiliarity” with such tasks. This led Villiers to realize that “broadly speaking”, he was “treated rather differently from the others”, for he was even addressed as “Mr. Villiers or Sir”, a practice that he “much discouraged” even though it meant that “things were made easier for one”. On the whole, however, Villiers liked being with men who were un- or semi-educated, calling them “kindly fellows and good comrades”, while feeling very much alone “in the crowded nights and hours of leisure” when he had “nowhere to go” and so wrote letters as a way of getting “away from the unending stream of senseless jabber”. Nevertheless, the unwonted experience convinced the naturally religious Villiers that he was safe in the hands of God and he concluded a letter with the observation that it seemed: “as if I had given Him my soul, and he had given me His peace, which is indeed beyond [all] understanding”. He also became familiar with the Army’s strange ways: pointless and boring guard duties, a confused system of court-martial offences, the alternative economic system that existed below decks, ageing, fussy and incompetent officers, impotent NCOs, poor discipline, comic church parades, petty theft, and the helpless ignorance of those at the bottom of the military hierarchy who are brought to realize “that one is only a bit of a machine and not meant to be too inquisitive”.

On 22 September 1914, Villiers’s convoy was passed by the huge convoy that was transporting units of the Indian Army to Europe (see M.A. Girdlestone, G.P. Cable and E.H.H. Rawdon-Hastings), and the sight provoked the normally peaceable Villiers to pen the following, untypically blood-thirsty reflection in a letter:

the thought of the Sikhs and Gurkhas knifing les sales Alleboches gives me intense pleasure. They’ll fight like devils, I dare say, and let the enemy know what it means when you take on the British Empire. Almost daily in these times one feels the great resources we are slowly displaying to drive home victory to the utmost. One must hope for this, mustn’t one, though it sounds vindictive, and in the end I believe our English system of life, on which conscription is so hard to graft, may turn out to be the best and the determining factor in this deadly business.

“His brother officers cannot speak too highly of his capacity as a leader, of his charm as a companion, & of all those splendid qualities […] which made him the leading spirit of his mess and the idol of his men. He loved his men, & they loved him, & his invincible optimism carried him safely through those dark hours of danger & discomfort which set weaker men grumbling & despairing” (letter from a Divisional Staff Officer to Villiers’s widow).

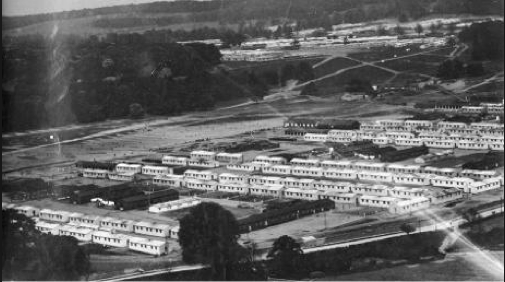

The Ionian arrived at Alexandria early on the morning of Friday 25 September 1914, and at dawn on 26 September, after a day of fatigues in the Egyptian sun and a night of “hideous discomfort” on a crowded train, Villiers’s Regiment, now part of the “Force in Egypt” (Egypt Expeditionary Force from March 1916) that was commanded by Major-General Sir John Grenfell Maxwell (1859–1929), arrived at Abbassia Barracks, in a suburb of Cairo, with their “beautiful airy dormitories with verandas north and south […], with shower-baths and glorious Dragoon Guards welcoming us to breakfast”. Villiers wrote enthusiastic letters to friends and relations about the unfamiliar beauty of the desert and Islamic architecture, and the magical blaze of the night sky, and, just occasionally, about the Pyramids, “the two immortal masses, wonders of the world”, which could be seen from Abbassia, 14 miles to the west, when atmospheric conditions were right. But he also wrote with considerable humour about one of the givens of military life:

Things that really matter are taken with calm, while the grousing and cursing over trifles is unending. For instance, sea-sickness and that night journey, and the following night’s trek to Cairo were all taken exceedingly well; but you’ve no idea of the outcry there is if anything goes wrong with the rations, or the canteen runs out of jam or beer. If we heard we were to go into action this evening, there would be hardly any agitation; but suppose it got about that 1d a day was to be stopped from our pay to (say) keep our kits in repair free of charge, or some such convenient scheme, the to-do would be fierce and interminable. The tea and the cooking of the meat arouse the most bitter passions. You would say superficially that we worshipped the Belly with wholehearted monotheistic devotion.

But by 25 October 1914, Villiers was starting to realize that the unaccustomed nature of his life was destroying “the many little certainties on which we commonly depend” and, besides replacing them with the “gloriously defined” habits of the military life, allowing “the true values of life” to “emerge with irresistible clearness”.

Once in Egypt, which became an official British Protectorate on 18 December 1914 under the nominal rule of Sultan Hussein Kamel al-Majd (1853–1917), Villiers’s Regiment and the 2nd County of London Yeomanry became part of the Eastern Mounted Brigade, and from 19 January 1915 the two regiments became the Yeomanry Mounted Brigade in an army which, by now, numbered 70,000 men. The Regiment then helped defend the Suez Canal and when, on 3 February 1915, the day when elements of the Turkish Army unsuccessfully advanced on sections of the Suez Canal, Villiers’s Regiment left its comfortable barracks, crossed the Canal eastwards and pursued the Turks into the Sinai Desert, where they dug themselves holes and “stretched our waterproof sheets over the top to shelter us from the cold wind and very heavy dews”. The British pursuit ceased on 17 February after reconnaissance units had reached Katiah (also Katia, Katiya and Qatia) without making any significant contact with the Turks, and in a letter that he wrote on that day, Villiers described what a “wonderful experience” it had been to march, together with elements of the Indian Army, along the “great caravan route” that had been used by Joseph and Mary when fleeing from King Herod. His Regiment then returned to Ismailia, in north-western Egypt and to the west of the Suez Canal.

On 2 March 1915, Villiers, who had been promoted Honorary Lance-Corporal, applied for a commission in The Lothians and Border Horse, another cavalry regiment (Yeomanry) that had been created in April 1908 as part of the Territorial Force, and on 10 April 1915 his request was granted. So, on 30 April 1915, i.e. before his old Regiment became a dismounted unit and participated in the Gallipoli Campaign (August–December 1915), Villiers left Egypt aboard the cargo steamer SS Port Lincoln (1912; torpedoed as SS Maritima on 2 November 1942 by UB522 in the North-West Atlantic with the loss of 31 lives).

He arrived in England on 12 May 1915, where he was given a Territorial Commission and assigned to the 2/1st Lothians and Border Horse. This Territorial Regiment had been on home service since the outbreak of war and was tasked with the defence of East Lothian. Its officers, including Villiers, who held his Territorial Commission until 26 March 1917 and was promoted Lieutenant (TF) on 1 June 1916, were quartered in Amisfield House, Haddington, a magnificent Palladian mansion 20 miles to the east of Edinburgh that had been built in c.1755 and would be demolished in 1928. In 1915, Villiers’s new Regiment formed part of the 2/1st Lowland Mounted Brigade, but in March 1916 this Brigade was redesignated the 20th Mounted Brigade. Then, in July 1916, the 2/1st Lothians and Border Horse became a cyclist unit in the 13th Cyclist Brigade; and finally, in November 1916, it joined the 9th Cyclist Brigade, which was also stationed at Haddington. Unfortunately, no War Diary exists for these units and Harry Graham (Villiers’s brother-in-law) in his edition of Villiers’s letters published none that were written between 17 February 1915 and 8 April 1916.

But we do know that during his time in Egypt Villiers contracted dysentery, possibly because of the appalling army diet, about which he frequently complained in his letters. As a result of the dysentery, he developed persistent haemorrhoids, for which he underwent an operation in the 2nd Scottish General Hospital, at Craigleith, Edinburgh, in about March/April 1916 and from which he did not completely recover until 2 August 1916, when he was declared fit for service once more. During this period Villiers had quite a lot of time on his hands, and although he was already a devout Christian, he seems to have undergone a major revelatory experience in late summer/autumn 1916 that caused him to embark on a systematic study of the Bible, especially the Psalms and the New Testament. Over the next year, the final year of his life, that same experience would generate an uninterrupted stream of thoughtful, unconventional and striking theological insights and reflections which he included in his letters to his friends and family. Thus, in a letter of 10 December 1916, he remarked “that the striking thing about Christ’s example is not His various ‘works,’ but the fact that with such power as He possessed He did so little and left the world practically as He found it” and that even in his preaching “there is a complete absence of that urgency which is so characteristic of St. Paul”.

After returning to duty in one of the East Lothian cyclist brigades, in which he was promoted Temporary Captain (TF) on 1 January 1917, Villiers was sent to Prestonkirk (East Linton) during the winter of 1916/1917, where he helped run a machine-gun school. Here, his increasing preoccupation with religious questions led him, in January and February 1917, to write four papers on “the deep things of God” which he then read aloud to “the leading spirits” among his trainees and which Harry Graham would, after the war, include in his edition of Villiers’s letters (pp. 162–99) “in the hope that it may inspire and stimulate the thoughts of a circle of readers wider than that of which the moral and physical welfare was[,] in his lifetime[,] the author’s special concern”. For, Graham continued,

When the Angel of Death is abroad, when his shadow darkens every home, and the beating of his wings is re-echoed in many a fearful heart, there is courage and consolation to be derived from the teaching of one who had sought and found that peace of God which passes all understanding, who had learned by experience, and by his own example proved, that to be spiritually minded is Life Eternal.

Despite their brevity, the four talks found considerable resonance among the trainee machine-gunners, and they are remarkably interesting even today. For although Villiers was a committed member of the Church of England and, despite his critical reservations, took pleasure in the beauty of its cathedrals and rituals, his talks are free from established religiosity and that combination of “conventional piety” and abstract remoteness which, in his letter of 21 September 1917, he would describe as “clerical shop”. Indeed, his letter of 22 October 1917 is a good index of how much he disliked lazy, “supine” clerics who sit “like a dough pudding smiling amiably at nothing”. Moreover, although he strongly believed in the rightness of the Allied cause, his talks are free from Edwardian jingoism, and although his letters frequently castigate the “beastly Boche”, the Prussian state-form, “Prussian ideas”, “the man-eating ants of Prussia”, the “German way” and the “hideous outrage” of the “German national idea”, and although his letter to his son Charles of 8 November 1917 would express his frank enjoyment of seeing “the horrible German fall or scuttle for shelter”, his four talks are free from the belligerent patriotism that tended to alienate ordinary soldiers when it was dished out to them at church parades by non-combatant clerics.

Villiers’s talks have two very clear features. First, they evince a sympathetic understanding of his men’s beliefs and concerns, and on 29 September 1917 Villiers would write of being “surrounded by young men of many excellences, good-humoured, kindly, not unduly coarse many of them, and with plenty of courage and capacity, but, as far as one knows, living quite without thought of God”. Unlike many a professional clergyman, Villiers possessed a very strong sense of what his men thought about religion and spirituality. Consequently, and in contrast to the brave but more conventional P.W. Beresford, he makes no bones about the dullness and absurdity of so much established religion and repeatedly asks his listeners to ignore such trivia and put those “gifts of the spirit” with which they were already familiar – “calm and cheerfulness, comradeship and courage” – into a broader spiritual perspective. Second, Villiers’s talks are redolent of his conviction, already outlined in his letter from Abbassia of 25 October 1914, that war, for all its horrors, gives men a better chance of putting aside what Blaise Pascal (1623–62), the French mathematician and mystic who Villiers would particularly come to value, had termed divertissements, and so of developing that innate spiritual strength which was, in Villiers’s view, “part of a much bigger and stronger Being” who is everywhere at work in the world. Additionally, and despite his patriotic commitment, Villiers nowhere in his talks blames any particular nation for inaugurating “the greatest and weariest slaughter ever known”, but sees it as the product of the spiritual vacuum, the social dissatisfaction and the existential insecurity that were the by-products of the immense achievements of the nineteenth century. And without being explicitly political, Villiers also seems to appreciate the extent to which religion in contemporary Britain is tainted by a dangerous class consciousness, for

we can see very plainly what [Christ] thought of any superiority of education, social position, or of religious observance, when it did not prevent a want of tenderness for the sins and sorrows of other men and women.

More importantly still, Villiers firmly rejects a moralistic view of religion in general and Christianity in particular, calling it a “lawyer’s view of right or wrong” which is “the leaven of the Scribes and Pharisees” and against which “Christ was always protesting”. A proper morality, he argues, flows from and is not the presupposition of an increased spiritual self-awareness. Thus, without using technical doctrinal terms, he rejects the central Calvinist doctrine of substitutional atonement as “revolting” on the grounds that “it is quite impossible that Christ was turning God from His previous intention of destroying the world […] sending every Jack man of us to hell”. But far from reducing revealed religion to a demythologized kerygma or what the anti-Nazi German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–45) would, in his letters and papers from prison, call a “religionless Christianity”, Villiers has a striking knack of thinking tangibly and experientially about such central theological concepts as prayer, revelation, judgement, redemption, evil, sin, the Kingdom of Heaven, the ecclesia, the imitatio Christi, discipleship and the divinity of Christ. For Villiers, conversion does not mean a sudden assent to a doctrinal system that will one day assure the subject a place in Heaven, but a 180-degree turn from a self-centred existence to one that is secretly guided by an interventionist God whose purpose “did not begin with the coming of Christ, nor end with his death” and involves constant renewal “as the woods and fields are for ever renewing themselves”.

A naturally sceptical reader may find it a little odd that a machine-gun specialist should, in time of war, conclude his thoughts with St Paul’s final injunction from Chapter 4 of his letter to the Ephesians: “‘Let all anger and clamour and evil speaking be put away from you with all malice, and be ye kind one to another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you.’” But had Villiers survived and followed his hermeneutic and professional instincts, he might well have become a considerably more significant theologian than his close friend, the more orthodox and church-centred Johnston.

Early in 1917, Villiers’s medical condition recurred, and on 22 March 1917 he was sent on leave for a second operation, this time in April 1917 in the 2nd London General Hospital, 552 King’s Road, Chelsea. By now, his experiences in the machine-gun school, coupled with the difficulties that his painful medical condition must have caused a cavalry officer in a bicycle regiment, led him to conclude that if he wanted to get to the Western Front and fight the enemy in the most effective way, he would have to join the Machine Gun Corps (MGC). This had been established in October 1915 to provide the Army, using three Companies per Division (a number that rose to four in February/March 1918), with improved and more concentrated machine-gun fire directed by specially trained machine-gunners. So on 4 April 1917, Villiers resigned his Territorial Force commission and dropped back to the rank of Second Lieutenant so that he could join a Regular front-line unit. The MGC training centre was at Harrowby Camp, near Grantham, Lincolnshire, and nearby Belton House, a mansion that had belonged to the Brownlow family since the sixteenth century and would be acquired by the National Trust in 1984.

Villiers arrived at Harrowby on 6 May 1917 to participate in a serious machine-gun course, and for several weeks was “lost to the world” because of “the minute study” of the things that were taught there. Villiers excelled on the course, but continued with his theological reflections, mainly on the divine/human relationship, which he set down in yet more letters. So on 29 May 1917 he wrote to a friend:

It is the most wretched thing to feel alienated from God, for it means a contradiction in one’s own soul which is the gist of unhappiness. One longs to be at one with oneself, and at peace with Him, and it seems so hard that the other law should be working in us, which we would gladly expel but cannot. It is a mystery, but I expect that progressively Christ can, and will, lead us out of the maze. So one must never despair of oneself or Him, but make the most of our best moments, enjoying them, realising how much best they are, and how unnatural, in a sense, is everything which is out of tune with them and which obscures the truth in them revealed.

During his time in Lincolnshire, Villiers visited Boston, where, “in glorious St. Botolph’s under the stump”, he bought a “little book” of quotations from Pascal’s Pensées that he would frequently cite over the months to come. But while waiting to be sent to France, his medical condition occurred yet again, albeit less severely, and in the second half of July 1917 he had a third operation, this time in the 2nd Eastern General Hospital at Brighton.

On 26 March 1917 Villiers was seconded to the Machine Gun Corps, on 1 April he was given a Regular Commission as Temporary Lieutenant, and on 29 July 1917, Villiers, now a replacement officer who had been assigned to No. 2 Section of the MGC’s 121st Company, arrived at Boulogne and was sent to a holding camp in Ostrohove, one of the town’s southern suburbs. The 121st Machine Gun Company, which consisted of 16 sections, had been formed at Grantham on 14 March 1916 and arrived at Le Havre on 17 June 1916. On 19 June 1916 it became part of 121st Brigade, in Major-General John Ponsonby’s (1866–1952) 40th Division, a so-called Bantam Division that consisted mainly of men who were under regulation height but otherwise fit for active service. The 40th Division first saw action during the Battle of the Ancre, one of the closing phases of the Battle of the Somme, and then again in late April/early May 1917, during the German withdrawal eastwards to the Hindenburg Line, when it took part in the capture of Fifteen Ravine and the villages of Villers Plouich, Beaucamp and La Vaquerie, nine miles to the south-west of Cambrai, the key German stronghold and railhead to the east of the Hindenburg Line. By 1 July 1917, the Division was near Péronne, in the Villers-Guislain/Gauche Wood Sector of the front, opposite Honnecourt Wood. Villiers knew France from the pre-war years and spoke French reasonably well, and he was elated to be back there despite the crowded conditions in the holding camp and the continuous rain, not least because “the utmost bonhomie and cheerfulness” were everywhere conspicuous.

He stayed in Ostrohove Camp until 4 August, reading Pascal and studying St Luke, Chapter 11, especially verses 37 to 54, where he perceived parallels between “the woes of the Pharisees” and those of “our well-meaning, trumpery English life, both public and private”. He also reached the conclusion “that there are, in all probability, far more people who have not forsaken judgment [– a true estimate of life’s values], and the love of God, nor allowed themselves to be given to the folly of ambition and vanity, than we commonly suppose”. Then, on 5 August, he travelled by rail to a camp on the high ground above ruined and uninhabited Péronne, passing as he did so near Albert and through the landscape that had been devastated by the fighting of the previous year. He wrote in a letter:

One can see that there were once woods here and there, but nothing but a few bare stumps remain, and they do not [in] the least break the sense of smooth annihilation – the blotted-out look of the land. In the distance I could see the soft, furry brown slopes, just picked out with white, where I suppose trenches had been, but close at hand one does not notice them. The wild-flowers have mastered them already. In one or two places one can imagine what was a village. Perhaps one house-corner suggests it – the only thing standing; and then one can see a few foundations, otherwise – blank. […] There was not a living creature to be seen but a couple of magpies and a couple of rooks. The river has the appearance of a great marsh, most beautifully still and mysterious […]. It was a lovely afternoon, breathless, and violet skies to the east, with a luminous western heaven. […] Even the touching groups of graves could not make the scene pathetic; it was too fine a burial-ground for sadness, where the brave bodies lie, crowning as it were the dead landscape with deep loneliness, and undisturbed or intruded upon by any but their passing comrades. We were by then in a truck – the familiar Hommes 40, Chevaux 8, and everybody was very silent.

On the following day he joined his Company in the trenches at Gonnelieu/Villers-Guislain, a fairly quiet part of the front that was not far from Cambrai and just to the south of La Vacquerie, having ridden the last few miles in the dusk on “a bold, black light draft horse”. He then spent the following two days inspecting “numerous tiny little nests of destruction for the Boche”. On 9 August, he wrote an extended meditation on the place of God amid the devastation of war and the spiritual confusion that it occasioned, and reached the conclusion that God was on neither side “in the sense in which I am on one side and a given Boche on the other”. He continued:

Don’t look for God’s action in the same direction as you would for a man’s. He belongs to another order of peace and power and fullness to us, but He will come and be with us if we could only manage to let Him in, if we only could see the things that belong to our peace. […] I feel it hard […] to keep looking in the right direction. … I build fancies of ambition, but I know very well that my real happiness is not made up of getting on, and being rewarded or acknowledged by men, but in the simple thought of my destiny being guided by Him. When I feel clear on that point, then I am not worried, or anxious about success, or failure, or recognition, then I always enjoy the sense of triumph through my tiny atom of love for him leading me to the marvellous hem of His garment.

The following 25 days in the trenches were uneventful and Villiers quickly became accustomed to his ugly and cramped surroundings, the pouring rain, working at night and getting plastered with mud when doing so, sleeping during the day in “a sandbag and steel shelter”, putting up with the vagaries of army cooks, and providing occasional supporting fire for the artillery. His main tasks were spotting for the artillery and the machine-gunners, and “map-spotting – i.e. finding the exact position on the map of an object seen through the telescope”. But despite the routine work and its attendant squalor, Villiers continued with his theological meditations, especially on St Luke’s Gospel, and in his letter of 16 August he set out the daring idea

that all the great phrases of religious experience, which have in the past seemed wonderful, but beyond my literal comprehension, are really true in quite a simple way, and require no great or special endowment, or temperament, for us to realise them in common life.

He also found considerable comfort in what, for him, was Pascal’s “greatest phrase”: “Be comforted; thou wouldst not seek me if thou hadst not found me.” So although he conceded that “it is a struggle here with the crowded quarters, hours all upside-down, and generally cramped and awkward conditions, to give full play to the best things within one”, he could also declare, on 25 August, that the success of his work as a machine-gun officer made him “very happy” and caused him to “enjoy life” really thoroughly, and then, on 27 August, conclude that “less clear [spiritual] progress here may carry one farther than one would be able to go under more normal circumstances”. Thus, as he recounted in his letter of 29 August, although his Commanding Officer had forbidden him to hold little religious services for his men because it was causing problems with those who were Roman Catholics, he had been able “to accept this without any bitterness, and also not to mind a bit the thought of having been laughed at”, concluding that that is what he meant by “growth in strength of soul”.

On 31 August, Villiers’s Company was involved in a “little battle”, his first experience of having his guns called into action: “Of course I loved it”, he wrote in a letter on the following day,

and on the whole my fellows did quite well. Interesting points to me were brought out, and it was great fun to have everybody working, to appreciate my own part, and also the function assigned to us as a whole. The incident has bucked my men up very satisfactorily.

From 6 to 8 September, while the normal officer was in hospital, Villiers acted as Company Transport Officer and rode to Épehy, about four miles to the south and away from the front, where he enjoyed a whole room to himself in a fly-blown hut and a change of clothes, “a good clean up”, proper baths, and the privilege of wearing pyjamas once more. Here, inspired by St John’s Gospel, he wrote a long letter about the essence of religious experience and came to the conclusion that “the aim of life, the function proper to human nature” was “just to be nearer to God”. He also read through the Psalms, especially his favourites, Psalm 37 and Psalm 27, both of which related directly to his most intimate and immediate theological concerns. On 8 September he was back with his Company feeling “very calm and collected, with things well in hand so to speak”, and “with a sense of freshness which is very satisfactory after so short a rest”.

The next 18 days were also uneventful, but at 19.30 hours on 26 September, the opening day of the phase of the Third Battle of Ypres, well to the north, which became known as the Battle of Polygon Wood, Villiers’s Company, which was still in the Gonnelieu sector of the front, was involved in a major one-day raid on the German lines:

It was a great affair. The heavies were up and were firing all day, and at dusk the fun began. By Jove! it was magnificent. The great feature was the burning oil, which bursts in great sheets of flame, lighting up the whole scene with a savage brilliance. [The] M.G.s were in great force, and the heavies poured forth their huge crumps in an endless strain. Sudden momentary silences occur, which is odd. You think something has happened, the stillness is so deep, and in a second or two the chorus opens again. The Boche line was a chaos of smoke and flame. At first one felt the bombardment [was] a glorious spectacle, but as it went grinding on through the hour and ten minutes of its hideous course[,] I began to feel it was horrible and hideous only. There was something dreary about the one-sidedness of it. The Boche put back a certain amount of stuff, but broadly one had the sense of our just grinding him down laboriously, unimaginatively, almost ridiculously. Altogether it is a Boche business, to my mind, a bombardment. We should never have done that sort of thing if he had not taught us. I can feel no pity for him. He has brought us down to his beastly level in too many ways.

The 12th (Service) Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment (121st Brigade), which contributed six parties consisting of eight officers and 236 other ranks (ORs) to the raid, performed particularly well and captured one light machine-gun and five prisoners. But the cost was heavy and of those from the 12th Battalion who took part in the raid, five officers and 92 ORs (i.e. 40 per cent) were killed, wounded or missing. On 30 September, after his Company had had “some fun shooting today”, Villiers summed up the essence of his religious beliefs,

so firmly grasped by the two greatest Christians of all time, St. Paul and St. John, that God is not only above us, but in us. To set him over [and] against His world, and say what can He, or can He not, do with it, is a hopeless way of approaching the question. Some form of Logos idea is vital.

On 1 October 1917, after completing the letter, Villiers set off on leave, which involved a complicated journey to Le Havre, where his father was living at the time and during which he had a long conversation about the war with a French commercial traveller whose “loathing of the Boche” he found “very sympathetic”. Villiers spent his leave sight-seeing, dining and discussing the war with dignitaries, and enjoying clean sheets and a comfortable bed. He returned to his Company on 7 October, and by the evening of 12 October he and his Company had been withdrawn to billets in the intact village of La Herlière, near Beaumetz-les-Logis, about 30 miles east of Cambrai and eight miles to the south-west of Arras. Here they rested and trained for just over a month, and Villiers, who combined a mystical temperament with a painter’s eye, enjoyed the landscape:

The sense that I have of the landscape as a whole is that it is absolutely free from anything like meretricious, exciting, and ephemeral beauties, and that it asserts with extraordinary authority its own absolute value and fitness. It has the finest feminine qualities of quiet and dignity, with a touch of mystery, expressed in the simplest and most gracious form. There is nothing heavy or magnificent, nothing bold or challenging, but an appeal as of something delicate, almost frail, an influence as of something assured and final, knowing all things and hoping all things. A very wise, mature country, patient and inwardly beautiful.

On 22 October, Villiers was sent on an errand to Doullens, 12 miles to the south-west, and while returning in a bumpy lorry, he underwent a Damascene experience during which the value of “the things of the Spirit” caused him to see with greater clarity than ever before that “[Christ] puts an end to our confusion of mind where, without Him, vanity, love of pleasure, laziness, conceit, and irritability, are alternately master”, and that “[Christ’s] rule in the heart gives order, patience, power, serenity, and that deep sense of joy which one has in things being as they should be”. “Well, no”, he concluded,

I think active service on the whole makes it easier to be a Christian. The disturbance and publicity of which life so largely consists are against it, certainly, but on the other hand the need for God is great, and the clean and honourable life of a soldier is given you in exchange for the mean complacencies of a money-getting existence. There is less love in civil than in military life.

On 26 October, Villiers and his Company arrived in Étaples, on the coast just behind Le Touquet, and then took part in some kind of fire-power demonstration alongside the artillery at Camiers, some three miles to the north, in front of “a great gathering of notables” from all the Allied armies. By 31 October, Villiers and his men were back at Sombrin, about four miles north-west of La Herlière, where Villiers was not only the Company’s billeting officer, but had also begun a new job that involved liaising with the artillery. He and his unit stayed here until about 17 November, the day when he wrote his last published letter, and he spent most of this period participating in increasingly tough training schemes and censoring his men’s letters for information that could be of use to the enemy. But he also found the time to play the occasional game of football, discuss theology with the highly conservative local Roman Catholic curé, and meet up with his brother-in-law Harry Graham.

He also, of course, found the time to pursue his theological thinking, to re-affirm his belief in the availability “for our constant use” of “an unseen source of personal power” and, within this overall context, to meditate on wickedness and sin, a subject that had hitherto come low on his list of theological priorities: “God is in His world facing the necessity of sin, and for ever redeeming it, by working it into the triumph of goodness.” He also expressed the wish that he had sufficient time to arrange his “theologico-seraphic fancies into a series of papers” and “straighten them out into a consecutive view of the whole great subject”; and in his penultimate surviving letter he hinted that he was thinking, when he had “more fully tested the power that worketh in us and proved beyond any possibility of doubt that it is the Lord”, of becoming some kind of evangelist or social worker. He explained his thinking as follows:

it looks to me as if that time must soon be coming. After all, I have lived by His light for over a year now, with the torch burning away in the pitcher, only showing through chinks to the nearest at hand, and soon the signal ought to come to break the pitcher and blow the trumpet, and shout for the Sword of the Lord. Perhaps it never will.

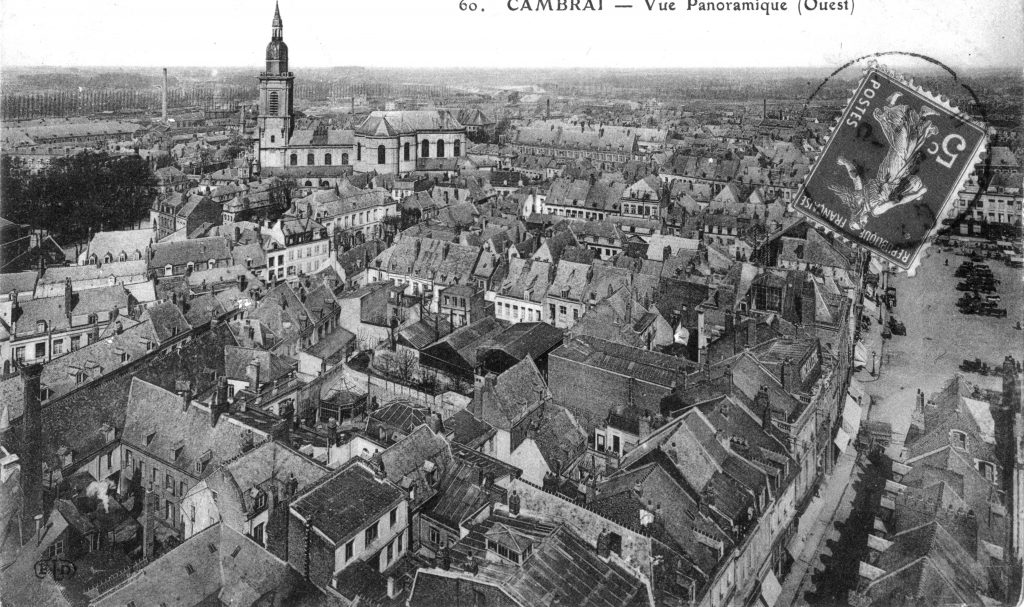

On 20 November 1917, the first day of the ultimately disastrous Battle of Cambrai, British and Canadian forces began their attempt, supported by 437 massed Mark IV tanks and over a thousand guns, to break through the Hindenburg Line along a slightly curving, seven-mile front between the Canal de l’Escaut and the Canal du Nord, and capture Cambrai. The attack was initially successful: in some places the Allies managed to advance some four to five miles across three lines of German trenches, taking 8,000 prisoners in the process, and all along the line the German defenders were forced back into Cambrai. Indeed, the attack seemed so successful that when the news of it reached England on 23 November, church bells were rung for the first time since August 1914, and people began to hope for a rapid end to the war.

But the German positions were naturally protected on three sides by the River Scheldt, the River Sensée, and the dry Canal du Nord, and, on the fourth (western) side of the rectangle, by the wooded heights about five miles west of Cambrai that were known as Bourlon Ridge and which abutted the village of Bourlon to the north. Moreover, the primitive, slow-moving British tanks made such easy targets for the German gunners that 65 were destroyed on the first day of the Battle alone, with a further 114 being ditched or put out of action by mechanical problems. So the advance was slowed down, and during the first day’s fighting only half the objectives were taken, and of those which remained in German hands, the most important was Bourlon Wood, the dense, 600-acre, diamond-shaped forest on top of Bourlon Ridge, which effectively blocked access to Cambrai.

On the following two days, 21 and 22 November 1917, Bourlon Wood became the focus of the Allied attack, but to no avail, and the British and Canadians even lost some of the ground which they had taken on 20 November. So on Friday 22 November, when the 40th Division was away from the front line at Beaumetz-lès-Cambrai, about six miles south-west of Cambrai itself, it was transferred into IV Corps, and at 16.00 hours its General Officer Commanding, Major-General Sir John Ponsonby, received orders to relieve the exhausted 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division at Graincourt-lèz-Havrincourt. This Division had reached but had not been able to capture Bourlon Wood during the intense fighting of the previous two days, and it had lost 75 officers and 1,613 ORs killed, wounded or missing. But because of the crowded roads and the bad weather, which had rendered the battered roads almost impassable, it took the 40th Division about 15 hours to reach the front and get into position just north of the village of Anneux, which was a mile or so to the south of Bourlon Wood and a little further on than Graincourt-lèz-Havrincourt.

The plan was for the 56th (1st London) Division, on the very left of the front which ran from the north-west to the south-east, to advance north-eastwards towards Inchy-en-Artois, for the 36th (Ulster) Division, on its right, to advance along both sides of the Canal du Nord and attack the village of Bourlon from the west, for the 51st (Highland) Division to advance north-eastwards, recapture Fontaine-Notre-Dame (see J.F. Worsley) and take Bourlon village from the south-east, and for the 40th Division to drive northwards and capture Bourlon Wood and village from the south and west. So at 10.30 hours on 23 November 1917, the first day of the Battle of Bourlon Wood (23–28 November 1917), after a 20-minute artillery barrage, two of the 40th Division’s Brigades (the 119th and the 121st) began their attack in misty conditions supported by 32 tanks out of the 92 that were assigned to the attack. Both attacks meant advancing about 1,000 yards down a long slope from the start-line at Anneux, crossing a sunken road, and then advancing up another slope. The 119th (Welsh Bantam) Brigade managed to get halfway or more through the wood and even to penetrate the well fortified and heavily defended village of Bourlon, just to the north of the wood. Meanwhile 121st Brigade, to which Villiers’s machine-gun Company was attached, took heavy casualties as it tried but failed to take the village, because of the treeless terrain, accurate sniping, intense shelling, and machine-gun fire. By the evening, casualties in both Brigades were severe and the individual battalions were broken up and confused. Sidney Allinson describes the chaotic situation at the end of 23 November as follows:

The Welsh Brigade was in command of most of the wood, but was under constant attack by German infantry from Bourlon village and artillery in Fontaine. The 121st Brigade had units inside the village but had lost touch with them, and all battalions were by now scattered and intermingled.

As the letter reproduced below confirms, Villiers’s Commanding Officer had ordered No. 2 Section, commanded by Villiers, to follow the final wave of 121st Brigade’s infantry over the top onto Bourlon Spur, to support them as required, and to consolidate any gains, whilst the other three sections stayed behind to provide covering barrage fire. Although the main body of Villiers’s section was about 400 yards behind that final wave, Villiers himself was with it, leaving his second-in-command to lead the section. The attack went well up to the first objective, but when it was held up by intense enemy machine-gun fire, Villiers went back to his section in order to bring its guns to bear and help the British troops to advance. But at 11.30 hours Villiers’s immediate colleague, Lieutenant Arthur Philip Matthews Male (1892–1917), who had got married in May 1917, was killed, and at 12.00 hours, while moving between his guns in order to direct their fire onto isolated enemy posts, Villiers was hit in the head by a sniper and killed in action, aged 31. His Commanding Officer, who had the very highest opinion of Villiers’s quality as a man and efficiency as an officer, sent his wife the following description of the place and circumstances in which he met his death:

I went to his guns just before dawn on the 23rd, & found him sitting under a bank – asleep. I woke him & we talked over the orders he had had some hours before. We both knew that he had a dangerous task to perform. He had read his orders, decided on his plans & gone off peacefully to sleep. He was extraordinarily happy & as keen as a boy. I thought at the time how ready he was for whatever might come. […] He was going on ahead of his men to reconnoitre. Later on, at dusk, I went up near the spot myself. It was a hillside with longish rough grass: on the right there was a big wood [Bourlon Wood] from which the hill sloped down. A flock of mallard flew across the sky just before dark & I thought that he would have liked that: he was very fond of birds. Despite the fact that there was a good deal of rifle fire and some shelling there was a kind of peacefulness over everything, & he himself was very peaceful.

Not long after Villiers’s death, his Sub-Section Officer, who had been wounded in the thigh on 23 November, wrote a long letter to his widow of which a copy – undated and anonymous – was sent to President Warren. It not only contains a detailed account of the action – which dovetails precisely with the one given above – it also contains a remarkable, fulsome and very moving assessment of Villiers’s worth as an officer and a person which, with the exception of one sentence, avoids the usual clichés of such eulogies:

The day before we went into action the C.O. had the details of the attack given him, and decided that our section should go over the top behind the last wave of infantry to help them in case of need, and to consolidate the objectives in turn. The remaining three sections, it was arranged, should stay behind to do barrage work. The C.O. at once decided that No. 2 Section should be the one to go with the Infantry. This was a great honour and compliment to the section in general, but to your husband in particular as he was in command of it, and the work it was called upon to do was much more dangerous and difficult than the task of the other sections. It demanded much greater leadership on the part of the man in charge. It is only fair and right to say that this section was undoubtedly the best, and deserved this distinction, and it was all through his zeal and energy that it was so good. The men would have followed him anywhere under any conditions. At 10.30 on the 23rd of November the attack started, and with four guns followed about 400 yards behind the last wave of infantry. For the sake of cooperation and liaison with the infantry we decided that your husband should stay all the time with the last infantry wave, while I followed behind with the section. Our first objective was a ridge on the left of Bourlon Wood, and just outside it, known as ‘100 Spur’, and our second [was] Bourlon Village, and the high ground above. All went well as far as the ridge, and the Brigade on our right, which attacked the wood, seemed [to be] going well. We were held up by machine guns at “100 Spur” (the Boche machine guns were very numerous, and he put up a very effective barrage with them), and your husband came back to help me get the guns into action to try and help the troops in the front to advance. I was hit in the thigh as we were doing this, and he turned to me and shouted “Stand back” as a farewell message, for of course in a show like that, when a man is wounded, no more notice can be taken of him by the people who are advancing. My last view of your husband was of him directing the guns’ fire, and encouraging his men, in [the] face of the deadly fire, and I think it is a picture of him of which you may be proud. On my way down to the dressing station a runner overtook me with a message from him to the C.O., so I know he was all right for, at any rate, half an hour [after] I got hit. I heard a rumour of his death at the dressing station [at] about five (I was hit about noon), but I kept on hoping against hope it was not true, till I saw his name in the Casualty List. I would like to tell you once more how very very dear to me has been the friendship of your husband. He came to us in August and I was appointed Subsection Officer under him almost at once. Before his arrival we were all suffering from a fit of trench slackness. I mean nobody took much interest in the work, and everybody was fed up and everything was too much trouble, mainly owing to our late C.O. (Major [???????]) who was enough to feed up anyone. Your husband, by his unbounded zeal, and tireless energy and keenness, made us see that things were worth doing well. It was through him, more than anyone else[,] that, when we went into action on the 23rd, we were a Company to be proud of, and our section was one of which I wish to be proud to my dying day. In August we were the slackest and so the rottenest Company possible, and the contrast and difference was [sic], I sincerely and firmly believe, due entirely to your husband. I, more than anyone else, knew him and appreciated him, situated as I was, and being entirely with him. He helped me in many ways, especially religiously – a more God-fearing and Christian man I never met. Please don’t think I have exaggerated in any particular in what I have written, in order to try and comfort you. Before God I mean every word I have said, and I feel that the writing of this letter is the least I can do for one who did so much for me and made me[,] at any rate[,] desire to be a better man.

The murderous, hand-to-hand fighting in and around the village of Bourlon continued on 24 and 25 November amid heavy rain and snow, and by the evening of 25 November, when the exhausted survivors of the 40th Division, including 121st Company, began to withdraw southwards and south-westwards, the Division had lost 172 officers and 3,191 ORs killed, wounded or missing and won 80 decorations for valour – but had only one intact Battalion left. Of Villiers’s Company, 21 officers and ORs were killed, wounded or missing. The entire British attack in the Bourlon area petered out on 27 November and on 30 November, after a massive bombardment, the Germans counter-attacked and regained control of the position, forcing the British to withdraw on 4 December to secure winter positions. But Field-Marshal Haig sent a message in which he said that he “personally wished all ranks of the 40th Division to be congratulated on their success”. Villiers was initially buried in the little cemetery at nearby Anneux, with a small white cross above his grave, but like Male, he now has no known grave and is commemorated on Panel 1 of the Cambrai Memorial, Louverval, north of the road that runs from Bapaume to Cambrai and about nine miles north-east of Bapaume. He, like several thousand other British and Germans whose corpses were piled up in and around Bourlon and Bourlon Wood, may well have been interred by the Germans in huge, unmarked mass graves that have never been located, let alone excavated.

Writing posthumously, President Warren described Villiers as “a man of many friends and solid ability, who grew steadily year by year in usefulness” and who “had before him the promise of a really valuable and probably highly honourable life”. A brief death notice that appeared in The Times on 4 December 1917 described him as “Christ’s faithful soldier and servant unto his life’s end”. One of the Staff Officers of his Division echoed the sentiments contained in the long letter cited above:

The General has paid a particular tribute to the work done by the machine-gunners, and that such praise is richly deserved by Villiers’s men is largely due to the infinite pains he took over their training, and the inspiring example he set them to the very end. His brother officers cannot speak too highly of his capacity as a leader, of his charm as a companion, and of all those splendid qualities of his which made him the leader of his mess and the idol of his men. He loved the men, and they loved him, and his invincible optimism carried him safely through those dark hours of danger and discomfort which set weaker men grumbling and despairing. It is no exaggeration to say that officers and men adored him.

On 17 December 1917, Villiers’s father wrote to President Warren: “Thank God he did not suffer. He was struck in the head by a bullet & death was instantaneous” – though here it should be noted that many Commanding Officers, when writing to close relatives of men killed in action, would write in such terms in order to spare the grieving relatives from additional anguish. Villiers’s CO, Major Sydney Guy Davey (1893–1918), who had known him for only three weeks and would himself be killed in action while serving with the Machine Gun Corps on 25 March 1918, wrote that “as an officer, no words are too good for him” as he was “so extremely good and efficient”. Another correspondent wrote:

No-one more willingly gave up a life of noble promise to a call which he felt was sacred. He thought that in the war there was an inspiration to draw men from “poverty of outlook” (his own expression), and to direct all their energies into the maintenance of a supremely righteous cause. With all his radiant enjoyment of this world, and his artistic temperament, which found fit expression in a lovely voice, as well as in painting and spirited writing, full of ease, force and grace, the vision of the highest never left him. The spiritual element in his nature was by far the strongest, and the life of Christ was always before him as the one great example. He was happy in the circumstances of his death. For he had a peculiar love of France, and the spirit of comradeship in the Army realized his ideal of the brotherhood of man, as a life of sacrifice and adventure appealed to the truest instincts of his being.

But in the memoir that he composed in 1918, Graham left a much lengthier appreciation of his dead brother-in-law’s brief life and character:

There was surely no more delightful companion than he; he was so widely read, he had such an excellent memory, his conversation was always stimulating and suggestive, his interest in the social and political questions of the day never flagged. […] Whatever was vulgar and base and stupid his soul abhorred, but he did not shun contemplation of the sordid facts of existence, facing them with an invincible optimism that proved his faith in the ultimate prevalence of good. His was, indeed, that purity of heart which blesses its possessor with a vision of the Divine in everything. He could talk about religion without self-consciousness, or that assumed air of solemnity which is commonly reserved for such discussions; he had none of Dr. Arnold’s “manner of awful reverence when speaking of the Scriptures”, and would not have denied to God the sense of humour and the gift of laughter [of] which mortal men almost unanimously claim the monopoly.

Furthermore, Graham continued: