Fact file:

Matriculated: 1902

Born: 19 August 1884

Died: 1 December 1917

Regiment: Grenadier Guards

Grave/Memorial: Fins New British Cemetery: IV.B.9.

Family background

b. 19 August 1884 at Vectis Lodge, 37 Augustus Road, Edgbaston, Worcestershire, as the eldest child of Herbert Chamberlain (1846–1904) and Lilian Seymour Chamberlain (née Williams) (b. c.1864 in Canada, d. 1949) (m. 1883). He was actually one of twins, the other of whom died on 15 May 1885; he also had two sisters. After his father’s death, his mother became Mrs Alfred Cole after her marriage in 1907 to Alfred Clayton Cole (1854–1920).

In May 1885 the family was still living at 37 Augustus Road, Edgbaston, and at the time of the 1891 Census it was living (with eight servants) at Penryn, Somerset Road, Edgbaston, a house which, by the time of the 1901 Census, was occupied by Edward Nettlefold and his family (q.v.). At some point, Norman’s mother was living at Sherfield Hall, Sherfield on Loddon, near Basingstoke, Hampshire (where eight servants were employed at the time of the 1911 Census). By the time of the 1911 Census Norman had his own home at 1 Oakley Square, Camden, London NW1 (two boarders and three servants), besides a residence in Birmingham (q.v.).

Norman Gwynne Chamberlain, aged 12

(From Neville Chamberlain, Norman Chamberlain: A Memoir, London, John Murray, 1923; courtesy of CRL)

In 1912, Norman’s stepfather bought West Woodhay House, Newbury, Berkshire, a handsome mansion built in 1635 according to a design attributed to Inigo Jones (1573–1652), which had become the property of the Cole family in 1880. Norman’s mother continued to live there after the death of her son and second husband.

Parents and antecedentsNorman Gwynne was the great-grandson of the cordwainer Joseph Chamberlain [I] (1752–1837) and the grandson of the ironmonger, shoemaker, manufacturer and businessman Joseph Chamberlain [II] (1796–1874). Consequently, he was the nephew of the more famous Independent Unionist politician Joseph Chamberlain [III] (1836–1914) (cf. G.P. Steer and W.L. Vince). In 1819 Norman Gwynne’s great-aunt, Martha Chamberlain (1794–1866), the sister of Joseph Chamberlain [II], married the businessman John Sutton Nettlefold (1792–1866), who in 1826 founded a water-powered screw-making workshop in Sunbury-on-Thames, Surrey, an operation which he transferred to Baskerville Place, off Broad Street, Birmingham, in 1834. In 1848, John Sutton Nettlefold’s oldest child, Martha Sanderson Nettlefold (c.1822–1905), married Charles Steer (1824–58), the father of Edward Steer and thus Steer’s paternal grandfather, a union which meant that Steer and Norman Chamberlain were distant cousins.

In 1854, John Sutton Nettlefold bought a licence which permitted him to use an American machine in Britain that was capable of producing more efficient, pointed screws. The cost of this innovation was £30,000, but as Joseph Chamberlain [II] provided a third of the sum as an investment, the two brothers-in-law decided to go into business together, operating under the name of Nettlefold & Chamberlain, and to set up a new factory in Heath Street, Smethwick (cf. Steer). They also decided to run the business with the help of two family members, and so in 1854 Joseph Chamberlain [III], aged 18, moved from London to Birmingham to work for his uncle. Before retiring from the family firm in 1874 in order to devote himself full-time to politics in the City of Birmingham and nationally, Joseph Chamberlain [III], in partnership with his cousin, the mechanical engineer Joseph Nettlefold (1827–81), the fourth child of John Sutton Nettlefold, played a major part in bringing about the commercial success of Nettlefold & Chamberlain. By 1876 the Company owned 2,000 machines that were producing half a million screws per week for export all over the world, and in 1880 it became a limited liability company. In 1902 it combined with Guest, Keen and Co. to become Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds (GKN).

Herbert Chamberlain, Norman’s father, was the sixth of Joseph Chamberlain [II]’s nine children and younger than his brother Joseph Chamberlain [III] by ten years. Herbert is sometimes described on Censuses as a “retired screw manufacturer”, but in fact he had a range of business interests. He chaired the Central Insurance Company in Birmingham, and from 1900 until four months before his death in May 1904 at 2 Ennismore Gardens, London SW7, he was the Chairman of Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA), a firm which had been set up in 1861 to manufacture rifles and would later, after Herbert’s death, diversify very successfully into the manufacture of bicycles, motorcycles, and cars. Unlike his older brother Joseph, Herbert had “little taste for public affairs”, but he was a Justice of the Peace and a member of Birmingham’s Licensing Committee. According to Neville Chamberlain, Herbert’s political recessiveness derived from indifferent health and chronic migraines:

At such times he was unable to do anything but lie in a darkened room, and the continual attacks of pain gradually told upon his spirits and vitality, until in 1904 he died without apparently having exercised any very great influence upon his son’s character or inclinations.

Norman’s mother Lilian was the daughter of Colonel A.T. Williams, MP, a successful Canadian businessman and farmer, and a well-known political figure in Canada who was a Conservative whip in the Ontario legislature. Her second husband, Alfred Clayton Cole, began his professional life as a barrister but became a successful banker and a Director of the Bank of England. From 1911 to 1913 he was its Governor.

Norman was also the cousin of Austen Chamberlain (1863–1937) and Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940), the respective sons of Joseph Chamberlain’s [II] marriages to Harriet Kenrick (1838–63) and her cousin Florence Kenrick (1847–75), both of whom died in childbirth. Norman was particularly close to Austen and Neville, and although they occasionally disagreed with each other, “they came to feel for each other as brothers”, especially in the years 1911–14, when Norman and Neville worked closely together on Birmingham City Council.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Walter Seymour (twin brother who died in infancy) (1884–5);

(2) Dorothy (“Doffie”) (1887–1911);

(3) (Vivien) Enid (1897–1971); later Durand after her marriage in 1924 to Captain (later Colonel (Hon. Brigadier) Sir) Alan Algernon Marion Durand, MC, RHA (1893–1971), 3rd Baronet (from 4 March 1955); one daughter.

After her first marriage was dissolved in 1936, (Vivien) Enid married (the same year) Abraham Bernard Okert Schongevel (b. 1885, d. after 1948, probably in South Africa). Alan Algernon Durand later married (1944) Evelyn Sherbrooke Crane (later JP, CBE) (1888–1984), the widow of the businessman and Conservative politician Sir Stanley Tubbs, JP (1871–1941; from 1929 3rd Baronet), who was prominent in the public life of Gloucestershire and MP for Stroud from 1922 to 1923.

Norman Gwynne Chamberlain (the photo was probably taken when he was at Eton in c.1900/01 and aged 16 or 17)

(From Neville Chamberlain, Norman Chamberlain: A Memoir, London, John Murray, 1923

Education

Although a delicate child who suffered from a weak heart and gastric catarrh, Norman attended Mr Dunn’s Preparatory School at Ludgrove, Cockfosters, New Barnet, Hertfordshire, from 1893 to 1898 (cf. P.V. Heath). The school, which became Ludgrove School when it moved to Wixenford, Wokingham, Berkshire, in 1937, had been founded in 1892 by the noted footballer Arthur Dunn (1860–1902), who had a reputation for having “great sympathy with and understanding of boys” and so, despite Norman’s weak physical condition, he was able to make his time at school a happy one. Norman then attended Eton College as an Oppidan from 1898 to 1902, having declined to take up the scholarship that was offered him so that it could be awarded to others who were less able to afford the fees. He rose to the rank of Colour Sergeant in the Eton Rifle Volunteer Corps, and not long before he left, during the College’s celebrations on 4 June 1902, he rowed in one of three Upper Boats, the Monarch, together with John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), the future economist who would disprove classical laissez-faire economics, and alongside E.H.L. Southwell, who was coxing the Victory, the second of the Upper Boats. Norman did not, however, make it to the Sixth Form at Eton and Neville Chamberlain records that he “had not been altogether happy” there, as

both his tastes and his ways of thought were somewhat different from those of the average boy, and he was perhaps unfortunate in the fact that the set with whom he was brought into contact had little sympathy with the intellectual and literary pursuits which attracted him.

After leaving Eton, Norman toured the Loire Valley from July to October 1902. He then matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 20 October 1902, having been exempted from Responsions. At the end of his first term, he was elected to a Demyship alongside A.H. Villiers, who became a good friend and was killed in action ten days before him during the Battle of Cambrai. Norman Gwynne took the First Public Examination in Hilary Term 1902 and the Preliminary Examination in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1903. He then spent much of the long vacation of 1903 with the family of an officer in the Prussian Guards on the Baltic coast, where he learnt German and developed a respect for the German military, writing to his mother:

What awfully nice people these German officers are! They are all so awfully clever and know what they are talking about. At the same time they have lovely manners and are so smart and so awfully kind. I don’t wonder the German army is such a good one.

Norman rose to a certain prominence at Oxford, but that rise did not begin until spring 1904, when, because he was in accord with the controversial beliefs of his much admired Uncle Joe, he helped to set up the Oxford University Tariff Reform League, an independent, non-partisan body whose aim was to make propaganda for the Preferentialist cause and, if possible, “capture the Union” for the controversial idea that the British Empire should be turned into “a self-sustaining economic unit, protected by high duties on goods imported from outside”. In this he was supported by friends from Eton and Magdalen such as the Hon. Henry Lygon (1884–1936; Magdalen 1902–6; Secretary of the Canning Club 1905–6; President of the Union 1906); Hugh Douglas Peregrine Francis (later Colonel, MC, TD) (1883–1957; Magdalen 1901–5; member of the Rupert Society, the Conservative Club and Leander), mentioned in dispatches (London Gazette, no. 30,169, 6 July 1917, p. 6,657); and E.V.D. Birchall. He also received support from a good number of Senior Members of the University from other colleges, such as Mr William Temple of Queen’s College (q.v.), Mr R.H. O’Neill of New College, and Lord Wolmer of University College. The League’s main concerns were to end “Cobrigadenism”, i.e. the free trade advocated by the Manchester School, and to compensate for the allegedly ruinous state of British agriculture by forging a closer relationship with the Colonies in order to ensure that they produced the bulk of Britain’s food. The League soon had over 700 members, and its first meeting, when the speaker was the Canadian-born Conservative politician Sir Horatio Gilbert George Parker (1862–1932; MP for Gravesend 1900–18), took place on 1 May 1904. Parker confidently proclaimed: “The day [has] gone by when the policy of the open door [is] the best for the country. The time [has] come when it should be the policy of selfishness for the Empire and justice to the rest of the world.”

On 4 December 1905 the Conservative politician Arthur Balfour (1848–1930), who had been Prime Minister since 11 July 1902, resigned, hoping that the dissension among the Liberals over the question of Home Rule would prevent them from forming a government. But he was wrong since Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836–1908), the leader of the Liberals since 1899 who some political commentators came to view as “Britain’s first, and only, radical Prime Minister”, was able to form a government, call an election, and achieve the landslide victory of 1906.

Four days later, thanks to Norman’s family connections, his own enthusiastic hard work and organizational skills as Secretary of the Oxford League, his Uncle Joseph, who had been one the co-founders of the Liberal Unionist Party in 1886 and had resigned from the Coalition Cabinet in 1903 to campaign for tariff reform, came to Oxford to address an audience of over 2,000 people in a packed and highly charged town hall. Most of Oxford’s colleges sent a Senior Member to the meeting, including several established dignitaries, and Queen’s College sent as its representative the young William Temple (1881–1944), now a Senior Member by virtue of his recent appointment there as Fellow and Lecturer in Philosophy (1904–10), and as such not yet ordained (1909); later in his life he would become Archbishop of Canterbury (1942–44) and a committed Christian Socialist. President Warren chaired the meeting, accommodated Mr Chamberlain in the Lodgings overnight, and probably, as Oxford’s unofficial correspondent, authored the 7,000-word report that appeared in The Times on 9 December. Using such unquestioned ideas as “the British race” and in the full belief that the British Empire was “the most envied […], the most spacious, the most varied, the most promising [Empire] that the world has ever seen”, Joseph Chamberlain, whilst conceding that the Colonies were “not prepared at this moment for a political federation”, argued passionately that the “Imperial Constitution” as it now existed, being based on such “antiquated and out of date” doctrines as Free Trade, was no longer “sufficient for the purpose of securing an effective exercise of combined forces”. Consequently, he concluded, in order to ensure that “this evolutionary progress” was completed and that the Empire became “the most powerful instrument for beneficially influencing the destinies of mankind”, it needed “a treaty of commercial union” with the Colonies that was based on “the principle of preference and reciprocity”.

Two months later Campbell-Bannerman’s reforming Liberals enjoyed a massive victory at the polls (cf. G.M.R. Turbutt), but the enthusiastic belief in a divinely ordained and sanctioned Empire that was so audible in Oxford’s Town Hall on 8 December 1905 helps to explain why Norman and so many of his contemporaries would rush to join up and fight just under nine years later.

In Trinity Term 1906 Norman was awarded a disappointing 2nd in Modern History (Honours), and he took his BA on 31 October 1906. President Warren later recorded:

His health during part of his residence was not quite robust, and his plans were somewhat uncertain, and for some time he did not make much mark, though he was greatly liked by all who knew him and created an indefinable impression of undeveloped capacity.

On 8 May 1918, i.e. just over four months after his death in action, Warren, who thought extremely well of Norman, developed his thoughts about him in another letter and said that although “Norman’s health was not quite settled” during his time at Oxford, he had perceived in him a certain lack of “the worldly ambition which might have been expected”, adding, however, that nevertheless “I think he had a good deal of unworldly ambition, a great deal of kindness and gentleness and love for his fellow-men and desire to serve them.” He then added:

[Norman] was […] older in some ways than his contemporaries, and seemed to have interests of a different kind, but here, at any rate, whatever he may have done at Eton[,] he enjoyed life with his contemporaries.

In support of Warren’s claim, Neville Chamberlain, too, cites a letter in which Norman welcomed the greater “scope for originality and free action and thought” that he found at Oxford, and expressed his new-found “relief to be free and do what one pleases, and not to have to think whether this or that is proper or fashionable”.

Warren also said: “I have been looking[,] for instance[,] at a very happy photograph of him in a group of the ‘Torpid’, or second College Boat. He rowed a great deal while he was here, and successfully.” Though here it has to be said that one of Magdalen’s archivists was unable to find Chamberlain’s name on any rowing photos in Magdalen’s archives, but only on the Rupert Society photo reproduced below. It is true that in mid-February 1905 – not the warmest time of the year, especially for someone of delicate health – Chamberlain rowed at number 2 in Magdalen’s 1st Torpid, alongside A.H. Huth, J.L. Johnston and R.P. Stanhope, and it is true that Magdalen’s Captain of Boats later wrote of his performance: “[No. 2] was heavy but did not use his weight. Never got a good grip of the water over the stretcher.” But that is Chamberlain’s only mention in the Secretary’s Book of the MCBC during his years at Magdalen.

Norman Chamberlain (taken from a group photo of Magdalen undergraduates in the Rupert Society, c.1903/04, aged about 19 or 20)

(Courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford)

After leaving Oxford, Norman, who was unable to decide upon a career at first, resolved to emulate his father by seeing something of the world before settling down. So in autumn 1906 he joined a party of distinguished friends who were going to the West Indies and thence to Canada. After this, he and his Magdalen friend John Murray (1884–1967), a scion of the distinguished publishing house founded in 1768, toured the Far East (including China, Japan, Burma, India and Ceylon) and returned to Britain in May 1907. In Jamaica, Norman was struck by the beauty of the landscape and the growing sense of enterprise. But he was particularly impressed by the speed, grace, stamina and “conscious self-assurance” of the women on their way to market, “all carrying whatever they may have on their heads. It’s a wonderful sight, they go [at] such a pace and balance anything from a bottle to an enormous wicker basket full of great bunches of bananas on their heads”. Canada was a surprise, too, because of its people’s hospitality and confident sense of political purpose:

Canada is above all for Canada; then, on a higher plane, for the Empire. She has no great loyalty for England, whose policy and whose citizens have shown up so badly in Canadian affairs. The word isn’t “loyalty”: it’s “patriotism”. Everyone in Canada calls himself an Imperialist. They one and all admire Uncle Joe tremendously; they one and all desire to make the Empire strong and great and useful. Their idea of a united Empire means true co-partnership – not England as boss, England who to her is slow, being left behind, conservative. This is largely a result of her immense, unbounded confidence in herself, her resources and potentialities. Her wonderful this and wonderful that were dinned into my ears. She is the coming nation. When they say “the nineteenth century belonged to the U.S.A., the twentieth belongs to Canada”, they mean it literally. They’re sure they can be self-contained and that their trade is going to be unparalleled.

He then spent about seven weeks in India and Ceylon, after which he confessed to being “madly keen” on the sub-continent once his eyes had been opened to his own “gross ignorance” about its ethnic diversity, its need of technical education and industrialization, and the dire effects of the caste system. After a day or so in March 1907, when he was able to admire the Legation in Peking (now Beijing) and the immensely impressive Summer Palace to the north-west of the city, Norman and his companions travelled on a slow, cold and very uncomfortable train to view Port Arthur, the ice-free deep water port just beyond the boundary between China and Manchuria which the Japanese had wrested from the Russians on 2 January 1905 after a six-month siege during the Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904–5 September 1905). During this conflict, weapons were tried out that would be standard a decade later and reminders of the conflict were still very prominent, especially around 203-Metre Hill, where the worst fighting had taken place. Norman described the whole experience as “immensely interesting and almost terrifying. One realises the wonderful heroism of the Japs, their patience and determination. One also realises the real actual horror and destructiveness of modern war”. After that, Norman and John Murray crossed to Japan to visit the principal sights, and towards the end of April 1907 the two men sailed to Canada, spent three weeks visiting New York, Boston and Washington, and then “returned to England, to settle down to the serious business of life”. But on board ship, in March 1907, Norman wrote a letter indicating that he still had not decided upon his future career, though his inclination was increasingly turning towards politics:

not mere party politics and getting into the House, but studying social questions at home thoroughly, working at theoretical stuff like political economy, and studying foreign questions like China and the Balkans etc. And above all, Imperial questions, of organisation of colonial opinions and movements and facts.

Norman could make the latter claim with some confidence since his year of travelling had taught him several very important lessons. First, that the new national consciousness of the Colonies completely undermined “the common idea” that the Empire consisted of “a Mother Country surrounded by a group of admiring and affectionate children”; second, that Britain’s indifference to and neglect of the Colonies had speeded up this process of emancipation and maturation; and third, that the Colonies have Britain’s “successes and failures to guide them in those social experiments for which they are so much better placed”. But fourth, and perhaps most importantly, he came to the conclusion that far from being poor relations, the “new-fledged nations” were in many respects ahead of Britain:

they are comparatively free of the prejudices, parochialism and complacency which the past has bequeathed to us; they are not faced by our over-crowded, ill-built cities, with their accompaniment of drunkenness and disease; accumulated wealth does not crowd out the enthusiasm and “go” of their more efficient citizens; accumulated poverty does not hang like a millstone round the neck of the reformed.

Not long after his return, and to the chagrin of many “well-meaning but ill-informed patriots”, he published an article to this effect entitled ‘Australian Tariff and Colonial Nationalism’ and he provoked a similar reaction when, in 1908, he expressed the same views in a speech at Cirencester.

Professional life

But the direction in which Norman’s thoughts about his future career were moving began to change. The Reverend Canon William Hartley Carnegie (1859–1936; Magdalen 1878–83), who had been the Rector of St Philip’s Church, Birmingham, since 1903 and remained the incumbent there after St Philip’s had become the Cathedral Church of Birmingham in 1905, invited Norman and some of his friends in 1907 to come to Birmingham and “engage in social and political affairs so as to equip themselves with a first-hand knowledge of such subjects from the working man’s point of view”.

There was a certain proleptic irony about this invitation since in 1912 Canon Carnegie would move to the Diocese of London, where he became a Canon of Westminster and the Rector of St Margaret’s, Westminster. And then, in 1916, the year when he was appointed Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons, Canon Carnegie, a widower since 1902 and the father of five daughters, became the second husband of Joseph Chamberlain [III]’s third wife, the American-born Mary Endicott Chamberlain (1889–1940), whom he had first met in Birmingham in c.1907. Thus, Carnegie became associated with the Chamberlain family by marriage.

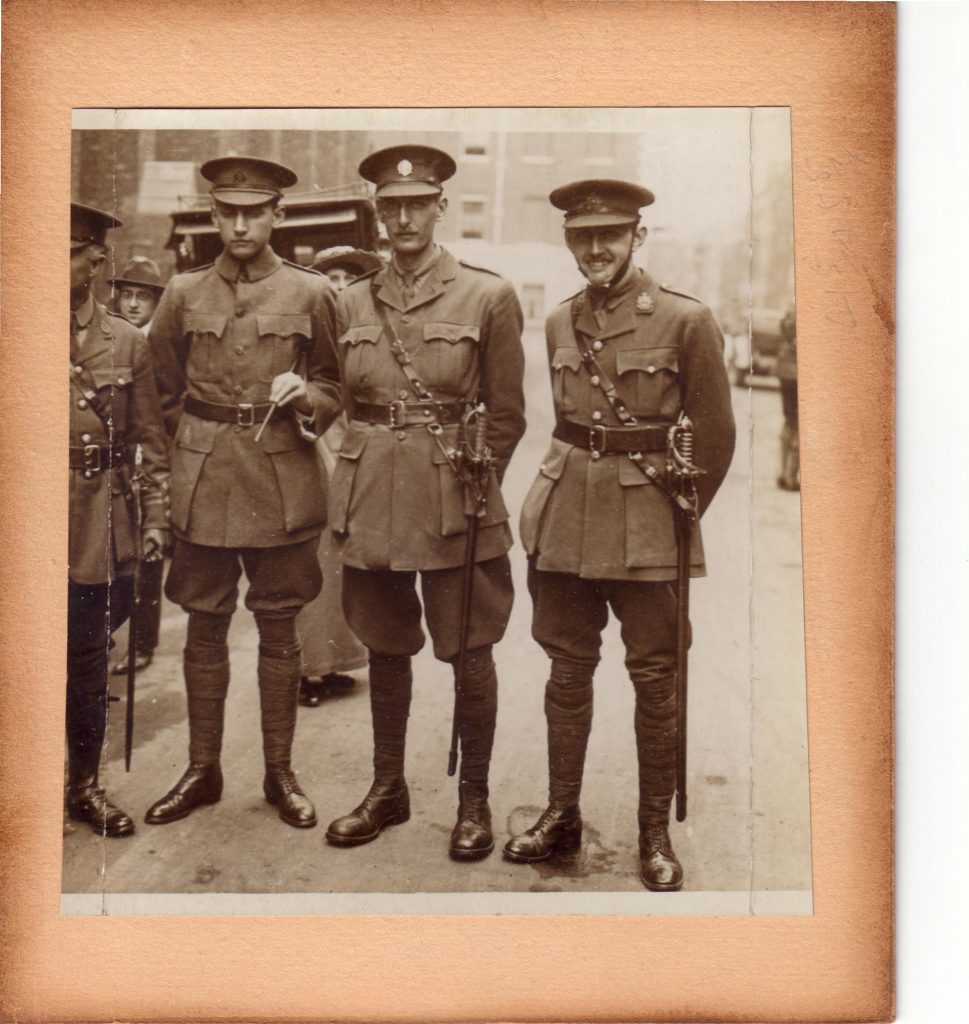

The marriage (3 August 1916) between the Revd Canon William Hartley Carnegie (1859–1936) and Mary Endicott Chamberlain (1889–1940). Norman Chamberlain is in military uniform to the left of the picture and in the front row.

After a period of exploratory preparation, a group of four young men, including Norman and his Magdalen friend Birchall, who also had a developed social conscience, settled at Calthorpe Cottage, St James’s Road, Edgbaston, where its members “started to work in real earnest”. Norman followed Canon Carnegie’s pioneering work in Birmingham and built on the experience that he had acquired towards the end of his time at Oxford of accompanying boys from London’s East End on a summer camp in Norfolk. Consequently, he was particularly concerned from the outset with the situation of the uncared-for and semi-destitute boys and youths who, “lounging about the two great stations at Snow Hill and New Street, or selling papers in the city centre, got no help from any voluntary agency”. The lads were unskilled and badly nourished, and in continual danger of getting into trouble with the police and being sent to prison for “loafing” by magistrates who were less kindly disposed than Balthasar Foster (1868–1952; Magdalen 1888–1890, BA Pass Degree; Lord Ilkeston from 1913; Stipendiary Magistrate of Birmingham 1910–1950). An Oxford friend, the Quaker Thomas Edmund Harvey (1873–1955; Christ Church 1893–7; later a prominent Liberal politician, social reformer, anti-war campaigner and conscientious objector), would later speak with admiration of Norman’s unselfconscious ability to stop and converse with the boys who were hanging around the stations “in the most natural way, as though they were old friends”.

In the context of this work, Norman defended the street lads when they appeared in Juvenile Police Courts and helped organize their probationary work when they were convicted, especially for the first time. Besides this he set up and ran a Working Lads Club for them in Dalton Street, Birmingham, which ran between the City’s Crown Court and Magistrates Court, and lasted for 18 months to two years. He kept personal records of every boy, interested himself in their domestic circumstances, and took them on weekend and summer camps in the country or by the seaside. He was also involved in the Street Boys Union in Ryland Street, Birmingham. In due course he gave evidence to the Home Office Committee that supervised the working and effectiveness of the Probation of Offenders Act of August 1907, which stressed the restitution rather than the punishment of young offenders. But Norman’s work was not driven just by compassion, and when Neville Chamberlain was drafting a memoir of Norman in July 1918, he wrote:

The motive of all his work was his clear perception of the absolute necessity of building up the nation more carefully, more surely, and more intelligently, so that the City and the county might have a perennial supply of strong, free, efficient and happy citizens. He recognised that this end required better conditions & wiser treatment from infancy to early manhood, throughout the period of growth and development.

So as a result of his early experience, Norman soon realized that “we have not yet really sufficient information on the problem, or, to put it more correctly, the information exists, but is so scattered that it requires to be brought together and co-ordinated”, and so, towards the end of 1908 at the age of 24, he put together an extensive, succinct, and very impressive memorandum which he then read out on 20 January 1909 at the meeting of the Association of the Midland Local Authorities that took place in Smethwick. He spoke with great authority and assurance and without any dewy-eyed educational idealism, and in his speech he analysed the complex and often trivial reasons for the boys’ seemingly hopeless plight, especially when they were approaching manhood. He also identified gaps in the existing care system, commended the positive steps being taken by teachers and head teachers to help remedy the problem, and recommended practical ways of helping the boys which involved their parents, potential employers, the police, the social services (such as they were), the Education Committees, the national system of Employment Exchanges (which would shortly come into being thanks to the Labour Exchanges Act of 1908), and charitable and philanthropic bodies. But in his view, given the complexity of the problem, two things were of central importance: “Employment Exchanges for boys” and “an After-care Committee at each group of schools”. He explained:

Composed of school teachers, heads of clubs, and persons acquainted with industrial conditions in the neighbourhood, the committee would interview boys, and probably their parents, a few months before they leave school, discuss the future, and, where necessary, give advice and warning. When the time for finding a job comes, the Employment Exchange would be brought into play, and there would be a wide choice from which to select a situation suited to the boy’s powers and tastes. The manufacturer could then be sure that his boys had made a carefully considered choice instead of a haphazard one.

But as Neville’s memoir implies, Norman could justifiably be described as a “social Imperialist” who believed in the necessity of improving the moral character and physical stamina of Birmingham’s destitute youth so that they were fit enough to serve, and if necessary defend, the Empire, and his memorandum of 1909 concluded thus: “[In achieving our end,] we shall then be able to look forward to an unskilled class whose physique and whose moral [sic] is as little injured by their life’s work as those of their more fortunate fellow-citizens.”

But according to Neville Chamberlain, some of Norman’s friends thought right from the start that his concern for under-privileged and destitute individuals was causing him to “lose his grip on the larger political questions which should occupy the mind of a young man destined for a parliamentary career”. Norman shared this concern, as can be seen from his letter of 17 August 1908 to Birchall from a summer camp, in which he spoke of his persistent mental “turmoil” over his future that was causing him at times to become “more uncertain than ever and very miserable”. But, he concluded:

One thing I feel sure of now: nothing will make me give up the study of the social and industrial questions that Brum [diminutive of the dialect name for Birmingham: Brummagem] has introduced me to, or working to put them right. The personal knowledge we’ve got there has burned into me a definite wish to do my best in that way, and nothing – much less the advice of people in London – will stop me doing it.

So whilst he wished “to be a public man” and decided to apply for a job with the London County Council that involved living at Toynbee Hall (q.v.) “which is a great centre of activity”, Norman did not wish to leave his “most valuable position in Brum”, his “point d’appui” that put him

in touch with a whole society as well as with a lot of representative institutions and civil reformers, also with a lot of the working classes, and in such a way that I can find out their views and get to learn still better their difficulties and complaints and blessings, etc.

In autumn 1908 Norman came into residence at Toynbee Hall, in London’s East End, where his friend Thomas Edmund Harvey was already active (resident from 1900; Deputy Warden 1904–6; Warden 1906–11). Toynbee Hall, the first university-affiliated institution of the worldwide Settlement Movement, had been founded in Commercial Street in 1884 by Canon Samuel Barnett (1844–1913) to enable young men and women from rich and privileged backgrounds to spend time working with Whitechapel’s poor and underprivileged before embarking on their chosen career (see C.B.M. Hodgson).

Samuel Barnett (1844–1913)

(From Samuel Augustus Barnett; Dame Henrietta Octavia Weston Barnett by Elliott & Fry; given by Terence Pepper, 1976; NPG x696; © National Portrait Gallery, London)

The idea was that their experience in the East End would encourage and help them to initiate much-needed social reforms. Two people on whom this concept had the desired effect were Clement Attlee (1883–1967), who rose to prominence in the Labour Party and became Britain’s post-war Prime Minister from 1945 to 1951, and William Beveridge (1879–1963), the architect of the Labour Exchanges Act and, after World War Two, Britain’s welfare state. During his time at Toynbee Hall Norman “shared in the general life and interests of the settlement in Whitechapel”, coming into contact there with all the varied activities affecting local government, school management, the running of Working Boys Clubs, especially the one in Limehouse, and the growing Boy Scout movement, which were represented there by the different residents and associates. He was also co-opted onto the Central (Unemployed) Body which, under the terms of the Unemployed Workmen Act of 1905, was trying to cope with the large number of unemployed in the London area. He also joined Harvey on the Employment Exchanges Committee which, under Beveridge’s tutelage, was trying to set up a co-ordinated system of Labour Exchanges, and served on both the Classification Committee (which co-ordinated the work of local distress committees) and the Works Committee (which was concerned to provide employment in London). Finally, he became a firm supporter of the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA; founded in 1903 by Albert Mansbridge (1876–1952), whom Norman got to know), and he served on the Education Committee of the London County Council. So when the report of the Poor Law Commission was issued in early 1909, Norman collaborated with other residents of Toynbee Hall to produce a small book that summarized the report’s main features in order to mobilize public opinion.

In autumn 1909, encouraged by friends and with a general election imminent, Norman decided to stand as a Unionist candidate, and on 8 October 1909 he was selected to contest the Camborne Division of Cornwall for the election of January–February 1910. But he knew that there was no chance of his winning the seat, since the constituency had a long tradition of Liberal Radicalism and no tradition of Unionism, and despite a spirited campaign in which he was strongly supported by his Uncle Joe and which earned him much respect and popularity, he lost to the existing Liberal MP, Albert Edward Dunn (1864–1937), by 2,587 to 5,027 votes. Although Dunn stood down at the election of December 1910, Norman decided not to contest Camborne for a second time since, by the end of the first election, he had decided to give up national politics for the time being and acquire more practical experience by returning to Birmingham’s social and municipal issues such as housing reform, the development of juvenile advisory committees, and the work of the WEA. So on his return to Birmingham he became Secretary of the West Birmingham branch of the City Aid Society, served on the committee of the Housing Reform Association and the committee of the Working Boys’ Homes, associated himself with the work of the Middlemore Homes in St Luke’s Street, a charity that had been established in 1875 by Dr John Throgmorton Middlemore (1844–1924) for the purpose of resettling needy children in Canada, and began taking a great interest in the work of Birmingham’s Children’s Court at the city’s Victoria Courts. On 1 November 1909 he was elected as the Liberal Unionist Councillor for the old St Thomas’s Ward of Birmingham after a “contest that had been waged with some warmth” against the Liberal-Labour and Progressive Candidate, William Arthur Dalley (later MBE; 1872–1954), a native of Birmingham who was a trade unionist and the Manager of a Labour Exchange.

In spring 1910 Norman took a recuperative holiday on the Riviera, but on his return, in May, he loaned eight of his boys enough money to buy new clothes, emigrate to Canada, and “commence life afresh”. The scheme was a daring one and Norman explained what had motivated him in a long letter:

I feel as if [the boys] had just escaped from some ogre’s castle where their character and souls were being tortured and persecuted and where cruel and inexorable law took the place of their own wills and their own merits and dragged them very slowly through a dismal, meaningless, artificial life. It does make me realise how enormously lucky people are who don’t have to go through that sort of thing as well as the ordinary troubles of life. What appals me so is the hopeless, lifeless sort of way that these poor kids take it all for granted and get used to it, and hardly try to escape because experience has told them there’s seldom any getting away. In this the casual and unskilled working class is quite different to the skilled artisan and trade unionist, who can and does rise and who can keep at a decent level of comfort.

In August Norman went to Canada for several weeks to see how the lads were getting on and was delighted to find them all doing well and settling into their new surroundings, mainly on farms in Ontario. So he repeated the scheme in subsequent years, and a Mr Hampton, who was one of Norman’s “most valued assistants in this work” later wrote:

“The majority of these [lads] proved successful and in due course paid back to Mr. Chamberlain either all or the greater part of the money advanced to them. Mr. Chamberlain not only kept in touch with these youths, but actually visited Canada on three consecutive summers and looked up every one of them in turn. No wonder they made good with his ceaseless energy behind them!”

Throughout 1910, Norman became an increasingly prominent member of Birmingham City Council, and as he was increasingly regarded as “an authority on all matters of education, employment, and the general bringing up of young people”, he was appointed to the City’s Parks and Education Committee. Here he pressed for the raising of the school-leaving age to 15, a subject on which, in February 1911, he gave a lecture in which he set out the advantages of such a move “with a wonderful variety and wealth of argument” and which Neville Chamberlain included in his memorial book as an appendix. Moreover, having joined the Open Spaces Association soon after settling in Birmingham and become its “mainspring”, he was an ideal candidate for the City’s Parks Committee, i.e. the body which looked after the City’s acquisition and improvement of open spaces. Neville Chamberlain notes that the ideas that he propounded on this particular committee “were so far in advance of the practice of the time that he found it by no means easy to get his own way”, and recalls that “there were numerous differences of opinion in the Committee on important points of policy”.

In June, July and August 1910, i.e. just before his first visit to Canada, Norman initiated a system of organized games for girls and boys – ball games, skipping, hopscotch and ring games – in “seven open spaces, situated in the more closely populated parts of [Birmingham]” and “at the close of the experiment” he asked the organizers – seven men and seven women – to each write a report on their work. Then, when the scheme was repeated in summer 1911, he edited a little book on the subject (see the Bibliography below) in which he included the 14. He also met half the cost of replacing the untrained volunteers of 1910 by experienced and specially trained teachers who could be relied upon to arrive at their place of work at definite times and with absolute regularity. Norman contributed a three-page introduction to the publication in which he summarized as follows the advantages which his scheme had over the preceding status quo:

A large number of the [participating] children were not within easy reach of any open space; while, for all, the customary playground was the court, the street, and the canal bank. In any case, the use of the public parks and recreation grounds was so hedged in and limited by rules and regulations, by ill-placed shrubberies and flower beds, and by officials of uncertain sympathies, that the children preferred to stay away. […] The absence of any legal means of outdoor recreation during the week gave the working girls and boys no alternatives but to hang about the street corners, jostle up and down main thoroughfares, play football in the street, spend their spare time in coffee-houses or in “boozers”, and get into loafing and dangerous ways generally.

In 1912, the Parks Committee of the City Council assumed responsibility for the scheme and provided half the necessary funds, and by 1914 the number of available open spaces had risen to 25. In 1910, too, Norman persuaded the philanthropic Cadbury family to offer a five-acre field at the corner of Alcester Road and Greensbridge Road for use, free of charge, as an open-air school. The Cadburys also donated about £400 worth of simple buildings and equipment to the school, which was intended for debilitated and backward children as “a sort of half-way house between the ordinary elementary school and those for feeble-minded and defective children”.

Given all of the above, it came as no surprise when, in autumn 1910, the Board of Trade invited Norman to chair the newly formed Juvenile Advisory Committee to the Labour Exchange. Acting in this capacity, he and his friend Arthur (later Sir Arthur) Steel-Maitland (1st Baronet) (1876–1935), a rising politician who became the first Chairman of the Conservative Party (1911–16) and MP for Birmingham East (1911–16) and Birmingham Erdington (1918–29), were able to devote much time and effort to drafting a city-wide scheme for the “after-care” of school-leavers – the first of its kind in the country to be recognized by the Board of Trade under the Act then in force. In devising this scheme, Norman was guided by two convictions. First, that children were in the greatest danger of going down the wrong road when they left school, and second, that every child should enjoy the sympathy and guidance of some qualified helper from that critical juncture “until the day when they should be fairly embarked on a career, fit in body and mind, trained to their craft, and yet provided with interests sufficient to occupy their leisure”. Norman’s “after-care” scheme was overseen by a system of Juvenile Employment Bureaux and about 100 School Care Committees, and these were monitored in turn by a Central Care Committee, the first of its kind in Britain, of which Norman was the Chairman and to which he left “a considerable library, probably the most complete in the country[,] on juvenile welfares, for the use of members of Care Committees”. One of his closest co-workers would later record in an obituary that Norman’s concern with the youngsters was so great that he kept a “personal record of every boy and interested himself in their domestic circumstances”. The scheme proved so successful that between 1911, when it got off the ground, and August 1914, when Norman was the first member of the City Council to volunteer for active service in the Army, it had covered nearly the whole City and attracted “well over 2,000 voluntary helpers”. Even so, Neville Chamberlain’s draft memoir of July 1911 continued:

so large a number [of helpers] was not sufficient for the magnitude of the task, that of assigning helpers to boys and girls leaving [Elementary Schools] – about 14,000 children every year – and in needful cases keeping in touch with them for three years.

Mr H. Norwood, the first Secretary of the Central Committee, has left us with the following picture of the charismatic vigour with which Norman promoted and fostered the scheme:

Nearly every Sunday found Mr. Chamberlain at an Early-morning School or a P.S.A. (Parent Student Association) gathering, and he delivered numerous other addresses at other times and places, always bringing away with him a sheaf of written promises of assistance. He was very anxious to have the help of all suitable existing organisations, so that those already in touch with boys and girls should add this new point to their interest. He secured the co-operation of religious bodies, boys’ and girls’ organisations and social workers; also the interest and help of employers and many workmen’s associations. […] Many of the helpers naturally needed to be educated for their work and to be stimulated if their zeal began to flag. This constantly exercised Mr. Chamberlain’s mind, and was the occasion of many circular letters and pamphlets which he wrote. Also he gave special addresses to helpers, and at his own expense brought to Birmingham men and women of national reputation to lecture on particular phases of social and industrial problems.

Moreover, because Norman was also concerned “to achieve great reforms and improvements in industrial conditions”, he encouraged the setting up of training workshops for boys and girls who wanted to enter a skilled trade and

lost no opportunity of pressing on employers the need for better canteens, improved sanitary and hygienic arrangements, facilities for recreation, the provision of overalls in dirty processes, and generally more human conditions calculated to foster self[-]respect in the young work[-]people

– i.e. measures which later issued in the appointment of Welfare Officers in a large number of works and factories.

1911 seems to have been a year of consolidation for Norman. In March the pressure of his various commitments – club, social and public work – took its toll and brought on a bout of depression and apathy that compelled him to take a much-needed holiday in Provence, where he visited Avignon, Arles and Nîmes. Later on in the year he moved from Calthorpe Cottage to 44 Russell Road, where he lived for the rest of his life, and in August 1911 he paid his second visit to Canada and satisfied himself that his boys were doing well there: two down a nickel-mine in Northern Ontario and the rest on farms. And when Birmingham was extended in 1911, he was elected as the Councillor for the Small Heath Ward in the south-east of the city, guaranteeing a further three years of public service, mainly in the areas of education and the provision of parks and open spaces. But he also became a member of the City Council’s General Purposes Committee and the Hon. Secretary of the Citizens Committee.

In February 1912, Norman was one of the 24 signatories of an open letter to The Times protesting against the evils of child labour. His co-signatories included eight MPs, among them Ramsey MacDonald (1866–1937; Britain’s first Labour Prime Minister in 1924 and 1929–31), Norman’s friend Steel-Maitland, two Bishops, and prominent educationalists and social workers. The letter pointed out that there existed a “vast army of boys” who worked “as messengers and errand-boys, as van-boys for the railway companies and carrying firms, and as junior clerks in many establishments” and who were not protected by existing legislation. These unfortunate lads, the letter continued, were often compelled to work from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. daily, i.e. up to 100 hours per week, in physically and mentally debilitating circumstances which left them no opportunity for improving their life chances through evening education and which made them so unfit that they were unsuitable, even, for the Army. So, the letter called upon the government to extend the terms of the Factory Acts and reduce such hours, to make in-service education compulsory for boys and youths aged 14 to 18, and, by implication, to bring down unemployment. But in November 1912, after returning from his third and final visit to Canada, Norman was given even more responsibility by being elected Chairman of the Education and Parks Committee; he immediately set about shaking things up. Even before his elevation, he had spent many a Sunday walking around the outskirts of Birmingham, whose size had increased to 40,000 acres in 1911, looking for undeveloped sites that were suitable for play areas, “the total absence of which made it so difficult at that time for boys and girls to engage in any healthy out-door exercise”. According to Norman’s co-worker Harry Norwood (1872–1935), who in 1911 was the Director of Education for the Borough of Aston Manor and rose to be the Assistant Education Officer for the City of Birmingham, Norman had a great sympathy with the youthful desire to let off steam: it was a necessary thing, and the wise and reasonable response was to provide suitable places and proper means for doing so. His explorations paid off handsomely when, in his first Chairman’s Report to the Council, he was able to state that there were at present “only 58 cricket pitches and 44 football pitches in the whole of the parks of Greater Birmingham” even though there were “at least 1,200 football teams in existence on any one Saturday”. The report continued:

Rents are seldom less than £6 a season for a pitch; the grounds are often boggy, uncut, uneven; they are mostly a long distance from the trams; there is no security of tenure. Hundreds of young fellows cannot afford these rents (added to tram fares, clothes, boots, and changing-room rent) and have to be content with kicking a ball about on waste lands or watching others play. Others who can afford to pay cannot obtain a ground.

Then, using the argument that the City Corporation was “the only body which can ensure a permanent supply of playing-fields at a reasonable rent within the reach of all classes”, he persuaded the City Council to take over a lease from the Birmingham Housing Reform and Open Spaces Association on 250 acres of land at Castle Bromwich. The land proved to be of great benefit to Birmingham’s young people – until 1914, that is – when the War Office requisitioned it as an airfield. Over the next two years, Norman was immensely active in his new role and his cousin Neville summarized his achievements as follows:

New open spaces and parks were acquired in various parts of the city. Bilberry Hill, a well-known and beautiful feature of the Lickey Hills, was purchased and added to the municipal lands already existing in that neighbourhood; fencing was removed, and many parts of the public parks hitherto unused were thrown open to the children; music and boating were provided, and even dancing was encouraged, to the great contentment of the young folks of the city.

Norman Gwynne Chamberlain at West Woodhay; photo taken between 19 October and 1 November 1917, when Chamberlain was on leave for the last time

(Courtesy of CRL)

“For my own part, while feeling the force of [his reluctance to leave the concrete realities of social work to understand which he felt was necessary to any effective progress], I could not but see how great a contribution to the national life he might ultimately bring, how rare in imperial politics was the combination of qualities which he possessed. With his wide interest in social reform he combined a clear and critical judgment; he formed his decisions coolly; but with all this he had that great gift of vision, so essential to leadership.”

By the end of 1913, Norman was on the sub-committee of the Unionist Social Reform Committee that was charged with the investigation of the present state of public education. The sub-committee’s first set of findings appeared in February 1914 in a publication entitled The Schools and Social Reform, whose Introduction came from the pen of F.E. Smith (1872–1930), perhaps the most brilliant advocate and speech-maker of his time. It made three sets of recommendations: (1) children should be better fed, subject to regular medical inspections, and protected from the evils of child labour; (2) the facilities for manual training should be expanded and the work of juvenile advisory committees extended; (3) the school leaving age should be raised and attendance at continuation classes should be made compulsory.

But during the run-up to war, Norman’s major contribution to the debate about destitution among the young was the lecture entitled ‘An English Municipality and Juvenile Labour’ that he delivered at the Victoria League Imperial Health Conference which took place in the Imperial Institute, Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London SW7, from 18 to 21 May 1914. The Victoria League had been founded in April 1901 as a result of the Second Boer War “for the promotion of knowledge of housing and town planning and the care of child life throughout the Empire” and its patrons were King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, who sent a message of their support to the 1914 Conference. The Conference was accompanied by an exhibition at London’s Grafton Galleries that was opened by the 4th Marquis of Salisbury (1861–1947), the son of a recent Prime Minister. The opening address was given by the Liberal politician Lewis Harcourt, MP (1863–1922; later the 1st Viscount Harcourt), the Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1910 to 1915, who described it as “a voluntary rally of the best minds of the British Empire in the service of humanity”. And most of the speakers were established “big names” from all over the Empire. Consequently, it was a signal honour for Norman to be asked to participate, even if he was the last speaker (21 May). His central concern overlapped to a considerable extent with that of the Conference as a whole: how to deal with the poverty and bad living conditions which characterized the large urban centres that were continuing to rise throughout the Empire, despite, not to say because of, its economic success. So he began his lecture by modestly describing it as an “account of an actual experiment” and then offered a summary of how, over the past five years, Birmingham had been trying to solve the problems connected with “juvenile labour”, with due regard for the city’s specific character and within the socio-legal context that had been created by Beveridge’s Labour Exchanges Act of 1908, the report of the Royal Commission on Poor Laws of 1909, and the Education (Choice of Employment) Act of 1910. Norman began from the premise that

we in Birmingham find that all parties concerned are generally and reasonably dissatisfied with the present conditions of juvenile labour and that any attempt to deal with it must face a threefold problem of health, work, and character.

He then gave a detailed description of the elaborate “machinery of the Birmingham scheme”, gave due credit to the work of the Labour Exchange officials, provided fairly detailed statistics from which the size of the problem and the success of the measures taken could be gauged, and finished with a reasonably optimistic assessment of the progress that had been made. He concluded:

Perhaps the most valuable result of the whole scheme is the creation (in the shape of the helpers) of a nucleus of practical people in all walks of life who are interested in and conversant with the great problem of the guidance of the adolescence of England; this is the first step towards securing amongst the public at large recognition of the existence of the problem, and a demand that the problem shall be dealt with. That is, I think, a result with much wider possibilities than those which were foreseen by us when we first started on the work.

When war broke out, Norman was still a member of the City Council’s General Purposes Committee and had become Chairman of its Parks and Education Committee. So it was fitting that on 13 February 1918, a week after his death in action had been confirmed by the chance discovery of his body (see below), The Birmingham Daily Post published a long report on a meeting of the City’s Education Committee that had taken place on the previous day. During this meeting, Alderman Sir George Hamilton Kenrick (1850–1939), a Birmingham engineer, industrialist and businessman who had a strong interest in educational reform and had been an active member of the City Council on its behalf since 1904 and the city’s Lord Mayor from 1908 to 1909, delivered a fulsome eulogy in honour of Norman Chamberlain, who, it was said, had become “increasingly popular from the day he first engaged in public life”. Sir George offered his audience a detailed and extensive account of Norman’s work for the city, two conspicuous features of which were said to be his enthusiasm and his “unselfish labours on behalf of the young people of the City,” and moved a resolution “expressing appreciation of his work and tendering respectful sympathy to his family”. Sir George said:

When [the Committee] called to mind not only the ability of Captain Chamberlain, but his zeal, enthusiasm and youth, he [Sir George] had looked forward to the time when he would occupy the position of chairman. In every work he undertook, Captain Chamberlain distinguished himself, and among other notable achievements was the work which he initiated and put on a sound basis connected with after-care and the employment of children after they had left school. Having regard to the prospective great extension of education, they saw how truly Captain Norman Chamberlain foresaw what was forthcoming. In other spheres of the public life he made equally strenuous efforts. He placed his services at the disposal, particularly, of his humble fellow beings. He inspired those with whom he worked with his own enthusiasm. Everybody felt he was of a lovable nature and that a noble life had met with a noble end.

Harry Norwood also spoke at length, recalling his friend’s “most lovable disposition” and “wonderful knack of enlisting the enthusiastic help of all his friends in his work”. Consequently, he concluded,

it was inspiring to see him in his Boys Club and notice with what ease and apparent enjoyment he would share in the games of the boys and make them feel that he was one of themselves. It was in that way [that] he gained their private confidence as well as their love and respect. […] Captain Chamberlain was possessed of great driving force, and he had a wonderfully inspiring personality. It was the rare combination of the[se] two qualities that made him so fine a leader.

and it was “his enthusiasm for philanthropic and social work which endeared [him] to the people”.

In Norman’s spare time – such as it was – he was, like his admirer Sir George Kenrick, a keen naturalist and discovered a species of butterfly that is now known as the Terias Chamberlainii.

War service

In late July 1914, Norman was camping in Llandudno on the north Wales coast with a group of Birmingham lads, and not enjoying the prospect of war at all:

Isn’t the War trouble awful? I’m awfully afraid we may get drawn into it, and I honestly shudder to think what the state of affairs will be like here and in the big towns if we are. Everyone will be out of work and prices sky-high; it will be a terrible time and anything might happen.

Logistical problems compelled Norman and his group to return home early, and when he got back to Birmingham, he, together with his friend Steel-Maitland, was co-opted on to a Citizens’ Relief Committee for the city. This absorbed all his energies for the next few weeks while the committee sought “to create a scheme of organisation to cover the whole town, deal with the worst imaginable state of distress, and yet be all right for a small amount of distress”. But in early September, he was already thinking of handing over his work to older men and women out of a sense of duty and of joining the Reserve Battalion of the Warwickshire Territorials as a Private, even though he was sure that he had no soldierly inclinations: “DAMN the Germans!” So leaving enough money behind for his work with boys to be continued while he was away, Chamberlain became the first member of the City Council to volunteer for active service and by 4 October 1914 he was training in civilian clothes with his chosen Regiment and acting as a Company Commander.

On 19 October, after a frustrating and inexplicable delay, he was gazetted Lieutenant in the 2/6th Battalion (Territorial Force), one of the three Birmingham Battalions, of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment that formed part of the 2/1st (Warwickshire) Brigade in the 61st (2/1st South Midland) Division. From February 1915 to late May 1915 the Battalion was stationed near Northampton, whence it moved to the area around Colchester where it stayed until March 1916. Norman, contrary to his expectations, turned out to enjoy soldiering and to be such a competent officer that in August 1915 Lord Salisbury, the 4th Marquess of Salisbury (1861–1947), instructed the Brigade Major to offer him the command of the Regiment’s 1/7th Battalion (Territorial Force) (which had been formed at Coventry in October 1914). But Norman refused as he was becoming increasingly tired of home duties in England while friends of his were being killed and wounded in France (e.g. C.H.G. Martin, with whom he had shared digs as an undergraduate at Oxford, who was killed in action on 1 May 1915). In October 1915, after a three-day-long route march, Norman went down with jaundice and was unable to return to his Battalion for three months, and during this enforced leave he began to think increasingly seriously of applying for a transfer into the Special Reserve of the Grenadier Guards. This he finally did on 3 December 1915, when the 2/6th Battalion was stationed near Maldon, Essex, and on 5 December he was interviewed in London and asked to send in a formal application. It was duly accepted, not least because he was a cousin of Austen Chamberlain (“the best possible recommendation”), and on 19 December 1915 he was gazetted Second Lieutenant with effect from 19 October 1914 in the 1st (Regular) Battalion, the Grenadier Guards (London Gazette, no. 445, 21 January 1916, p. 6). This unit had landed at Zeebrugge on 7 October 1914 as part of 20th Brigade, in the 7th Division, and on 4 August 1915 had become part of the 3rd Guards Brigade, in the newly formed Guards Division. Norman was glad to be leaving England for active service on the continent, but hated having to leave the 2/6th Battalion: “they’re such topping fellows, officers, N.C.O.s and men, taken as a whole”.

On Saturday 11 March 1916, Norman and six other officers were ordered to leave for France “on Tuesday next” and on 13 March he wrote a letter to Neville in which he told him that “You have been a real brother to me and I’m glad I have not had to say goodbye to you”. On Tuesday 14 March 1916 he finally embarked for Le Havre, and after spending a week with an entrenching Battalion, he and three other replacement officers joined No. 3 Company of the 1st Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, in the 3rd Guards Brigade, on 2 April. The Battalion had arrived at Poperinghe on 5 March, and was in reserve there until 21 March, when it spent three days in the trenches near Ypres. From 24 March until 1 April it rested in B Camp, east of Poperinghe, where Norman joined it just as it was about to do a six-week stint in the trenches near Ypres, which included spells in the front line at Potijze, an eastern suburb of Ypres.

Norman settled in quickly, and on 4 April 1916 spent his first day in a dug-out, during which he wrote a cheery letter to his sister Enid about his experiences so far, trying to make things sound less grim than they really were:

Well after we detrained, shell & flares all over the place, though none of them anywhere near us, we formed up & each platoon went off at 4 minutes’ intervals. […] So, led by our guide, we stumbled long the railway, falling over girders and into shell holes & passing other troops, transport etc. until we got to a road leading down to the canal. […] At about 11.30 p.m. we had dinner – hot soup, buttered eggs & ham & pigs cheek, pate de foie gras, and all sorts of dessert, drinks – whisky-soda, white wine, port & Coffee. Not bad considering where we are. But in this Batt[allion] they’re supposed to Mess better than in any other in the Army. Of course you can’t drink water if you want to, as there isn’t any, or it[’]s filthy. I shall soon take to brushing my teeth in Champagne. We always Mess by Companies, and we have a perfect cook, and a mess-waiter, equally good. Of course here we are not in the front line: the rest of the Battn is – 3 Coys in & one out. We are some distance from the front line – and all the shelling goes on over our head. […] I don’t find the whistle of the hells so alarming as one might expect, you can generally hear them coming & duck or jump into a trench, but the trouble is it is very difficult to tell if they’re coming directly at you or 200 yards to one side, or 100 yards over head! […] We are just on the edge of the town here & can see the ruined tower of the Cathedral [at Ypres] and of the other great building next [to] it. […] There has been absolutely nothing for us officers to do yet – so I have been enjoying myself. We have spent our time eating, sleeping, playing patience, reading and talking politics, & trying on our steel helmets – in which we all look rather like Japanese coolies. Everyone seems to agree that they are really very useful; all our front line men have them nowadays.

Two days later, he wrote another letter home, but its tone was already becoming more detached, more realistic, as the practical problems of life in the trenches began to impinge upon his well-developed moral conscience: “it is all most interesting, and at times, to a novice, most exciting”. But he also realized that his Battalion was “having an easy time of it, considering the [bad] part of the line we’re in” and that, although their trenches were “not very good”, they were “better than many and safer than most”, and that if he had not reached his Battalion by stages – “Base, Entrenching Battalion, Support Line” – he would have been “horribly frightened”. But, he concluded:

It is tragic to think of the ignorance, or selfishness, or pig-headed pride amongst people of all kinds at home, politicians and officials mainly, and then to be able to visualise it, as one can do now, as so many more weeks of this, so many more casualties, so many more disadvantages for us to suffer and allow for, so many more opportunities for Boche ingenuity and organisation.

Once out of the trenches he reflected on his experiences there and was relieved to discover that even when his Battalion was being subjected to a long bout of heavy shelling that “was really terrifying and ‘put the wind up me’, as they say, i.e. frightened me more than I could conceive possible”, he managed not to show it and continued to “talk in an even voice during it” despite his “naked and absolute” fear. Nevertheless, he continued, “it was extraordinary with what vivid intensity I realised, when the shelling was at its worst, how dear life is to one, and how very unpleasant it is to put it into any real jeopardy”.

From left to right: Hugh Valentine Cholmeley (1888–1916; killed in action on 7 April 1916 in the Ypres Salient), Guy Hargreaves Cholmeley (1889–1958), Harry Lewin Cholmeley (1893–1916; killed in action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme).

On 7 April, Hugh Valentine Cholmeley, the brother of Henry Lewin Cholmeley, who was attached to the Machine Gun Company of Norman’s Battalion, was killed in action outright by a large piece of shrapnel during a heavy bombardment, but Norman does not seem to have known him as he did not mention his death in any of his letters. 8 and 9 April were spent in Camp ‘B’, east of Poperinghe, and from 12 to 15 April Norman’s Battalion was back in the trenches, in a “beastly dug-out”, which he described in a letter of 14 April as “draughty and stuffy […], and everything covered with mud”. Although he had to share the cramped space with two other officers at any one time and it was impossible to sit up, the dug-out had one redeeming feature: it was possible to look back and get “a fine view of [Ypres] and the cathedral, etc., ruins sticking up in the middle and all the country this side of it – houses knocked to bits – many of the trees blown down. The grass scarred with brown shell-holes and trenches of all sorts.” By now, Chamberlain’s experience of the Army in general and of a Guards Regiment in particular was causing him to begin to be openly critical of the military system. He disliked the “stand-offishness” of Regular Guards officers towards Territorials and New Army officers, the “discipline which destroys initiative”, and the futile requirements and practices that cost lives, money and time but could not be questioned: “I’m afraid my argumentativeness is being bottled off and not killed off, and I will flare up like a Flammenwerfer [flame-thrower] when I am released from my present tutelage”. From 15 to 26 April 1916 the Battalion was back at Camp ‘B’, where, on 24 April, Norman had the time to write a very critical letter to his cousin Neville:

You are like a breath of fresh air & hope, after all the sloppy inefficiency one sees on all sides out here & [reads about] in the papers. What irritates me is that so many people can be quite aware of some futility, costing time, or money, or time, and yet don’t, and I suppose can’t, take any steps to have it abolished. The military system of discipline is quite inevitable I suppose [,] but it stifles effective criticism & induces a sort of apathetic querulousness or cynicism which I’m not used to.

From 27 April to 1 May the Battalion was in the trenches east of Ypres near Railway Wood and the Menin Road, and on 1 May 1916 Norman was able to continue his gripe about the individual’s inability to do anything about military waste and inefficiency, question pointless orders, or rectify institutionalized ineptitude, in a letter to his cousin (Caroline) Hilda Chamberlain (1871–1967), the second child of Joseph Chamberlain, and Neville’s sister. But he also, in the same letter, admitted his own ignorance about fundamental aspects of trench warfare until he came out to France – for instance “what an impenetrable veil hangs between the Front Line, with all it knows and thinks, and everything else behind – from Brigade staffs and higher, to newspaper correspondents and the general public”. This stint in the trenches was followed by five days in billets, and from 6 to 10 May the Battalion was in the trenches at Rifleman’s Farm, during which, when inspecting the troops on 9 May, Brigadier Frederick James Heyworth, CB, DSO (1863–1916), the General Officer Commanding the 3rd Guards Brigade, was killed by a sniper, one of the 78 General Officers to die on or as a result of active service during World War One.

This last stint in the trenches produced two letters of note. On 8 May 1916 Norman wrote another letter to Enid – which contained a graphic and amusing account of being under German artillery fire while returning in the evening from the trenches – and in a letter to Neville’s wife Annie, dated 8 to 10 May, Norman expressed his dislike of having a plate for breakfast put before him that contained “2 poached eggs, 2 thick slabs of fat bacon & a huge slice of roast beef”, all of which was topped out with “a mountain of mashed potatoes & baked beans”. On 11 May, after another day in billets in Ypres, the Battalion moved back to billets in a brewery at Poperinghe; by 20 May it was training and route-marching at Kieken Put, just over the border in France near Wormhout; and on 31 May, the Stokes Trench Mortar (TM) Battery of the Guards Division, to which Norman had been attached at Brigade level, put on a demonstration of the new weapon for the benefit of the Battalion.

But on about 2 June 1916, Norman was sent to hospital at Hazebrouck, with a severe cough that developed into severe bronchitis and then pneumonia. On 13 June he was transferred to No. 14 General Hospital, on the cliffs at Boulogne, and by 11 July he was at his parents’ house in West Woodhay, Berkshire, “to which he had become deeply attached and to which he always returned when he could”. But by 14 July he was a patient in the Officers’ Hospital at 6 Grosvenor Place, Belgravia, London SW1, where he was given more sick leave until 3 August 1916. On 10 August he joined the Regiment’s 5th (Reserve) Battalion from sick leave, but as his condition had not improved significantly by the end of the month and he was diagnosed as suffering from “abdominal distension as a result of ‘self-poisoning’”, his leave was extended, this time by six weeks, most of which he spent in Llandudno, on the coast of North Wales, and at West Woodhay. Nevertheless, on 3 August he was able to attend his aunt’s marriage to Canon Carnegie in St Margaret’s, Westminster, and on about 17 August, when the couple returned from their honeymoon, he and his half-brother Austen Chamberlain dined with them in Prince’s Gardens, London. But shortly after 10 August, he heard that his great friend E.V.D. Birchall had died in France of wounds received in action and said in a letter that the news had distressed him “more than anyone else[’s death] since the war began” since “he was quite one of my best friends and really a very noble fellow. It’s hard to stand it all.”

Norman was finally cleared for general service on 1 November 1916, having missed all but the very last part of the Battle of the Somme in which the 3rd Guards Brigade had been heavily involved since August – especially in the attacks at Ginchy (12 September), Flers-Courcelette (15/16 September) and Lesboeufs (25 September). So he returned to France on 7 December via Le Havre and Rouen, and spent a few days near the old front line with the same entrenching battalion as in the previous year. By now, however, his attitude to army life and the war had become far more sceptical and critical than it had been a year previously, and on 31 December he wrote to his mother:

It will help you all to bear the extra taxes etc., at home, to know that there are hundreds of pounds’ worth of stuff within a mile of here lying about all over the place, and well behind where any fighting was – bombs, ammunition, steel helmets, horse-shoes, shovels, copper wire, steel rails, etc., etc. Talk about waste at home! Similarly most of my work is a waste of time. If any of my Heads of Departments or the Council organised things as this battalion is, I should have sacked them on the spot. […] However, I’m ceasing to worry about all the inefficiency I see round me – and trying to take up the army attitude – “It isn’t my job, so I needn’t worry about it! Mind your own business!”

He rejoined the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards on New Year’s Day of 1917, when it came out of the trenches and spent the night in Maltzhorn Camp before marching, on 2 January 1917, to billets at Méaulte, a village just to the south of Albert and well behind the front. Then, for the next five months, it moved in and out of the trenches that were mainly at or near Maltzhorn Camp, Méaulte, Corbie and Méricourt-sur-Somme, around eight miles to the west of Corbie – but the Battalion War Diary is not very precise. On 5 January 1917, when Norman was spending a week in charge of 100 men who were loading ammunition etc. in an ammunition park, he wrote a graphic and very moving piece about conditions at the front:

If people at home realised the absolute misery the private soldier has to go through out here – mere discomfort in excelsis piled on discomfort – all the little things gone wrong – all at the wrong moment, and always false hopes of something better – and when you do get your food or your comfort and your whatever it may be – always something wrong with it –not enough – or it’s gone bad – or it’s damp, or the wrong people have got it – almost always damp, lousy, and dirty, and carrying a great deal more than is really possible – if you’ve got to march it’s over bad, rough roads or slippery unmetalled tracks, 2 feet deep in mud – no nails will help you – if you want to rest there’s nothing but mud to sit on and when you go to sleep the billet is a barn full of huge draughts and huger rats and insufficient straw – verminous at that – and damp clothes and boots to put on next morning, and hardly any leave. It’s all those sorts of inconvenience piled one upon the other and repeated daily that a man can’t stand – not the mere danger of being under fire. Of course it all adds to the strain on the nerves and breeds grousing and downheartedness and insubordination. […] Of course, there’s a very big gulf – too big one I think – between the officers’ and the mens’ condition.

By 23 January, when the Battalion was out of line for extended periods, snow had lain on the ground and there had been hard frosts for four or five days. But although the Battalion was now housed in tents and huts and Norman declared that the cold was preferable to the damp and the rain and the mud, the cold was nearly unbearable at night, especially for the men in the tents: “It was so cold [last night] that we found this morning that all the soda-water in the bottles in this hut had frozen solid, despite the [excellent French] stove and the fact that two of us were sleeping in it!” The cold spell persisted into early February, turning the devastated landscape into a dazzling snowscape, and although it had the same effect on the German infantry as it did on the British, and even generated a certain amount of long-distance fraternization between the two sides as they sought to keep warm, it did not stop the shelling with its attendant noise, and the frozen ground ensured that the shrapnel splinters flew for longer distances. Even so, Chamberlain remarked: “I don’t think the frost makes us feel quite so fed-up as the mud”. Indeed, on 4 February 1917 he wrote to Neville Chamberlain that he was enjoying himself now despite the cold, and one reason was that he had much more work to occupy him now than at any time since joining the Regiment. Nevertheless, from early February onwards, Norman was out of the line for nearly three months, i.e. during the period when the Germans were withdrawing eastwards to the Hindenburg Line (14 March–5 April) and during the first two weeks of the Battle of Arras (9 April–16 May), but it is not clear from his letters what he was doing during this period. He returned to his Battalion on 26 April 1917, when, until 16 May, it was training and providing working-parties at Tincourt-Boucly, three miles east of Péronne, i.e. where the British were digging in opposite the Hindenburg Line. But as the weather got warmer, life in France became less desolate: there was

the usual compulsory “heartiness” of this regiment – compulsory football, compulsory jumping, etc., all, I suppose, to harden us and work us up, etc. – the public-schoolboy idea again, and rather too much for old gentlemen of sedentary natures aged 32–38, as many of us are. So far, I admit, it has done me good.

And then, he added, there was the pleasure of hearing the first cuckoo, seeing the first butterfly and first frog, doing some makeshift gardening, finding the occasional untouched village, and beginning the training once again.