Fact file:

Matriculated: 1903

Born: 16 January 1885

Died: 15 September 1916

Regiment: Grenadier Guards

Grave/Memorial: Thiepval Memorial: Pier and Face 8D

Family background

b. 16 January 1885 in the Hanover Square area of London W1 as the younger son (fourth child) of Arthur Philip (1838–1905), the 6th Earl Stanhope (1875–1905), and Evelyn Countess Stanhope (née Evelyn Henrietta Pennefather) (1845–1923) (m. 1869). At the time of the 1891 Census the family was living in Chevening Park (25 servants living in), near Sevenoaks, Kent; at the time of the 1901 and 1911 Census the family were living at 20 Grosvenor Place, London (14 servants and 12 servants).

The Hon. Richard Philip Stanhope, JP MA.

Parents and antecedents

The Stanhope family was prominent in the north of England as early as the thirteenth century and became increasingly prominent further south in the fourteenth century. The earldom was created in 1718 for General James Stanhope (1673–1721), who had been a soldier on the Continent from 1692 to 1712, was a prominent Whig politician by 1714, and became one of George I’s two Secretaries of State and a Privy Councillor.

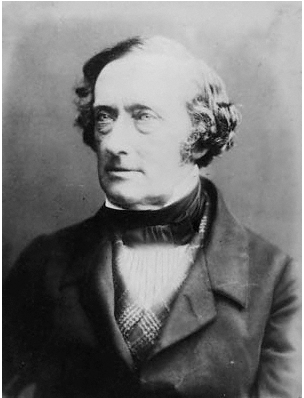

Stanhope’s grandfather, Philip Henry Stanhope (1805–75) (Viscount Mahon 1816–55, the 5th Earl Stanhope 1855–75), was MP for the rotten borough of Wootton Bassett (now Royal Wootton Bassett) until it was disenfranchised in 1832. He was the half-brother of Lady Hester Stanhope (1776–1839) (companion of her uncle William Pitt (1759–1806) and eccentric traveller in the Middle East); he held various Government appointments to do with foreign affairs, and was a Peelite. But he had other interests and turned down many Government positions. He was a historian “insufficiently speculative to be a great historian. But he was certainly a good one.” His History of England from the Peace of Utrecht to the Peace of Versailles, 1713–1783 was for many years regarded as the standard work on English eighteenth-century history. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the preservation of public documents, and was involved in the decoration of the new Palace of Westminster. One of his lasting legacies stems from his being a founder of the National Portrait Gallery.

Philip Henry Stanhope, fifth Earl Stanhope (1805–1875)

by Herbert Watkins, 1857

© National Portrait Gallery, London

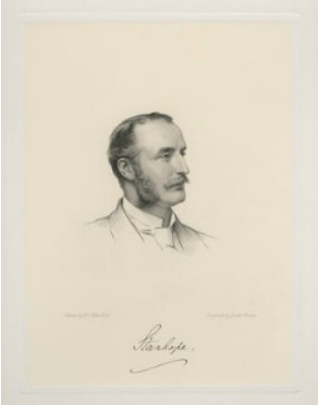

Stanhope’s father was a close friend of Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881) – who proposed the toast at his wedding. He was the MP for Leominster (1868) and Suffolk East (1870–75) before becoming a Lord of the Treasury (1874–75). After inheriting the earldom in 1875, he became the first Church Estates Commissioner, from 1878 to his death, and from 1890 until 1905 he was Lord Lieutenant of Kent. A strong high churchman, he worked in the latter two capacities closely as adviser to several Archbishops of Canterbury.

Arthur Philip Stanhope, 6th Earl Stanhope

by Joseph Brown, after Henry Tanworth Wells

stipple engraving, 1878 or after

© National Portrait Gallery, London NPG D20720

Stanhope’s mother came from an old Irish family that had produced a large number of distinguished soldiers and lawyers. Her father, Richard Green Pennefather (c.1808–1849), graduated from Balliol College in 1828 and entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1846. Shortly before his death, from cholera after visiting a workhouse, he became Under-Secretary for Ireland. After his death her mother, Emily Georgina Arabella Butler (1811–95), married General Henry Aitcheson Hankey (1805–86). During the last quarter of the nineteenth century Stanhope’s mother was one of the principal hostesses of the Conservative Party and her Saturday evening parties were famous for bringing together politicians, artists and men of letters.

Evelyn Henrietta (née Pennefather), Countess Stanhope

by Camille Silvy, albumen print, 23 July 1861

© National Portrait Gallery, London NPGAx55158

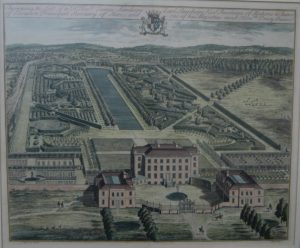

Chevening House, the Stanhopes’ family seat, comprises a 3,500-acre estate whose history goes back 800 years and was developed over seven generations. The original house was designed by Inigo Jones, built by the 13th Lord Dacre between 1615 and 1630, and acquired by General James Stanhope in 1717, the year he became Viscount Mahon. By 1869 it was giving employment to 25 domestic servants.

Siblings and their families

Brother of:

(1) Lady Emily Margaret (1870–1932);

(2) Lady Katherine Lucy (1873–1921);

(3) James Richard (later KG, PC, DSO, MC) (1880–1967), Viscount Mahon, later the 13th Earl of Chesterfield (1952) and the 7th Earl Stanhope (1905); married (1921) Lady Eileen Agatha Browne (1889–1940), the eldest daughter of George Ulick Browne, the 6th Marquis of Sligo. As there were no children, both earldoms lapsed in 1967.

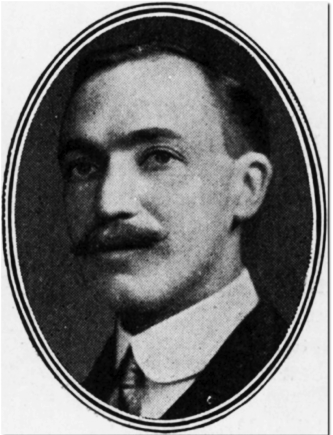

James Richard Stanhope, 7th Earl Stanhope

(The Graphic, no. 2463, 10 February 1917, p. 8)

Richard Philip’s two sisters never married, but James Richard, who became the 7th Earl, had a very distinguished career. Like his brother, he was educated at Eton and Magdalen (1899–1900), where he was known as Viscount Mahon, and in summer 1900 he rowed in Magdalen’s First VIII (which went Head of the River), in the College VIII (which reached the finals of the Visitors’ Cup at Henley), and in the College pairs (which won that year). But after only three terms at Magdalen he left Oxford without taking a degree in order to join the Army and avoid being junior to many officers who were younger than himself. After spending the last three months of 1900 in Paris in order to learn French, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards on 5 January 1901 and subsequently served in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1902), mainly on blockhouse duties.

After his return, he succeeded to the earldom in 1905, served as aide-de-camp to the General Officer Commanding the London District from 1906 to 1908, and retired as a Captain but remained on the list of the Grenadier Guards’ Reserve of Officers as a Lieutenant-Colonel. In 1908–09 he went on an extended tour of USA and the Far East, and in 1910 he became a member of the London County Council, representing Lewisham. Over the next four years, he was very active publicly: he took his responsibilities as a landowner seriously and was a popular landlord, and regularly attended the House of Lords. In 1912 he represented the Upper House against the Commons in a shooting competition which also involved V. Fleming; he was on the council of the Country Landowners’ Association; he was President of the Kent Emigration Society; he worked for the National Service League; and he was second-in-command of the 4th Battalion (Territorial Force) of the Royal West Kent Regiment. Together with the Hon. Charles Thomas Mills, MP, with whom he had just missed overlapping at Magdalen, he was part of a very distinguished parliamentary delegation to Canada and the USA which, in 1913 and 1914, helped to organize the celebrations that would commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Treaty of Ghent (i.e. the Treaty which, in 1814, put an end to hostilities and guaranteed a state of permanent peace between Britain and the USA).

On the outbreak of war, James Richard rejoined the Grenadiers and arrived in France with the second draft of Grenadiers on 13 November 1914, so missed the slaughter of the First Battle of Ypres. He then served in the trenches until 24 February 1915, when he became a General Staff Officer (Grade 3) at the headquarters of General Plumer’s V Corps (London Gazette, no. 29,151, 30 April 1915, p. 4,245; no. 29,422, 31 December 1915, p. 2). He stayed with V Corps until 1 December 1916, i.e. throughout the Battle of the Somme, and was mentioned in dispatches on 1 January 1916 and awarded the MC on 14 January 1916 (LG, no. 29,841, 14 January 1916, p. 11,677). From 1 to 20 December 1916 he served as a Staff Officer with XIII Corps; he was then transferred to II Corps until 19 December 1917; and at the beginning of June 1917, he was awarded the DSO on General Allenby’s recommendation (Edinburgh Gazette, no. 13,099, 4 June 1917, p. 1,066). He also became a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. In December 1917 he was transferred to the British Military Section of the Supreme War Council at Versailles, where he worked from early January 1918 to 14 May 1918. He was then sent back to England to work in the War Office as an extra (unpaid) Parliamentary Secretary to the War Office under Lord Milner (the 1st Viscount Milner, 1854–1925), an influential member of David Lloyd George’s five-man War Cabinet.

After five years in political limbo, James Richard’s post-war political career ran from 1924 to 1940. From 1924 to 1929 he was a Civil Lord of the Admiralty (Privy Councillor 1929); in 1930 he became a Trustee of the National Gallery; in 1931 he was, for a time, Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty; and from 1931 to 1934 he served as Under-Secretary of State for War (Knight of the Garter 1934). He gained his first Cabinet appointment in June 1936, when he became First Commissioner of Works, and he remained in this post until May 1938. In July 1936 he represented Britain at the Montreux Conference which gave back to Turkey control of the Dardanelles and the right to regulate military activity in its proximity. For six months in 1938 he exchanged this post for the Presidency of the Board of Education; from February 1938 to 14 May 1940 he was Leader of the House of Lords; from October 1938 to September 1939 he was First Lord of the Admiralty until replaced by Winston Churchill; and from September 1939 until 11 May 1940 he was Lord President of the Council, the fourth highest of the UK’s Great Officers of State, whose job is to present business to the Privy Council for the Monarch’s approval. But although he remained an active member of the House of Lords until the end of 1960, he did not serve in the coalition government that came into being under Churchill on 10 May 1940 and he never again held ministerial office. From 1941 to 1948 he chaired the Standing Committee on Museums and Gardens. A man of great personal charm, he was regarded by those who knew him as “a conscientious and hard-working servant of the state”. Having no heirs, he left Chevening to the state in 1959. The Chevening Estate Act stipulated that Chevening’s future resident should be a Prime Minister, Cabinet Minister, widow of lineal descendant of King George VI or the spouse, widow or widower of such a descendant. It is currently used as the official residence of the Foreign Secretary.

Wife and children

On 26 February 1914 The Times announced that a marriage had been “arranged” between Richard Philip Stanhope and Lady Beryl Le Poer-Trench (1893–1957), and the sumptuous society wedding duly took place at St Paul’s, Knightsbridge, in May 1914. His obituarist in the Lincolnshire Echo noted that the event was made “the occasion of great rejoicings at Revesby Abbey”, the couple’s marital home, “the celebrations including the entertaining of nearly 400 school children from the district and the tenants and their employees”, and his Eton obituarist would recall that “the radiant happiness of his married life (as of his home life before) leaves a memory which cannot easily be effaced”.

Lady Beryl Le Poer-Trench (1893–1957)

(The Sketch, no. 1,101, 4 March 1914, p. 28)

Revesby Abbey is about seven miles south-west of Horncastle, Lincolnshire, and the story of how it came into the possession of the Stanhope family is a complicated one. The first Revesby Abbey was a Cistercian Abbey that was founded by the Earl of Lincoln in 1143 and became a country house after it was dissolved as a monastery in c.1538. The second Revesby Abbey was built in the early eighteenth century and it, together with its 6,000-acre estate, came into the Banks family in 1715, when it was bought for £14,000 by a wealthy Sheffield lawyer, Joseph Banks (1665–1727), MP for Grimsby and Totnes from 1722 to 1727. Its most famous owner was Joseph’s great-grandson, the internationally famous botanist and naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820), whose name now features in that of c.80 plant species. When he inherited the Abbey in 1761 from his father William Hodkinson Banks (1719–61), he had already decided not to make a Grand Tour of Europe, in order to finance and take part in Captain Cook’s first voyage of discovery on the Endeavour (1768–71). But although Sir Joseph married Dorothy Hugessen (1758–1828) in 1779, he died without a legitimate heir and his estate passed into the hands of the Stanhope family via his distant cousin the Hon. Lieutenant-Colonel James Hamilton Stanhope (1788–1825), then Secretary of War.

For complex reasons, the Stanhope family did not take over the estate in any serious way until 1842 and allowed the house and grounds to fall into neglect. So the second Abbey was demolished in 1844 and the third Abbey, a huge mansion designed in a style that combined Classicism with some understated neo-Gothic features, was completed in 1846. In 1874, the estate passed from the unmarried James Banks Stanhope (1821–1904) to the 5th Earl Stanhope’s second son, i.e. Stanhope’s younger brother, the Conservative politician the Right Hon. Edward Stanhope (1840–93). After a distinguished career at Oxford (BA, 1861; MA, 1865; Fellow of All Souls, 1862), Edward Stanhope became a successful barrister (Inner Temple), went in for politics and became the MP for Mid-Lincolnshire in 1874 and MP for the Horncastle Division of Lincolnshire in 1885. He also became Under-Secretary of State for India (1878–80), Secretary of State for the Colonies (1886–87) and Secretary of State for War (1887–92). In 1870 he married Lucy Constance Egerton (1841–1907), the daughter of the Reverend Thomas Egerton (1809–47), but they remained childless, and when Lucy Constance died in 1907, Revesby Abbey passed to their nephew, the Hon. Richard Stanhope.

Richard’s wife, Lady Beryl Franziska Kathleen Bianca Le Poer-Trench, was the only daughter (along with four sons) of the 5th Earl Clancarty (1868–1929) of Garbally Court, Ballinasloe, and his first wife (m. 1889), Isabel Maude Penrice Bilton (1868–1906) (the popular actress and music-hall singer known as Belle Bilton). Lady Beryl’s family was originally French: it came from La Tranche, in Poitou, and settled in Northumberland in 1574. The first Earl Clancarty (peerage of Ireland) was created in 1803 but the English peerage goes back much further, to the exile of Charles II in the seventeenth century. Lady Beryl gave birth to a still-born son on 16 September 1916, one day after Richard’s death on the Somme, and the estate remained her property for life. In 1917 Lady Beryl married Lieutenant-Commander (RN) Walter Raleigh Gilbert (1889–1977), and they had one son (Humphrey Trench: 1919–42) and one daughter (Ann Destine: 1918–2006). But the couple were estranged by June 1922 and their marriage was dissolved in 1927. In 1931, Lady Beryl married Francis Edward Selby Groves (1899–1959).

After surviving the Battle of Britain, shooting down six-and-a-half enemy aircraft (1940–42), and being awarded the DFC, Squadron-Leader Humphrey Trench Gilbert was killed on 2 May 1942, aged 22, while serving as the Commanding Offier of 65 (East India) Squadron, Royal Air Force, that was based at RAF Great Sampford, North Essex. It seems that he and a brother officer, Flight-Lieutenant David Gordon Ross (1905–42), wished to attend a mess party at nearby RAF Debden. As the station two-seater Miles Magister was unserviceable, Humphrey Trench borrowed a single-seater Spitfire Mk V and took off with Ross sitting on his lap, but shortly after take-off the aircraft crashed at Loves Farm, Cutler’s Green, Thaxted, North Essex, killing both men. Humphrey Trench is buried in Saffron Walden Cemetery, Compartment 41, Grave 17. As a result of his premature death, his sister, Ann Destine, inherited Revesby Abbey estate after the death of her mother, and from her it passed to its present owners in 2006.

Education and professional life

From 1894 to 1898 Stanhope attended ‘Evelyns’ School, Colham Green, Hillingdon, Uxbridge Middlesex, whose Headmaster from 1872 to 1931 was Godfrey Thomas Worsley (1842–1920), the father of E.G. and J.F. Worsley (cf. R.A. Perssé, C.A. Gold, E.G. Worsley, F.W.T. Clerke, T.G. Rawstorne, J.F. Worsley). He then attended Eton College from 1898 to 1903,

during which time he developed the sterling character which marked all his life and exercised in his own unassuming, cheery way an influence for good which was as striking in its effects as it is hard to describe. Always keen on the river, he quickly got his ‘Boats’ and rowed with some distinction, though failing to get his Eight.

He was also a member of the Eton Rifle Volunteers and rose to the rank of Lance-Corporal. He matriculated at Magdalen as a Commoner on 19 October 1903, having passed Responsions in Hilary Term 1903. He took the First Public Examination in Trinity and Michaelmas Terms of 1904 before reading for an Honours Degree in Law. He was awarded a 3rd in Jurisprudence in Trinity Term 1907, and he took his BA on 24 October 1907 and his MA in 1912.

The Hon. Richard Philip Stanhope (c. 1907; detail from a group photo of the Rupert Society)

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

While training in Magdalen’s 1st Torpid during the first two weeks of February 1905, Stanhope, who was only 5 foot 9 inches tall and weighed only 9 stone 6½ lbs, rowed at No. 7 in a crew that also included A.H. Huth at stroke, N.G. Chamberlain at No. 2, and J.L. Johnston at No. 3. But although the Magdalen 1st Torpid “rowed very pluckily”, especially in its “very exciting race” with New College on 22 February, its performance was otherwise lacklustre and they started and finished Fourth on the River in the First Division. The Secretary of Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC) later assessed Stanhope’s performance as follows: “A very neat oar, but too light and weak for 7 in a strong rough Torpid”. A year later, in Hilary Term 1906, Stanhope rowed as bow in Magdalen’s 1st Torpid, which also included Johnston at No. 5, and Huth as stroke. The crew’s performance had so improved over the intervening year that it obtained two bumps and rose from fourth in the 1st Division to Second on the River. The Secretary of MCBC noted:

It was merely a piece of bad luck that the 1st [Torpid] did not catch Univ[ersity College] on Tuesday [28 February 1906] as from the Red Post in, five really hard strokes at any point would have given them their bump, but owing to the huge crowd it was impossible to acquaint them of this fact & cox’s voice was weak, too weak to be heard above the shouts up the barges.

And Charles Leslie Garton, now Magdalen’s Captain of Boats for 1906/07, noted of Stanhope: “A hardworker [sic] who pulls more than his weight, with a round back which is, however, perfectly firm.” In Trinity Term 1906, with his weight up by a mere 2½ lbs, Stanhope rowed bow in the College VIII once more, this time with Johnston at No. 4, A.G. Kirby at No. 5, L.R.A. Gatehouse at No. 6 and E.H.L. Southwell as stroke, and after rowing hard over five full courses, the VIII came Head of the River for the second year in succession, and Gatehouse described Stanhope even more appreciatively as “a first-rate bow; neat and a good waterman, and a very hard worker, pulling a good 11 st.” At the Henley Regatta (14–16 June), Stanhope did very well in the Oxford University Boat Club (OUBC) Sculls, and then, after a couple of substitutions during practice, the four men mentioned above rowed in the Magdalen VIII when it competed for the Grand Challenge Cup, but lost to a Belgian VIII on 3 July 1906 in the first round of the heats by 1¼ lengths in seven minutes: this crew was one of the two Magdalen VIIIs that would lose five out of nine men killed in action.

Because the freshmen who came up in Michaelmas Term 1906 were very promising, the College decided to set a precedent by entering a Second IV for the OUBC Challenge Cup. Stanhope rowed in a crew with J.R. Somers-Smith at stroke and C.R. Cudmore at No. 2, and they won the Cup, beating Magdalen’s 1st IV in the process. Southwell, the Secretary for 1906/07, continued his praise for Stanhope as follows: “a light oar who pulls far above his weight. A firstclass [sic] waterman, like most scullers; steered excellently.” Although, in Trinity Term 1907, the crew of the Magdalen VIII in the Summer Eights included Stanhope at bow, D. Mackinnon at No. 3, Kirby at No. 6, Southwell at No. 7, and Somers-Smith at stroke, they lost the Headship on the third night. So Stanhope, along with Kirby and Southwell, had the sad distinction of rowing in the two Magdalen VIIIs that would lose the majority of their nine men killed in action in the Great War. At Henley in summer 1907, the MCBC won all three of the four-oar races, with Stanhope a member of the crew that won the Stewards’ Challenge Cup, and he finally gained his Blue on 4 April 1908 when, together with Southwell (No. 7), Kirby (No. 6), Cudmore (No. 2), and Arthur William Donkin (1887–1966) as cox, he rowed bow in the Oxford VIII when it was beaten by Cambridge by two-and-a-half lengths after lagging behind all the way. At Henley in the same year, Stanhope rowed with Somers-Smith, D. Mackinnon and Kirby in the crew which competed for the Stewards’ Challenge Cup and the Grand Challenge Cup. During training, however, Kirby sprained his knee badly and rowed the race with his leg bandaged, so was unable to do his full share of the work. Then Stanhope strained his stomach and rowed the race with his body strapped up. Magdalen’s Captain of Boats noted: “His was an especially plucky performance, as he had not done any rowing for a year, and he was very light indeed to stroke such a heavy crew. His performance was in every way a great one.” Not surprisingly, Magdalen was defeated in both races. Tough, skilled and determined, Stanhope was, despite his slight build, an oarsman who played a full part in keeping Magdalen’s VIIIs high on the river. He was also an adept at shooting and fishing, and hunting was a favourite pastime since he was a regular follower of the South Wold Hounds.

Magdalen crews at Henley 1907: standing left D. Mackinnon; standing right R.P. Stanhope; seated left J.R. Somers-Smith; seated right E.H.L Southwell

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College)

After leaving Oxford and inheriting Revesby Abbey (see above), Stanhope, like the slightly older G.M.R. Turbutt, settled down to the life of a dutiful country squire. His Eton obituarist would later record that he “settled down [in Lincolnshire] to master every detail in the management of his estates and take his full share in county and other local affairs […] with his customary thoroughness”. And his obituarist in the Lincolnshire Echo shared this opinion, writing that “in public work of all kinds he was most interested” and complementing it by painting the following, comprehensive picture of Stanhope’s activity as a public figure:

In the Horncastle district, as well as on the Spilsby and Boston side, Capt. Stanhope was ever ready to help on any good work, and not only did he lend his beautiful gardens and park for the purpose, but took an active part in promoting the event. The Revesby Foal Show and Horticultural Show owes much to his organising abilities. […] He was also a member of the Lindsey County Council, a member of the Horncastle Board of Guardians, Chairman of the Horncastle Rural Council, and a member of several other bodies. He was Lord of the Manor of Horncastle, taking an active interest in the welfare of the town, and being most generous in his gifts. In politics he was a Unionist, working hard for the cause he had at heart, and was rapidly developing into an eloquent speaker on political platforms. He was a Vice-Chairman of the Horncastle Division Central Conservative Association, and also on the Executive Committee, President of the Horncastle and District Conservative Association, also of the Conservative Club, President of the Mareham Conservative Association, and a keen worker for the Primrose League.

Revesby Abbey

(courtesy Revesby Abbey Country house Restoration)

Stanhope was also interested in the work of magistrates and on 10 April 1909 he became a Justice of the Peace for the Lindsey District of Lincolnshire and, when his other duties permitted, sat on the Horncastle Bench. On 20 October 1911 he became one of the members of the Bench who could exercise the powers conferred on magistrates by the Lunacy Act of 1890 “in relation to orders for the reception of Lunatics not being Paupers”; he sat at the Quarter Sessions of 12 April 1912; and on 17 October 1913 he was once again appointed a member of the Lunacy Act Executive. On 23 September 1916, shortly after his death in action, at a meeting of the Horncastle Petty Sessions, his fellow magistrates stood in silence to pass a resolution which expressed their sorrow over the “lamented death” of “a man who was dearly loved in the county” and who was considered “a very promising gentleman, whose place would be difficult to fill”. And after their meeting on 26 September 1916, the Horncastle Board of Guardians paid him a similar tribute, praising “his sterling qualities, his business capacity, his unfailing cheerfulness and courtesy, and his ready sympathy”.

Stanhope seems to have been particularly involved in local education, and his involvement seems to have begun even earlier than his work as a JP, on 25 May 1908, when the Clerk of the Governors of Horncastle Grammar School (founded in 1571 and now an Academy that is independent of Local Authority control) “was instructed to write to the Hon. Richard Stanhope’s Agent as to cleaning out the ditches adjoining [the] site of [the] new [Grammar] School” that was being planned for Horncastle, and by 8 September 1908 he had agreed to become a Governor of the school. On 13 October 1908 “it was resolved to ask the Hon. R[ichar]d Stanhope to lay the Foundation Stone of the new buildings”, and this he did on 7 December 1908 after attending a meeting of the Governors. The new school cost £3,487 to build and opened on 1 September 1909 with Stanhope attending once again in his capacity as Lord of the Manor. He is also recorded as attending Governors’ meetings on 6 April 1909, 21 September 1909, 16 November 1909, 25 July 1911, 28 May 1912, 1 October 1912 and 27 May 1913, and he acted as Chairman for the meeting of 23 July 1912. After an initial period of enthusiasm it would seem that his interest waned, and it seems probable that his courtship and marriage diverted his attention from public affairs to more private ones. In a letter of condolence that President Warren wrote to Evelyn Fleming, the widow of Valentine Fleming, MP, on 25 May 1917, he said that although in a way he had felt every one of the college losses, he had felt only two with the same kind of intensity that he had felt the loss of her “dear and gallant husband” – that of “his comrade in the House, ‘Charlie’ Mills”, and that of ‘Dick’ Stanhope.

The Hon. Richard Philip Stanhope, JP MA

(Photo courtesy of Magdalen College, Oxford).

“One of the most popular gentlemen in the county, beloved by all who knew him.”

“The whole neighbourhood is in mourning for the loss of a true type of English gentleman, a good-natured landlord and a magistrate who performed his office with discrimination and justice.”

Military and war service

As a member of the Lincolnshire squirarchy, Stanhope became a Second Lieutenant on probation in the 1/1st Lincolnshire Yeomanry (Territorial Force) with effect from 9 December 1909 (London Gazette, no. 28,328, 11 January 1910, p. 253). His commission was confirmed on 12 January 1910 and on 8 December 1913 he was promoted Lieutenant. He was called up on the outbreak of war and continued in the Yeomanry for 11 months, undergoing training at Lincoln and in Norfolk. But as he was told that he would not be allowed to accompany his unit when it departed for the Mediterranean in late October 1915, he had his Commission transferred to the Special Reserve of the Grenadier Guards (LG, no. 29,272, 20 August 1915, p. 8,381) when its 3rd (Regular) Battalion, in which his older brother James Richard was already serving as a Major, was forming at Wellington Barracks, London. Stanhope was promoted Captain in that Battalion with effect from 15 July 1915 (LG, no. 29,277, 27 August 1915, p. 8,542) and given command of 3 (‘C’) Company, which H.D. Vernon would join as a Subaltern in Summer 1915. Eleven days later, on 26 July 1915, the Battalion left Chelsea Barracks for Southampton and arrived in Le Havre on the following day, where it immediately entrained for St-Omer. On 29 July it arrived at Esquerdes, five miles west-south-west of St-Omer, and it trained in this area, mainly near Maurepas, for all of August and most of September, becoming part of the 2nd Guards Brigade in the newly formed Guards Division on 19 August 1915.

The Guards Division took part in the Battle of Loos (25 September–14 October 1915) and was in position by nightfall on 26 September. But Stanhope’s Battalion spent the first two days of the battle in reserve and the night of 26/27 September in extreme discomfort, waiting in an icy wind and pouring rain to help take over the line from the 15th (Scottish), 21st and 24th Divisions, which had suffered devastating losses on 25 September. On 27 September the 3rd Battalion was one of the two Battalions in support when the 2nd Guards Brigade attacked Chalk Pit Wood, just to the south of Hulluch, across roughly three-quarters of a mile of open countryside. And in the mid-afternoon, Stanhope’s 3 Company was kept back yet again when the other three Companies of the 3rd Battalion were brought into the battle to assault the German line between Puits 14bis (Shaft 14b) in the north and the well-fortified redoubt on Hill 70 in the south. Whereas the attacking Companies of the 3rd Battalion were subject to extremely heavy machine-gun fire from the Bois Hugo, just behind Puits 14bis, and lost 229 of its officers and other ranks (ORs) killed, wounded or missing without achieving anything of significance, 3 Company was spared the worst of the casualties. There was relatively little fighting in the weeks immediately following the fighting of late September, but on 3 October Stanhope’s Battalion was resting in billets opposite the Hohenzollern Redoubt, a heavily fortified German position just to the south-west of Auchy-les-Mines, and the Battalion helped to repulse the Germans when they attacked in force on the afternoon of 8 October, losing 137 officers and ORs killed, wounded or missing.

Stanhope’s Battalion stayed in the vicinity of Loos until 25 October 1915, when it marched some seven miles north-westwards to Béthune. Here it was joined by Raymond Asquith (1878–1916), the eldest son of the Rt Hon. Herbert Asquith, PC (1852–1928; Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916). Raymond was then aged 37 and had a brilliant career at Oxford behind him – and, possibly, an even more brilliant career as a barrister in front of him. But he would be killed in action on exactly the same day and in exactly the same action as Stanhope and most of the rest of the Battalion’s officers. J.F. Worsley, who had landed in France on 28 October, joined Stanhope’s Battalion on 29 October 1915 when it was in billets at Norrent Fontes, about ten miles east-north-east of Béthune, and manning a part of the front line that had become very quiet since the fighting of the early autumn. Between 1 and 15 November, the Battalion made its way to the trenches north of Neuve Chapelle near Laventie, and the War Diary reads: “Situation very quiet but the trenches absolutely waterlogged.” Because of this, the men were spending 48 hours in and 48 hours out of the trenches, which were virtually impossible to keep in a state of good repair. James Richard Stanhope, the 7th Earl since 1905 and a Staff Officer since February 1915, visited Richard Philip in autumn 1915 at the Battalion’s billeting area at La Gorgue, just south-west of Estaires and north-north-east of Béthune, and noted in his diary that his younger brother had “thickened out, grown a strong chin and become much more of a man than the lad he had been previously”. Earl Stanhope would take advantage of his position to meet his brother on several occasions over the next year – both while Stanhope’s Battalion was in reserve on the Ypres front and while it was training further south during the build-up to the Battle of the Somme.

For the next few months after late October, the Battalion War Diary is very skimpy and, for example, makes no mention of Vernon’s return from training as a machine-gun officer. But we know that Stanhope’s Battalion was once again in billets at La Gorgue from 17 to 31 January 1916, that on 7 February 1916 it began to march northwards towards Wormhoudt, on the Franco-Belgian border, where it arrived on 22 February, and that by 25 February it was in the trenches east of Poperinghe, in the even quieter Ypres Salient. For the next six months the Battalion was in and out of the line near Ypres, where:

the trenches […] were in a terrible state after the bombardment [to which they had been subjected during the First and Second Battles of Ypres: see Somers-Smith]. The principal difficulty was that water stood in all the shell holes and the drains, of which there were very few, were blown in & the whole ground cut up. Another great disadvantage was that all the wooden revetments had been torn up & buried beneath the parapets and parados which made the work of clearing away the debris exceedingly slow.

Moreover, the Battalion War Diary noted that because of snipers and the fear of an artillery bombardment, “not a spadeful could or can be lifted in the daytime” so that “all work done at night has to be disguised as far as possible”. Stanhope experienced the dangers of German artillery at first hand when on 30 March 1916, “under very trying circumstances”, the Battalion was going into the line in order relieve a Battalion of the Scots Guards, and he was leading No. 2 Company, of which he was the Commanding Officer, through Potijze, an eastern suburb of Ypres. The Germans were sporadically shelling both the front line and the communication trenches, and after the leading three Companies had reached the front line safely, No. 2 Company, which was following them, was caught by shrapnel, causing seven casualties and narrowly missing Stanhope himself.

Captain Richard Philip Stanhope; Unit: 3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards

(©IWM HU126855) [Correction, TBC: This photo is of Richard Phillip’s elder brother, James Richard Stanhope, 7th Earl Stanhope]

The basis on which the formations were founded was that it was necessary to move all supporting troops simultaneously with those detailed for the actual assault in order to avoid the enemies’ [sic] barrage. Accordingly the Brigade was formed up in nine waves (a wave being a carrying party) at 50 yards distance and at zero time all waves advanced together under cover of (1) a standing barrage on the enemies’ [sic] front line, (2) a creeping barrage starting 100 yds in front of the assault and moving forward at 50 yds per minute. When the creeping barrage reached the standing barrage, both lifted to 200 yards beyond the German front line. The leading waves passed over the front line and formed up behind the barrage. The standing barrage was then put down on to the second line. The front trench was cleared by the new waves.

During this period, Stanhope and his brother were able to meet up and go for a long walk in the nearby hills. Afterwards, the Earl noted: “He seemed so happy both as regards his home life and his regimental duty except that he was fearful of making a mistake at the expense of the men under his command.” They met for the last time on 23 August 1916, at the Battalion’s camp near Marieux. During the same period, on 27 August 1916, J.F. Worsley’s younger brother, E.G. Worsley, who had landed in France on 12 August, joined his elder brother’s Battalion.

On 9 September the Battalion moved to Happy (Death) Valley, near Mametz Wood, in preparation for the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (15–22 September). So at 21.00 hours on 14 September 1916, the Battalion set off by Companies and marched via Trônes Wood and Guillemont to the assembly point behind the front line at the village of Ginchy, which the war diarist described as labouring “under every disadvantage except that it was not shelled by the enemy”. Ginchy is situated two miles south of Flers on a high plateau that runs northwards for 2,000 yards, and then eastwards in a long spur for nearly 4,000 yards.

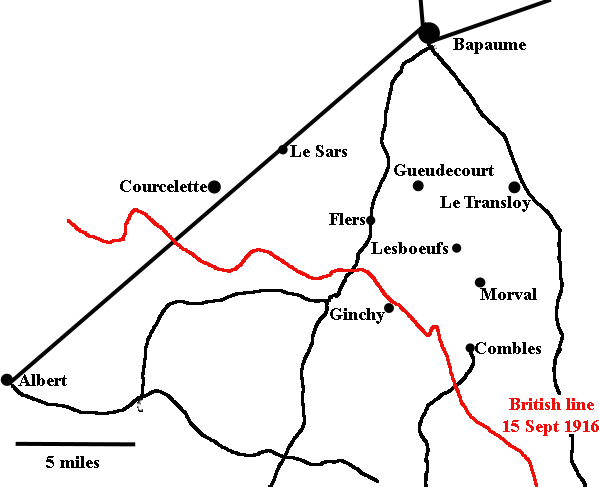

Area fought over by the Guards Division 15 September 1916

The village of Lesboeufs is a mile-and-a-half south of the village of Gueudecourt and stands on the northern end of that spur, with the village of Morval on its southern end. Morval is two miles from Lesboeufs, two miles north-east of Ginchy, and commands a good view in every direction. Another spur juts out from the plateau for a mile in a south-easterly direction and then falls sharply into the Combles Valley towards Falfemont Farm (see W.L. Vince). Bouleaux Wood, a mile to the west of Combles, is on the crest of the spur, with Leuze Wood in front of it and lower down. The British extreme right at Leuze Wood was 2,000 yards from Morval and in between there lay a broad, deep branch of the main valley that is overlooked by Morval and flanked at its head and by the high ground east of the valley that looks down into it. The Guards Division was positioned opposite this area, with the 6th Division on its right and the 56th (1/1st London) Division on its left, and was tasked with capturing Lesboeufs, an impossible undertaking if the other two Divisions proved unable to clear the two flanks and take Morval and Bouleaux Wood respectively.

On 15 September 1916, the 2nd Guards Brigade assembled in the trenches that looped north round the village of Ginchy (see map above) in preparation for the attack north-eastwards towards Lesboeufs, with the 1st Battalion, the Coldstreams, on the left and the 3rd Grenadiers on the right, and the 1st Scots Guards in the rear as a reserve. The attack began at 06.20 hours under a creeping barrage and by 07.15 hours the Brigade had captured its objectives: but about 250 yards out, the assaulting troops reached a hastily improvised enemy trench, and although the attacking troops killed everyone to be found there, the trench had been equipped with well-positioned machine-guns that had raked the 3rd Battalion’s left front Company, killing Lieutenant Asquith and the Company’s other officers. Stanhope’s Company, the Battalion’s right front Company, was even more fatally exposed to enfilading fire and lost all but two of its officers killed, wounded or missing – i.e. 17 out of 22. These included its Commanding Officer and Stanhope, who was killed in action during the charge on Lesboeufs, north-east of Ginchy, halfway between the first and second objectives, aged 31. Then, during the mayhem which followed, the depleted waves of advancing men became intermingled. Worse, the 6th Division on the Guards’ right failed to advance, causing the Guards’ right flank to be completely exposed. And of the 11 tanks assigned to cover the attack, only five arrived: of these, two took no part in the battle, three got lost and one of these ditched, so that the 2nd Guards Brigade had to split into two in order to cover its exposed flanks. Moreover, because the attacking formations were broken, only a few troops were available to assault Lesboeufs, two-and-a-half miles away to the north-east. Small-scale fighting continued throughout the night of the 15/16 September, German counter-attacks were driven back, and at 09.25 hours on 16 September 61st Brigade, part of 20th (Light) Division, captured the previous day’s third objective: a section of the Ginchy–Lesboeufs road. But 20 per cent of the officers, Company Sergeant-Majors and senior non-commissioned officers of Stanhope’s Battalion had been deliberately kept in reserve for such an eventuality, and when, on 20 September, the survivors of the Battalion fell back on Carnoy, the Battalion could be reconstituted in a matter of days. It was moved back to Trônes Wood by 26 September. Stanhope and Vernon fell less than two miles south of Flers, just to the north of Ginchy, where H.W. Garton, E.K. Parsons and Southwell were killed in action on the same day. Altogether, the attack on Flers cost the Guards Battalions that were involved 415 officers and ORs killed, wounded and missing.

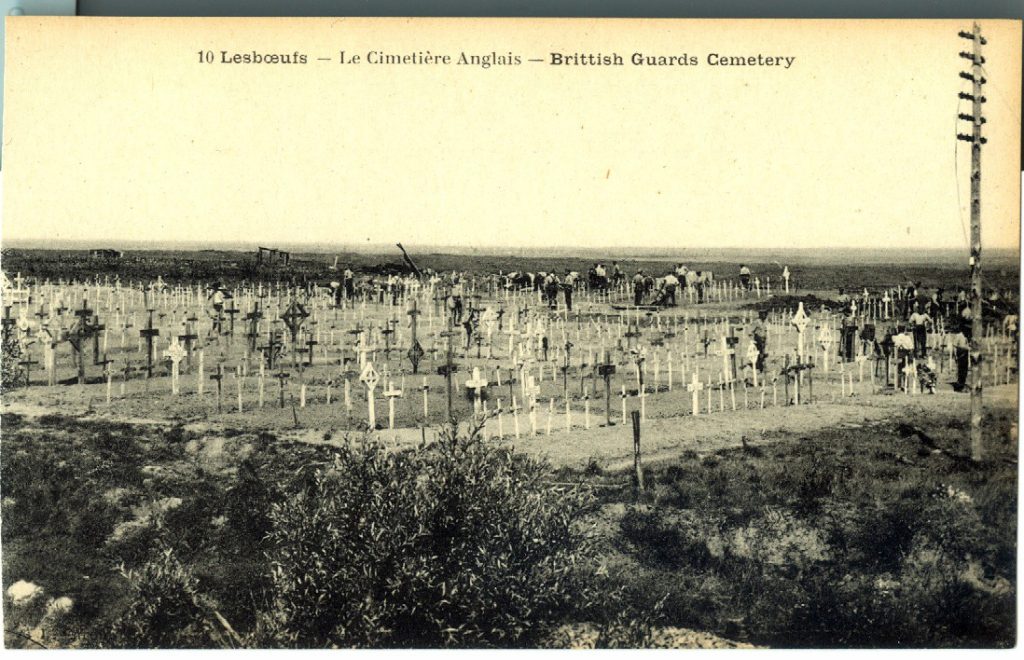

The Guards Cemy at Lesboeufs (c. 1919).

The Lincolnshire local newspapers reported that Stanhope was killed in action “while leading his men in a glorious charge” when he was shot, and then continued: “but with indomitable courage he dashed forward, only to receive another bullet in the chest, which killed him”. This is not quite accurate and it has been possible to reconstruct the circumstances of his death more accurately thanks to Earl Stanhope’s personal War Diary and a letter of 15 July 1919 from him to Mr Carter, one of Magdalen’s Fellows. Although very few of the Battalion’s officers survived the Battle of Flers, the Earl was able to speak to Stanhope’s orderly (Giles) who informed him that his brother was initially hit in the left thigh while out in the open, during the assault on the German positions, probably between the first and second line of German trenches, but that he (Giles) had been able to pull him into a shell-hole, where they remained for some time. But a German 4.2 cm shell burst immediately overhead, wounding Giles and shaking Stanhope – who then started to crawl out of the shell-hole in order to get to an Advanced Dressing Station. Giles expostulated, but in vain, and when Stanhope was almost out of the shell-hole he was hit in the chest by a bullet from a German sniper and died in Giles’s arms within a few minutes. Giles then covered him with a waterproof sheet and managed to get back to the Advanced Dressing Station to have his own wound attended to. A brother officer added that Stanhope “did much too much himself and was constantly taking too great risks and was too brave”.

On 24 March 1917 and again in April, Earl Stanhope took advantage of his standing as a General Staff Officer (Grade 1) to walk the area where his brother had died – but no trace of the body was ever found, presumably because it had been shattered and deeply buried by subsequent shell-fire. Stanhope has no known grave but is commemorated on Pier and Face 8D of the Thiepval Memorial. On the afternoon of Tuesday 26 September l916 a memorial service was held in St Mary’s Church, Horncastle, and according to the Lincolnshire Chronicle:

Every shop in the town was closed out of respect to the deceased Lord of the Manor and the church was crowded with reverent worshippers which [sic] included residents of Horncastle and the neighbouring villages. The scholars (boys and girls) of the Grammar School (of which [the] deceased was a governor) were present, wearing black bands on their arm[s], and were under the charge of the headmaster Mr. A. H. Worman. Lieut. Col. A. G. Weigall, M.P., was unable to attend owing to military duties, but was represented by Mr. A. H. Beeton, Conservative agent. In the assembly were also Mr. Hugh Walker, agent to the Revesby estate, the Rev[d] B. Brice Smith, Vicar of Hameringham, and Mr. F. E. Enderby, Chairman of the Urban Council. The service was of a most solemn and impressive character. Following the singing of the hymn ‘Oh God our Help in Ages Past’, portions of the Burial Service were read, also the 39th Psalm ‘I will take heed to my ways’. The lesson[,] which was taken from the 3rd Chapter of Solomon[,] was read by the Rev[d] G. A. Bullivant, the hymn ‘Now the labourer’s task is o’er’ then being sung with deep feeling. And after the prayer, a short but appropriate address was delivered by the Vicar (Canon A. E. Moore). The service ended with the singing of the hymn ‘On the Resurrection morning’ and the playing of the Dead March in “Saul” by Mr F. Hunt the organist. The Rev[d] J. Clare Hudson (Thornton) assisted in the service.

Towards the end of June 1917, the Stanhope family were distressed to hear that Stanhope’s widow had remarried without warning and that she was gradually disposing of her late husband’s furniture and pictures from Revesby. An extremely short obituary – a mere nine lines – appeared in The Times on 25 September 1916, possibly because of the much longer ones that were published in the Lincolnshire newspapers, nor does his name appear on the oak memorial tablet in St Mary’s Church, Horncastle, that was unveiled by the Bishop of Lincoln on 31 July 1921. But his name is recorded on two memorials – at Revesby and at Chevening – and they read thus: “Brave, eager and unselfish, he was generally beloved. / ‘E’en as he trod that day to God, so walked he from his birth, / In simpleness and gentleness and honour and clean mirth.’” He left £63,044 6s. 9d.

Bibliography

For the books and archives referred to here in short form, refer to the Slow Dusk Bibliography and Archival Sources.

Special Acknowledgements

The Editors would like to put on record that they did not know of Nigel McCrery’s excellent book Hear the Boat Sing (The History Press: Stroud, 2017) until January 2019. It provides detailed accounts of the lives of 42 Oxford and Cambridge Rowing Blues who died as a result of World War One, and as eight of these were Magdalenses or closely connected with Magdalen through a relative, it would seem that the Editors and Mr McCrery have been following parallel research paths without knowing of each others’ existence and so have made use of the same resources. But whereas Mr McCrery has focussed more on the finer points of top-class rowing, the Editors have focussed more on family and social history. As a result the two projects not only overlap in places, but also complement each other well.

Printed sources

[George Potter], ‘Right Hon. Edward Stanhope, M.P.’, The Monthly Record of Eminent Men, no. IV (November 1891), pp. 197–204.

[Anon.], ‘Obituary: Lord Stanhope’, The Times, no. 37,686 (20 April 1905), p. 8.

[Anon.], ‘The Countess of Clancarty’ [obituary], The Times, no. 38,128 (1 January 1907), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘The Boat Race’, The Times, no. 38,613 (6 April 1908), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘The Hon. Richard Stanhope and Lady Beryl Le-Poer-Trench’, The Times, no. 40,457 (26 February 1914), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘Marriage’, The Times, no. 40,523 (14 May 1914), p. 11.

[Anon.], ‘Hon. R.P. Stanhope Killed while Leading his Men’, The Lincolnshire Echo, no. 2,815 (23 September 1916), p. 4.

[Anon.]. ‘Lord Stanhope’s Heir’, The Times, no. 41,281 (25 September 1916), p. 16.

[Anon.], ‘The Late Capt. Hon. R.P. Stanhope: Sympathy from Horncastle Bench’, ibid., no. 2,816 (25 September 1916), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Death of Capt. the Hon. R.P. Stanhope’, The Lincolnshire Chronicle, no. 4,831 (30 September 1916), p. 7.

[Anon.], ‘Local War Notes: Captain, the Hon. Richard Philip Stanhope’, Malvern News, no. 2,466 (30 September 1916), p. 2.

[Anon.], ‘Oxford’s Sacrifice, The Hon. Richard Philip Stanhope (Magdalen College)’ [obituary] Oxford Magazine, Extra No. (10 November 1916), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘In Memoriam: Captain The Hon. Richard Stanhope’, The Eton College Chronicle, no. 1,590 (16 November 1916), p. 120.

Ponsonby, Grenadier Guards (1920), i, p. 341; ii, pp. 1, 5, 6, 87, 103, 107, 163; iii, pp. 208, 236.

[Anon.], ‘The Dowager Lady Stanhope’, The Times, no. 43,520 (10 December 1923), p. 9.

[Anon.], ‘High Court of Justice’, The Times, no. 44,256 (27 April 1926), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘High Court of Justice’, The Times, no. 44,943 (12 July 1928), p. 5.

[Anon.], ‘Lord Clancarty’ [obituary], The Times, no. 45,130 (18 February 1929), p. 17.

[Anon.], ‘Lord Stanhope: Gift of Chevening Manor to the Nation’, The Times, no. 57,021 (16 August 1967), p. 8.

Hugh G. Martineau, [Photo of Revesby Abbey], Lincolnshire Life, 8, no. 5 (July 1968), pp. 34–5.

Aubrey Newman, The Stanhopes of Chevening: A Family Biography (London: Macmillan [St Martin’s Press], 1969), pp. 200–1, 332–55.

Leinster-Mackay (1984), p. 52.

Hutchins (1993), pp. 26–9, 31, 37.

McCarthy (1998), pp. 100–2.

Brian Bond (ed.), The War Memoirs of Earl Stanhope: General Staff Officer in France 1914–1918: Lieutenant[-]Colonel Earl Stanhope, DSO, MC (Brighton: Tom Donovan Editions, 2006), pp. xii, 65, 68, 78, 83, 93–5, 122, 129.

Blandford-Baker (2008), p. 111.

McCrery (2017), pp. 120–4.

Archival sources:

Lincolnshire County Archives: FANE 6/11/3/16 (Banks) (Pedigrees and Heraldry)

–– GS/1/1 (1889–1910) and GS/1/2 (1910–1926) (Governors’ Meetings, Horncastle Grammar School).

–– LQS/A/2/85 (Lindsey Quarter Sessions Minute Book, 1909–14).

MCA: Ms. 876 (III), vol. 3.

MCA: 04/A1/1 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1888–1907]), pp. 398–402, 438–48, 454, 457–9, 461–4, 477, 484.

MCA: 04/A1/2 (MCBC, Crews and Blues: Secretary’s Notebook [1907–26]), unpag.

OUA: UR 2/1/52.

AIR27/594/5 (National Archives).

WO95/1219.

WO339/71943.